Famous Masters, Famous Works

Tapestry and embroidery require not only a long time to make but also the acquisition of considerable skill to turn them into outstanding works of art. However, rarely did artisans in these two art forms leave behind their names on works, and even fewer of them became famous over the ages. Of the names left on surviving tapestries, those of renown include Shen Zifan and Zhu Kerou of the Song dynasty, while in the Ming dynasty ladies from the family of Gu Mingshi became most famous for Gu embroidery. Nonetheless, even if many large scrolls do not retain the name or seal of the masters who made them, they are still highly representative of their respective period and aesthetics, making them canons of famous masters and famous works.

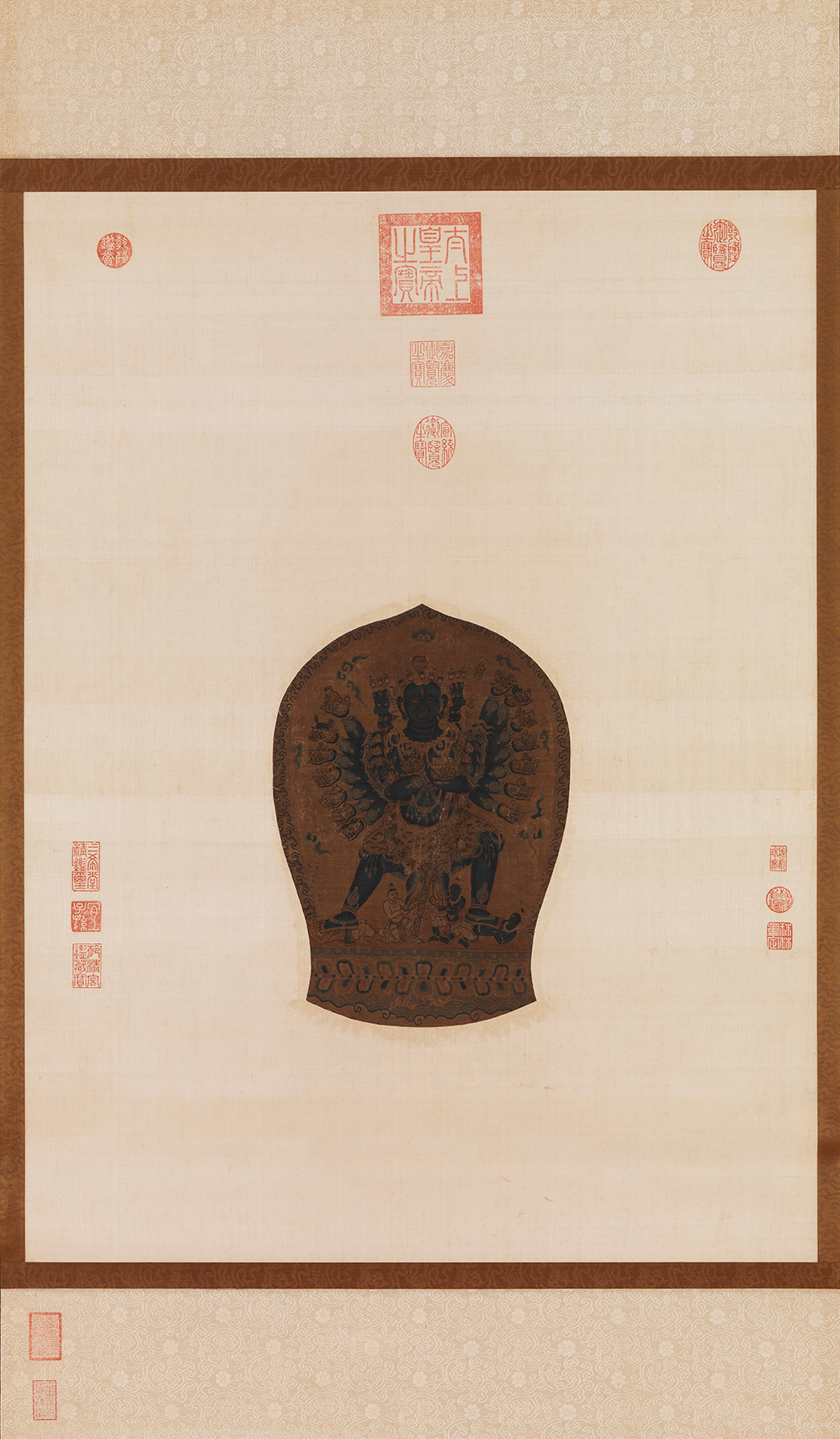

Hevajra

- Anonymous, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

- Hanging scroll, silk tapestry

Hevajra is one of the five major Vajra deities in Tantric Buddhism and serves as an yidam (deity for meditation) to protect Tantric practitioners. The figure has dark blue skin, the upper body exposed, the waist wrapped with a tiger skin, a long vajra staff, a necklace of skulls of the demons conquered, eight faces, sixteen arms, and four legs; it is also shown in a stance leaning on top of four vanquished demons upon a lotus pedestal. The weaving is very detailed, making it one of the few surviving masterpieces of Yuan dynasty Buddhist tapestry.

This work was once reworked by the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) court. The original may have been a traditional rectangular thangka that had been damaged when it entered the collection and thus remounted in its current format. Starting in the Southern Song period, Tibet and Xi Xia often ordered Buddhist silk tapestry images from the Hangzhou region. With its archaic and simple style, the shape of the halo here is similar to Buddhist sutra woodblock illustrations of the Yuan dynasty, suggesting a production of about the 14th century.

Commencing the New Year

- Attributed as anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, silk embroidery

The title in Chinese indicates a combination of tapestry and embroidery, but close examination shows that it differs from tapestry and does not have the "saw-tooth" gaps often associated with it, instead featuring the wrapped-gauze needlework for the embroidery. In fact, the work as a whole is mainly done in wrapped gauze embroidery. In addition to the use of silk gauze as a base being more appropriate for such a technique, the amount of time and effort to make this work was quite considerable. The enormous size indeed makes it extraordinary.

A child wearing Mongolian-style clothing is shown riding on a goat. Two other children accompanied by eight other goats form a composition that serves as a homophone for the auspicious message of "Nine goats commencing the New Year." This and another tapestry entitled "Welcoming Spring" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City were probably once part of a set. The formulaic plants here are beautiful and the embroidery outstanding, representing a masterpiece of the Yuan to Ming period and perhaps related to Mongol Yuan imperial weaving.

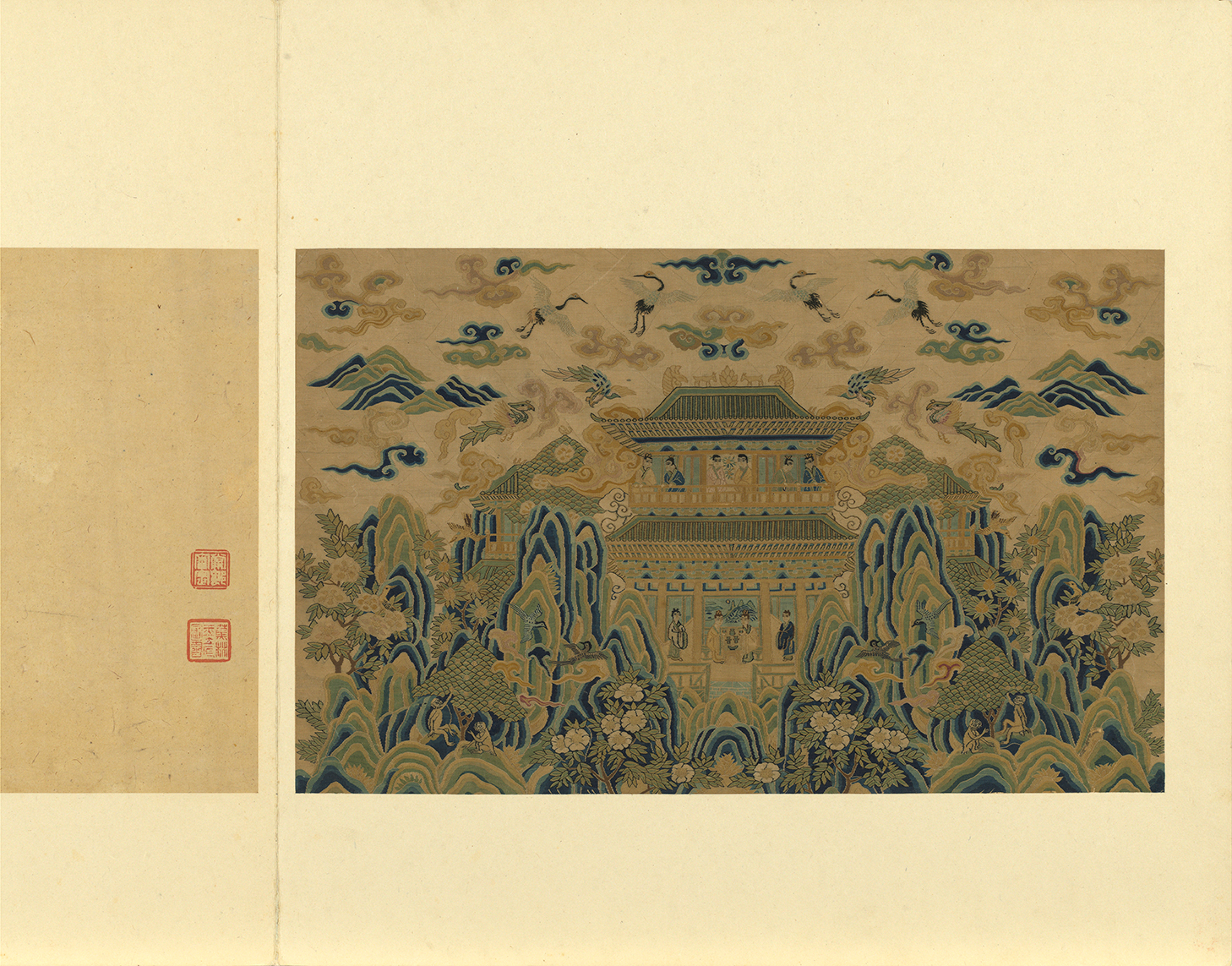

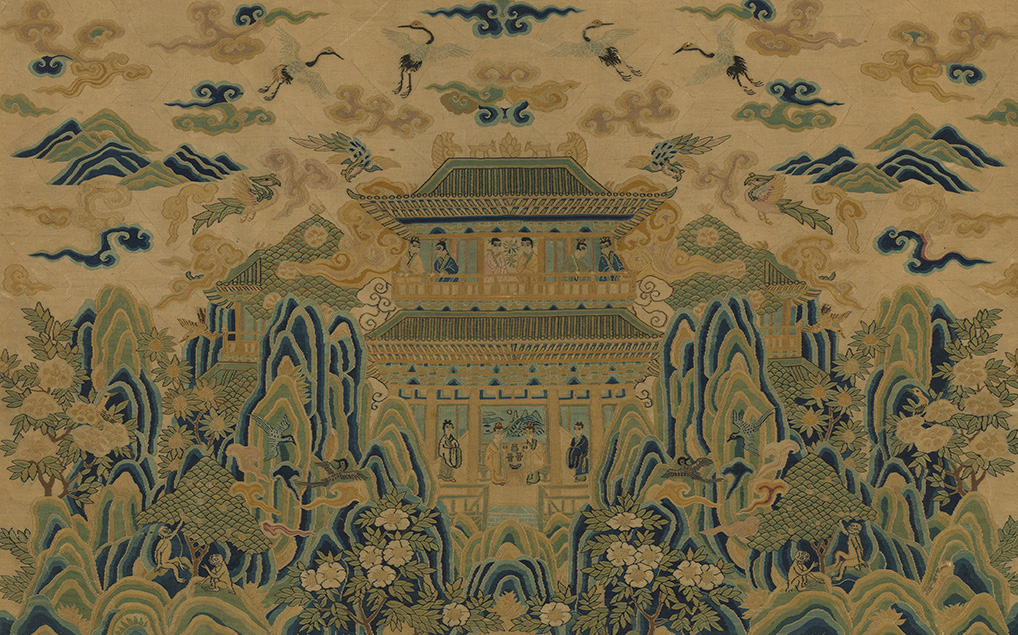

Hall in the Mountains of Immortals

- Anonymous

- Album leaf, silk tapestry

Woven in tapestry here is a palatial hall in a "blue-and-green" landscape. Layers of rocks in the foreground are interspersed with exotic flowers and fantastic trees, among which monkeys and birds appear. The hall stands above a valley, the skies filled with various colored clouds, white cranes, and colorful phoenixes encompassing an atmosphere of the immortals. This work takes a symmetrical approach to arranging the composition, the elements also more patterned. With various tapestry techniques, the turning threads express considerable liveliness.

In addition to appreciation, tapestries also functioned as wrapper headings for painting and calligraphy, being used for mounting the back of handscroll headers. Depending on the contents, the textile pattern used for the headers of painting and calligraphy also differed. This silk tapestry of a hall in the mountains of immortals is such an example, from which we can surmise the situation with multifunction purpose of textiles at the time.

Wagtail

- Zhu Kerou (fl. 1127-1162), Song dynasty

- Album leaf, silk tapestry

A solitary wagtail is woven standing on a rock in a stream against a light brown background as it looks at shrimp stuck in the cracks between the rocks below; butterflies flit in the area above. The weaving here employs an extended variation of the "long and short propping" method to create the effect of haloed colors, the multilayered hues for the feathers of the wagtail and the transparent glossiness of the shrimp's underside both rendered in a highly saturated manner.

Woven into this work is a seal that reads, "Zhu Kerou yin (Seal of Zhu Kerou)." Zhu Kerou, or Zhu Gang, is said in inscriptions from the Ming dynasty to have been a native of Huating (modern Songjiang in Shanghai) active under the Southern Song emperor Gaozong (reigned 1127-1162) and renowned for needlework. As a result, later generations often came to consider this artisan as an outstanding example of a Song dynasty lady tapestry master. However, surviving works with Zhu Kerou's name vary somewhat in quality as well as style, suggesting the later production of many spurious attributions.