Transplanted into the Imperial Gardens

In order to furnish the emperors’ flower appreciation and palace decoration needs, each month barges traversed the canal connecting southern China to Beijing. These barges were responsible for delivering seasonal flowers and fabrics woven in the region south of the Yangtze River to the “Southern Gardens” in the Forbidden City. In addition to importing flowers and plants from southern China, the emperors would also have flowering plants from northern regions transplanted into the Forbidden City and the Chengde Mountain Resort. Specimens included the thousand-petal lotus from Aohan County in Inner Mongolia and the golden lotus (Trollius chinensis) from the high mountains of northern China. By observing the conditions in which imported flowers and plants arrived in the capital, the emperors were even able to indirectly ascertain the climate conditions of the faraway regions in which they originated.

These flowers and plants from the empire’s different latitudes and altitudes were meticulously cared for by imperial palace florists, who even set up greenhouses to protect the plants in wintertime or control the timing of their blossoming. These florists overcame the challenges of “non-acclimatized” plants, helping them to bloom ravishingly. These blossoms reflected that the palace florists successfully grasped the plants’ unique characteristics as well as the techniques needed to create hospitable environments for them.

Every month barges traversed the Grand Canal connecting Beijing to the province of Zhejiang, delivering textiles from the region south of the Yangtze river along with other items produced on imperial commission in southern China. These barges also carried potted in-season flowering plants to the imperial palaces, leading the Qing dynasty to establish the “Southern Gardens” in the Forbidden City as a place to raise and protect plants and flowers coming from all over the empire. In addition to employing floricultural specialists, the Southern Gardens also established greenhouses and even hothouses in which charcoal braziers were used to make sure that flowering plants from the south stayed warm. Blossoming potted plants were taken out and placed on display when they came into season so that they could be enjoyed by the imperial palaces’ denizens.

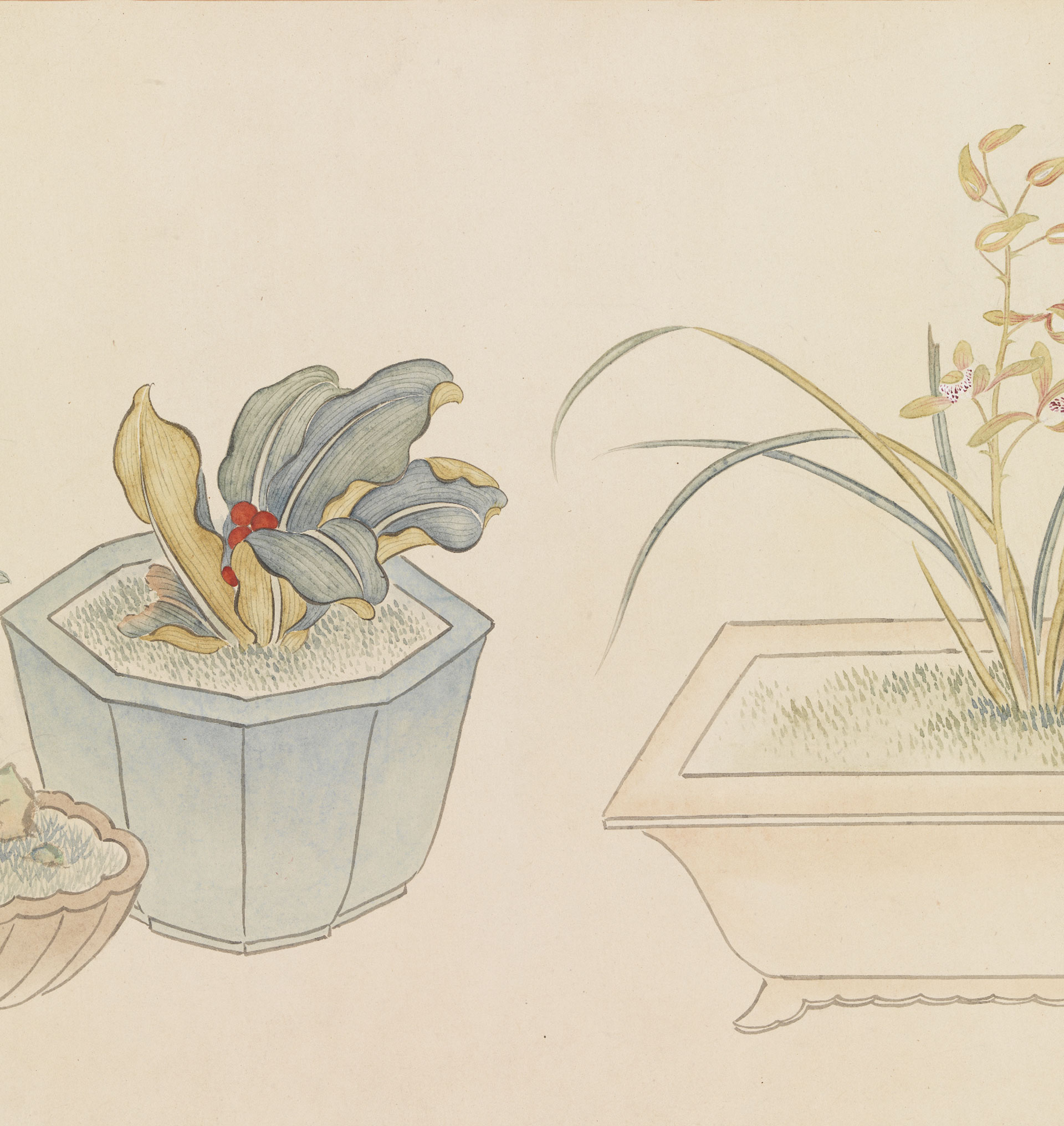

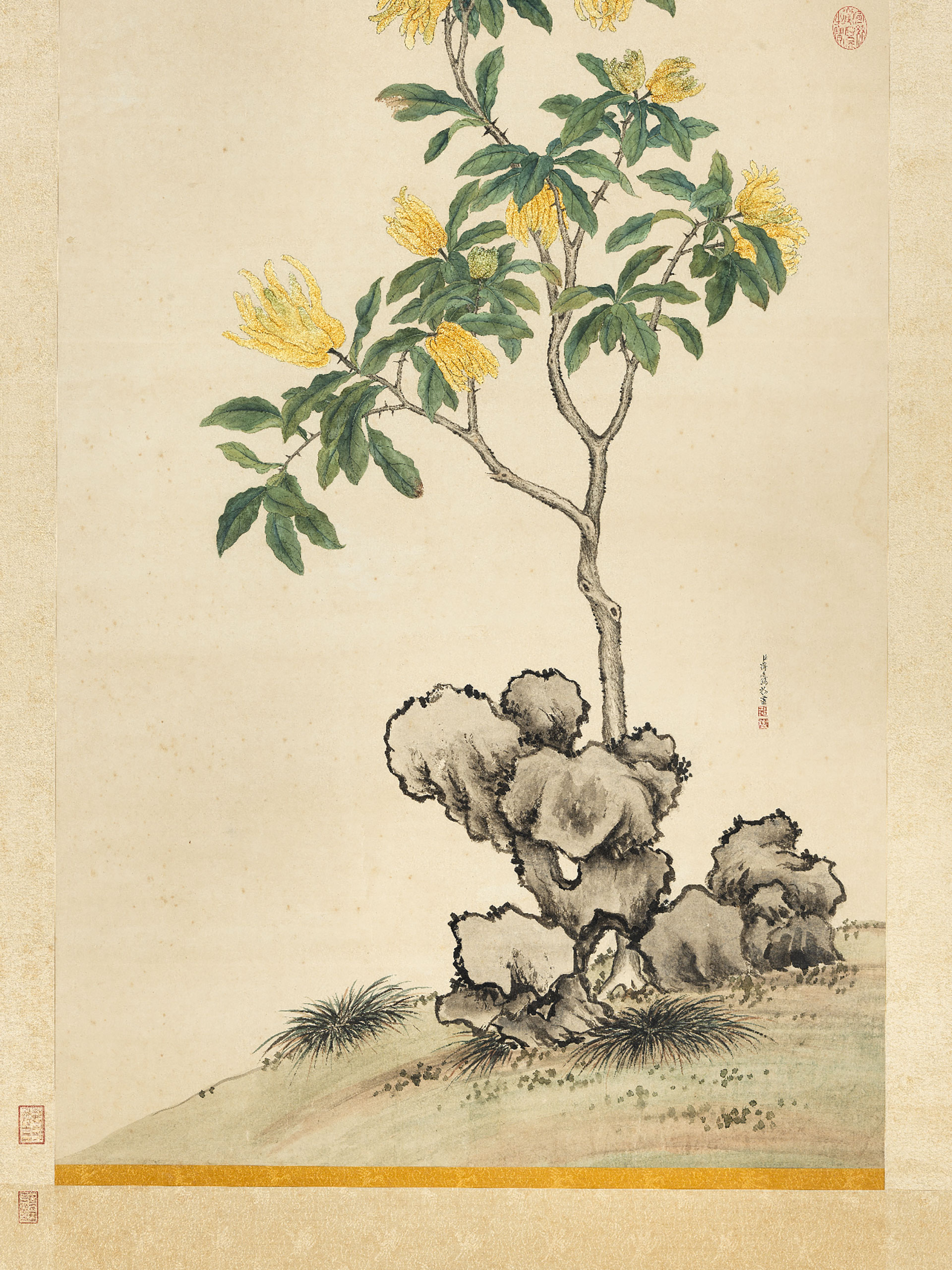

- Great Longevity

- Wang Chengpei, Qing dynasty

- Paper

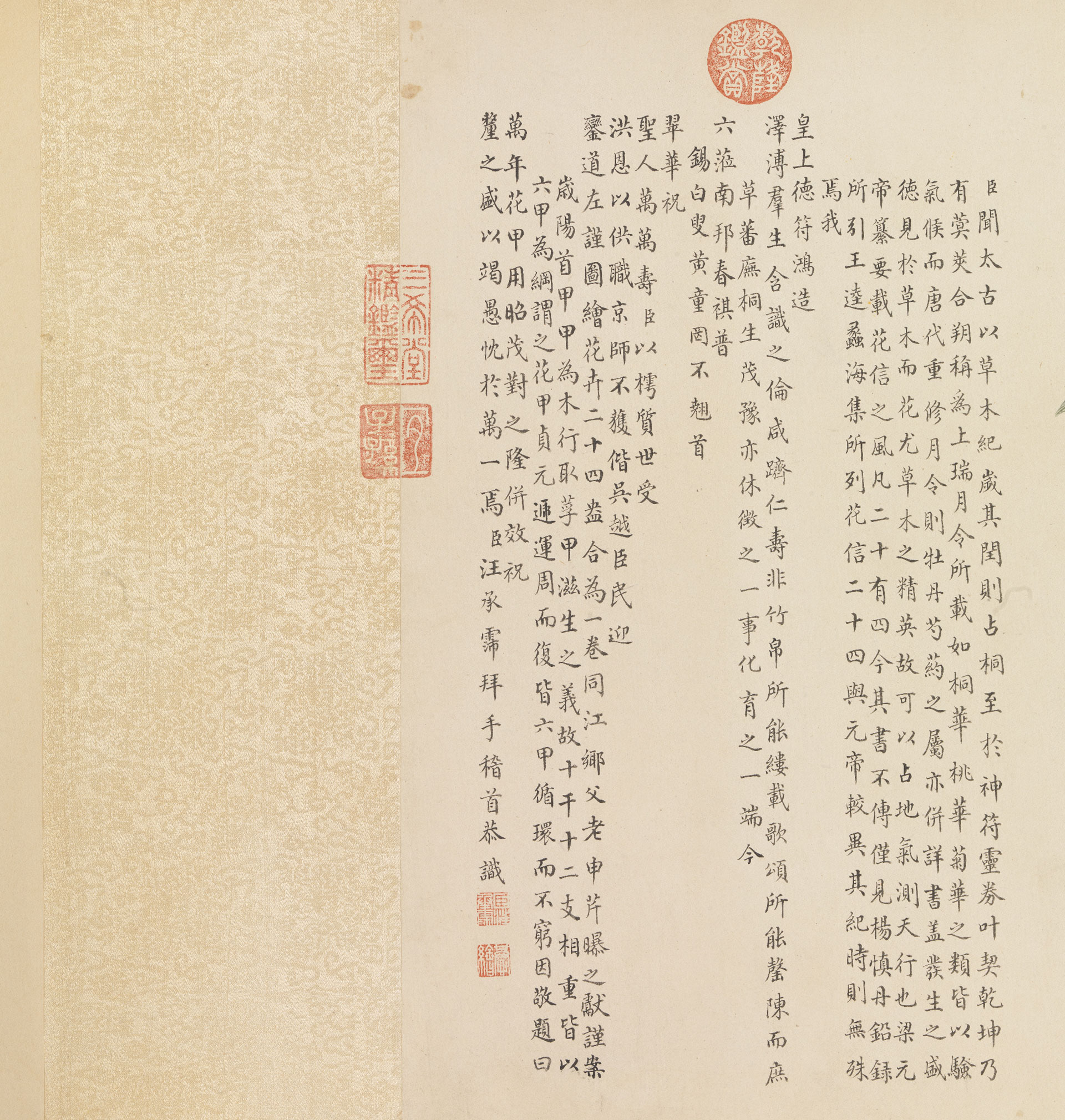

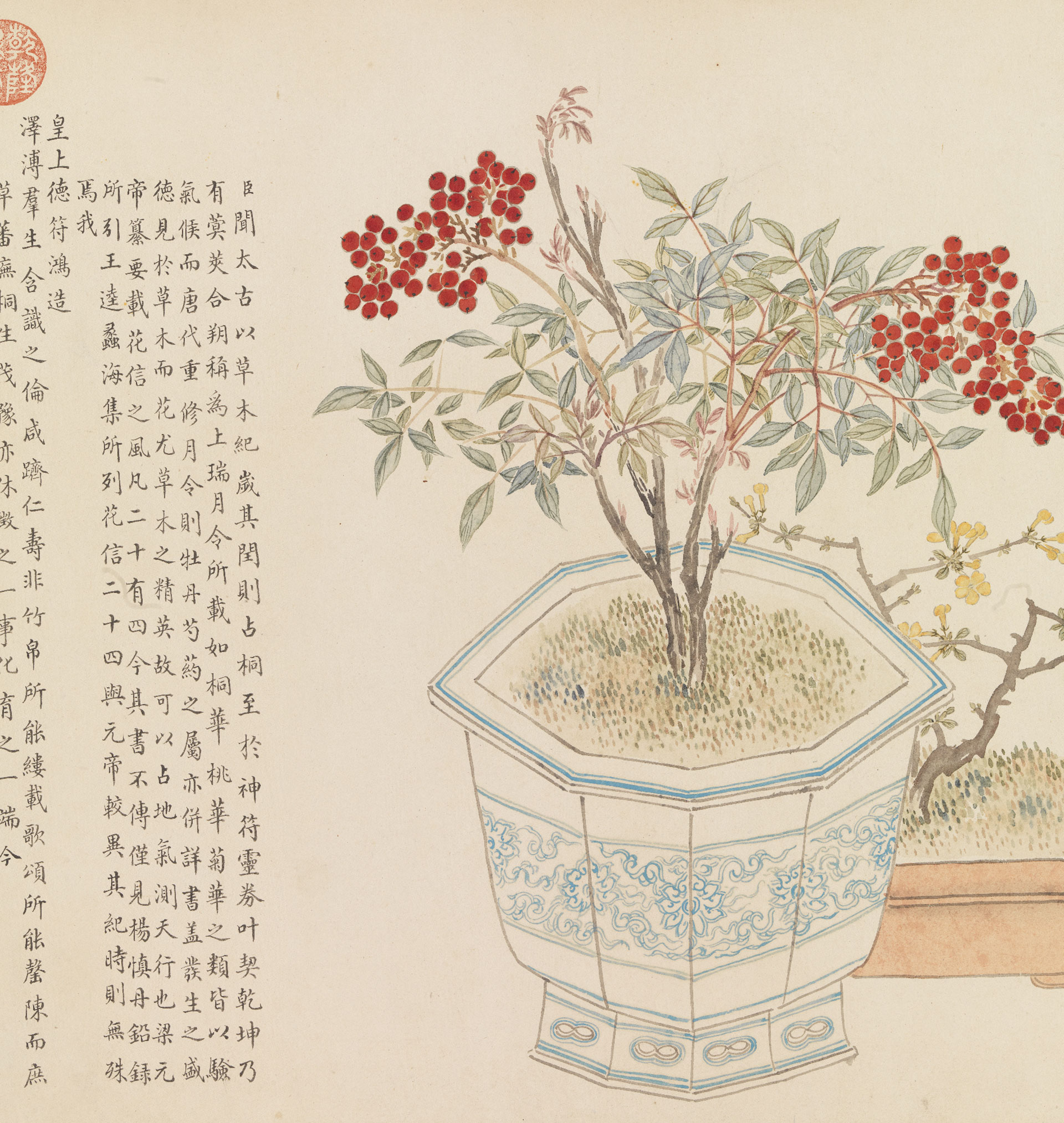

“Great Longevity,” which was painted by the scholar-attendant and painter Wang Chengpei (?-1805), is a depiction of twenty-four bonsai plants. It depicts a wide variety of flowering miniature trees planted in vessels made from porcelain, bronze, and even shellfish. In these vessels the bonsai trees are accompanied by miniature scholar’s stones, yielding so-called “natural scenery that fits in a flowerpot.” The painting’s portrayal of plants that come into bloom in each of the four seasons evokes the term “countless plants are blooming auspiciously,” a phrase that emblemizes an epoch of great peace and prosperity.

According to the colophon written at the end of this scroll, the paintings were completed in the forty-seventh year of Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1784), following the emperor’s sixth expedition to southern China. The emperor received the happy news that a great-grandson had been born to him while he was traveling—this birth made him a rare emperor who enjoyed having five generations of his family alive at the same time. The painting’s Chinese name is thus a portmanteau of one term meaning “may the Son of Heaven live for ten thousand years,” and another meaning “sixty years of age.” The auspicious title is a wish for the emperor to enjoy a long and healthy life.

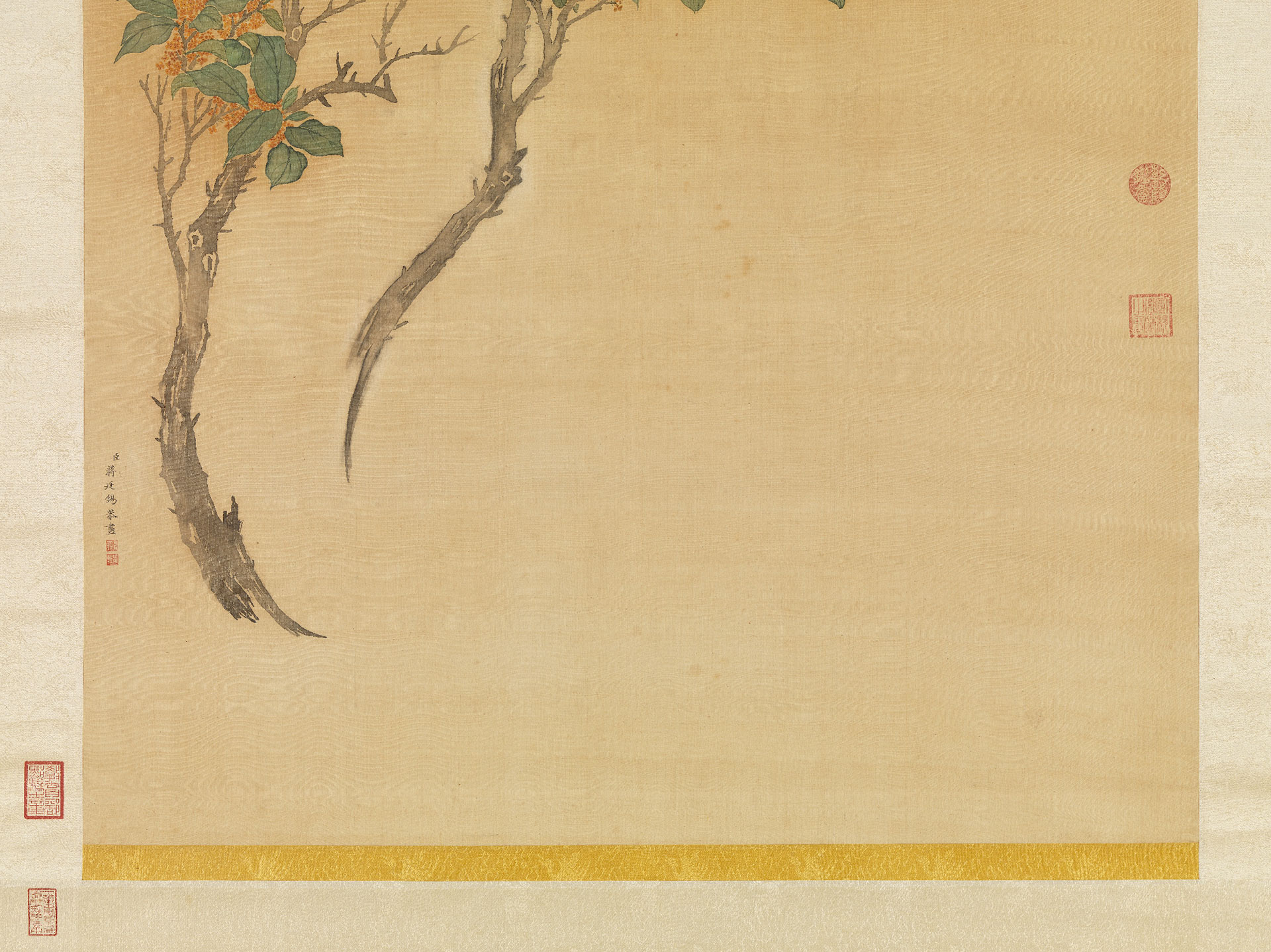

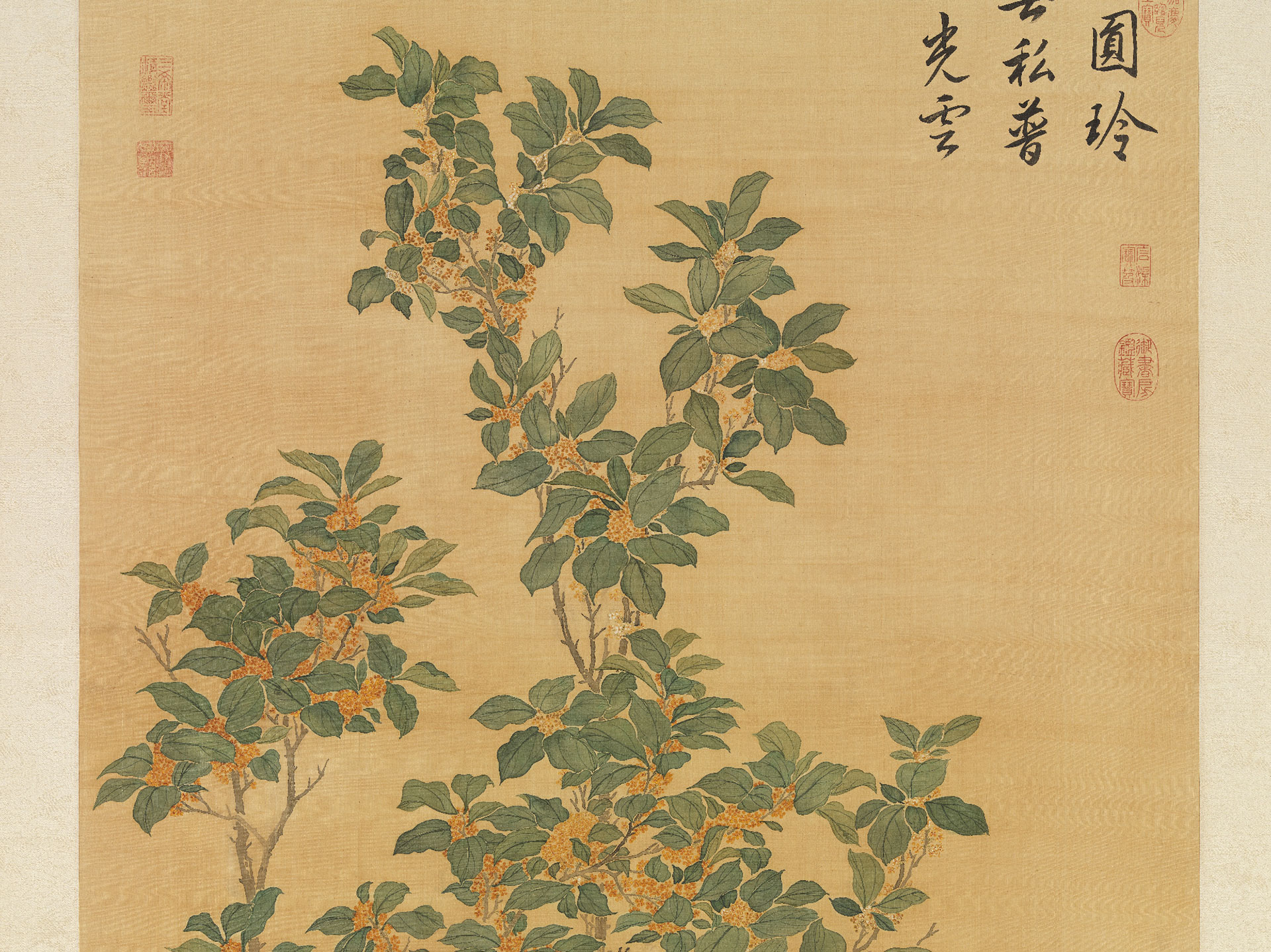

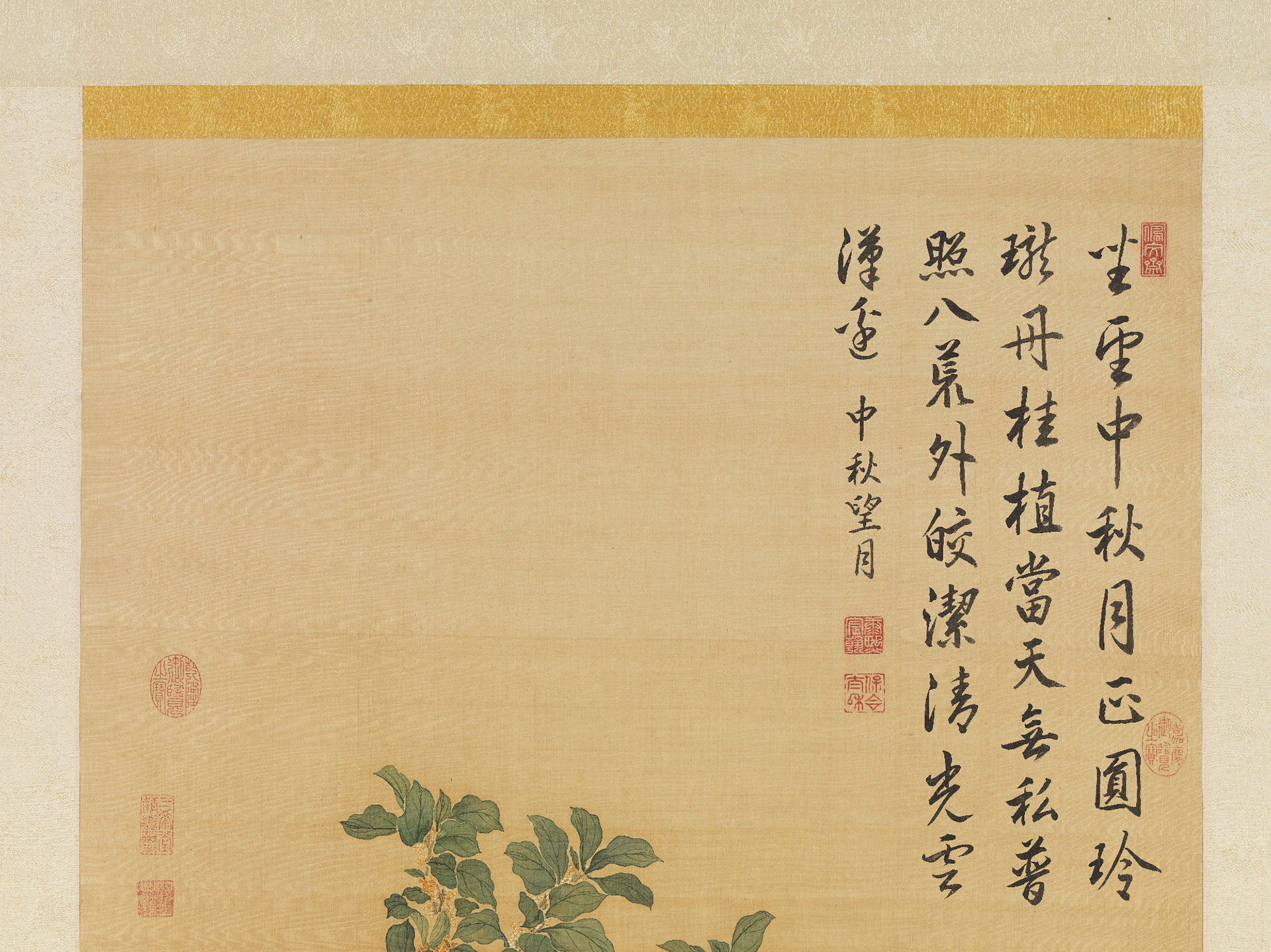

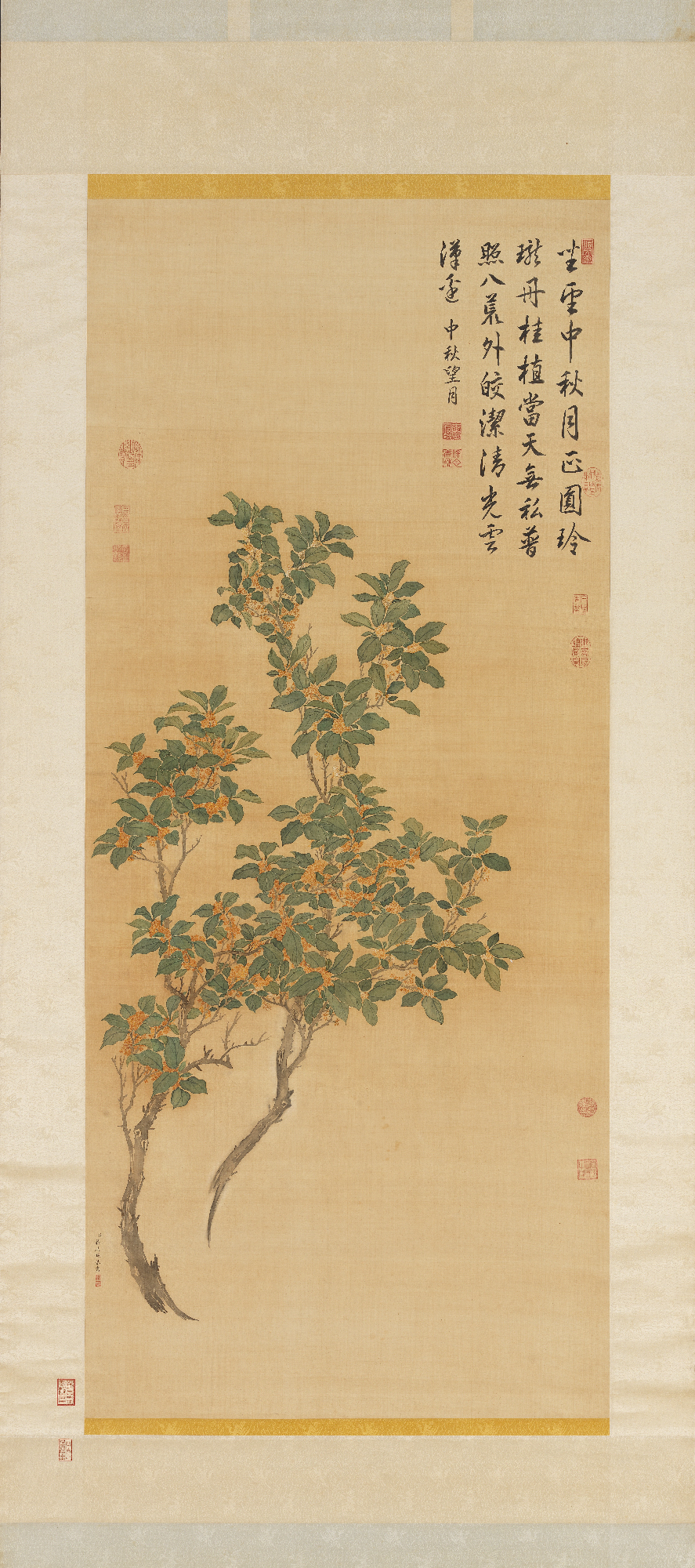

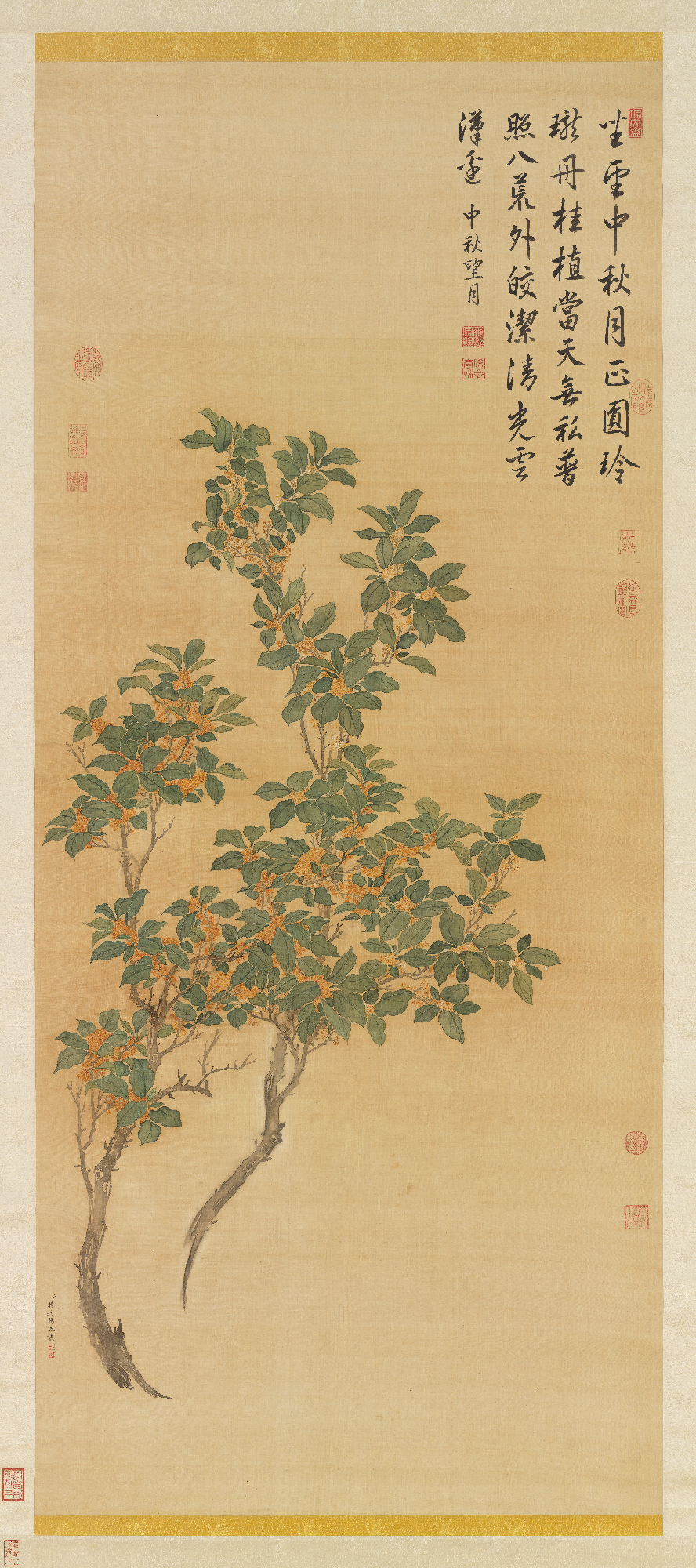

- Osmanthus Flowers

- Jiang Tingxi, Qing dynasty

- Silk

This painting is a detail of two branches from a flowering osmanthus tree, created by the scholar-attendant and painter Jiang Tingxi (1669-1732) using the unoutlined “boneless” (mogu) technique. Jiang intentionally left negative space where the two branches would have met and overlapped, and he also made clever use of washes to portray variations in the leaves’ colors, thereby giving the osmanthus a sense of translucency.

This undated work features a poem written by Emperor Kangxi (1654-1722) entitled “Gazing at the Moon in Mid-Autumn,” in which Kangxi expresses his reflections on enjoying the orange osmanthus (Osmanthus fragrans var. aurantiacus) flowers that come into bloom around the Mid-Autumn Festival. As Emperor Kangxi passed most Mid-Autumn Festivals at the Chengde Mountain Retreat in his later years, the poem likely memorializes one of his experiences appreciating osmanthus flowers in Rehe, where the retreat was located. The Imperially Commissioned Gazetteer of Rehe Province records that the potted osmanthus trees in the Chengde Mountain Retreat were all brought from southern China. This poem’s comment that the moon selflessly shines even on those who are far from home might allude to this point.

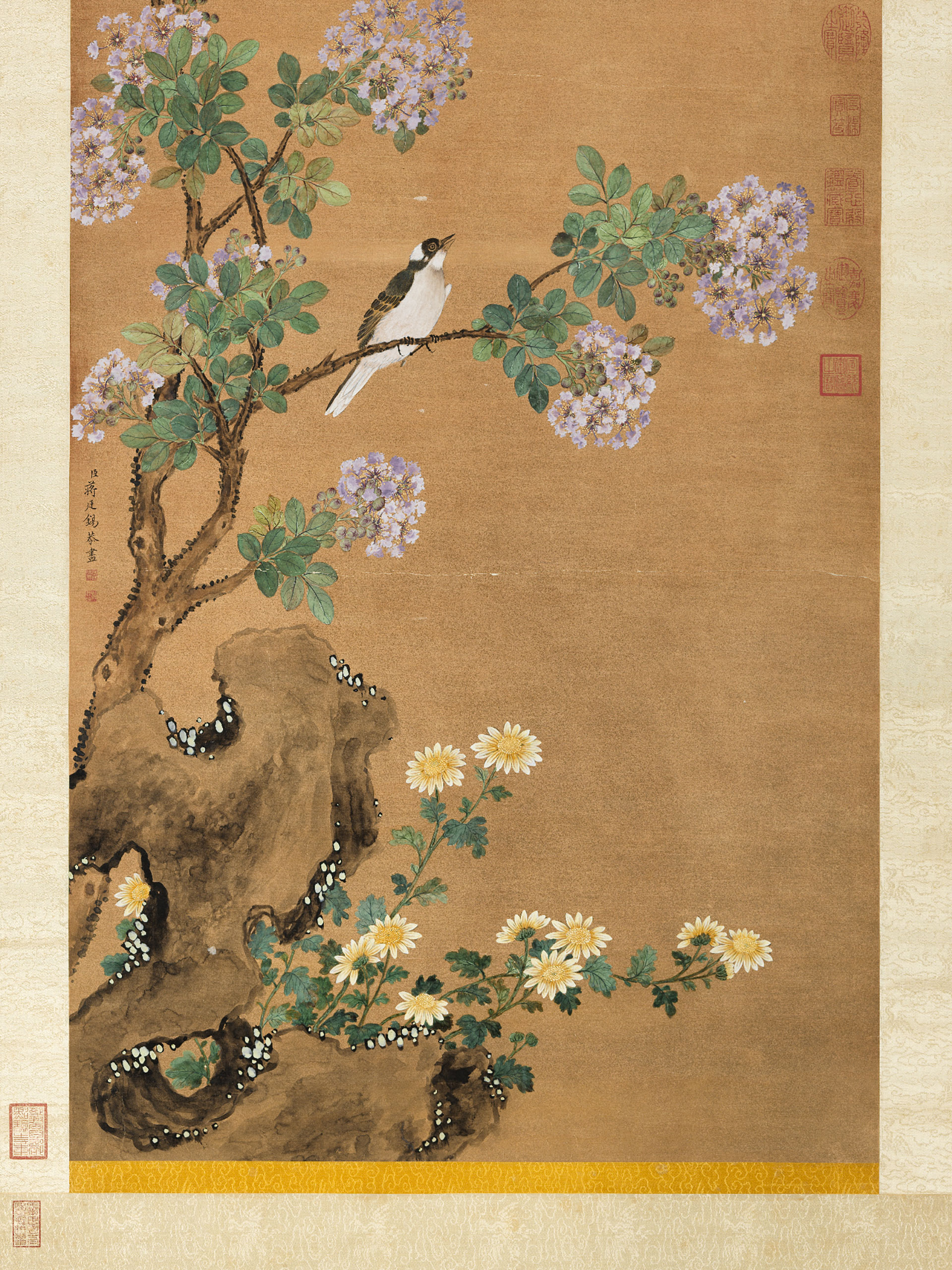

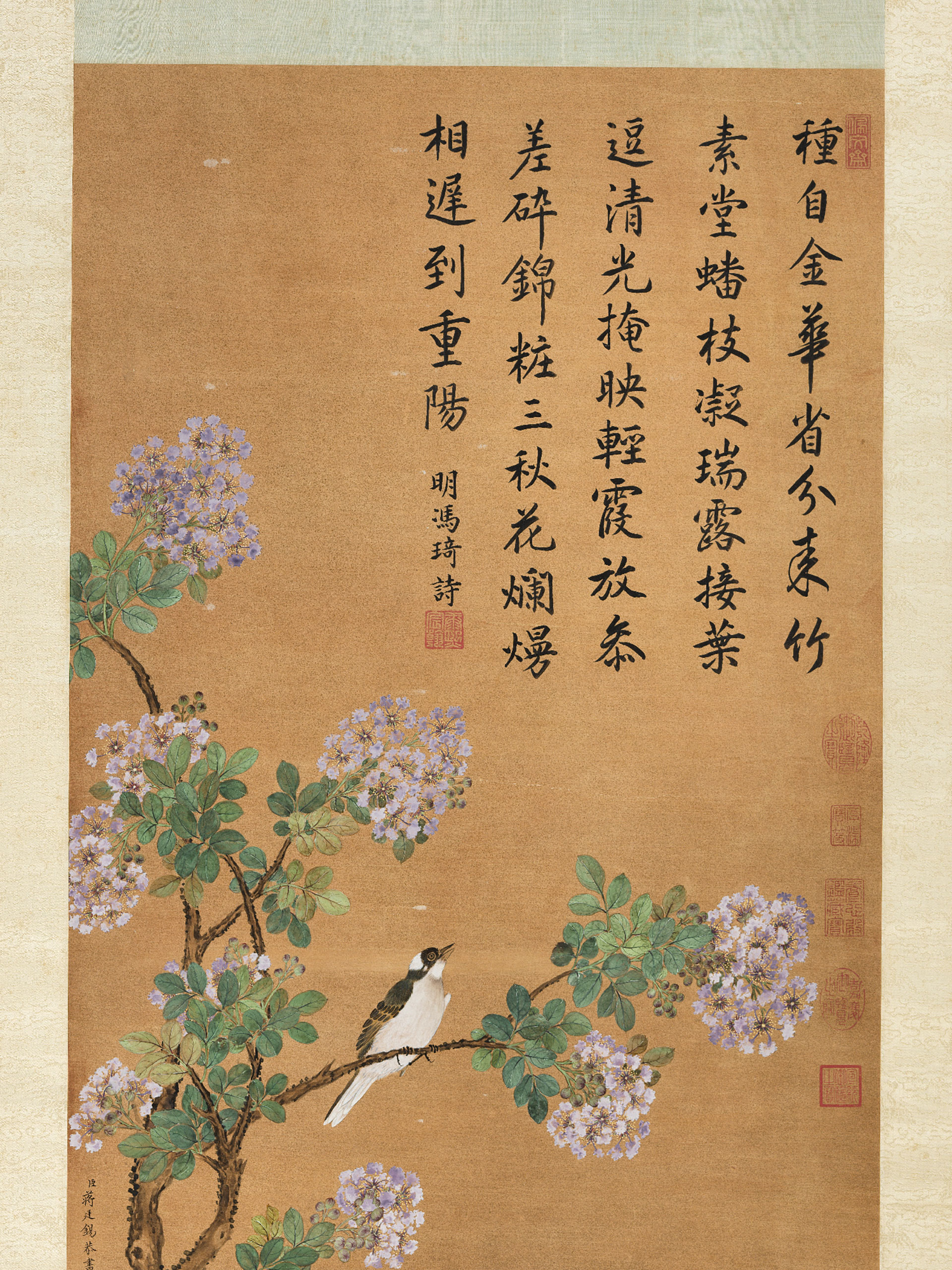

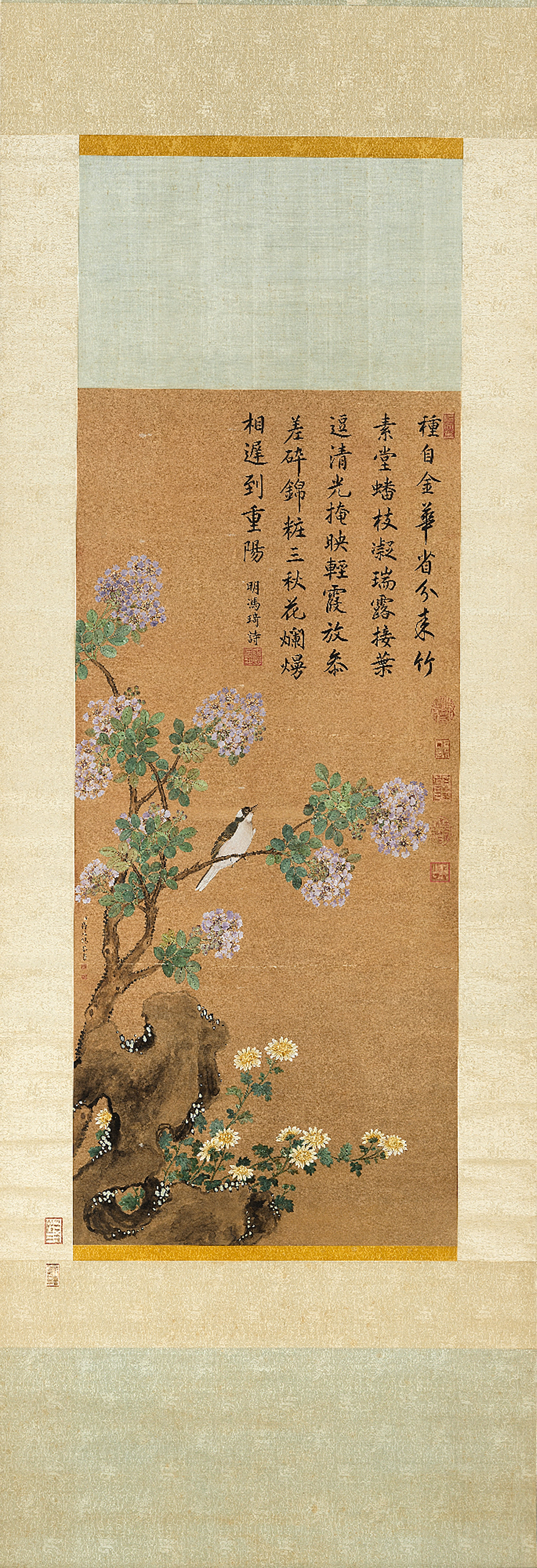

- Flowers-and-birds Painting from Life

- Jiang Tingxi, Qing dynasty

- Paper

This painting depicts crape myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica) and chrysanthemum flowers in full bloom, with a light-vented bulbul (Pycnonotus sinensis) perched near the end of one of its branches, the bird’s head tilted back in song. The tree’s form is set off by the scholar’s stone beneath it—the stone’s presence subtly suggests that this painting portrays the manmade scenery of a garden setting.

This piece was painted on gold dusted paper; aside from the tree and the stone, the rest of its elements were painted with applications of quite opaque colors. The calligraphic inscription in the upper right is Ming dynasty scholar-official Feng Qi’s (1558-1603) poem “Crape Myrtle,” written in Emperor Kangxi’s hand. The poem mentions how a crape myrtle tree from the southern Chinese province of Zhejiang was replanted in Feng’s studio. Kangxi’s choice to transcribe this poem perhaps indicates that the plant in this painting was similarly replanted in the imperial palaces.

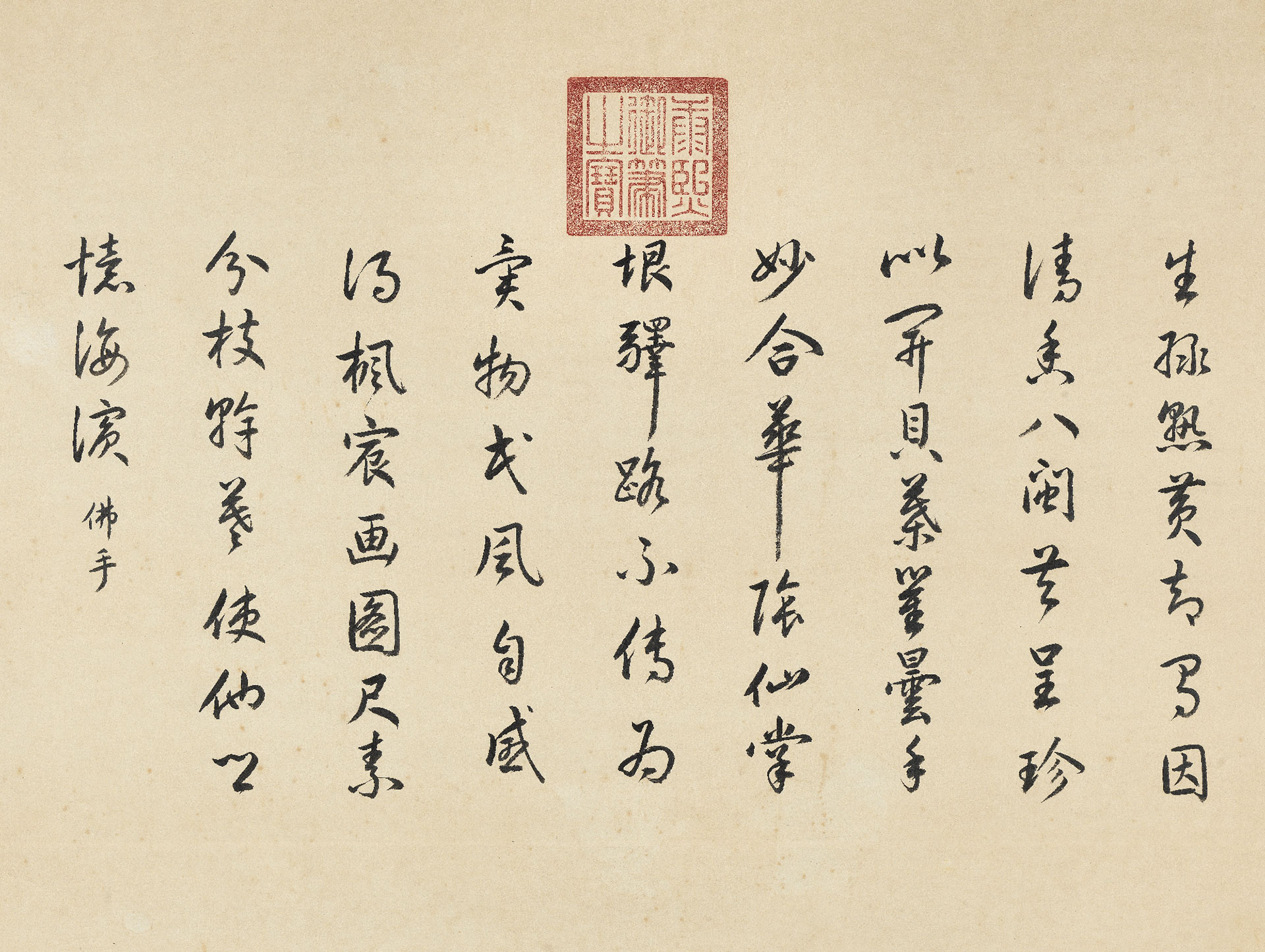

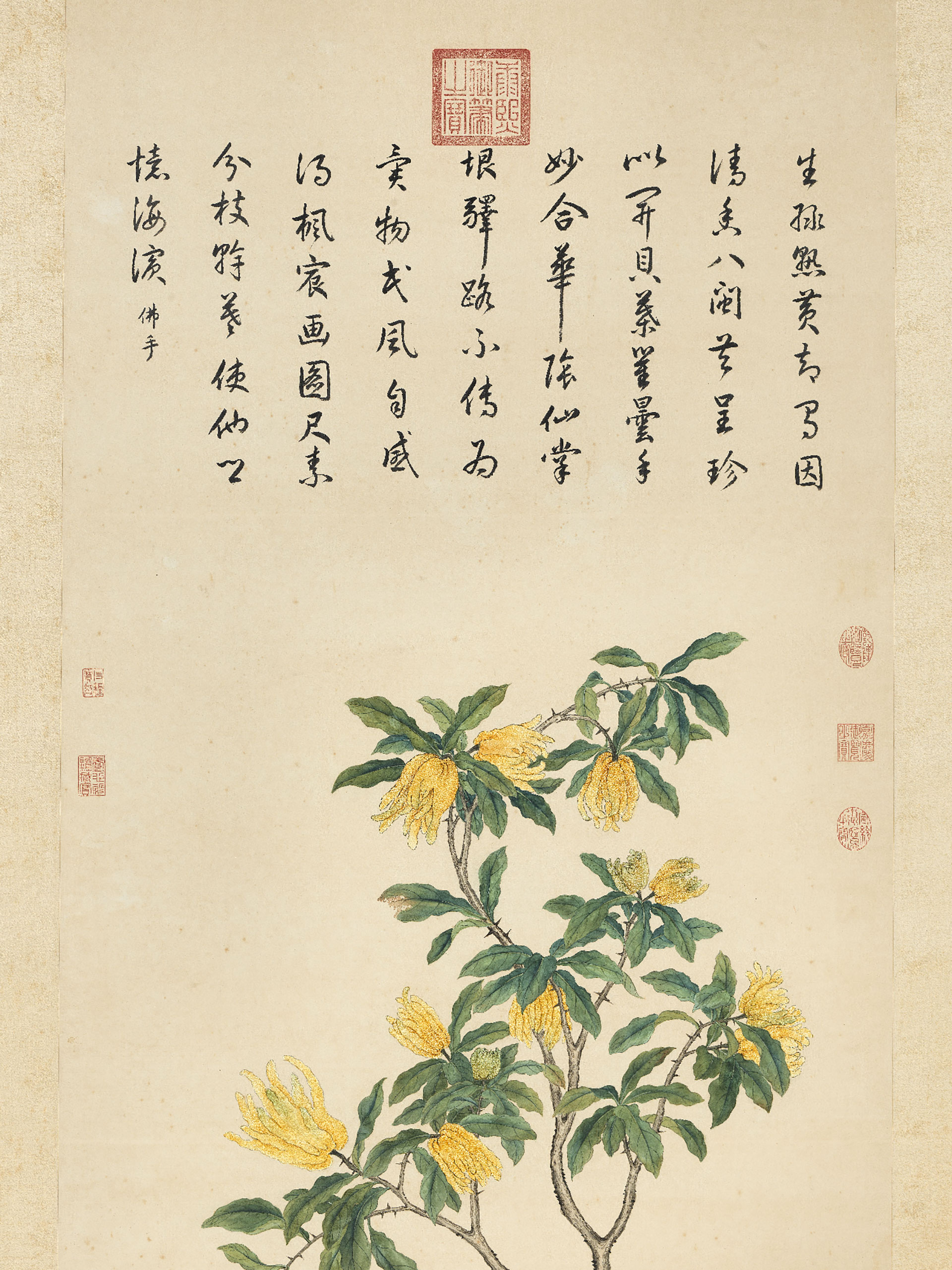

- Buddha's Hand Citron Painting from Life

- Jiang Tingxi, Qing dynasty

- Silk

This painting depicts a buddha’s hand citron tree growing on a hillside, where is has produced rough-skinned fruits named for the way their tendrils can resemble the hands on some Buddhist sculptures. In a realistic touch, the tree’s sharp thorns can be seen grown from its branches and trunk. The tree is set off by a scholar’s stone directly beneath it—its presence is a hint that this tree was planted by hand in a garden. In the painting’s upper region appears a poem entitled “Buddha’s Hands,” written by the Kangxi Emperor (1654-1722) in his fifty-fourth year on the throne (1715). The poem mentions how this Buddha’s hand tree was originally offered to the Qing court as tribute by denizens of Bamin (present day Fujian province), and describes how it was replanted in an imperial palace garden.

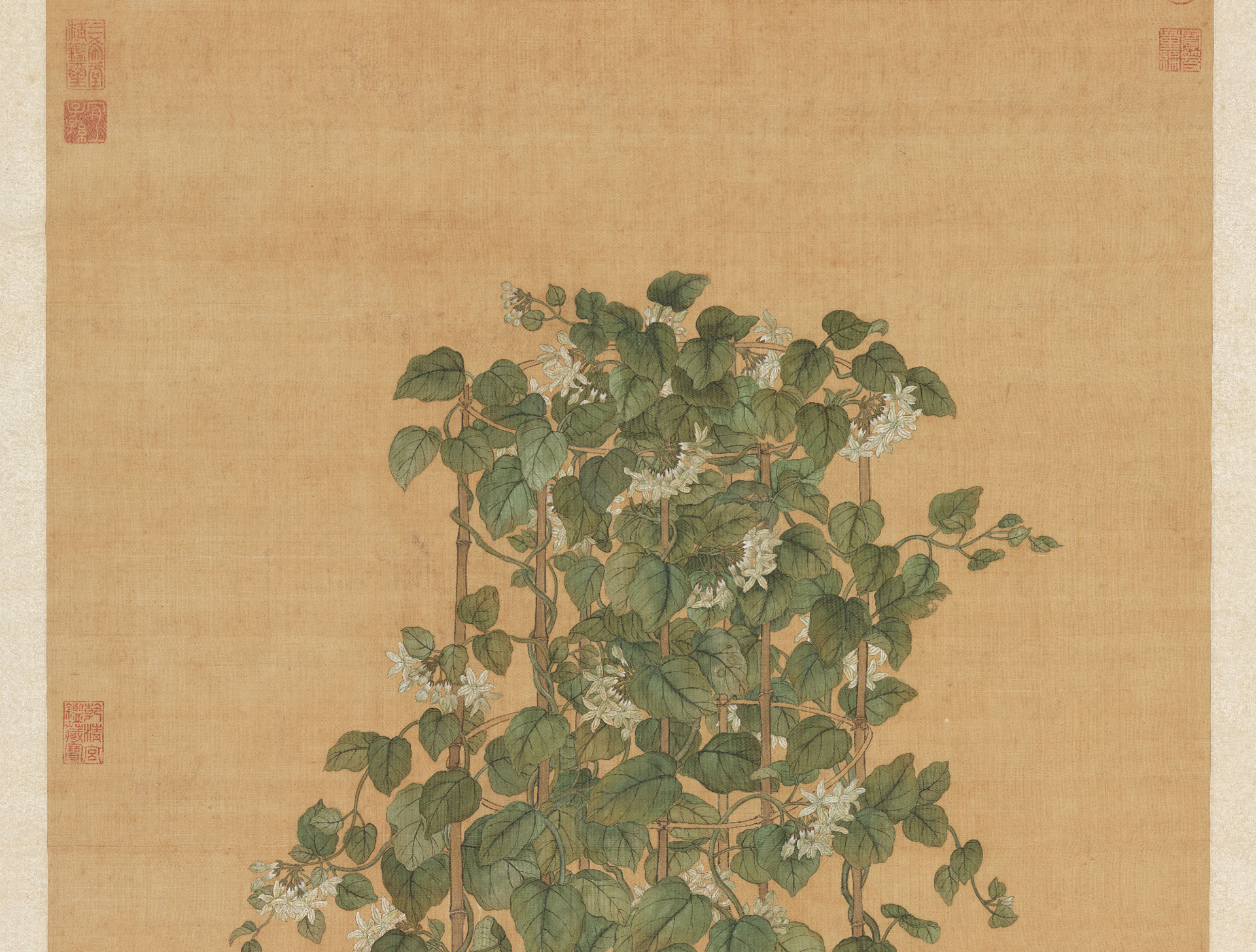

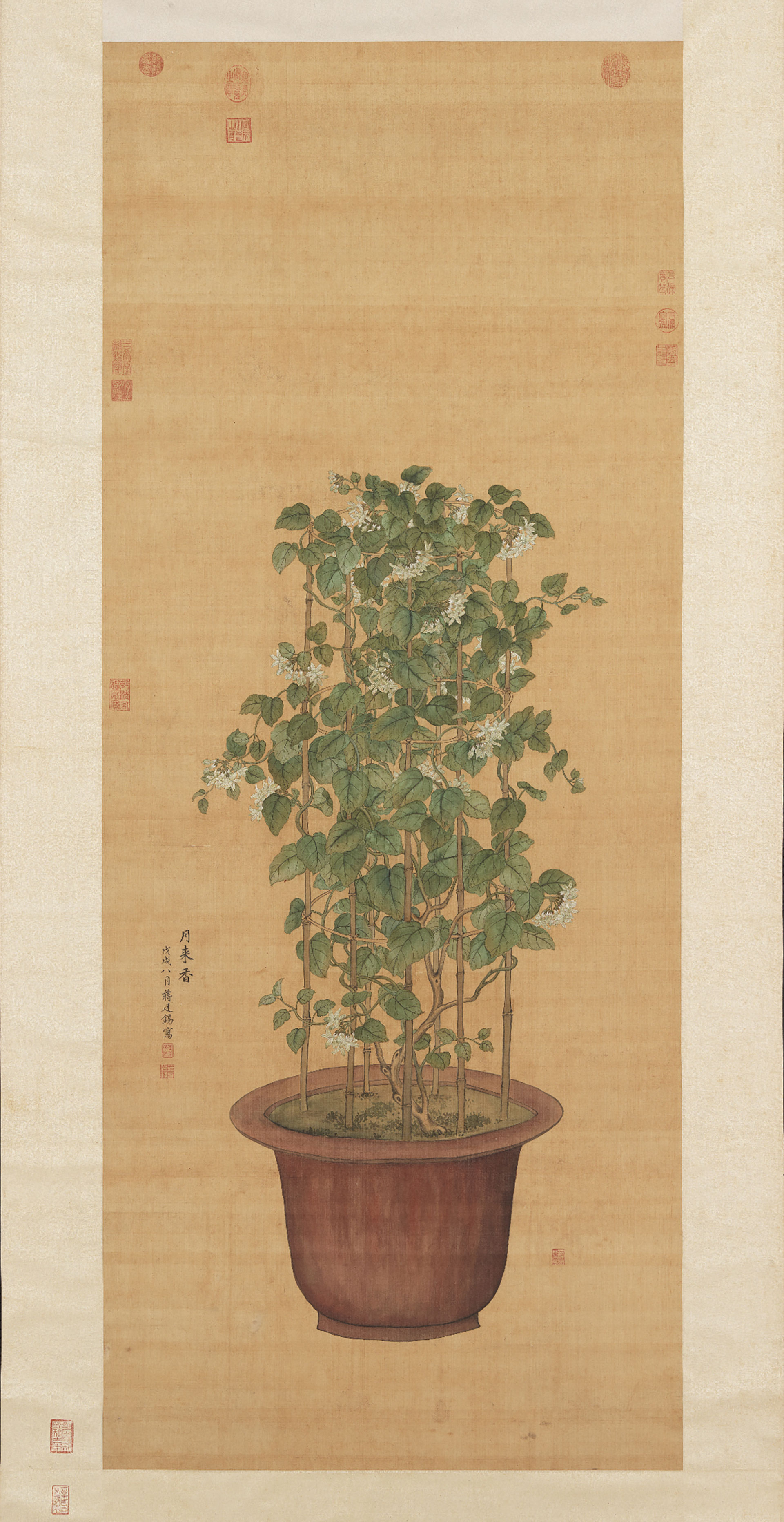

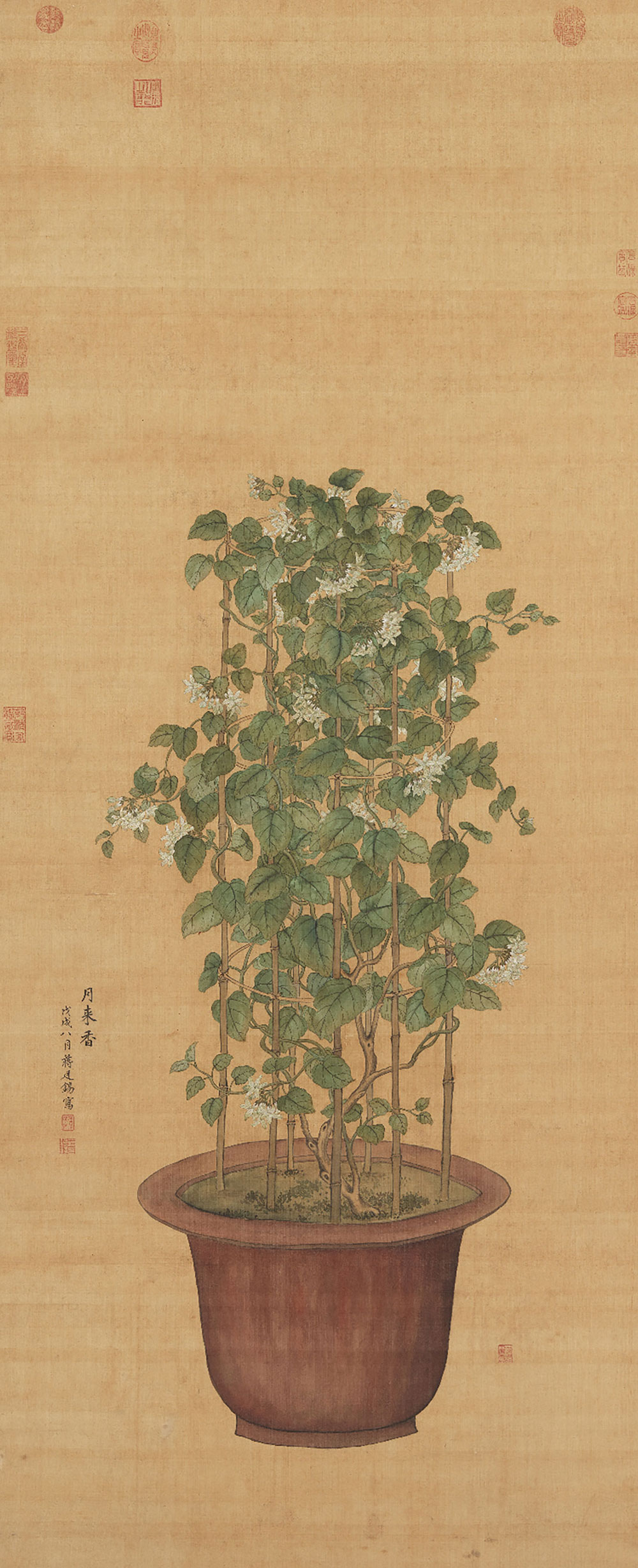

- Tonkin Jasmine

- Jiang Tingxi, Qing dynasty

- Silk

This piece, which was completed in the sixth lunar month of Emperor Kangxi’s seventeenth year in power (1718), depicts a brown porcelain flowerpot in which a bamboo frame gives support to a tonkin jasmine plant clinging to it as it grows. This pot’s design is very similar to that of the glazed purple pot with a brown base seen in “Ginseng Flower,” another of Jiang Tingxi’s paintings. This type of pot was probably designated for use in the imperial palace gardens’ replanting projects.

Given its appearance, the plant depicted in this work is probably “tonkin jasmine”. The Illustrated Catalogue of Plants, which was published in the Qing dynasty in 1848, records that “Ginseng Flower” had been planted in northern China, but that because this plant did not fare well in the cold climate, it was primarily found growing in the southern provinces of Fujian and Guangdong.

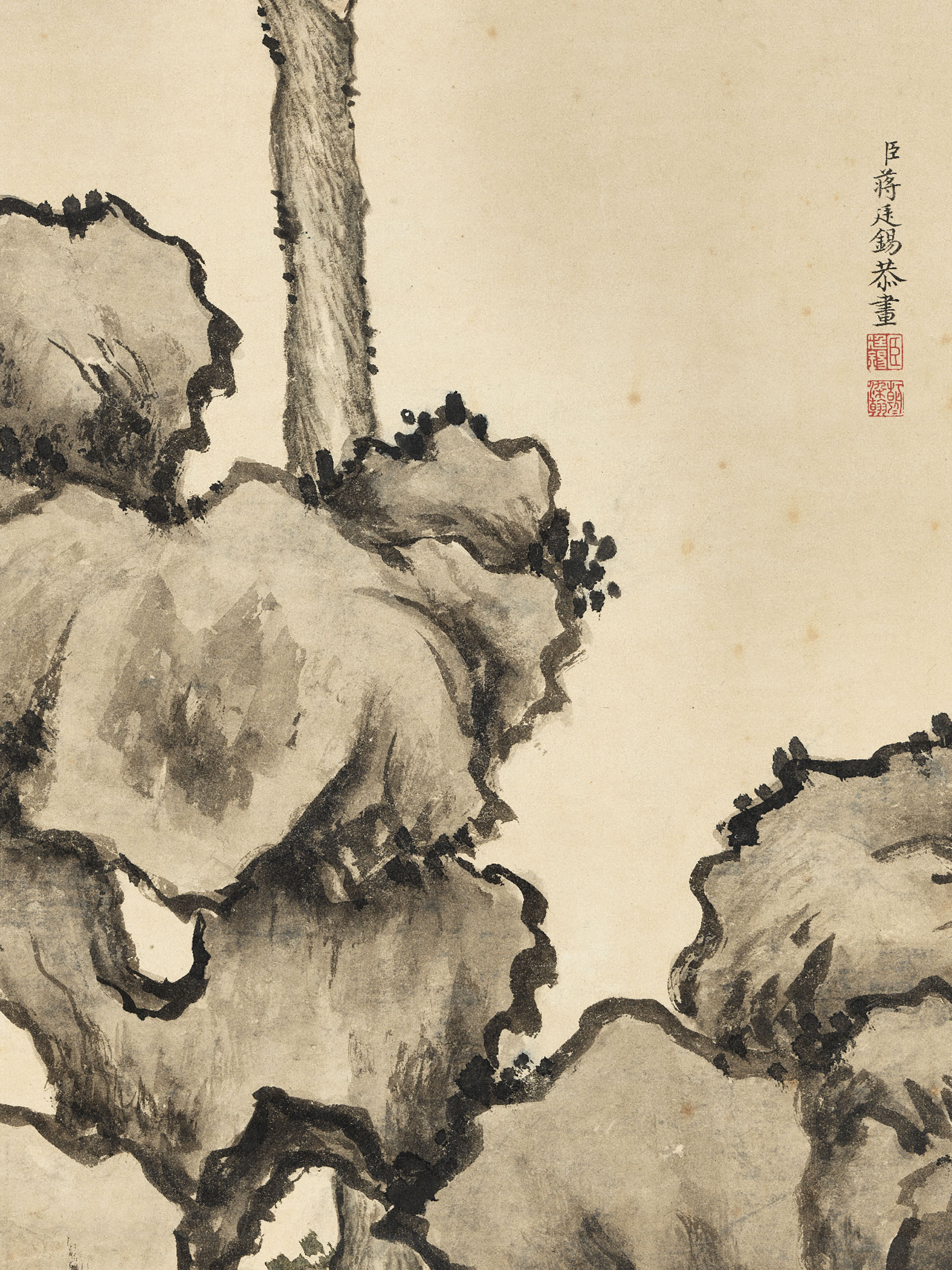

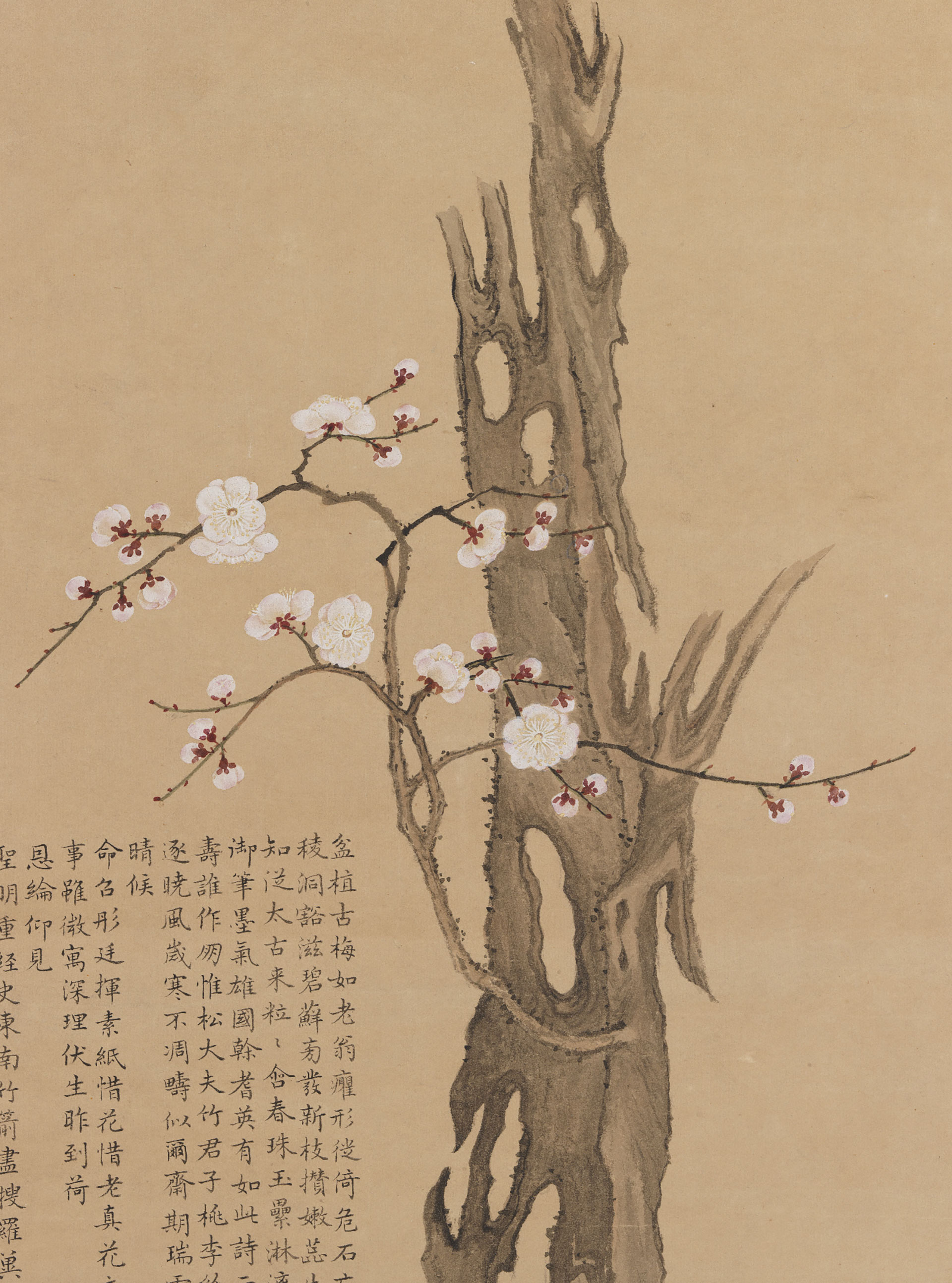

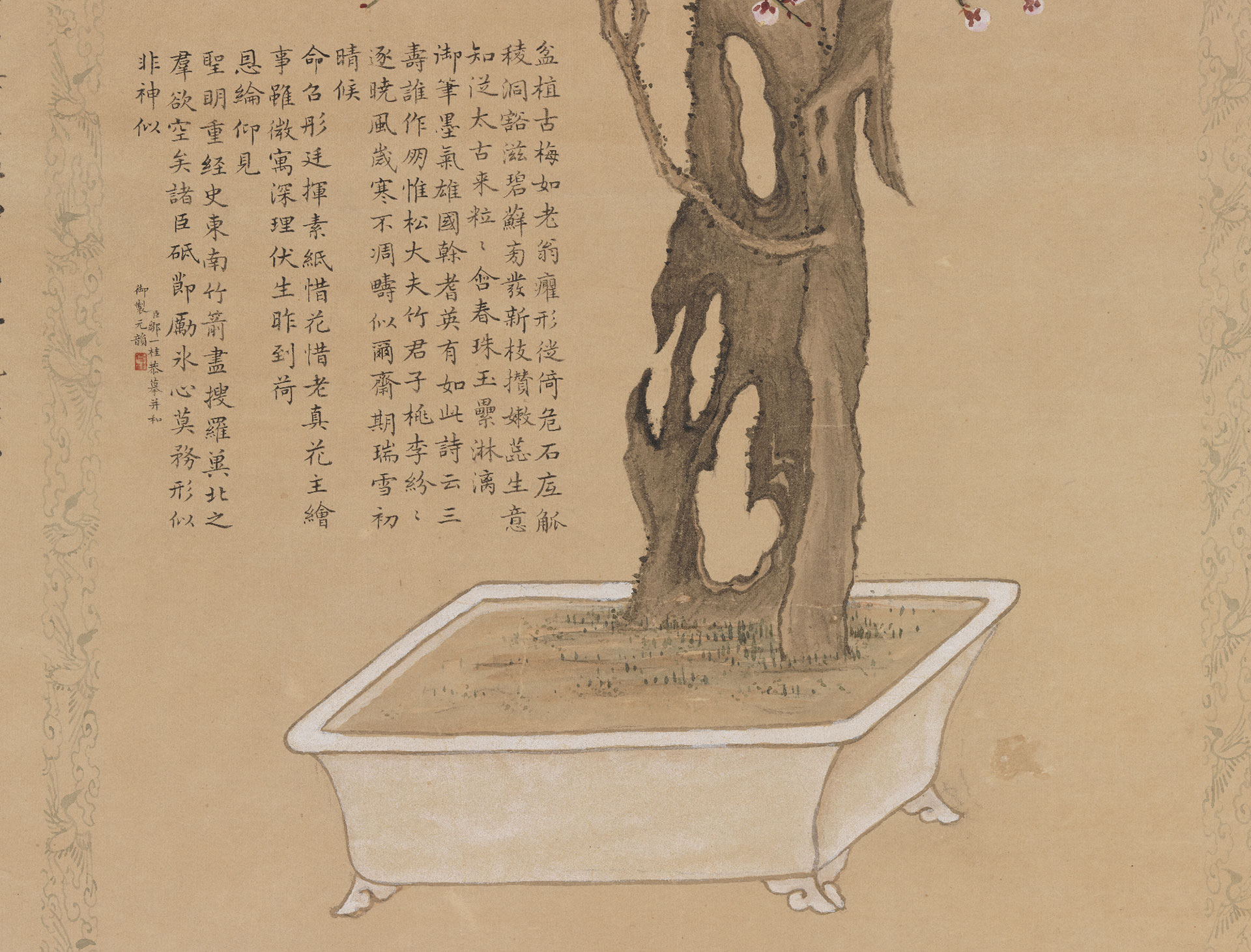

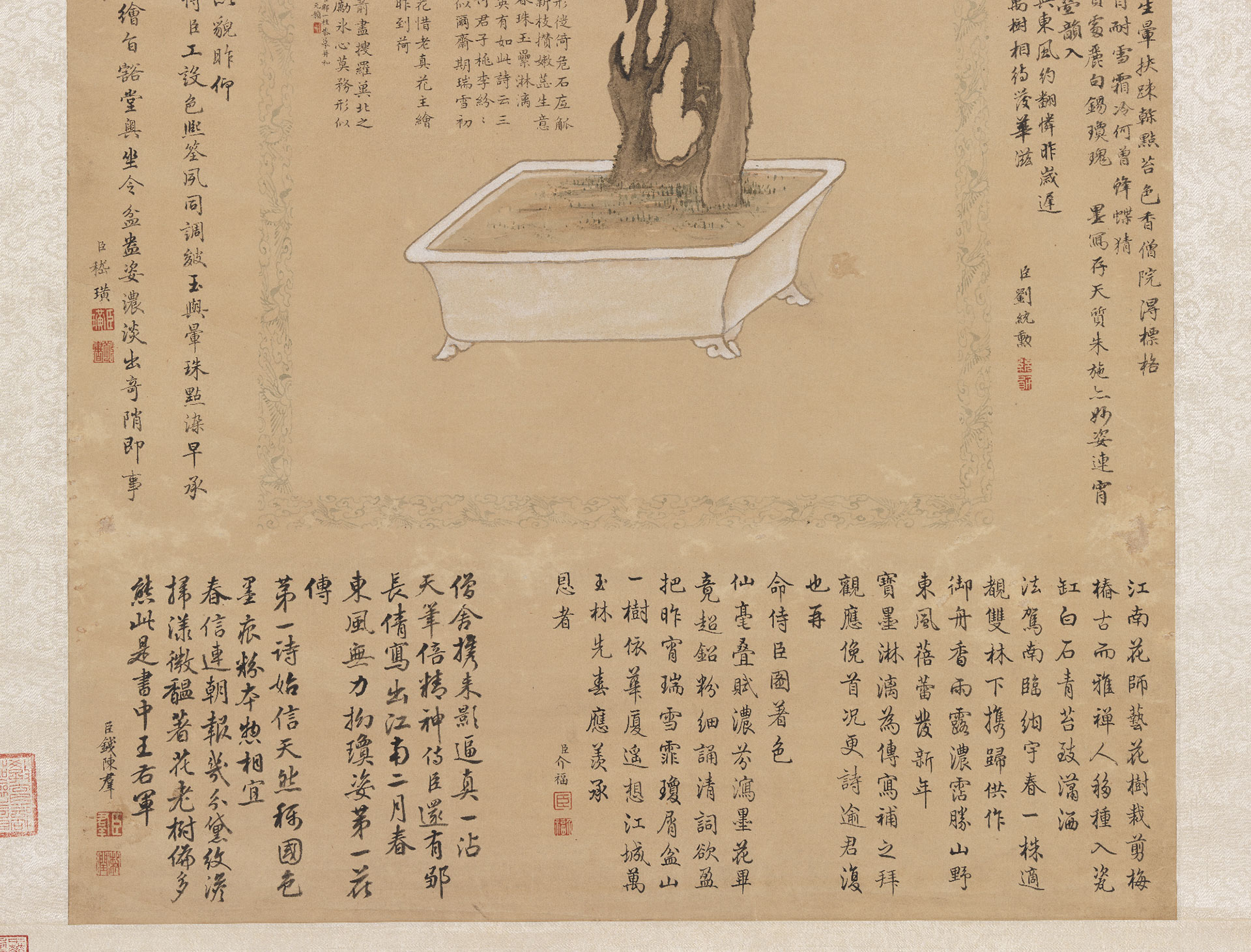

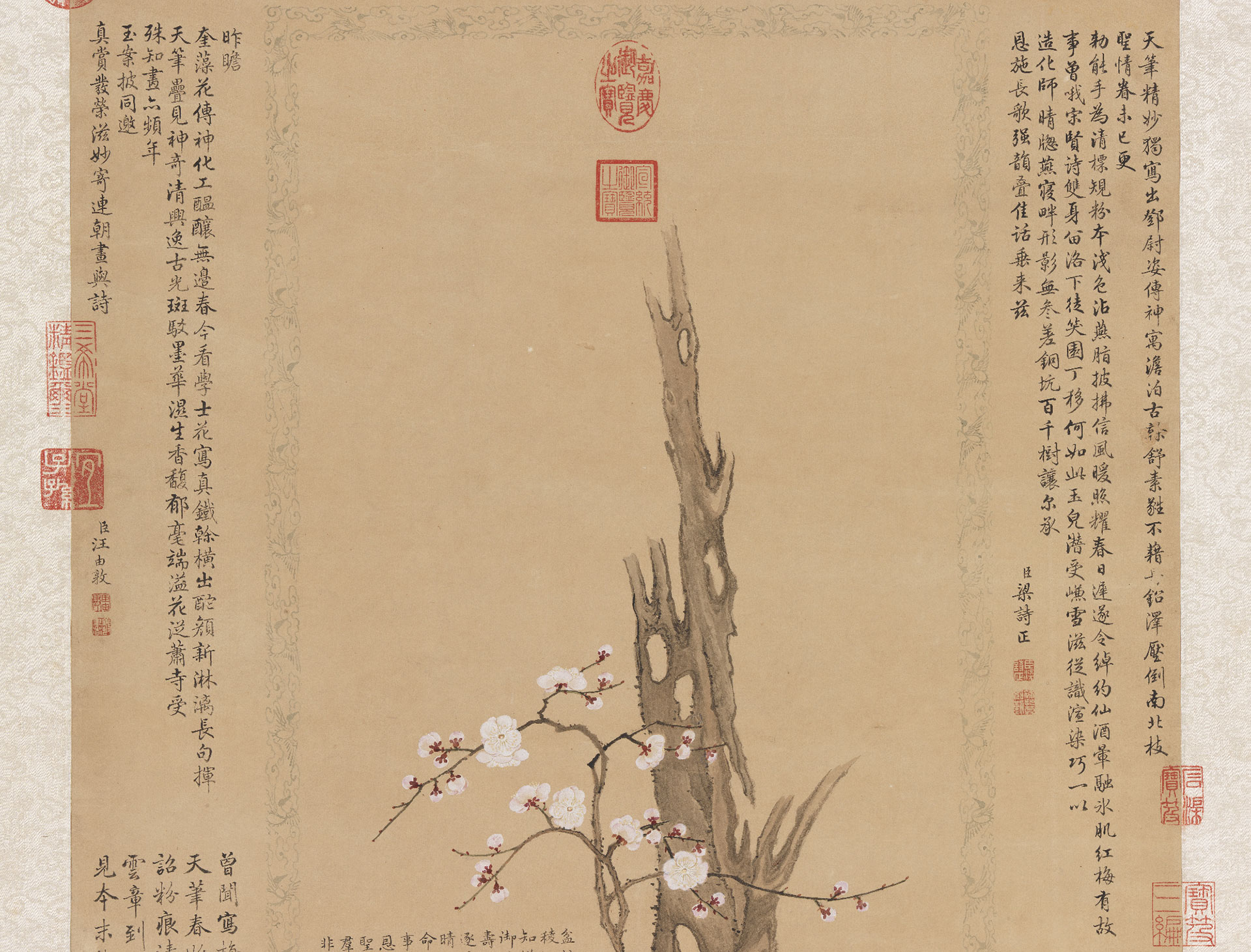

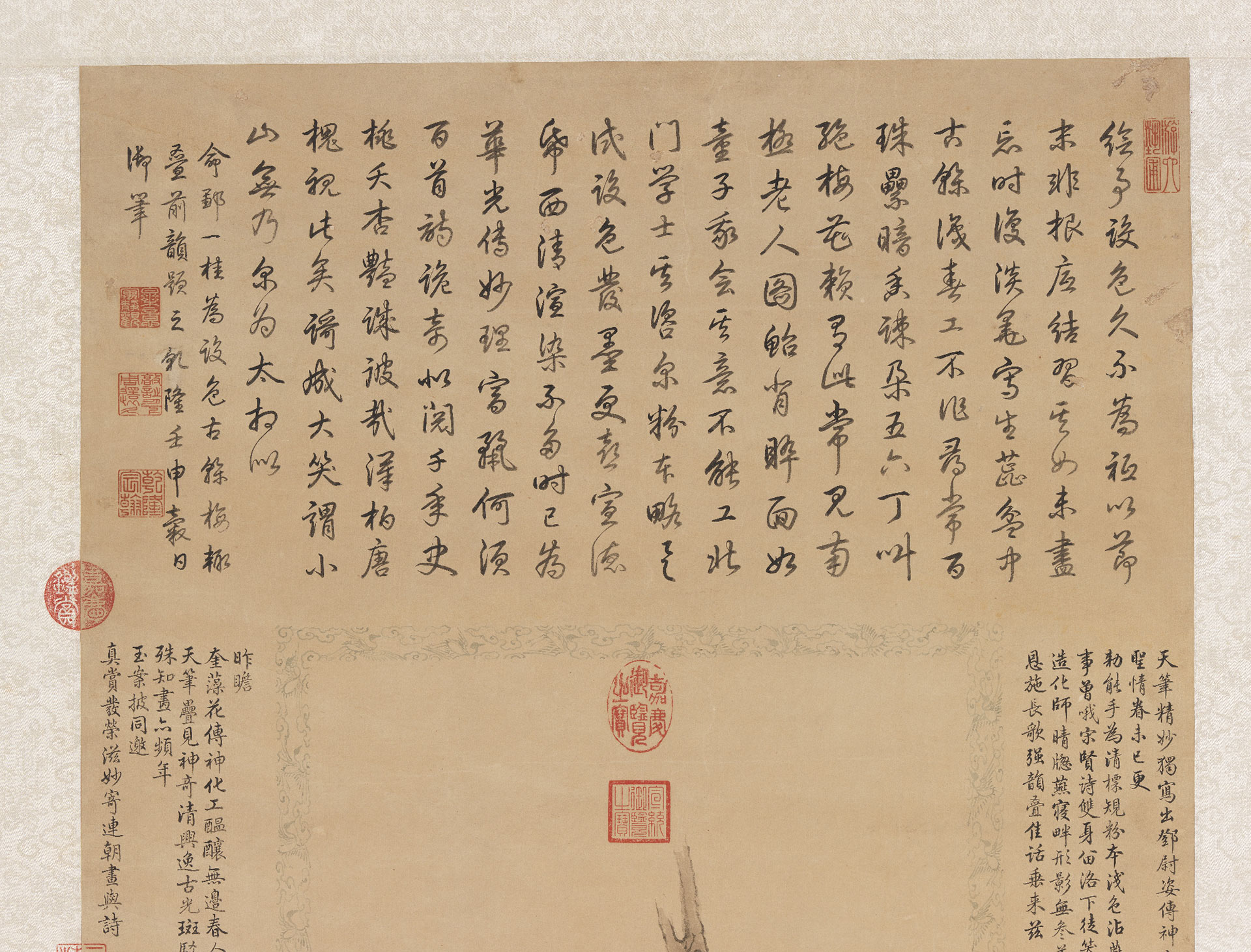

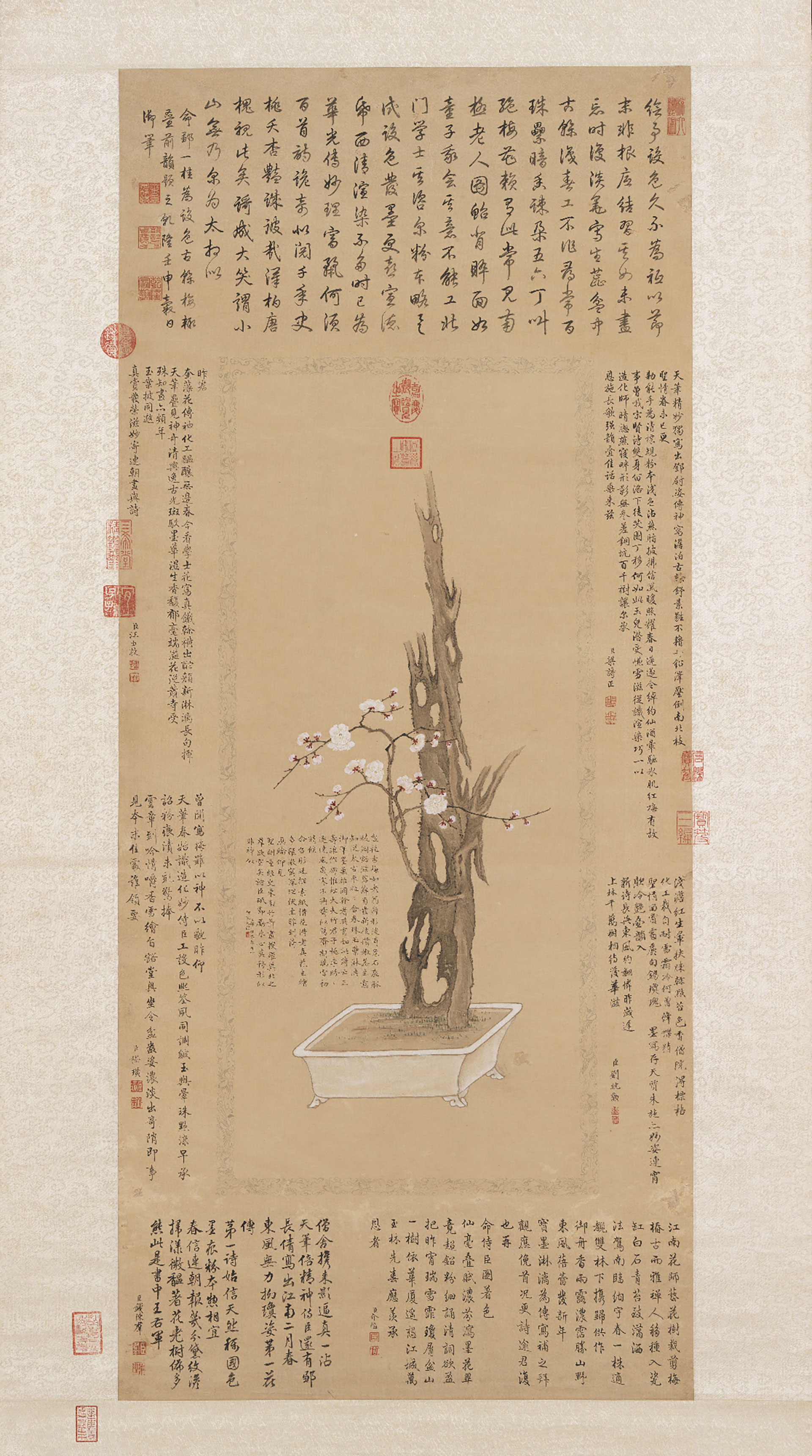

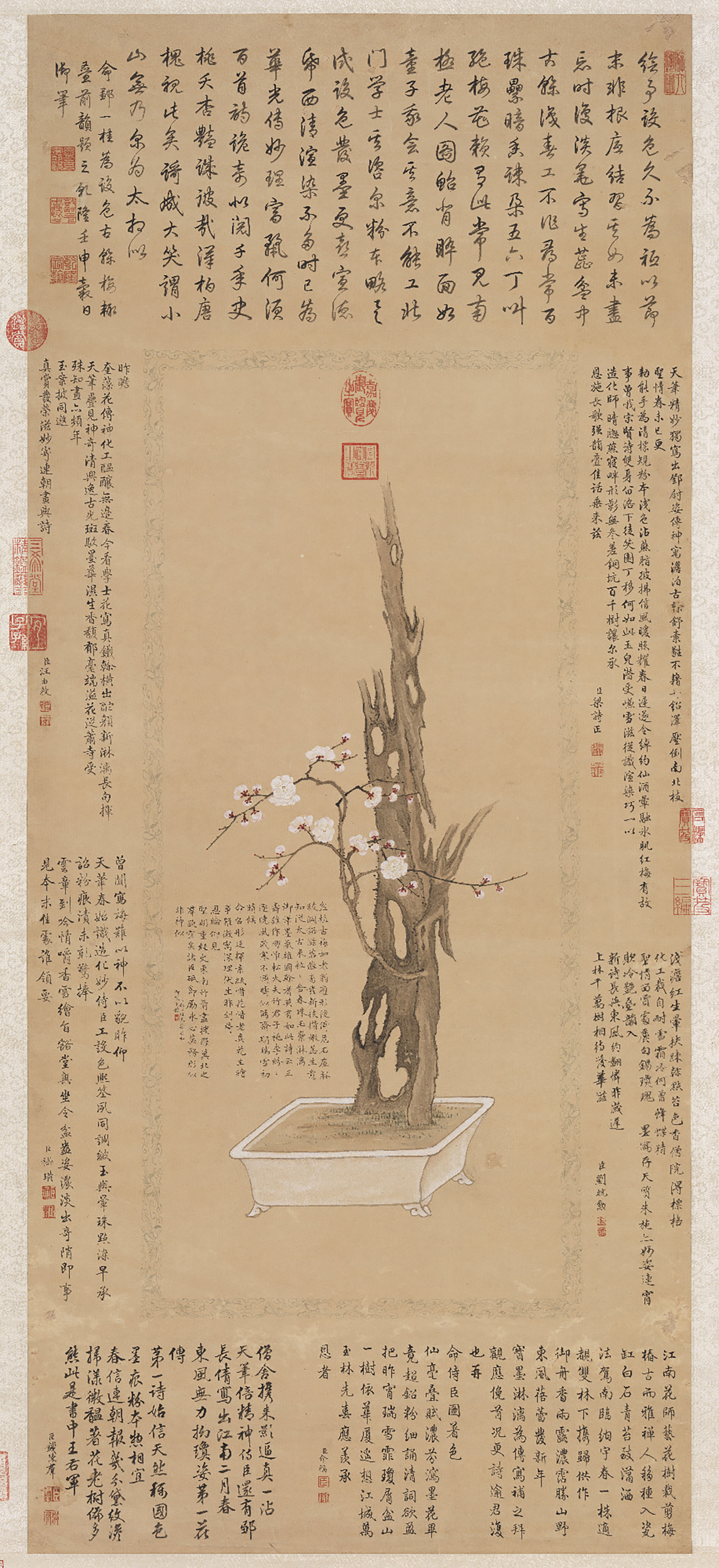

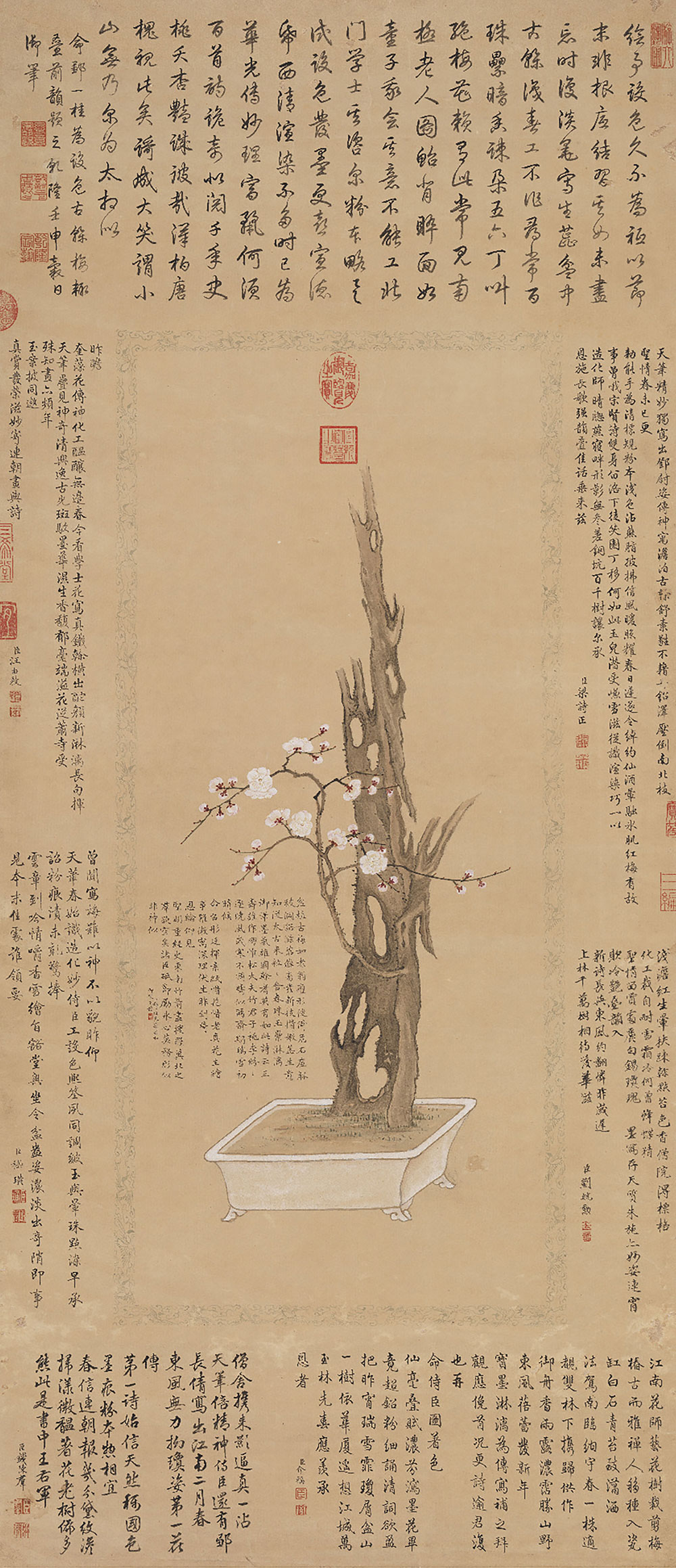

- Ancient Tree Trunk with Plum Blossoms

- Zou Yigui, Qing dynasty

- Paper

In 1751, following his first southern expedition, Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) had an ancient plum tree relocated to the Old Summer Palace in Beijing. The tree flowered unseasonably early the following year. Qianlong created a monochrome painting of this plant entitled “Ancient Tree Trunk with Plum Blossoms Painted by the Emperor,” and then ordered Zou Yigui (1686-1772) to make a full-color copy of his painting using special paper that was given to the Qing court as tribute. The paper, made from the bark of blue sandalwood trees (Pteroceltis tatarinowii) and rice straw, is named “Xuande,” after the Ming dynasty reign period in which it was invented. Once the painting was completed, Qianlong then gathered numerous scholar-attendants who inscribed it with poems sharing the same rhyme schemes.

This painting depicts a bonsai arrangement with an ancient plum tree that was cared for in the imperial palace greenhouses. The ancient bonsai tree, which was planted in a white pot, grew a new branch from one of its sides. A succession of pink plum blossoms came into bloom on this branch, making it auspiciously evocative of the phrase “spring comes upon a withered tree.”

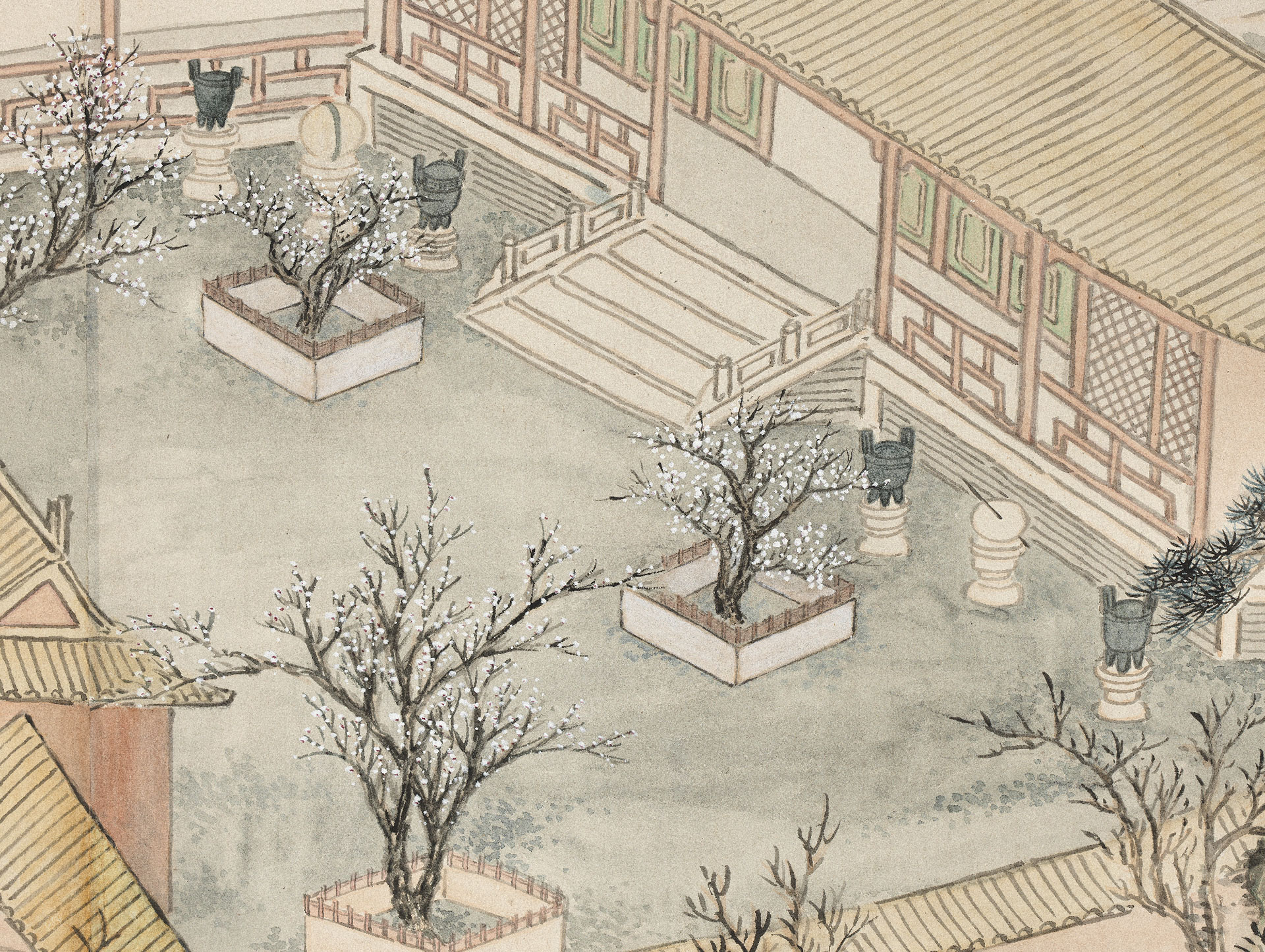

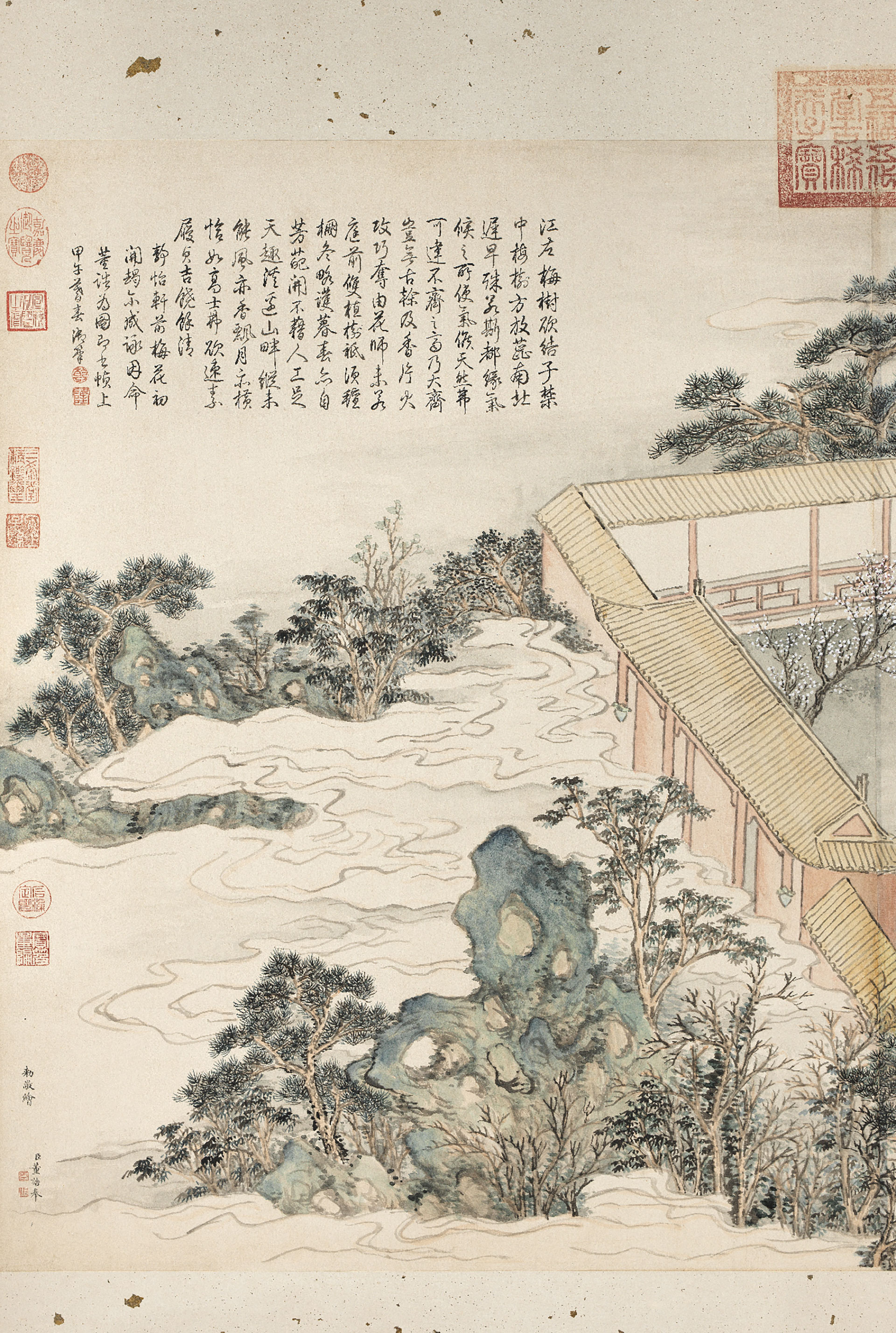

- Plum Blossoms at the Hall of Tranquility and Happiness

- Dong Gao, Qing dynasty

- Paper

The building in this painting is the Hall of Tranquility and Happiness located in the Jianfu Palace. The hall’s courtyard is appointed with a sundial, armillary sphere, cauldrons, and four carefully cultivated ancient plum trees. In the painting’s upper left corner is a poem Emperor Qianlong wrote in his thirty-ninth year of reign (1774) entitled “A Paean to the Plum Blossoms at the Hall of Tranquility and Happiness.” The poem begins by mentioning the difference between the climates of southern and northern China. Specifically, because the warmth of spring comes later in the north, southern plum trees have already fruited by the time those in the north have just started flowering. The poem then laments how difficult it is spur bonsai plum trees to flower earlier using charcoal braziers, and how this method is inferior to keeping the trees warm using thick felt tents and letting them blossom naturally. These lines demonstrate that the plum trees replanted in the imperial palaces had already adapted to northern climates by Qianlong’s day.

While most plum trees in northern China used to be cultivated in pots, the four plum trees replanted in the courtyard at the Hall of Tranquility and Happiness in the first year of Emperor Qianlong’s (1711-1799) reign were cultivated successfully. Qianlong, who mentioned these trees in several of his poems, seemed to have been quite pleased with this turn of events.