Tra il sedicesimo e il diciottesimo secolo, l'Europa fu al centro di un avanzamento senza precedenti nel progresso scientifico e tecnologico. La scoperta di nuove rotte di navigazione e l'idea di un mondo interconnesso esortò i missionari a viaggiare verso l'Asia per diffondere i Vangeli. In particolare durante i regni di Kangxi (1662-1722), Yongzheng (1723-1735) e Qianlong (1736-1795), si concentrarono alla corte Qing numerosi missionari eruditi provenienti da ogni parte del mondo.

Oltre a introdurre in Cina diverse novità tecnologiche, tra cui l'orologio meccanico, il telescopio e diversi altri strumenti scientifici, questi missionari lavorarono come artisti di corte, contribuendo a ravvicinare la cultura occidentale a quella orientale. Questa sezione, "Incontro tra Oriente e Occidente", porta i visitatori indietro nel passato. Entriamo insieme nel mondo di Giuseppe Castiglione per assistere alla nuova cultura creata dal primo tentativo di modernizzazione della Cina.

Storia del Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Taipei

- Collocazione

-

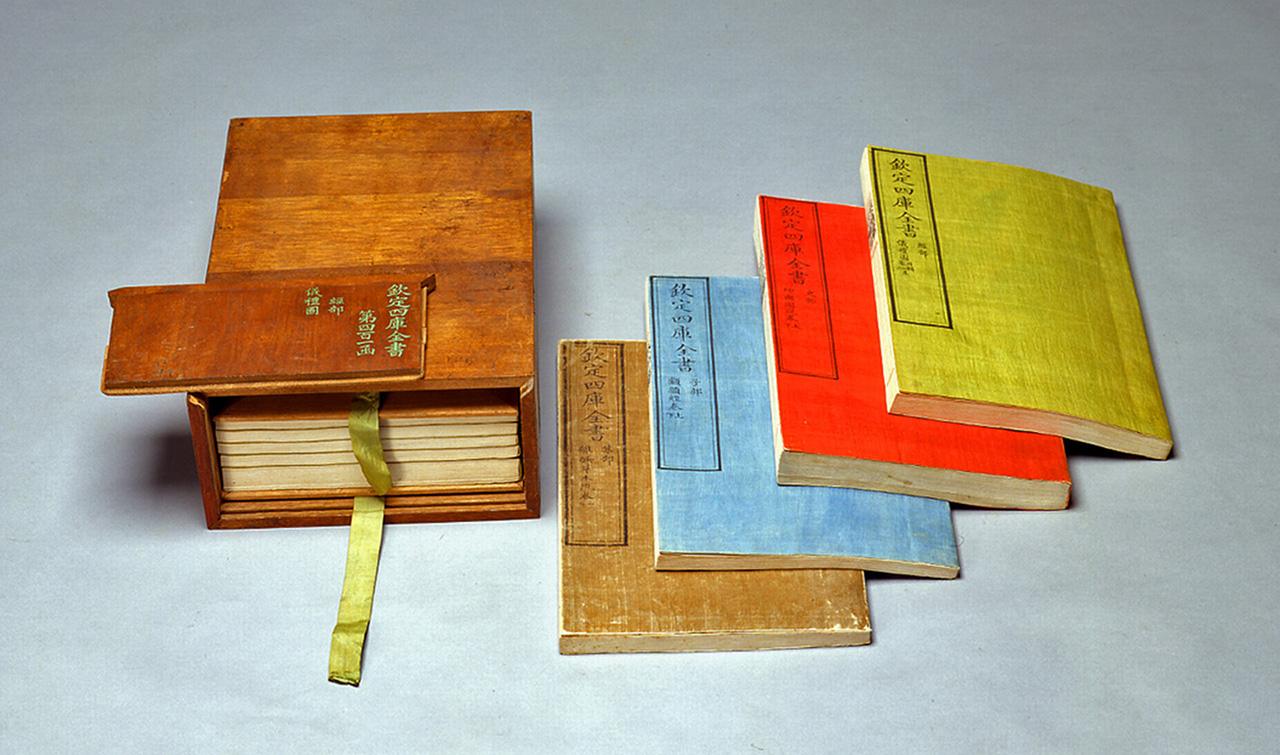

- Il 10 ottobre 1925 la Città Proibita della dinastia Qing a Pechino diventò il Museo Nazionale del Palazzo, ereditando le collezioni appartenute agli imperatori di epoca Song, Yuan, Ming e Qing, che furono rese visibili al pubblico.

- Nel 1933, per evitare che i reperti conservati nel Museo della Città Proibita fossero distrutti durante l'aggressione giapponese, i reperti furono spostati verso sud-ovest, e nel 1948 arrivarono a Taiwan. Dal 1965, il Museo è stato rilocato a Waishuangxi, Taipei.

- Preziosa collezione

-

- La collezione del Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Taipei è formata da quasi settecentomila reperti, tra cui opere calligrafiche della corte Qing, dipinti, oggetti di bronzo, porcellane, oggetti di giada, oggetti laccati, accessori preziosi, oggetti smaltati, tessuti, reperti religiosi, rari documenti antichi e di epoca Qing. Negli ultimi anni sono stati aggiunti altri artefatti provenienti da altre zone dell'Asia, rendendo la collezione di reperti storici e artistici imperiali famosa a livello internazionale.

Il Time Tunnel di "Immagini di missioni di tribute"

Il "Tunnel tel tempo delle ‘Immagini di tributo

" è ispirato all'opera del pittore di corte della dinastia Qing, Xie Sui (era del regno Qianlong, data di nascita e morte incerte) "Immagini di tributo". L'artista seguendo il cerimoniale di corte, rappresenta missioni di tributo provenienti da diverse parti del mondo: Russia, Giappone, Vietnam, Polonia, Inghilterra, Olanda, Portogallo, Corea, Taiwan, etc. . Attraverso il tunnel del tempo, il pubblico può ammirare sui due lati gli ambasciatori stranieri e ascoltare lingue di diverse parti del mondo, per provare l esperienza di tornare indietro al tempo di Giuseppe Castiglione.

Il "Tunnel tel tempo delle ‘Immagini di tributo

" è ispirato all'opera del pittore di corte della dinastia Qing, Xie Sui (era del regno Qianlong, data di nascita e morte incerte) "Immagini di tributo". L'artista seguendo il cerimoniale di corte, rappresenta missioni di tributo provenienti da diverse parti del mondo: Russia, Giappone, Vietnam, Polonia, Inghilterra, Olanda, Portogallo, Corea, Taiwan, etc. . Attraverso il tunnel del tempo, il pubblico può ammirare sui due lati gli ambasciatori stranieri e ascoltare lingue di diverse parti del mondo, per provare l esperienza di tornare indietro al tempo di Giuseppe Castiglione.

Artist

The National Palace Museum

Original work of Art

Illustrations of Tribute Missions by Xie Sui

Il pittore al servizio di tre imperatori cinesi: la vita di Giuseppe Castiglione

- Biografia

-

- Nato a Milano, Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) fu un fratello gesuita. Servì come pittore nella corte imperiale cinese dopo il suo arrivo dall'Europa a partire dal 1715 fino alla sua morte nel 1766. Attraverso la sua opera, si incaricò di lodare la bellezza del creato nella speranza di accrescere nel popolo la nozione dell'esistenza di un Creatore.

- Prima di arrivare in Cina, Castiglione era già un giovane pittore affermato e di talento. Arrivato in Cina, sviluppò un nuovo stile pittorico mescolando le tecniche europee a quelle apprese in Cina.

- Il Regno di Kangxi(1715-1722)

-

- Nel 1714, Giuseppe Castiglione lasciò Lisbona, in Portogallo, per raggiungere Pechino nel novembre dell'anno successivo. Fu un altro missionario, Matteo Ripa (1682-1745), a introdurlo all'imperatore Kangxi, segnando così l'inizio del servizio a corte di Castiglione che durò 51 anni.

- Nel 1721, il talento di Castiglione fu apprezzato e riconosciuto dall'imperatore.

- Il Regno di Yongzheng(1723-1735)

-

- Quando l'imperatore Yongzheng (1678-1735) ascese al trono, fu particolarmente compiaciuto dal talento pittorico e dall'obbedienza di Castiglione.

- Questo fu d'enorme aiuto alla sua missione, già di estrema difficoltà. Mentre Castiglione sviluppava il suo stile di incontro tra Oriente e Occidente, l'imperatore Yongzheng gli forniva consigli e lo guidava per assicurarsi che rispettasse le sue richieste. I suoi suggerimenti, in modo inaspettato, aiutarono Castiglione a creare uno stile pittorico estremamente personale.

- Il Regno di Qianlong(1735-1766)

-

- L'imperatore Qianlong era un amante dell'arte e cominciò ad apprezzare la pittura di Castiglione sin da quando era ancora principe. Quando ascese al trono, Castiglione divenne il suo pittore di corte preferito. Castiglione riuscì a stabilire un ottimo rapporto con l'imperatore Qianlong e, così facendo, riuscì anche a mantenere il suo lavoro da missionario.

- Nel 1747, Castiglione fu chiamato a progettare i palazzi di stile europeo del Vecchio Palazzo d'Estate. Creò tra l'altro una fontana in stile europeo con sculture di teste d'animale rappresentanti i segni dello Zodiaco. I palazzi, in stile barocco con tetto in vetro smaltato, sottolineavano l'armonizzazione tra le tecniche in uso nel 18esimo secolo sia in Europa che in Cina. Sfortunatamente, il palazzo fu bruciato dalle forze dell'alleanza Anglo-Francese nel 1860.

- Il 16 Luglio del 1766, Castiglione venne a mancare alla venerabile età di circa ottanta anni. Aveva servito la corte Qing per 51 anni.

- L'imperatore Qianlong gli conferì il titolo di Vice Ministro e contribuì con 300 liang d'argento al suo funerale. Castiglione fu sepolto nel cimitero dei missionari di Pechino. Giuseppe Castiglione spese tutta la sua vita da pittore nella corte Qing, lasciando ai posteri diversi capolavori.

-

Per ciò che riguarda la sua carriera da missionario, possiamo probabilmente concludere con una poesia cinese che con buona probabilità è attribuita proprio a Castiglione:

Potei gioire della grazie di tre imperatori dell'età d'oro

Essendo orgoglioso di servire l'impero Qing.

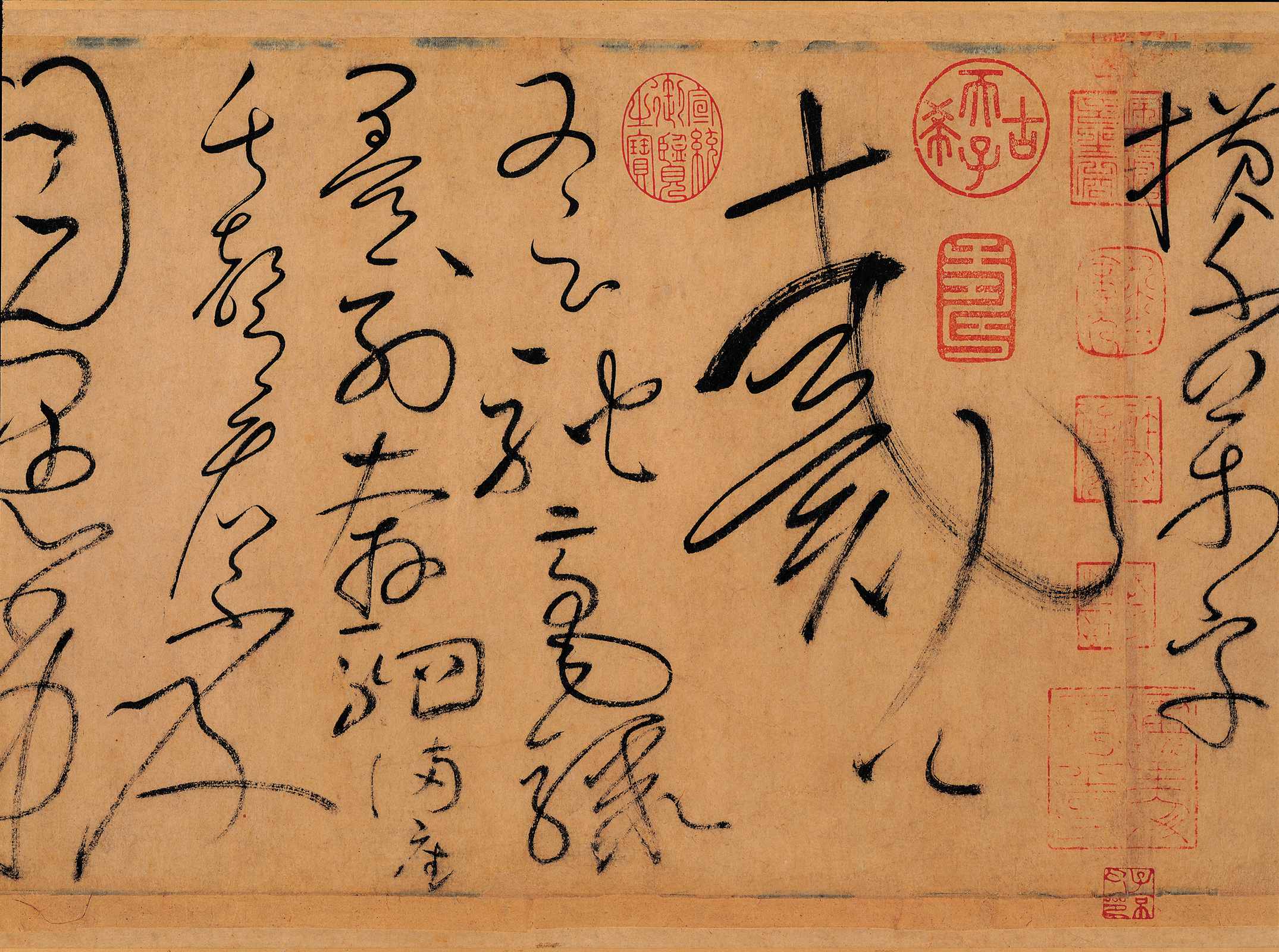

Ho riunito le tecniche europee e il disegno dai fini contorni di tradizione cinese.

Spero che il mio vivido stile possa convincere il pubblico ad apprezzare il creato.