Treasures from the Imperial Libraries

Legend has it that the Langhuan is a mythical place where the Celestial Emperor stores his books. The yuncao, on the other hand, is a strong-scented herb used by the ancients to ward off all insects that eat into books, and its scent, yunxiang, is thus frequently likened to the unique fragrance of books. The vast number of precious rare books collected by the Ming and Qing imperial libraries that the common souls stood no chance of catching even a glimpse. These great libraries were not immune to natural hazards or the ravages of war, and many precious books were damaged or lost forever. We can only try to imagine their glory through the catalogues compiled at the time and the remnants of precious surviving editions that bear certain collectors' seal marks. This section presents a number of invaluable texts held by the Ming and Qing imperial libraries to highlight their rarity and scholarly value; it also brings another aspect of books that it can be collected as antique or arts. The most iconic one is the Tianlu Linlang (Gems of Heavenly Favor) Library installed by the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736-1795), which was to mark a unique chapter in the annals of China's imperial libraries.

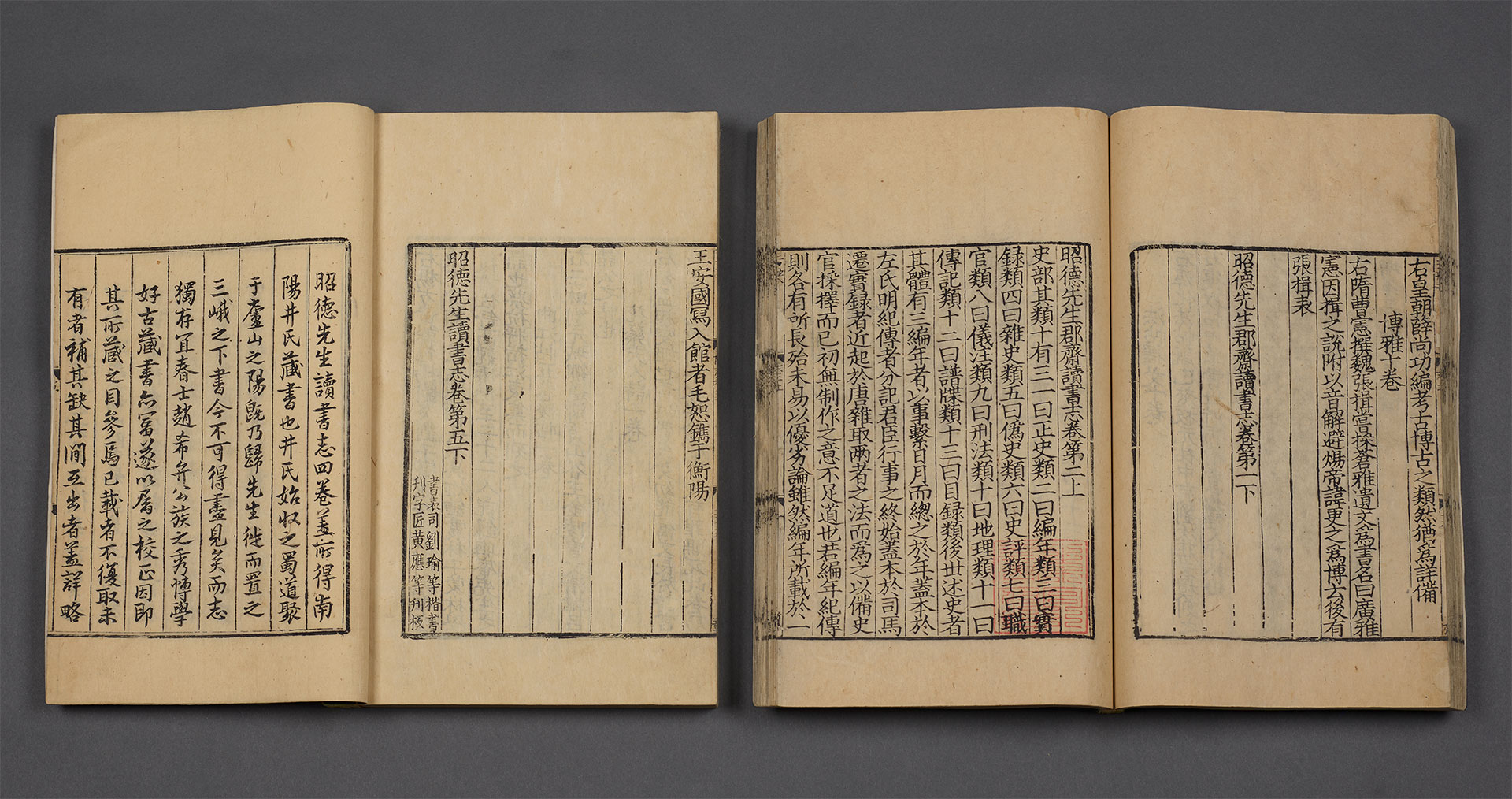

The general situations of and changes in the imperial library book collections in the Ming dynasty can be identified by perusing two bibliographies; namely, The Bibliography of Wenyuan Pavilion and The Bibliography of the Inner Secretariat. The Bibliography of Wenyuan Pavilion, compiled in the mid-15th century, consists of over 7,000 parts and over 40,000 volumes and provides a full account of all the books in the court after the capital was relocated to Beijing in the early-Ming dynasty. During the early- and mid-Ming dynasty, the Wenyuan Pavilion suffered repeated fires which, coupled with the fact that the emperors and their ministers did not pay attention to the collection of books, and that the management of these books became disorderly, the 12 levels of corruption and 15 levels of theft ensued. During the Wanli Era in the early-17th century, The Bibliography of the Inner Secretariat, which consisted of slightly over 2,000 books and nearly 19,000 volumes, was reorganized.

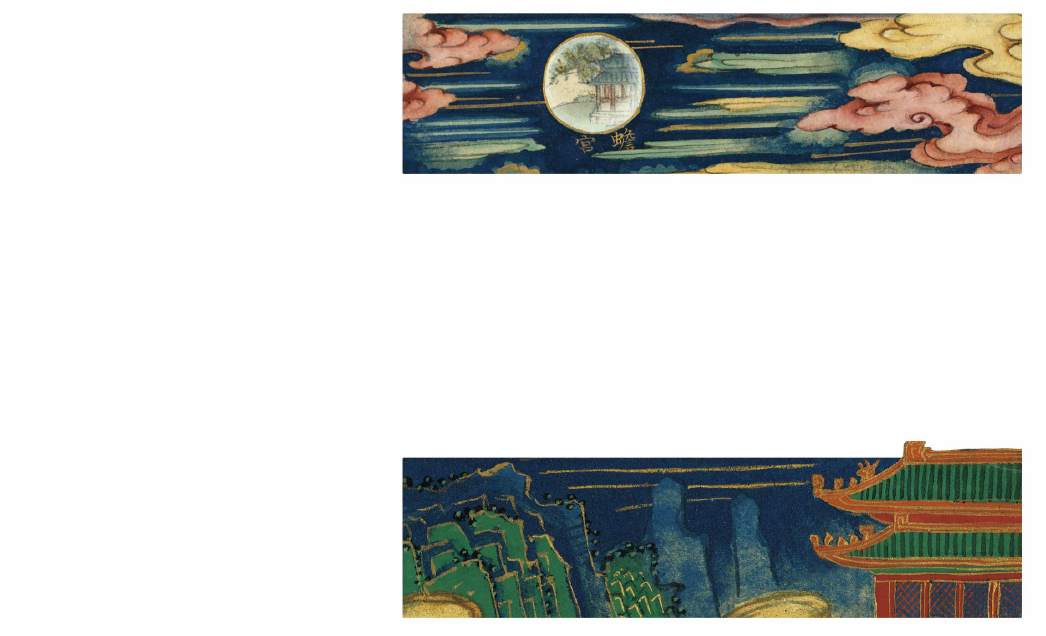

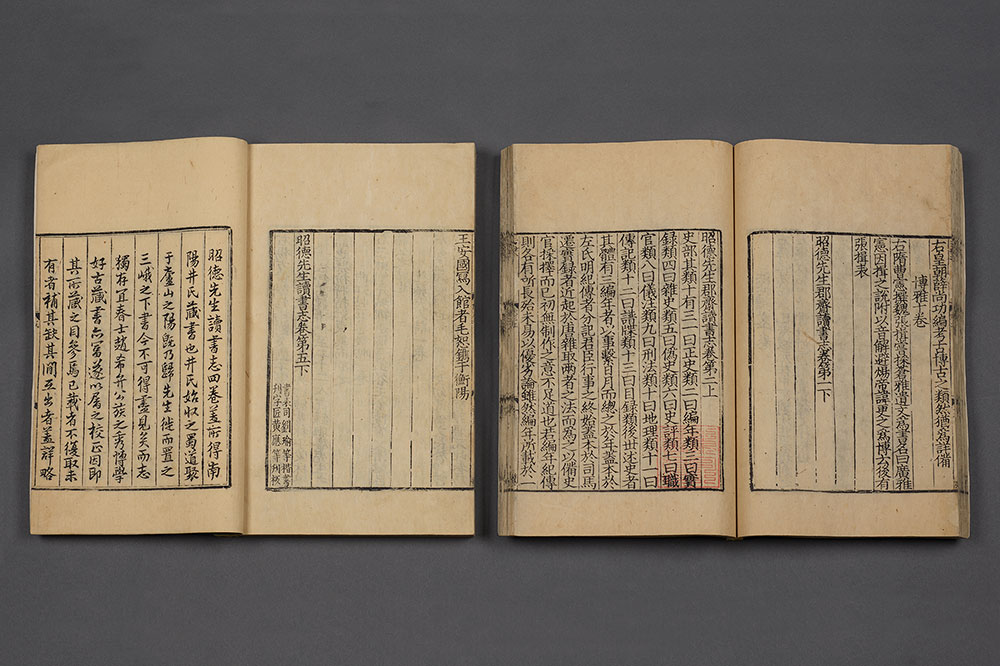

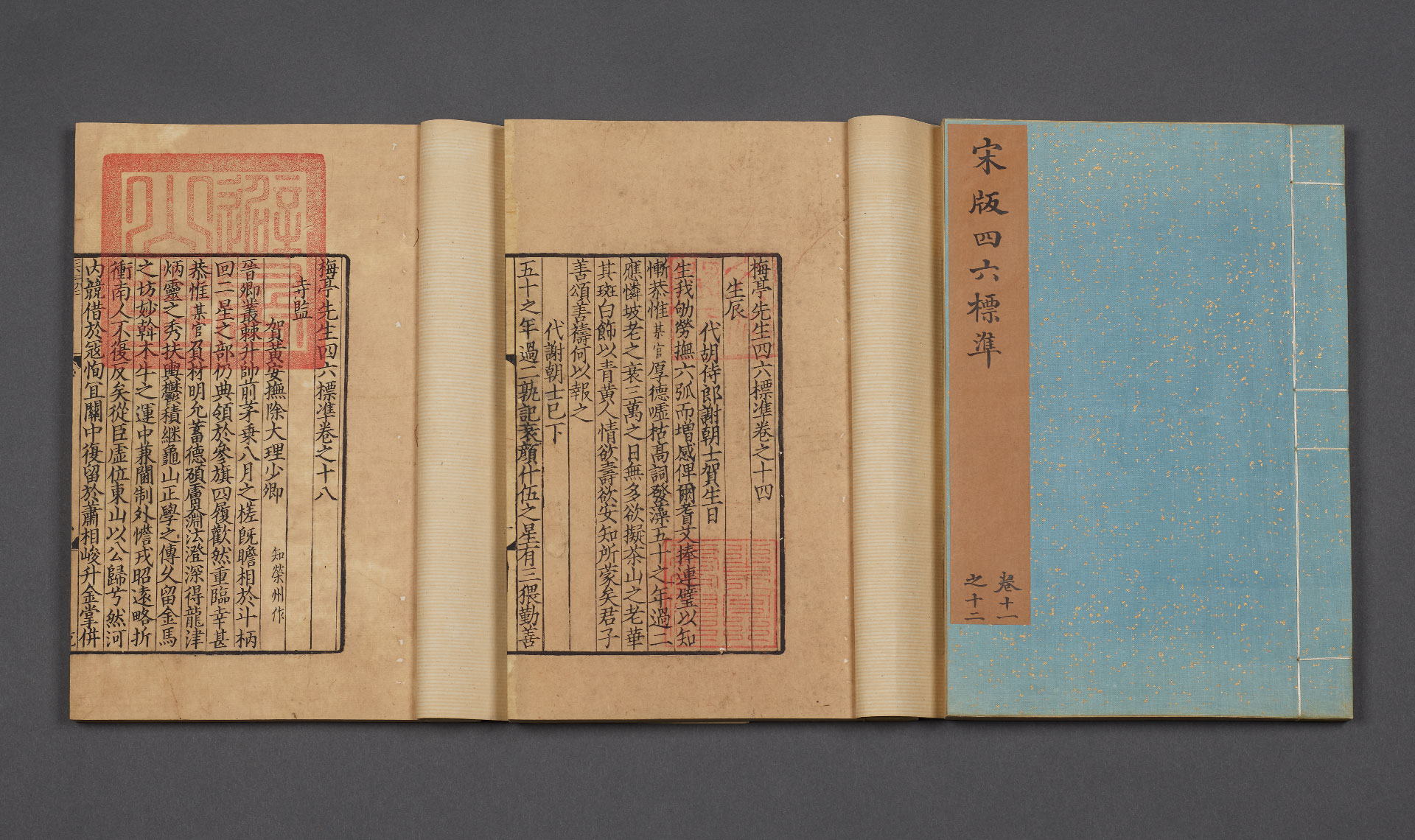

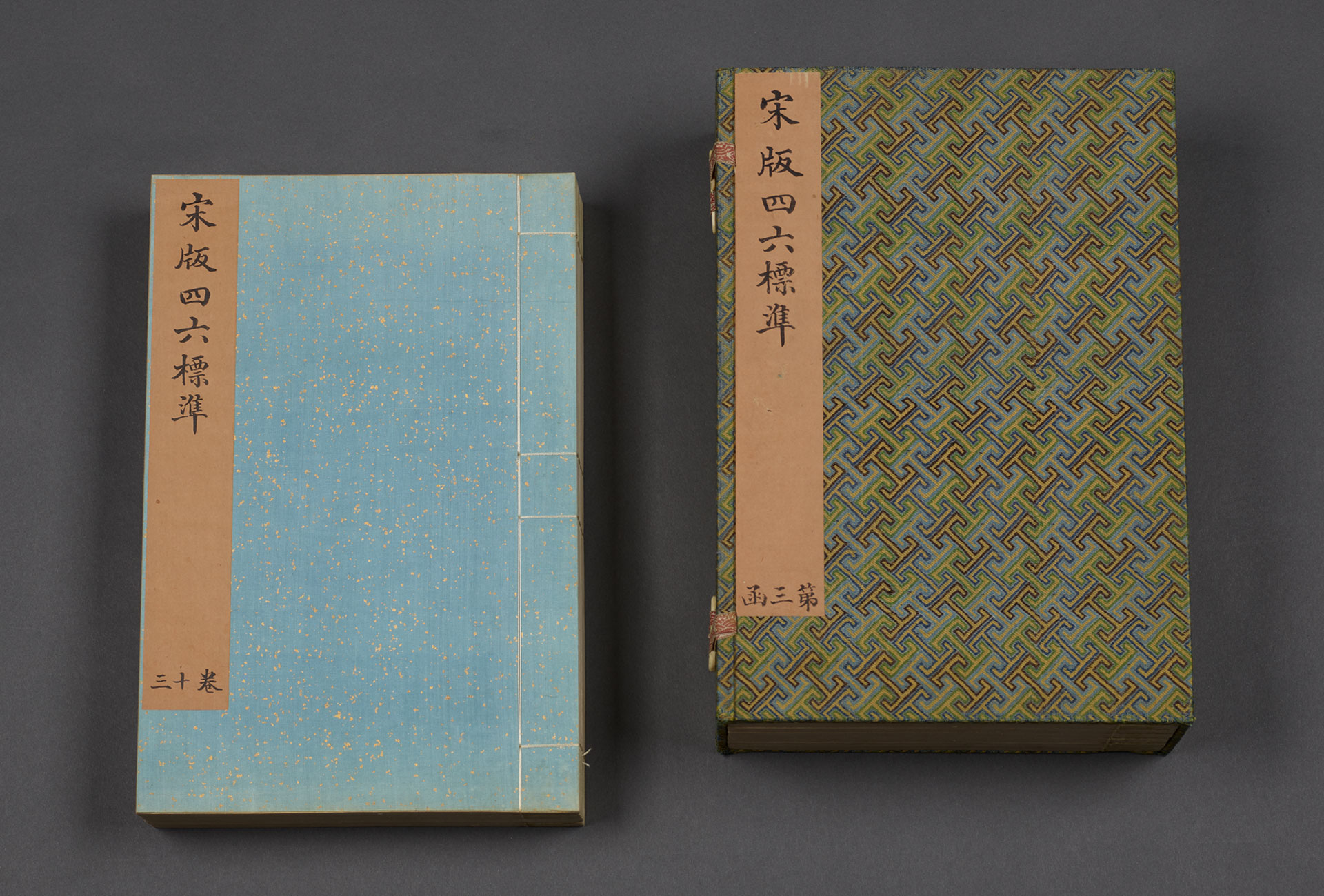

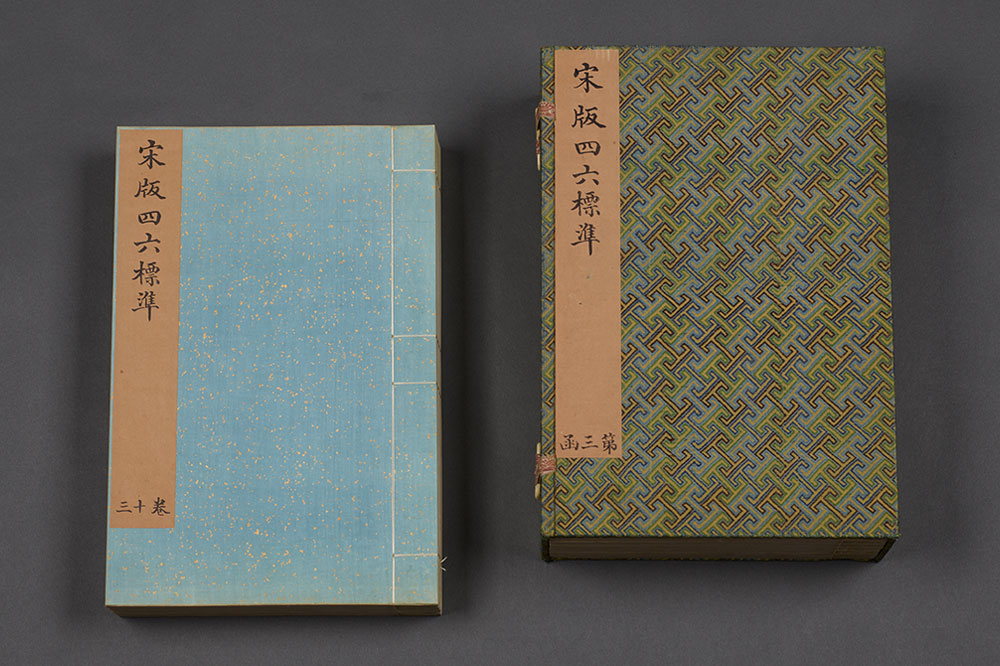

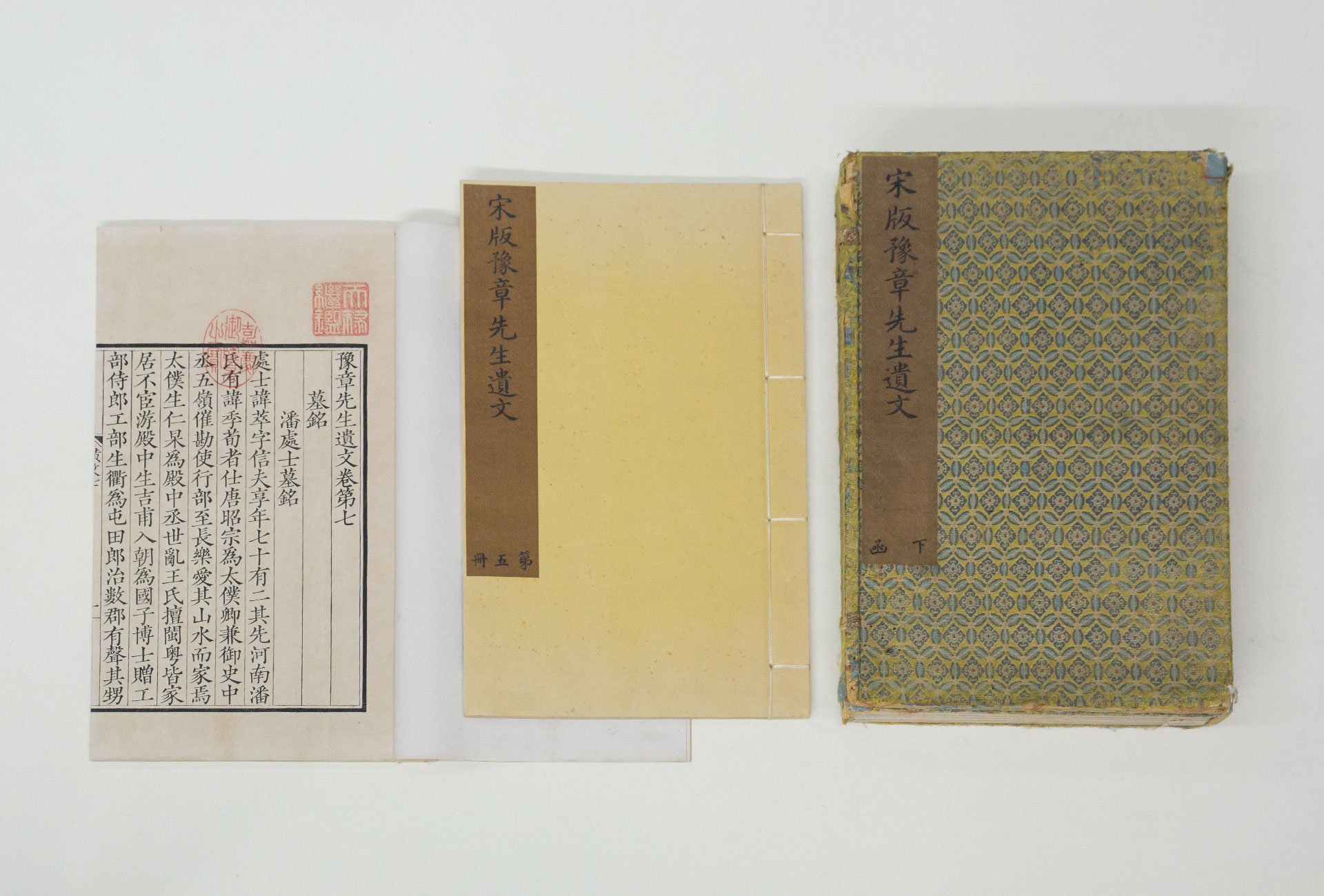

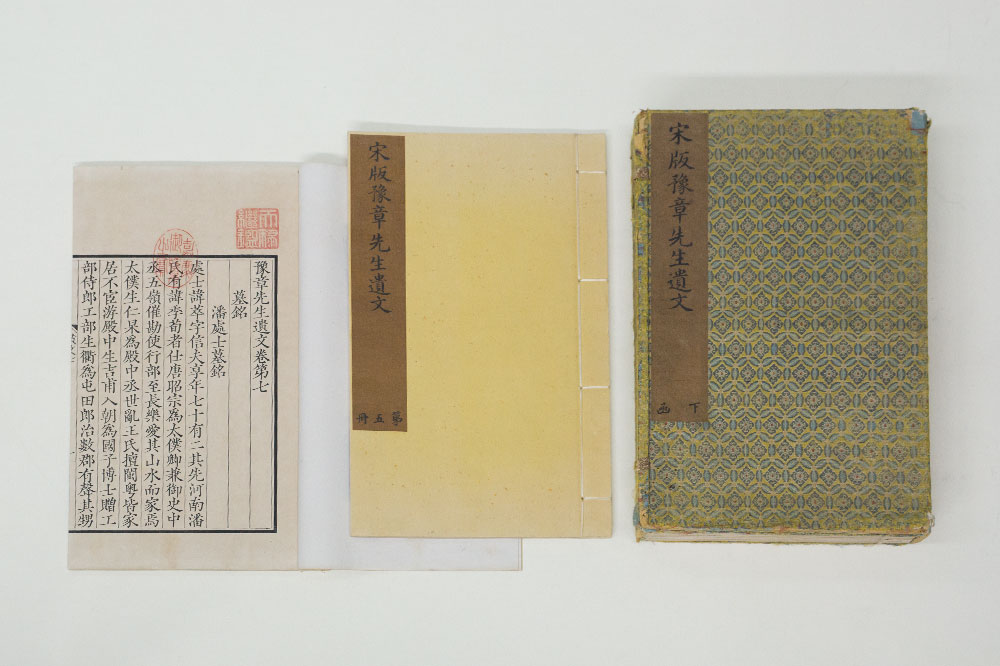

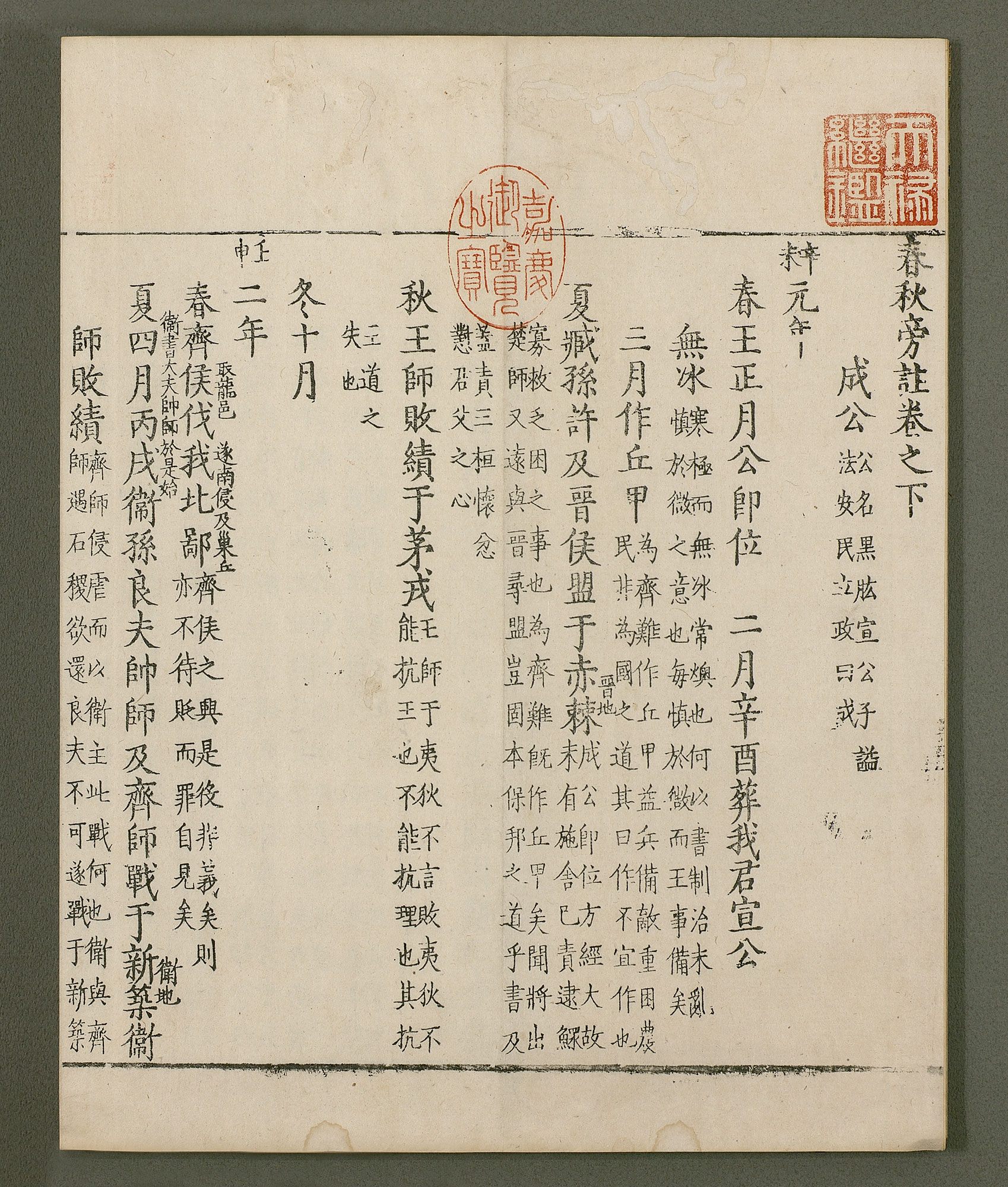

One of the sources of Qing court book collections was books passed down from the previous dynasty. However, during the transition from one dynasty to the next, it was common for books to be severely damaged due to palace fires. The few rare books that survived provide clues to the secrets of the Ming and Qing courts, making them special. Examples include the Song dynasty edition of Memoirs of Master Zhaode's Readings in the Chun Studio containing the nine-fold seals of the East Court Book House. The book was originally stored in the collection of the Ming dynasty crown prince. The Song dynasty edition of Master Meiting's Standard on Parallel Prose, which was first printed in the Song dynasty, possess the "Wenyuan Pavilion" seal of the Ming dynasty imperial storehouse. The book was stamped "Summer Resort" when it was redecorated by the Qing court, turning it into an elegant rare book of the imperial palace.

- Zhaode Xianshen Gjunzhai Dushu Zhi (Memoirs of Master Zhao-de's Readings in the Chun Studio)

- Written by Chao Gongwu, Song Dynasty

- Printed by Li An-chao in Yuan-zhou based on the edition of the 9th year of Chunyou's reign (1249), then renovated in the Song and the Yuan dynasties.

- Initially classified by the National Palace Museum as National Treasures

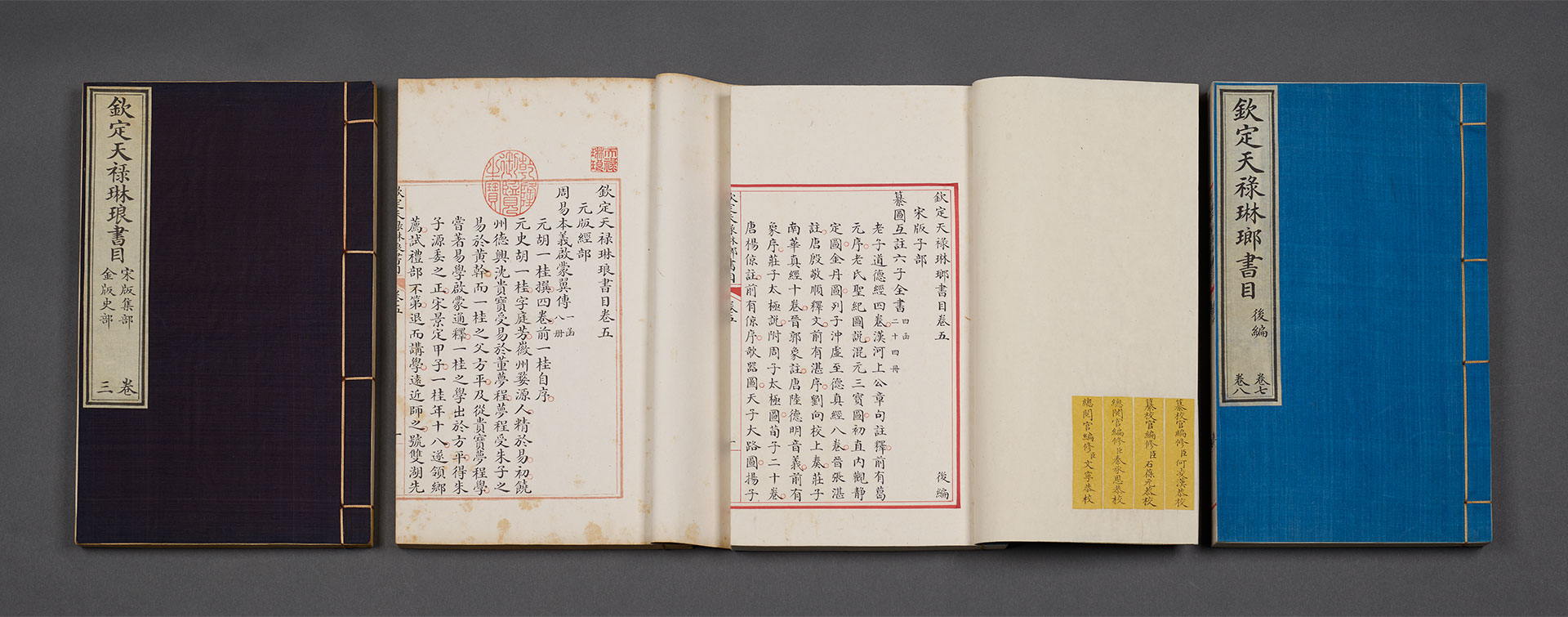

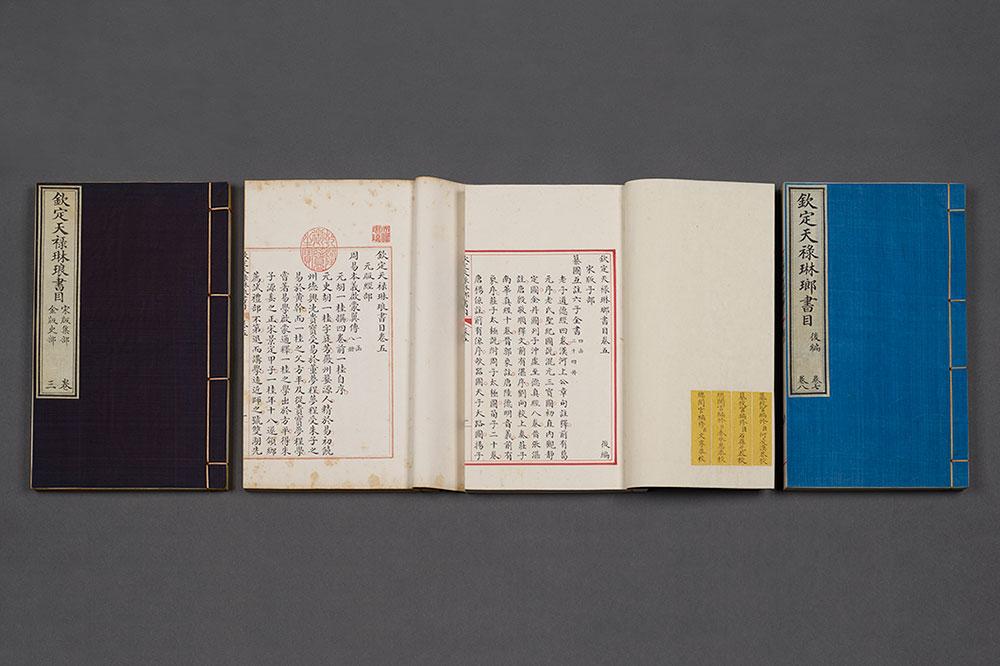

In the context of ancient Chinese court book collections, the Qianlong Emperor was the first to include "ancient books" as a part of antiquity collection. The first imperial rare book collection, the Tianlu Linlang Library, marked the beginning of the emperor's comprehensive collection of court artifacts. From 1736 to 1775, rare books from locations such as the Bower of Crimson Snow (in the Imperial Garden) and Zhaoren Hall (in the Palace of Heavenly Purity) were regarded as works of art from previous dynasties and as prestigious imperial works.

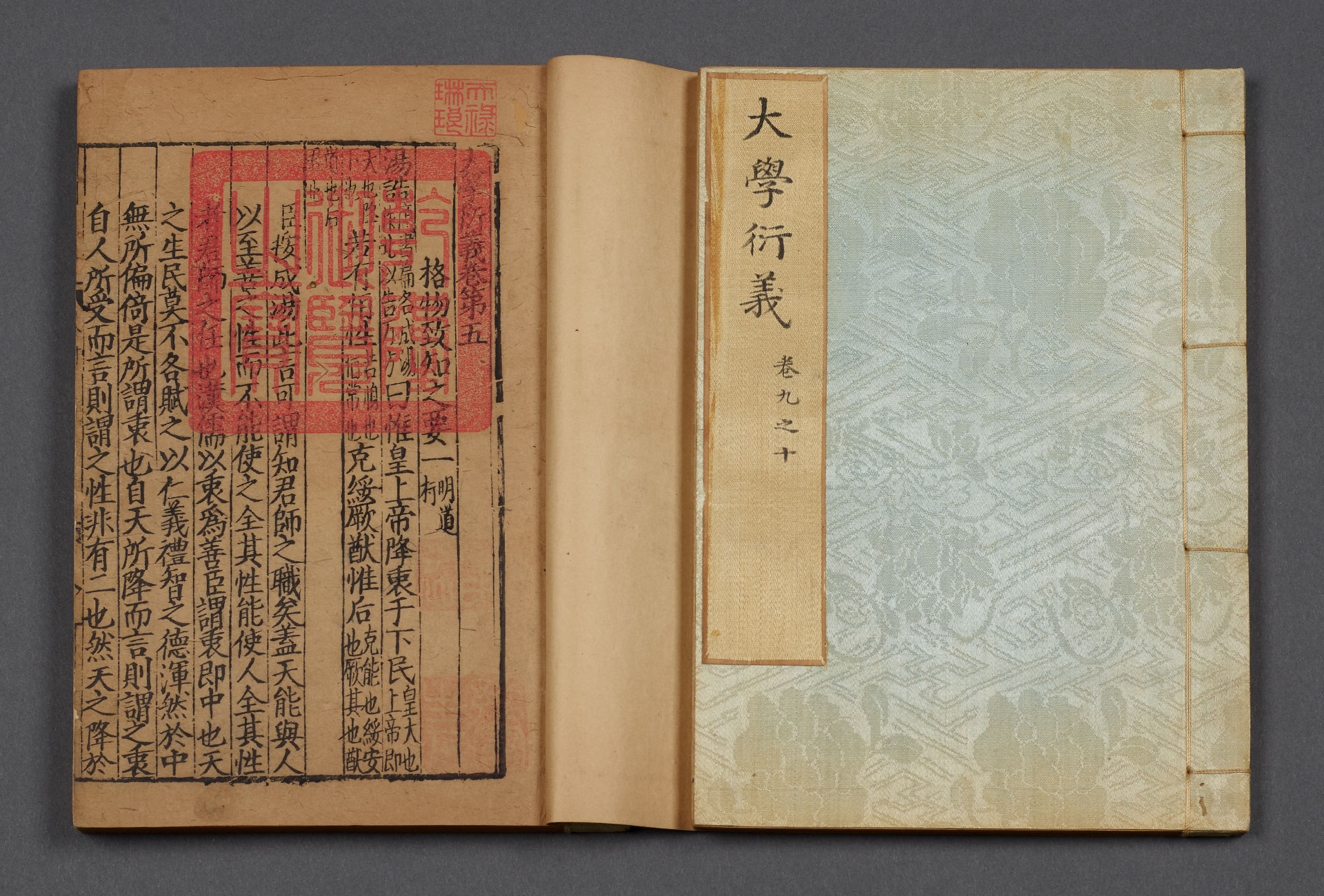

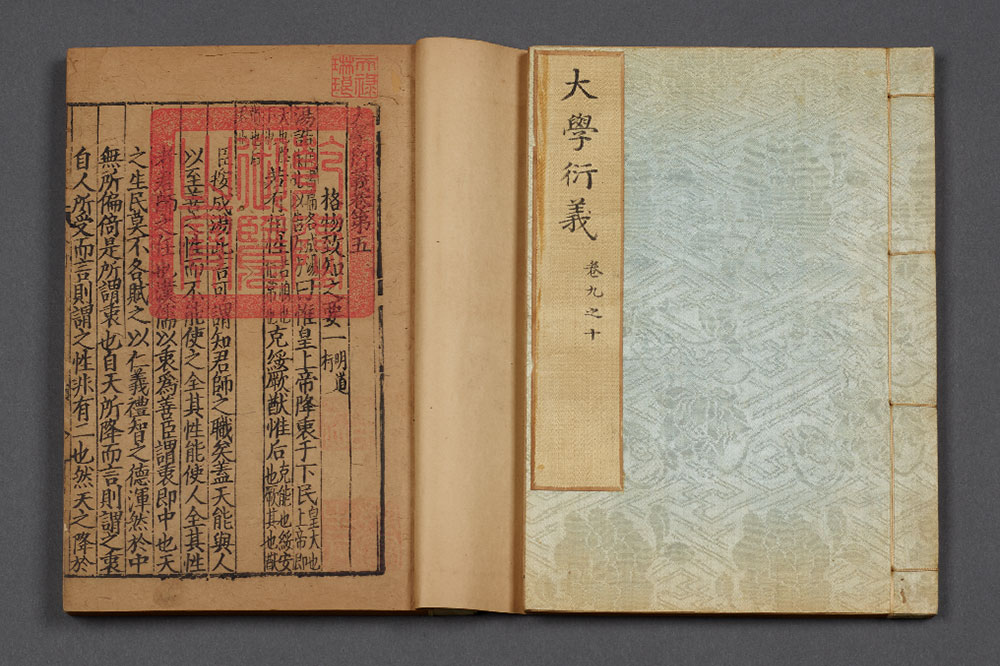

The National Palace Museum houses the largest number of Tianlu Linlang Library-related ancient books. The Extended Meaning of the Great Learning, published in the early-Ming dynasty, was obtained during Kangxi Emperor's first southern inspection tour. The ancient book had a satin cover, and its first and last pages were stamped with the small seal "Tianlu Linlang Library" and red seal "imperial treasure of Qianlong reign," preserving the decorated appearance of rare books in the Qianlong era. However, the book was later moved to other palaces, possibly because it was not a real Song dynasty edition.

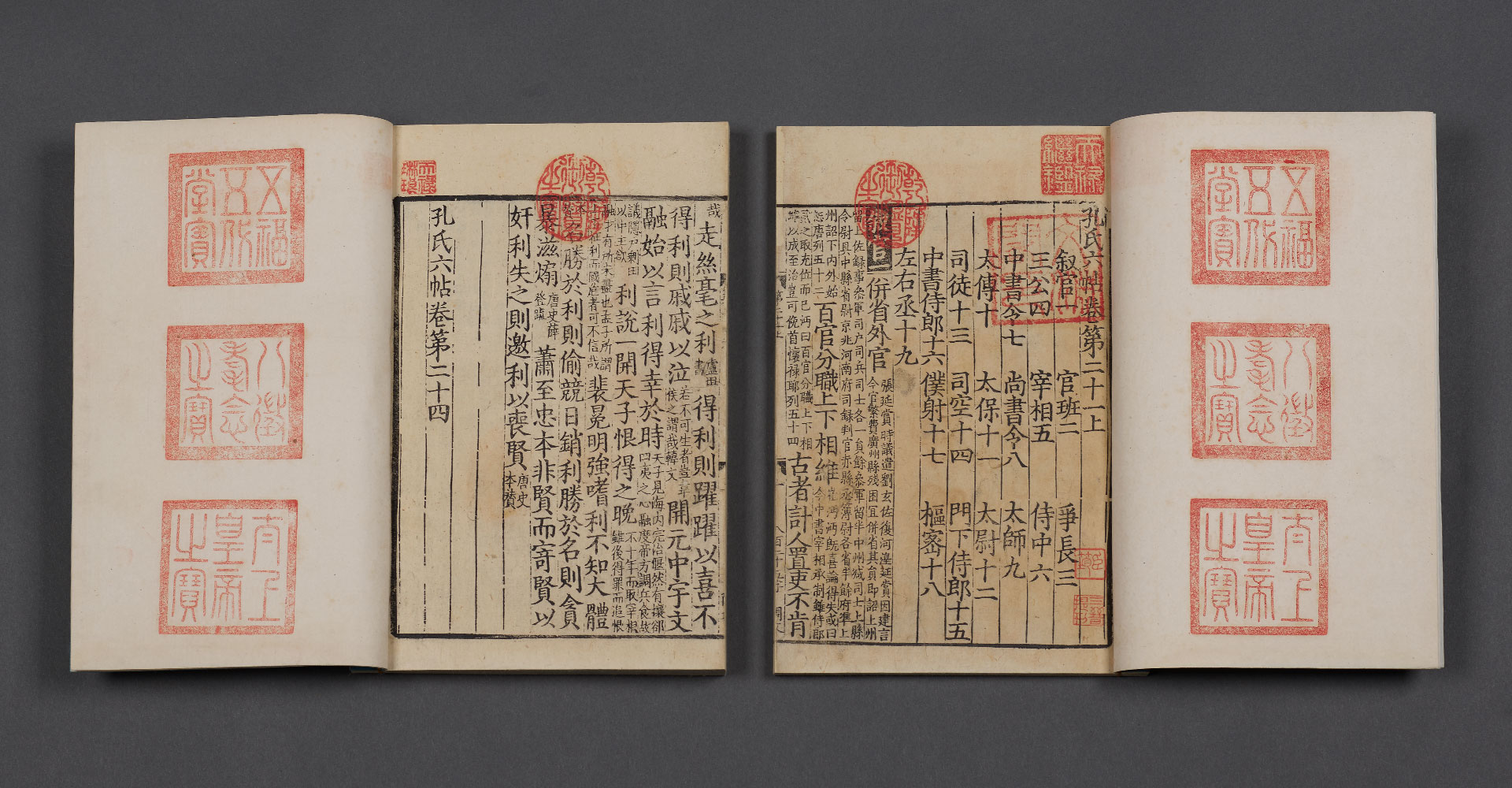

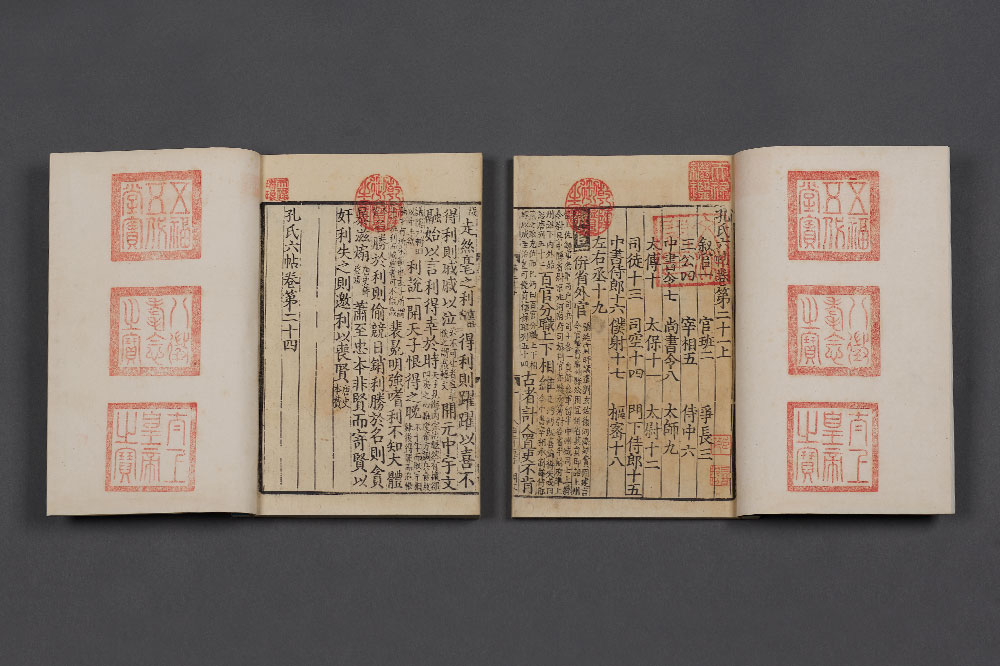

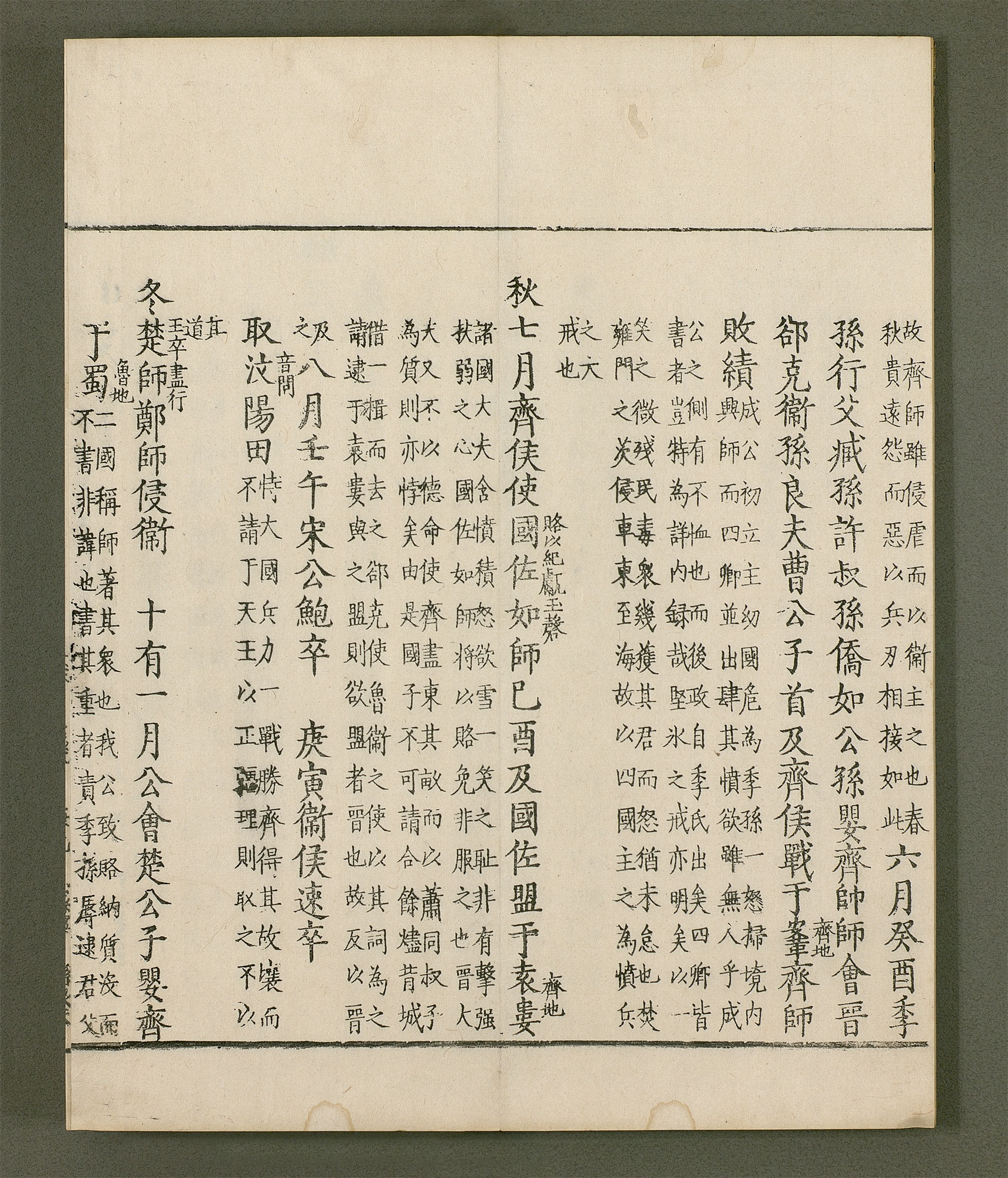

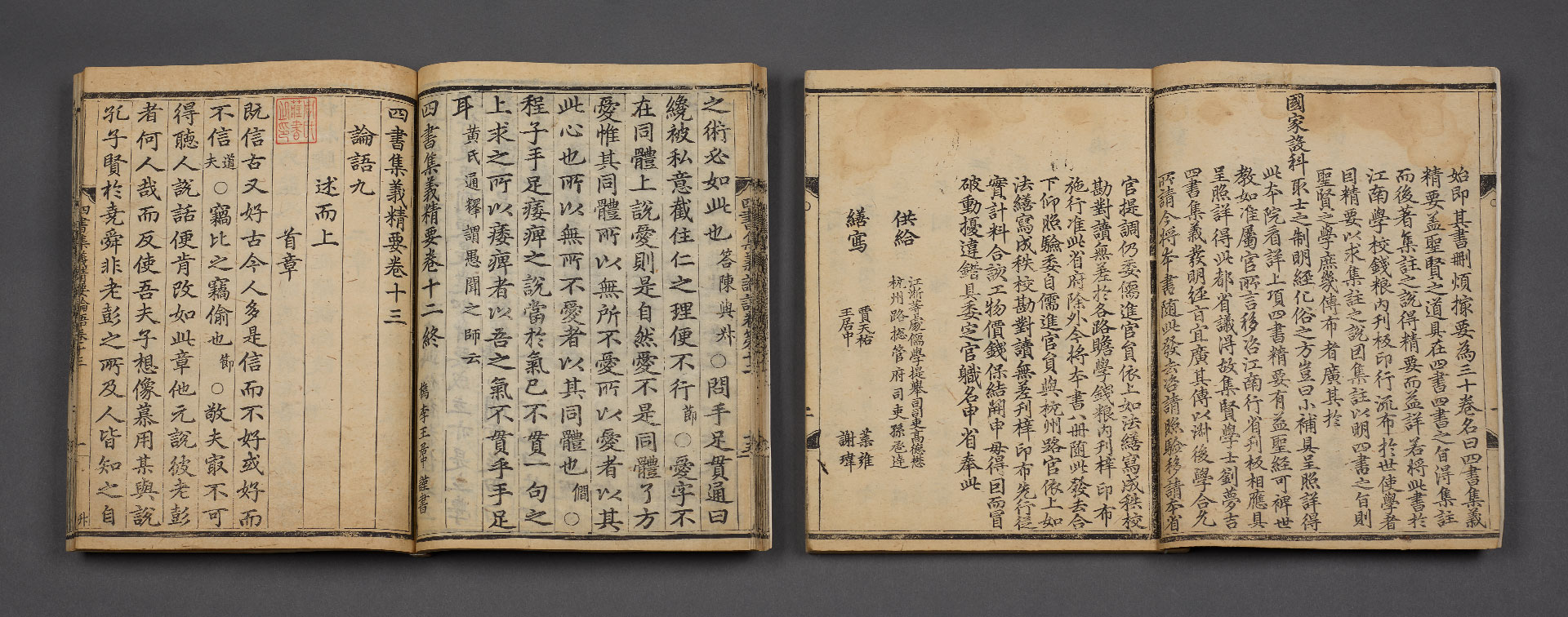

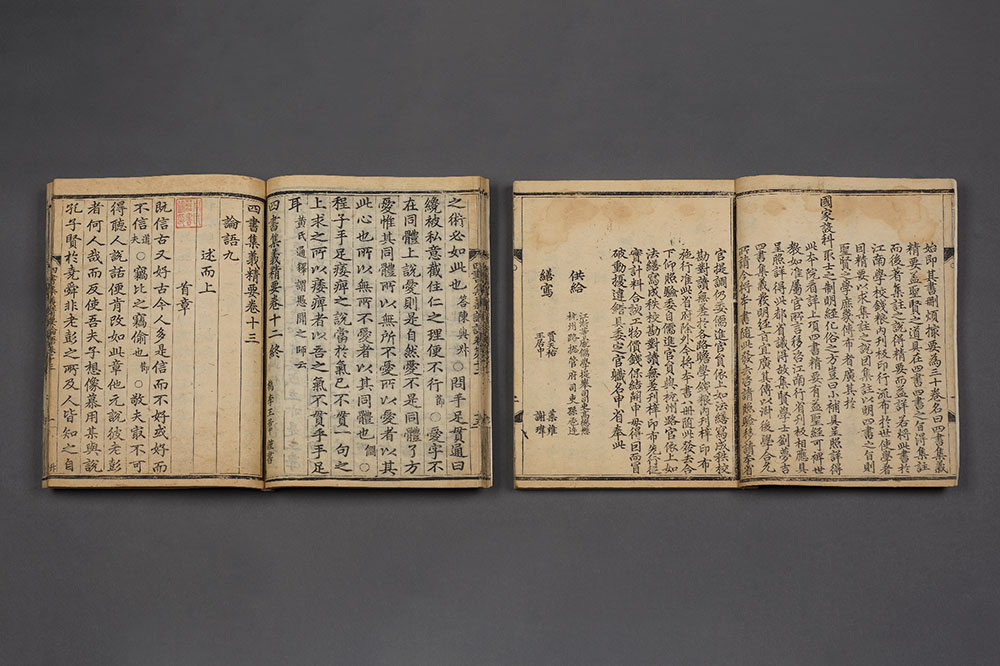

In 1797, all the books in Zhaoren Hall were destroyed by a fire in the Palace of Heavenly Purity. Efforts were quickly made to rebuild and edit the Tianlu Linlang Library collection, producing many fine works. Six Writings by Master Kong, the last-surviving Song dynasty edition of the work, boasts clean ink and paper, simple and unsophisticated fonts, and excellent initial printing. The work was rarely mentioned in both official and private bibliographies until its emergence in the early-Ming dynasty when it was recorded in The Bibliography of Wenyuan Pavilion (categorized under "bibliography No. 2, Letter ying"), revealing that it was already a rare and secret book at that time.

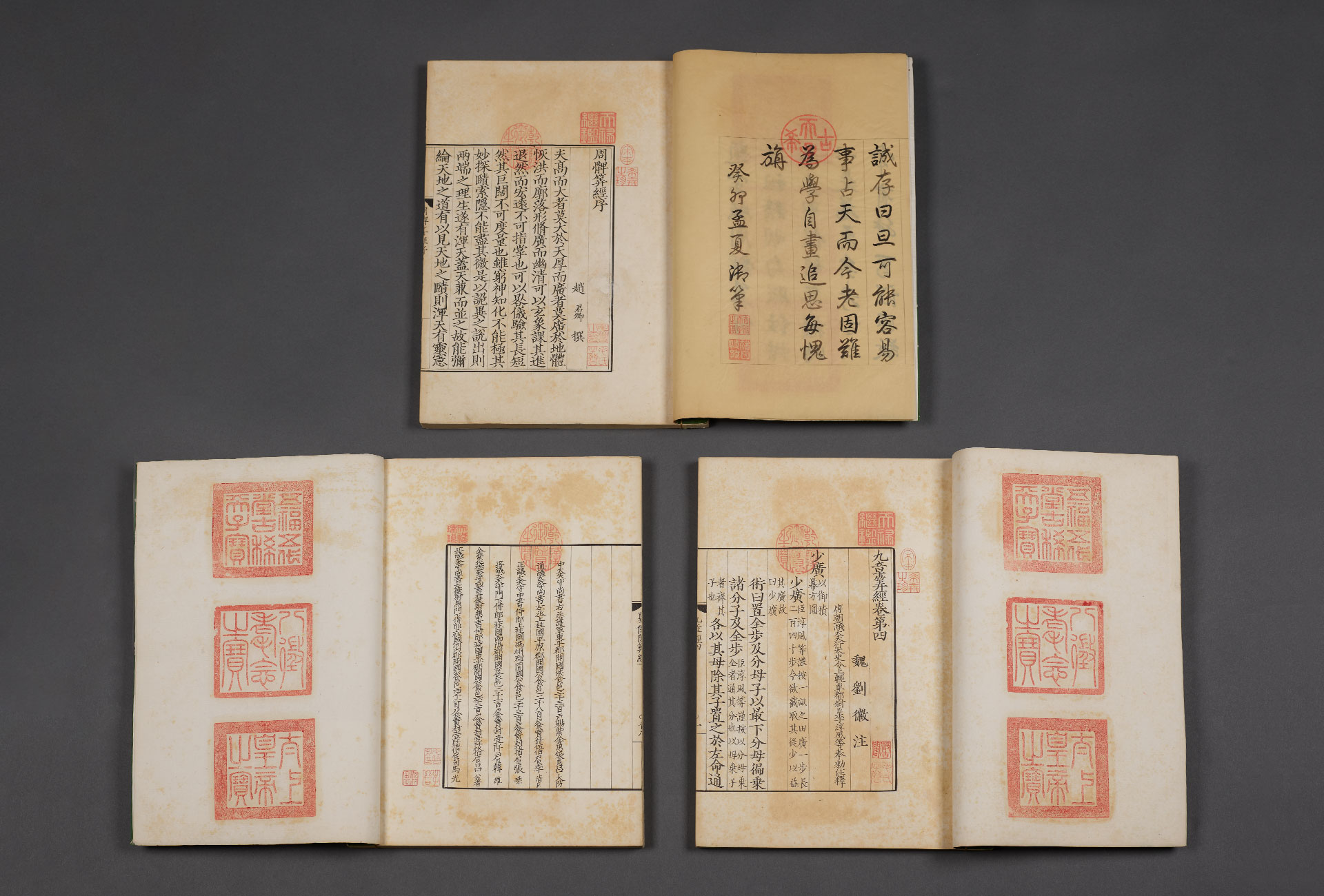

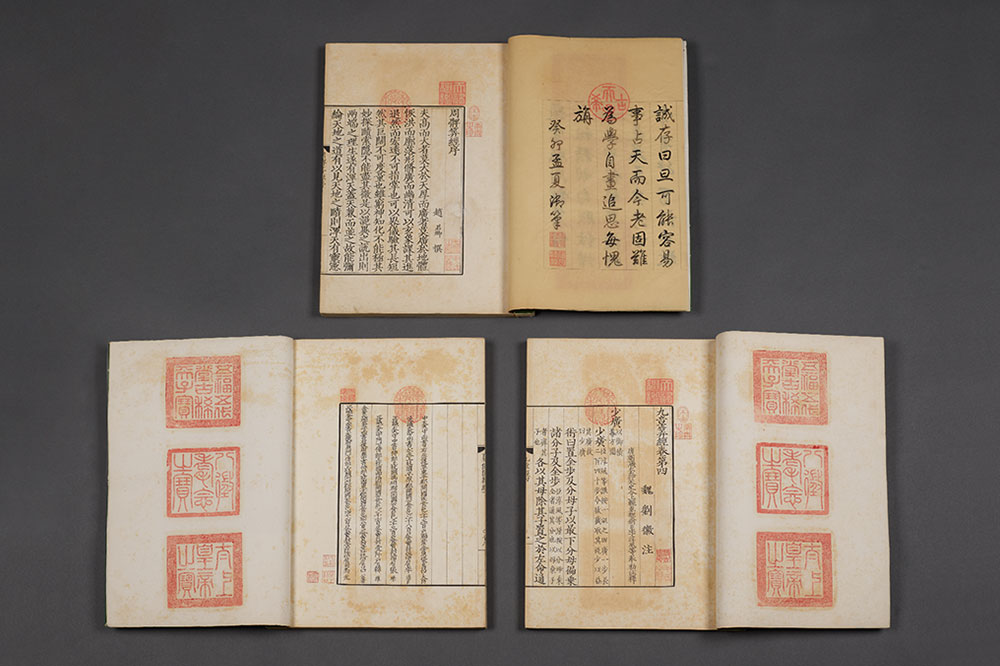

Song dynasty edition ancient books were difficult to preserve and rarely circulated; their collectors also often kept them secret. Mao Jin (1599-1659), a Jiangnan book collector and engraved book giant in the late-Ming dynasty, built a "Jiguge" that possessed a rich collection of Song and Yuan dynasty rare books and relied on the outline skills of expert calligraphers to preserve the original appearance of the engravings, giving birth to "Mao's handwritten copies" and "traced copies of Song dynasty edition," promoting the dissemination and appreciation of ancient books.

The Tianlu Linlang Library rare books and bibliographies collected during the Qianlong and Jiaqing eras adopted the concept preached by the "traced copies of the Song dynasty edition"; that is, calligraphy works of the Tang and Jin dynasties had an important position in the history of Chinese calligraphy, and that delicate, graceful, and practical works were far more valuable than formally carved works. The ranking of the aforementioned rare book and bibliography collection and display is second only to the books of the Song and Jin dynasty editions, in which the unique academic depths and values of traced copies were accentuated using the technical aspects of calligraphy, paper, and ink.

Suanjing Qizhong (Seven Arithmetical Classics)

- Annotated by Zhao Ying, et al., Han Dynasty

- Handwritten by Mao's Jiguge, Kangxi reign (1654-1722), Qing Dynasty, based on an imprint by Bao Huanzhi of Tingzhou (Fujian), in the 6th year of Jiading period (1213), which was reprinted from the edition of State Secretariat during the Yuanfeng period (1078-1085), Song Dynasty

The Jiaqing emperor (1760-1820; personal name "Aisin-Gioro Yongyan") restored the Zhaoren Hall Tianlu Linlang Library for his father, the Qianlong Emperor, and followed his father's example by continuing to collect rare books. All the rare books collected were redecorated, their labeling and protective cover-related regulations were formulated, and their pages were stamped "imperial treasure of Jiaqing reign" to distinguish them from other rare books. Nonetheless, there were no complete rare book bibliographies, and only about a dozen books are known to have seals and are verifiable. Among said roughly a dozen of books, the National Palace Museum possesses seven, most of which maintain the original characteristics of Qing court decorations.

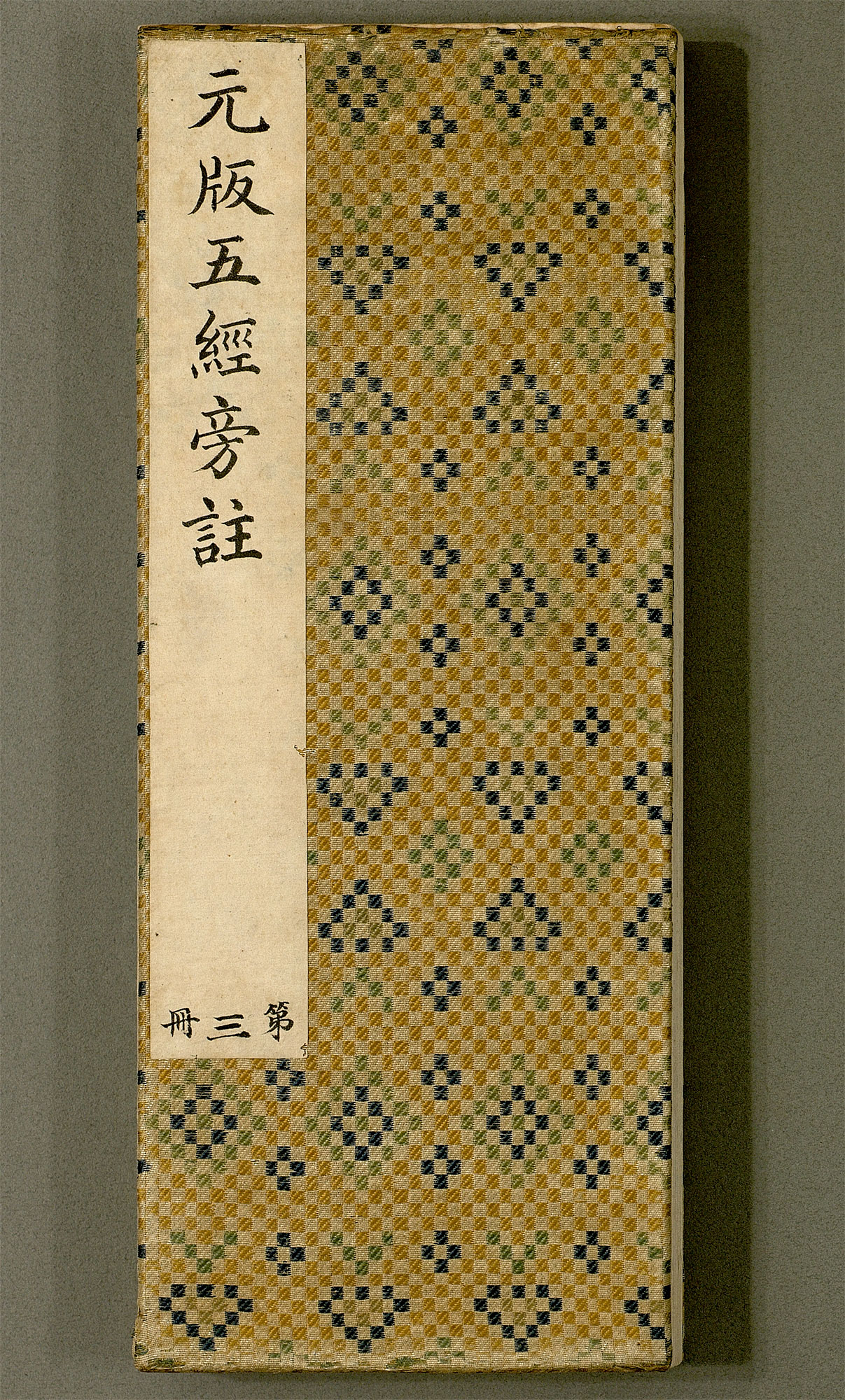

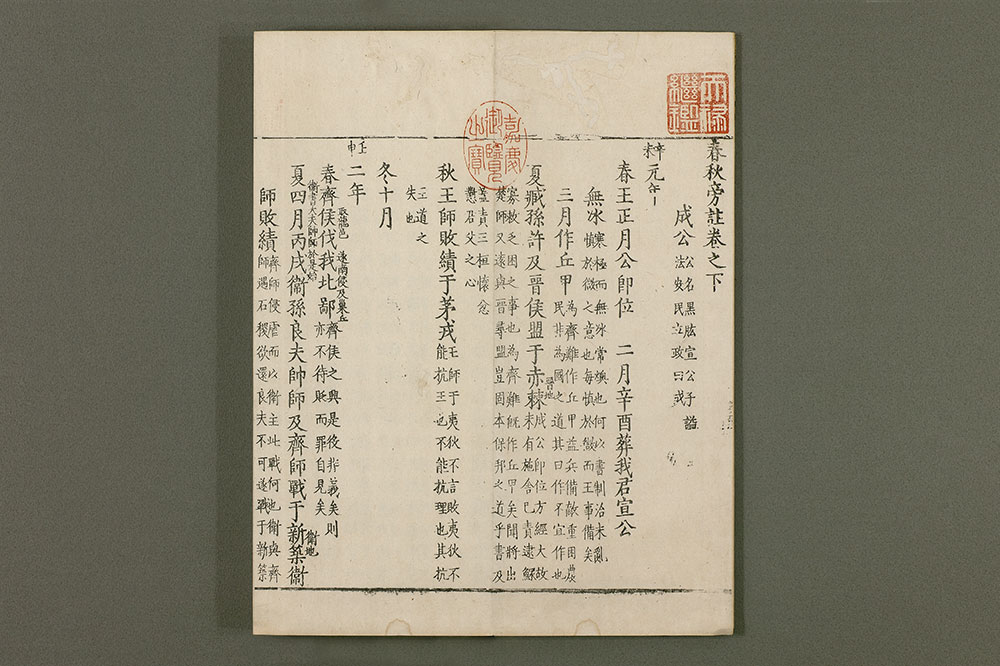

In addition to the lack of book collection, the engraving quality and edition assessment results of the aforementioned books pale in comparison to previous ones. The Song dynasty edition of Supplemented Writings of Master Yu-zhang examined and approved by Song dynasty ministers is actually that of the Qinglong era without postscripts. Also, the Yuan dynasty edition of The Five Classics with Annotations feature only fonts and paper, showing the characteristics of publications released in the mid- and late-Ming dynasty.

In 1894, the year when Empress Dowager Cixi celebrated her 60th birthday, the Guangxu Emperor (1871-1908; personal name "Zaitian") conducted a comprehensive inventory check of the books remaining in the Tianlu Linlang Library at the suggestion of his teacher Weng Tonghe (1830-1904). The inventory check then extended to the organizing of the books collected in other palaces and pavilions. Before and after the First Sino-Japanese War, the Guangxu Emperor decreed the Southern Study Hanlin Academy to move the Song and Yuan rare books discovered to the Imperial Study Room in the back hall of the Jingyang Palace, attempting to create a new era of imperial rare book collection.

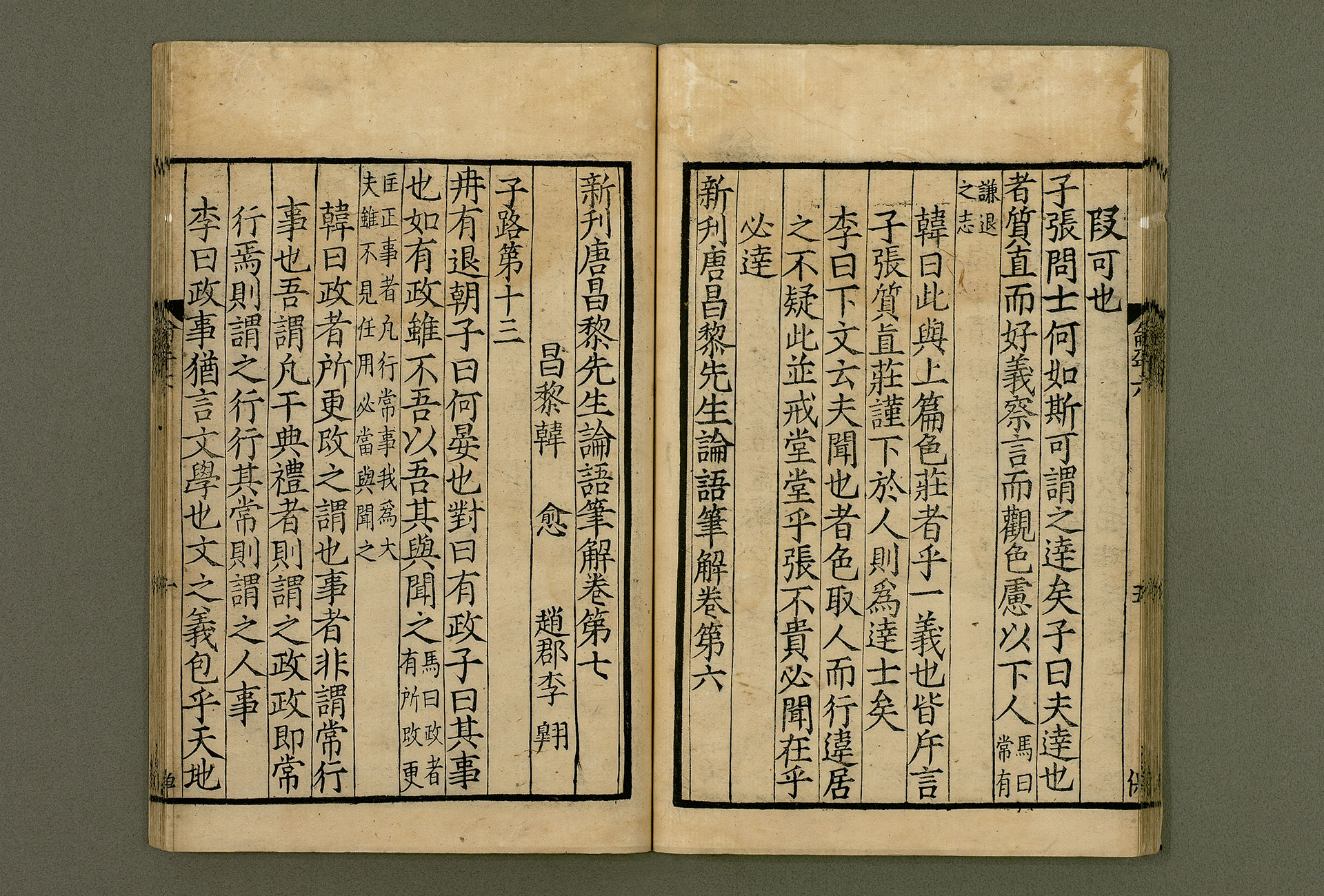

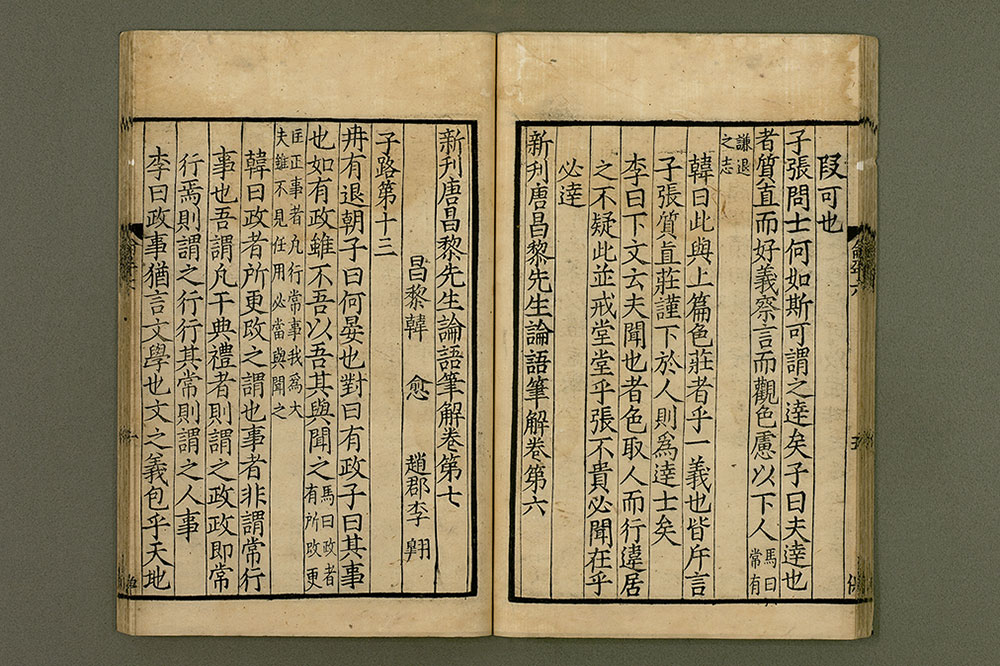

The Imperial Study Room special collection in the Guangxu era is filled with never-seen-before books. Examples include The New Edition of Annotations toward the Analects of Confucius written by Master Chang‐li. When compiling/editing the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries, the librarians most frequently saw the Tianyi Pavilion (a pavilion founded by Fan Qin) imprint edition, making the discovery of the first-print copy of the Southern Song dynasty Shu edition remarkably exquisite. The Yuan edition of Essentials to the Collected Meaning of the Four Books in the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries had 11 missing volumes. Nevertheless, the court possessed the world's remaining 36 complete volumes that have lasted, since the redecoration of the Changchun Garden in 1716, for nearly 200 years. The Guangxu Emperor's series of actions to sort out the palace book collection has become an unparalleled endeavor in imperial rare book collection, and has created an academic "treasure chest" for future generations to explore.