Imperial Architectural Drawings

In the Qing Dynasty, the construction, expansion, and interior decoration of imperial palaces, the capital city, altars, temples, imperial mausoleums, gardens, and mansions were all under the jurisdiction of the "Ministry of Works", overseen by the "Imperial Household Department", and managed by the "Construction Bureau" (Imperial Commission Construction Bureau). This bureau was composed of trusted high-ranking officials appointed by the emperor and was responsible for coordinating design institutions for various projects.

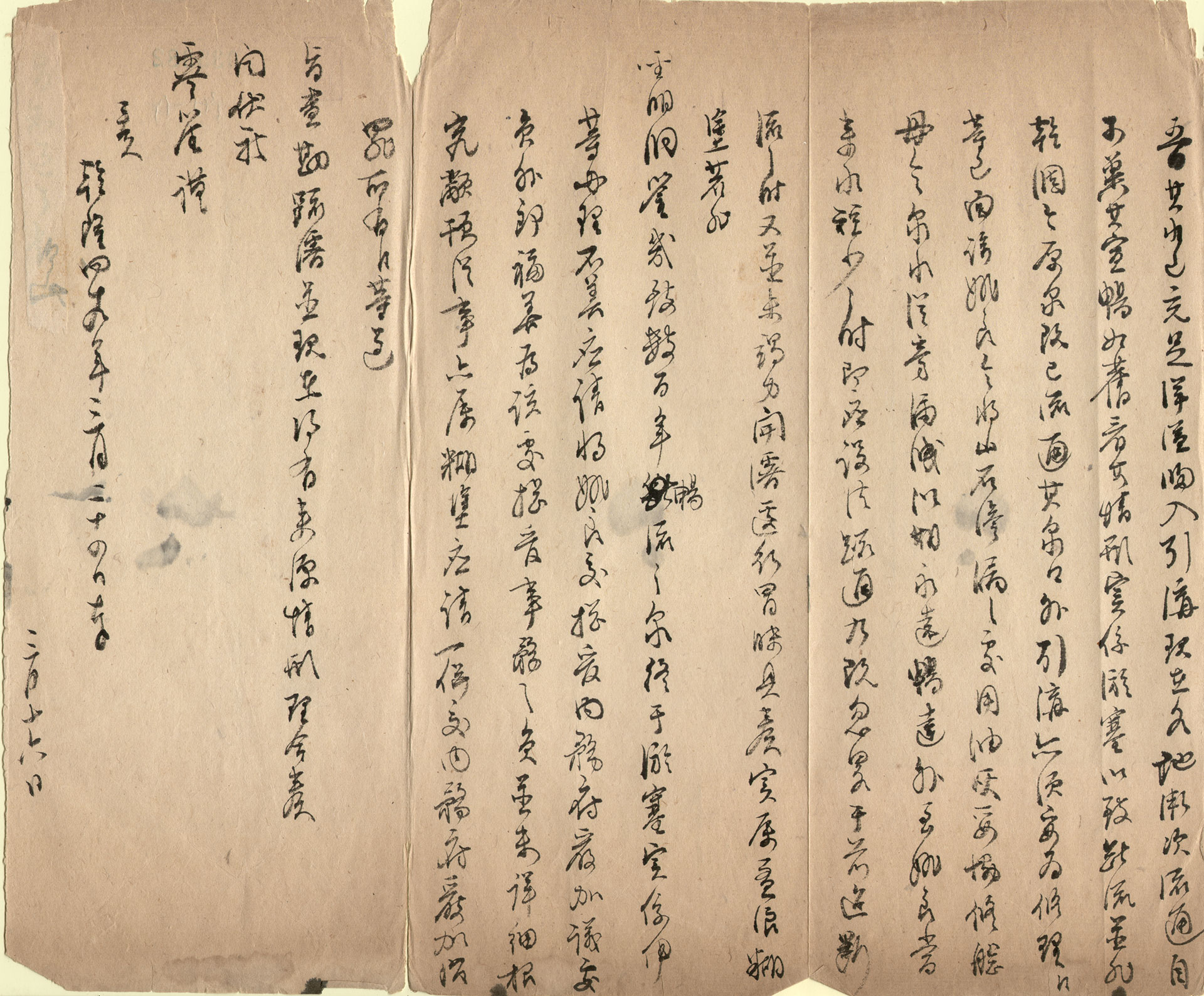

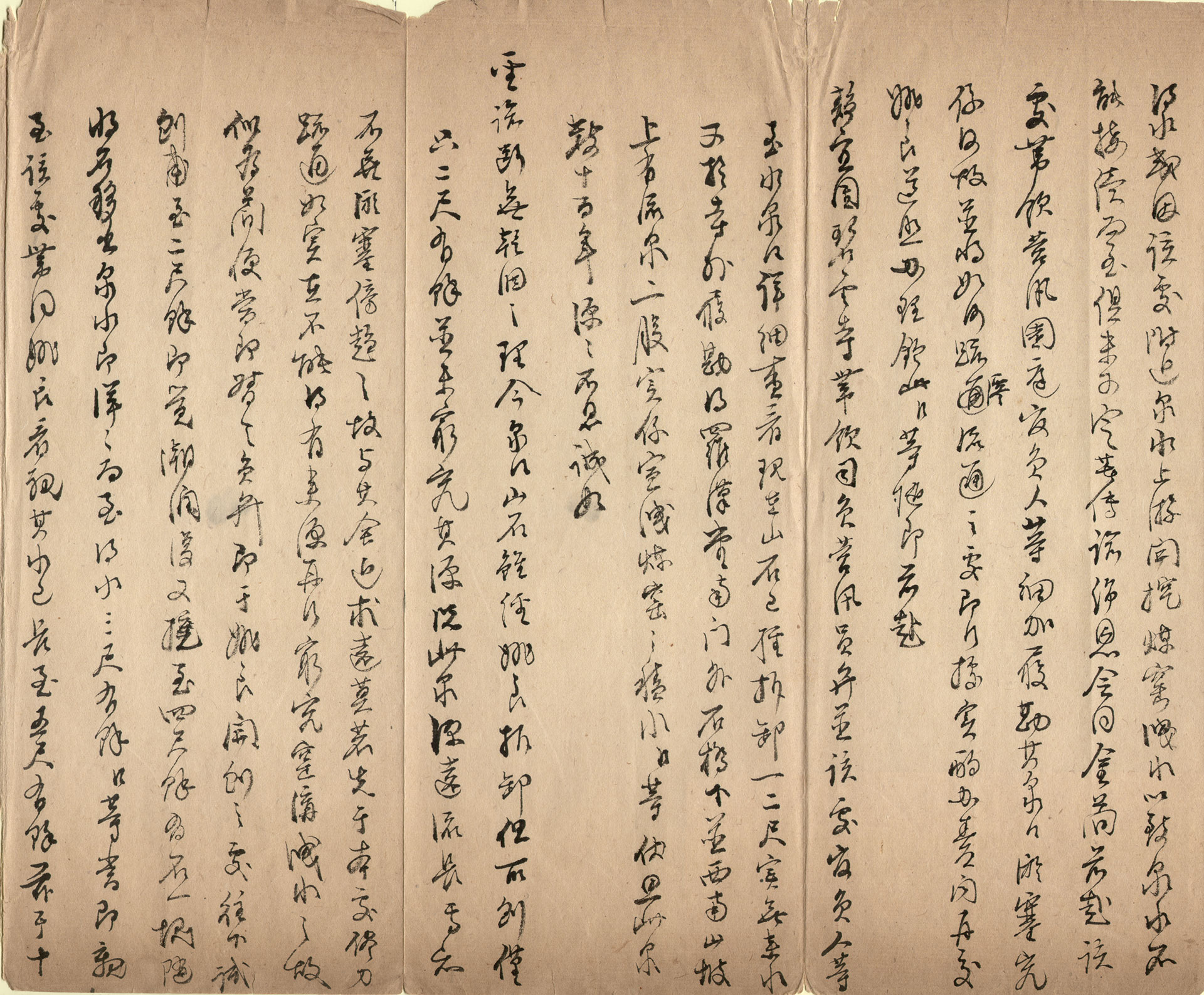

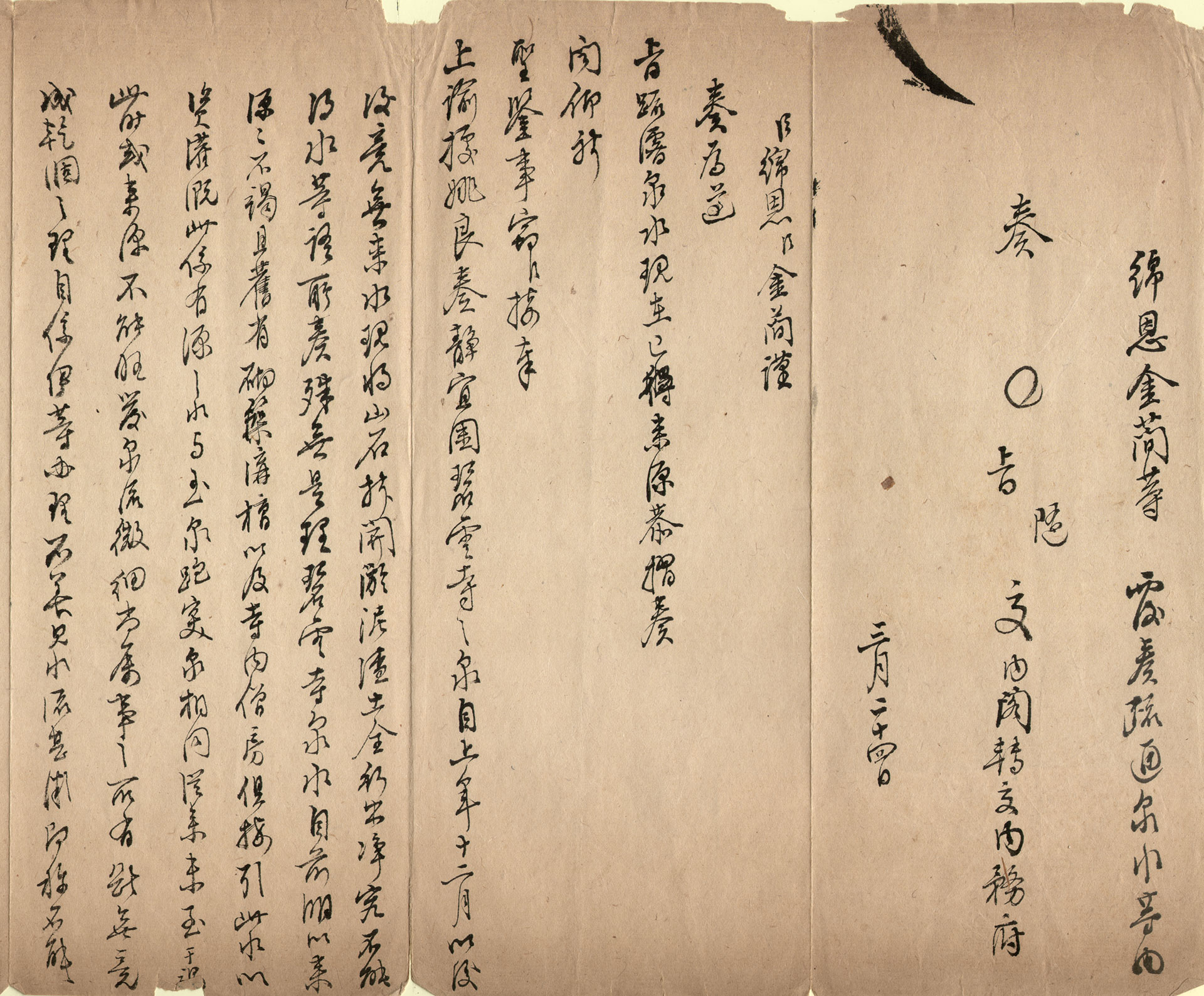

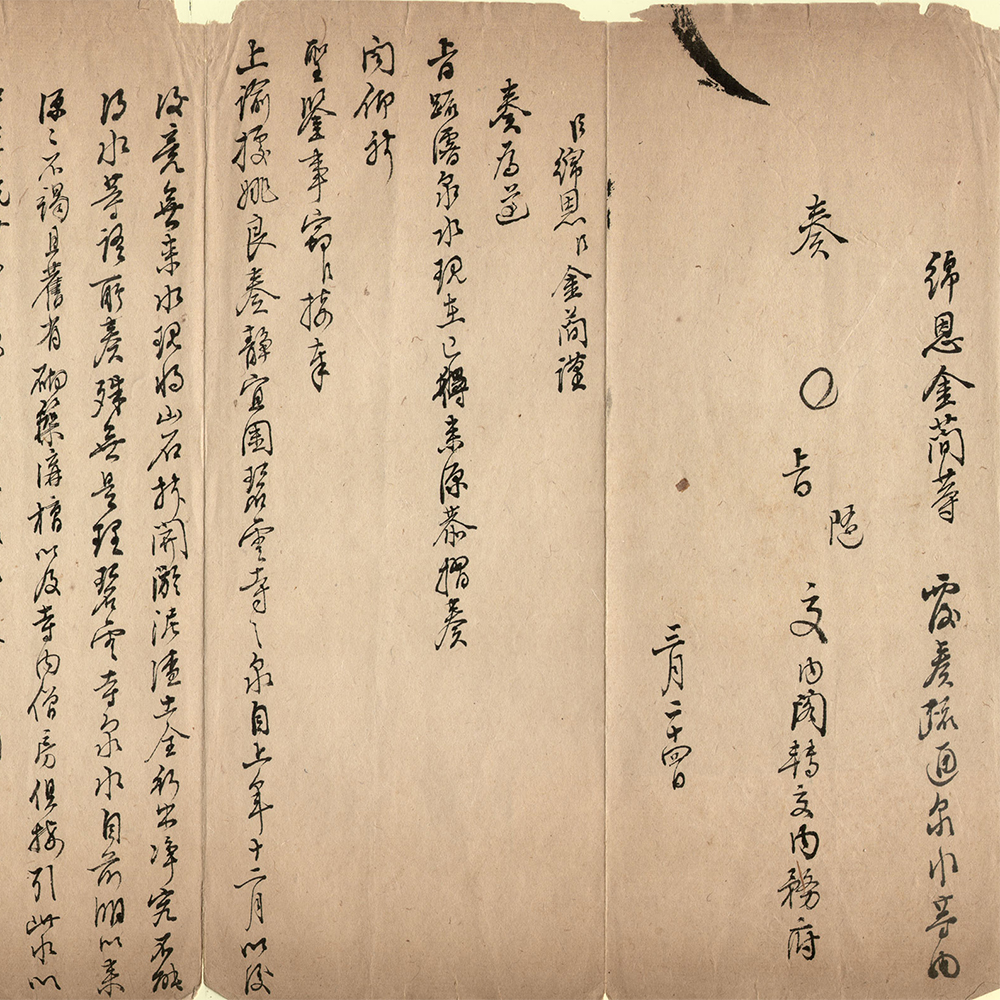

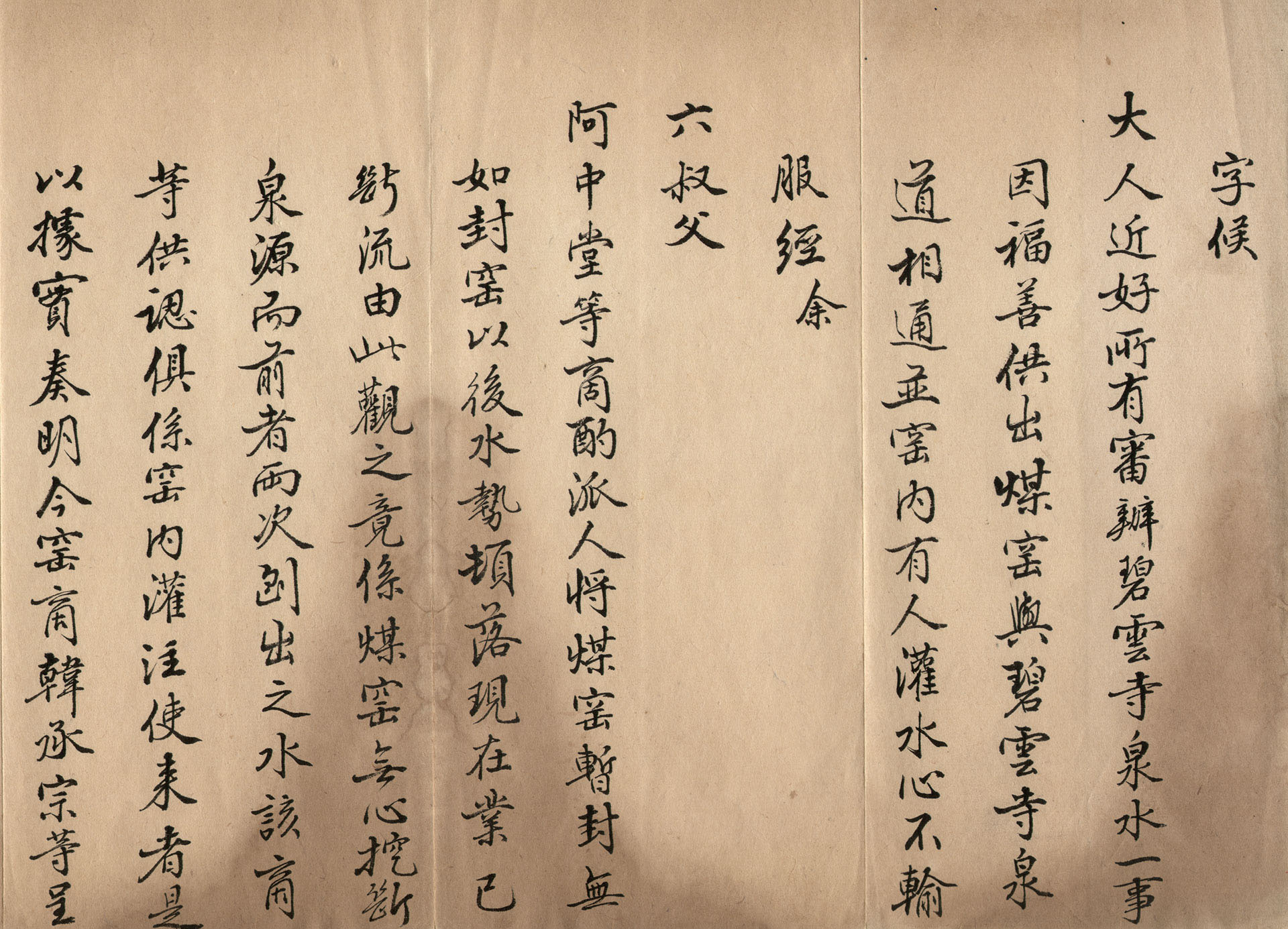

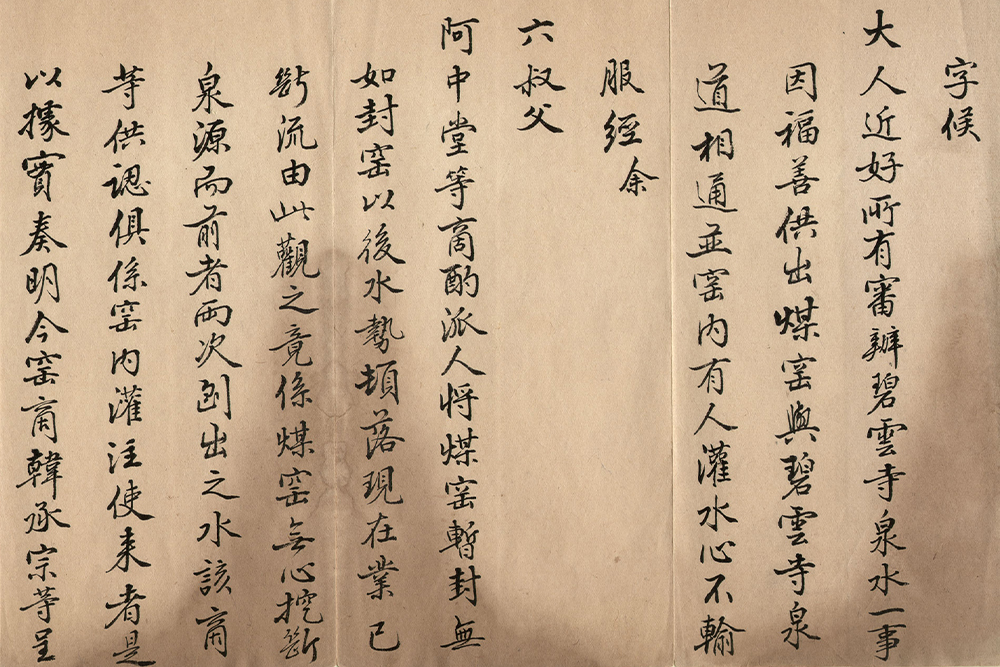

The ministers responsible for construction projects in the Qing Dynasty first conducted design planning, surveyed and measured the spaces, and drew draft sketches. Through multiple revisions, from rough drafts to detailed drawings, they ultimately created the "presentation model" for submission to the emperor. The ministers and presenting the detailed planning through drawings also submitted explanatory reports. When necessary, they would create architectural models, referred to as " Tang yang " or "stamped models," to provide the emperor with a comprehensive understanding of the project.

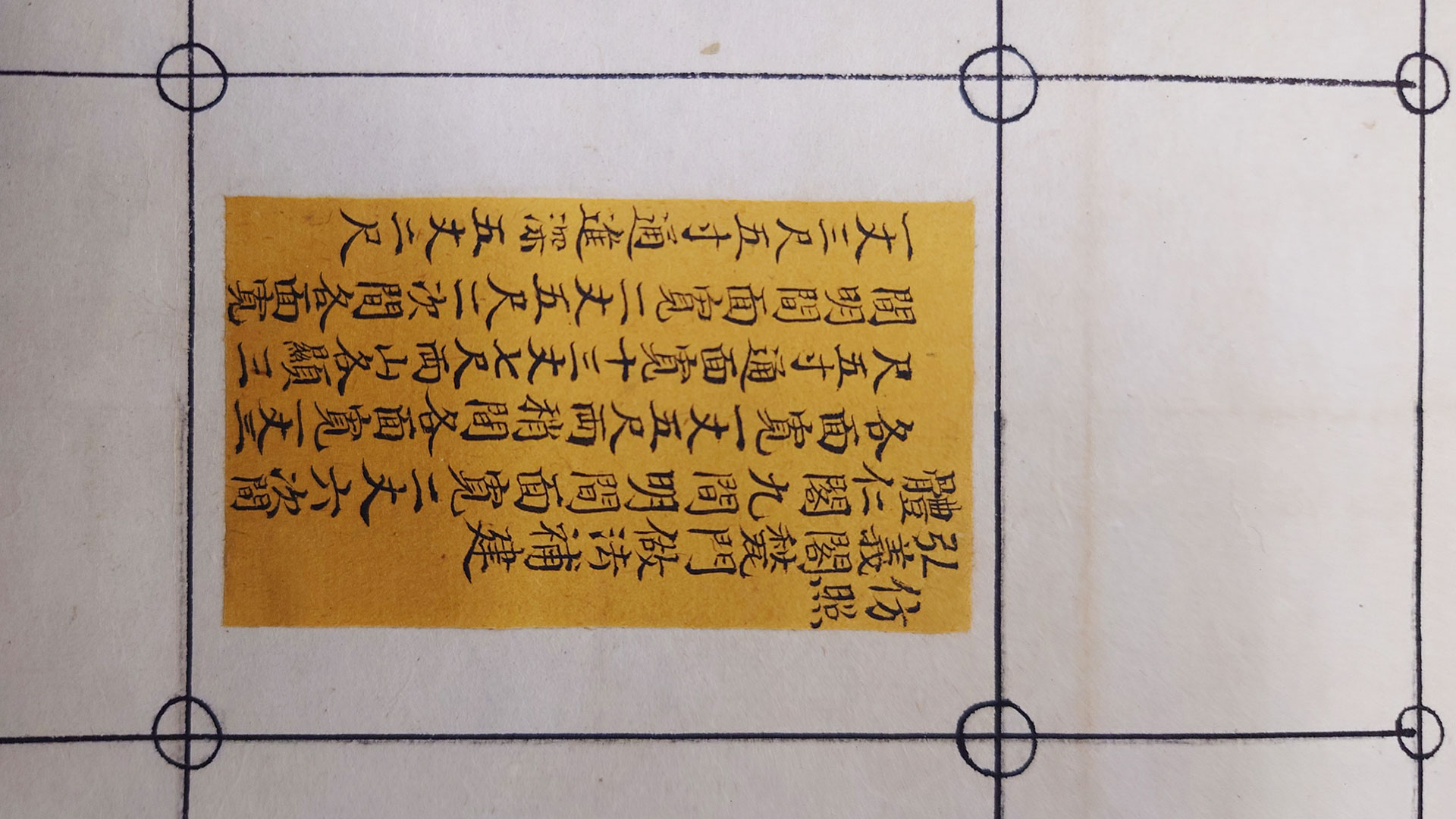

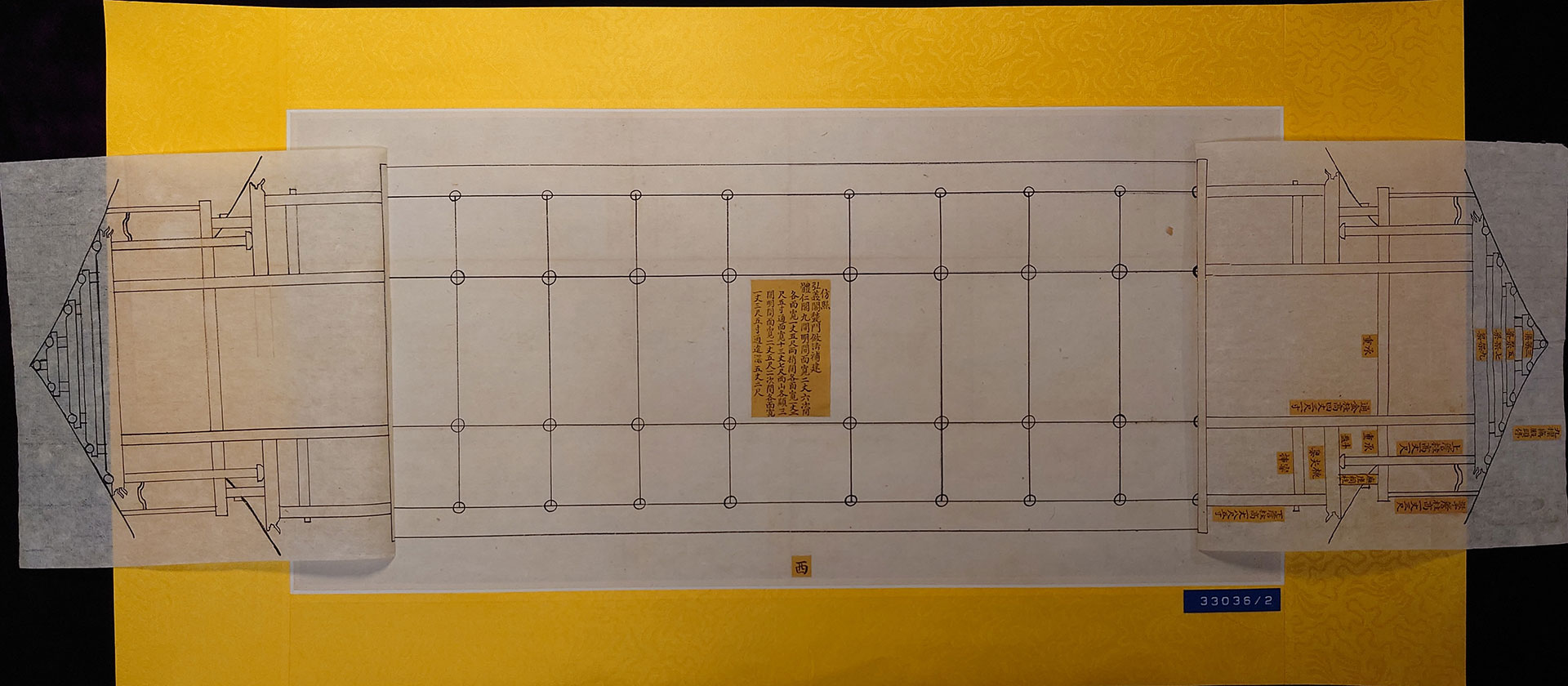

In these "presentation model drawings", various colored strips of paper, typically yellow and red, were often affixed, containing detailed explanations of the project known as "drawing annotations". After the emperor reviewed the presentation model, if there were any suggested revisions, it would be returned for corrections. In some cases, the emperor would provide instructions to keep the records for his further review before submitting them to the Grand Council for archival purposes. Our institution houses these various forms of presentation models and architectural drawings that were reviewed by the emperor. In this section, we will showcase representative documents from three major categories: "Palace and Garden Construction Drawings", "Temple Construction Drawings", and "Mausoleum Construction Drawings".

Palace and Garden Construction Drawings

The Manchu people rose to prominence in the Northeast and took over China in the 17th century. They maintained the old management practices of Shengjing (modern-day Shenyang)—briefly the capital of China in the Qing dynasty—and inherited the original Beijing imperial family buildings from the Ming dynasty. Later, they converted many Ming dynasty clan lands into new imperial regime territories. Under the management of Emperor Kangxi as well as his son (Emperors Yongzheng) and grandson (Emperor Qianlong), imperial Qing palaces, the Three Hills and Five Gardens, and the Temporary Imperial Residence Resort underwent constant expansions and renovations. These imperial gardens had been around for hundreds of years. By studying related architectural drawings in the Qing court collection, visitors can enrich their understanding of traditional Qing architecture.

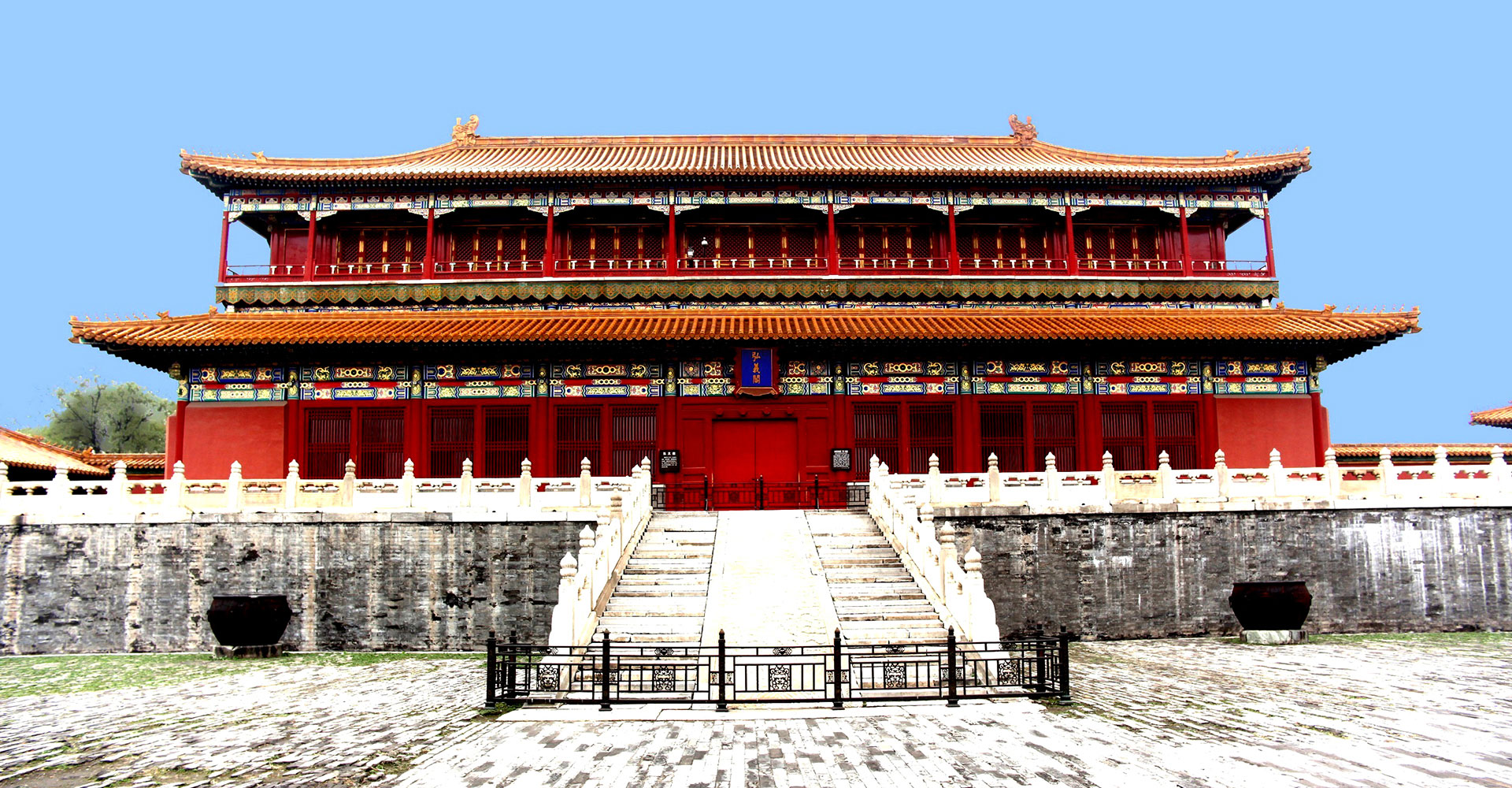

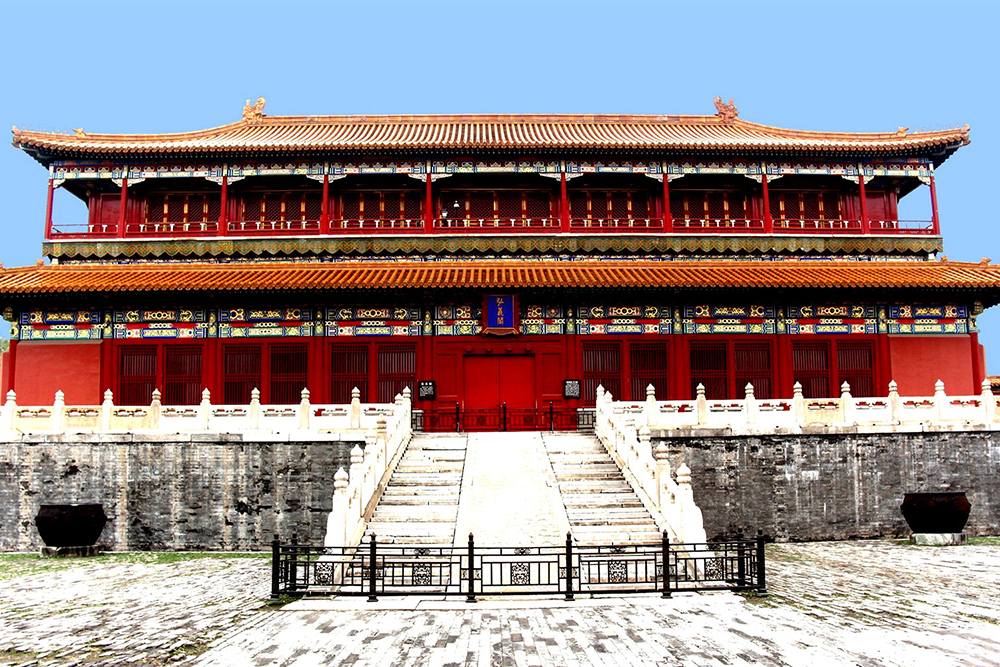

Civil and military towers were traditional Chinese architecture. Civil towers, also called “bell towers,” were located on the east side of a region, whereas military towers, also called “drum towers,” were located on the west side of the region. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, civil and military towers were constructed on the east and west sides of the Gate of Supreme Harmony outside the Forbidden City, respectively. Regarding the names of the two buildings, they evolved from the “Belvedere of Civil Achievements” and “Belvedere of Military Achievements” in the Ming dynasty to the “Belvedere of Embodying Benevolence” and “Belvedere of Spreading Righteousness,” respectively, in the Qing dynasty.

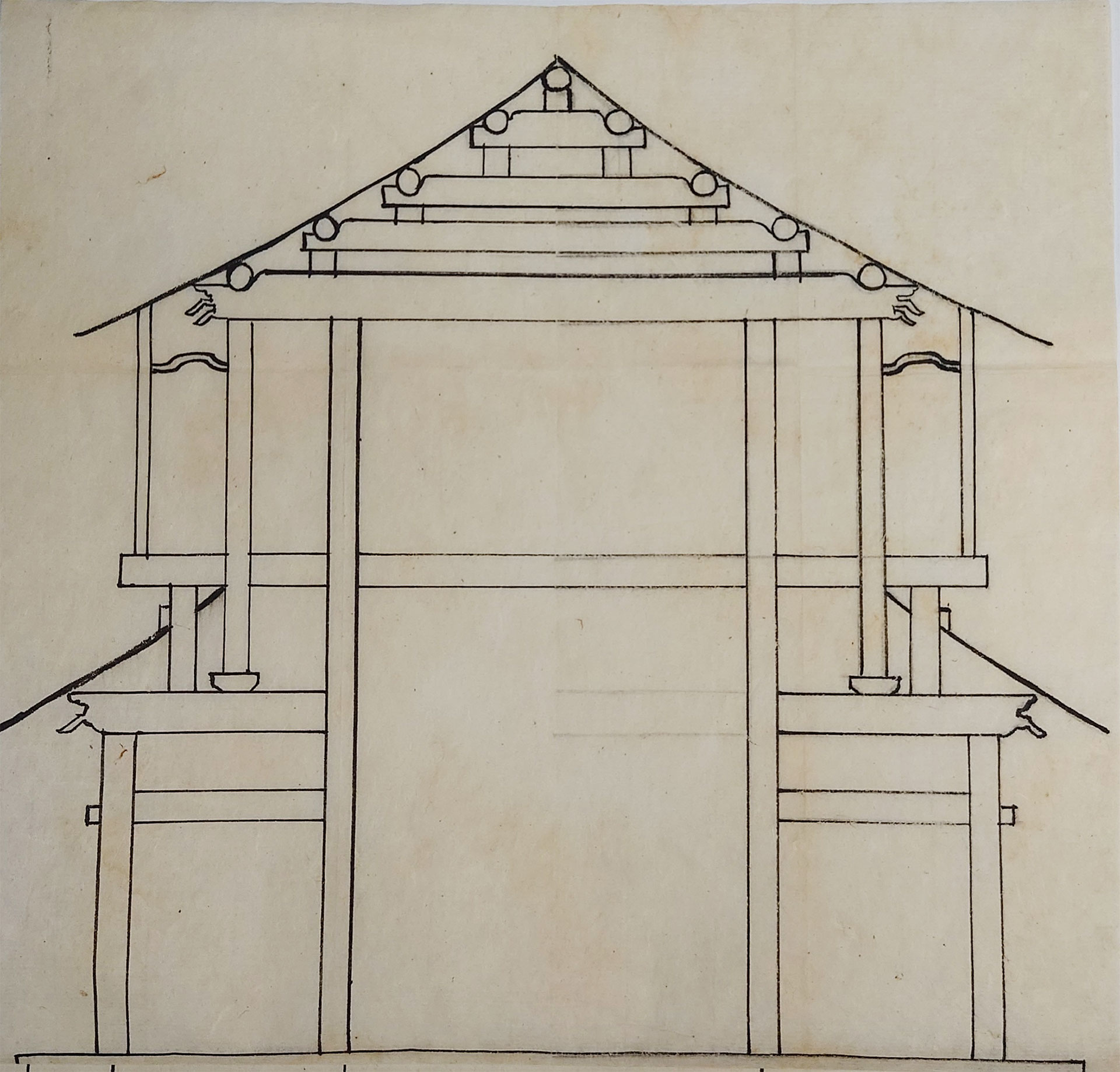

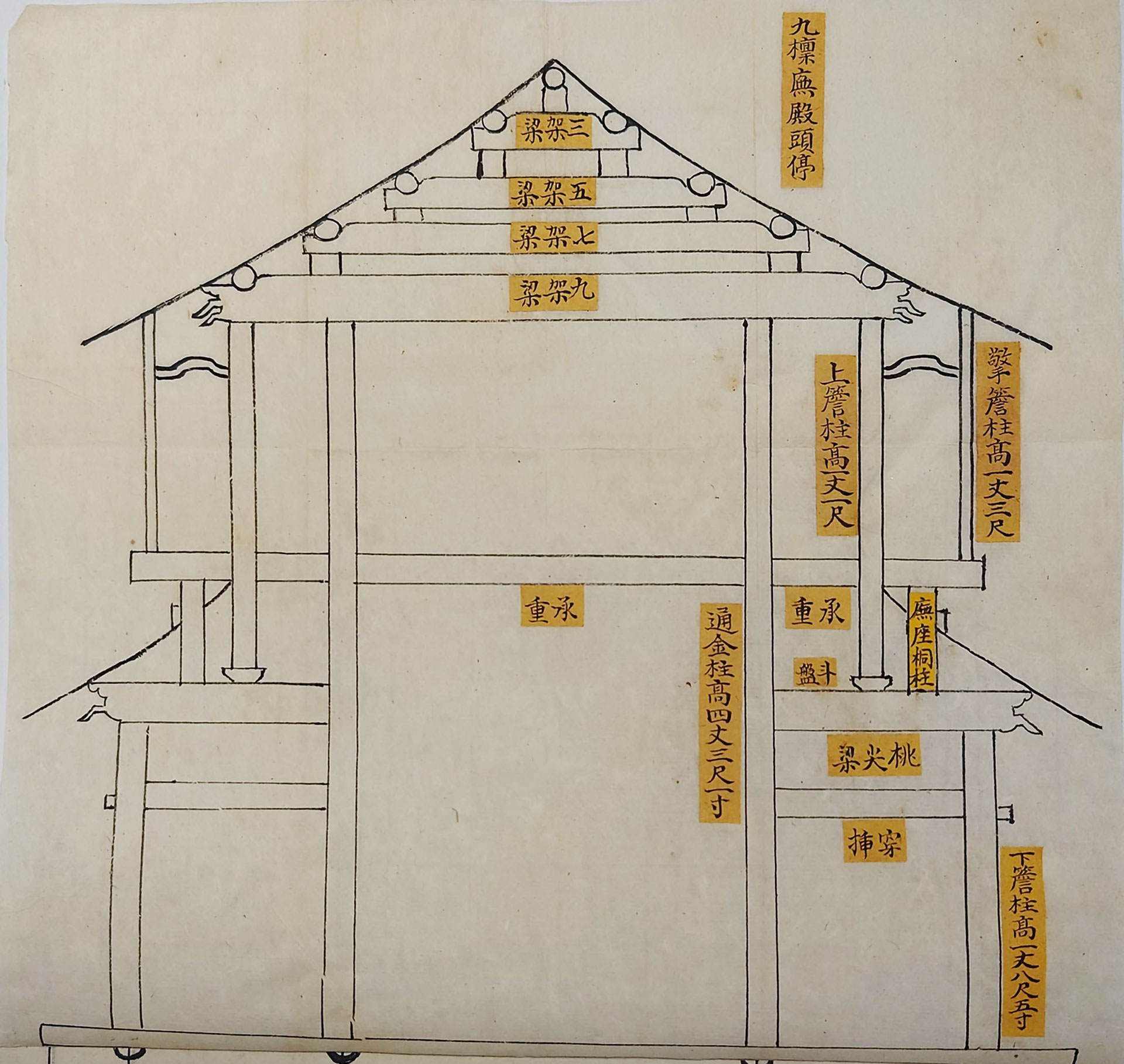

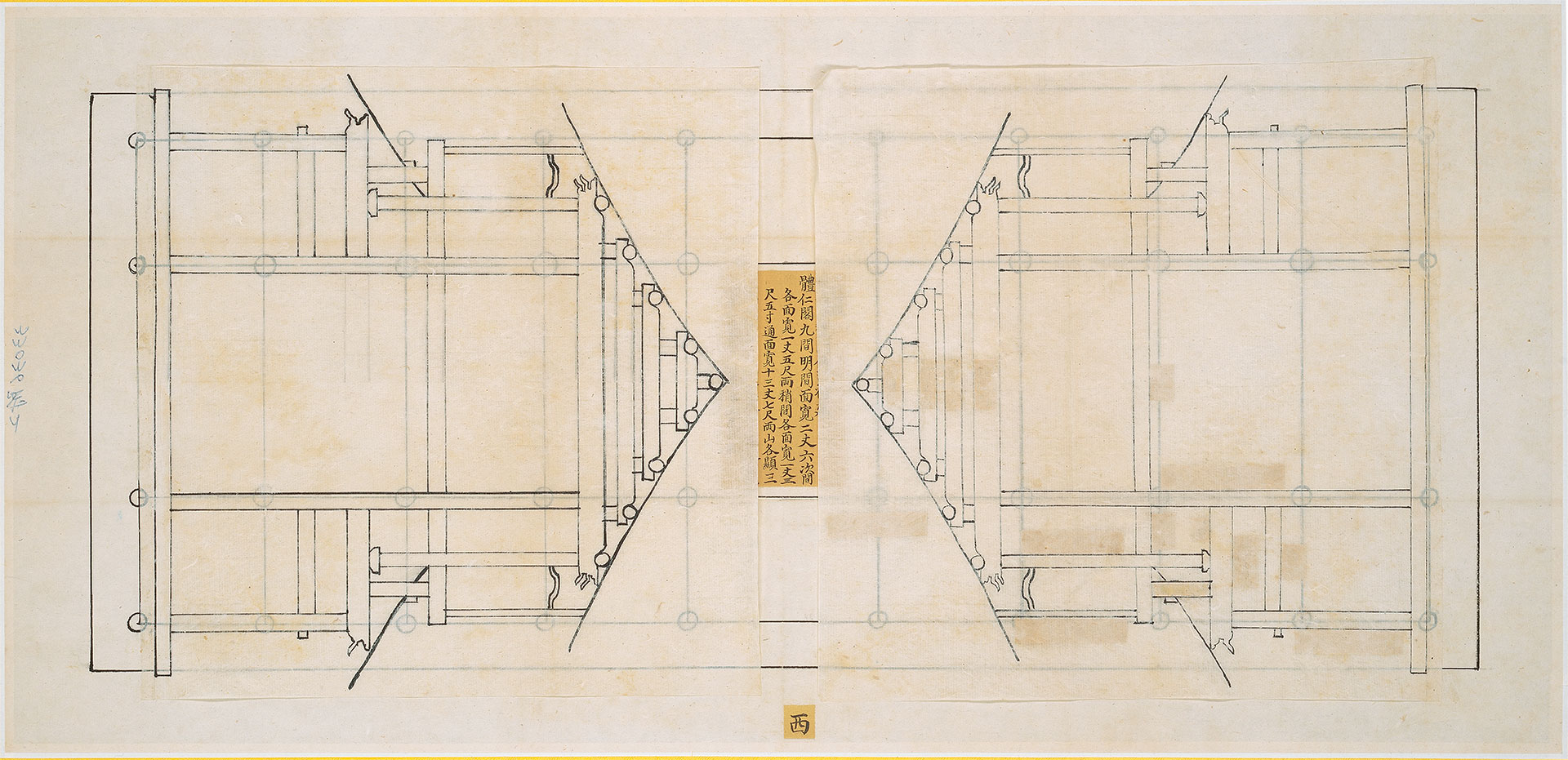

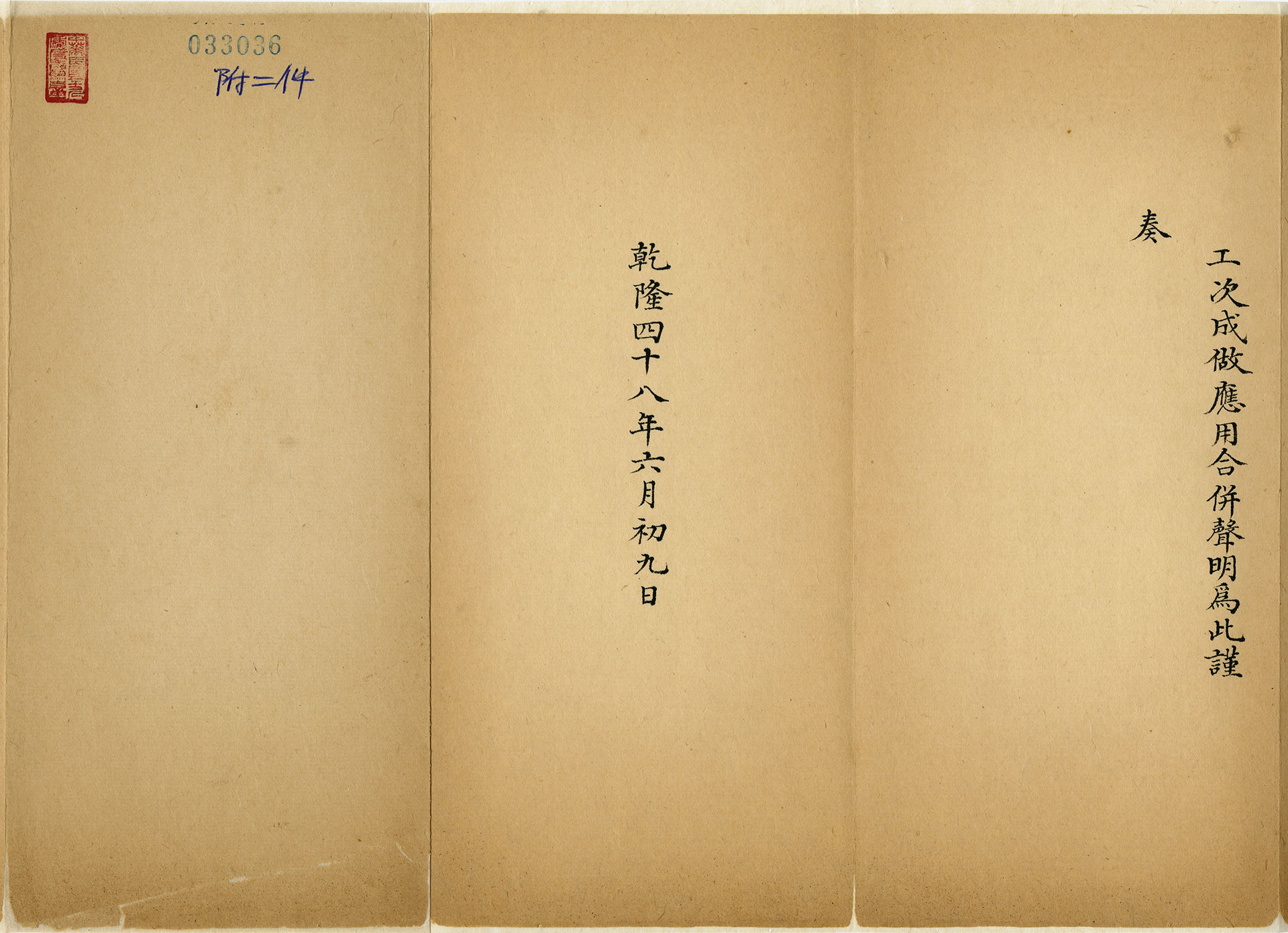

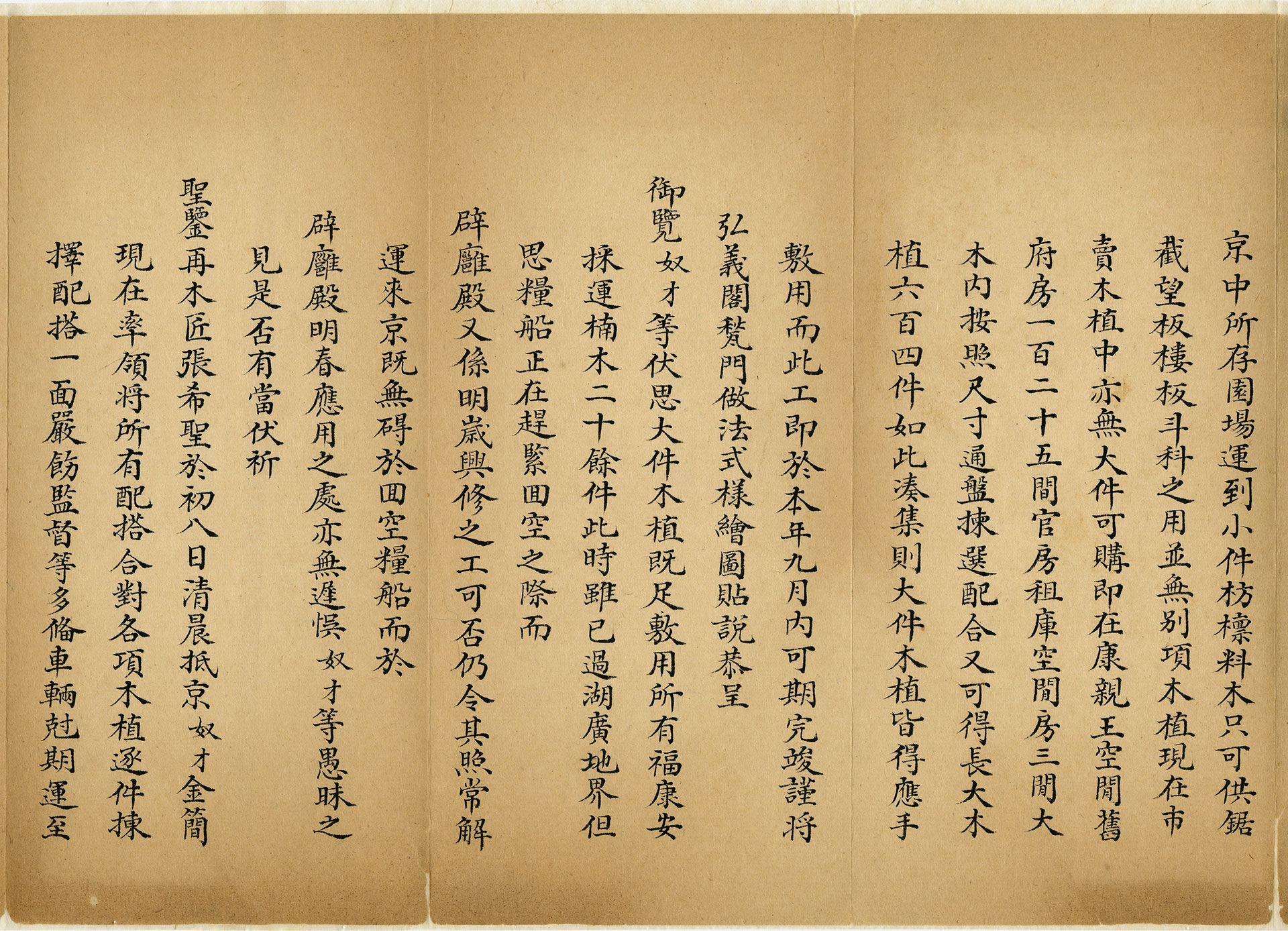

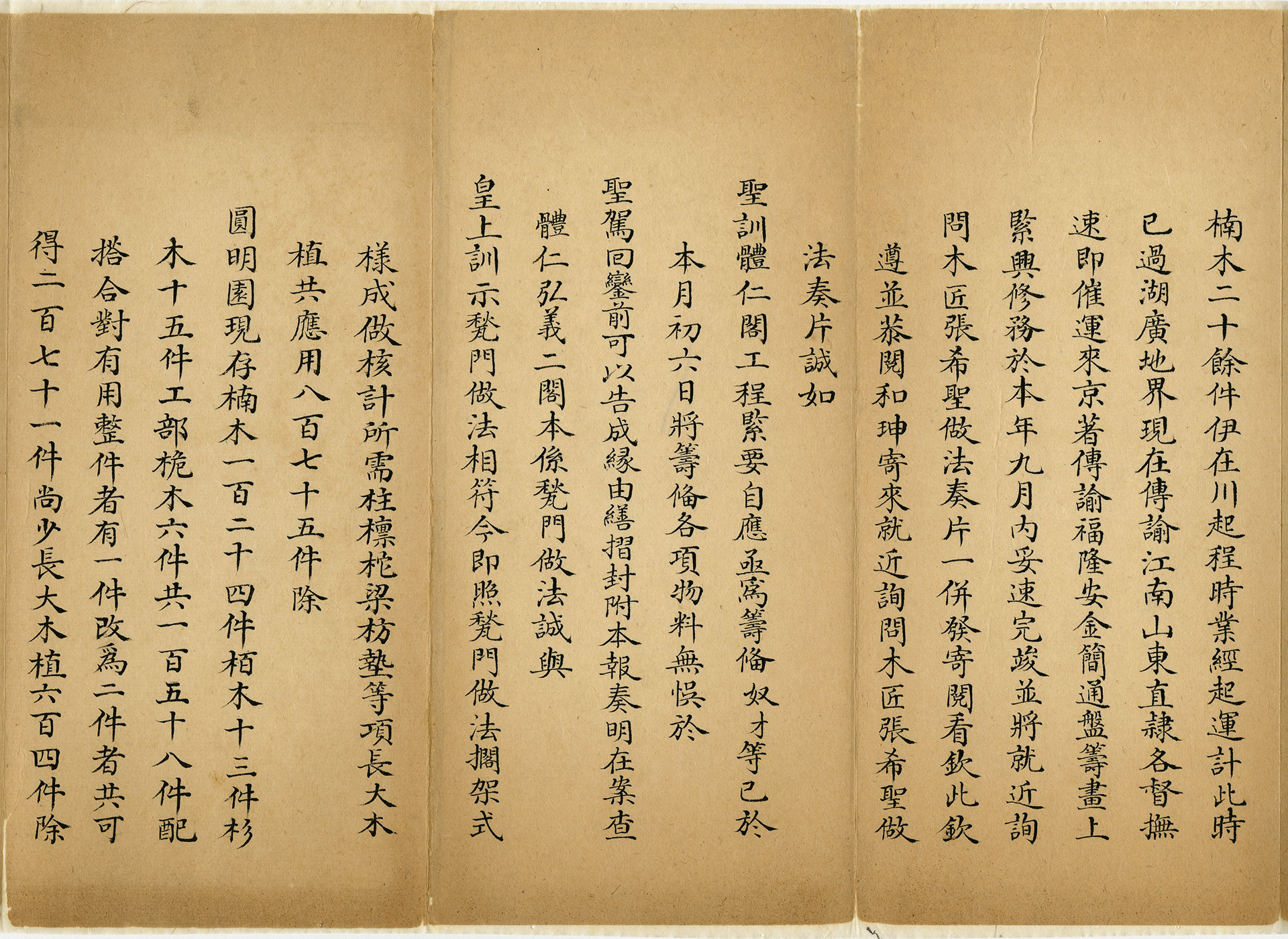

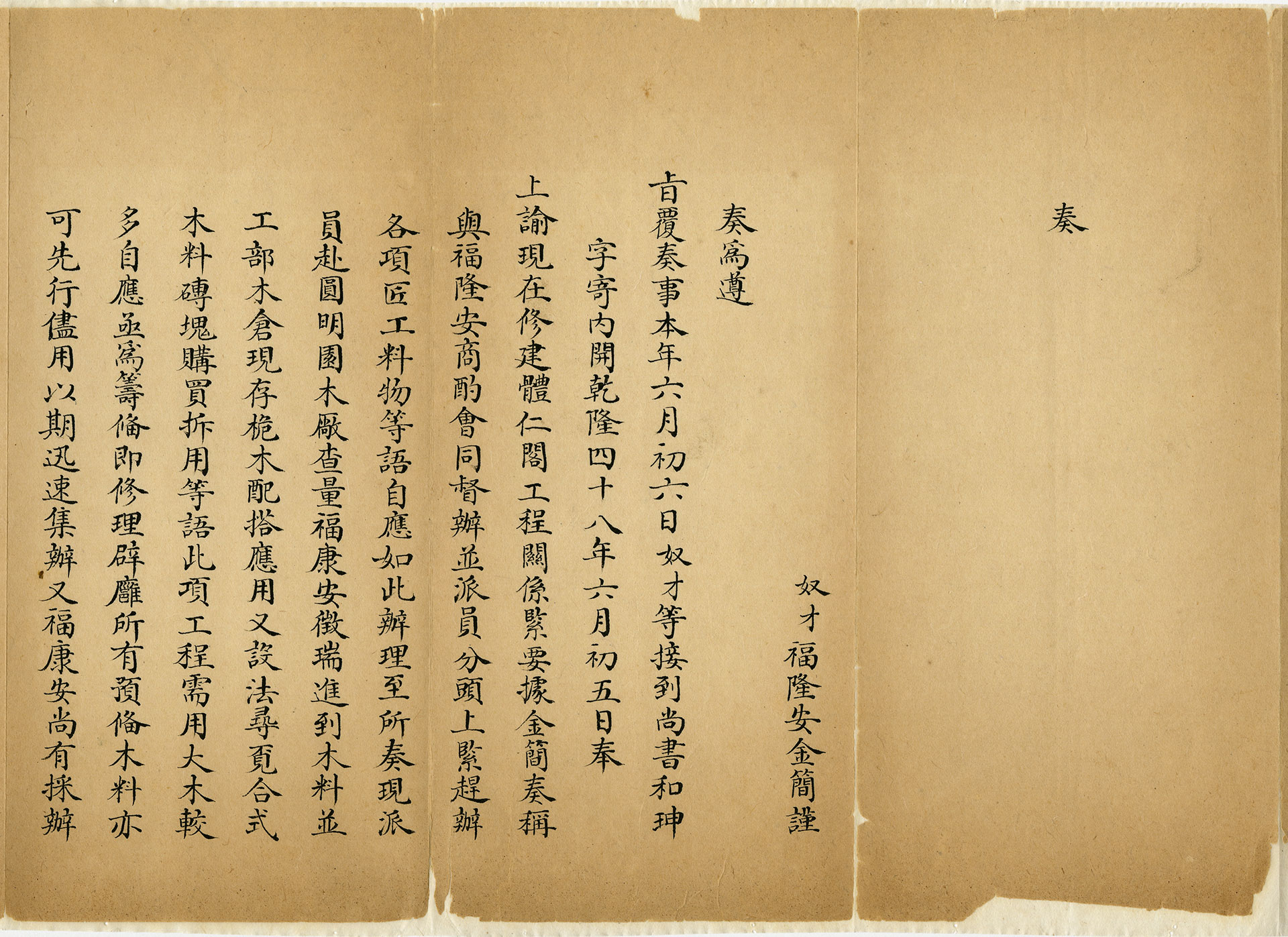

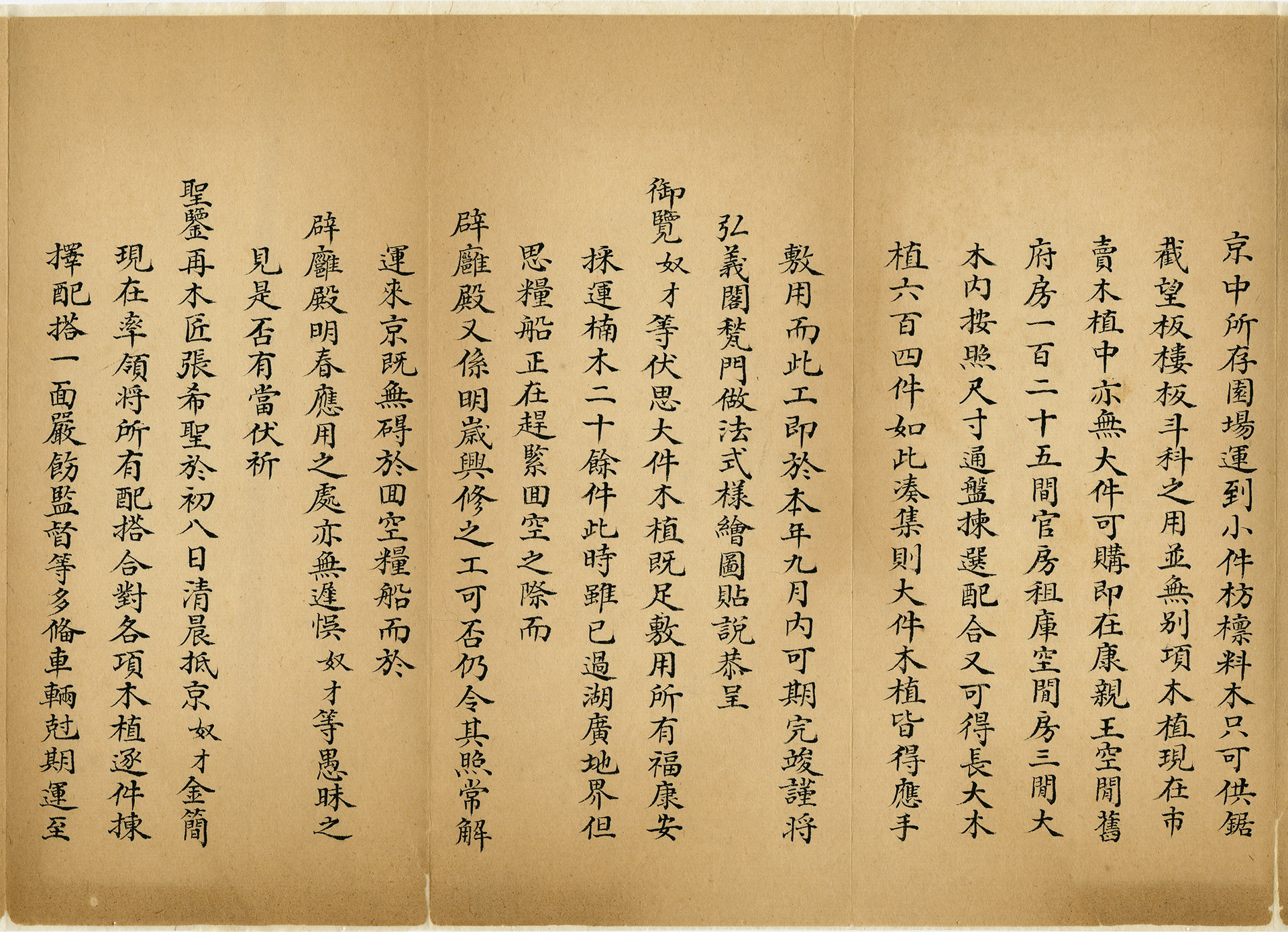

During a thunderstorm in the evening of June 6, 1783, lightning struck and lit the Belvedere of Embodying Benevolence on fire. Despite the efforts made to extinguish the fire, it persisted until the following morning. Upon hearing the news via a palace memorial, Emperor Qinglong, who was staying at the Summer Resort at this time, immediately ordered that Fu Long’an (1746-1784), the minister of the Ministry of Works, reconstruct the Belvedere of Embodying Benevolence based on the design of the Belvedere of Spreading Righteousness, and that he complete the reconstruction prior to the emperor’s return in September. To ensure that the reconstruction was completed on schedule, the emperor dispatched Zhang Xisheng, a famous carpenter working for the imperial family, to assist in the operation. The “Drawings of the Methods for Building the Belvedere of Spreading Righteousness Brick Gates” shows Fu Long’an and others rushing to the disaster site, performing surveys, and referencing the engineering drawings (that were drawn according to the specification of the Belvedere of Spreading Righteousness) submitted to the emperor to review. The palace memorial architectural drawings included the 2D and 3D floor plans of the Belvedere of Spreading Righteousness, which had yellow tags that showed the number of beams and columns, the building dimensions, and the construction methods.

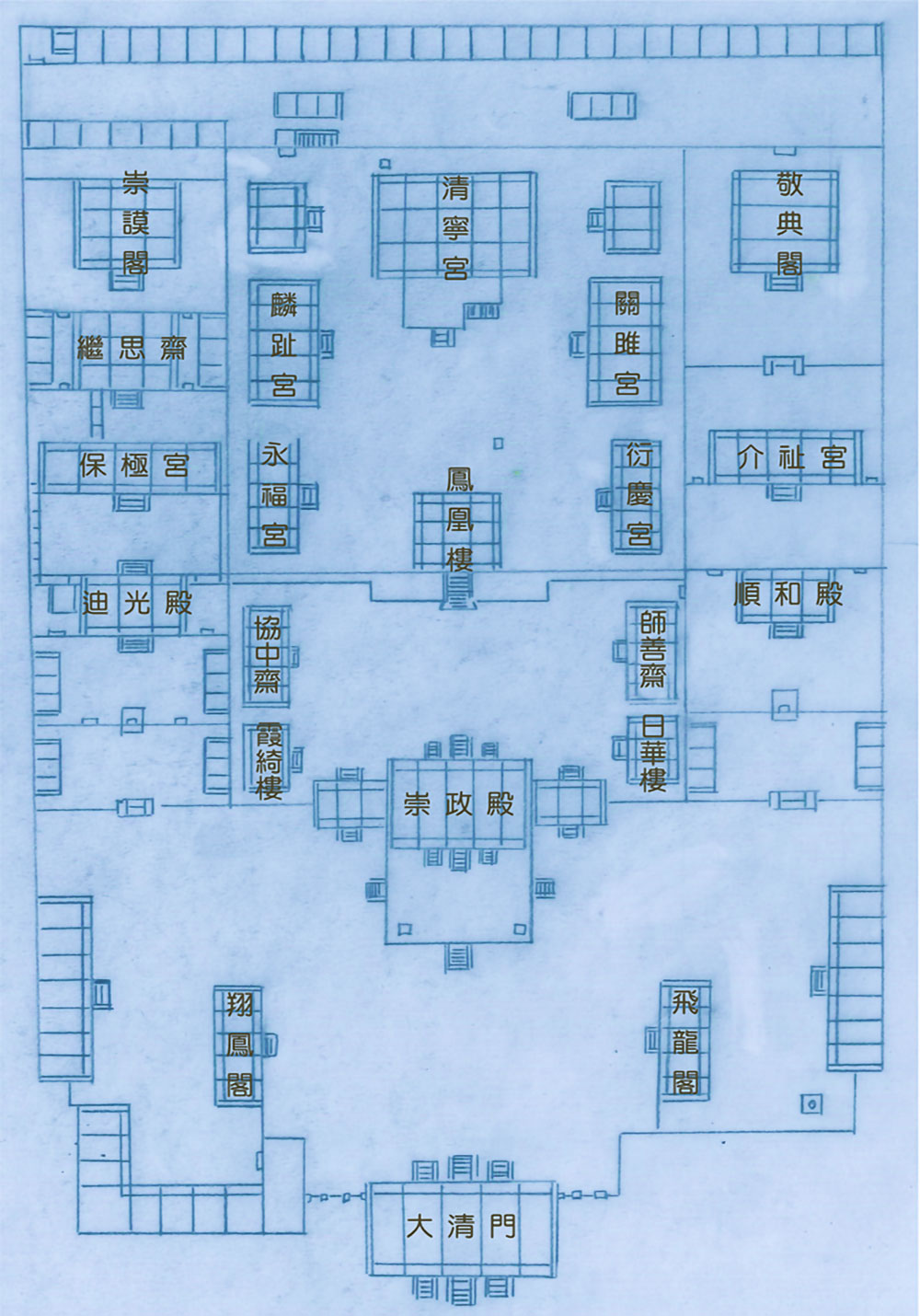

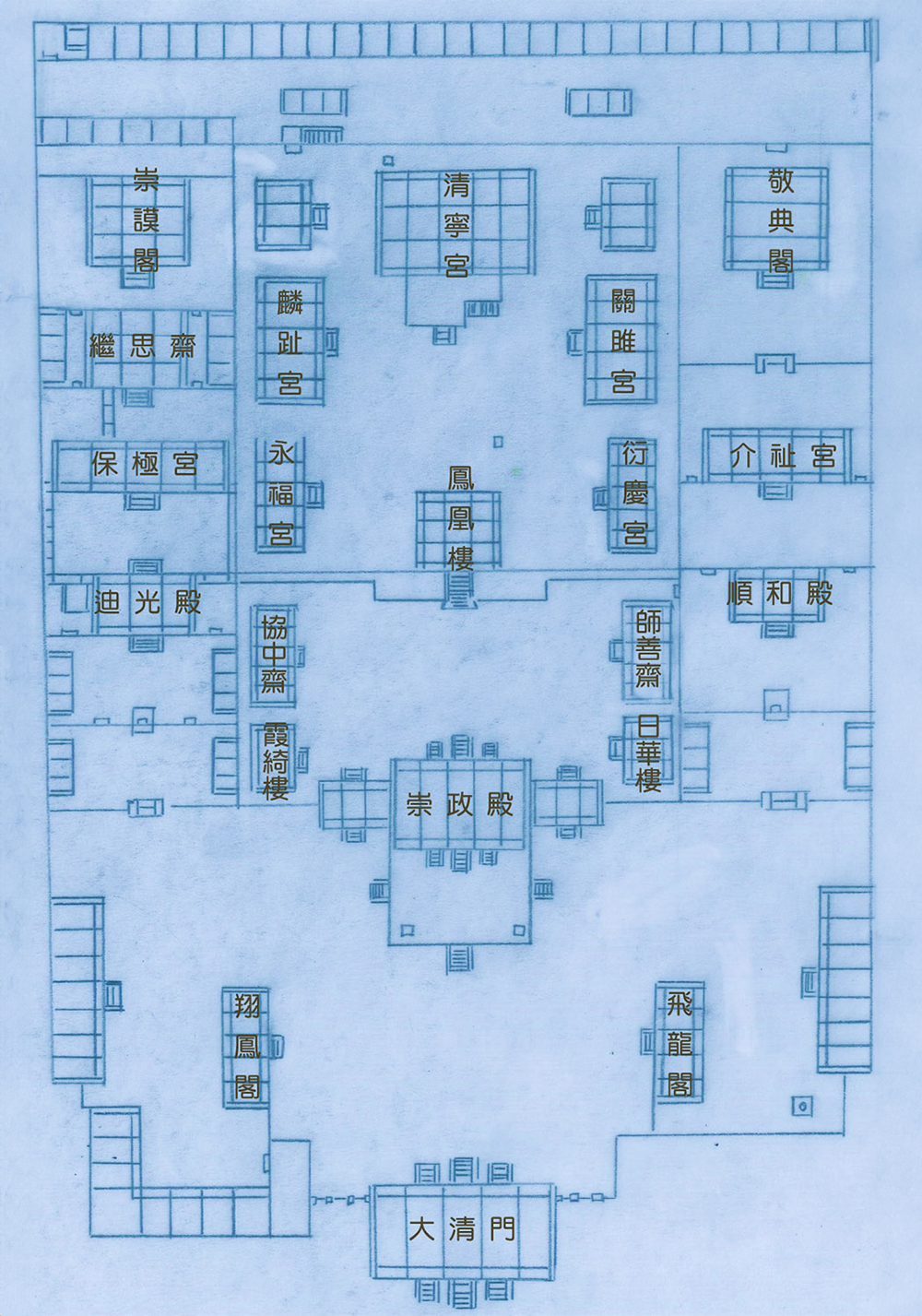

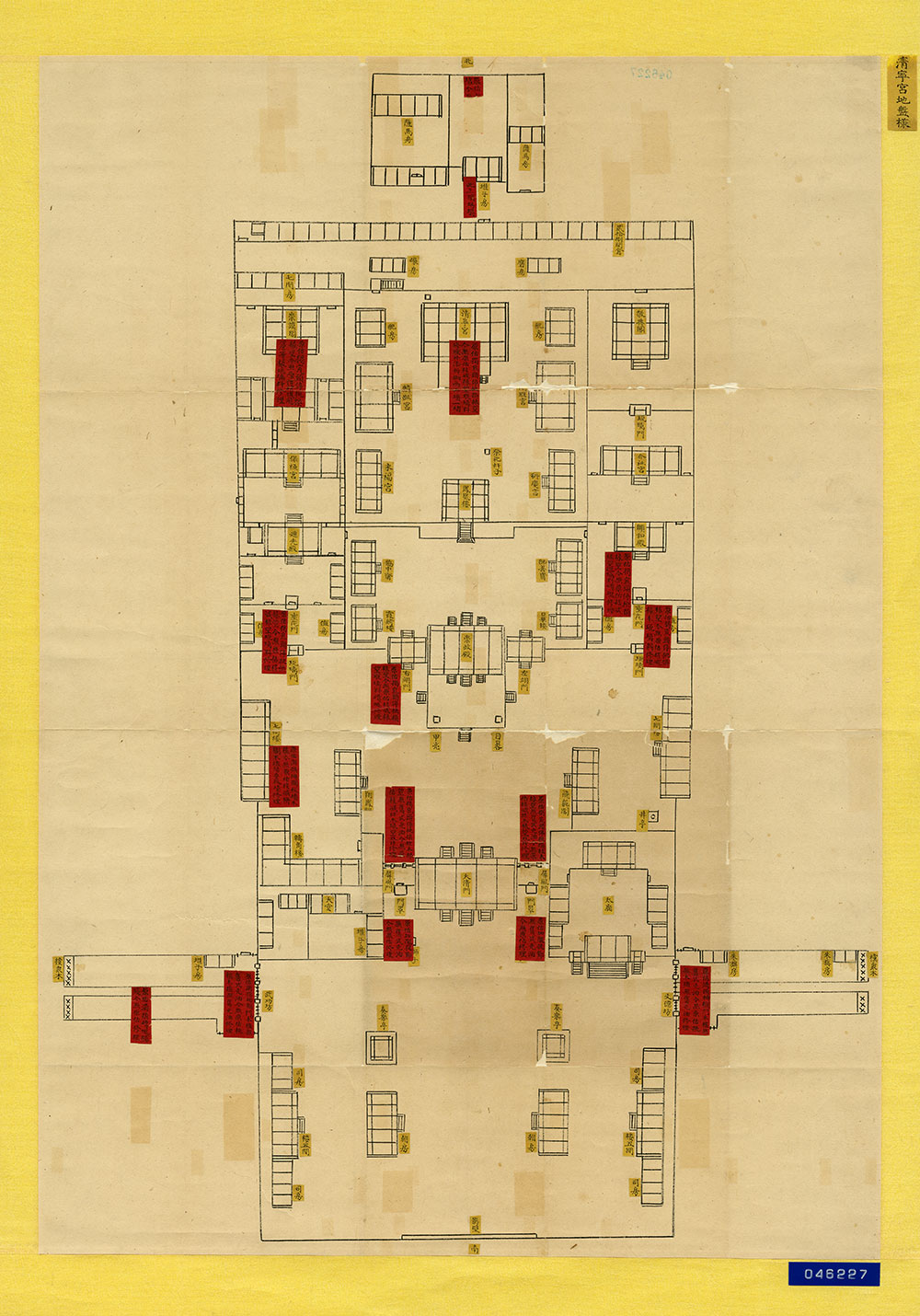

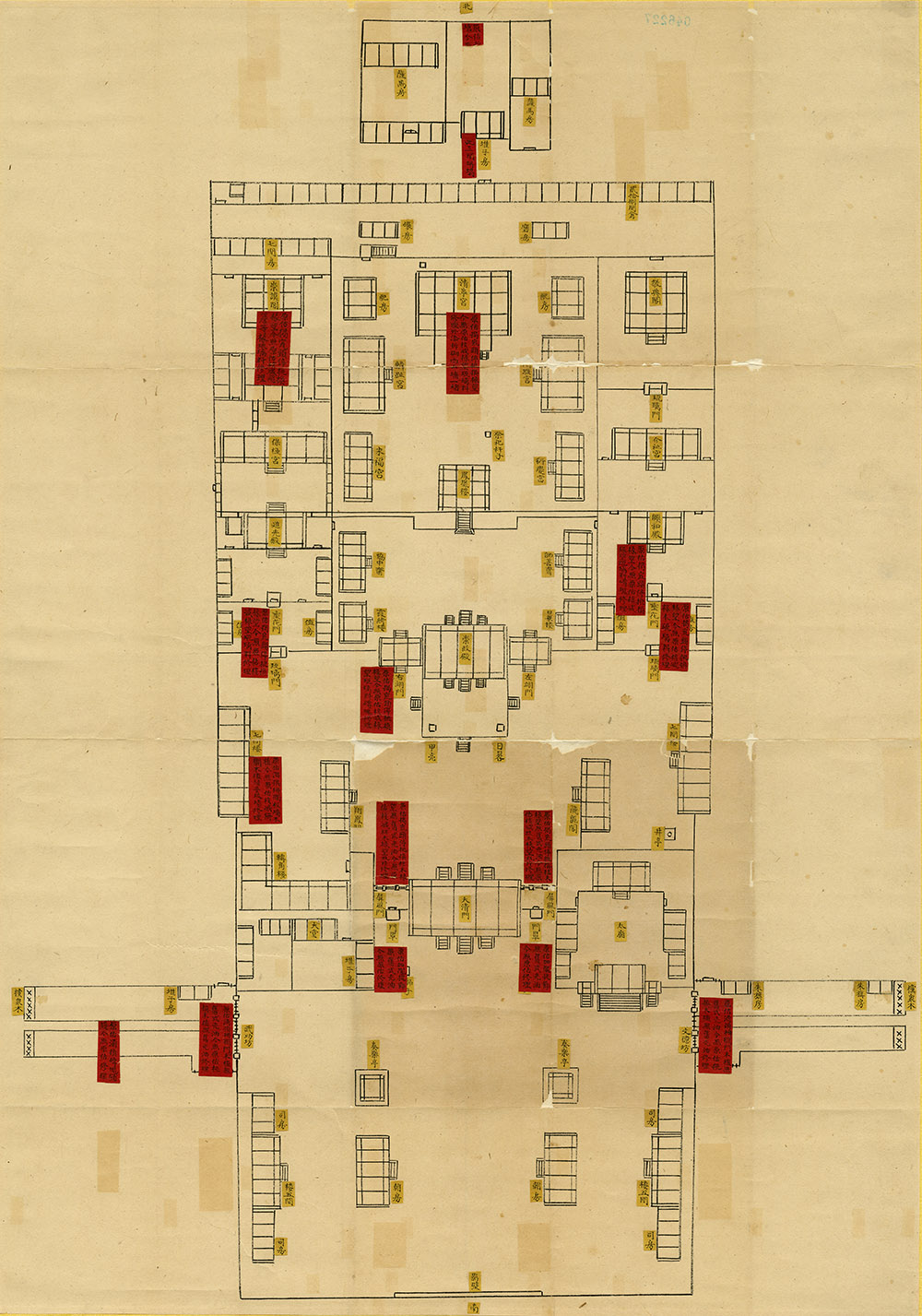

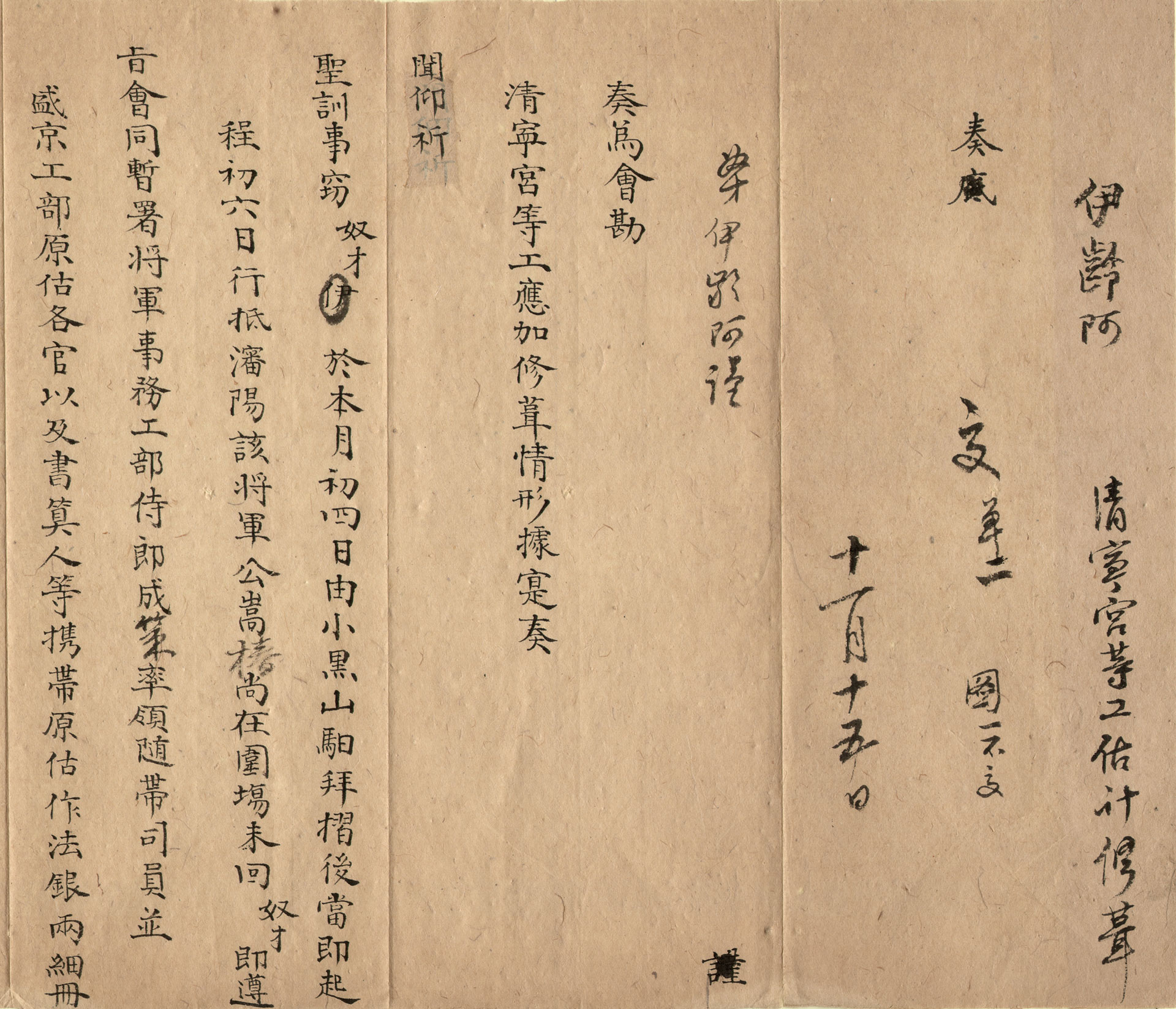

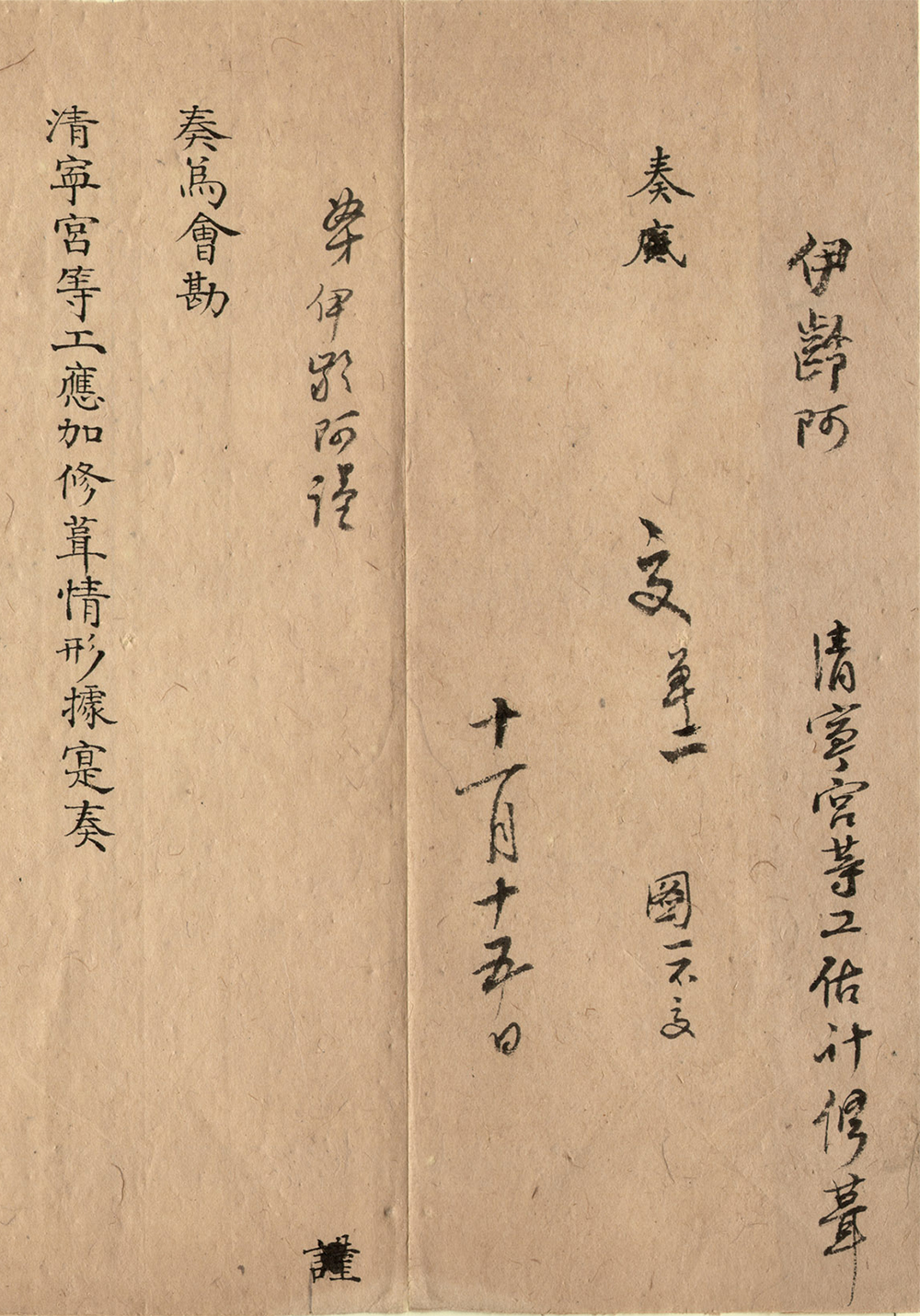

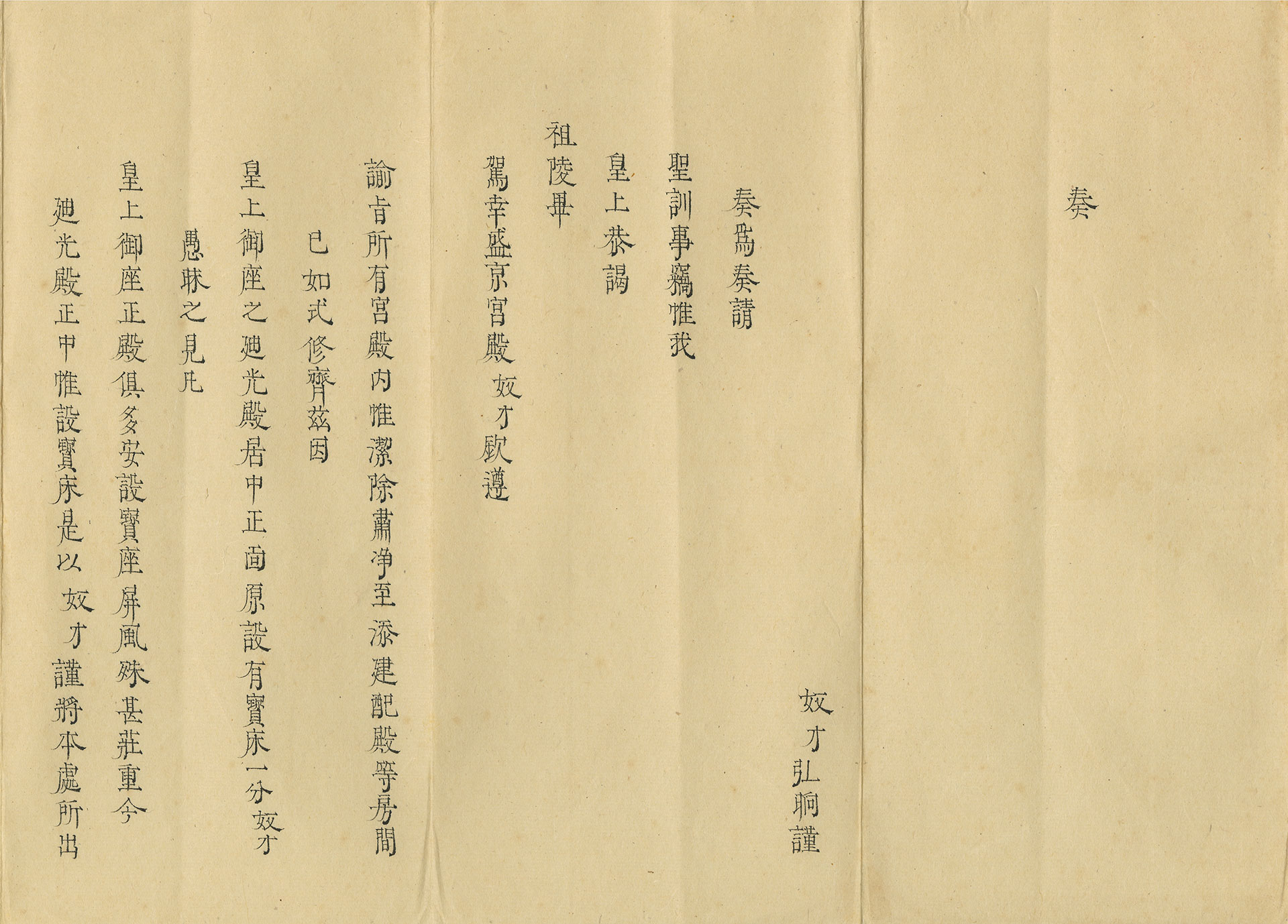

The artifact displayed here is a floor plan proposed by Ilingga (?-1795), the steward of the Imperial Household Department, regarding the maintenance of the Qingning Palace (in Shengjing) after inspecting its surrounding in November 1790. The Qingning Palace, built during the Qing dynasty when Emperor Taizong of Qing came to the throne, was used as the living room for emperors and empresses. Later, it became an important location where god-worshipping activities were held when Qing emperors visited east (staying at Shengjing temporarily) to pay homage to their ancestors in mausoleums.

In September 1790, Song Chun (1724-1795), the General of Shengjing, reported to the emperor that the area surrounding the Qingning Palace was in disrepair and leaked water everywhere after heavy rains. Emperor Qianlong thus ordered that Ilingga rush to investigate the matter. Ilingga subsequently proposed 12 areas that were in urgent need of repair and drew a floor plan. He pasted yellow tags labeling the names of the buildings, and red tags explaining his repair suggestions.

Located in Fragrant Hill, Beijing, the Jingyi Garden was a location cherished and frequently visited by Qing emperors during their outings in the summer and fall. During Emperor Kangxi’s reign, a temporary dwelling place was built for him in Fragrant Hill. The dwelling was further expanded during Emperors Yongzheng and Qianlong’s reigns, becoming a famous imperial family garden in the Qing dynasty. The Biyun Temple in Fragrant Hill was also renowned. In fact, it was used as a temporary resting place for the coffin of Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925) after his passing in 1925.

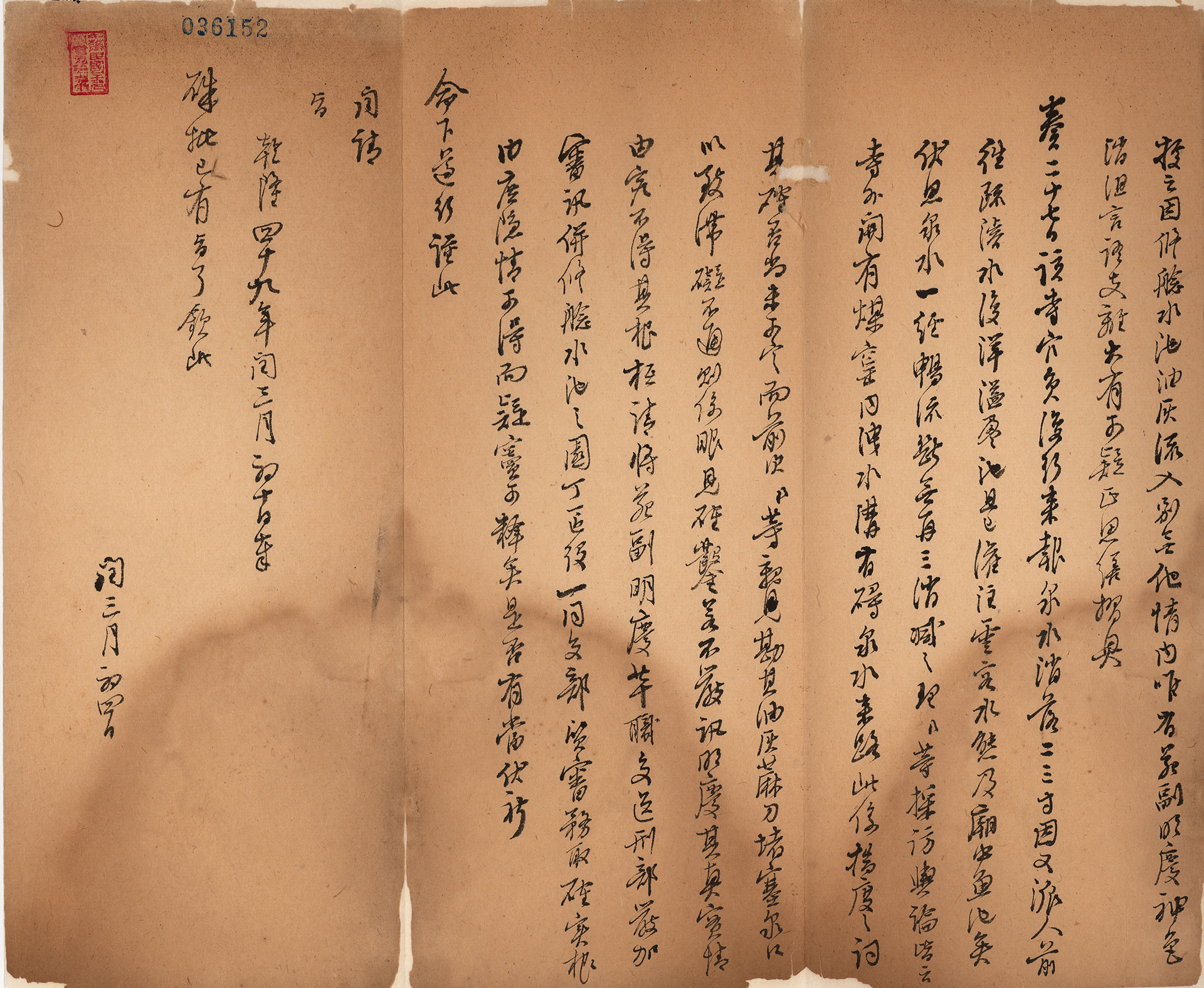

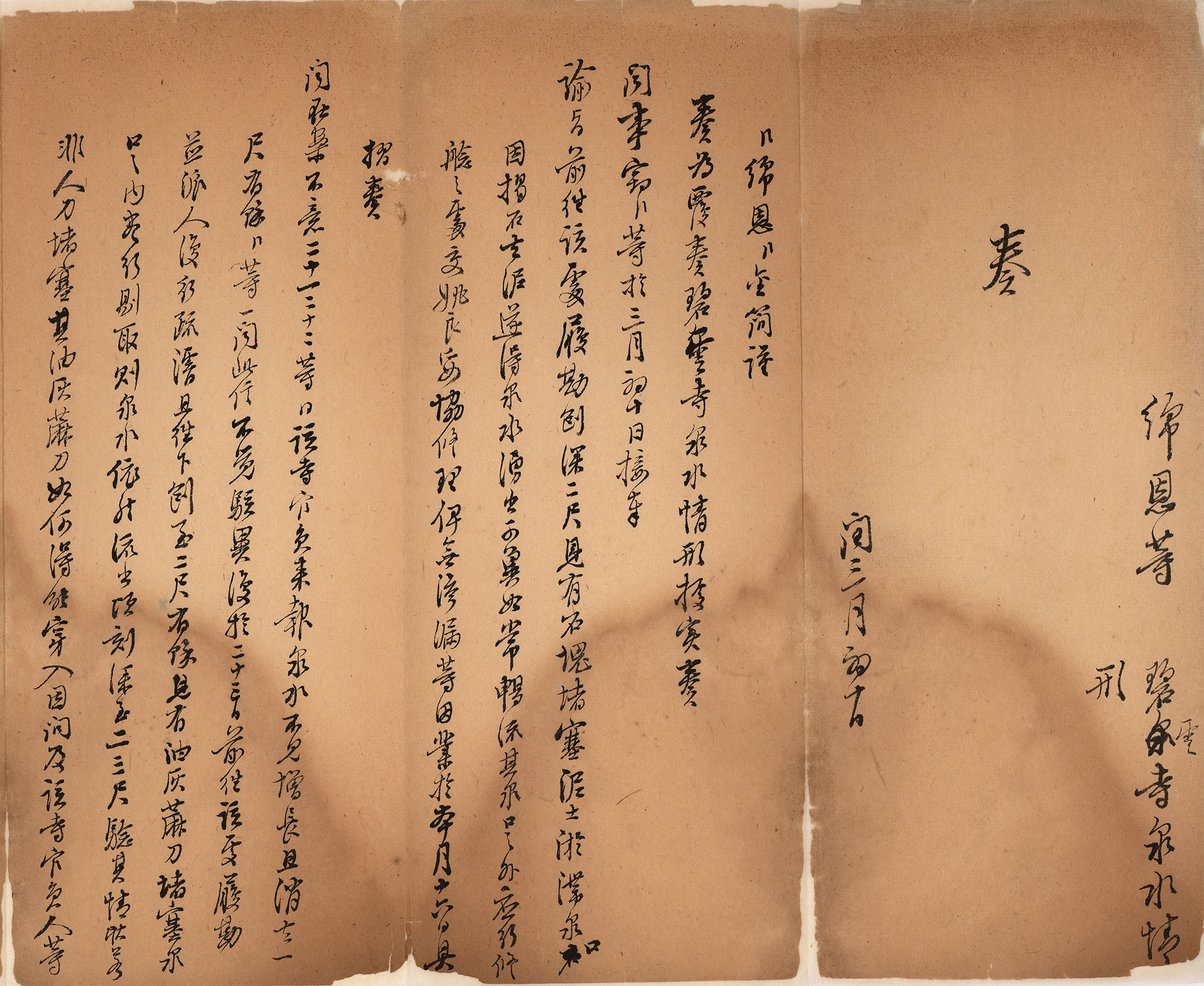

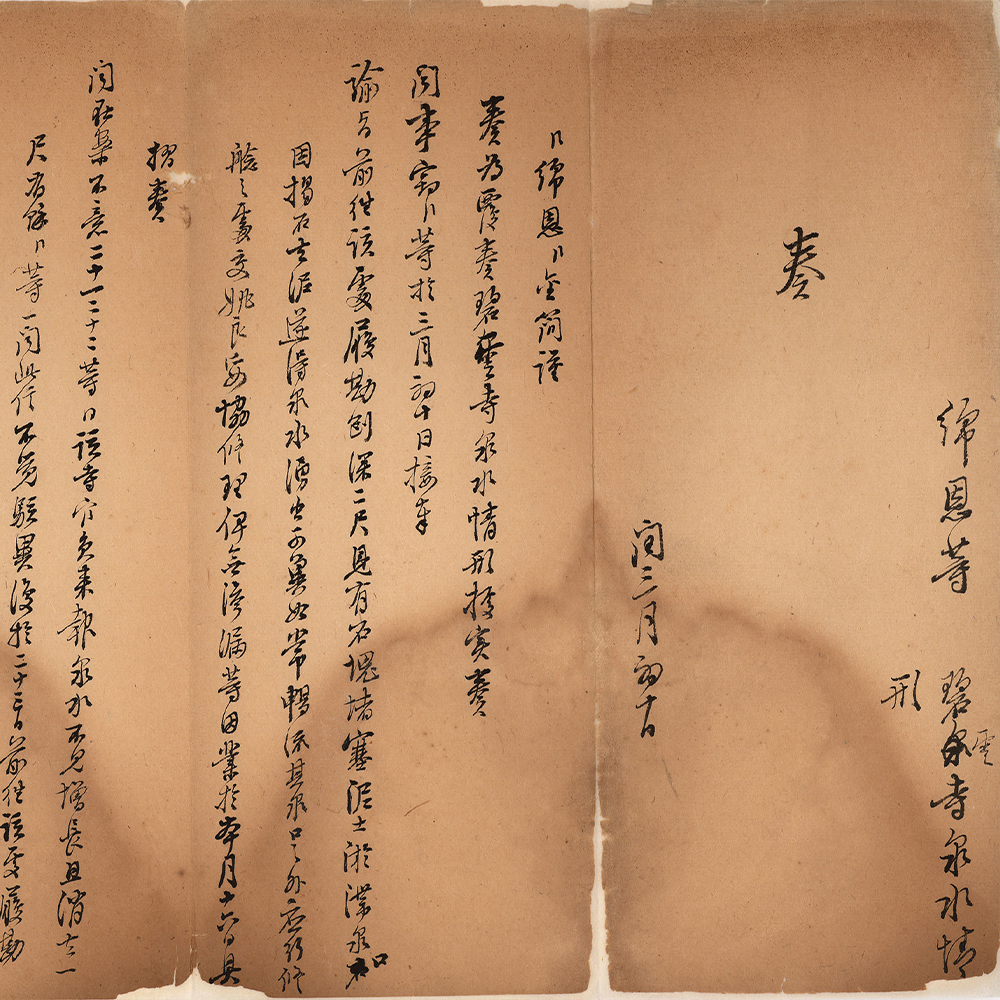

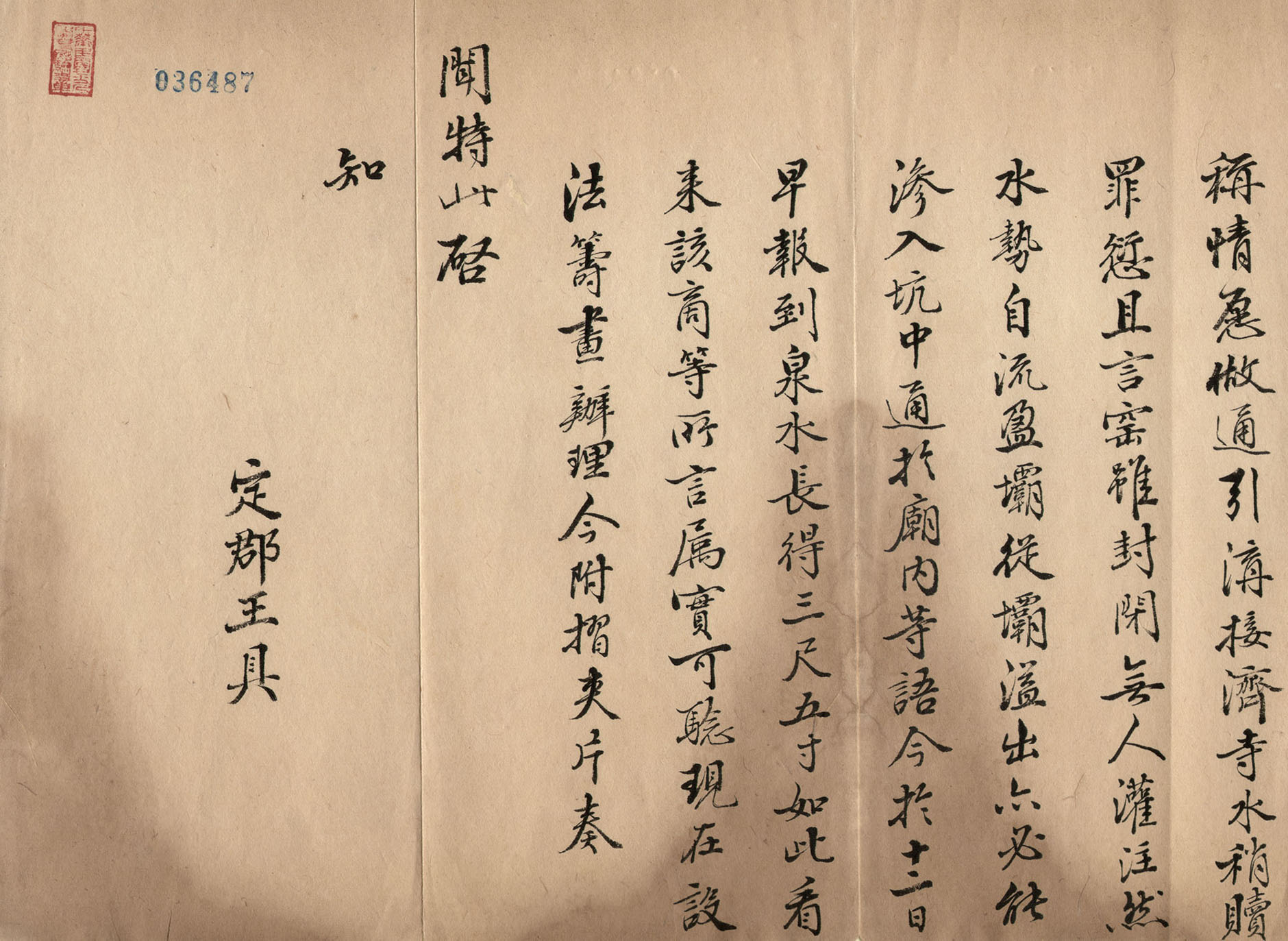

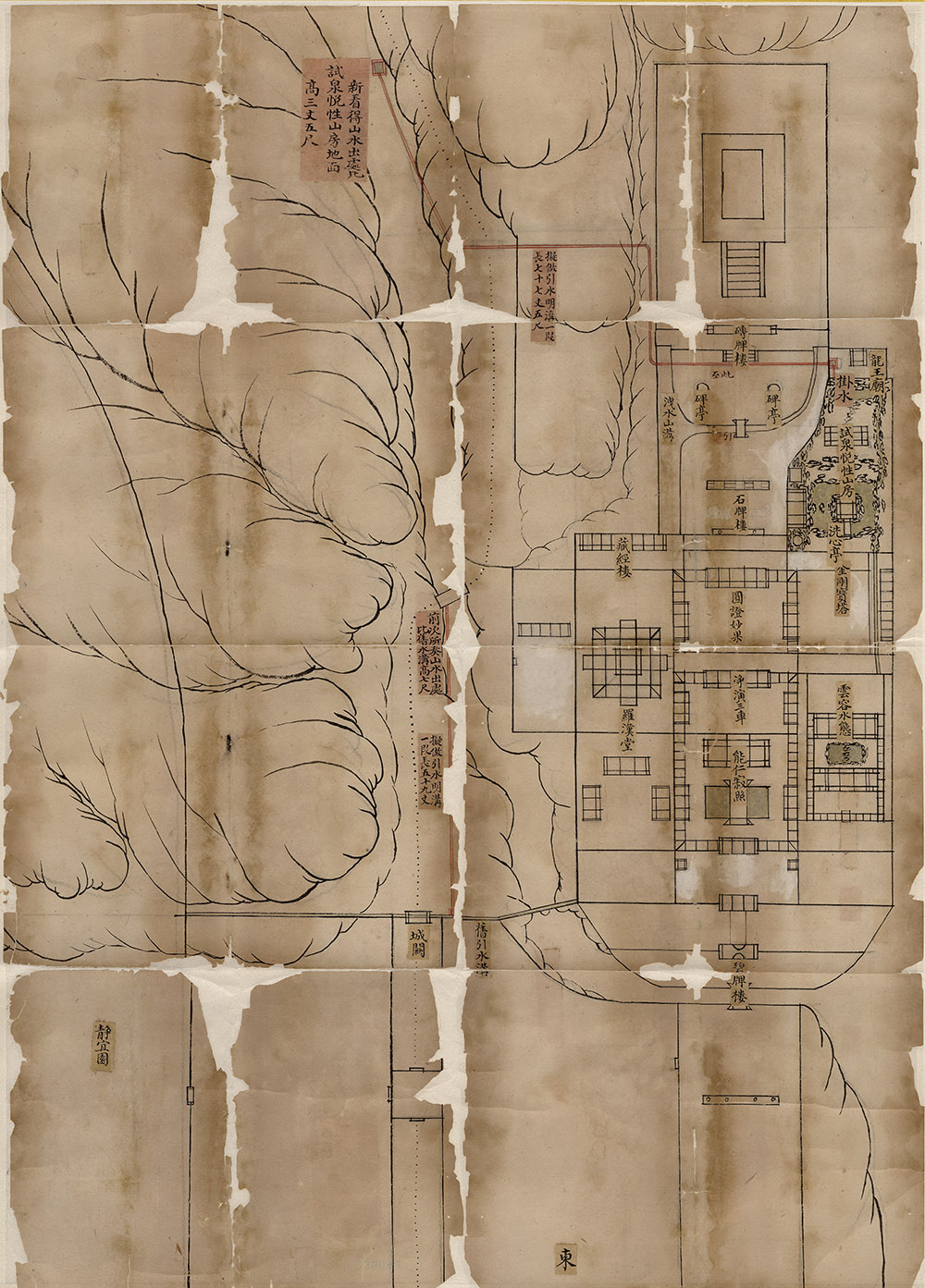

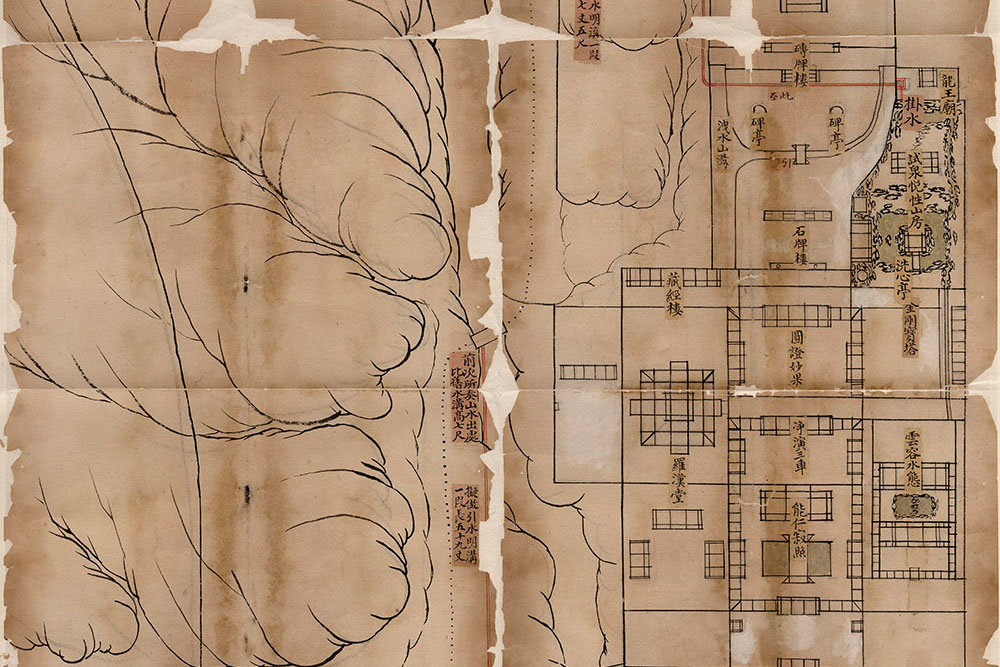

Water resources in Beijing circulate from the western suburbs (i.e., Fragrant Hill and Jade Spring Hill) to the Longevity Hill, forming a water-drawing system regulated by upper and lower springs. However, when spring water supply is unstable, it inevitably affects the entire western suburb imperial garden water system. During the Qianlong era (18th century), coal consumption in Beijing grew exponentially, resulting in extensive mining in the coal mine near the Zhuoxi Spring, the water source of the Biyun Temple in Fragrant Hill. Such an activity devastated the surrounding groundwater circulation, causing the water source of the Biyun Temple to dry up at the end of 1783. The drawing exhibited here shows the topography and landscape map drawn by the officials in charge at the time after their investigation, and their plan of redirecting the water source.

During Emperor Qianlong’s reign, four times (i.e., in 1743, 1754, 1778, and 1783) he visited Shengjing on eastern inspection tours and to offer sacrifices to his ancestors. Except for the first time, where he stayed temporarily at the Shengjing Palace, he always stayed temporarily at the Diguang Palace west of the Shengjing Palace.

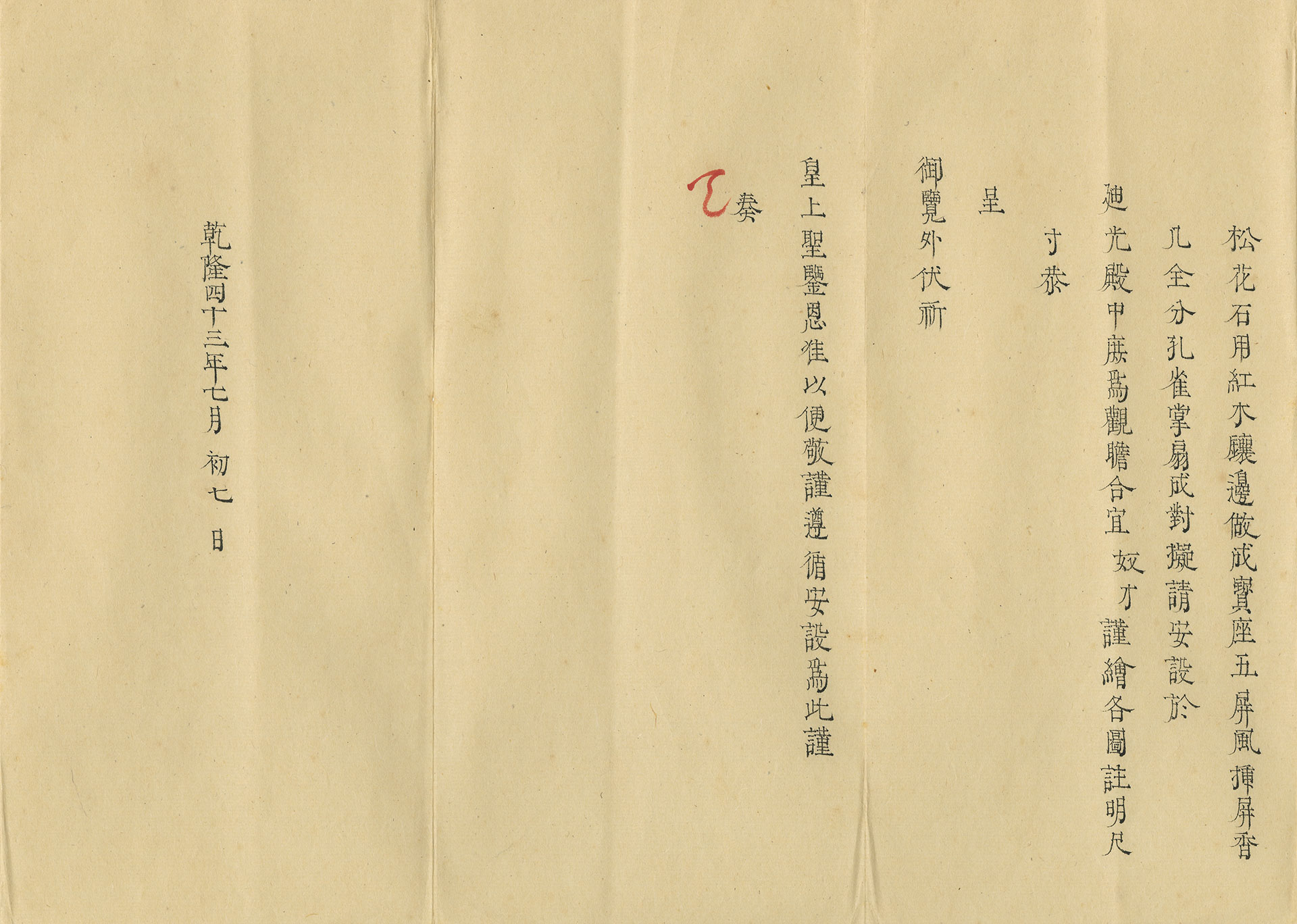

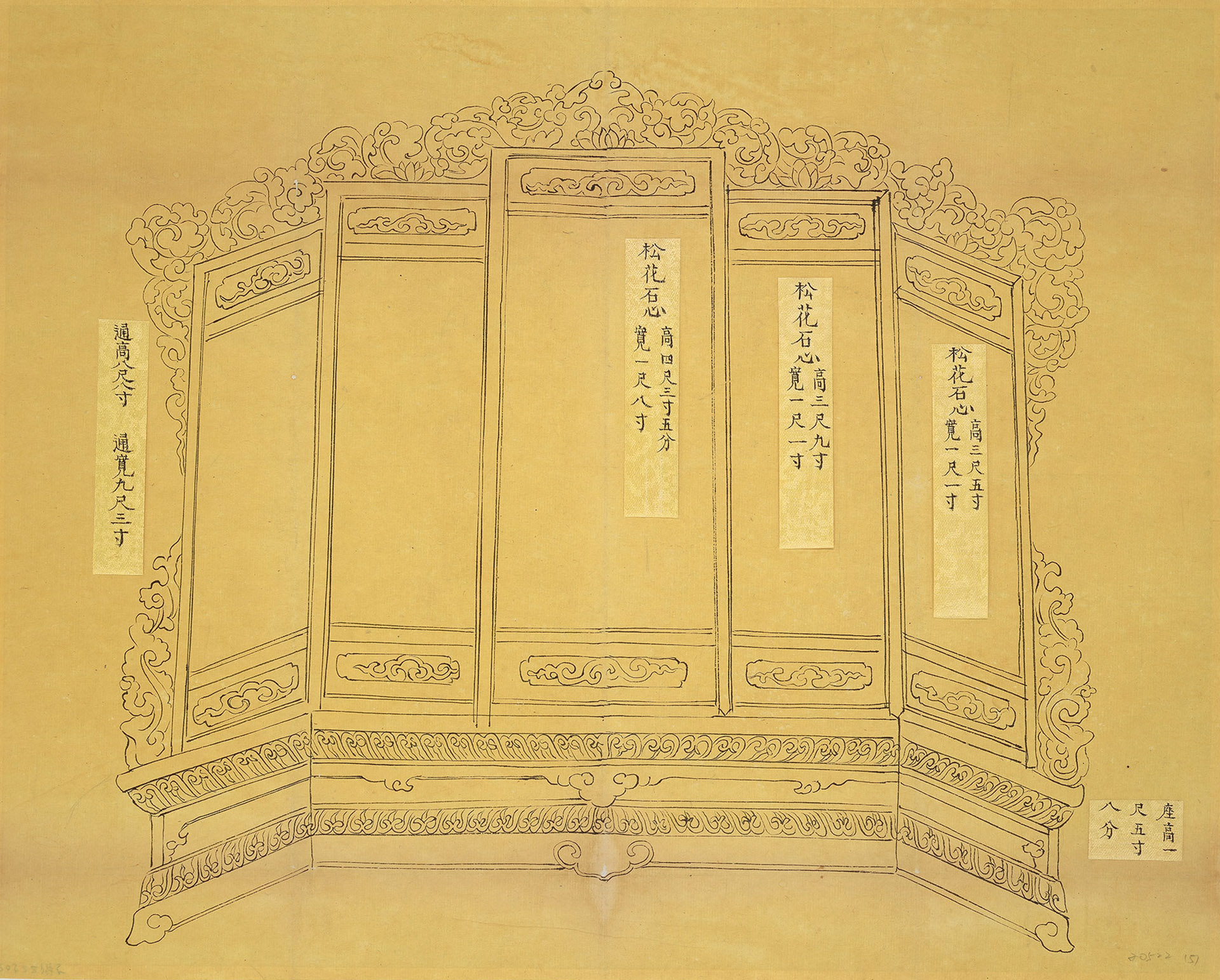

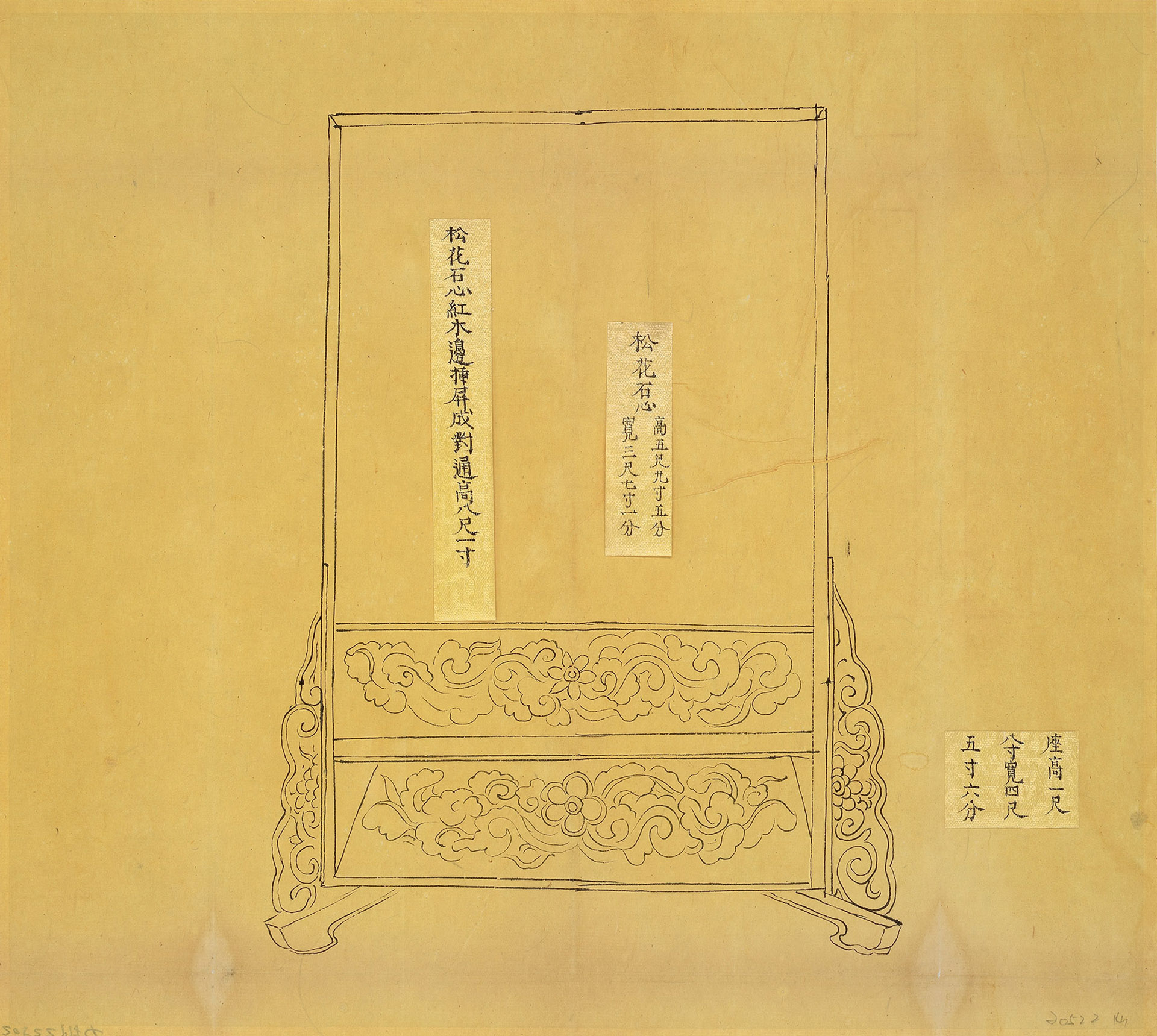

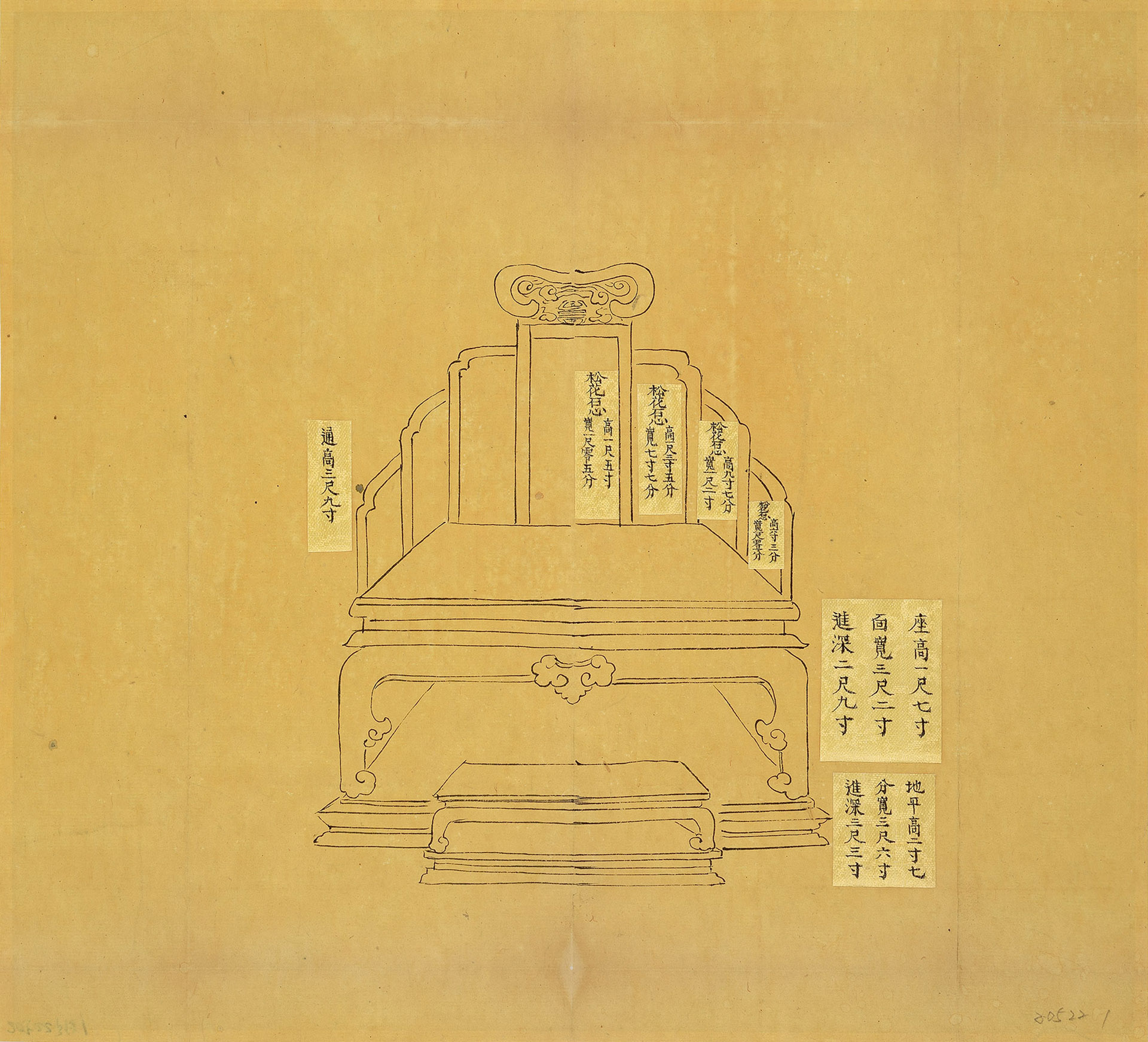

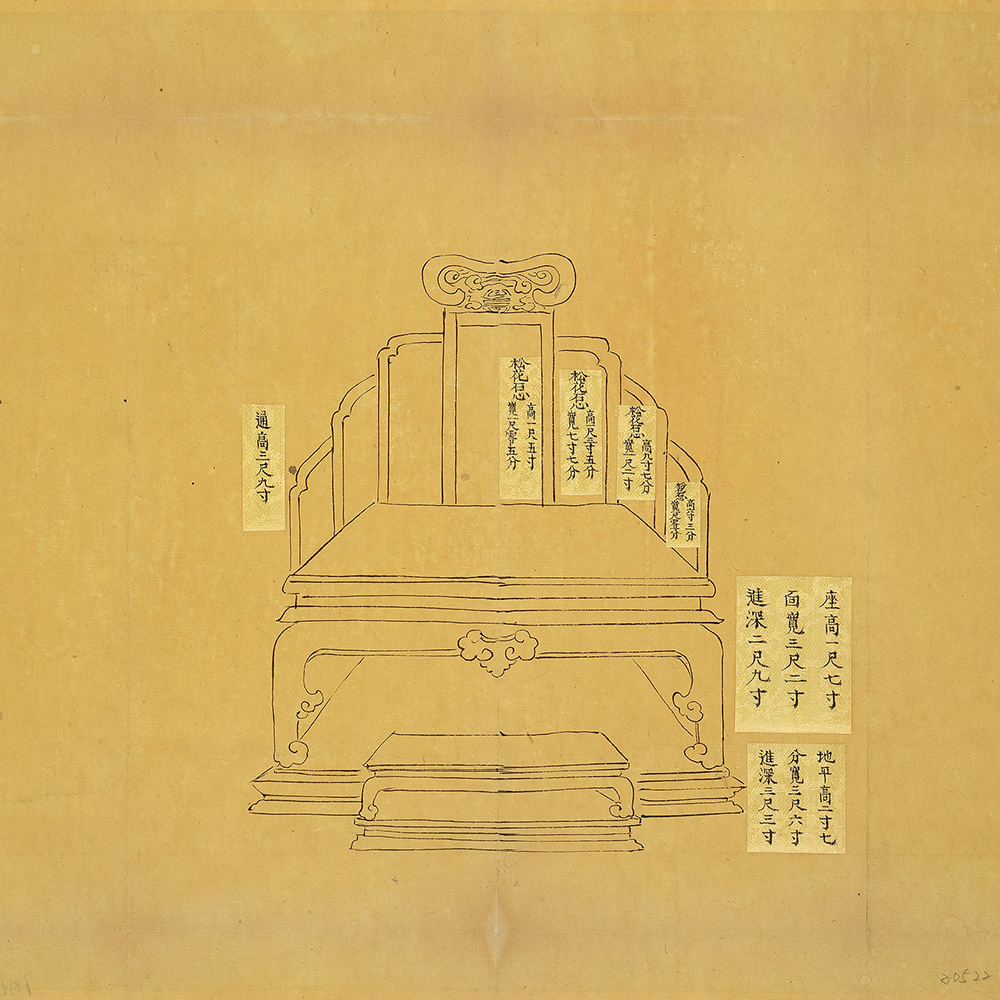

The Diguang Palace was built in 1748. Its name was given by Emperor Qianlong, who chose this name because it signified him being “enlightened by and expanding the foundation built by his ancestors.” In July 1778, prior to the emperor’s third eastern inspection tour, Hong Shang (1718-1781), the General of Shengjing, requested that the emperor issue a decree demanding that the Diguang Palace manufacture an emperor’s chair (made of rosewood) embellished with Songhua stones produced in Northeast China, five screens, table screens, incense tables (made of rosewood), and hand fans decorated with peacock designs. The drawings displayed here are those designed by the craftsmen of the Imperial Household Department commissioned to manufacture the aforementioned items at the time.

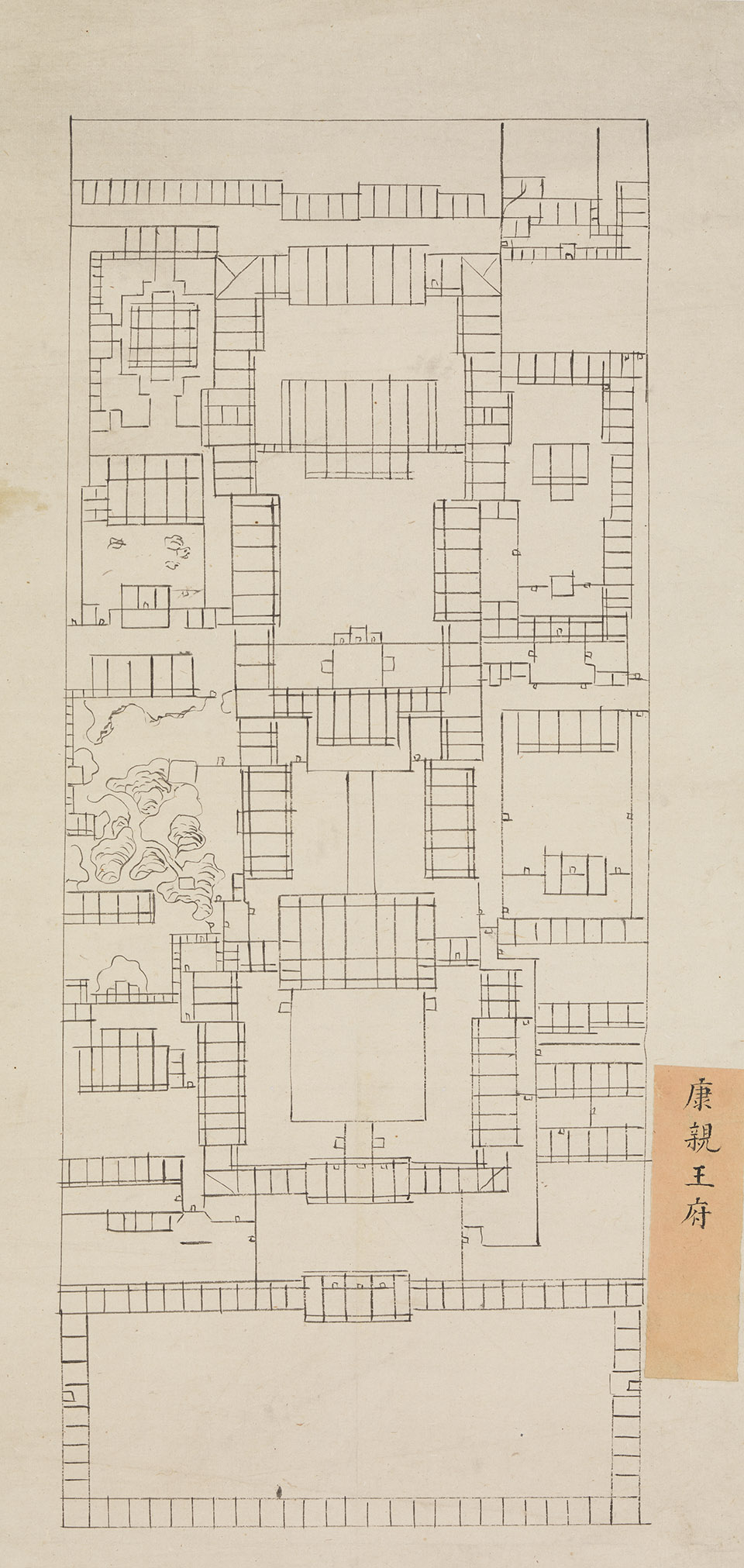

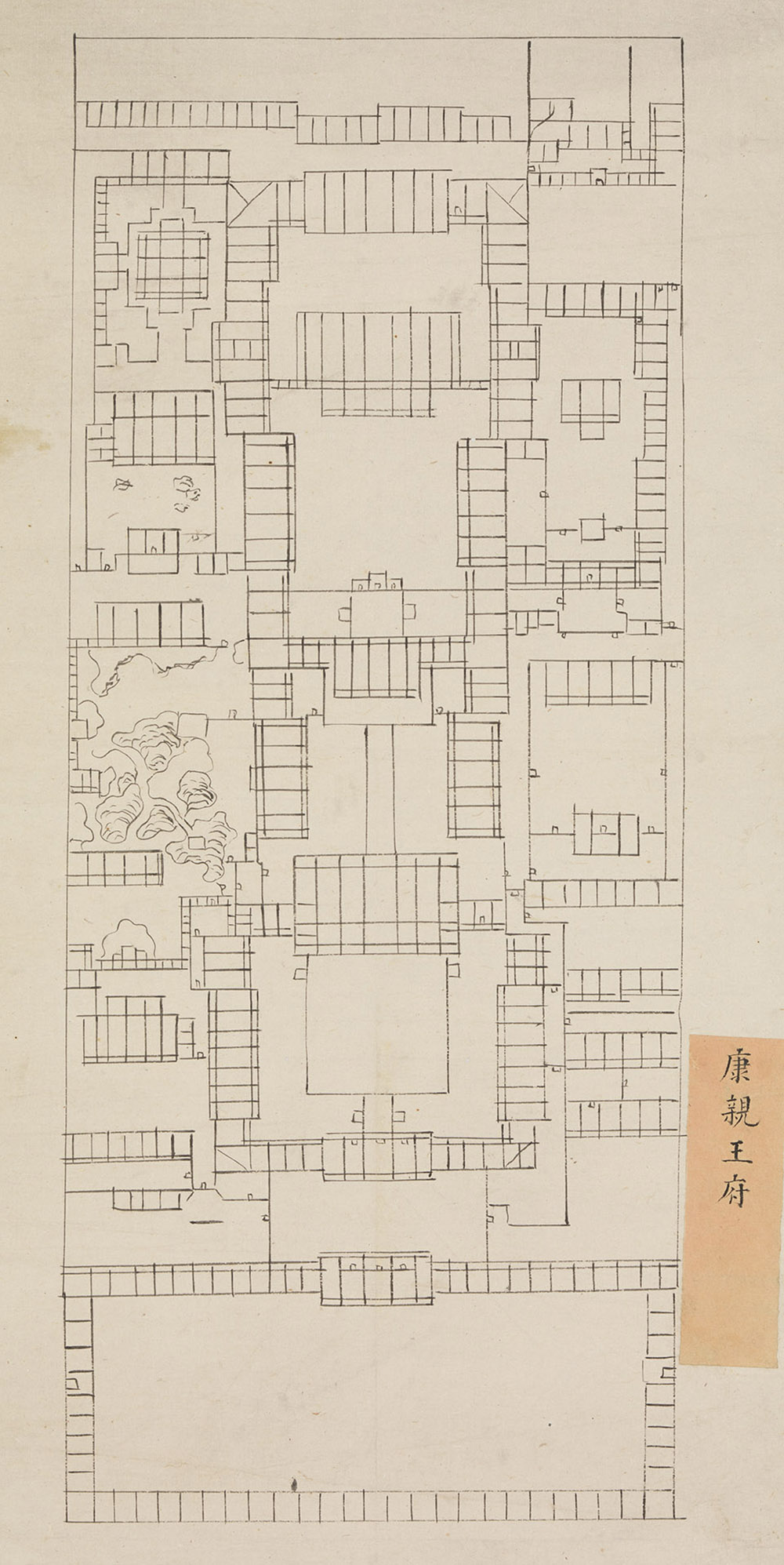

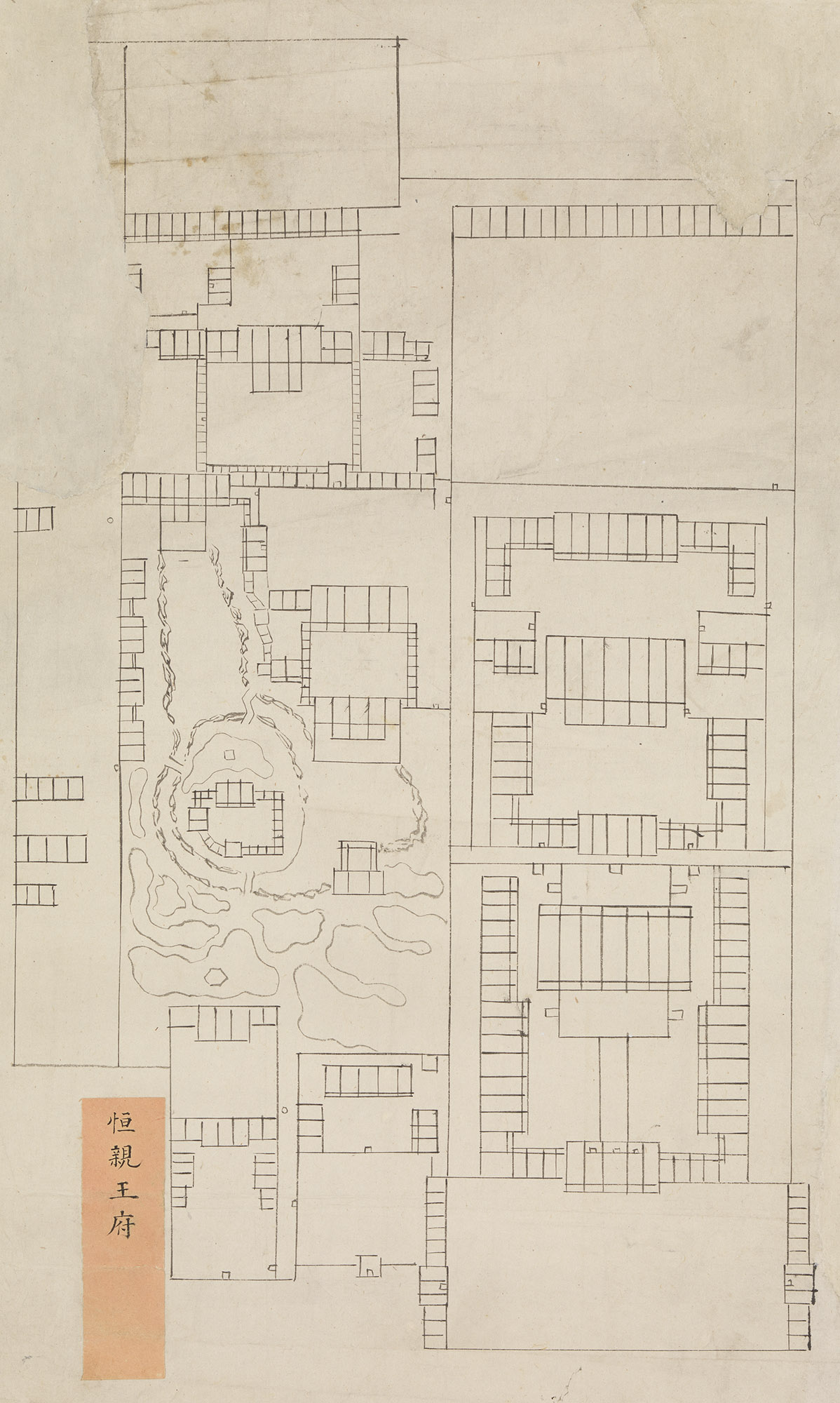

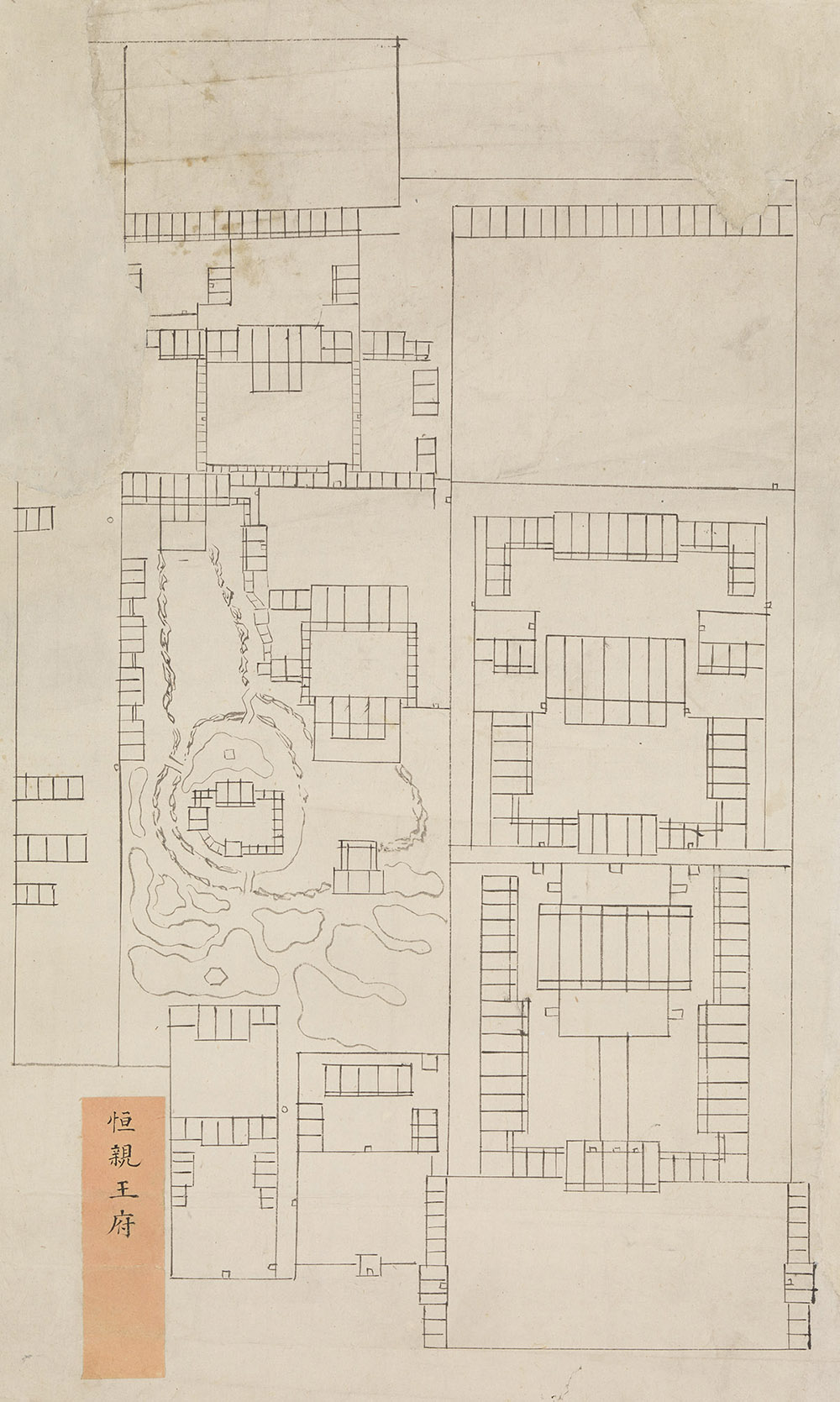

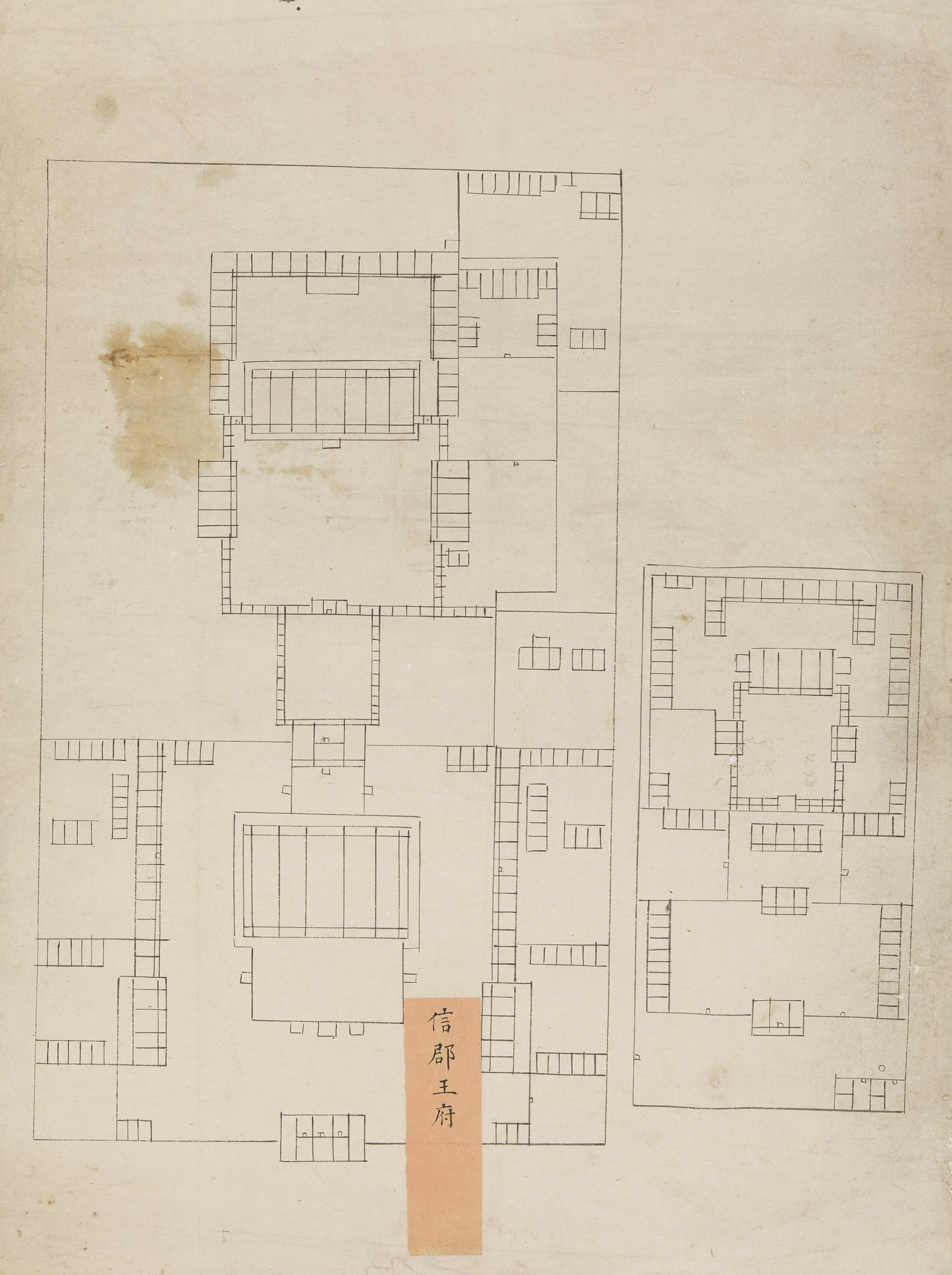

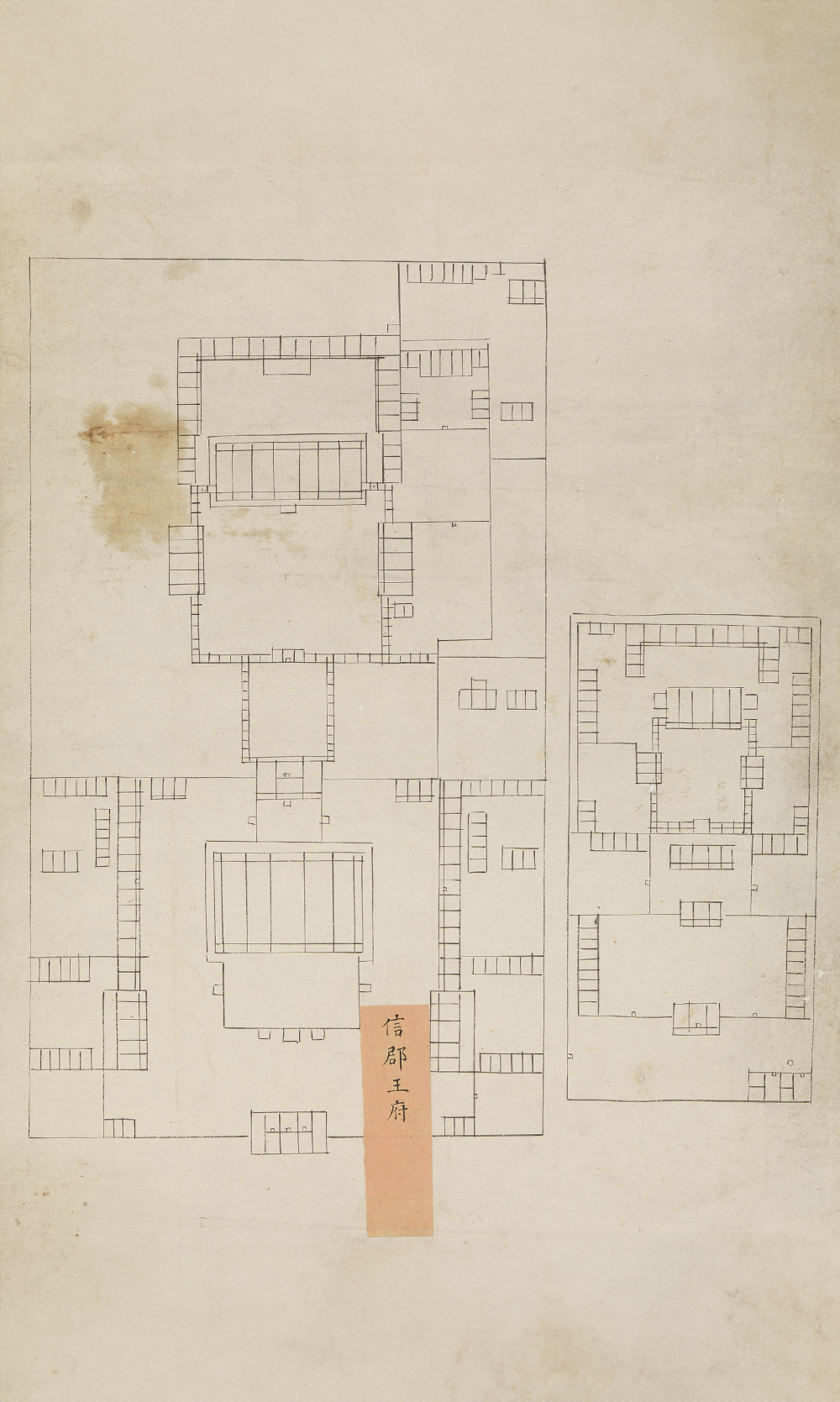

- Official residence of Prince Kang of the First Rank

In the Qing dynasty, the ranks of the imperial family members were divided into 12 based on their closeness (in terms of kinship) with the emperors. The ranks, listed in descending order, included Prince of the First Rank, Prince of the Second Rank, Prince of the Third Rank, Prince of the Fourth Rank, highest-ranking officials, and generals. When these members grew up and were ordered to move out of the palaces, the imperial court granted them official residences based on their ranks. Prior to these members moving in, however, officials from the Imperial Household Department and the Ministry of Works would first inspect the existing conditions of the official residences, and drew pictures for the emperors to review. If renovations were required, they would list out the projected costs for the emperors to make a decision.

The National Palace Museum houses the drawings of the official residences of Prince Kang of the First Rank, Prince Heng of the First Rank, and Prince Xin of the Second Rank. Further investigation revealed that Prince Kang of the First Rank was originally Daisan (Prince Li of the First Rank, 1583-1648). In 1659, Giyesu (Prince Kang of the Second Rank, 1646-1697) became Prince Kang of the First Rank. In 1778, in memory of Daisan’s military exploits, Yong’en (1727-1805), Giyesu’s great grandson, decreed that Daisan’s title be reverted back to Prince Li of the First Rank. Concerning Prince Xin of the Second Rank, he was originally Dodo (Prince Yu of the First Rank, 1614-1649). In 1652, Dodo’s son Doni (Prince of the First Rank, 1636-1661) demoted Dodo to Prince Xin of the Second Rank because of his involvement in the Dorgon (1612-1650) political power struggle. In 1778, in memory of Dodo’s military exploits in founding the Qing dynasty, Dodo was regranted the title of Prince Yu of the First Rank. Regarding Yunki (1709-1732), Emperor Kangxi’s fifth son, he was bestowed the title of Prince Heng of the First Rank in 1709. However, he and his son (Hongzhi, 1732-1775) and grandson (Yonghao, 1755-1788) never inherited the throne. Therefore, Yunki was posthumously demoted to Prince Heng of the Second Rank.

According to the changes in the ranks of the three aforementioned princes, we surmise that the drawings of the three official residences were renovation drawings submitted to the emperor for review between 1775 and 1778.