Europe of the 16th to 18th centuries witnessed unprecedented progress of science and technology. The discovery of sea routes and the idea of the world as a globe encouraged missionaries to go to Asia to spread the gospel. Many well-educated missionaries from all over the world went to Qing courts during the reigns of Kangxi (1662-1722), Yongzheng (1723-1735) and Qianlong (1736-1795). They introduced mechanical clock, telescope and many other science instruments to China and worked as court artists. They promoted cultural exchanges between China and Europe directly or indirectly.

This gallery presents"Illustrations of Tribute Missions' Time Tunnel" to bring visitors to the past. Let's enter Giuseppe Castiglione's world and witness the new culture created by China's first attempt of modernization.

The"Illustrations of Tribute Missions" Time Tunnel

The"Illustrations of Tribute Missions' Time Tunnel" is inspired by the Illustrations of Tribute Missions of Xie Sui (Qing dynasty). This section presents worldwide tribute missions painted according to sketches supplied by local officers that included envoys from around the world including Russia, Japan, Vietnam, Poland, Britain, Netherlands, Portugal, Korea, and Taiwan. Upon entering the time tunnel, the international envoys would greet the visitors in their native language and guide them to experience the world of Giuseppe Castiglione.

The"Illustrations of Tribute Missions' Time Tunnel" is inspired by the Illustrations of Tribute Missions of Xie Sui (Qing dynasty). This section presents worldwide tribute missions painted according to sketches supplied by local officers that included envoys from around the world including Russia, Japan, Vietnam, Poland, Britain, Netherlands, Portugal, Korea, and Taiwan. Upon entering the time tunnel, the international envoys would greet the visitors in their native language and guide them to experience the world of Giuseppe Castiglione.

Artist

The National Palace Museum

Original work of Art

Illustrations of Tribute Missions by Xie Sui

A Brief History of the National Palace Museum

- The Establishment

-

- On October 10, 1925, the Forbidden City, at one time the Qing Empire’s palace, reorganized to become the National Palace Museum. Since then, relics owned by Emperors of the past millennium have become museum collections for everyone’s viewing pleasure.

- In 1933, to protect our national treasures from looting and destruction by Japanese invaders, the National Palace Museum packed most of the relics and transported them to southwestern China, behind the front line. This was the beginning of a long migration. Not until 1948 did the relics finally reach Taiwan. In 1965, the National Palace Museum was re-established in Waishuangxi, Taipei.

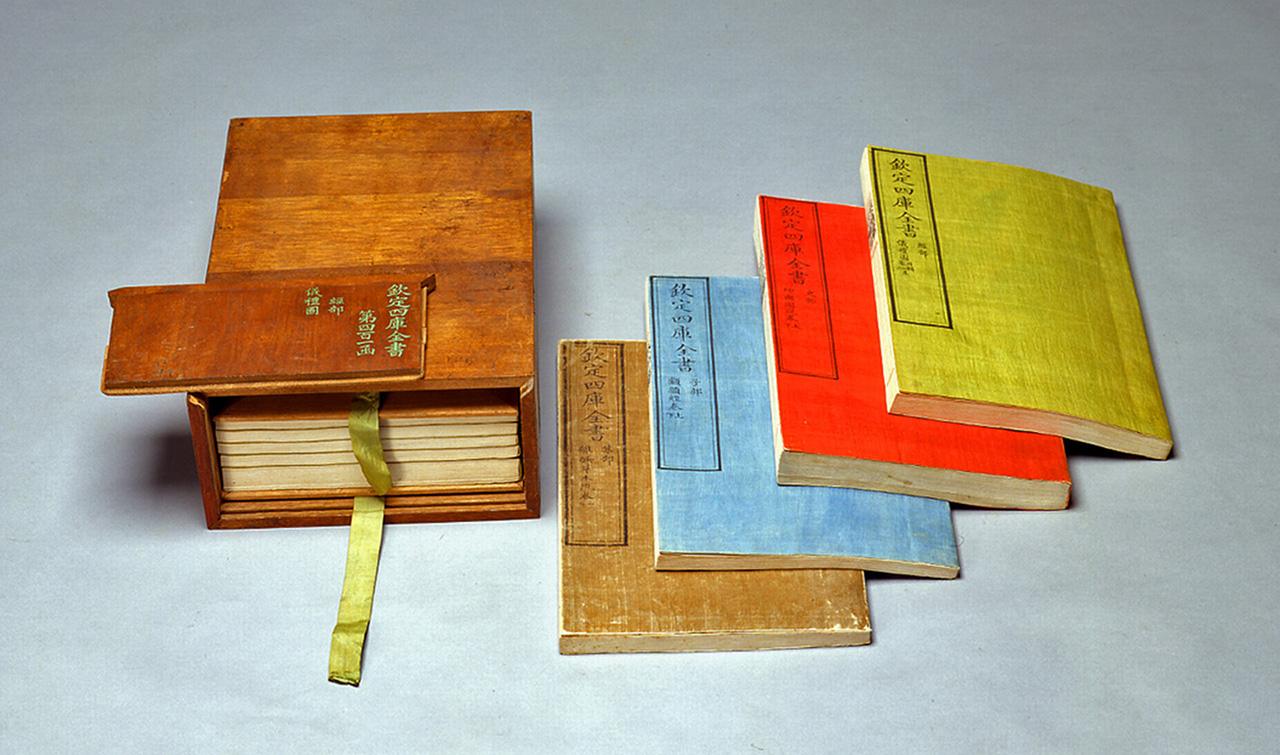

- The Collection

-

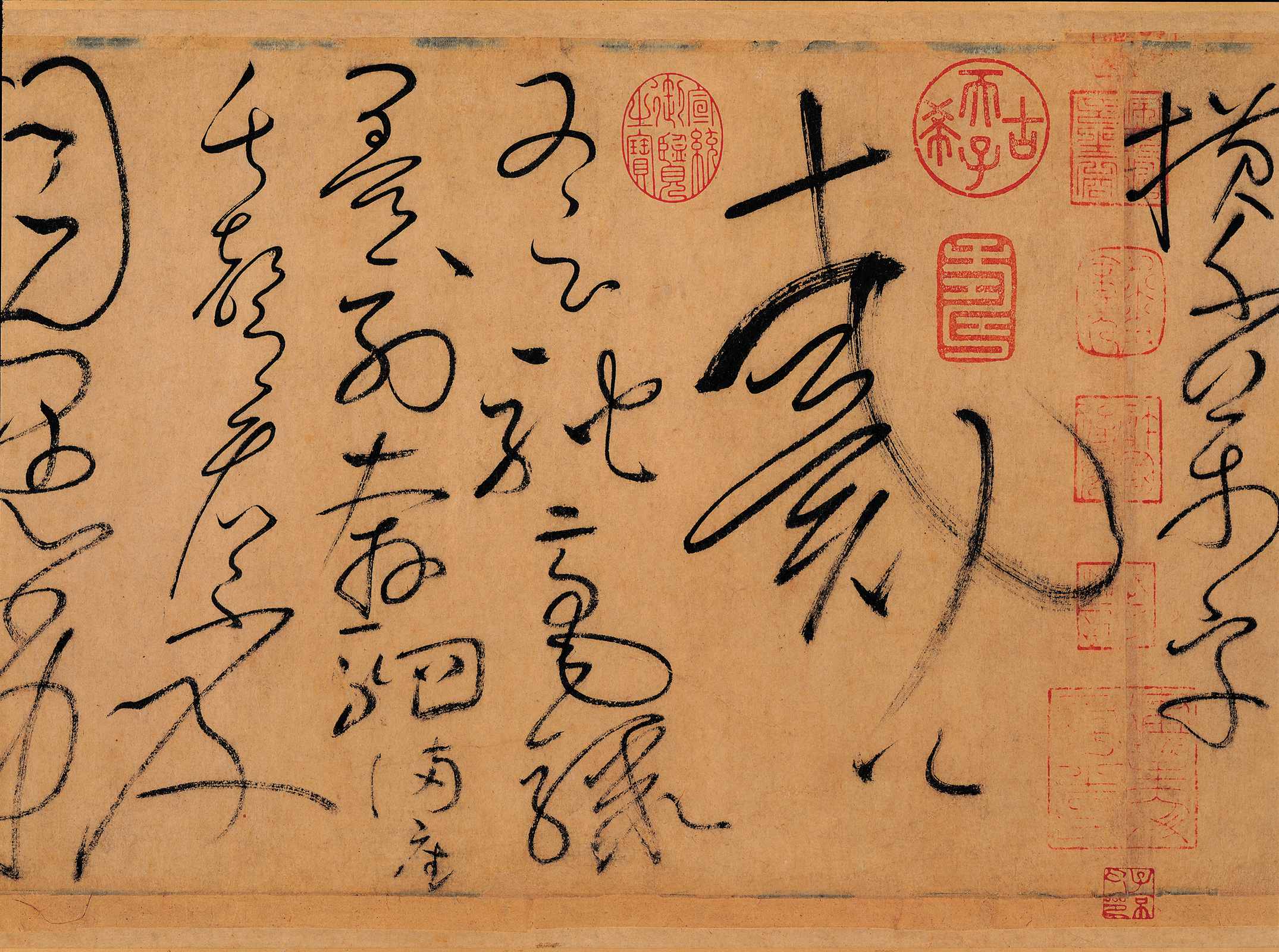

- The National Palace Museum has about 700,000 pieces of historical artifacts, including calligraphy, painting, ceramics, jade-ware, lacquerware, curio items, enamelware, fabrics, religious items, rare books and archives collected by the Qing Empire. In recent years, the National Palace Museum has begun to collect Asian relics. The National Palace Museum is a world-famous museum of palace artifacts from China.

On the Life of Giuseppe Castiglione, a Painter who has Served Three Chinese Emperors

- About Giuseppe Castiglione

-

- Born in Milan, Italy, Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) was a Jesuit lay brother. He served as a painter in China's imperial court from his arrival in 1715 to his death in 1766. He used his paintings to praise the beauty of God's creation in the hope that they would raise people's awareness to the existence of the Creator. It was his way to work for the Lord.

- Before entering China, Castiglione was already a talented and promising young painter. He developed a new painting style which is a combination of Chinese and European techniques after he entered China.

- Kangxi Reign(1715-1722)

-

- In 1714, Giuseppe Castiglione left Lisbon, Portugal and reached Beijing in the next year's winter. He was introduced to Emperor Kangxi by Matteo Ripa (1682-1745), another missionary, which marked the beginning of his service for the Qing Palace for the next 51 years.

- In 1721, Castiglione's painting skills was appreciated and approved by the Emperor.

- Yongzheng Reign(1723-1735)

-

-

When Emperor Yongzheng (1678-1735) ascended to the throne, he was pleased by Castiglione's painting skills and obedience.

It was helpful to his mission which was more difficult than ever. -

During the development of Castiglione's fusion style, Emperor Yongzheng advised and requested Castiglione to meet his standard.

His criticism mysteriously helped the forming of Castiglione's personal painting style.

-

When Emperor Yongzheng (1678-1735) ascended to the throne, he was pleased by Castiglione's painting skills and obedience.

- Qianlong Reign(1735-1766)

-

- Emperor Qianlong (1735-1766) was an art lover and he liked Castiglione's paintings since he was a prince. As he ascended to the throne, Castiglione became his favored chief court painter. Castiglione established a very good relationship with Emperor Qianlong and used this connection to protect other missionaries.

- In 1747, Castiglione was ordered to join the design of the European-styled buildings of the Old Summer Palace. He created a European-styled fountain with Chinese zodiac sign themed animal head bronze statutes. The Baroque-styled buildings with yellow glaze tile roofs marked the harmonization of the 18th century Chinese and European cultures. However, they were burned down by the Anglo-French forces in 1860.

- On July 16, 1766, Castiglione passed away at a venerable age of nearly eighty years. He served the Qing court for 51 years. Emperor Qianlong awarded him with the title of Vice Minister and gave a large amount He was buried in Beijing's missionary graveyard. Giuseppe Castiglione spent his whole life as a painter for the Qing court which left us with many masterpieces.

-

As to his career as a missionary, we may probably conclude it with a Chinese poem generally believed authored by him:

Enjoyed three Emperors' grace in this glorious age.

I am proud to serve the Qing Empire.

I mixed European techniques and Chinese fine line drawing.

Hoping my vivid still life can bring people to appreciate the creation.