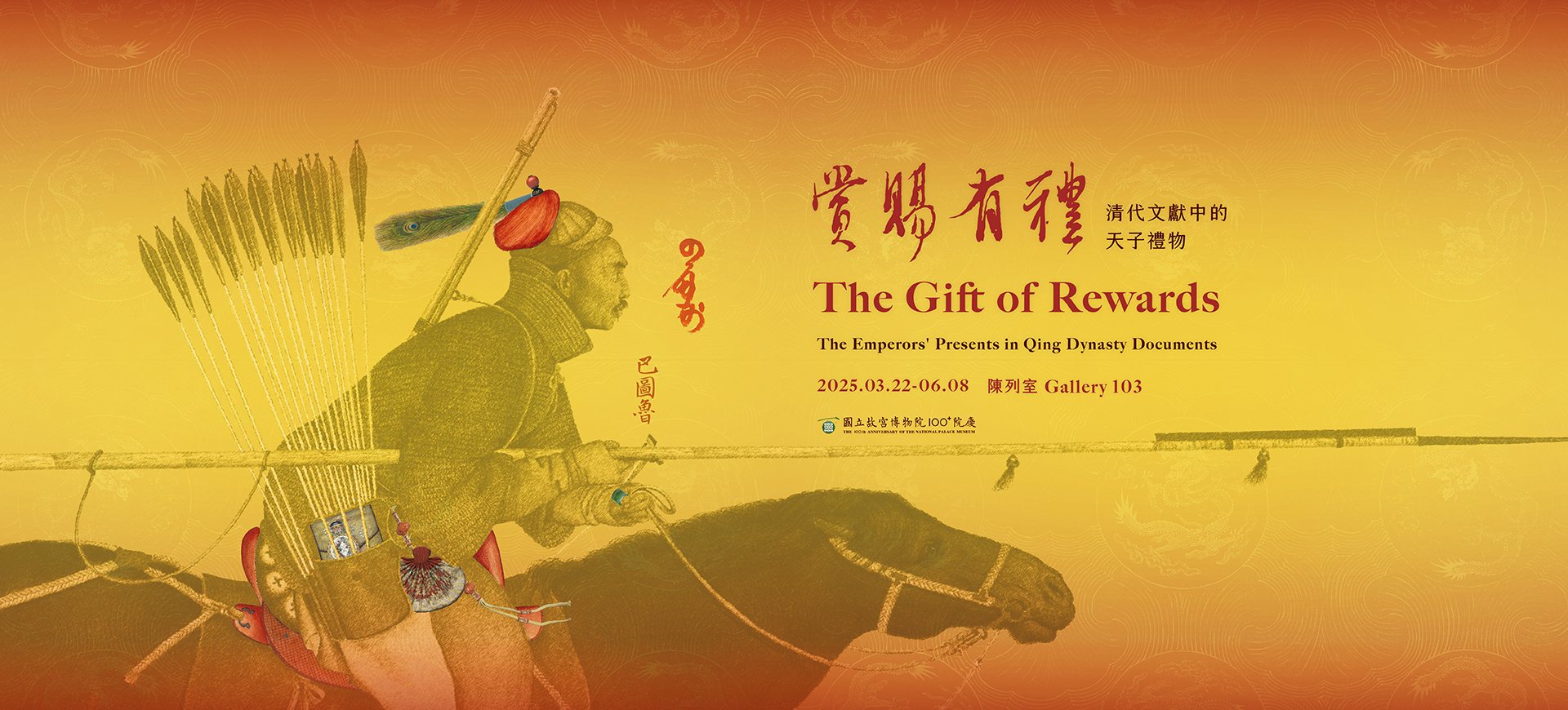

The Origins of Gift-Giving

Up to the time of the Qing Empire, both outside the Great Wall and at the imperial court, the awarding of gifts had never ceased. In the beginning, Nurhaci (1559-1626) mainly distributed gifts from the steppes where the Manchu had originated. And when the Qing imperial system was formally established, the types of rewards given became further diversified, ranging from the awarding of feathers for hats to the adding of titles and official rank as well as providing imperial food, vessels, books, and currency.

But have you ever thought about the background behind these rewards? And which institutions at the Qing court were the rewards related to? Let’s find out!

-

Balancing Benevolence and Authority: Nurhaci’s Reward Strategy

(Veritable Records of the Great Qing Emperor Gao, Taizu)

Large silk–bound Chinese edition

故官001536-001538According to Qing historical records, before entering the Central Plains, Nurhaci (1559–1626), the first khan of the Later Jin dynasty, had already established a military governance strategy based on the principle of “balancing benevolence and authority.” He sought to win over those who submitted through virtue, while dealing with dissenters through military force. As a result, in addition to his national policy of “generously rewarding meritorious officials,” he also provided substantial incentives to those who voluntarily defected from distant lands.

Historical records note that in March 1619, Nurhaci won a decisive victory against the Ming army in the Battle of Sarhu, his first major military confrontation with the Ming dynasty. By July of the same year, the Later Jin forces launched an attack on Kaiyuan, a key military stronghold in Liaodong, and quickly captured the town of Tieling, securing another triumph. During this time, Wang Yiping, a chiliarch of Kaiyuan, along with his troops, surrendered to Nurhaci.

Delighted by this development, Nurhaci generously rewarded Defense Officer Abutu, six chiliarchs, and other officers such as fortress defenders and centurions. Following Manchu traditions, the rewards included people, cattle, horses, sheep, camels, silver, coins, and cloth, with the quantities varying according to rank and status.

-

Reciprocal Gifts: Hong Taiji and the Grand Princess Consort of Khorchin

Daqing Taizong wenhuangdi Shilu

(Veritable Records of the Great Qing Emperor Wen, Taizong)

Small red silk–bound edition

故官001584-001589Hong Taiji (1592–1643) was the second khan of the Later Jin dynasty and the eighth son of Nurhaci. He is also the founding emperor of the Qing dynasty. Veritable Records of the Great Qing Emperor Wen, Taizong records Hong Taiji’s political activities before and after the establishment of the Qing dynasty, serving as an essential historical source for understanding early Qing governance.

The records note that on June 10, 1629, the Grand Princess Consort of Khorchin, mother of Empress Xiaoduanwen Borjigit Jerjer (1599–1649), paid Hong Taiji a visit. Hong Taiji, accompanied by the three major princes and numerous consorts, personally welcomed her.

The Grand Princess Consort brought lavish gifts including sable robes, marten covers, gold-topped marten hats, gold girdles (belts), handkerchiefs, complete matching clothing sets, court robes, boots, and gold-topped summer hats. In return, Hong Taiji presented her court robes and gold-topped summer hats and continued Nurhaci’s tradition of granting valuable animals such as camels, horses, cattle, and sheep as part of the Manchu custom of gifting precious items. -

Ranks and System of Imperial Bestowals in the Early Qing Dynasty

Guochao Gongshi

(Court history of Present Dynasty)

Compiled on imperial order by Yu Minzhong et al.

Court manuscript in red-lined columns, 1769, Qing dynasty

故觀003449Guochao Gongshi notes that as early as 1677, it was decreed that all imperial bestowals within the palace had to be promptly recorded by those handling them, clearly indicating the recipients’ names and the dates. Any false entries were subject to severe punishment.

Additionally, by 1744, imperial feasts and bestowals to Grand Secretaries were categorized into hierarchical ranks. For instance, officials put into important positions, such as Ortai and Zhang Tingyu, were classified as first-rank Grand Secretaries. For these Grand Secretaries, in addition to the standard rewards, they were given an extra ruyi scepter, a bolt of ning silk, and a jar of tea leaves. Furthermore, the quantity of bestowed books—165 copies of both The Complete Works of the Hall of Joy and Virtue (《樂善堂全集》) and Collected Essential Teachings on Human Nature and Principle (《性理精義》), taken from the Wuying Palace—indicates that there were a total of 165 attendees across the five ranks of Grand Secretaries present at the banquet.