Findings from Beyond the Great Wall

The Kangxi Emperor (born Aisin-Gioro Xuanye; 1654-1722) was a Manchu emperor endowed with an adventurous and investigative spirit. On numerous occasions he led his entourage of ethnically Han scholar-attendants north of the Great Wall in order to personally oversee comparative studies of the differences between the climate, plants, and animals in that region and those of the empire’s southern reaches. Kangxi intended for the results of these exploratory expeditions to be included in the official imperial records, thereby giving rise to a new system of knowledge unique to the Qing empire.

In addition to appreciating the scenery and flora and fauna they laid eyes upon during their excursions, the retinues of scholar-officials who accompanied the emperor also produced firsthand written and illustrated records of their observations. The various wild plants and flowers that previously escaped notice due to their geographic inaccessibility were etched into the emperor and his scholar-attendants’ memories, and thereupon became novel subject matter in the painted and calligraphic creations of Qing dynasty court artists.

Flowers-and-plants Paintings Through the Centuries

Because most flowering plants grow in such a way as to face the sun, the Northern Song dynasty court painter Guo Xi (ca. 11th century) recommended standing directly above such plants and looking down upon them, so as to be able to observe their flowers’ appearances in their entirety. Nevertheless, once a painter has captured a flowering plant’s appearance with his or her eyes, how does the painter then depict its three-dimensional form on a flat piece of paper or silk?

Please take a look at the ways the Song, Ming, and Qing dynasty painters in this exhibition allowed the flowering plants they observed to come to life in their paintings!

- Cat Beneath the Flowers of Wealth

- Anonymous, Song dynasty

- Silk

In this painting, a cat leashed to a stone bell by a red cord crouches beneath a blooming peony bush. Peonies often appear as symbols of wealth in Chinese art, while the Chinese character for “cat” rhymes with “elderly,” thus imbuing this work with tidings of prosperity and longevity. The peony flowers are painted as buds, partially unfurled, and in full bloom, revealing this plant’s blossoms at each stage of their growth. The enormous size of the flowers and the way in which small purple petals are interspersed with the white petals and yellow stamens indicate that this is a special varietal of peony.

The silk this work was painted upon is quite pale in coloration at its left and right edges, suggesting that it may once have been displayed as part of a room divider screen. In his Dream Pool Essays, Shen Kuo (1029-1093) once wrote of seeing a painting featuring peonies and a cat, and concluding from the wide-open flowers and the constricted pupils of the cat’s eyes that the painting depicted the scenery of high noon. Shen’s anecdote reflects the minute observation and exacting precision that characterize Song dynasty painting.

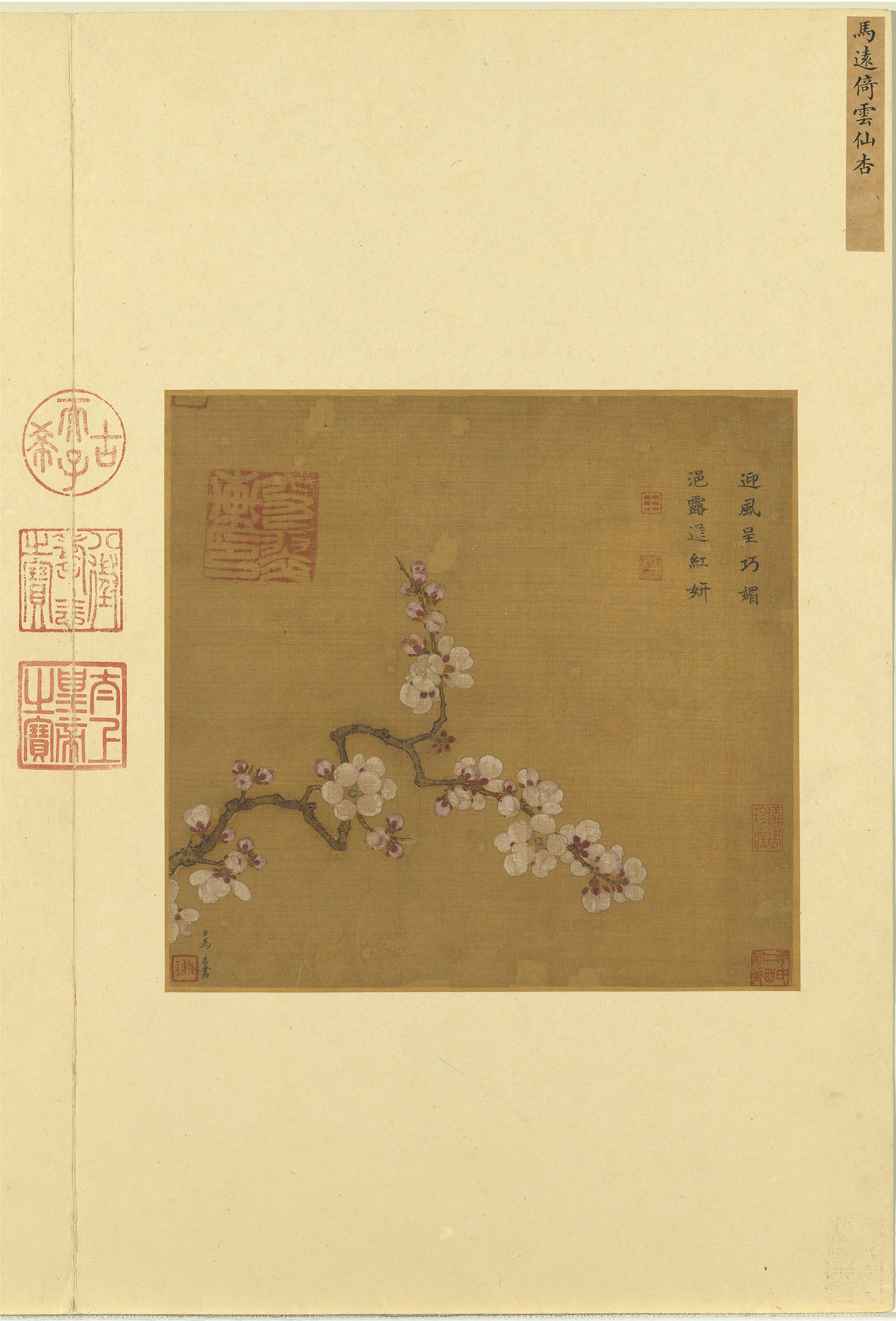

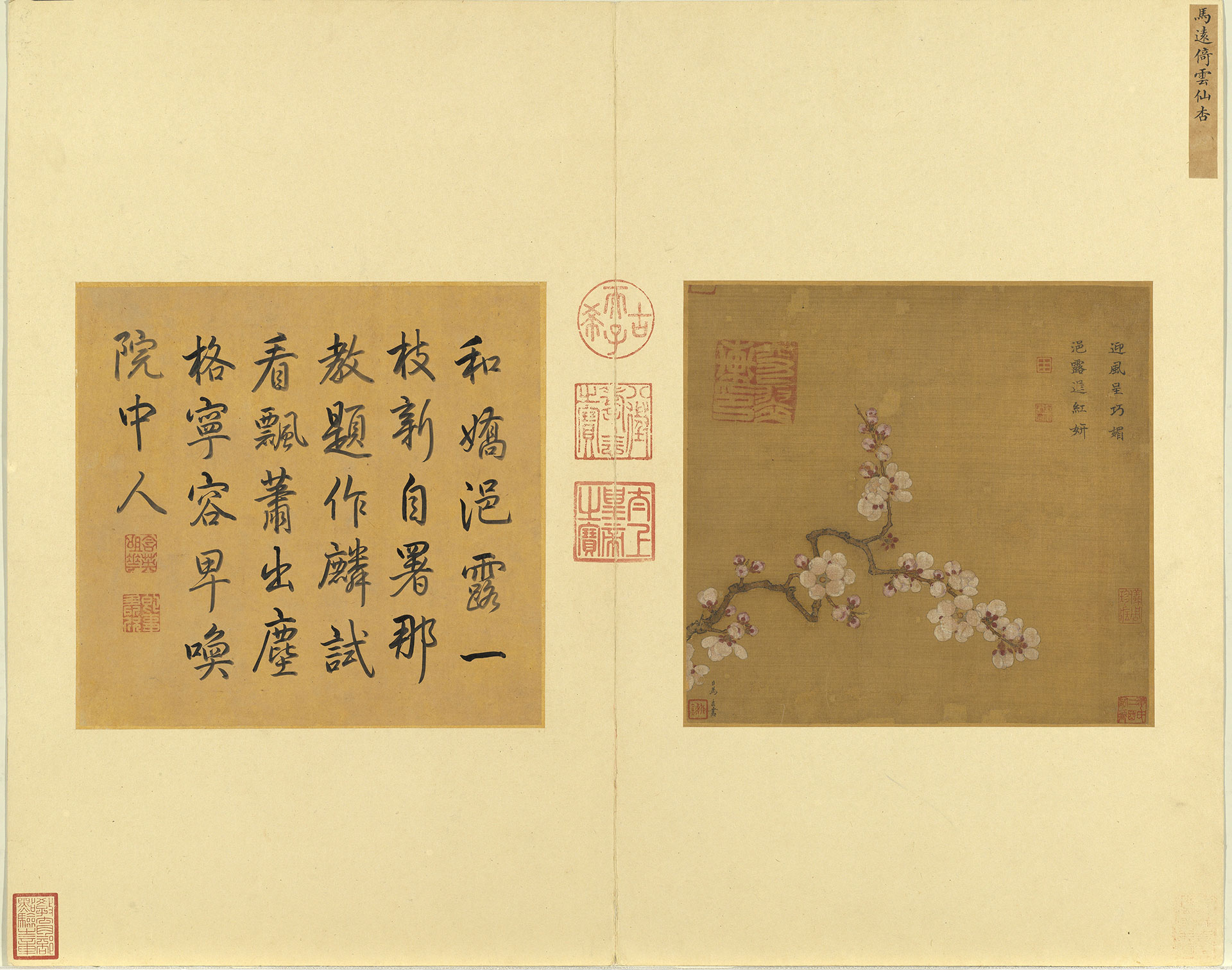

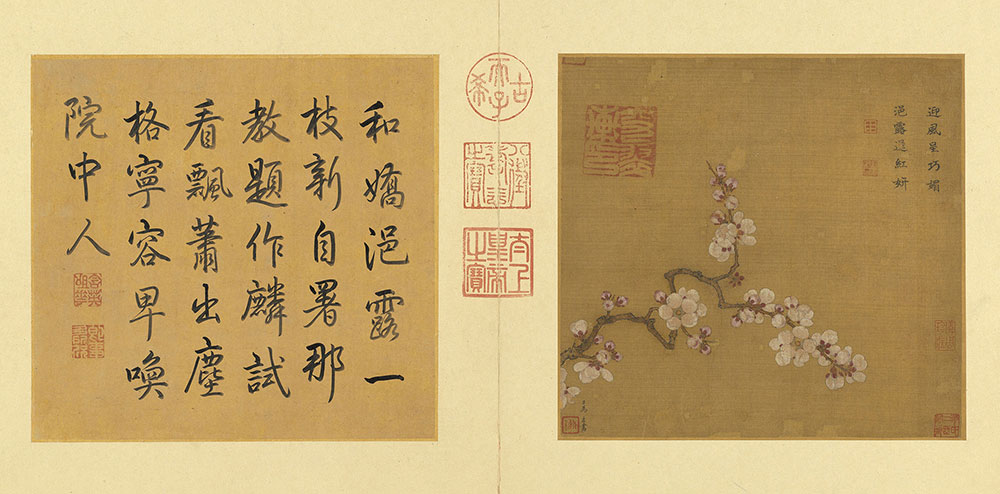

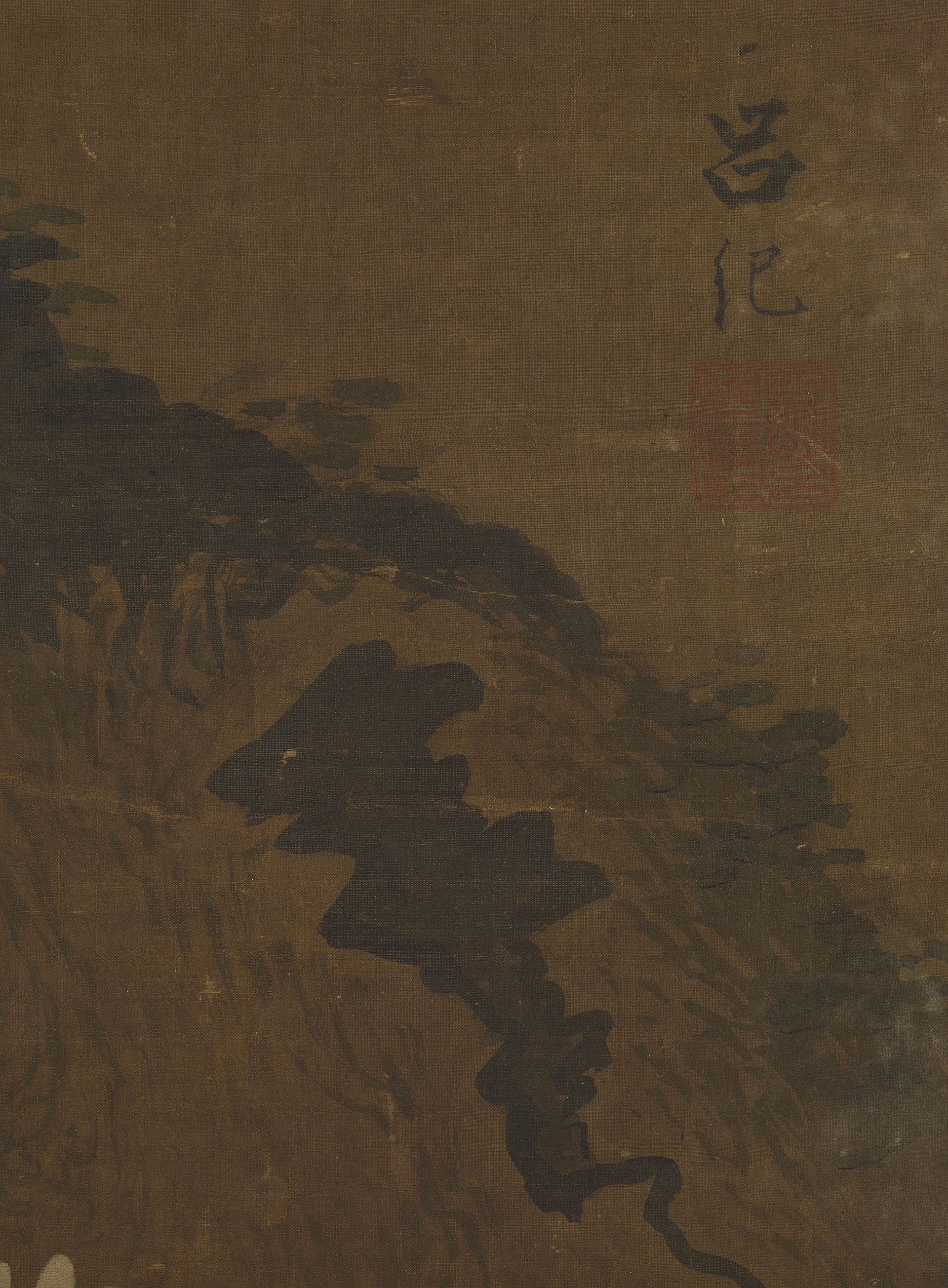

- Apricot Blossoms Leaning Against the Clouds

- Ma Yuan, Song dynasty

- Silk

In its lower left corner, this work features a signature that reads, “Painted by your servant Ma Yuan.” Ma Yuan (12th-13th centuries) was a Southern Song dynasty court painter. In this piece, Ma refrained from painting the branch in its entirety and adding a background. Instead, he simply emphasized the shapes and forms of these flowers on a small part of the tree. The apricot blossoms can be seen at different stages of their life cycles: as they bud, as they come into full bloom, and as they gradually wither away.

The upper right portion of this painting features a poetic inscription in small regular script written by Empress Yang (1162-1233), which reads, “Welcoming the breeze with coquettish charm, its beauty is accented by the moistness of the dew.” Next to it appear two seal imprints, one reading “Kun trigram” (a symbol for yin and femininity from the Book of Changes), the other stating, “Calligraphy by Madame Yang.” She likely wrote this calligraphy in the second year of her husband Emperor Ningzong’s Jiatai reign period (1202), after being conferred the title of empress.

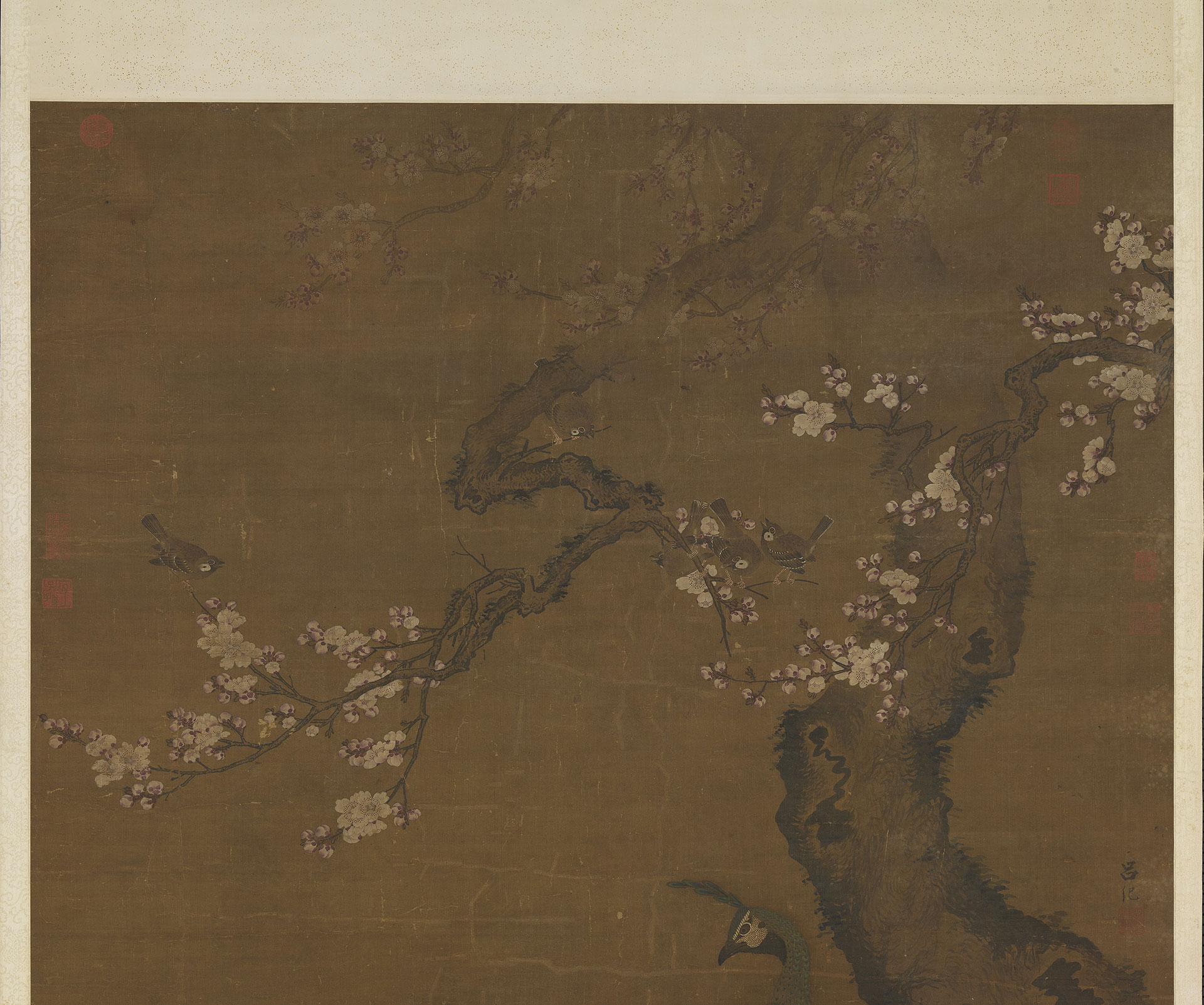

- Apricot Blossoms and Peacocks

- Lü Ji, Ming dynasty

- Silk

Lü Ji (1477-?) was a Ming dynasty court painter. One of the peacocks in this painting stands one-legged atop a huge scholar’s stone, with peonies and apricot blossoms in full bloom just behind it—it’s possible that the scene is actually a painting of a location in one of the imperial gardens. Mists coil near the top of the apricot tree in a style inherited from Southern Song dynasty court painting. Ming dynasty court painters paid careful attention to combinations of flora and fauna that evoke auspicious hidden meanings. For instance, the second half of the Chinese word for “peacock” rhymes with a word meaning “nobility,” a point that lets this work allude to high rank and official salary.

The flowers and birds in this piece were portrayed using incredibly exacting gongbi painting techniques, whereas the tree and stone were depicted with rather coarse and unrestrained use of brush and ink—this variation fills the painting with a compelling contrast between refined and untrammeled brushwork. The compositional approach of alternating between fine brushwork for a painting’s main subject matter and coarser brushwork for its background continued to be used by court painters in the Qing dynasty.