Festival Celebrations

Traditional festivals reflected both ancestral wisdom and the pleasures of life. The Qingshigao (Draft History of Qing) records that in 1651 three occasions were designated as major festivals: New Year's Day, Winter Solstice, and Imperial Birthday Celebrations. The accompanying annual observances were the New Year's court assembly, winter solstice heaven-worship, and imperial birthday festivities, which followed historical and natural cycles, and demonstrated the Qing dynasty's adaptation to changing human activities and seasons, and the eternal connection between humans and nature.

Winter Solstice

- Abstinence plaque with turquoise inlay

- Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

The winter solstice sacrifice to Heaven was among the Qing dynasty's most solemn ceremonies, performed personally by the emperor. Before the ritual, both emperor and attending officials wore abstinence plaques on their chests as a mark of spiritual preparation and reverence.

This plaque features a gold filigree ground with the word "abstinence" in both Manchu and Chinese scripts inlaid in lapis lazuli. A subtle Eight Immortals pattern in turquoise frames the border, with cords threading through bat-shaped coral beads and pearls.

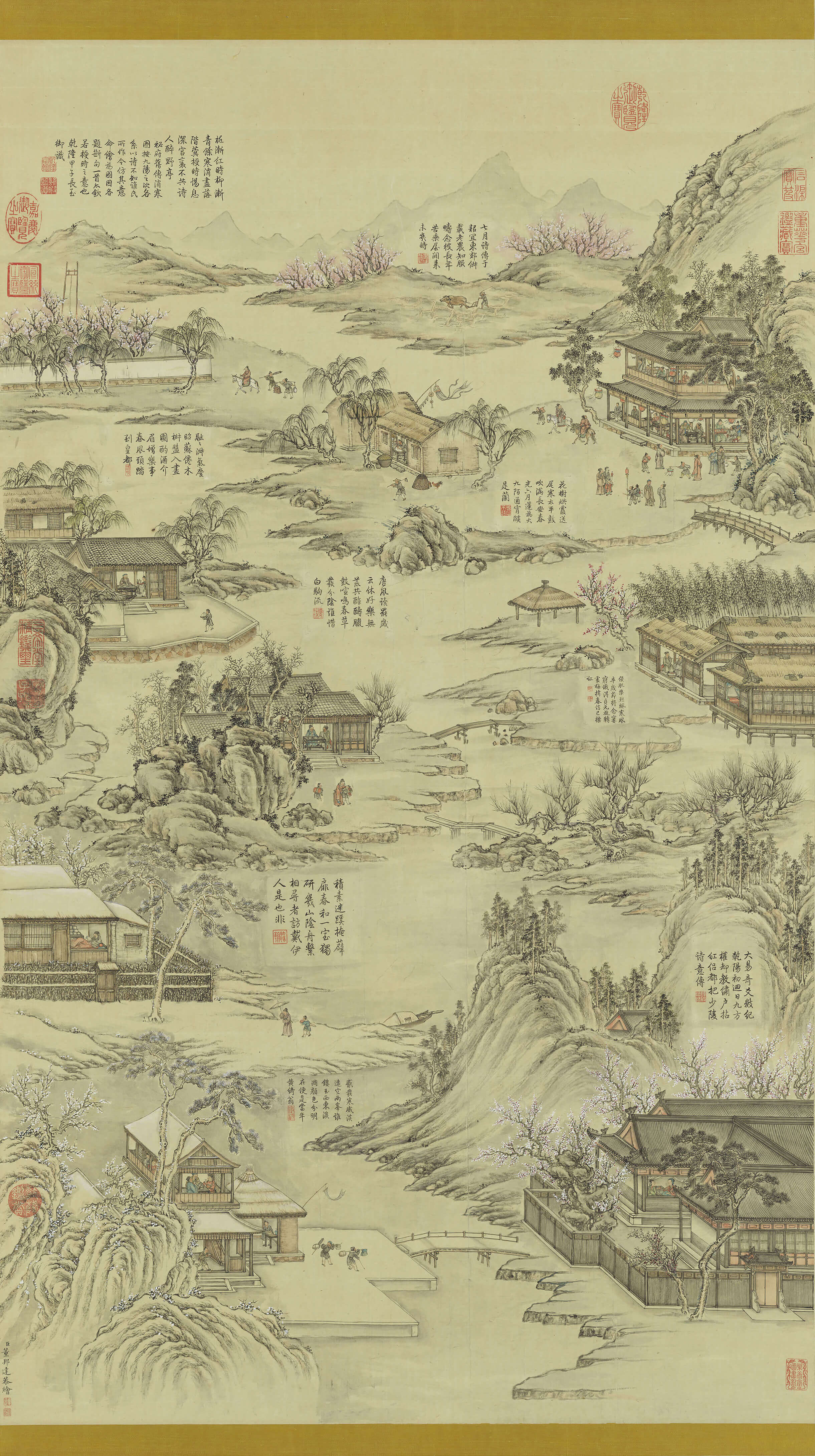

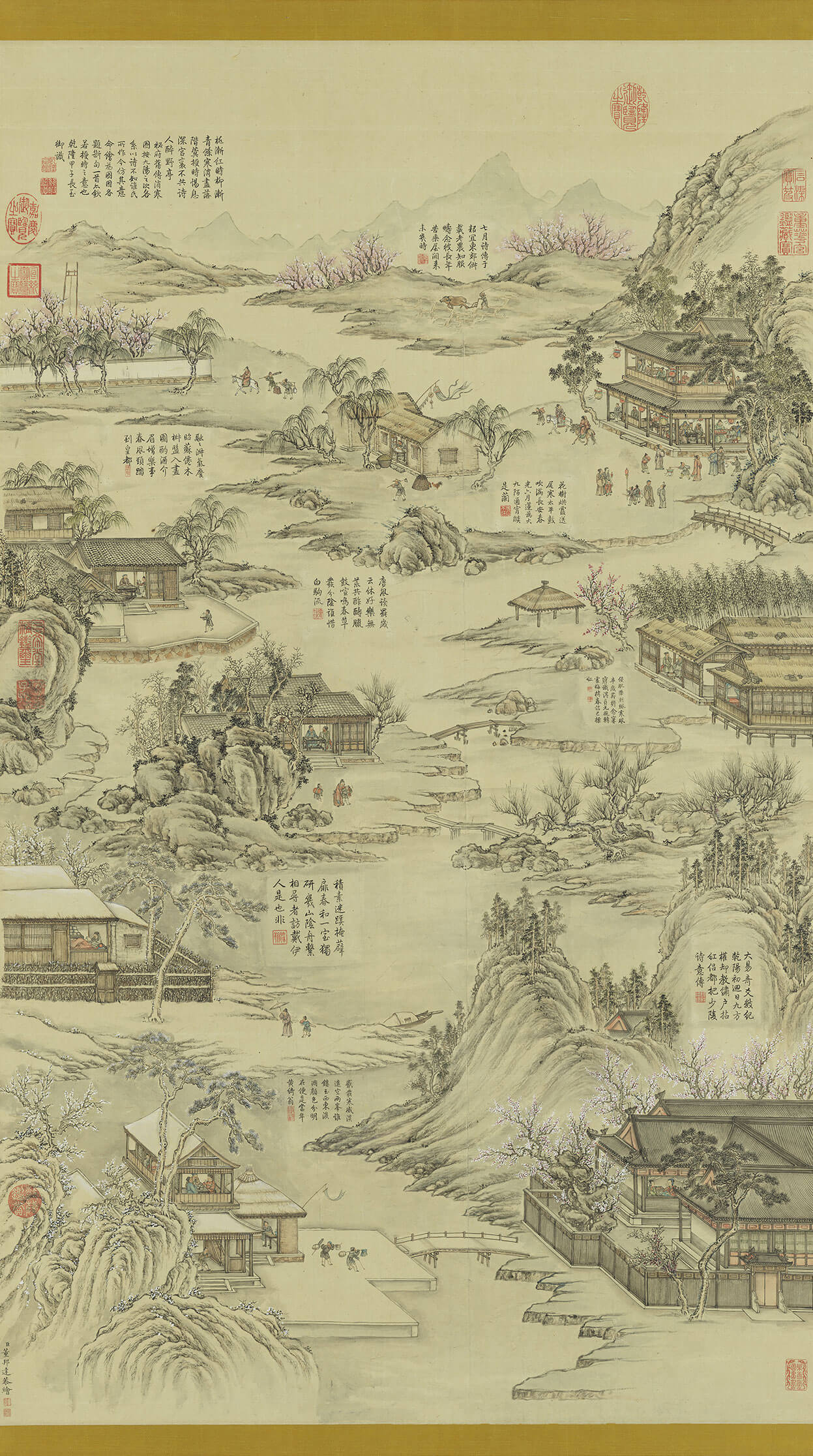

- Dispelling Winter's Cold

- Dong Bangda (?–1769)

- Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

According to Zhuozhong Zhi, an autobiographical memoir, the Imperial Household Department produced "Dispelling Winter's Cold" woodblock prints for court use during the Winter Solstice season. Court artist Dong Bangda (1699–1769) created this painting at the Qianlong Emperor's order, modeling it after earlier palace versions. The work features a river, viewed from above, snaking through the scene from front to back. Nine poems accompany scenes along the riverbank, celebrating winter's transformation into spring. The painting also embodies the imperial political ideal that virtue prevails as wickedness fades.