Encyclopedic Research into Flowers

Almost any question about flowers or plants can be answered by consulting the Record of all Fragrant Flowers. Compiled during Emperor Kangxi’s reign, this floral-botanical encyclopedia contains the alternate names, growth habits, varietals, and histories of countless plants, in addition to poems and odes written about them by literati over the centuries. This text is thus one of the most important references for researching the poetry emperors and scholars wrote to praise the glory of flowers in bloom.

In response to the Qianlong Emperor’s (born Aisin-Gioro Hongli; 1711-1799) passion for connoisseurship and research, the scholar-attendants and artists in his retinue produced a great variety of paintings of flowers and plants. These artworks served as backdrops upon which the emperor displayed his talents for calligraphy and poetry, as he enjoyed himself by naming the flowering plants in the paintings or embellishing them with poetry written in his own hand.

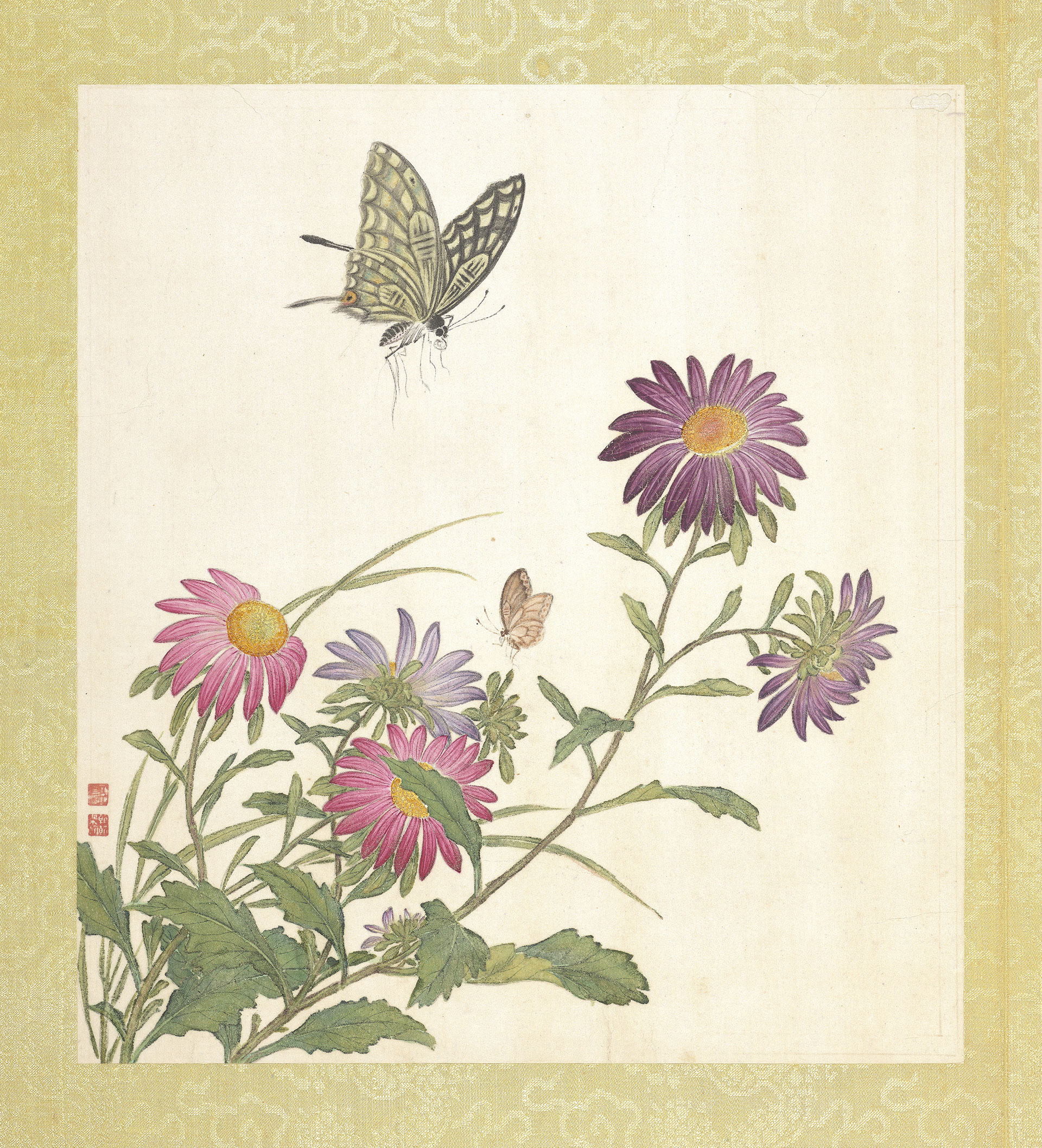

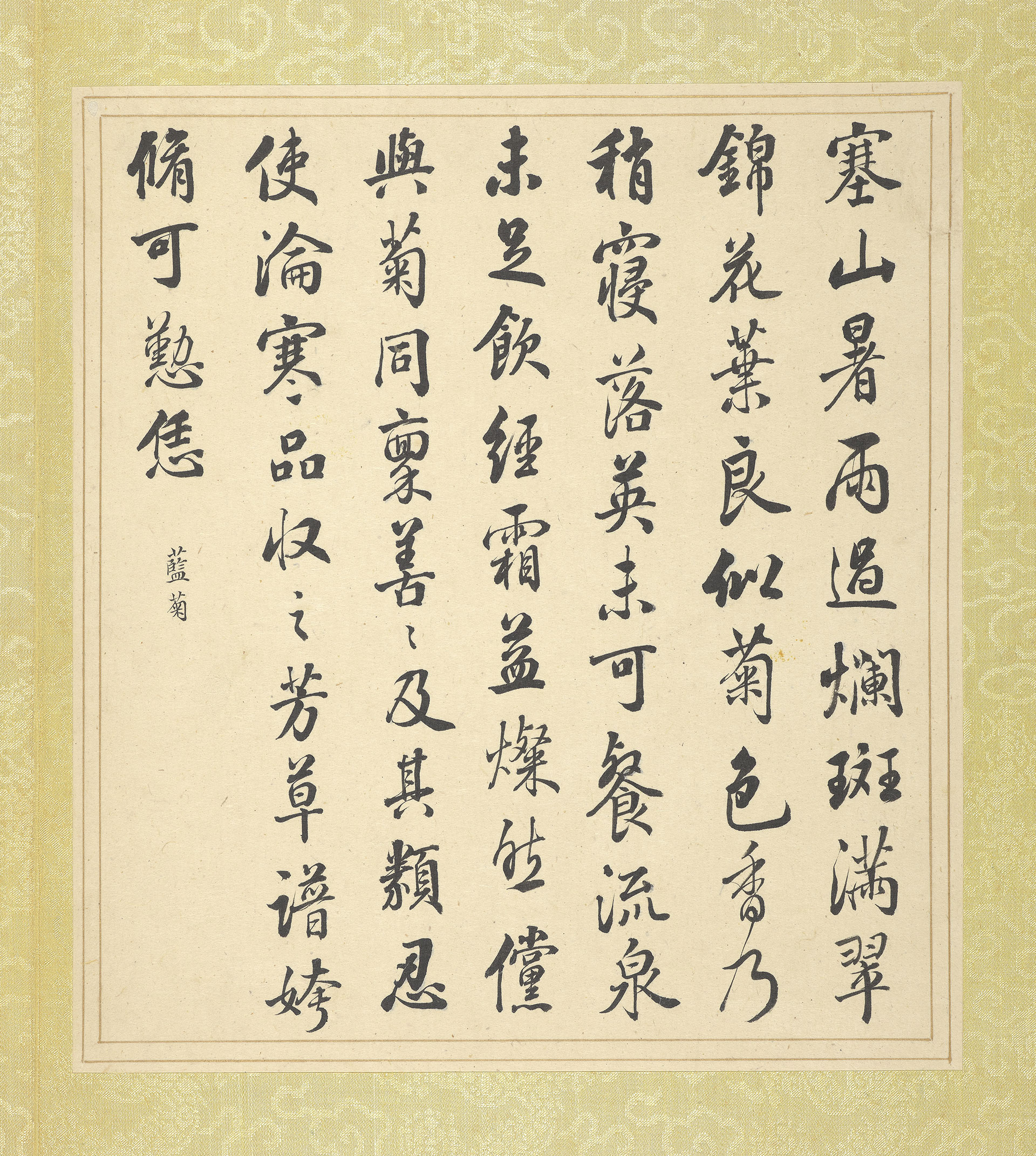

What color were the chrysanthemums growing north of the Great Wall?

During the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1654-1722) there began to appear paintings depicting bluish-purple chrysanthemums. The poems that accompanied these works always contained mentions of the region north of the Great Wall, and in fact, the chrysanthemums in these paintings were a unique plant endemic to that region. Not only did these flowers feature complex yellow-colored pistil-and-stamen structures that are different from the many-petalled chrysanthemum flowers typically seen in ancient artworks, they also lacked other chrysanthemums' tripartite leaves. Their overall appearances were quite similar to those of a diminutive plant, Indian aster (Kalimeris indica), which was also referred to as "purple chrysanthemum."

In his poetry, Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) referred to the "deep blue and pale purple" chrysanthemums from north of the Great Wall as "blue chrysanthemums" (a term for China aster or Callistephus chinensis) and expressed the belief that both flowers—one from the far north and the other from southern China—belonged to the same plant. Such statements reveal the opinions Qianlong held about different varieties of flowers.

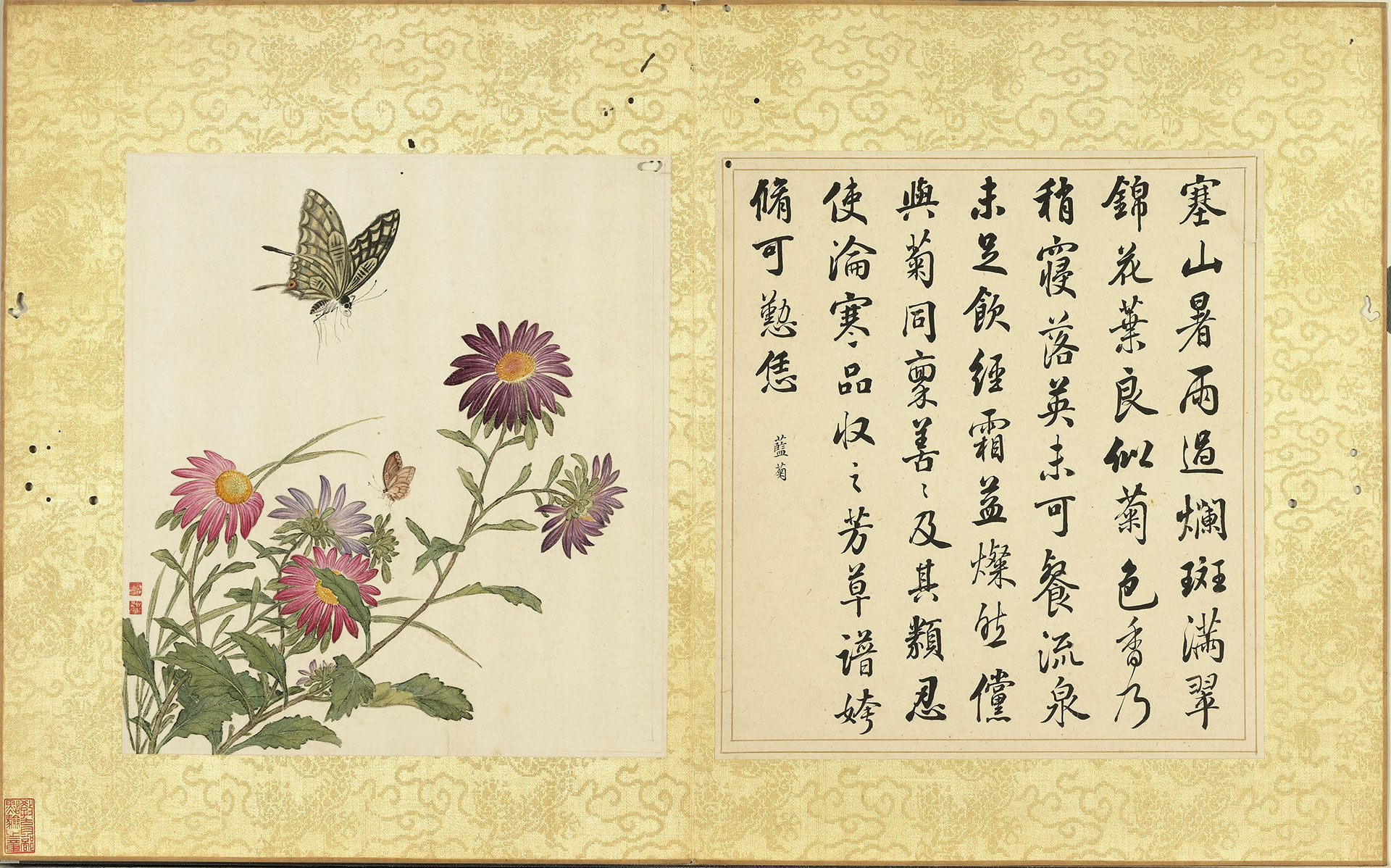

- Jiang Tinxi and Zhang Zhao, Qing dynasty

- Paper

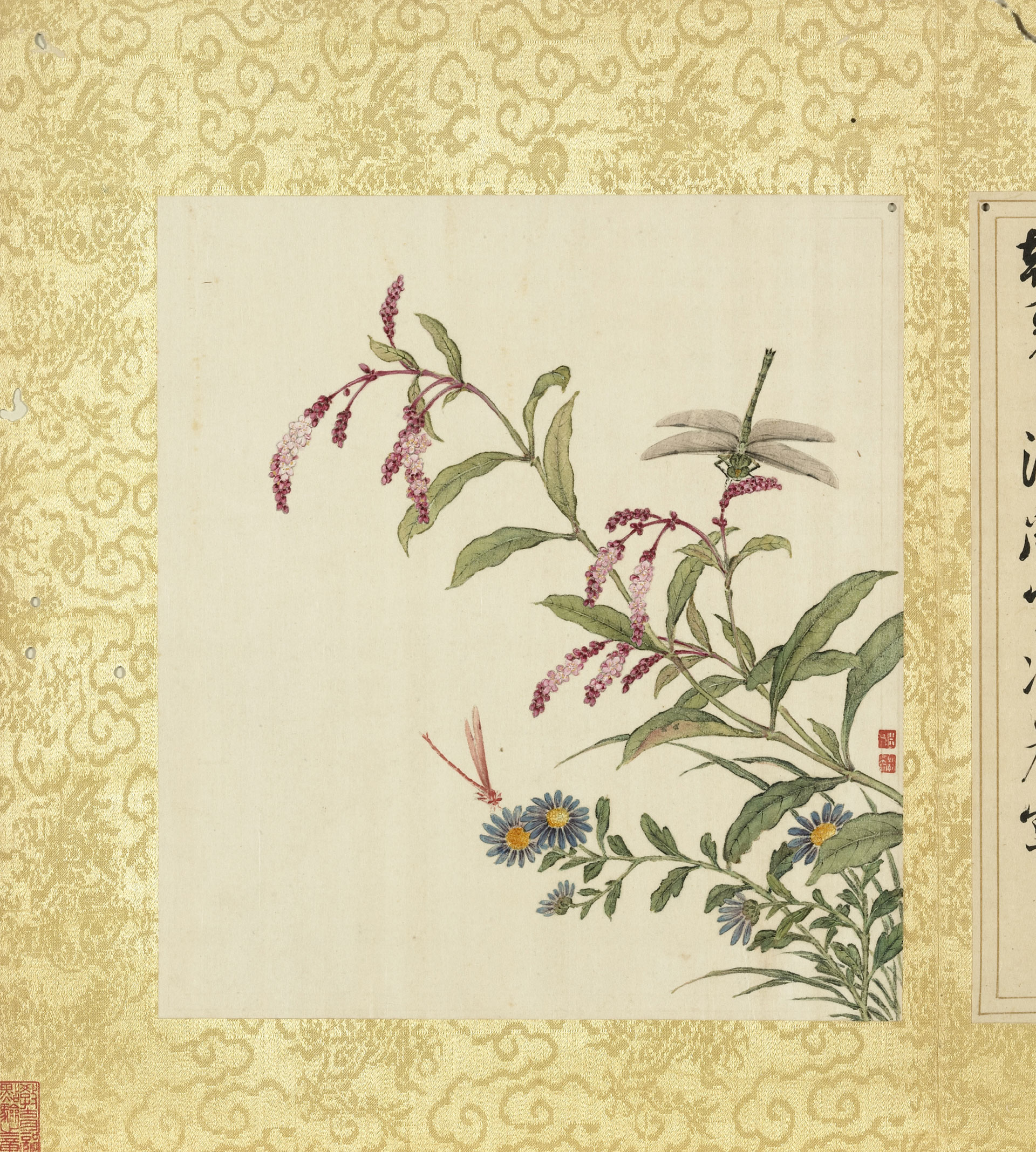

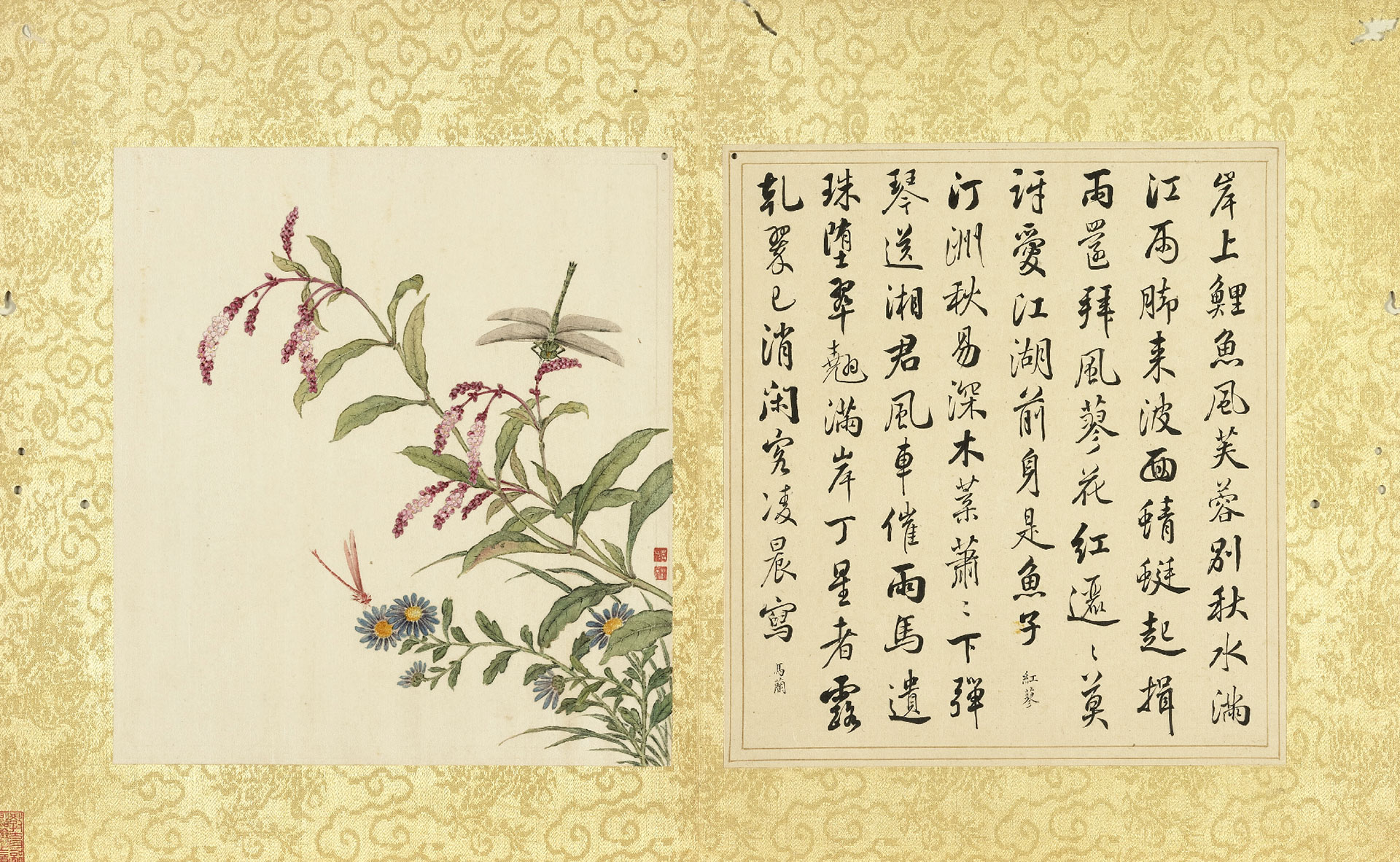

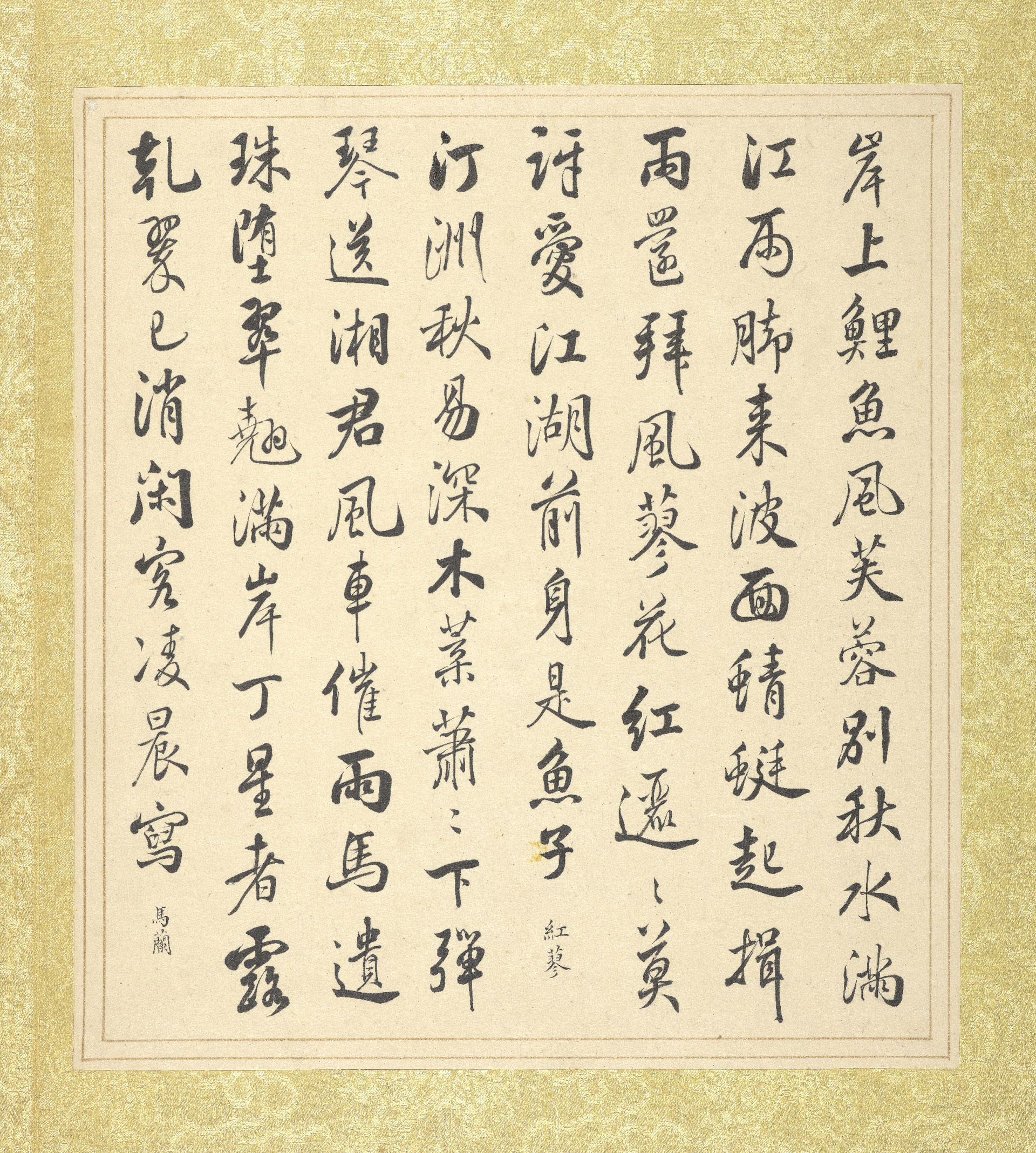

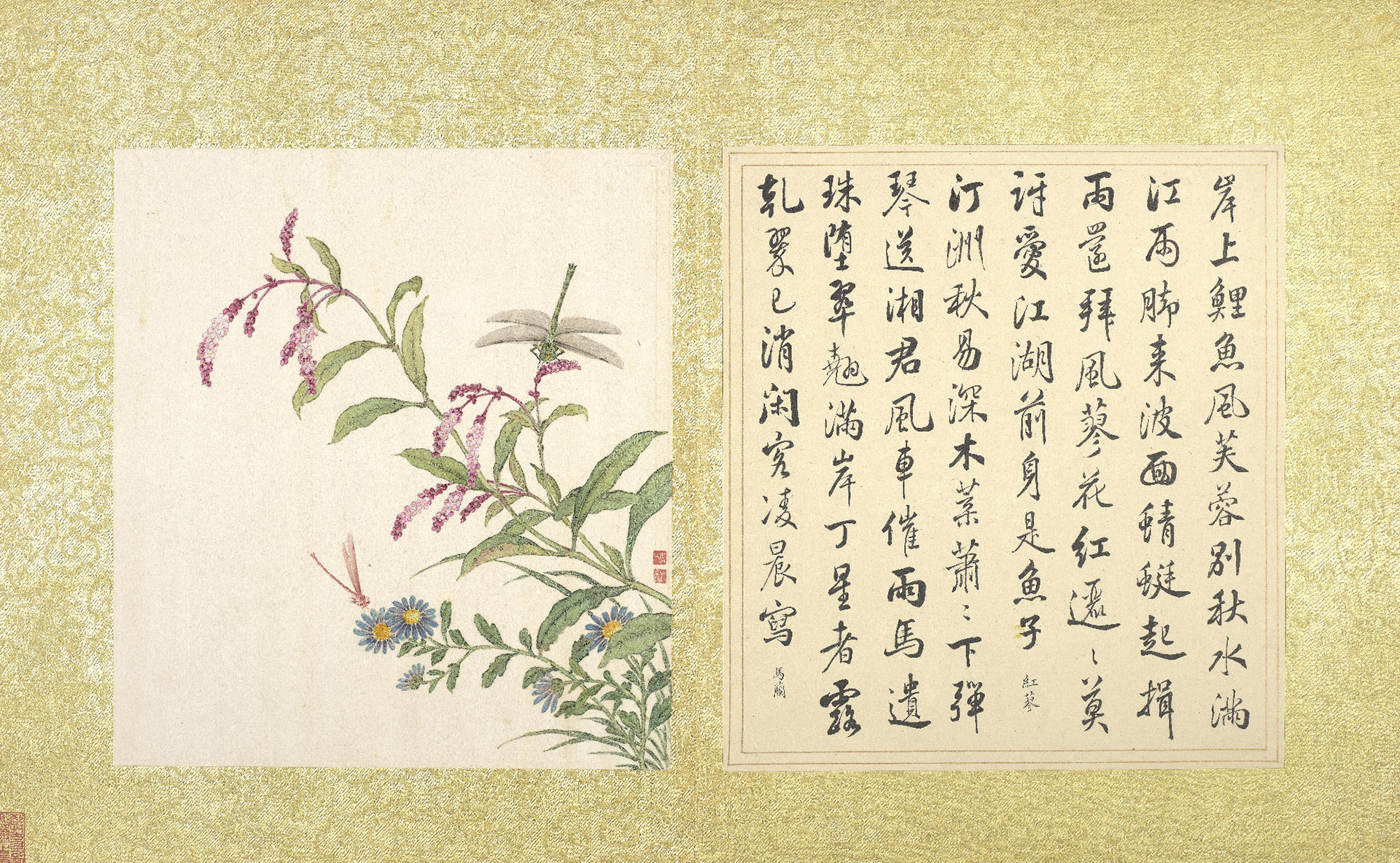

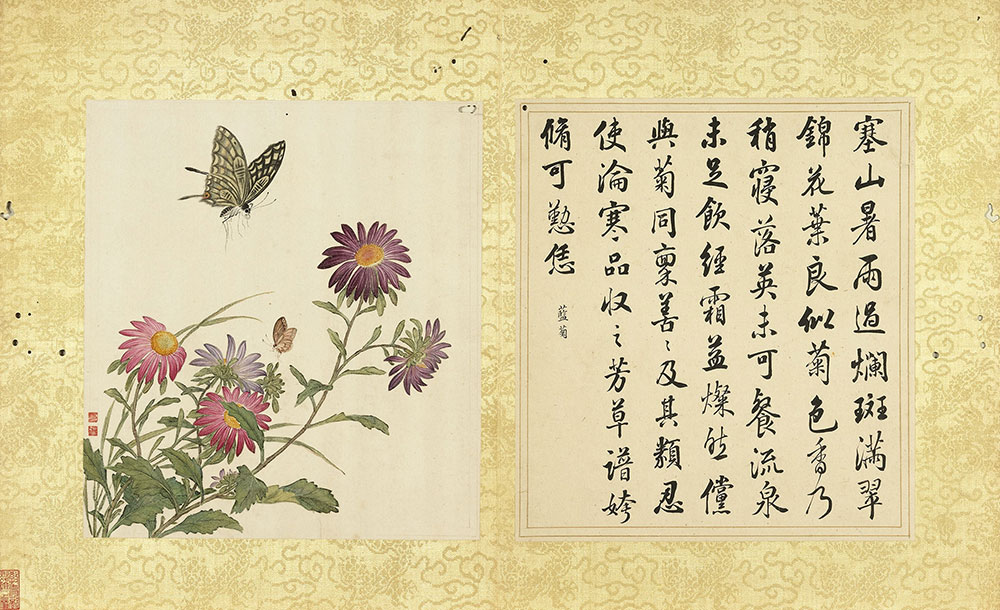

The left portion of each leaf in this album features flowering plants painted using the unoutlined “boneless” (mogu) technique on paper created from the rice-paper plant (Tetrapanax papyrifer). Each leaf’s right portion bears poetry written in calligraphy by the scholar-attendant Zhang Zhao (1691-1745) on specially prepared paper from the Korean peninsula that came to the Qing dynasty as imperial tribute. Both types of paper count as quite unique media. Paper from Tetrapanax papyrifer is made from the plant’s pith. It is very thin, and because of this any wrinkles on the paper’s surface are easily discerned. When the paper encounters moisture it swells and then shrinks, such that finished ink paintings can appear almost like shallow relief carvings.

Paintings depicting small, blueish-purple chrysanthemum flowers began to appear during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor. These plants are “blue chrysanthemums,” better known as China aster or Callistephus chinensis. The Record of All Fragrant Flowers notes that they are “blue-green and yet purple”—these blossoms’ coloration generally lies somewhere between blue and purple, but there are also varietals with different coloration, including red and white. The similarly-shaped, bluish-purple plant depicted in the other leaf is Indian aster (Kalimeris indica), a relatively smaller plant that likes to grow in moist, humid areas.

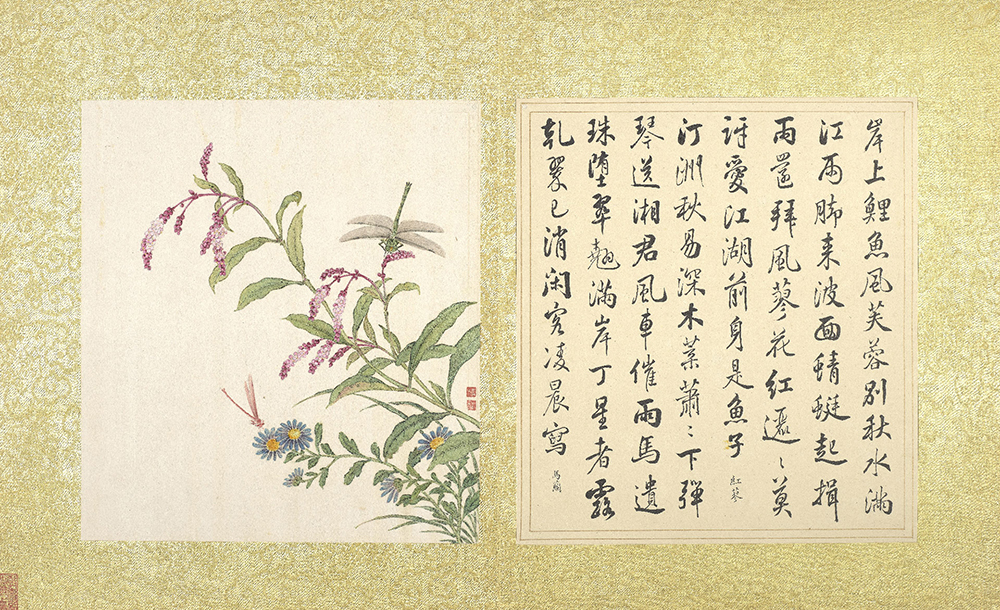

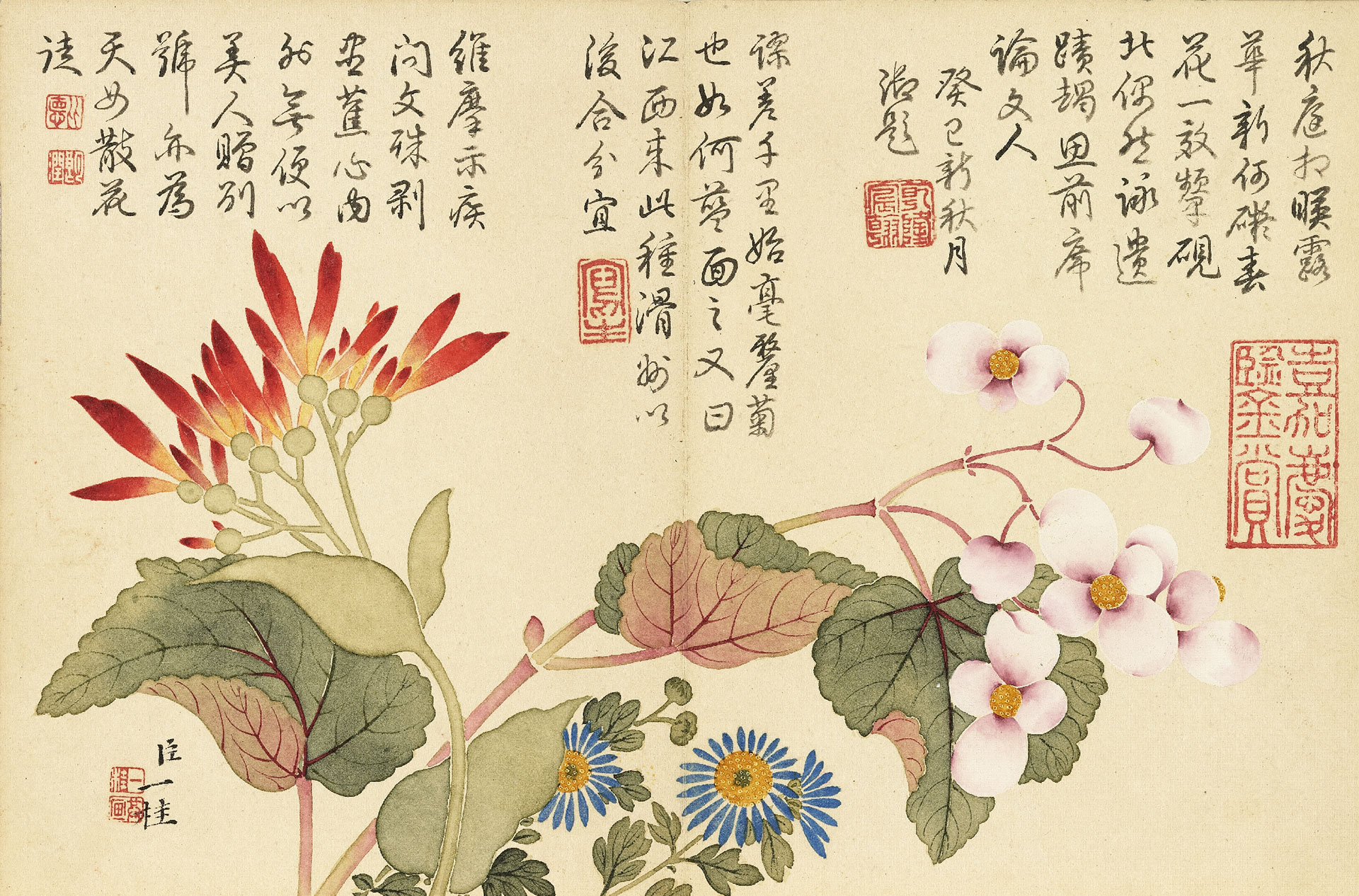

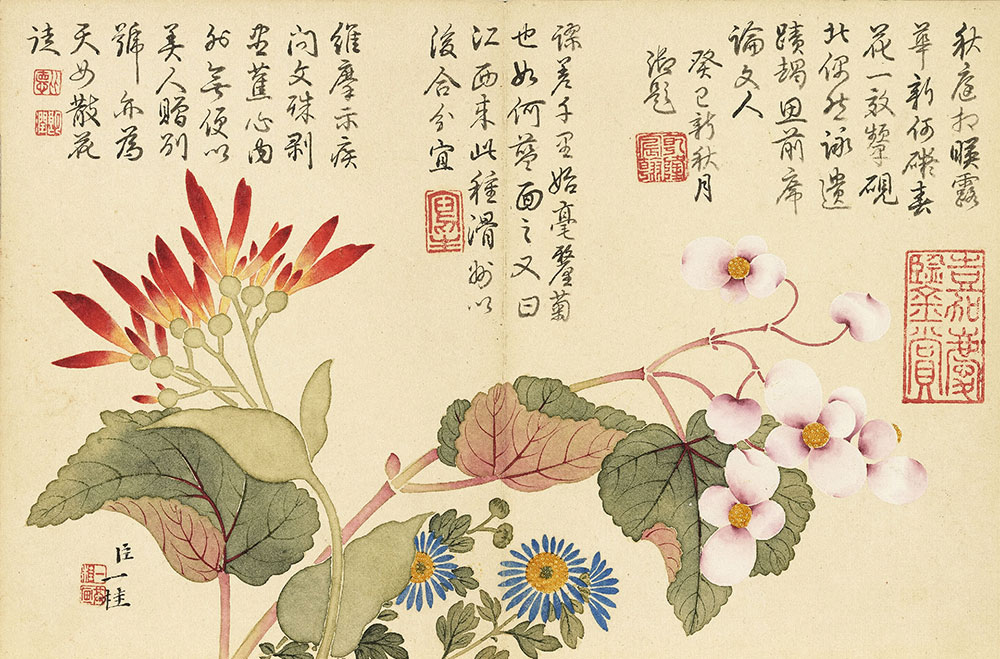

- Flowering Plants (Canna Lily, Begonia, and China Aster)

- Zou Yigui, Qing dynasty

- Paper

This painting, which is a selection from Zou Yigui’s (1686-1772) album entitled Flowering Plants, depicts three autumnal flowers in full bloom: Canna Lily, begonia, and China aster. Qing dynasty emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) wrote poetry in the upper portion of the painting, completing the calligraphy on the anniversary of Zou’s passing (1773). In that year Emperor Qianlong collected all of the paintings Zou had offered as tributes to the imperial court. He then inscribed poetry in their empty margins in memory of the deceased artist.

In 1758, Zou Yigui wrote Annotations on My Paintings of the Foothills, in which he made note of his observations of various flowering plants, as well as the insights he gained from painting them. In this short treatise, he recorded that both “blue chrysanthemum” (or China aster, which he referred to as being from Jiangxi province) and Indian aster (Kalimeris indica) both had purple blossoms. However, Emperor Qianlong concluded that the blue-colored chrysanthemum in this painting must be China aster, in disagreement with the artist himself. From this we can see how Qianlong held strong opinions about the classification of different species of flowering plants.

- Flowering Plants of the Four Seasons (China Aster)

- Qian Weicheng, Qing dynasty

- Paper

Qian Weicheng (1720-1772) passed the imperial examinations in the tenth year of Emperor Qianlongs’ reign (1745), obtaining the title zhuangyuan, indicating that he placed first among those in the top rank of “presented scholars.” He learned to paint flowers and plants from Chen Shu (1660-1736), who was a female elder in his extended family. This painting portrays three blue-colored chrysanthemum blossoms. Their stalks and leaves are depicted in toto, and their petals appear symmetrical and evenly distributed, conveying an idealized vision of how these flowers might appea.

Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) compared blue chrysanthemum to Lu Qi (?-785), a treacherous minister in the Tang Dynasty, who was "ugly in appearance and blue in color", but his father Lu Yi (?-755) was a loyal minister. Therefore, the emperor lamented, "Why bother to blame the flowers?" and believed that the blue chrysanthemum should not be blamed for its color.