Findings from Beyond the Great Wall

The Kangxi Emperor (born Aisin-Gioro Xuanye; 1654-1722) was a Manchu emperor endowed with an adventurous and investigative spirit. On numerous occasions he led his entourage of ethnically Han scholar-attendants north of the Great Wall in order to personally oversee comparative studies of the differences between the climate, plants, and animals in that region and those of the empire’s southern reaches. Kangxi intended for the results of these exploratory expeditions to be included in the official imperial records, thereby giving rise to a new system of knowledge unique to the Qing empire.

In addition to appreciating the scenery and flora and fauna they laid eyes upon during their excursions, the retinues of scholar-officials who accompanied the emperor also produced firsthand written and illustrated records of their observations. The various wild plants and flowers that previously escaped notice due to their geographic inaccessibility were etched into the emperor and his scholar-attendants’ memories, and thereupon became novel subject matter in the painted and calligraphic creations of Qing dynasty court artists.

Brightly Colored and Resistant to Cold

Flowering plants from beyond the Great Wall are endemic to relatively cold, high-altitude regions. These higher altitudes expose the plants to more ultraviolet light, which leads them to develop even brighter coloration. Paintings-from-life created by the artists who accompanied the emperors on their journeys don’t merely clearly depict plants’ blossoms, leaves, and stems—in fact, the painters also attempted to portray the sumptuous colors of the flowering plants they encountered. When the emperors wrote poems of praise for these plants, they anthropomorphized their flowers’ characteristic resistance to cold, turning it into a symbol for noble, unsulliable moral conduct.

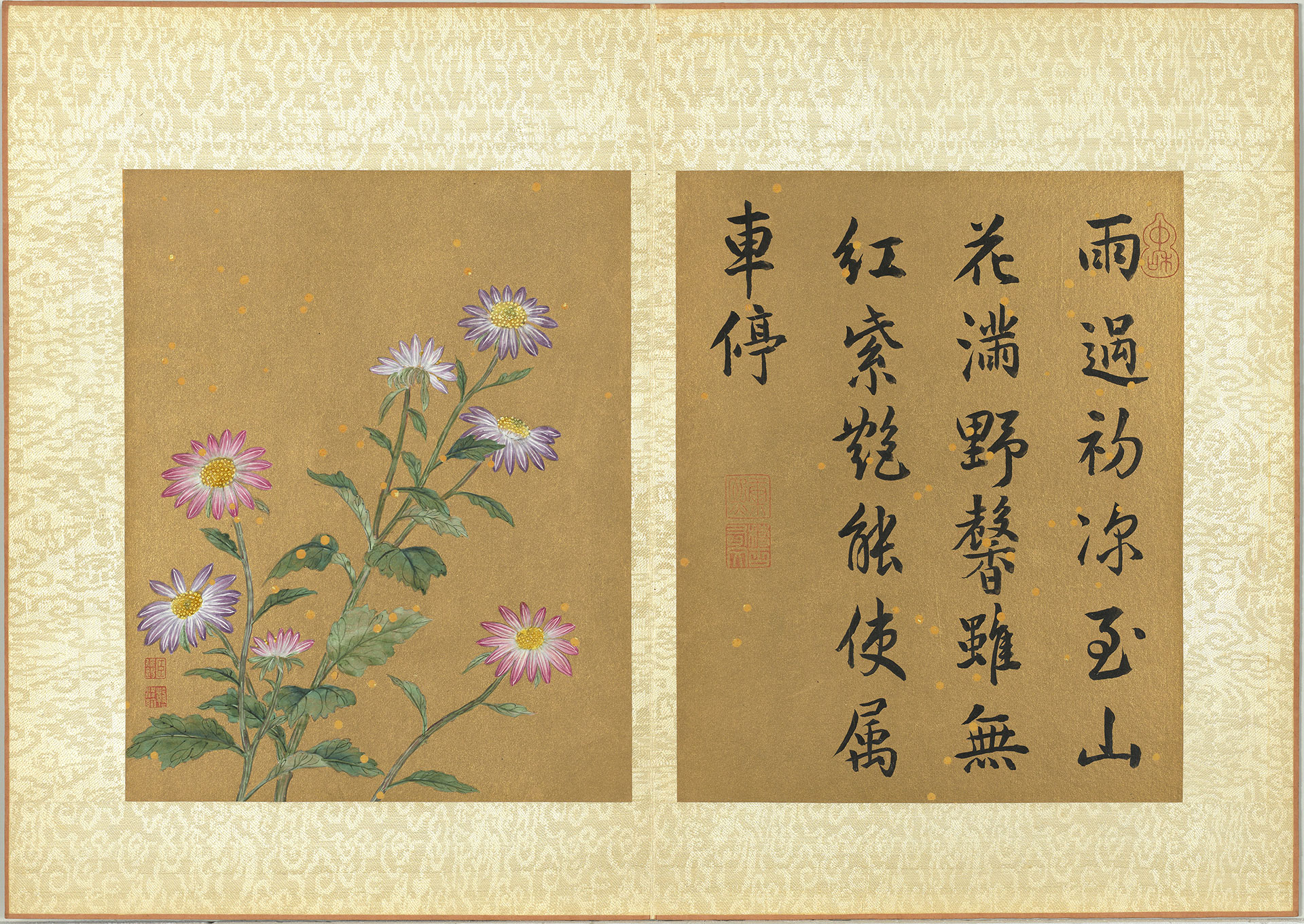

- Wild Chrysanthemum

- Jiang Tingxi, Qing dynasty

- Paper

This painting depicts a cutting from a chrysanthemum plant with purple flowers. Its upper portion contains a poem written in the hand of Emperor Kangxi (1654-1722) in the autumn of the forty-fourth year of his reign (1705). The flowering plant described in the poem is likely a wild chrysanthemum found growing north of the Great Wall—it can thus be inferred that the painting depicts Callistephus chinensis, also known as China aster. According to the Record of All Fragrant Flowers, China aster came to China from Inner Mongolia during the Yuan dynasty. By the time of the Qing dynasty, it was already widely distributed in the region north of the Great Wall.

This painting was created primarily using the unoutlined “boneless” painting technique, which means that instead of using pronounced ink outlines, the artist used applications of color to directly depict the plants’ form. The stems, leaves, and blossoms in this painting appear somewhat disordered, such that some of the flowers actually face away from the viewer and appear to have been pressed flat. It has been hypothesized that this is a realistic painting of a flowering specimen that was picked on a northern expedition and brought back to the capital.

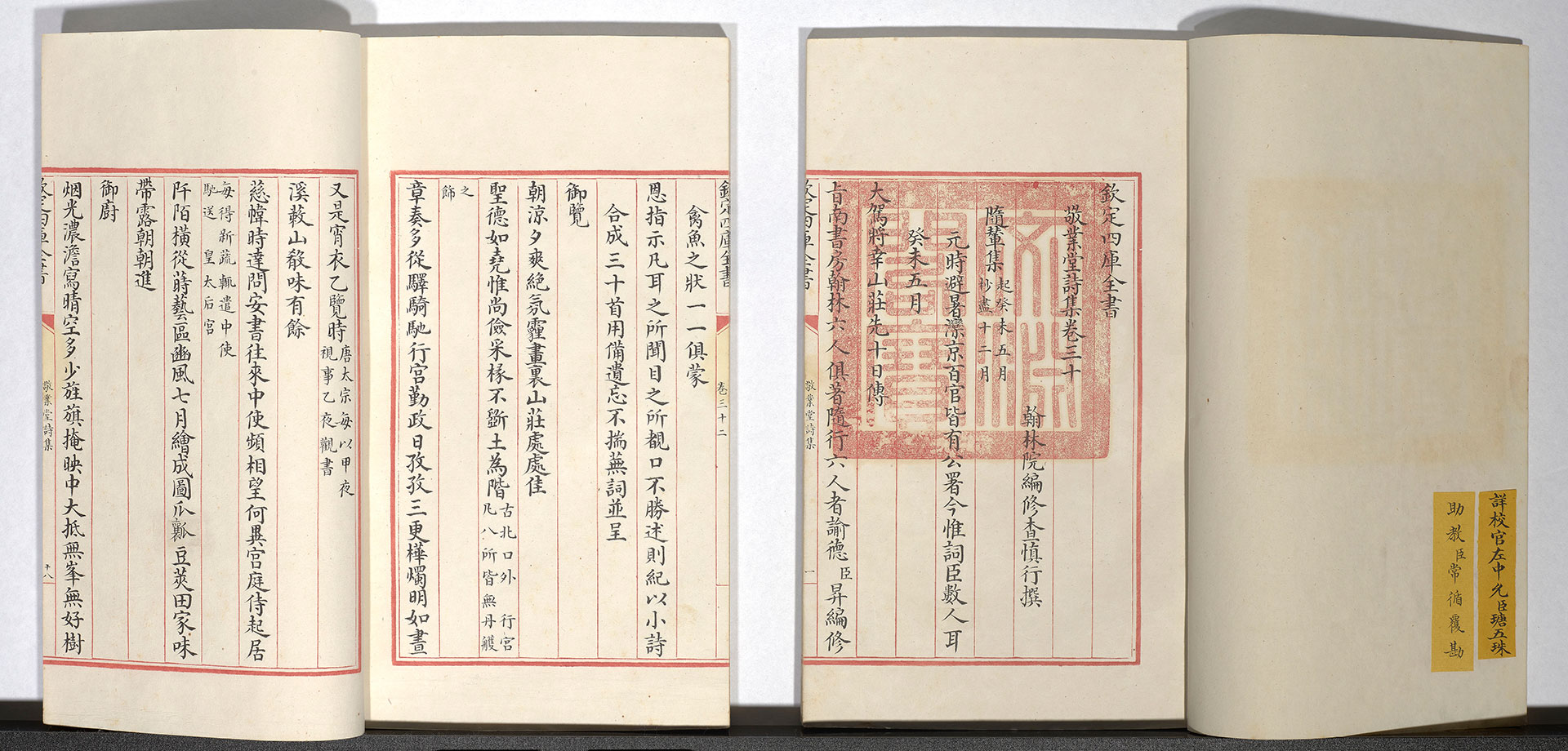

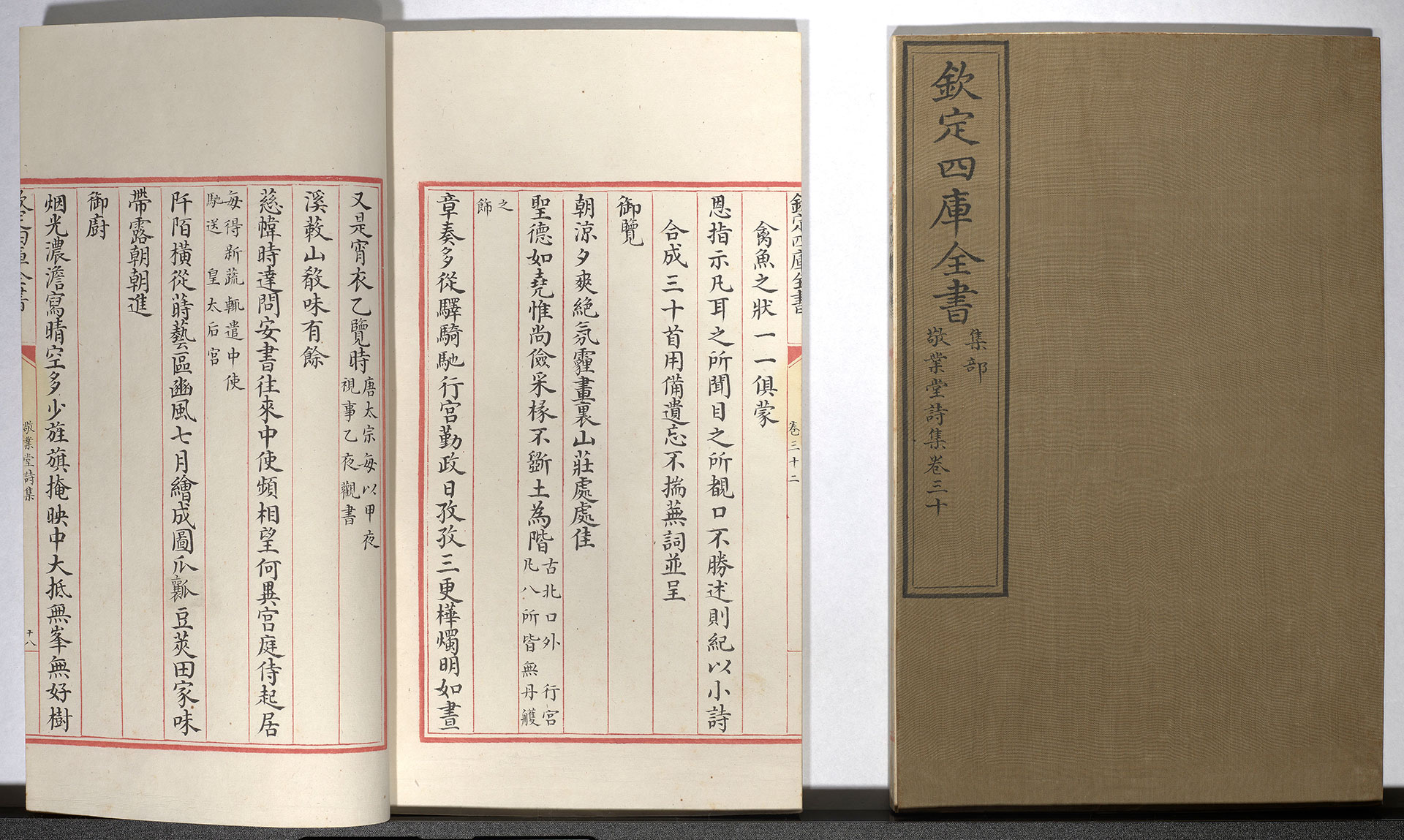

- Hall of Diligence Poetry Anthology

- Cha Shenxing, Qing dynasty

Cha Shenxing (1650-1727) was a renowned Qing dynasty poet. He passed the imperial examinations at the level of “presented scholar” in the forty-second year of Emperor Kangxi’s reign (1703), whereupon he was appointed to the Southern Library in the imperial palace. There Cha served as a scholar-attendant, accompanying the emperor when he wrote poems or essays or acting as an amanuensis to transcribe drafts of imperial decrees. Cha’s Hall of Diligence Poetry Anthology and Notes from Attending Hunting Expeditions both record numerous stories of the emperor’s interactions with his ministers.

“Unclassified Verses from the Mountain Villas” are freeform poems that record the activities of the more than one hundred attendants who, under Kangxi’s direction, accompanied the emperor on a journey into the realm north of the Great Wall, where they observed the natural environment and its flora, fauna, and ecology. The plants mentioned in this collection of poems—including golden lotus (Trollius chinensis), ouli (Prunus humilis), and a type of tree whose name suggests it was bioluminescent at night were all recorded in the Record of All Fragrant Flowers, which was compiled by scholars in the Southern Library. These poems are a priceless record of the events that took place during the emperor’s tours of inspection.

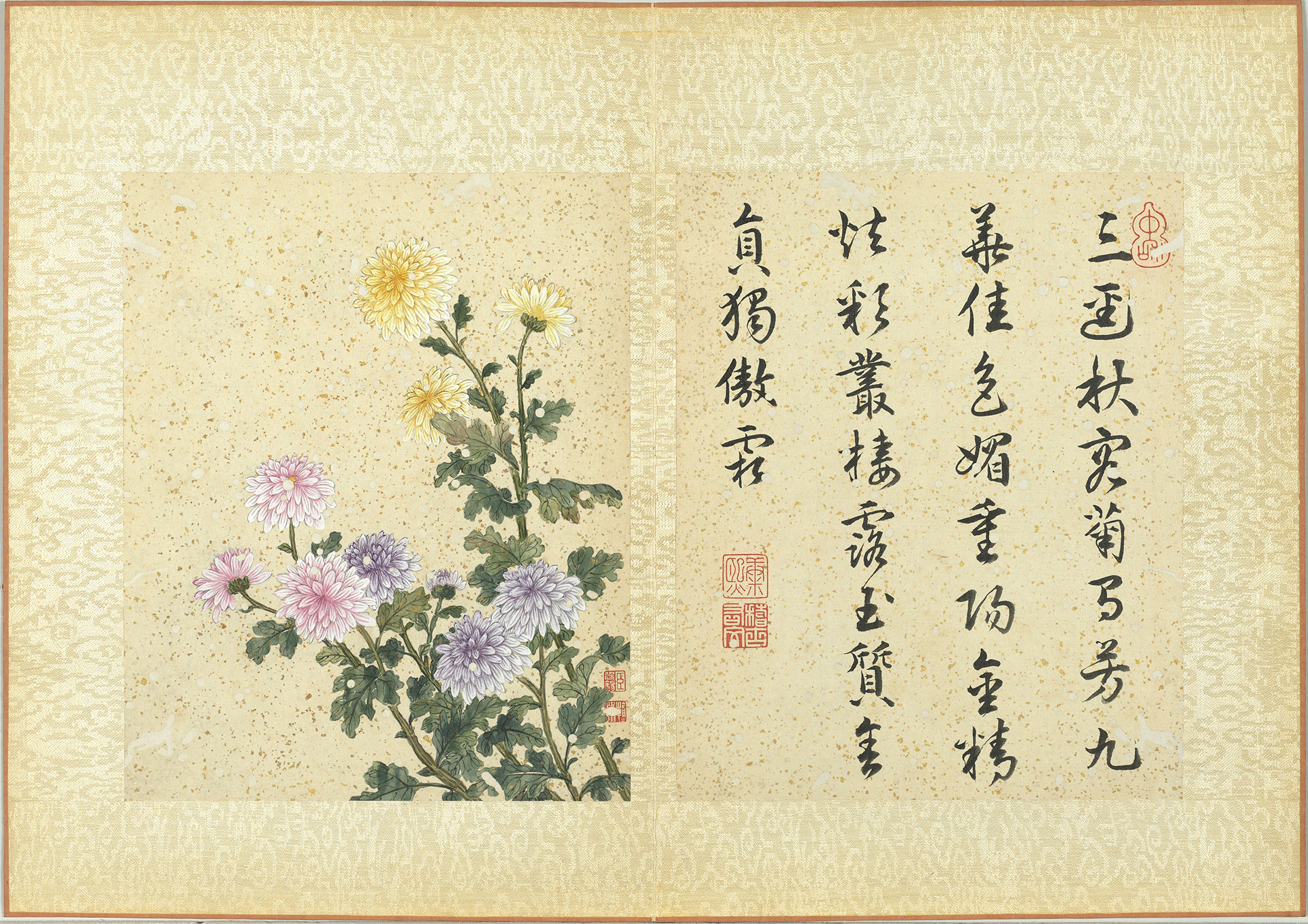

- Paintings from Life (Common Poppy)

- Jiang Tingxi, Qing dynasty

- Paper

“Common Poppy” is a selection from Jiang Tingxi’s (1669-1732) album Paintings from Life. Jiang accompanied the Kangxi Emperor (1654-1722) on expeditions to regions north of the Great Wall on several occasions. This album of paintings is thematically centered on flowering plants that grew beyond the Great Wall, as well as exotic flowers from Europe that were introduced to the imperial palaces.

Jiang used yellows, reds, and purples applied with the unoutlined “boneless” (or mogu) technique to meticulously portray the multicolored, multilayered blossoms seen in this painting. However, around the flower petals’ edges one can still vaguely discern how Jiang sketched the blossoms’ using outlines painted with very pale ink. The scholar Cha Shenxing (1650-1727) wrote that Emperor Kangxi once bestowed him with a plant that looked like a “single-leafed common poppy” (Papaver rhoeas), whose flowers were able to survive the autumn frost. The temperate zone plant he described was likely the type of poppy (genus Papaver) depicted in this painting.

- Painting from Life (Golden Thread Peach Blossoms)

- Jiang Tingxi, Qing dynasty

- Paper

The star of this painting is a plant with yellow, five-petalled blossoms growing next to a moss-covered stone, which is set off by a pair of dragonflies, thistles and thorns, and various weeds. The yellow blossom most likely belongs to a plant in the genus Hypericum. The Chinese name given to the plant in this painting translates as “golden thread peach blossom,” reflecting the similarity of its petals to those of peach blossoms, as well its gold filigree-like stamen.

This painting is very similar in composition to the illustrations printed from woodblocks that are found in Collected Illustrations of the Three Realms, a “leishu” published during the Ming dynasty. Leishu (which literally means “category book”) were encyclopedia-like compilations filled with writings covering different categories of knowledge. In contrast with traditional botanical illustrations—which simply displayed plants’ anatomical features—the artists who created printed illustrations in leishu began to strive for aesthetic beauty and compelling compositions. They thus embellished their images with scholars’ stones and naturalistic backgrounds. Even though Jiang sought inspiration from these illustrations’ designs, he still placed stress on the painting’s outward-facing blossoms and the hardy, spry segments of the plant’s stems. These elements convey the features of plants growing at high altitudes with relatively little rainfall. They were probably things that Jiang actually observed during his experiences accompanying expeditions north of the Great Wall.

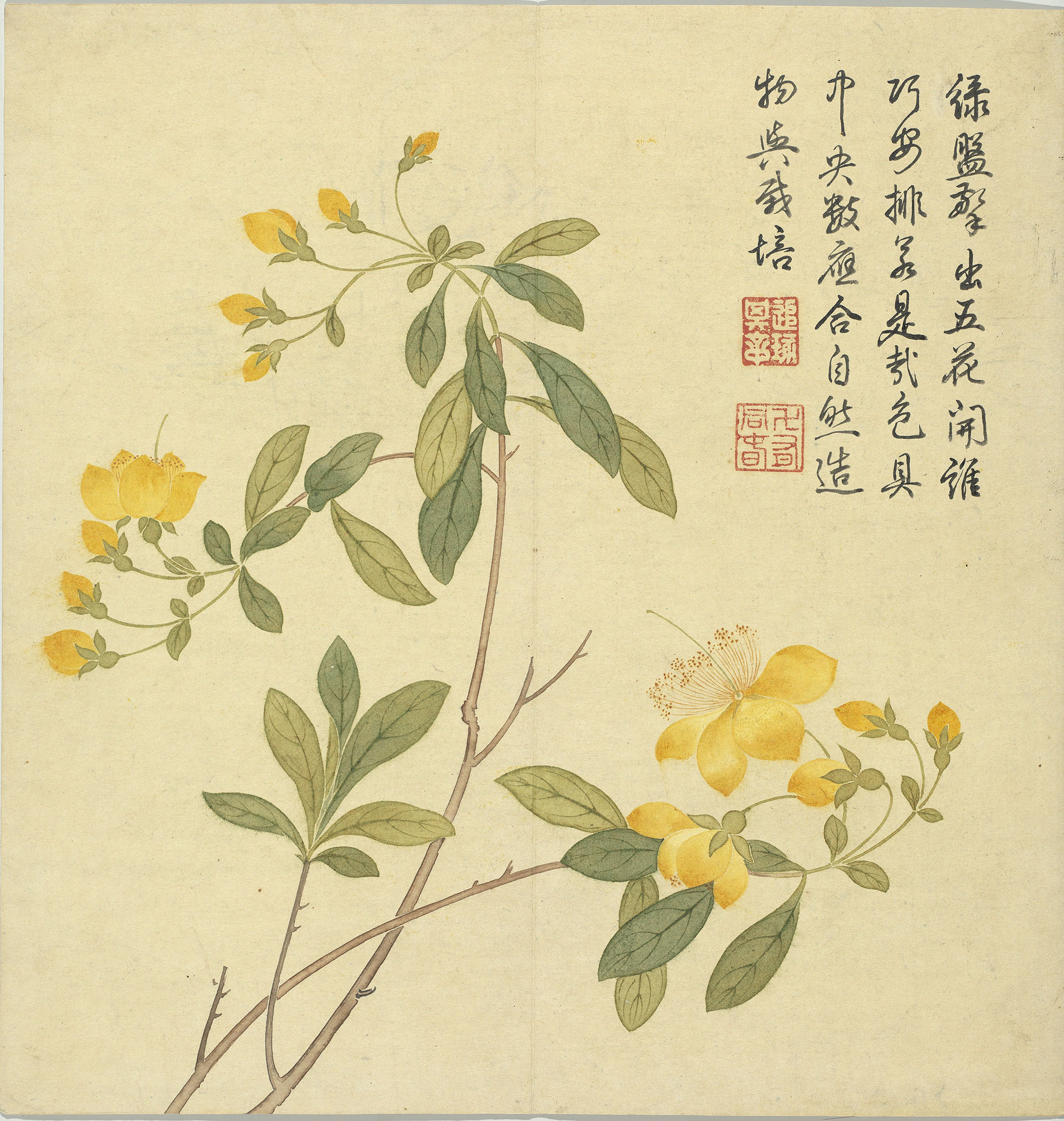

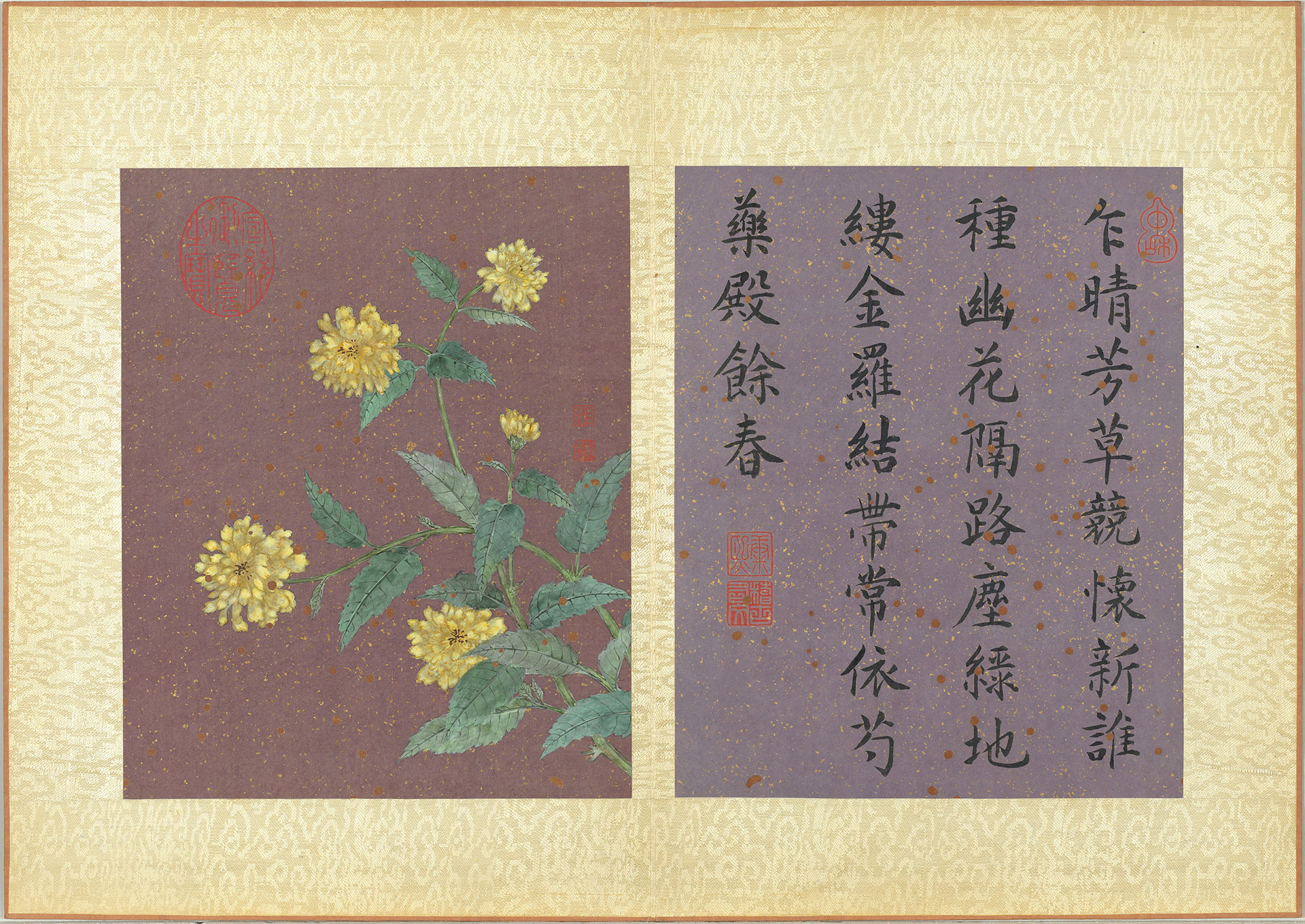

- Flowering Plants (Golden Thread Peach Blossoms)

- Qian Weicheng, Qing dynasty

- Paper

The plant in this painting is depicted with branches, stems, and flowers that grow out in arcs, as well as with blossoms and leaves that have all unfurled in an orderly manner. The locations of each of these exuberantly blooming flowers were laid out in a clever manner that creates the sense that they are somehow engaged in call and response. When the plant’s anatomical features are compared with the painting of the same type of flower in Jiang Tingxi’s album Paintings from Life, we find that this work is endowed with an aesthetic beauty that conveys the elegance and softness of all its parts.

According to the Record of All Fragrant Flowers, golden thread peach blossoms were planted in the imperial gardens in Inner Mongolia during the Yuan dynasty. In his poem devoted to this flower appearing on this painting, Emperor Qianlong praises it for having “a color that is perfectly balanced.” This praise stems from the fact that the flowers are of the same yellow that represented the Qing dynasty imperial family.

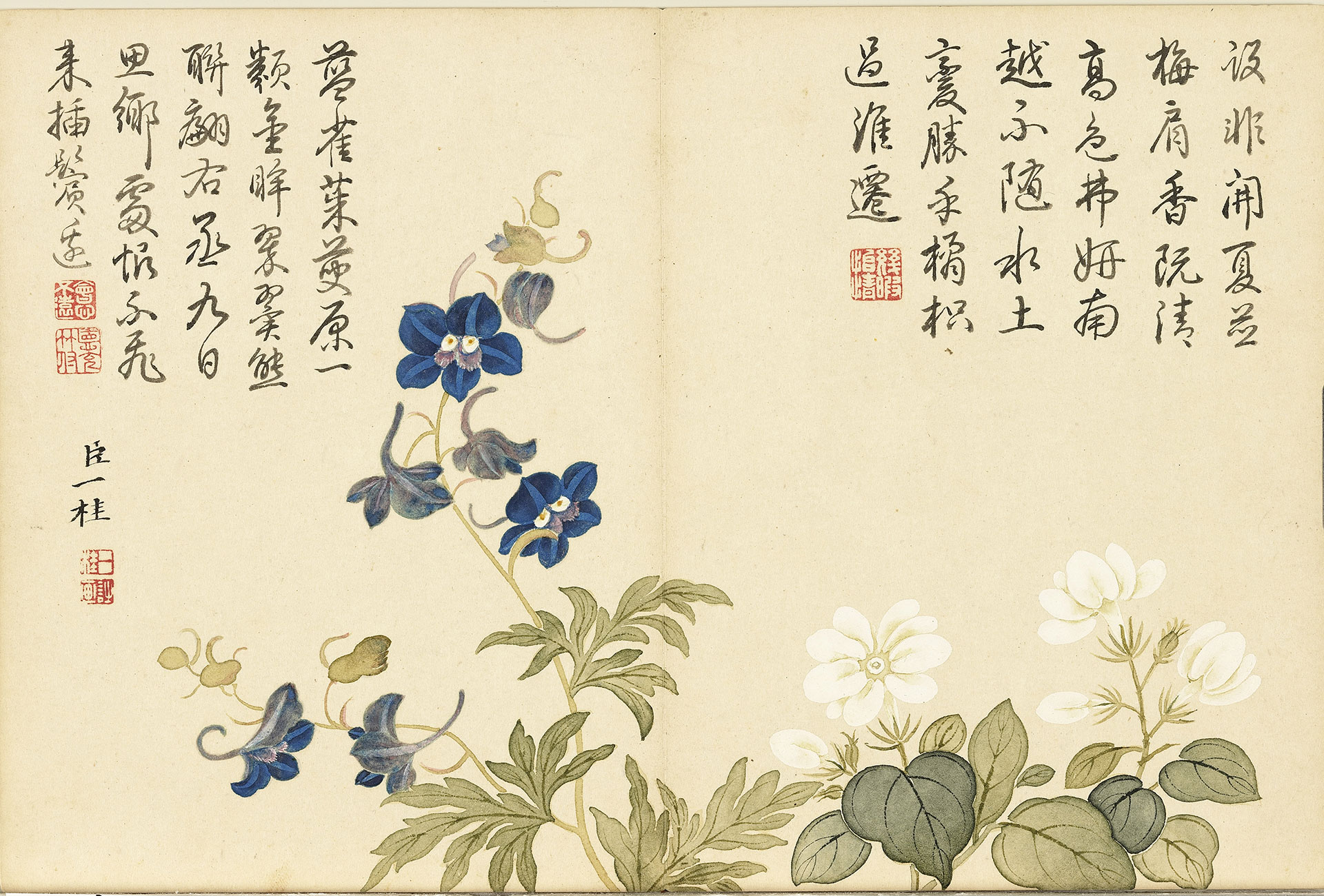

- Paintings from Life (Japanese Bindweed and Chinese Delphinium)

- Jiang Tingxi, Qing dynasty

- Paper

This painting depicts two flowering plants, one with bluish-purple blossoms, and the other blooming in pale pink. There are two long-horned grasshoppers alighted upon the flowers, an element that fills the painting with a sense of aliveness. The bluish-purple flowers are Chinese delphinium (Delphinium grandiflorum L.). The Record of All Fragrant Flowers, compiled under the Kangxi Emperor’s direction, records a plant with a name that translates as “blue sparrow flower,” describing it as being “shaped like a sparrow, with a body, wings, a tail, and a yellow center that looks like two eyes”—this description fits the features of the plant in this painting. The pale pink flower was originally referred to as a “lotus flower” in Qing dynasty records, but is probably Japanese bindweed (Calystegia pubescens Lindl.).

Both of the flowering plants in this painting are endemic to high northern latitudes. Jiang created a clever, striking contrast by pairing the stiff-stemmed Chinese delphinium with the much softer Japanese bindweed.

- Flowering Plants (Jasmine and Chinese Delphinium)

- Zou Yigui, Qing dynasty

- Paper

This painting presents Chinese delphinium and jasmine blossoms painted using the unoutlined “boneless” (mogu) technique, with a poem written by Emperor Qianlong in its upper region. The work’s composition places emphasis on the symmetry of the flowers and leaves, while also drawing attention to the plants’ winding forms. Compared with earlier works painted by Qing dynasty scholar-attendants—where Chinese delphiniums’ flowers and stems tend to be portrayed as quite stiff—in this piece the plant appears quite supple, indicating that it is a later work painted in a more impressionistic manner.

While writing the poem seen here, Emperor Qianlong consulted the entries on Chinese delphinium (which he refers to as “blue sparrow flower”) and Chinese cornelian dogwood blossoms in the Record of All Fragrant Flowers. He came to the conclusion that they were one and the same plant. He thus alludes to a line in a poem by the Tang dynasty poet Wang Wei (701-761), where Wang laments that his faraway brothers must have gathered for the custom of tucking Chinese cornelian dogwood flowers behind their ears on the Double Ninth Festival, only to find him missing from their number. With this allusion, Qianlong introduced the “blue sparrow flower” from north of the Great Wall to a Han holiday tradition, and added a new layer of meaning to the story in Wang Wei’s poem.

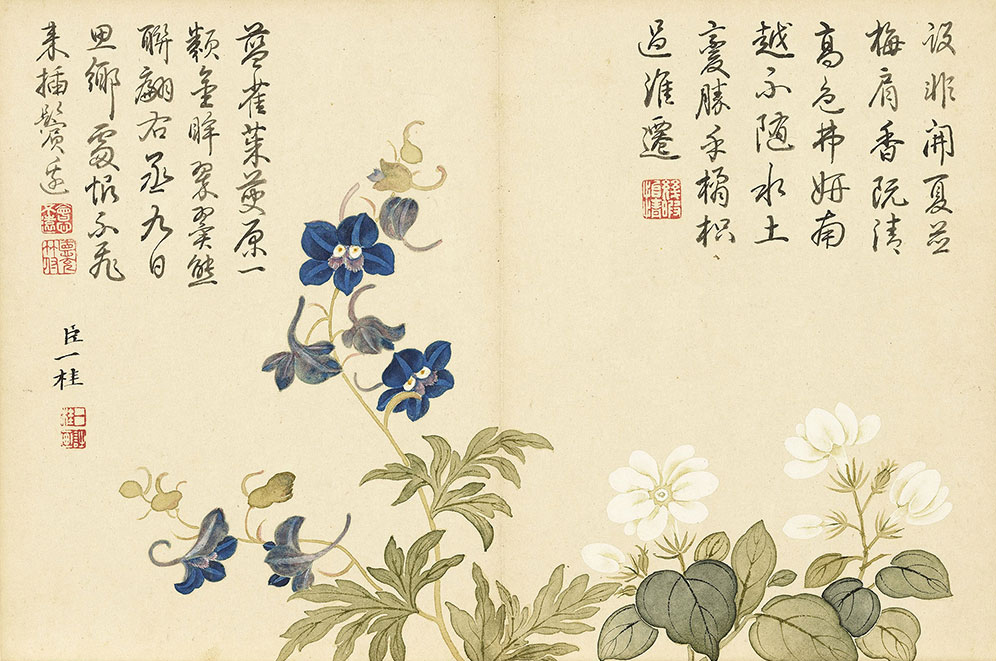

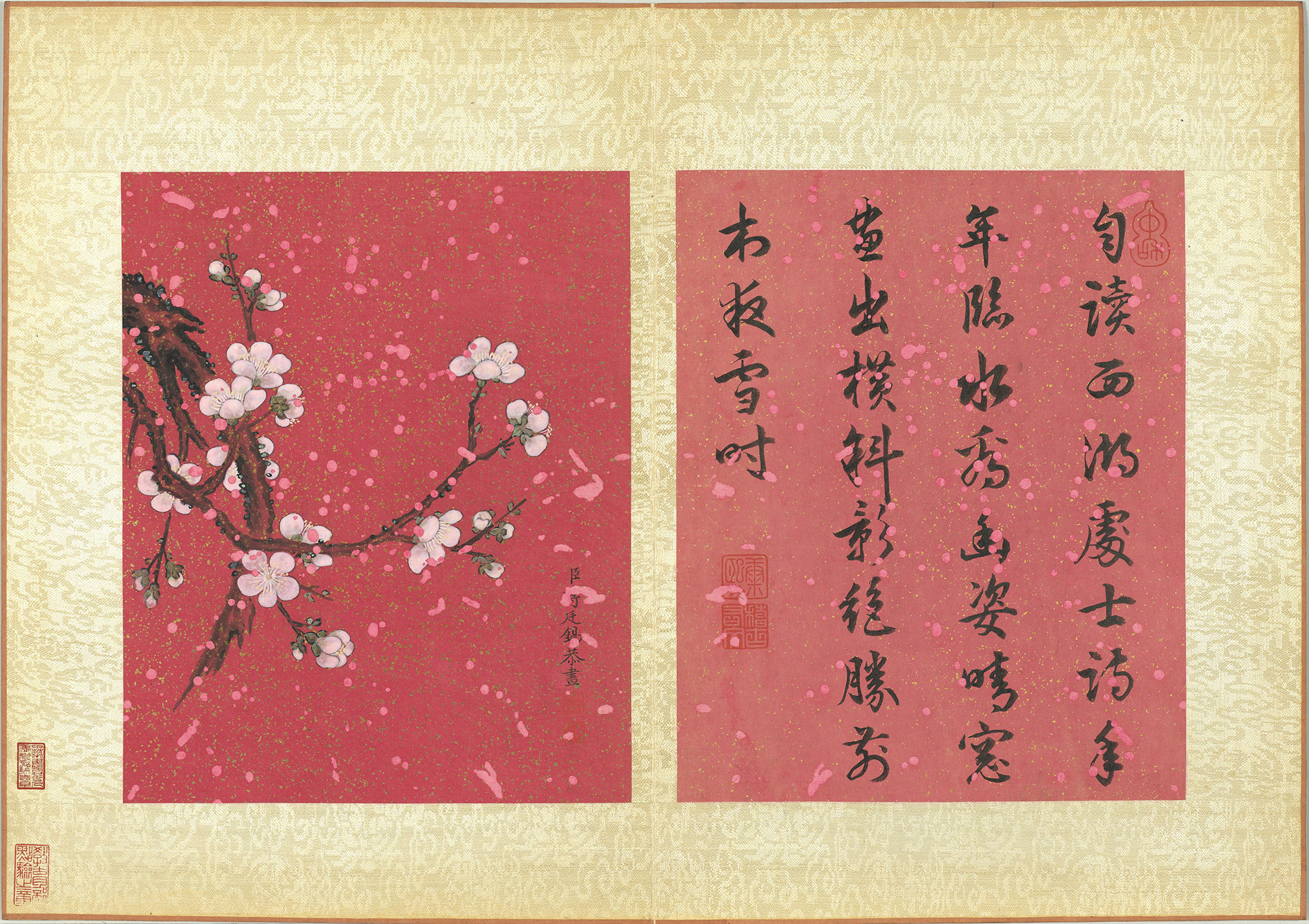

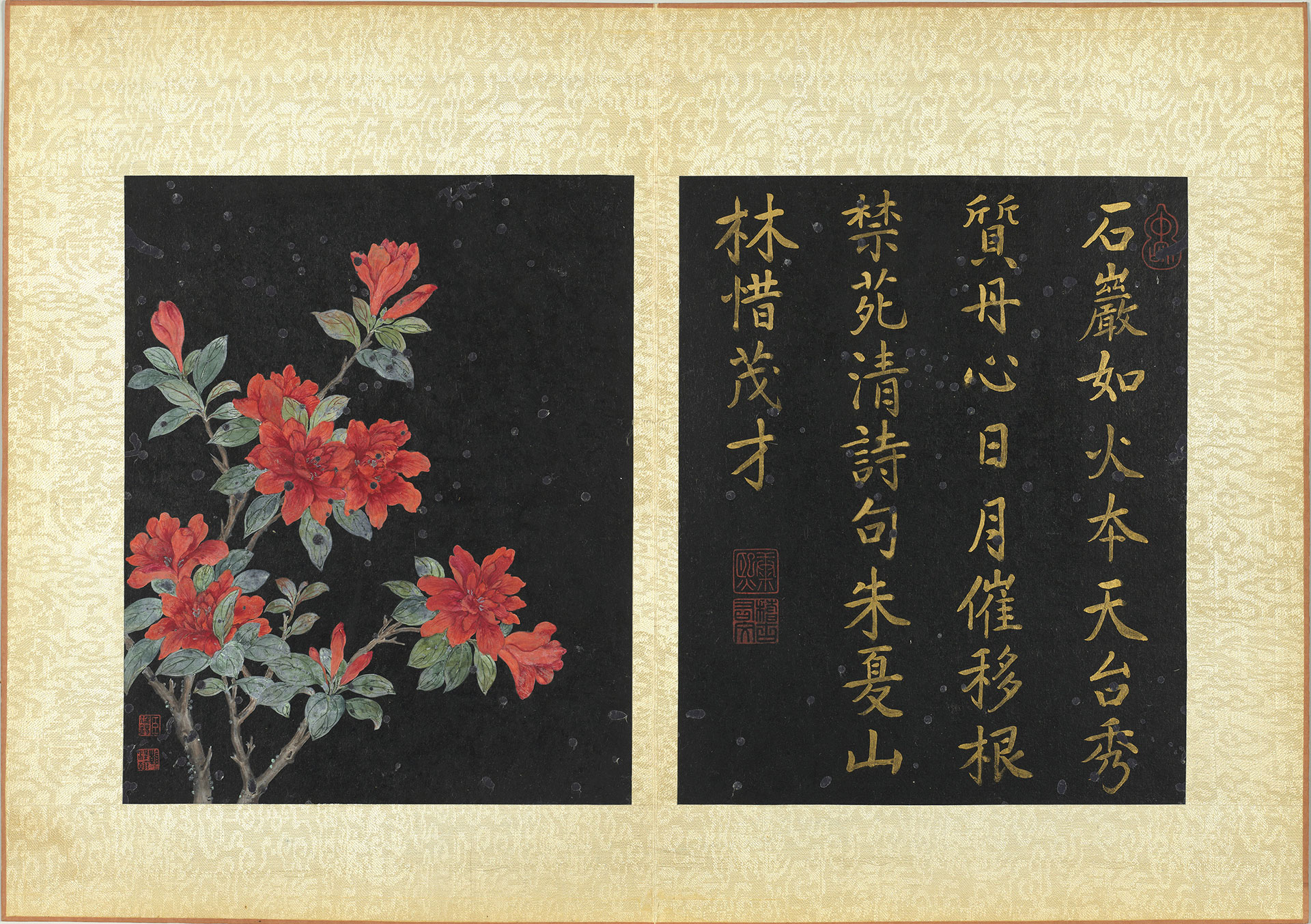

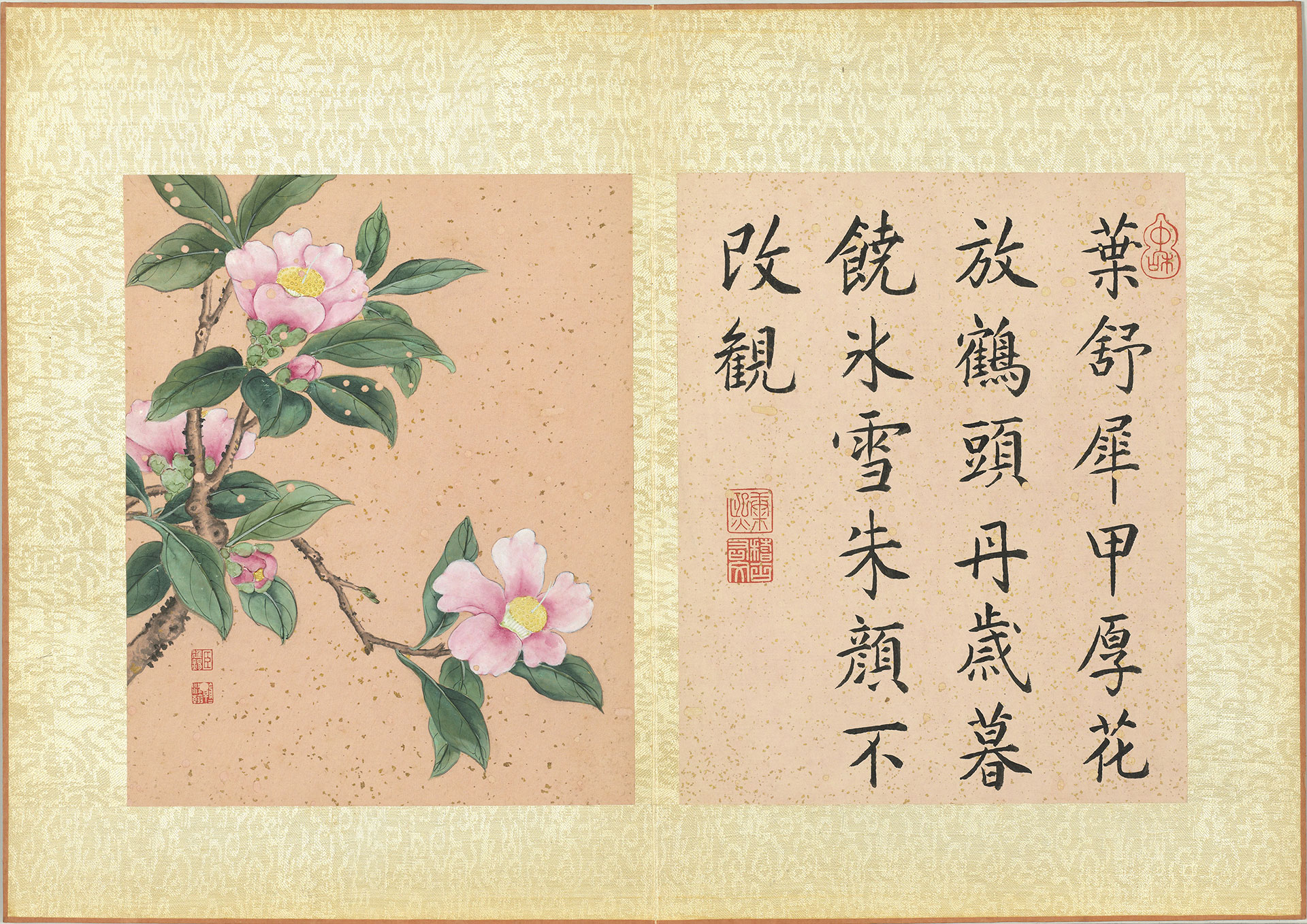

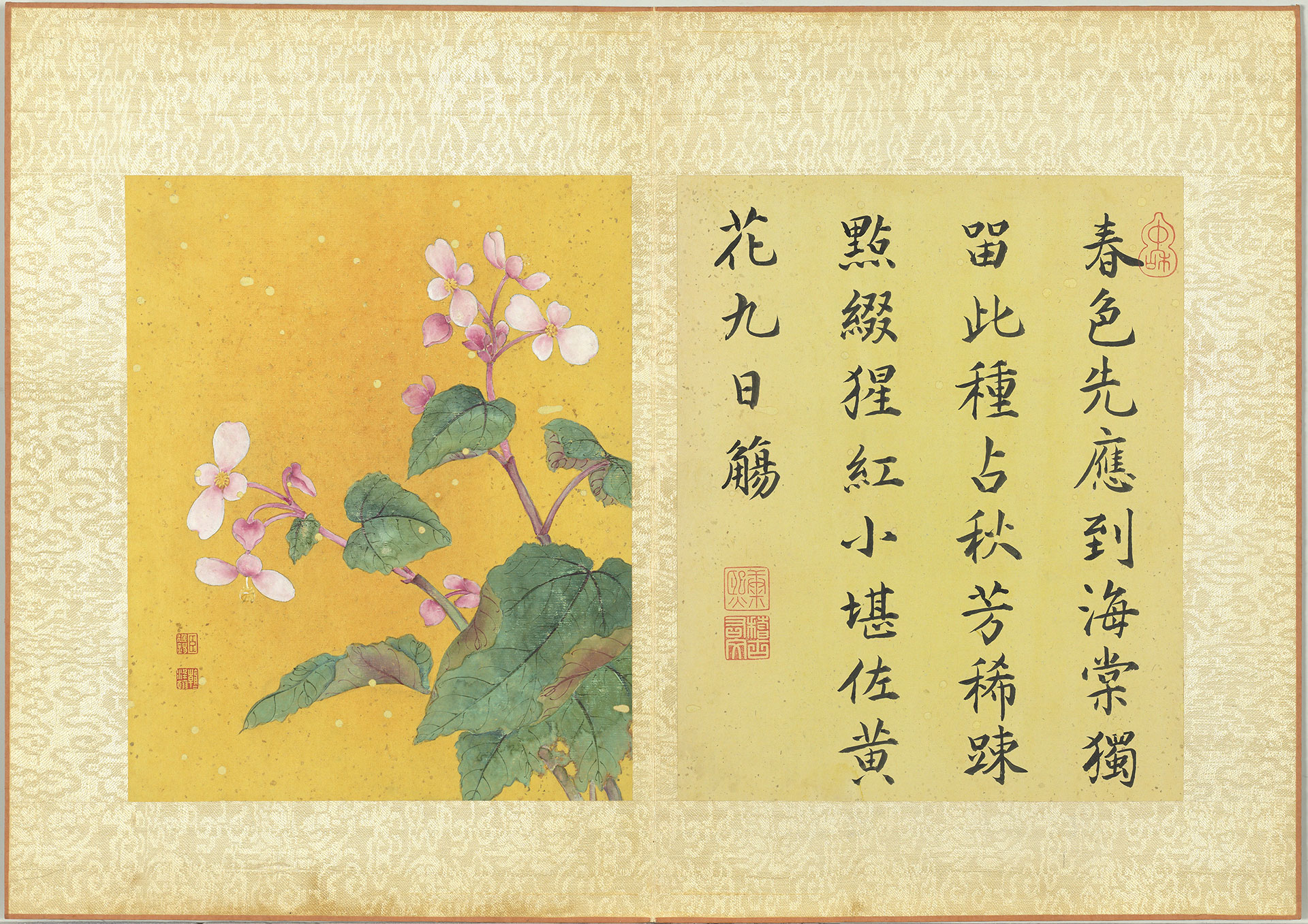

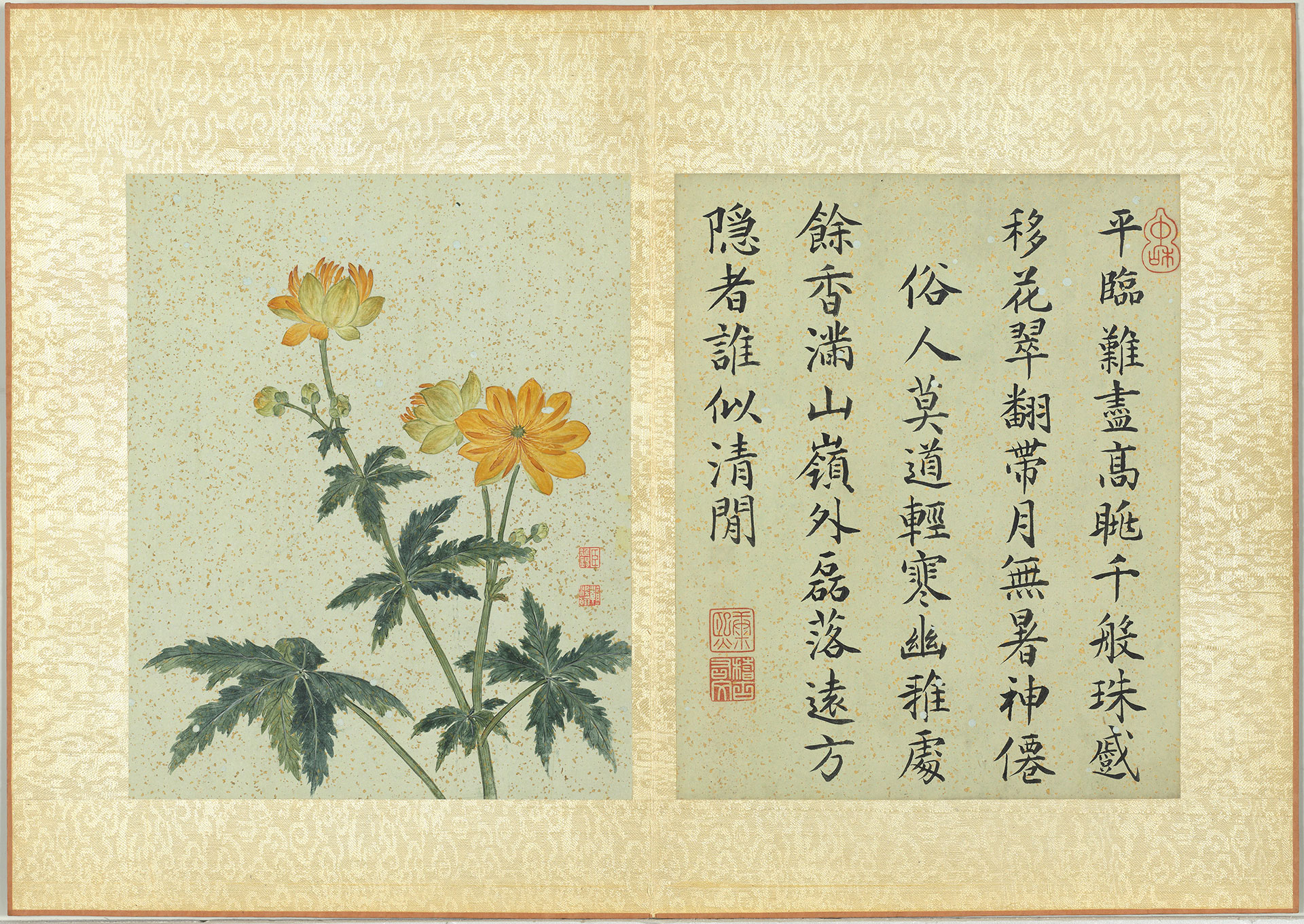

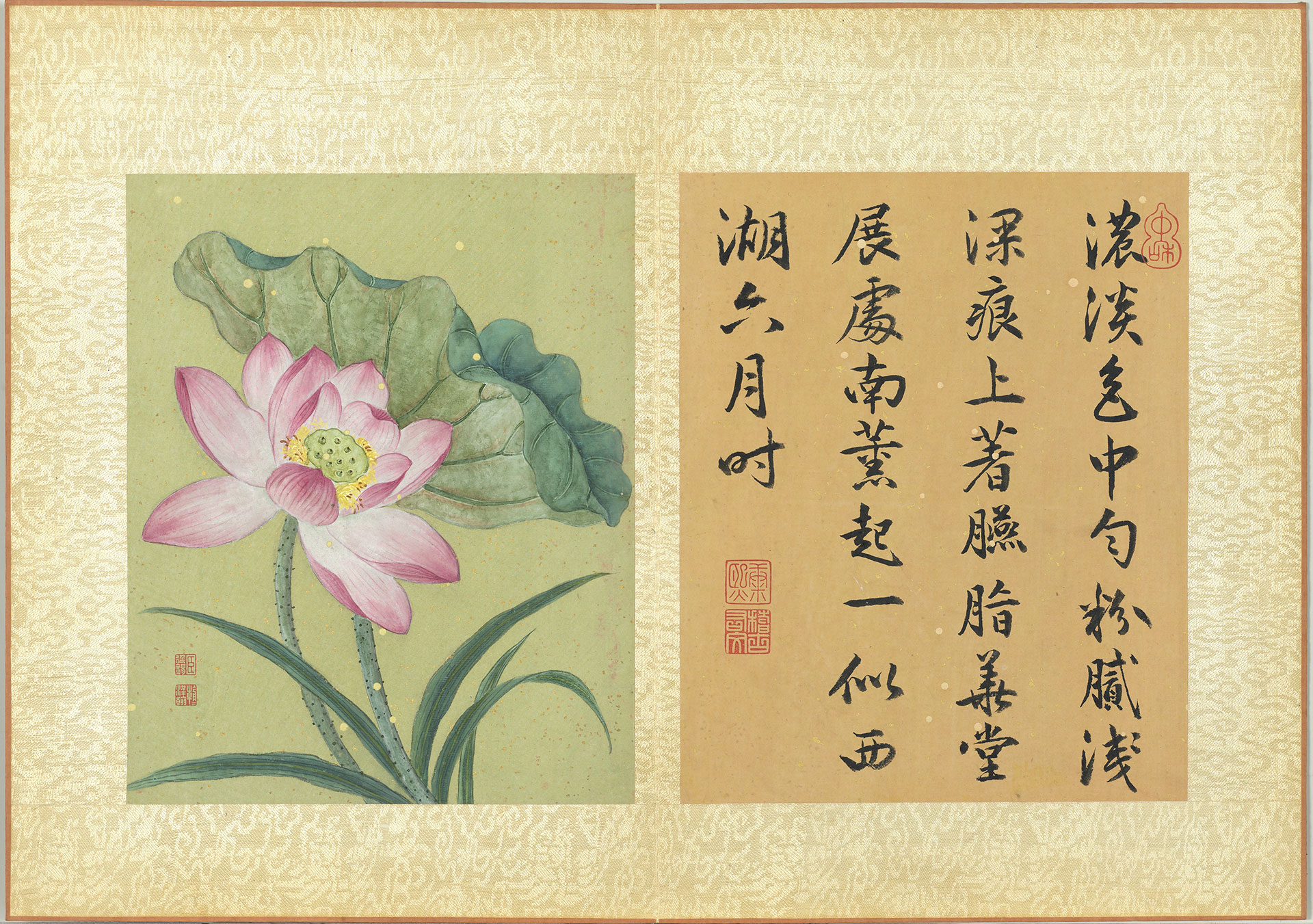

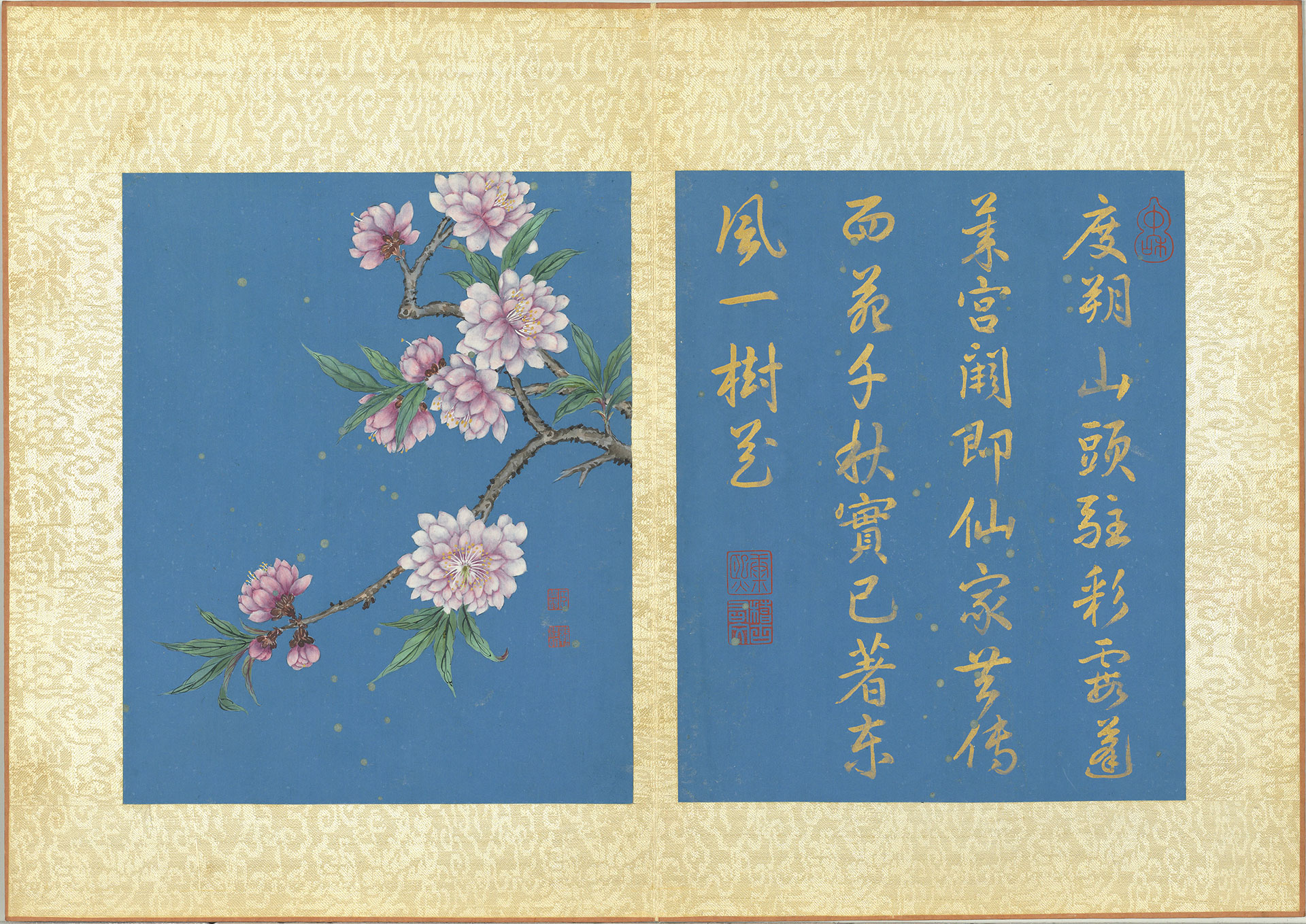

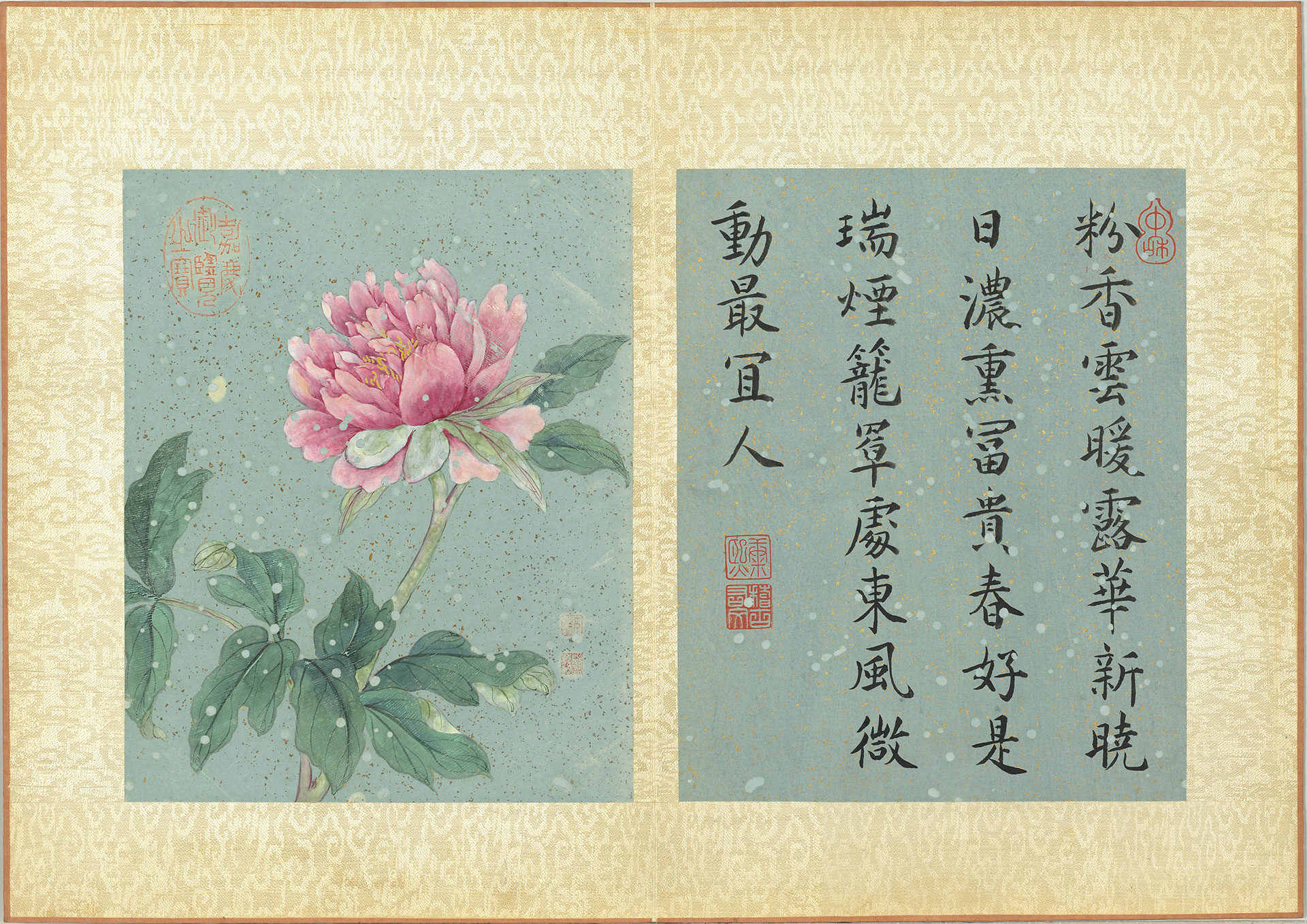

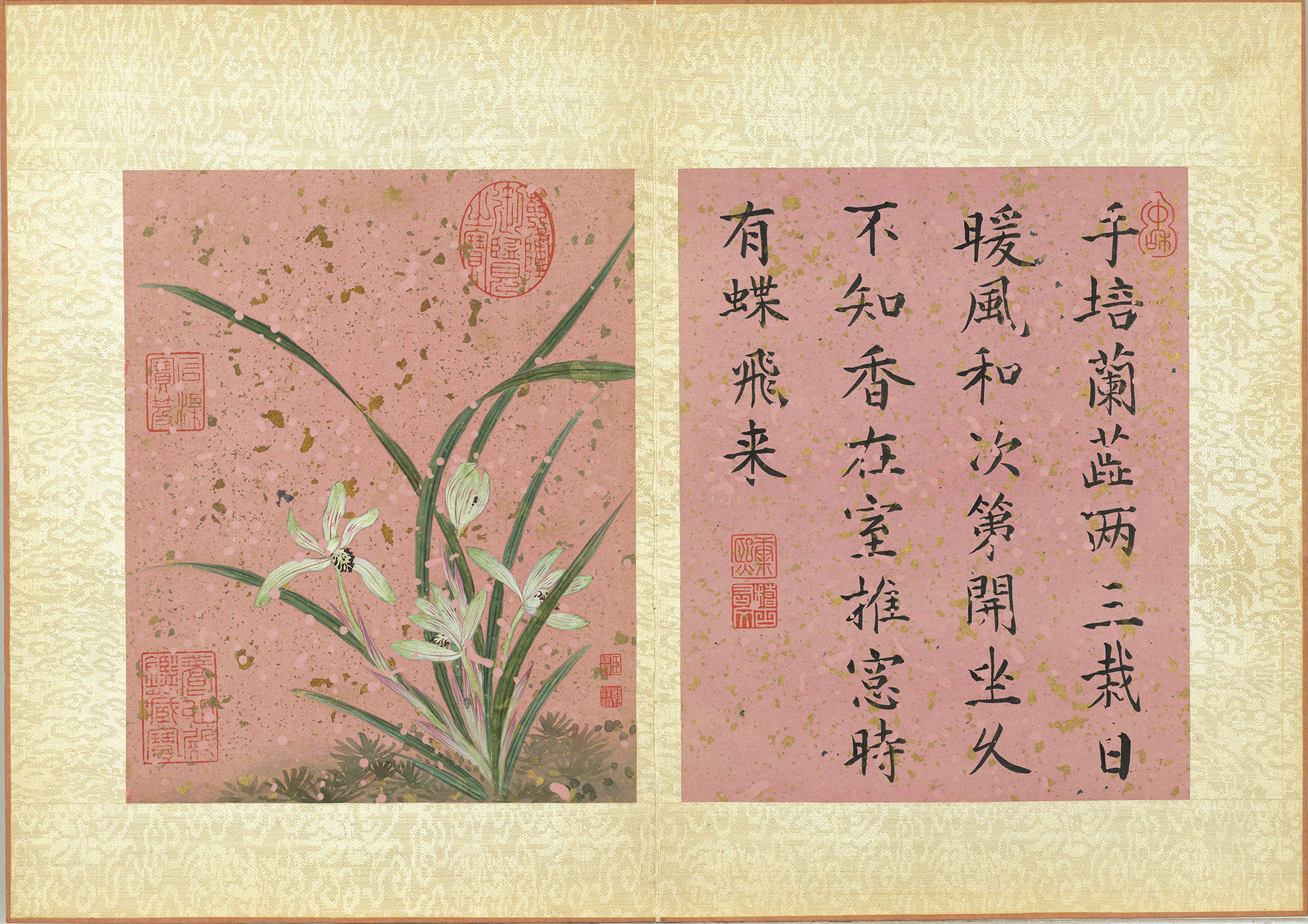

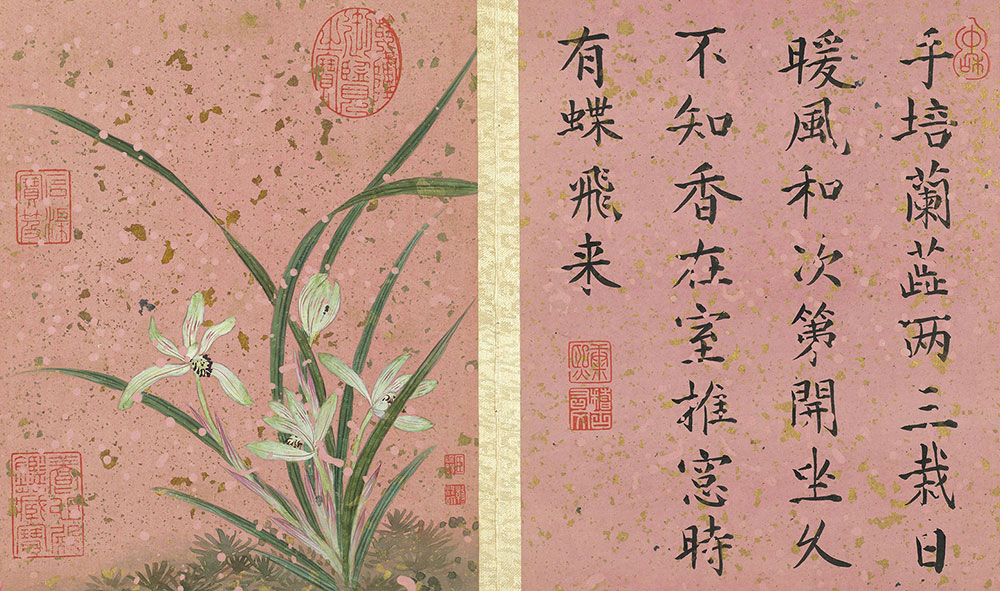

- Paintings and Poetry Devoted to the Countless Fragrant Flowers

- Jiang Tingxi, Qing dynasty

- Paper

Paintings and Poetry Devoted to the Countless Fragrant Flowers is an album consisting of twelve pieces of poetry and ci lyrics written calligraphically by Emperor Kangxi, combined with paintings of twelve different flowering plants painted by the emperor’s scholar-attendant Jiang Tingxi (1669-1732). As different colored paper was used as the base media for each of these paintings, the flowers and plants appear to have been colored in an especially rich and dazzling manner. The poems and ci lyrics are mostly yongwu poems (or “poems devoted to things”) from the Song and Ming dynasties. The fourth, seventh, and tenth leaves feature poetry composed by the emperor himself on the themes of golden lotus, China aster, and azaleas, which had been brought from southern China to the imperial gardens. Kangxi’s poems contain characters with double meanings—滿 means both “abundance” as well as “Manchu,” while 清 means both “clarity” and “Qing dynasty.” Kangxi also turned the flowers in these poems into metaphors for upstanding character, using pieces of verse devoted to flowering plants to praise the virtues of his officials.

Flowers from all over northern and southern China were included in this album, seemingly as though to say that both the newly-discovered plants from the far north, as well as the flowers from southern regions long considered significant by the Han people, were all products of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty.