A Pleasure for the Eyes and Soul: Pictures for Entertainment

Setting aside the solemn directive of " Enlightening through Education and upholding social relations," let us immerse ourselves in the images and imagine or simply feel the joy they bring out in these literary, theatrical, and novelistic storylines. This pleasure may be the central appeal of narrative paintings. It is found in the melancholy of torn loyalties between nation and family in Lady Wenji's Return to China, the ambiguity and risk in the first awakening of love in The Romance of the Western Chamber, and the sense of liberation in Returning Home from unfulfilled ambitions and the unwillingness to debase oneself leading to retirement from official work. These artists, having transformed all kinds of plots and texts into captivating images, offer a visually delightful and emotionally resonant perspective on understanding these stories.

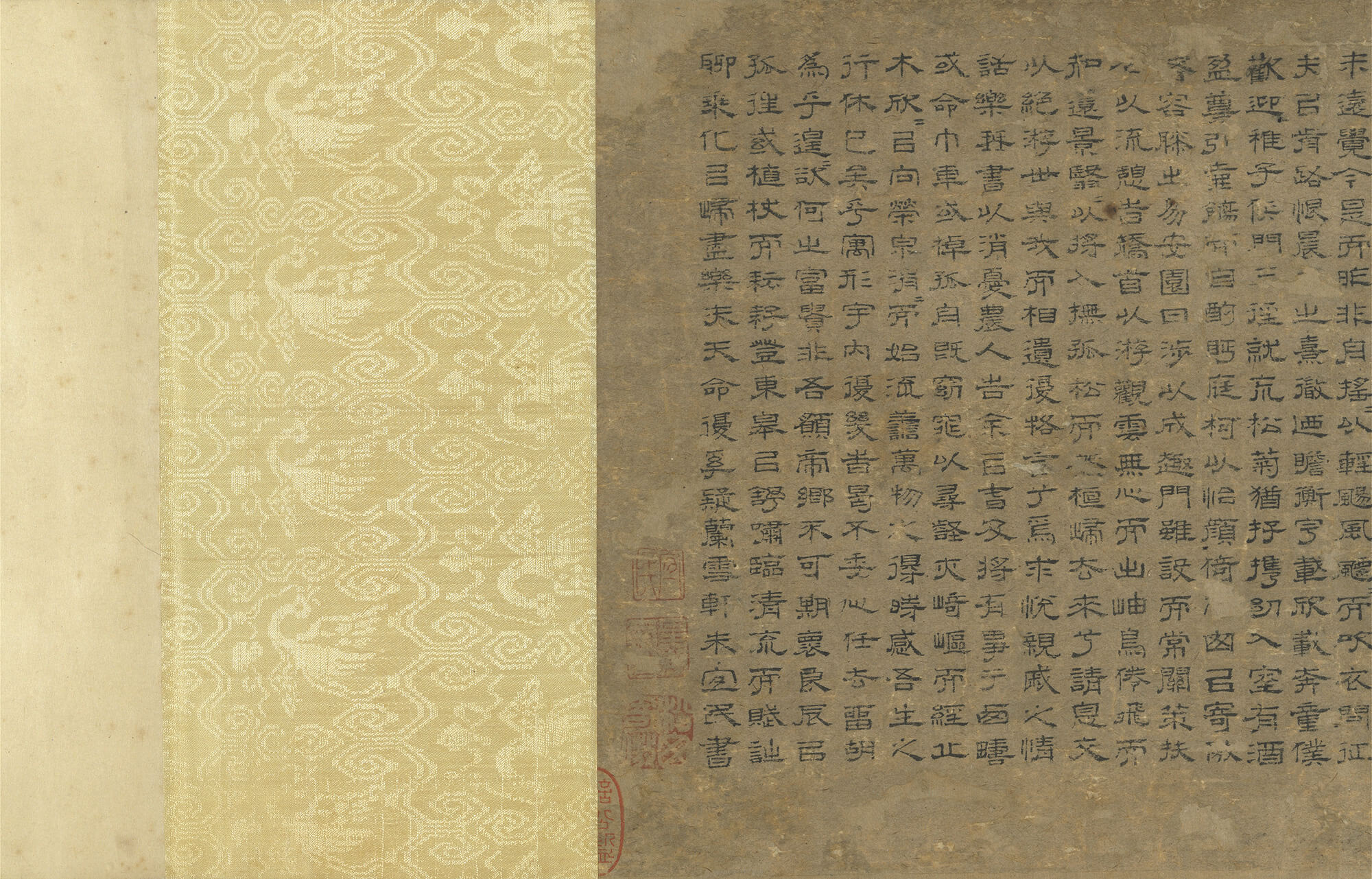

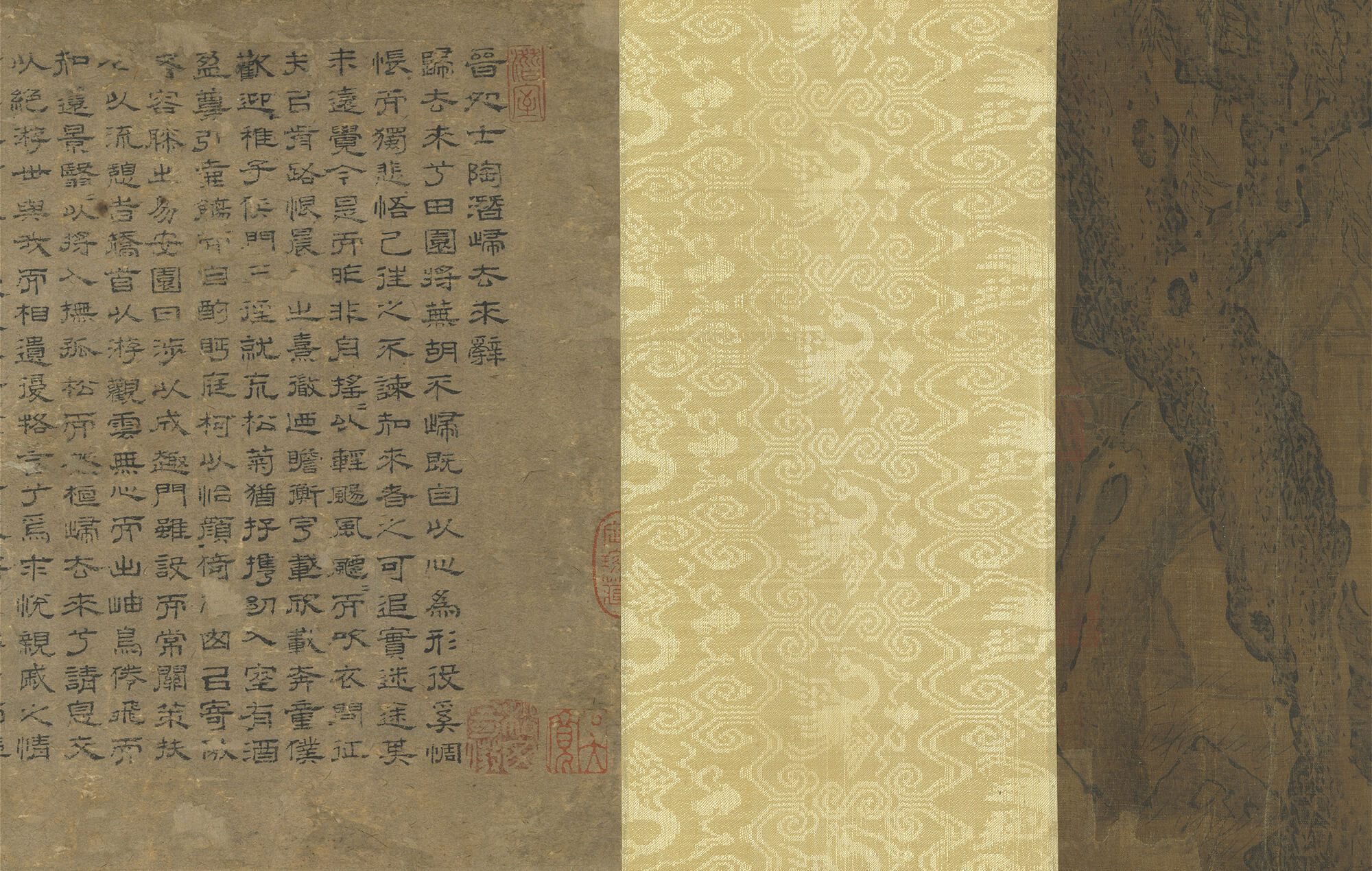

- Illustration of the "Homecoming Ode" by Tao Yuanming

- Attributed to Zhao Mengfu, Yuan dynasty

- Silk

Tao Yuanming (c. 365–427) holds an iconic status among premodern scholars. Tao explains in the preface to his "Homecoming Ode" that after serving as an official for around 80 days, he followed his instincts and resigned, returning home. His writing on an idyllic, pastoral life and being indifferent to fame or gain became an ideal for those seeking reclusion.

The painting likely depicts Tao Yuanming's journey home, described in the text as "joyfully rushing back." Instead of laughing heartily and running, a scholar is portrayed walking stiffly with a staff, his robes floating in the breeze. Attendants carrying a qin, scrolls, and a wine jar, and five willow trees at the entrance to Tao's home are all details cleverly added by the artist. They transform the brief poetic passage into a complex visual narrative.

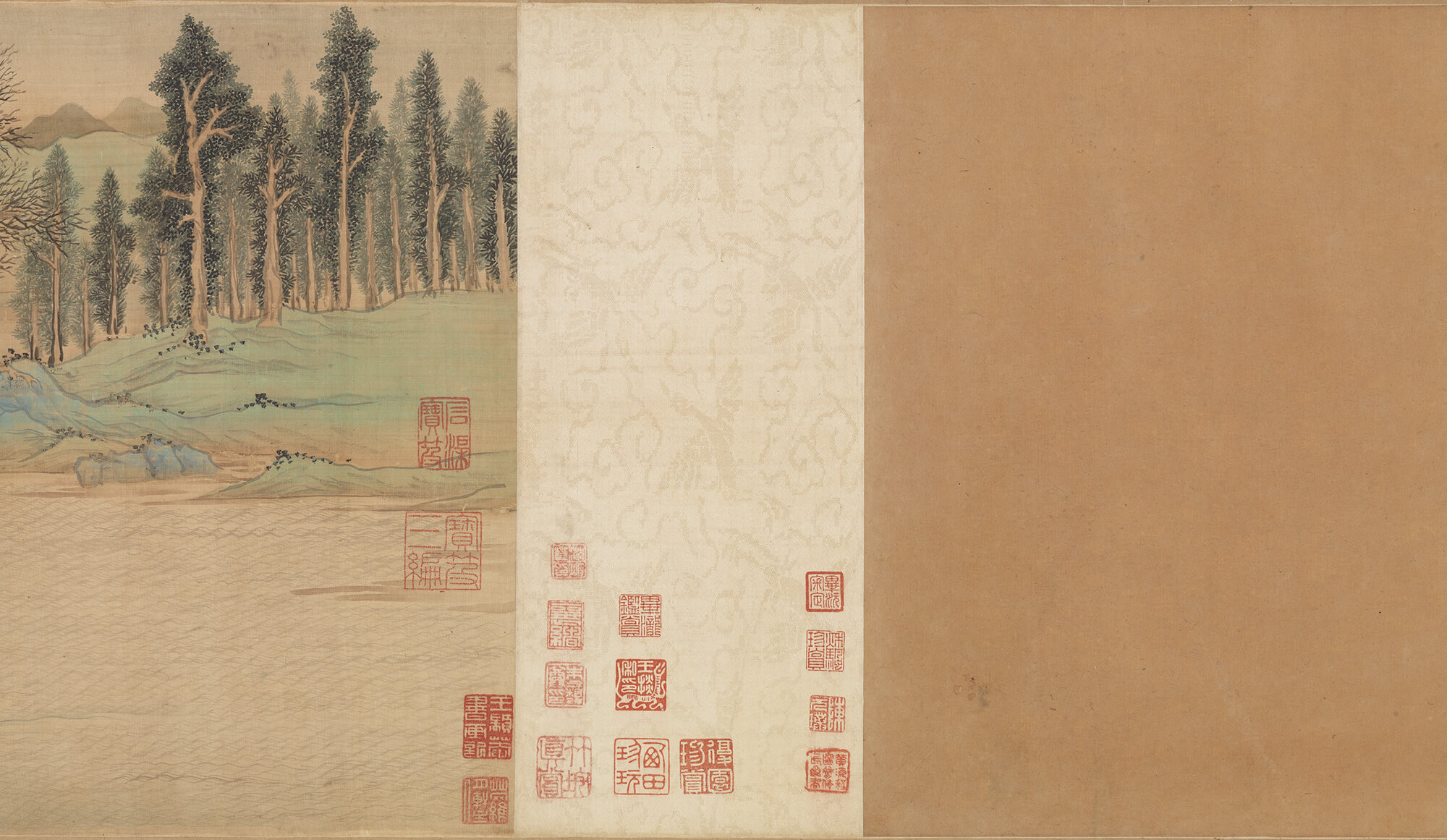

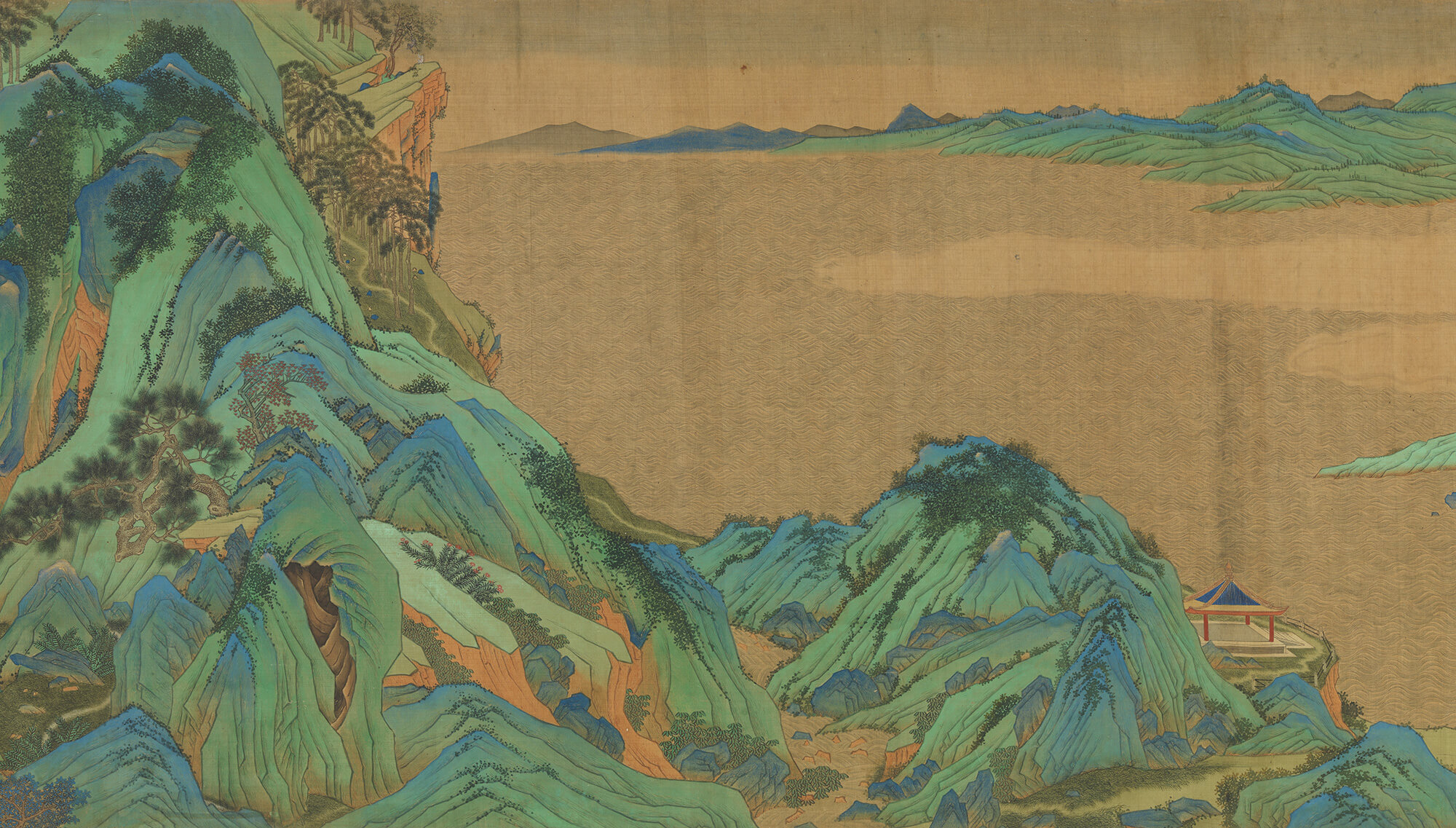

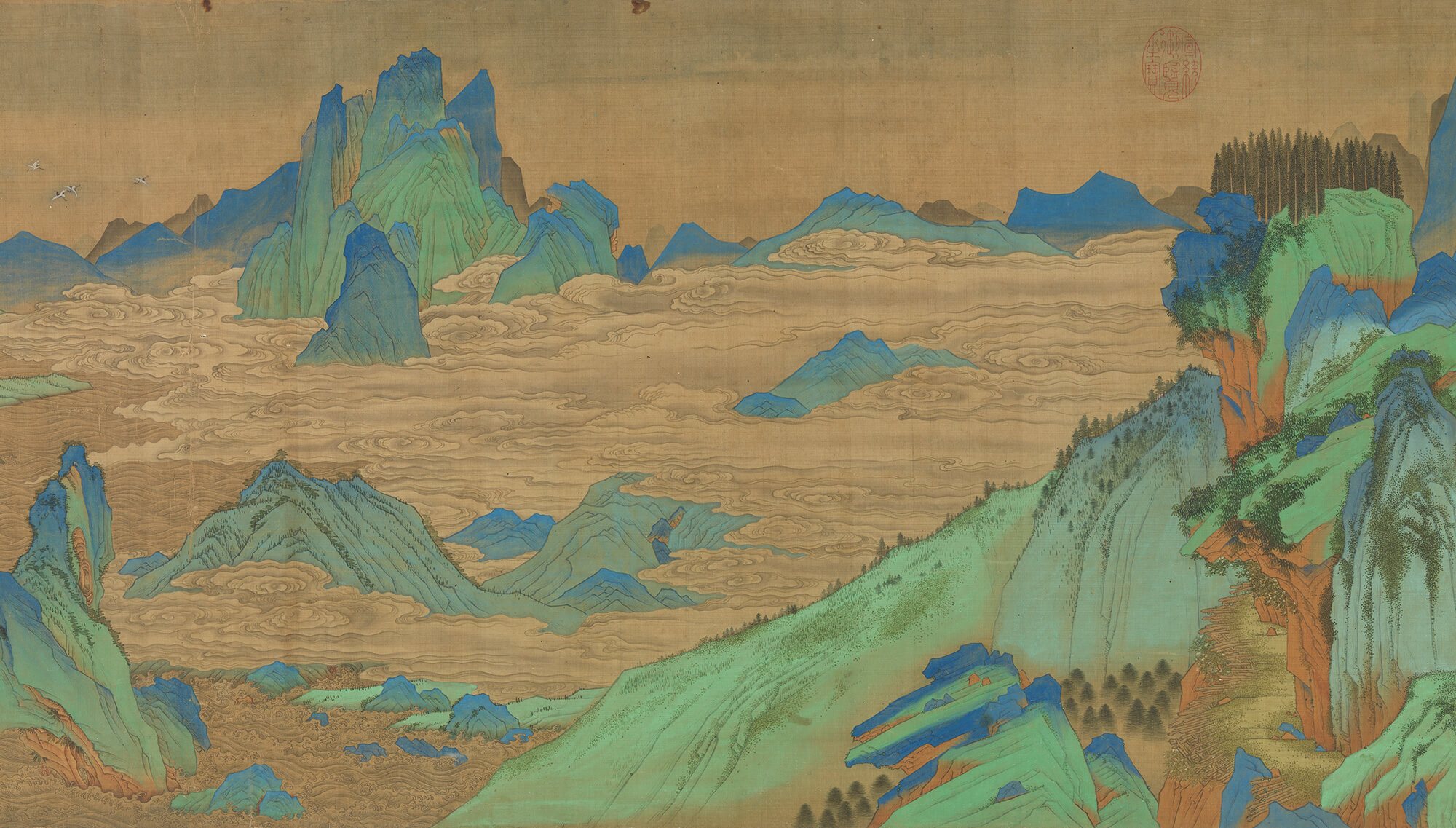

- After Zhao Bosu's Latter Ode on the Red Cliff

- Wen Zhengming, Ming dynasty

- Silk

Alongside Tao Yuanming, Su Shi (1037–1101) was another figure beloved by scholars, with his "Ode on the Red Cliff" becoming a widely celebrated literary subject.

Wen Zhengming (1470–1559) painted this scroll at the age of 79, using what appears to be interlinked landscapes and trees to ingeniously differentiate the various sections of the text. Another work on display—"Homecoming Ode" attributed to Qiu Ying—also imitates this approach. In this painting, the rocks are piled one upon another, and the trees are scattered in a way that is well-knit yet full of variation. The artist channels his understanding and interpretation of Su Shi's work into the exceptionally beautiful hills and valleys, overlaying two art forms in a visually delightful way.

Story Introduction: Latter Ode on the Red Cliff

Su Shi and his friends were reciting poetry and admiring the moon when he suddenly lamented the absence of fine wine and delicacies. Fortunately, his friend had caught fish that evening, and Su's wife informed him that they had wine at home. Thus, they took the food and drink for a revisit to the Red Cliffs. However, the dramatically changed scenery of the Red Cliffs made the place feel unfamiliar to Su, prompting him to climb the cliffs to see the river and mountains up close. As he traversed the rugged forest and reached the summit alone, he could not help but let out a long, loud howl, feeling as if all of nature moved with him. The grandeur of nature filled him with a sense of solemn respect mixed with sorrow and fear. Afterwards, he returned to the boat and roamed on the river. Suddenly, a lone crane broke the silence, crying out as it flew past his boat. Later, Su dreamed of a feather-robed Taoist priest, realizing that the priest might have been the crane he saw the night before. He awoke from the dream startled, opened his door to search for the priest, but to no avail.

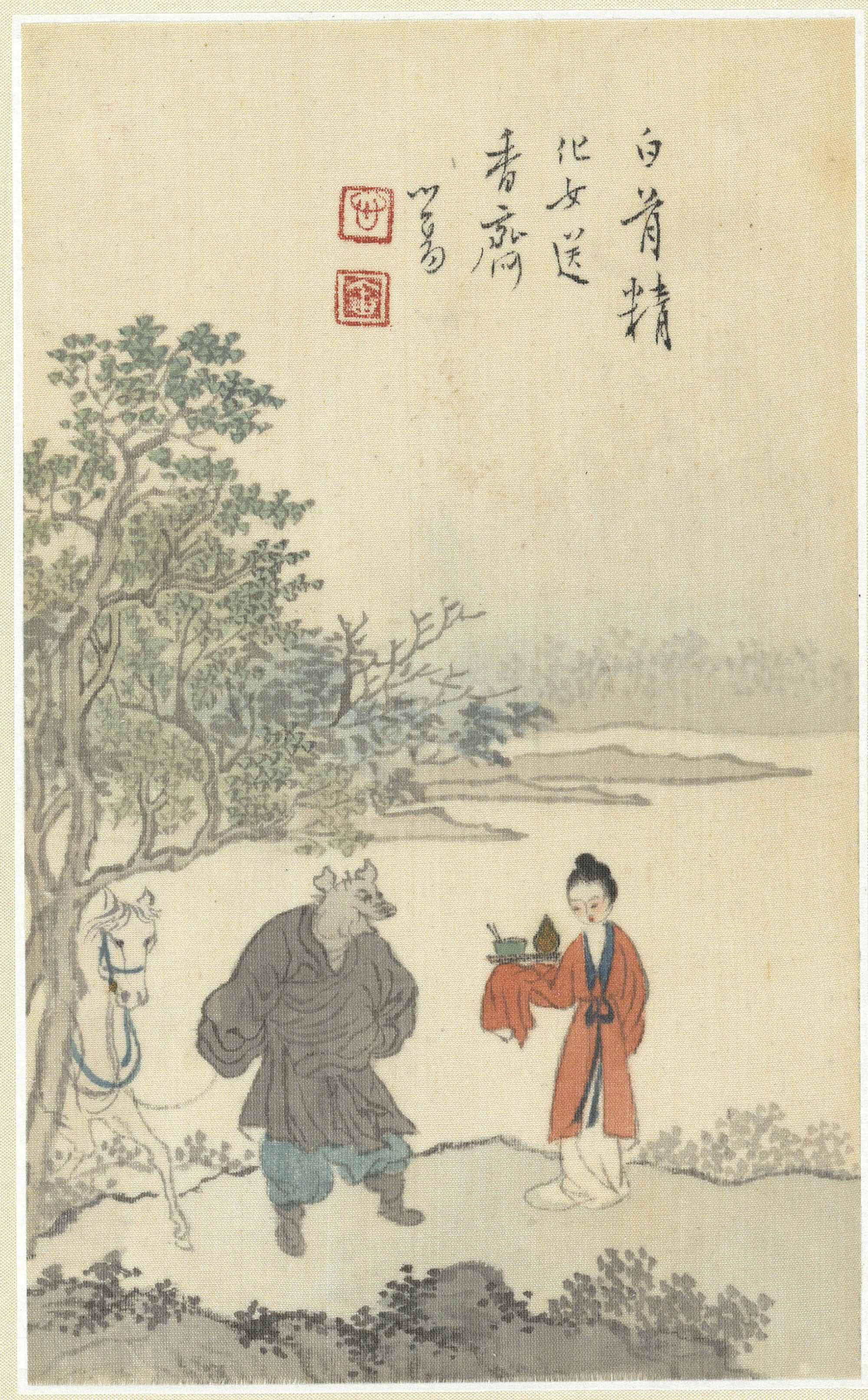

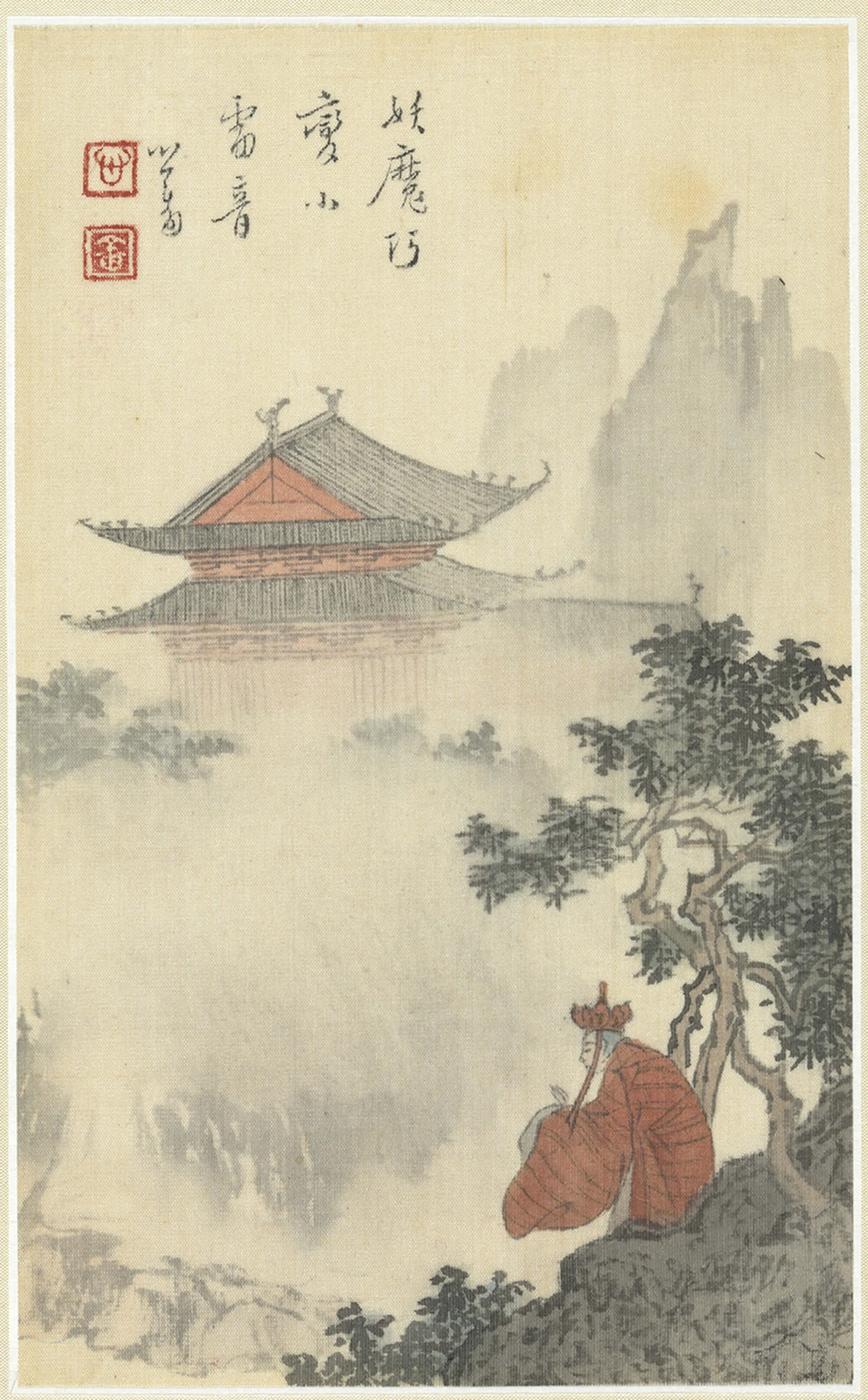

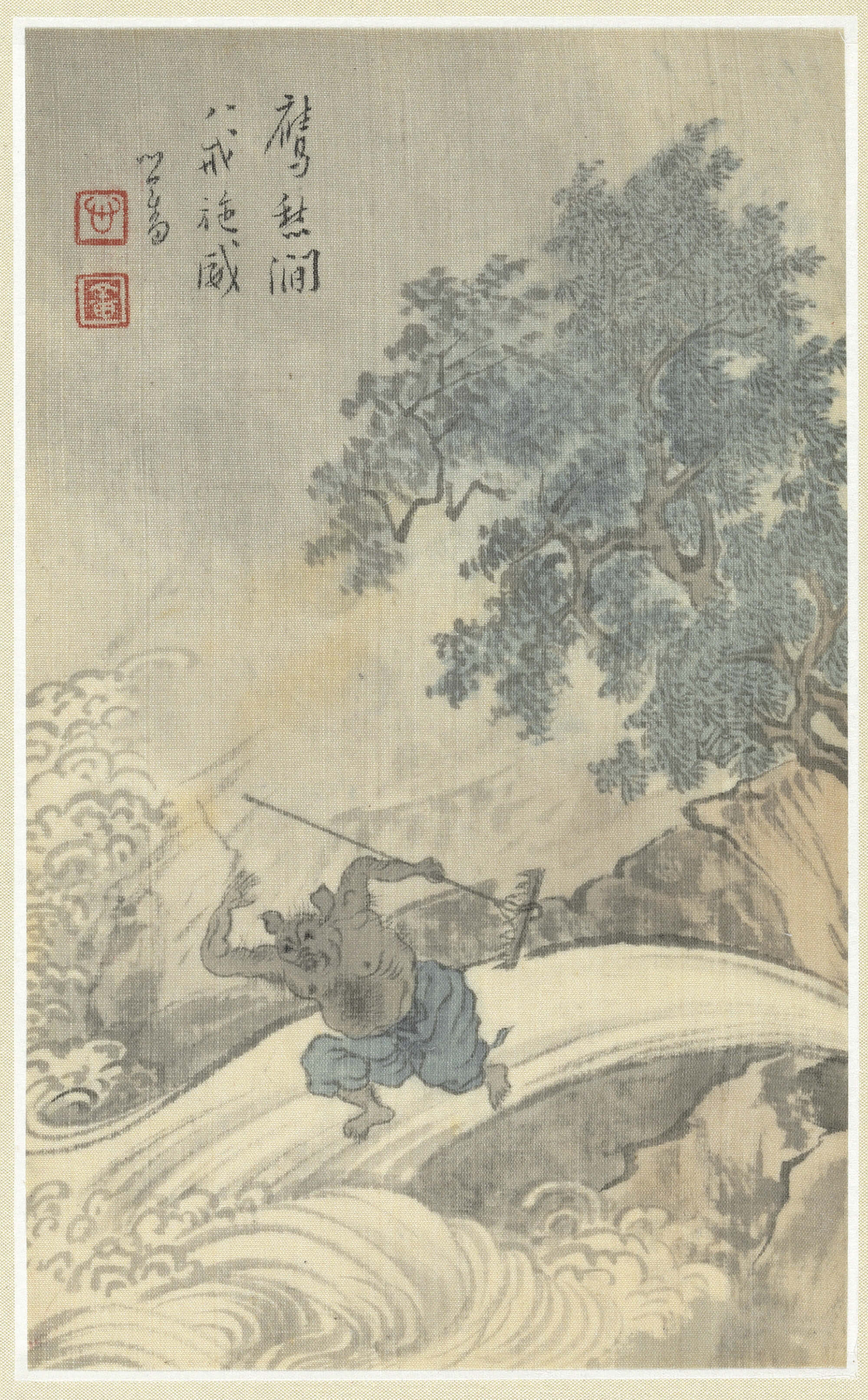

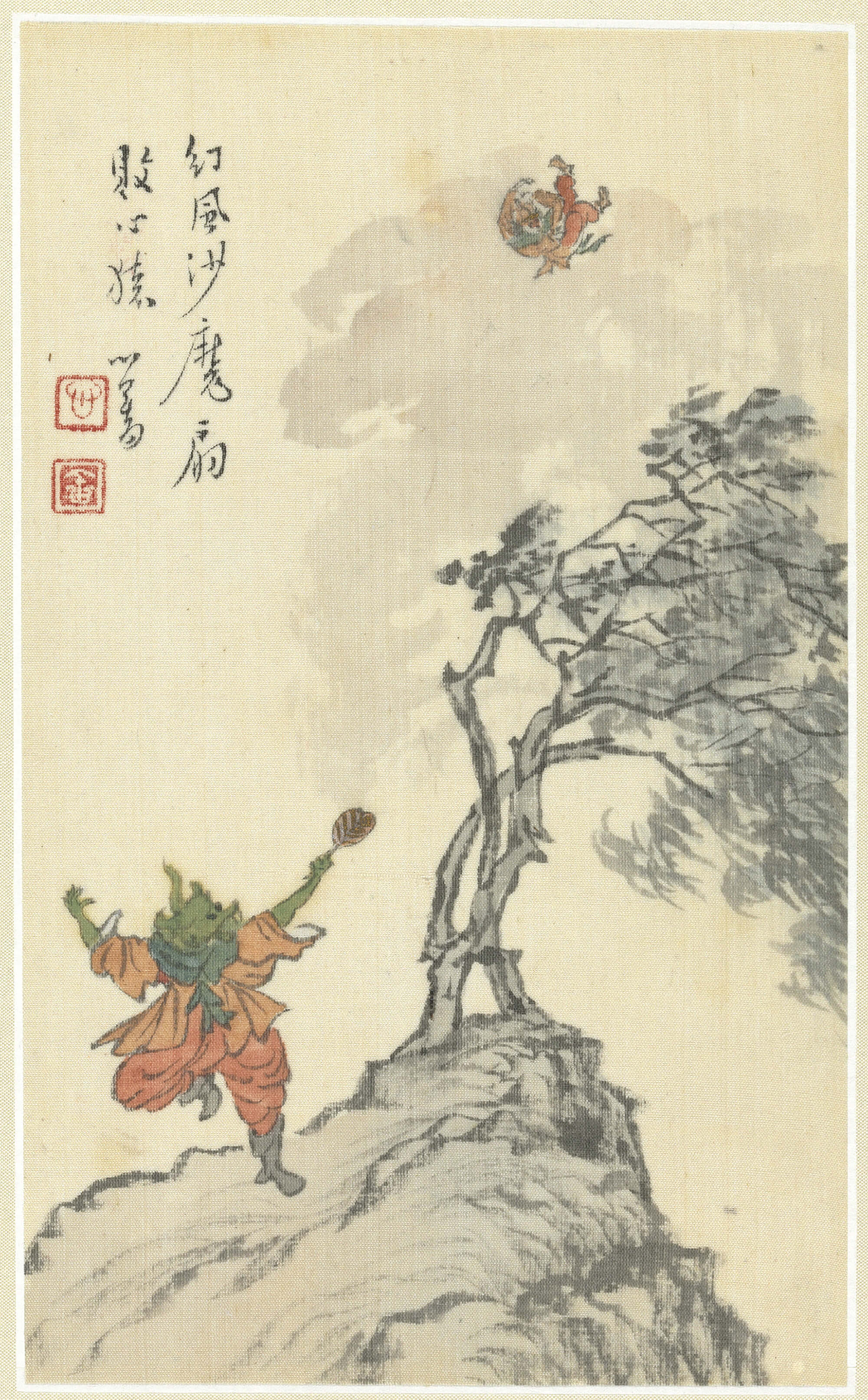

- Journey to the West

- Pu Ru, Republican period

- Silk

The story of the monk Xuanzang, accompanied by Sun Wukong, Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing on their pilgrimage to retrieve Buddhist scriptures from India, has remained a subject of interest for generations in novels, plays, and even modern video games. The author of this album Pu Ru(1896-1963) held a deep affection for Journey to the West. His friend Zhang Muhan (1902–1980) observed that when Pu Ru painted Sun Wukong, "it was when his spirit became one with heaven, and his mind roamed beyond worldly matters—it was when he was happiest." The artist's goal was not to provide a complete narrative, but to capture the story's joyous, exciting moments that would make the viewer smile. With nimble brushstrokes, the main characters from this work of popular literature appear vividly in the refined landscapes typical of literati painting.

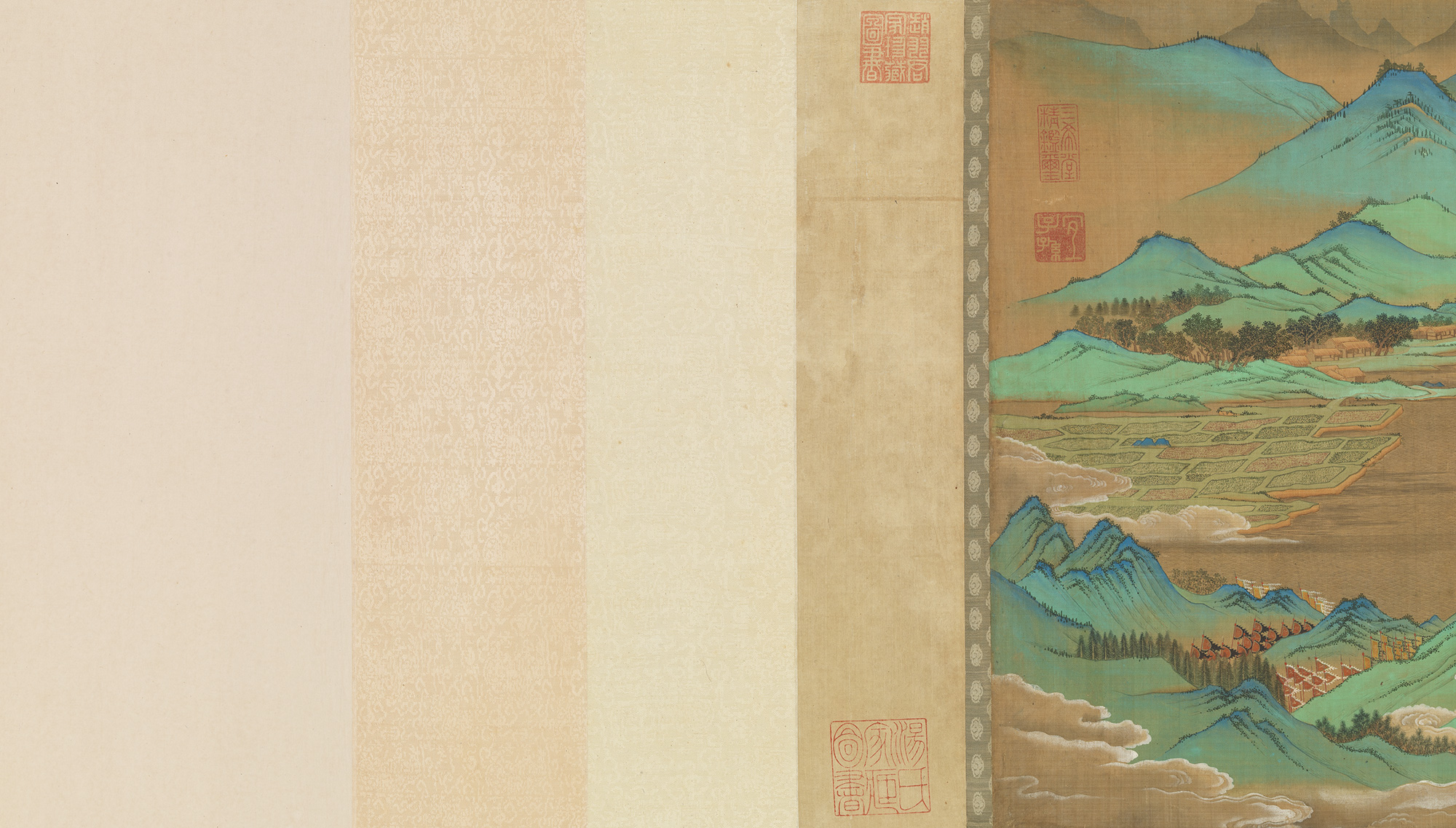

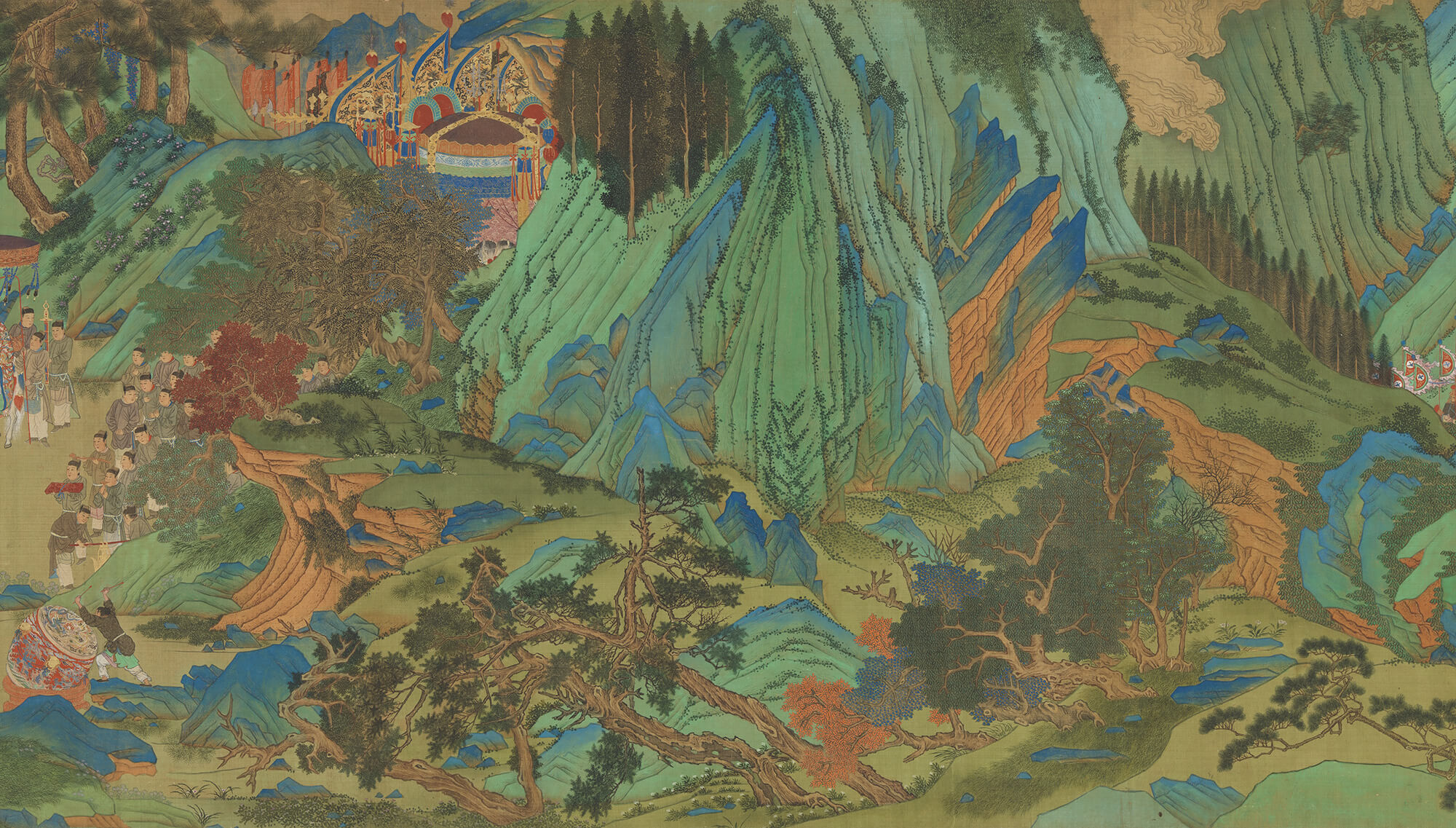

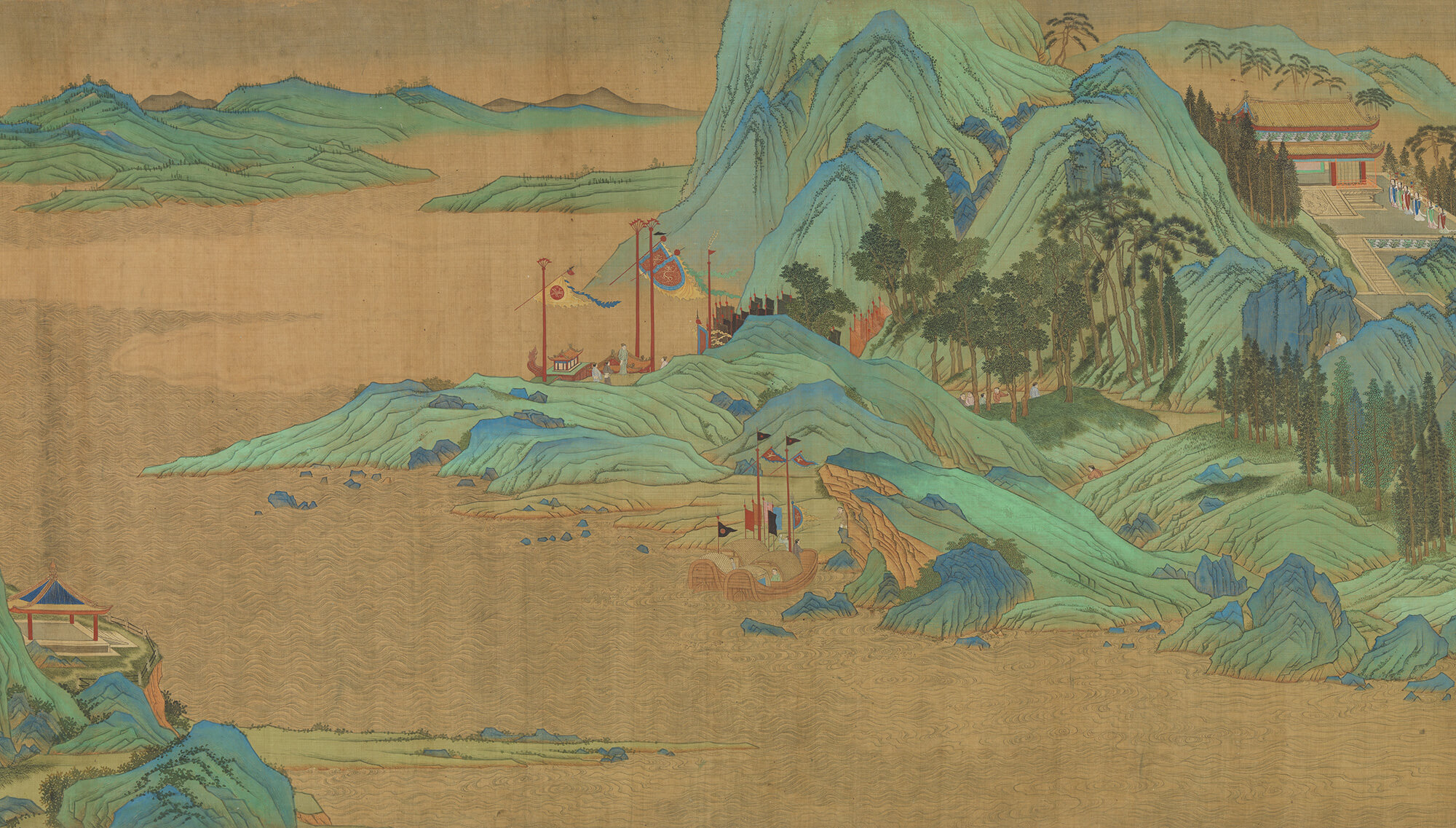

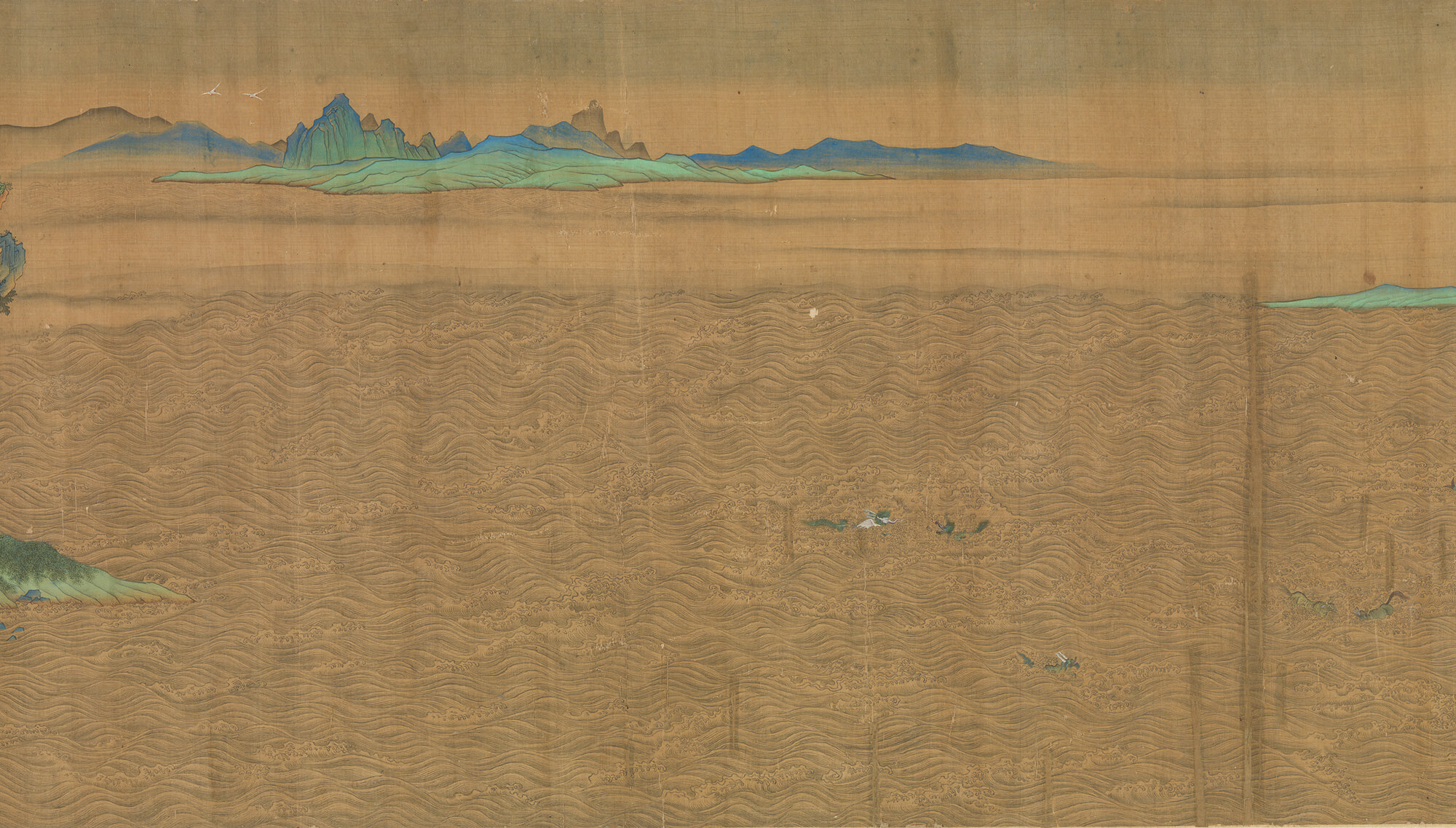

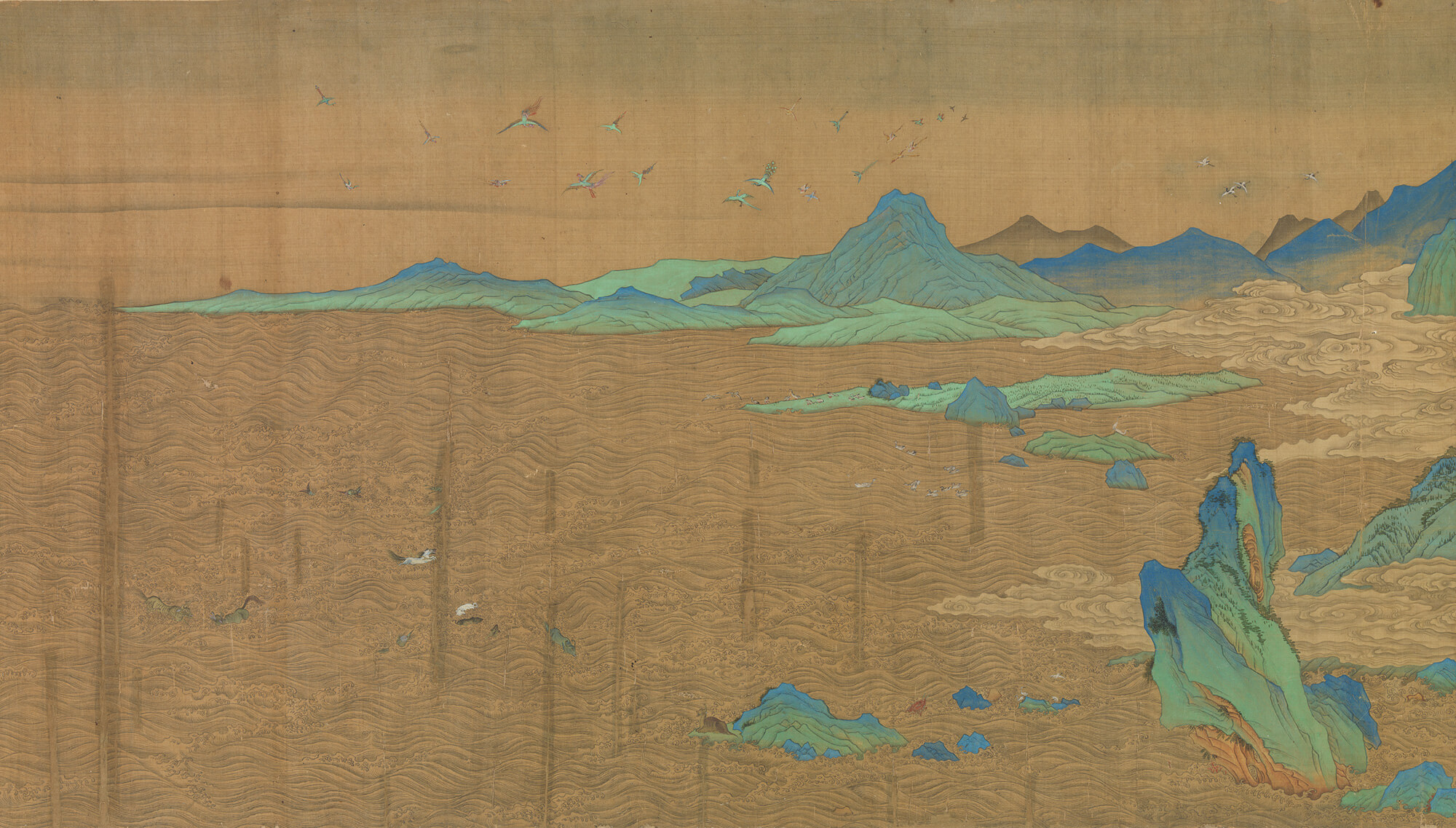

- Hunting at Shanglin Park

- Anonymous, attributed to Yuan dynasty

- Silk

Although "Ode on the Shanglin Imperial Park" is a work of literature, it unfolds in the form of a narrative. The painting Shanglin Park is based on the fu or ode, divided into seven main sections. The scroll begins with a bombastic debate between the characters Zixu, Wuyou, and Wushi. It then portrays the majestic imperial park: mythological creatures come and go amid vast bodies of water and sumptuous palaces nestle among peaks rising one upon another. The emperor appears on the scene, surrounded by an imposing entourage of carriages and insignia, as he inspects the soldiers hunting animals in the woods. The scene shifts to a banquet on an elevated terrace, where the emperor, accompanied by his consorts, suddenly realizes he should not be living in extravagance and self-indulgence. He then decides to stop drinking, halt the hunt, and ride back to the palace.

The artist uses mountains to connect the seven sections of the "Ode on the Shanglin Imperial Park", creating a vast, expansive landscape. Mineral pigments like azurite and malachite increase the bright, saturated effect of the peaks. The intricate patterns and many hues of the clothing and objects impart the entire painting with a richly ornamented effect. The rhapsody's words have been transformed into a sumptuous picture, challenging the viewer's original imagination of the text.