Pure Sounds of the Landscape

Only scattered fragments of Chinese tapestry and embroidery survive from early times and most come from objects of practical or decorative purposes. Starting in the Song period, however, tapestry and embroidery became intimately associated with contemporary customs, religious beliefs, and painting styles of the period in which they were produced. For example, embroidered painting became a specialized branch at the court during the reign of Emperor Huizong (1082-1135) in the Northern Song and was divided into landscape, building, figure, and bird-and-flower subjects, gradually turning into an art form prized for both viewing and collecting. Starting in the Yuan and Ming dynasties, embroidery and tapestry, as in painting, developed their own unique characteristics. Artisans transformed threads of silk into images using the needle or shuttle as their brush to create amazing compositions of outstanding colors. With mountains lofty and majestic, the sound of flowing waters, and ascending heights by the water's edge, the landscape works they made pale in no way compared to paintings.

The Poetic Intent of Autumn Mountains

- Attributed to Shen Zifan, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, silk tapestry

The landscape arrangement in this tapestry follows one often used in Chinese painting and known literally as "one river, two banks." In the foreground, a scholar sits by the opening on one side of a building perched atop a cliff as he looks out at the view. The composition in fact is very similar to that of landscape paintings from the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) and later, making the actual date of production for this tapestry open to debate.

Three related landscape tapestries are in the National Palace Museum collection. In addition to this work, one given to Shen Zifan entitled "Landscape" is similar in composition but different in coloring, while an anonymous one has the composition reversed. The other two works are also on display in this exhibition. The coloring of this tapestry is subtle and the structure of the elements clearer, fully demonstrating mature weaving techniques that suggest it is earlier.

Landscape

- Attributed as anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, silk tapestry

The contents of this tapestry are identical to one attributed to Shen Zifan entitled "Landscape," except that they are reversed. This demonstrates one of the most distinctive features of tapestry, which is that either side of the weaving can serve for appreciation.

The colored silk threads in this work are brighter and livelier. The artist, however, probably was less gifted at imitating the direction of weft threads in the Shen Zifan attribution to recreate the images, leading to parts of this landscape being distorted and unnatural. The change in colors is also more abrupt with the weft colors less harmonious, the weaving not as tight and appearing more flaccid. Brushwork was added to the outlines of some tree trunks, the tree leaves, boat, and facial features here.

Ocean House Adding Markers

- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, silk tapestry

This tapestry of the Penglai isle of immortals features a beautifully ornamented building with cranes of immortality in the sky, symbolizing a realm where spirits dwell. Despite the small size of the work, the weaving and use of colors is exceptionally fine. The rocks, buildings, figures, plants, and animals are all in a patterned style that is simplistic yet richly detailed. Brushwork was added to the areas where silk threads for the rocks and figures had been damaged.

According to Dongpo's Forest of Records , "Three elders met and asked each other about their age. One said, ‘When ocean waters turn to mulberry fields, I place a chip [in my house to mark the change]. Now the markers fill ten houses.'" For this reason, "ocean house adding markers" is used as an expression in birthday greetings to wish longevity. A colophon by Yu Ji (1272-1348) dated to 1344 is mounted above the tapestry here.

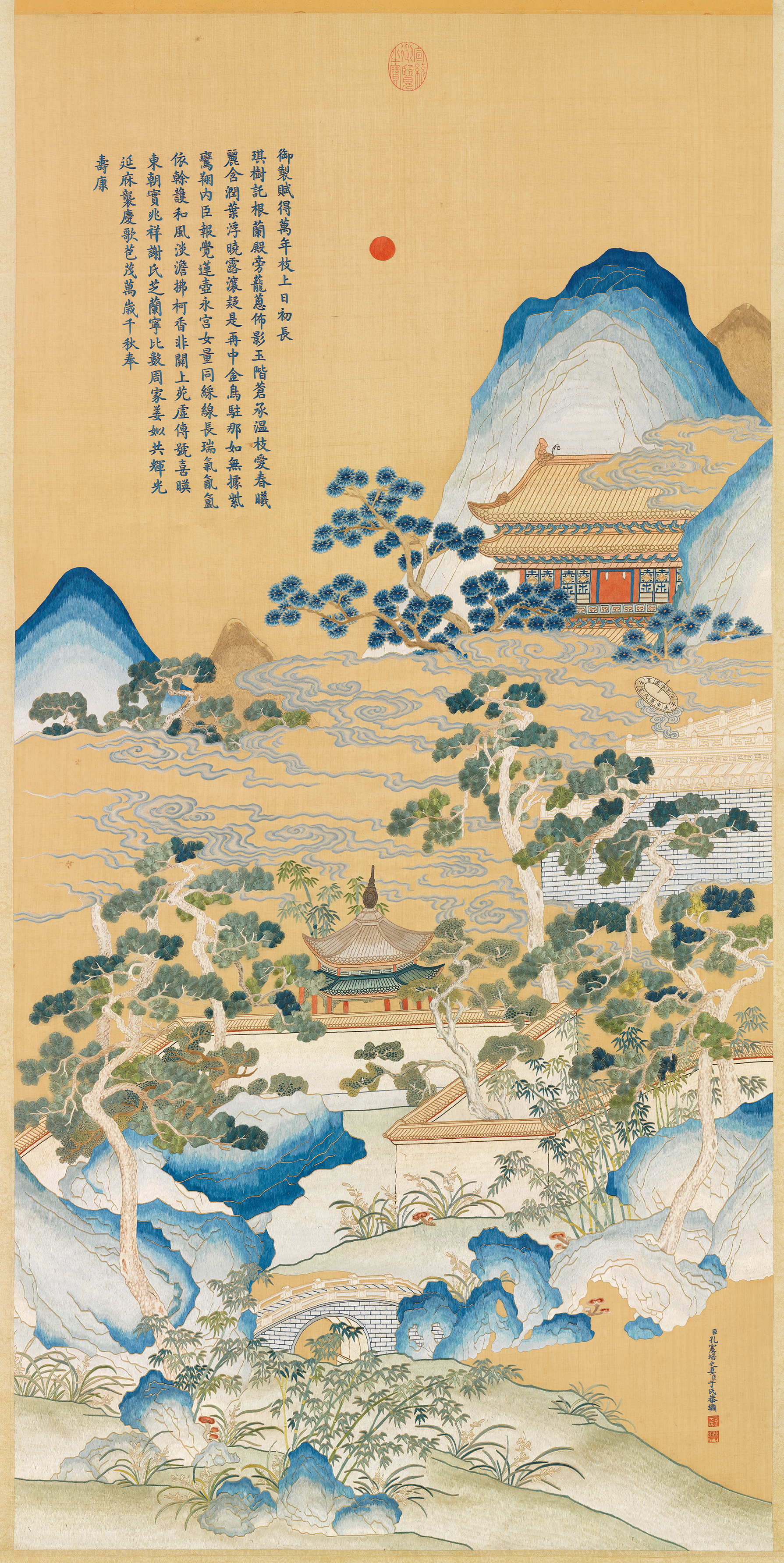

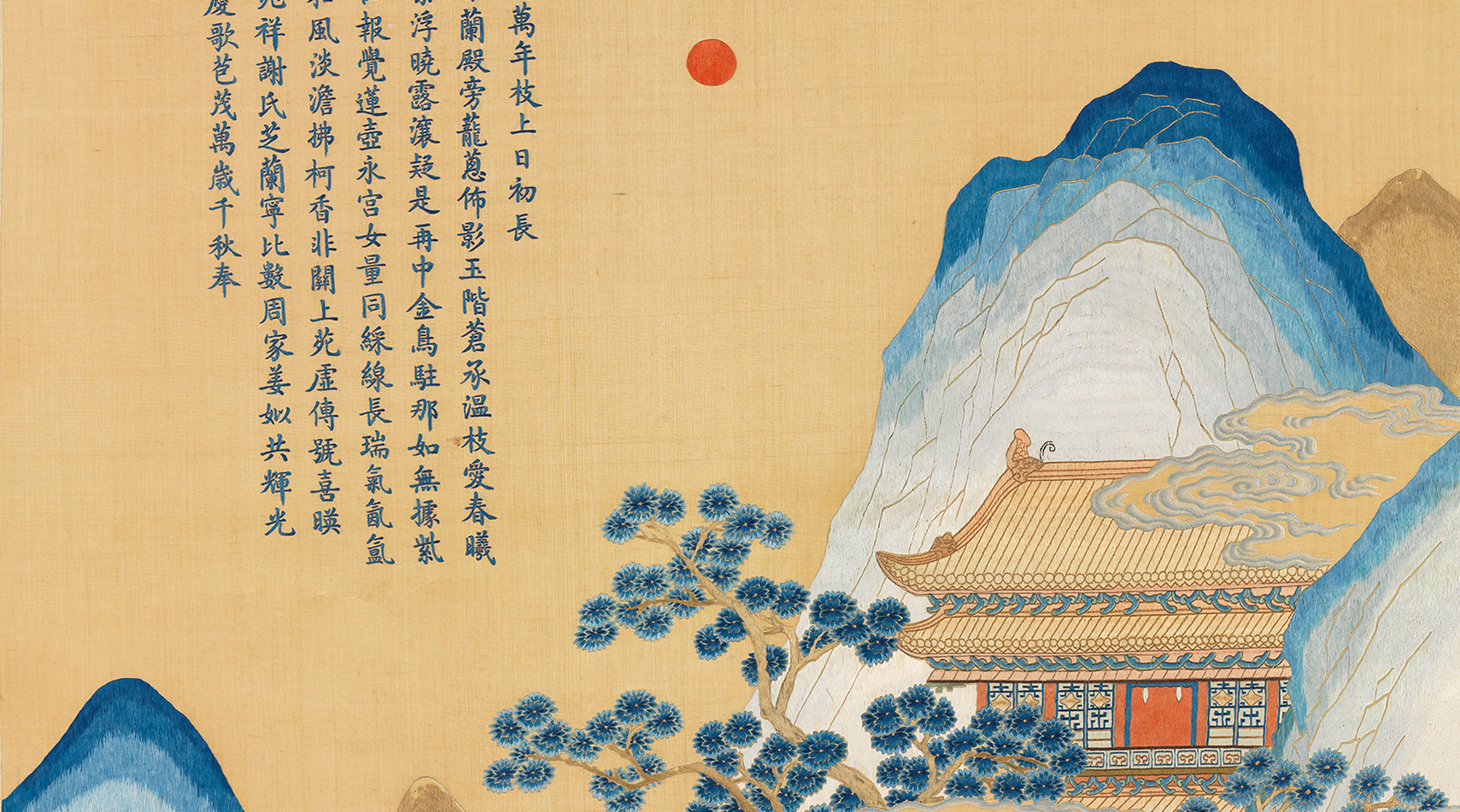

Respectfully Embroidering the Poetic Intent of the Imperial "Sun Rising Over Ancient 'Branches'"

- Lady Yu, Qing dynasty (1644-1911)

- Hanging scroll, silk embroidery

On a plain silk damask background is embroidered an image in multicolored threads of a pavilion and hall with the sun figuring prominently above a landscape surrounded by clouds and mists as well as spirit fungi, pines, and bamboo scattered here and there. Appearing on a terrace in the right middleground is an instrument used in ancient times to mark the time using twelve cyclic "branches," hence the title. The method of embroidering here is exceptional, the areas between the outlines left blank to create gradated coloring that suggests a sense of volume to the forms. The colors throughout are also bright and beautiful, the fine glossy silk strands extremely eye-catching. The fine needlework makes this a masterpiece of Qing dynasty embroidery from the Qianlong period (1736-1795).

Kong Xianpei (1756-1793) was the 72nd-generation descendant of Confucius. His wife (maiden name Yu) excelled at embroidery and made this work; her birth and death dates as well as other biographical information are unknown.