Religious Tolerance

The Qing Empire ruled over a vast expanse of territory that was home to many ethnic groups holding various religious beliefs. Before their conquest of China proper, the Manchus inherited the dominant Shamanism of the Jurchen people. However, in the early 17th century, under the influence of nearby Mongols, they adopted Tibetan Buddhism as their principal religion and supported the Gelug School (Yellow Hat Sect) and its reincarnated high monks including the Dalai, the Panchen, the Changkya, and the Jebtsundamba. The Gelug School thus became the shared religious orthodoxy of the Manchus, the Mongols, and the Tibetans. While the Qing emperors adopted Tibetan Buddhism, they did not aggressively push the faith in regions inhabited by other ethnic groups, as the Mongol emperors of the Yuan dynasty had. The framework of Qing court policy continued to allow the development of Chinese Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism among the Han Chinese and Islam among the peoples in the northwest. This religious diversity was also reflected in the history and decorations of the Chengde Summer Resort.

Sino-Tibetan Buddhism

Prior to the Battle of Shanhai Pass, the Manchus believed in Shamanism. Later, neighboring Mongolians introduced them to Tibetan Buddhism. After the Battle of Shanhai Pass, the Qing emperor deliberately made the Gelug school (Yellow Hat school) of Tibetan Buddhism the political school in the Tibetan area, resulting in the school becoming the common religion among Manchus, Mongolians, and Tibetans.

Although Qing emperors such as Emperors Shunzhi and Yongzheng were highly familiar with Chinese Buddhism, the Qing court still inherited Ming dynasty management policies, adopted control strategies, and strictly prohibited unofficial exchanges between Chinese and Tibetan Buddhism. The two Buddhist artifacts on display here were originally found in the collection of the Summer Resort, revealing the unique Sino-Tibetan Buddhism that existed only in the Qing court during the Qing dynasty.

Chinese pavilion-shaped niche of red lacquer, with gold-lacquered wooden Amitāyus Buddha

- Produced by Imperial Workshop

- Qing court, 18th century

This niche, made using red lacquer techniques, is hexagonal pavilion-shaped and features double eaves as well as passionflower and geometric brocade patterns. The top of the niche, which covers the middle eave, is identical to that of a litter, and the pavilion side walls have plate-like fitting with glass windows. Columns are erected along the corridor, and a sumeru pedestal is used as the base. The niche door is removable. Inside the niche is a gold-lacquered wooden Amitāyus Buddha sitting on a red lotus seat, wearing long blue hair, two yingluo, a silk textile, and a crown containing five Buddhas; sitting on Its knees; having one of Its hands lie on top of the other to hold the bottle of longevity; showing round eyebrows; and closing Its eyes. The deity is skinny, resembling the body shape of Buddhas created during the late Qianlong period.

Carved cinnabar lacquer bowl with seven Buddhas, on red lacquer lotus-shaped stand

- Qing dynasty, 18th century

The bowl is made with red lacquer and has a round base and a lotus-shaped stand. The primer and surface paint are dark green and red in color, respectively. The outer surface of the bowl is decorated with seven Buddhas in red lacquer, seated on a lotus platform, and surrounded by clouds. The names of the seven Buddhas and related verses are carved. In "Inscription on a Pagoda Temple with Seven Buddhas" written by Emperor Qianlong in 1777, he mentioned that he once received a thangka painting scroll with seven Buddhas from the Panchen Lama. However, unfamiliar with the seven Buddhas, the emperor asked Changkya Rölpé Dorjé, the principal Tibetan Buddhist teacher in the Qing court, and studied Tibetan and Chinese scriptures to obtain relevant information. This bowl was made to record the aforementioned incident.

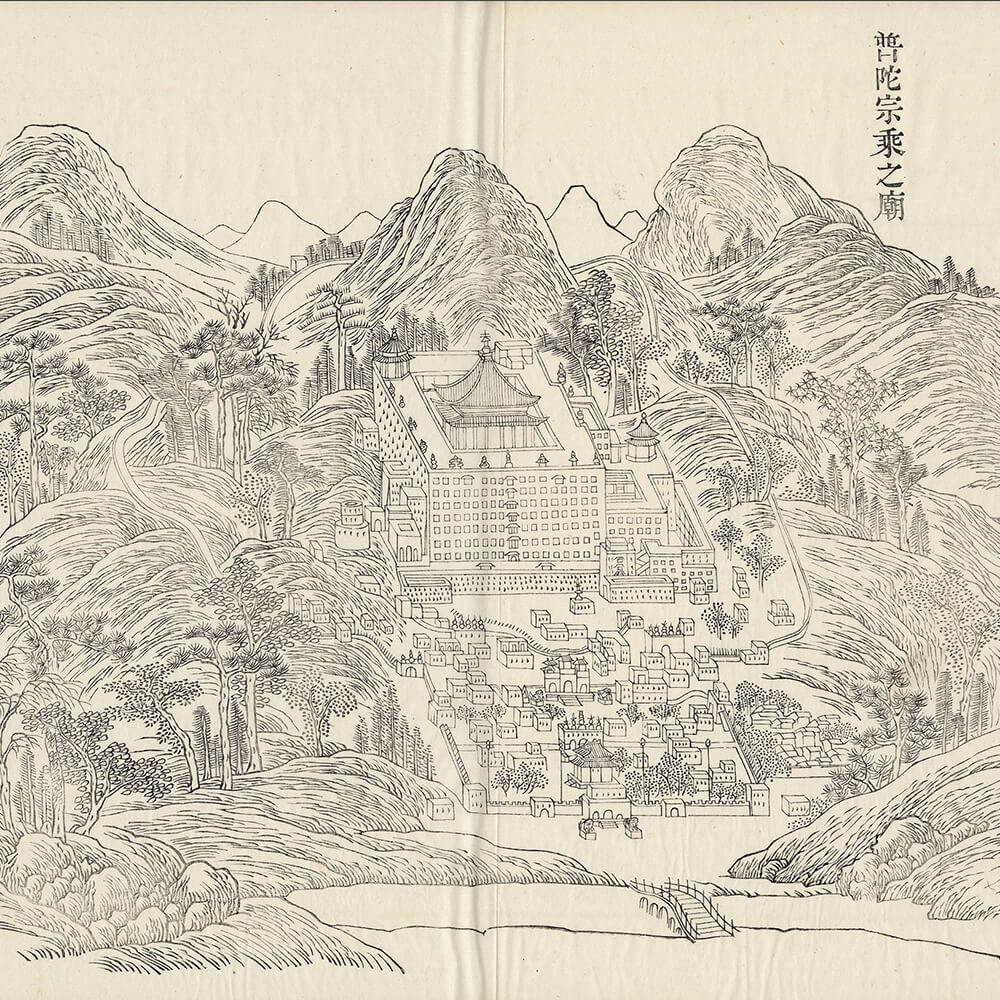

Illustration of the the Putuo Zongcheng Temple

- From fascicle 80 of Qinding Jehol Zhi (Imperially Endorsed Local Gazetteer of Jehol)

- Compiled by He Shen, et al., on imperial order

- Imprint by the Imperial Printing Office at Wuyingdian Hall, 46th year of the Qianlong reign (1781), Qing dynasty

The Putuo Zongcheng Temple was built to commemorate the 80th birthday of Emperor Qianlong's mother Empress Dowager Chongqing. Construction of the temple began in March 1767 and ended in August 1771. Imitating the Potala Palace in Lhasa, this temple is the largest among Acht Äußere Tempel. The words "putuo zongcheng" (in Chinese) and "potala" (in Tibetan) share the same origin as they both mean the holy place where Guanyin lives. In front of the temple is a Tibetan-style pagoda of five colors. The colors, starting from west to the east, are red, green, yellow, white, and black. The white platform near the temple entrance is built using colored glaze tiles. Although the temple appears to be similar to Kadam pagodas, it is unique in its magnificent decorations.

Dialogue with the Gelug

- From fascicle 3 of Yeolha Ilgi (The Jehol Diary)

- Written by Bak Jiwon, the Joseon dynasty

- Handwritten edition, Qing dynasty

In The Jehol Diary, Bak Jiwon described how he witnessed the meeting between Emperor Qianlong and the 6th Panchen Lama. As a Korean literatus who practiced Confucianism, Bak Jiwon had a lot of misunderstanding about why Manchurian emperors respected the "yellow religion" and what the meaning of "living Buddha" was because of his cultural prejudice and linguistic misinterpretation. However, his observation of why Qing emperors stayed at the Summer Resort every year was keen: "The emperors use visits to the Summer Resort as a reason to demonstrate his military strength to Mongolia."