Norms of Female Beauty

The standards of female beauty in China have changed much over the ages and reveal major differences. The paintings in this part of the exhibition are divided among three display areas and offer audiences a way to appreciate evolving norms of beauty in Chinese history. They include the plump robustness of palace consorts in the Tang dynasty, the dignified grace of Song dynasty ladies, and the delicate features of Ming and Qing dynasty beauties that lean toward effeminate weakness. On the surface, many of these works are captivating for their technical virtuosity in the skill of depiction, but behind the imagery in some of them lie complicated and poignant stories of women. After viewing the artworks, "she" is sure to linger in the mind and encourage reflection on deeper meanings.

A 21st-century perspective to reexamine various forms of feminine beauty from the past can enlighten people today about the subjectivity of aesthetic standards. While we cannot change the fate of these ancient ladies, our understanding of their situation can help adapt our own view of women today and promote further harmony in gender relations of the future.

Inculcating the Infant

- Attributed to Zhou Fang (fl. late 8th c.), Tang dynasty

This work, attributed to the famous Tang figure painter Zhou Fang, depicts a group of noble women. Their hair is tied into knots, and long dresses with sashes are draped over their shoulders, which is typical attire of Tang dynasty ladies. With considerable grace and composure, the figures play a variety of musical instruments, such as the konghou harp, bamboo flute, pipa lute, and guzhen zither. A wet-nurse also holds a baby in her arms, her expression apparently in tune with the music in this painting of ease and elegance.

To maintain their vested interests, the nobility in ancient times placed great emphasis on the education of their children. This painting shows female members of such a household scene educating the young. Ms. Chang Wei-chen, the wife of Lo Chia-lun, donated this painting to the National Palace Museum.

Women of the House Playing Double Sixes

- Attributed to Zhou Fang (fl. late 8th c.), Tang dynasty

Women of the House Playing Double Sixes

"Double sixes" was a kind of board game played by two people that originated in ancient India and popular in Tang dynasty China. Based on "Biographies of Eminent Ladies at the Court" in Former Book of the Tang and lines of verse by Tang dynasty poets, it appears to have been a game enjoyed by members of the court and upper classes at the time. In this painting are two full-figured opulent ladies of the nobility seated before a board game with a couple of attendants who are intently observing the next move, giving the leisurely match a subtle touch of tension. The crescent-shaped stools on which the ladies sit are often seen in depictions of Tang dynasty ladies.

A Lady

- Attributed to Zhou Wenju (10th c.), Five Dynasties period

Zhou Wenju, a native of Jurong (modern Nanjing) in Jiankang, served as a Hanlin Academician-in-Waiting for the Southern Tang ruler Li Yu, who was also known as Houzhu. Zhou excelled at painting figures with elaborate attire and accessories. His brushwork was fine and angular, yet the strokes mature and fluid, sometimes with a trembling movement in a style of his own. Though his lady paintings followed closely after those by Zhou Fang of the Tang dynasty, Zhou Wenju's are finer and more opulent.

This painting depicts a paulownia tree, under which appears a lady leaning on a rail and reading. To the side is a cat accompanying her. The painting is not signed and the taut and angular twists of the drapery lines differ from the style of Zhou Wenju, so the title with the artist's name is considered to have been added at a later time.

Washing the Moon

- Anonymous, Five Dynasties period (907-960)

This hanging scroll bearing neither seal nor signature of the artist has a traditional title indicating it is an anonymous painting of the Five Dynasties period. It depicts a moon aloft in the sky as winding pine and paulownia trees as well as plantain adorn a courtyard, the leaves rich and luxuriant. Cotton rose, hibiscus, and daisies are blooming together in all their individual beauty. A dragon sculpture sprawls on a large garden rock to the side and leans down as a fountain of water pours from its mouth into a basin below, the water splashing about there. An opulently adorned lady is holding a pearl in her cupped hands as she leans over to wash it in the water. To the side are three attendant ladies, one burning incense, one holding a container, and the other with a wrapped zither. The expressions on their faces are serene. This painting may well have been based on a line of poetry, "A handful of water with the moon in my hand," in "Evening Moon Among Spring Mountains" by the Tang dynasty (618-907) poet Yu Liangshi.

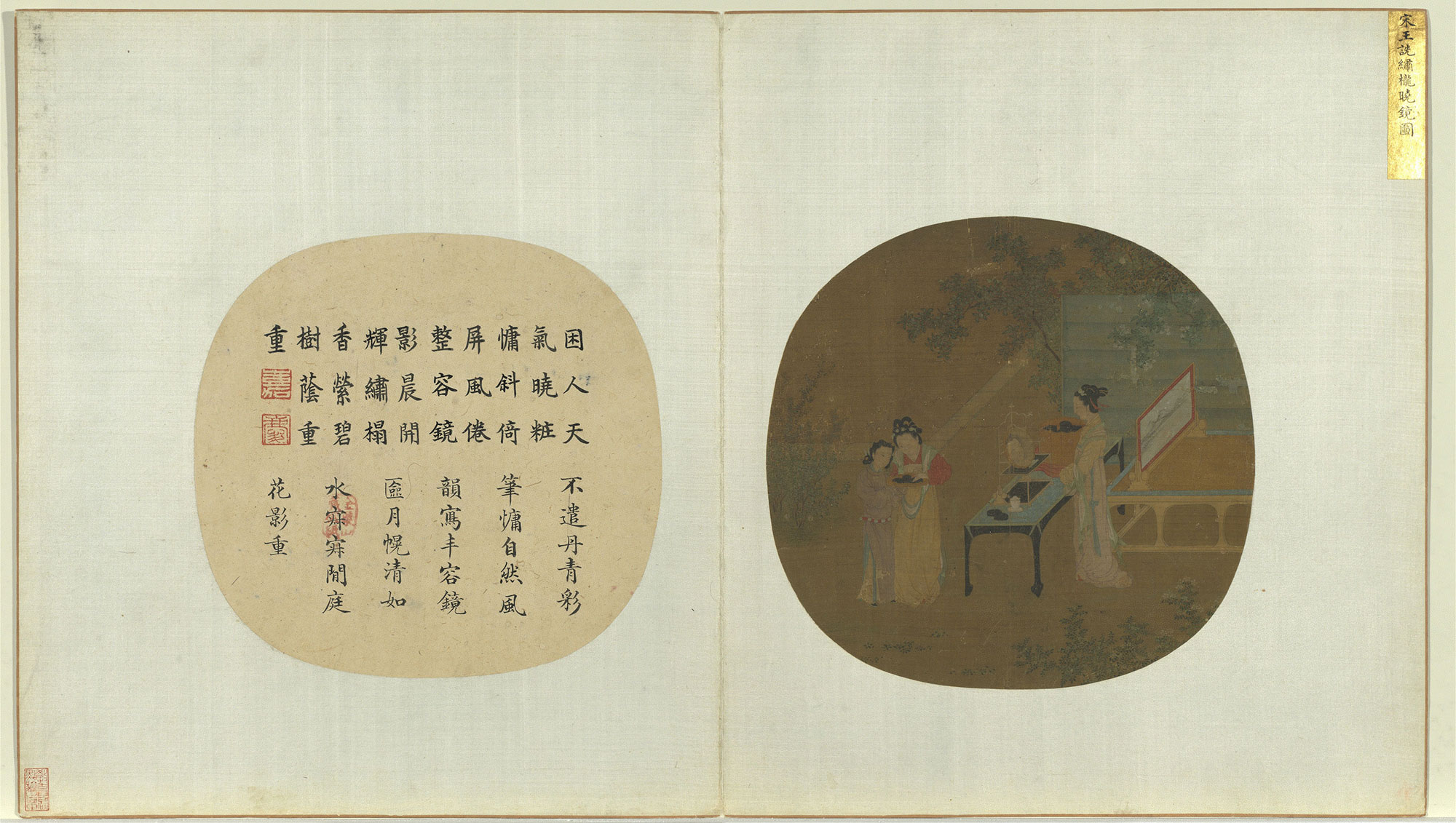

Morning Toilette in the Women's Quarters

- Wang Shen (1036-1099), Song dynasty

This work with neither seal nor signature of the artist has a title slip giving Wang Shen as the painter. However, it differs stylistically from other accepted works by him and is probably from the hand of a court painter sometime during the Song dynasty. The painting is in the shape of a round fan, a format originally of utilitarian function for producing a breeze to cool off. In this case, the fan was later remounted as an album leaf. The scene here is adorned with flowering plants and demarcated by a standing screen. A palace beauty stands in the garden in front of a mirror as two maids hold containers and look down at the makeup within them. Both the figures and scenery are rendered in outlines of painstaking refinement. Though the coloring is complex, it is not without lightness and elegance that fully reflects the aesthetic ideals of feminine grace and reservation in society at the time.

Beauties on an Outing

- Li Gonglin (1049-1106), Song dynasty

This painting is based on the poem "Beauties on an Outing" by the famous Tang dynasty poet Du Fu (712-770). It describes an outing in early spring by nine figures on horseback, one of which is Lady Guo, an elder sister of the infamous consort and beauty Yang Guifei (719-756). The women are plump and robust in appearance with foreheads and noses powdered white as part of the fashion at the time. Their horses are also strong and muscular as the group takes its leisurely time. The forms of the figures and horses, the details of their hair and clothing, and the painting methods and coloring all clearly hark back to a Tang dynasty style.

The painting originally had no seal or signature of the artist, but someone later assigned it to Li Gonglin of the Song dynasty, perhaps because of his fame in depicting figures and horses.

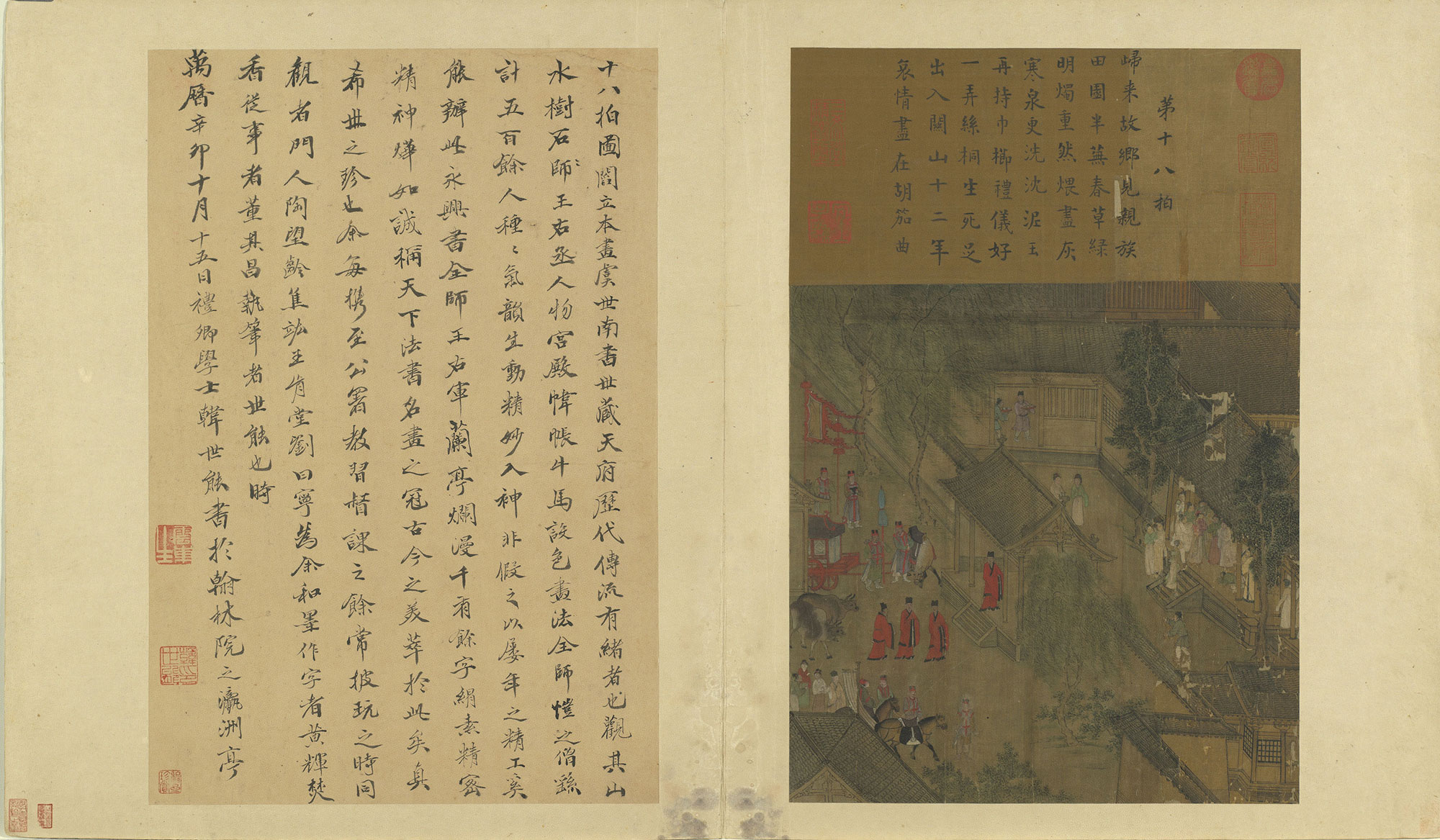

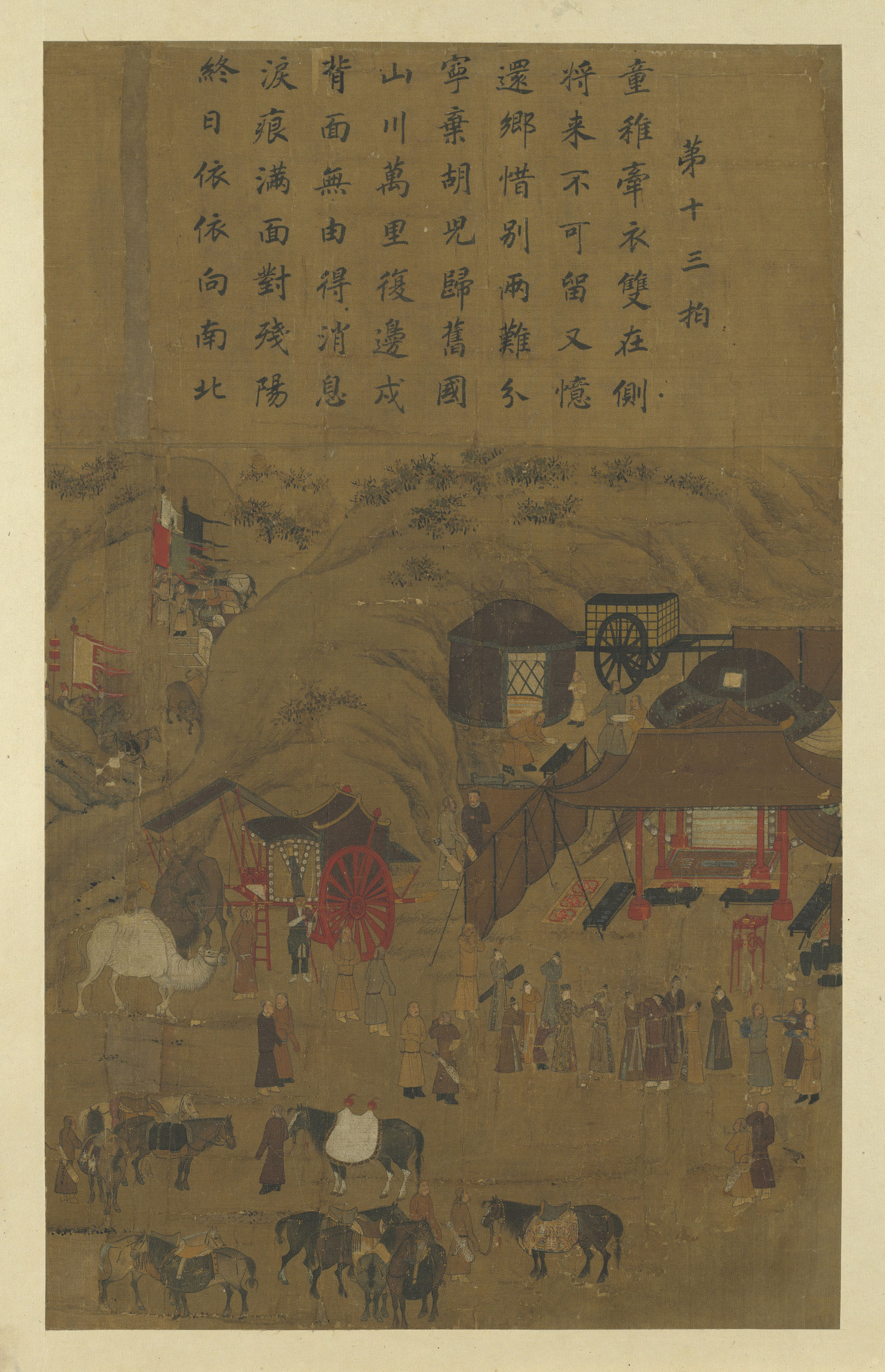

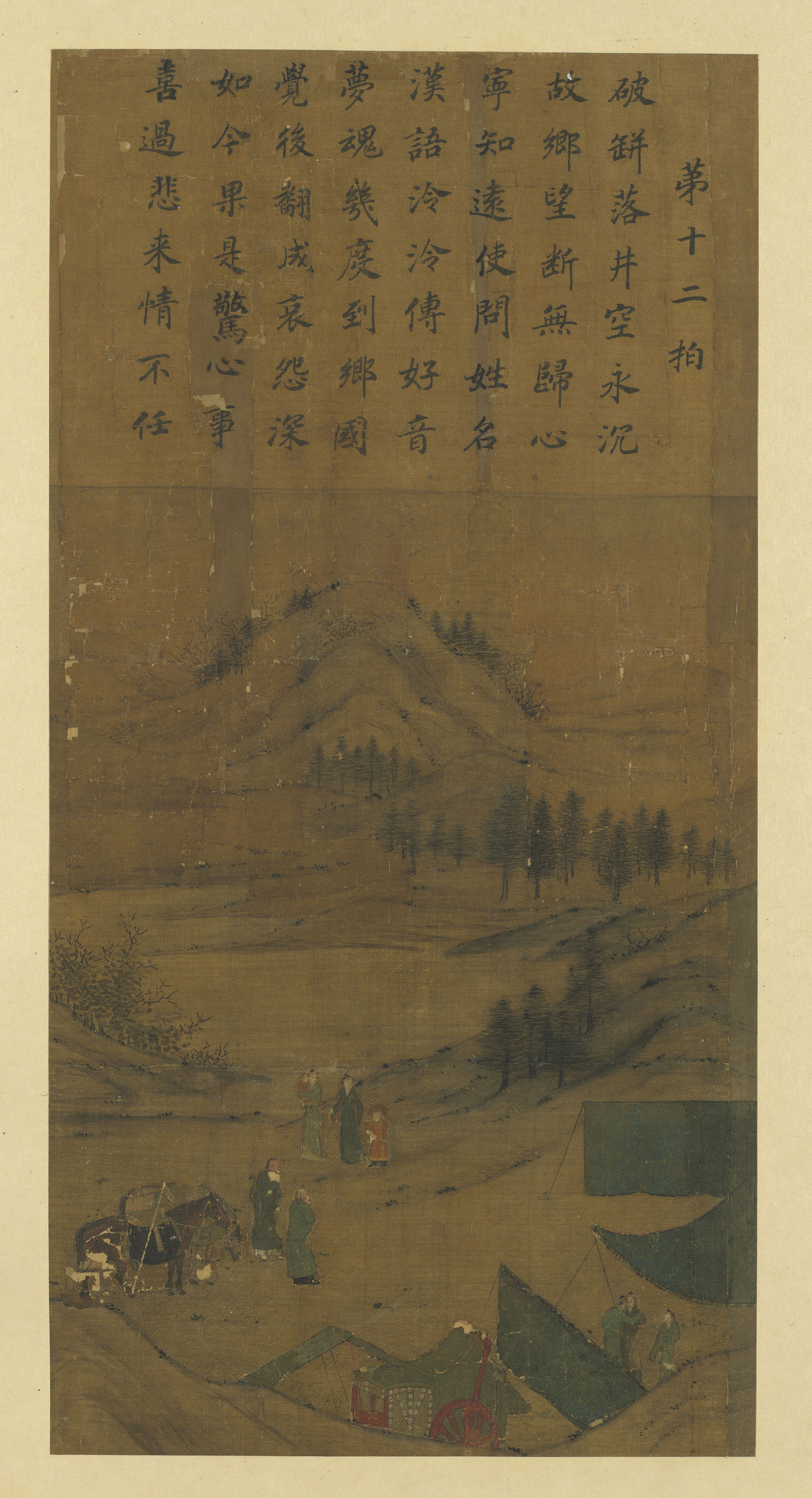

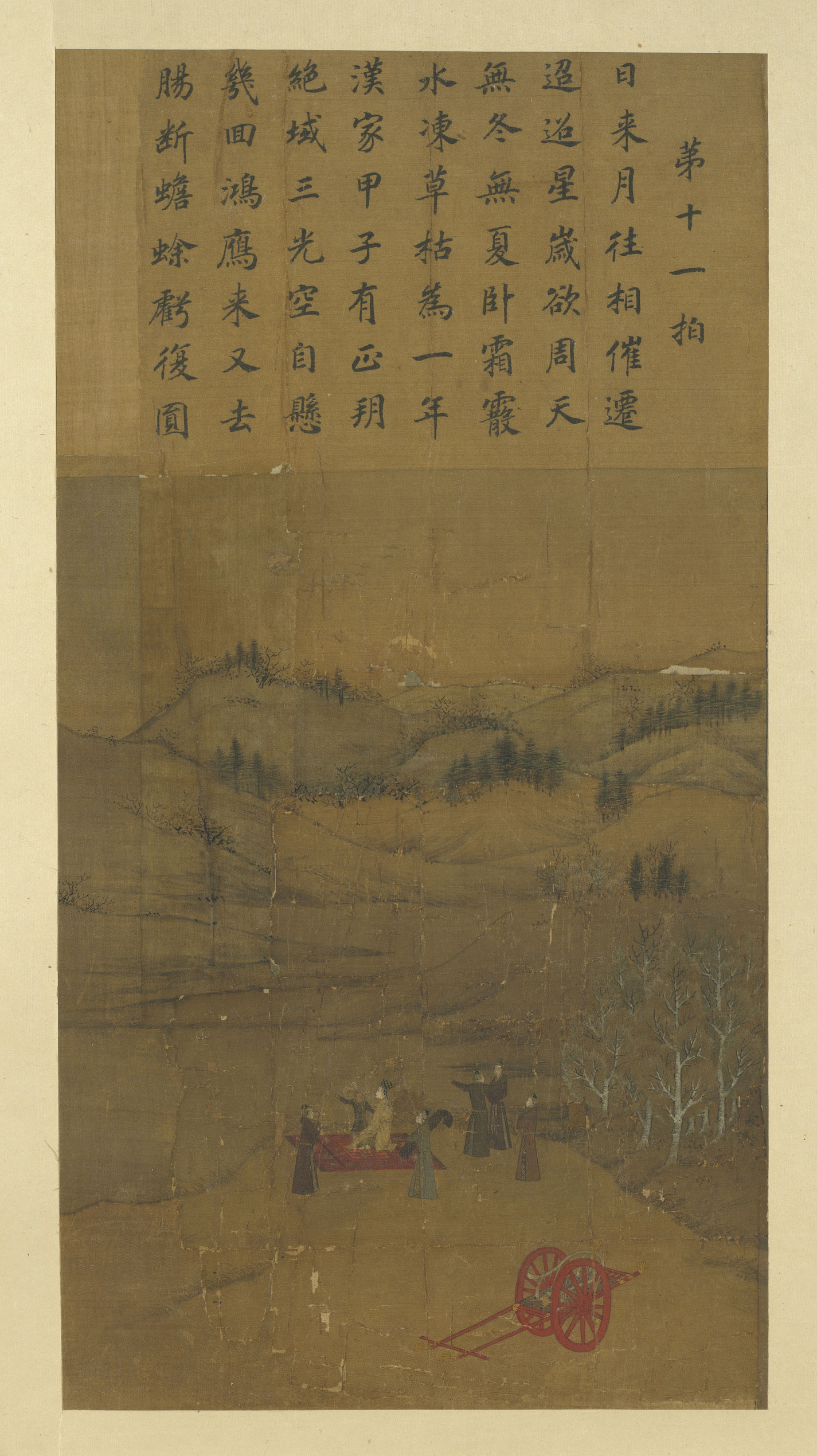

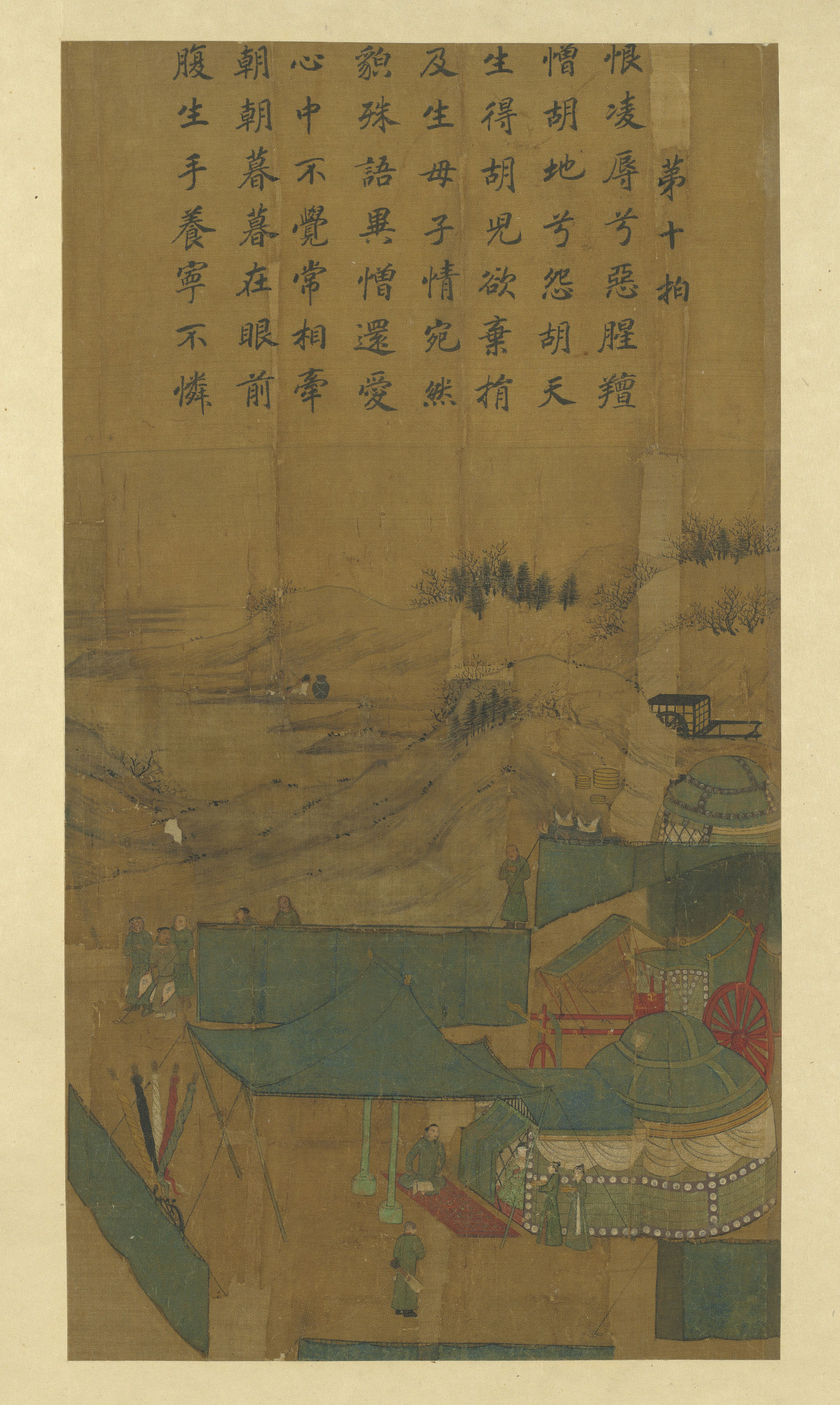

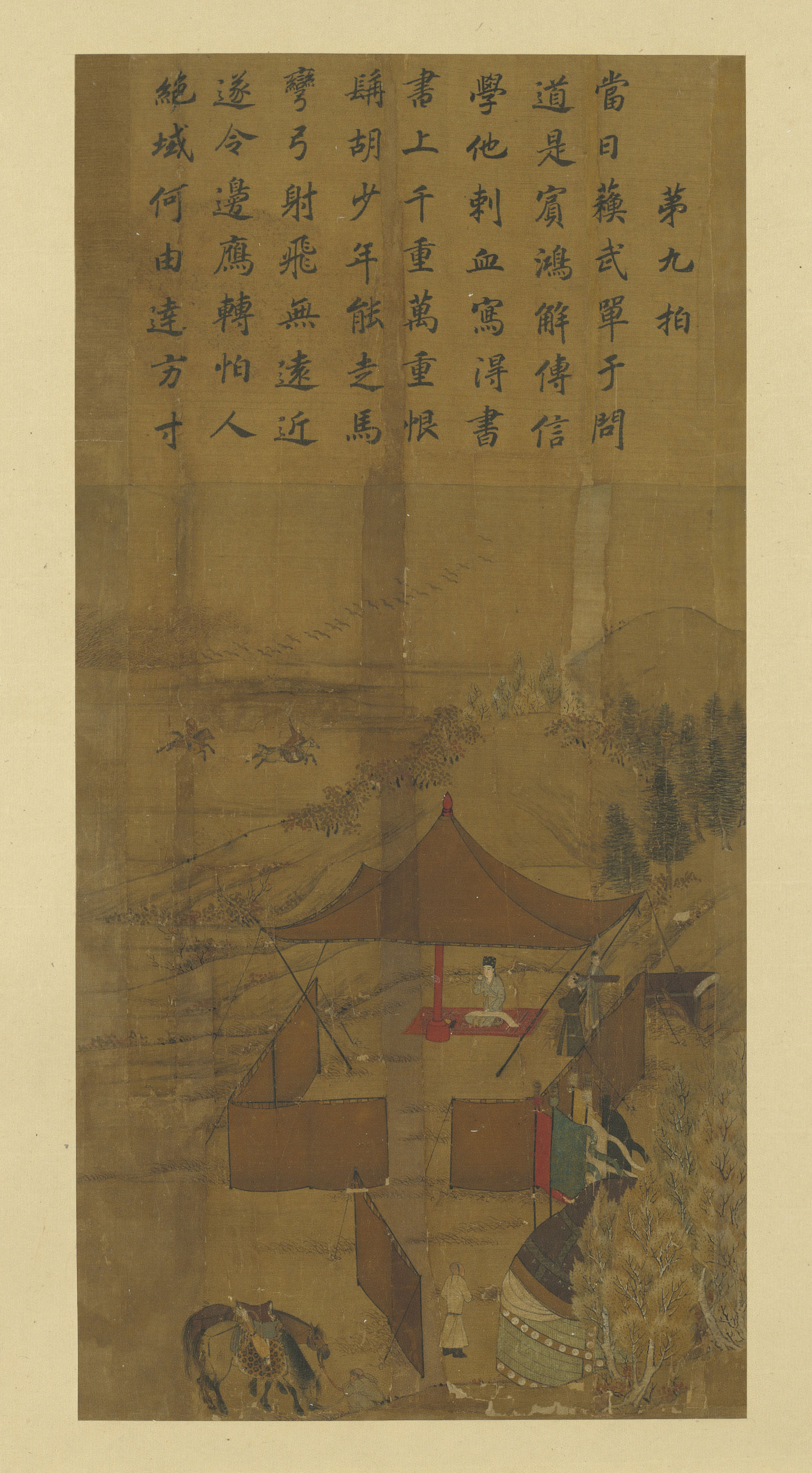

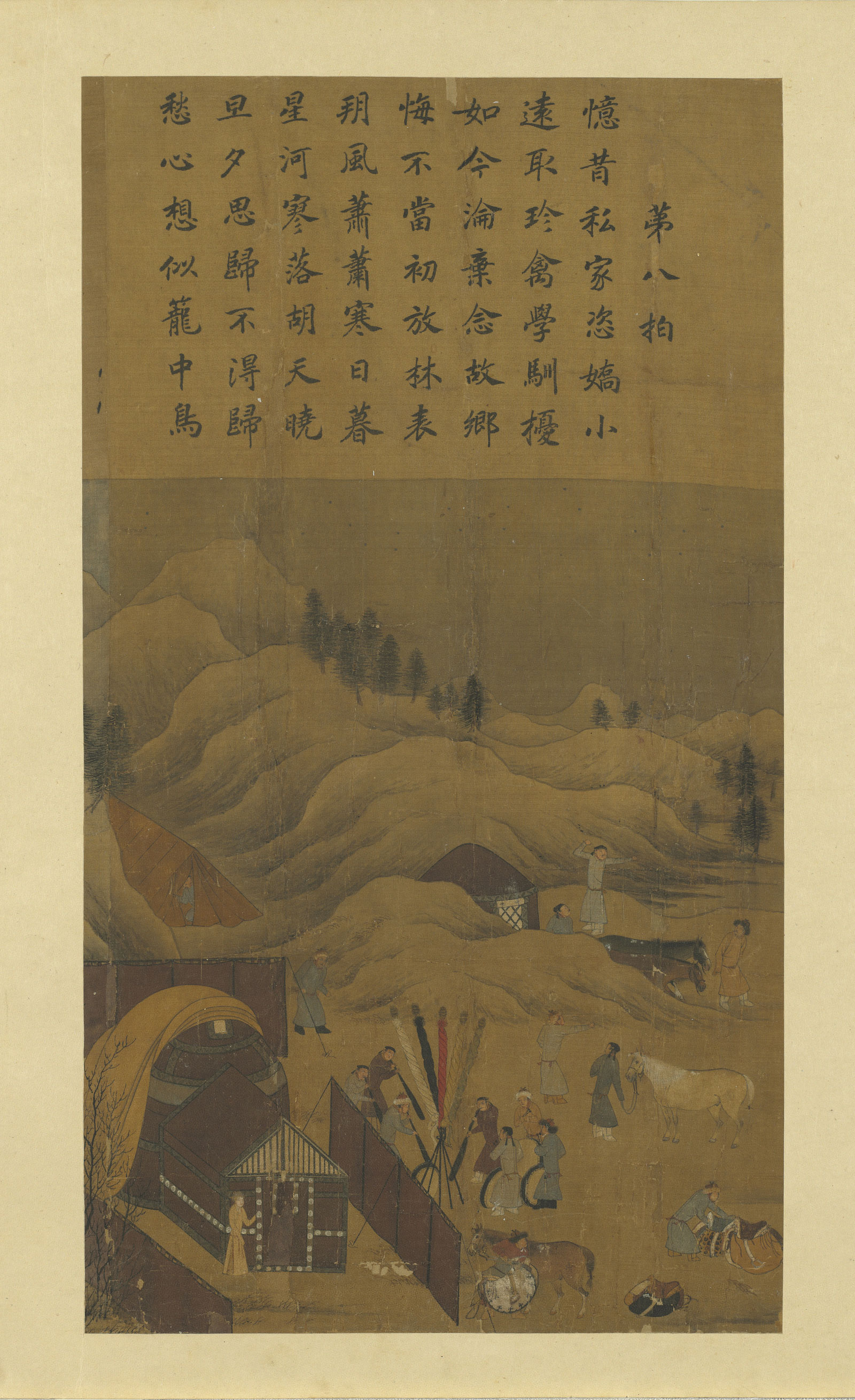

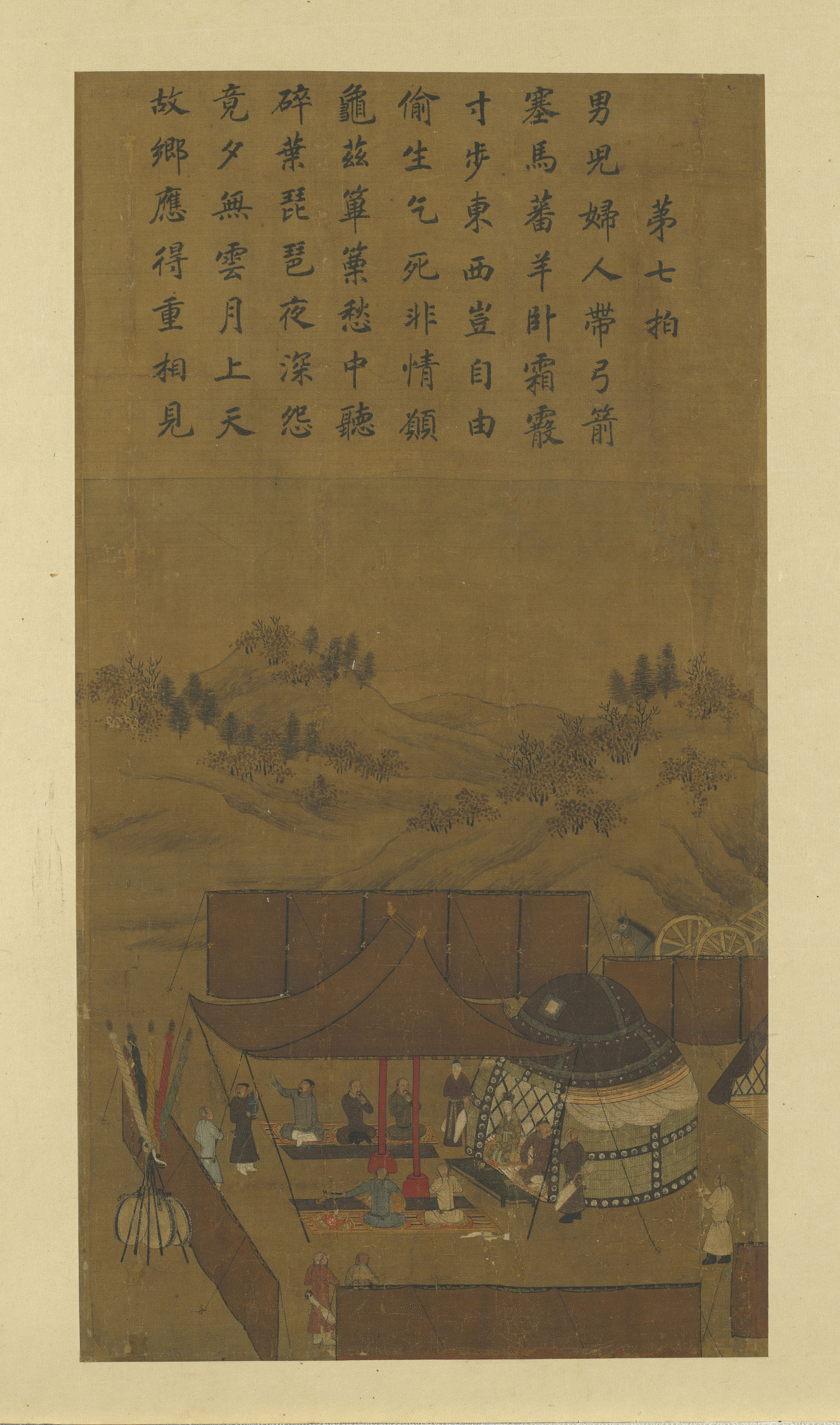

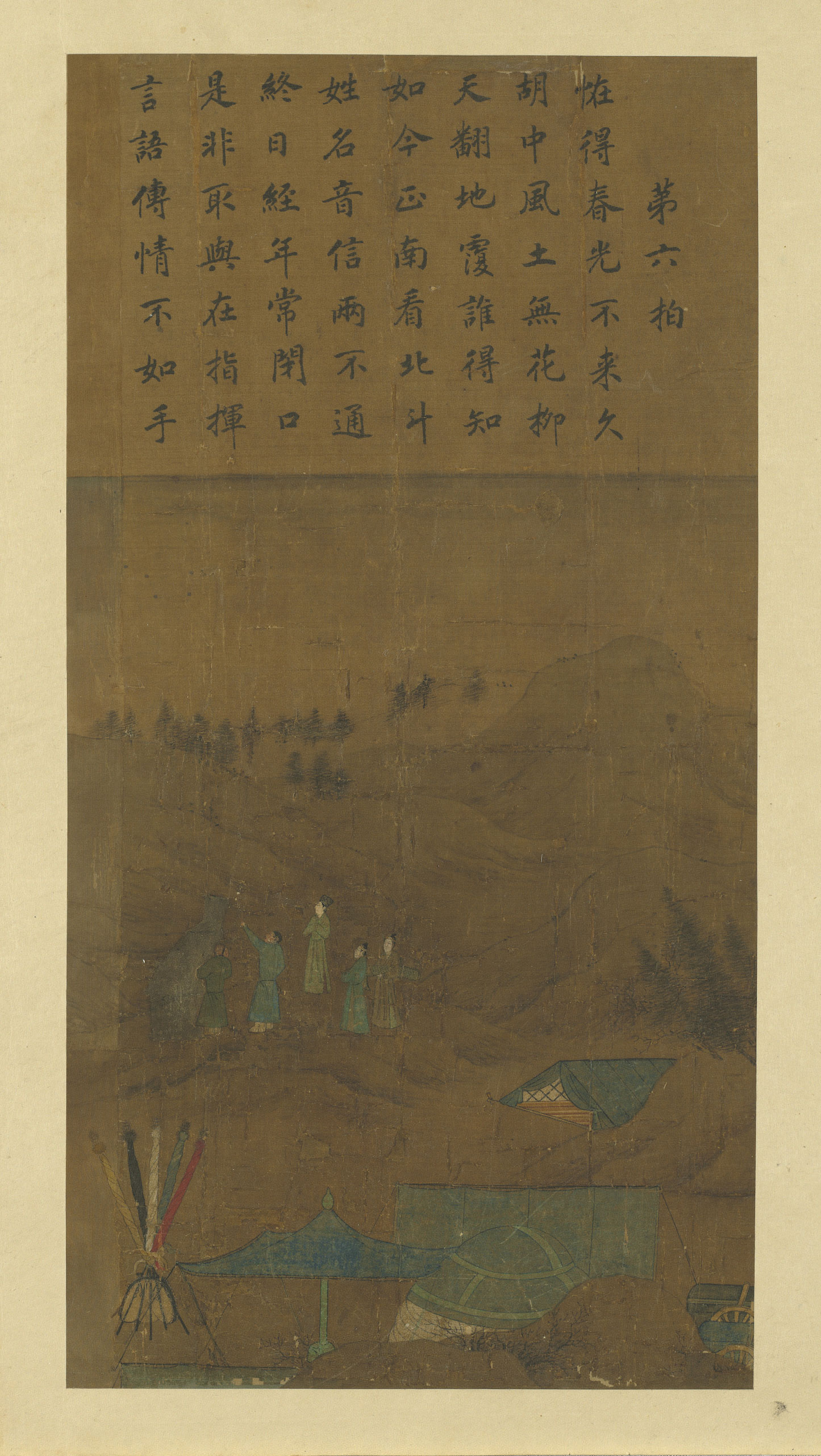

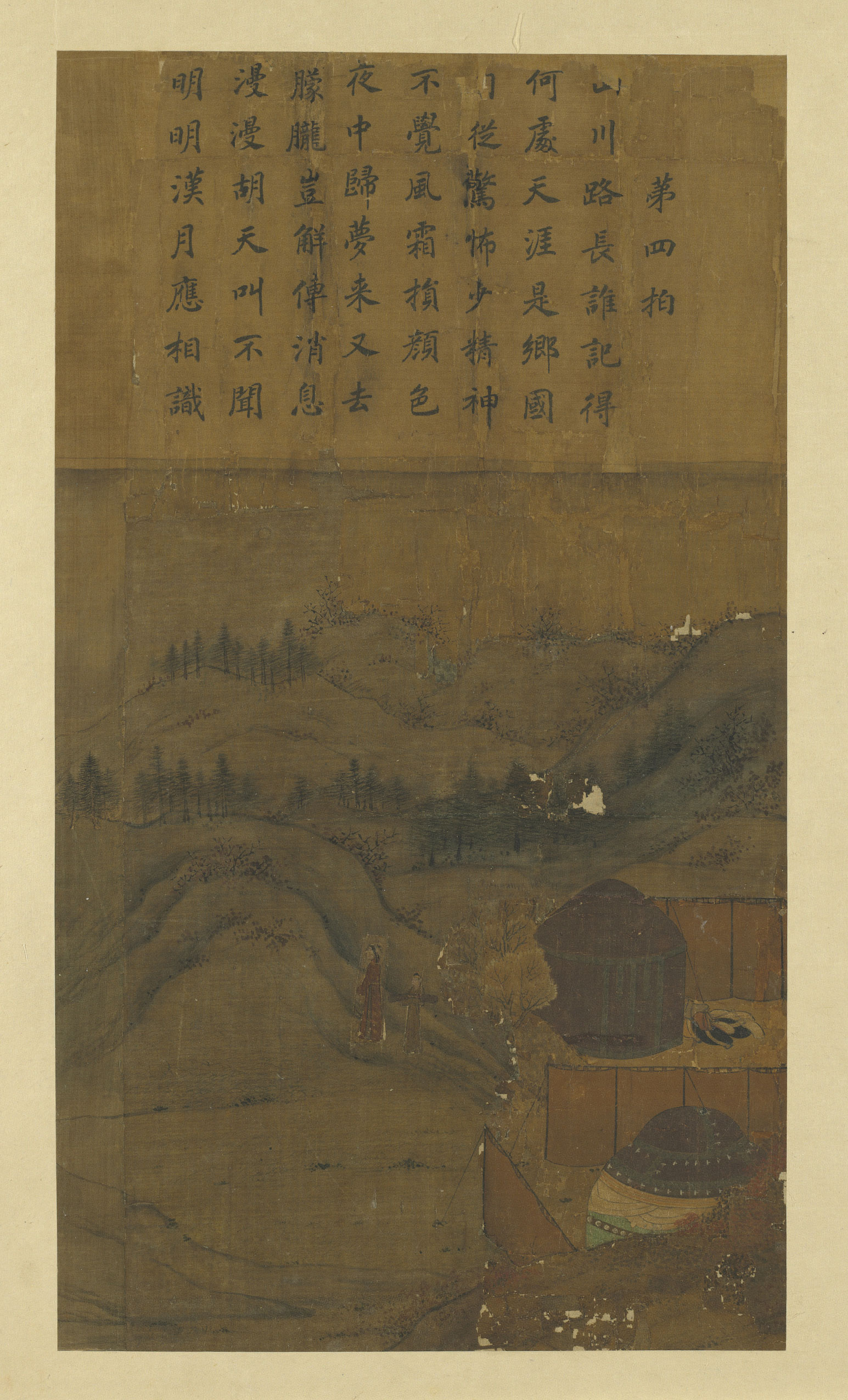

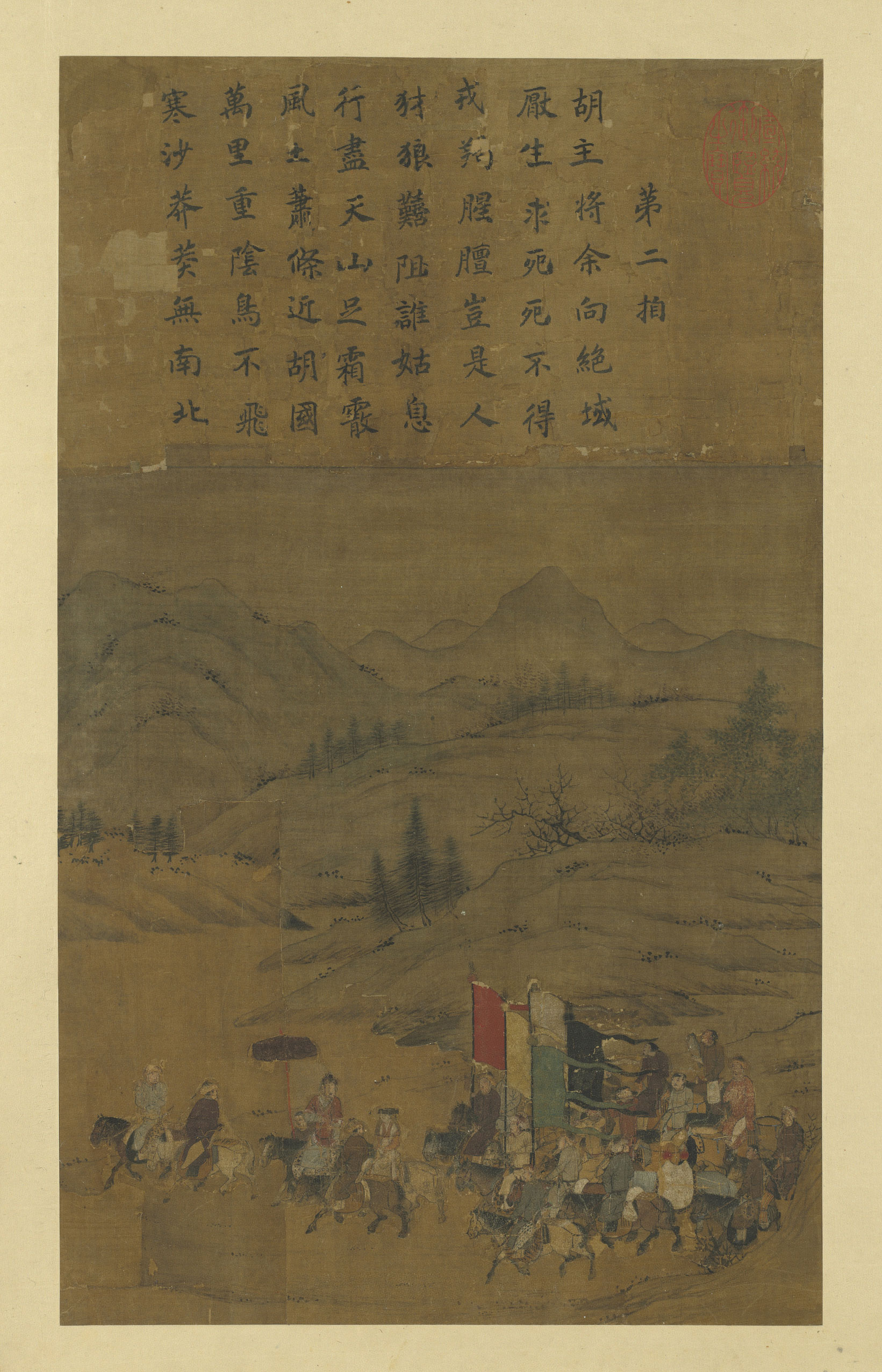

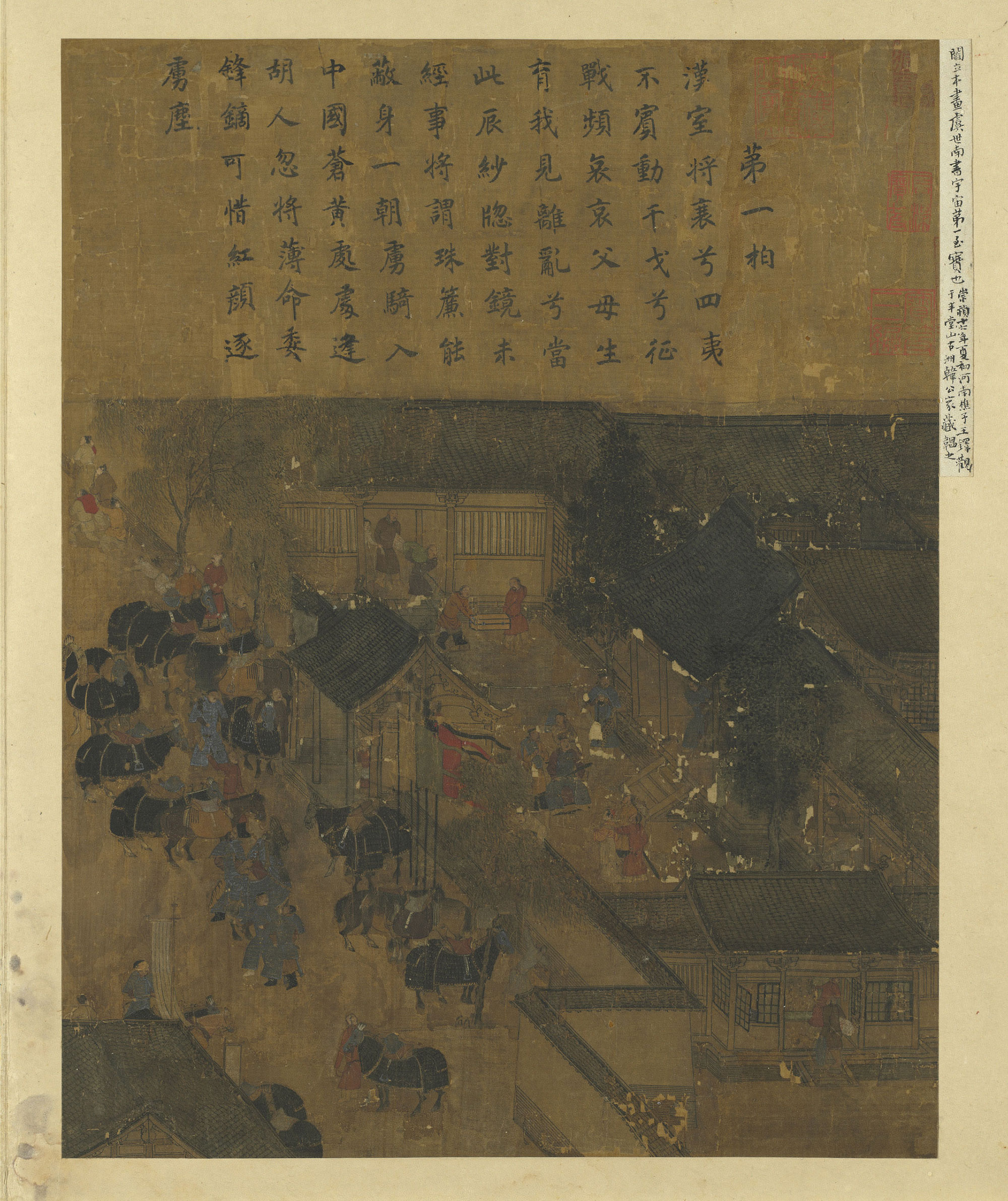

Lady Wenji's Return to China

- Li Tang (ca. 1049-after 1130), Song dynasty

This album presents the harrowing and poignant story of Cai Yan (style name Wenji, 162-229), a lady of considerable literary talent in the Eastern Han dynasty. She was captured by nomad raiders and held in captivity, where she and gave birth for a chieftain. These parts of her story, along with her eventual ransom and departure, form the background for this narrative album painting based on a historical event. Consisting of eighteen leaves, each work features a scene from the story and includes figures, chariots and horses, and background elements all rendered with exceptional detail. Each also includes a transcription from Lady Wenji's "Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute" for a combination of text and image.

The artist of this album was originally attributed as Li Tang, but the actual date of production appears to be slightly later. Although the paintings have been heavily retouched, they generally retain the refined beauty of the Painting Academy style from the Southern Song (1127-1279) court.

Peach Blossoms and a Lady

- Liu Songnian (fl. 1174-1224), Song dynasty

This painting features a large garden rock and a railing as a peach tree extends diagonally to the left. The branch tips adorned with peach blossoms and buds have an atmosphere of spring as if in a poem. A lady of youthful vigor stands below the outstretched tree and holds up a round fan to lean slightly forward, perhaps indicating the presence of butterflies.

The artist here apparently has referred to the following two lines in "Fiery Peach" from the ancient "Odes of Zhou" in The Book of Poetry: "The peach tree ablaze in red, how brilliant are its blossoms!" The poetry uses a flourish of peach blossoms in springtime to symbolize the vibrant but passing physical beauty of a young woman. Perhaps to emphasize this, the artist here skillfully used the lady's pose to expose the delicate skin of her lower arms. Although traditionally given to the Southern Song court artist Liu Songnian, this work reveals stylistic elements of Ming dynasty (1368-1644) painting instead.

Listening to a Ruan Lute

- Li Song (fl. 1190-1264), Song dynasty

This painting depicts a courtyard shaded by a tree and adorned with flowers. A scholar holds a fly whisk and sits on a daybed to cool himself as he listens to a lady playing music on a ruan, a kind of lute. To the side is another lady holding a flower as two maidens grasp a fan and burn incense. Various antiquities and curios have been placed on the daybed and nearby table, this scene of elegant leisure providing a glimpse at the idealized life of a scholarly gentleman in ancient times with women around him.

The traditional title gives Li Song of the Southern Song court as the artist, but the forms of the figures and use of brush and ink are closer to those of the Ming artist Du Jin (fl. 1465-1505), thus indicating a date of production closer to the middle Ming dynasty.

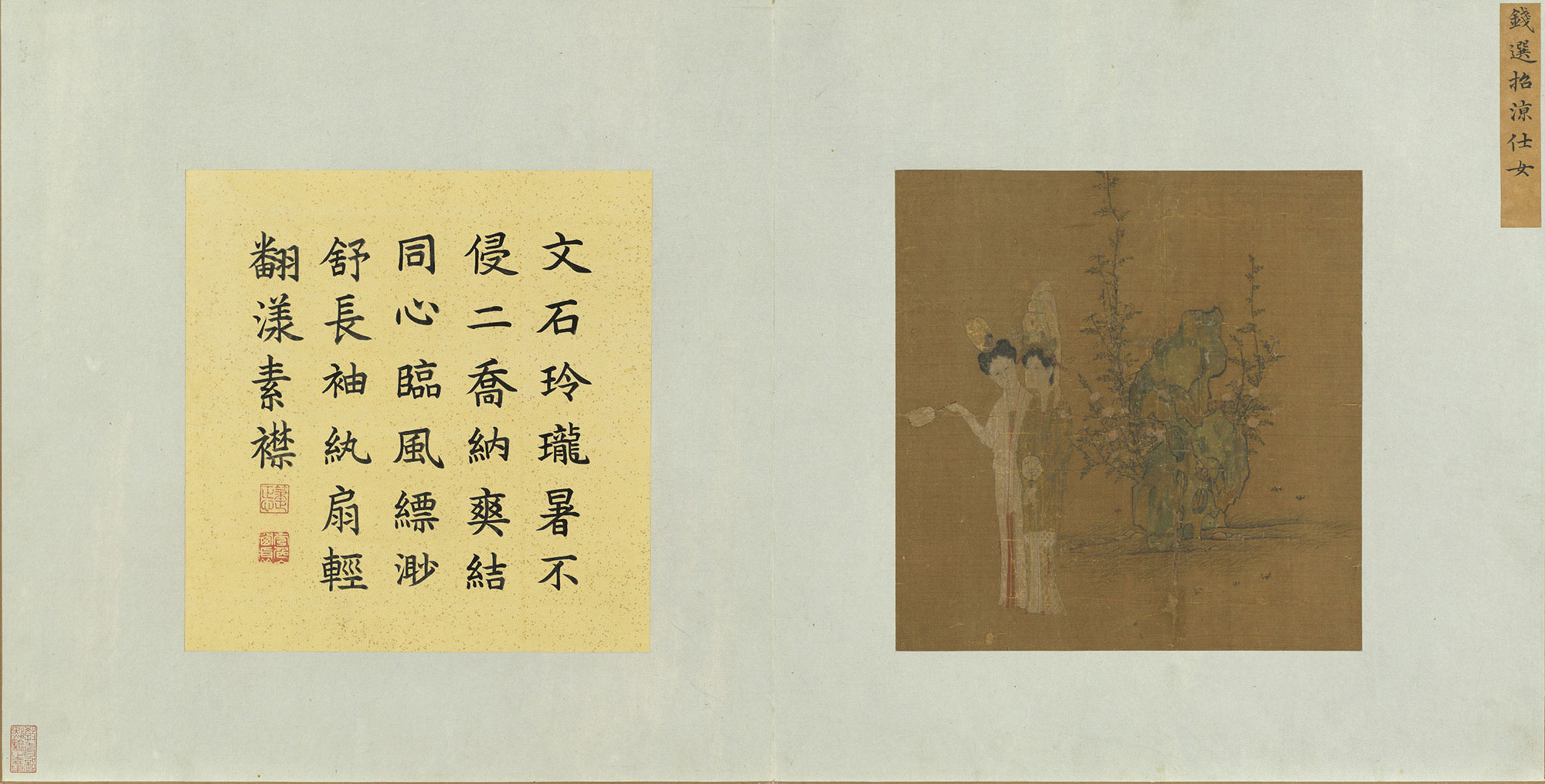

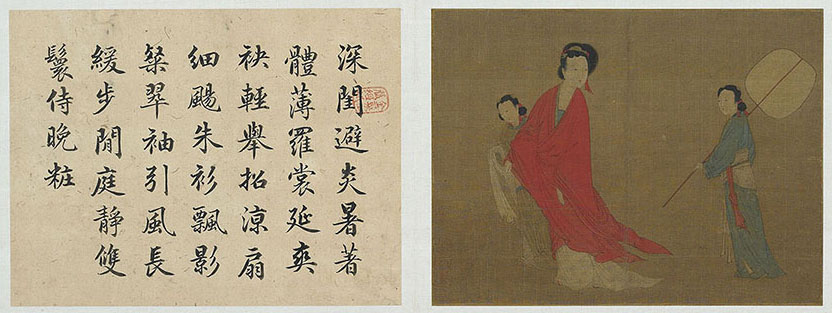

Ladies Cooling Off

- Qian Xuan (ca. 1235-after 1303), Song dynasty

Qian Xuan (style name Shunju), a native of Wuxing in Zhejiang, did not pursue the career of an official after the fall of the Song dynasty and instead devoted himself to poetry and painting, especially copying ancient works. He became known as one of the "Eight Talents of Wuxing."

From the album "Collected Famous Paintings of Antiquity," this work depicts two beauties with their hair tied up and adorned with silk-gauze crowns. One of them is wearing a green blouse and the other white robes. Holding round fans, they are shown taking an elegant stroll in a courtyard to avoid the heat. Behind them are flowers and a garden rock, the setting succinctly arranged and elegantly colored. The strokes for the drapery lines are rendered with fine yet strong brushwork similar to taut strands of silk. Most likely from the hand of a famous master, this work unfortunately bears no seal or signature of the artist. In the upper right, however, is a traditional title label giving the painter as Qian Xuan.

Bust Portraits of Huizong's Empress and Qinzong's Empress

- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

Neither of these portraits has the artist's signature. The right one represents Huizong's empress and the left one Qinzong's empress, the last two of the Northern Song (960-1127). Both empresses are wearing tall, elaborate and highly decorative head crowns with hair pins. On either side at the back are two "wings" individually decorated with dragons. The makeup on their faces is elegant and restrained, and the forehead, temple, and cheeks are adorned with pearls. The ladies are shown wearing red-bordered blue robes embroidered with golden dragons and pheasants, the depiction exceptionally refined and opulent.

Both empresses shown here were captured by northern Jin forces when the capital was sacked in the "Jingkang Incident" (1127) and met a tragic end when they died in the north. Despite the beauty of the clothing and accessories in these portraits, one can almost sense a touch of anxiety in their expression that perhaps reflects the uncertainty and political chaos of their times.

Seated Portrait of Gaozong's Empress

- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

Emperor Gaozong (1107-1187) over the course of his reign had two empresses. His first wife, Lady Xing, was captured in the "Jingkang Incident" of 1127 and taken north while he was away from the capital. After he assumed the throne following the invasion and set up a court in the south, he had her elevated to the rank of empress. In 1142, the coffin of Empress Xing was transported back south after her death, and Lady Wu formally became his new empress. Empress Wu was an avid reader and cultivated in the art of calligraphy, even serving for a time as Gaozong's ghost writer; he was particularly fond of her.

This portrait represents the latter of these two ladies, Empress Wu (1115-1197). She wears a crown with hair pins and decorated with nine dragons, the pearl decor applied to her face quite delicate. She wears a dark blue robe embroidered with twelve pairs of pheasants. The borders of the robe are lined with red and decorated with dragons, the design exceptionally beautiful.

Taking in the Coolness of a Palace Pond

- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

This work depicts a lotus pond surrounded by a white stone railing as a palace lady appreciates lotuses and enjoys the coolness there. She sits leisurely and rests against a table on the daybed, her gaze steady as if deep in thought. A male attendant holds a large long-handled fan adorned with phoenixes, which indicate the lady is of lofty status with the rank of a consort. On the table to her left is placed an abundance of drinks and snacks to cool off, and on the table behind her is a round fan with a shadowy image on it. It suggests that a chill has come over the palace, indicating that she also is like a fan no longer needed in autumn.

Although the traditional title indicates the painting was done by an anonymous Song artist, the style of furniture is later and closer to that of the Ming dynasty.

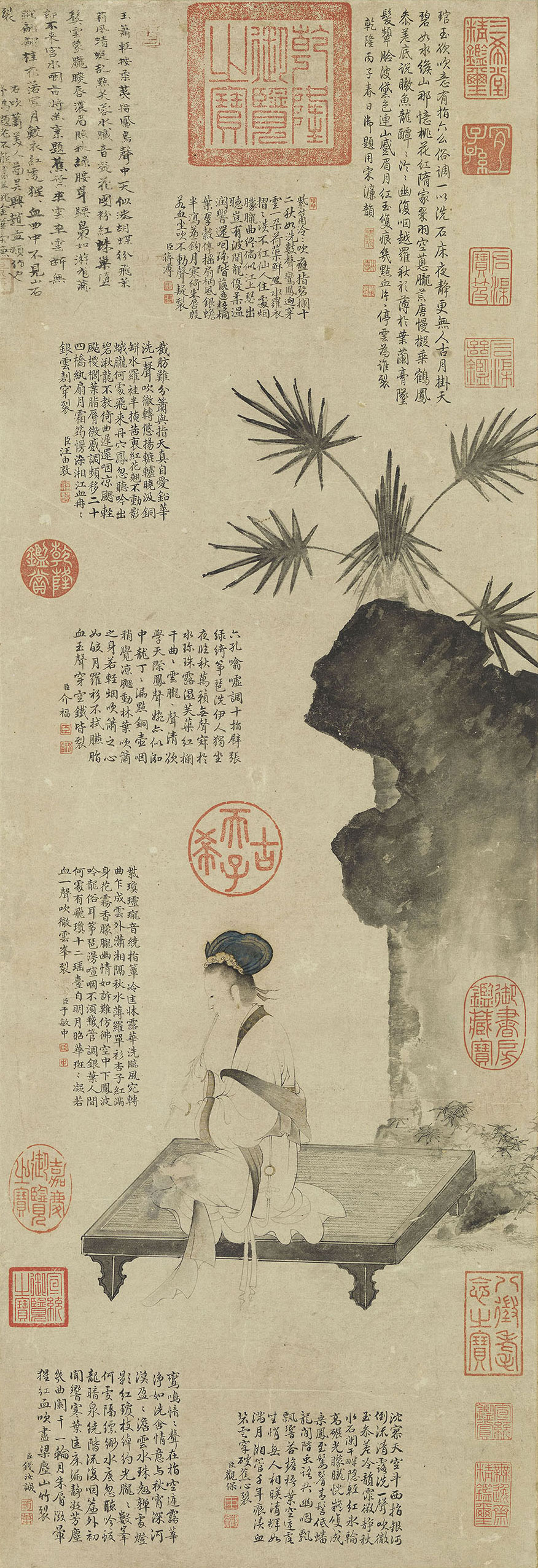

Lady Playing the Flute

- Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322), Yuan dynasty

Zhao Mengfu, a native of Wuxing in Zhejiang, went by the style name Zi'ang and had the sobriquet Songxue daoren.

In this painting is a lady sitting cross-legged on a daybed next to a garden rock in front of a coir palm tree. An inscription by Song Lian (1310-1381) in the upper left corner gives Zhao Mengfu as the painter. The rock is rendered in stained washes of ink that contrast with the delicately outlined features of the lady, who is shown with a sense of refinement and elegance compared to the archaic and simple background. The lady's expression and steadiness of her seated pose successfully capture the atmosphere of her full attention devoted to playing music.

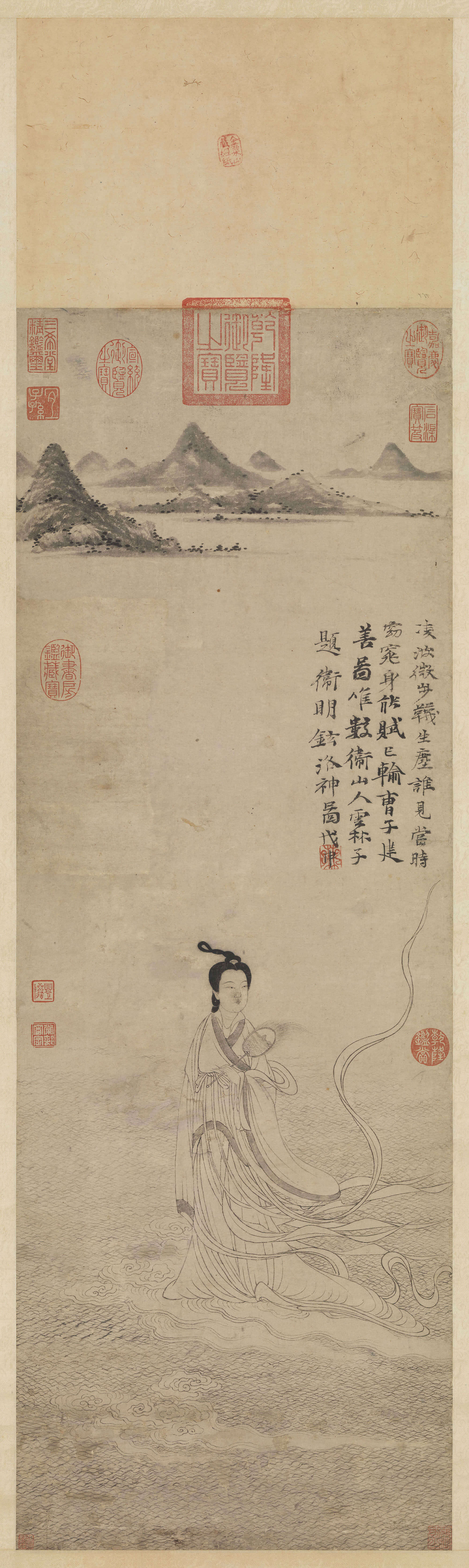

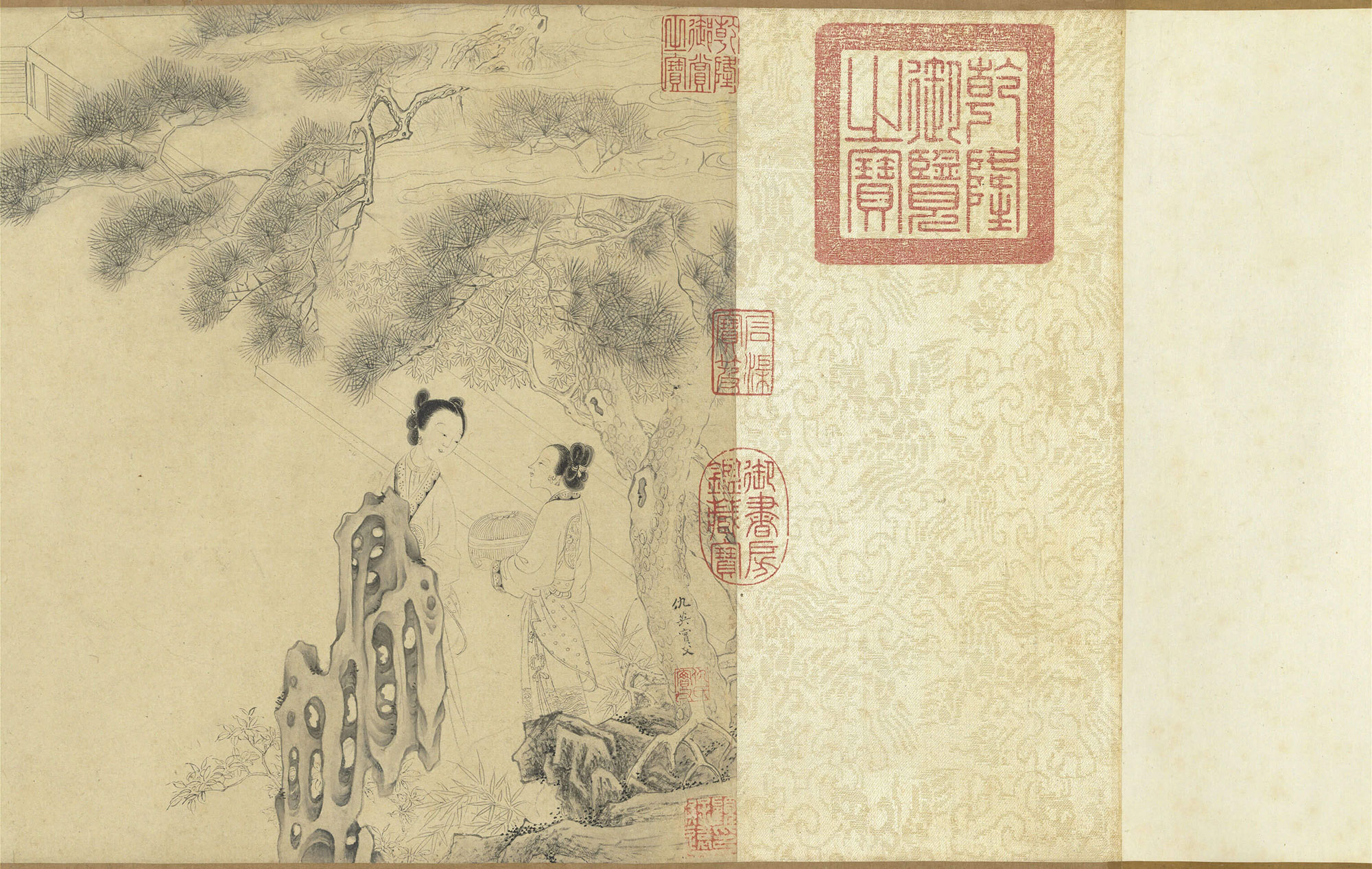

Nymph of the Luo River

- Wei Jiuding (14th c.), Yuan dynasty

Wei Jiuding, style name Mingxuan, was from Tiantai in Zhejiang.

This renowned painting is Wei Jiuding's only surviving depiction of a lady. Consort Mi, the Nymph of the Luo River, is rendered here in "baimiao" ink lines floating on a cloud as she glides gracefully over the surface of the water in scene of lofty antiquity. Pliant ribbons flutter in the breeze like coiled dragons in the air as one gently ascends upwards, fully expressing an aesthetic of ethereal other-worldliness. In the middle of the composition is a large blank space; to the left is an area of paper that had been replaced in the past and to the right an inscription by the famous contemporary painter Ni Zan. In the distance are rounded peaks in the "sketching ideas" manner using light ink that were perhaps added by another person.

Bust Portraits of Yuan Shizu's Empress and Yuan Shunzong's Empress

- Anonymous, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

The artist for either of these unsigned paintings has yet to be identified. The right work is a portrait of Empress Chabi (?-1281), the wife of Emperor Shizu (the Mongol ruler Kublai Khan [1215-1294]), while the left one depicts Empress Tagi, the wife of Emperor Shunzong (Darmabala [1264-1292]). Both empresses wear a type of Mongolian crown known as a kükül and have horizontal eyebrows, which are the most notable features of Yuan dynasty makeup and accessories among Mongol imperial ladies at the time.

This type of bust portrait also served as a model for doing larger full-length formal portraits in the hanging scroll format. Yuan dynasty imperial portraits combine features of both traditional Chinese and foreign styles. The figures' faces are full and rounded with ruddy cheeks that particularly stand out. The border decoration of the clothing includes a kind of Islamic-style textile woven with gold strands known as nasij ("cloth of gold"), which is especially sumptuous and refined.

Lady Cooling Off

- Anonymous, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

In this painting is a beauty wearing vermilion clothes with her hair tied into a topknot; she turns her head back slowly as she takes a stroll. Near her are two maidservants with their hair also neatly tied into whorled chignons. One of them is holding a white cloth and the other a large long-handled round fan. The hierarchical difference in size between the lady and her attendants is clear, and the drapery outlines are refined yet strong, imparting an extremely archaic beauty to the work. No signature appears on the painting, but in the lower left corner are the impressions of two seals with the name of the famous Yuan artist Zhao Mengfu. Although the title suggests a lady cooling off, the clothing of and objects held by the figures are similar to the subject of the Tang consort Yang Guifei having emerged from her bath. It is thus perhaps a painting copied after an older work by a Yuan dynasty artist.

Lady and Plum Blossoms

- Anonymous, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

A slender beauty stands beneath a plum tree in blossom. Holding a bronze mirror, she gazes at herself to adjust her makeup. To her side are a garden rock and narcissus flowers, the scenery likewise serene and elegant. Her forehead is adorned with floral decoration in the shape of a plum blossom, which forms the most eye-catching feature of the painting. The attire worn here, judging by a record from On the Beginning of Learning by Xu Jian (659-729) of the Tang dynasty, would indicate the figure here to be Princess Shouyang, the daughter of Emperor Wu (363-422) in the Song period of the Southern Dynasties era.

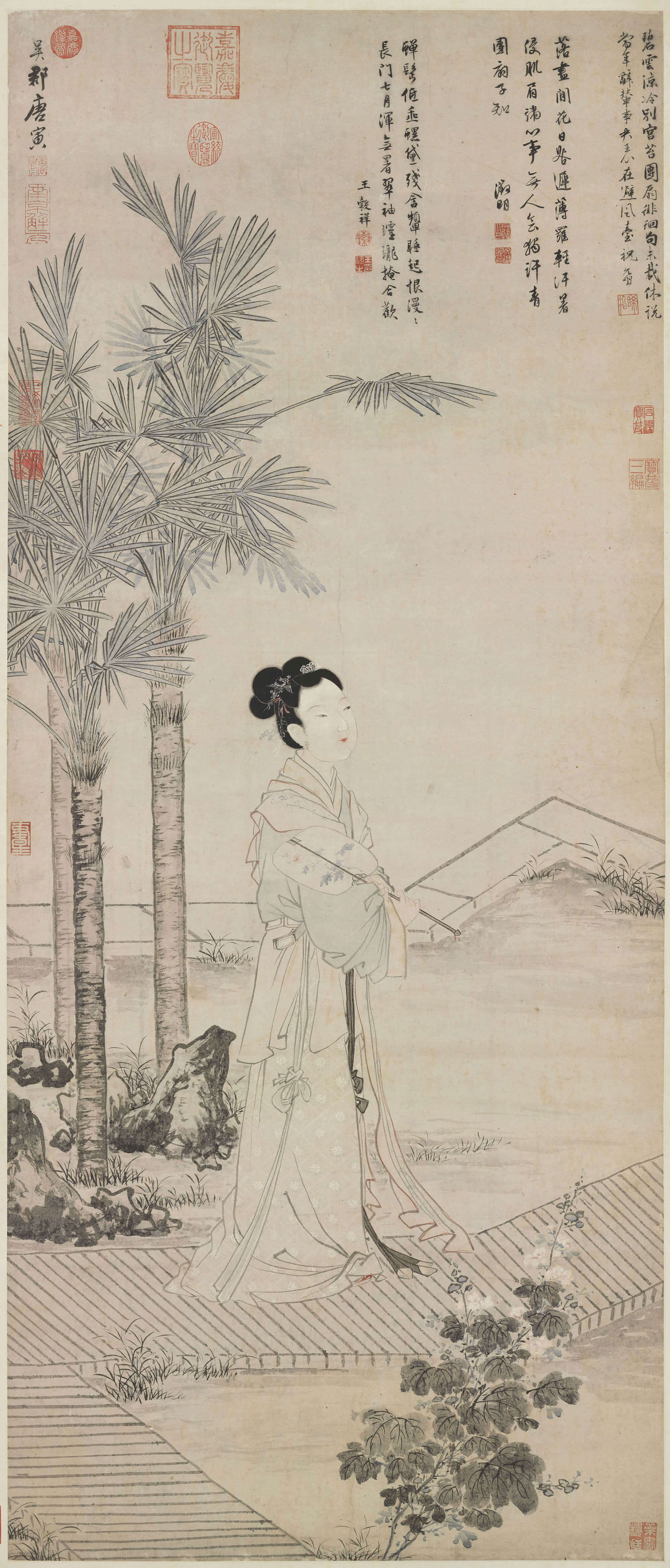

Lady in the Shade of Plantain

- Wen Zhengming (1470-1559), Ming dynasty

Wen Zhengming, a native of Changzhou (Suzhou) in Jiangsu, originally went by the name Bi and had the style name Zhengming with the sobriquets Tinghengsheng and Hengshan jushi.

Wen Zhengming was a conscientious scholar and rarely did paintings of ladies, this being the only one in the collection of the National Palace Museum. Both the composition and use of brush and ink are quite reserved as Wen sought neither complex detail nor overt opulence. Wen also did not consciously emphasize the beauty of the lady's face or the grace of her pose. Instead, he sought a kind of revivalist simplicity for a style completely different from that of lady paintings popular at the time. It is, in fact, in a style more of the literati.

Tao Gu Presenting a Verse

- Tang Yin (1470-1524), Ming dynasty

Tang Yin (style name Bohu) was a native of Wuxian (Suzhou, Jiangsu). He first learned painting from Zhou Chen and later studied widely from Song and Yuan dynasty works. His style combined both precise beauty and elegant strength to rank him among the Four Ming Masters.

This scroll depicts the story of Tao Gu (903-970), an official of the early Northern Song court sent as an emissary to its adversary, the Southern Tang. In order to scandalize him, the Southern Tang court sent the palace courtesan Qin Ruolan in the guise of a stationmaster's daughter along Tao's route to seduce him. With ungentlemanly intentions, Tao Gu fell for the trap and presented her with a verse, which was a serious breach of etiquette for a court official. Later, at a banquet held by the Southern Tang ruler Houzhu, Tao Gu assumed an arrogant air of upright loftiness. Houzhu then had Qin Ruolan join the party and sing, her lyrics being the verse that Tao had given to her. Exposed as a hypocrite, it led to Tao's downfall.

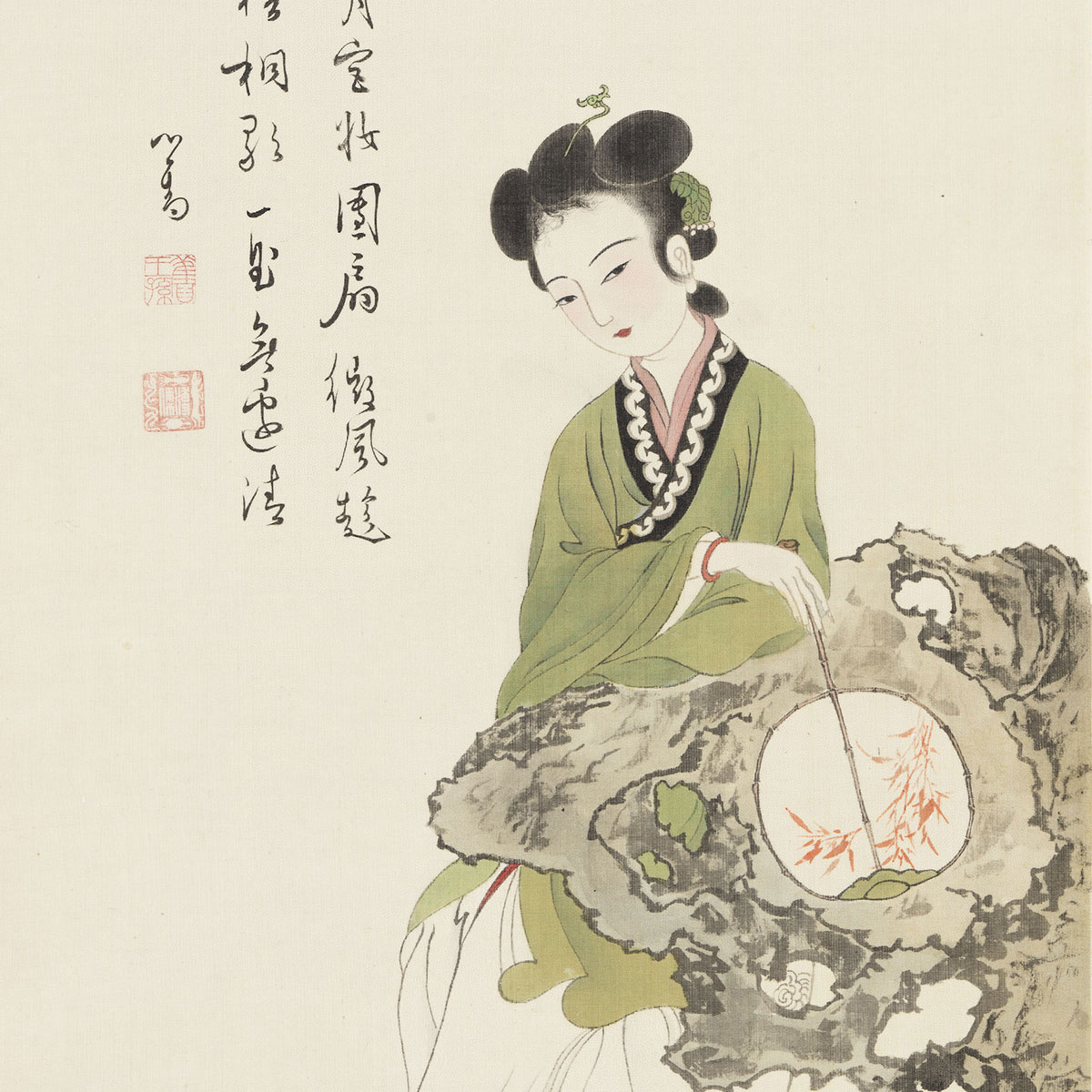

Lady Ban's Round Fan

- Tang Yin (1470-1524), Ming dynasty

Tang Yin (style name Bohu) was from Wuxian in Jiangsu and learned painting from Zhou Chen but soon surpassed him in skill to become one of the Four Ming Masters.

The subject of this painting comes from Ban Jieyu's (48-6 BCE) "Song of Reproach" in the Han dynasty. Tang Yin depicted Lady Ban holding a round silk fan and standing quietly alone beside coir palm trees as she gazes into the distance as if deep in thought. The hollyhock flowers in the foreground give the season as late summer with the approach of cool weather in autumn. The artist's skillful integration of the figure into the scenery creates a striking image of someone having fallen out of favor, discarded like a summer fan in autumn. The emotions evoked by the painting transport the viewer back in time to the vicissitudes of affection experienced by this Han dynasty beauty.

Imitating a Tang Artist's Lady Painting

- Tang Yin (1470-1524), Ming dynasty

According to a record in Discussions with a Friend at Yunxi, Cui Ya was famous for his literary skills in the Yangzhou area during the Tang dynasty. The famous courtesan Li Duanduan once asked Cui for a poem and received from him the following line: "A blossom of white peony able to walk." In this painting sits a man on a daybed gazing at a lady holding a white peony by the screen partition; it depicts the meeting between Li Duanduan and Cui Ya

Although this work is based on the matters of prominent figures in the Tang dynasty, it actually also reflected the situation of the middle to late Ming dynasty for Tang Yin as well as the cultural phenomenon of scholars and courtesans enjoying frequent interactions at the time.

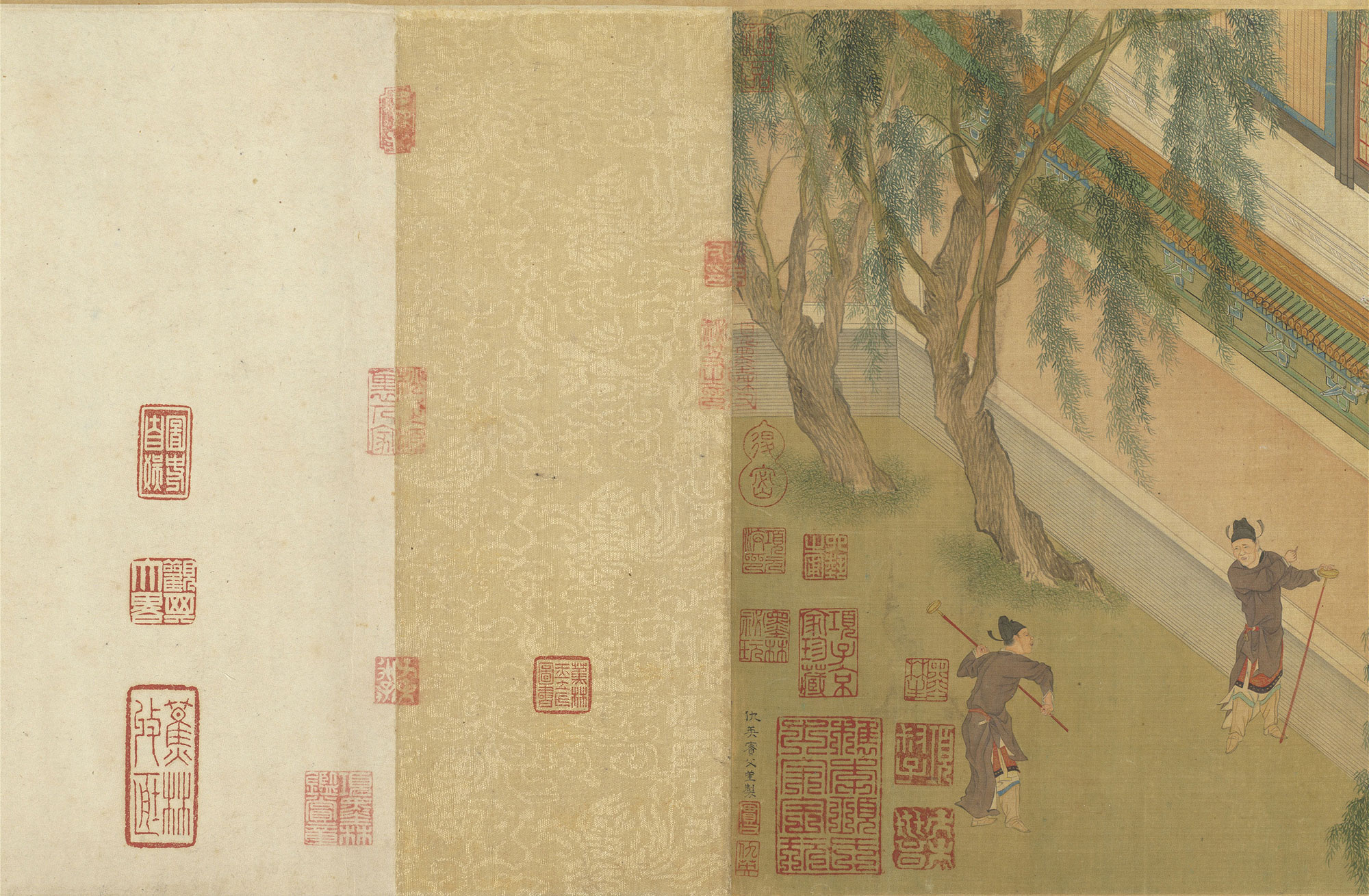

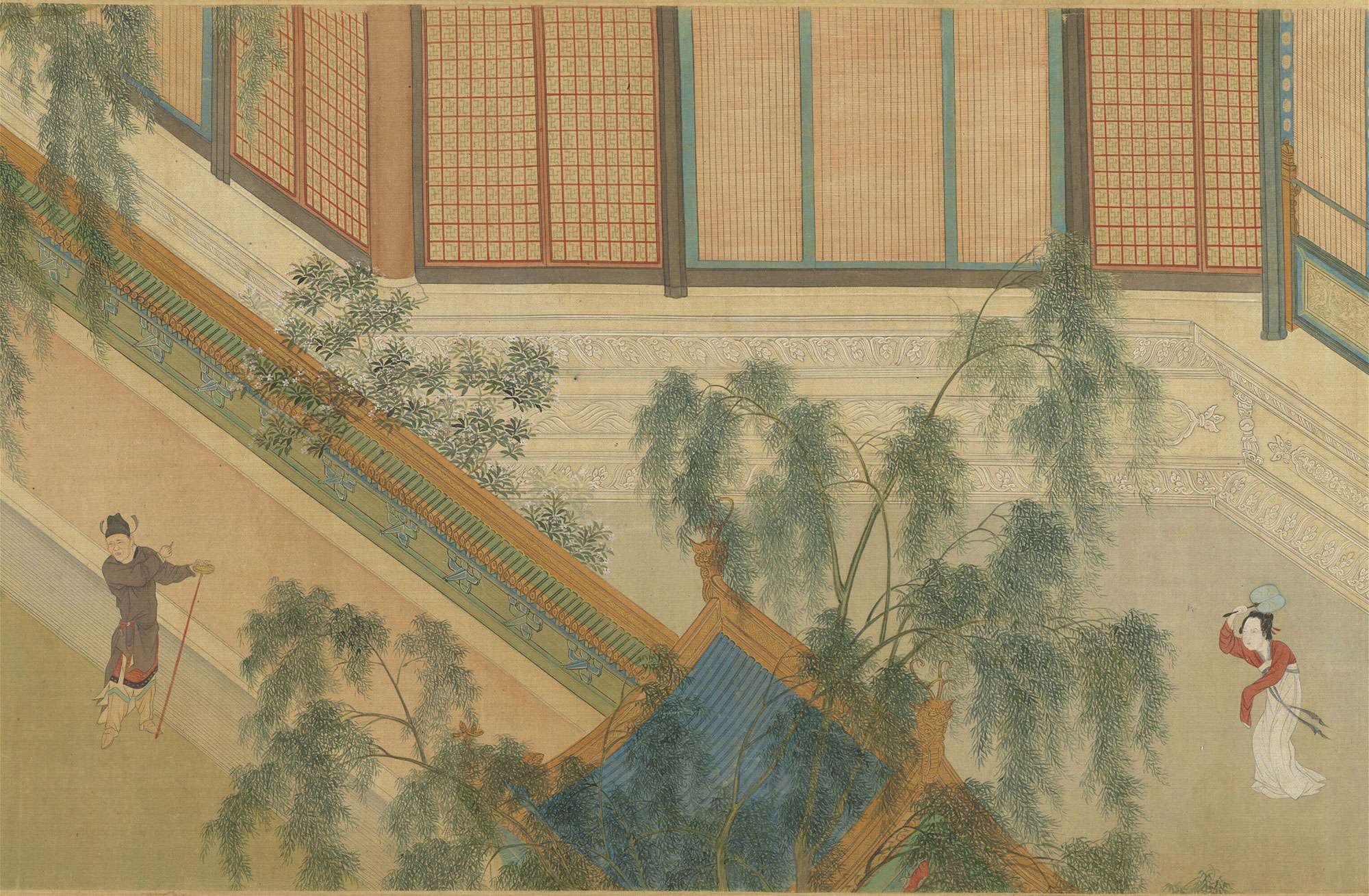

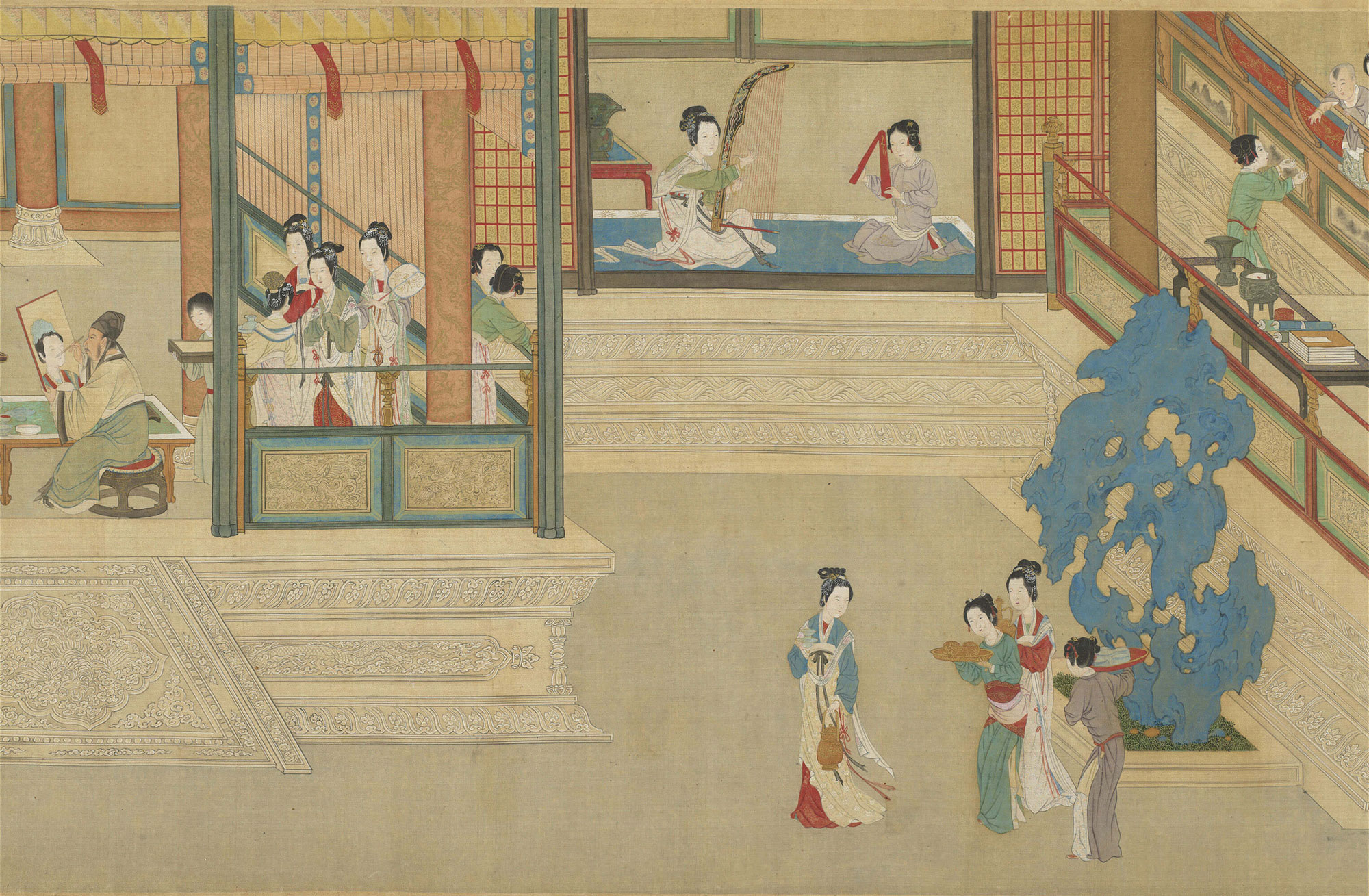

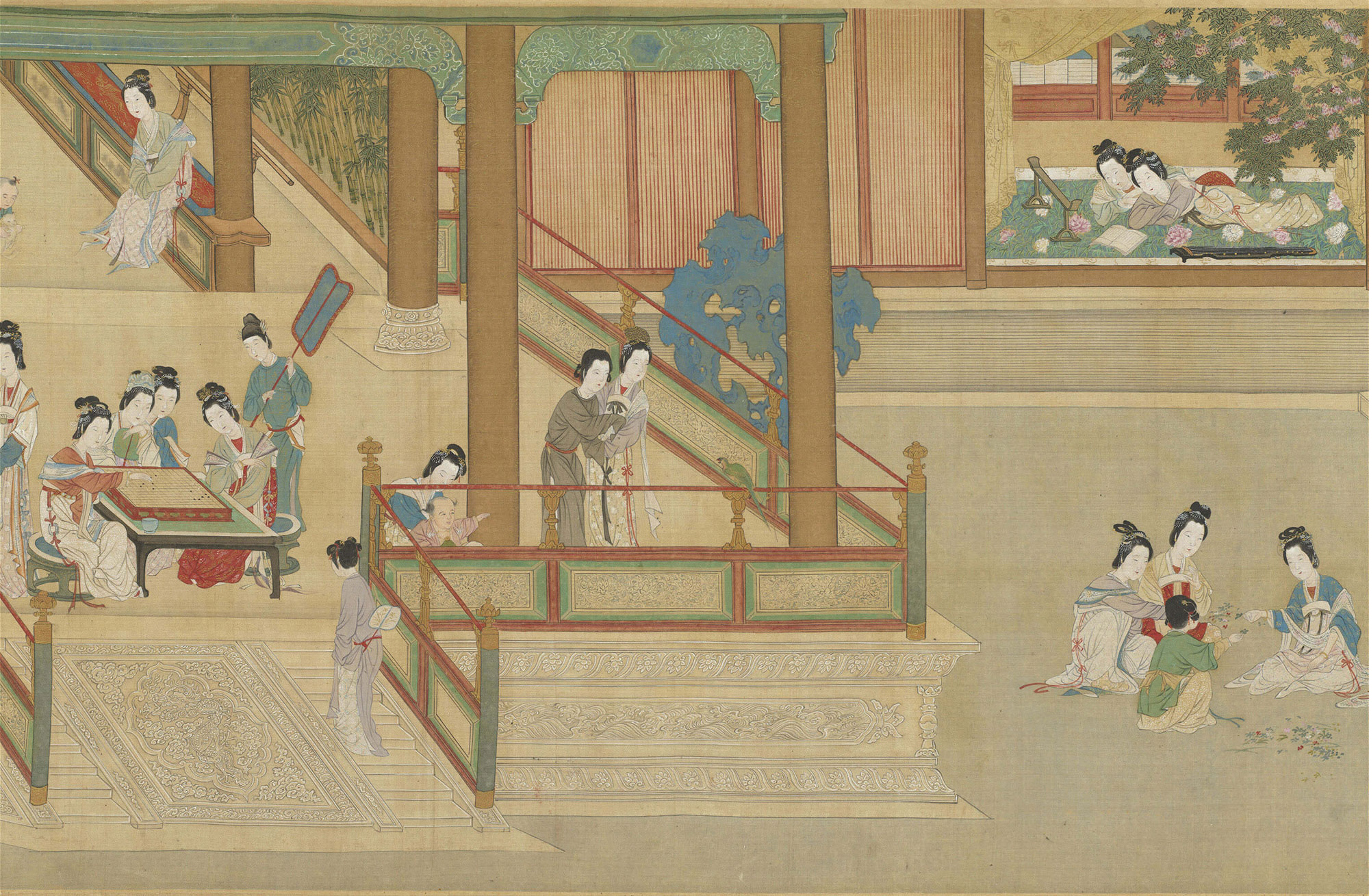

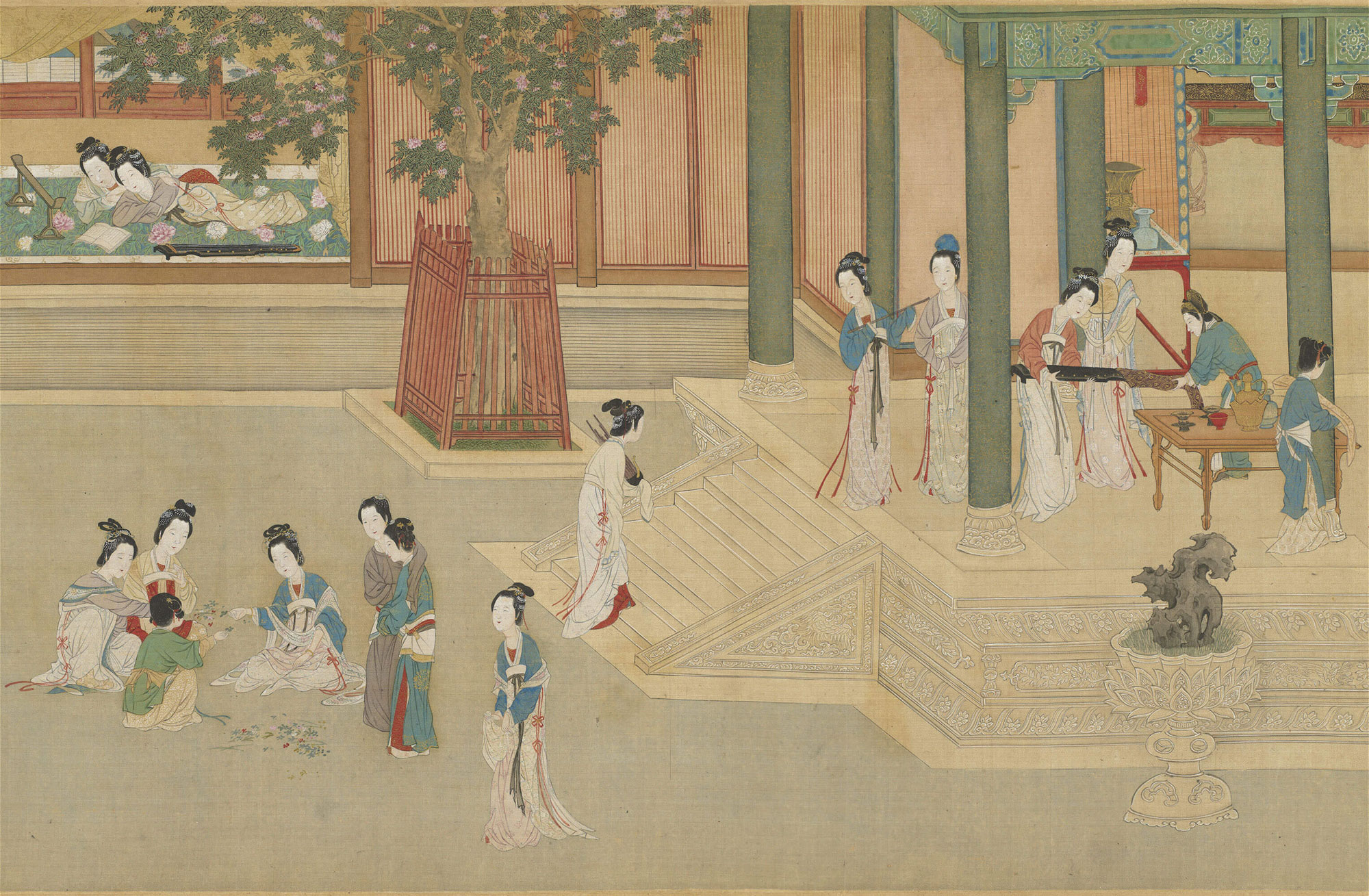

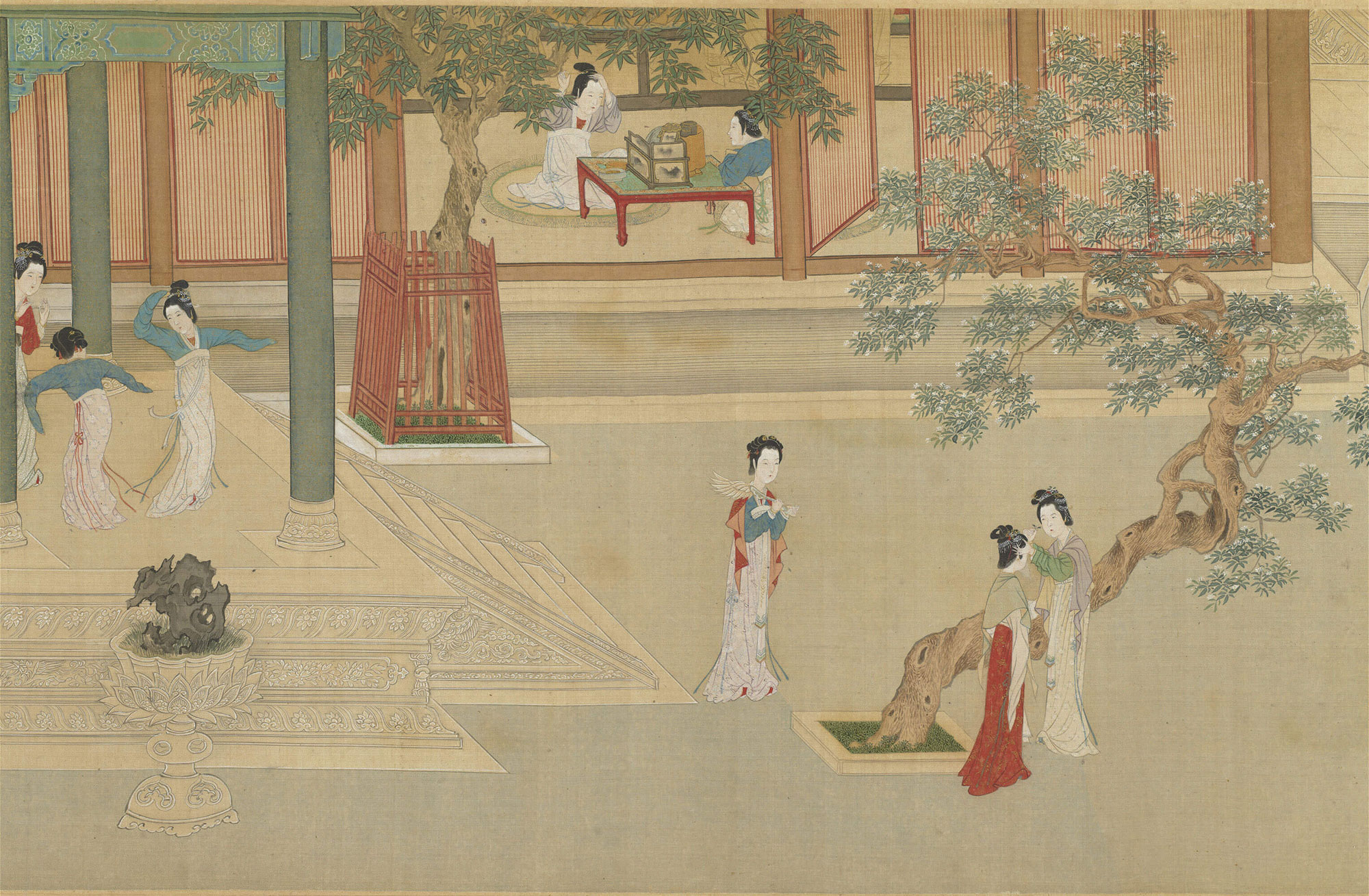

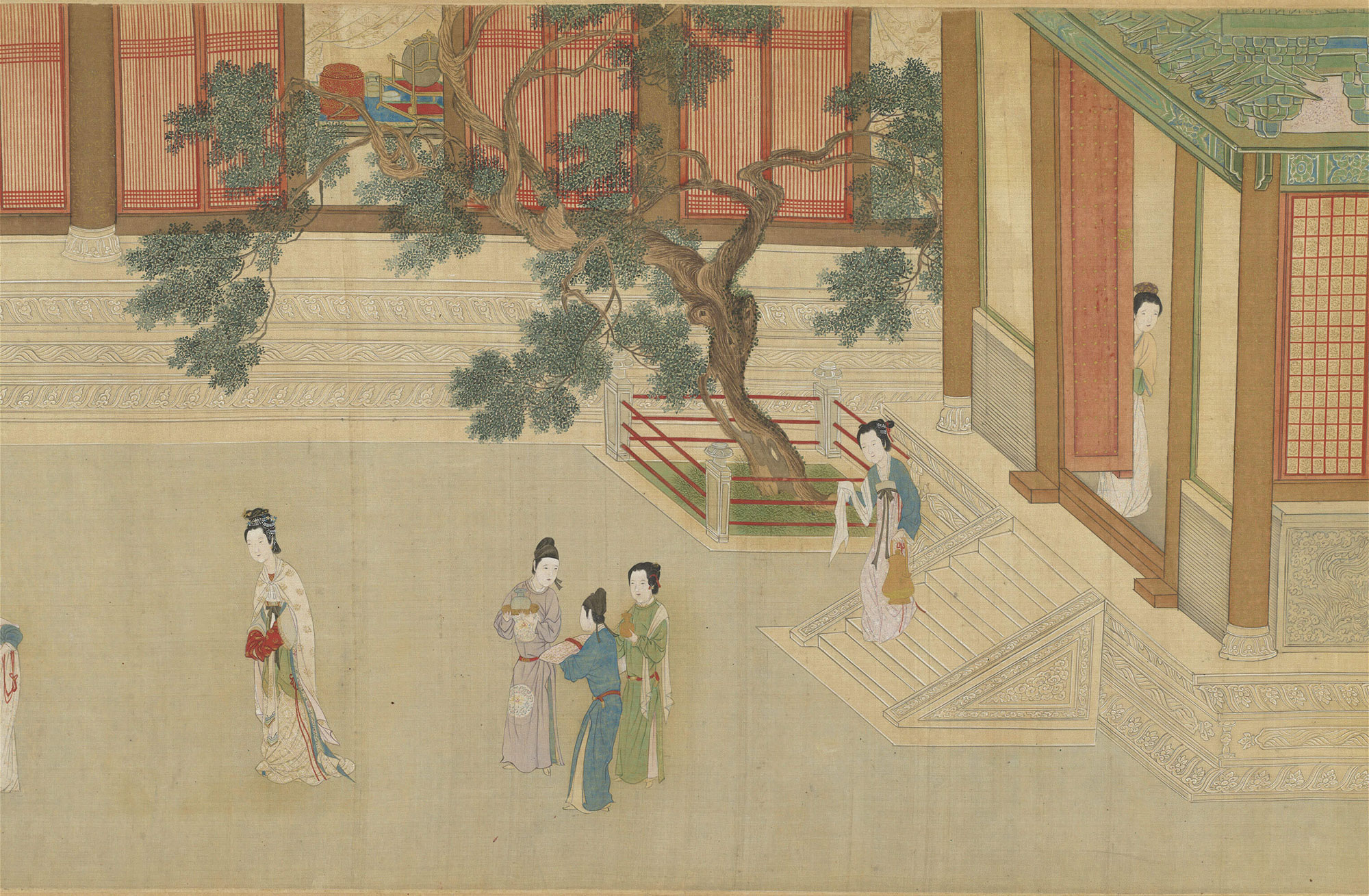

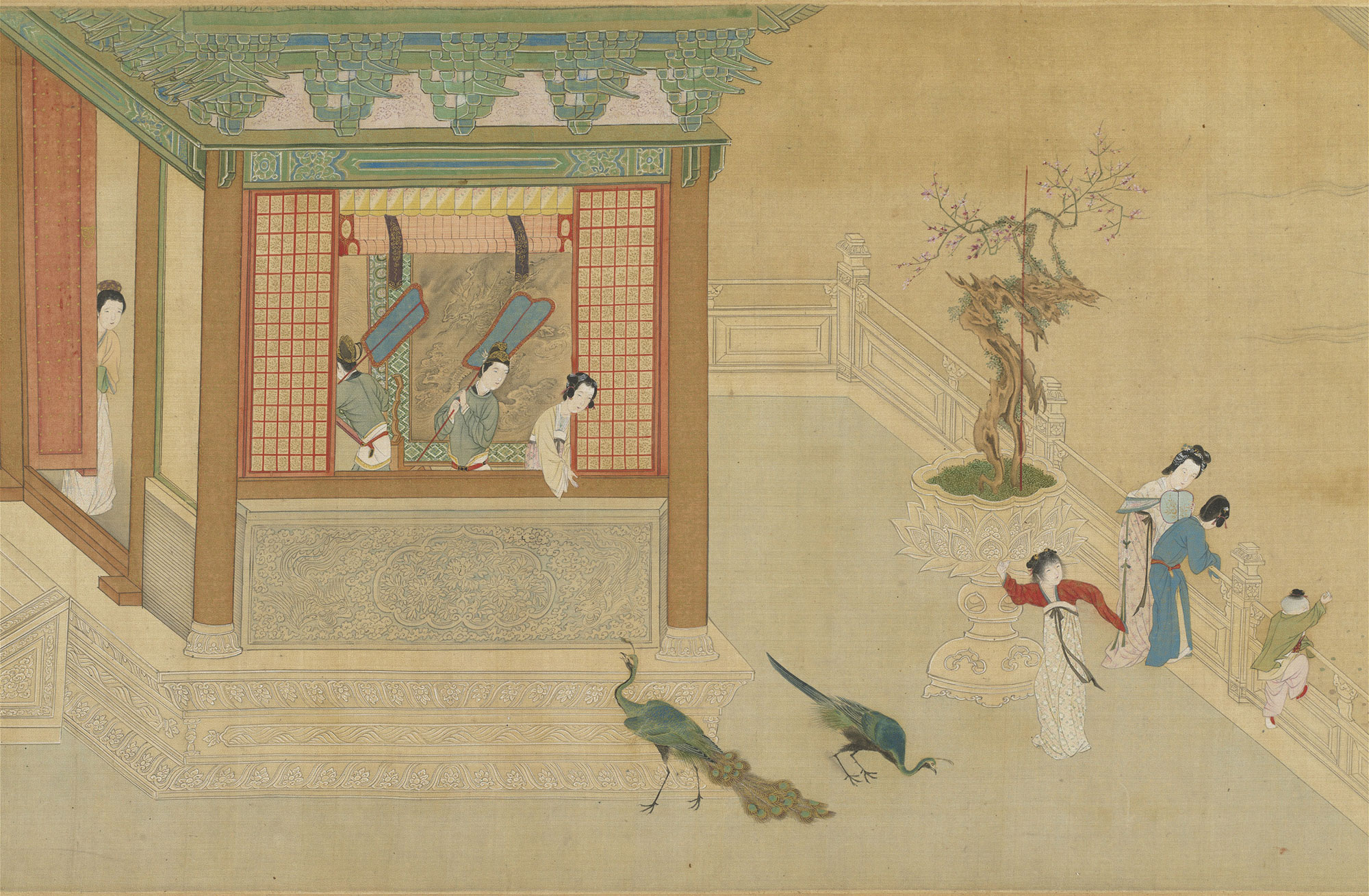

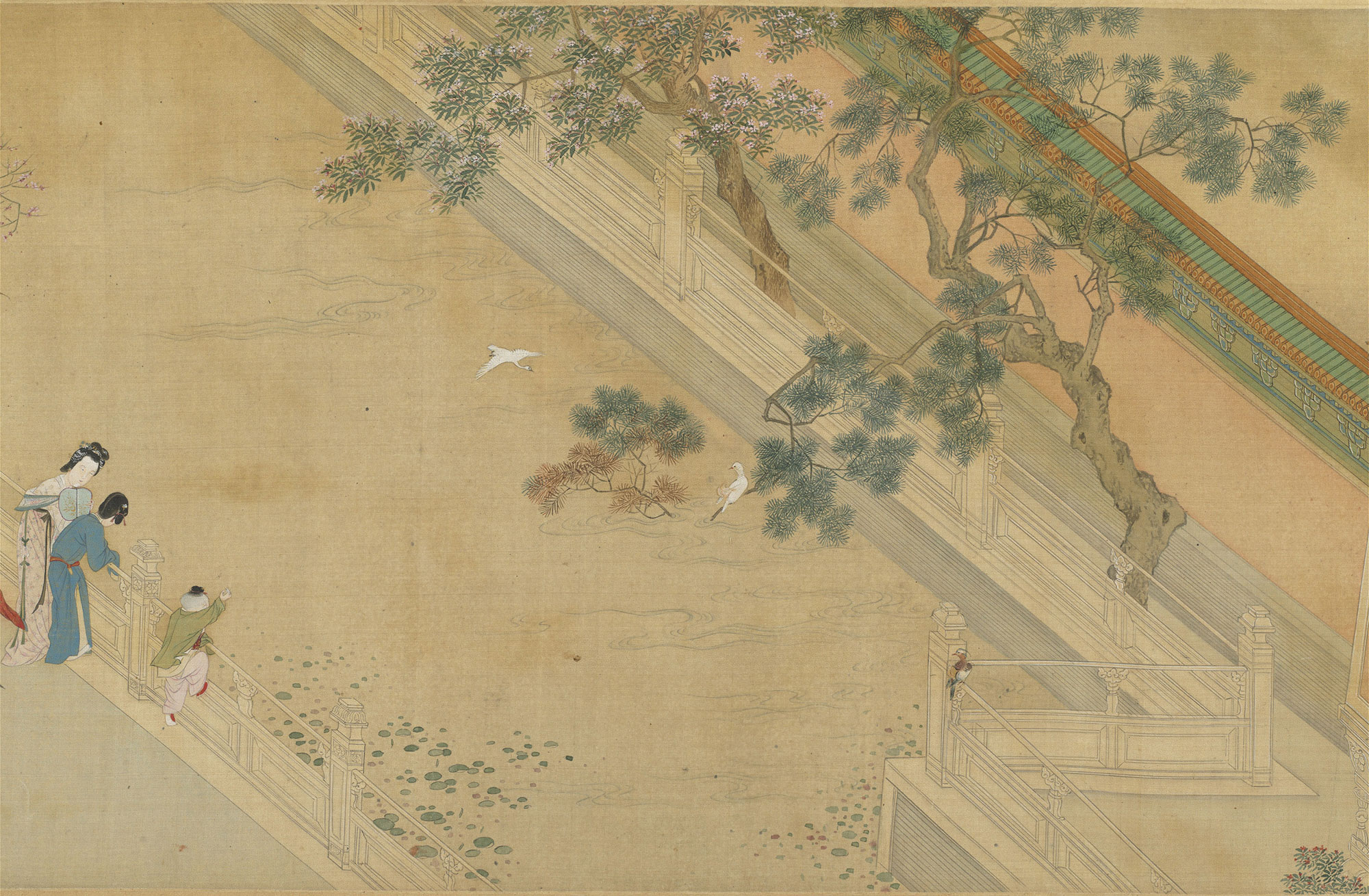

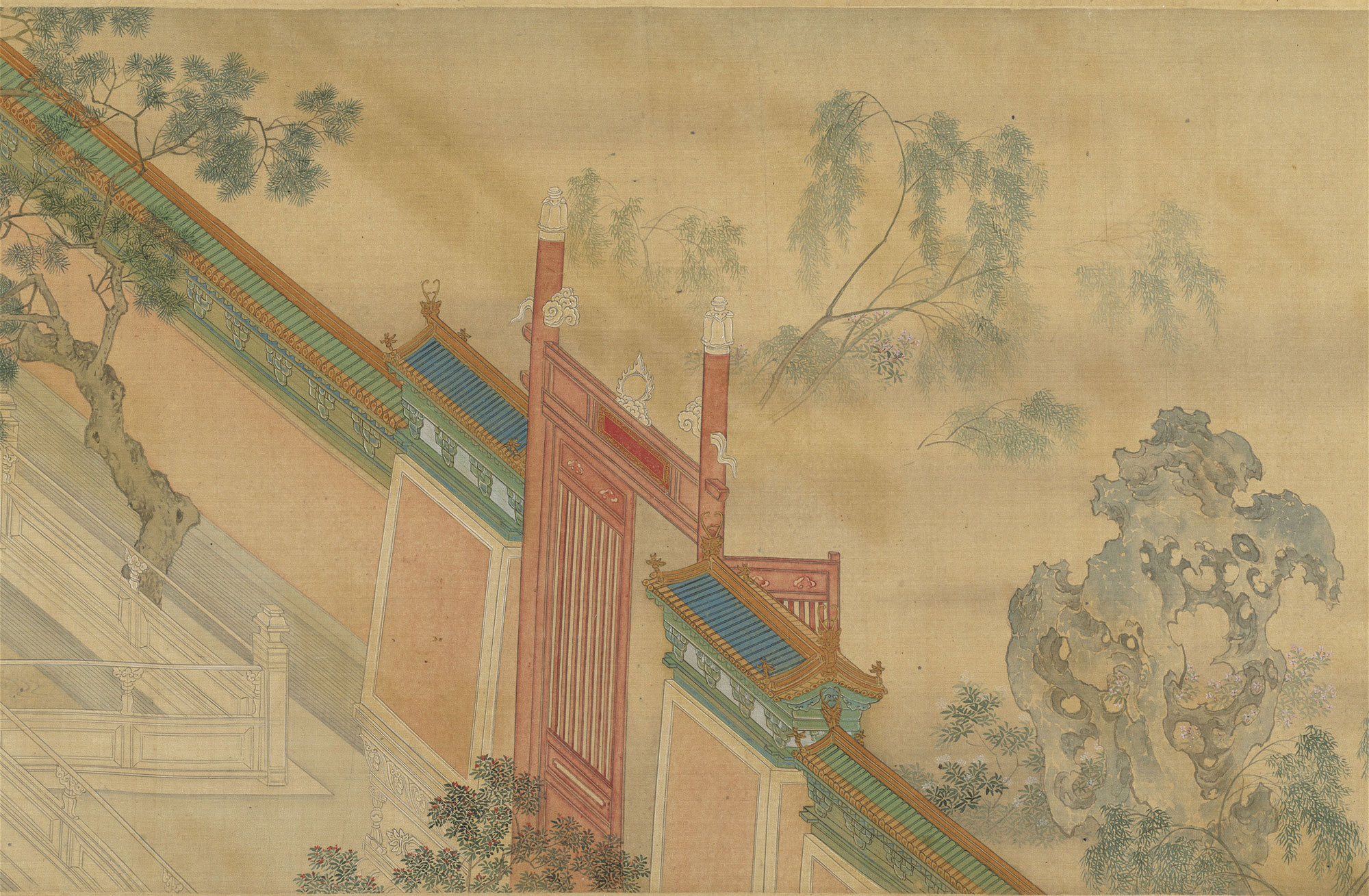

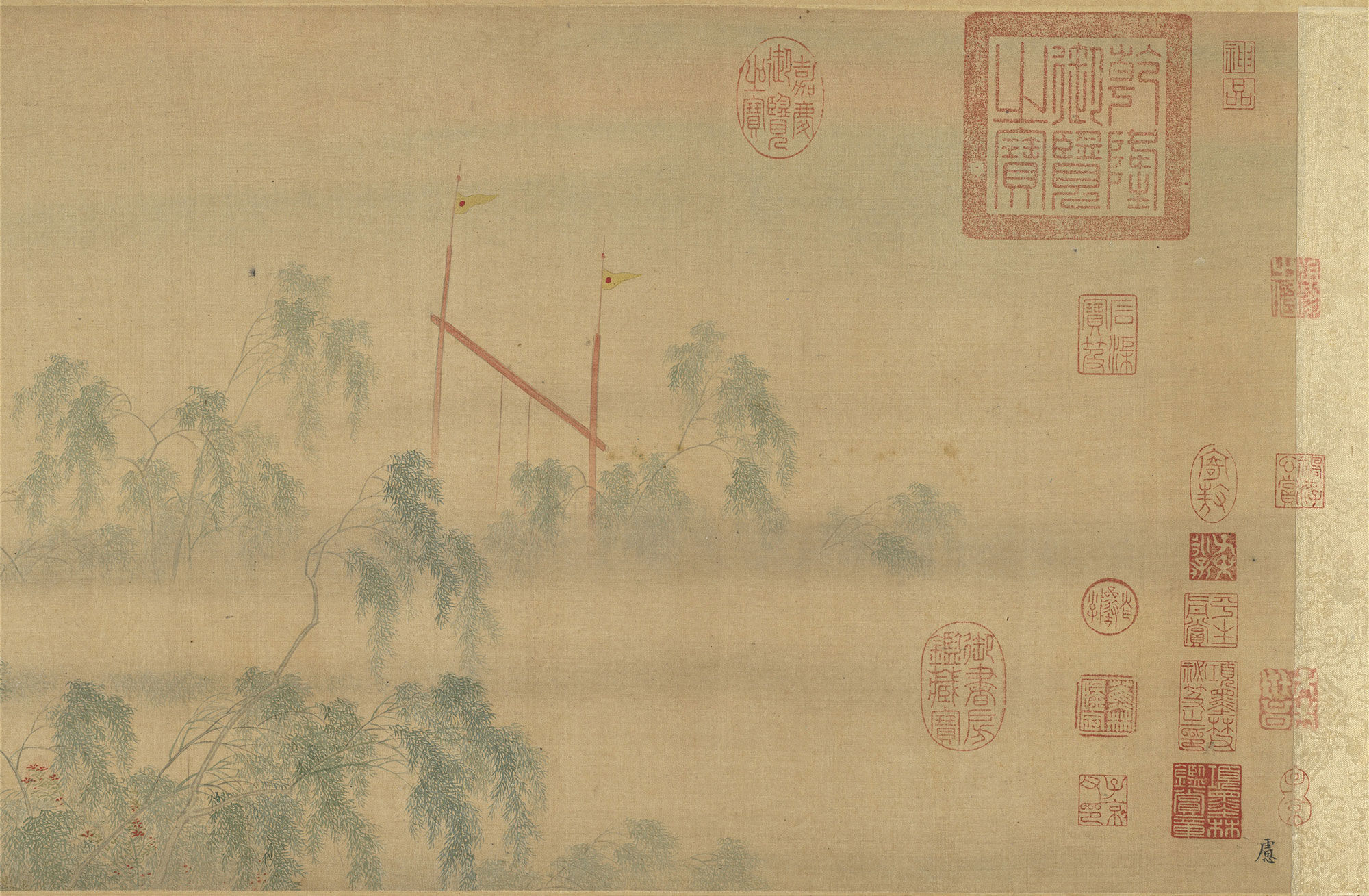

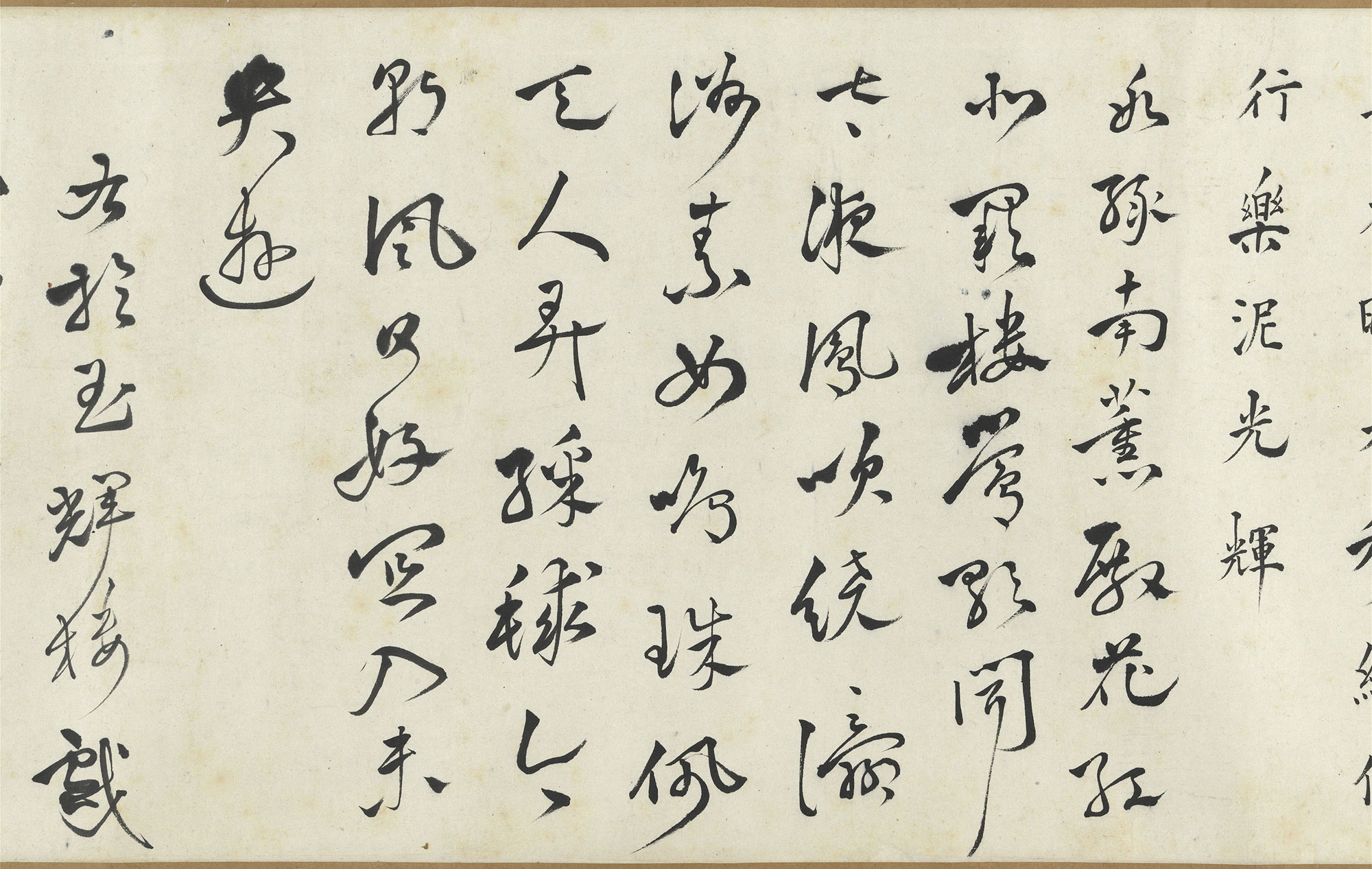

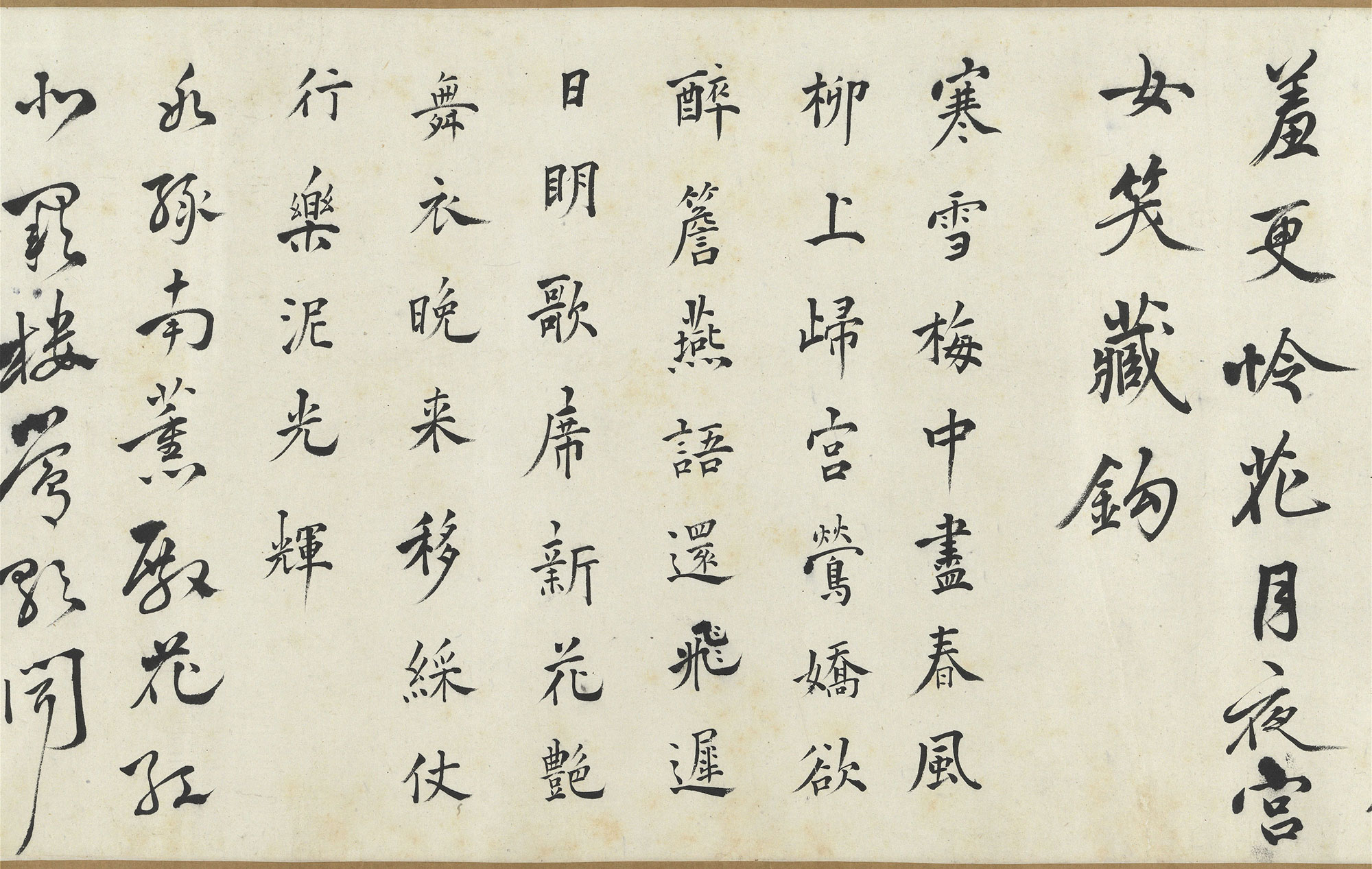

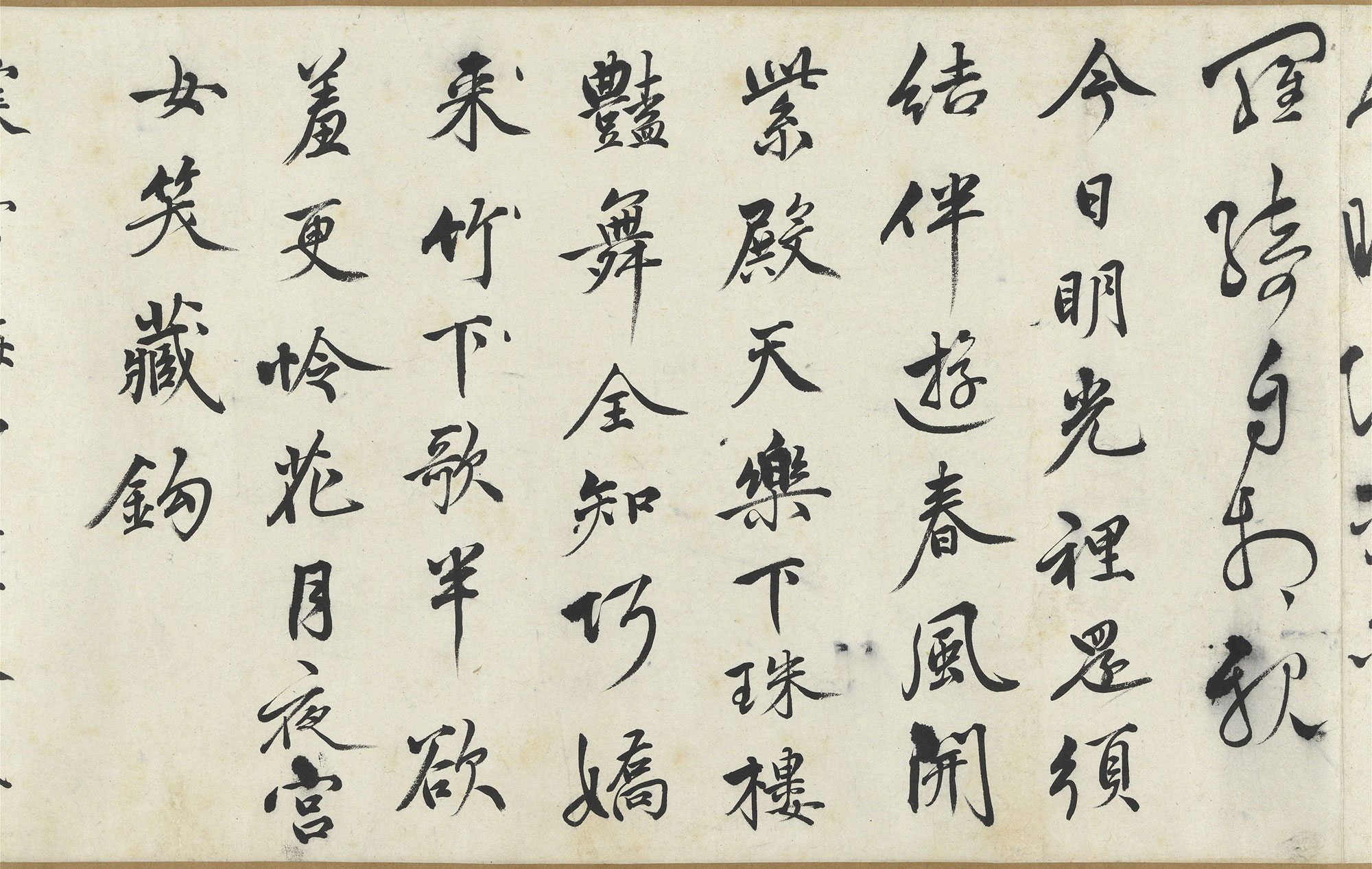

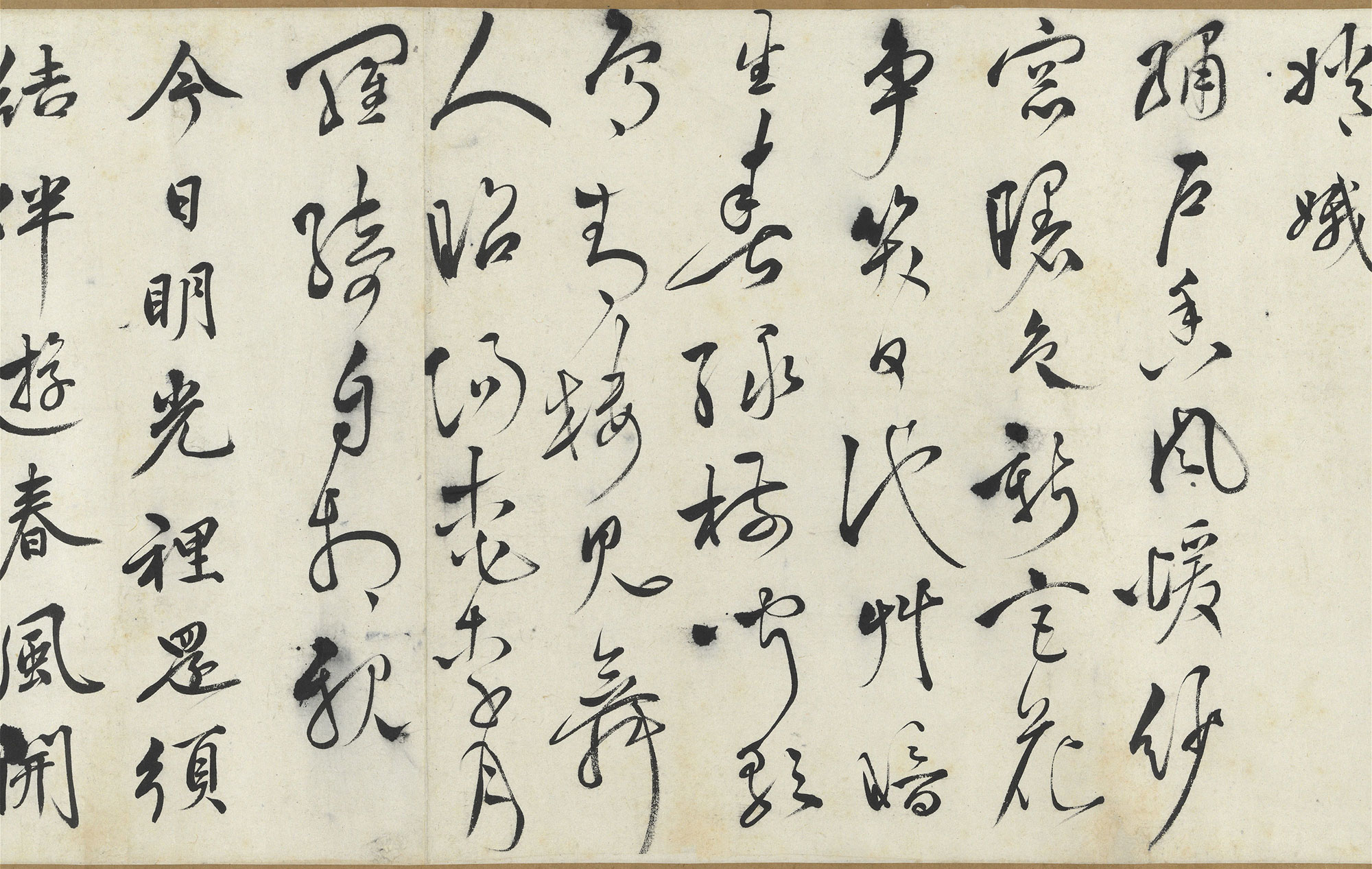

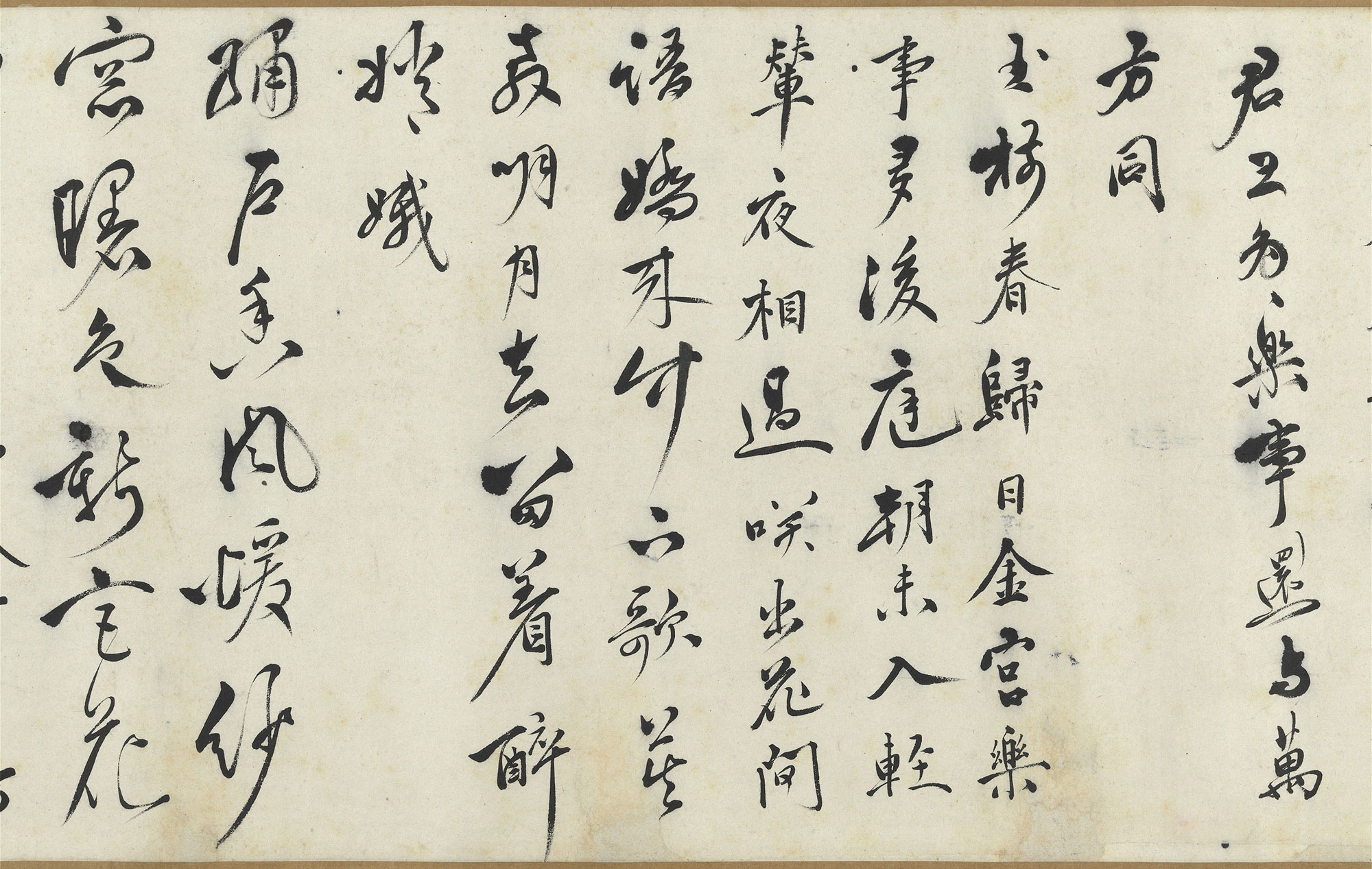

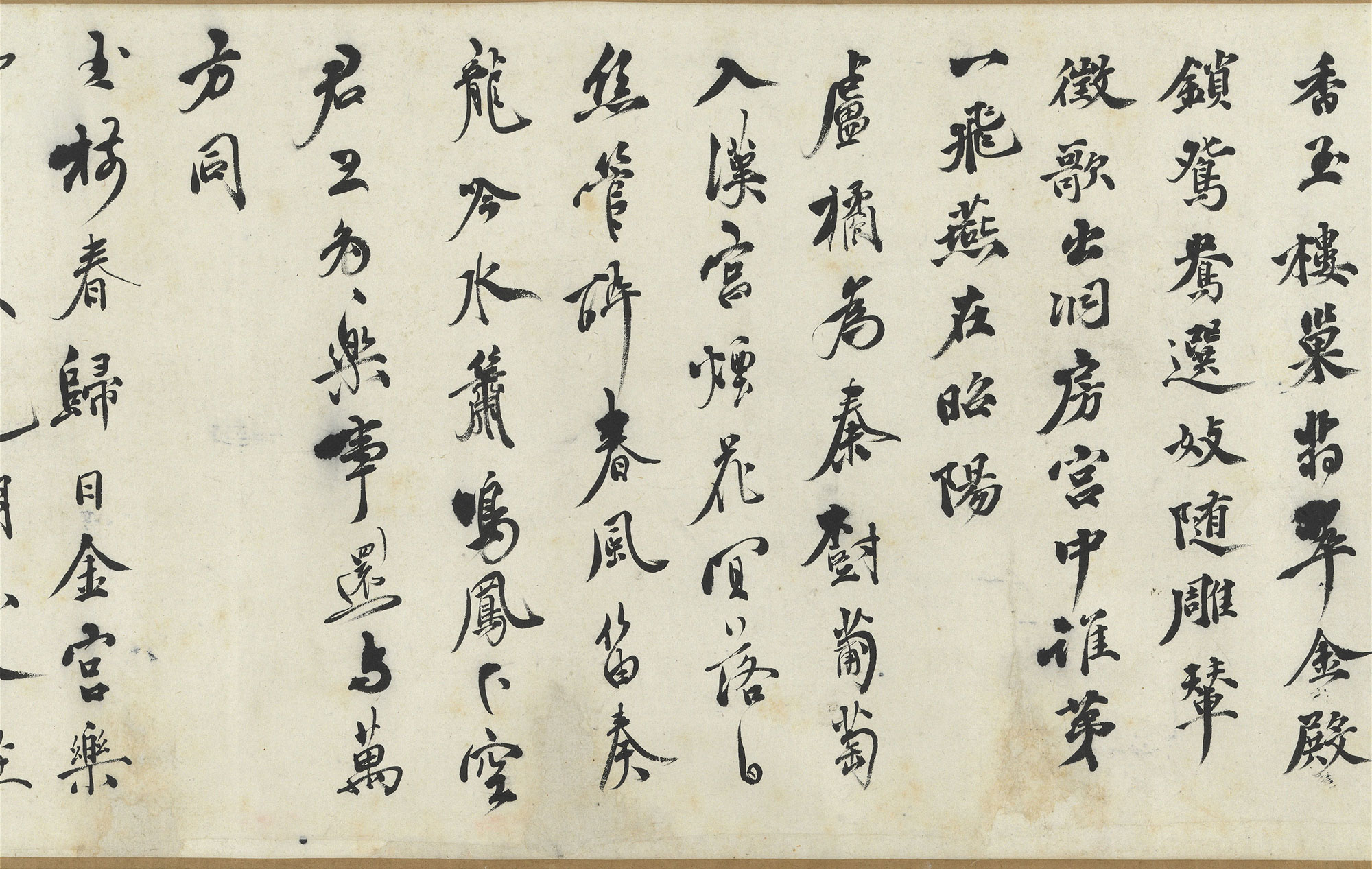

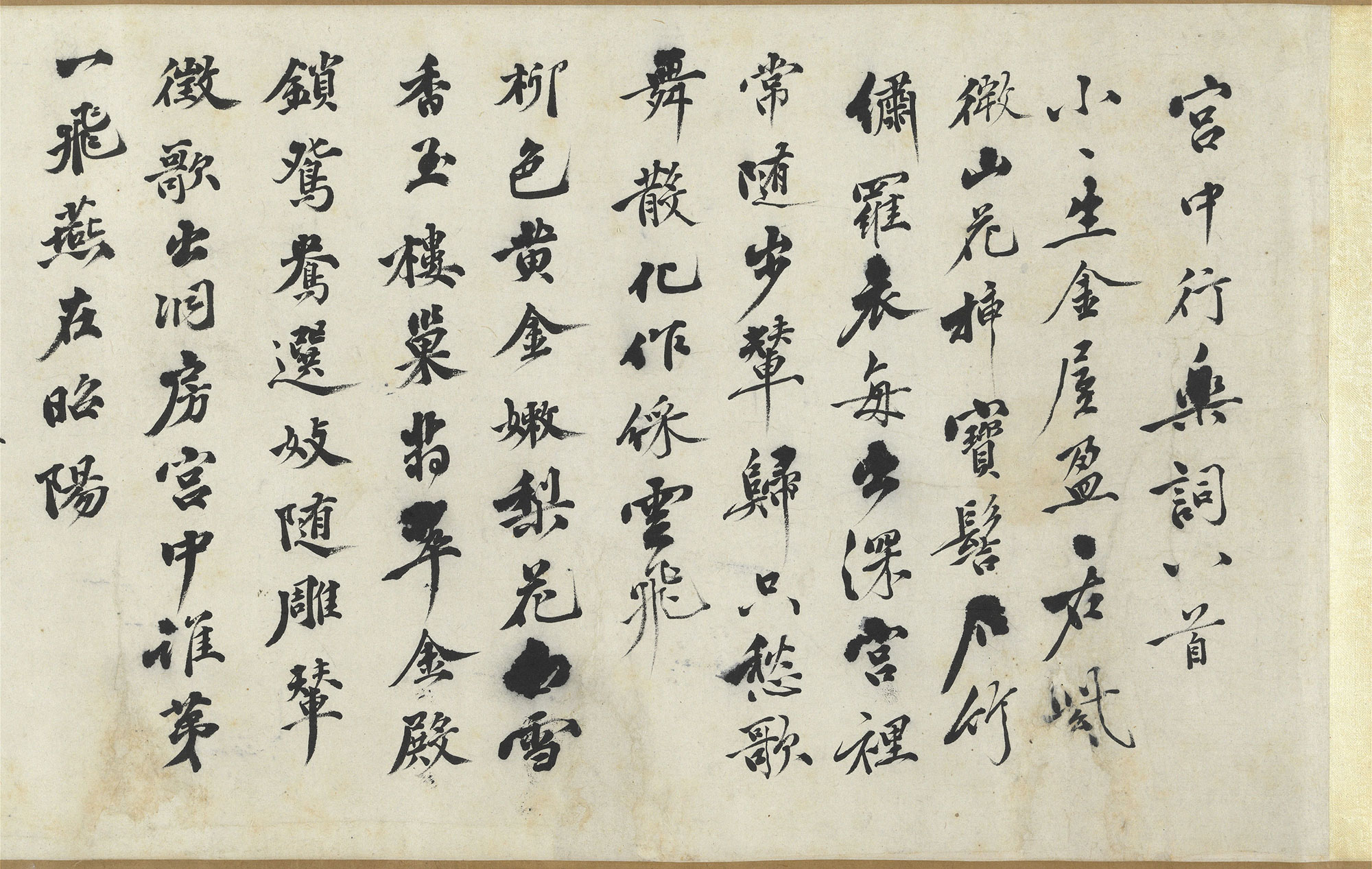

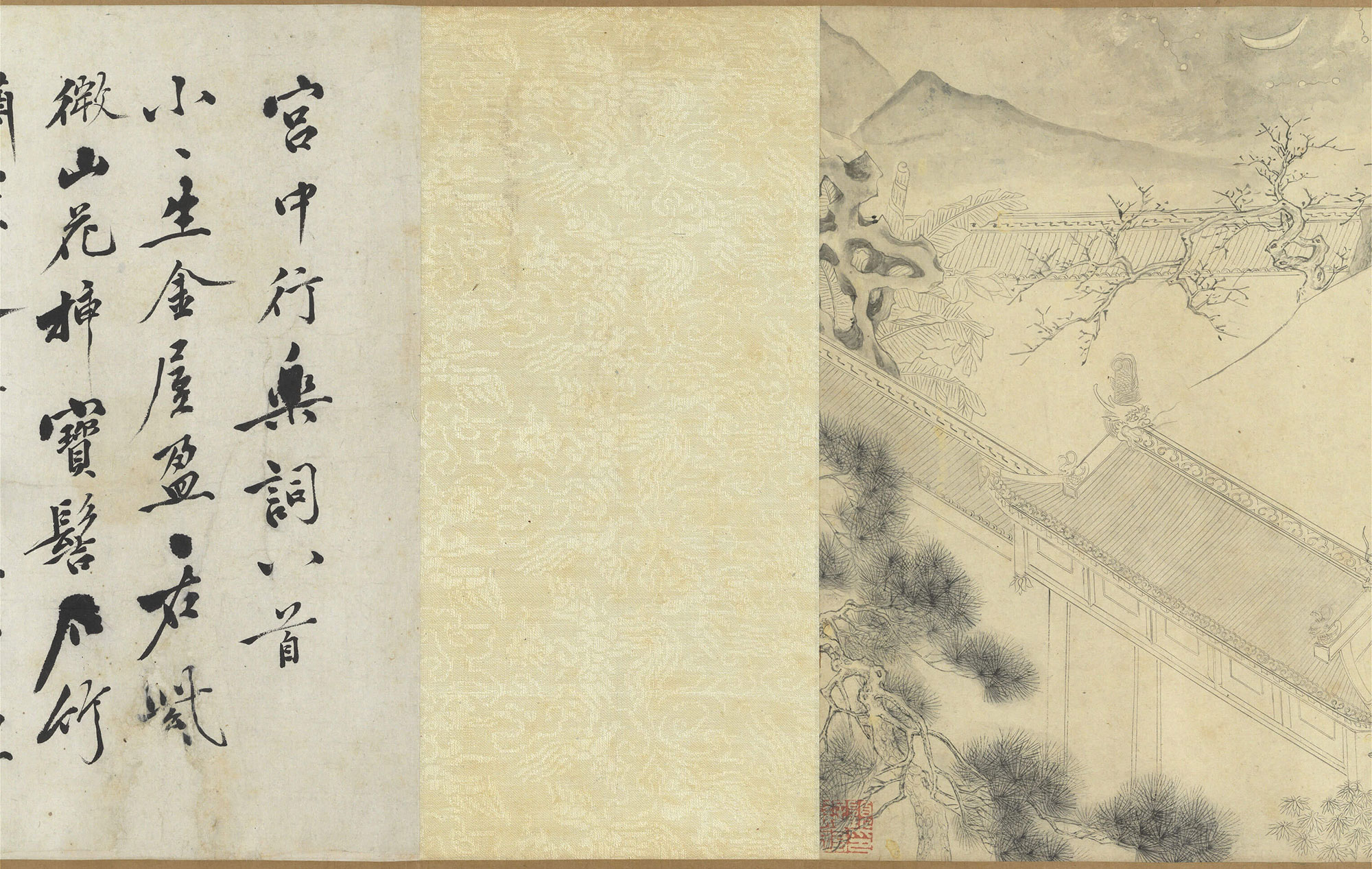

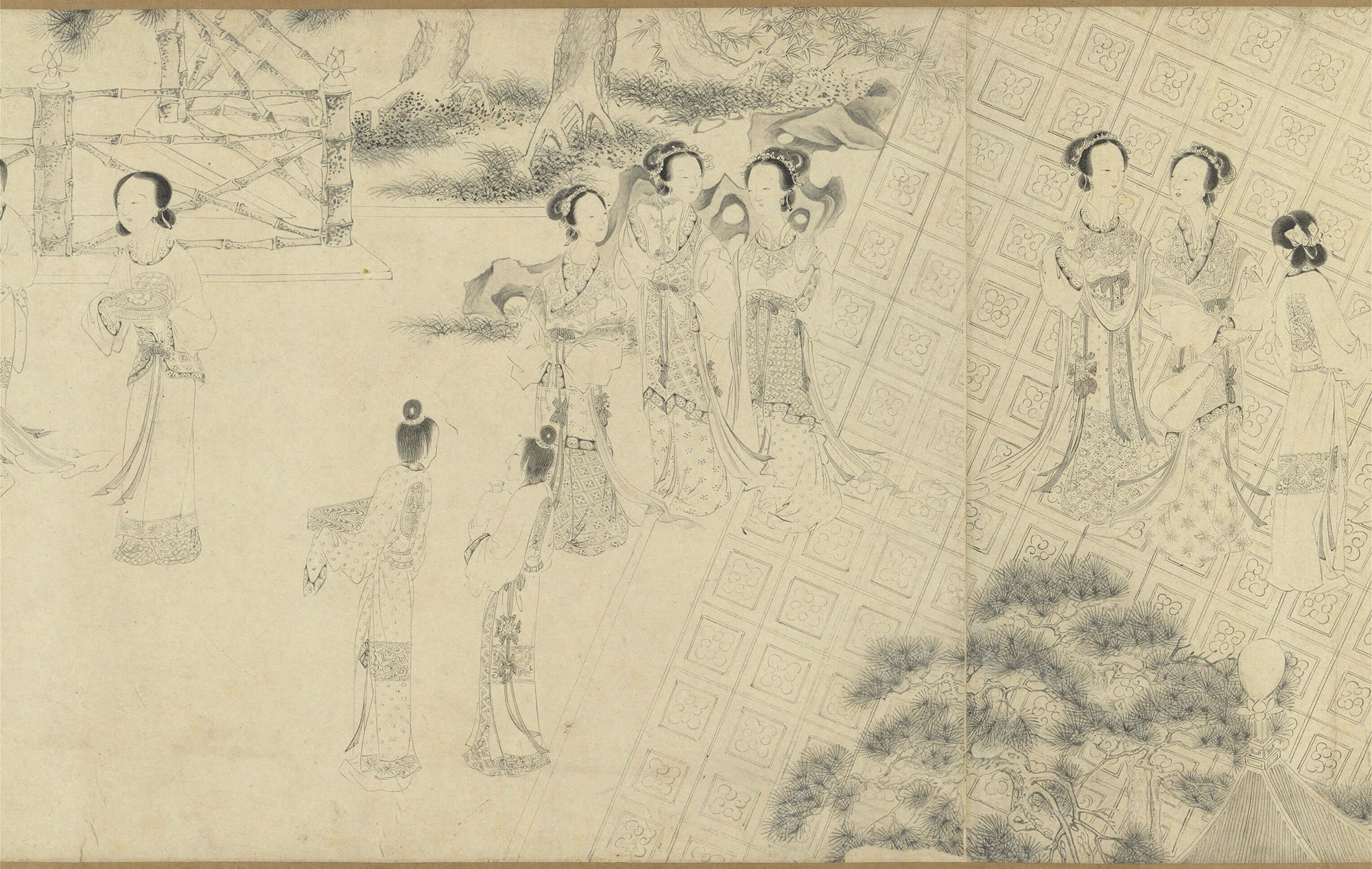

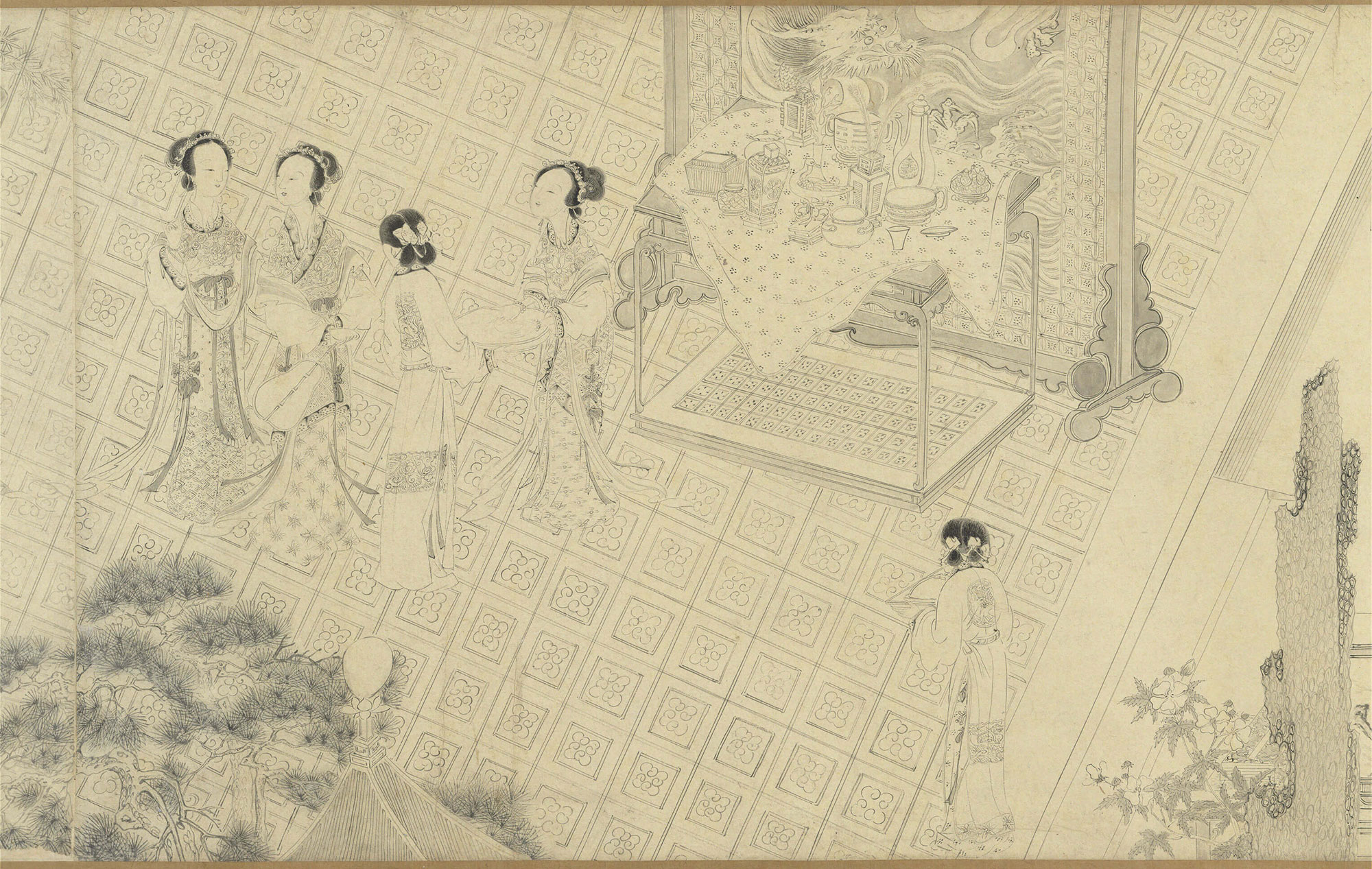

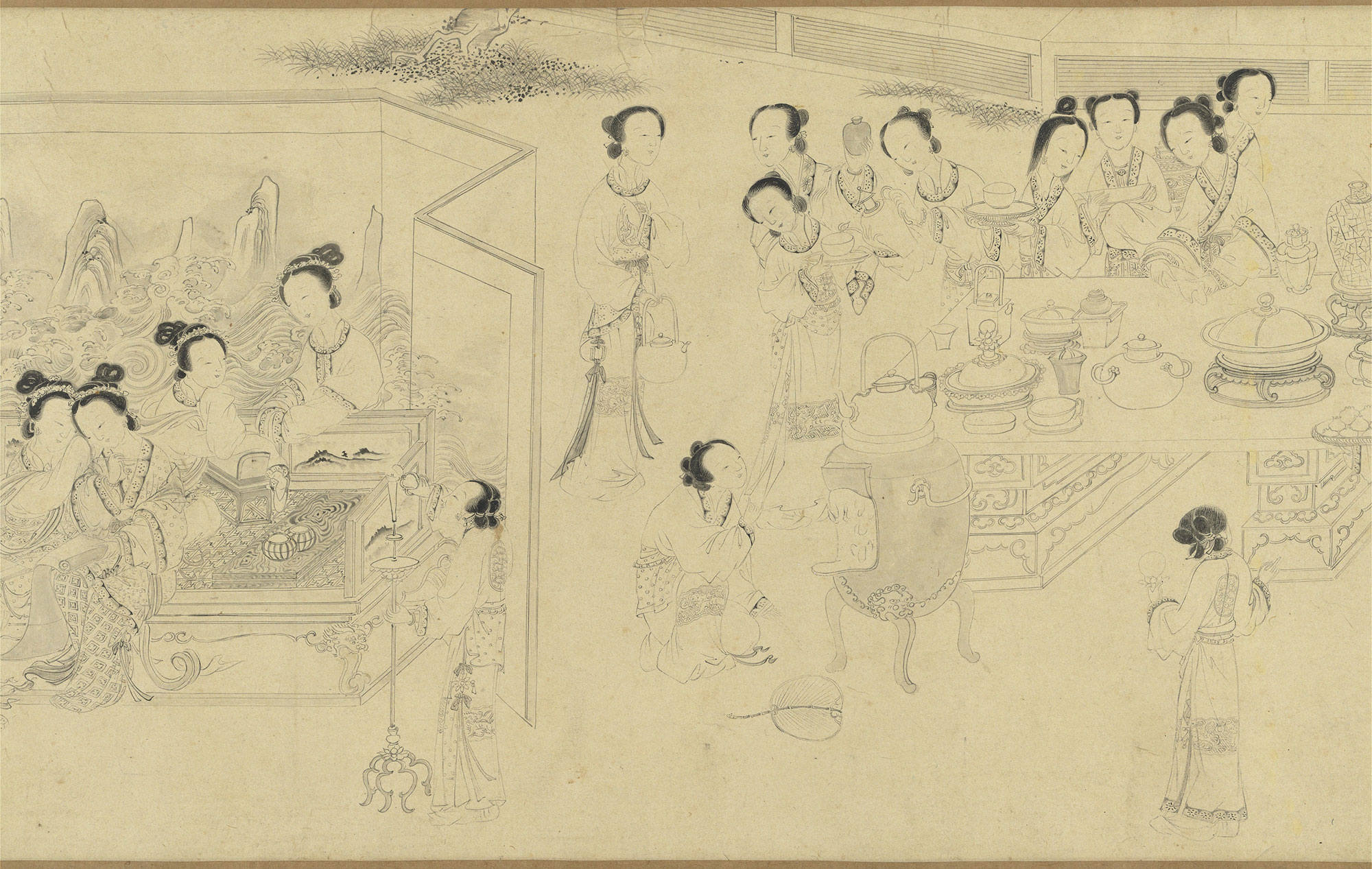

Spring Dawn in the Han Palace

- Qiu Ying (ca. 1494-1552), Ming dynasty

Qiu Ying (style name Shifu) was from Taicang in Jiangsu. His painting style was both opulent and scholarly, ranking him among the Four Ming Masters.

The background for this painting is the imperial gardens and palaces of the Han dynasty on a spring morning. Depicting various activities of palace ladies in the women's quarters, they include the famous story of the painter Mao Yanshou doing a portrait of Wang Zhaojun (ca. 54-19 BCE). The composition of the handscroll is complex and the brushwork crisp and strong; it is complemented by elegant and beautiful colors. In addition to the groupings of beauties are leisure activities associated with the literati, including the "Four Arts" of the zither, Go, calligraphy, and painting as well as the appreciation of antiquities and flower arrangements. This masterpiece of historical narrative painting is from Qiu Ying's later years.

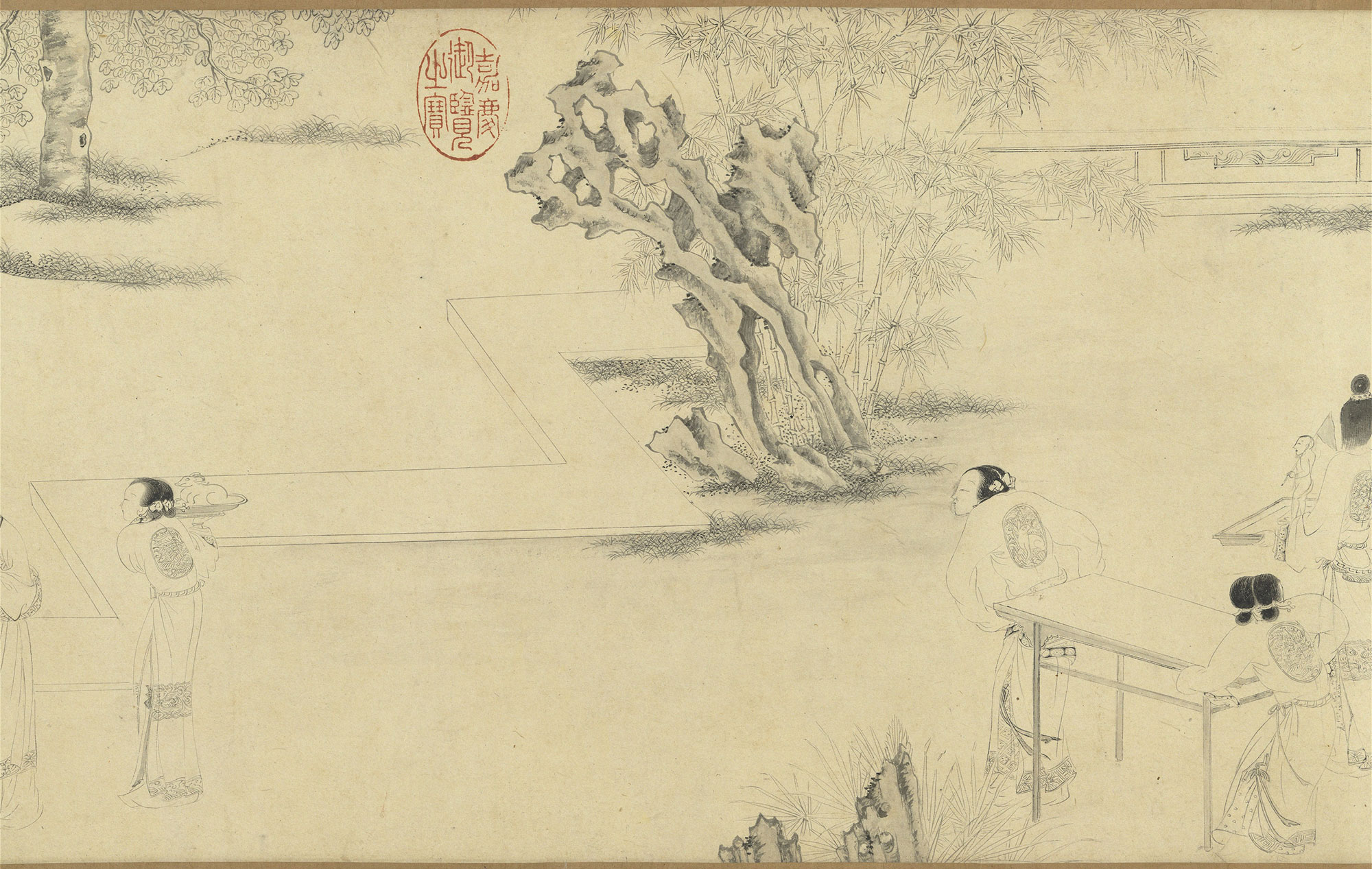

Test of Skill on the Double Seventh Day

- Qiu Ying (ca. 1494-1552), Ming dynasty

In the past, the most important custom on the Double Seventh Day (the seventh day of the seventh lunar month) was the test of needle and thread among women. In the evening, ladies would take colored strands to thread seven needles. In the courtyard would be placed an incense burner and an altar table on which offerings were made to a clay image of "Mohele," to which prayers were made for skill in weaving and having many sons. The painter here depicted various activities involving the Double Seventh Day, offering a glimpse at private life in the quarters of palace women and their elegant activities.

Although a seal and signature of the famous Ming artist Qiu Ying appear on a tree trunk in this painting, they were not authentic. Rather, the style appears closer to the school of You Qiu (fl. latter half of the 16th c.), a painter said to have been Qiu Ying's nephew.

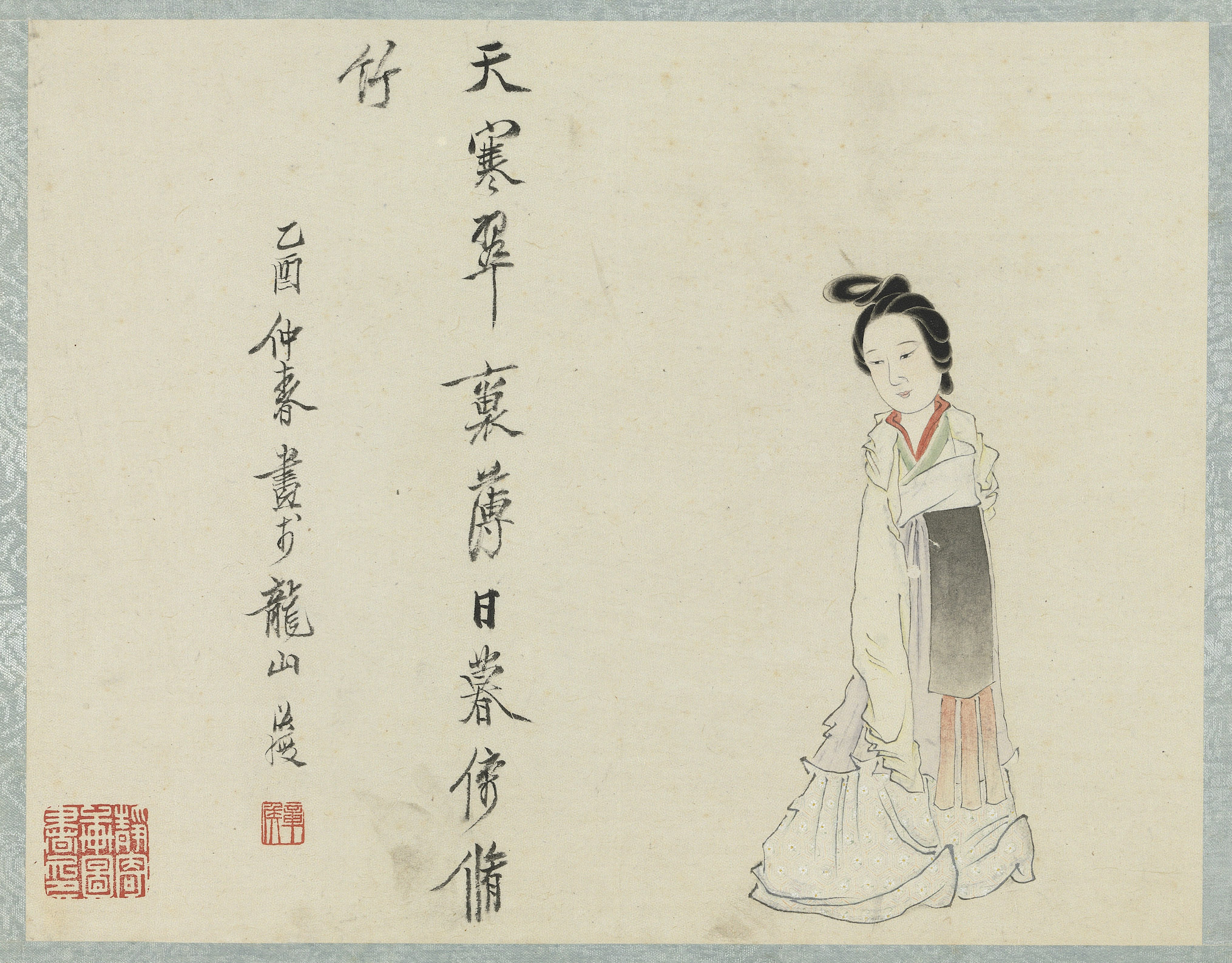

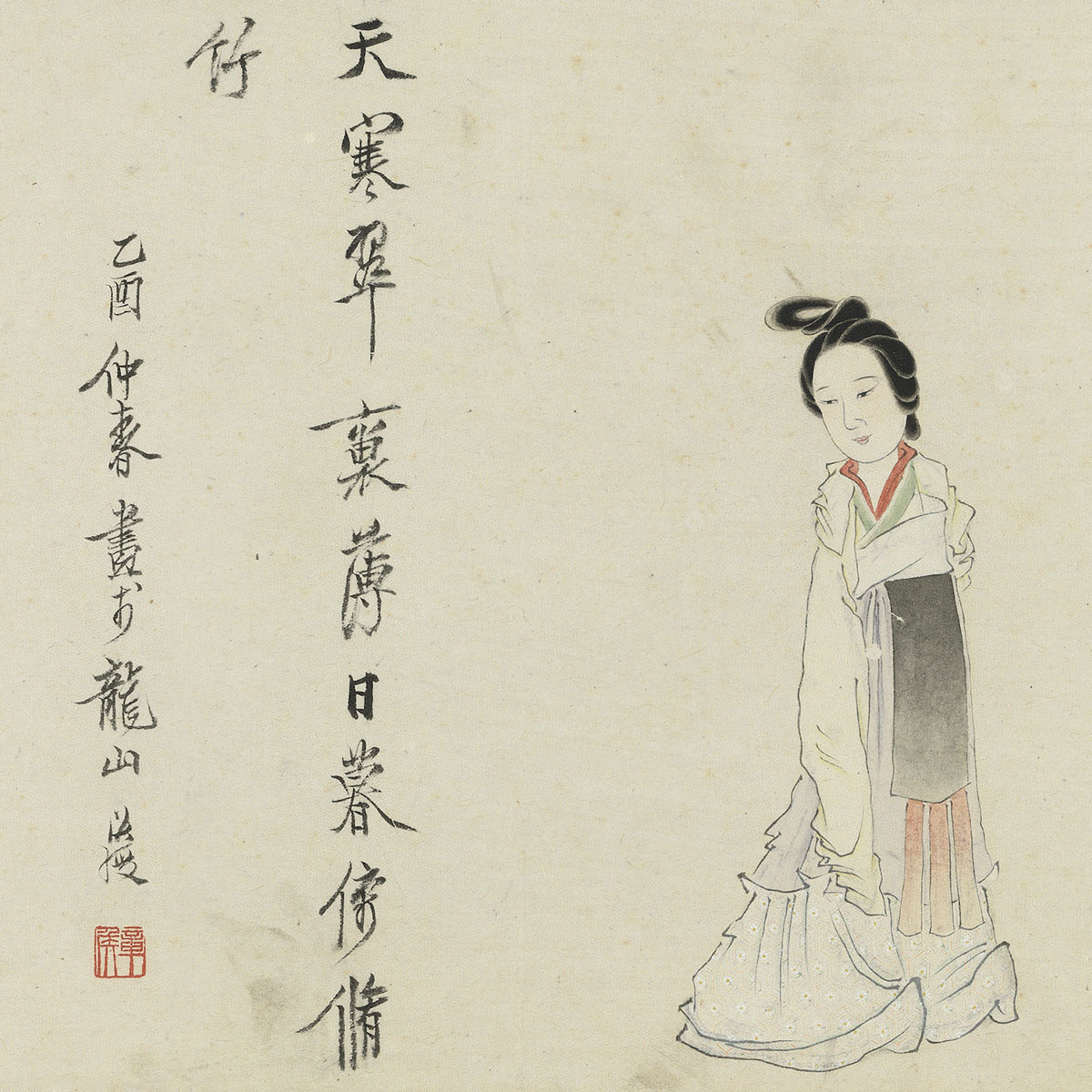

A Lady

- Chen Hongshou (1598-1652), Ming dynasty

Chen Hongshou (sobriquet Laolian) was from Zhuji in Zhejiang. His compositions often tend to be archaic and unusual in a manner that is innovative and engaging as well. He was a very influential painter of the so-called "Transformation School."

In this work, the sixth leaf from Chen's "Miscellaneous Paintings," stands a beautiful lady with her hair tied into a topknot. Rendered in delicate colors, her clothes are classical and the hues elegant and not vulgar. The brushwork is archaic and steady, the lines having angular twists that nonetheless conceal a rounded and even strength. It represents a masterpiece of his meticulous painting. To the left are two lines of poetry calligraphed by Chen himself that add further dimension to the painting, and his signature is dated to the "yiyou" year, placing it in his 48th year.

The Fragrance of Reading

- Chen Hongshou (1598-1652), Ming dynasty

Chen Hongshou (style name Zhanghou, sobriquet Laolian) was a native of Zhuji in Zhejiang who excelled at painting and was especially gifted at depicting figures.

"Sixteen Views of Living in Reclusion" is an album of paintings with sixteen leaves that depict the ideals of eremitic life using "baimiao" ink lines and also with light colors. All the paintings have historical allusions. "The Fragrance of Reading," for example, is the fifteenth leaf and depicts a lady sitting on a rock holding a book. She may refer to Yu Xuanji (ca. 844-868), a lady of talent in the Tang dynasty. After visiting a Taoist monastery in Chang'an and reading a list of the names for those who had passed the imperial examinations, she wrote, "I detest these gauze robes that veil my poetry, lifting my head in vain as I envy the names on the list." It shows a lady voicing her frustration at never being able to take a civil service exam, for men only and the path to success in traditional China, let alone to pass it.

Half Portraits of Xiao'an Empress and Xiaoding Empress

- Anonymous, Ming dynasty (1368-1644)

Neither of these portraits bears the seal or signature of the artist, the silk of both featuring posthumous titles of the ladies written in regular script using gold ink. The right leaf is a depiction of Empress Chen (?-1596), the wife of Emperor Muzong, while the left one depicts Muzong's Imperial Consort Li (Xiaoding, 1544-1614), the mother of Emperor Shenzong. After Shenzong assumed the throne, she was revered as the "Empress Mother" and became the last dowager empress of the Ming before it fell to the Qing.

Both empresses in these portraits are depicted frontally wearing crowns decorated with dragon-and-phoenix hair pins. They also have robes and shawls embroidered with dragons or pheasants. Despite the meticulous rendering of the details and complex coloring, the level of realism is a notch below that seen in imperial portraits from the previous Song and Yuan dynasties.

Gu Embroidery of Queen Mother of the West

- Anonymous, Ming dynasty (1368-1644)

"Gu embroidery," a term that emerged in the Wanli era (1573-1619) of the Ming dynasty, represented the work of women from the Shanghai clan of Gu Mingshi, a Presented Scholar of the Jiajing reign (1522-1566) who had a garden in Jiangnan, where he entertained friends in the arts of poetry, painting, and calligraphy. Women of the Gu family also took part in these elegant gatherings, using needle and thread instead of brush and ink to interpret paintings by masters of the Song and Yuan dynasties. Their embroidery eventually became an artistic activity synonymous with upper-class ladies.

This hanging scroll embroidery depicts the Queen Mother of the West, representative among female immortals in Taoism. The Queen Mother is holding a peach of immortality and rides upon a phoenix flying in a sky adorned with auspicious clouds. With a female attendant to her side, this is a common iconic form popular in folk traditions.

Dongpo and Chaoyun

- Zhu Da (1626-1705), Qing dynasty

Zhu Da, also know by his sobriquet Bada shanren, was from Jiangxi Province. Along with Hongren, Shixi, and Shitao, he was one of the "Four Monks."

In this painting are two paulownia trees, under which is the famous Song poet-artist Su Shi (Dongpo; 1037-1101) sitting on a chair and holding a fan. He leans on a table and gazes at Wang Chaoyun (1063-1096), the lady on the other side bending over to write. When Su Shi was serving as an official in Qiantang, he took the famous courtesan Chaoyun as his concubine. Originally illiterate, she later began to study from him. Later, Su Shi was banished to Huizhou and his family servants were dismissed, but he was so attached to Chaoyun that only she accompanied him there. Mr. Chang Chun donated this painting to the National Palace Museum.

Refining the Elixir of Immortality

- Huang Shen (1687-after 1768), Qing dynasty

Huang Shen, a native of Ninghua in Fujian with the style name Gongmou and the sobriquet Yingpiao, was a renowned artist of the Yangzhou School.

This painting depicts three of the Eight Immortals: He Xiangu (a woman), Li Tieguai, and Zhang Guolao. They are shown around a burner refining the elixir of immortality, the smoke of which wafts upwards to create a contrast between solid and void. The size of this painting is quite large, so the artist in his application of the strokes and colors took a bold and unrestrained approach. The drapery lines and figures' hair range considerably in terms of heaviness, density, and coarseness to create a dramatic visual effect that is stimulating and dynamic; it is clearly in a personal style of his own. Mr. Li Shih-tseng donated this painting to the National Palace Museum.

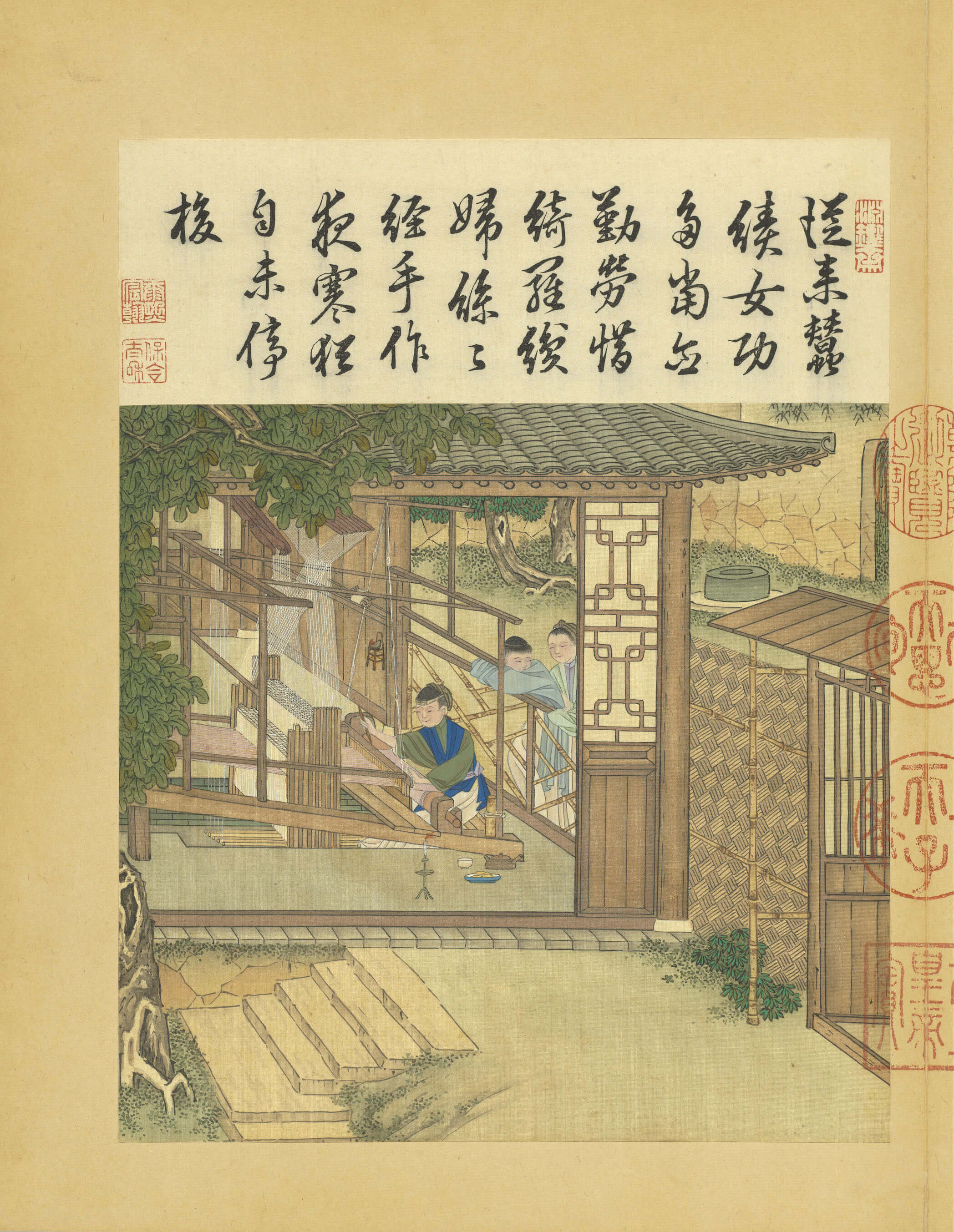

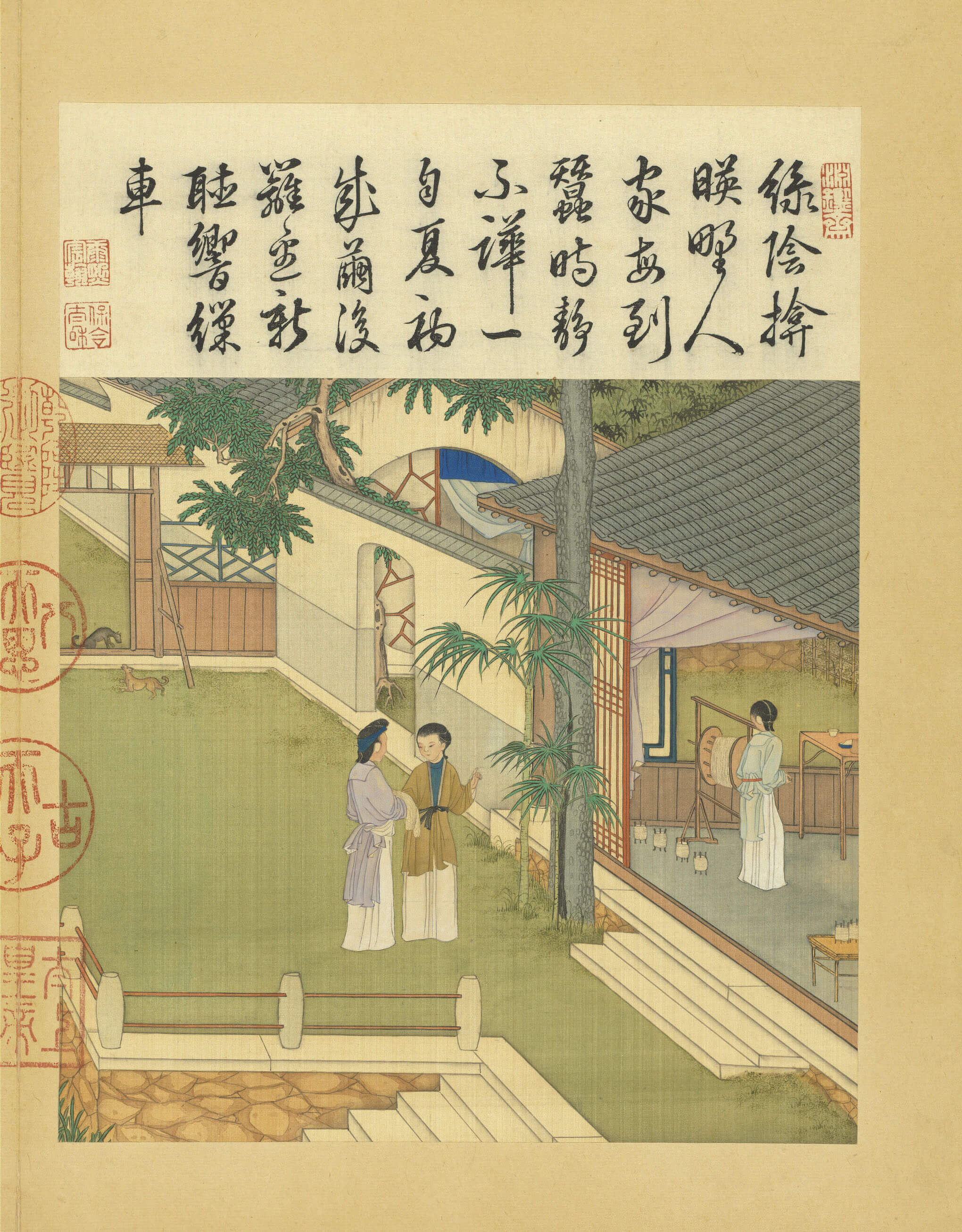

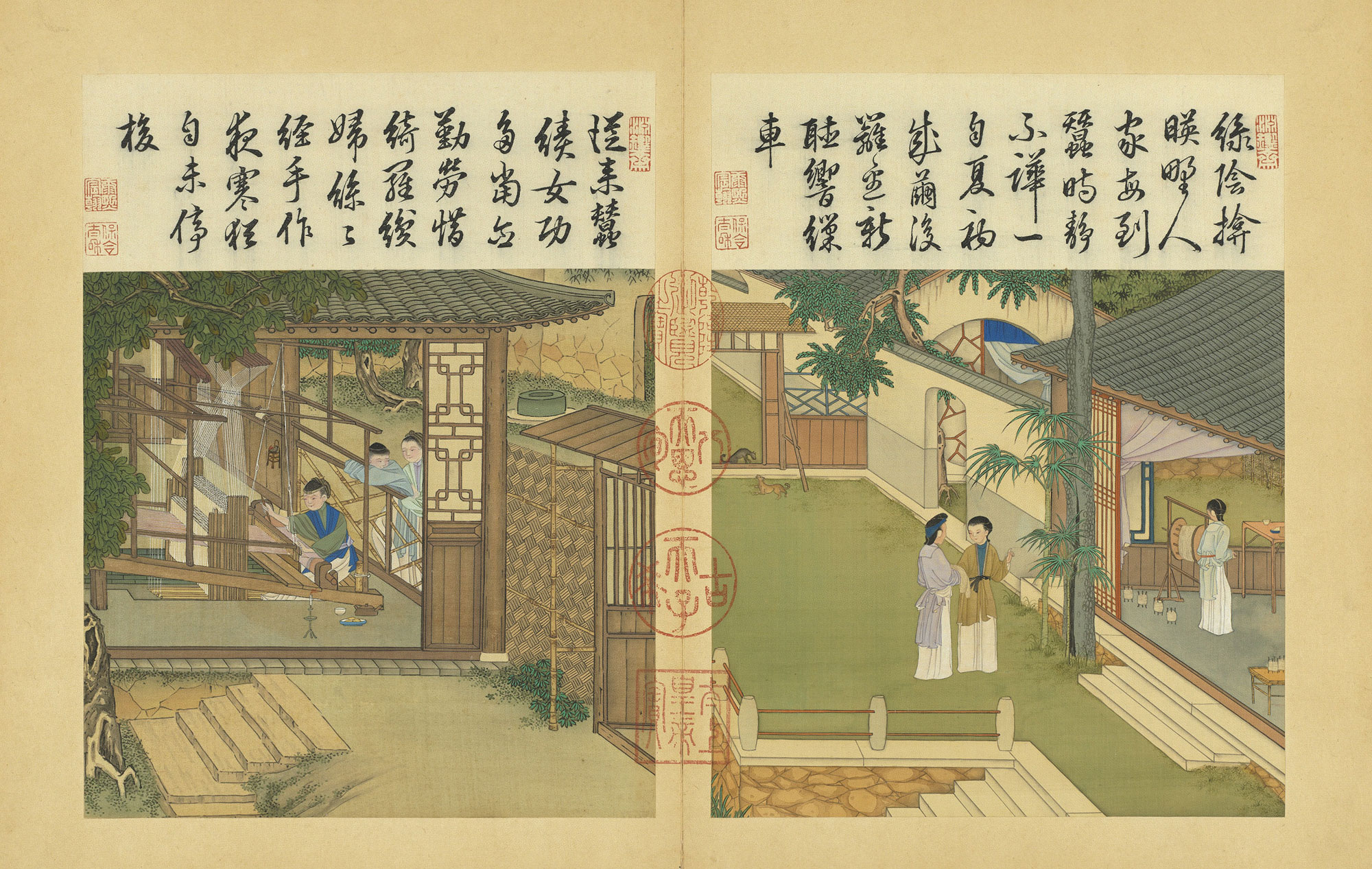

Agriculture and Sericulture

- Leng Mei (fl. late 17th-early 18th c.), Qing dynasty

Leng Mei, from Jiaozhou in Shandong, was a student of Jiao Bingzhen (fl. 1689-1726). Leng excelled at painting figures and "ruled-line" subjects; he was especially gifted at depicting ladies. Serving as a court artist in the Kangxi and Qianlong reigns, his style was refined and elegantly beautiful.

Illustrations of the production of silk (sericulture) and cultivation of crops (agriculture) go back to the Southern Song period. Depicting the division of labor between men and women in the agrarian society of old, men did the work of tilling the fields while women were busy with activities related to weaving. In the Kangxi reign during the Qing dynasty, Jiao Bingzhen was ordered to recompile existing images on this subject that were then printed for distribution. Leng Mei reworked Jiao's prototype for own depiction with Western perspective and chiaroscuro to give it more color and volume.

Joyous Celebrations at the New Year

- Yao Wenhan (1713-?), Qing dynasty

Yao Wenhan, native to Shuntian (modern Beijing), was good at painting figures, especially Buddhist and Taoist subjects. In 1743, during the Qianlong reign, he held the title of Painter at the Ruyi Hall.

After the Manchu assumed control of China in the Qing dynasty in 1644, they paid much attention to the painting of subjects dealing with Han Chinese festivals. According to records in Archives of the Workshops Governed by the Imperial Household Department, for important festivals the Qing court would often form a group of painters to do a related project for presentation to the emperor for his review and celebratory display. The painting here depicts the whole family together at the time of the Lunar New Year engaged in festive scenes. Children play in the yard and in a building at the back is a group of women busy making preparations that serves as a contrast.

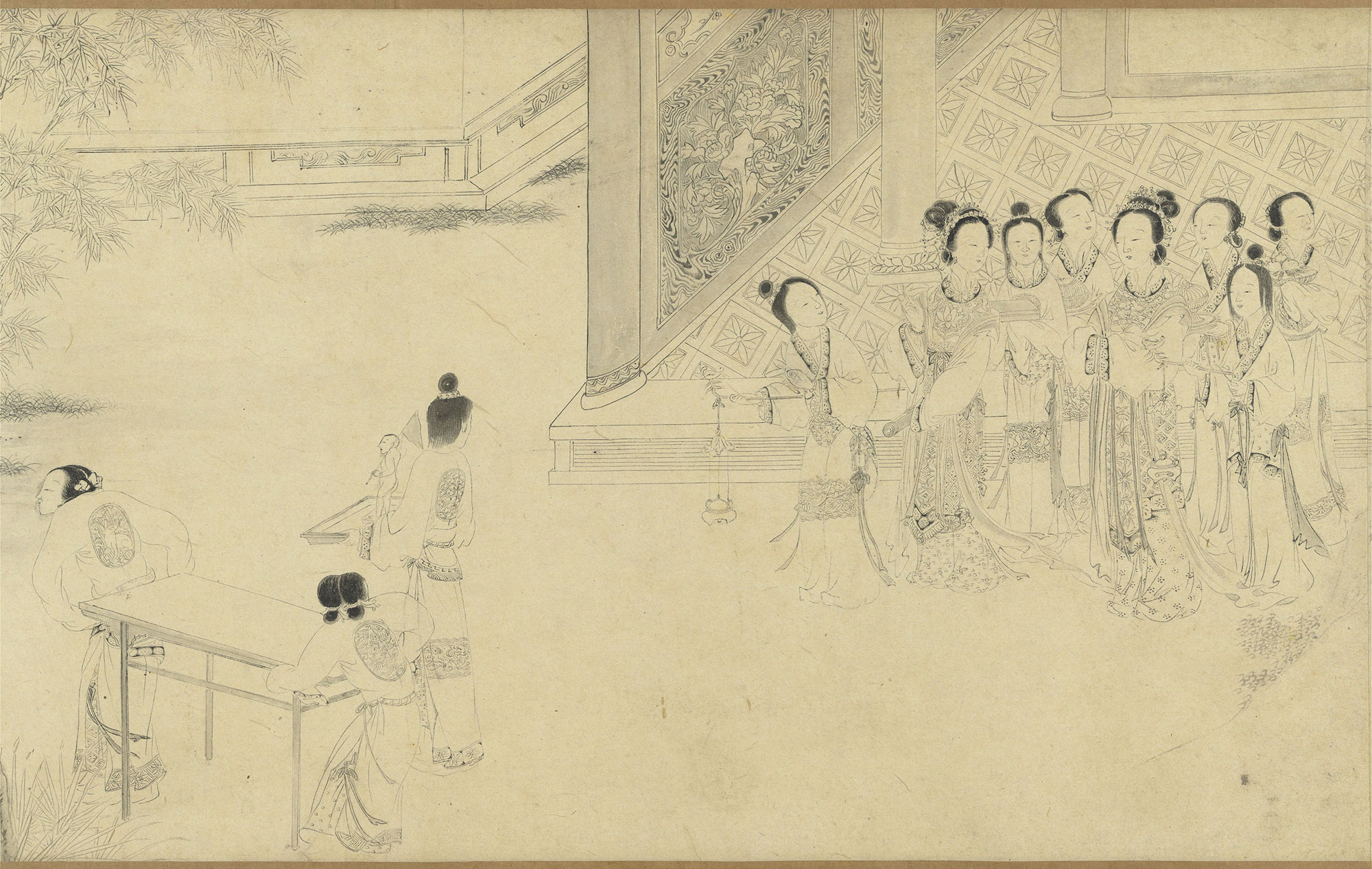

Cao Dagu Teaching

- Jin Tingbiao (?-1767), Qing dynasty

Jin Tingbiao, style name Shikui, hailed from Wuxing in Zhejiang.

This painting illustrates the story of Ban Zhao (ca. 45-117), also known at the Eastern Han dynasty court as "Cao Dagu," or Venerable Madame Cao. Here, two ladies appear at the side and watch as a child causes a ruckus to enliven this scene of giving instruction. The figures are rendered with finesse and the coloring elegant, reflecting the painter's attention to the subject matter. Ban Zhao was the daughter of Ban Biao (3-54 CE) and married Cao Shou. Learned and talented, she completed the work of her brother Ban Gu on History of the [Western] Han. She also was called several times to the court, where she taught the empress and other members of the nobility and hence called "Cao Dagu."

Cao Dagu Teaching

- Luo Ping (1733-1799), Qing dynasty

Luo Ping (style name Dunfu; sobriquets Liangfeng and Huazhisi seng) lived in Yangzhou and was a student of the artist Jin Nong (1687-1763).

Su Xiaoxiao is said to have been a famous courtesan in Qiantang during the Southern Qi dynasty (479-502) of the Six Dynasties period. She was admired by many for her courage in advancing ideas about the pursuit of love, and scholars over the ages have composed songs of praise for her. This portrait of Su Xiaoxiao portrays her in the dress of the Qing dynasty and has a unique way of handling the drapery lines and accessories. Her face is rendered in traditional painting methods to convey the complex and subtle features of her character. This painting has been entrusted to the National Palace Museum from the Lan-ch'ien shan-kuan collection .

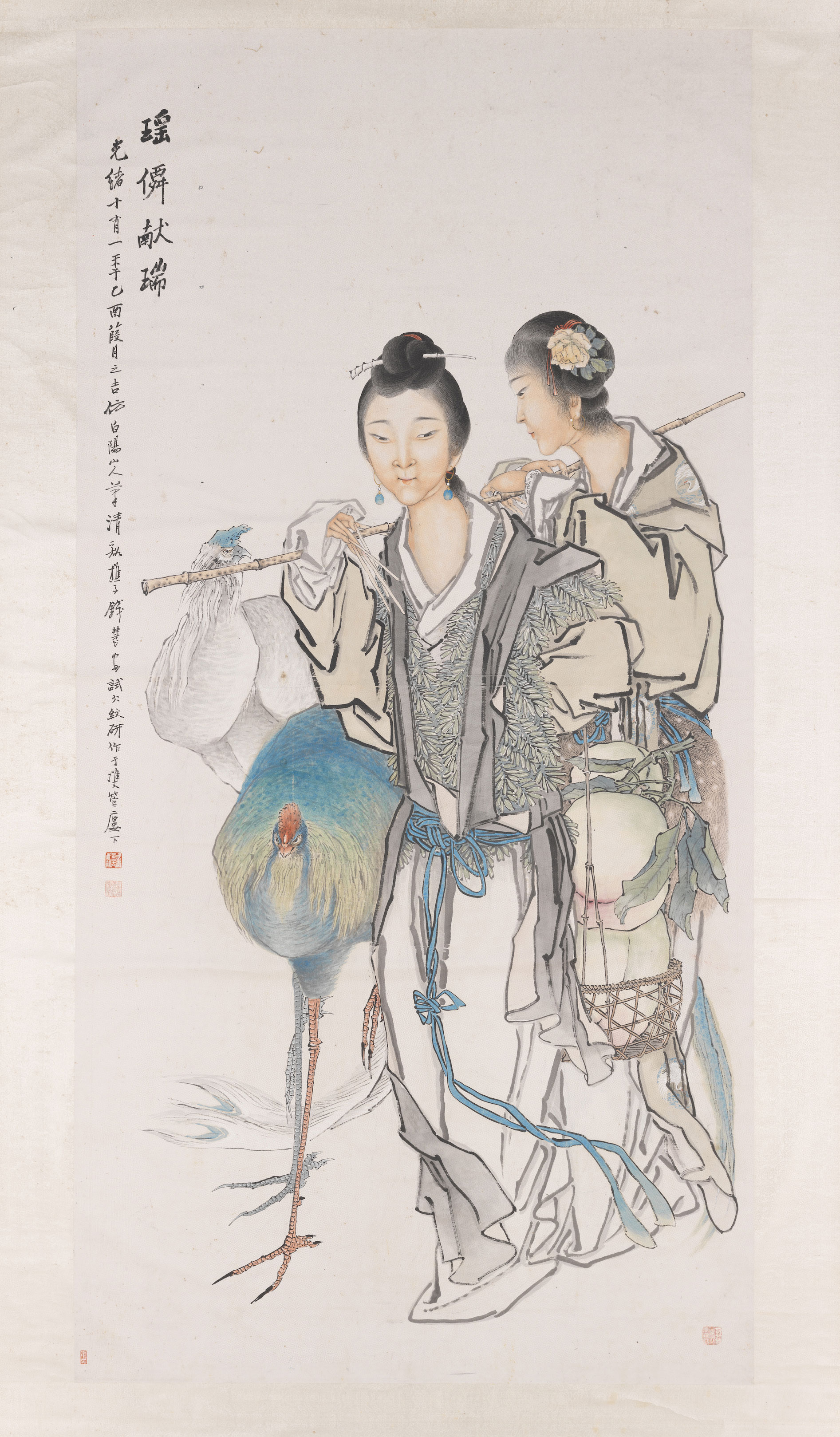

Maiden Immortals Offering Auspicious Gifts

- Luo Ping (1733-1799), Qing dynasty

Qian Hui'an (style name Jisheng, sobriquet Shuangguan louzhu) was a native of Baoshan (modern Shanghai). His style of painting incorporated Western techniques, and he became a famous artist of the Shanghai School.

This painting depicts immortal ladies bringing gifts of longevity, a highly auspicious theme typical among the people to convey the idea of birthday blessings. The drapery lines of the maidens are taut and powerful, the expressions on their faces elegant and agreeable. Although the artist claimed in his inscription to have followed the painting methods of "Baiyang shanren," referring to Chen Chun (1484-1543), the manner is far closer to his own style, giving the work a clearly personal and period touch.

Portrait in Oils

- Anonymous, Qing dynasty (1644-1911)

This painting depicts a woman dressed in armor. At one time in the early twentieth century it was thought to be a portrait of the "Fragrant Concubine (Xiangfei)," a consort of the Qianlong emperor in the eighteenth century. However, her visage differs from that usually associated with the Uyghur ethnic group, to which she belonged. The figure here is assumed then to be somebody else. The Manchu excelled at horsemanship, and, after taking control of the country in the Qing dynasty, continued to promote the spirit of martial skills. The emperor on a hunting trip was often accompanied by his consorts, princes, and daughters. Images of women wearing armor or hunting on horseback from this time offer a unique view of some women in the Qing palaces as being no strangers to military matters.

This painting is thought be have once been a detail from a wall painting ("tieluo") at a Qing palace. Whether it was painted by Giuseppe Castilgione (Lang Shining, 1688-1766), the famous Italian painter at the court, is still unknown.

Lady with a Cassia Twig

- Anonymous, Qing dynasty (1644-1911)

To pass the civil service examinations was probably the most important thing in the life of a Chinese scholar in the past. Records in Notes Done Whiling away the Summer from the Song dynasty indicate that such expressions as "breaking a cassia twig" and "ascending to the Toad Palace (moon)" were metaphors for achieving a name and place among those who passed the examinations. For this reason, paintings with these subjects became symbolic of auspiciousness.

The anonymous painter here used fluid lines and delicate colors to render the head and hand of the lady to suggest a warm and tender character. The folds of her robes are done with larger and more exaggerated strokes, the contrast making this a fine example of Qing dynasty lady painting. The peaceful and serene expression of the woman makes her appear as if deep in thought, the twig of cassia in her hand perhaps revealing hope for the future.

Lady with a Cassia Twig

- Pu Hsin-yu (1896-1963), Republican period

Pu Ru, who was from Wanping in Hebei (modern Beijing), was also better known by his style name Xinyu (Hsin-yu) and had the sobriquet Xishan yishi.

A lady is shown sitting next to a Taihu garden rock holding a round fan daintily in her hand that rests on the rock. Her suggestive gaze and delicate pose convey an air of flirtatious beauty. Not only is the composition of this work quite skillfully arranged, the artist's calligraphy next to her is also exceptional, the lines revealing power within the softness to create an ideal complement to the unique style of this lady painting. Pu Hsin-yu appears to have particularly admired this arrangement, because he did it several versions of the painting as gifts for friends. This work has been entrusted to the National Palace Museum by Pu's Cold Jade Hall.

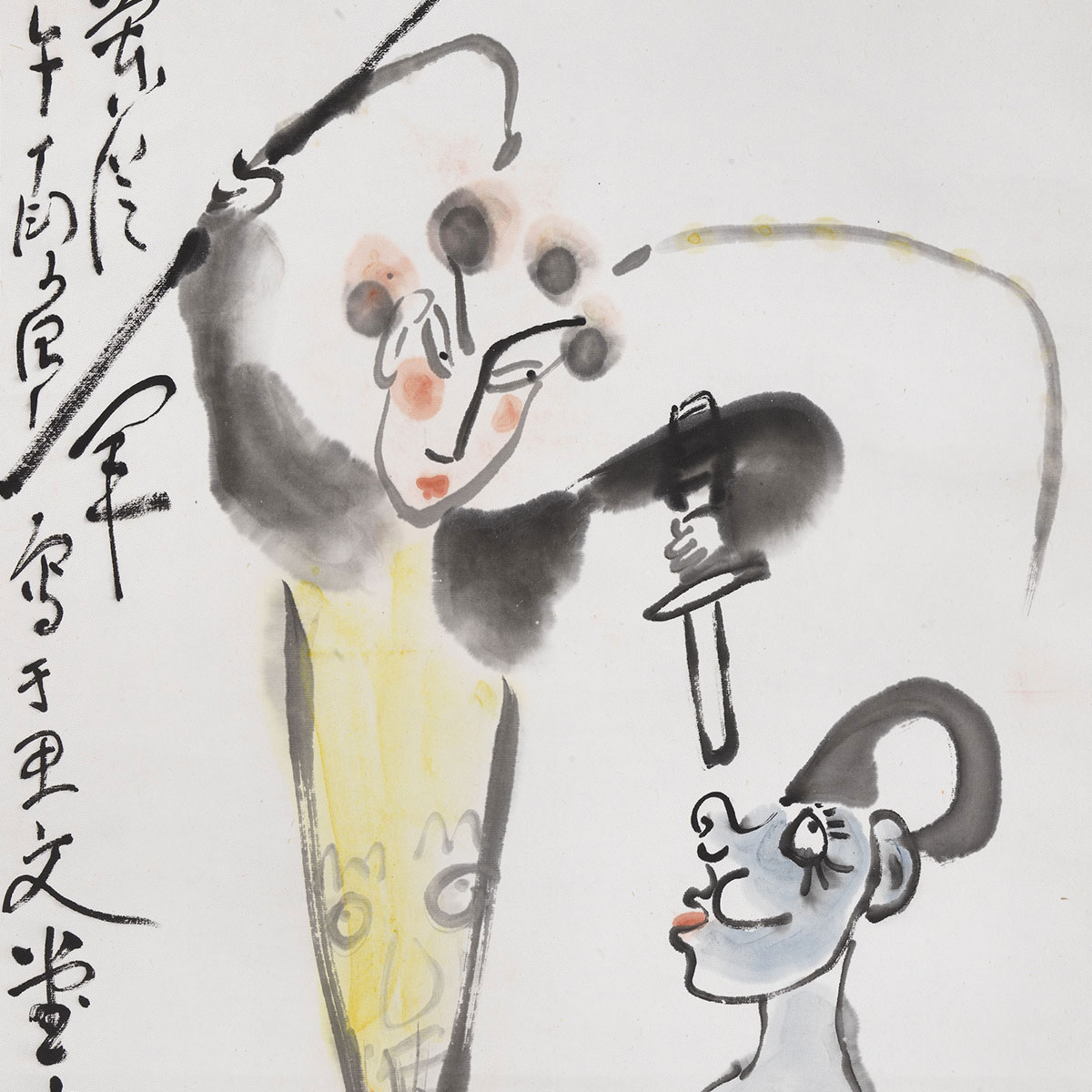

Beauty and a General

- Lin Fengmian (1900-1991), Republican period

Lin Fengmian, a native of Meixian in Guangdong, went to study in France and later became a pioneer of contemporary Chinese art.

Around the late 1940s, Lin started to do paintings of figures from traditional Chinese opera. He hoped to explore expressions of color and form through familiar characters and roles in the Chinese figural tradition. In this painting is a famous scene from "The Hegemon-King Bids His Concubine Farewell," in which Xiang Yu (232-202 BCE) tries to stop his Consort Yu (?-202 BCE) from killing herself. Operatic clothing and roles have been transformed into modern abstractions of geometric forms. Combined with the strong and vivid colors, the work also has the quality of Cubist painting.

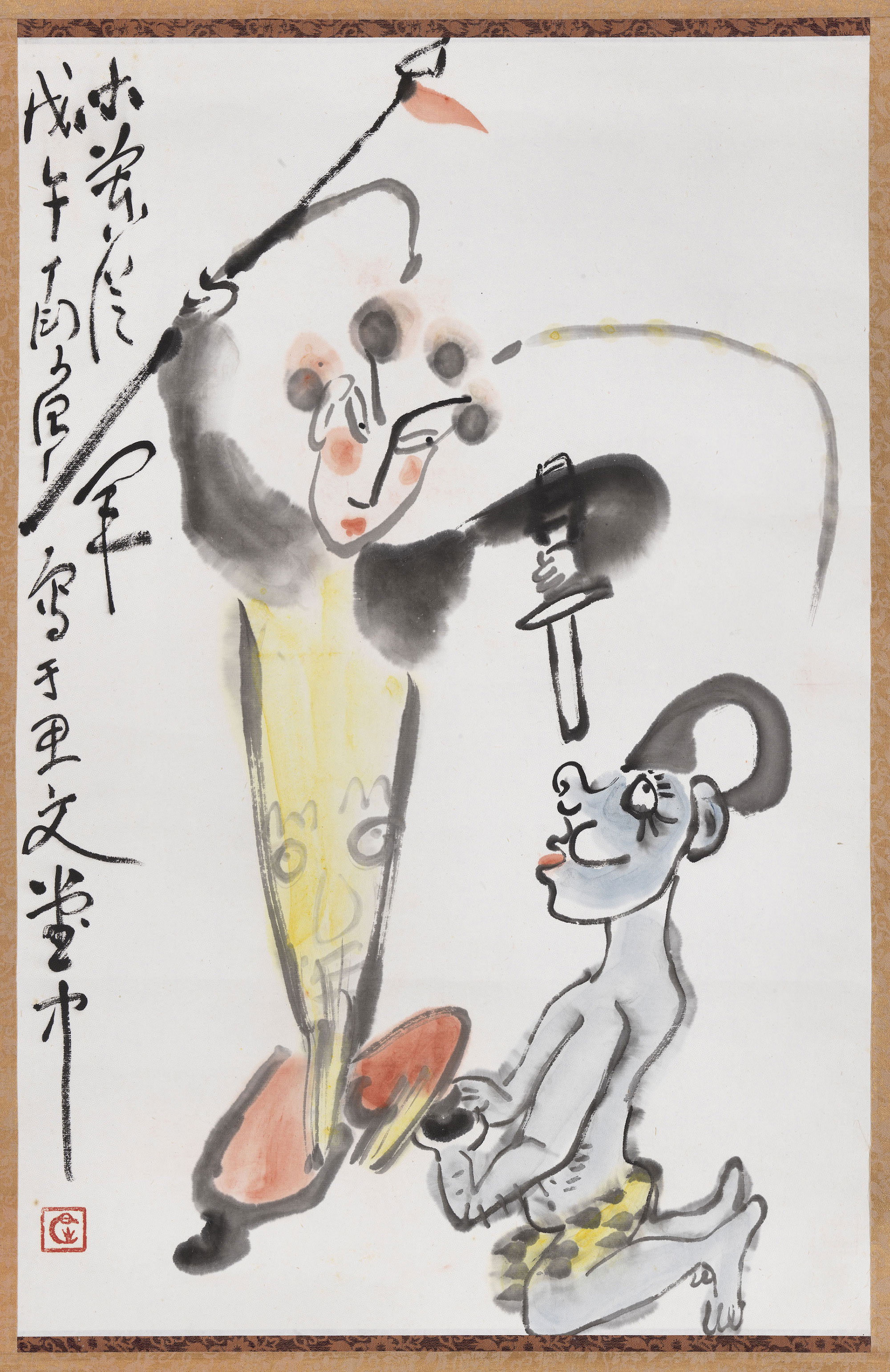

Mulan Becomes a Soldier

- Ting Yinyung (1902-1978), Republican period

Ting Yinyung, originally from Mouming in Guangdong, in his early years studied oil painting at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. In 1949 he went to Hong Kong to teach and actively experimented there with new techniques in Chinese painting.

This work features fluent and dripping-wet lines that depict a scene from the Chinese opera of Hua Mulan, which tells the story of a daughter who joins the army to take the place of her aging father. To the lower right is a soldier kneeling and shown mostly naked as he looks up at her, his submissive form a dramatic contrast with the overwhelming power and vitality of Mulan. Although the vivid lines and bright colors are very much in a personal manner, the work does not completely depart from the traditional use of brush and washes. This is the core of Ting's new exploration of ink and colors.

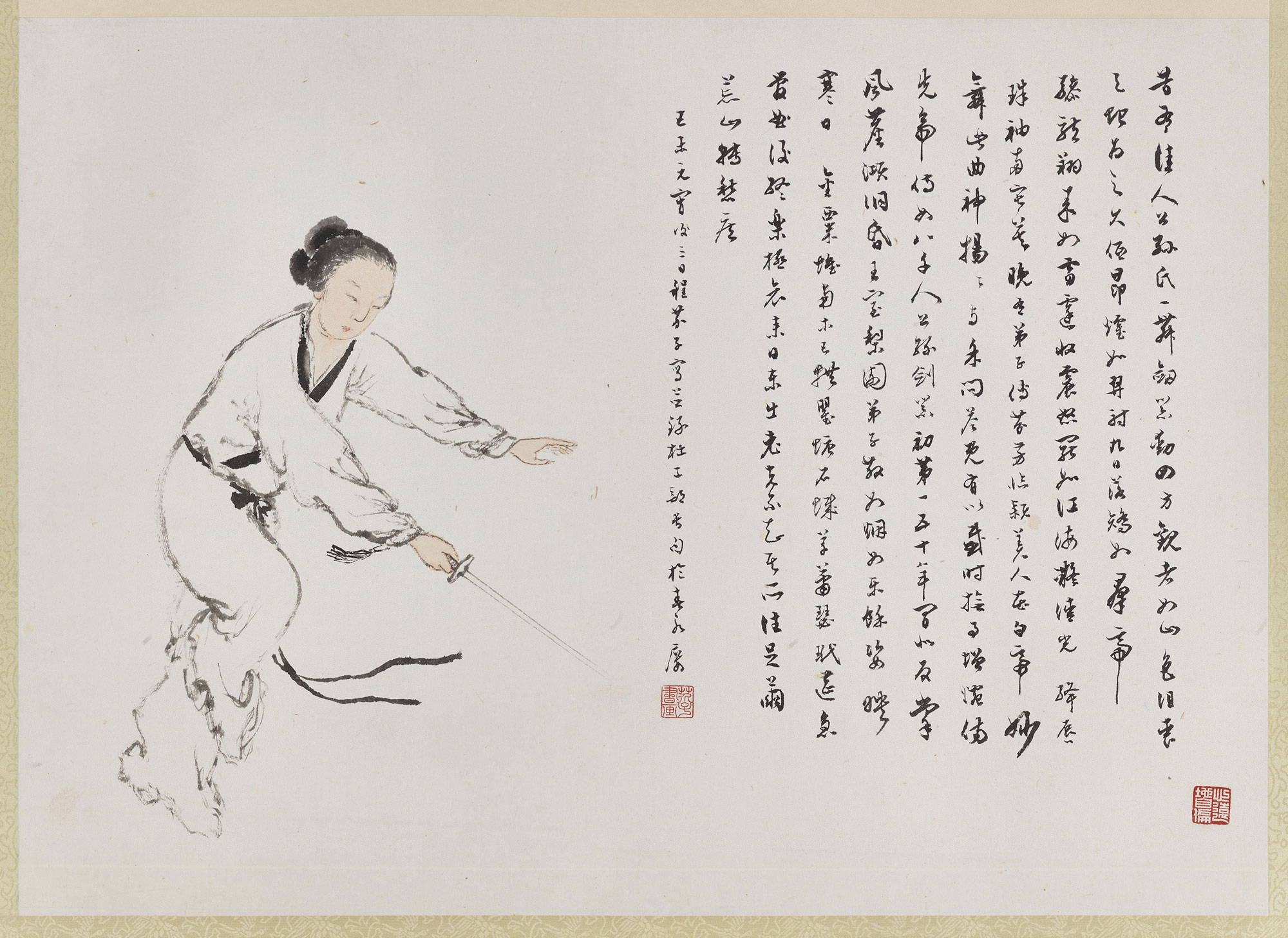

Lady Gongsun's Sword Dance

- Cheng Chieh-tzu (1910-1987), Republican period

Cheng Chieh-tzu, a native of Yuyao in Zhejiang, originally had the name Liushen but later went by his style name.

The scene depicted in this painting is the sword dance of Lady Gongsun. She was so famous throughout the Tang dynasty capital for her skill in sword dancing that many scholars wrote poems in praise of her. Reportedly the inspiration for the "wild cursive" script of the "Cursive Sage" eighth-century calligrapher Zhang Xu, her sword dance also influenced the depiction of figures by the "Painting Sage" Wu Daozi, indicating how much interaction there can be among the arts. Exactly what kind of instrument she used in her "sword dance" is still uncertain, but it is generally believed to have actually been a sword. There are, however, other theories that it may have been a kind of dance with banners or ribbons.