The Narrative Power of Images

Images that contain narratives take various forms across different mediums. Some were specifically created to serve a storytelling purpose, such as stone relief carvings depicting tales of loyalty and filial piety in tombs and ancestral shrines, the Jataka tales found in the murals of Dunhuang, the transformation stories illustrated on Lotus Sutra frontispieces, and historical events. There are also images that were not originally intended to be "stories," such as the illustrations accompanying philosophical or literary classics like the Classic of Filial Piety or the Book of Odes. Yet, due to the inherent narrative power of images, they offer viewers a sense of plot development that surpasses what is found in the texts.

- Rubbing of Stone Carved Portrait of the Wu Family Shrine

- Eastern Han dynasty

- Paper

The Wu Family Shrine, dating to 151 CE, features stone relief carvings that decorate the entire interior and resemble paper-cut silhouettes. These rubbings from the two central registers of the west wall of the shrine depict seven stories of loyalty and filial piety, including "Lao Laizi Entertains His Parents" and "Jing Ke Assassinates the King of Qin."

Within a single scene, the artist uses the directionality of the characters and inscribed cartouches to help viewers identify each story. Many of the characters' movements are exaggerated while still retaining a level of detail. For instance, in the third register to the left, the carving of "Jing Ke Assassinates the King of Qin" shows Jing Ke's open palm and how the King's guards attempt to grab and capture him. The artist uses fine linework to add nuances beyond the textual narrative.

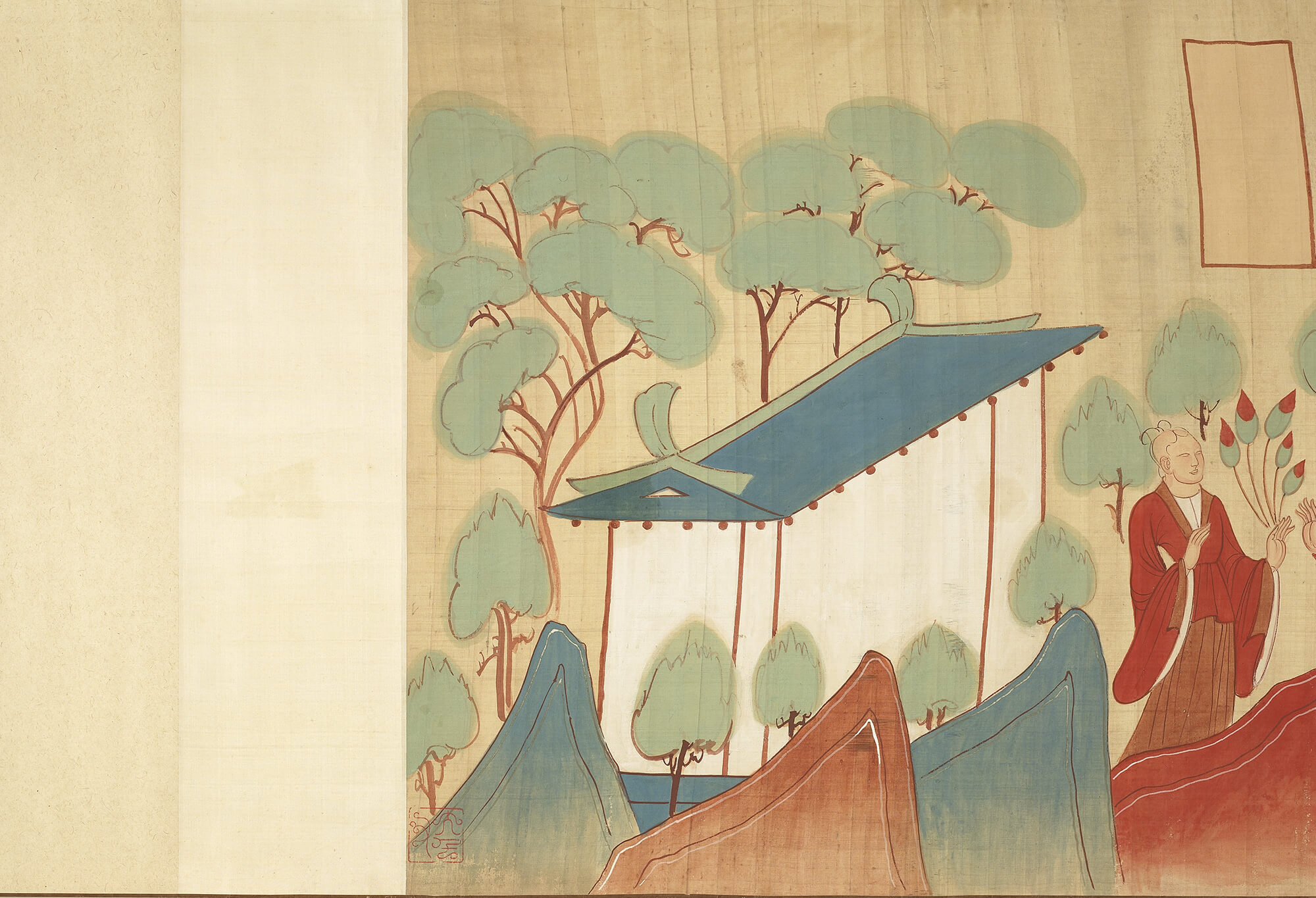

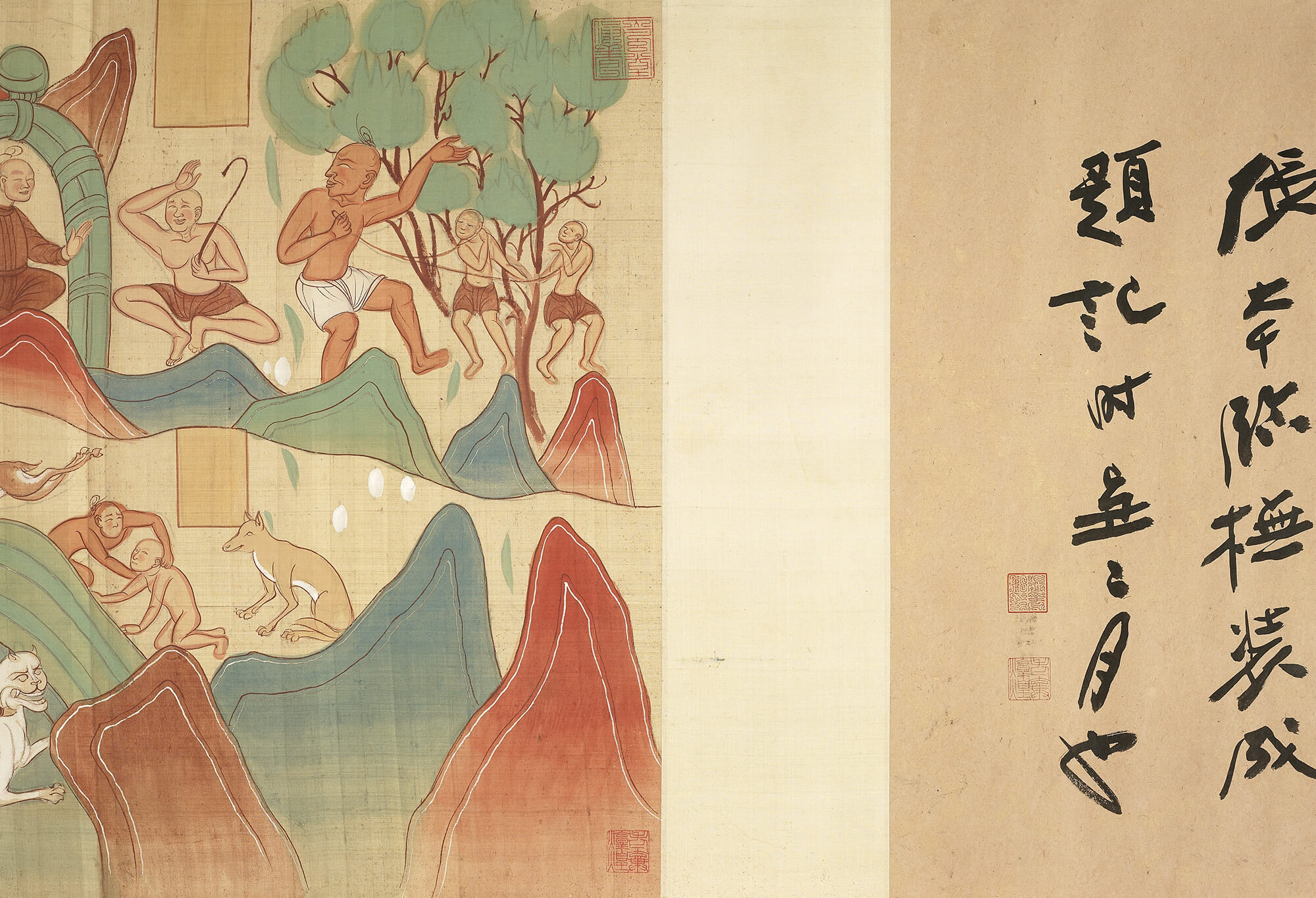

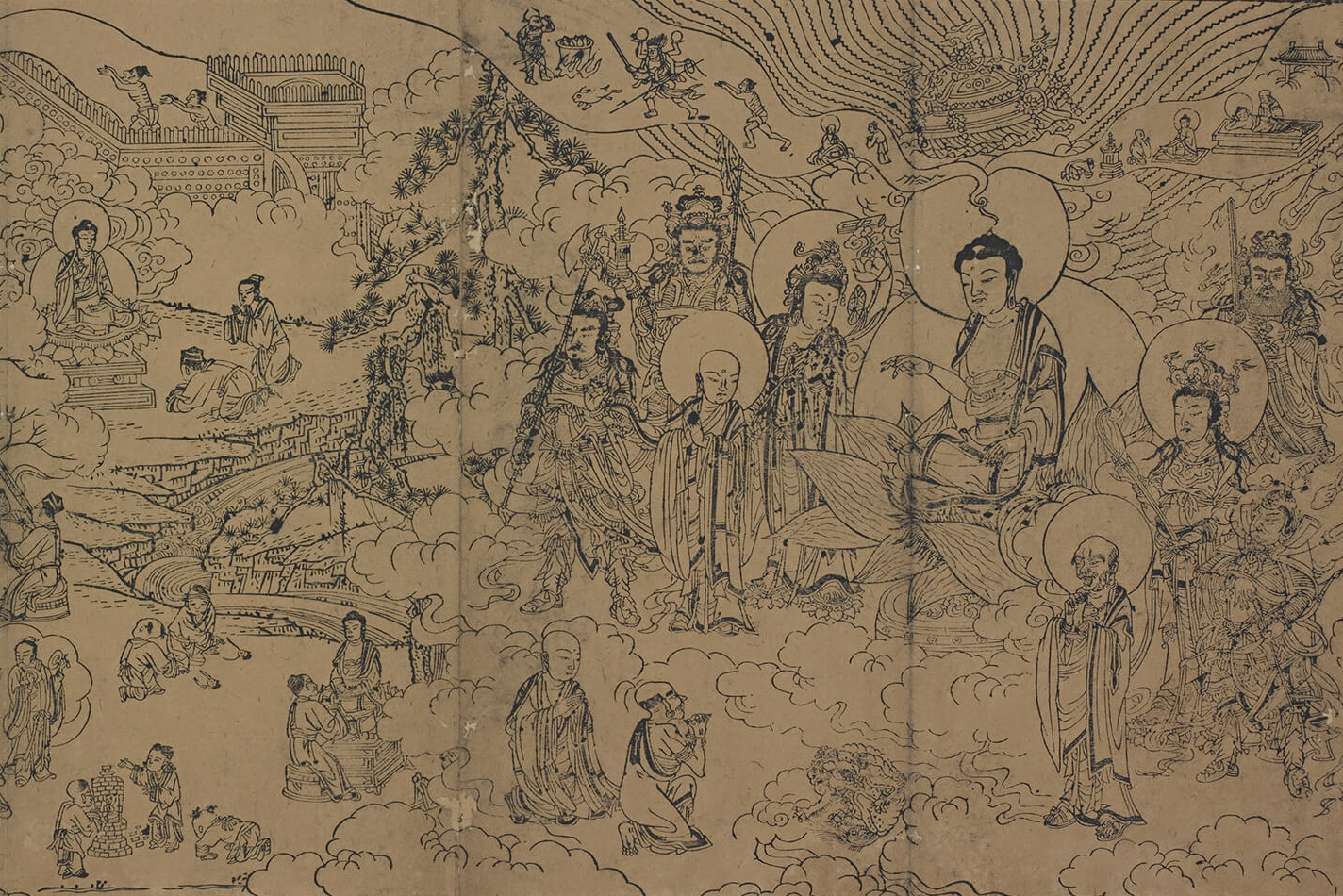

- Copy of a Northern Zhou Painting from Mogao Cave 428 at Dunhuang

- Zhang Daqian, Republican period

- Silk

This work by Zhang Daqian (1899-1983) is a tracing copy of a 6th century Dunhuang mural. The original mural was divided into three registers, which depict the plot sequentially. The scenes are demarcated by mountains and buildings, and the figures and their poses are rendered in a lively manner. Zhang Daqian followed the layout of the original mural and systematically arranged the narration from left to right, as opposed to the typical right-to-left viewing direction of handscrolls.

This section features "The Gift of the White Elephant" from the Jātaka of Crown Prince Siddhartha. Eight Brahmins sent from a rival kingdom sought from the charitable prince his court's treasured white elephant, who had never been defeated in battle. Because Prince Siddhartha agrees to their request and allows them to ride away with the elephant, he is ultimately exiled.

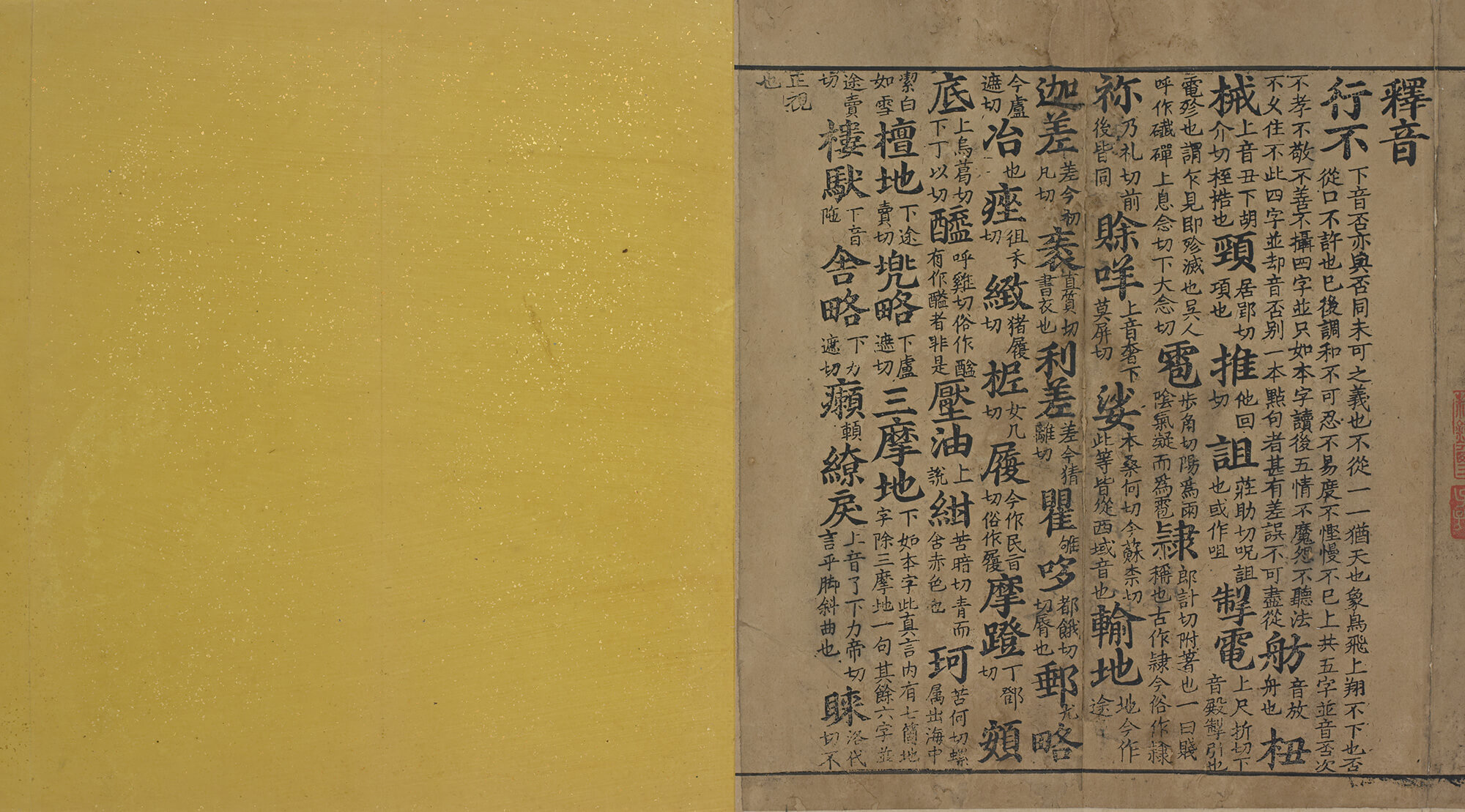

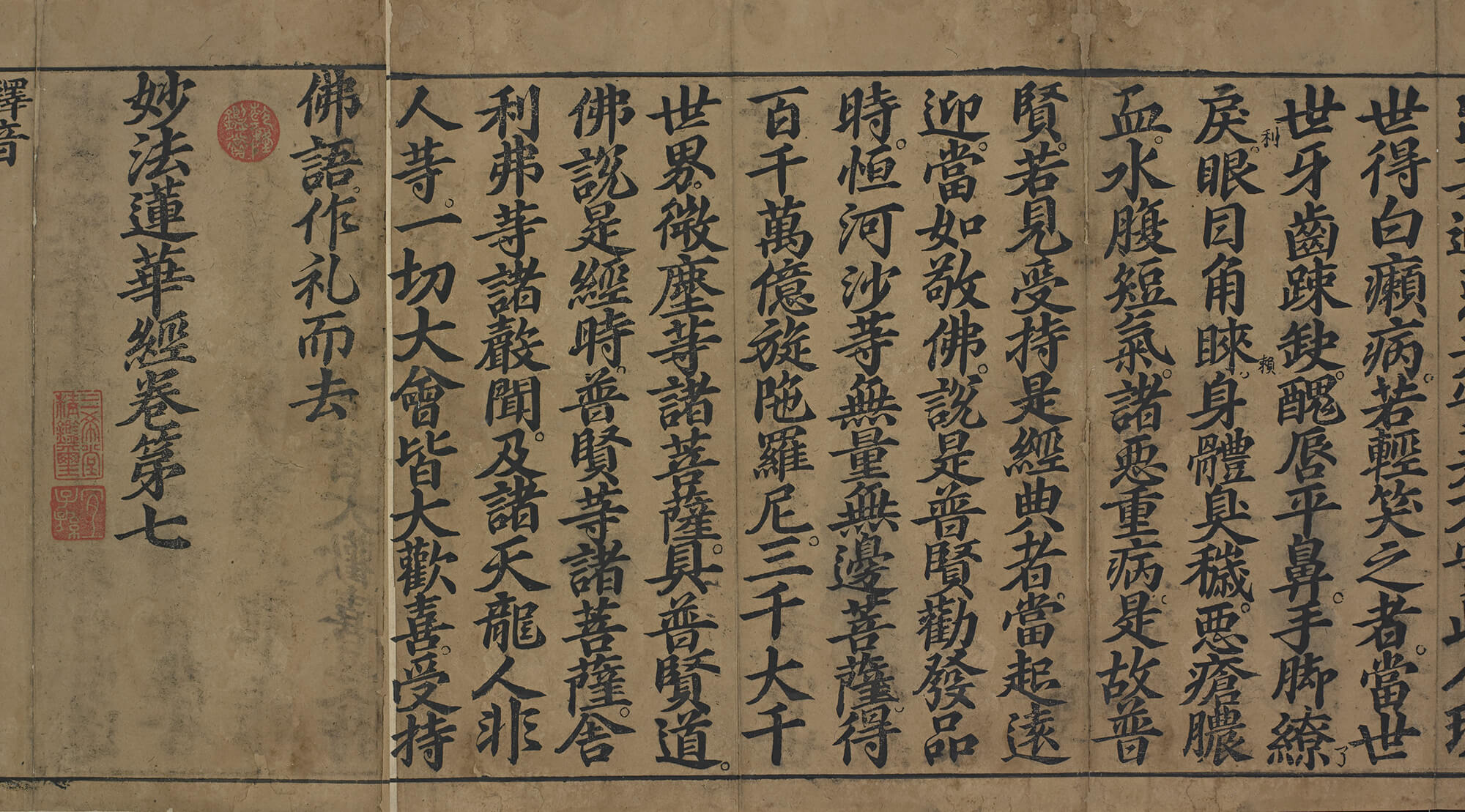

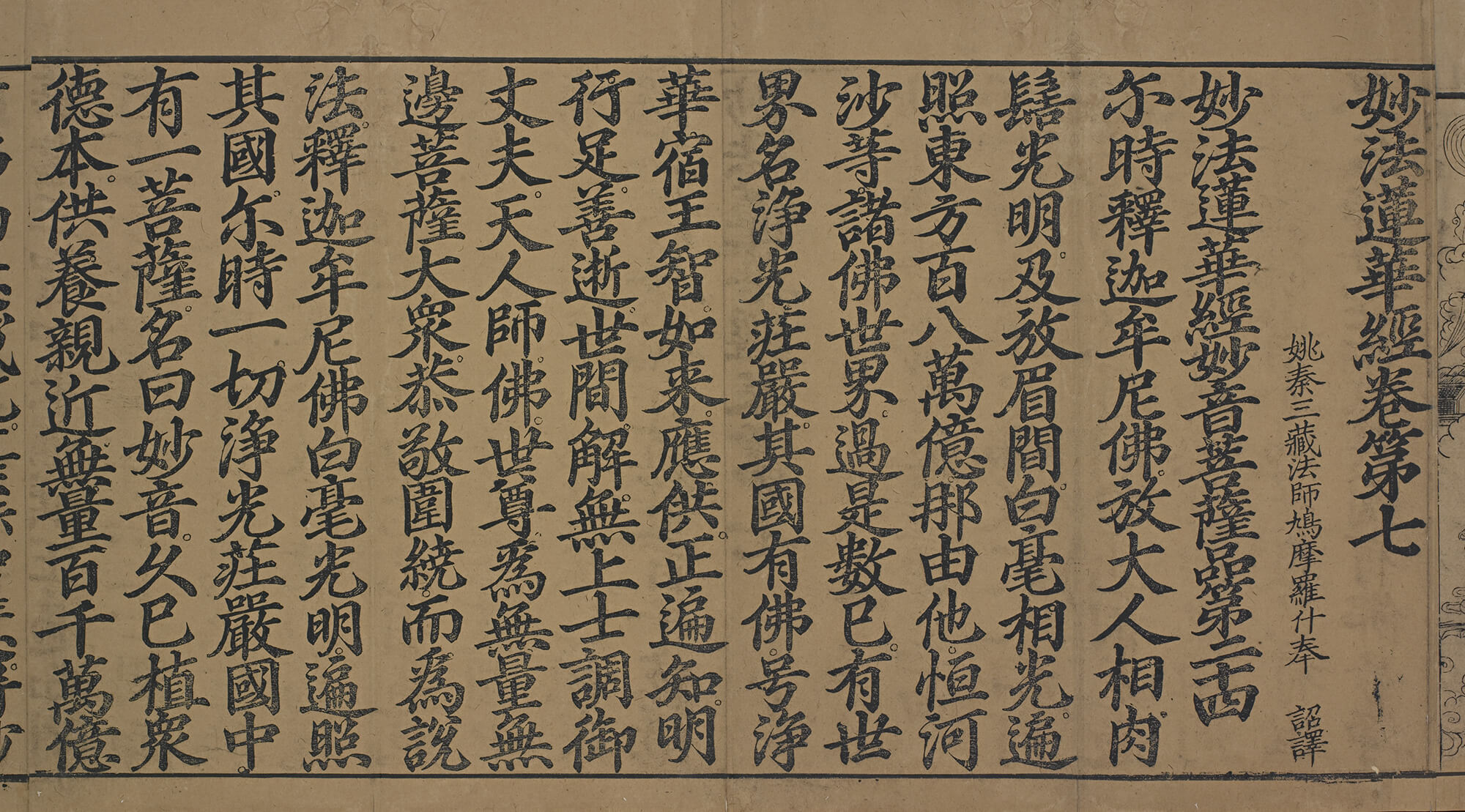

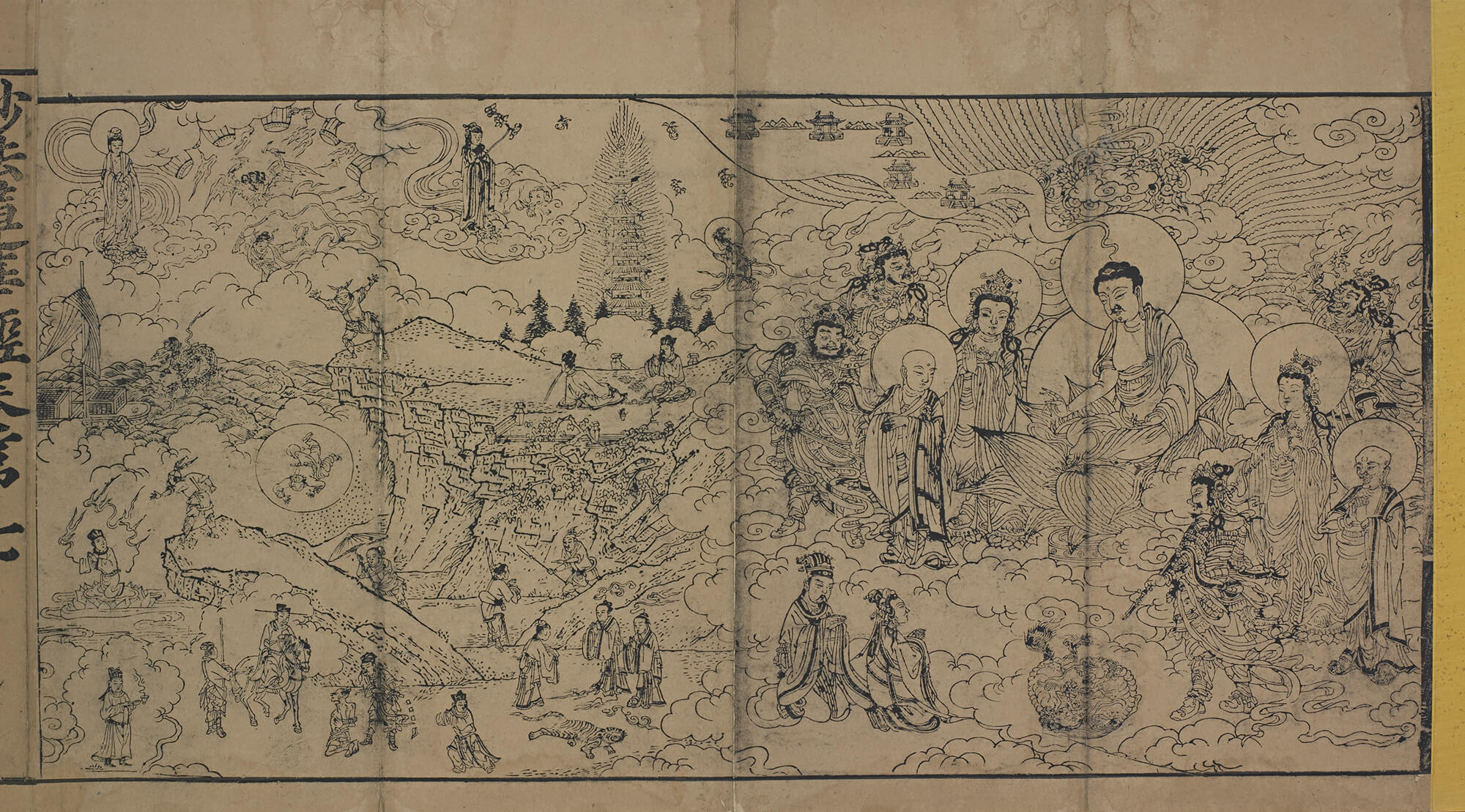

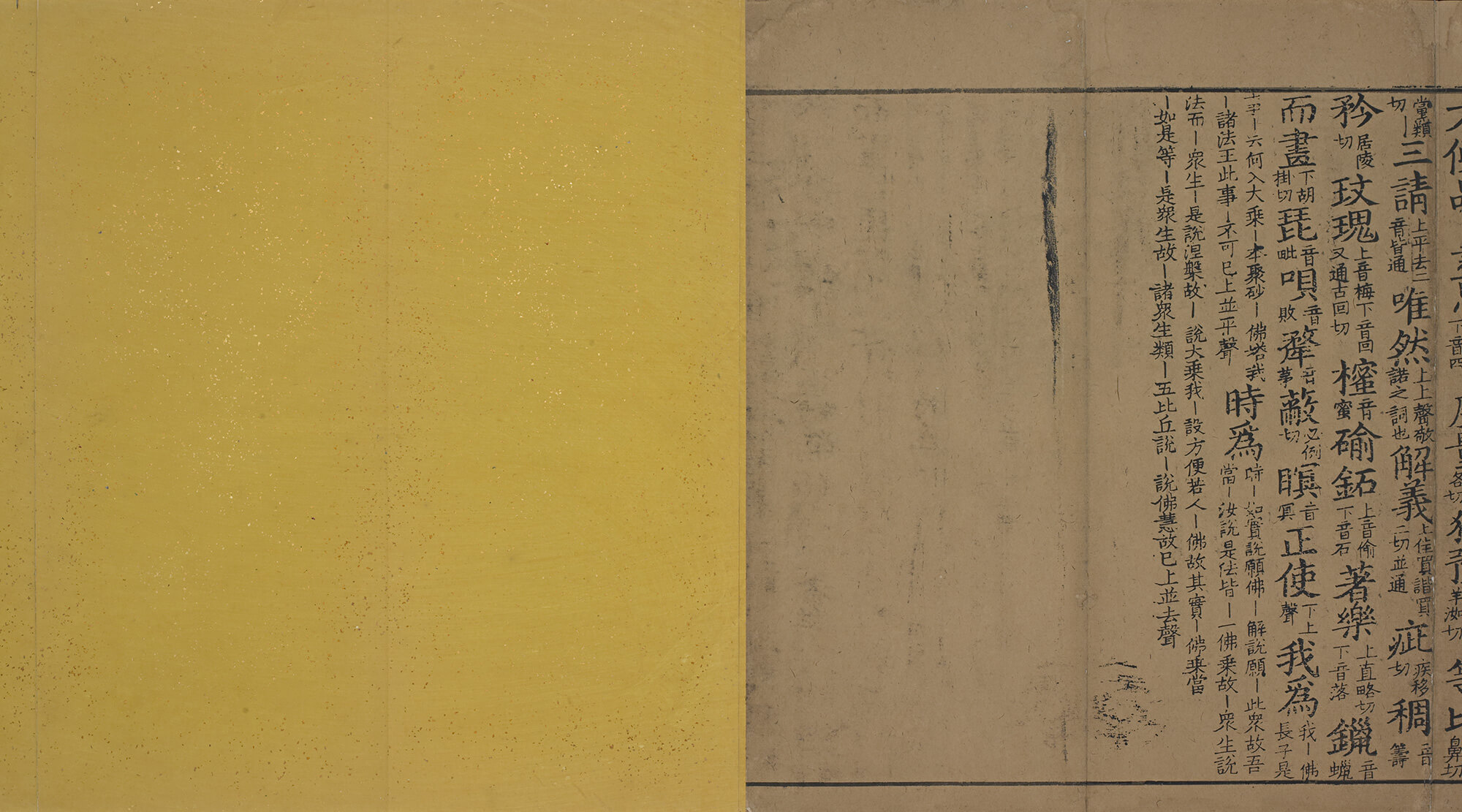

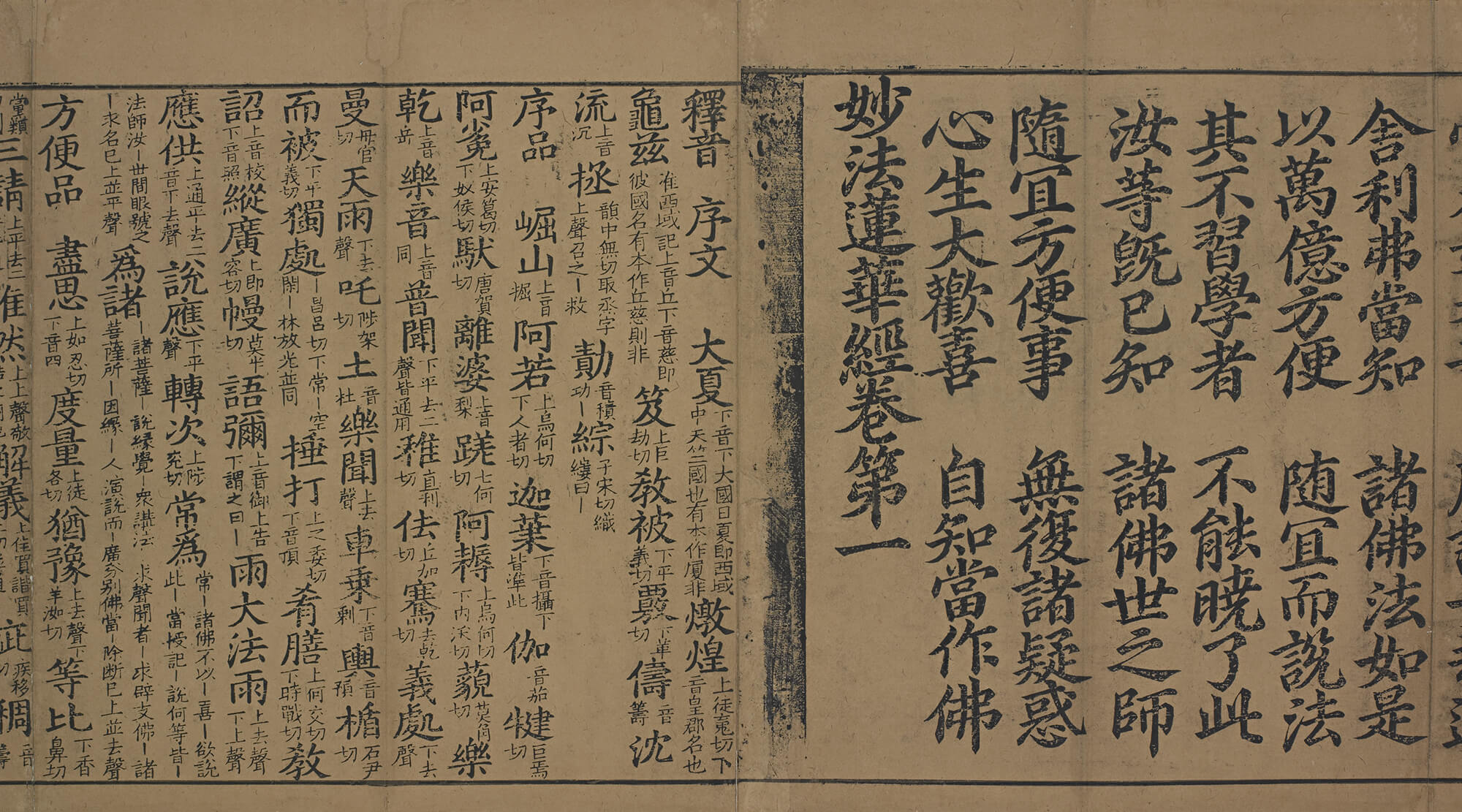

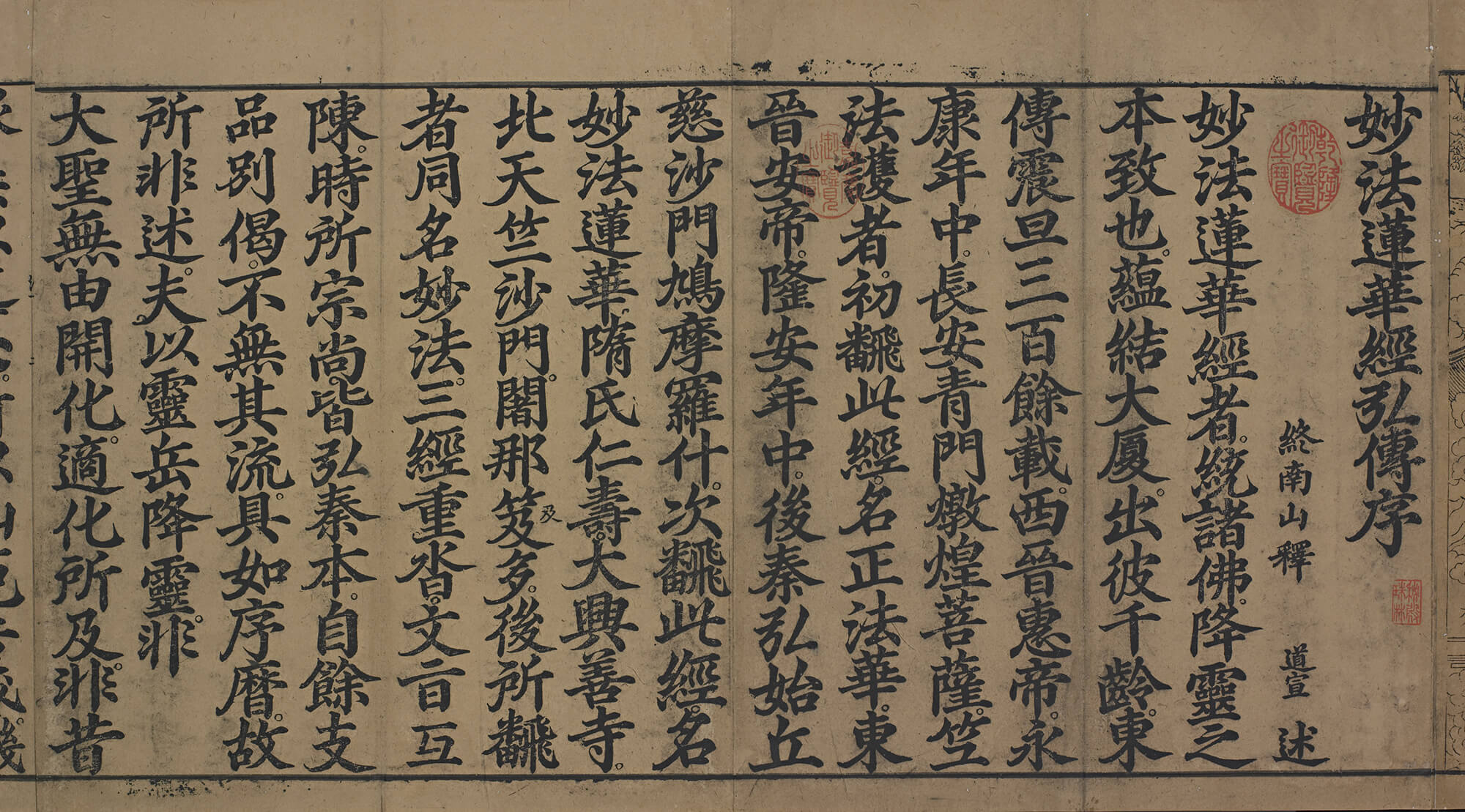

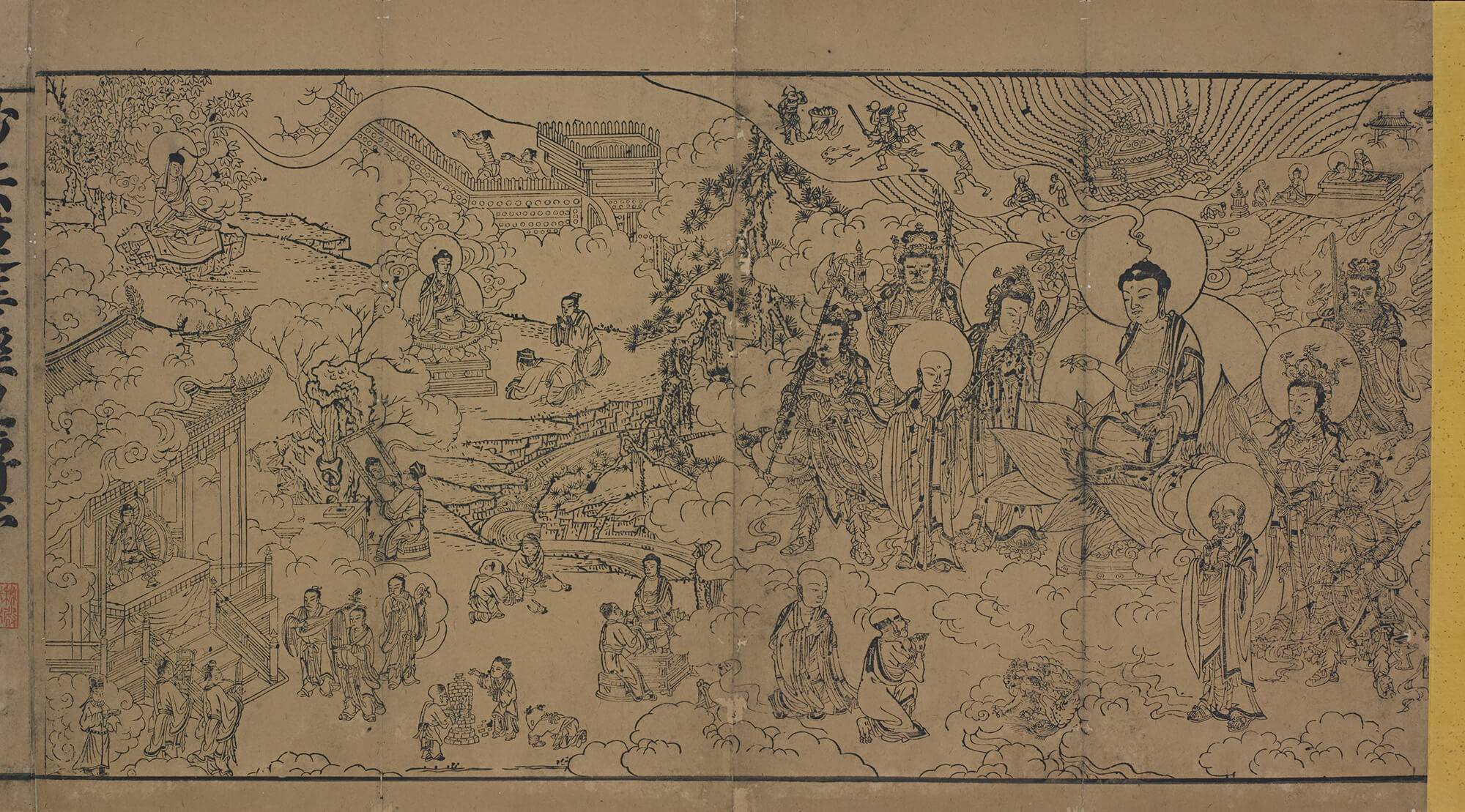

- Miaofa Lianhua Jing

Lotus Sutra- Translated by Kumārajīva, Later Qin dynasty

- Imprint of a manuscript written in the calligraphic style of Su Shi, Yuan dynasty

- Paper

The two woodblock prints seen here are frontispiece illustrations for Volumes 1 and 7 of the Lotus Sutra. On the right side, Shakyamuni and his entourage of Bodhisattvas are depicted larger in scale, a traditional painting convention used to make important figures stand out. Unlike early Dunhuang murals, which often framed different stories or scenes with mountains, the frontispiece artist places the stories within the same landscape setting. The artist uses the terrain and the topography to allow the characters to enact each of their stories. These frontispieces effectively portray both Shakyamuni preaching the Lotus Sutra and its content, presenting a harmonious and cohesive tableau.

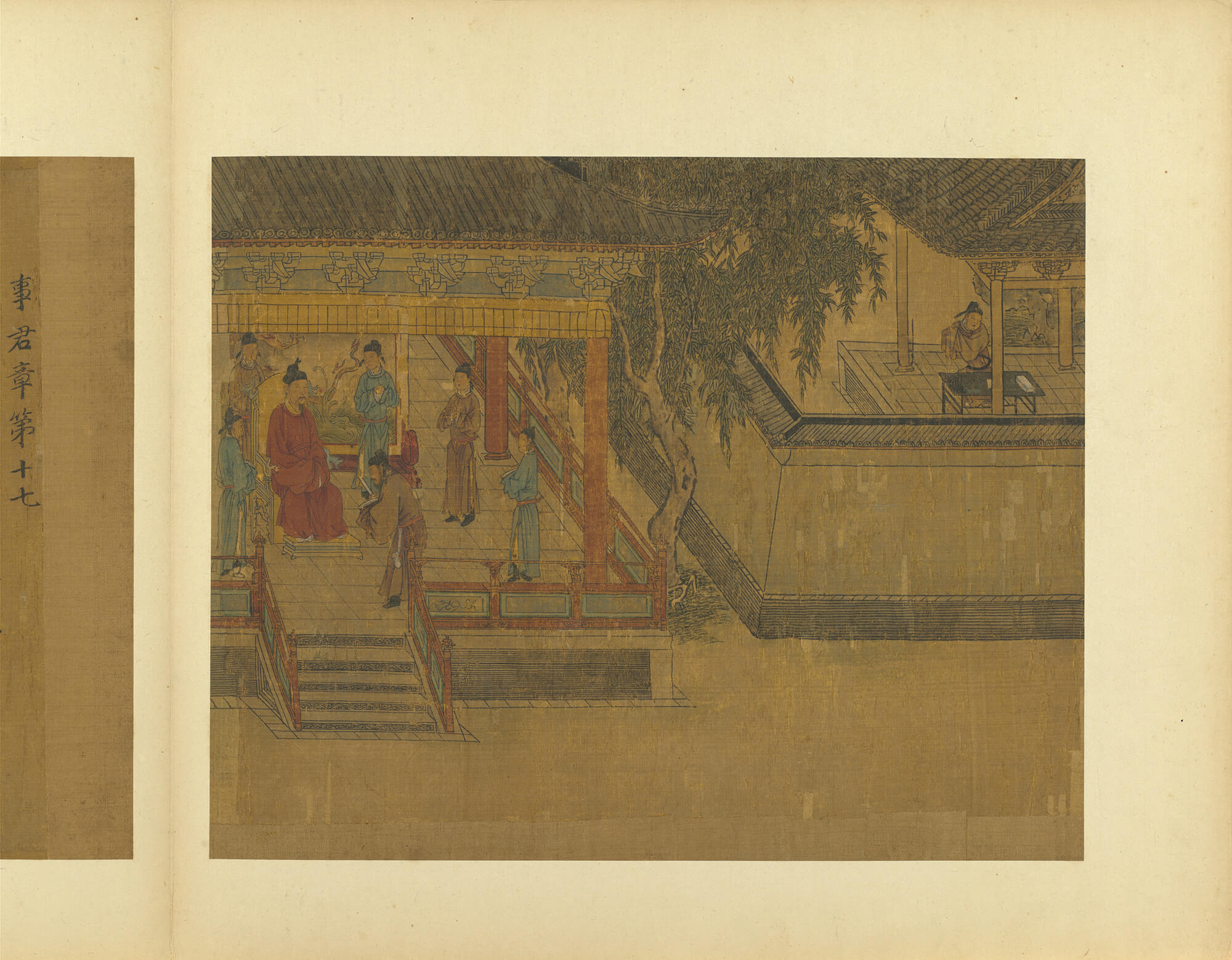

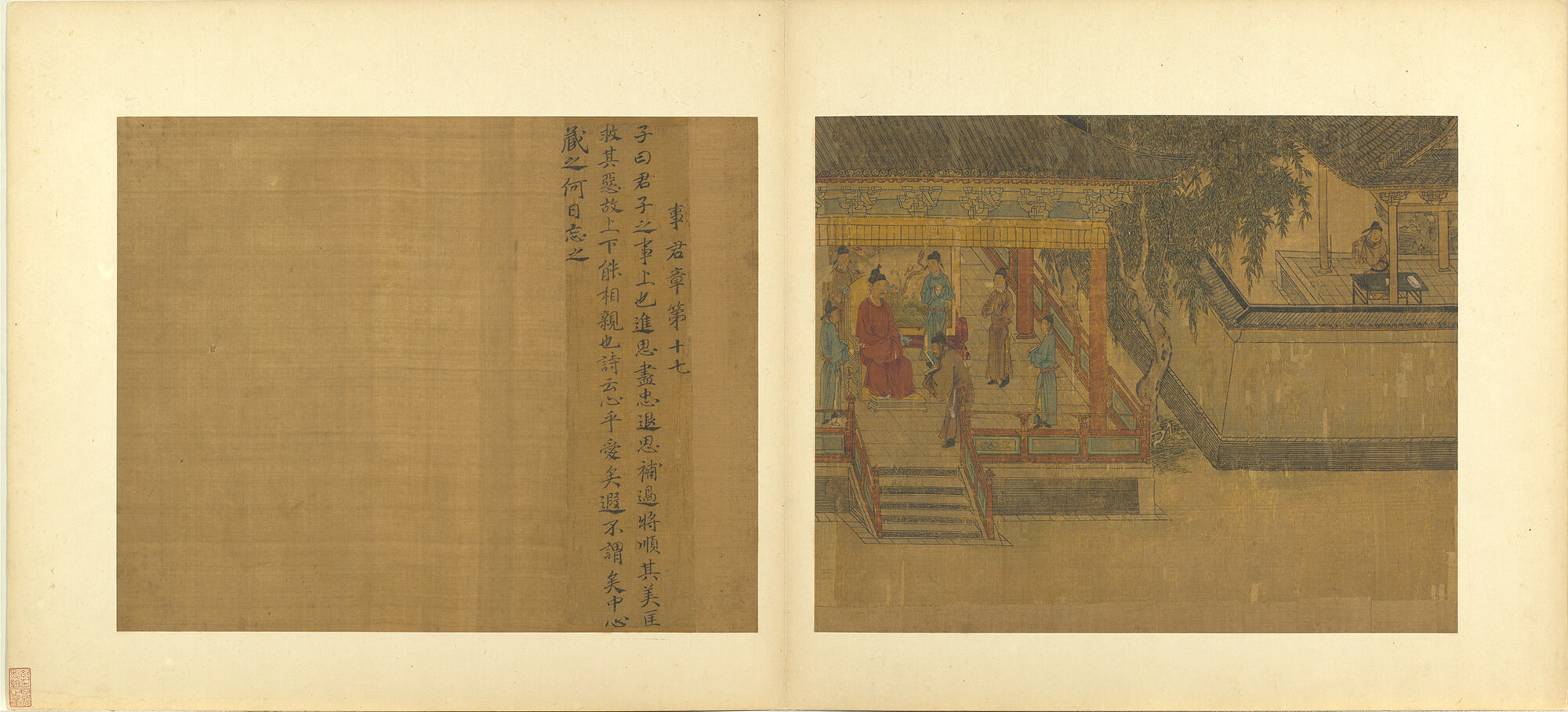

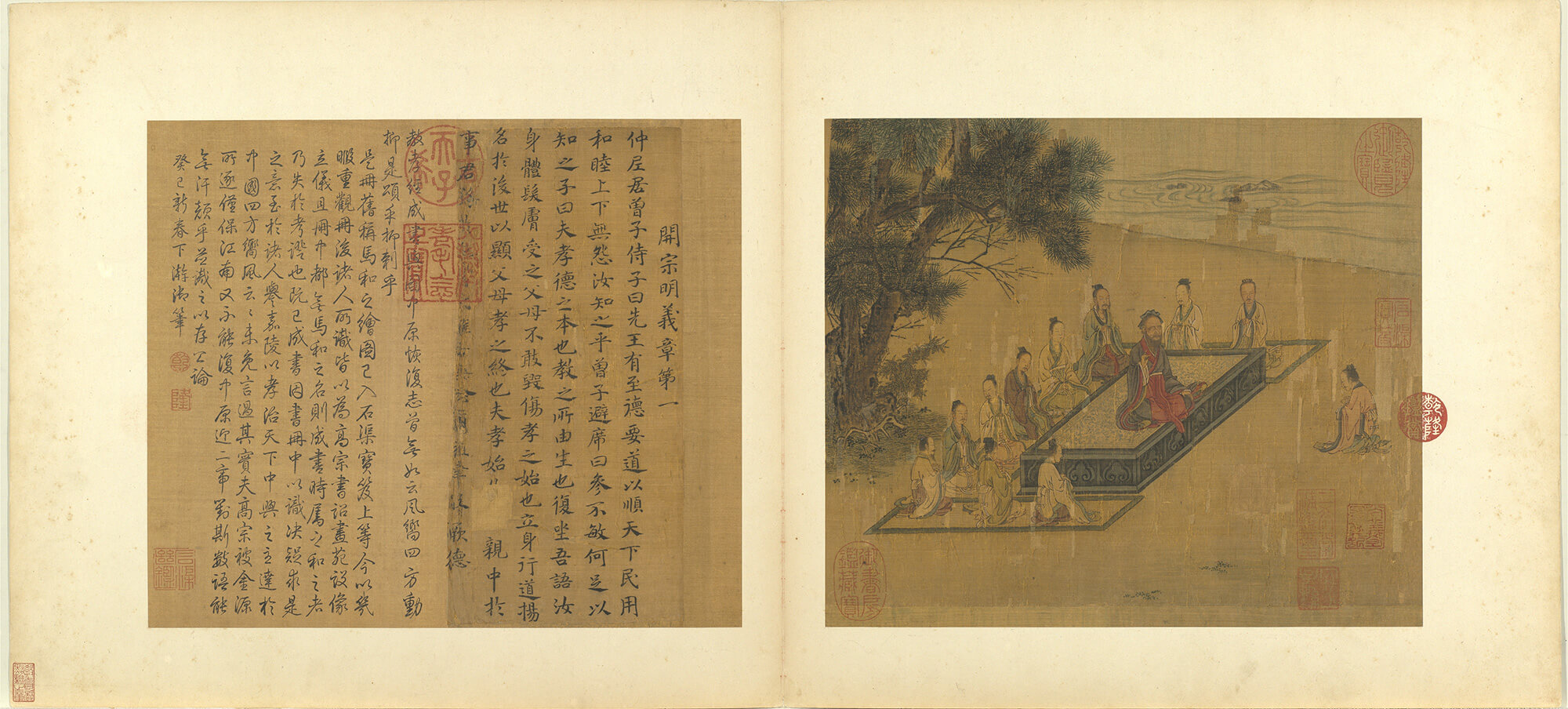

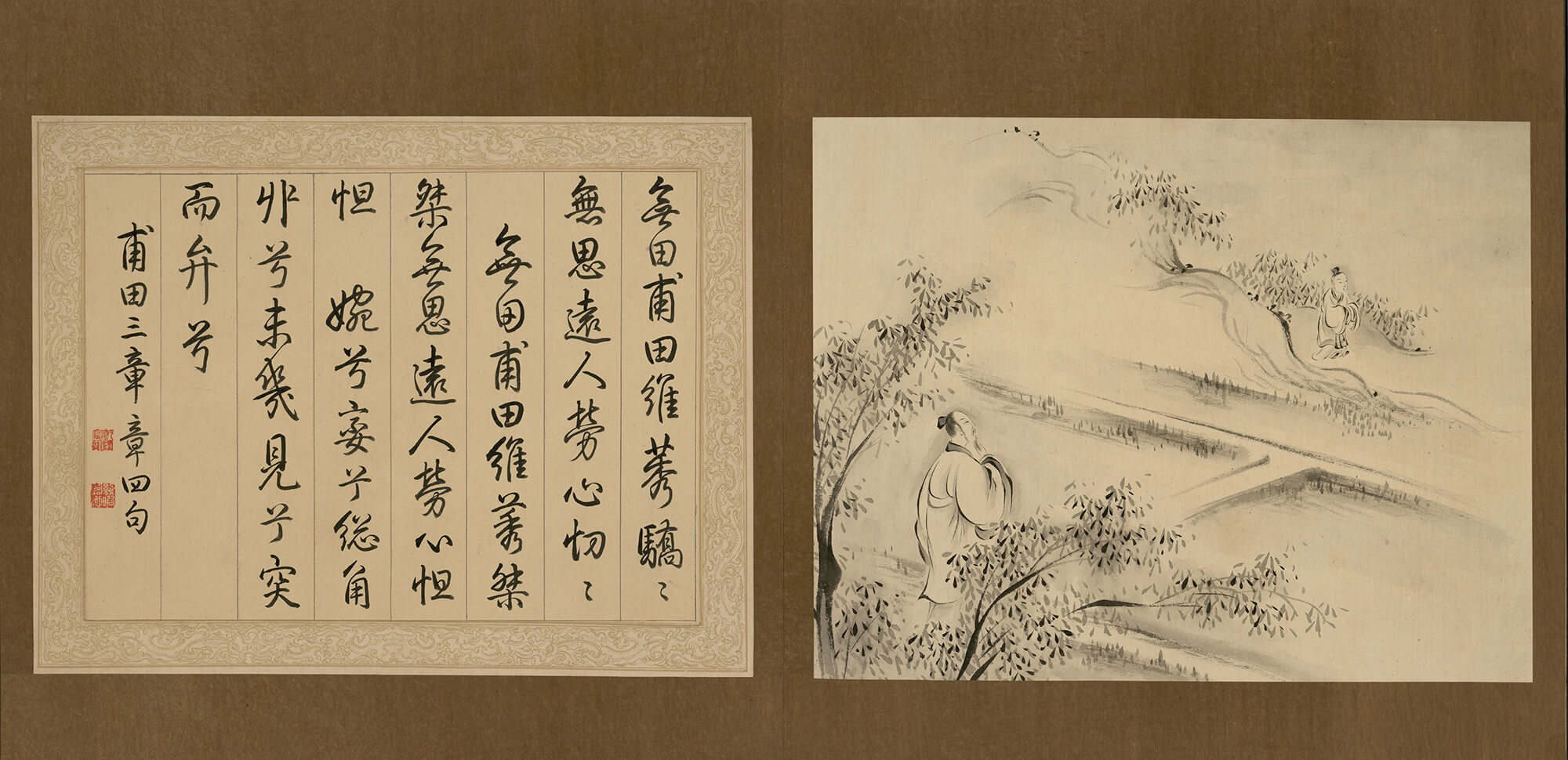

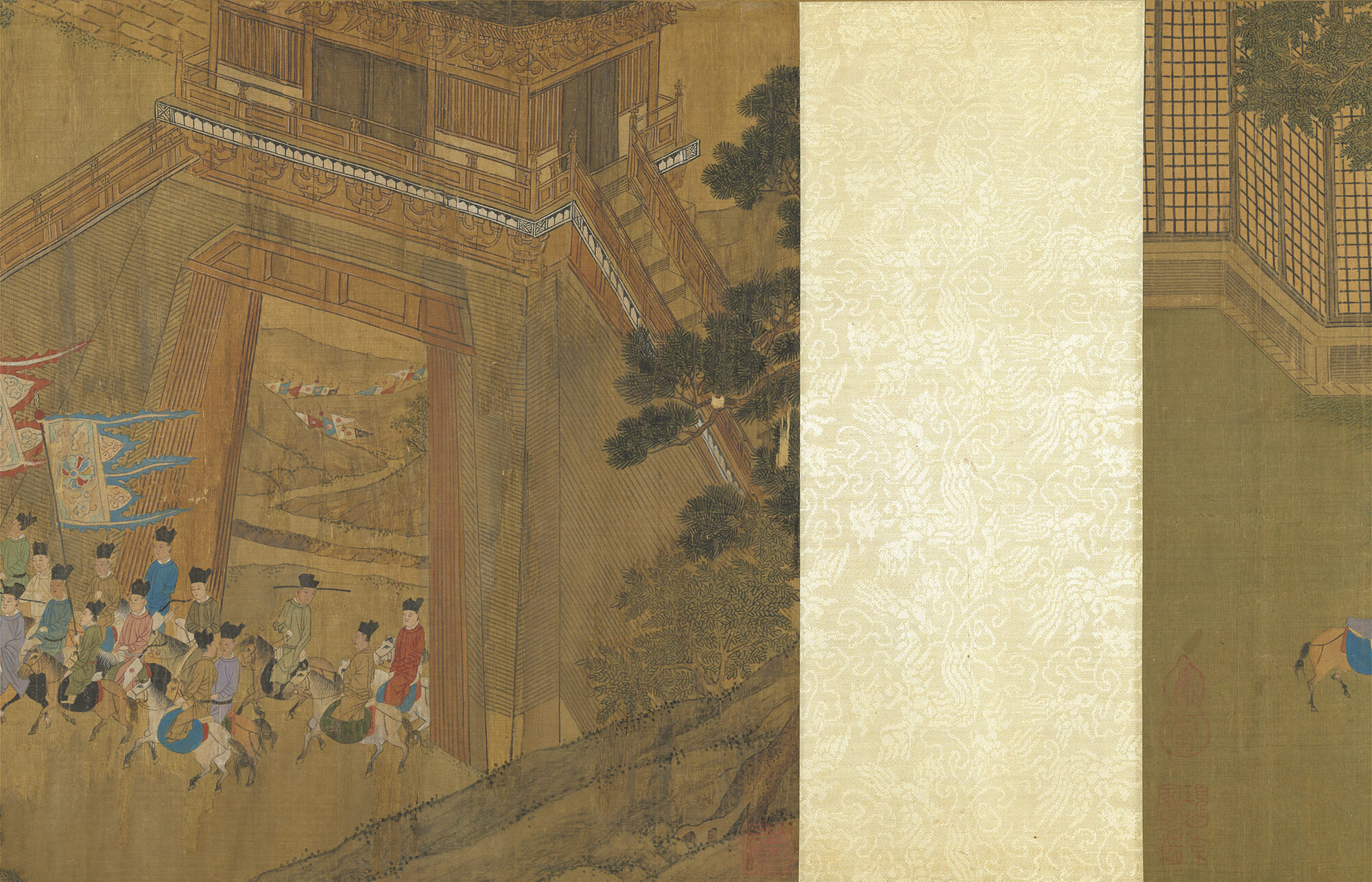

- Classic of Filial Piety

- Calligraphy attributed to Gaozong and illustration attributed to Ma Hezhi, Song dynasty

- Silk

The Classic of Filial Piety is a written account of Confucius commentating on the principle of filial piety. In the first album leaf, Confucius is seated sideways on a couch and is surrounded by his disciples. With Zengzi kneeling before his teacher, the image resembles a preaching scene in a Buddhist and Daoist frontispiece that has been reversed and simplified into a Confucian version.

The fifteenth album leaf titled "Serving the Ruler" shows the emperor in the halls of his palace, separated from an official's garden by a single willow tree. While such closeness would be impossible in reality, the palace and the garden occupy nearly the same amount of spce in the painting. This choice likely reflects the artist's pictorial interpretation of the text's couplet: "When advancing, think of utmost loyalty; when retreating, of making amends for mistakes."

This album does not resemble the style of the Southern Song academy painter Ma Hezhi (fl. mid-12th century) and is likely misattributed to him by later artists of the Song dynasty.

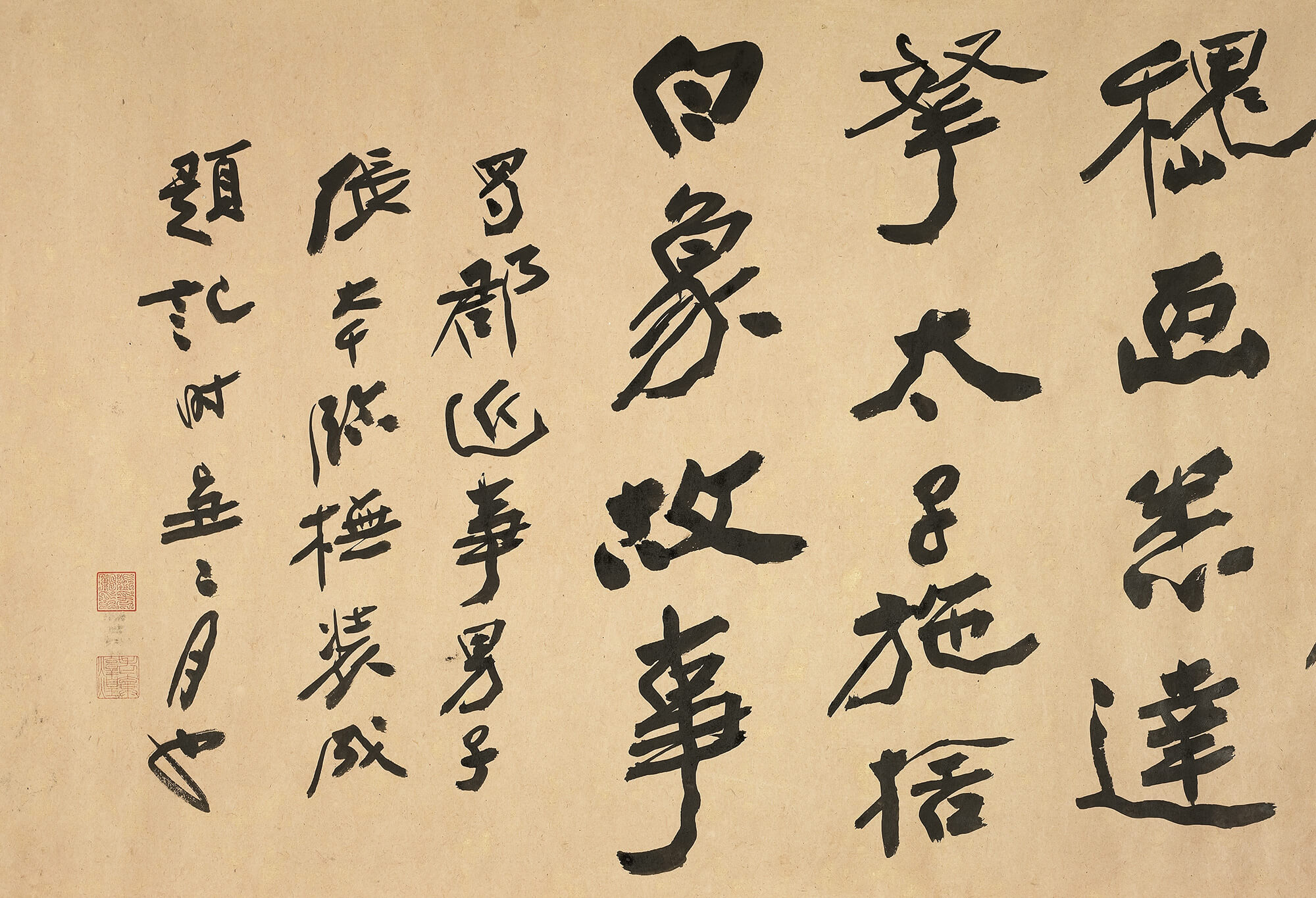

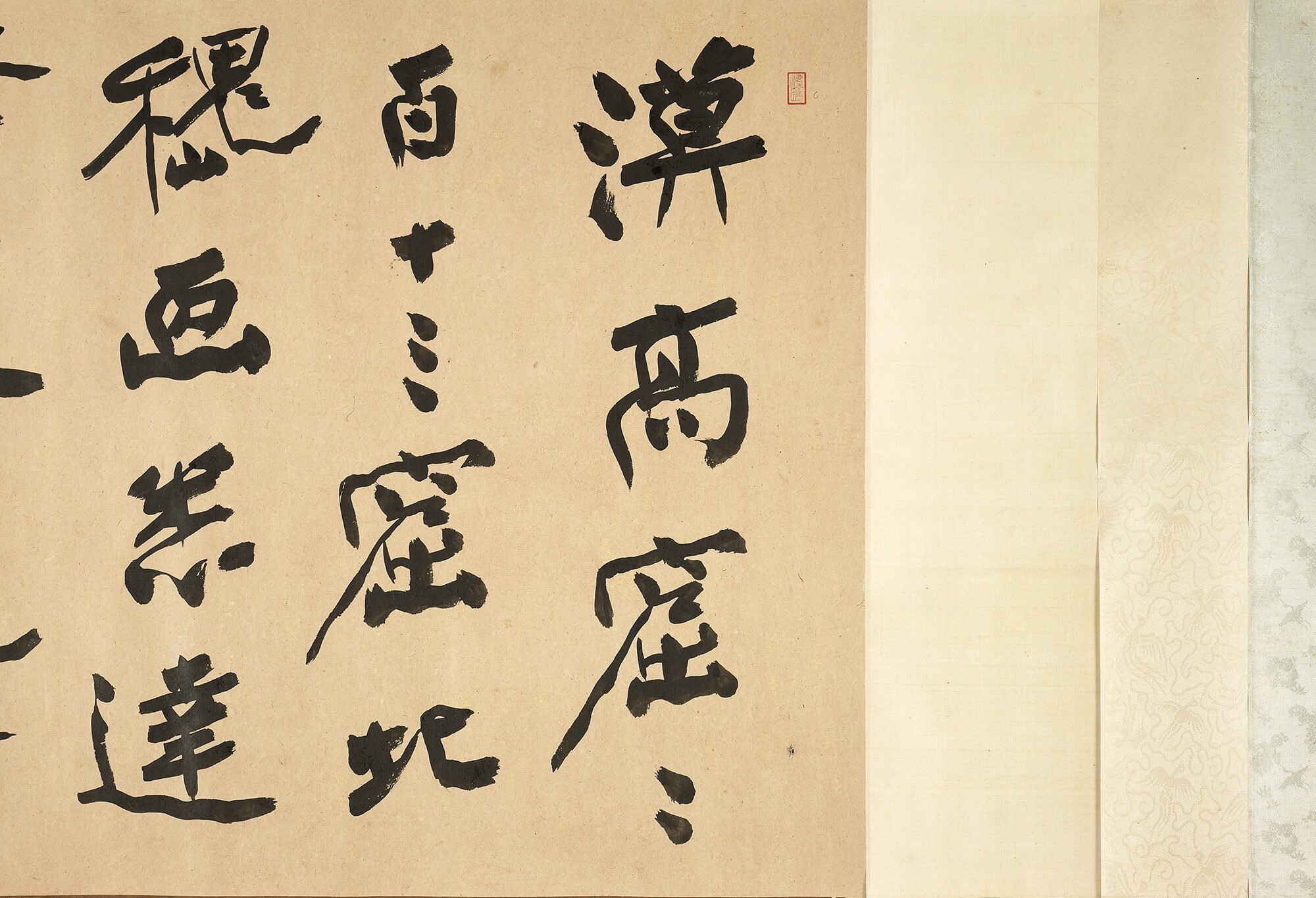

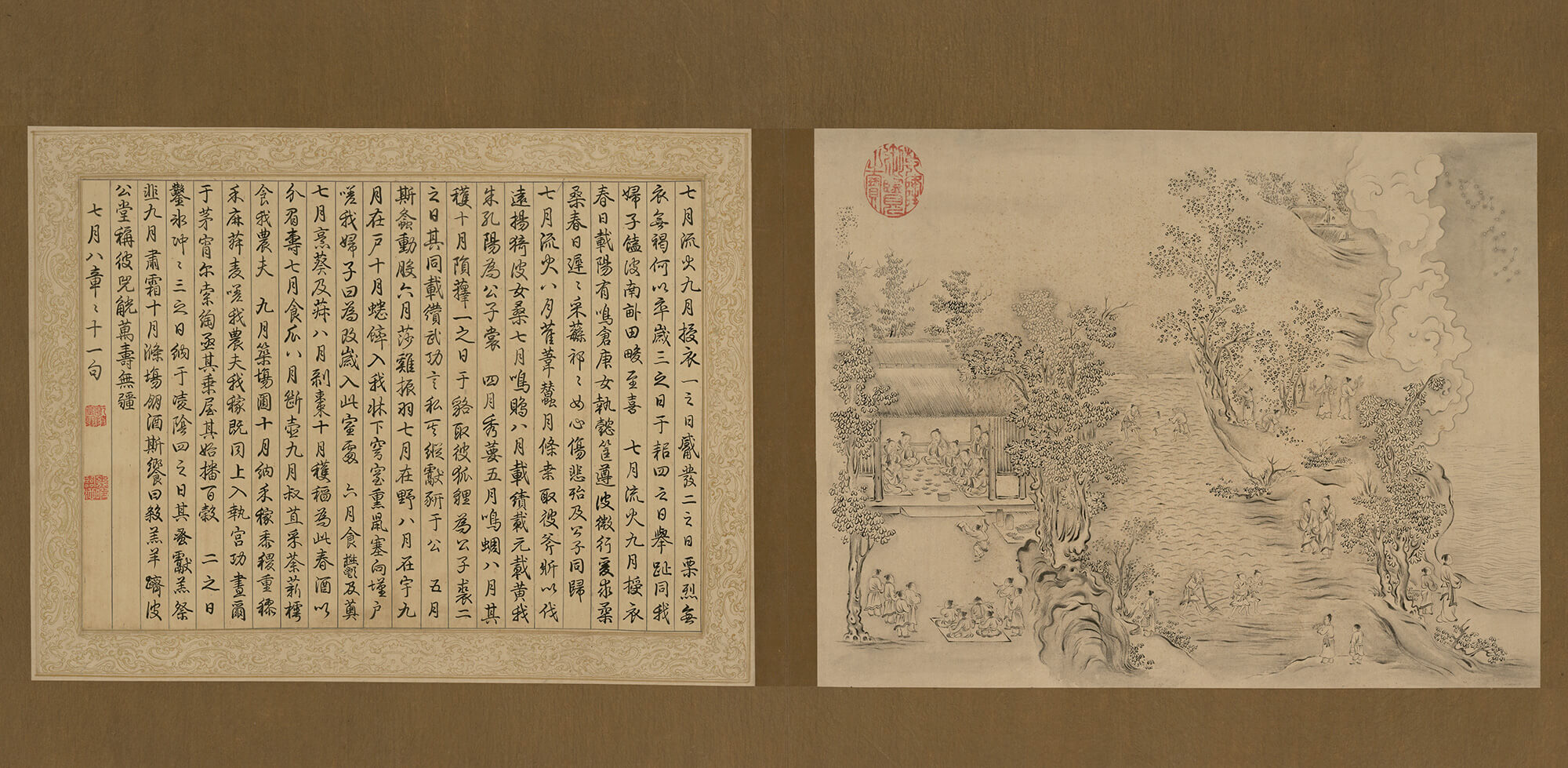

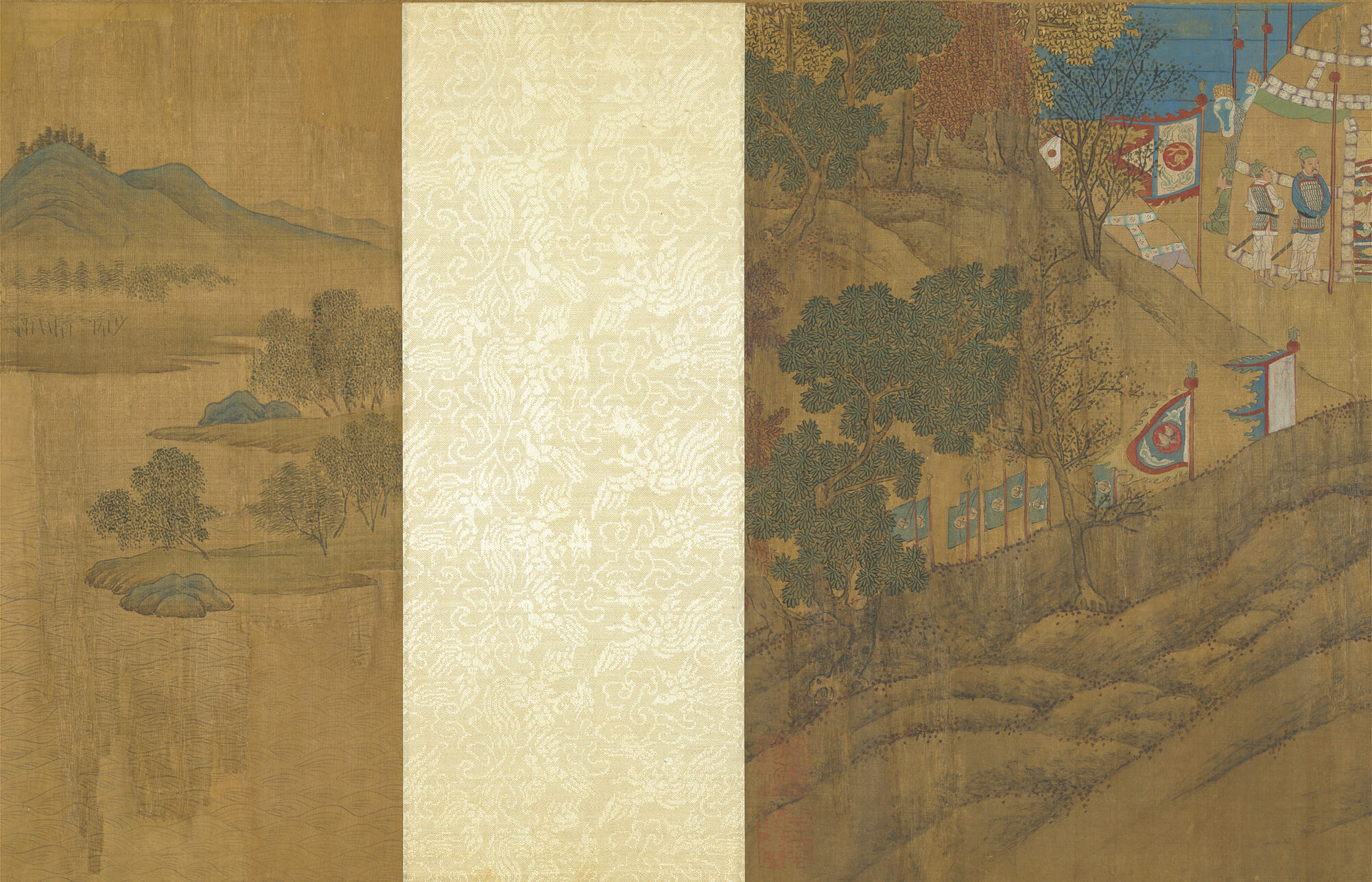

- Illustrations of the Book of Odes ("Airs of Qi: Great Fields" and "Airs of Bin: Seventh Month")

- Inscribed by Emperor Qianlong, Qing dynasty

- Paper

The Book of Odes is the earliest anthology of Chinese poetry, including 305 poems from the Western Zhou to the mid-Spring and Autumn period (c. 11th to 6th centuries BCE). Much of the content subtly expresses concealed opinions or emotions through metaphor. The Southern Song civil official Ma Hezhi (fl. 12th century) was a highly skilled painter, and the illustrations he paired with the Book of Odes became classics in their own right. The Qing dynasty Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) ordered court painters to produce tracing copies of Ma Hezhi's Illustrations of the Book of Odes from the imperial collection and to restore damaged and missing sections. Two of these reproductions from the Qianlong court are on display here.

The poem "Great Fields" conveys a sort of grievance in its verses, yet it is filled with longing and the anticipation of meeting again. How might the sense of longing from the poem be visualized? The sloping hillside alludes to the vast distances of ten thousand mountains and rivers, echoing the sentiments of the scholar at the field's edge as he yearns for the distant figure of a friend. The painting uses narrative painting techniques to skillfully convey the lyricism of the poetry.

The lengthy poem "Seventh Month" relates the main agricultural tasks farmers undertake throughout the year. From right to left, the three sections of the image depict the study of the constellations at night, farming and sericulture, and a year-end banquet. The artist avoids repeating the text and instead adds a music and dance scene in the lower left, expressing hope in the civilizing force of rites and music.

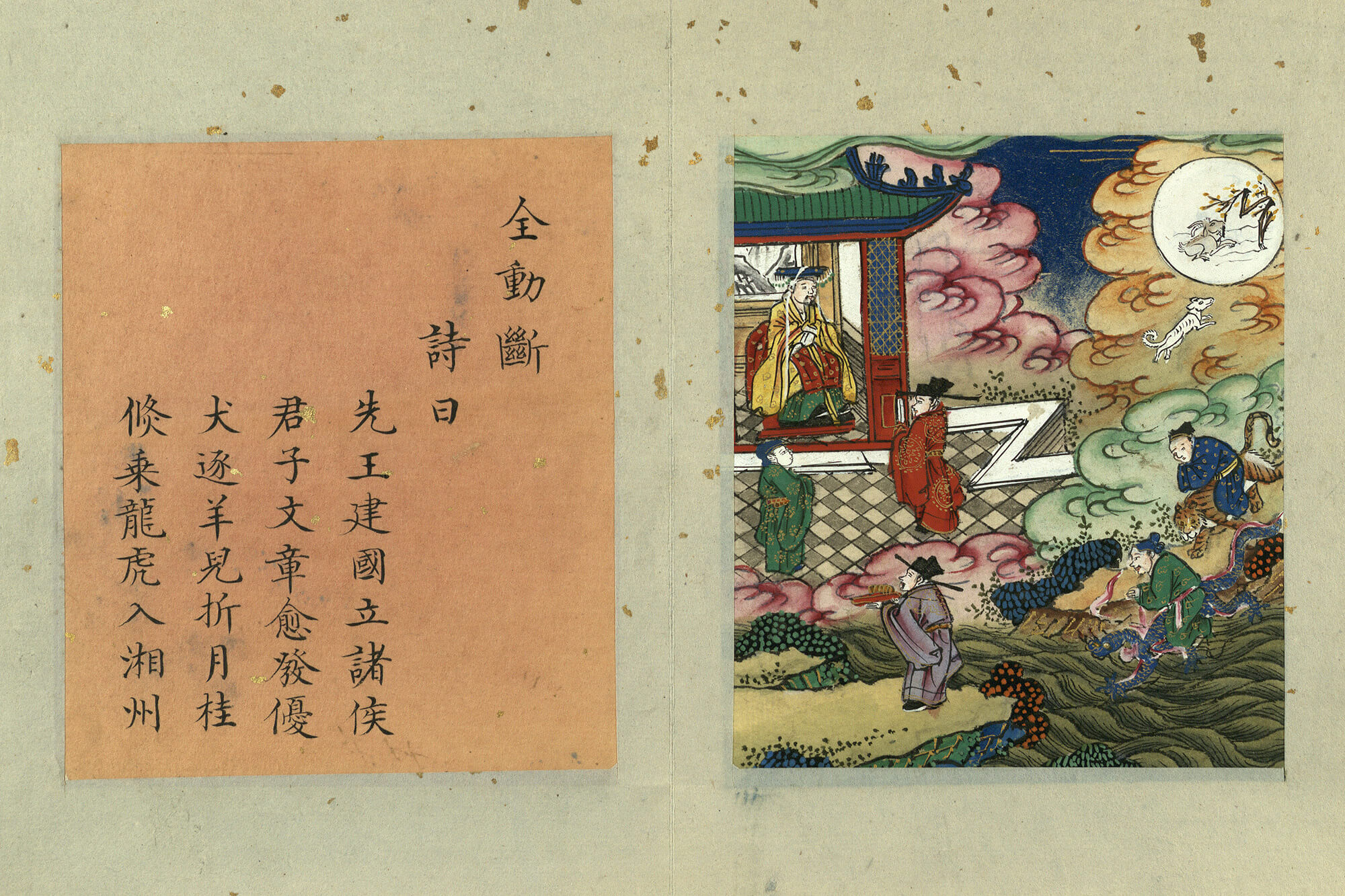

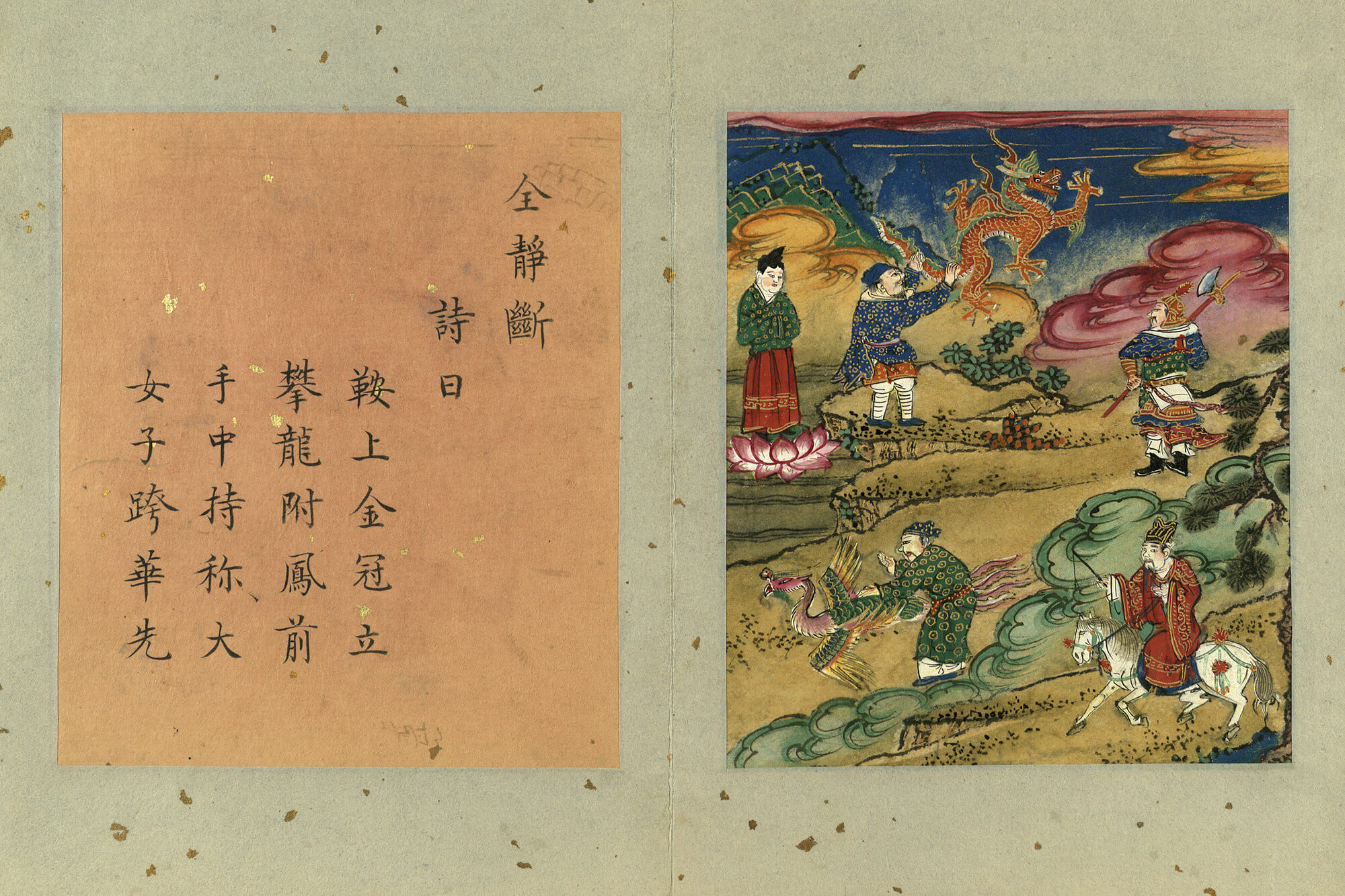

- Imperial Collection of Selected Works in Deciphering the ‘Book of Changes'

- Compiled by Zhu Jianru in 1482, Ming dynasty

The Imperial Collection of Selected Works in Deciphering the ‘Book of Changes' was compiled in 1482 during the Chenghua period, of which 55 volumes have survived. It includes over a thousand divination poems along with illustrations.

Many of the images in the book are literal translations of the poems, such as when figures are shown holding onto a dragon's tail or stroking a phoenix to depict the idiom "hitching a ride to the sky on the dragon and the phoenix." There are also examples of indirect translation, such as when the line "meeting again at the place of Yin and Mao" is shown as a tiger and a rabbit walking side by side. Here, the artist transforms the earthly branches "Yin" and "Mao" into animal zodiac signs.

Though the poetry is often obscure, the artist takes it and create images brimming over with dramatic tension, like a captivating, fantastical tale.

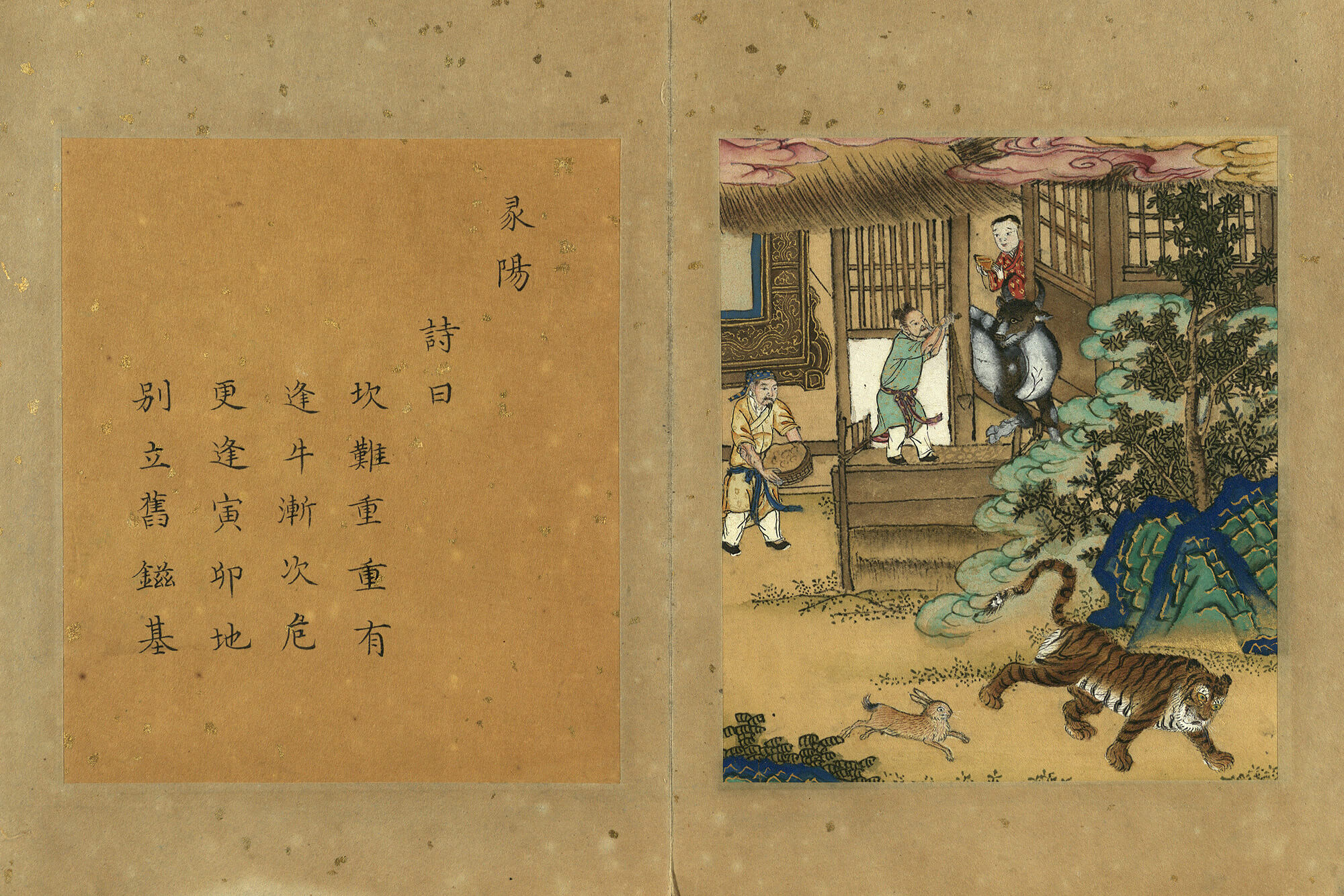

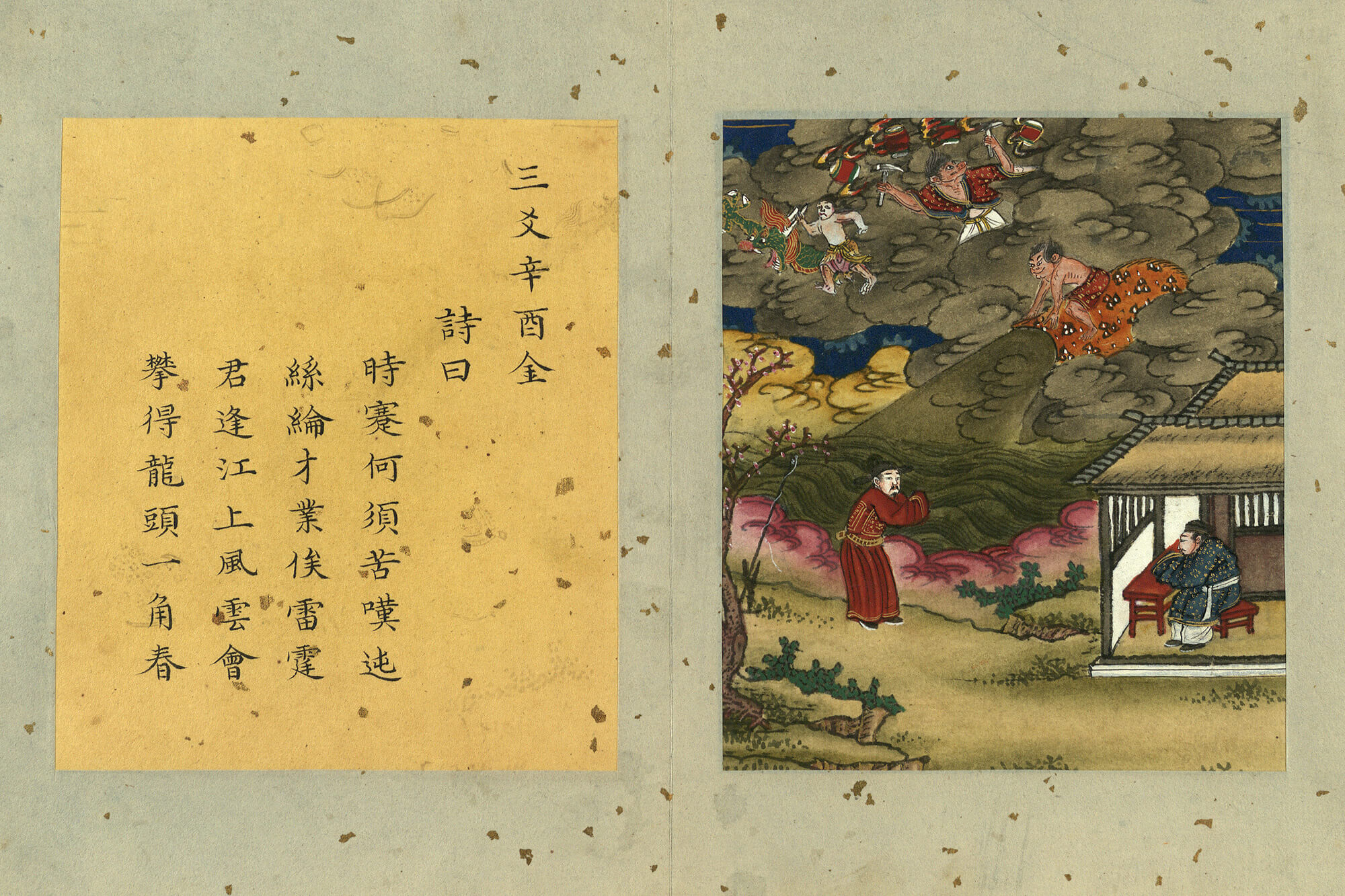

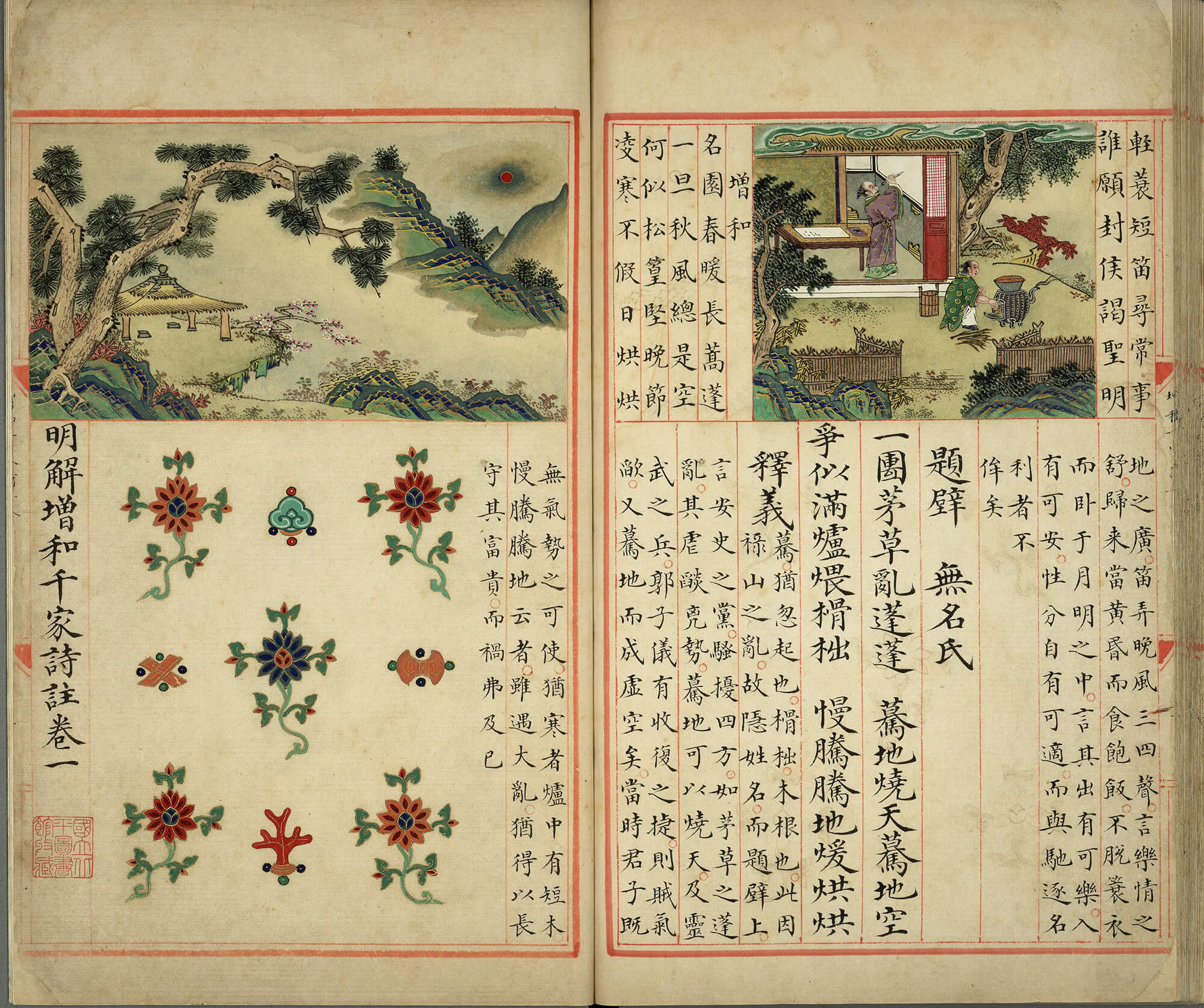

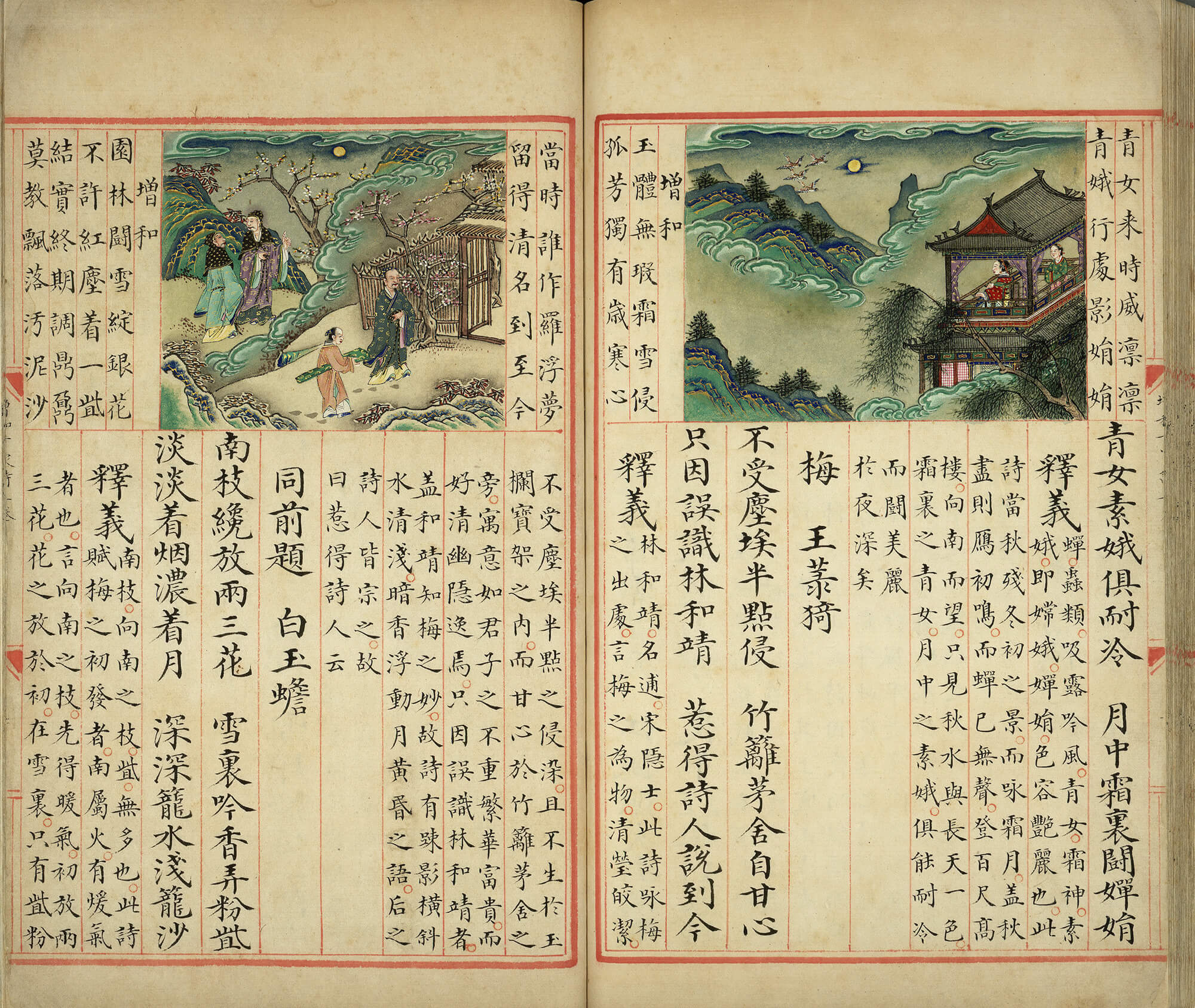

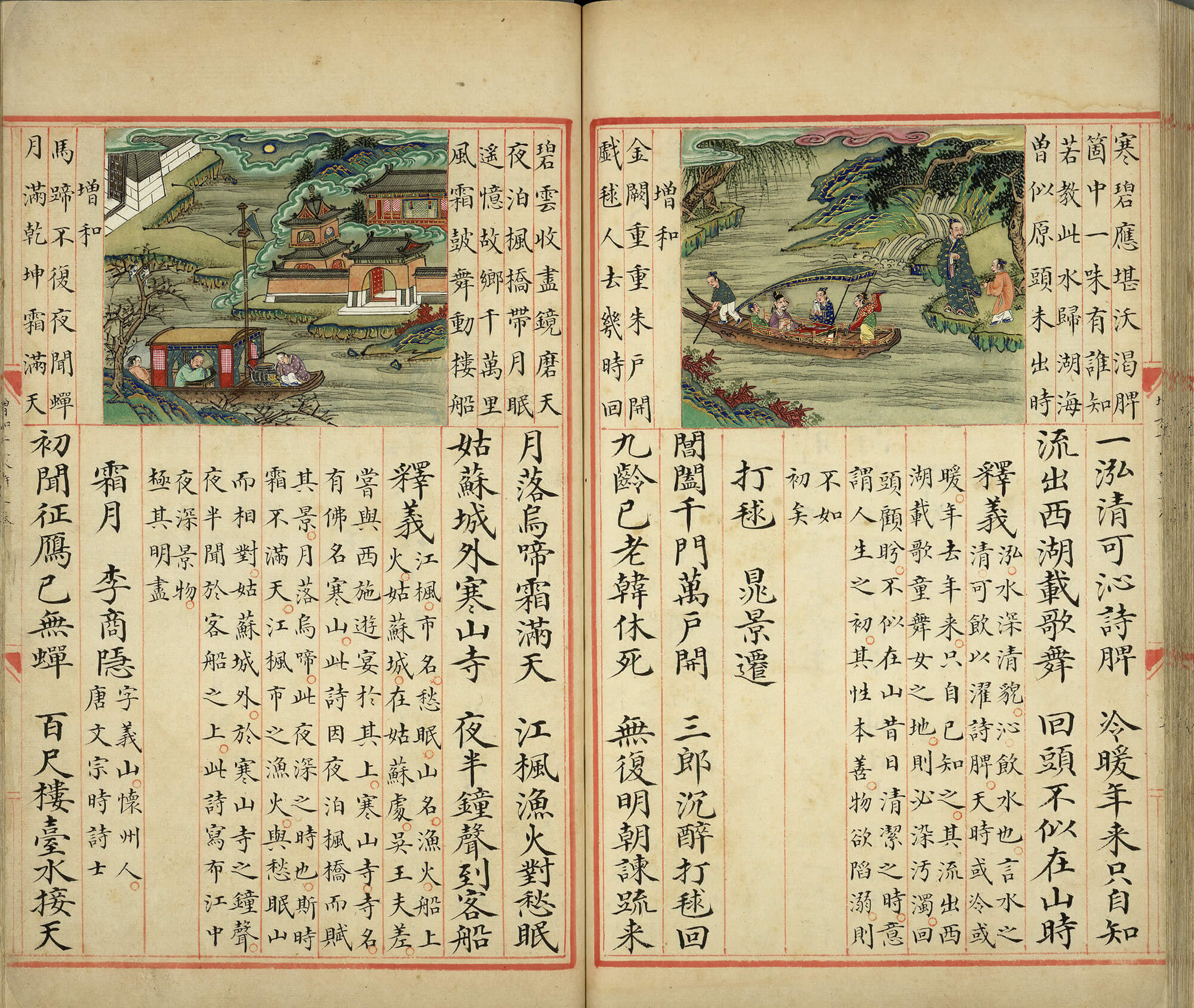

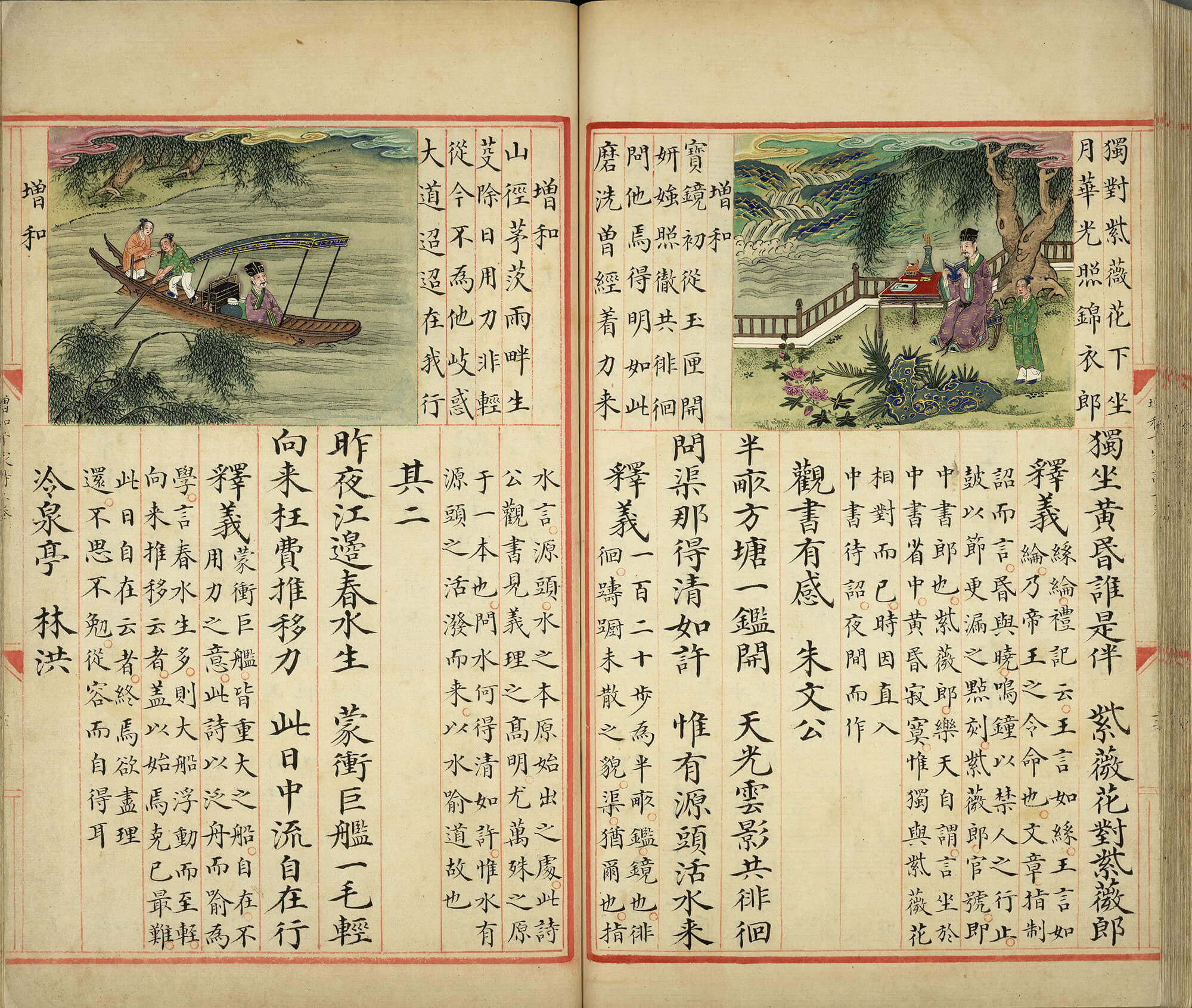

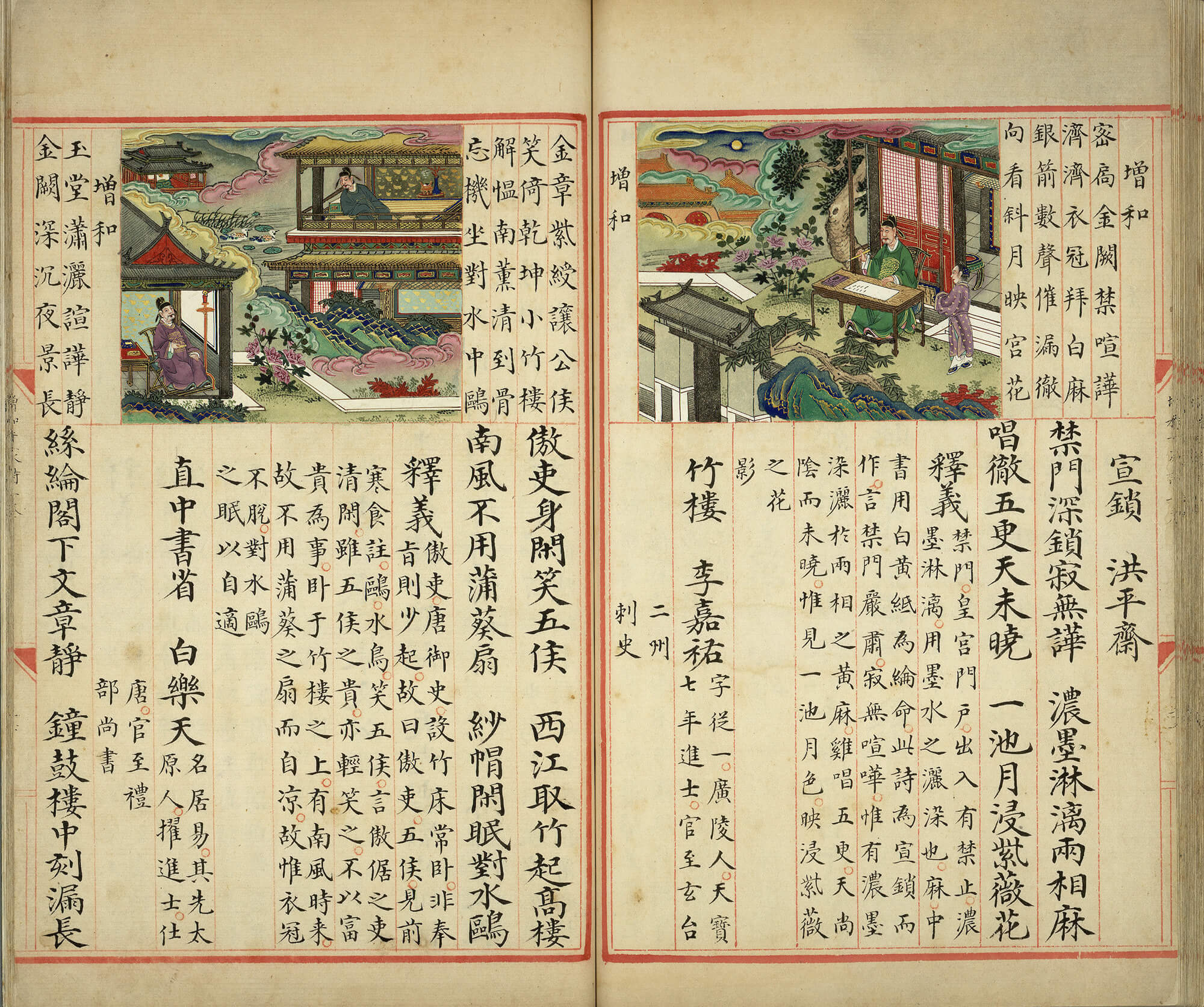

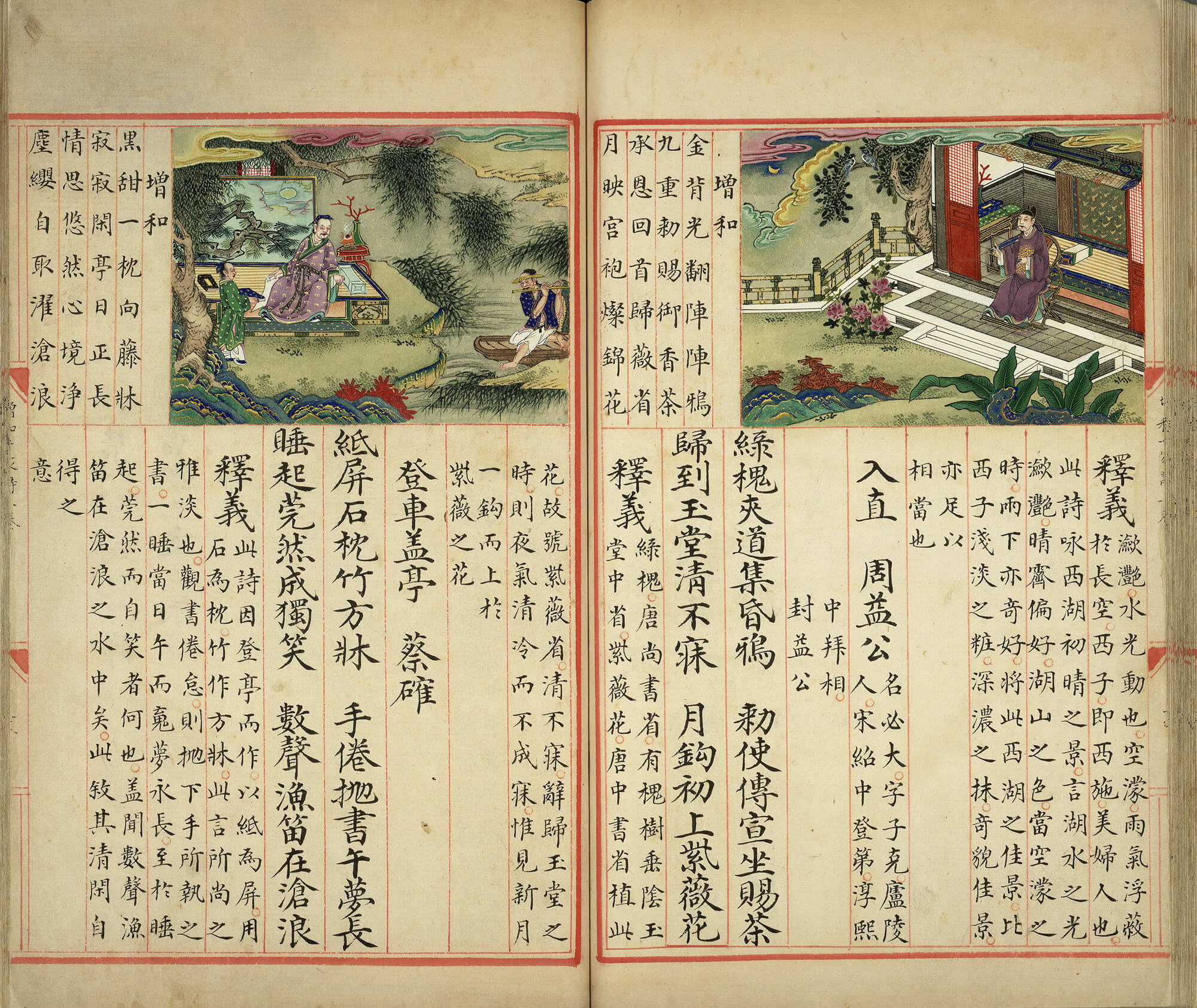

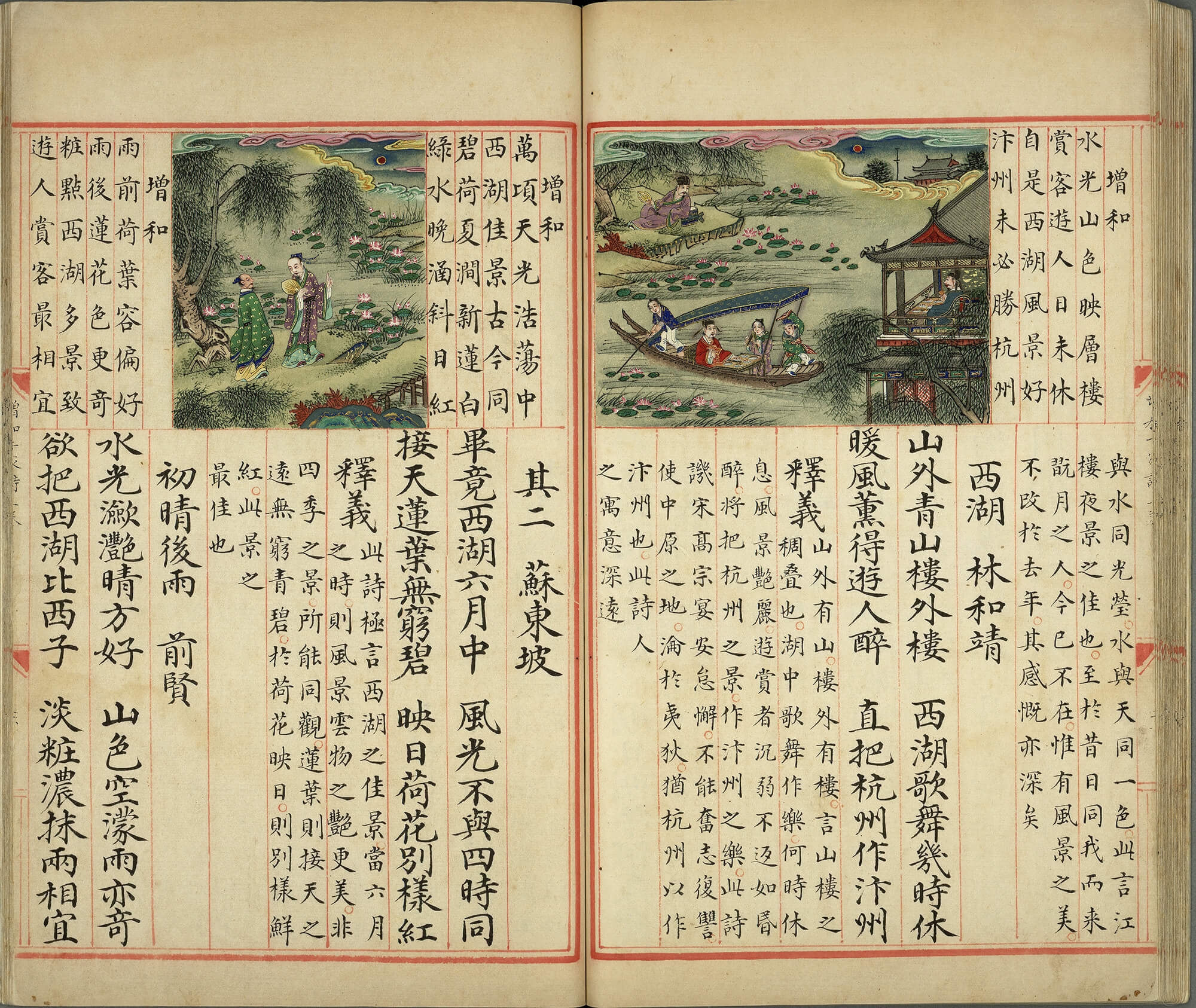

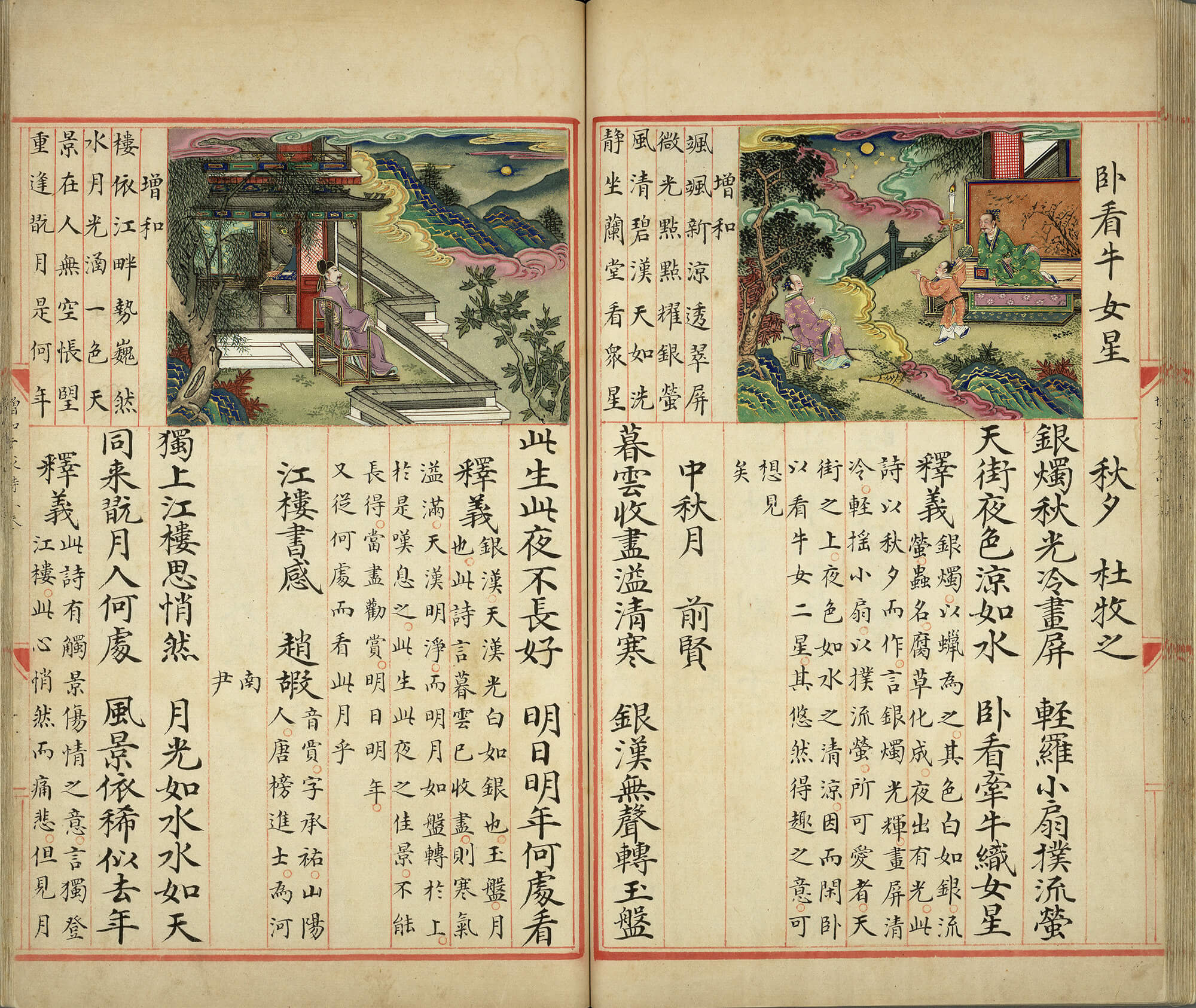

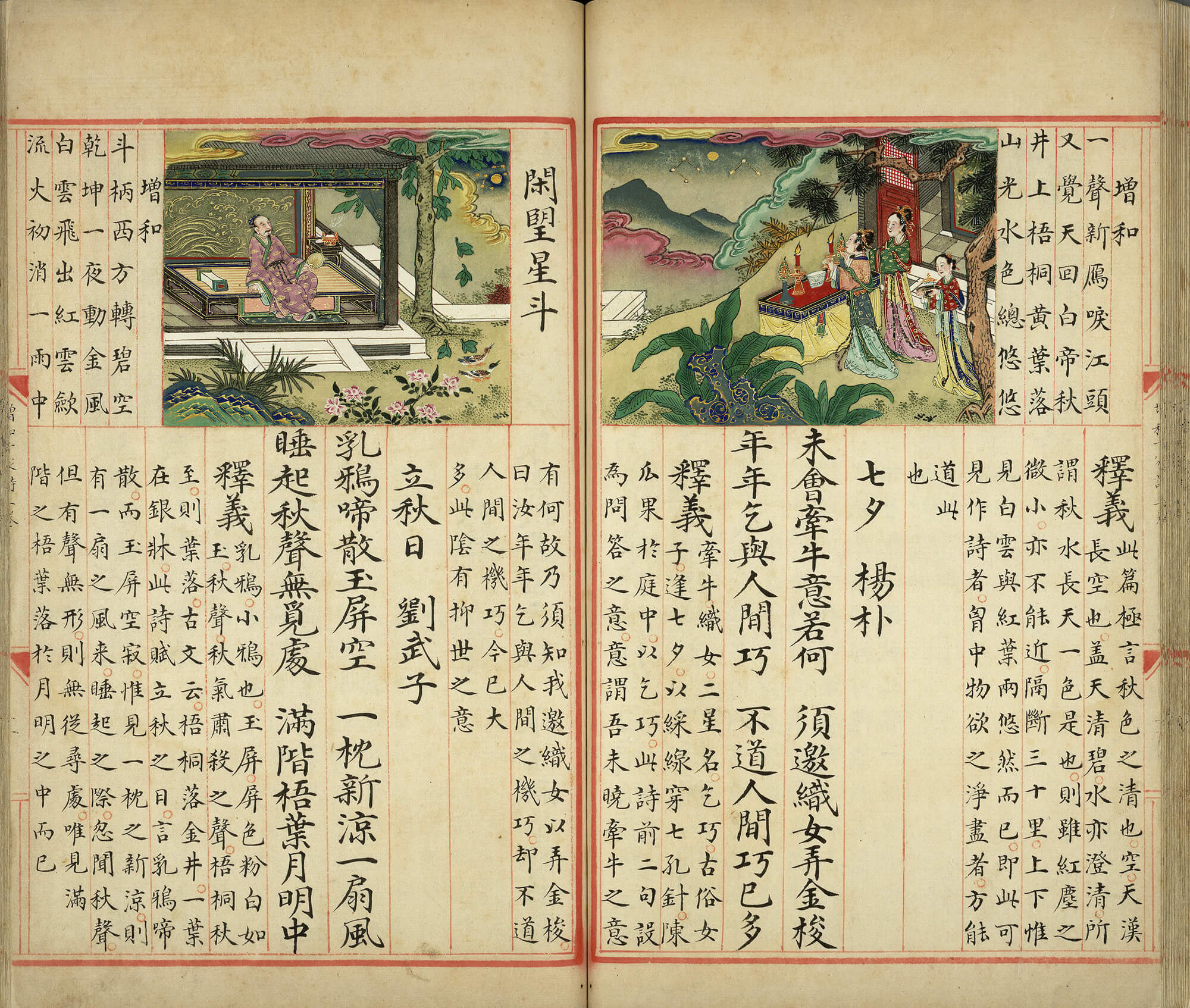

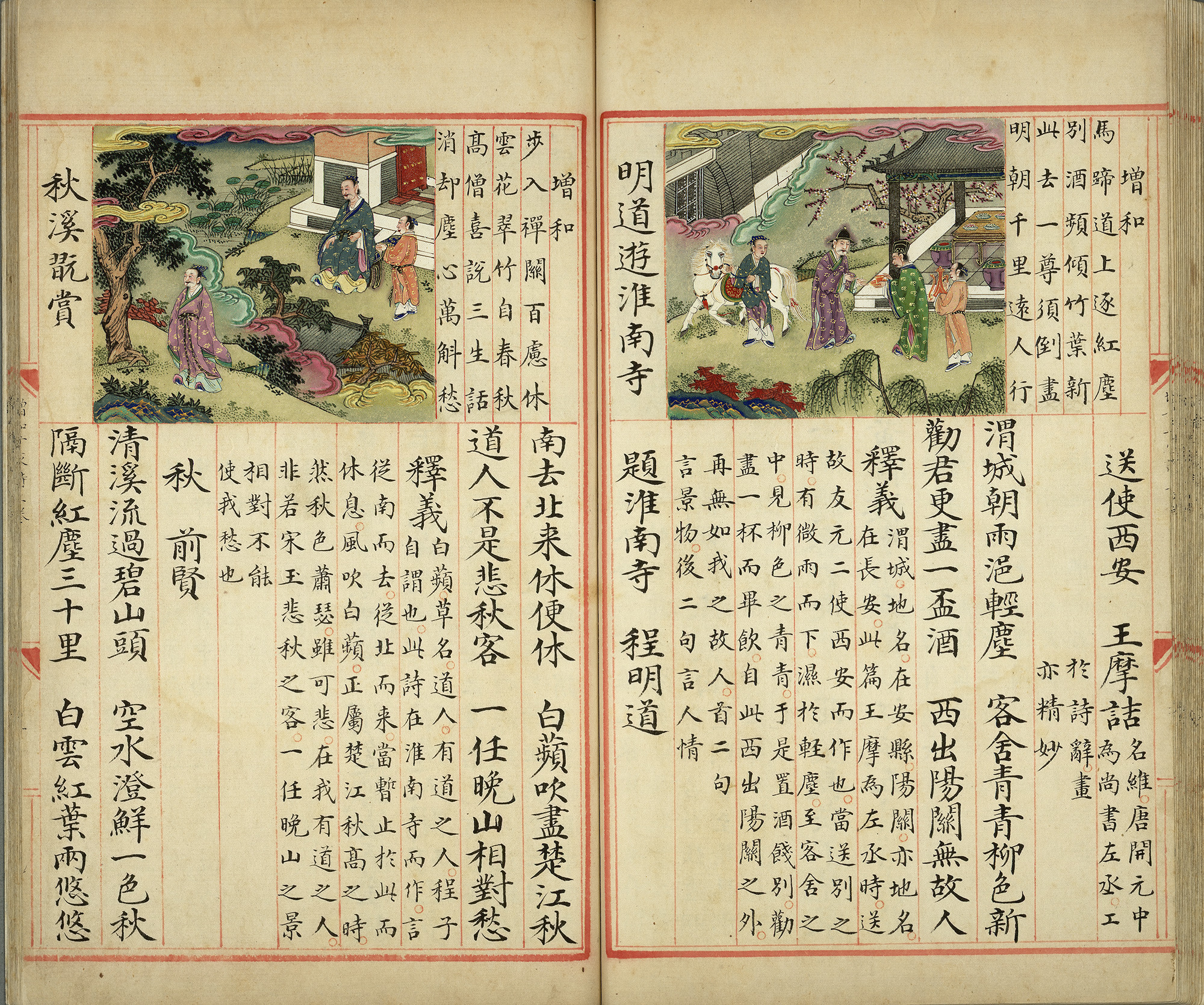

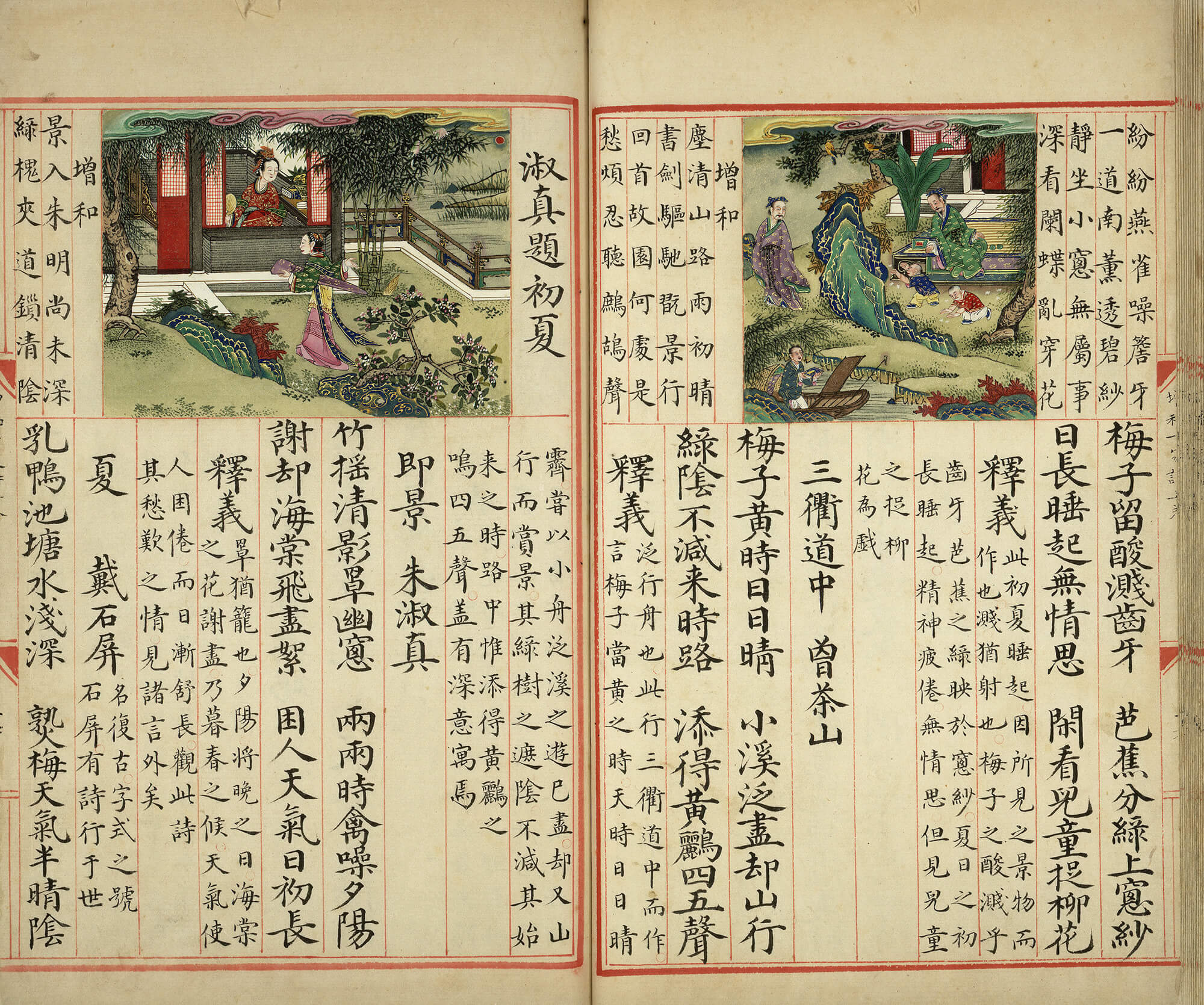

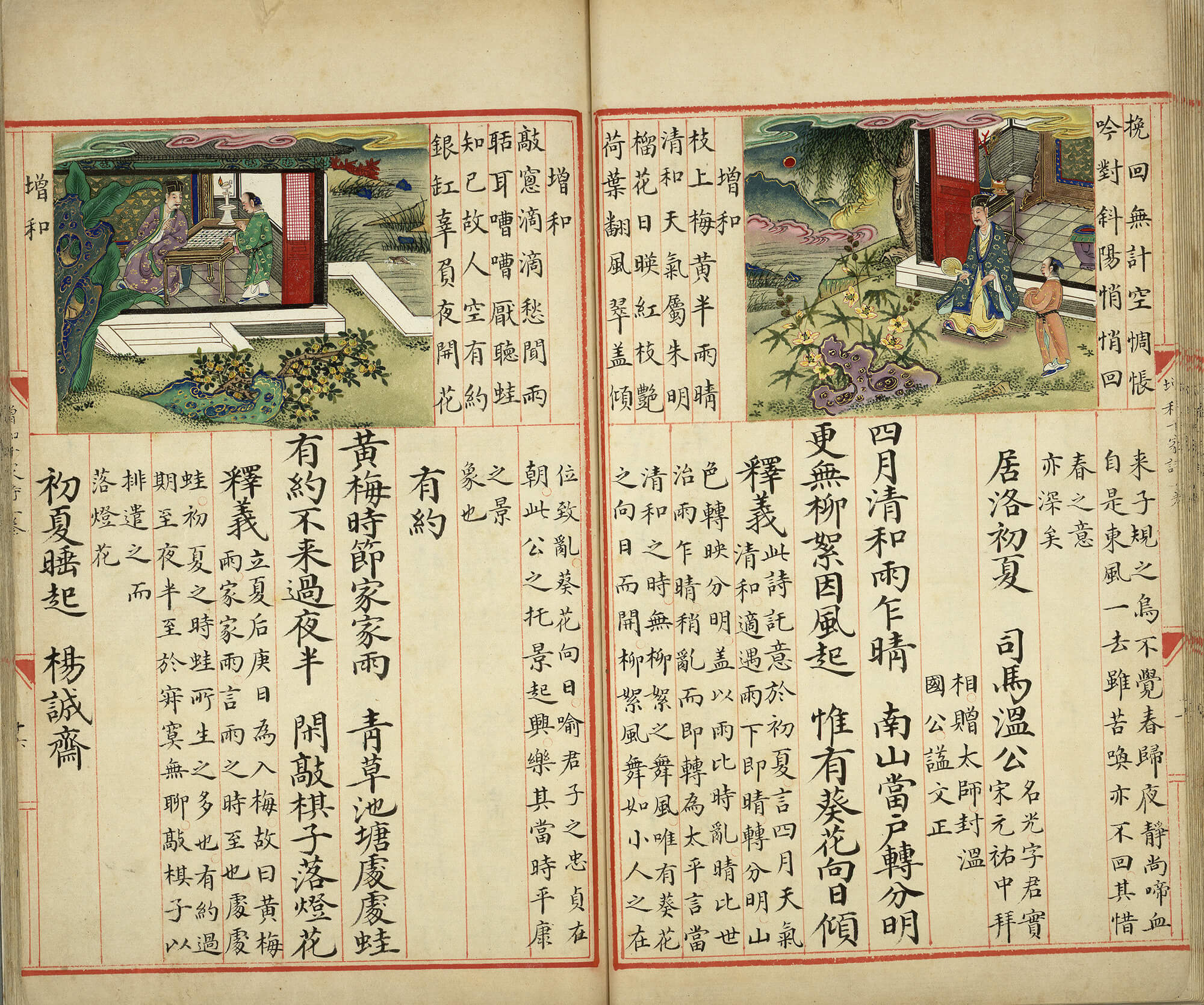

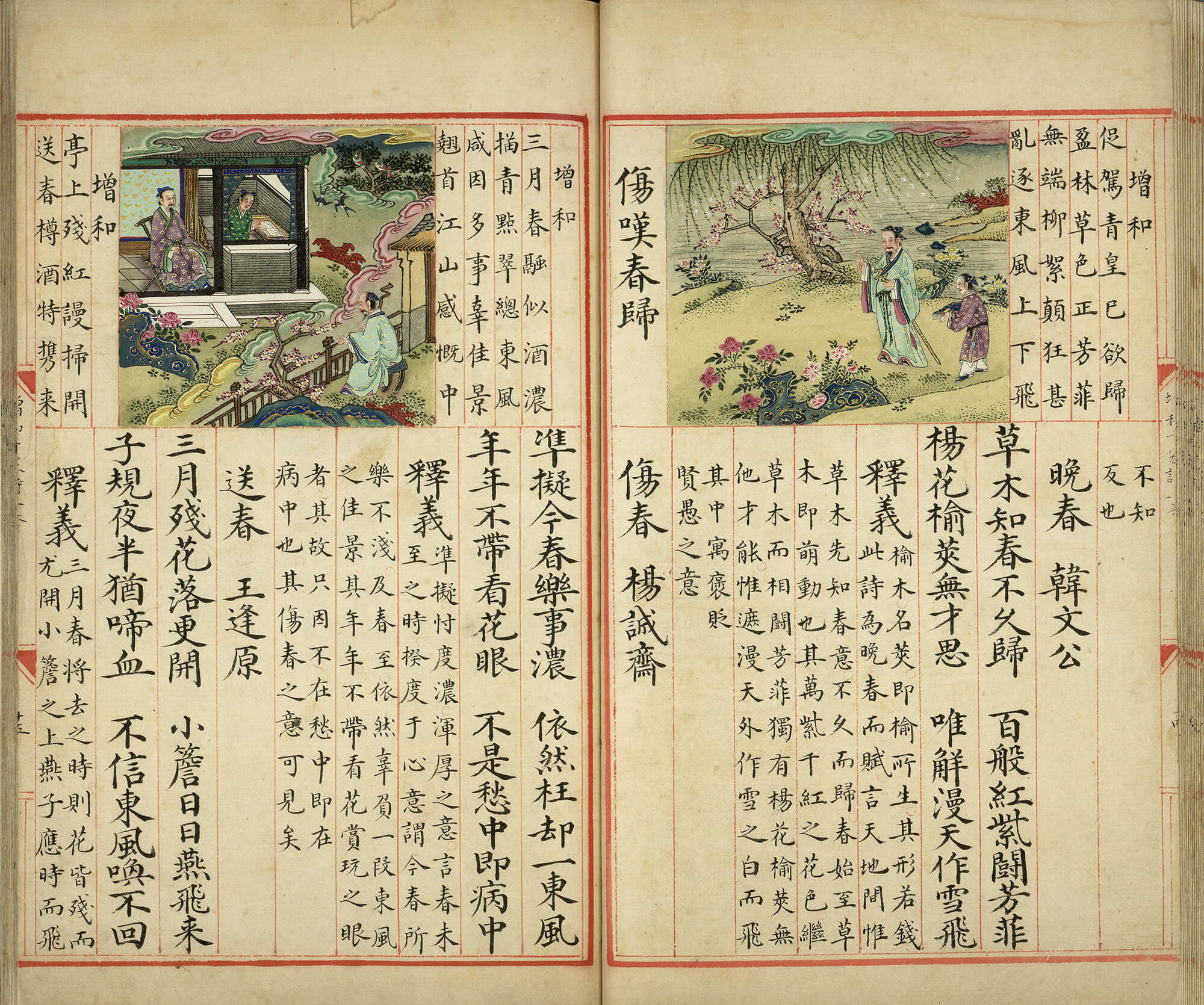

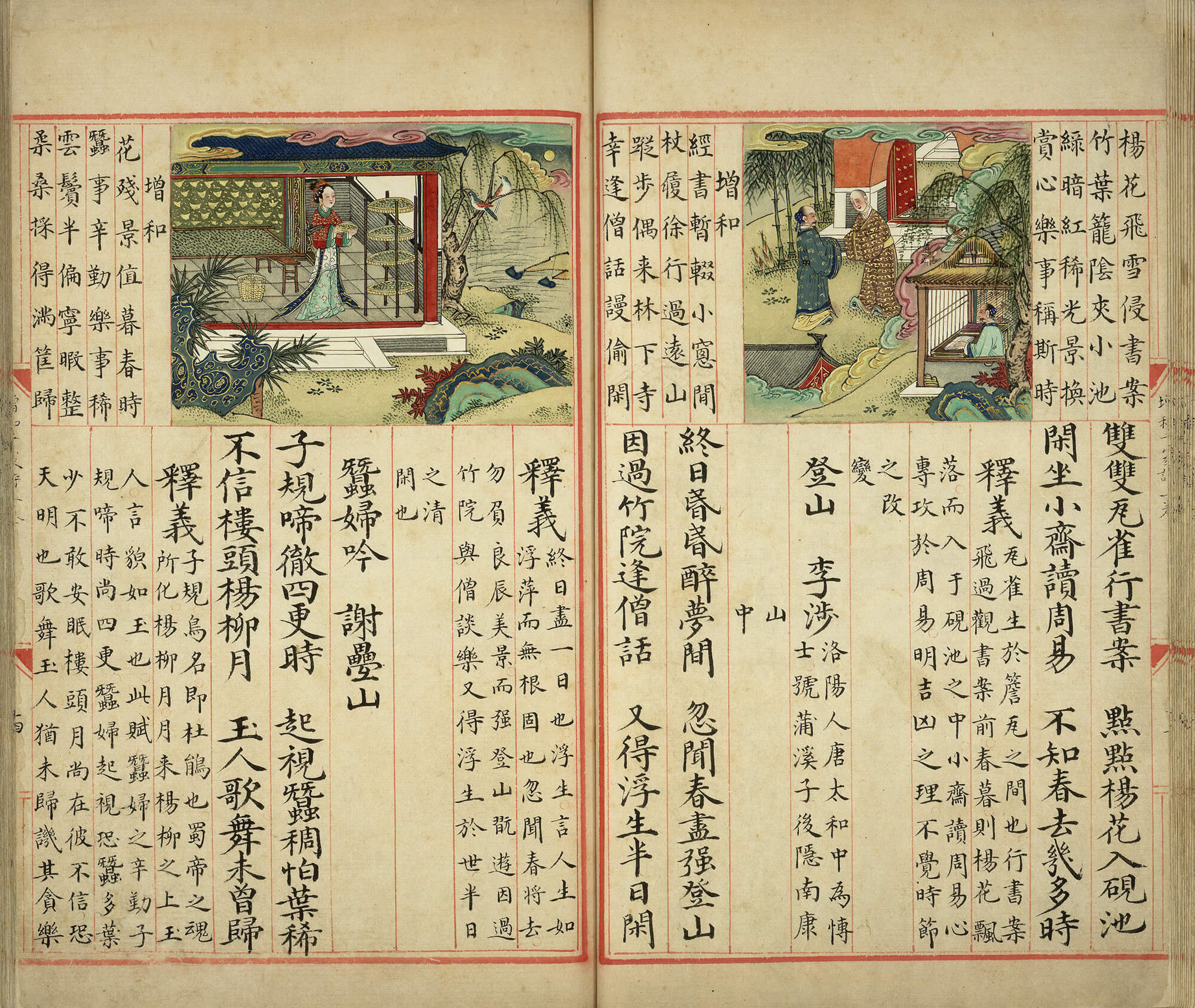

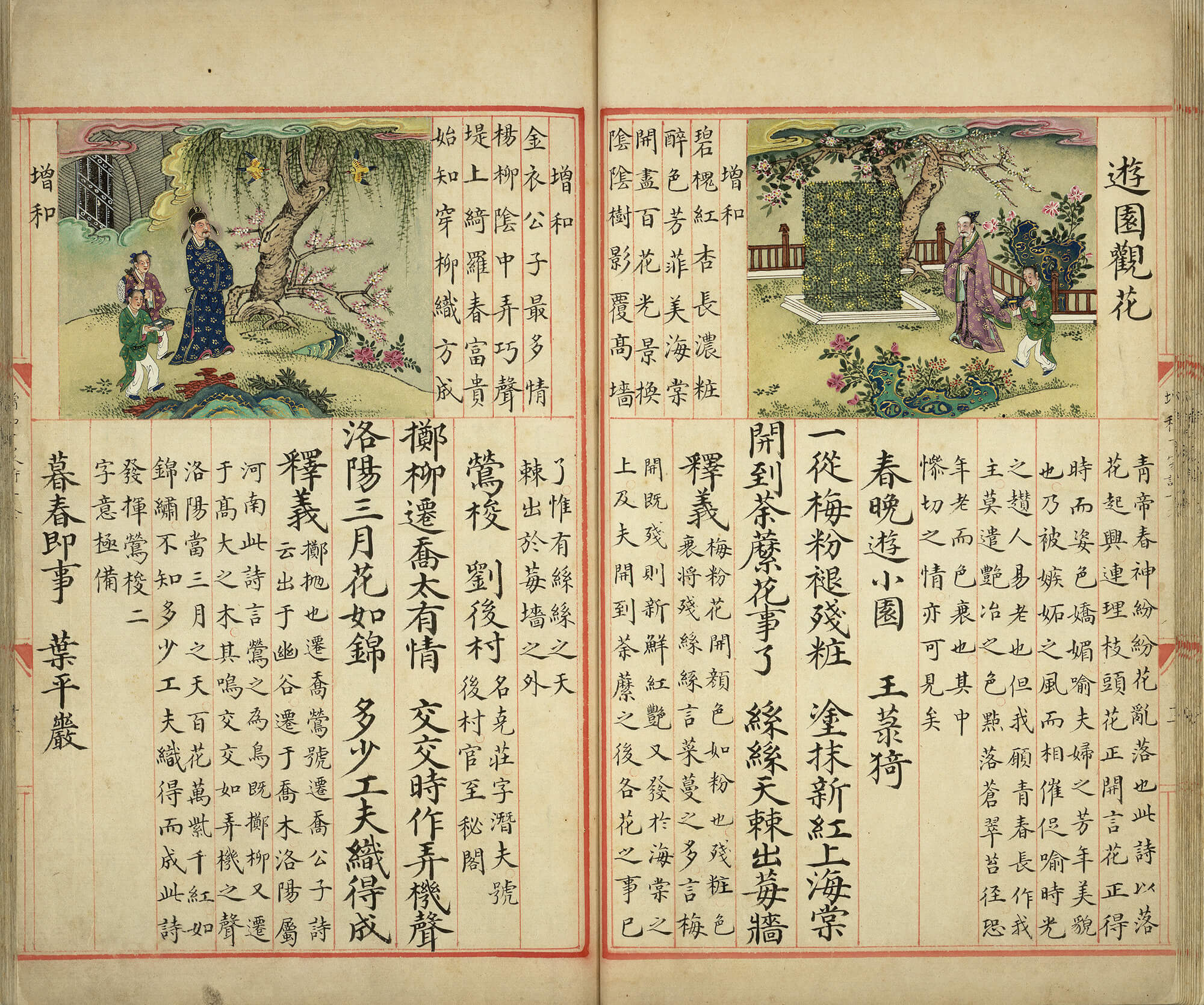

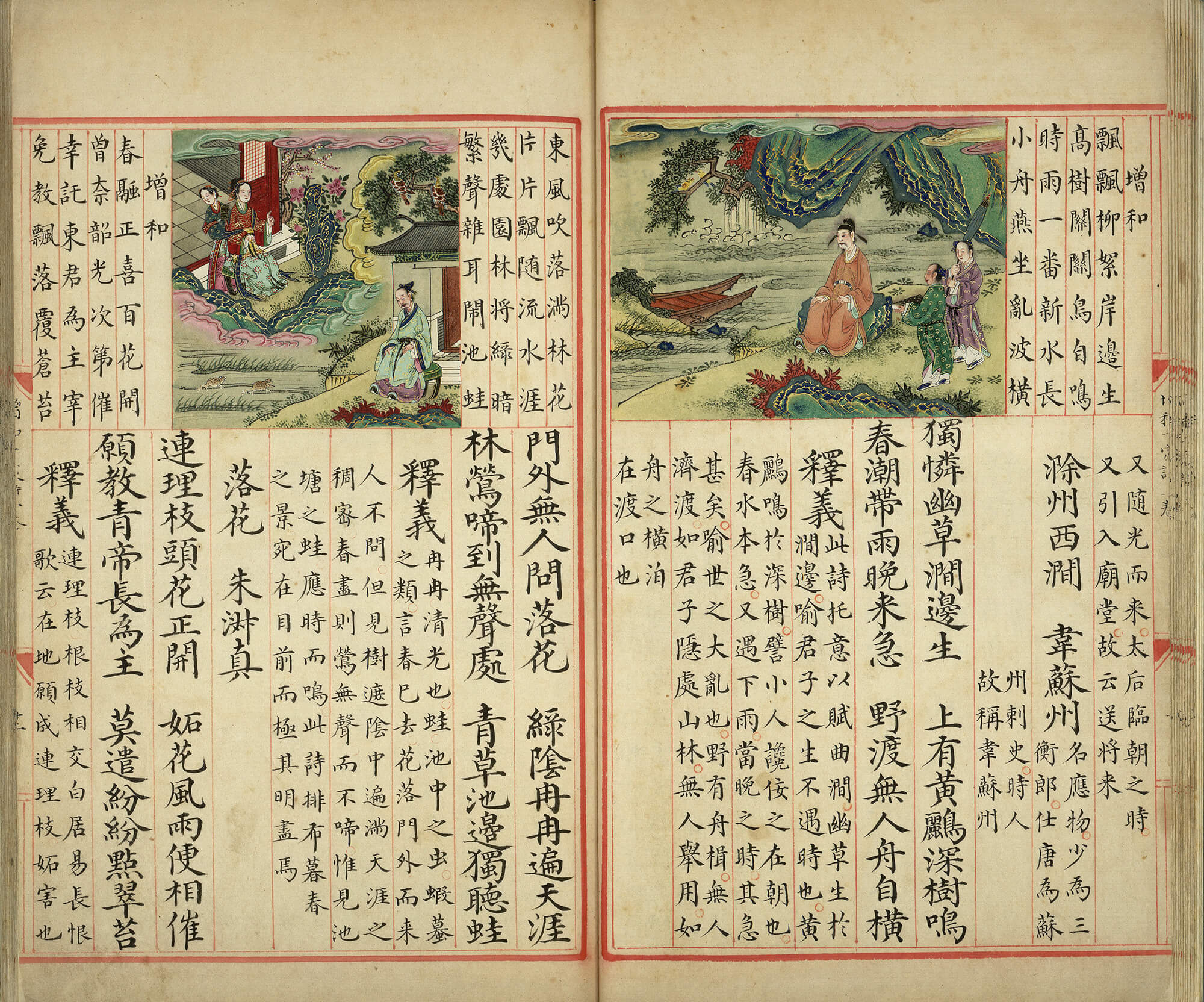

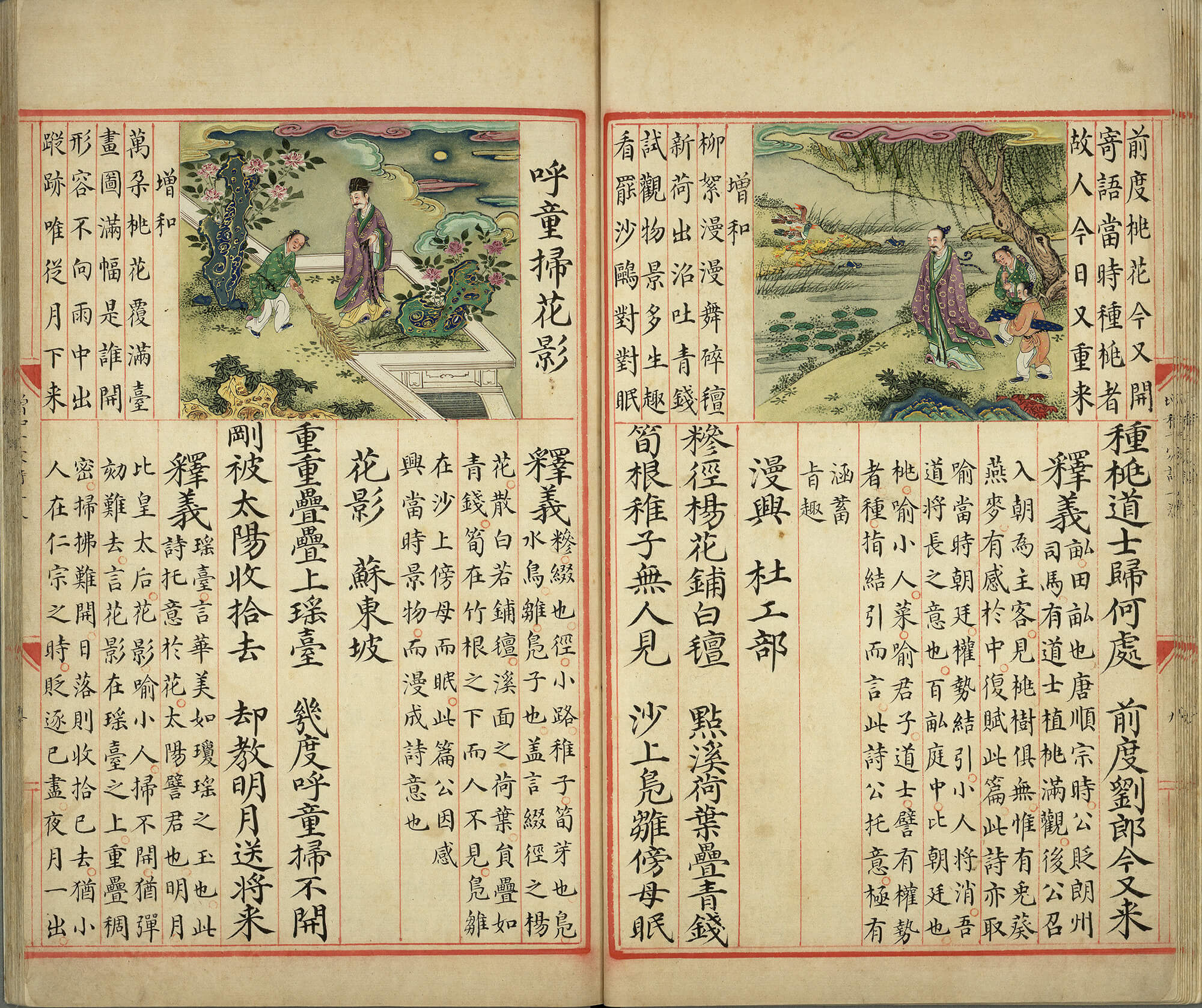

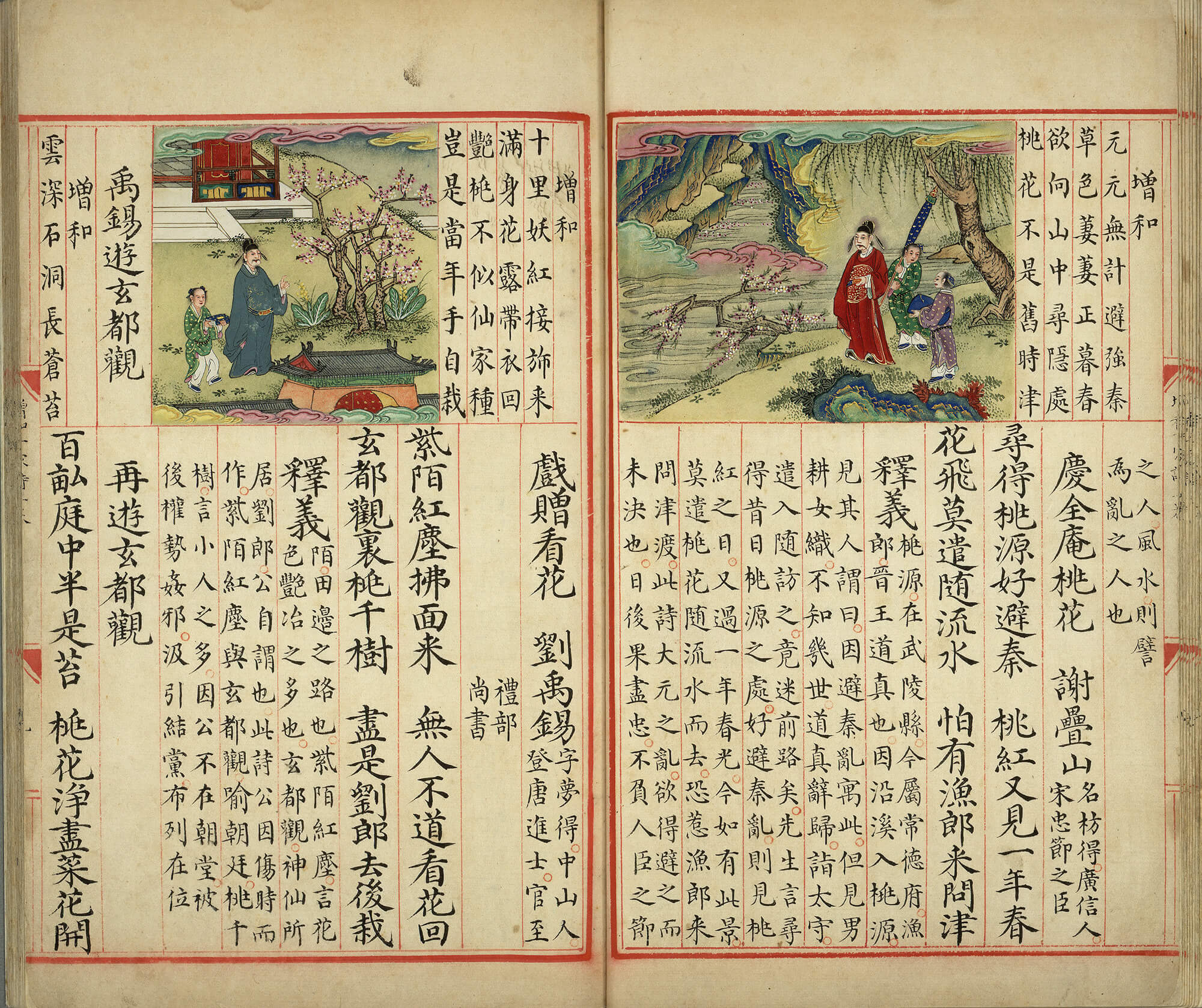

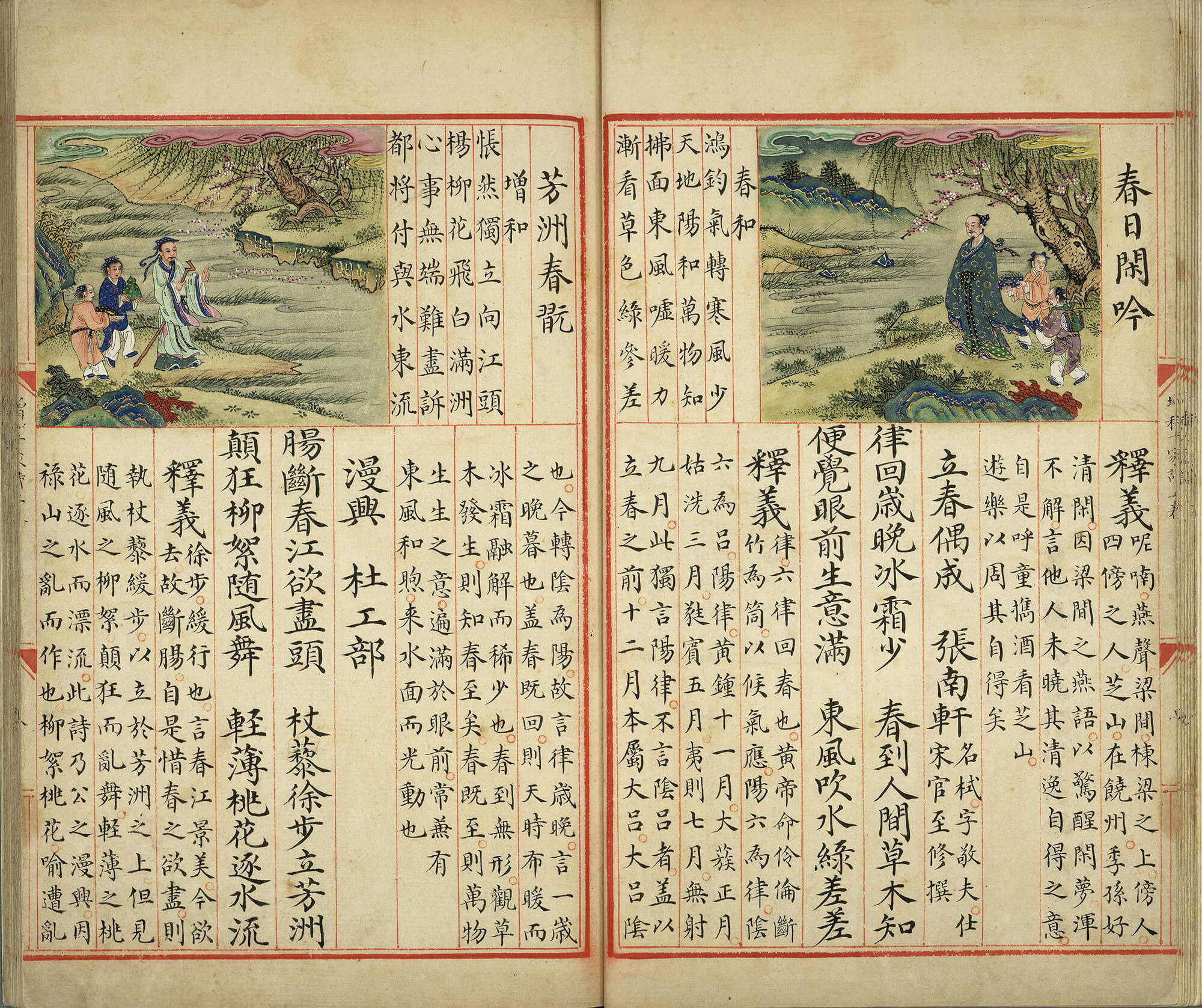

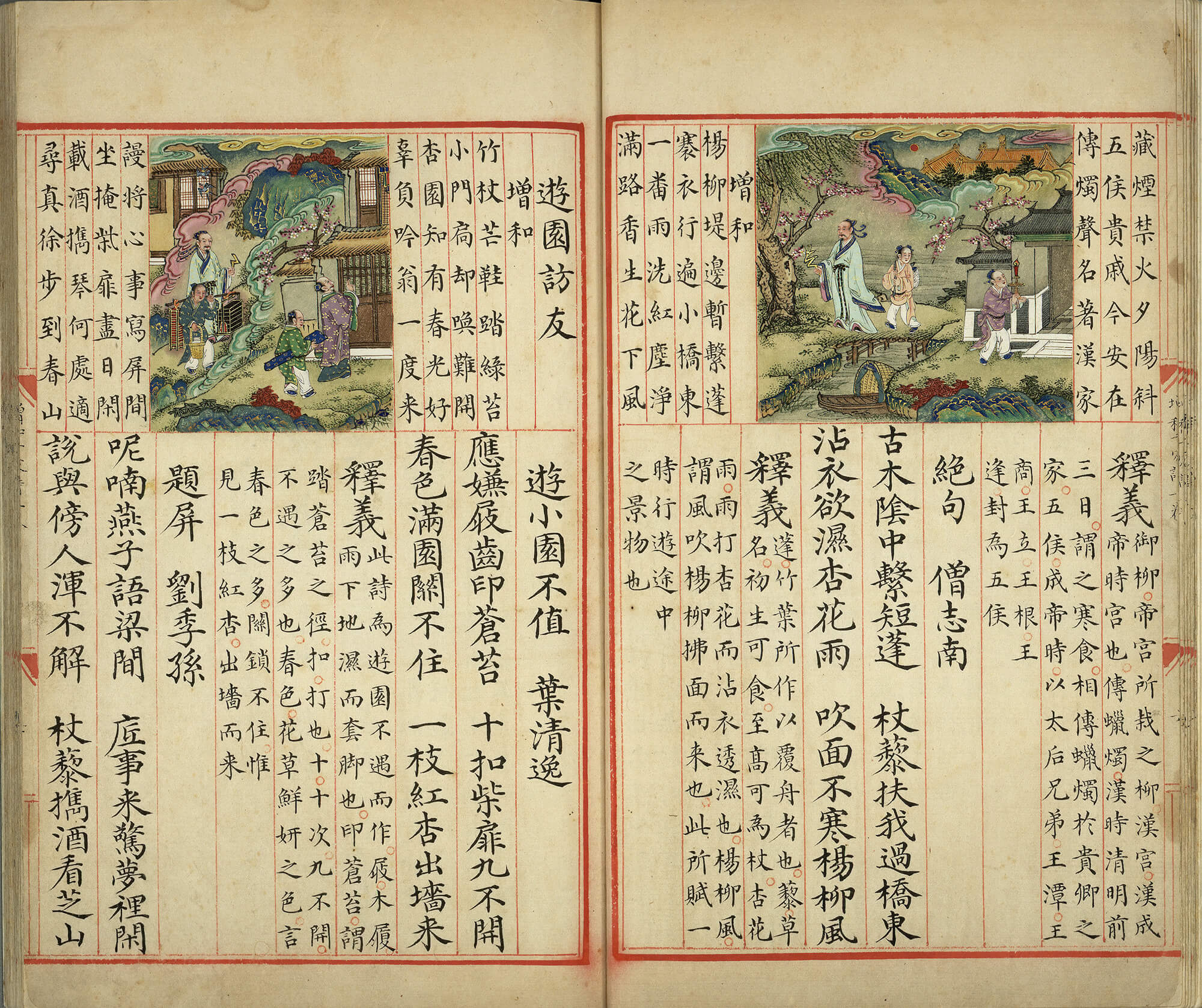

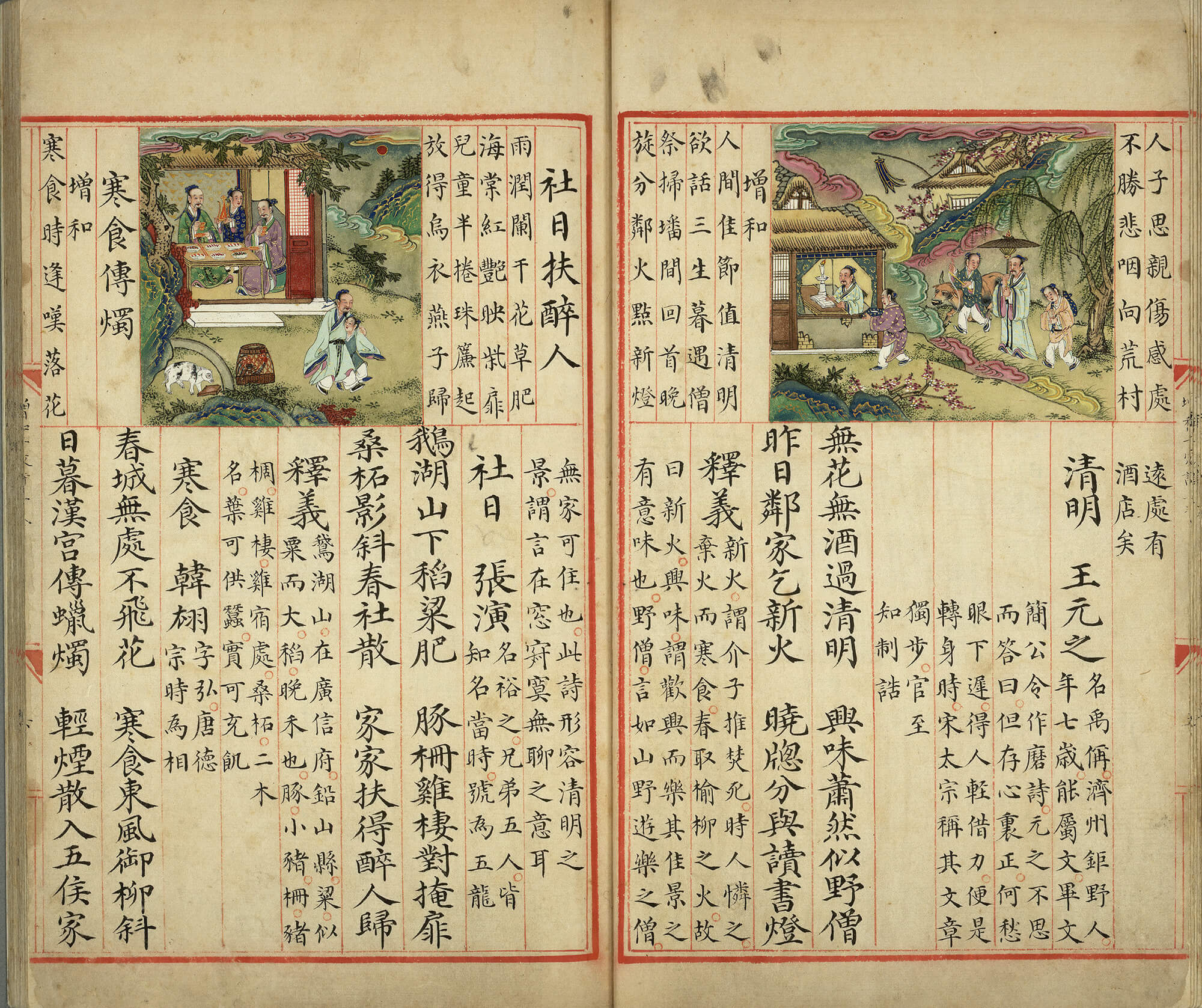

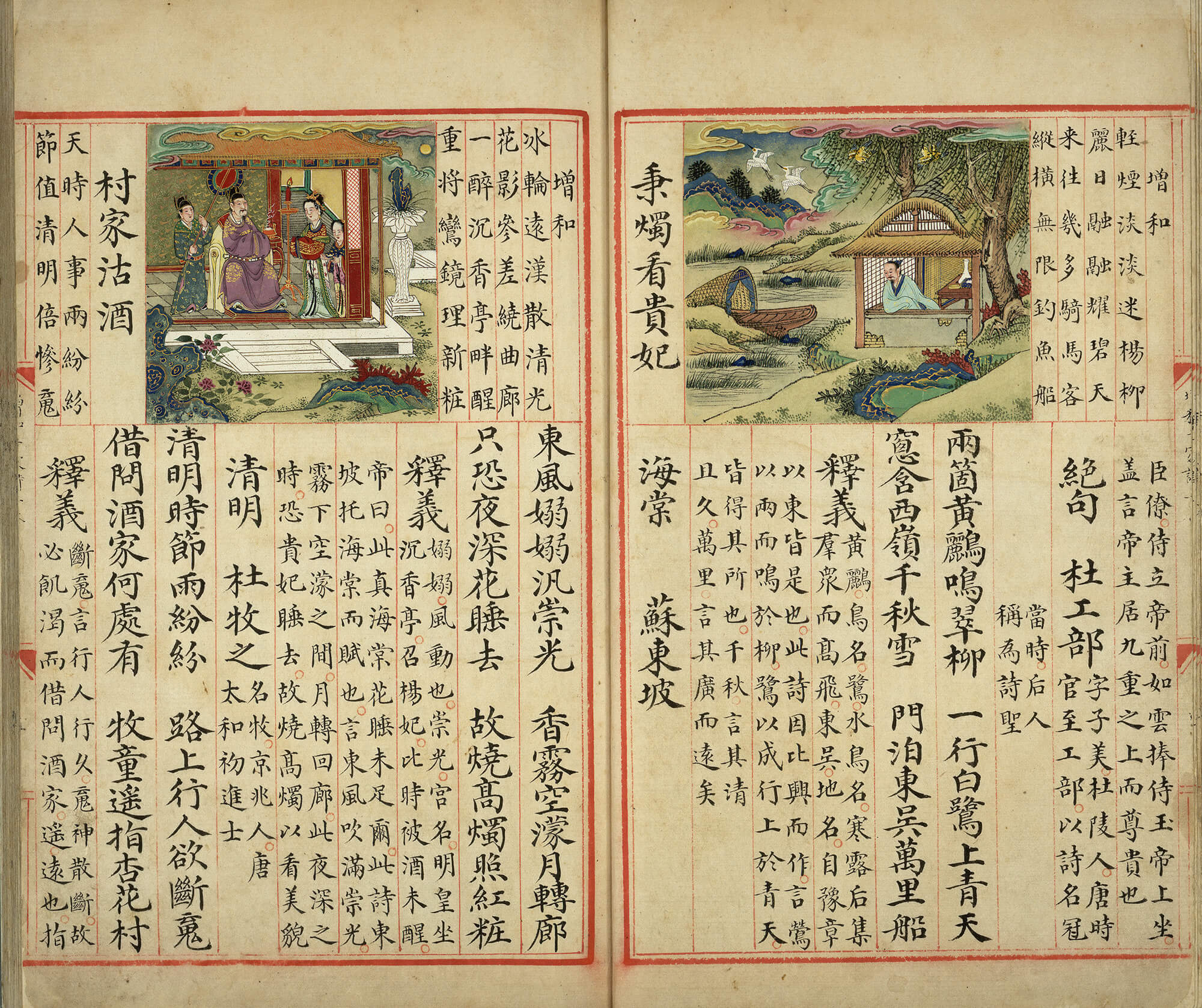

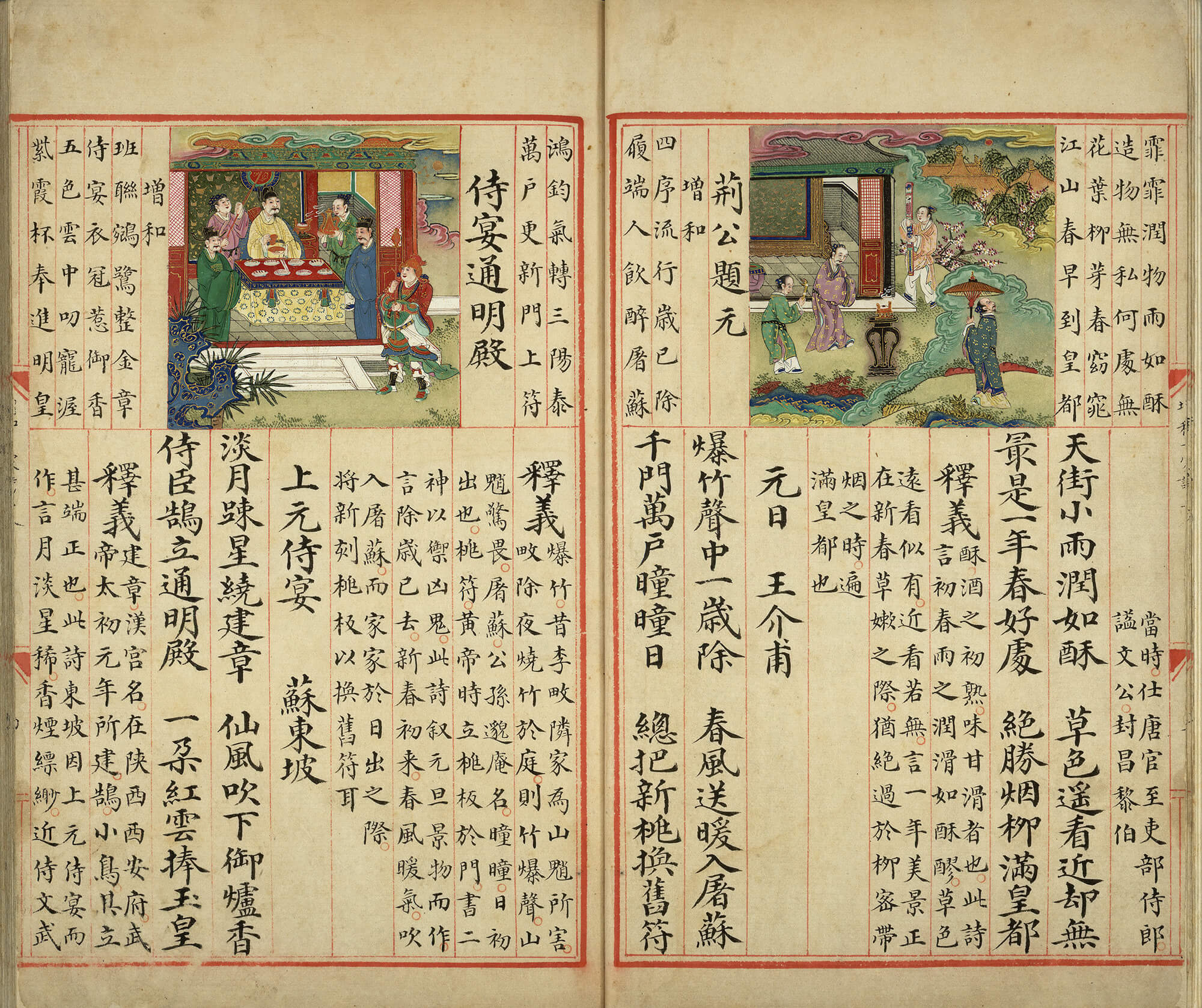

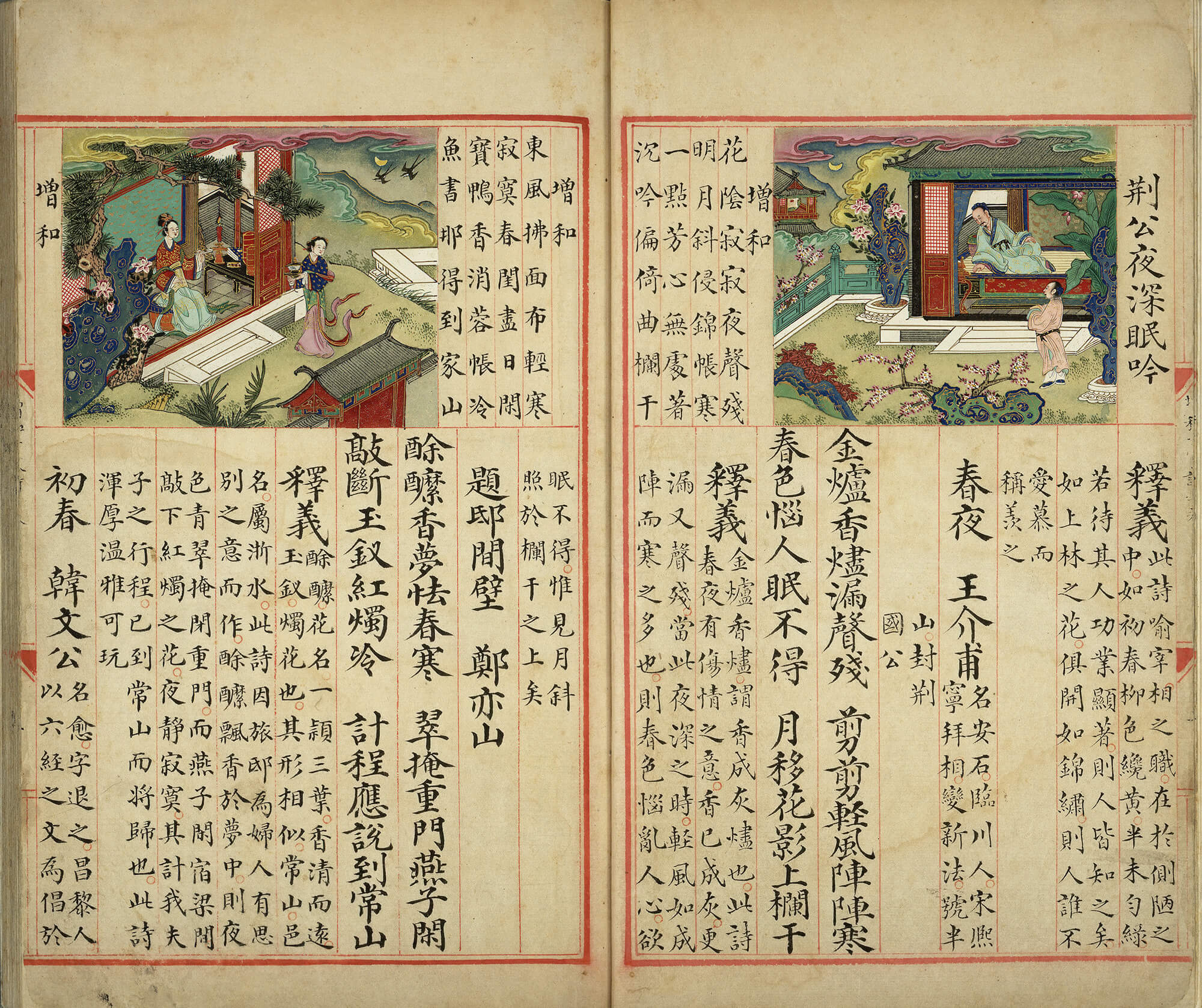

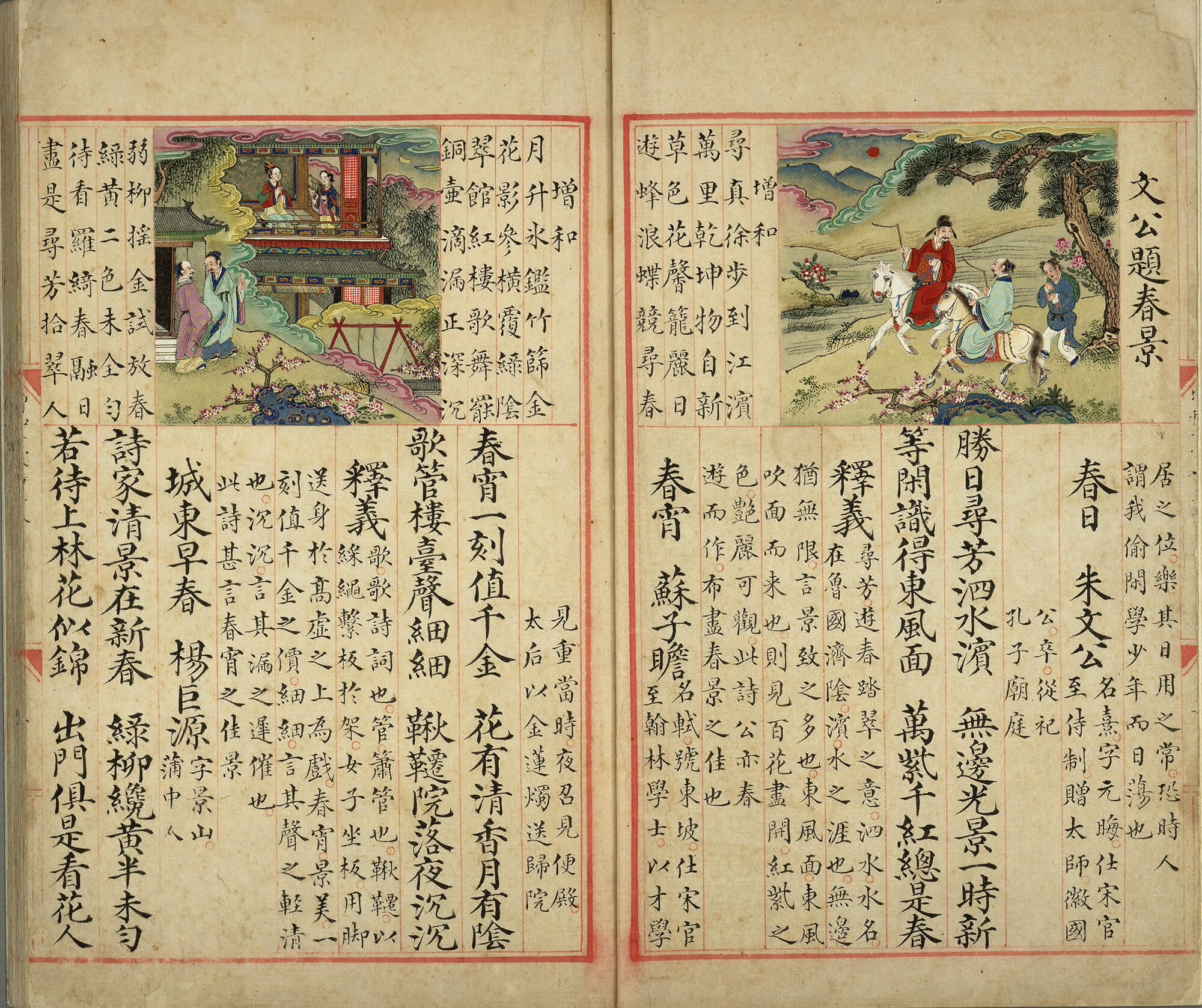

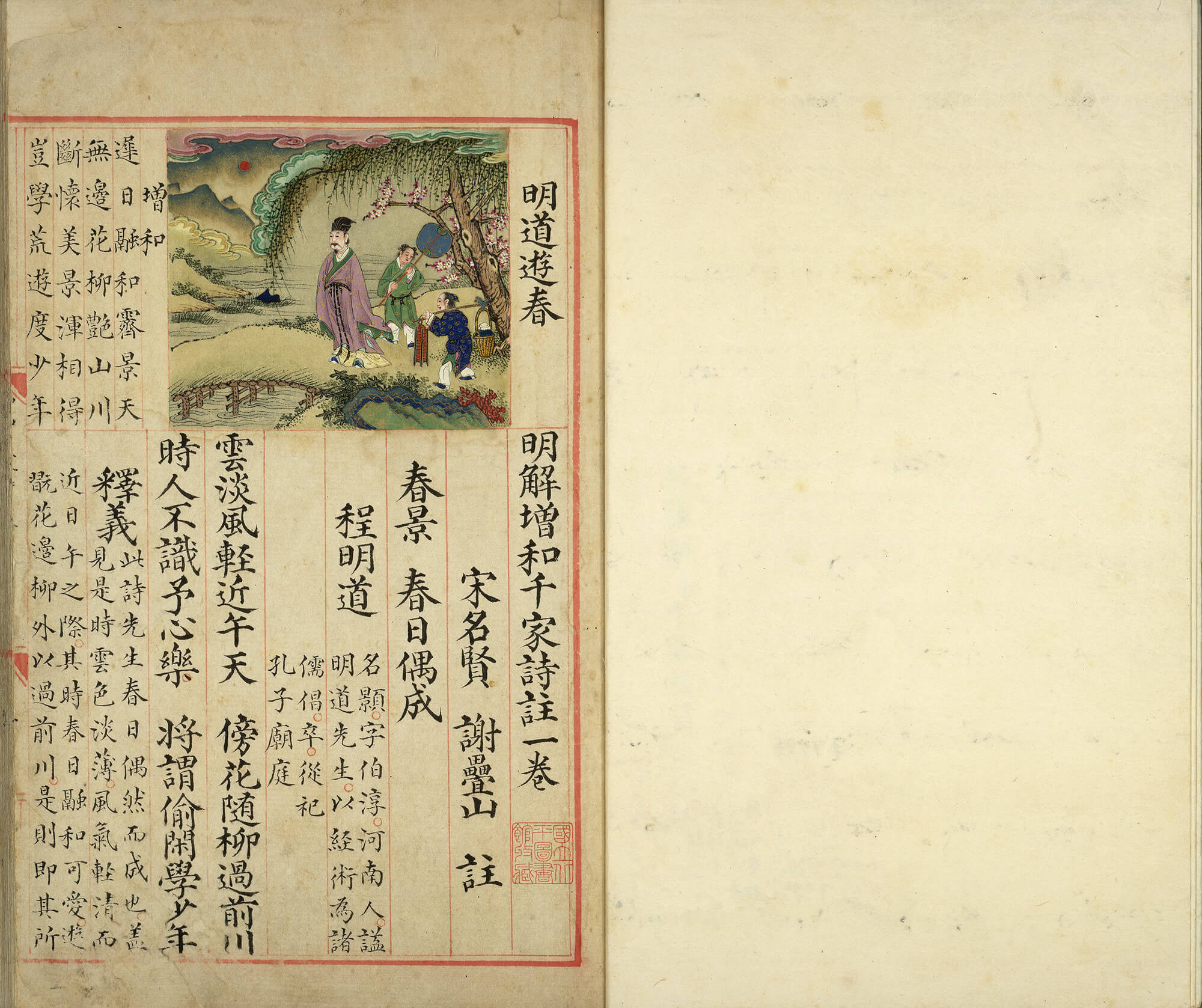

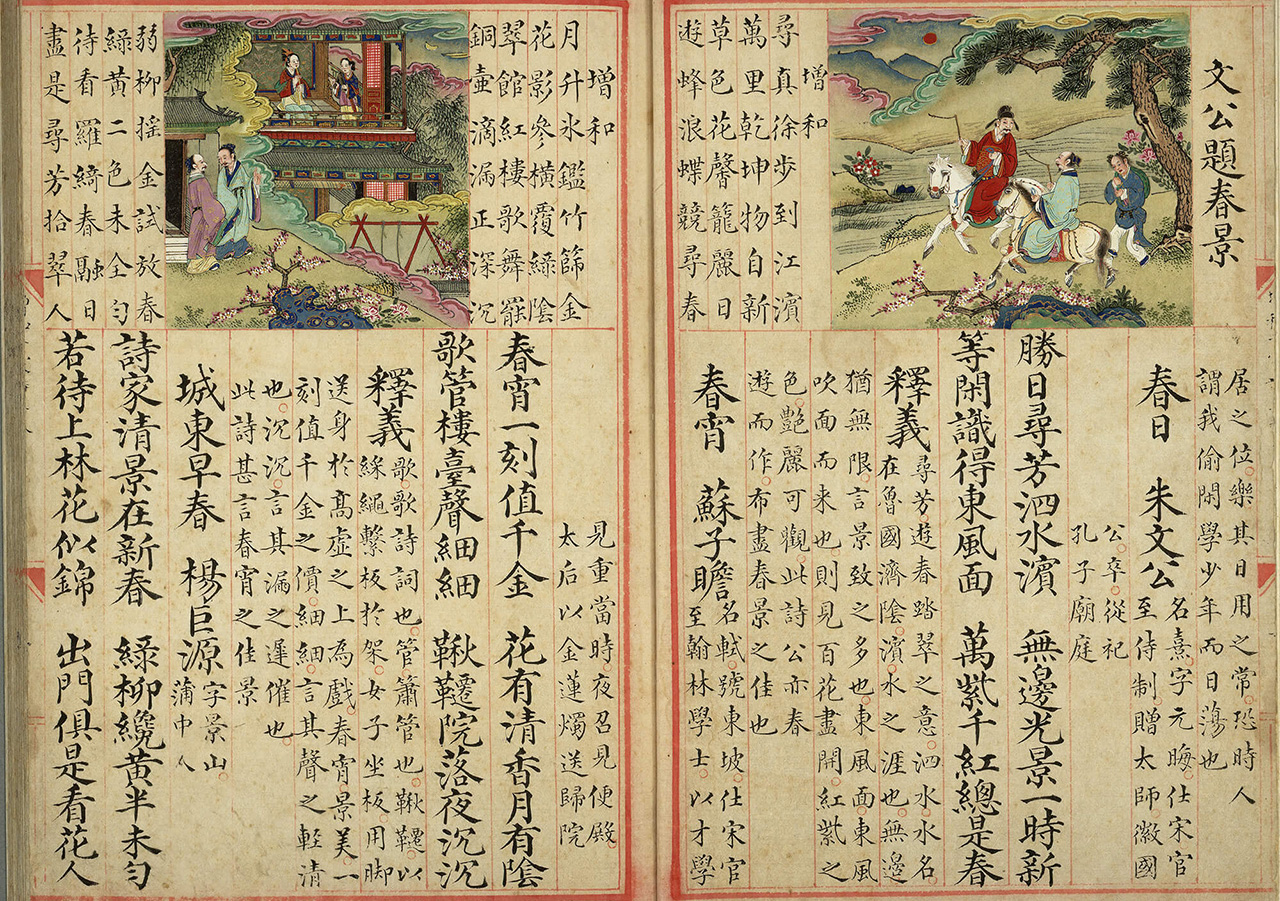

- Ming Commentary and Expanded Thousand Poets Anthology

- Annotated by Xie Fangde, Song dynasty

- Ming dynasty imperial edition manuscript

This book is a rarely seen, carefully crafted children's primer from the Ming dynasty court. In addition to selected Tang and Song dynasty poems with annotations and poems written in response, it also includes colored illustrations by court artists.

The verses follow the authors' shifting thoughts, and the imagery touched upon from one line to the next can vary significantly. How did the artist respond to these shifts? The illustrations here on the left and right are composite images for two different poems. Can you identify the various techniques the artist used to combine different poems into a single picture?

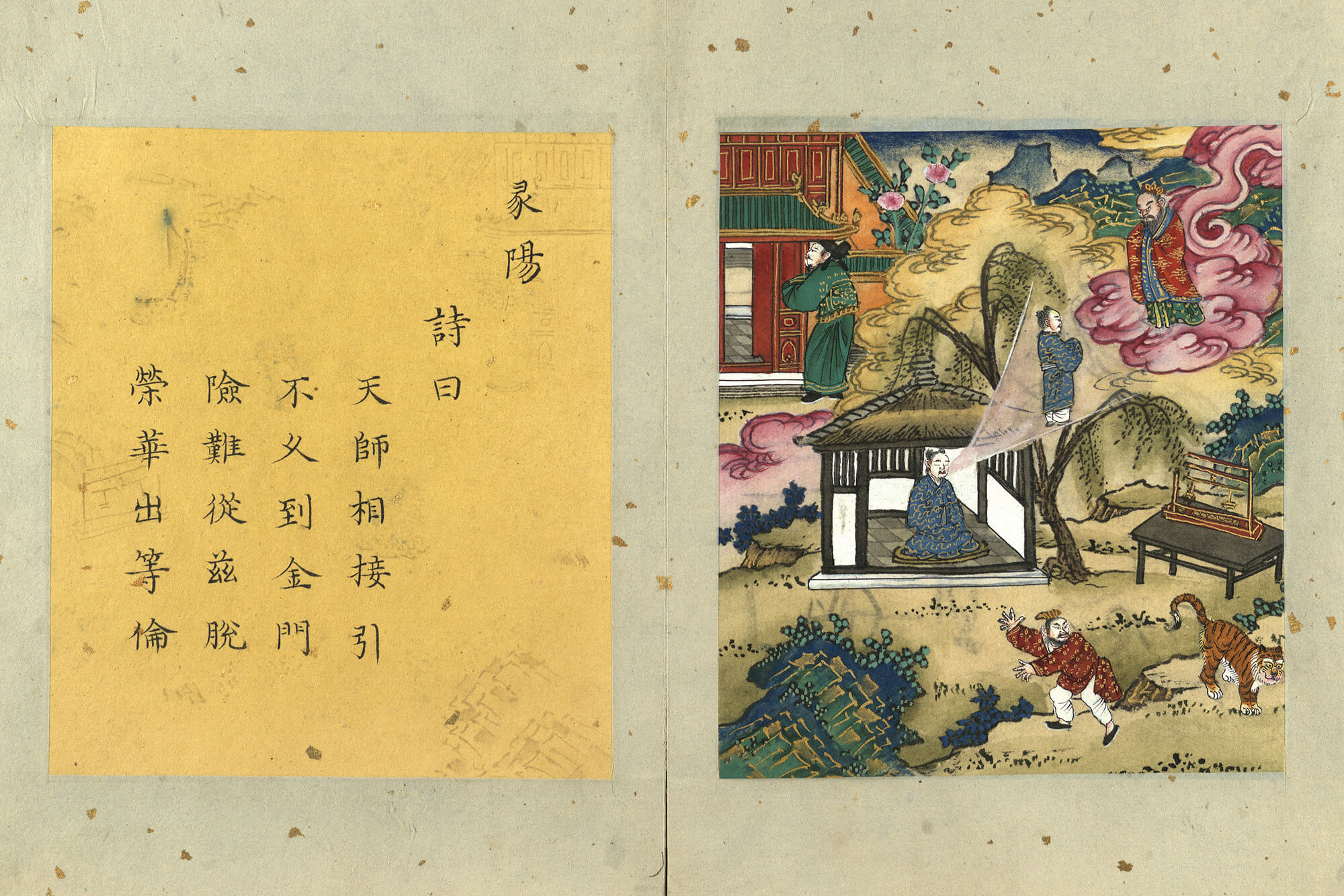

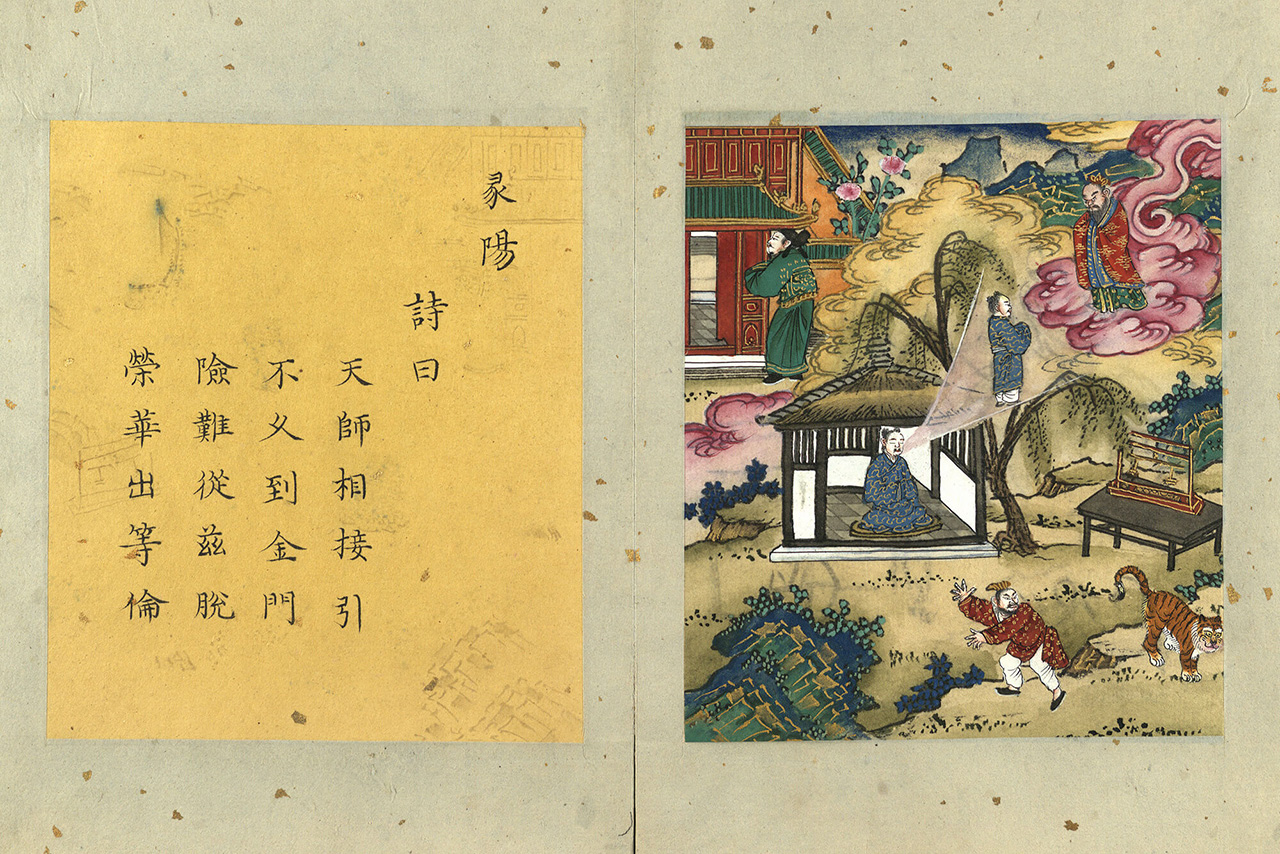

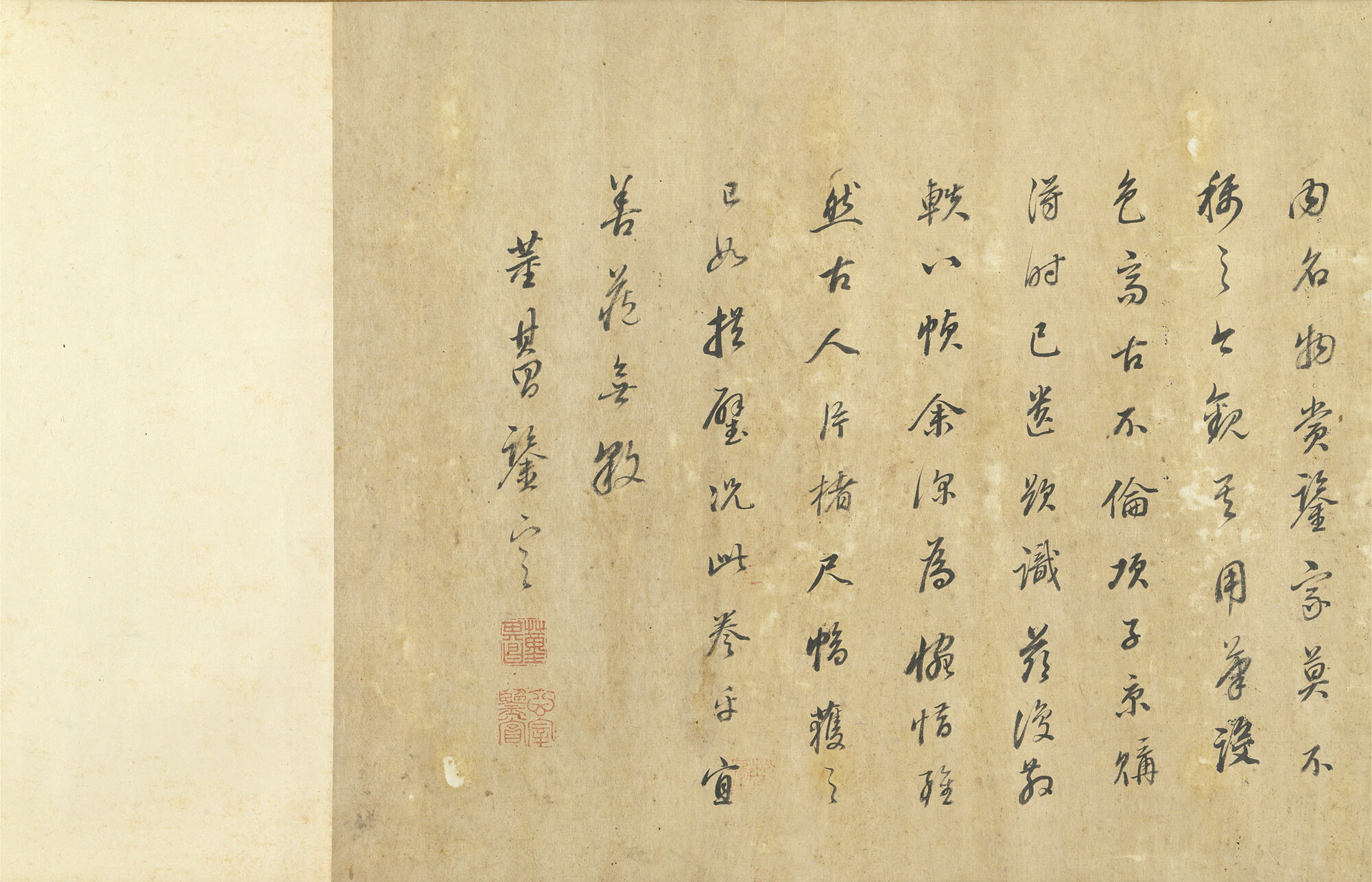

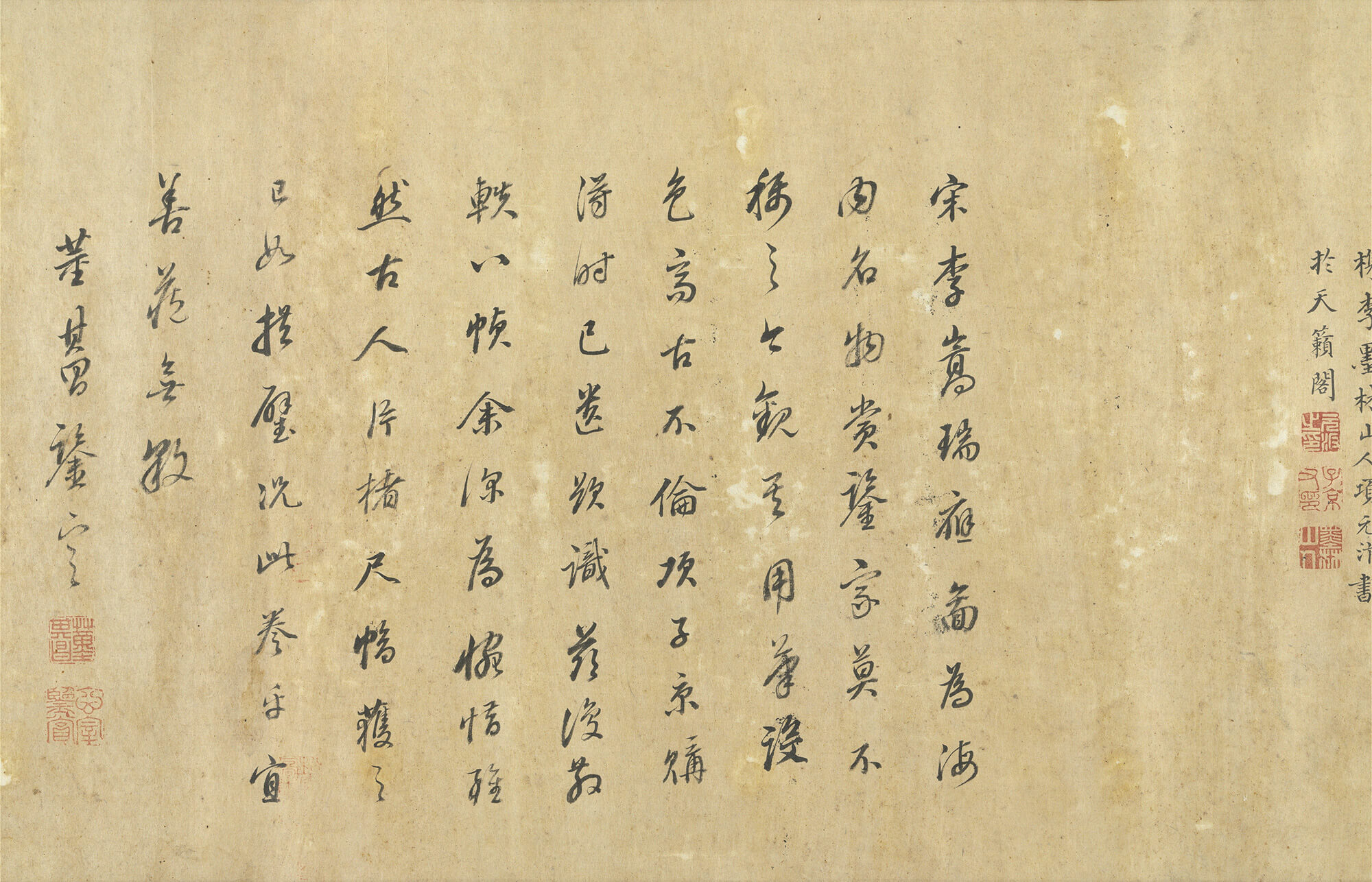

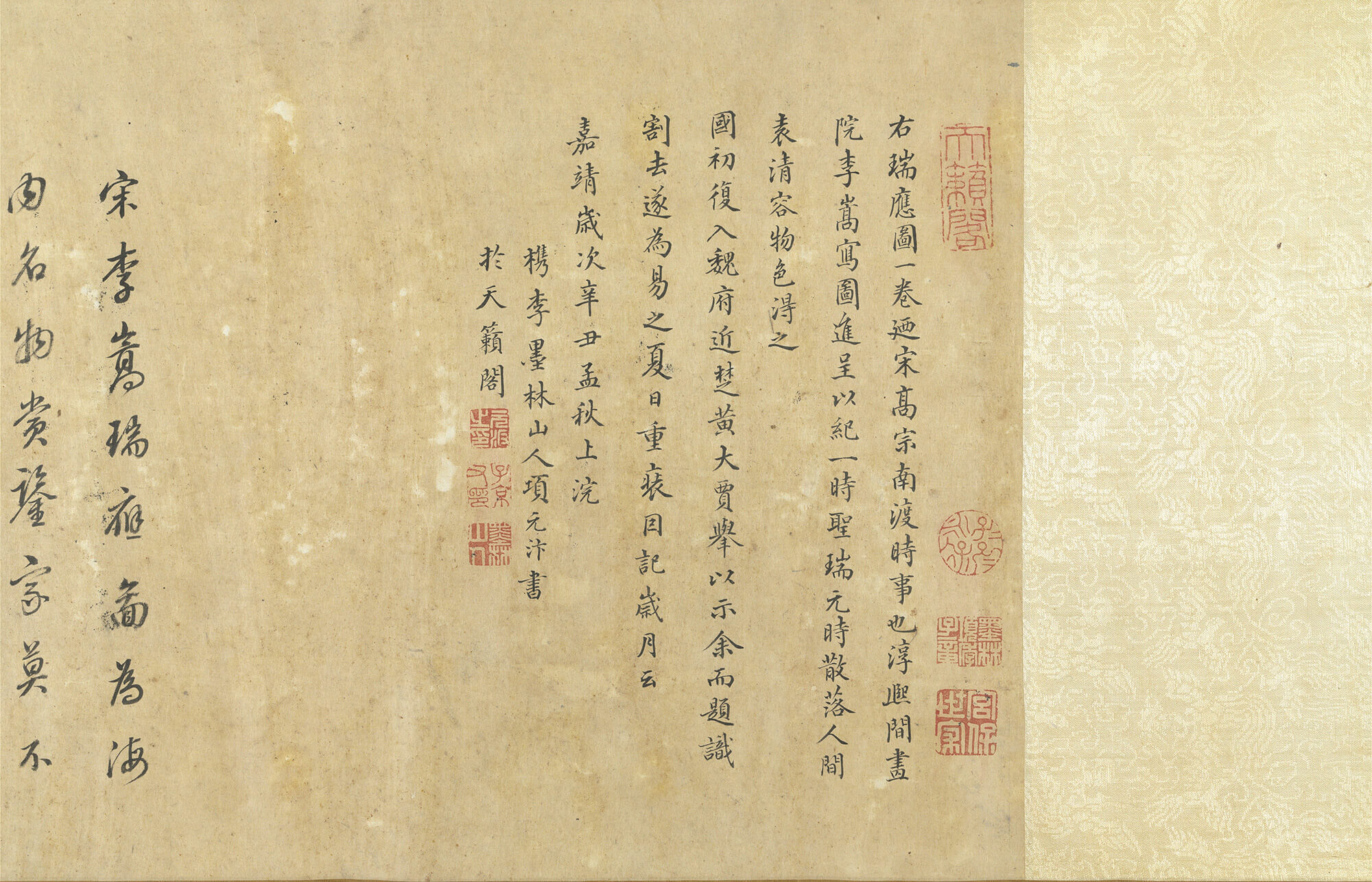

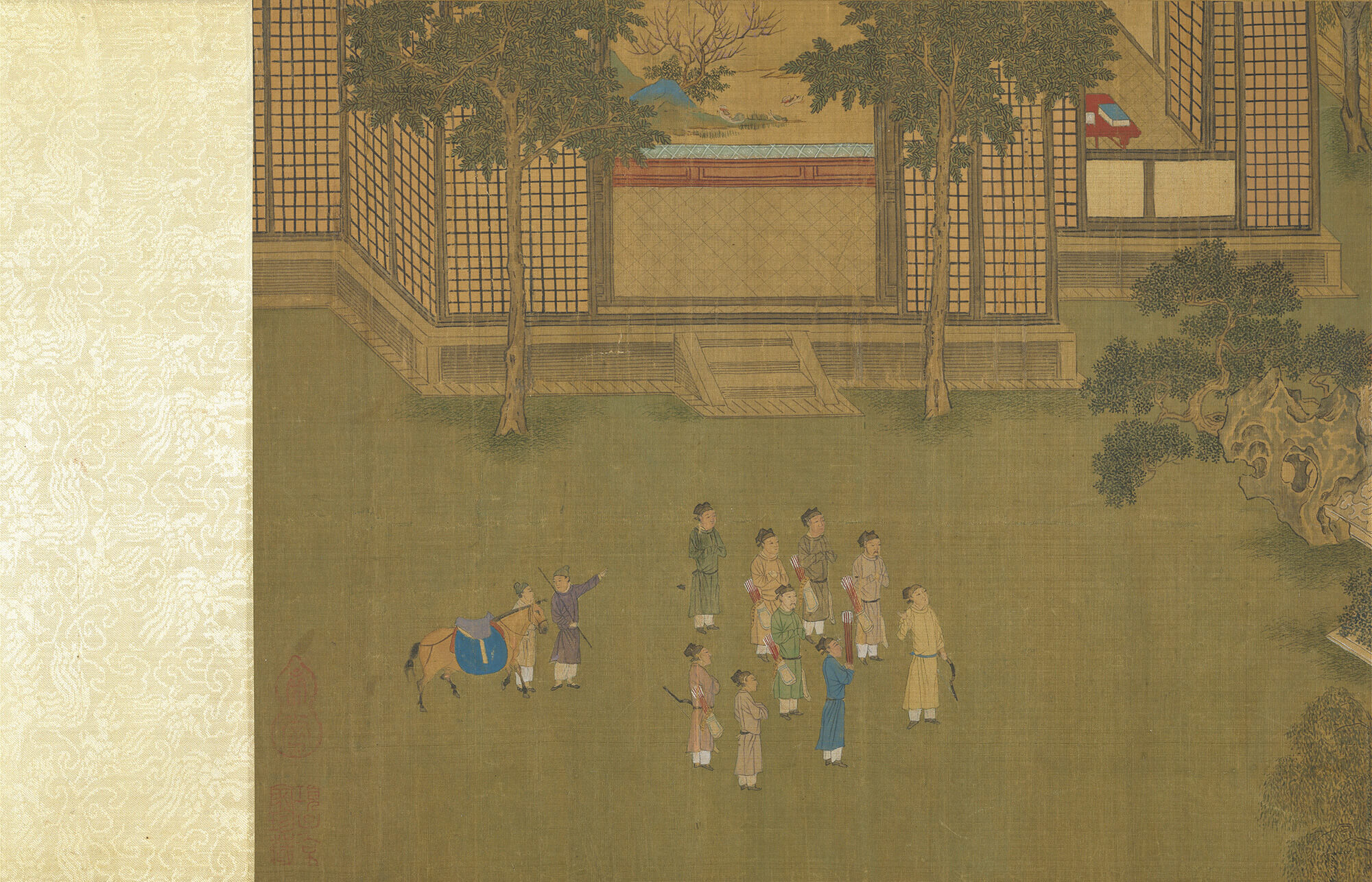

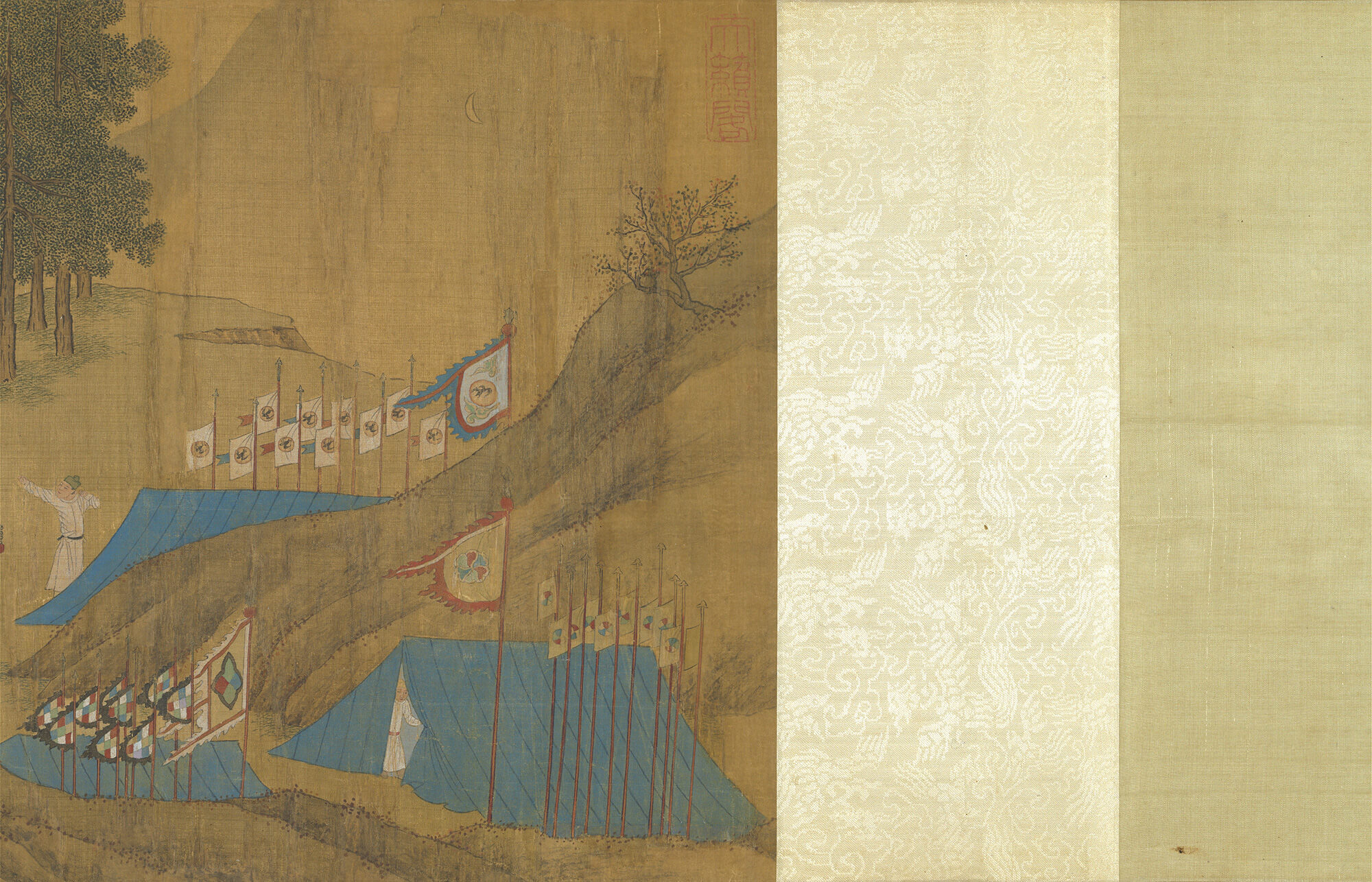

- Illustrations of Auspicious Responses

- Attributed to Li Song, Song dynasty

- Silk

The term "narrative painting," also known as "history painting," means that the genre portrays not only fictional stories but also points to events that actually occurred. Yet, how much truth do they contain?

The work Illustrations of Auspicious Responses attributed to Li Song(c. 1170-1255) is an example of such thought-provoking imagery. In the early Southern Song dynasty, ministers compiled auspicious omens during Emperor Gaozong's (1107-1187) rise to power in order to legitimize his rule, and court painters illustrated them. In this section, "Removing the Robe in a Dream," the painting depicts more than just Gaozong sound asleep in a military tent. Fascinatingly, this scene also portrays Emperor Qinzong(1100-1156) taking off and handing over his robe to Gaozong in a dreamland, floating into appearance like clouds and mist.

Story Introduction: Disrobing in a Dream

In 1126, Emperor Qinzong of Song appointed his brother Zhao Gou as the grand marshal. The following year, as the Jin army moved south, the Northern Song dynasty fell. Both Emperors Qinzong and Huizong were captured by the Jin people and taken north. Zhao subsequently ascended the throne in Nanjing, becoming the first emperor of the Southern Song dynasty. The story of "Disrobing in a Dream" takes place during this period of turbulent regime change. One day, while Zhao was engaged in a military campaign as the grand marshal, he dreamed of meeting his brother Emperor Qinzong in the palace garden. In the dream, Emperor Qinzong took off his robe and offered it to Zhao, symbolizing the transfer of power and throne to him. Just as Zhao was about to decline, he awoke from the dream. Upon hearing of this, Zhao's minister Cao Xun wrote a piece praising Zhao's brave leadership and divine mandate, prophesying a resurgence of national strength.