The Splendor of Court Editions

In addition to collecting books from previous dynasties and using it to promote cultural undertakings, the Ming and Qing courts were also active in compiling and printing court editions. The governments ran offices dedicated to these tasks, and the Silijian (Directorate of Ceremonial) of the Ming and the Xiushuchu (Book Compilation Department) of the Qing at the Wuyingdian (Hall of Martial Glory) functioned very much like state publishing houses. Elegantly decorated and luxuriously bound, these court editions are rich in historic and artistic value, and represent the epitome of book production in historical China. This section showcases important editions produced by the Ming and Qing courts and works written by emperors, with original binding and decoration. It hasn't only shown the actual case of the spread of copied rare books, but also included individual titles in different phases of revision and production, revealing that they had been given a more delicate, subtle meaning, which in turn reflected the uniqueness of the imperial system of rites.

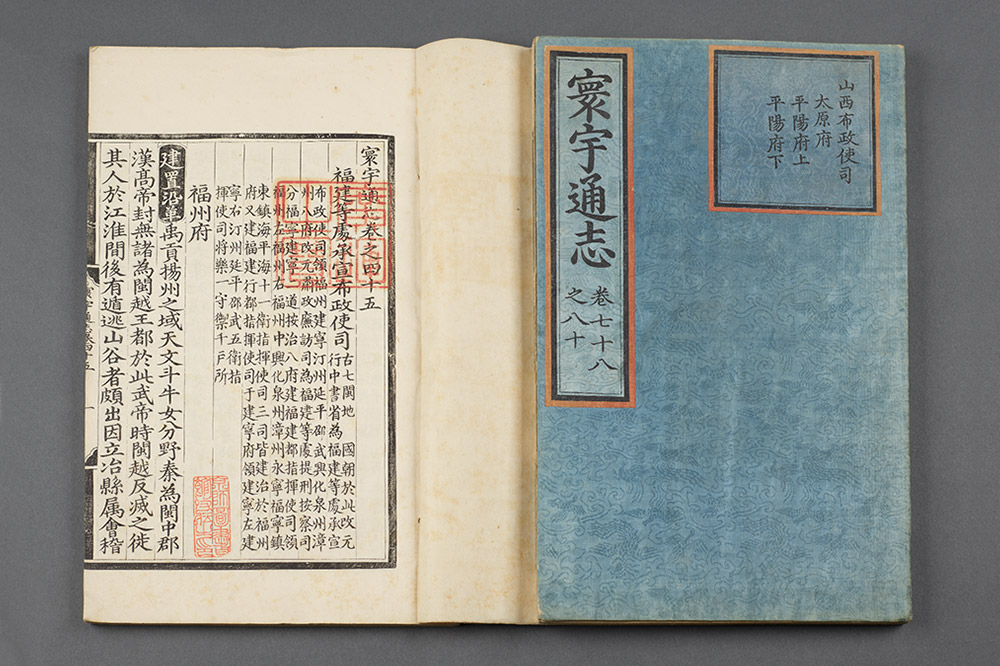

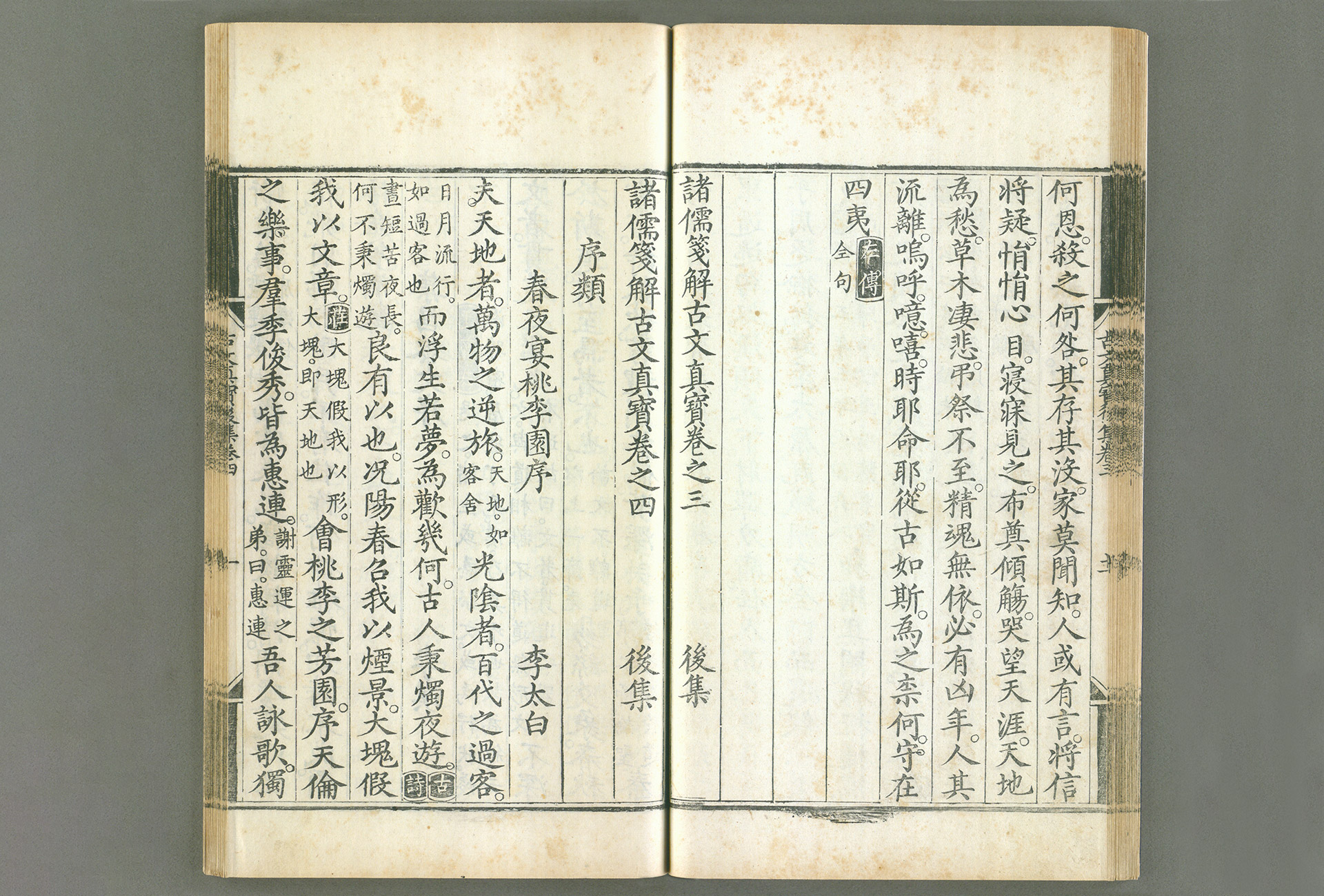

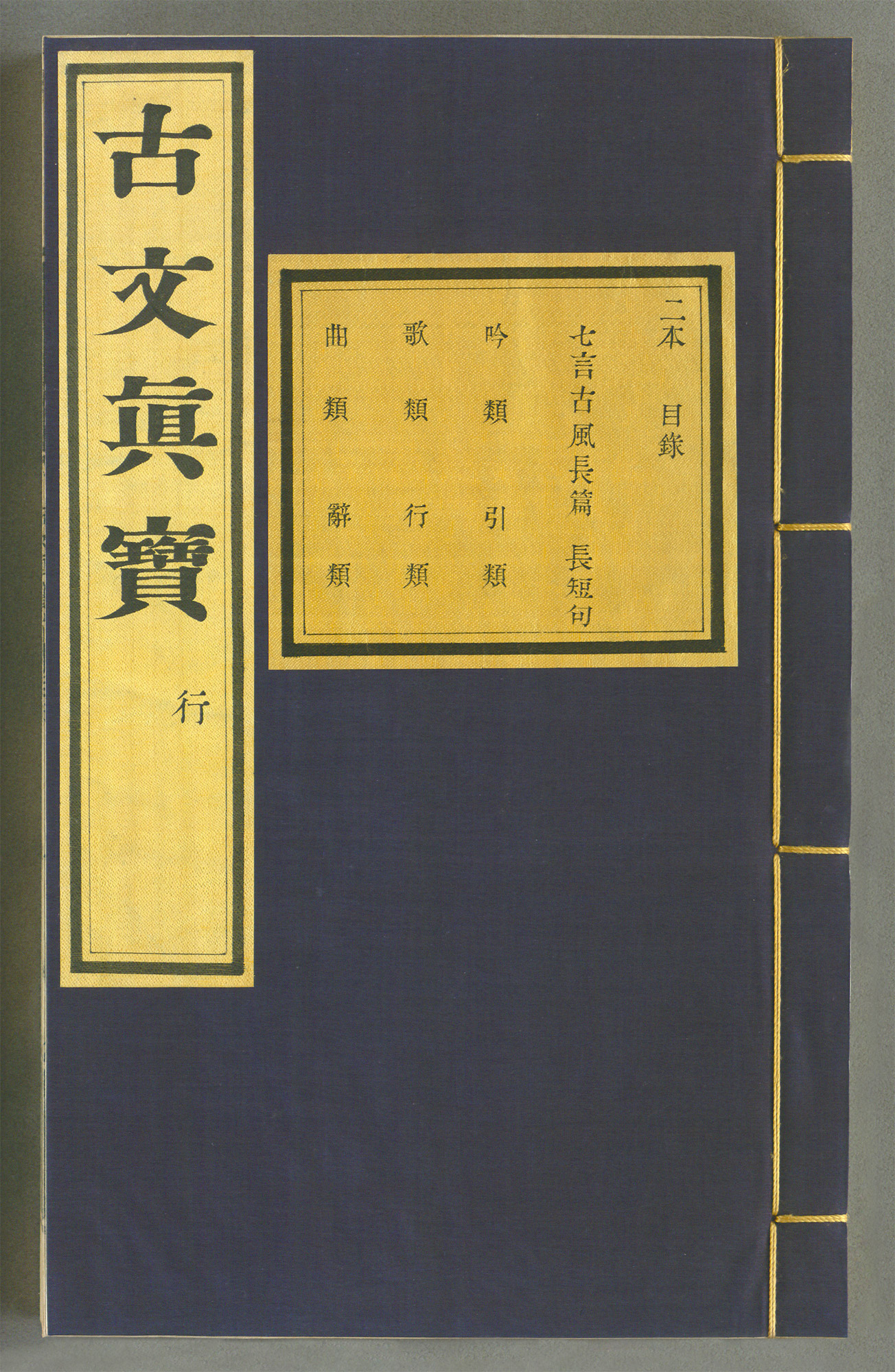

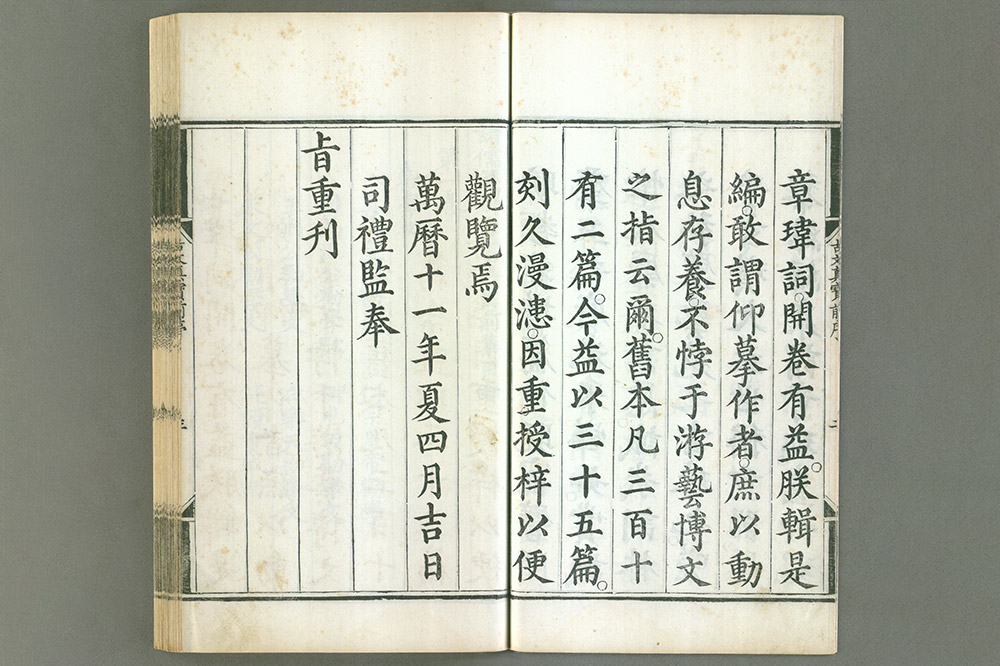

The Directorate of Ceremonial was originally an internal service organization in charge of court etiquette in the early-Ming dynasty. Since 1409, it was decreed by emperors to engrave books and maintain imperial storehouse book boards. The Directorate of Ceremonial had more than 300 types of engraved books, most of which were used to maintain governance through culture and education. For example, the Annotated Explanations by Various Confucianists–True Treasure displayed here is a must-read for Ming dynasty imperial family members when studying poetry and compositions. The Hongzhi Emperor was particularly fond of it, stating that he did not care about gems and treasures and urged people not to bring them to him. Instead, he cherished the values of books because he could read them repeatedly and be inspired by their principles and wisdom.

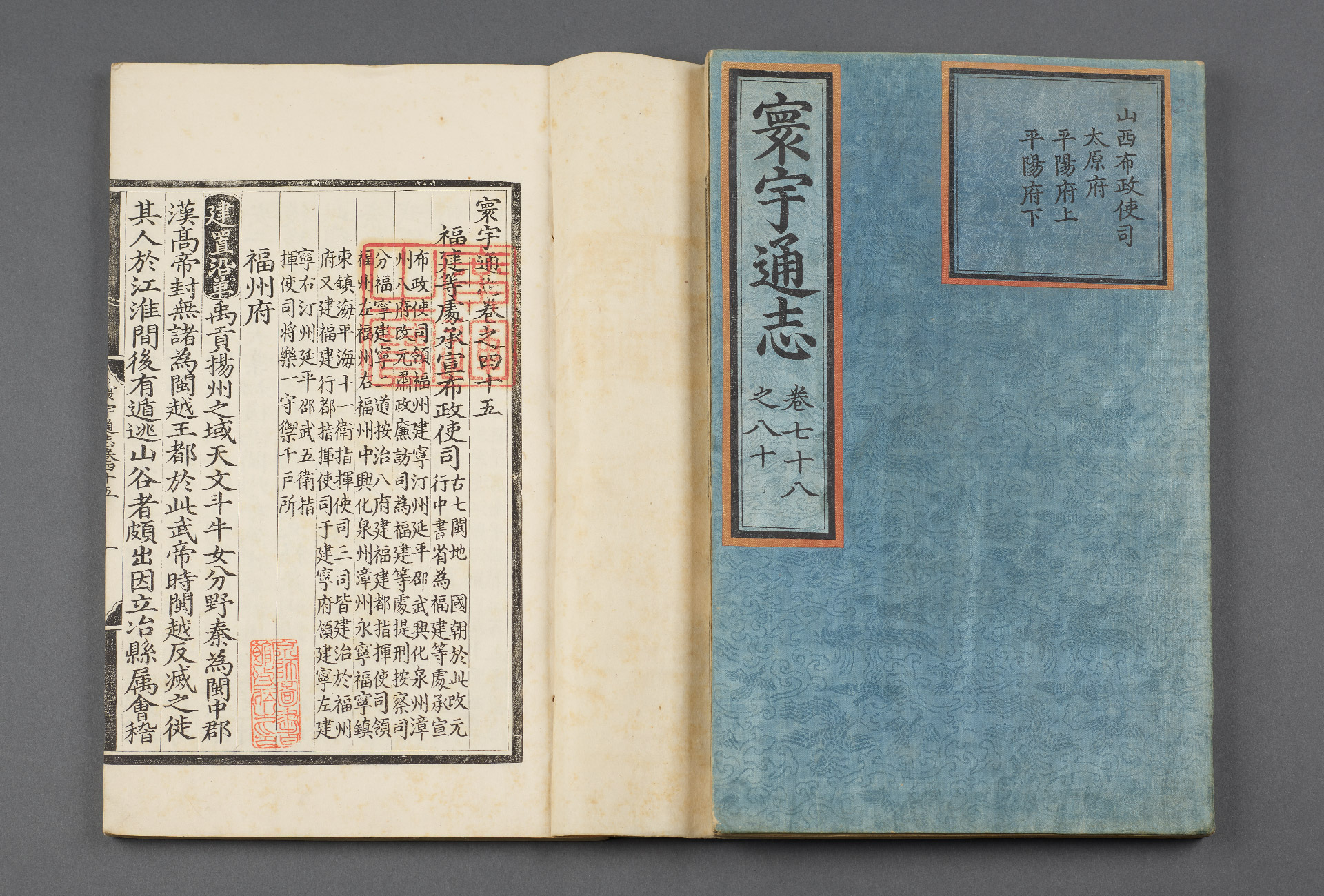

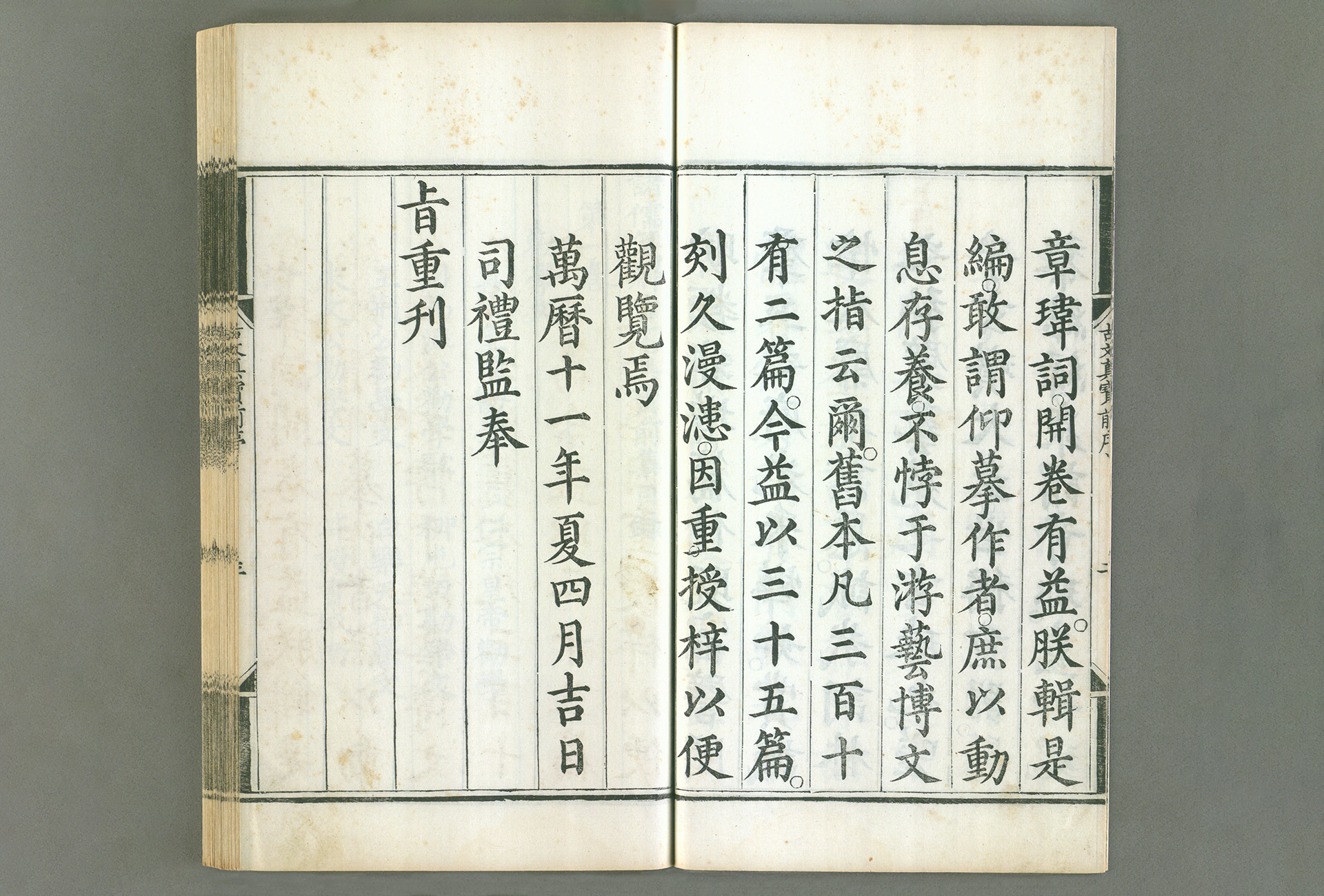

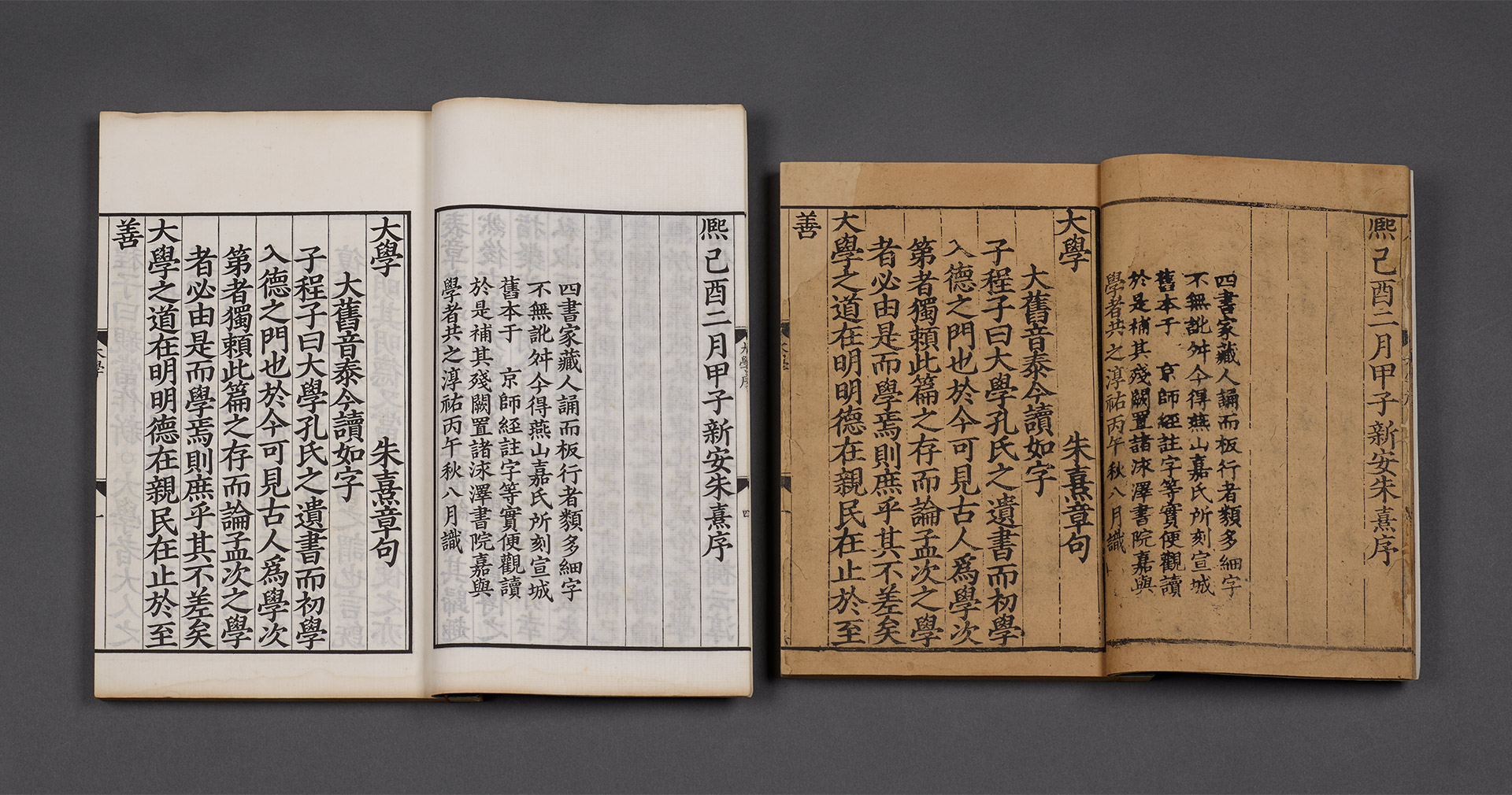

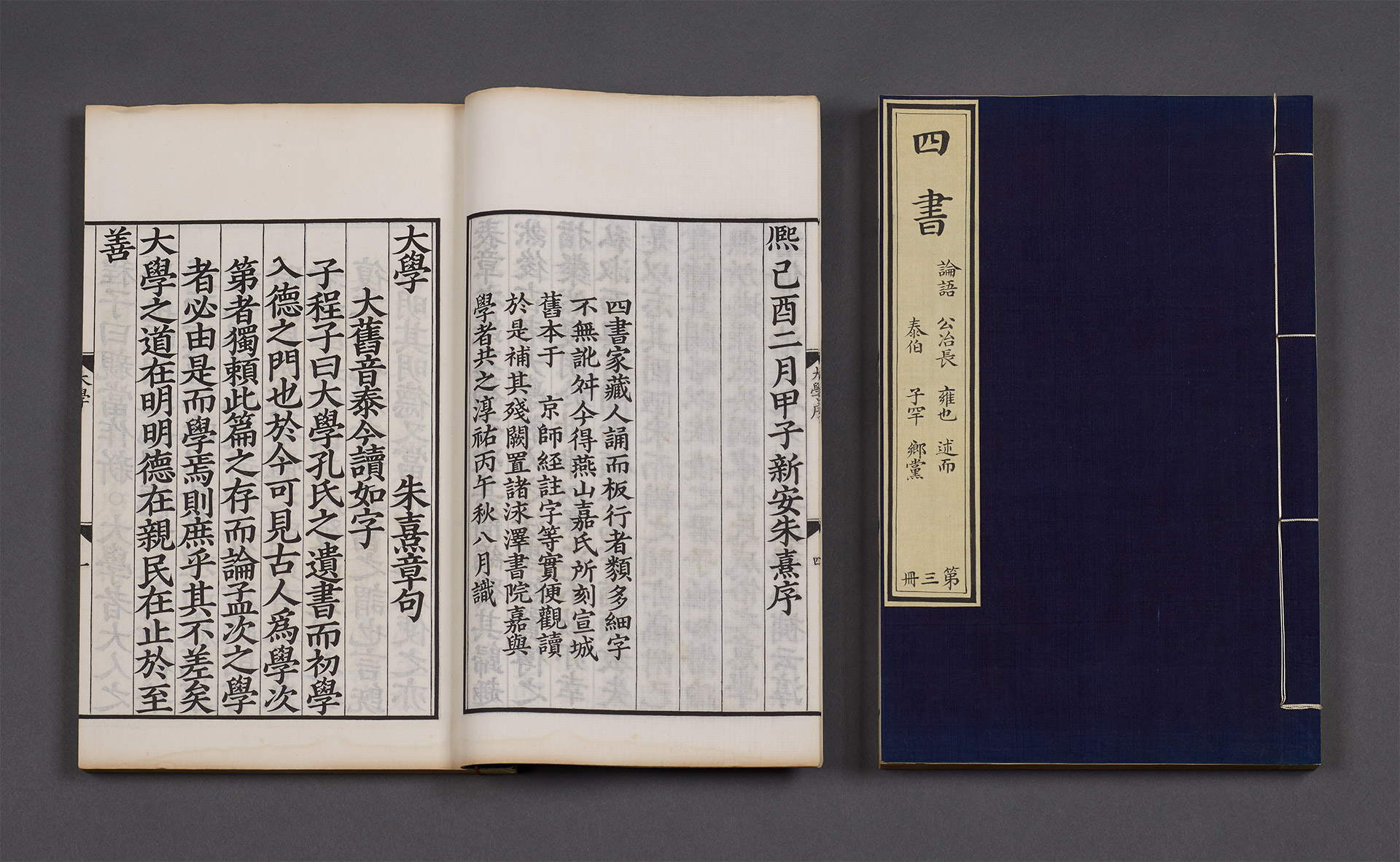

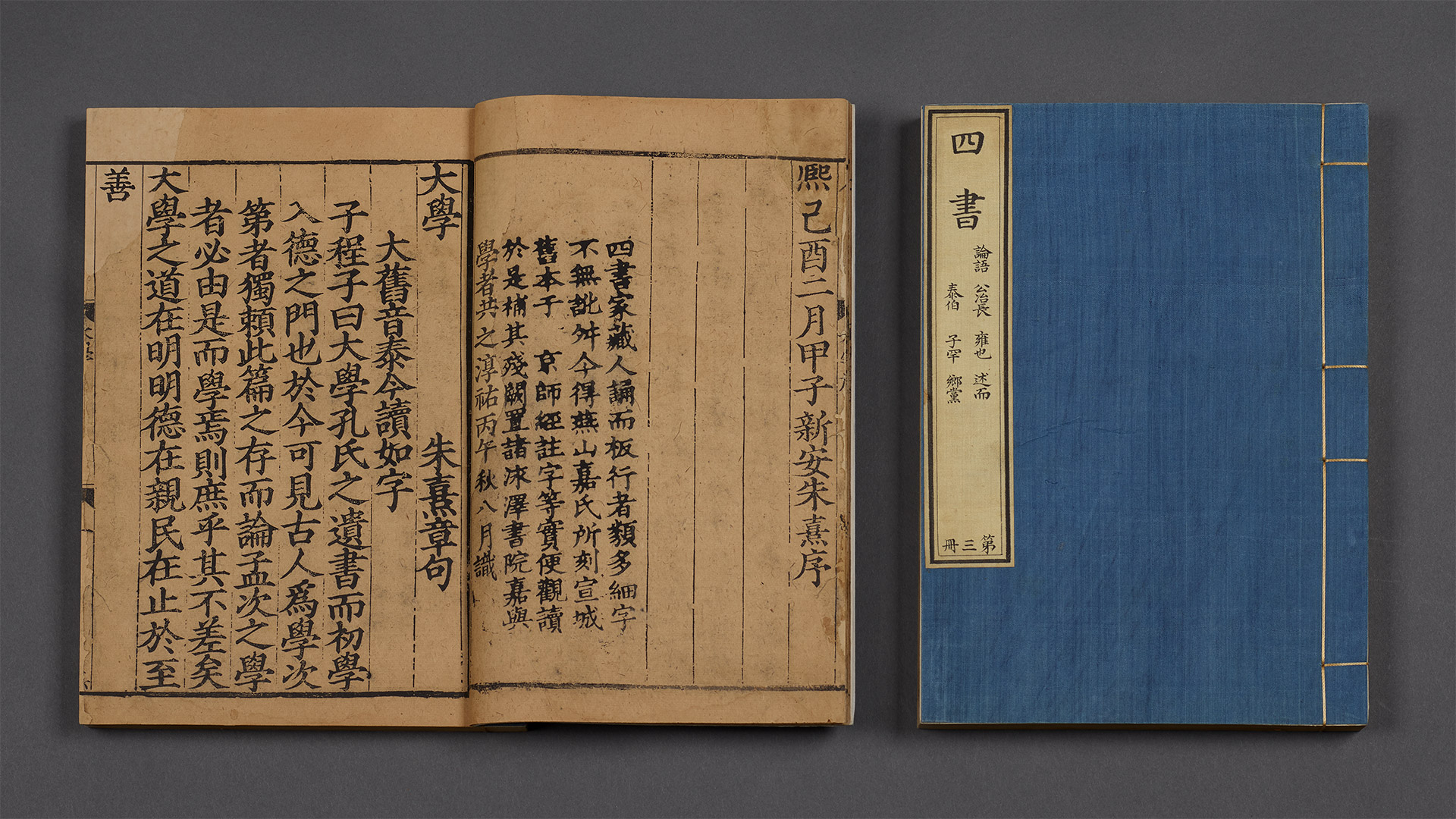

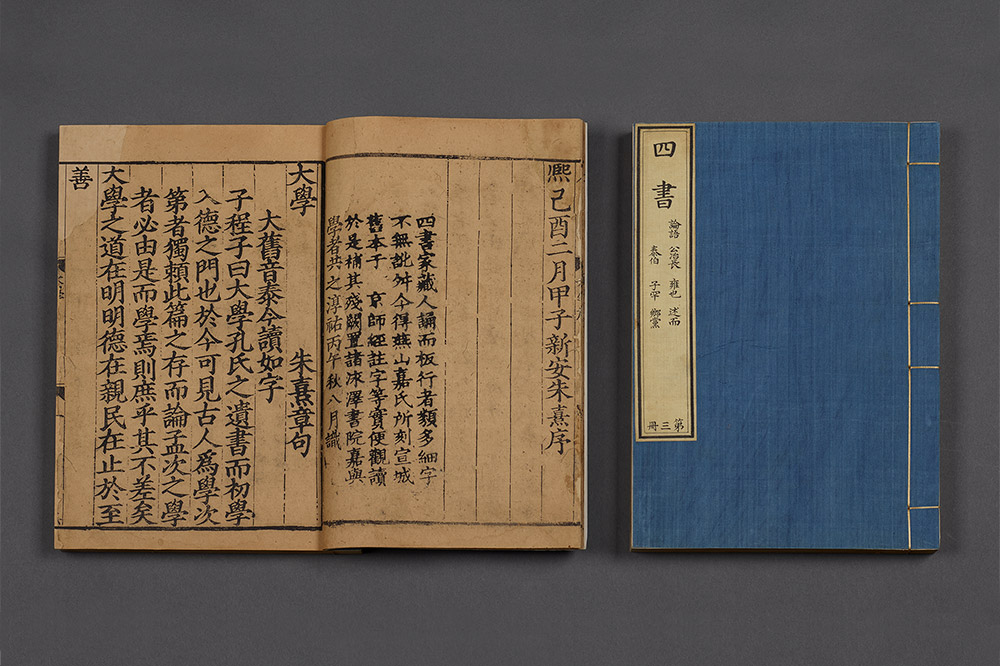

The Wuying Palace was built in the Ming dynasty and did not handle any book-related operations initially. By the Kangxi and Yongzheng eras, it became the official book engraving unit of the imperial storehouse, representing the zenith and highest level of book production technology in the Qing dynasty. The Song dynasty edition of Commentaries on the Four Books, which was actually an imprint edition republished in the late-Yuan dynasty, was reproduced and engraved vividly by the Wuying Palace and later kept in the Kangxi Palace. According to archival data, on April 14, 1717, the great eunuch Su Paisheng handed the emperor 14,000 sheets of luowen paper, and the emperor decreed that the paper be used only for book printing. The Wuying Palace printed ten volumes of the Song dynasty edition of the "four books" at the order of the emperor, making them the first and a limited printing edition.

- Sishu Jizhu (Commentaries on the Four Books)

- Written by Zhu Xi, Song dynasty

- Reprint from a Dangtujun Hall (Anhui) Edition in Song dynasty by the Yongze Academy (Zhejiang), 26th year of the Zhizheng reign (1366), Yuan dynasty

Initially classified by the National Palace Museum as Significant Antiquities - Reprint from a Yongze Academy Edition in Yuan dynasty by the Wuying Palace, 56th year of the Kangxi reign (1717), Qing dynasty

The compilations of books by the Qing court in the Qing dynasty were mostly determined by emperors at their will. Different regulations were in place for the productions, decorations, presentations, and display of books, forming an important part of imperial system of rites operations.

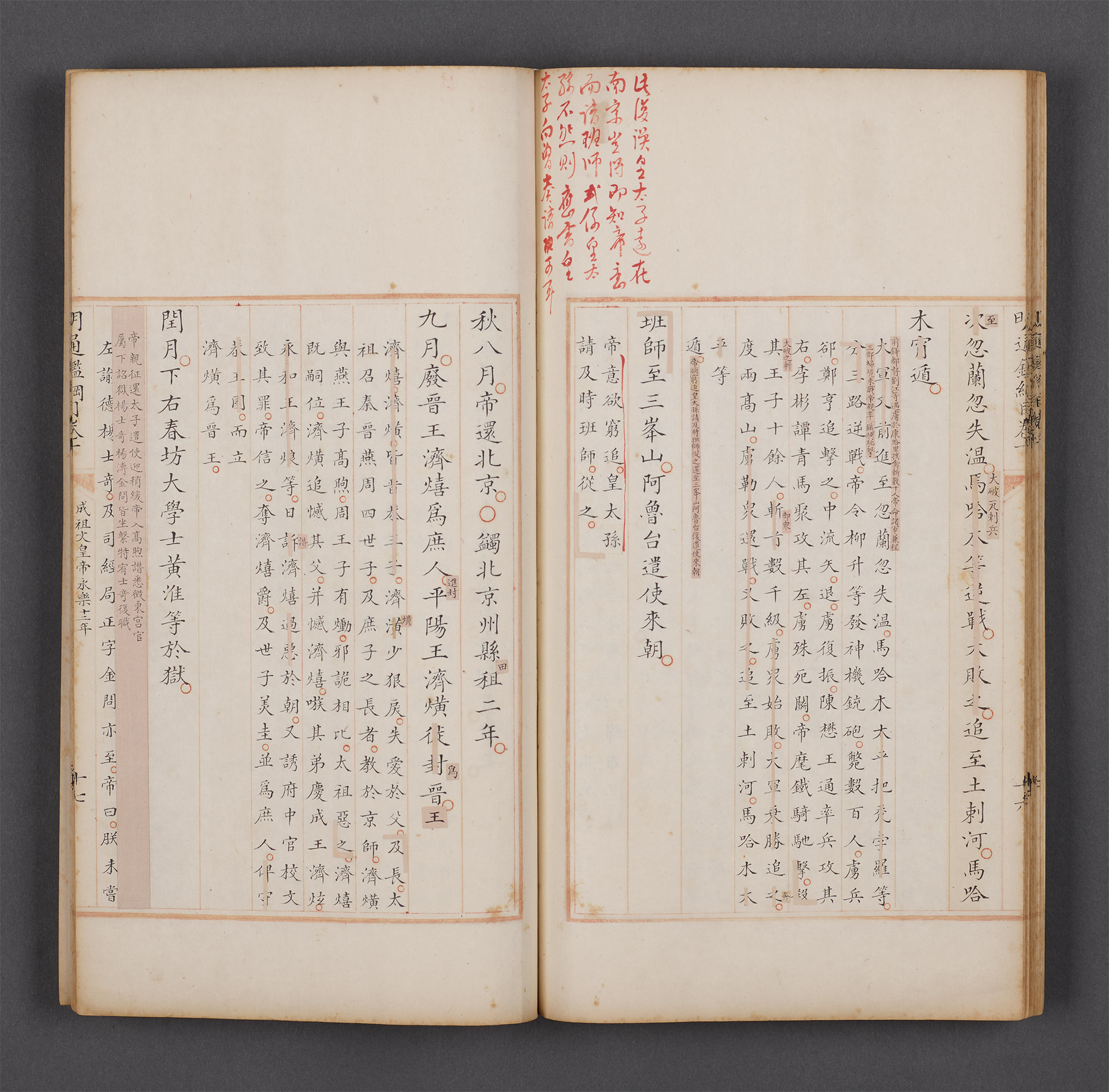

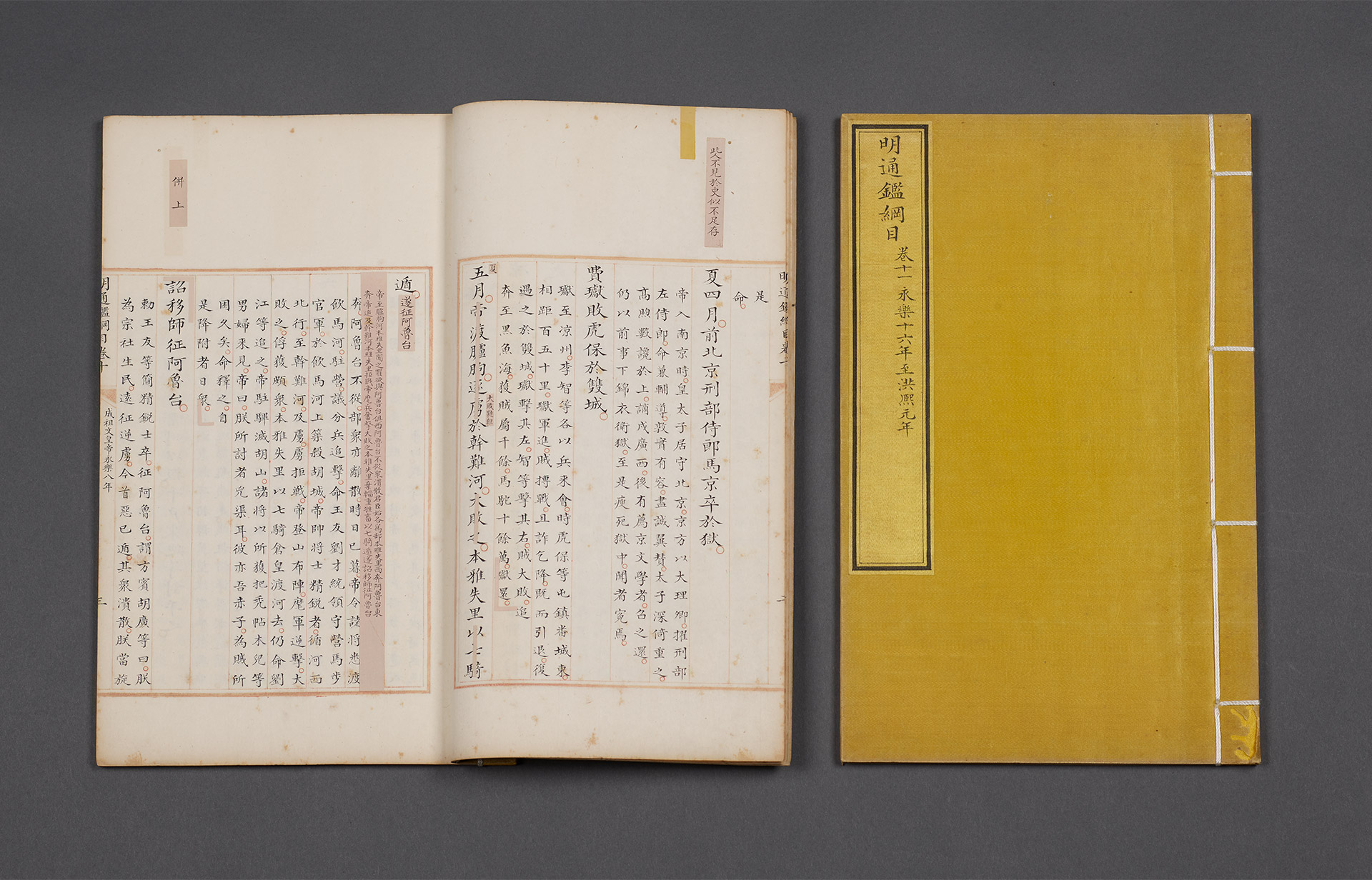

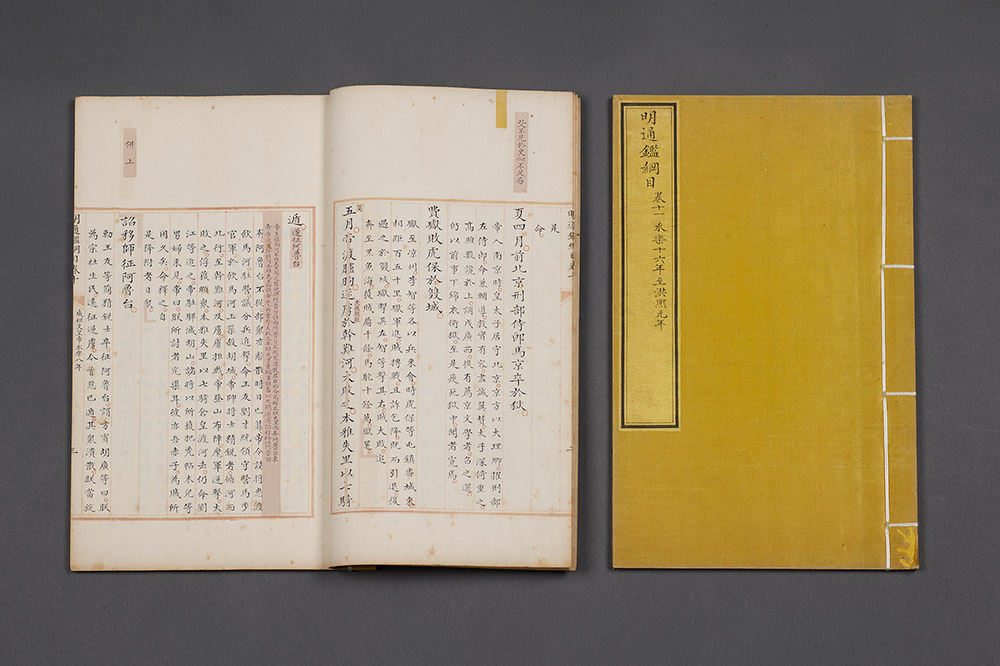

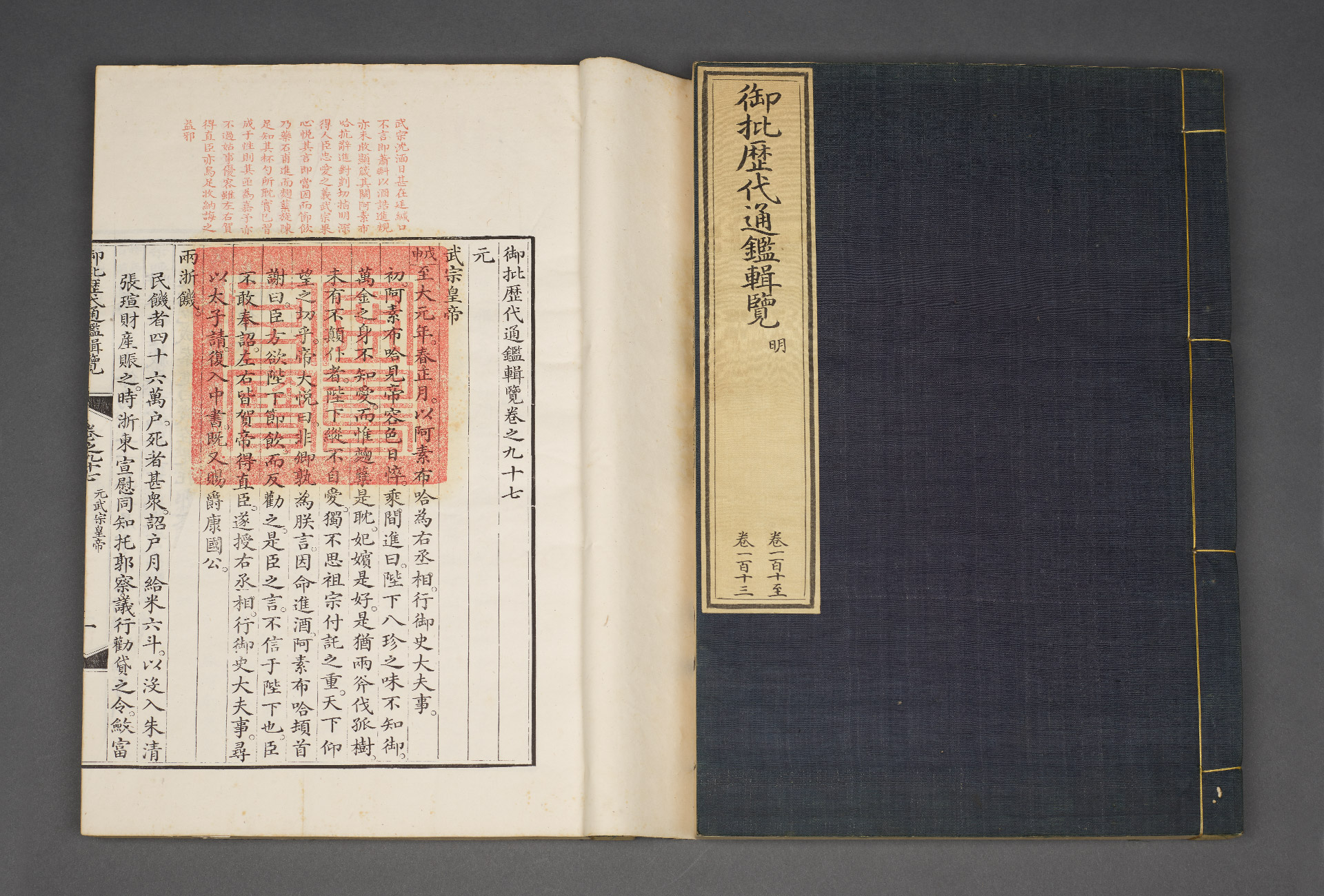

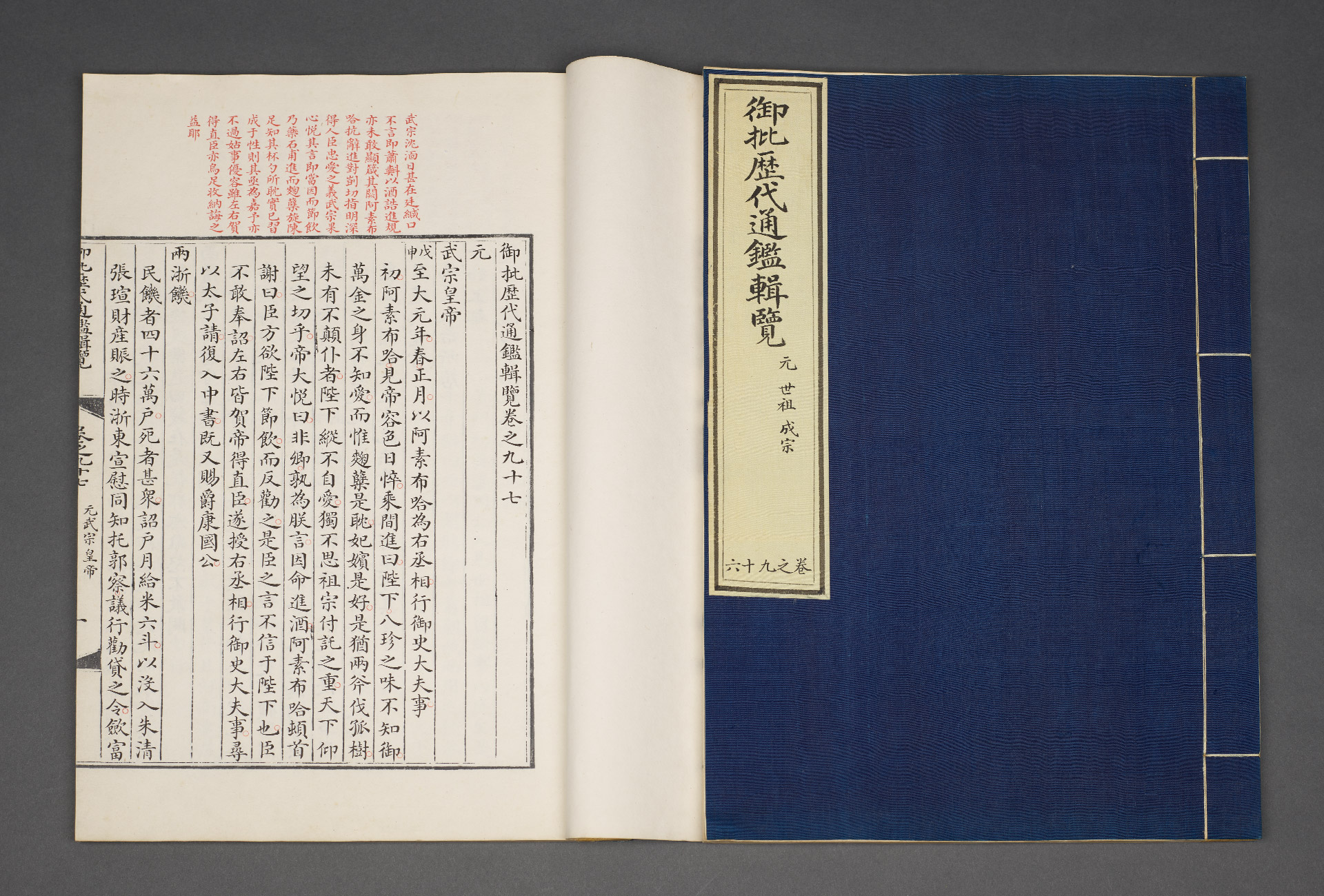

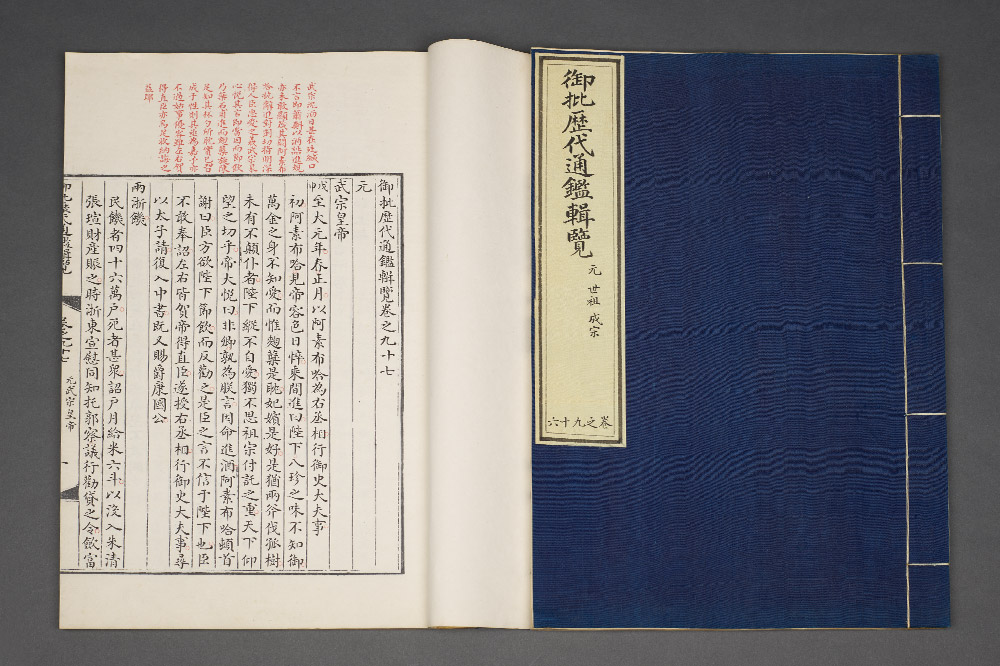

The Qianlong Emperor was keen on writing history, and wanted to have the sole power to give praises or criticisms in his writing. In the early days of his accession to the throne, he continued Kangxi Emperor's, his grandfather's, efforts in criticizing historical events recorded in the "outlines and details" because the Kangxi Emperor stopped at the late-Yuan dynasty. The Qianlong Emperor ordered the Historical Archive to compile the Outline and Details of the Comprehensive Mirror in Ming Dynasty, paying special attention to historical and literary writing styles and norms. The emperor made revision suggestions to the original copies submitted by his ministers, and sent them back for the ministers to correct them. The completed work was titled "Imperial Composed Third Compilation of the Outline and Details of the Comprehensive Mirror in Aid of Government." Decades later, the Qianlong Emperor did not include this book in the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries. Instead, he asked to re-edit it based on the Comprehensive Mirror in Successive Dynasties with Imperial Critical Notes published later, showing that he was not satisfied with the former.

Compared with the Imperial Composed Third Compilation of the Outline and Details of the Comprehensive Mirror in Aid of Governance, which involves compilation endeavors made across different dynasties, the Collection of the Comprehensive Mirror in Successive Dynasties with Imperial Critical Notes is an outline and details of history. It took nearly 10 years to complete the work, which contains more than 2,000 of Qianlong's comments on the gains and losses of the control of chaotic historical events, creating a new model for historical records. At the end of the compilation, a final version was written and submitted (displayed in the Palace of Tranquil Longevity) before being printed in this style. Large white paper and thick ink were used for both the written and block editions. The work was exquisitely made and was a rare large-volume work in the Qing imperial palace.

- Yupi Lidai Tongjian Jilan (Collection of the Comprehensive Mirror in Successive Dynasties with Imperial Critical Notes)

- Compiled by Fu Heng, et al., Qing dynasty

- Imperial court two-colored manuscript written in black-lined columns, Qianlong reign (1736-1795), Qing dynasty

- Two-colored imprint of the Wuying Palace, 32th year of the Qianlong reign (1767), Qing dynasty

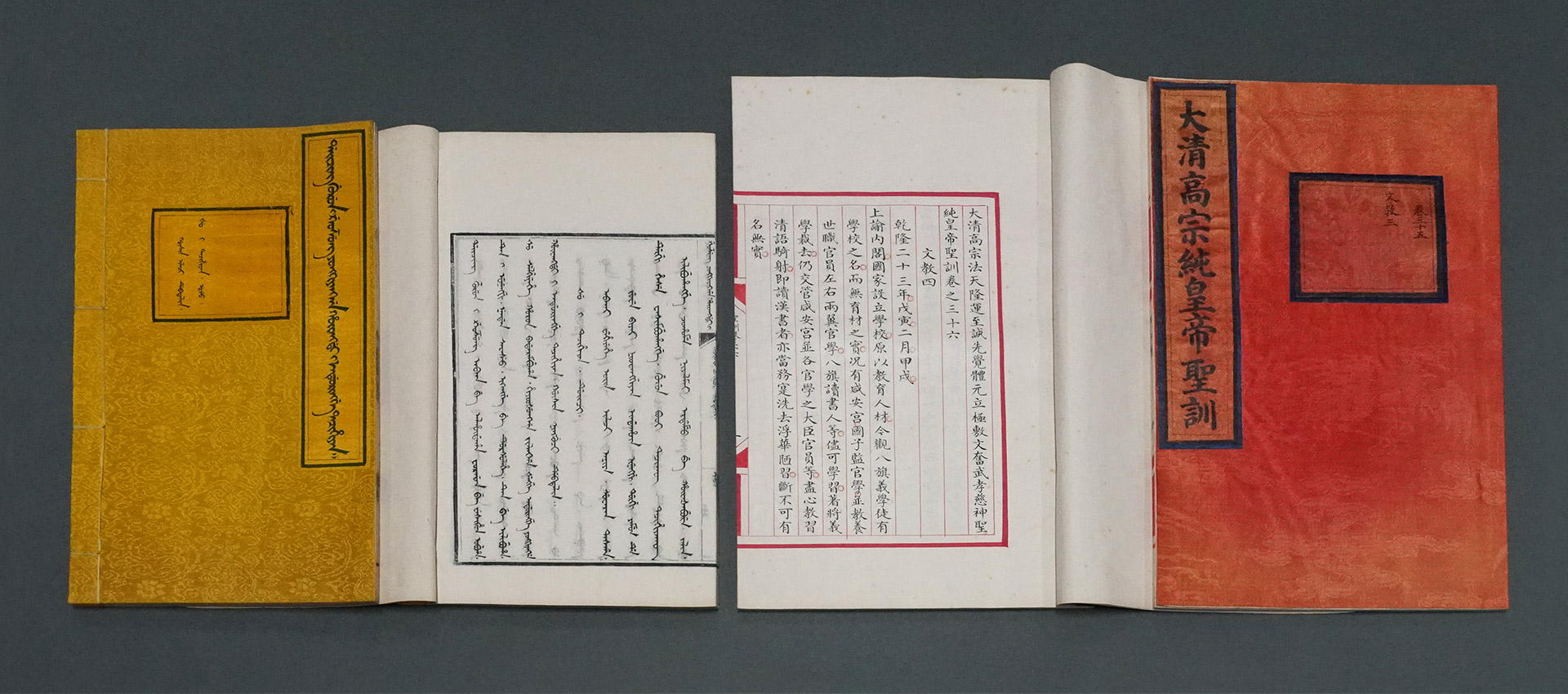

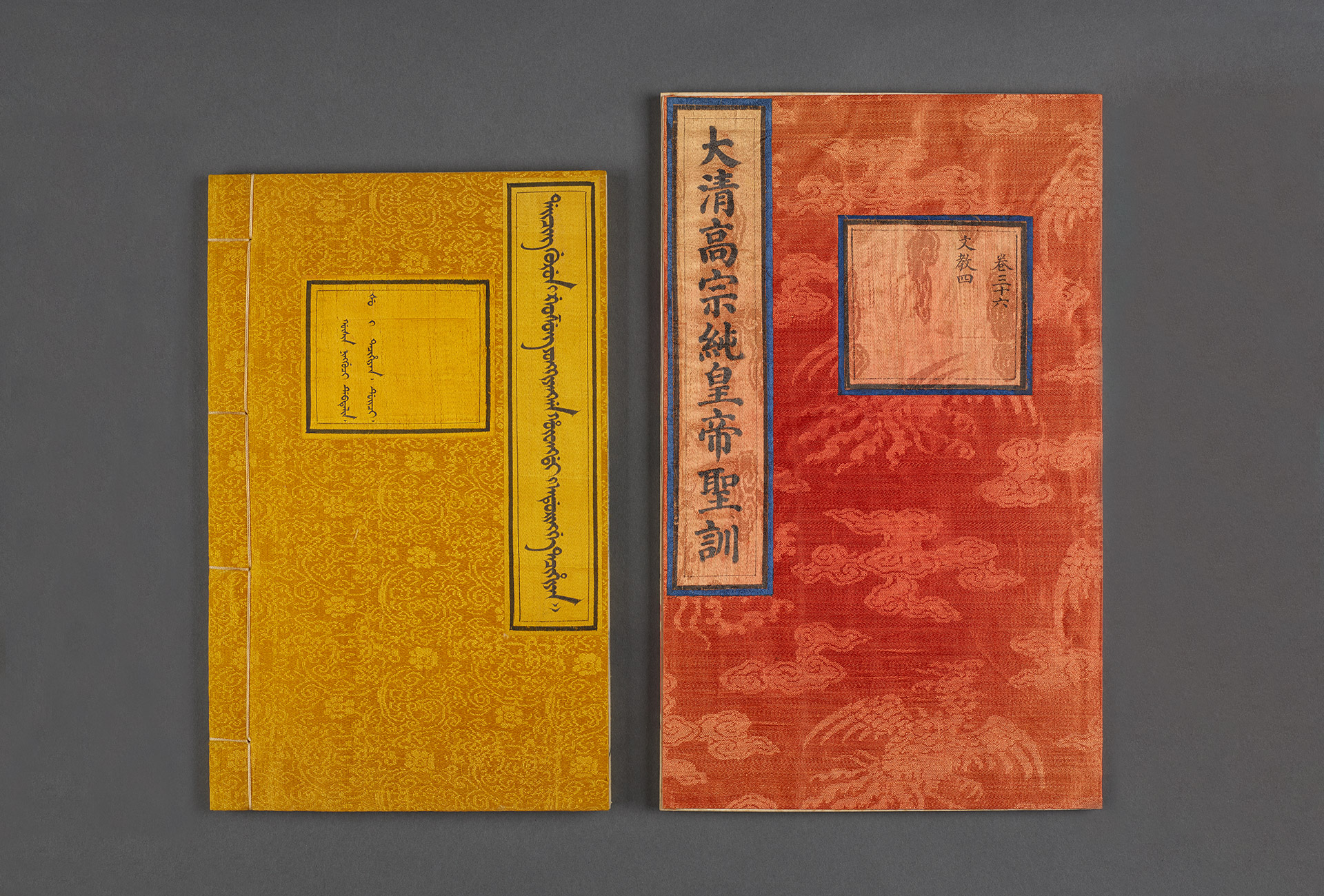

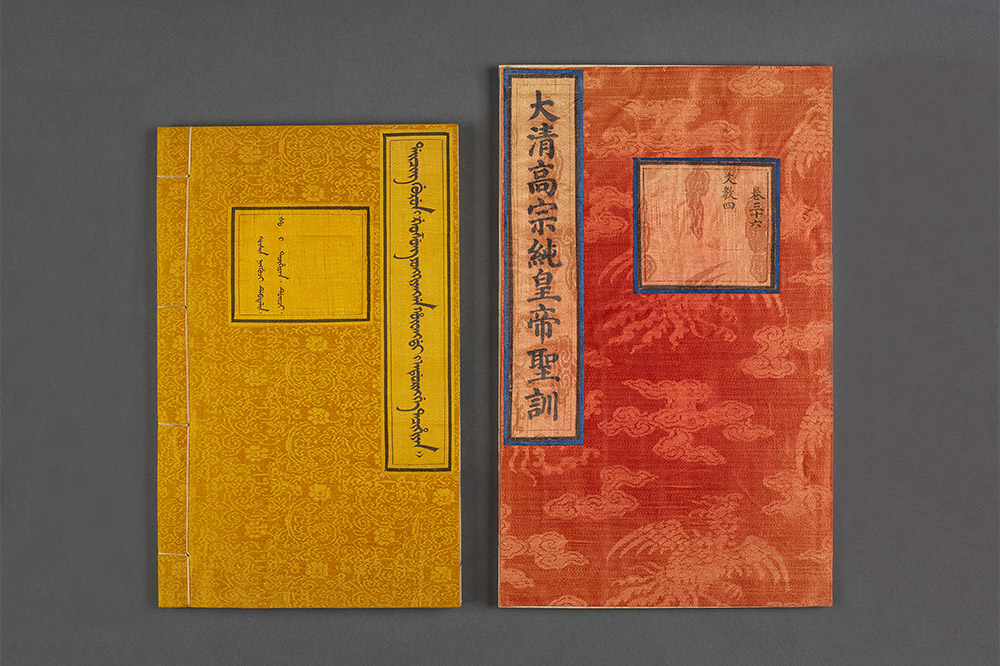

- Daqing Gaozong Chun Huangdi Shengxun (Imperial edicts of the Qianlong reign)

- Compiled by order of the Jiaqing Emperor, Qing dynasty

- Imperial court manuscript written in red-lined columns, Jiaqing reign (1796-1820), Qing dynasty

- Imprint in Manchu of the Wuying Palace, Jiaqing reign (1796-1820), Qing dynasty