Deciphering the Story in a Painting

Does the key to understanding what a painting "says" lie in the figures' expressions? Or the forms they take, their actions, their props, or the setting they inhabit? This section features several works in which the story is not easily identified. Why are they difficult to decipher? Is it because the artists relied on forms that are overly conventional? Or perhaps key visual cues are easily overlooked by the viewer? Do the depicted texts fall outside the scope of common knowledge at the time? Even when the main themes remain uncertain, there is a subtle pleasure in piecing together the possible narratives from the clues left on the picture surface.

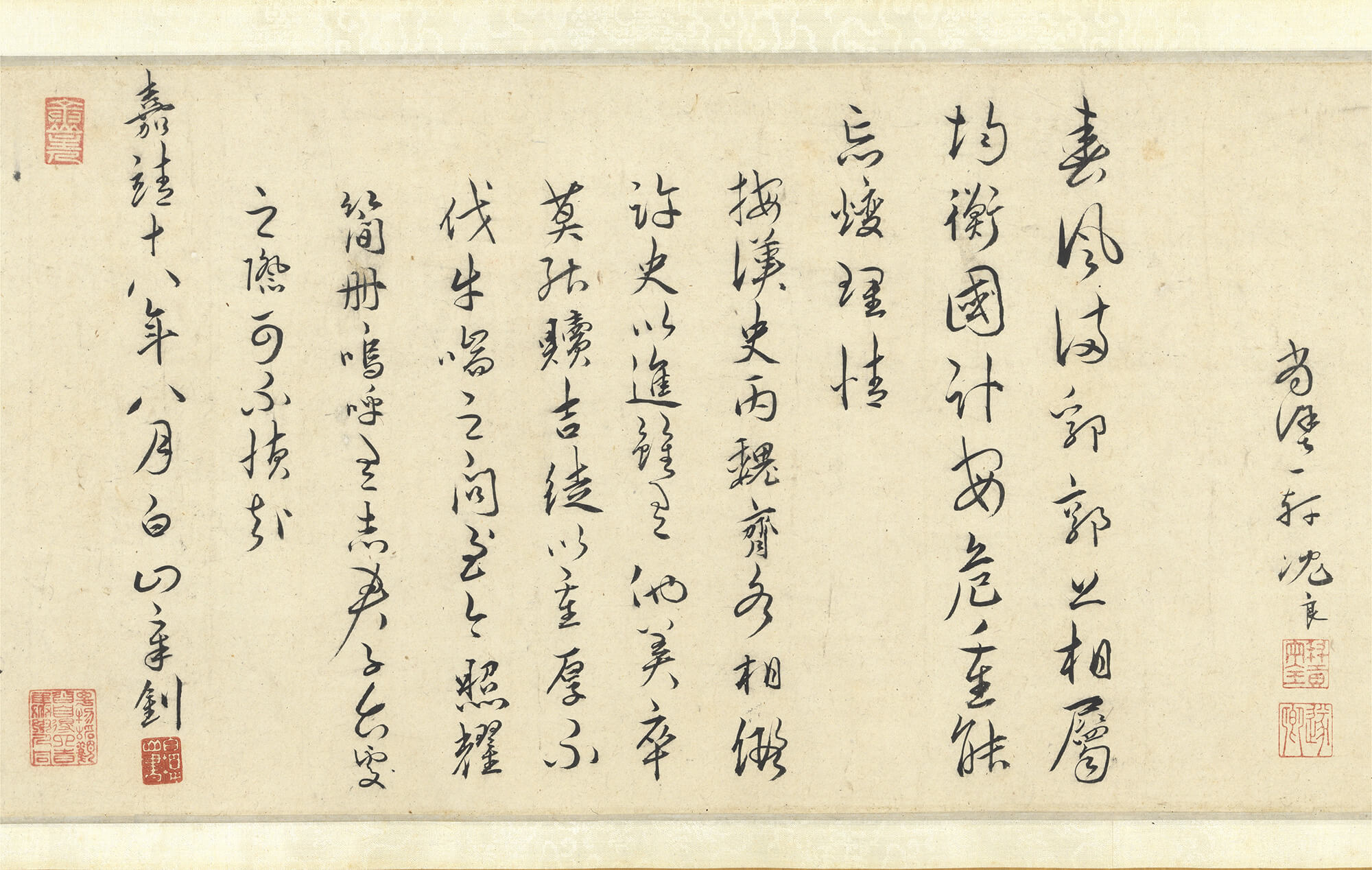

- Bian Zhuangzi Killing Tigers

- Anonymous, Song dynasty

- Silk

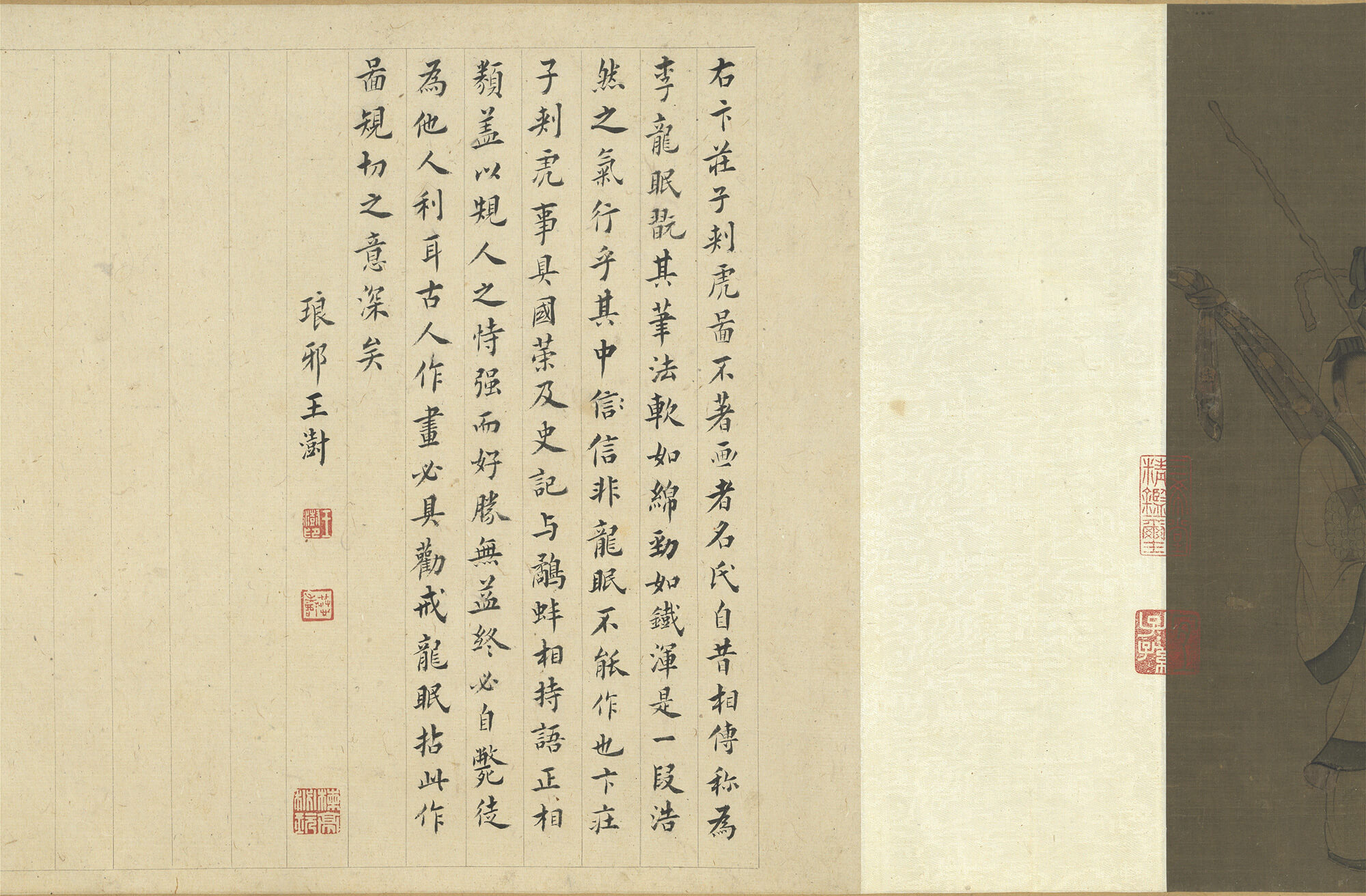

Bian Zhuangzi, a senior official of the State of Lu, was famous for his courage. On one occasion, he encountered two tigers fighting over an injured ox. Drawing his sword, Bian prepared to attack the tigers. A bystander advised him to wait until the tigers had exhausted each other, in order to nurture his strength and bide his time. Bian Zhuangzi followed this advice, and he needed only to defeat a single weakened tiger, easily capturing both. This story, found in Strategies of the Warring States and Records of the Grand Historian, is the source of an idiom similar to "killing two birds with one stone."

The painting is unsigned and traditionally attributed to Li Gonglin, though it is likely a misattribution. The work is finely rendered, with vigorous lines that vividly capture the protagonist's boldness and determination. The scene of the tigers entangled in their fight is portrayed in a sophisticated way, their manners full of vitality.

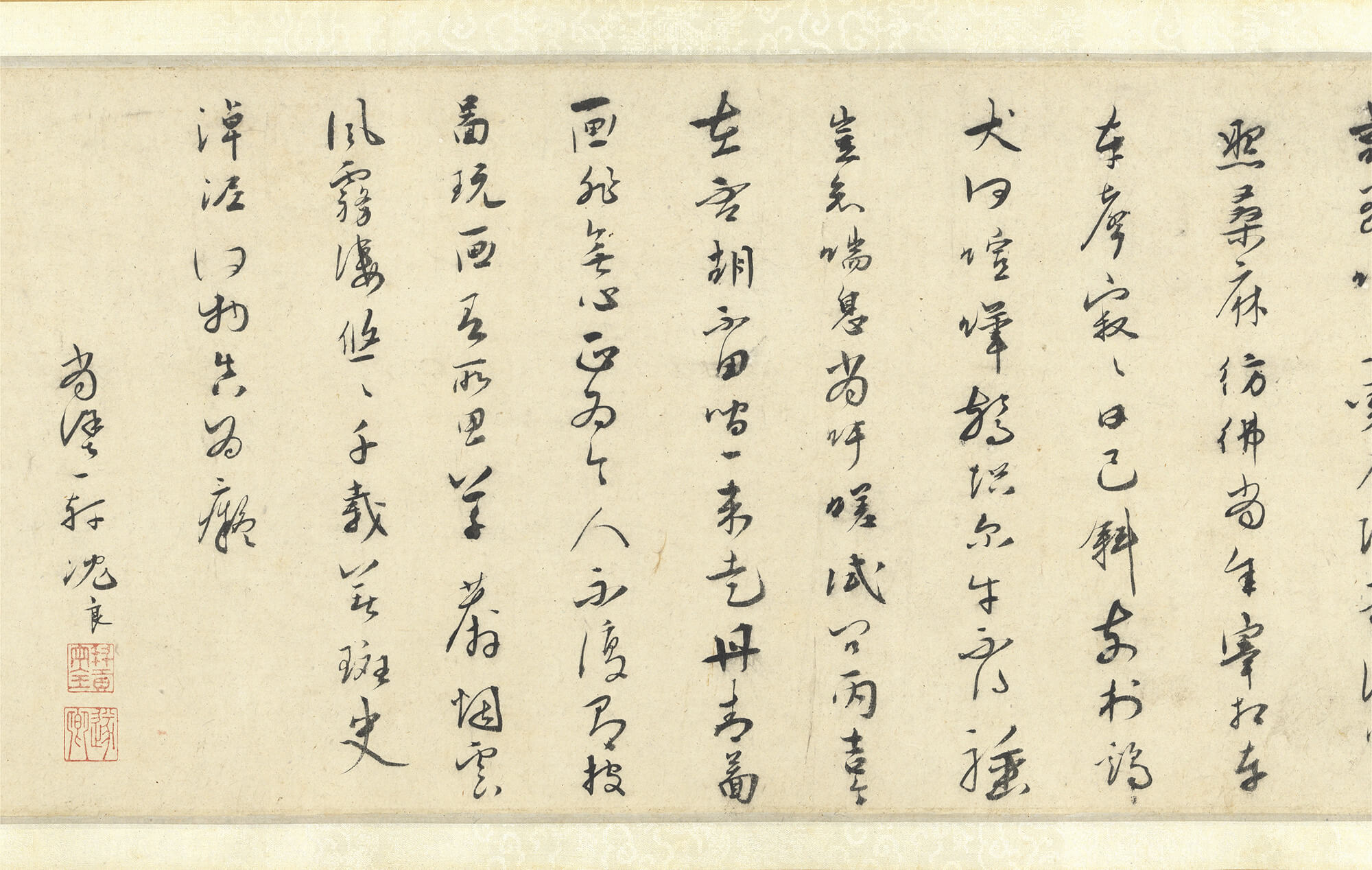

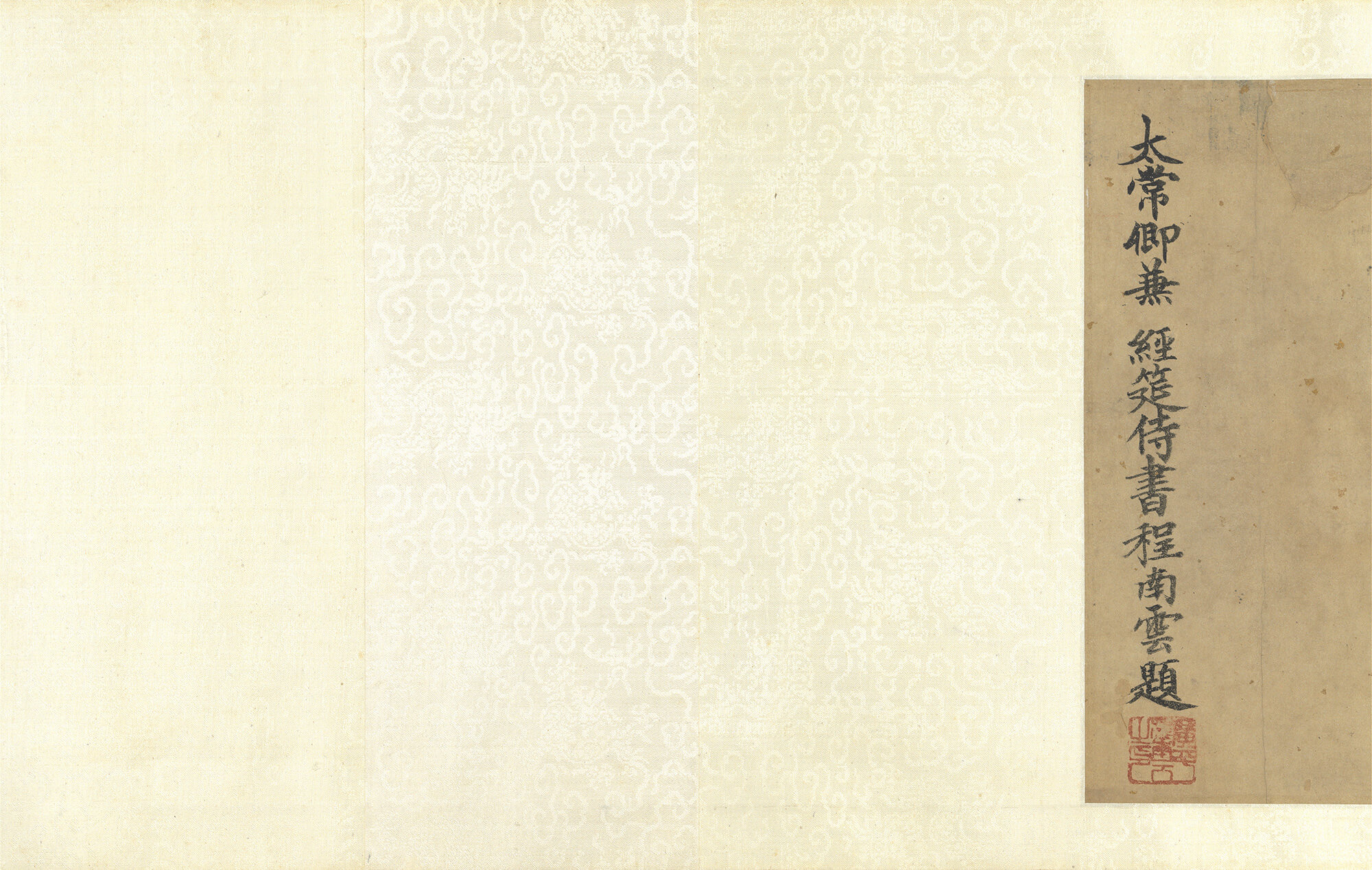

- Inquiring after the Water Buffalo

- Anonymous, attributed to Song Dynasty

- Silk

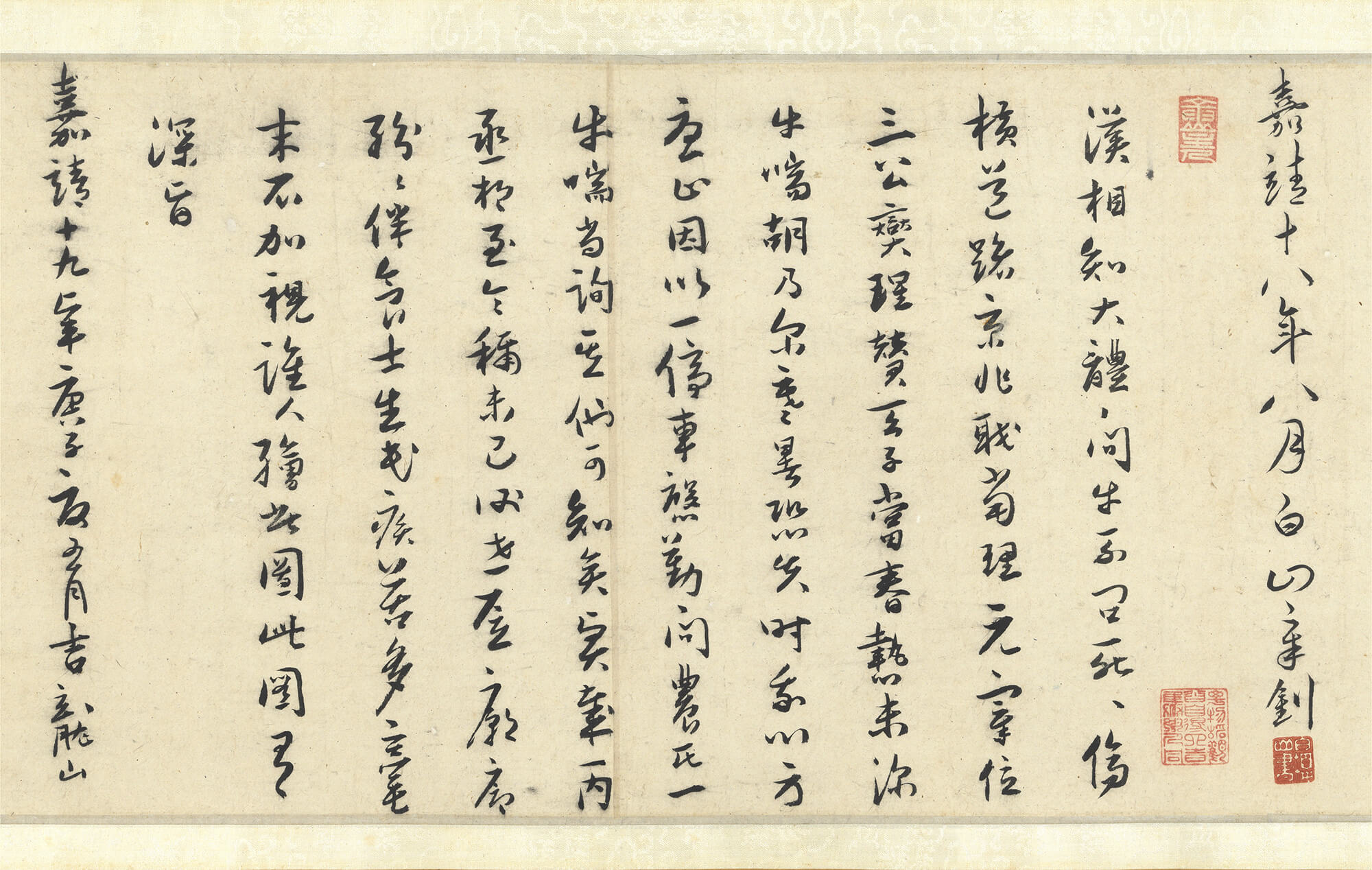

The story depicted here is taken from the Book of Han: Grand Councilor Bing Ji of the Han dynasty was travelling on an inspection tour when he encountered a crowd fighting to the point of death and injury. Yet, he did not stop to intervene. He instead ordered his men to investigate why a cow by the roadside was panting in distress. By doing so, he was able to gauge the seasonal activities and the welfare of the people, becoming a symbol in later times of a diligent and compassionate official.

The painting's application of ink is wet and dense with mist, and the setting is simple, drawing attention to the key moment of examining the ox. Though traditionally attributed to a Song dynasty artist, the lively portrayal of the figures' expressions and the fairly simple brushwork suggest it might be the work of a Yuan dynasty painter. This is supported by a colophon by Wang Feng (active 14th century) at the end of the scroll.

Story Introduction: Questioning an Ox's Shortness of Breath

During the Han dynasty, Prime Minister Bing Ji once passed a street brawl without inquiring into the incident. Further on, he saw an ox panting heavily and specially instructed his men to find out why. The attending officials mocked him for caring about the ox and not the people, to which Bing explained, "Handling brawls and arresting suspects are the responsibilities of the county magistrate and his superiors. At the end of the year, I will evaluate their performance and decide on their rewards or punishment accordingly. By contrast, I am concerned about the ox panting so soon in the spring due to potential climatic disorder, which could harm our people. Caring for the changes of seasons and balancing yin and yang are the duties of the prime minister, which was why I stepped forward to inquire." Hearing such an explanation, Bing's men were convinced of his grasp of the greater responsibilities of his office.

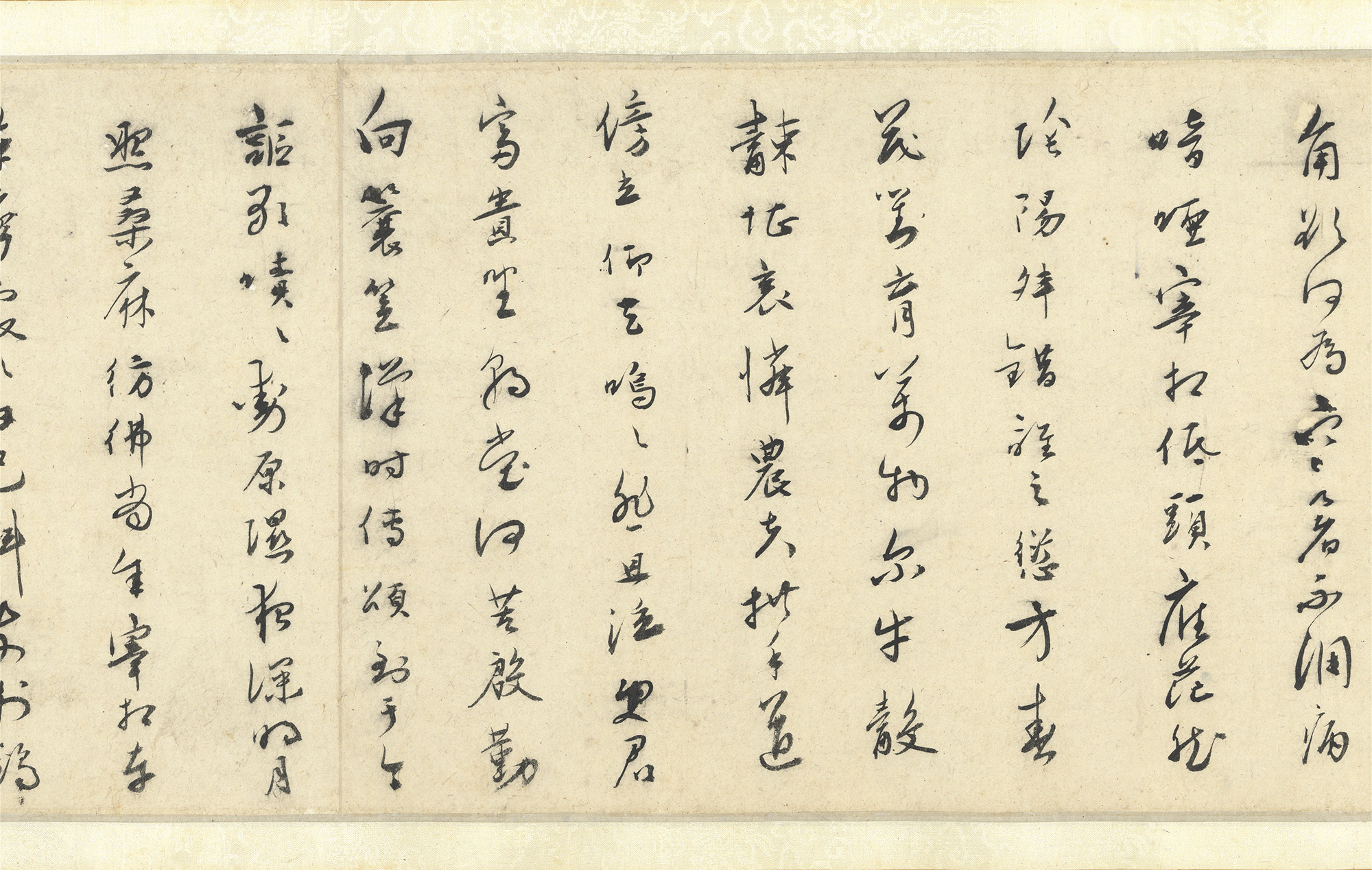

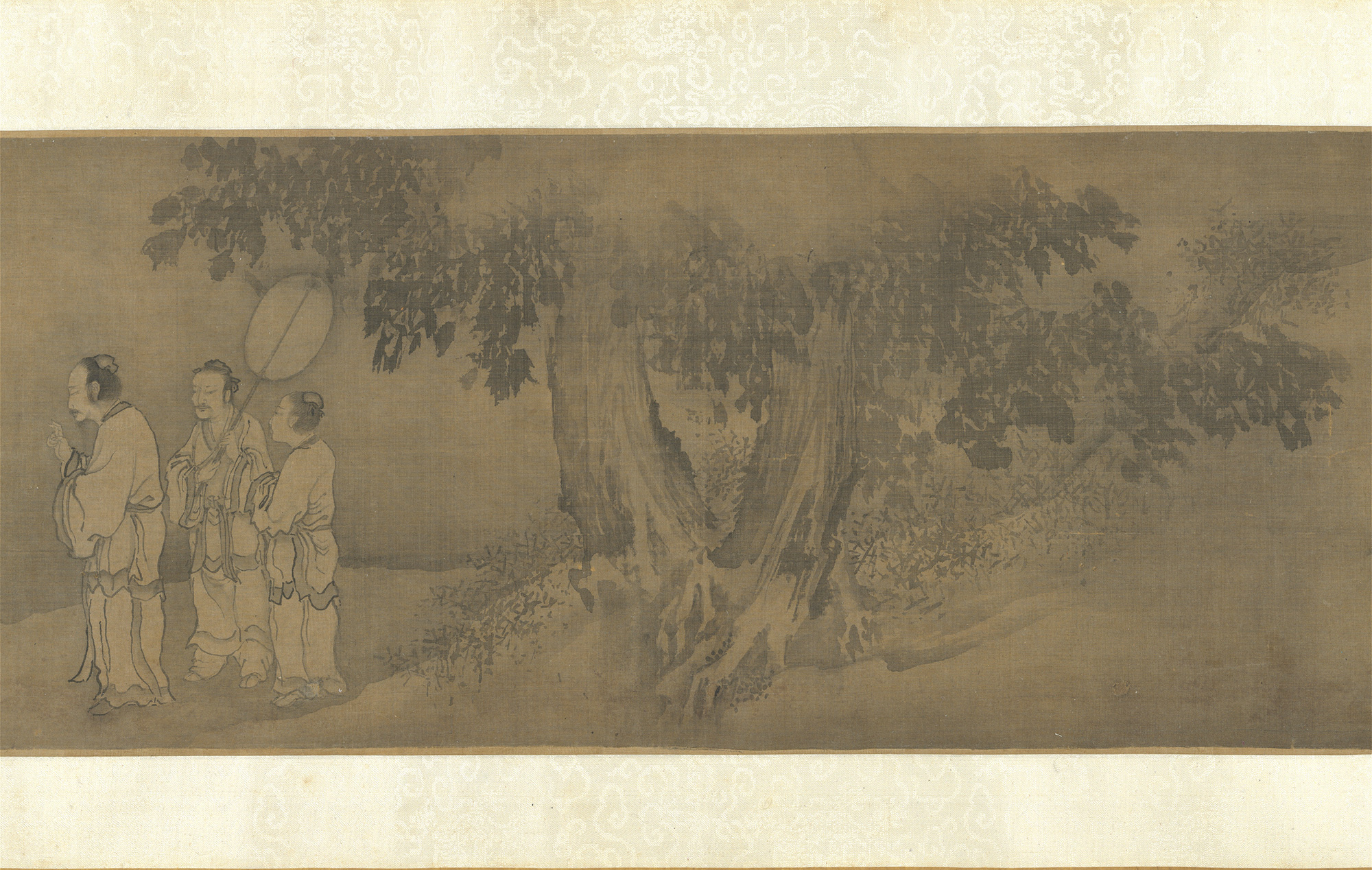

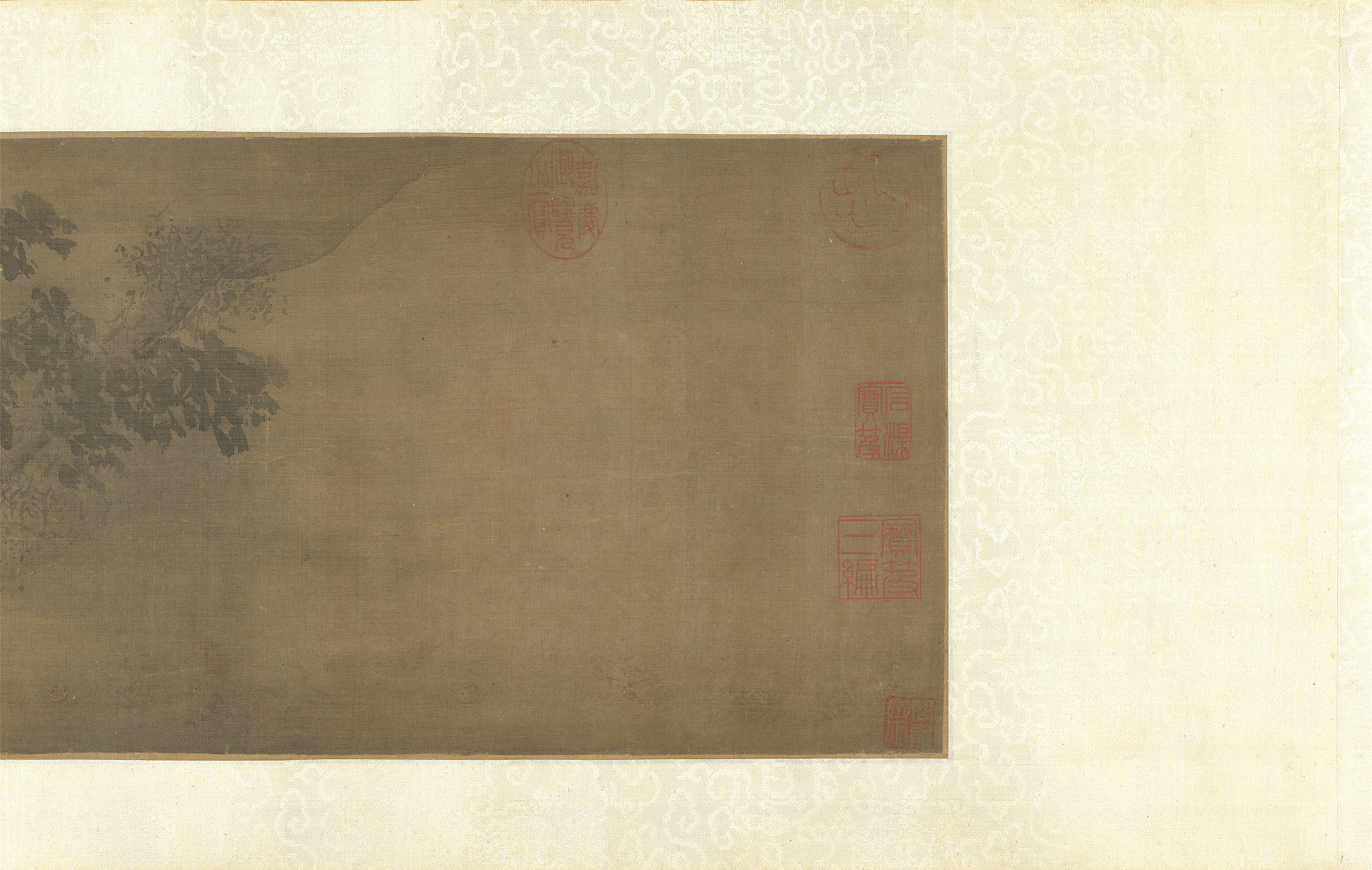

- Three Men Laughing by Tiger Creek

- Anonymous, Song dynasty

- Silk

The story of Three Men Laughing at Tiger Creek gives an account of Lu Xiujing (406-477) and Tao Yuanming (365-427) paying a visit to the monk Huiyuan (334-416). They were conversing so merrily that Huiyuan unknowingly broke his vow never to escort guests beyond Tiger Creek. This story was once widely known, though later scholars consider it to be fictional. It nevertheless symbolizes the ideal of harmonious coexistence between the three doctrines of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism.

A winding mountain stream flows through the background, while the composition is centered on the three men looking skyward and laughing heartily. Autumn is in the air: the large trees to the side have already turned red, and fallen leaves cover the ground. The brushwork used for the figures, rocks, and trees is skilled and polished, fully capturing the elegance of Southern Song style.

Story Introduction: Three Laughs at Tiger Brook

Master Huiyuan had lived on Mount Lu for over thirty years, never leaving its confines nor engaging with the secular world. Whenever he saw guests off across the Tiger Brook, tigers would always roar loudly, as if to remind Huiyuan not to cross the creek. On one occasion, he was seeing off the poet Tao Yuanming and the Taoist Lu Xiujing. Engrossed in their discussion of philosophical matters and finding great camaraderie in each other's company, they crossed the Tiger Brook without realizing it. Upon discovering this, all three burst into laughter.

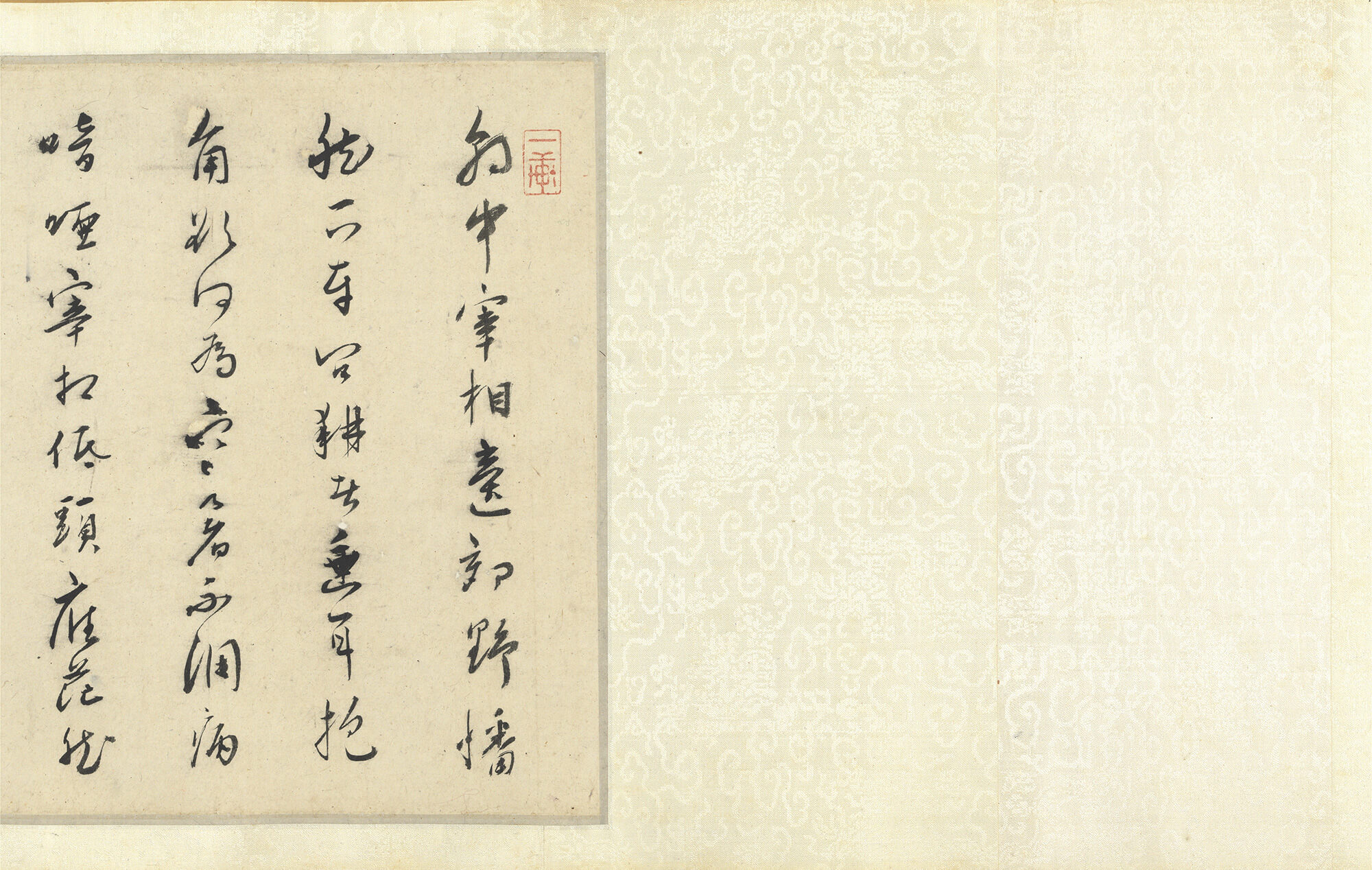

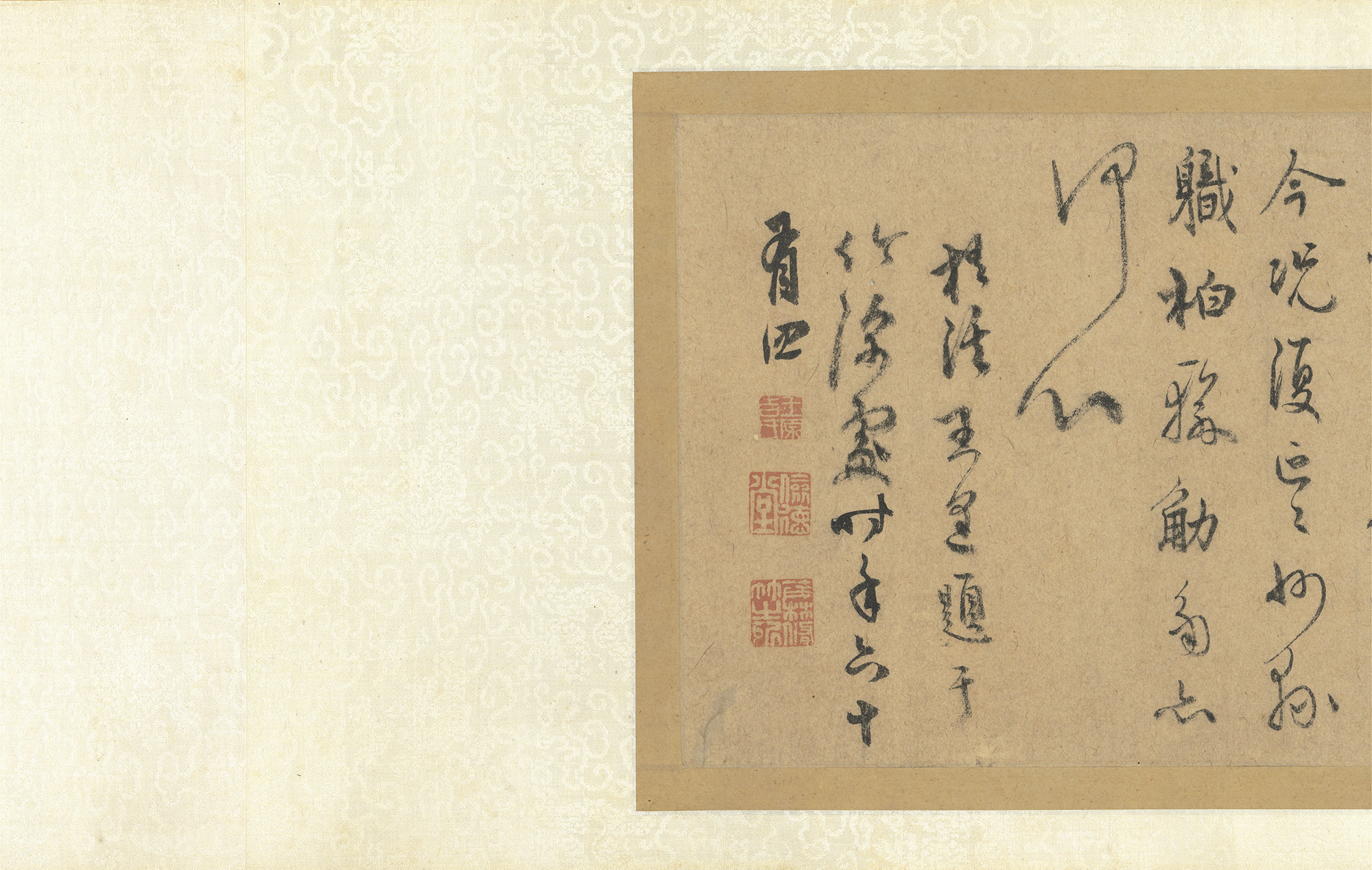

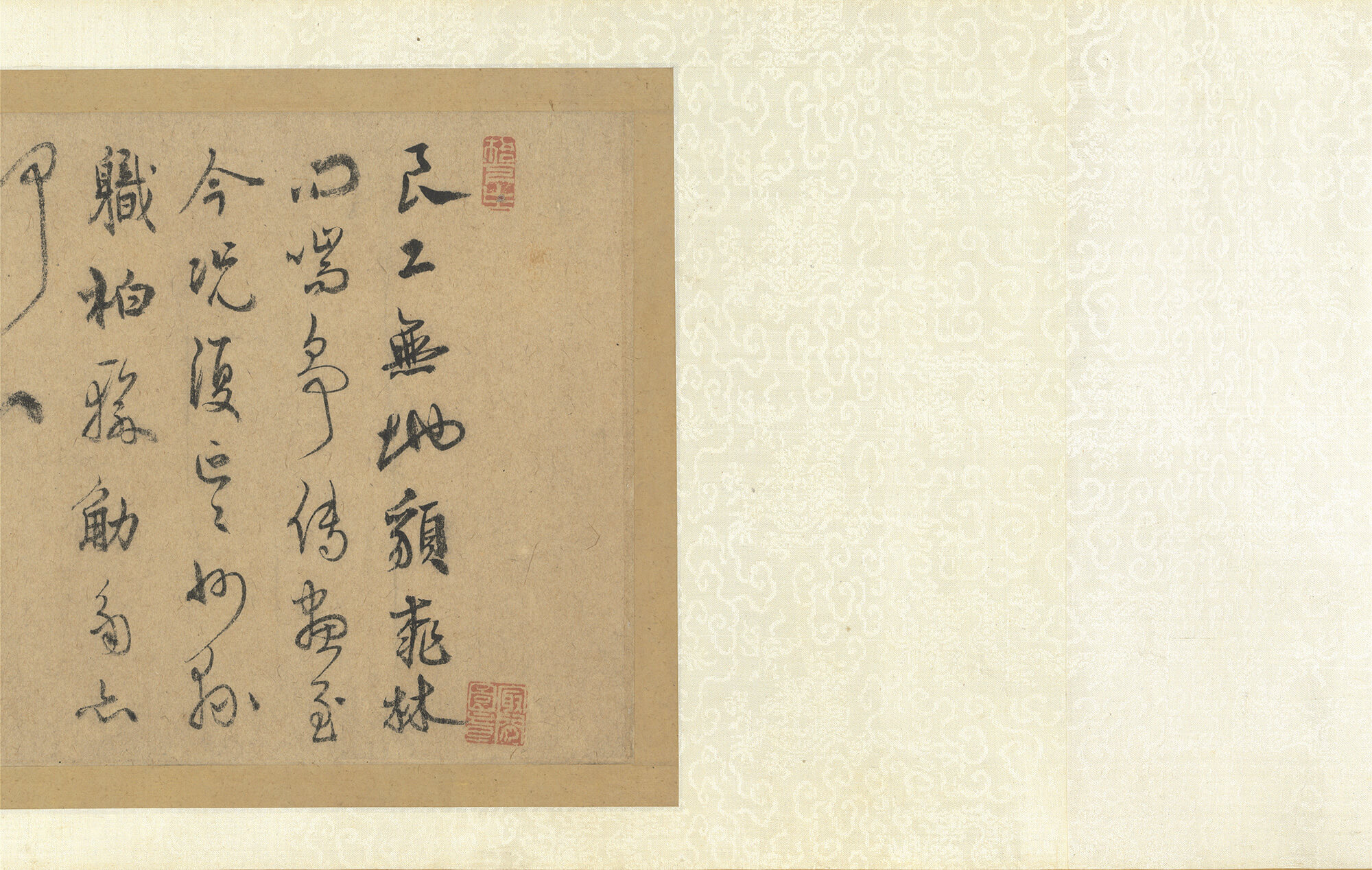

- Bridge on the Hao River

- Jin Tingbiao, Qing Dynasty

- Paper

This painting illustrates the famous "Debate at the Hao River Bridge" between Zhuangzi (c. 369-286 BCE) and Hui Shi (c. 370-310 BCE). As they pass by a bridge, the two engaged in a debate about whether the fish in the river were happy, how one could know if they were, and how each could know of the other's understanding of the fish's happiness.

In the painting, the two figures stand at the edge of the water. Their clothing and beards flow with movement, and they are speaking mid-sentence. One person tilts his chin slightly upward, gazing down, as if not convinced during the recreation of the debate. In the foreground, a towering, writhing cypress tree surges toward the sky, as if heightening the dramatic intensity of the scene. Jin Tingbiao (?-1767), a court painter during the Qing dynasty, was a favorite of Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) and known for his skill in depicting figures, flora, and landscapes.