Imperial Architectural Drawings

In the Qing Dynasty, the construction, expansion, and interior decoration of imperial palaces, the capital city, altars, temples, imperial mausoleums, gardens, and mansions were all under the jurisdiction of the "Ministry of Works", overseen by the "Imperial Household Department", and managed by the "Construction Bureau" (Imperial Commission Construction Bureau). This bureau was composed of trusted high-ranking officials appointed by the emperor and was responsible for coordinating design institutions for various projects.

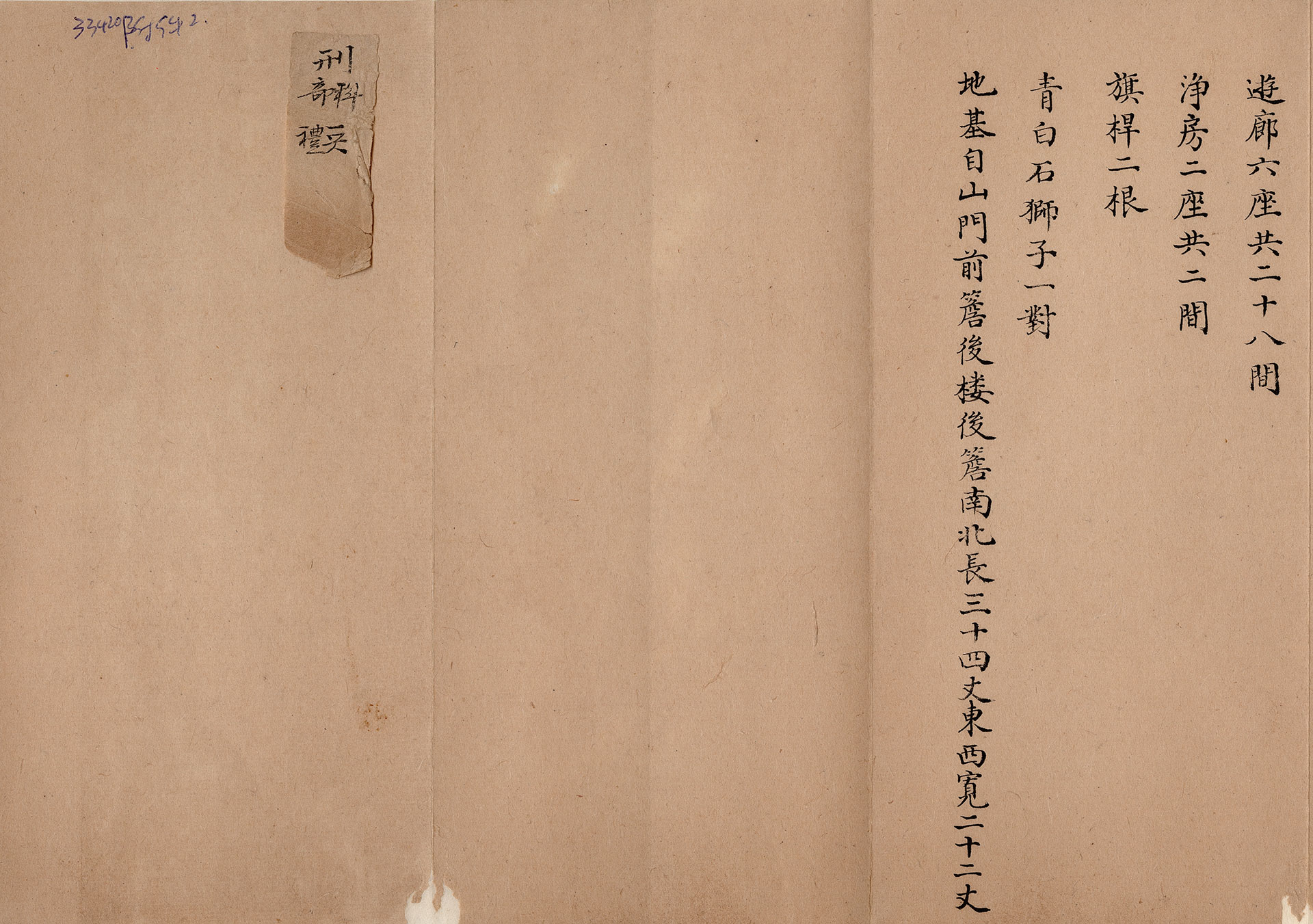

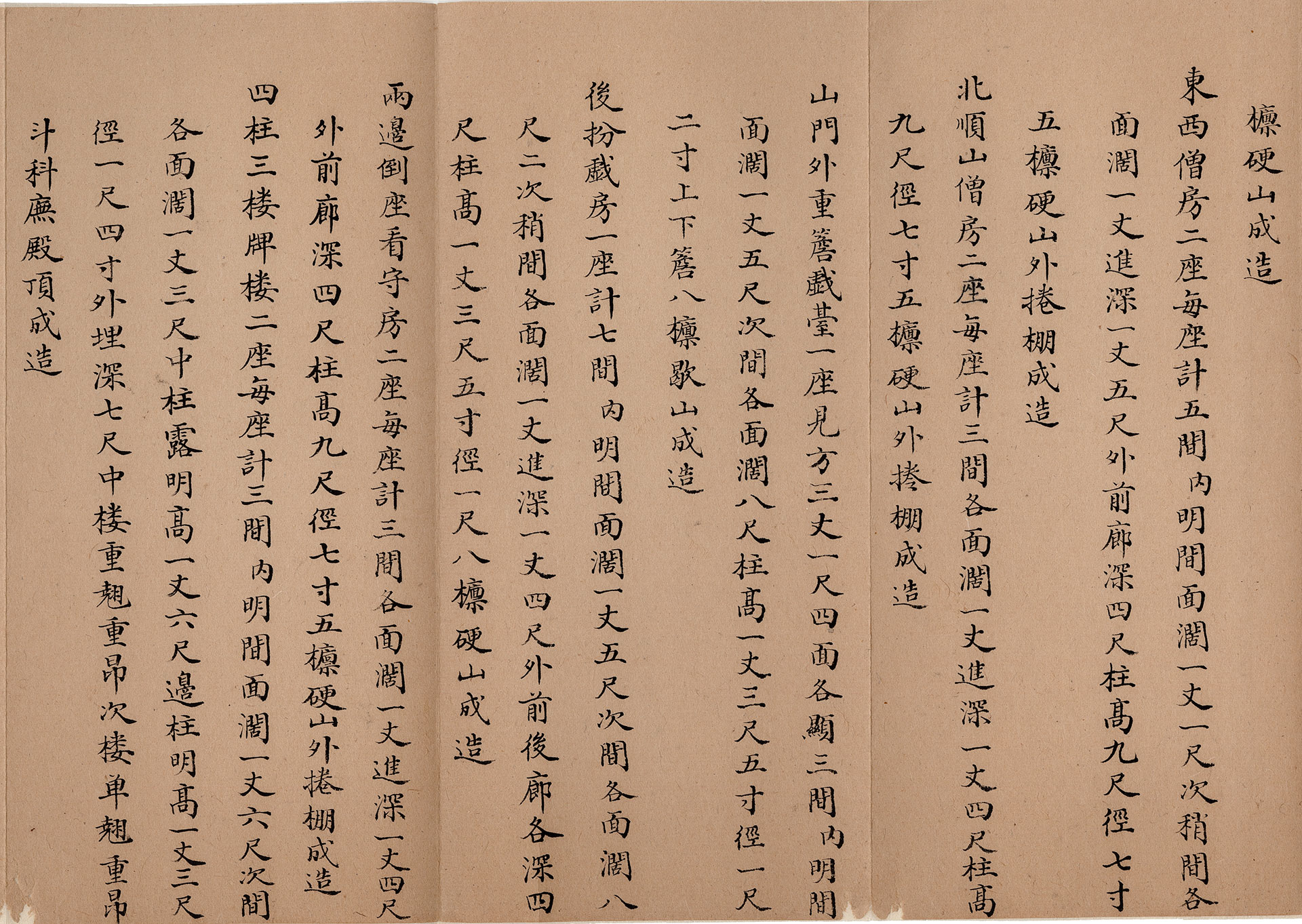

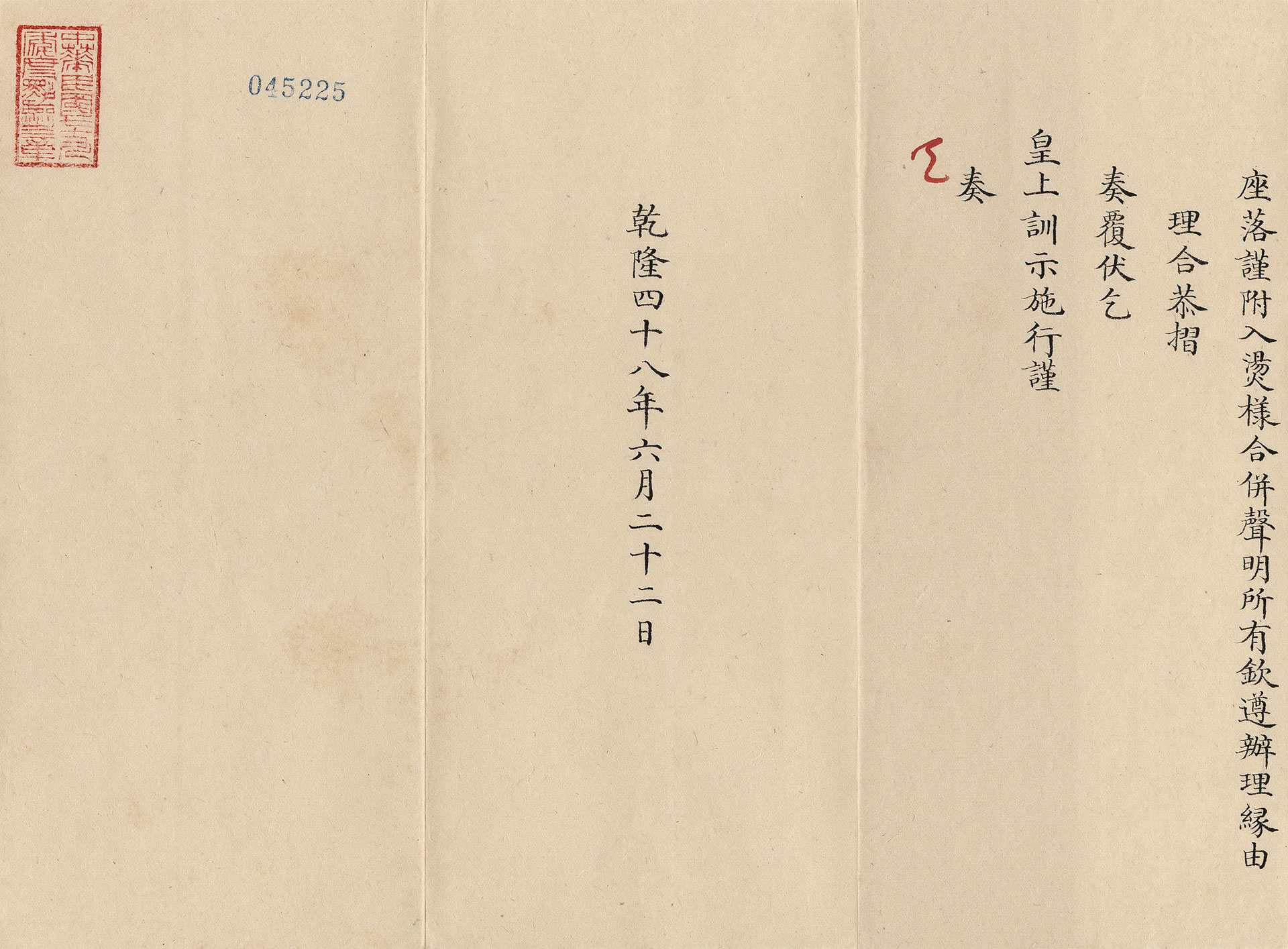

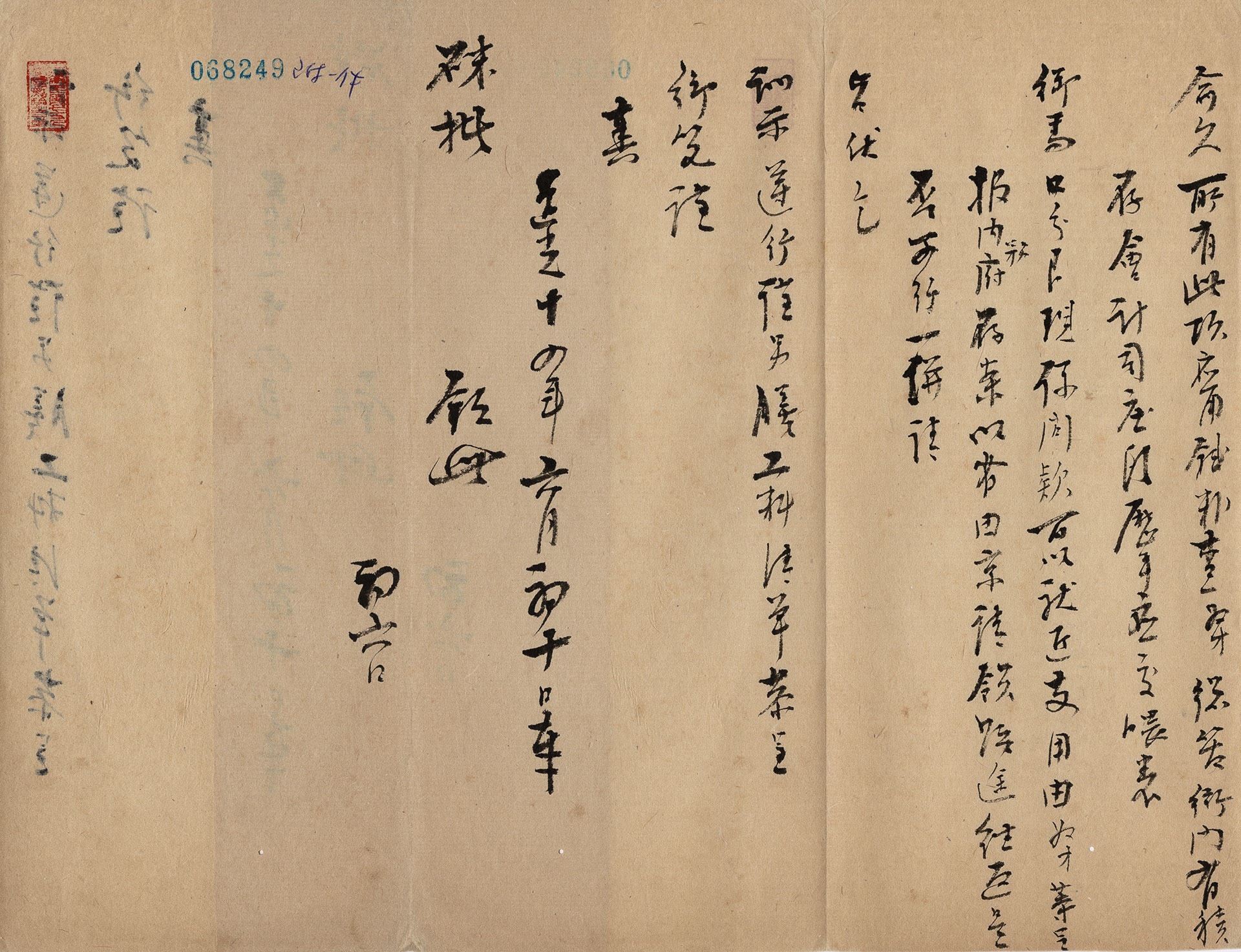

The ministers responsible for construction projects in the Qing Dynasty first conducted design planning, surveyed and measured the spaces, and drew draft sketches. Through multiple revisions, from rough drafts to detailed drawings, they ultimately created the "presentation model" for submission to the emperor. The ministers and presenting the detailed planning through drawings also submitted explanatory reports. When necessary, they would create architectural models, referred to as " Tang yang " or "stamped models," to provide the emperor with a comprehensive understanding of the project.

In these "presentation model drawings", various colored strips of paper, typically yellow and red, were often affixed, containing detailed explanations of the project known as "drawing annotations". After the emperor reviewed the presentation model, if there were any suggested revisions, it would be returned for corrections. In some cases, the emperor would provide instructions to keep the records for his further review before submitting them to the Grand Council for archival purposes. Our institution houses these various forms of presentation models and architectural drawings that were reviewed by the emperor. In this section, we will showcase representative documents from three major categories: "Palace and Garden Construction Drawings", "Temple Construction Drawings", and "Mausoleum Construction Drawings".

Temple Construction Drawings

During the Qing dynasty, the imperial family managed numerous Chinese and Tibetan-style temples. The temples were built (a) by local gentry and donated to the emperor to wish him blessings; (b) because of the religious belief of the imperial family; and (c) as a way for the Qing emperors to strengthen their connections with Mongolian and Tibetan religious leaders. Temples managed by the imperial family must comply with existing standard procedures when built, renovated, maintained, and even demolished. Drawings must be made and submitted to emperors for approval prior to the initiation of any operation.

The drawings and documents exhibited here were the data submitted to the emperor and used during temple constructions. The 2D and 3D drawings are delicate and interesting, respectively. The emperors sometimes indicated his decisions in the drawings, verifying their roles as leaders during the construction process.

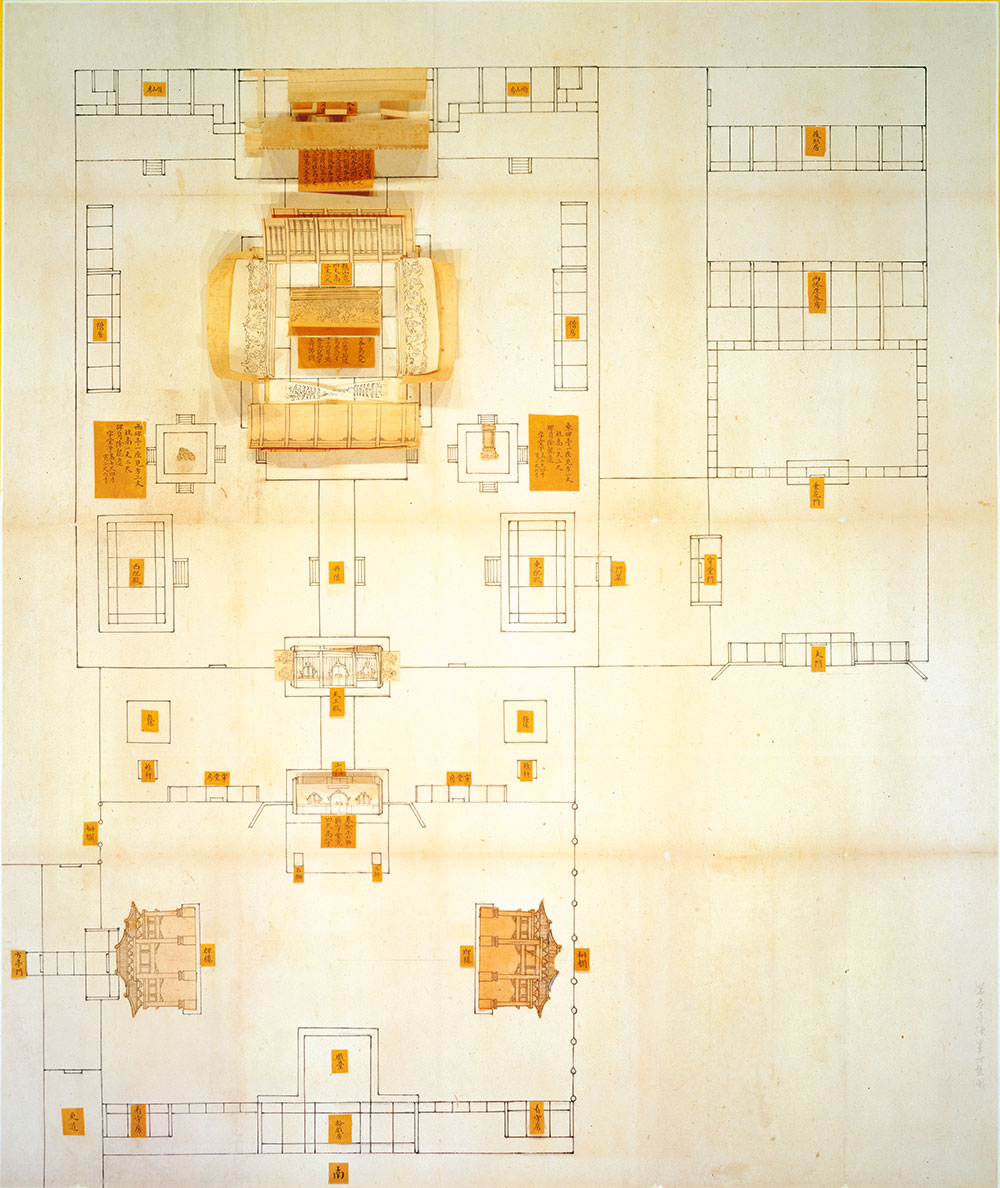

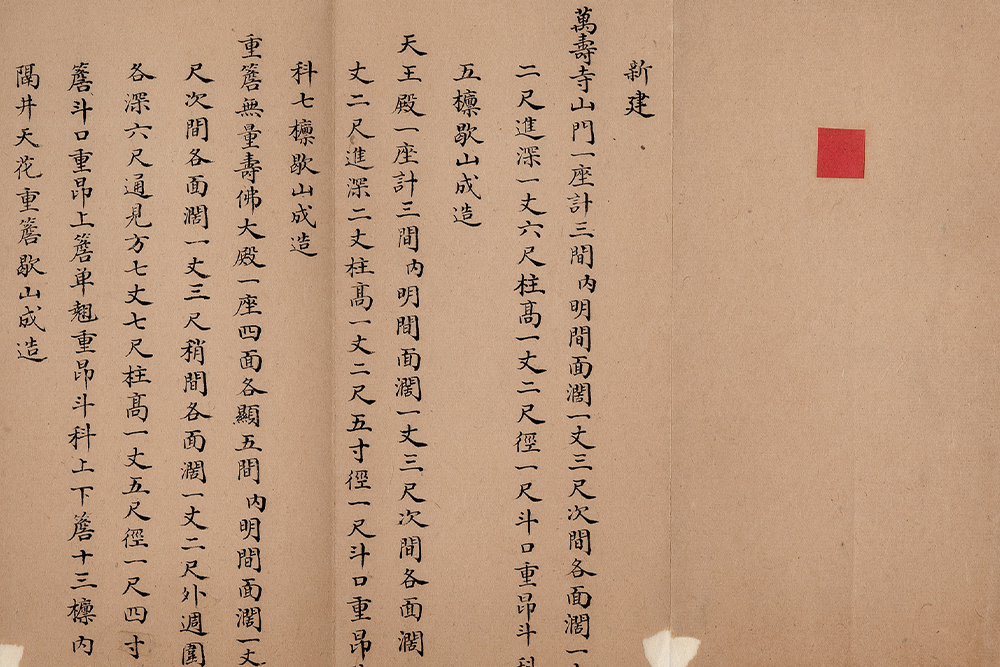

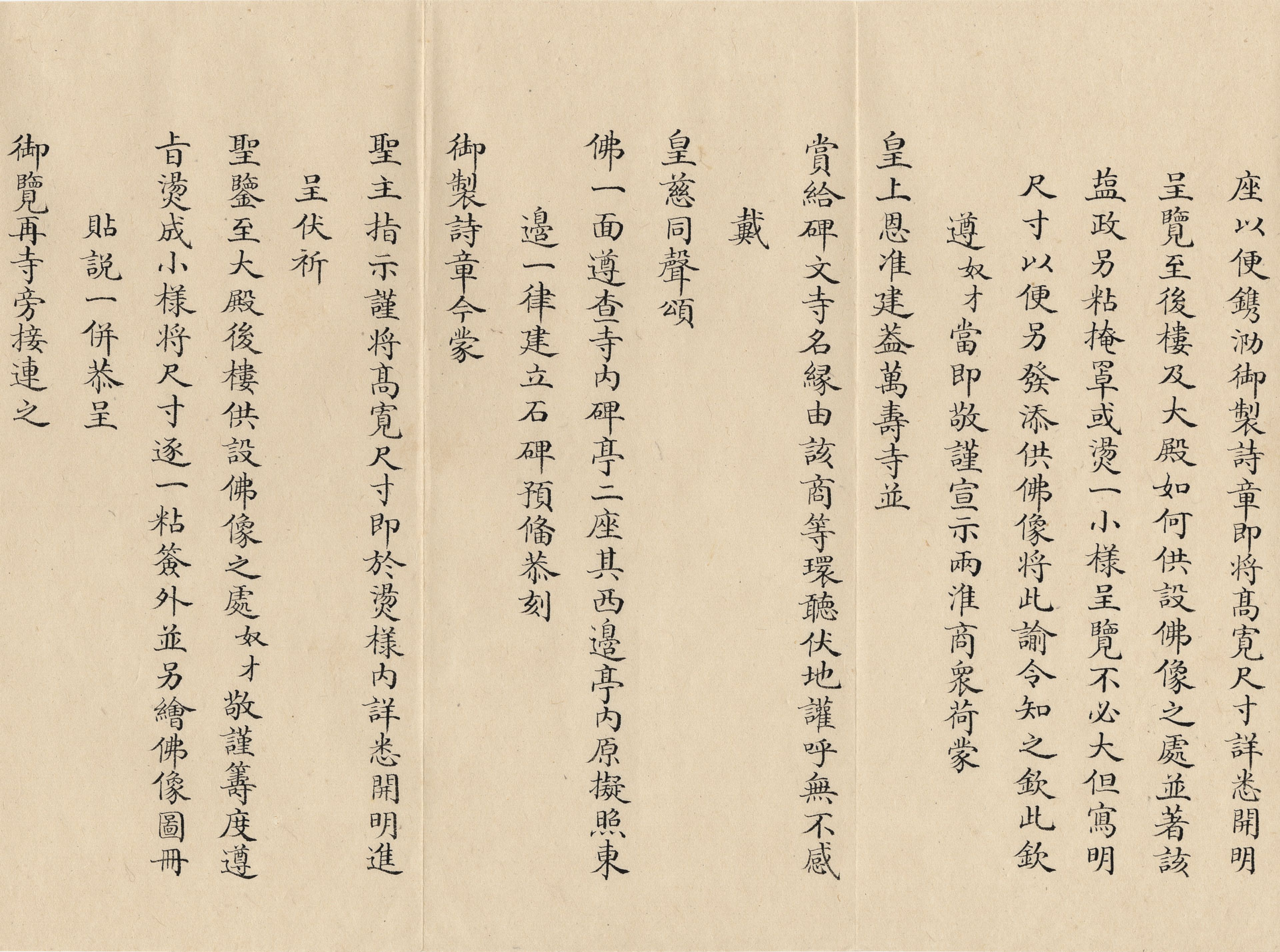

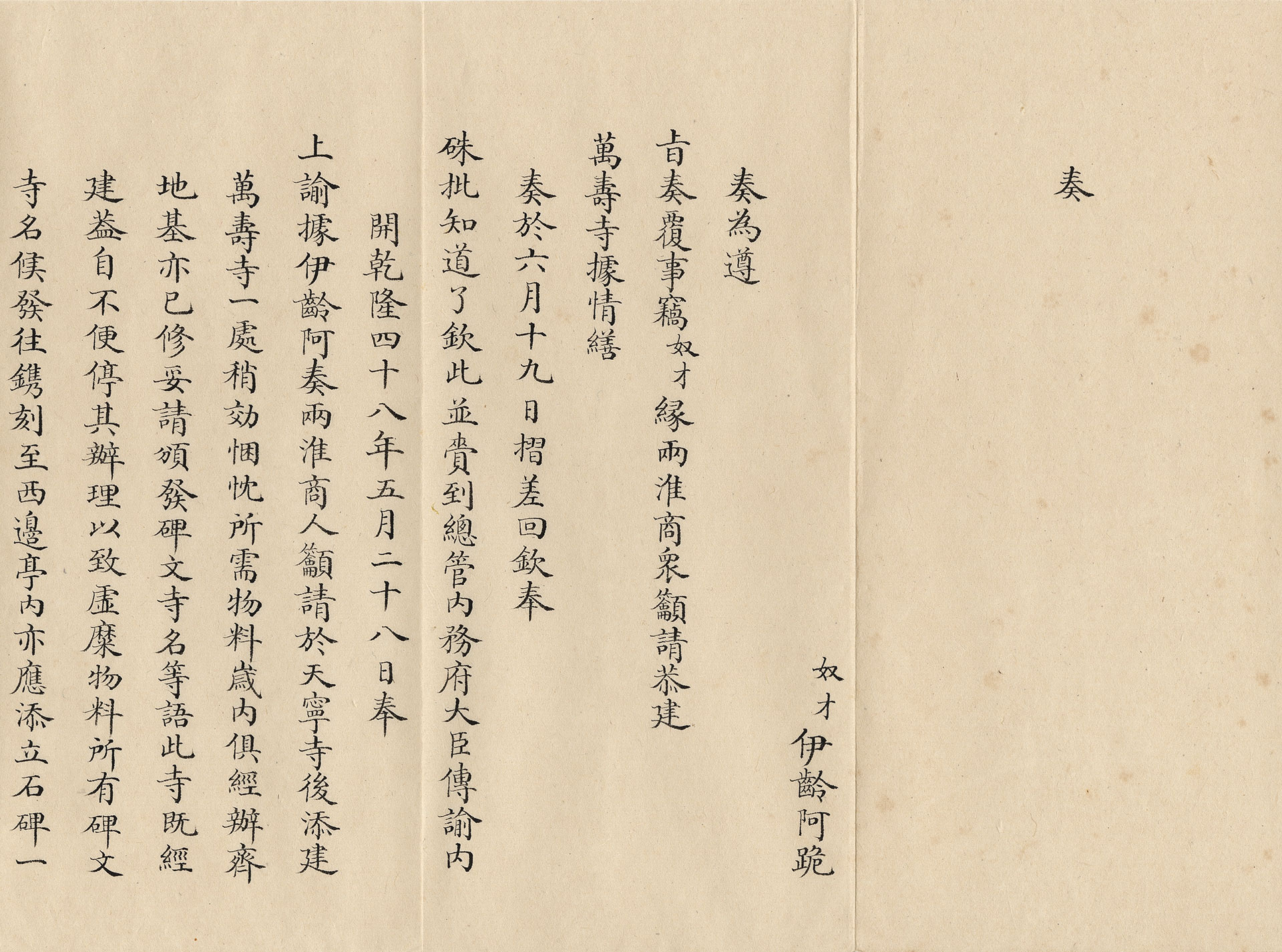

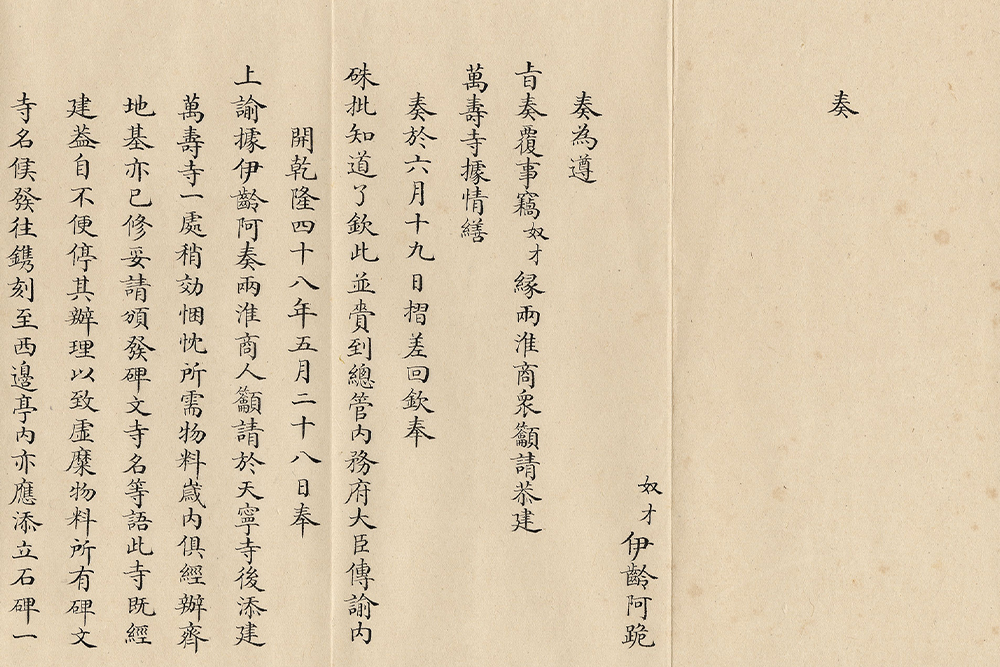

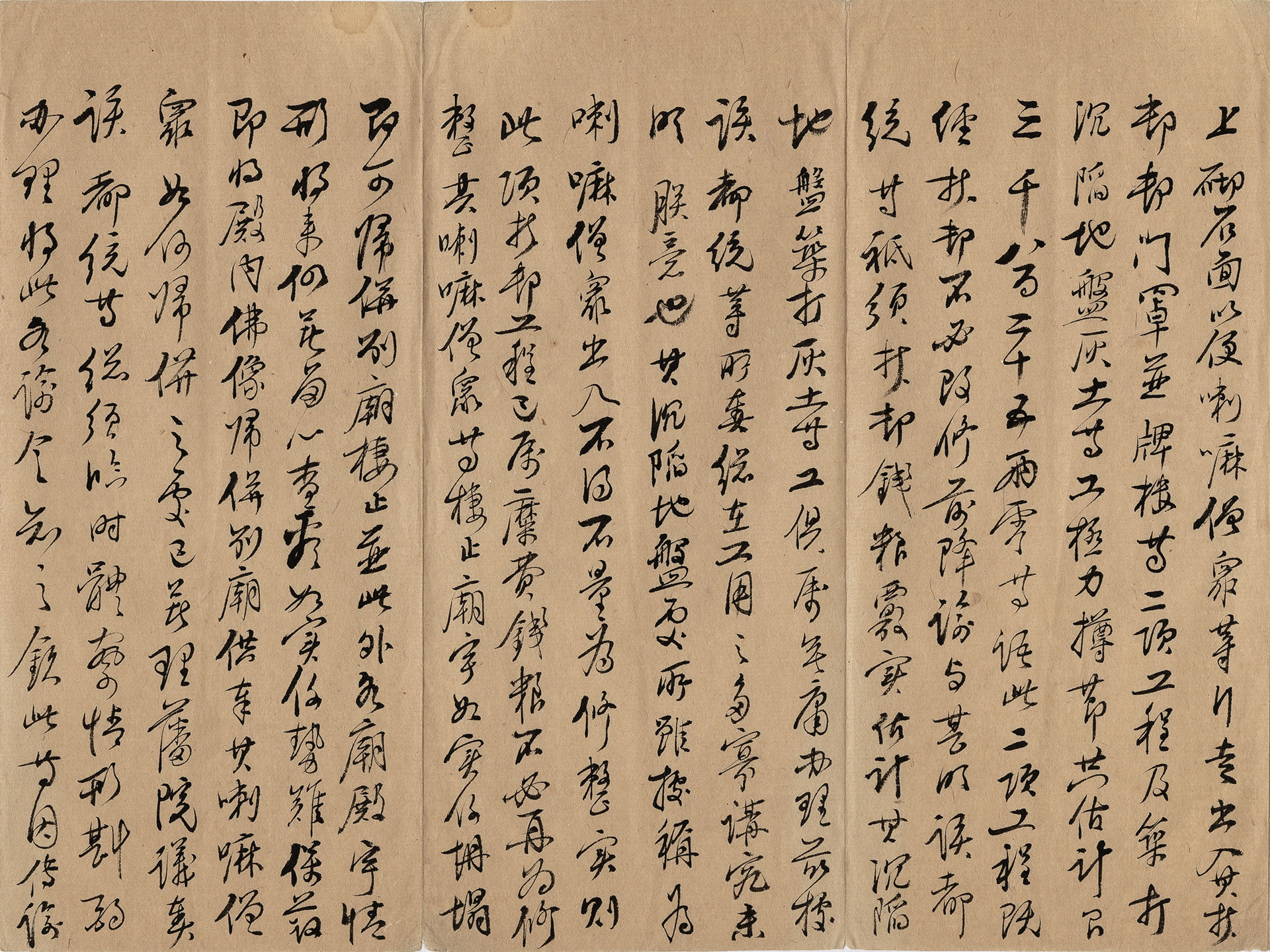

To celebrate the 6th southern inspection tour made by Emperor Qianlong in 1784 and to ingratiate with the emperor (by congratulating him on his birthday), local gentry in Jiangnan proposed that Ilingga (?-1795), a salt official of Huainan and Huaibei, build an additional temple behind the Tianning Temple in Yangzhou. Thus, Ilingga submitted a palace memorial to Emperor Qianlong reporting such. The emperor not only granted the construction but also got involved with designing the temple. He ordered that the Imperial Household Department send personnel to assist in the construction. The Wanshou Temple was completed in 1784, and the emperor named it the “Wanshou Chongning Temple” during his visit there. Together with the Tianning Temple, the Wanshou Temple was collectively referred to as the “twin temples of Yangzhou,” becoming one of the eight temples in Yangzhou in the Qing dynasty.

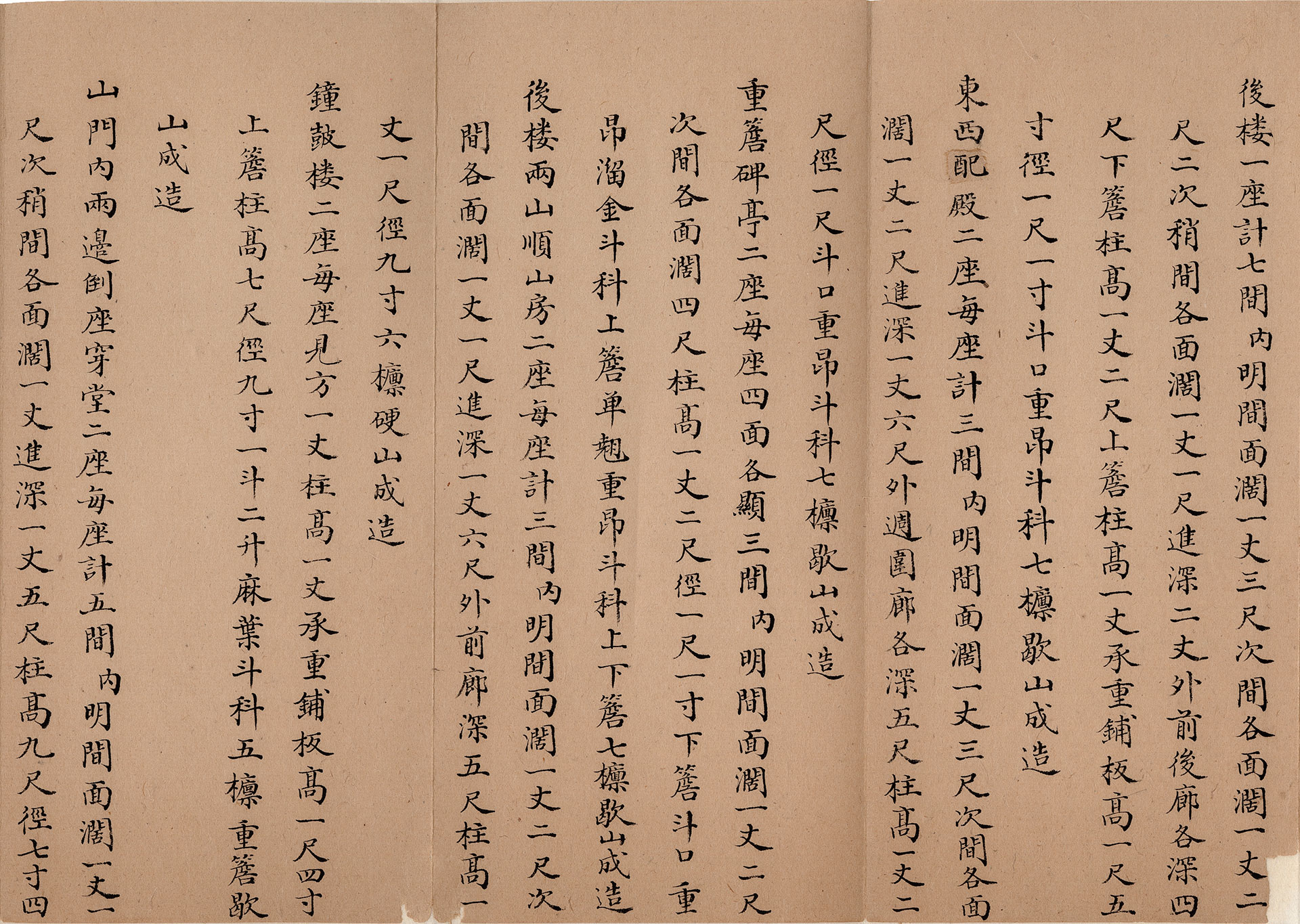

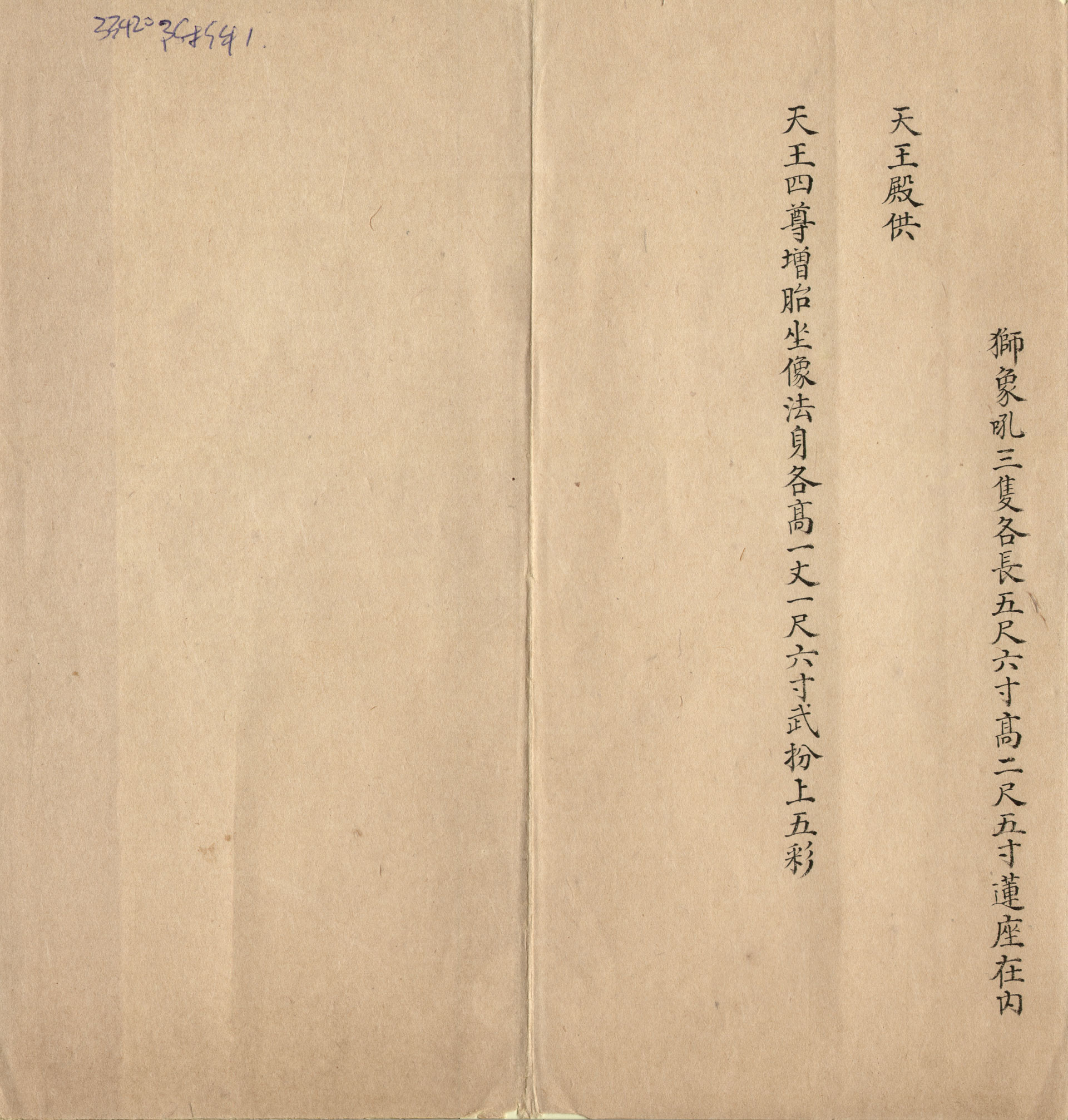

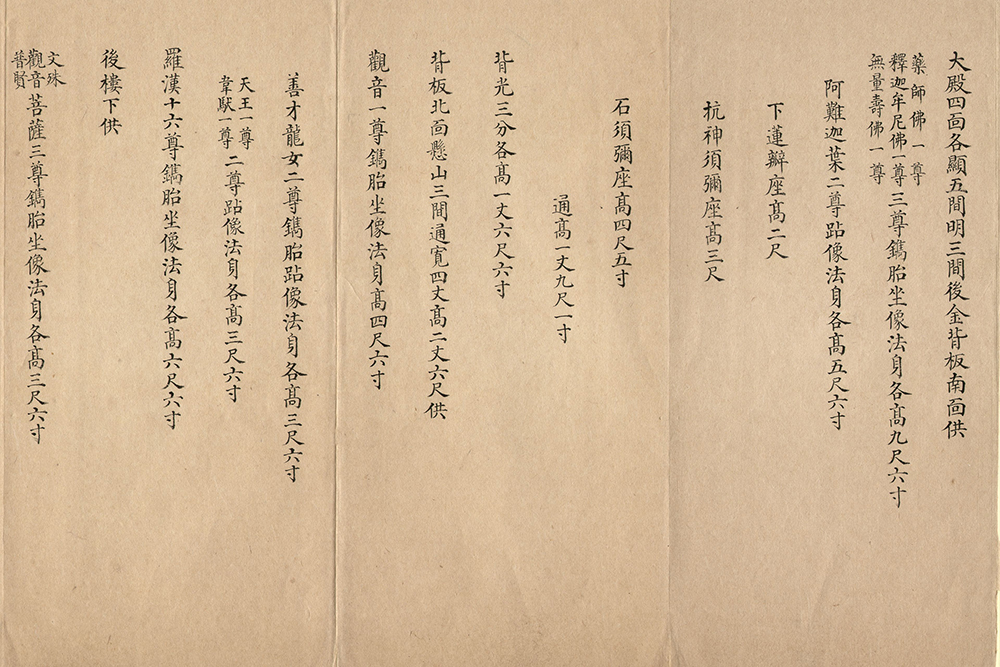

The artifacts exhibited here include documents such as palace memorials submitted by government officials, architectural lists, architectural drawings (e.g., temple floor plans and 3D internal construction drawings (floor plans)), and lists detailing the specifications and dimensions of temple buildings and Buddha statues. The “Wanshou Temple Floor Plan,” one of the artifacts exhibited, is a floor plan that combines 2D and 3D images together. Although the drawing is partially damaged due to its age, it allows its readers to gain insight into the different aspects of imperial Qing architectural drawings.

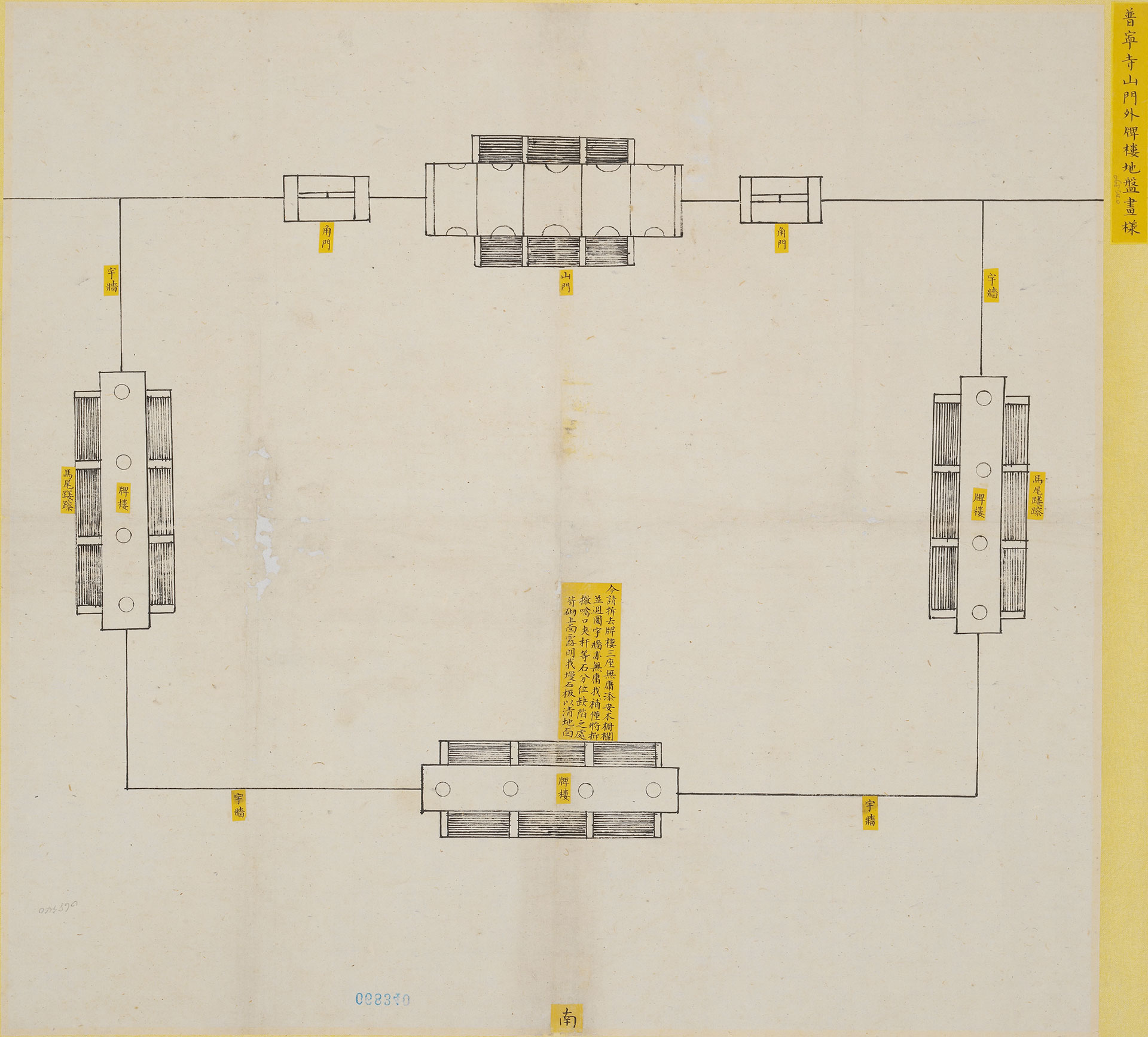

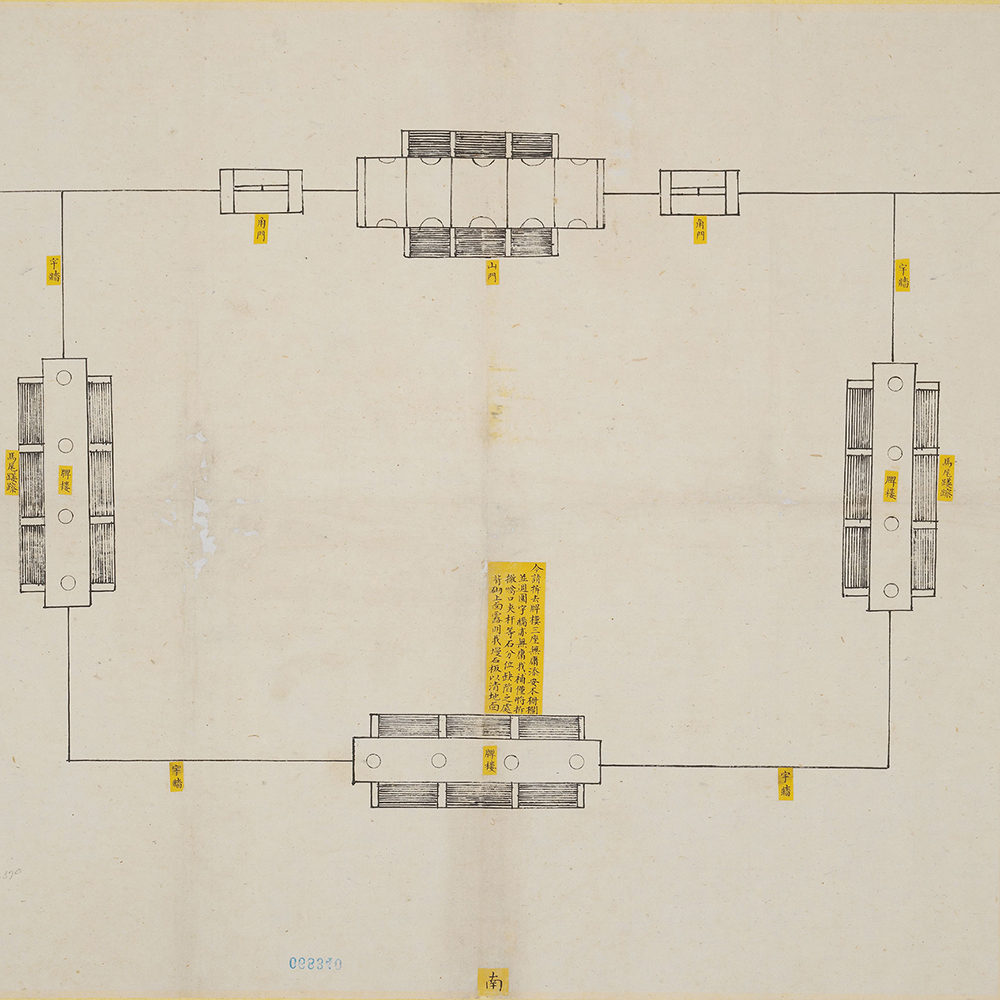

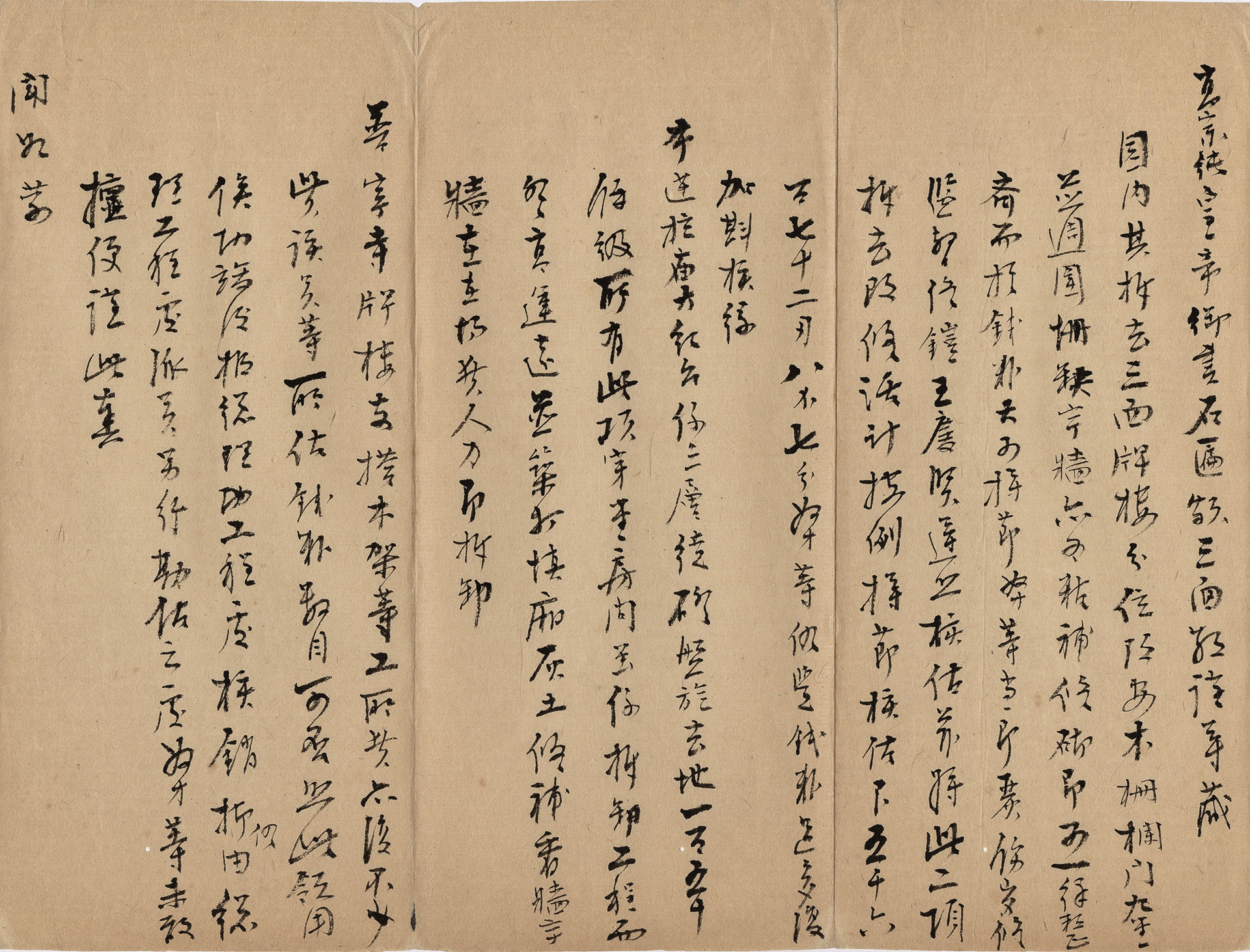

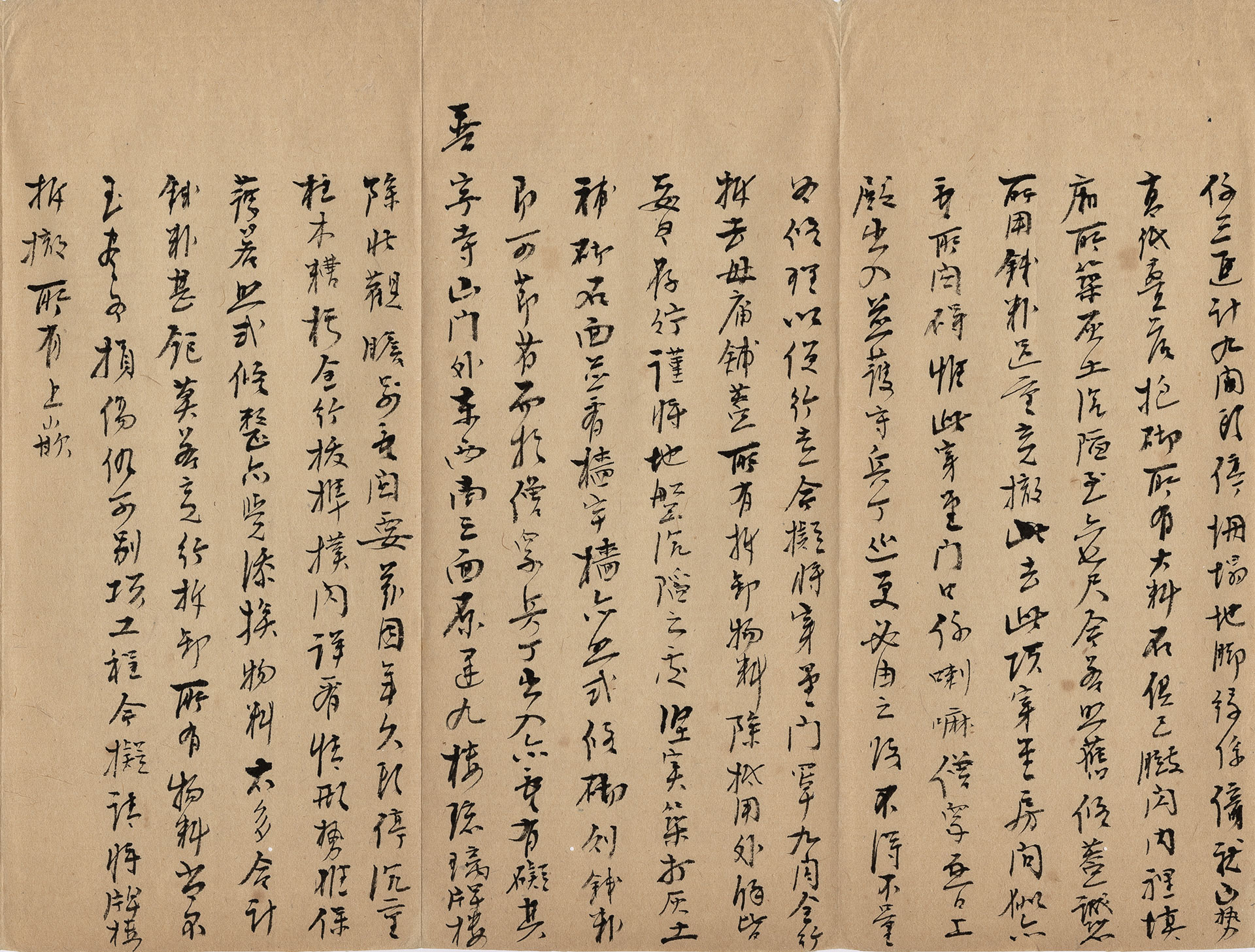

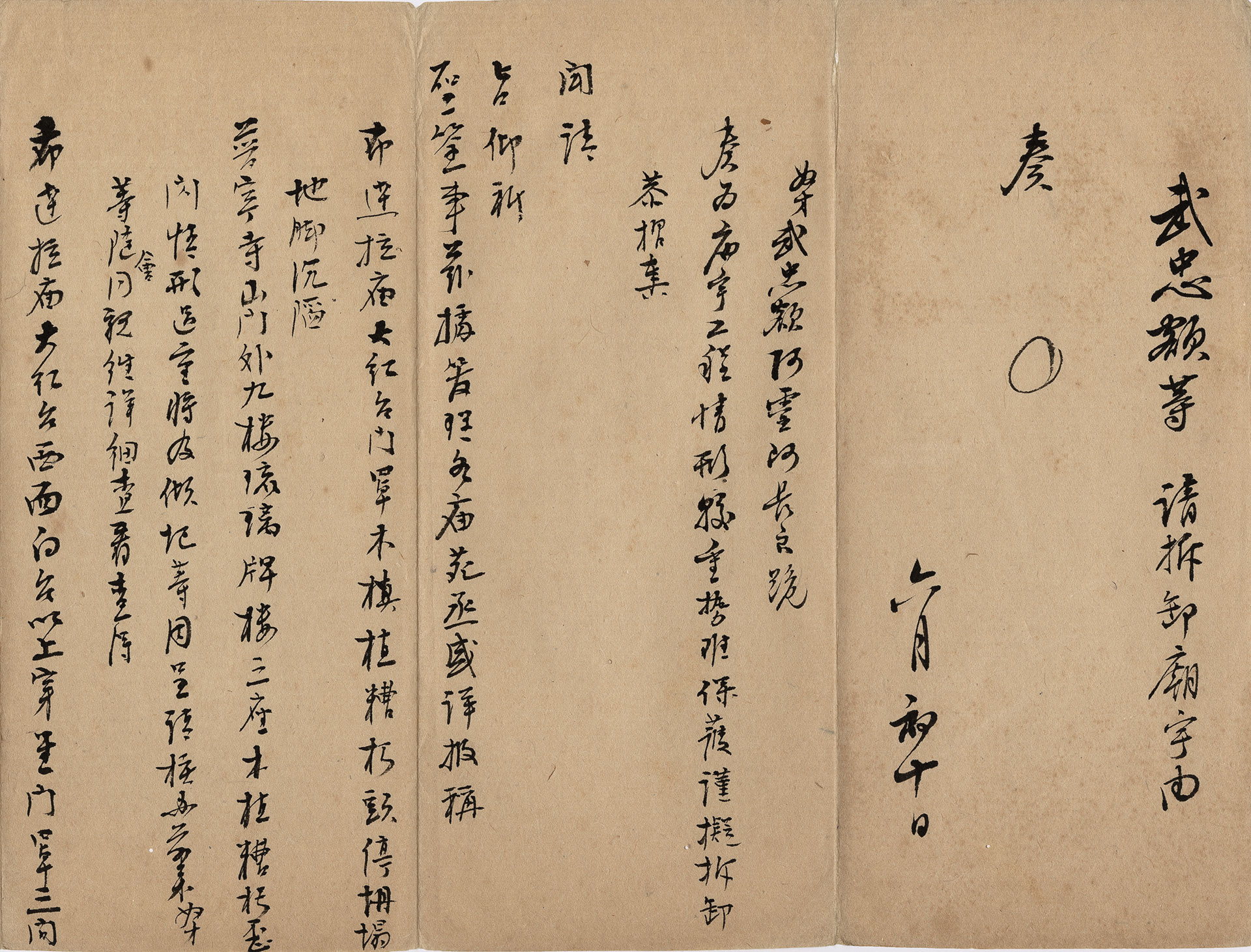

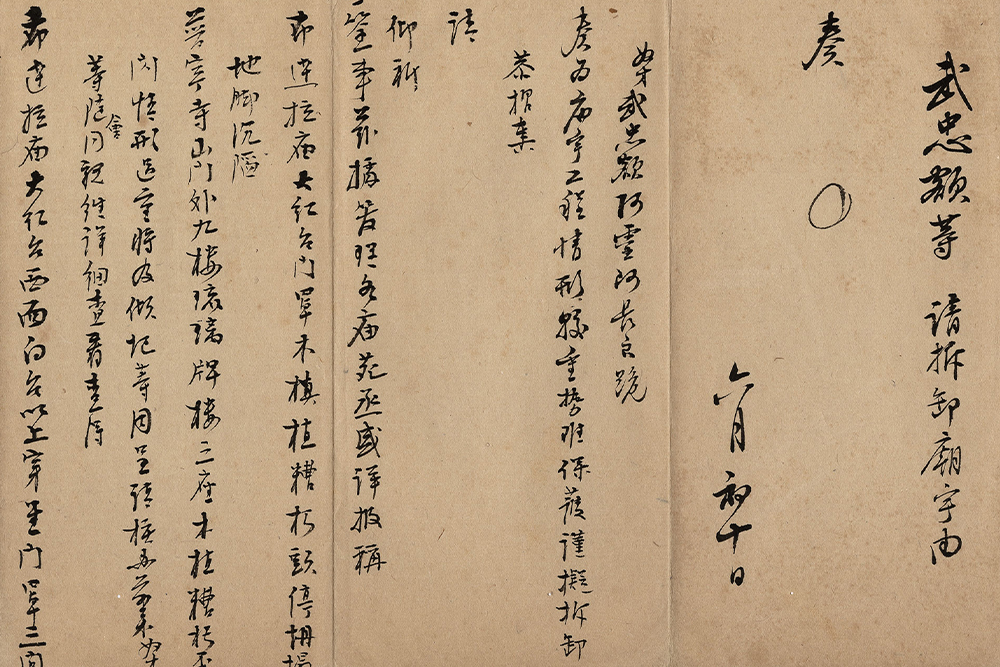

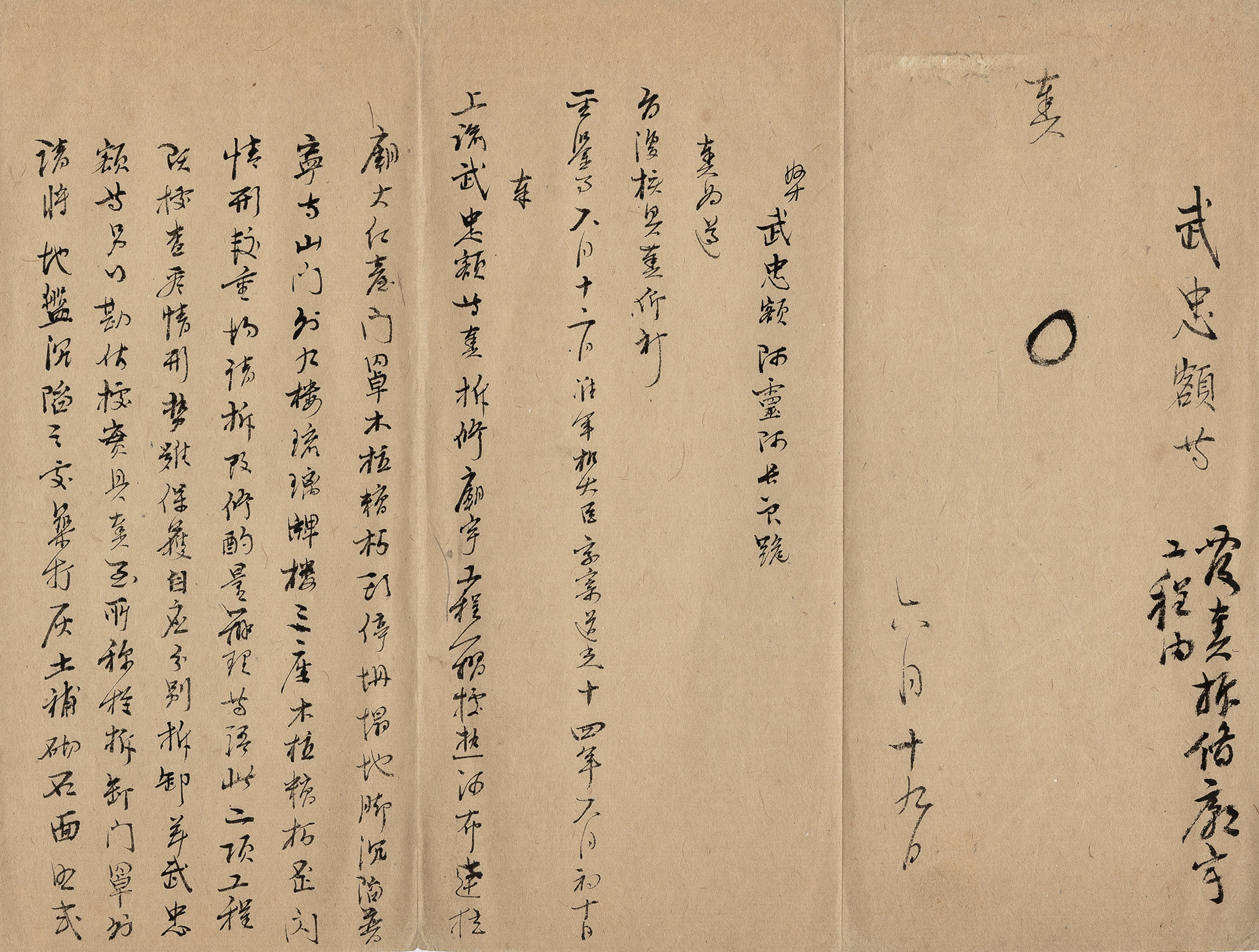

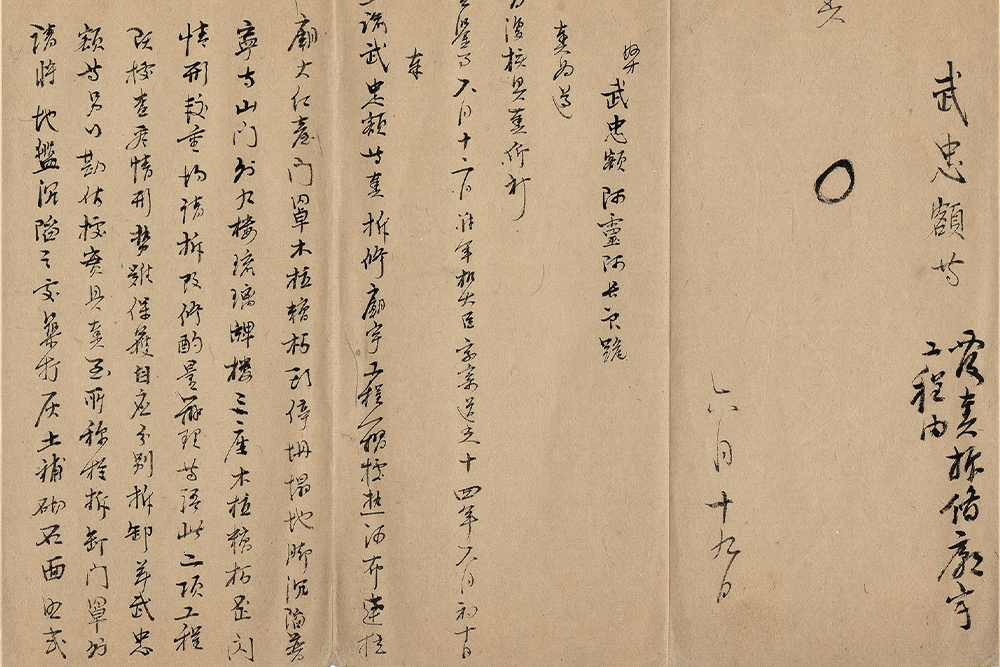

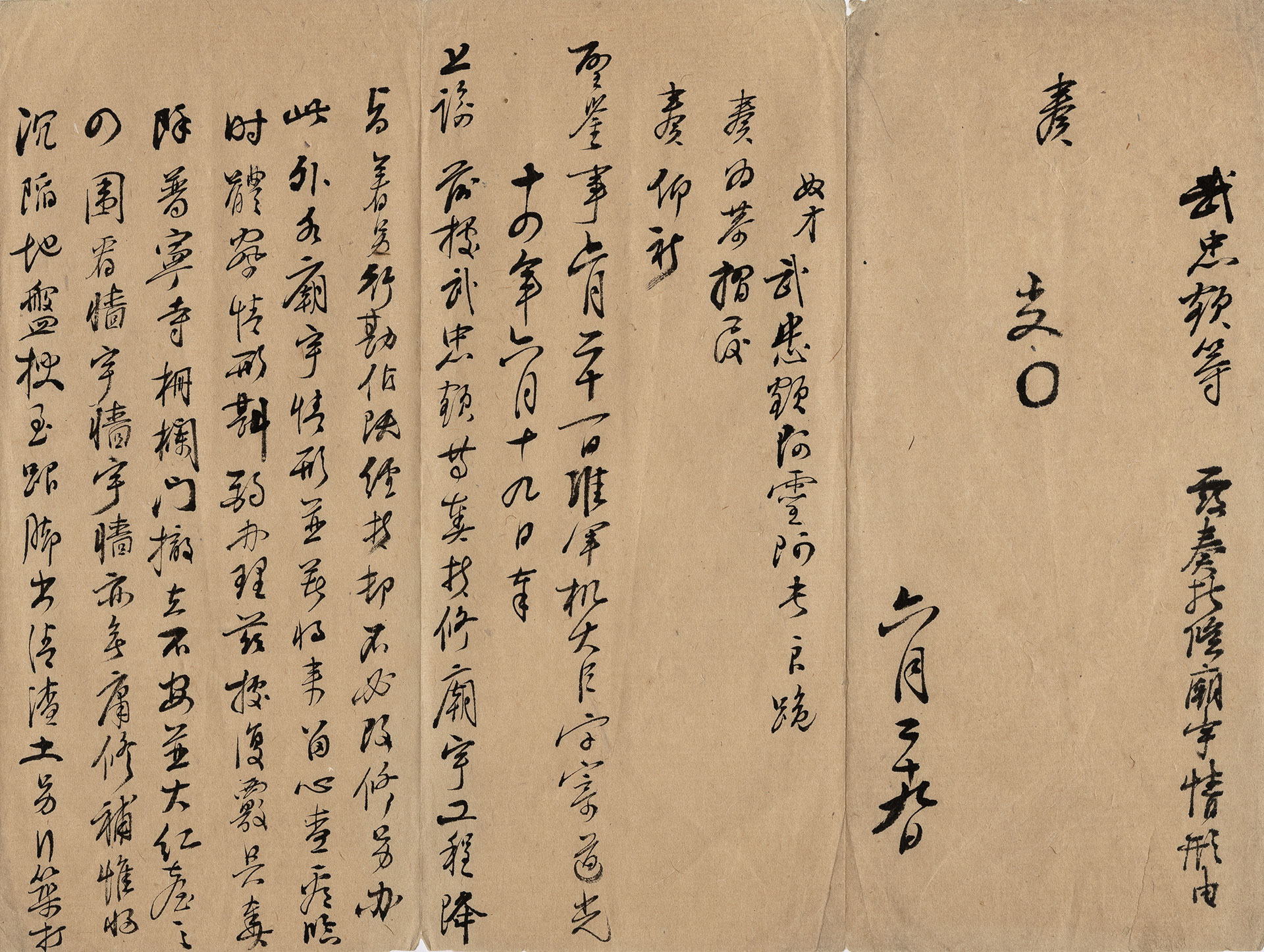

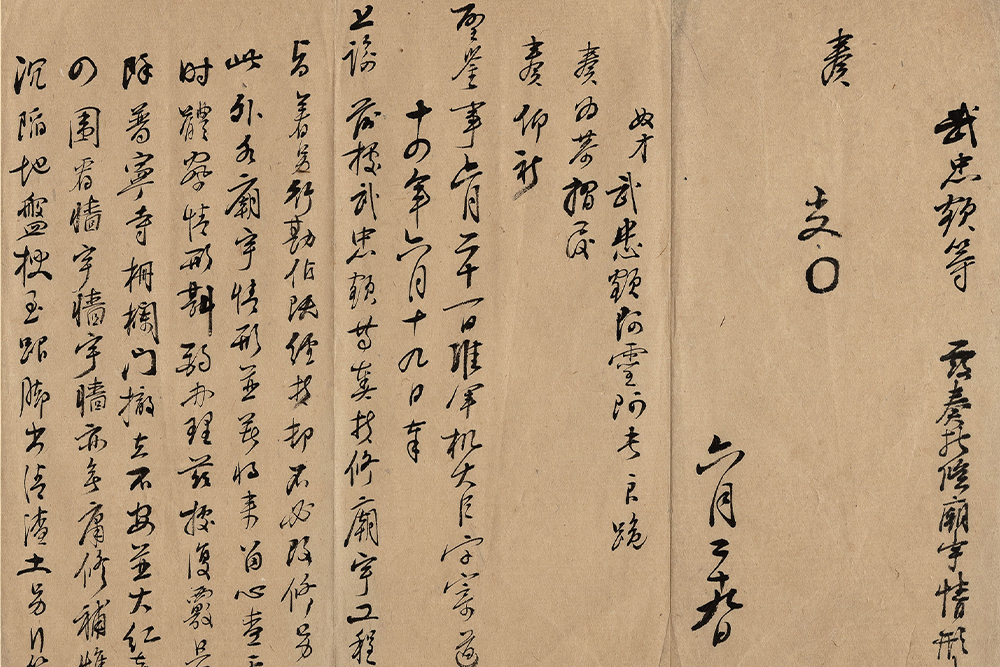

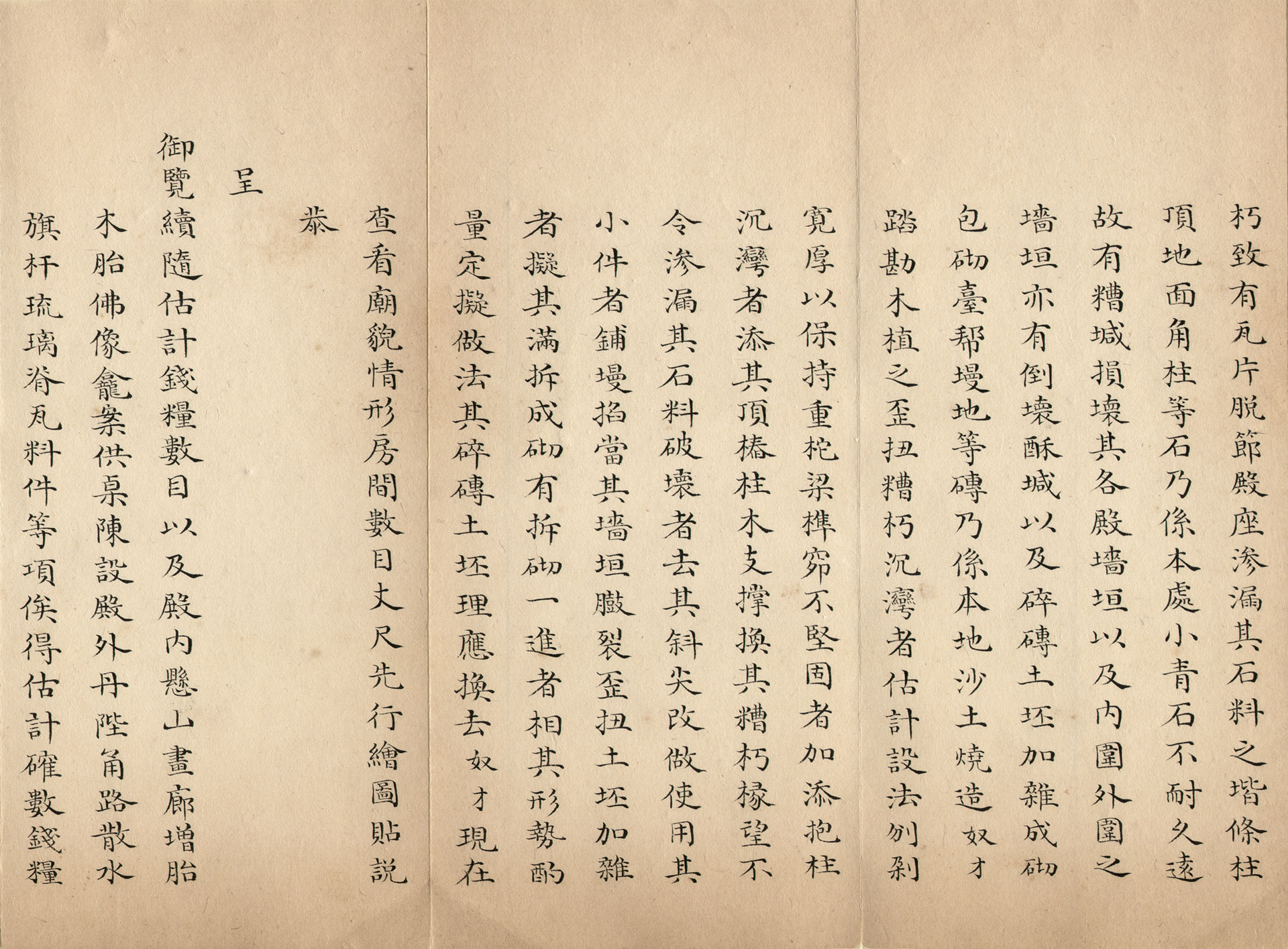

In June 1834, Wu Zhong’e (1775-1848), the commander-in-chief of Jehol, inspected his jurisdiction and discovered that the imperial family temples around the Summer Resort were in disrepair. Among said temples, the gate decorated archway of the Puning Temple built in 1759 and the ancestral hall on the right of the Great Red Terrace of the Putuo Zongcheng Temple (also known as the “Potala Palace”) completed in 1771 were the most worn-down.

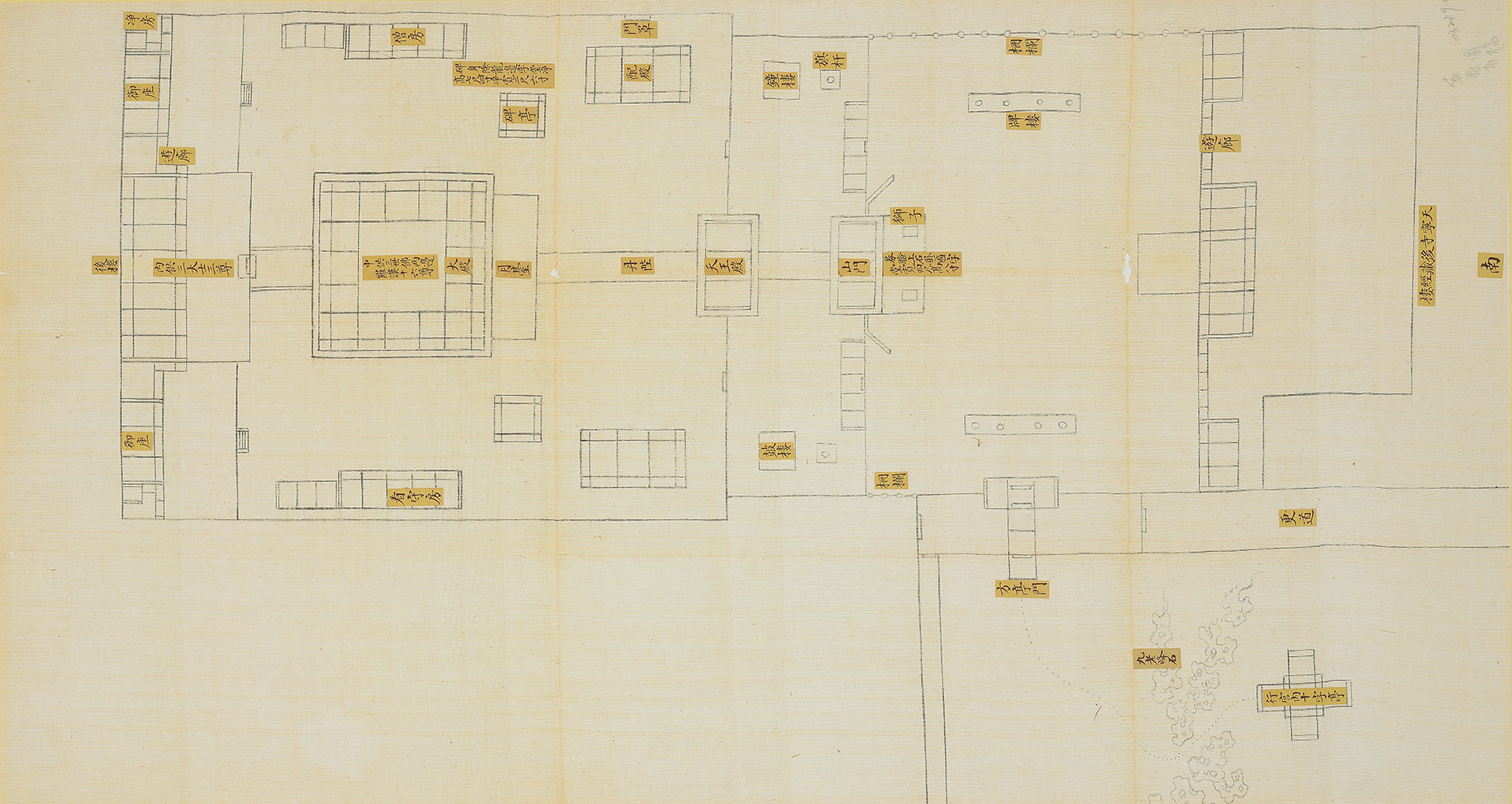

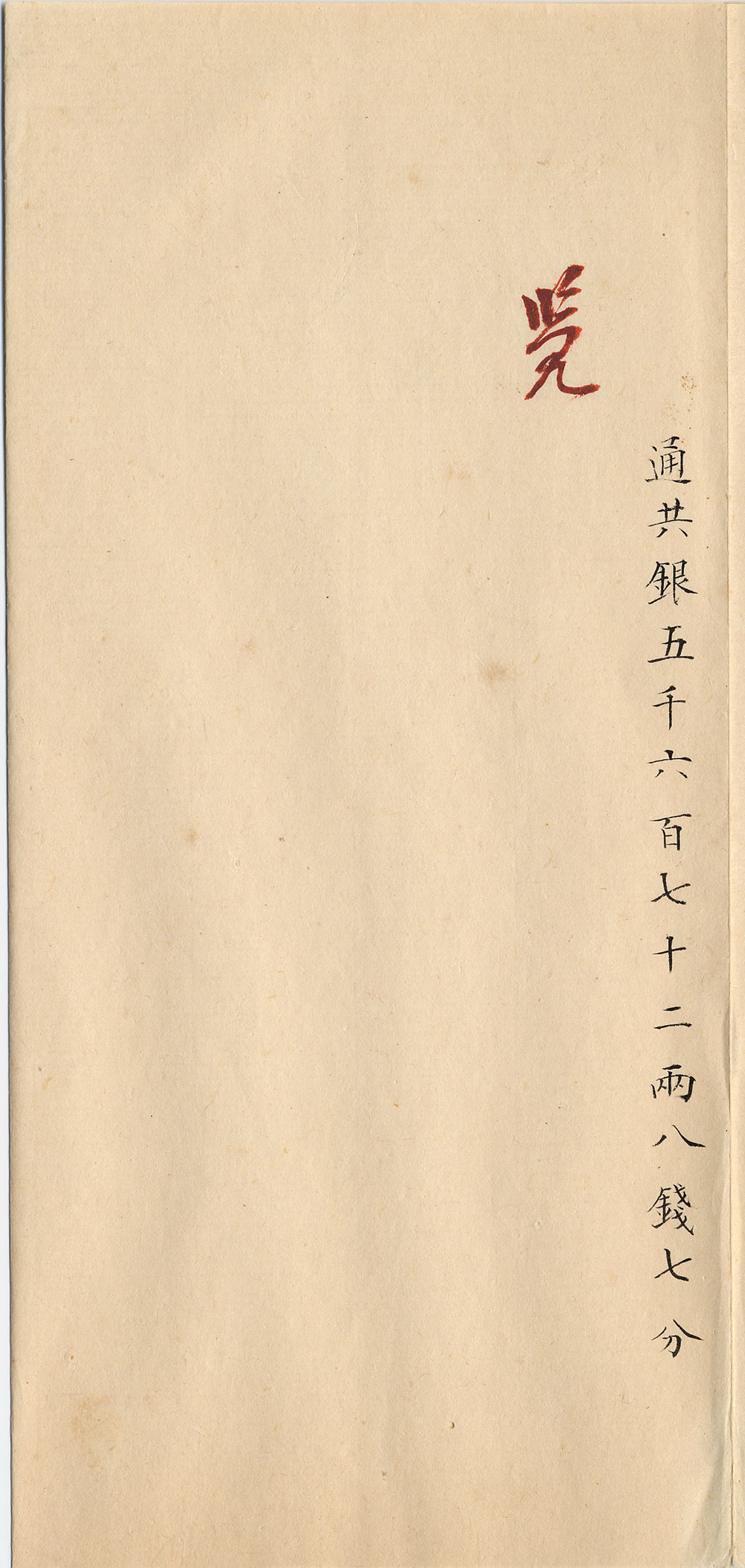

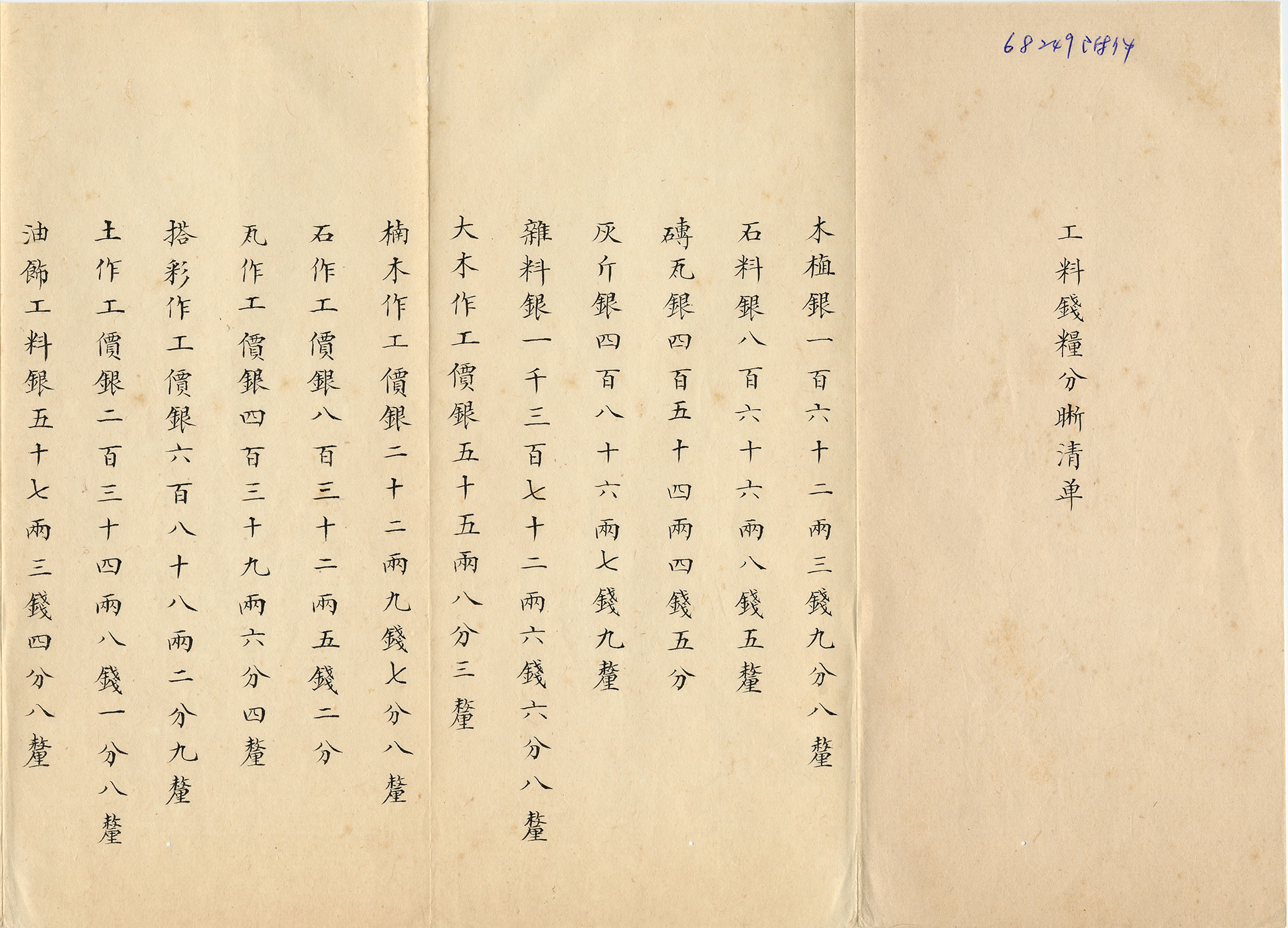

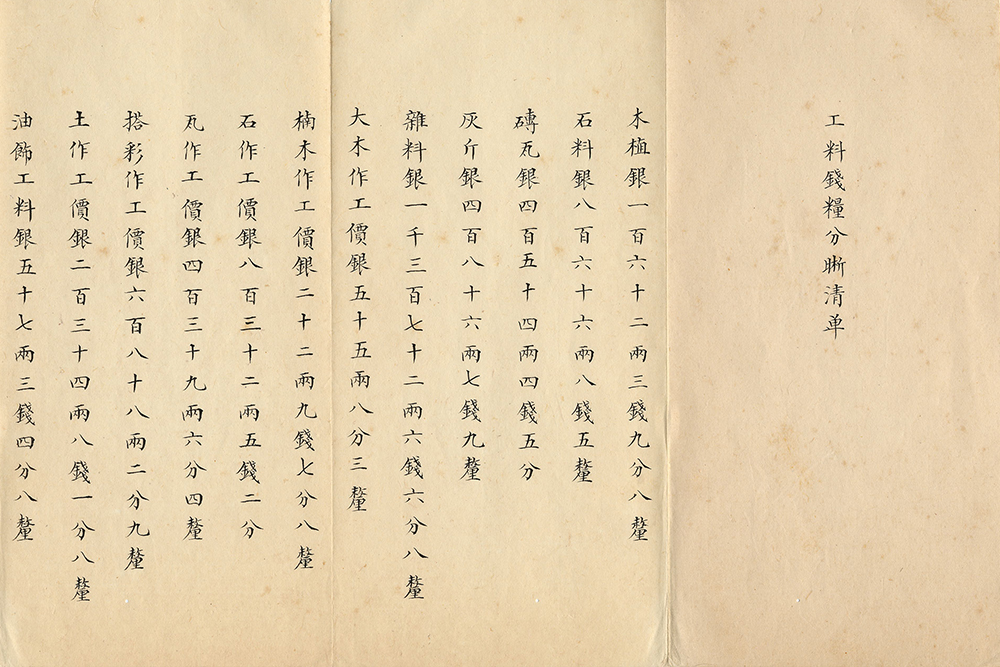

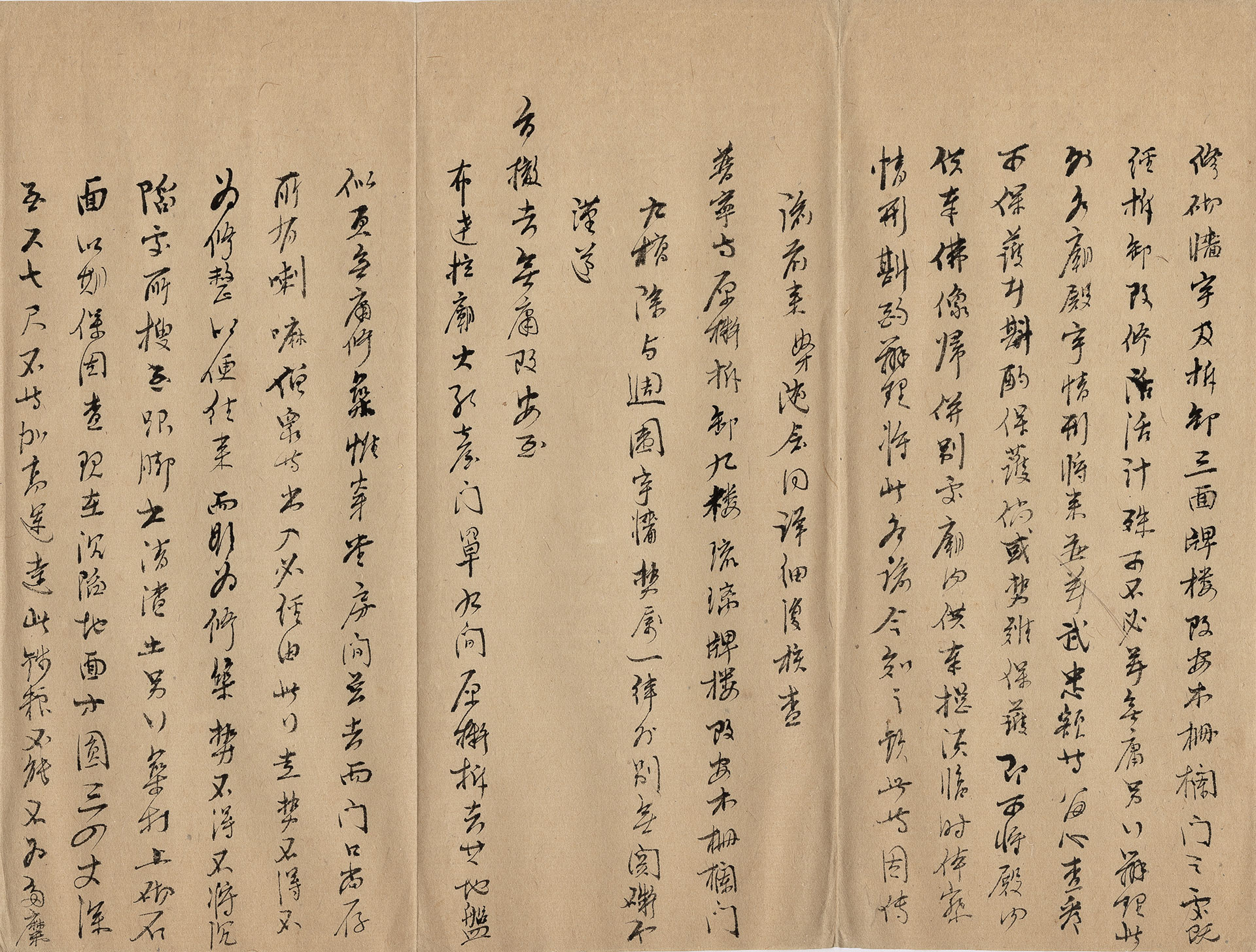

Wu Zhong’e immediately sent personnel to survey the temples and estimate their repair costs. Concurrently, Wu reported to the emperor (via a palace memorial) proposing the repair and demolition plans. The artifacts exhibited here include lists of the estimated material costs of the aforementioned projects well as drawings “Site Drawing of the Gate Decorated Archway of the Puning Temple” and “Site Drawing of the Great Red Terrace of the Putuo Zongcheng Temple” for the emperor to review. For both drawings, yellow tags that marked building locations and place names around the temples were attached, and construction plans were glued onto the drawings. Both construction drawings were drawn in 2D, with “Site Drawing of the Great Red Terrace of the Putuo Zongcheng Temple” containing also 3D models, making the reading of these engineering drawings fascinating.

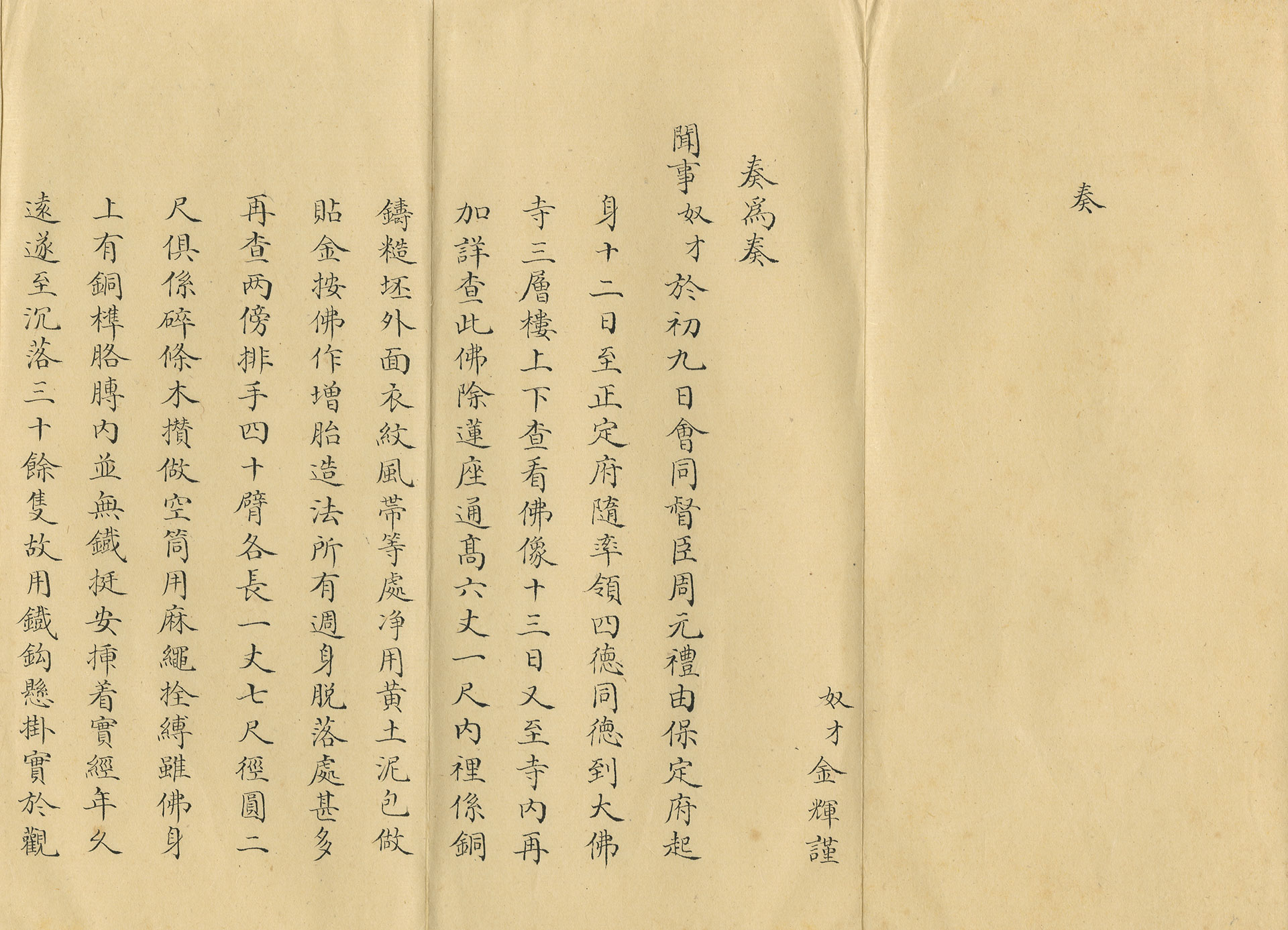

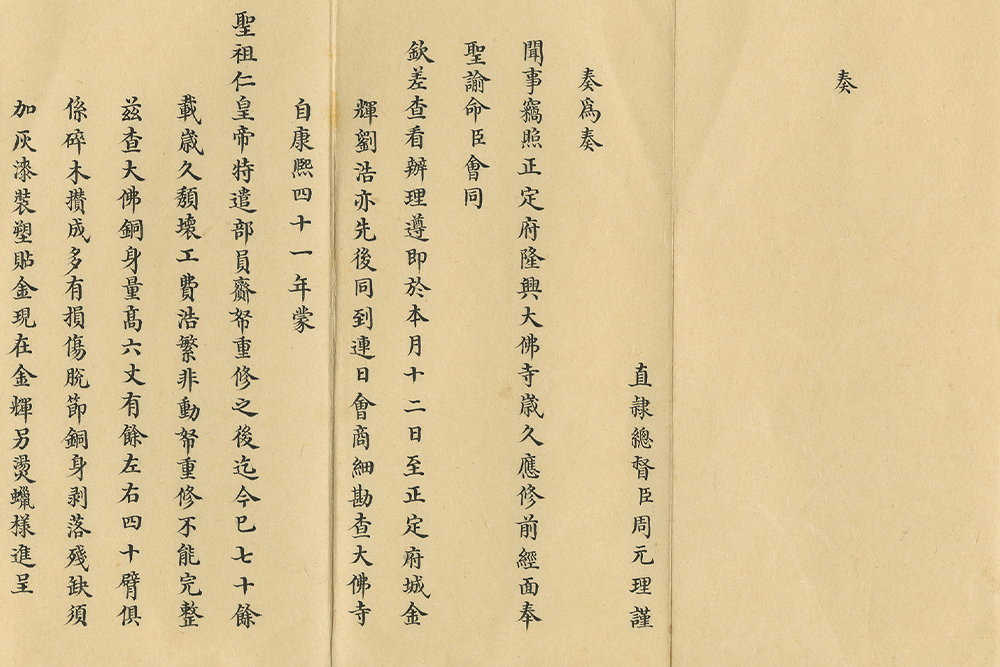

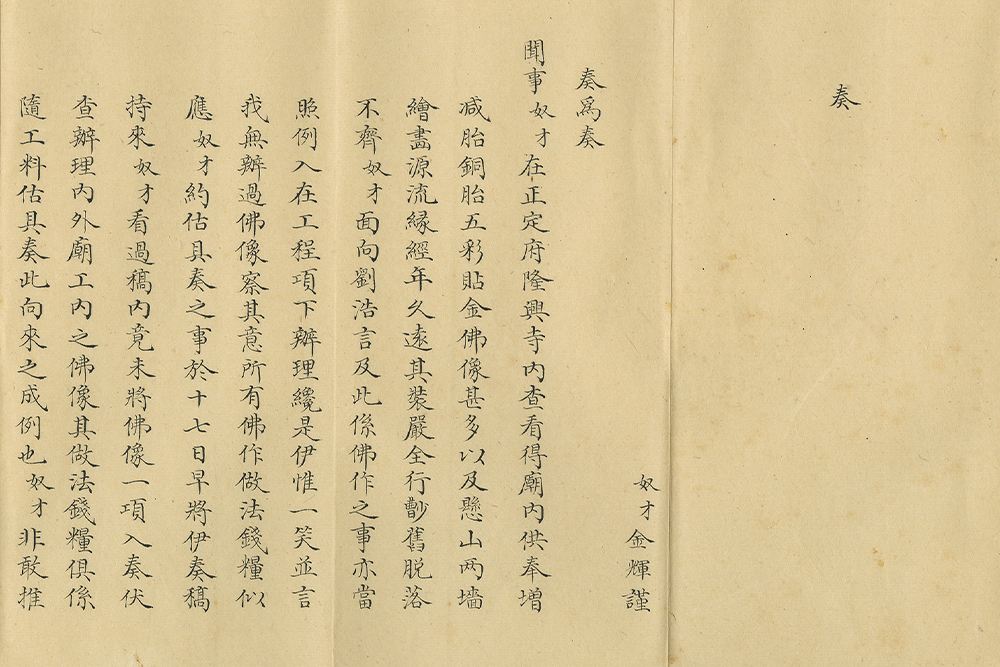

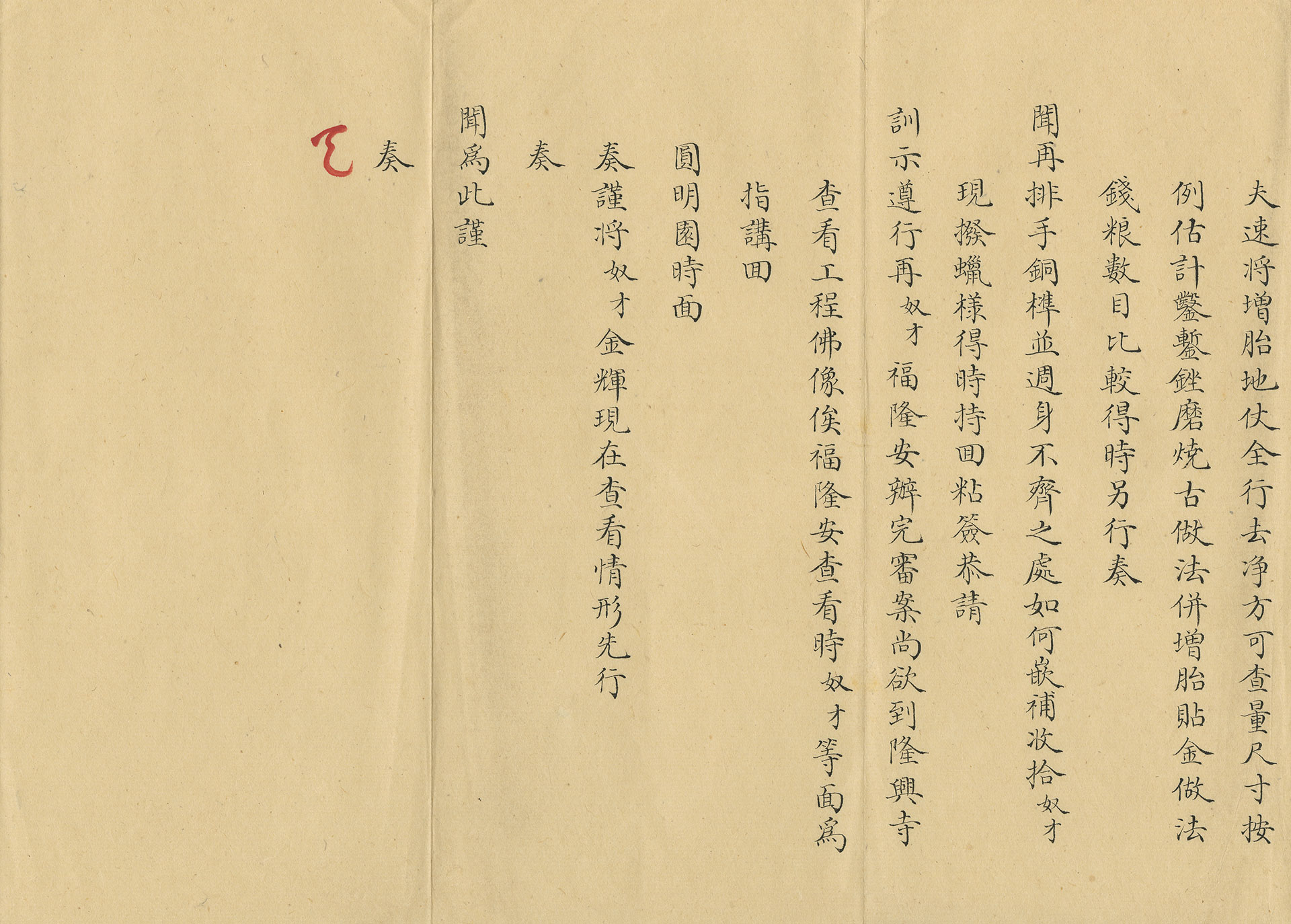

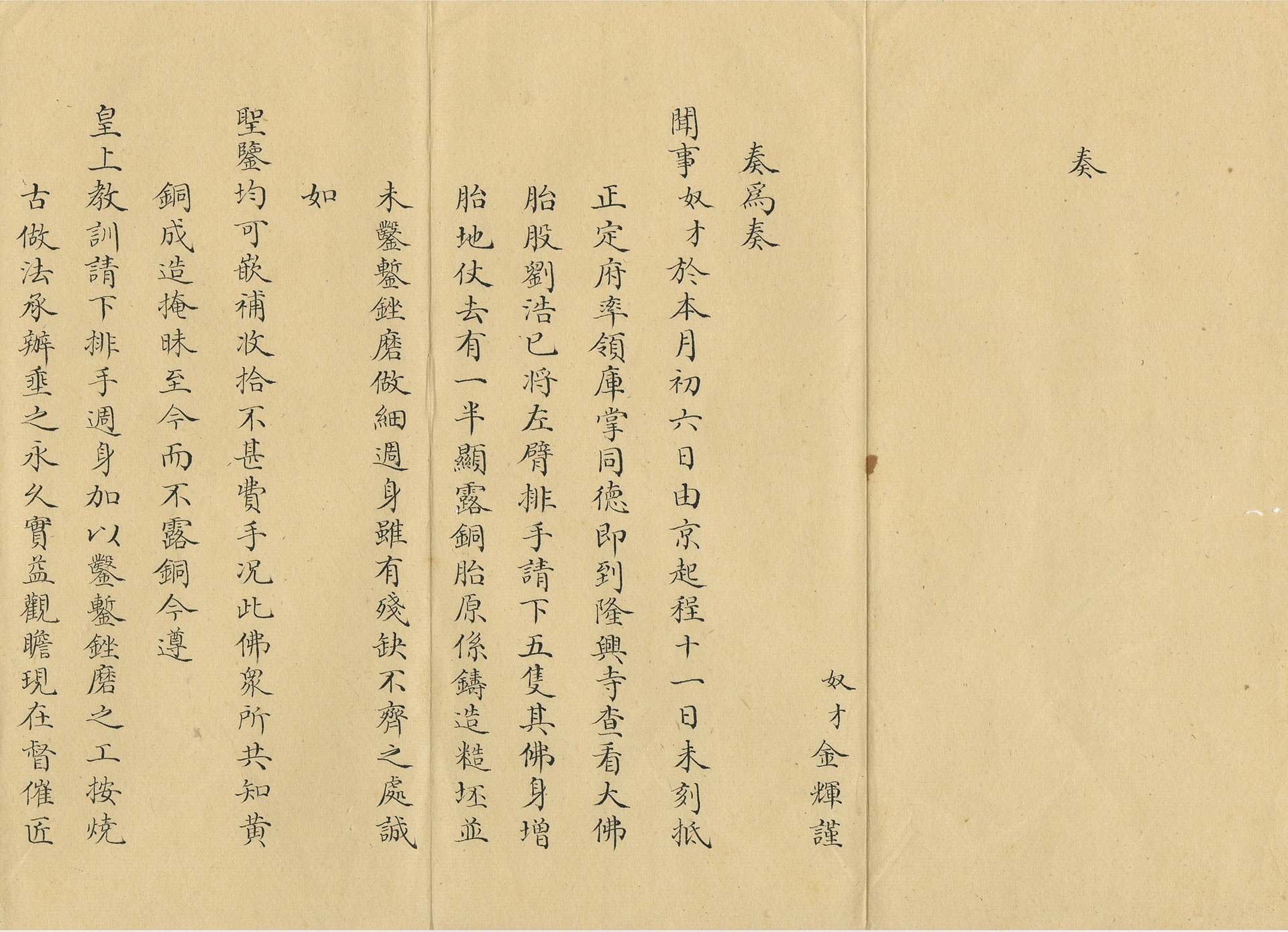

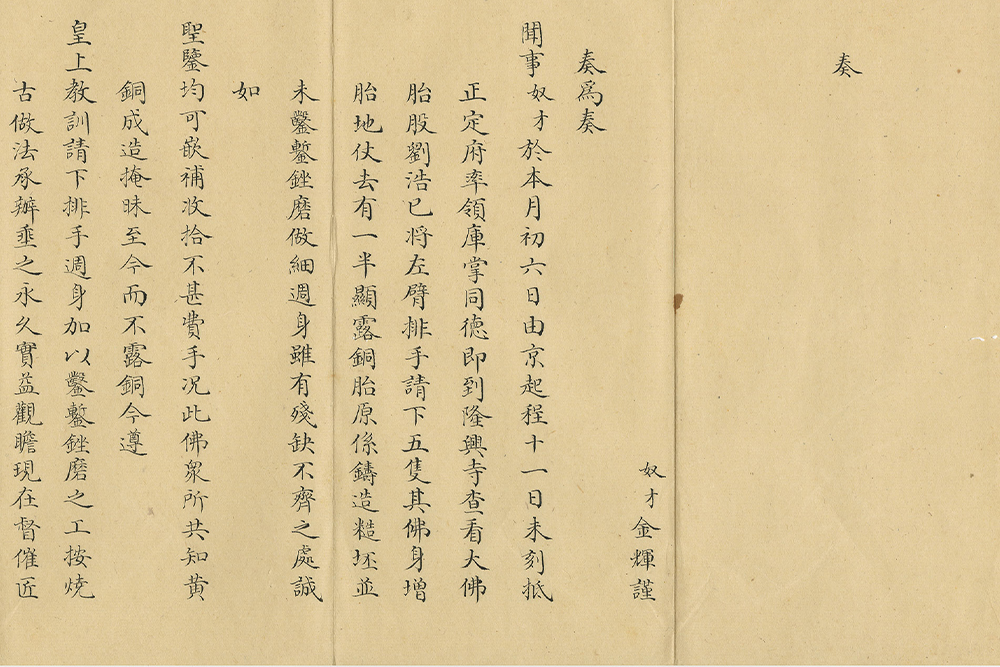

Among imperial family temples in China, the Longxing Temple in Zhengding County, Hebei ranks at the top in terms of its architectural art, history, and culture. Built in 586, the temple was initially called the “Longcang Temple.” The temple underwent a number of renovations as mandated by the emperors from different dynasties, and was eventually renamed the “Longxing Temple” in the Tang dynasty. Because of the attention and support from imperial families across different dynasties, the buildings and collections of the temple became more and more enriched, and the thousand-year-old temple eventually became one of the famous temples north of the Yellow River. In 1711 (Qing dynasty), the name “Longxing Temple” was written on a plaque, preserving the name of the temple to this day.

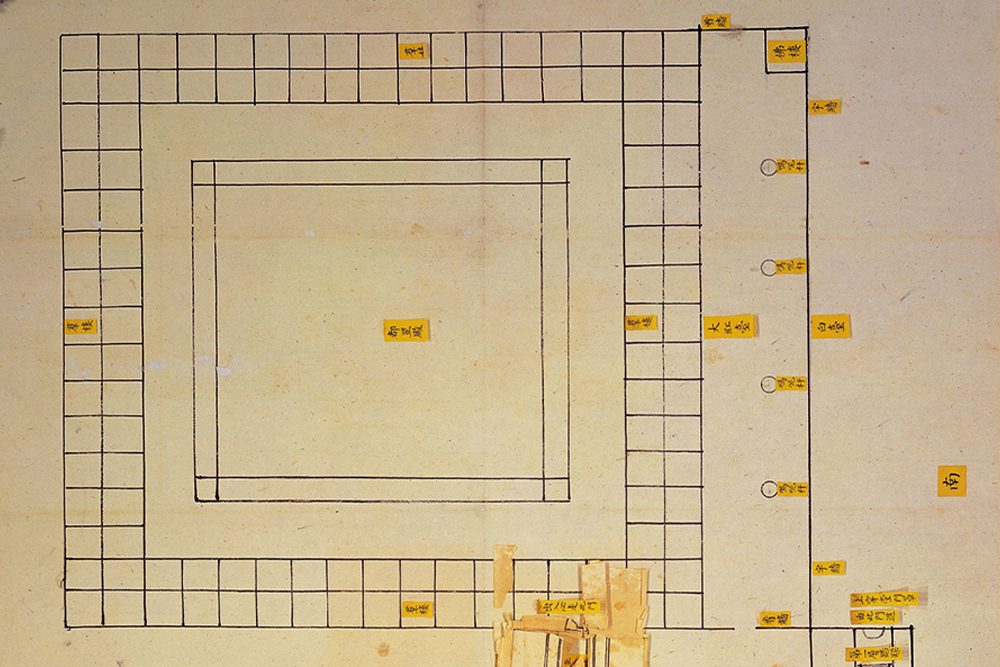

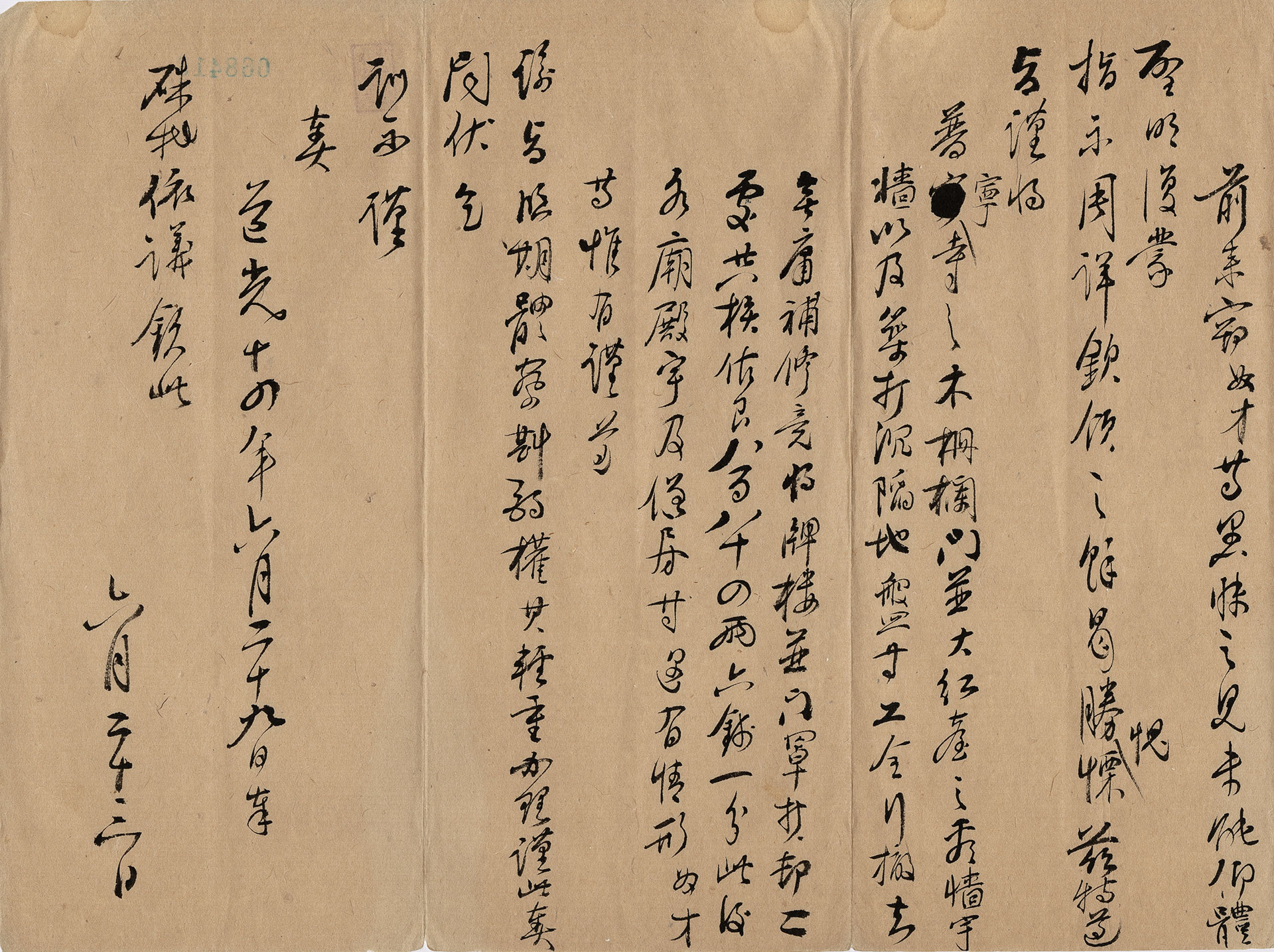

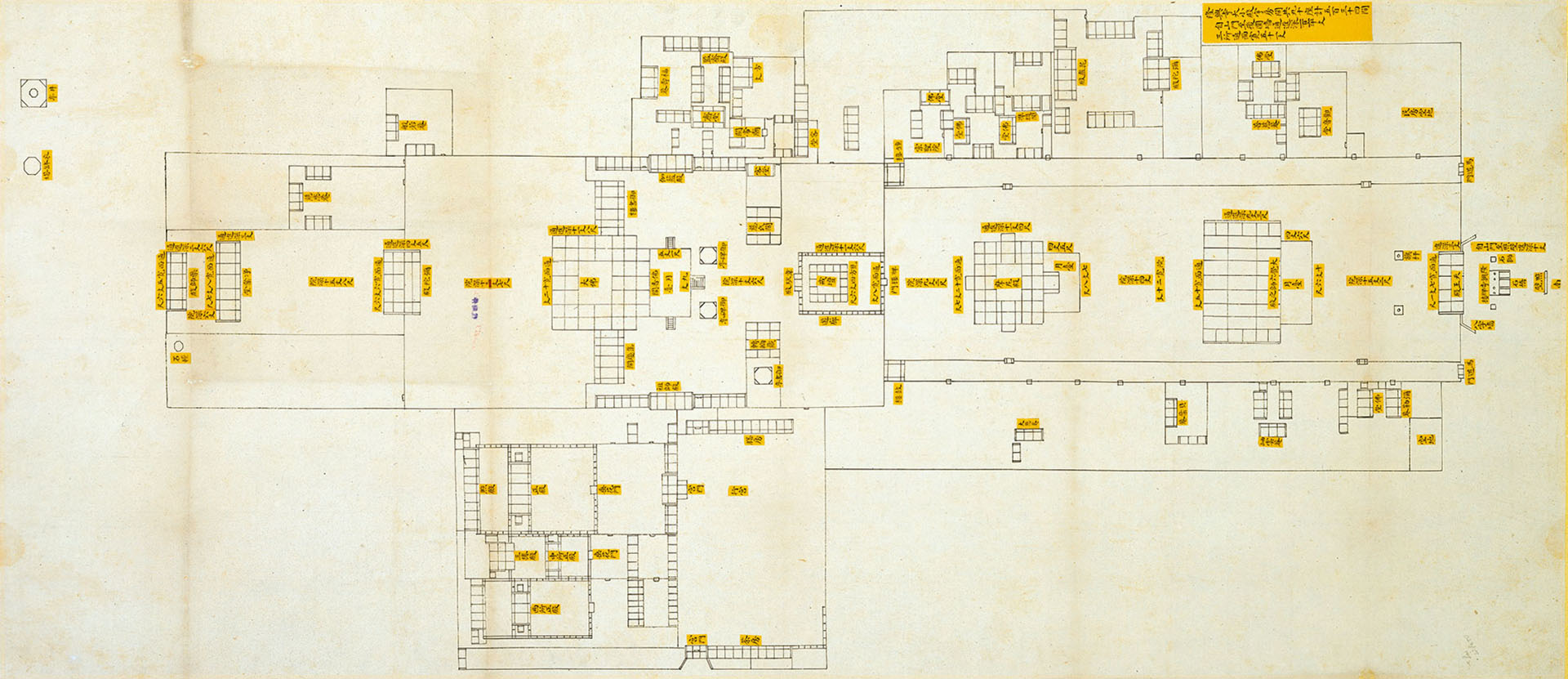

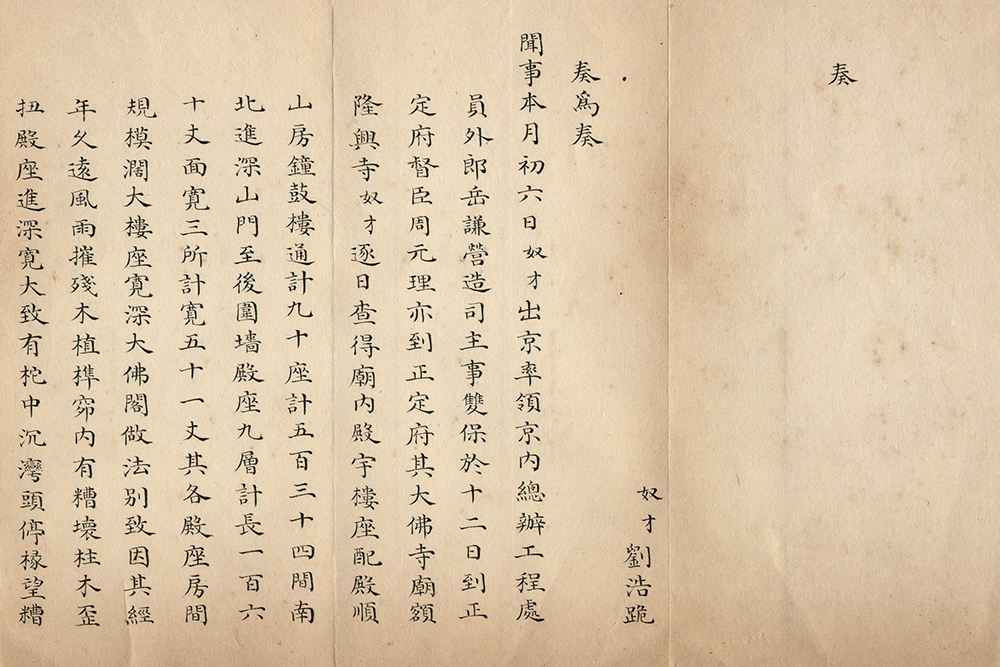

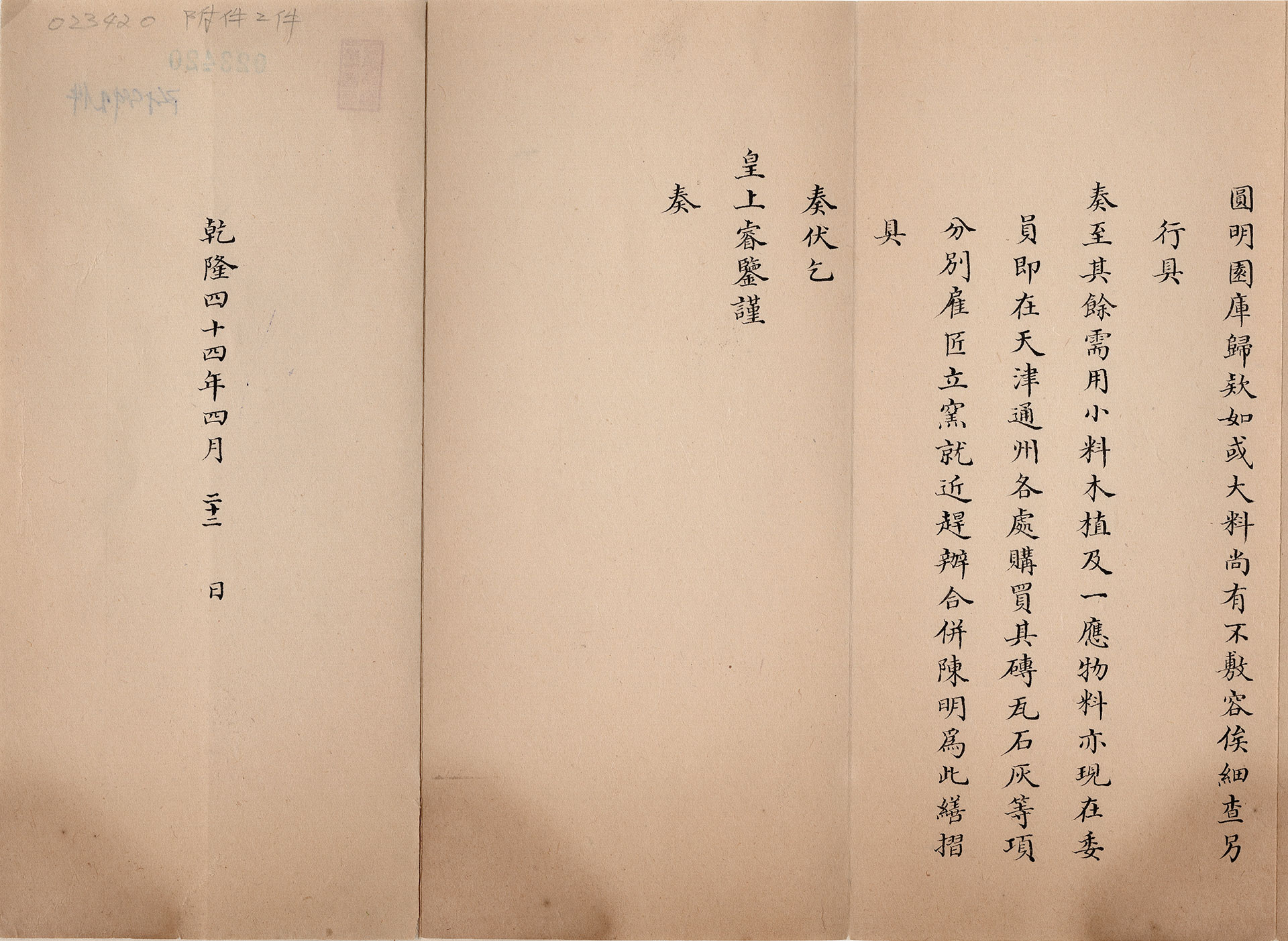

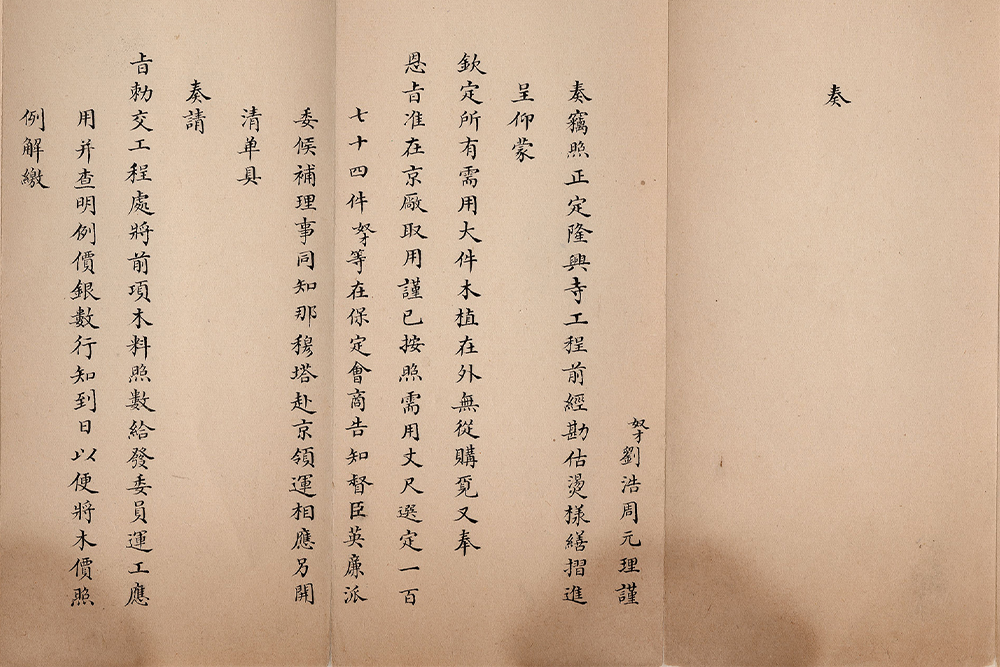

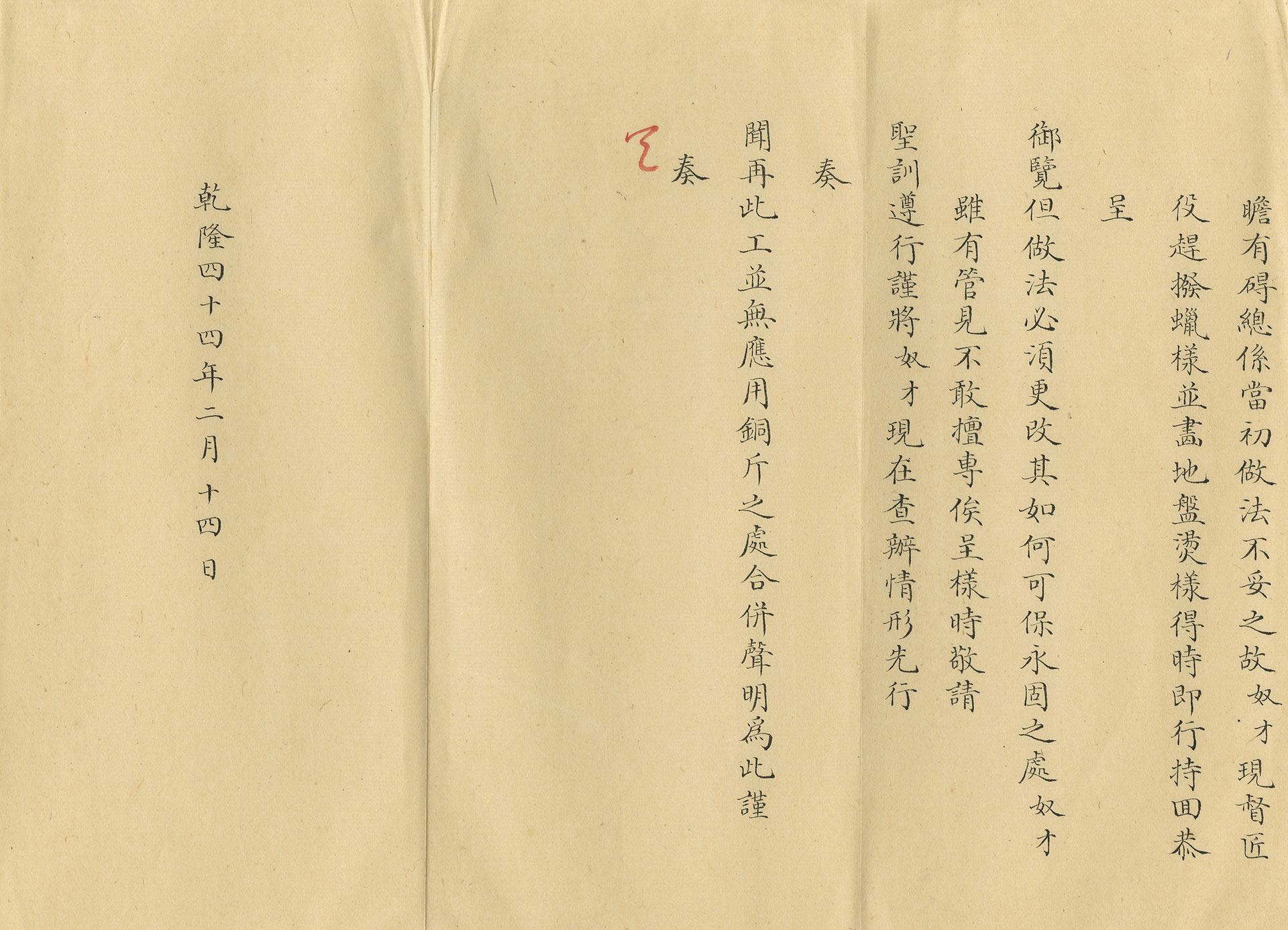

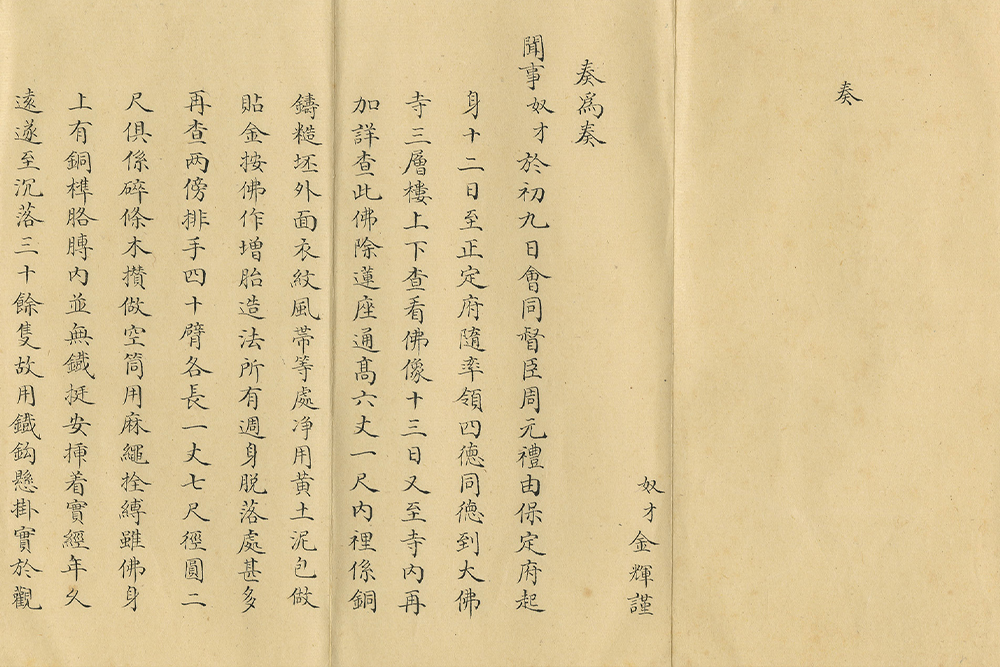

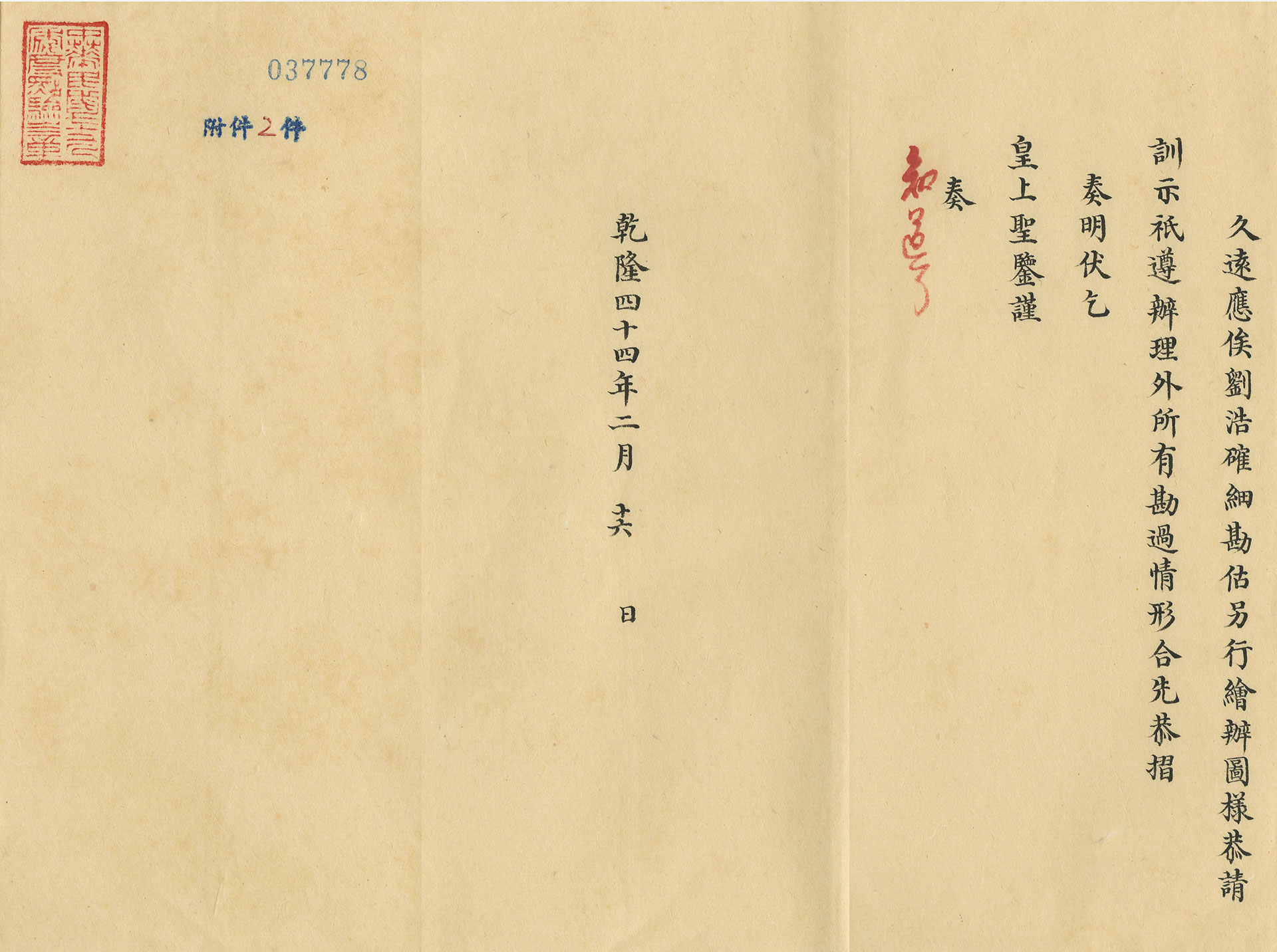

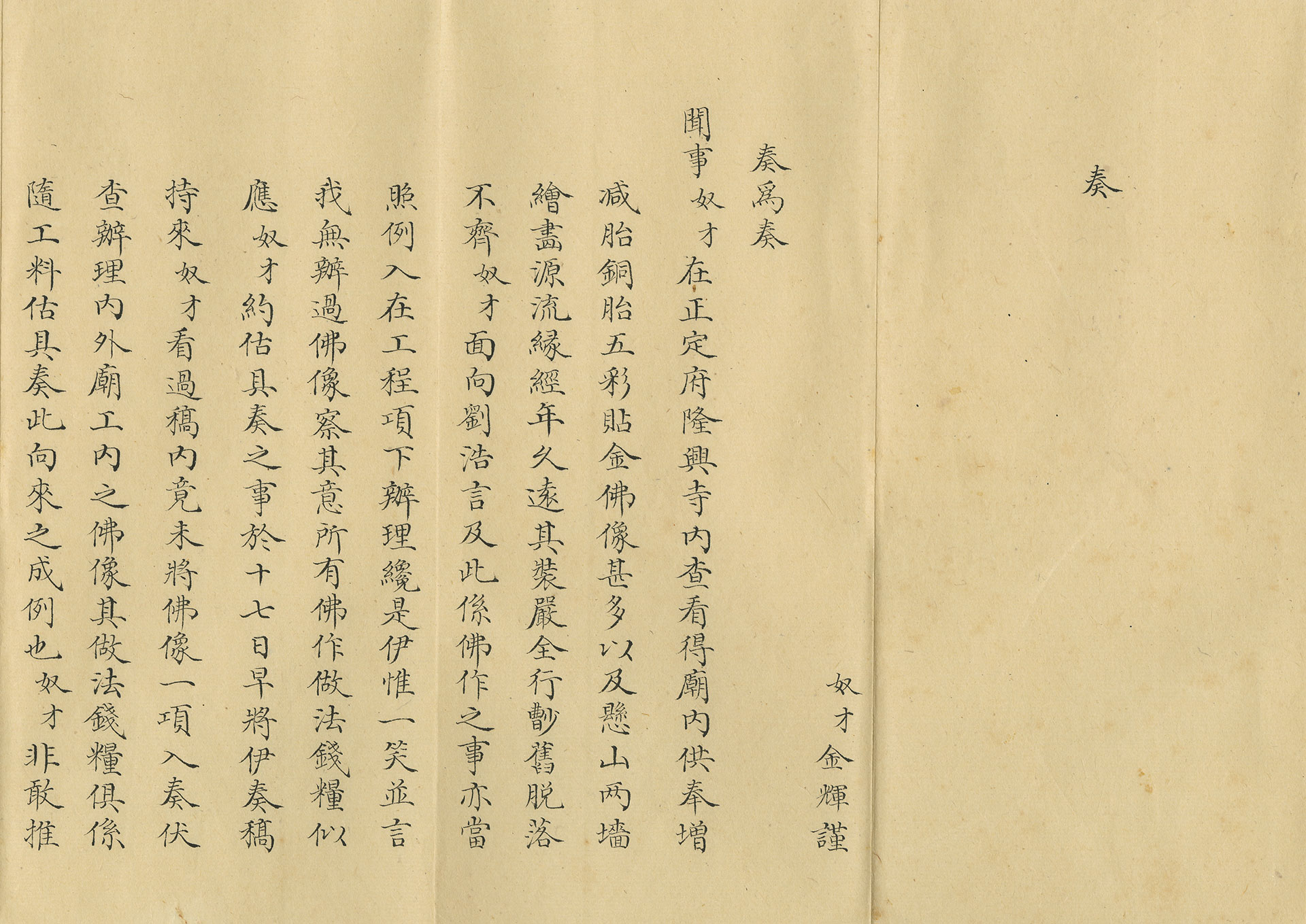

The layouts of the eastern, central, and western sections of the temple were created during a revamp in 1709. The eastern section was where the monks lived, the central section was where Buddhist activities took place, and the western section was where the emperors temporarily resided during their western inspection tours to Mount Wutai. Emperor Qianlong visited the temple many times after coming to the throne, and ordered that renovations be made periodically; the renovation project of the Longxing Temple in 1779 was one of them.

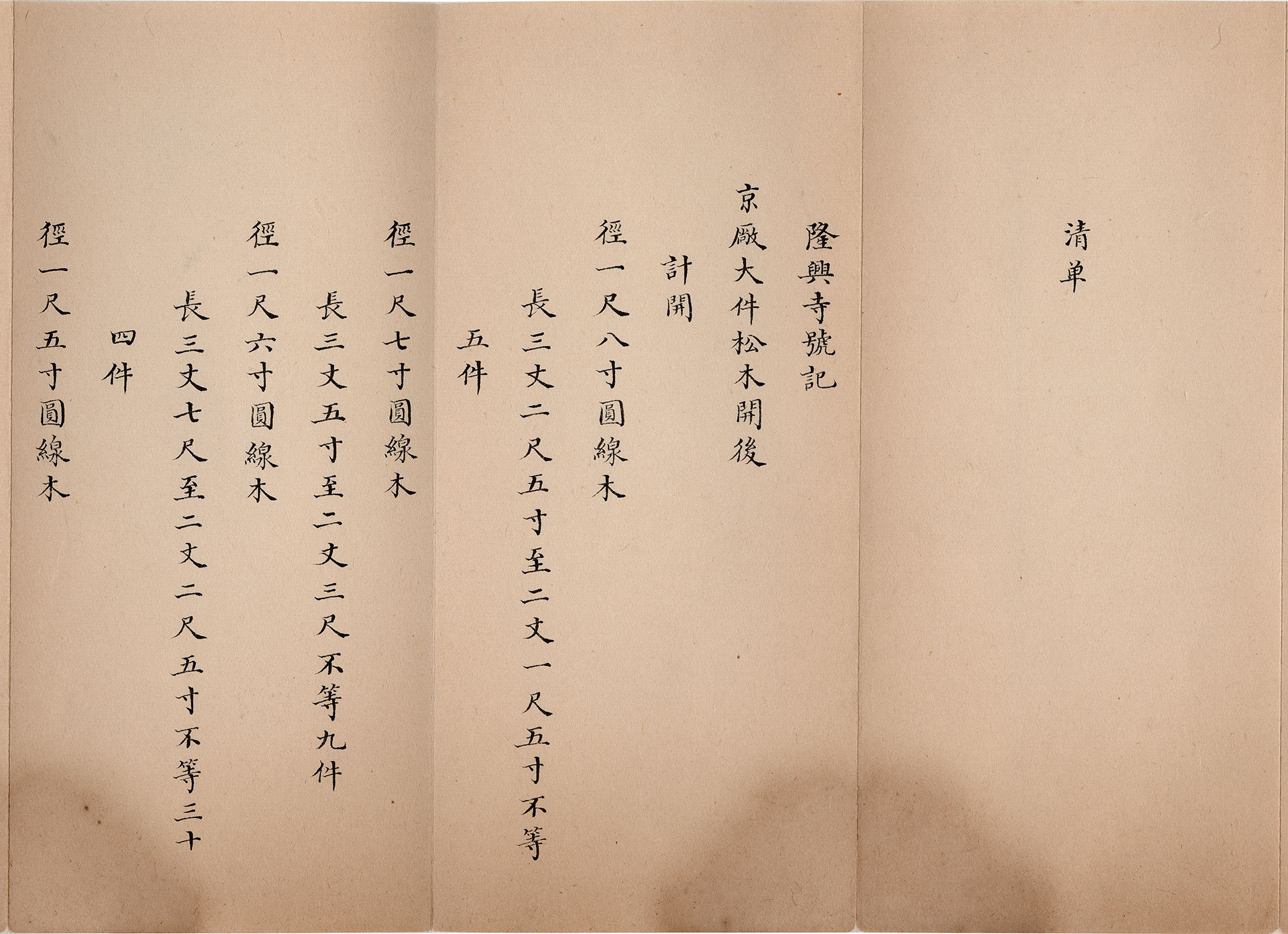

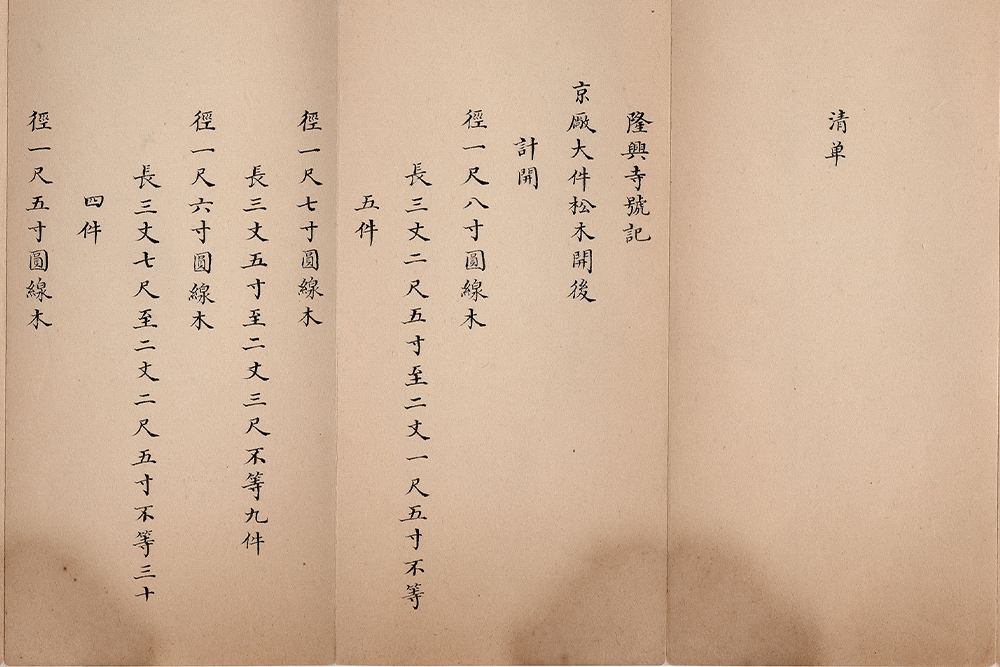

Among the artifacts exhibited here, in addition to palace memorials submitted by government officials and lists of items that the officials had to supervise, the “Longxing Temple Floor Plan” drawn and submitted by Liu Hao-hui, the Imperial Household Department steward in charge of the project, is worthy of attention. The drawing details the names and spatial dimensions of the halls and buildings in the eastern, central, and western sections. The palace memorials also mentioned the presence of stamped samples in addition to drawings. However, the appearances of the stamped samples are currently lost.