Enlightening through Education, Upholding Social Relations: The Confucianist View of Painting's Primary Role

The 9th century art historian Zhang Yanyuan emphasized that the most important function of painting was to "enlighten through education and uphold social relations." The exhibition objects in this section reflect how these ideas were historically put into practice. Narrative paintings such as The Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety and Yuan An Lying Down in a Snowstorm were used to instill views on ethics and proper social relationships in the general public. Meanwhile, works such as The Mirror of Emperorship Illustrated Handbook and Wei Bin Fishing were intended to inspire rulers to learn from others and follow their example. The continued depiction of stories of loyalty, filial piety, integrity, and righteousness by artists across different time periods reflects such Confucian cultural ideals filtered through time and passed down through generations.

In premodern China, paintings were often didactic in intent, particularly within the court, where they were used to instruct imperial rulers. Works depicting ancient sages and wise rulers recounted their merits and mistakes, serving as reflections for emperors. Later, narrative paintings of historical figures were created to admonish emperors, encouraging them to be receptive to criticism. Eventually, such scenes of remonstration also became governance tools, promoting the ruler's magnanimity and ability to accept honest counsel from his ministers. Alternatively, these historical depictions were employed to convey messages to the emperor's subjects.

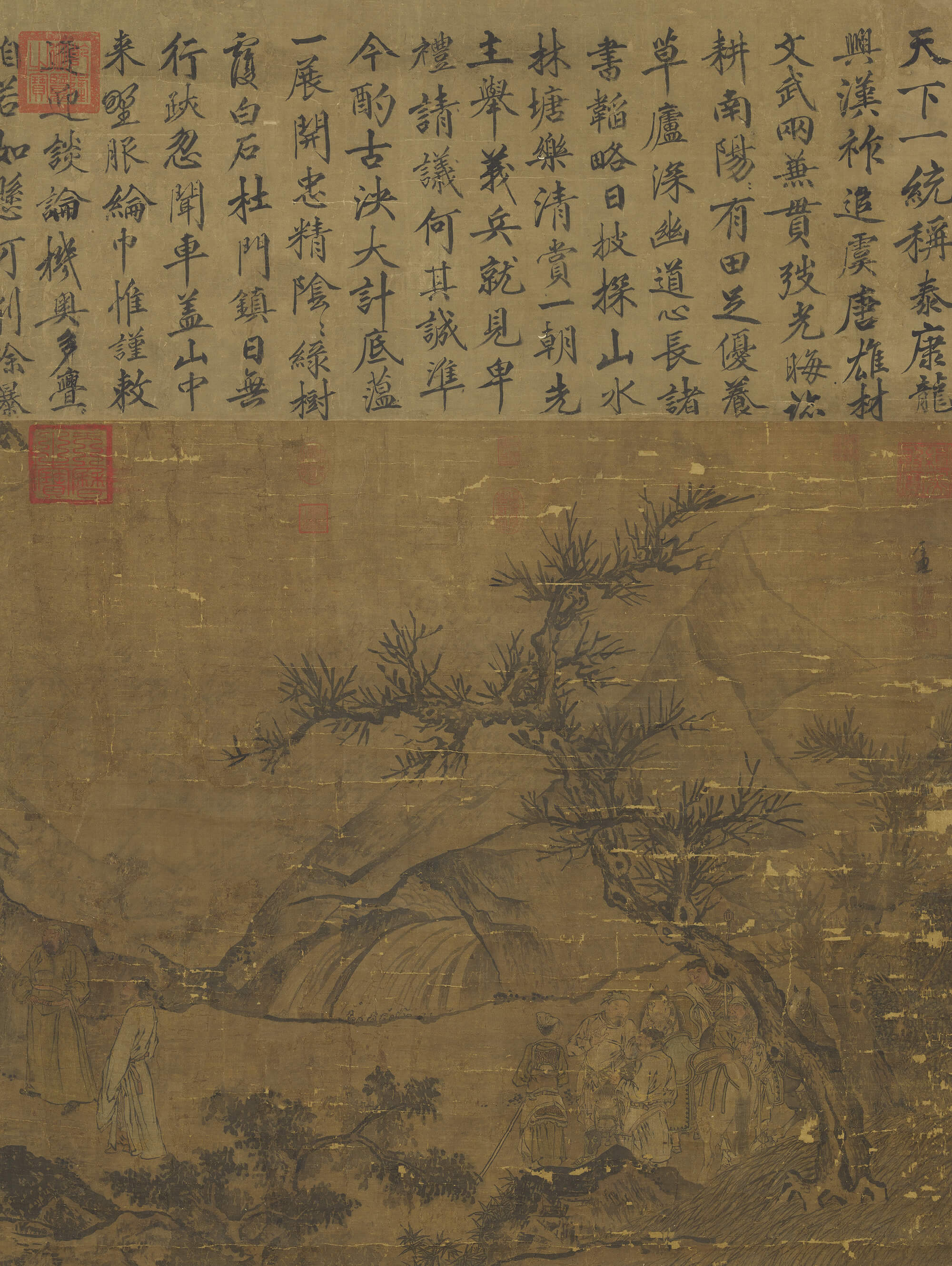

- Zhu Yun Breaking the Balustrade

- Anonymous, Song dynasty

- Silk

This painting illustrates an instance of admonishment from the reign of Emperor Cheng of Han (33-7 BCE). The magistrate of Huaili District Zhu Yun publicly accused Zhang Yu—both Counselor-in-chief and imperial tutor—of being a sycophant, infuriating the emperor. When ordered to be arrested and executed, Zhu Yun did all that he could to cling to the palace railing, breaking the balustrade in the process. Emperor Cheng ultimately pardoned Zhu Yun due to the persuasive remonstration of Xin Qingji, and the broken balustrade was left as to serve as a warning.

The artist sets the scene in a courtyard constructed with towering pine trees, rocks from Lake Tai, and ornately adorned railings, diverging from historical accuracy to increase the work's aesthetic appeal. Though unsigned, its figures are done in fluid lines and the details are delicately and thoroughly portrayed, suggesting this work is by a Southern Song court painter.

- Yuan An Freezes in the Snow

- Attributed to Yan Hui, Yuan dynasty

- Silk

The Eastern Han dynasty figure Yuan An(?-92) was once caught in a heavy snowstorm in Luoyang. Rather than disturbing others, he chose to lay motionless in his snow-covered home. He was later discovered by the local magistrate during an inspection and was nominated for office for his filial piety and integrity. The painting depicts the governor arriving by carriage, while his attendant peeks through the gate on tiptoe, seeming to imply an allegory of a ruler calling on men of worth to serve their country.

The scene captures the desolation of the snow-covered landscape, with rapid brushwork depicting the interlacing dead trees and bare branches. Swift, parallel lines articulate the vegetation and the wicker gate, while ink wash creates the hazy, veiled atmosphere of the fields of snow. The figures and their drapery are dynamic and drawn with energetic lines, close in style to the mid-to-late Ming dynasty Zhe School, suggesting this is a Ming period work.

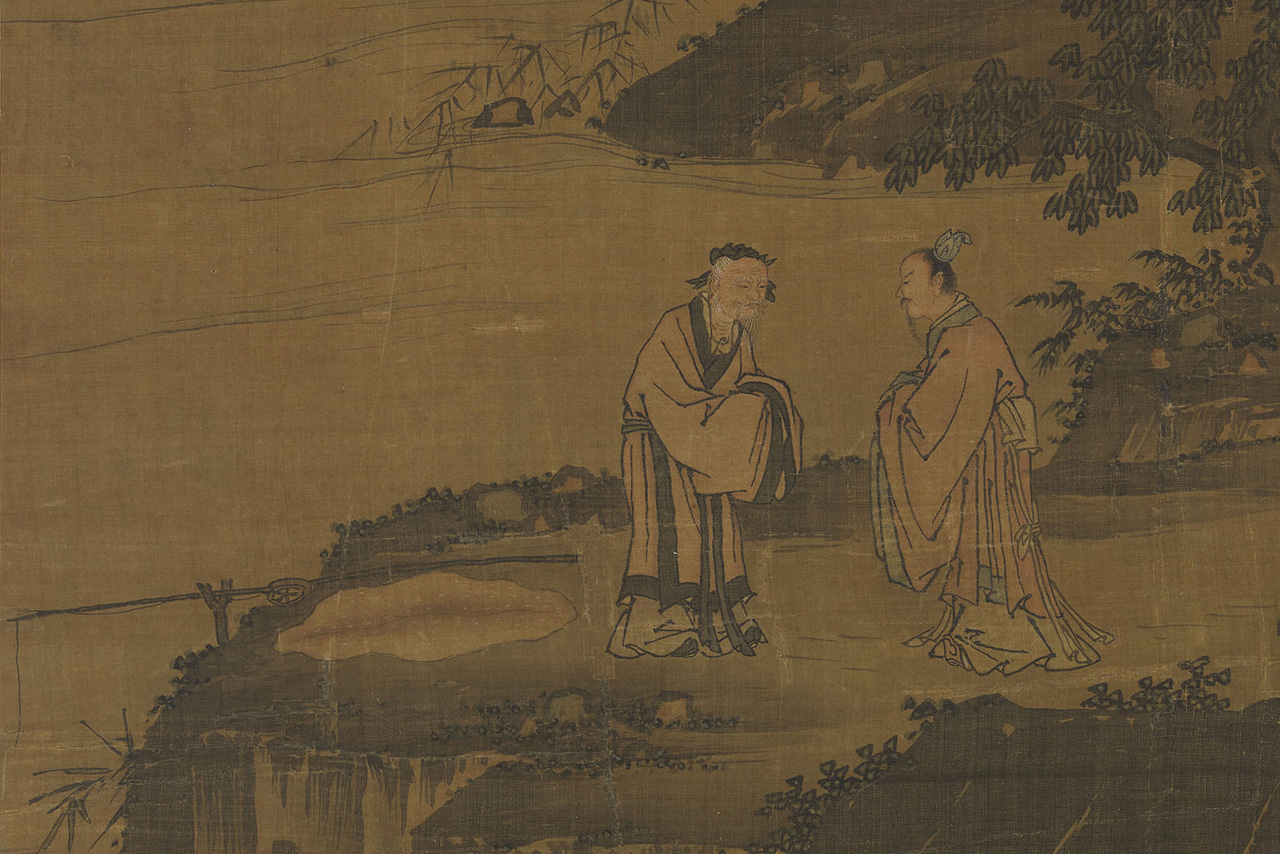

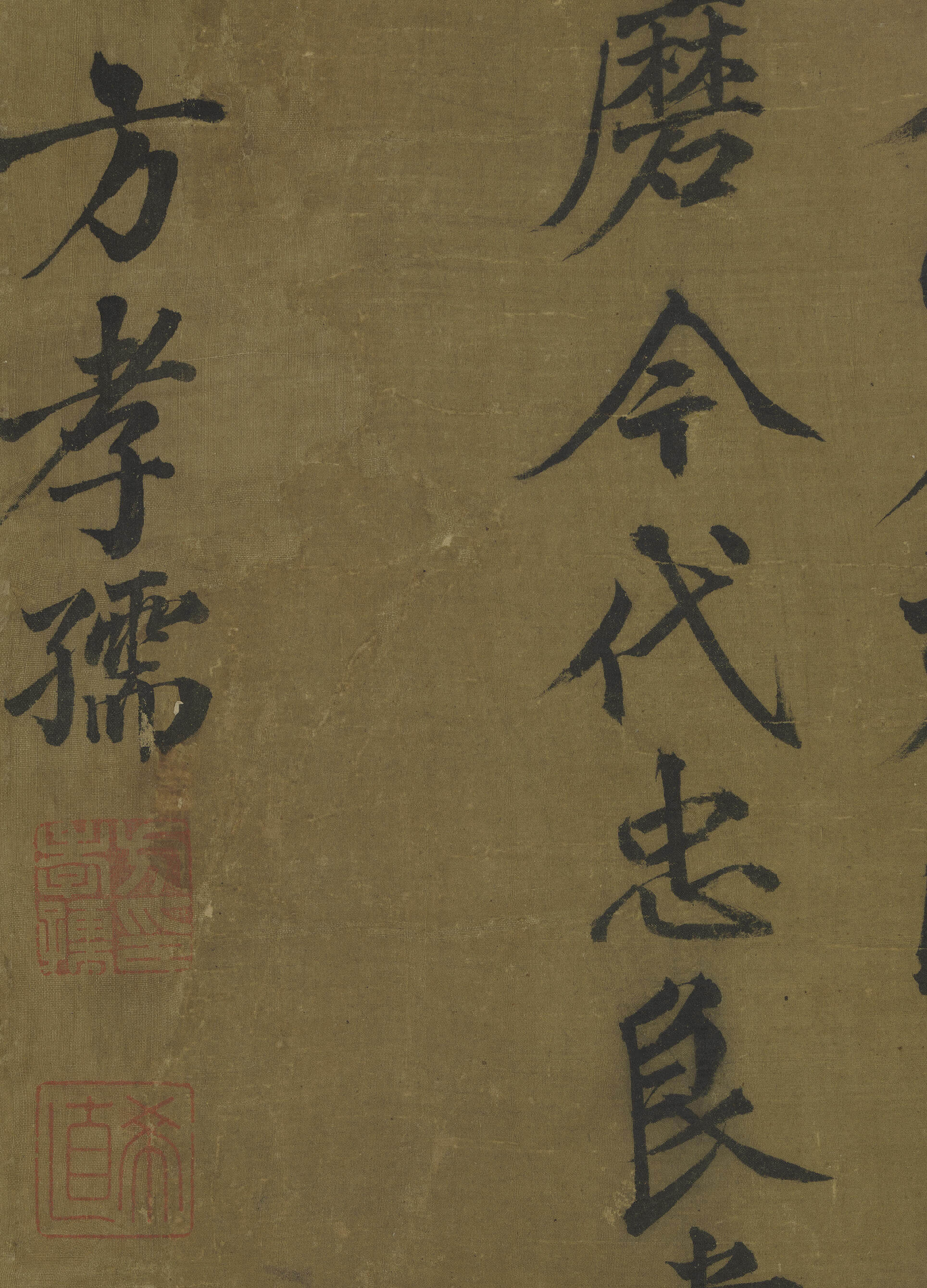

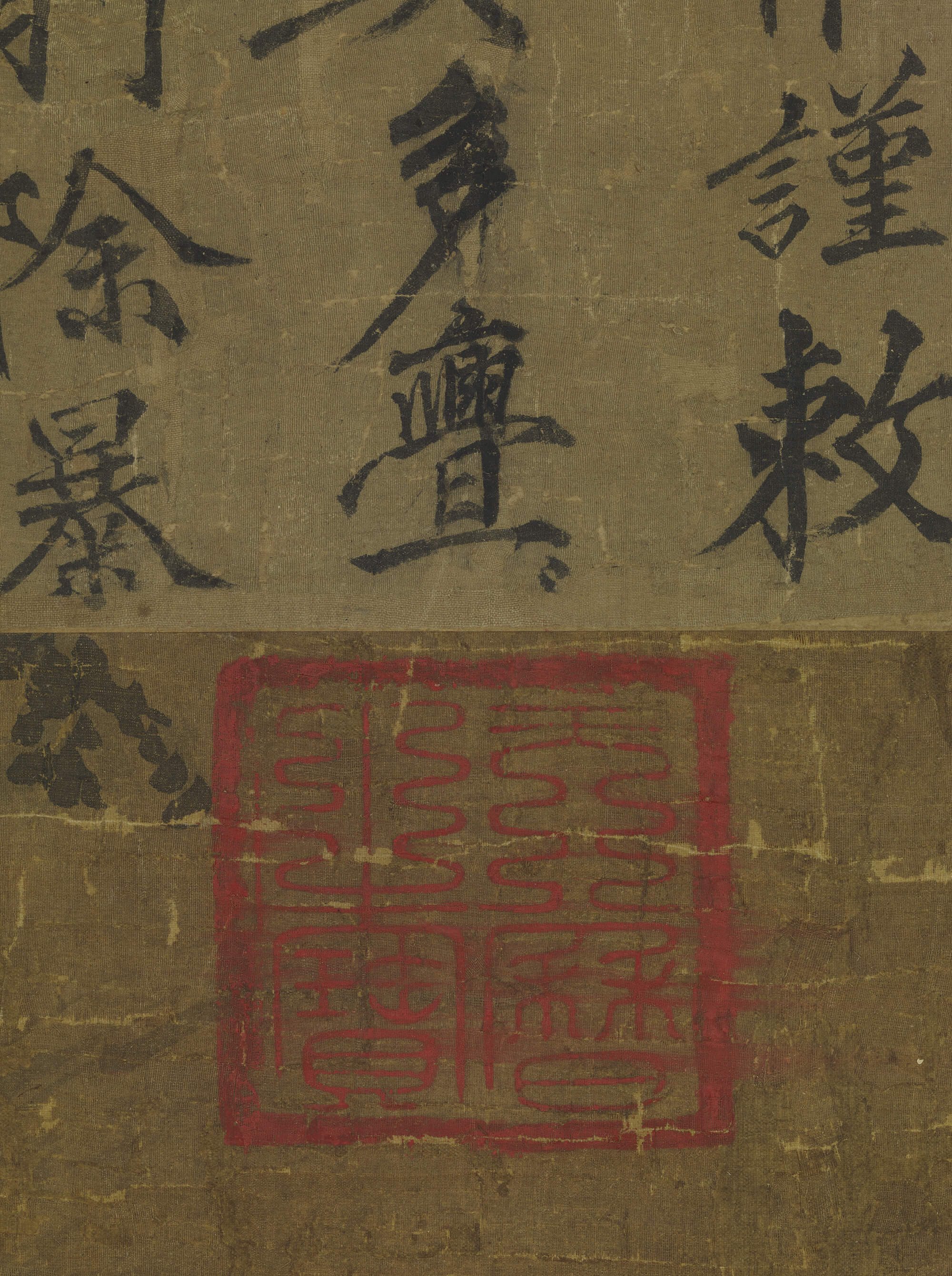

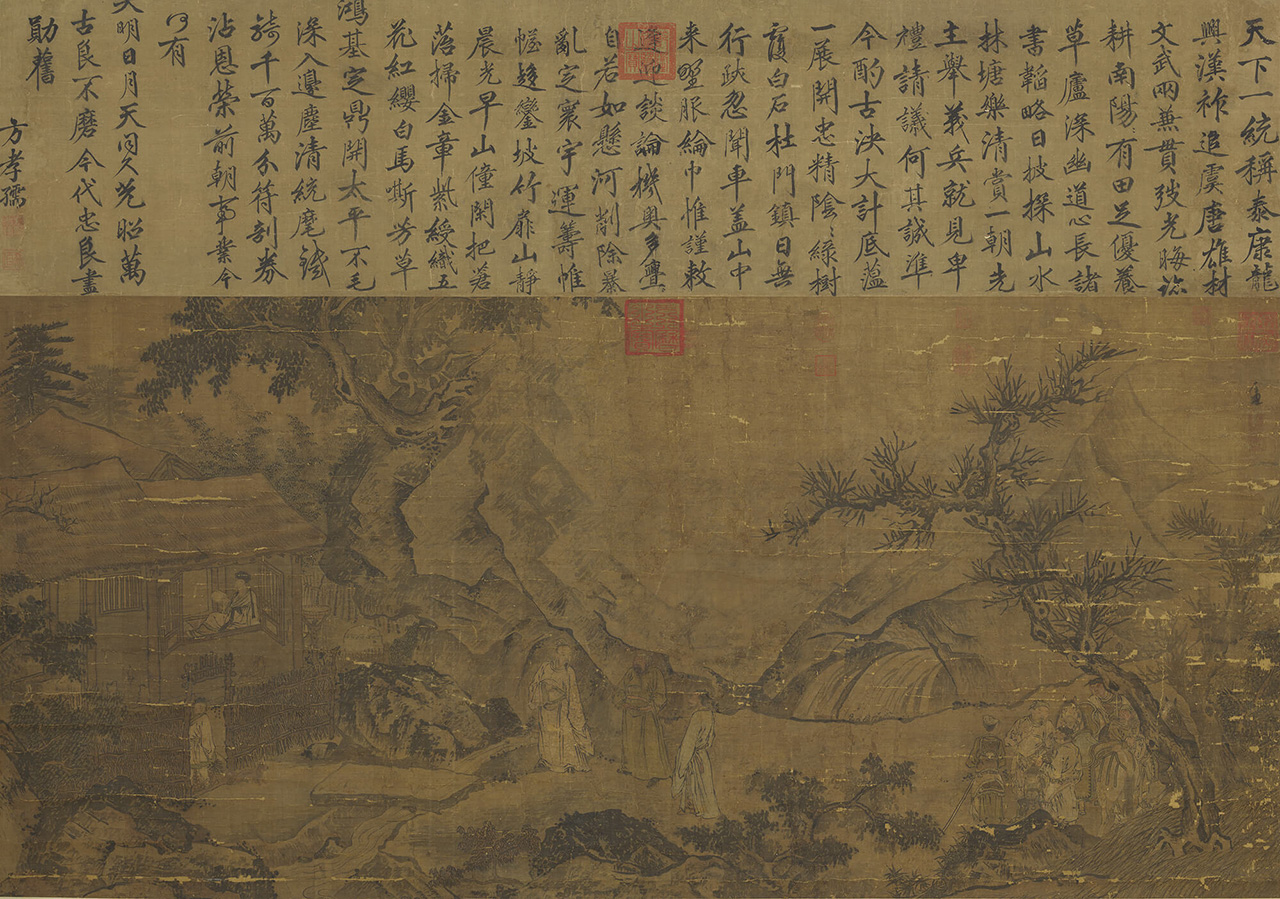

- Fishing on the Banks of the Wei River

- Dai Jin, Ming dynasty

- Silk

This painting depicts the story of King Wen of Zhou (1112-1050 BCE) paying a visit to the recluse Taigong Wang while the latter was fishing by a riverbank. Time and again, King Wen was tested by Taigong Wang and emerged as a person of virtue and talent, receiving an official post. Two figures are shown bowing to each other by a willow-lined embankment, with the fishing pole on the shore pointing to the white-haired man as Taigong Wang. Five attendants wait behind the trees, keeping their distance from the protagonists. The saturated axe-cut strokes on the stones in the foreground serve to draw the viewer's attention to the central figures.

Dai Jin (1388-1462), courtesy name Wenjin, was a court painter during the Ming dynasty. This work mainly follows the painting styles of the Southern Song artists Li Tang and Ma Yuan, with the most of scenery placed on the composition's right side. The figures and their robes are punctuated with angular lines, while the rocks are depicted using axe-cut texture strokes.

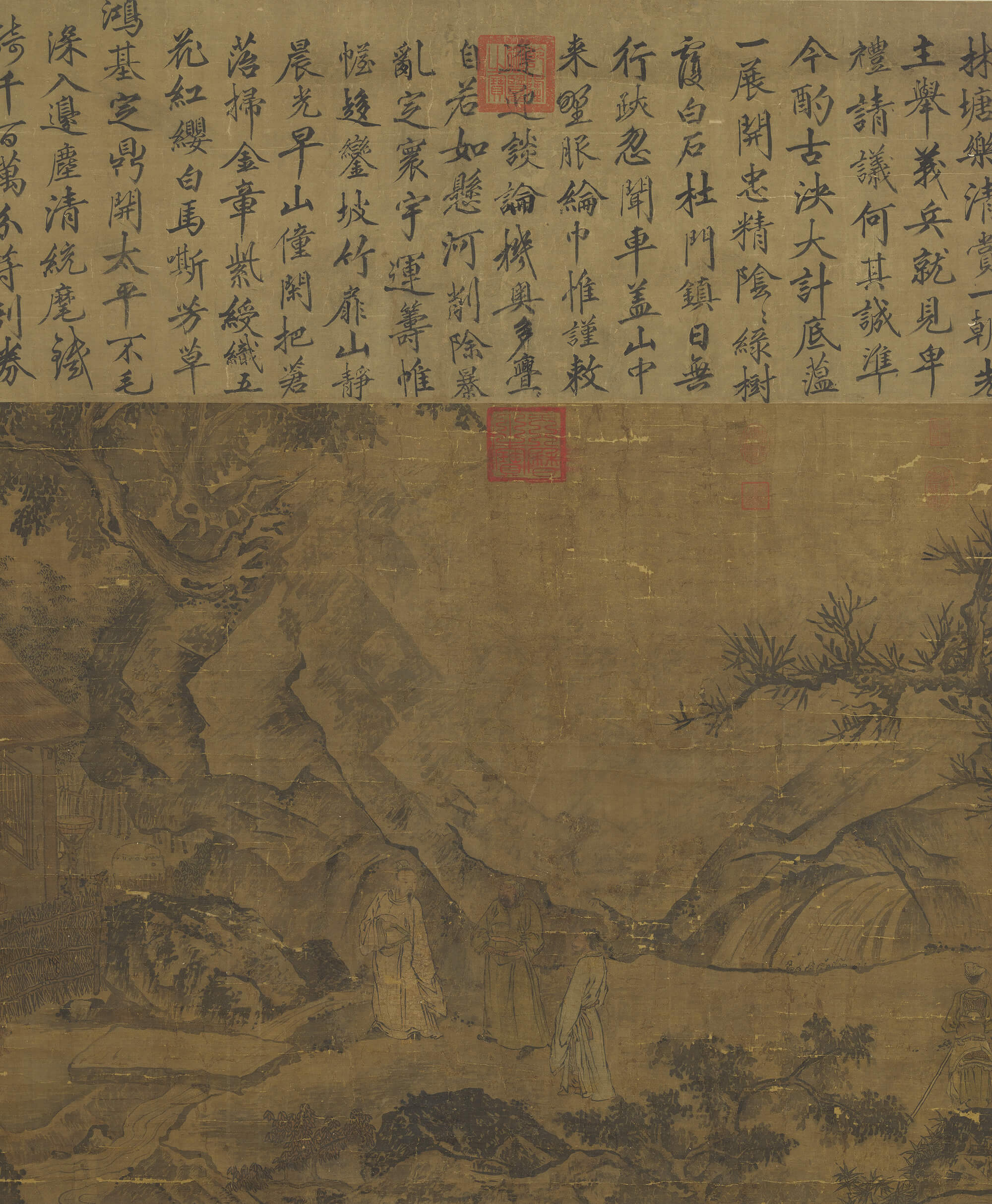

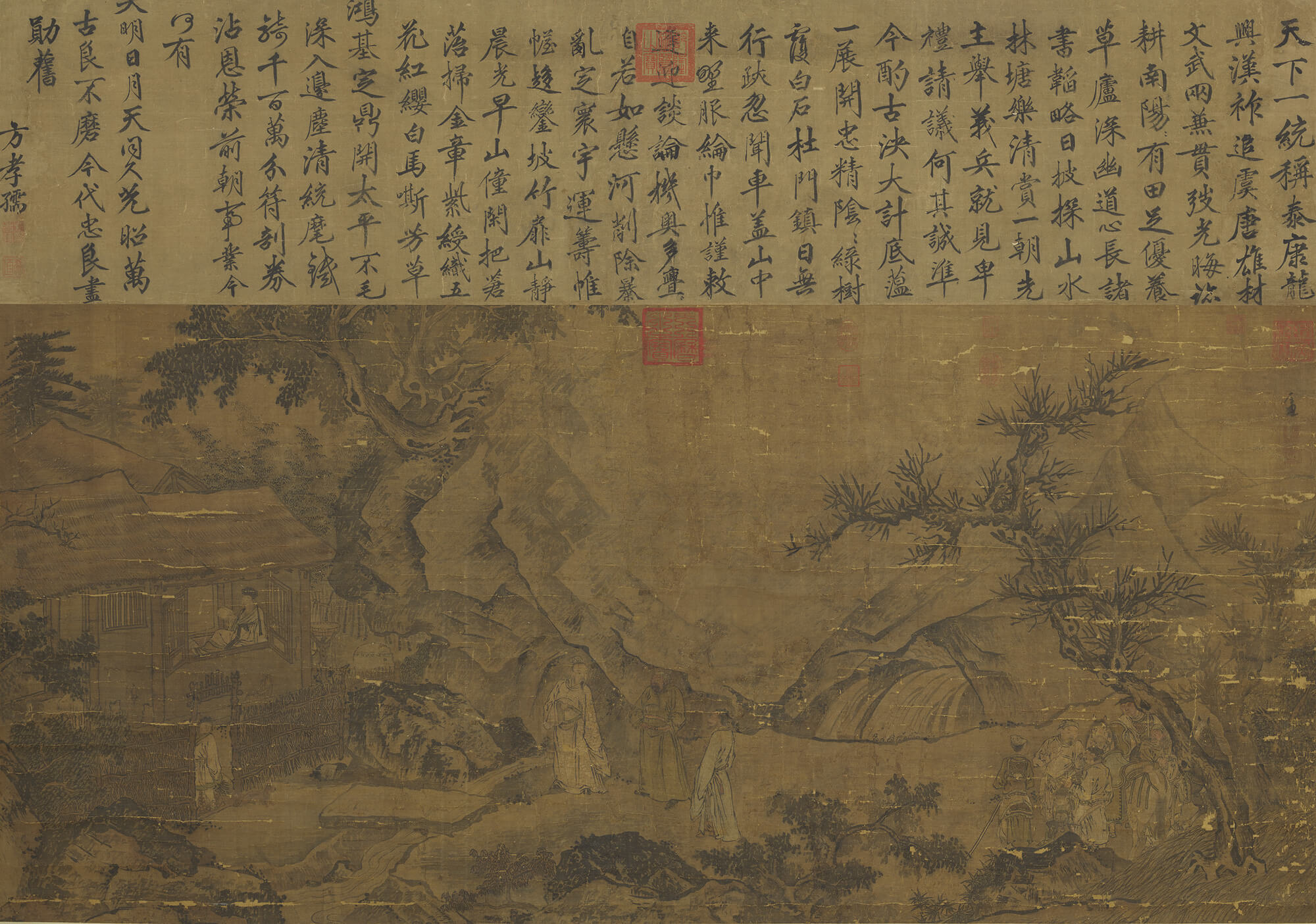

- Liu Bei's Third Visit to Zhuge Liang

- Attributed to Li Di, Song dynasty

- Silk

This painting depicts the late Han Dynasty tale of Liu Bei(161-223) making three visits to the recluse Zhuge Liang(181-234) living in seclusion in the mountains, inviting him to join his cause. The composition centers on a massive rock wall, which imitates a stage setting and serves as a backdrop for the main figures, drawing the viewer's gaze to the foreground. Liu Bei, Guan Yu(?-220) , and Zhang Fei(?-221) stand in front of the stone bridge, while their attendants and horses wait in the grove to the right. On the left, a young servant opens the door, and Zhuge Liang can be seen reclining by the window of his thatched cottage beyond the wicker gate.

The work shows signs of multiple repairs, and the signature of Li Di(fl. 1162-1224) was added later. The articulation of the landscape, trees, rocks, and figures is characteristic of Ming court painting, suggesting the work was created by an artist connected to that tradition.

Story Introduction: Three Visits to a Thatched Cottage

During the late Eastern Han dynasty, when warlords divided the country, Liu Bei followed the advice of his strategist Xu Shu and went with Guan Yu and Zhang Fei to visit the recluse Zhuge Liang at Wolong Gang in Nanyang to seek his assistance. Their first visit was in March; Zhuge, who was reading in his hut, had his servant claim that he was out at a banquet. In August, Liu visited Zhuge again, but Zhuge found another excuse to decline. On the third visit, Liu had his troops dismount and wait outside the thatched cottage. When informed that Zhuge was reading, Liu, Guan, and Zhang waited in the courtyard until Zhuge appeared and invited Liu inside to sit. Zhuge then analyzed the situation of the country and devised strategies, eventually becoming the military counsellor of Liu and later, the state of Shu.

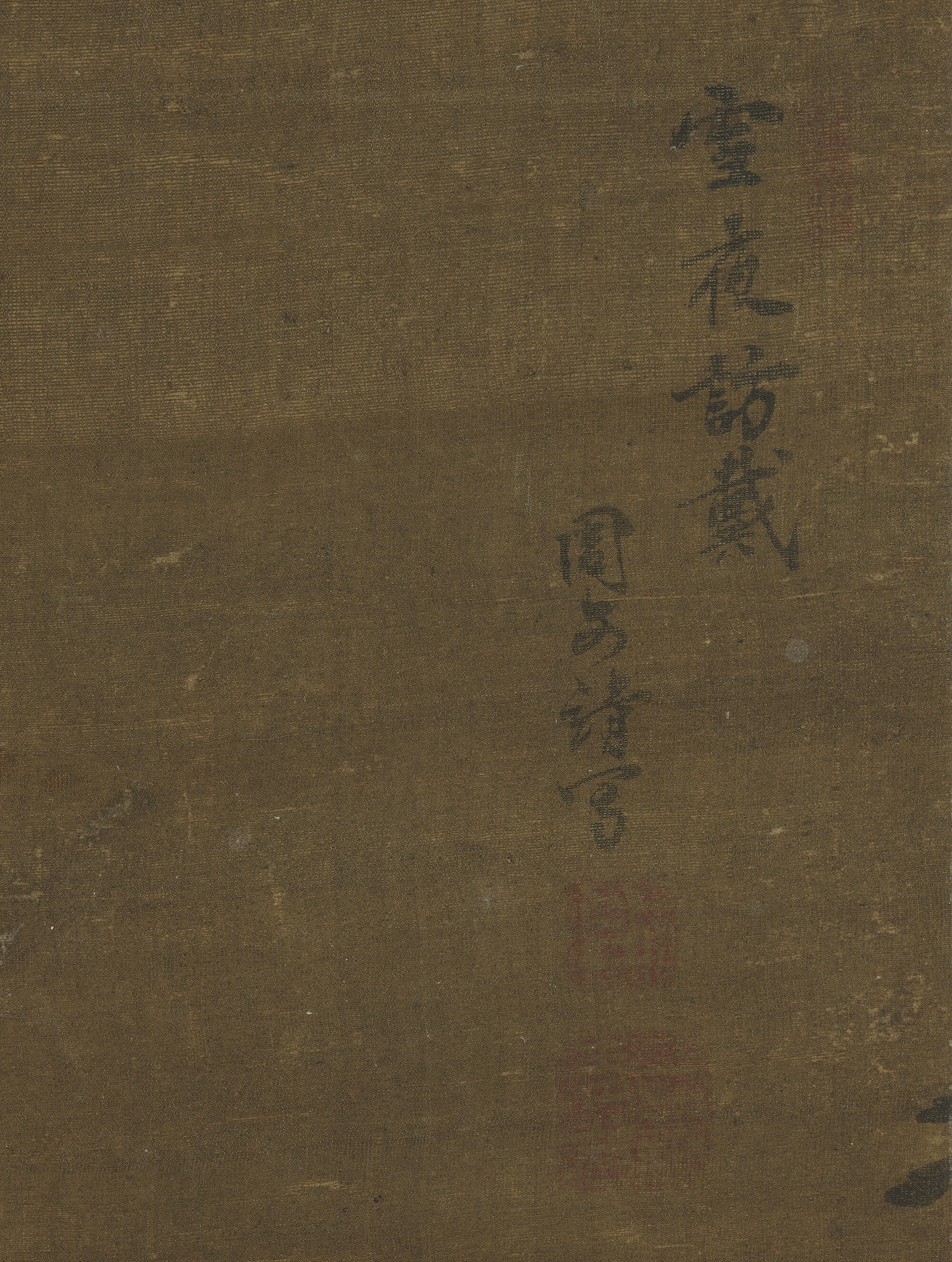

- Visiting Dai Kui on a Snowy Night

- Zhou Wenjing, Ming dynasty

- Silk

This painting portrays a story of a famous, self-willed literatus from the Eastern Jin. Waking from a dream on a snowy night, Wang Huizhi (338-386) was drinking alone under the bright moonlight when he was suddenly struck by the mood to visit a friend. He then ordered his attendants to quickly steer a boat to call on Dai Kui (c.331-396). When Wang arrived at the door, however, he changed his mind, leaving behind the famous saying, "I arrived in high spirits and departed content."

The styles of Southern Song artists Ma Yuan and Xia Gui are implied in the composition and brushwork, though the texture strokes of the rocks are sparse, perhaps to convey the effect of accumulated snow. The lone skiff cutting through the silence of the snowy night brings out the literatus's spontaneous nature, making this work a fine example of narrative painting from the Ming court.

Story Introduction: Visiting Dai Kui on a Snowy Night

On a snowy night, Wang Ziyou woke up from his sleep. He opened his door and ordered wine to be served. Surrounded by the pristine whiteness, he wandered inside his house reciting poetry. Suddenly, he thought of his friend Dai Kui and decided to visit him by boat immediately. After traveling through the night, Wang arrived at Dai's doorstep only to choose to return the way he came. When asked why he did this, Wang replied, "I went on a whim, and now that my whim has passed, it is natural to go back. Why must I see Dai Kui at all?"