Enlightening through Education, Upholding Social Relations: The Confucianist View of Painting's Primary Role

The 9th century art historian Zhang Yanyuan emphasized that the most important function of painting was to "enlighten through education and uphold social relations." The exhibition objects in this section reflect how these ideas were historically put into practice. Narrative paintings such as The Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety and Yuan An Lying Down in a Snowstorm were used to instill views on ethics and proper social relationships in the general public. Meanwhile, works such as The Mirror of Emperorship Illustrated Handbook and Wei Bin Fishing were intended to inspire rulers to learn from others and follow their example. The continued depiction of stories of loyalty, filial piety, integrity, and righteousness by artists across different time periods reflects such Confucian cultural ideals filtered through time and passed down through generations.

Stories of filial piety primarily relate the devotion of the protagonists when caring for their parents. Such narrative paintings of depictions of filial acts appeared as early as the Han dynasty in stone relief carvings. Biographies of Filial Sons, compiled by Liu Xiang during the Han dynasty, records the deeds of as many as 135 individuals. Bringing together known narrative texts and archaeological materials, it appears that the composition of the Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety underwent a complex evolution before reaching its present form.

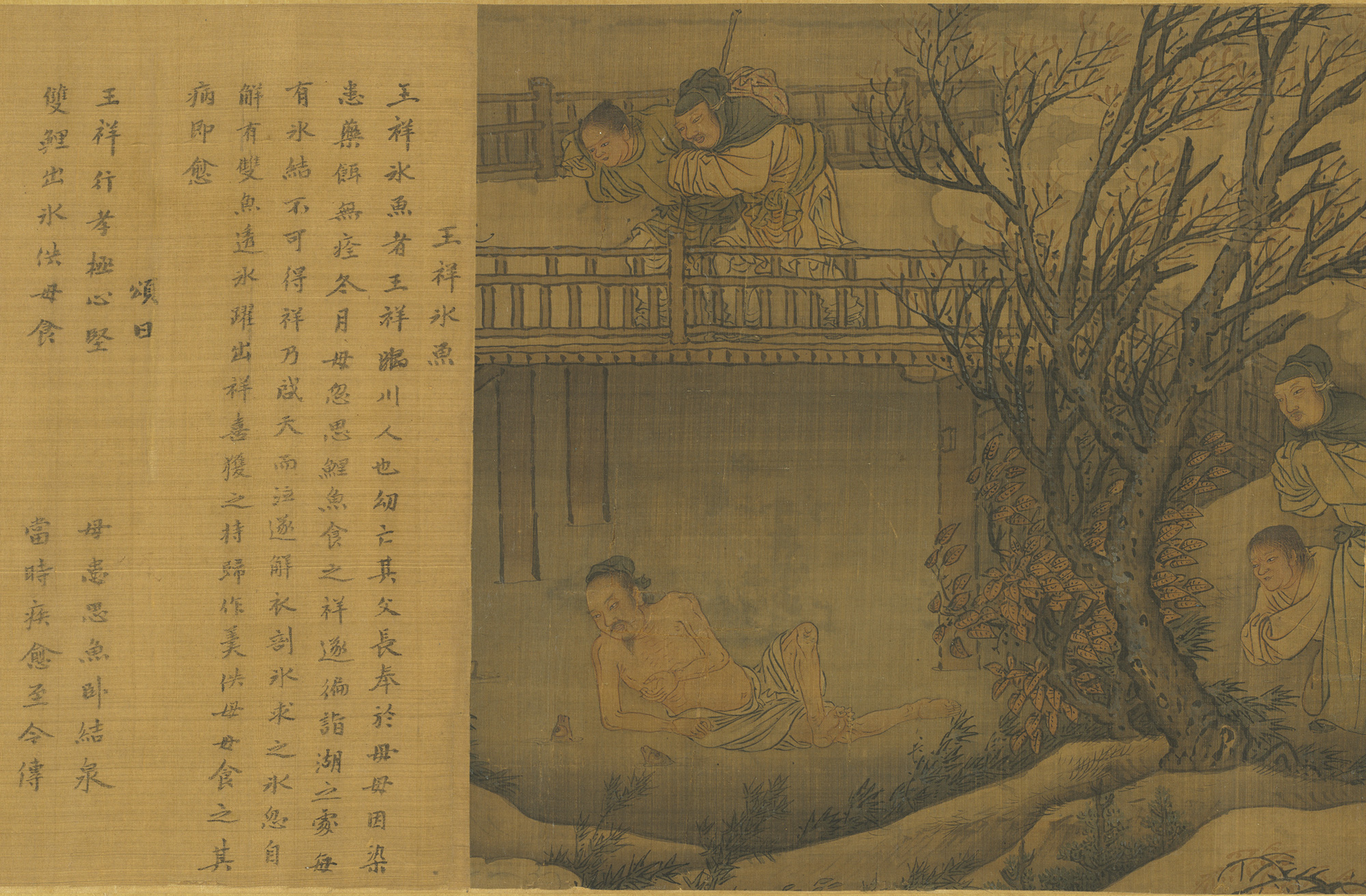

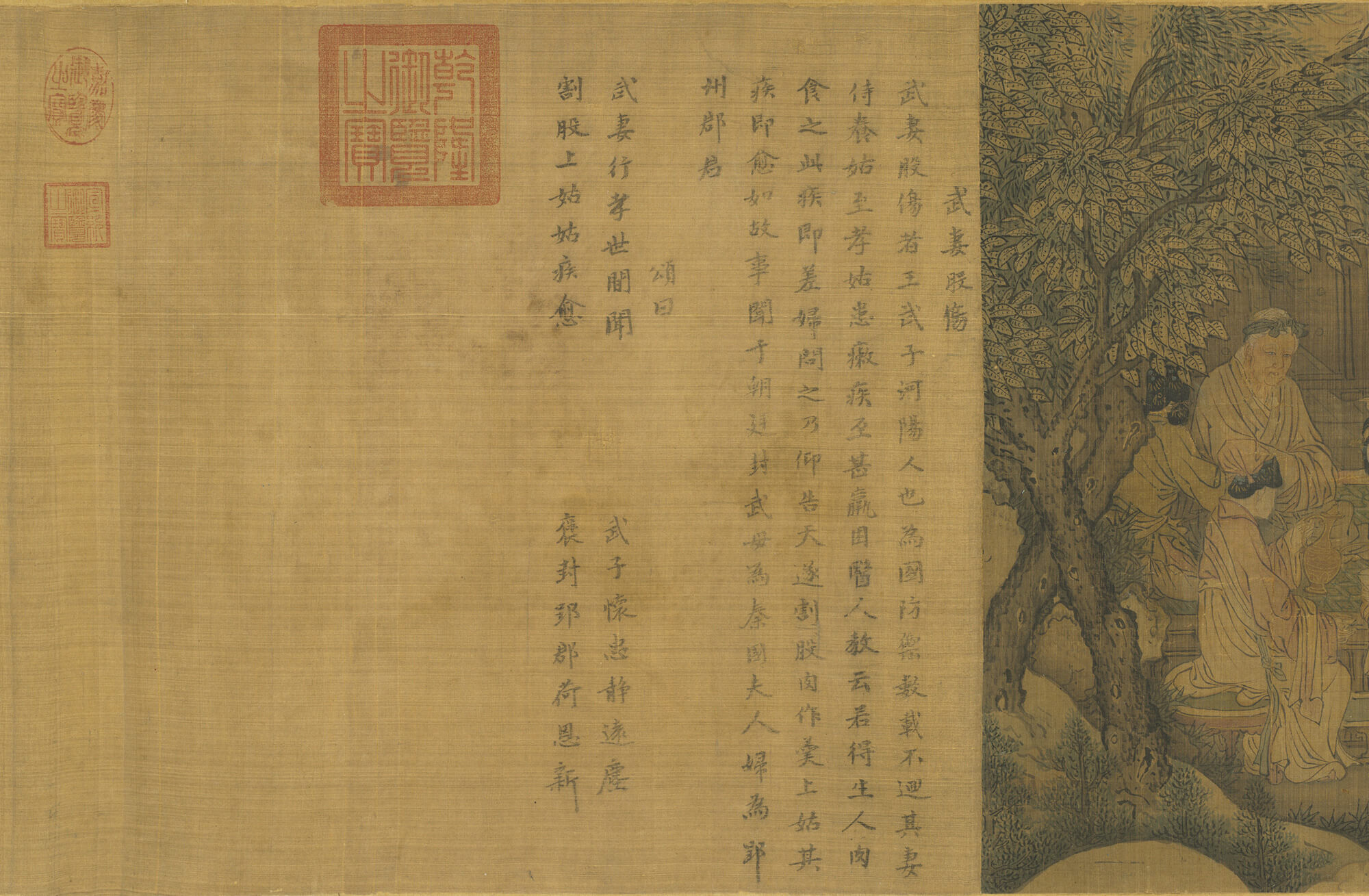

This exhibition includes Four Paragons of Filial Piety by an anonymous Yuan artist, which originally should have been part of a Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety series. Though most of the scenes have been lost, the four remaining sections—"Wu's Wife Cutting Her Thigh," "Lu Ji Hides Oranges," "Wang Xiang Laying on the Ice," and "Cao E Leaps into the River"—can be identified as belonging to a new grouping of Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety that became popular in northern China during the Song and Jin periods. Another notable feature of this new grouping is the inclusion of women's stories of filial piety, such as those of Cao E and the wife of Wang Wuzi.

In Four Paragons of Filial Piety by an anonymous Yuan artist, two storytelling techniques are employed. One method highlights dramatic moments in single scenes, evident in the depictions of "Lu Ji Hides Oranges for His Mother" and "Wang Xiang Lies on the Ice." A second technique integrates events from different times into a continuous composition. Other works in the exhibition similarly use single-scene depictions, with varying perspectives—one close-up and the other distant.

All three works feature "Wang Xiang Lies on the Ice." In the Yuan version, Wang Xiang, propped on his elbow with his mouth slightly open, reaches toward a carp emerging from the frozen lake, his expression one of disbelief. The harsh winter is conveyed through the landscape, attire, and the onlookers' gestures. In the Suzhou workshop version attributed to Qiu Ying, the artist captures the chill through withered branches, accumulated snow, winter birds, and cracks in the icy lake. The protagonist lies with arms wrapped around his chest, his face full of sorrow. In Jiang Pu's Qing version, a distant view presents a vast, bleak landscape. Unlike the other versions, it shows Wang Xiang's mother waiting inside a house. Wang appears in a lighter, more relaxed posture, resting his head on his arms as he lies on the ice. These variations in composition and arrangement reflect the distinct narrative focus of each artist.

- Four Paragons of Filial Piety

- Anonymous, Yuan dynasty

- Silk

This handscroll presents four stories of filial piety structured as images followed by text: "Wu's Wife Injures Her Thigh," "Lu Ji Hides Oranges for His Mother," "Wang Xiang Lies on the Ice," and "Cao E Leaps into the River." At the end of the scroll, Li Jujing (fl. 14th century) wrote a colophon emphasizing the importance of filial piety and fraternal duty in Confucianism, noting that this scroll serves a didactic purpose as "a resource for self-cultivation and a method for instructing one's children." Based on the markings from replacing the title slip and textual analysis, it is likely a surviving fragment of a Twenty-Four Paragons of Filial Piety scroll.

The entire work is meticulously rendered, its figures done in fine, fluid, yet energetic lines, and characterized by its distinctive nailhead and rats' tail brushwork. This style may be connected to the lineage of the 13th century figure painter Liu Guandao.

- Story Introduction: The Loyal Wife's Thigh Wound

Wang Wuzi, who had been guarding the frontier for years, left his wife at home to care for his mother. His mother contracted leprosy, which nearly blinded her. Someone suggested to his wife that if she could feed her mother-in-law the flesh of a living person, she would recover quickly. The wife then prayed to god, cut off a piece of her thigh, cooked it into a soup, and fed it to her mother-in-law. Remarkably, her mother-in-law recovered fully and swiftly. When the court heard of this, it honored the mother-in-law with the title "Lady of the State of Qin" and the wife as "Lady of Yingzhou" in recognition of her filial piety.

- Story Introduction: Lu Ji's Oranges

When Lu Ji was six years old, he went to visit Yuan Shu, who invited him to a feast. Noticing some oranges on the table, Lu secretly slipped a few into his sleeve to take home for his mother, who loved oranges. As he was leaving, the oranges fell out. When asked why he had them, Lu replied, "I wanted to bring them home for my mother." Yuan admired Lu's filial piety and encouraged him to continue his filial ways. Lu's reputation for filial piety spread to the court, and he was later appointed as a governor.

- Story Introduction: Wang Xiang and the Ice Carp

Wang Xiang, who had lost his father at a young age, devoted himself to caring for his mother. When she fell ill and there was no medicine to cure her, she expressed a craving for carp one winter. Unable to find fish due to the frozen lake, Wang prayed to god and then stripped down to melt the ice with his body heat. Suddenly, the ice cracked open, and two carp leaped out. Overjoyed, Wang cooked the fish into a soup for his mother, who soon recovered.

- Story Introduction: Cao E Dives into the River

At the age of 14, Cao E's father died after jumping into a river, and his body was never recovered. Heartbroken, Cao E stood by the river and wailed for seven days and nights, eventually throwing herself into the river as well. Three days later, she emerged from the water, holding her father's body. The villagers were moved by her filial piety and buried the father and daughter together, erecting a monument by the river in their memory. The story of her devotion spread far and wide, earning widespread admiration. Another version states that, Du Shang, the Governor of Jingzhou, had a monument made for her at the Shangyu Mountain, making her an exemplar of filial piety for generations to come.