Imperial Architectural Drawings

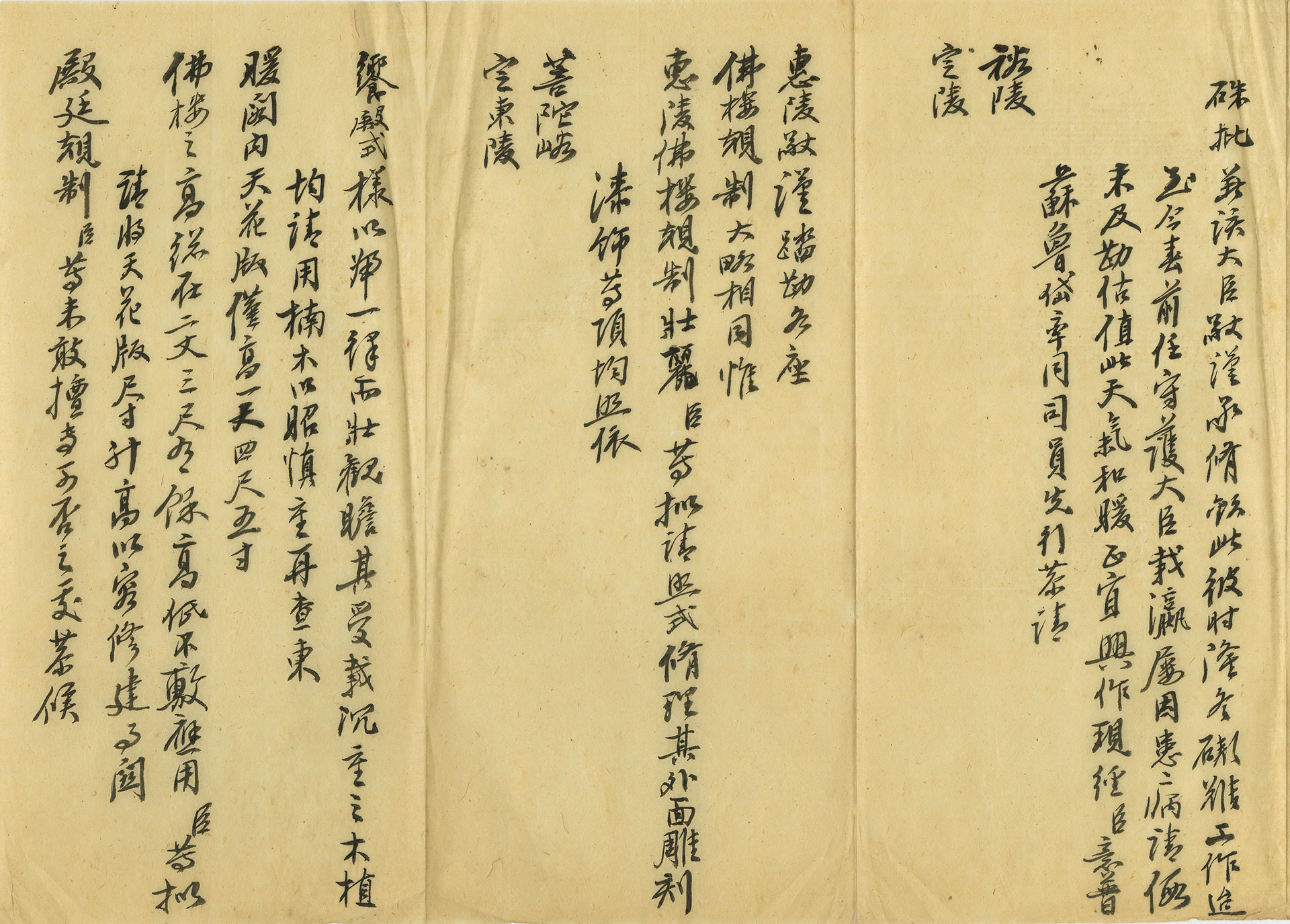

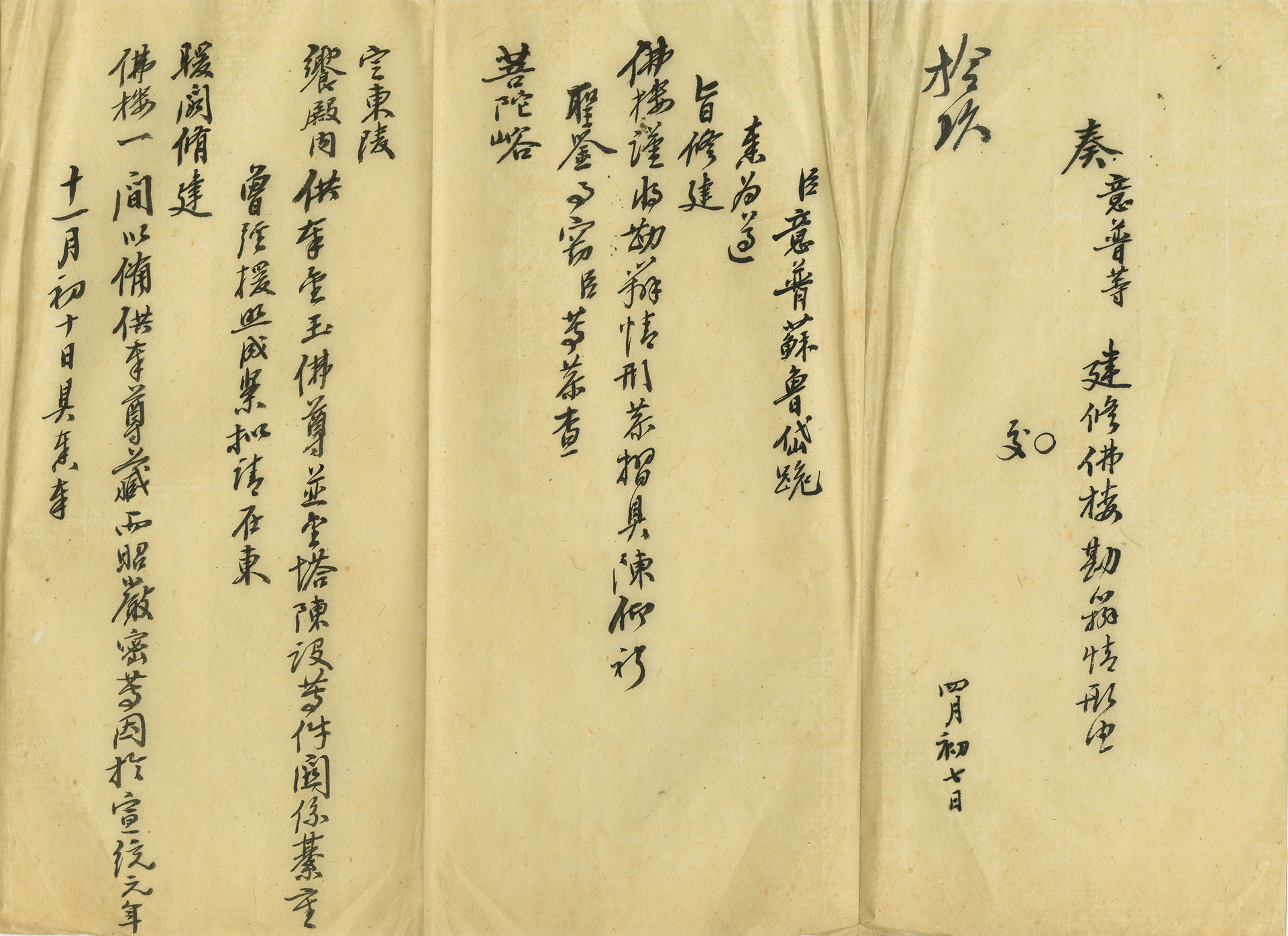

In the Qing Dynasty, the construction, expansion, and interior decoration of imperial palaces, the capital city, altars, temples, imperial mausoleums, gardens, and mansions were all under the jurisdiction of the "Ministry of Works", overseen by the "Imperial Household Department", and managed by the "Construction Bureau" (Imperial Commission Construction Bureau). This bureau was composed of trusted high-ranking officials appointed by the emperor and was responsible for coordinating design institutions for various projects.

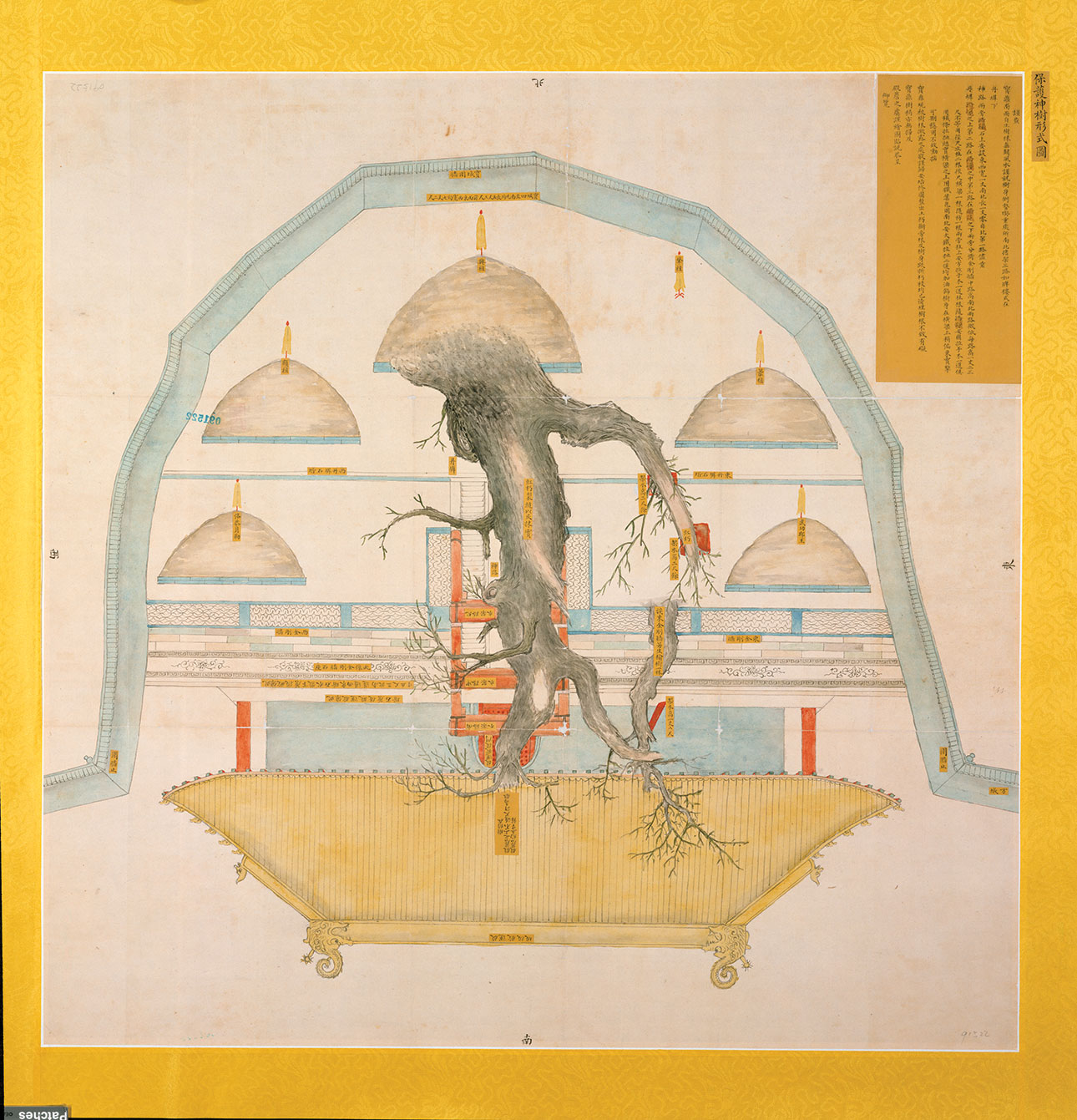

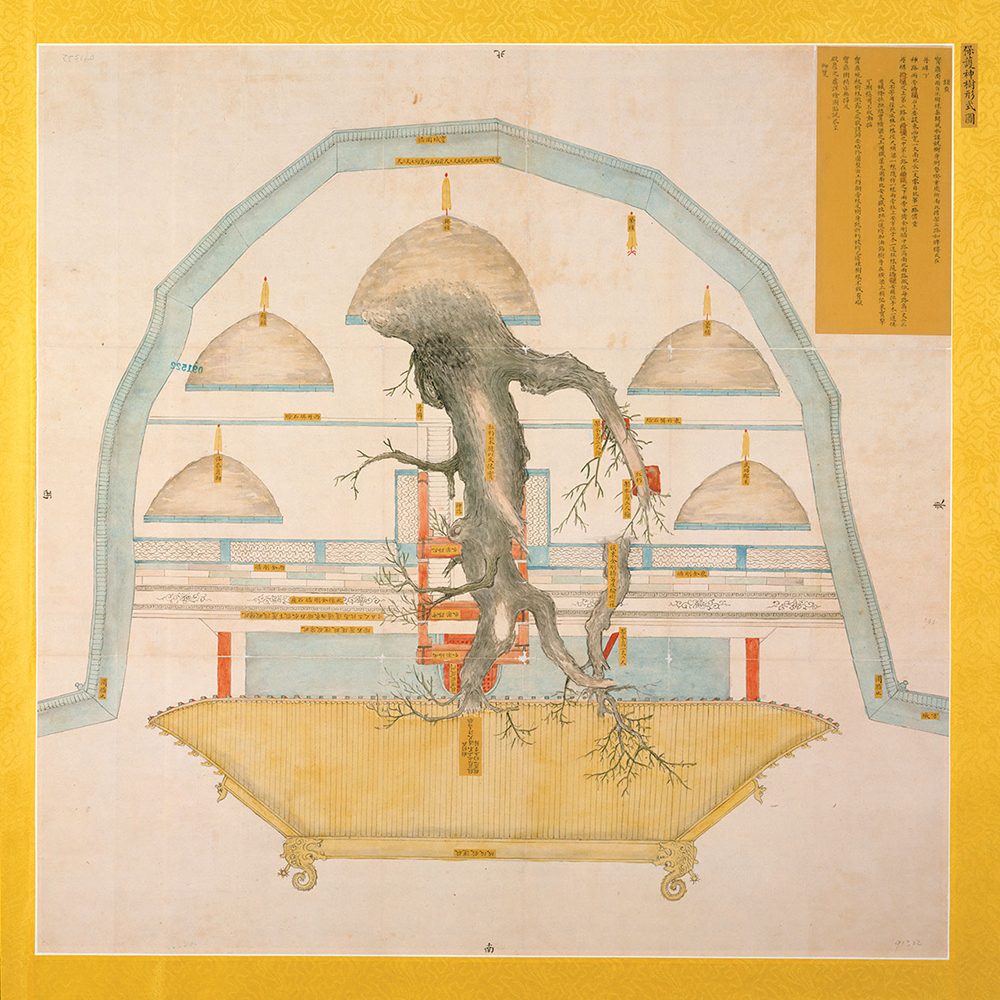

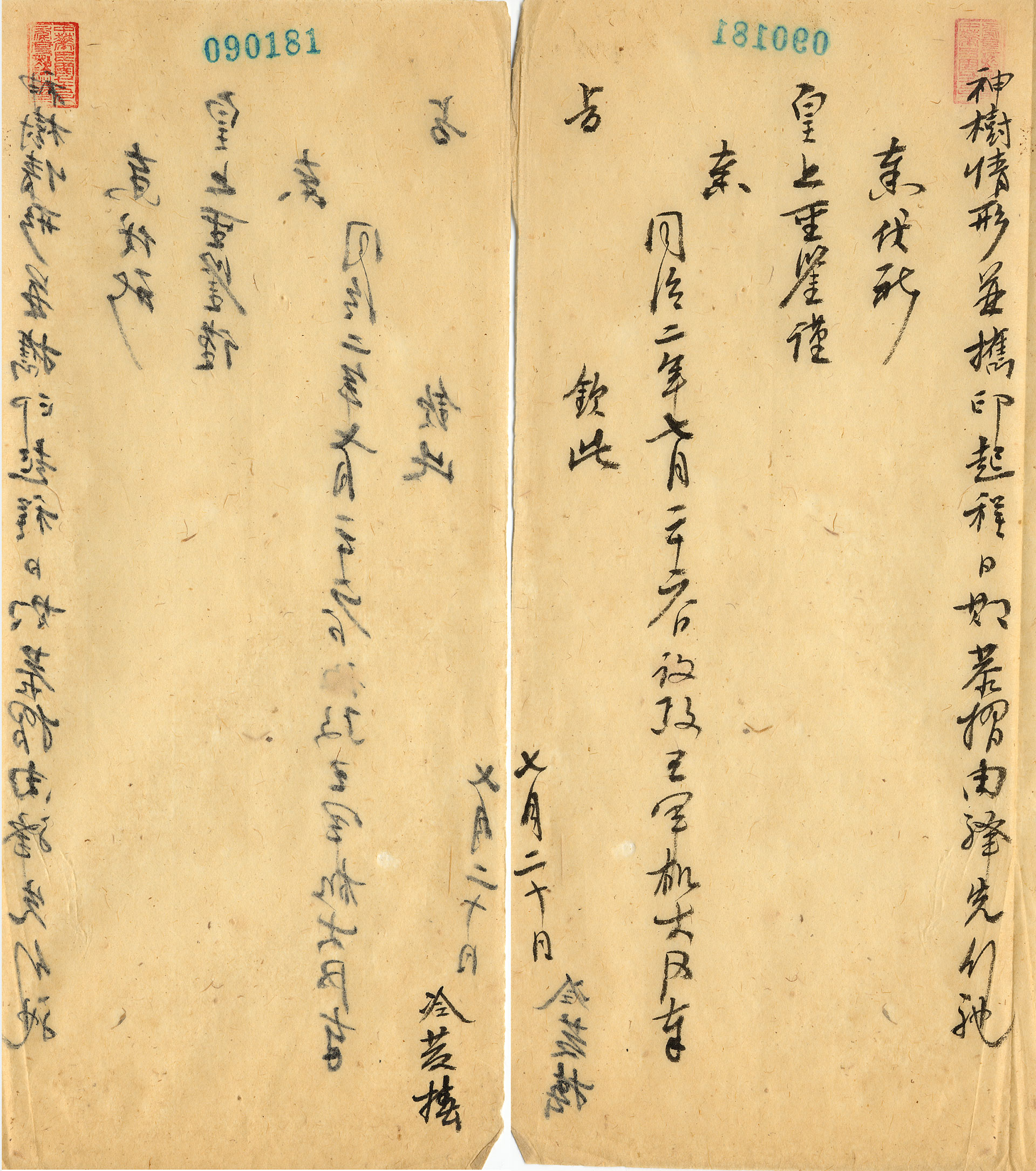

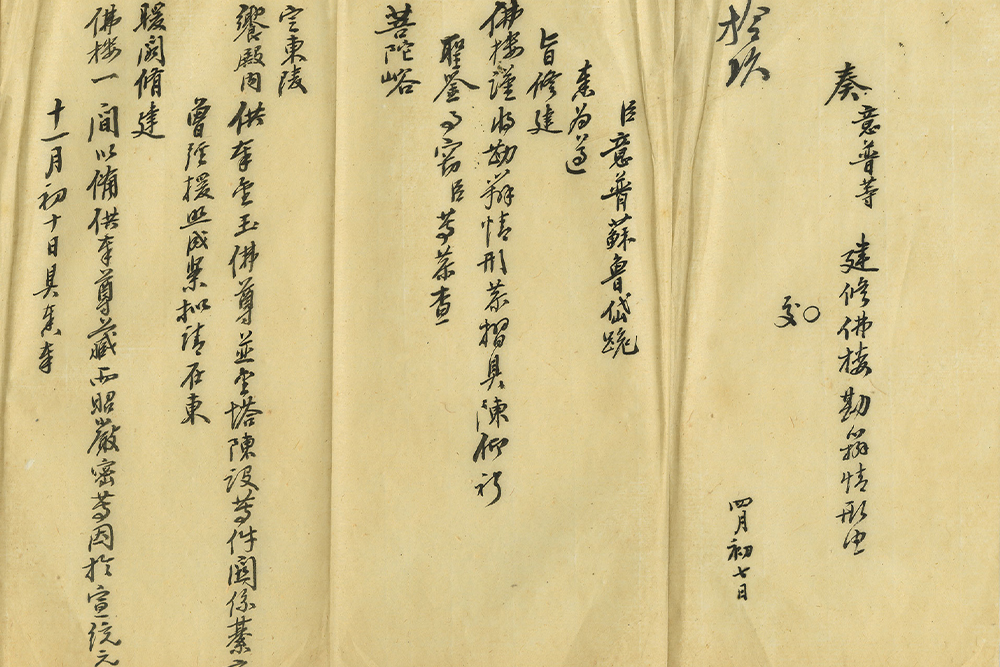

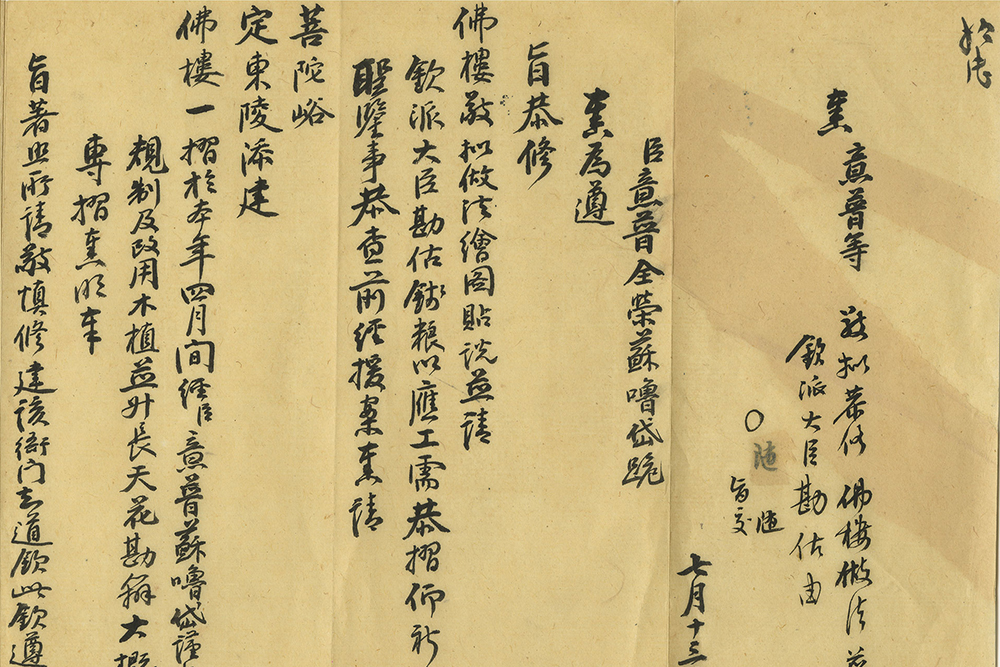

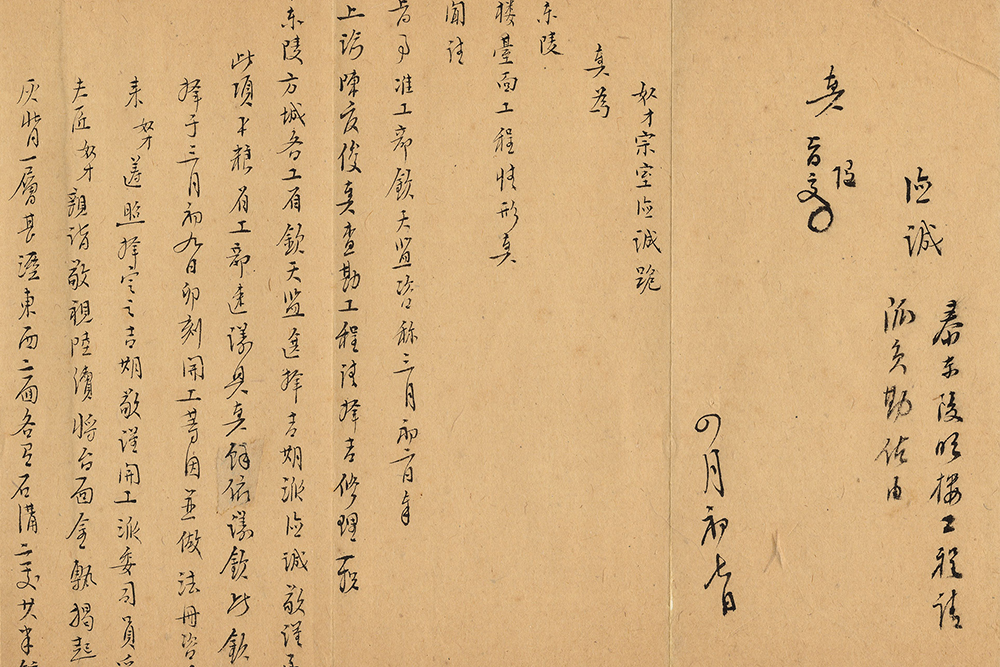

The ministers responsible for construction projects in the Qing Dynasty first conducted design planning, surveyed and measured the spaces, and drew draft sketches. Through multiple revisions, from rough drafts to detailed drawings, they ultimately created the "presentation model" for submission to the emperor. The ministers and presenting the detailed planning through drawings also submitted explanatory reports. When necessary, they would create architectural models, referred to as " Tang yang " or "stamped models," to provide the emperor with a comprehensive understanding of the project.

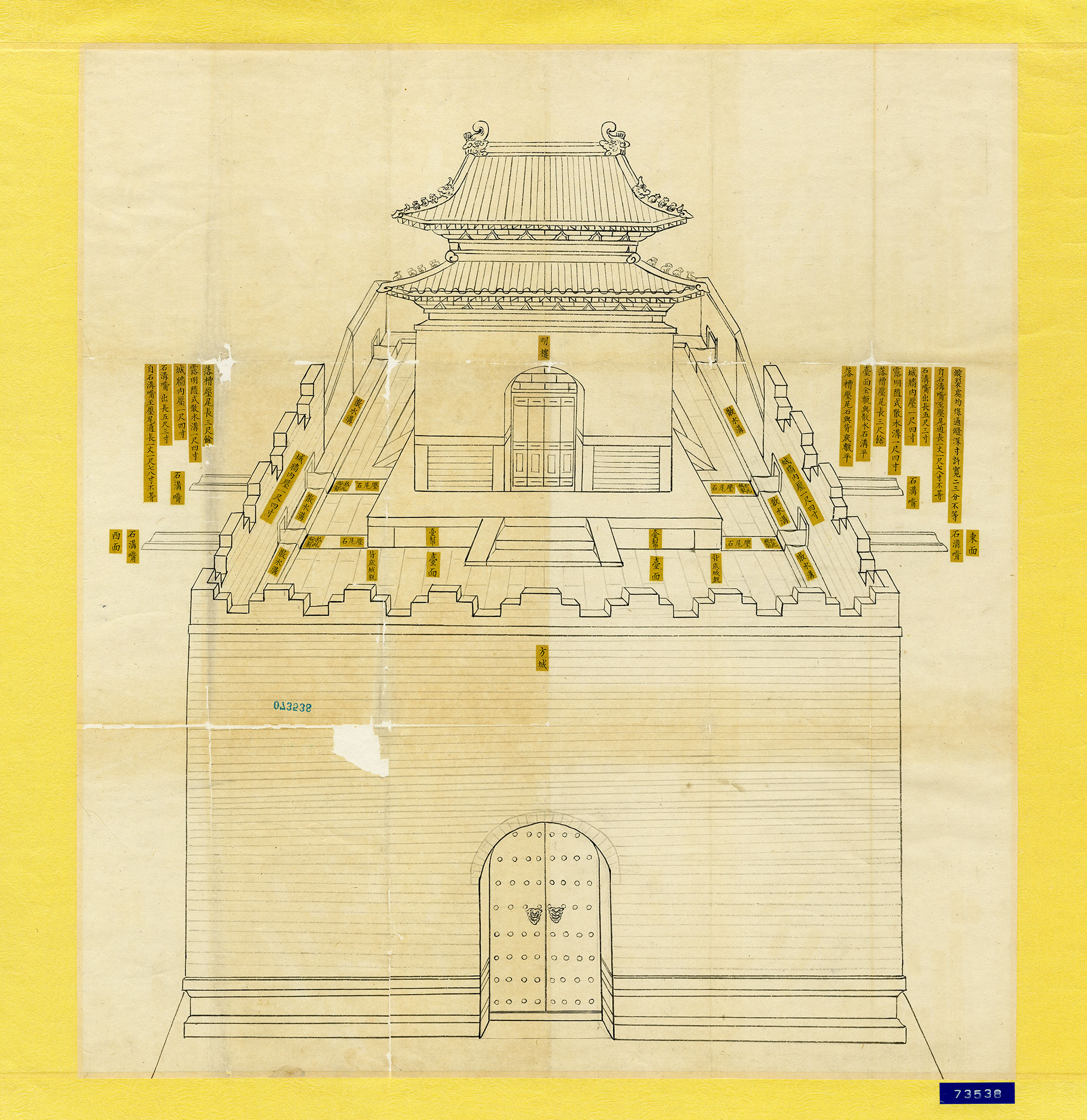

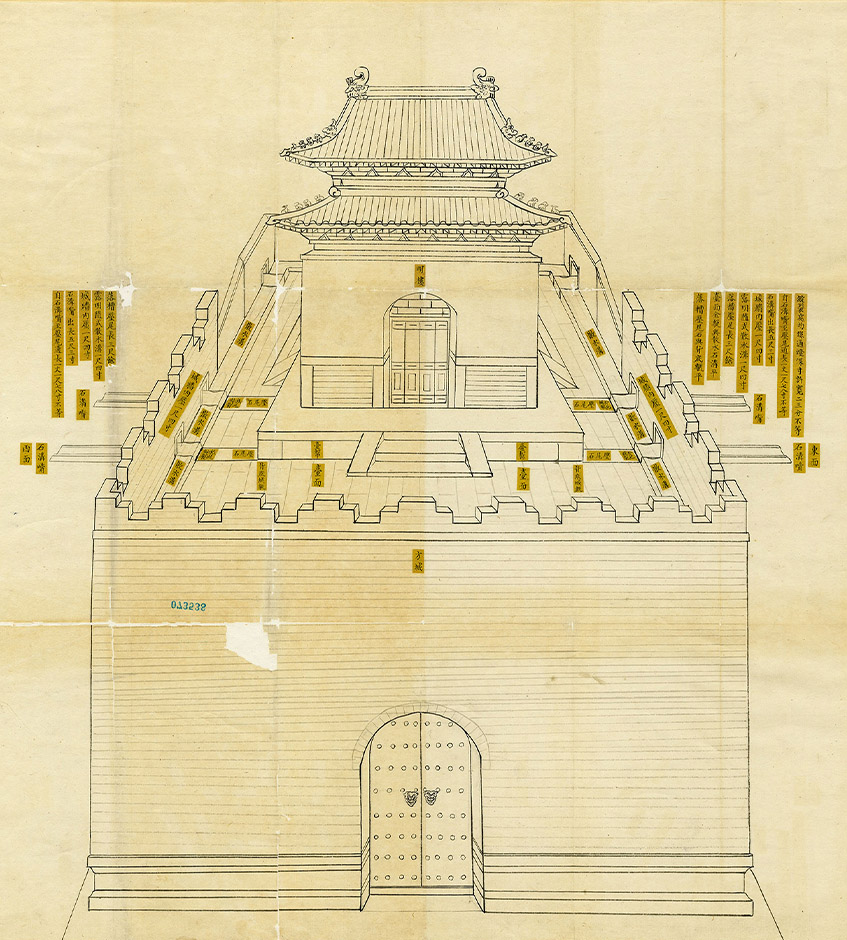

In these "presentation model drawings", various colored strips of paper, typically yellow and red, were often affixed, containing detailed explanations of the project known as "drawing annotations". After the emperor reviewed the presentation model, if there were any suggested revisions, it would be returned for corrections. In some cases, the emperor would provide instructions to keep the records for his further review before submitting them to the Grand Council for archival purposes. Our institution houses these various forms of presentation models and architectural drawings that were reviewed by the emperor. In this section, we will showcase representative documents from three major categories: "Palace and Garden Construction Drawings", "Temple Construction Drawings", and "Mausoleum Construction Drawings".

Mausoleum Construction Drawings

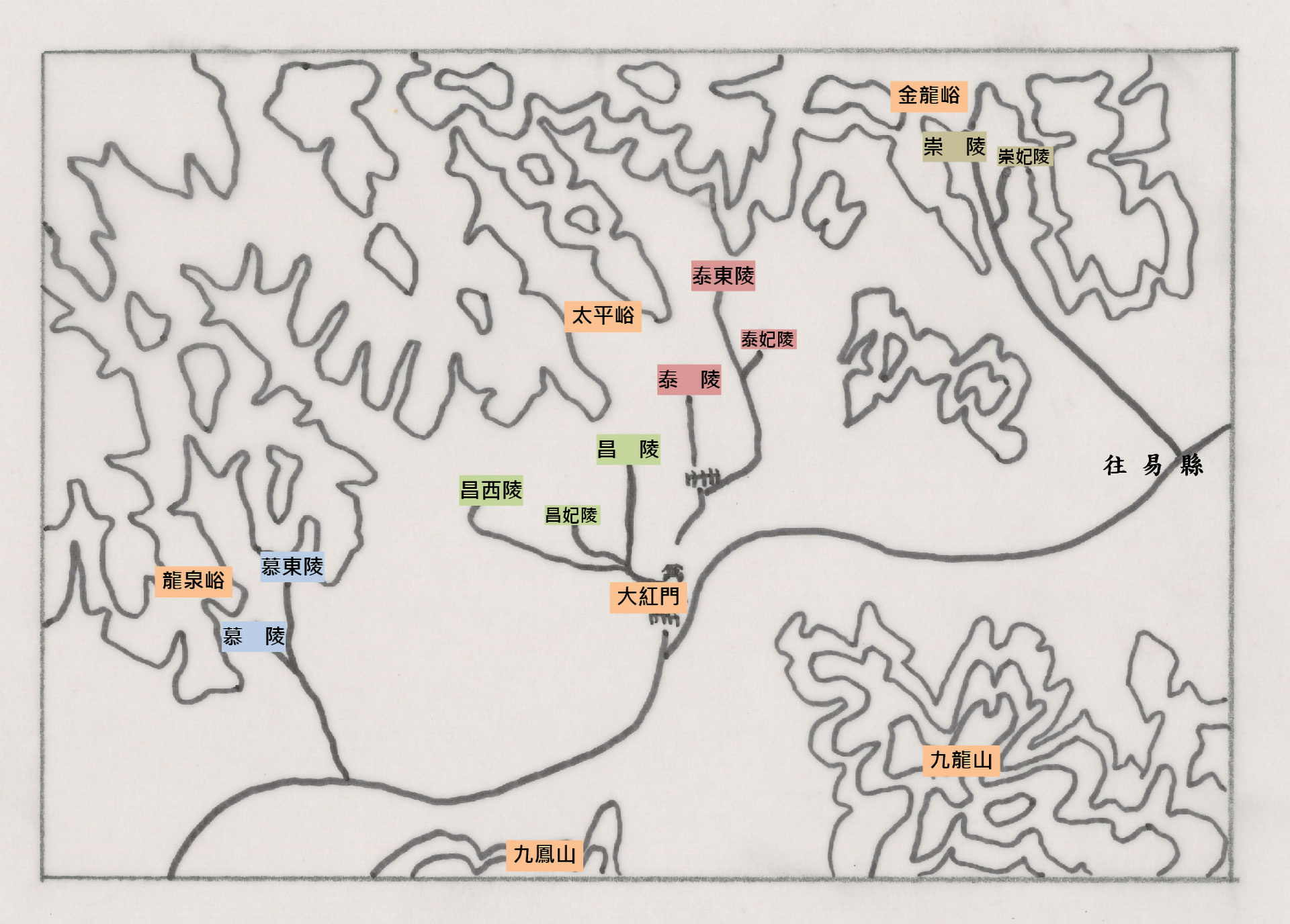

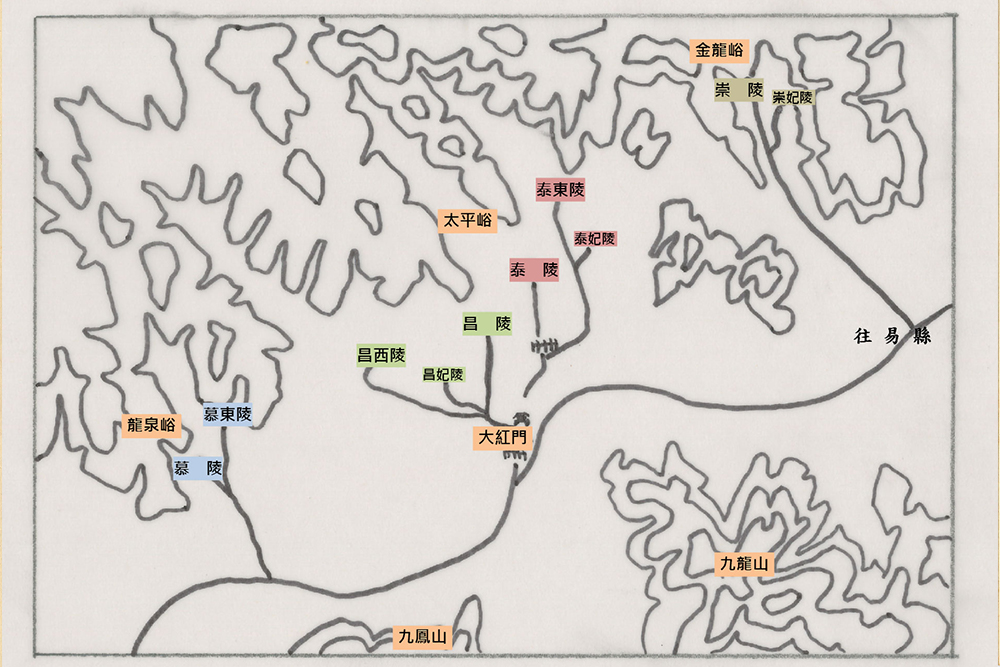

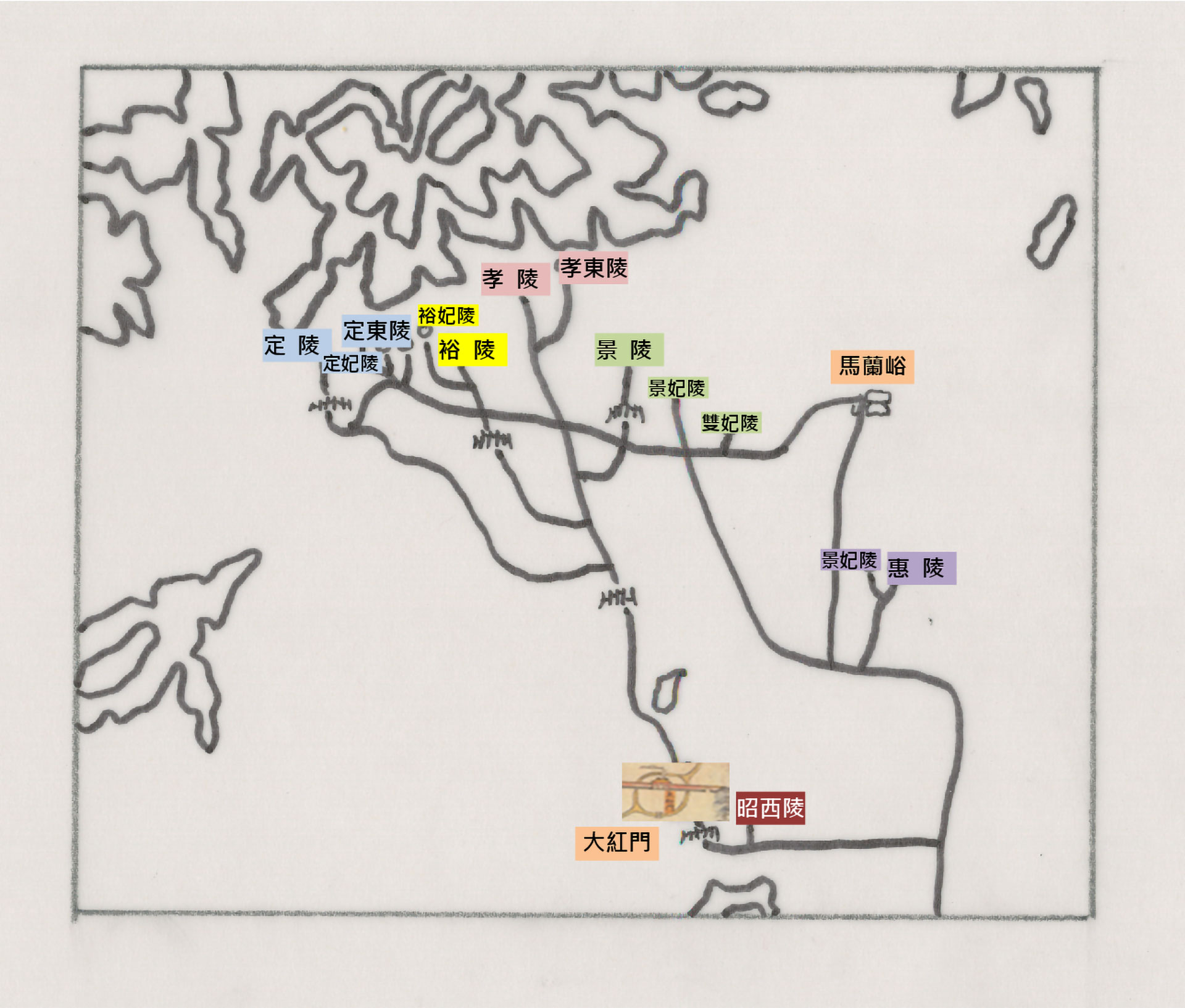

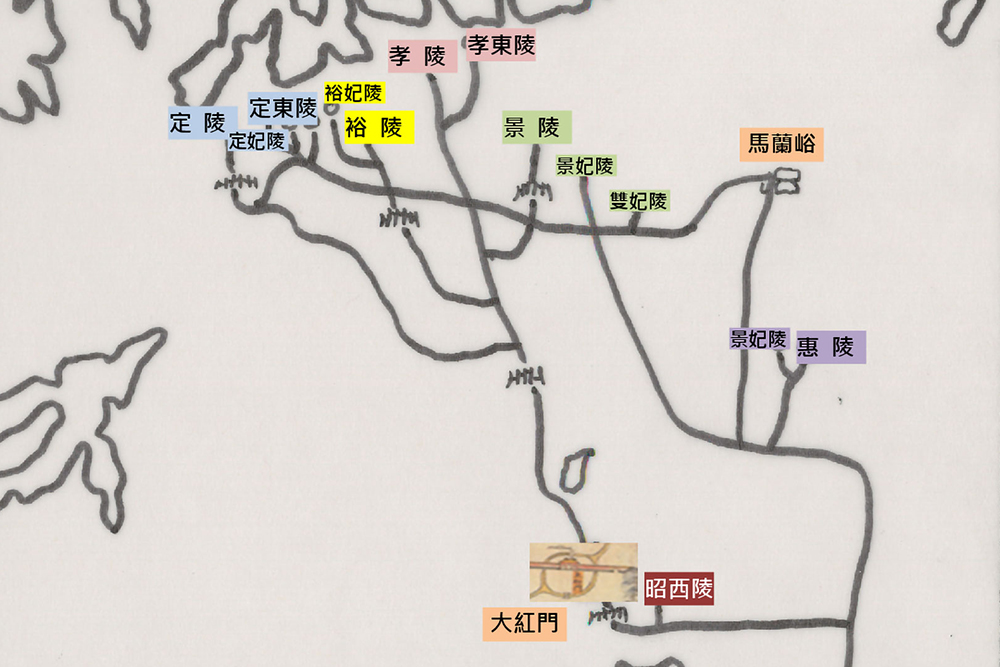

As the final resting places for emperors and empresses to last for tens of thousands of years, the Qing imperial family attached great importance to the construction of mausoleums. Thus, all emperors who ascended the throne would immediately choose their final resting places. The construction of mausoleums begins with the selection of auspicious sites, the surveying of feng shui and mausoleum topography, related planning and designing, and the initiation of construction. In the Qing dynasty, mausoleums were divided into East and West Mausoleums (the East Mausoleum was located in the Zhili Zunhua State, whereas the West Mausoleum was located in the Zhili Yi State). Both mausoleums had a big red gate as its main entrance and various building parts such as decorated archways, stele pavilions, the Hall of Enormous Grace, tall buildings in front of the emperors’ mausoleums, and round wall tops. The architectural decorations of the inner and outer eaves of the halls were all exquisite. The drawings and documents displayed here were the drawings and documents that architects (who built large-scale architecture) presented to emperors and empresses for review that were subsequently preserved in the Office of Military Secrets.

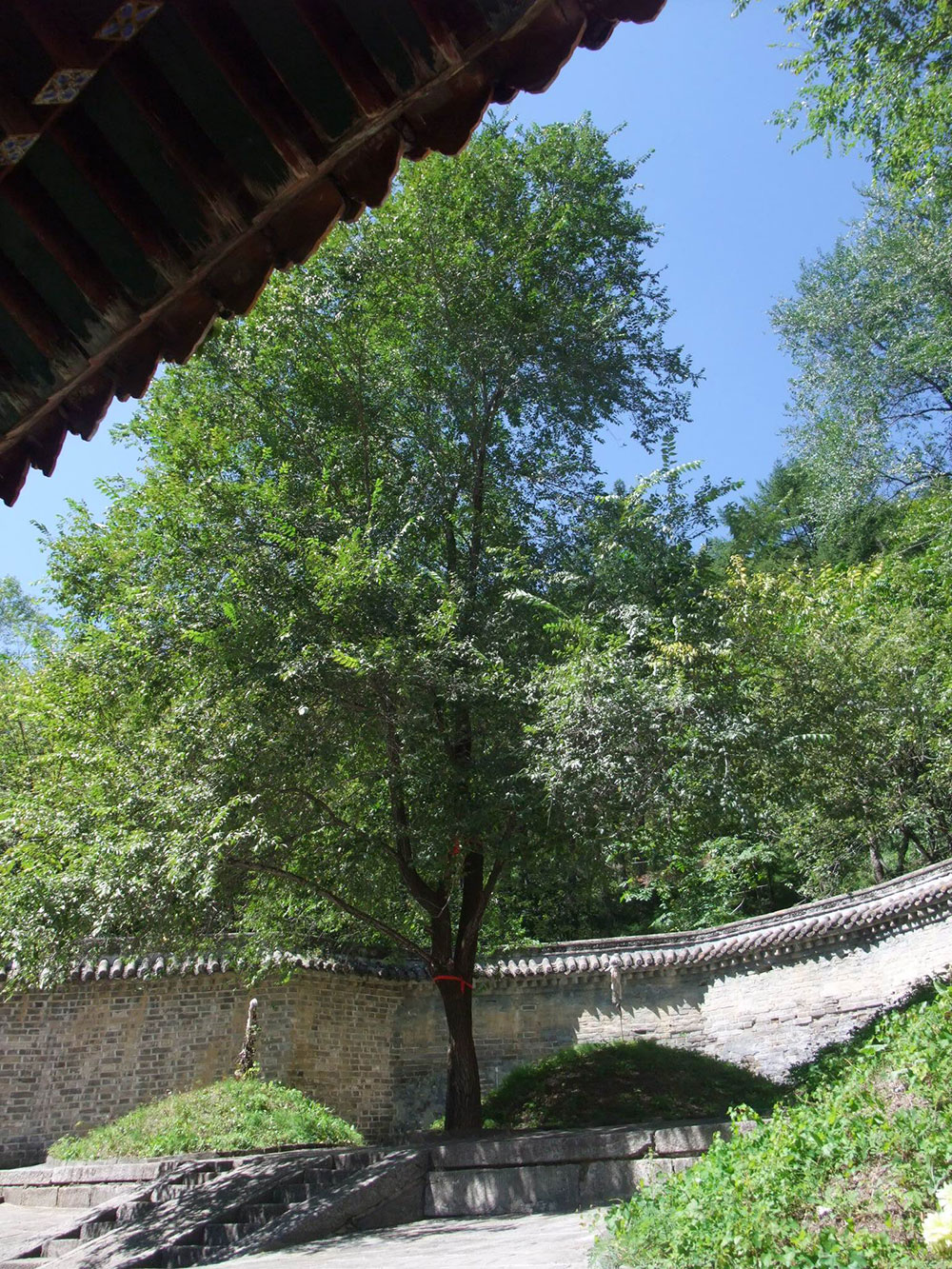

The Yong Mausoleum is the final resting place of Nurhaci (1559-1626) as well as his fathers, uncles, grandfather, great grandfather, and ancestors. It is also regarded as the place that catapulted the prosperity of the Qing dynasty. Inside the mausoleum is the Hall of Prosperity Initiation, behind which is an elm tree. Said tree was later named the nation-protecting sacred tree in 1754.

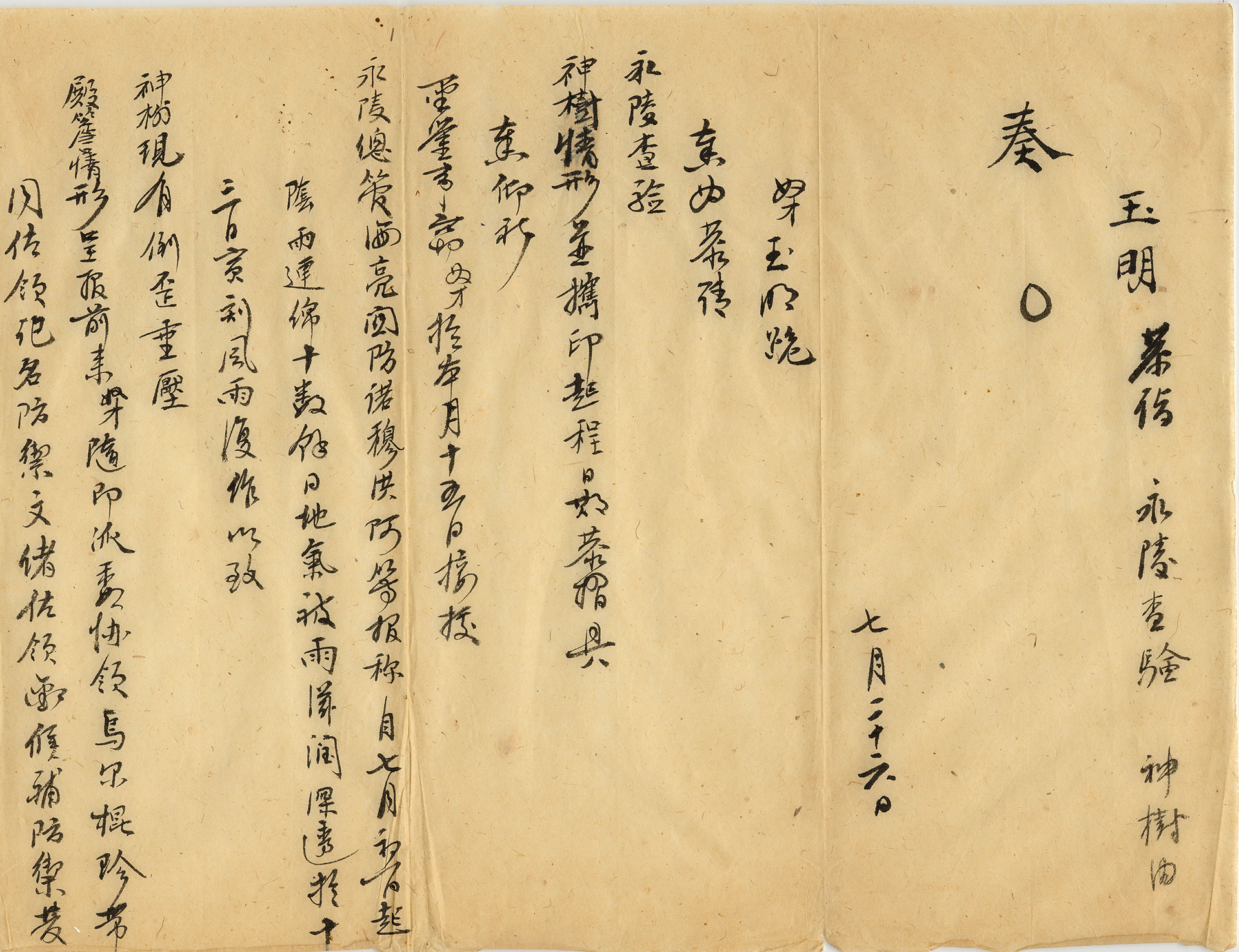

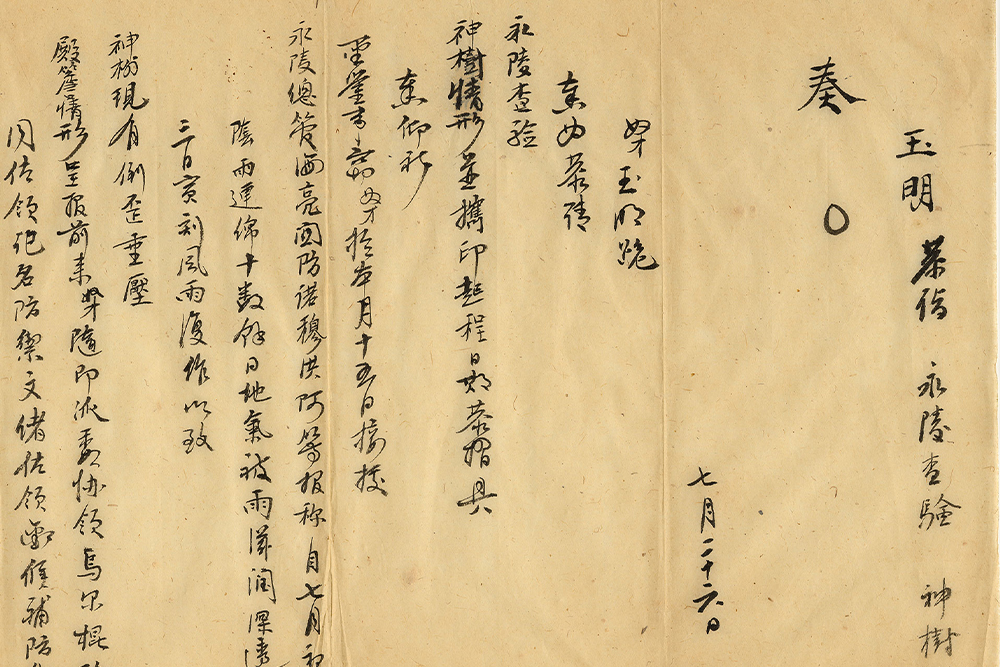

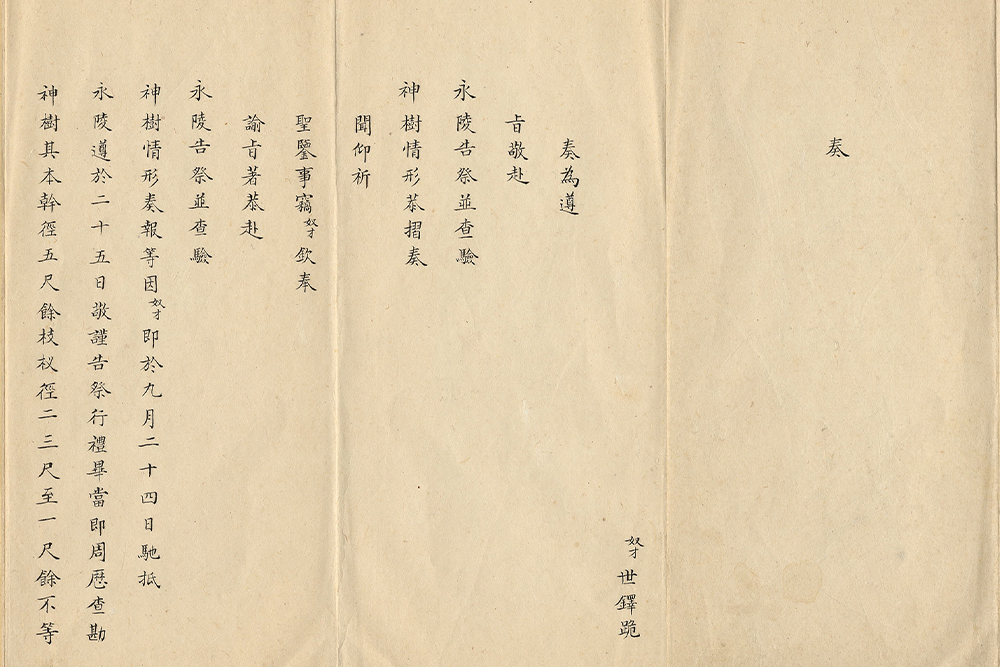

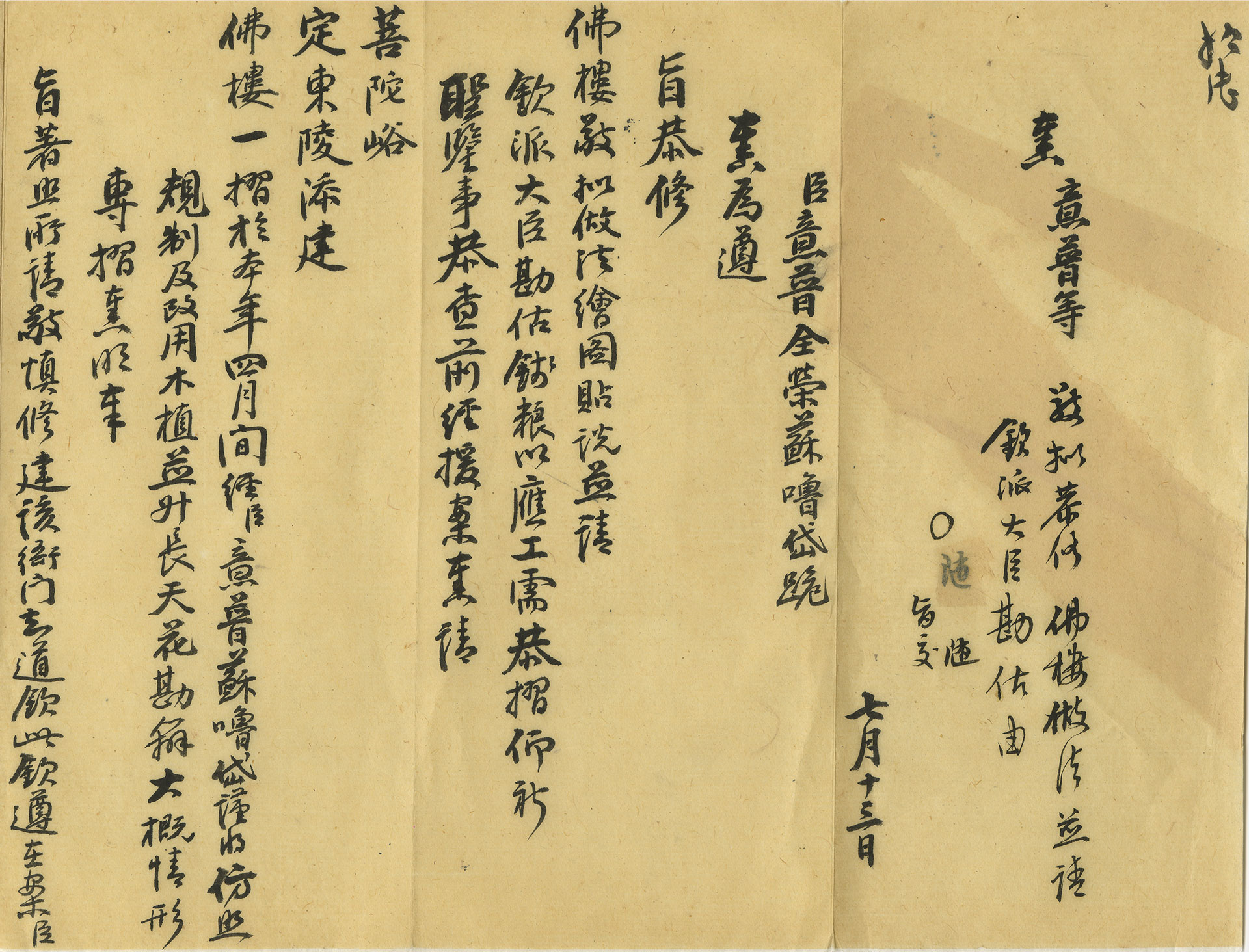

In July 1863, the aforementioned elm tree behind the Hall of Prosperity Initiation in Yongling was blown down by the wind, causing the roots to become exposed and the trunk to tilt and rest on the eaves of the hall. Because this was a bad sign for the fate of the Qing dynasty, Yu Ming (1808-1867), the General of Shengjing, immediately reported to Empress Dowagers Ci’an and Cixi in Beijing. The empress dowagers instantly ordered that Yu Ming take extra precautions and sent Imperial Commissioner Ji Pu (1793-1867) to Shengjing to investigate the matter. During the investigation, professional craftsmen responsible for the construction of imperial Qing architecture successively drew the tree tilting situations and proposed in the drawings various tree protection suggestions for the empress dowagers to consider.

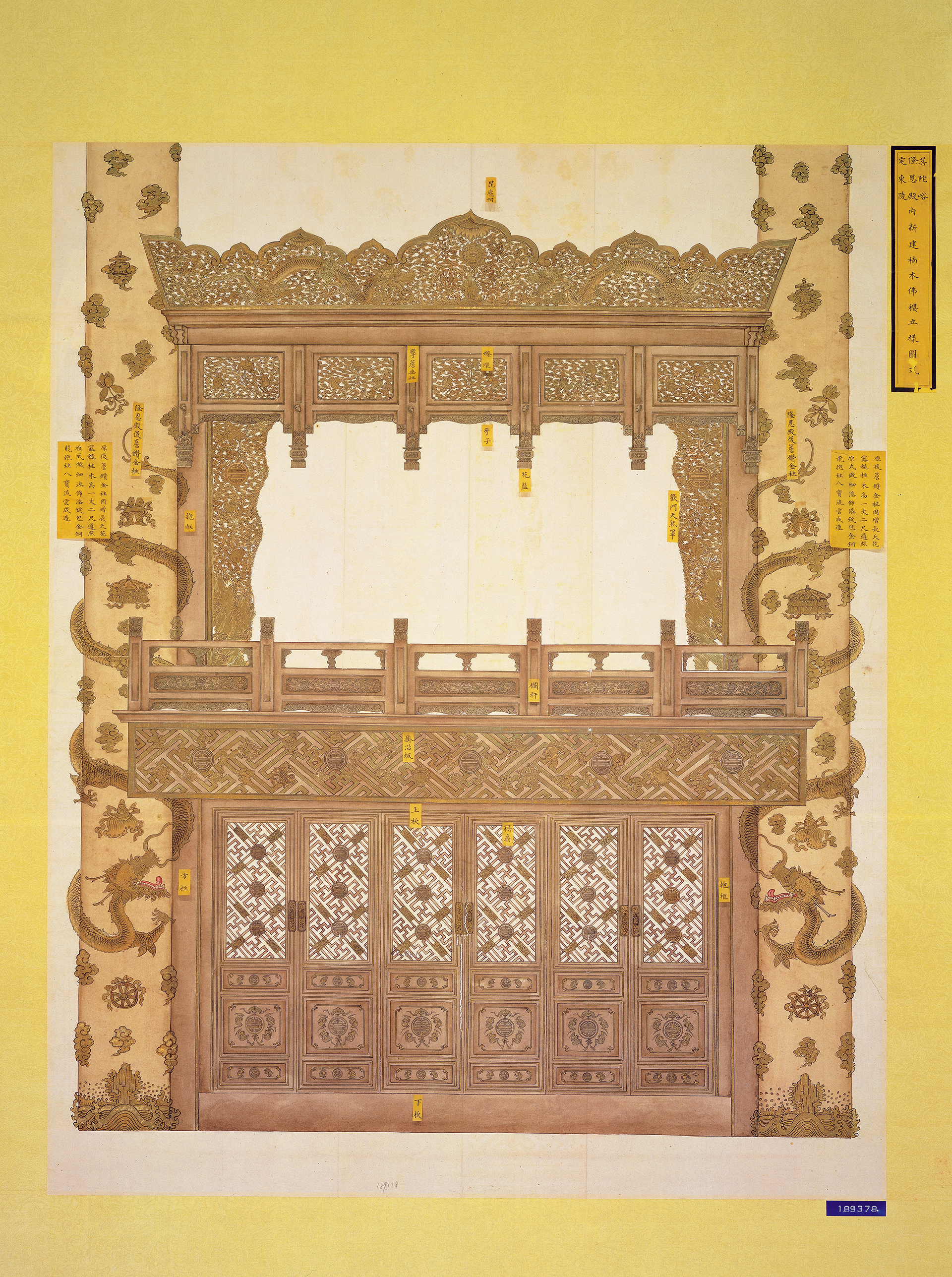

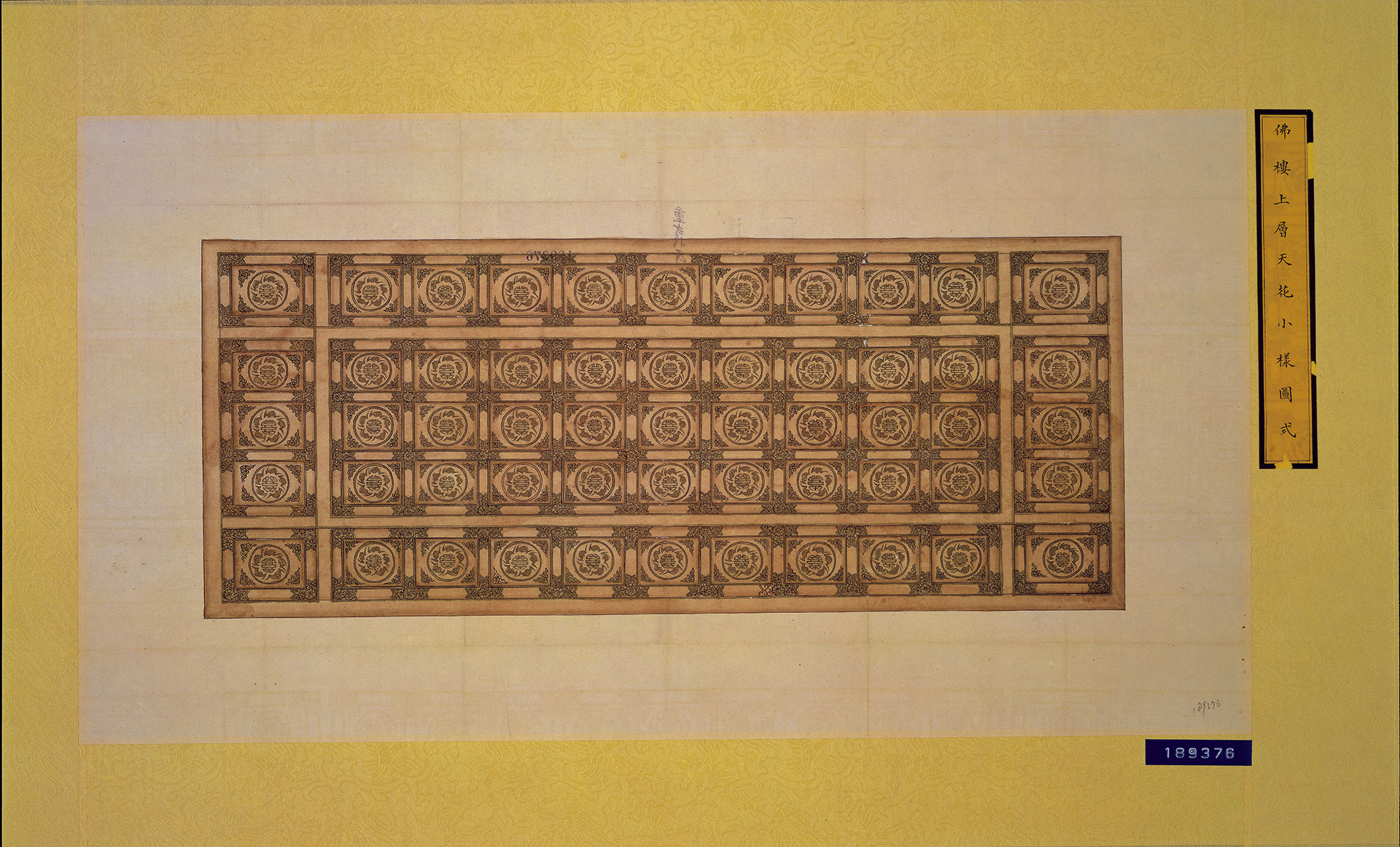

- Decoration Drawings of the Hall of Enormous Grace, Ding East Mausoleum

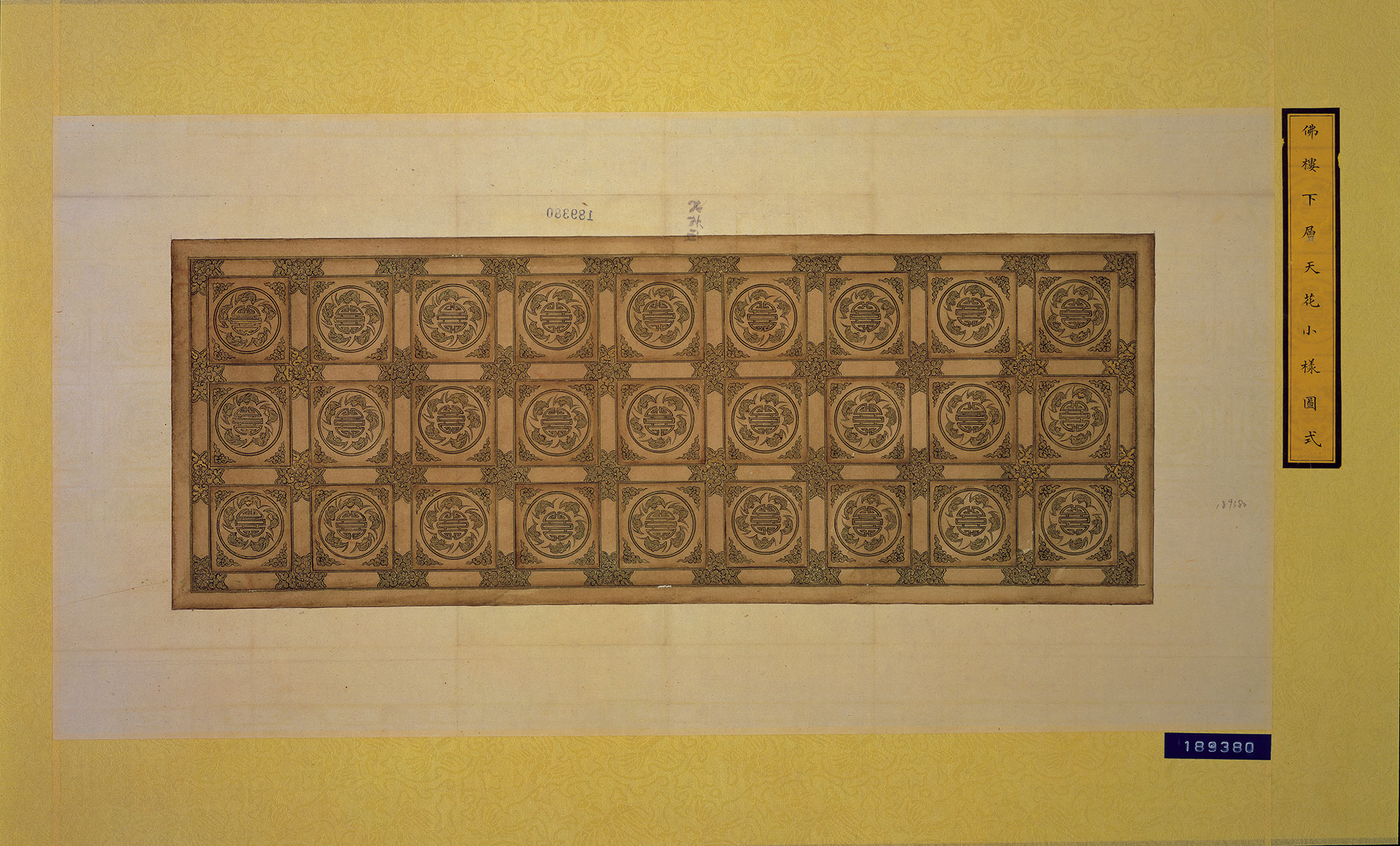

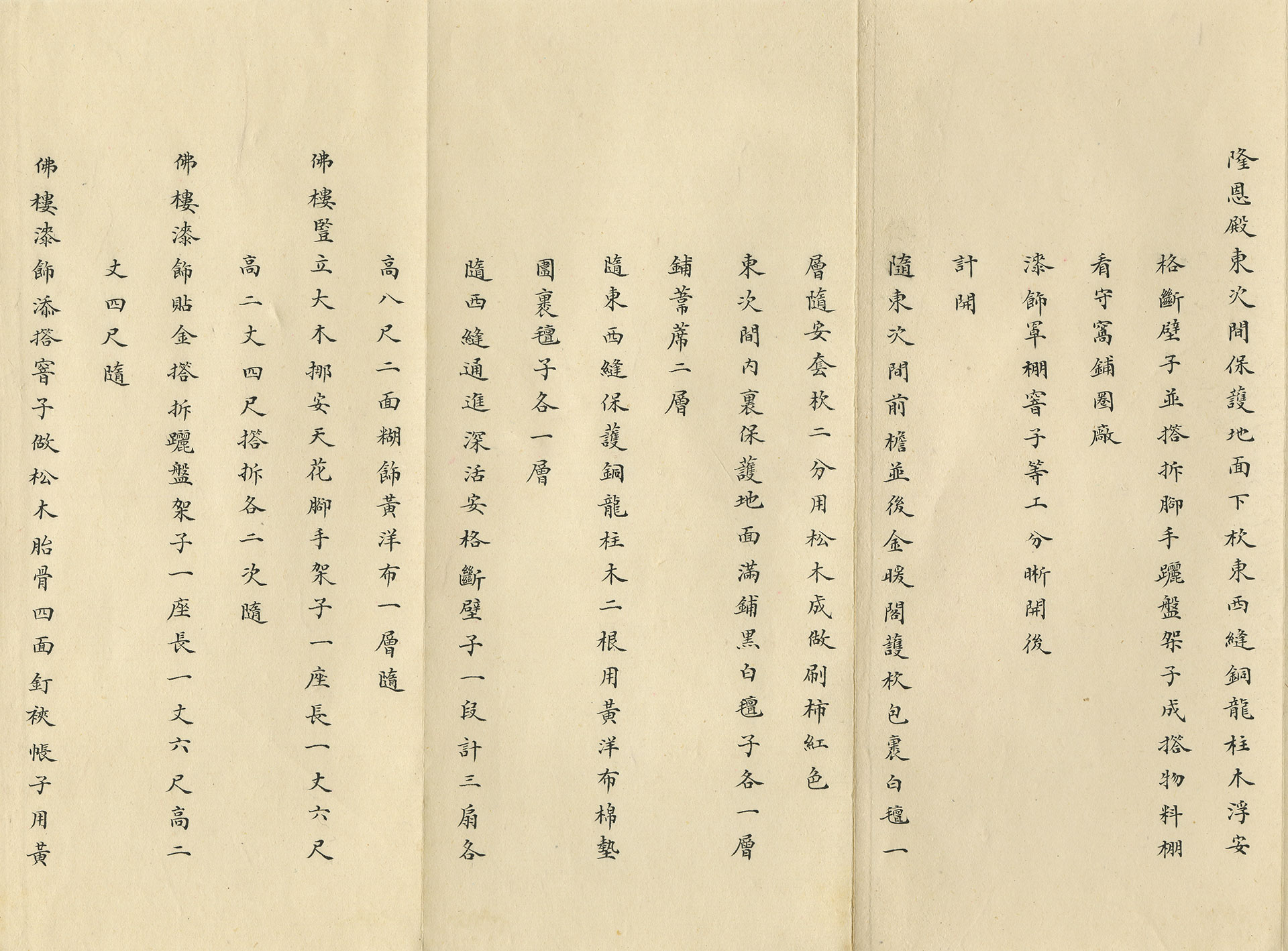

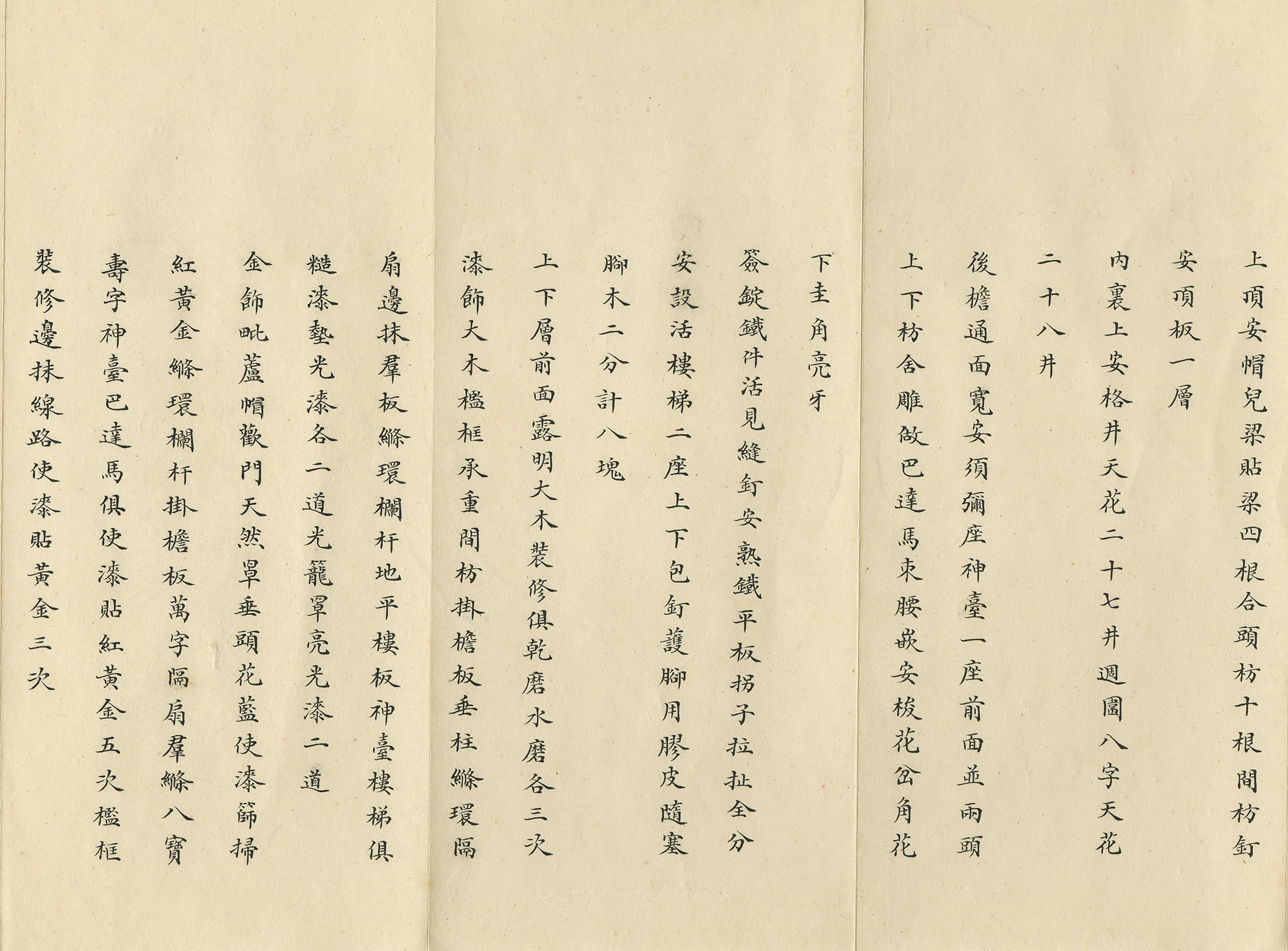

Emperor Xianfeng (1831-1861, reigned 1851-1861) was buried in the Ding Mausoleum, whereas Empress Dowager Cixi was buried in the Putuoyu Ding East Mausoleum east of the Ding Mausoleum. The Hall of Enormous Grace (inside the Ding East Mausoleum), also called the Sacrificial Hall, was where sacrifices were offered to gods and ancestors.

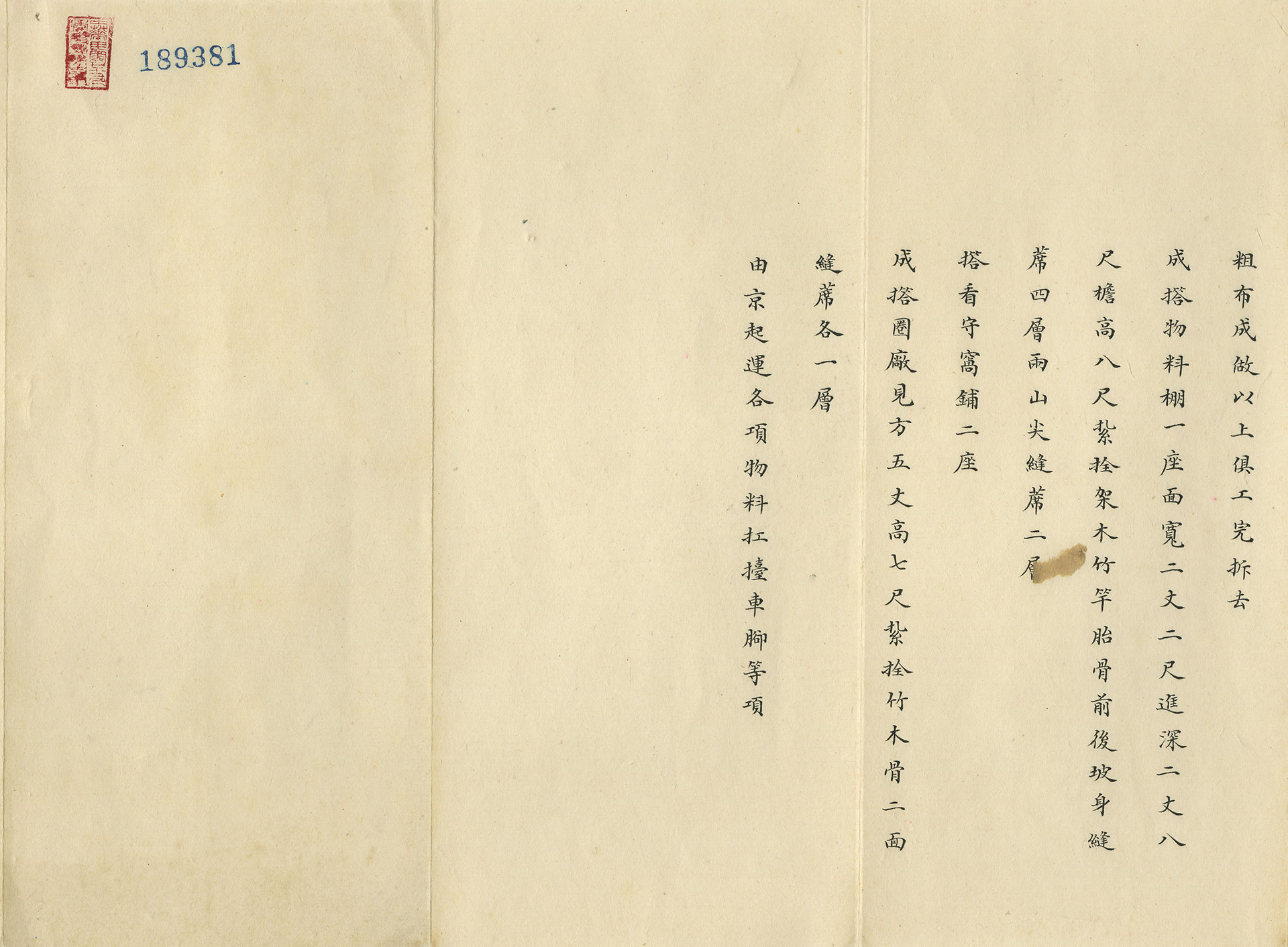

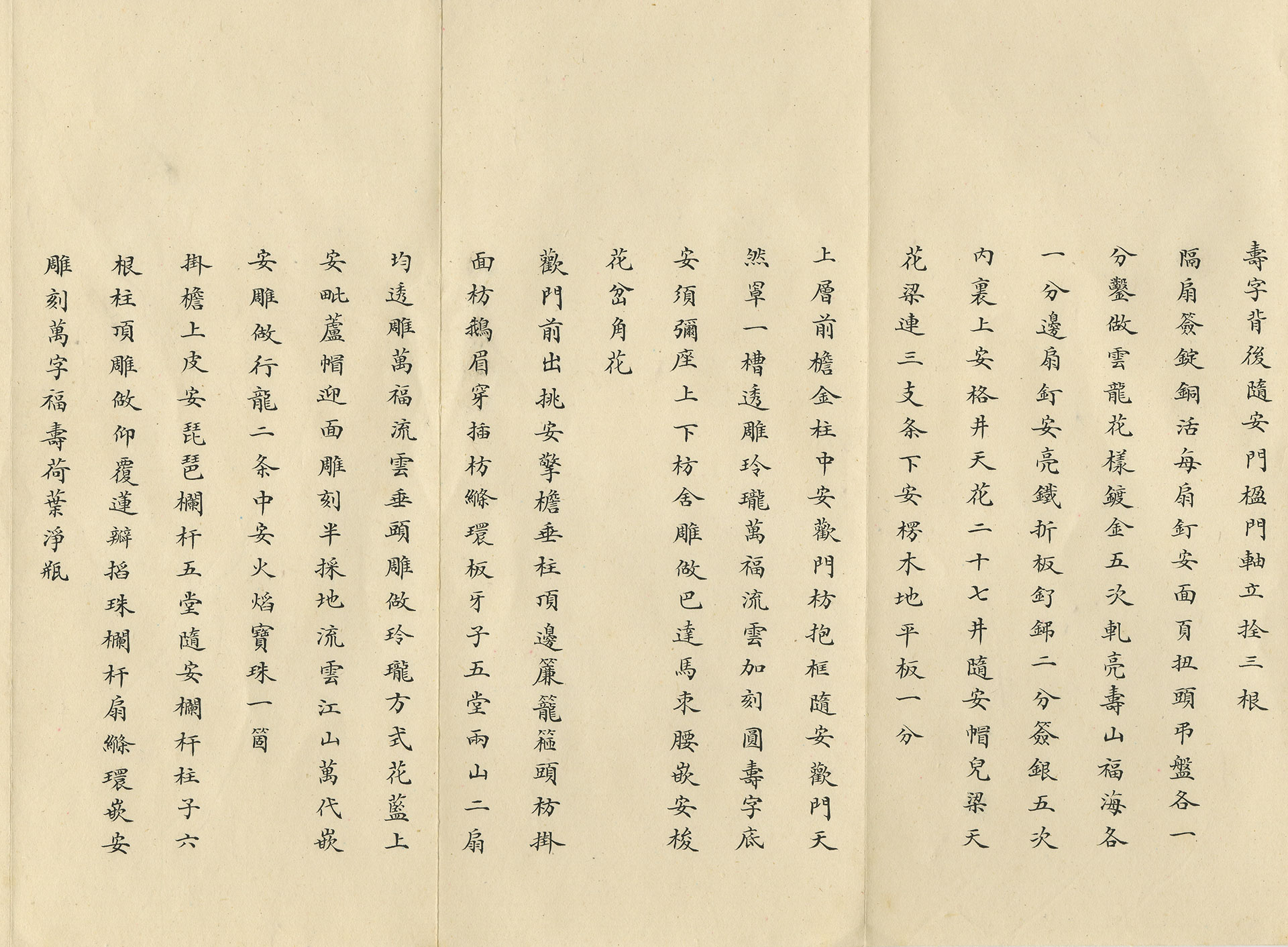

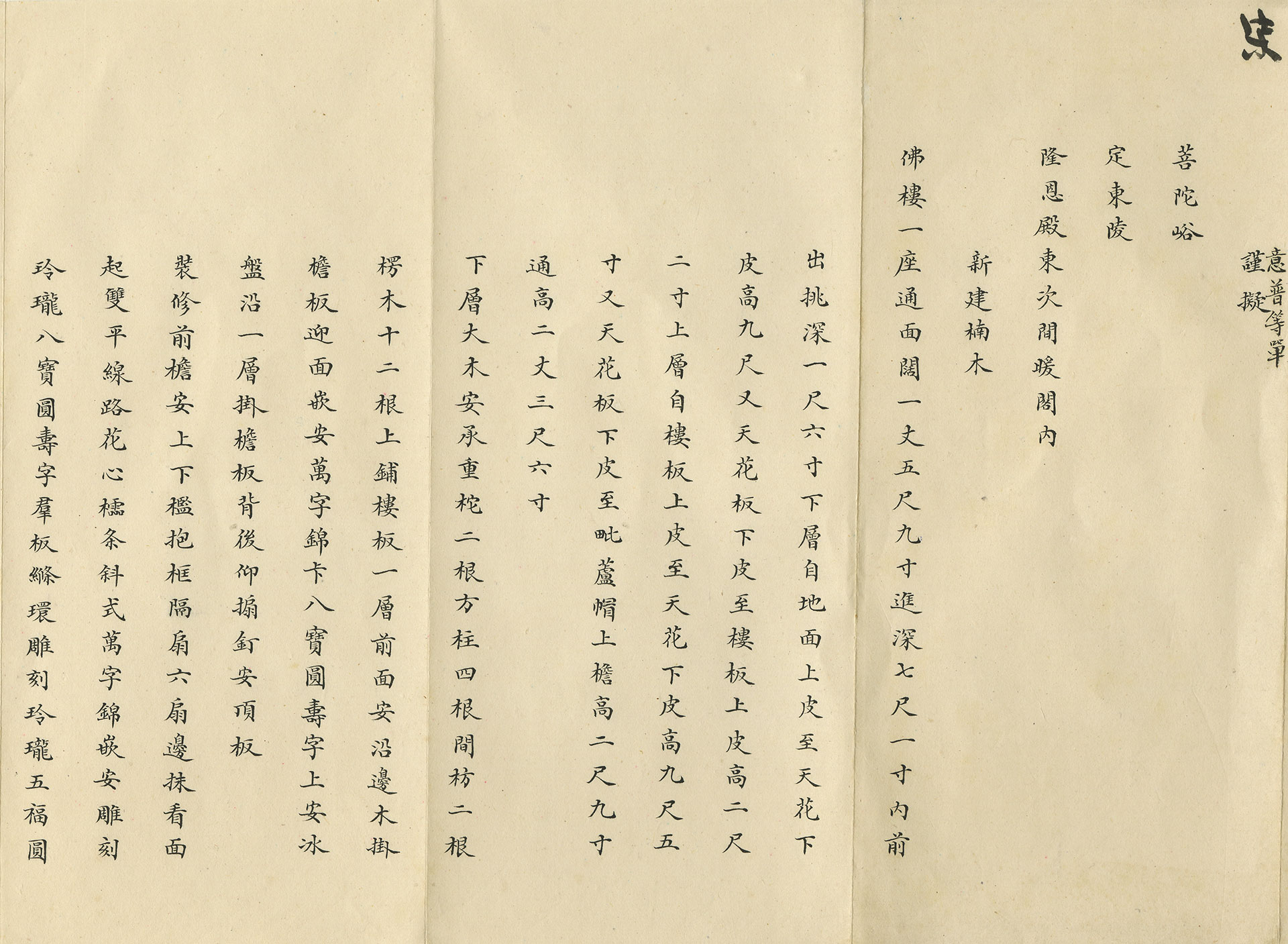

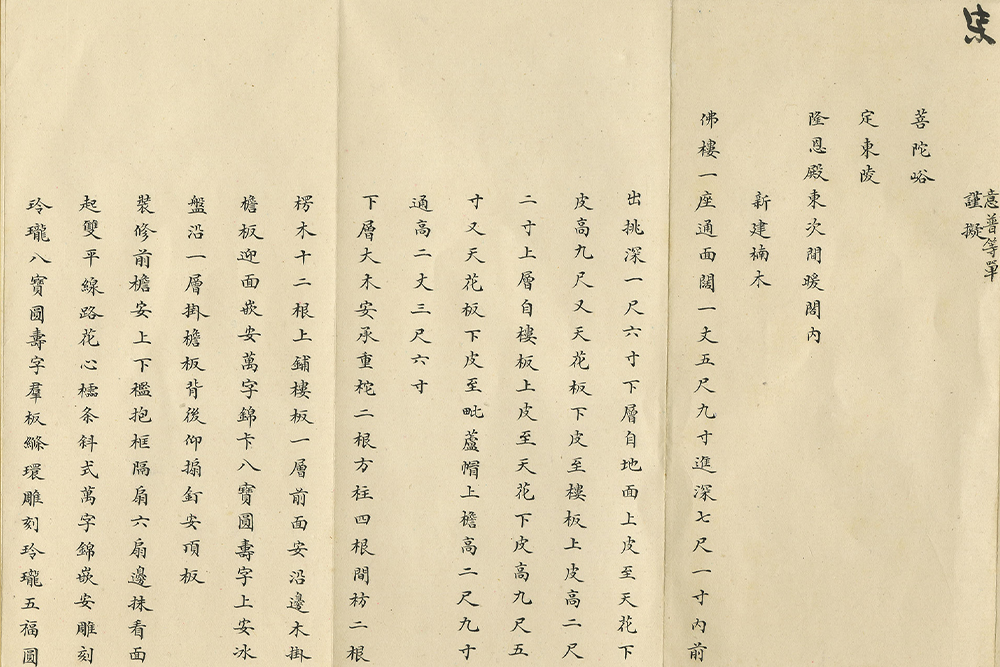

The construction of Ding East Mausoleum, which began in 1873 and ended in 1879, costed more than 2 million taels of silver. In 1895, the mausoleum was revamped pursuant to an imperial decree. The scale and magnificence of the Ding East Mausoleum was second only to Emperor Qianlong’s Yu Mausoleum. As Yi Pu (1868-?), the guardian of the East Mausoleum in the late-Qing dynasty, described, “The Ding East Mausoleum boasts majestic and magnificent halls and widely different construction craftsmanship.” In 1909, the Qing court decided to renovate the East Warmth Chamber of the Hall of Enormous Grace, add the Chinese Cedar Buddha Pavilion, and raise the ceiling of the original hall. The artifacts demonstrated here are the construction design drawings submitted by the officials who participated in the construction at the time. By looking closely at these drawings, visitors will be amazed by the meticulous and exquisite drawing skills of the palace architects.

- Tall Buildings in Front of the Emperors' Tombs in the Taidong Mausoleum

Starting the Emperor Yongzheng era (1723-1735) in the Qing dynasty, emperors and their sons were buried separately in eastern and western mausoleums, a practice called the “emperor burial system.” Emperor Yongzheng was buried in the Tai Mausoleum (in the Western Qing Mausoleum), whereas Empress Xiaoshengxian (Empress Dowager Chongqing, 1692-1777) was buried in the Taidong Mausoleum (in the Eastern Qing Mausoleum), the mausoleum where Emperor Qianlong’s biological mother was buried.

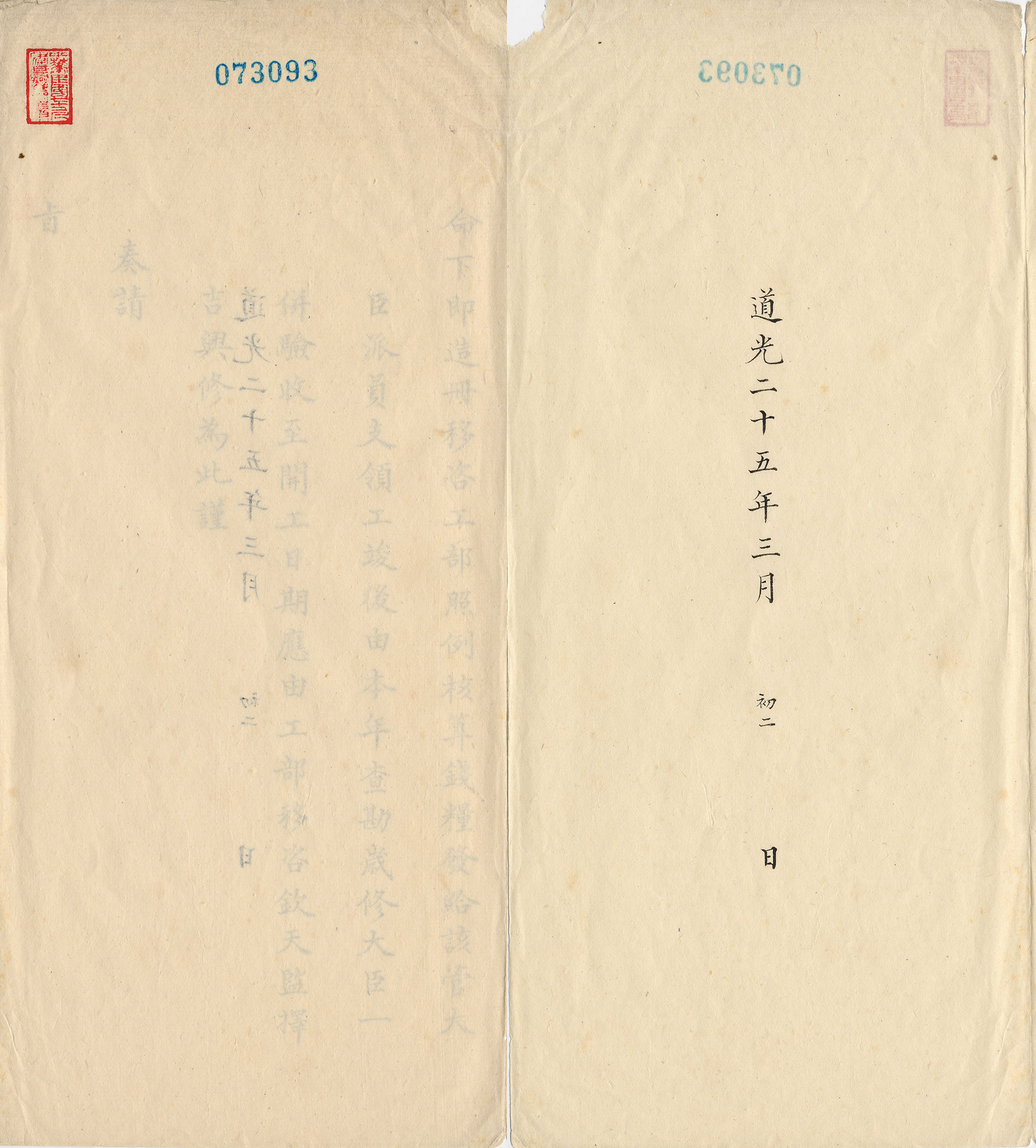

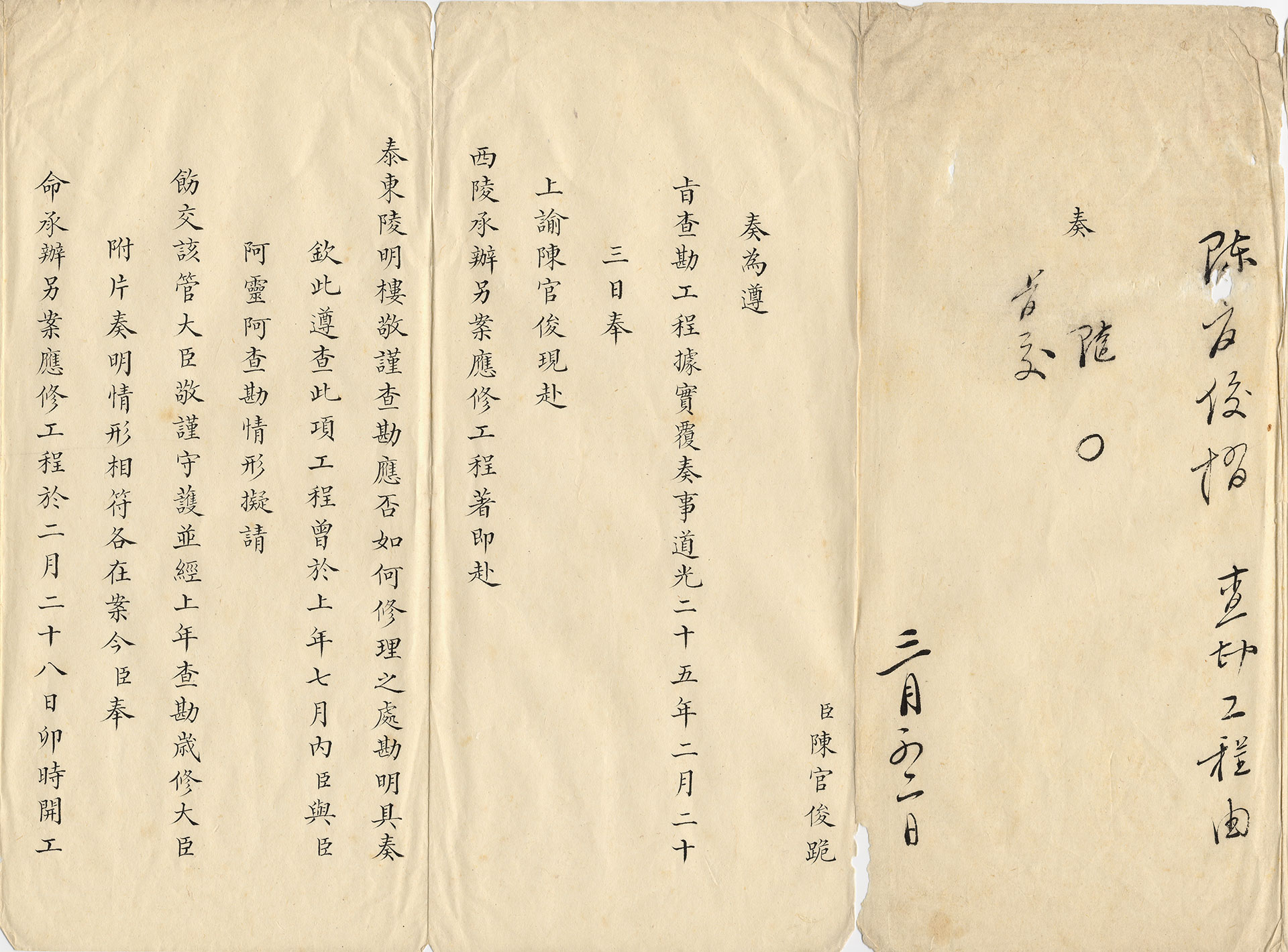

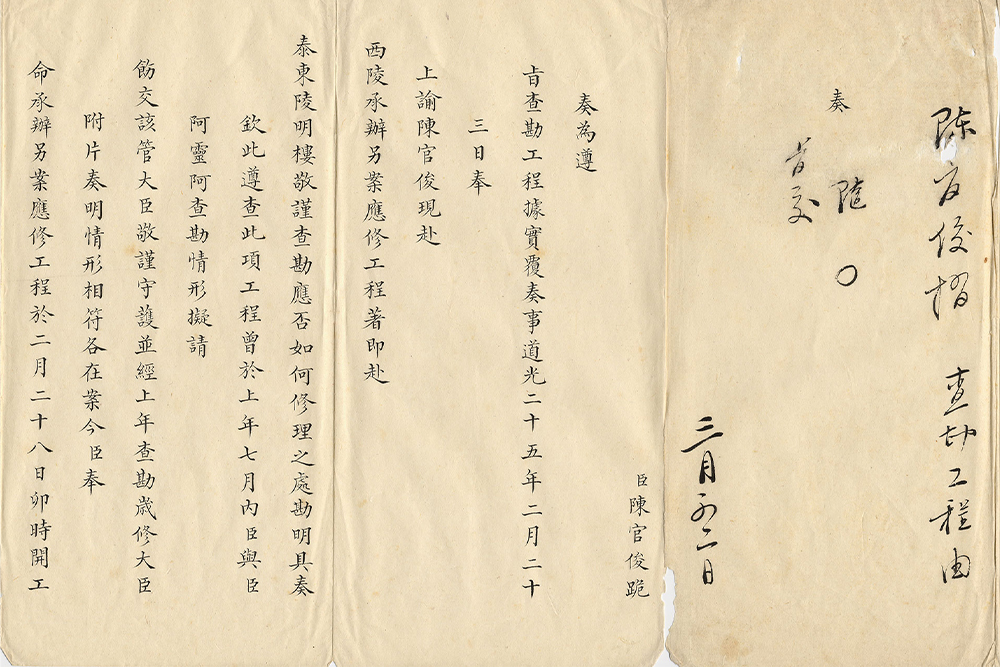

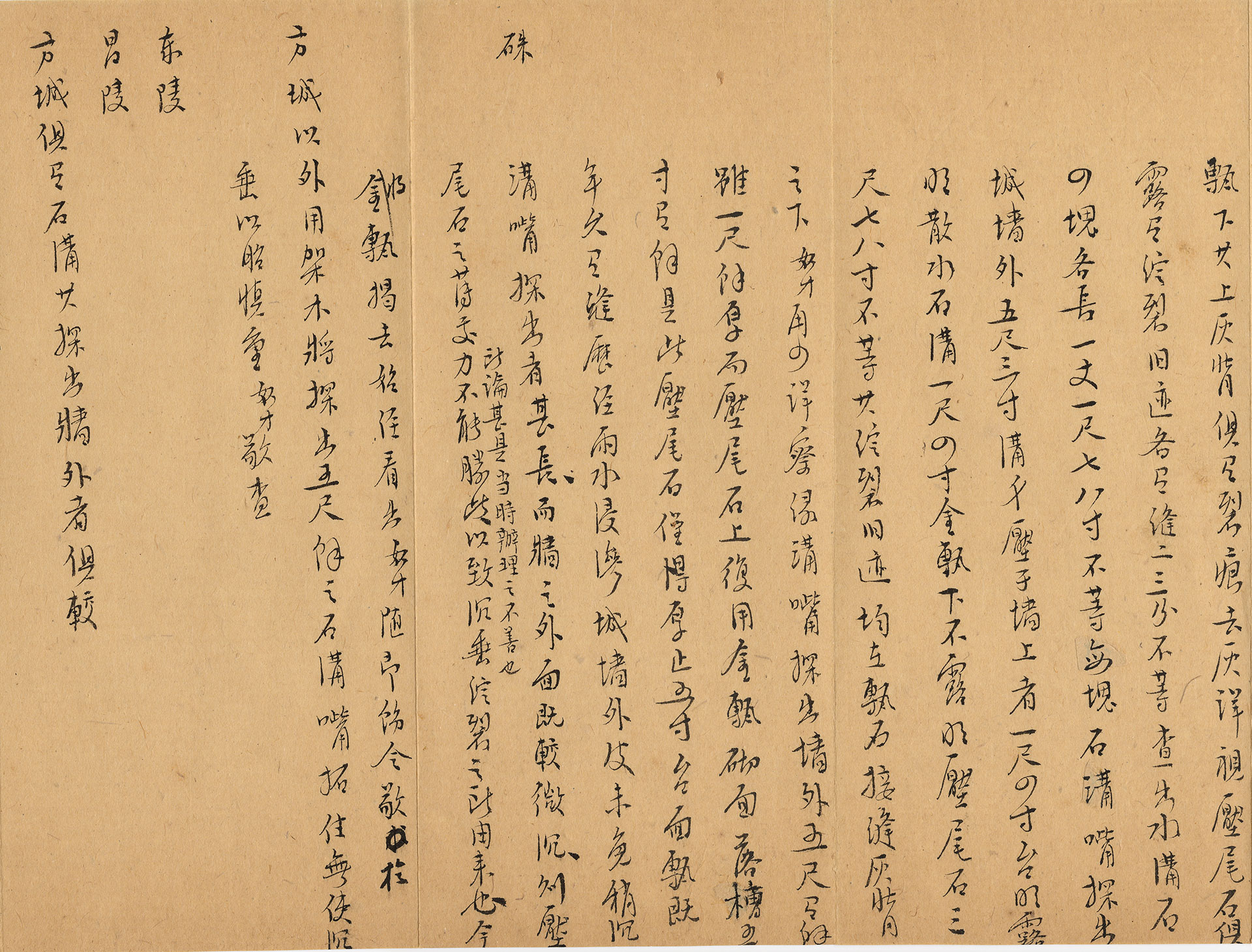

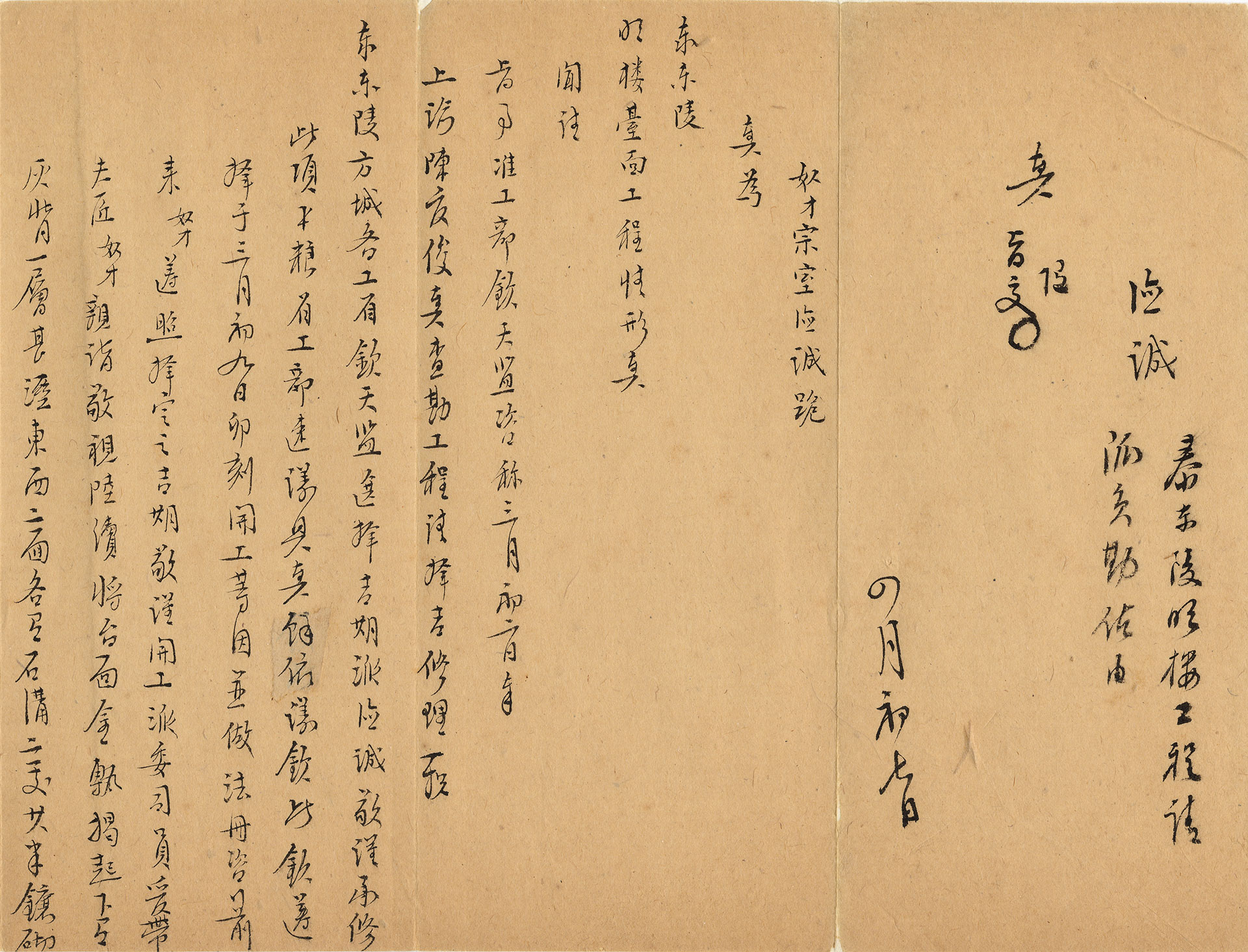

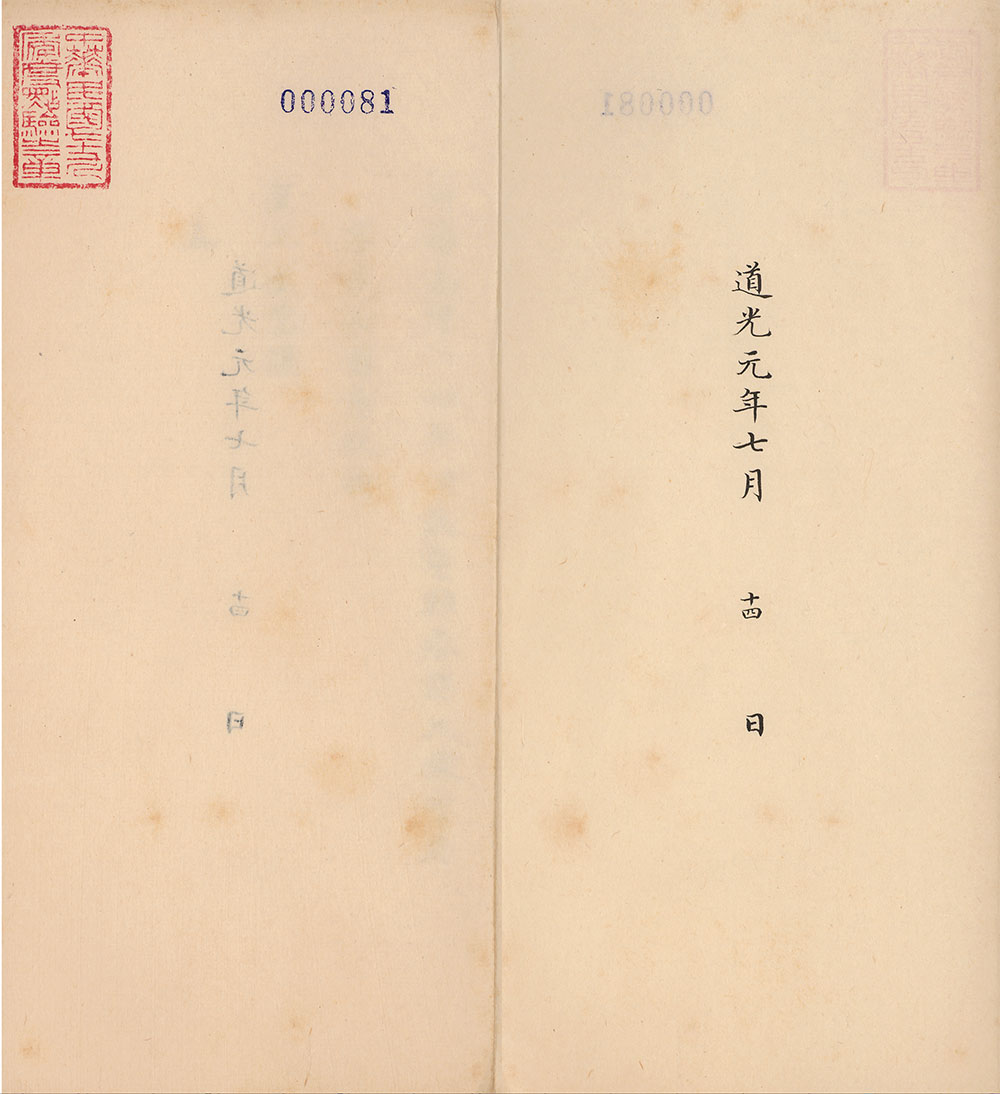

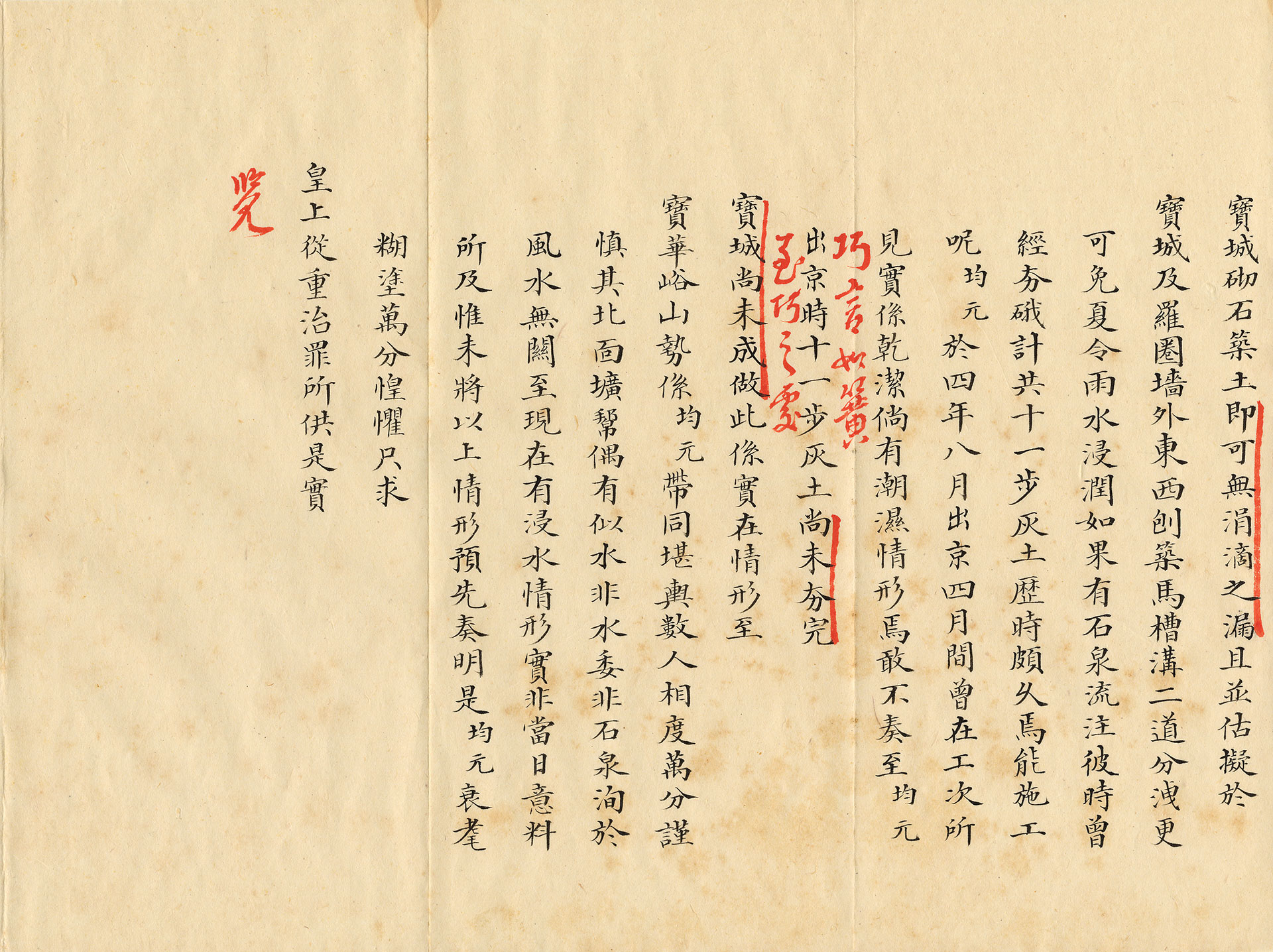

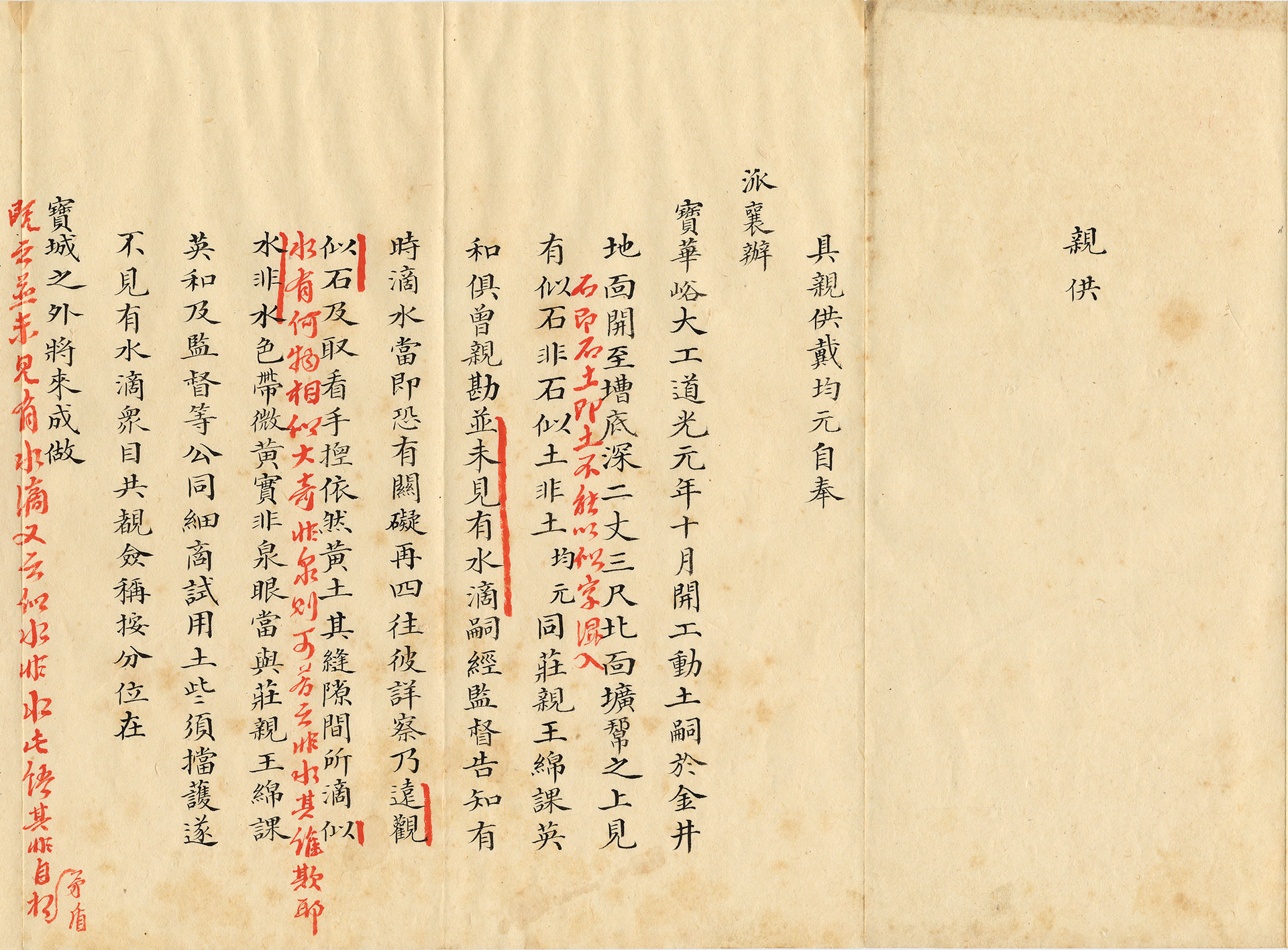

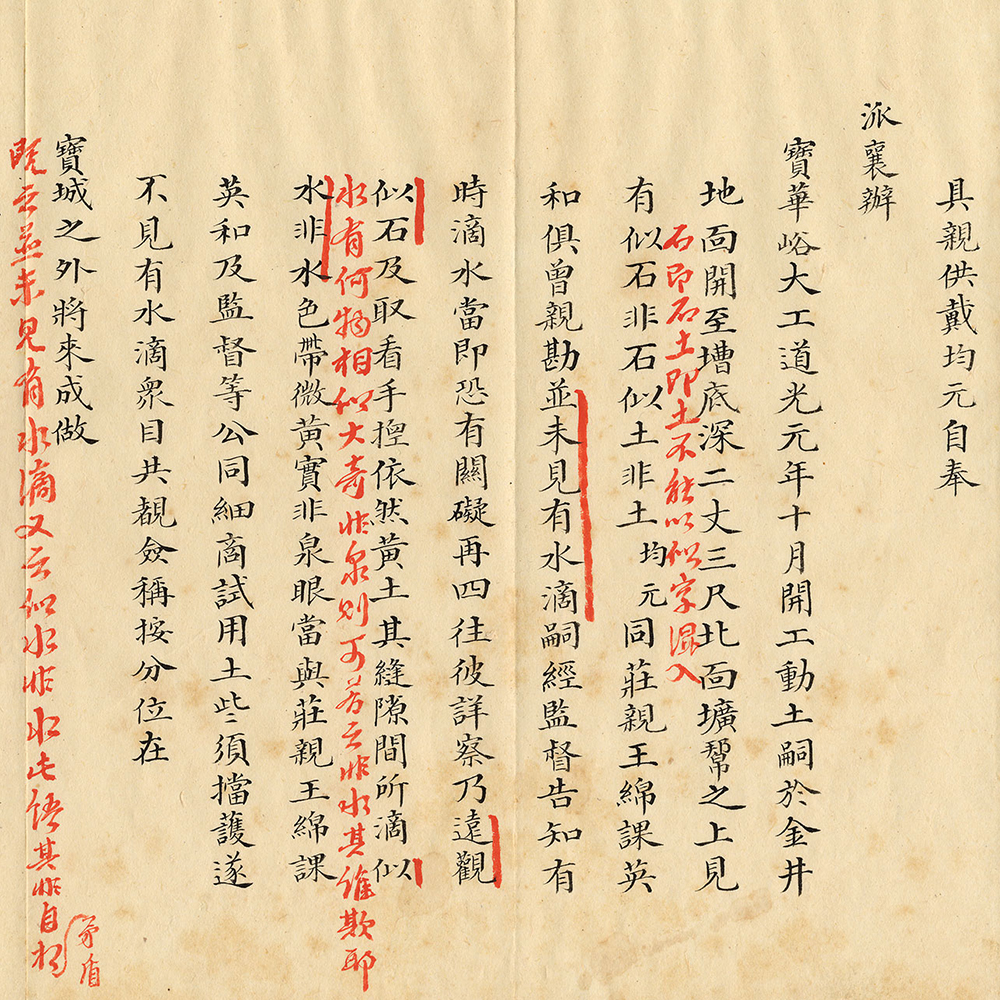

Construction of the Taidong Mausoleum began in 1737 and ended in 1743; it was first used in 1777. The main buildings in the mausoleum included the Hall of Enormous Grace, east and west auxiliary halls, main hall, square city, and tall buildings in front of the emperors’ tombs. The innermost part of the mausoleum was a treasure city and round wall tops. Beneath the round wall tops was the underground palace, which was the largest of the three empress tombs in the Western Qing Mausoleum. After the completion of the Taidong Mausoleum, the mausoleum had undergone repairs several times. In 1845, Chen Guanjun (?-1849), the Minister of Personnel, went to the Western Qing Mausoleum for an initiation project and was ordered to also investigate the mausoleum itself. Chen found cracks and leaks in the tall buildings in the front of the emperors’ tombs. Emperor Daoguang subsequently ordered imperial clan member De Cheng (?-1850) and others to undertake the repairs. Later, imperial family craftsmen affiliated with the Imperial Household Department submitted drawings of their survey results following the repairs.

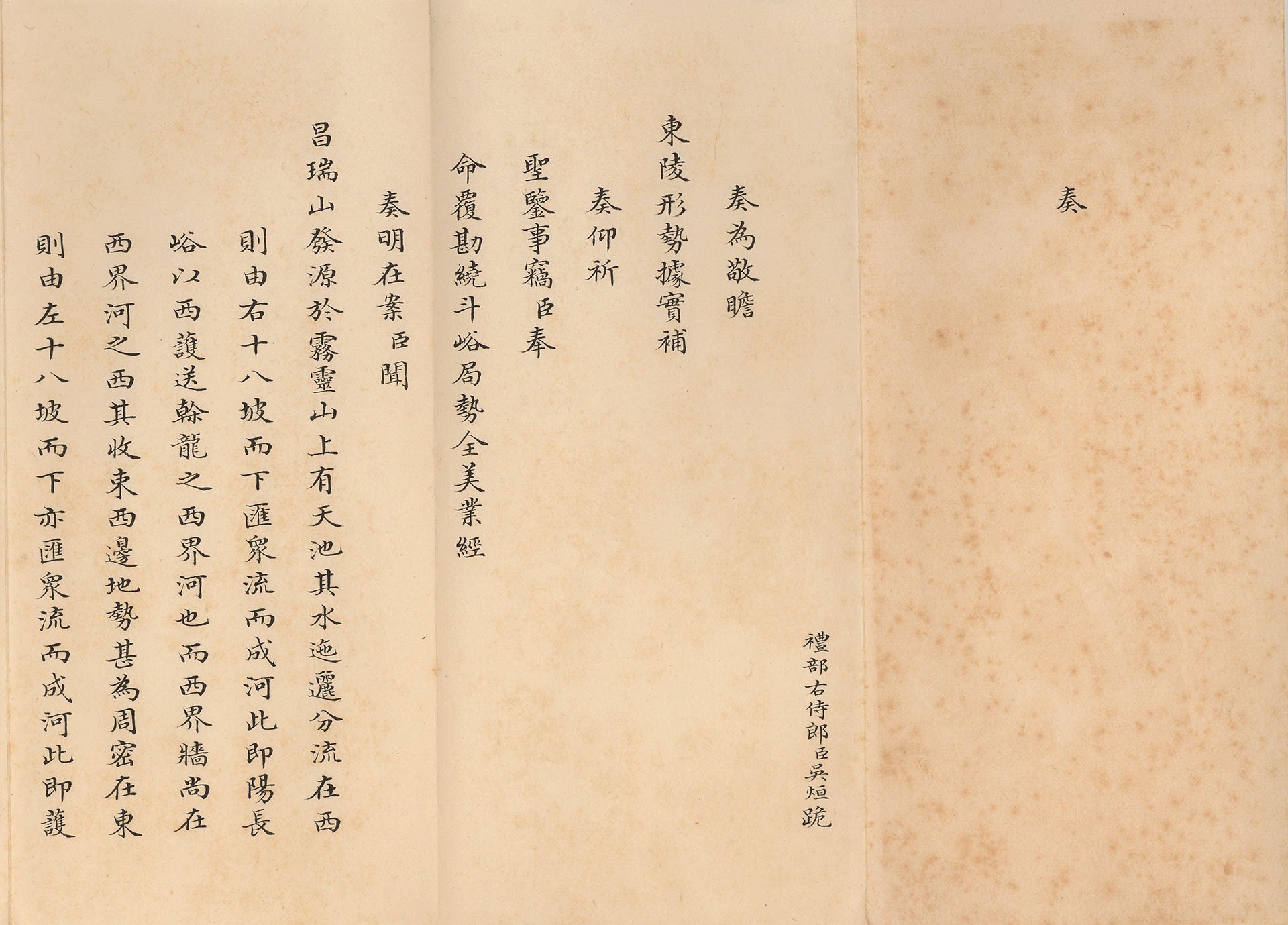

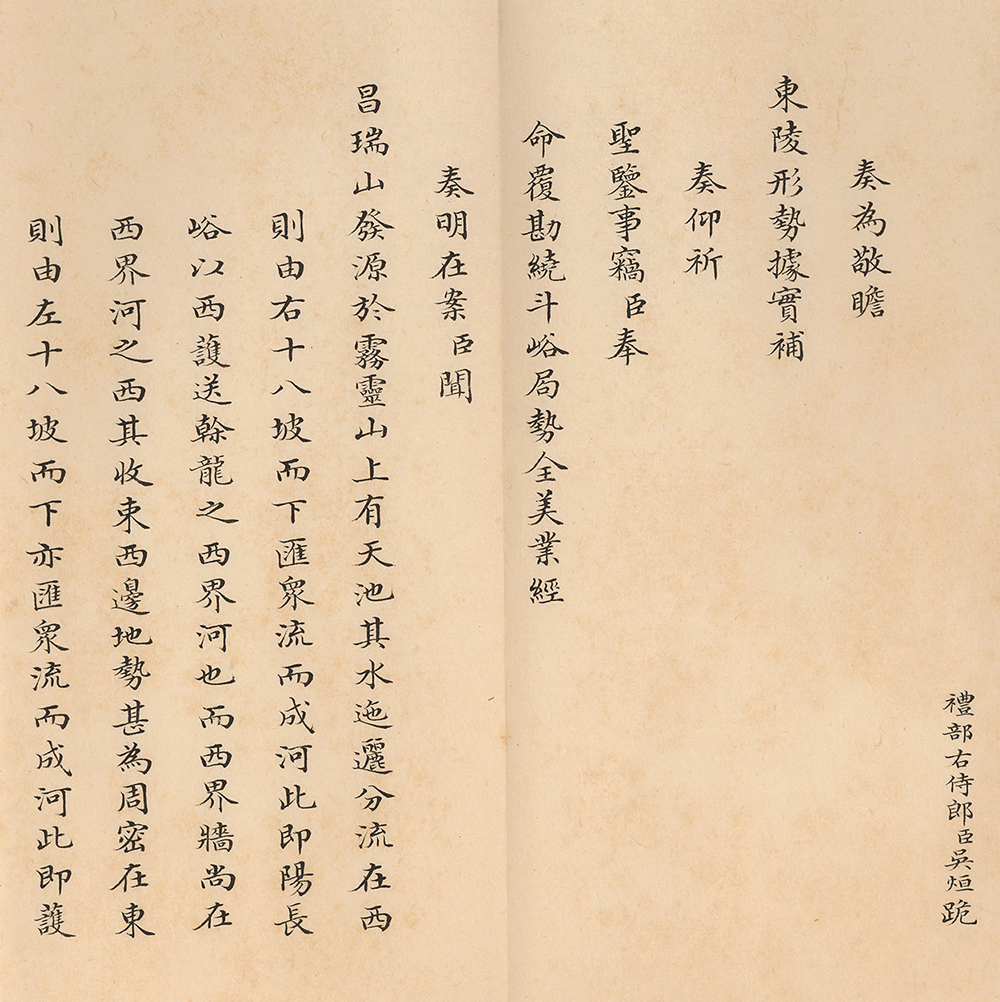

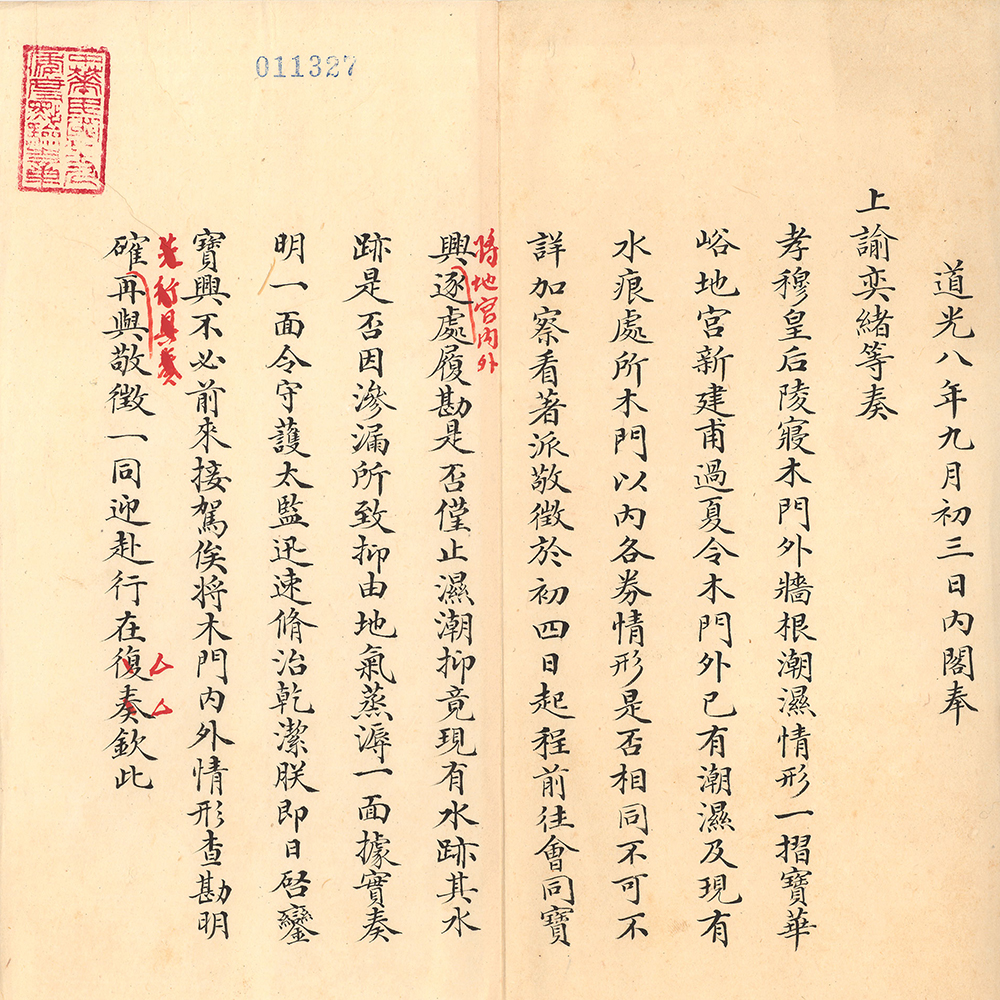

When Emperor Daoguang (reign: 1821-1850) ascended the throne, he immediately began building his mausoleum. Because of the emperor burial system proposed by Emperor Yongzheng, where fathers and sons were buried separately, Emperor Daoguang’s mausoleum was to be in the Eastern Qing Mausoleum. Accordingly, he chose Baohuayu (initially called “Raodouyu,” which was renamed “Baohuayu” during Emperor Daoguang’s reign) as the location for the Eastern Qing Mausoleum to last for tens of thousands of years.

Construction of the mausoleum was completed in 1827, after which Empress Xiaomu (1781-1808) was moved there. Unexpectedly, the underground palace experienced subsequent flooding. Emperor Daoguang was furious upon hearing the news, censuring his officials for being unconscionable and sentencing relevant officials to punishments including confiscating their properties, dismissing them from their posts, banishing them to army posts, and demoting them.

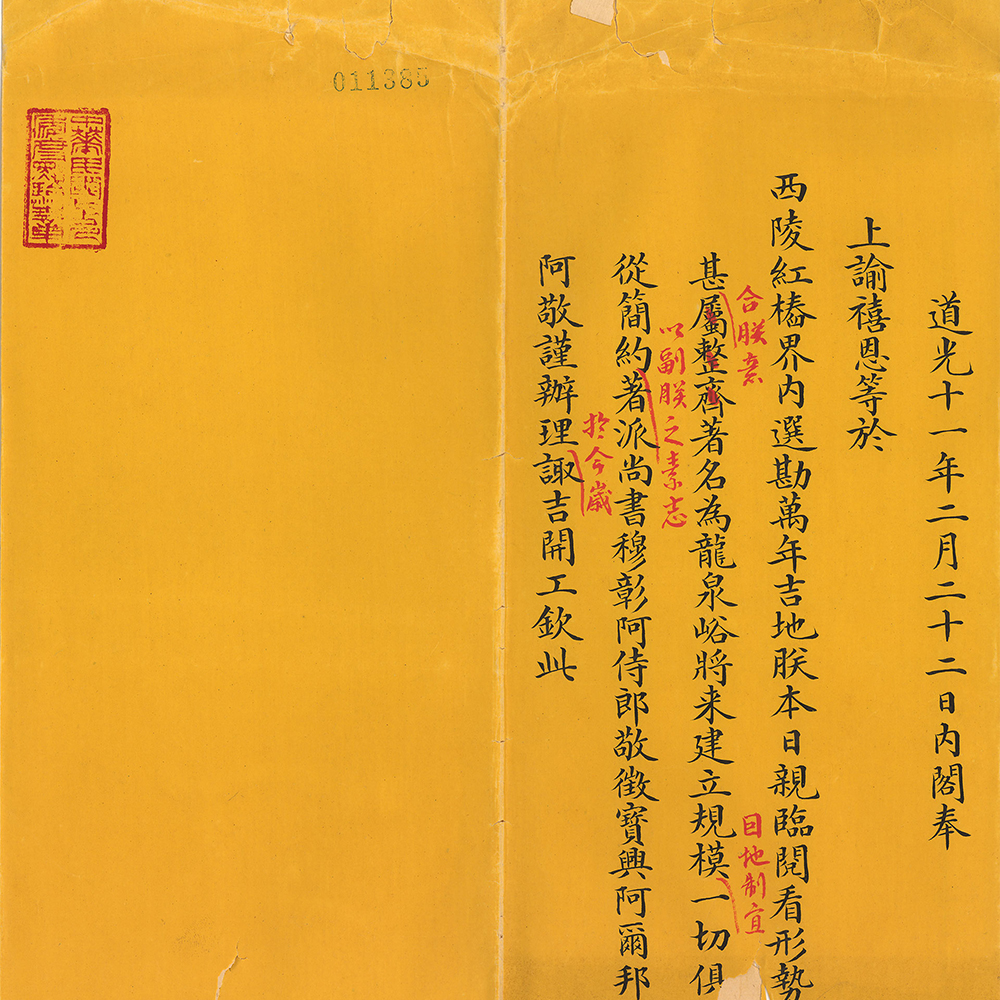

The failed experience of building the mausoleum in Baohuayu made Emperor Daoguang wary about being buried in the Eastern Qing Mausoleum. Despite newly appointed ministers recommending new locations such as Chengziyu and Ping’anyu, which they argued were markedly auspicious, the emperor lacked interest. Finally, after many site surveys performed by imperial clan member Xi En (1784-1852) and others, the emperor finally selected Longquanyu in the Western Qing Mausoleum as his resting place in 1840. During the process of mausoleum relocation, feng shui had to be re-examined, giving birth to the numerous mausoleum topographic maps drawn by imperial Qing architects (and submitted to the emperor to review) that we see here.