Introduction

To meet the need for recording information and ideas, unique forms of calligraphy (the art of writing) have been part of the Chinese cultural tradition through the ages. Naturally finding applications in daily life, calligraphy still serves as a continuous link between the past and the present. The development of calligraphy, long a subject of interest in Chinese culture, is the theme of this exhibit, which presents to the public selections from the National Palace Museum collection arranged in chronological order for a general overview.

The dynasties of the Qin (221-206 BCE) and Han (206 BCE-220 CE) represent a crucial era in the history of Chinese calligraphy. On the one hand, diverse forms of brushed and engraved "ancient writing" and "large seal" scripts were unified into a standard type known as "small seal." On the other hand, the process of abbreviating and adapting seal script to form a new one known as "clerical" (emerging previously in the Eastern Zhou dynasty) was finalized, thereby creating a universal script in the Han dynasty. In the trend towards abbreviation and brevity in writing, clerical script continued to evolve and eventually led to the formation of "cursive," "running," and "standard" script. Since changes in writing did not take place overnight, several transitional styles and mixed scripts appeared in the chaotic post-Han period, but these transformations eventually led to established forms for brush strokes and characters.

The dynasties of the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) represent another important period in Chinese calligraphy. Unification of the country brought calligraphic styles of the north and south together as brushwork methods became increasingly complete. Starting from this time, standard script would become the universal form through the ages. In the Song dynasty (960-1279), the tradition of engraving modelbook copies became a popular way to preserve the works of ancient masters. Song scholar-artists, however, were not satisfied with just following tradition, for they considered calligraphy also as a means of creative and personal expression.

Revivalist calligraphers of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), in turning to and advocating revivalism, further developed the classical traditions of the Jin and Tang dynasties. At the same time, notions of artistic freedom and liberation from rules in calligraphy also gained momentum, becoming a leading trend in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Among the diverse manners of this period, the elegant freedom of semi-cursive script contrasts dramatically with more conservative manners. Thus, calligraphers with their own styles formed individual paths that were not overshadowed by the mainstream of the time.

Starting in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), scholars increasingly turned to inspiration from the rich resource of ancient works inscribed with seal and clerical script. Influenced by an atmosphere of closely studying these antiquities, Qing scholars became familiar with steles and helped create a trend in calligraphy that complemented the Modelbook school. Thus, the Stele school formed yet another link between past and present in its approach to tradition, in which seal and clerical script became sources of innovation in Chinese calligraphy.

Selections

-

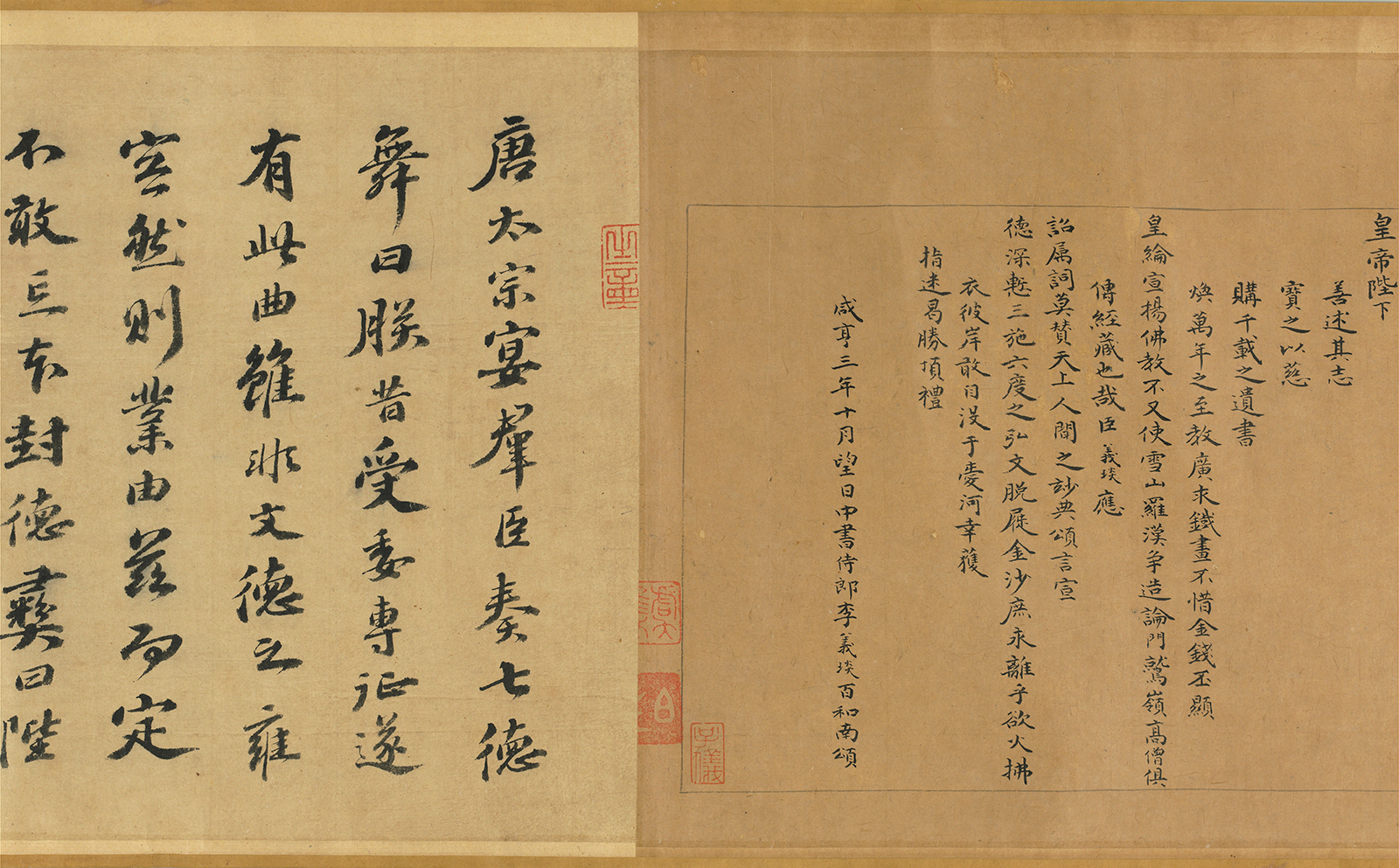

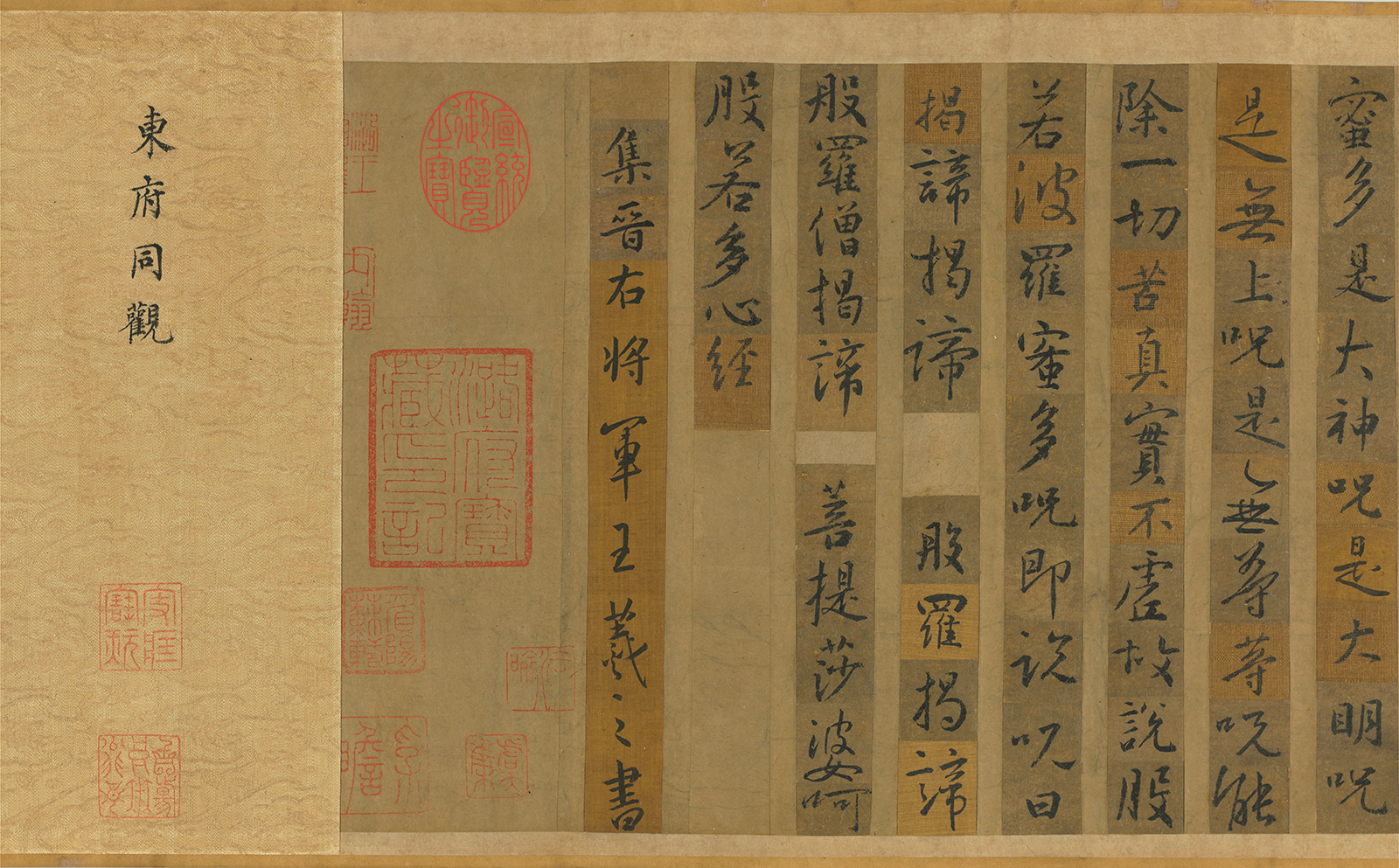

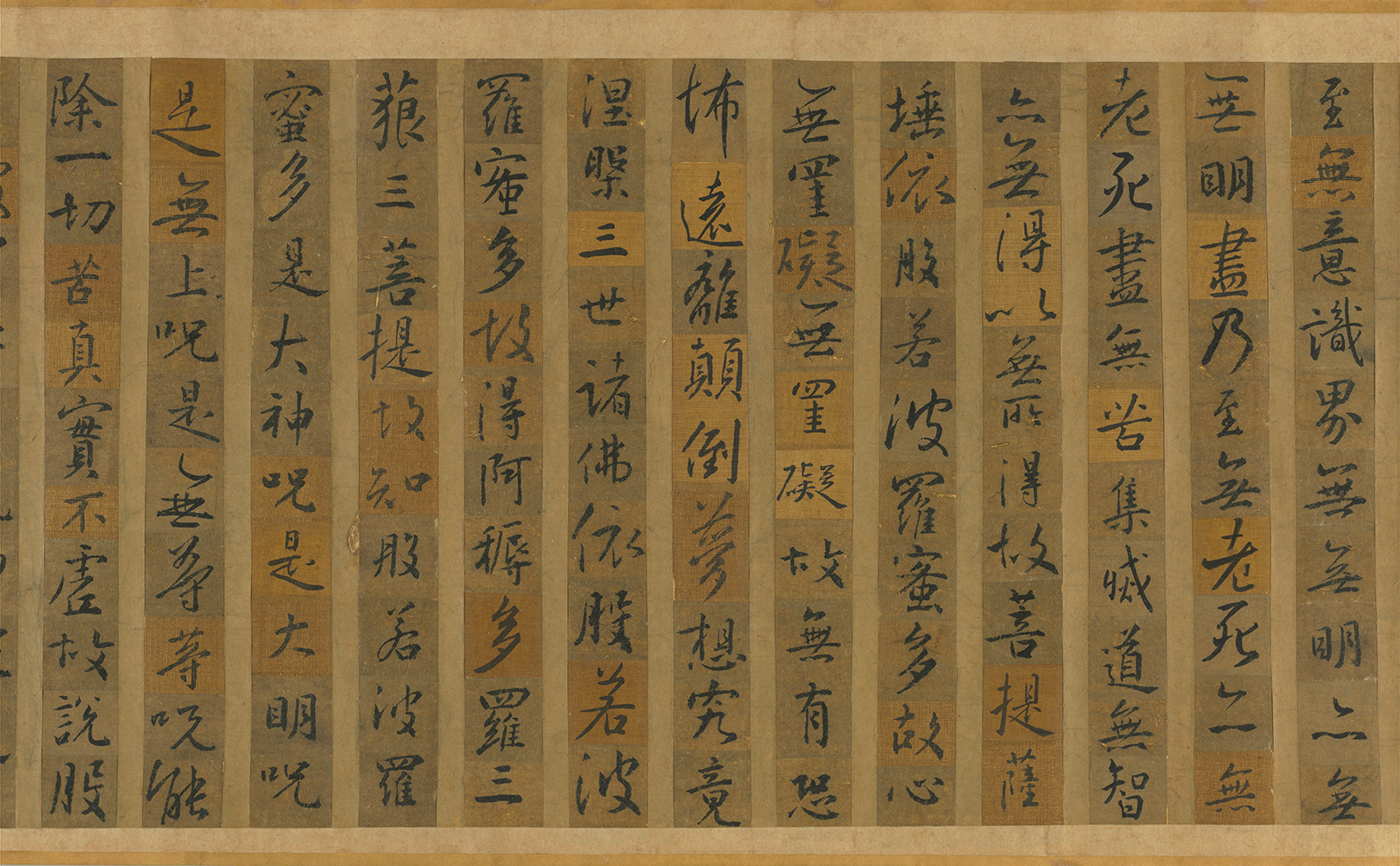

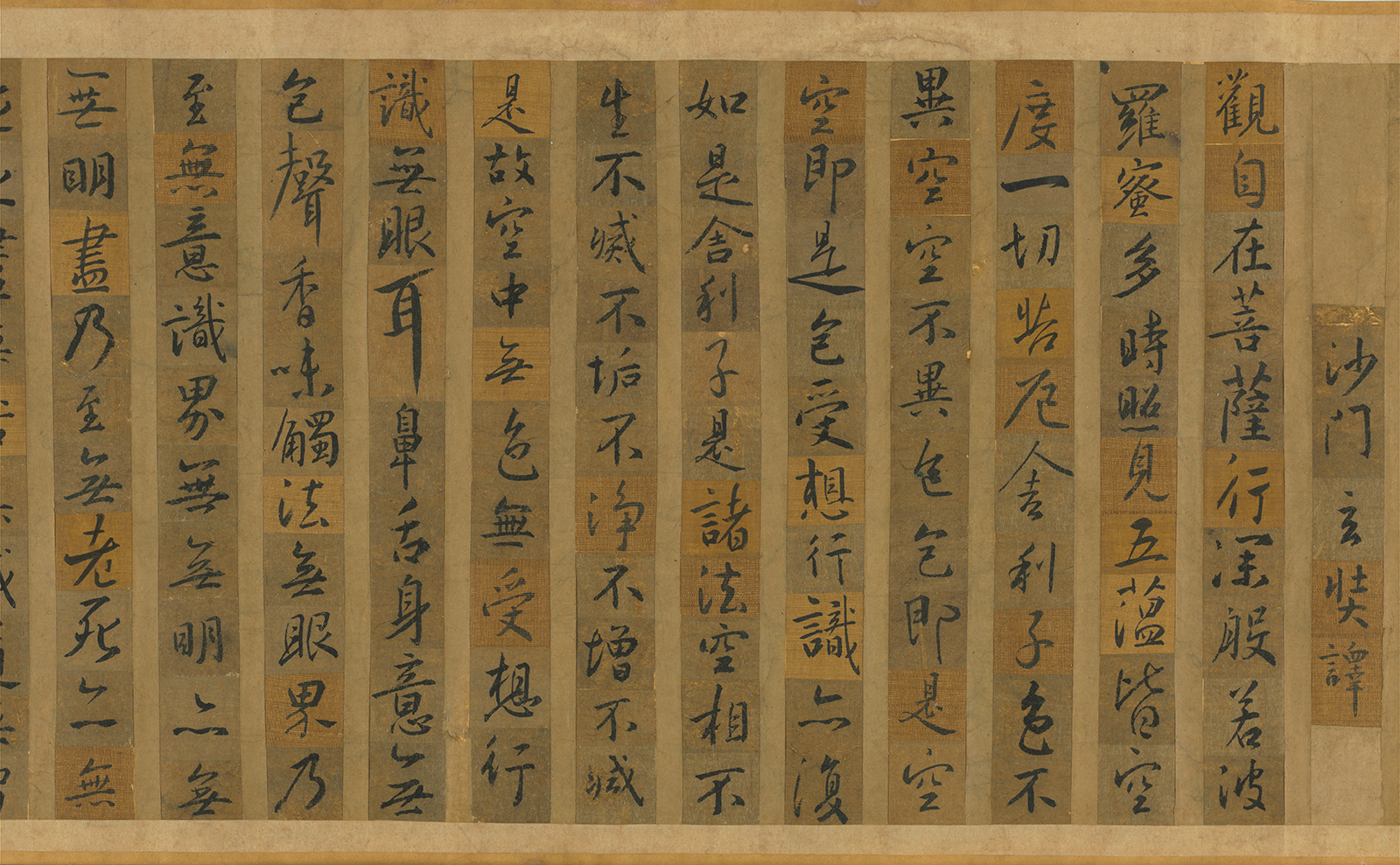

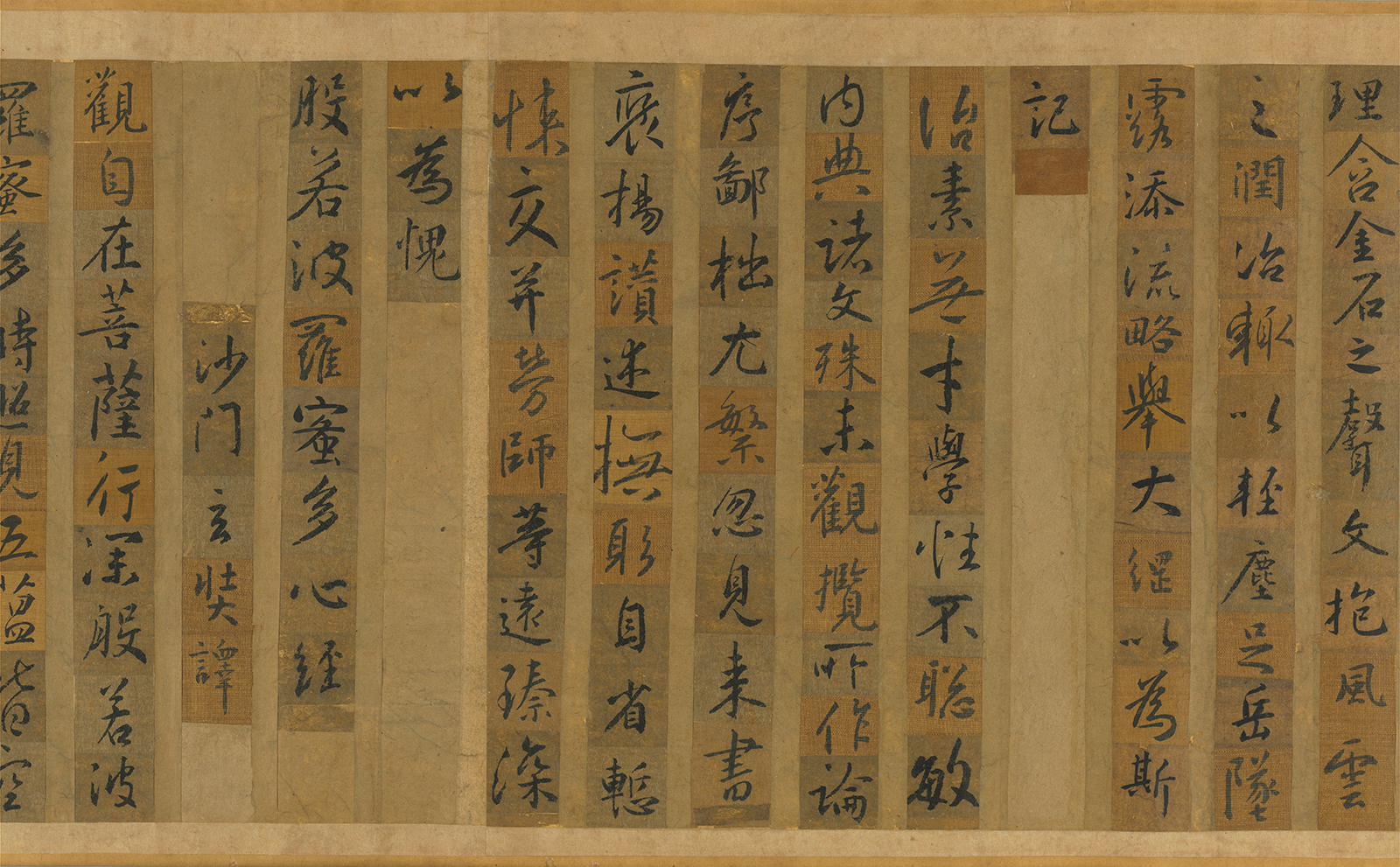

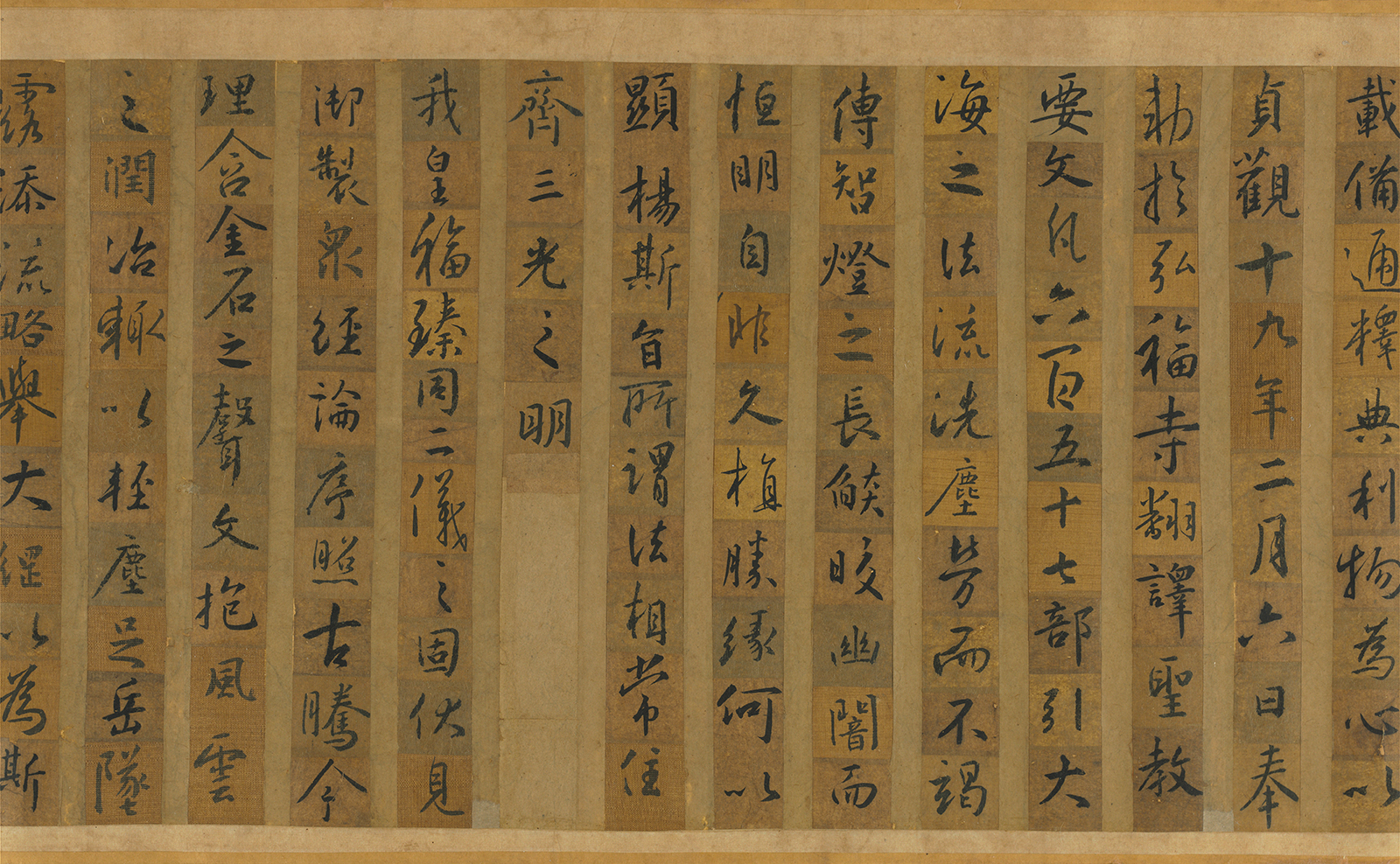

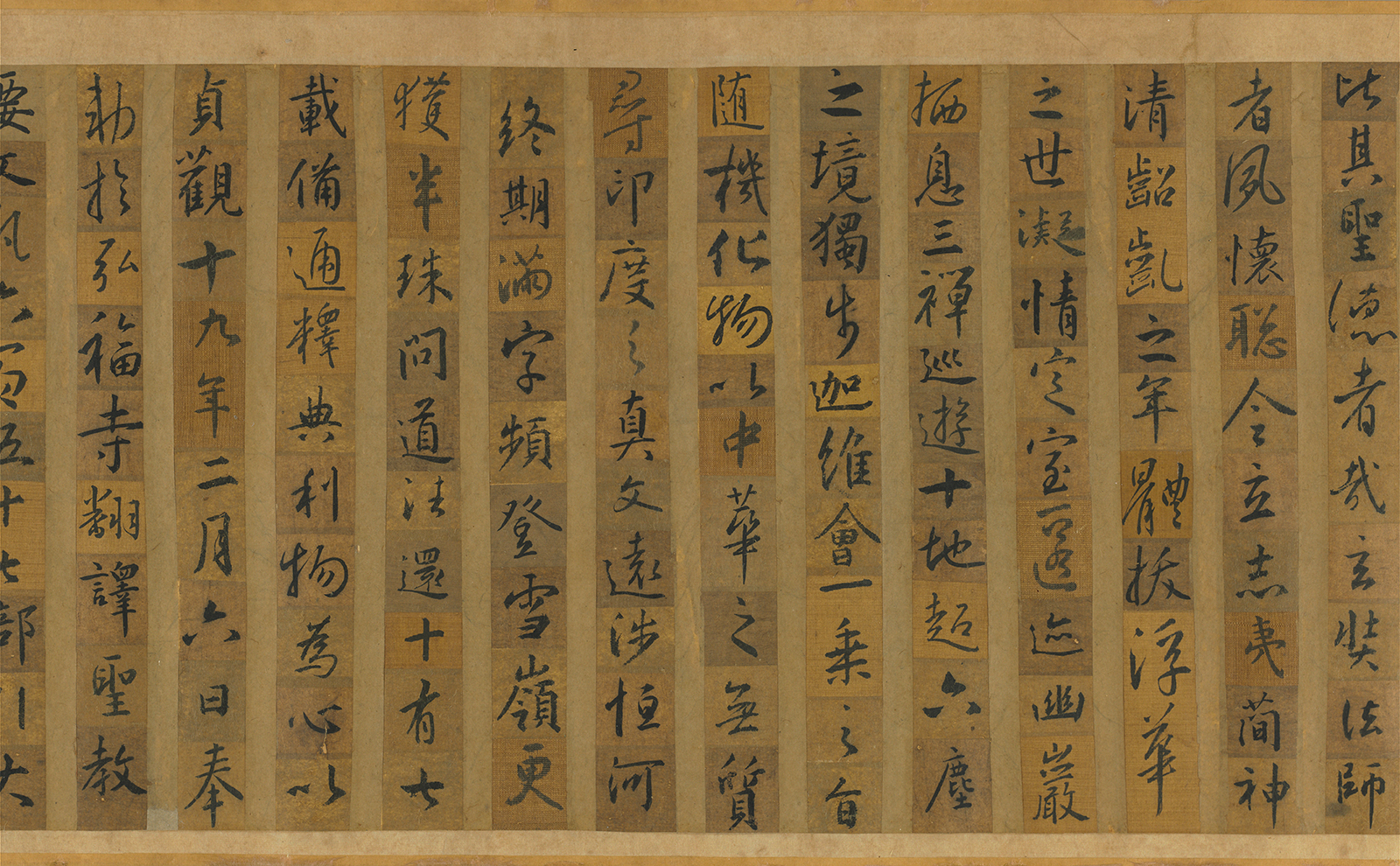

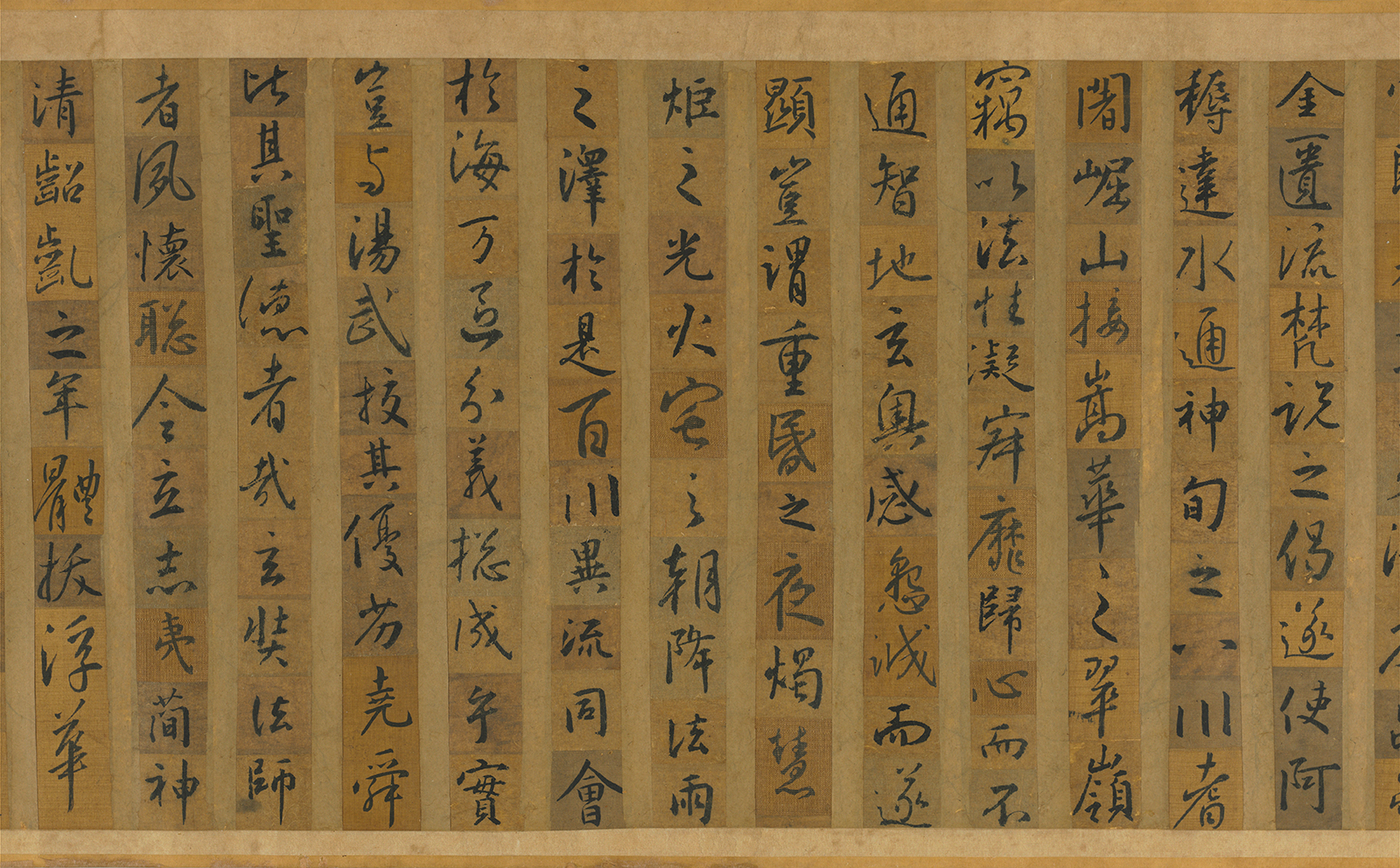

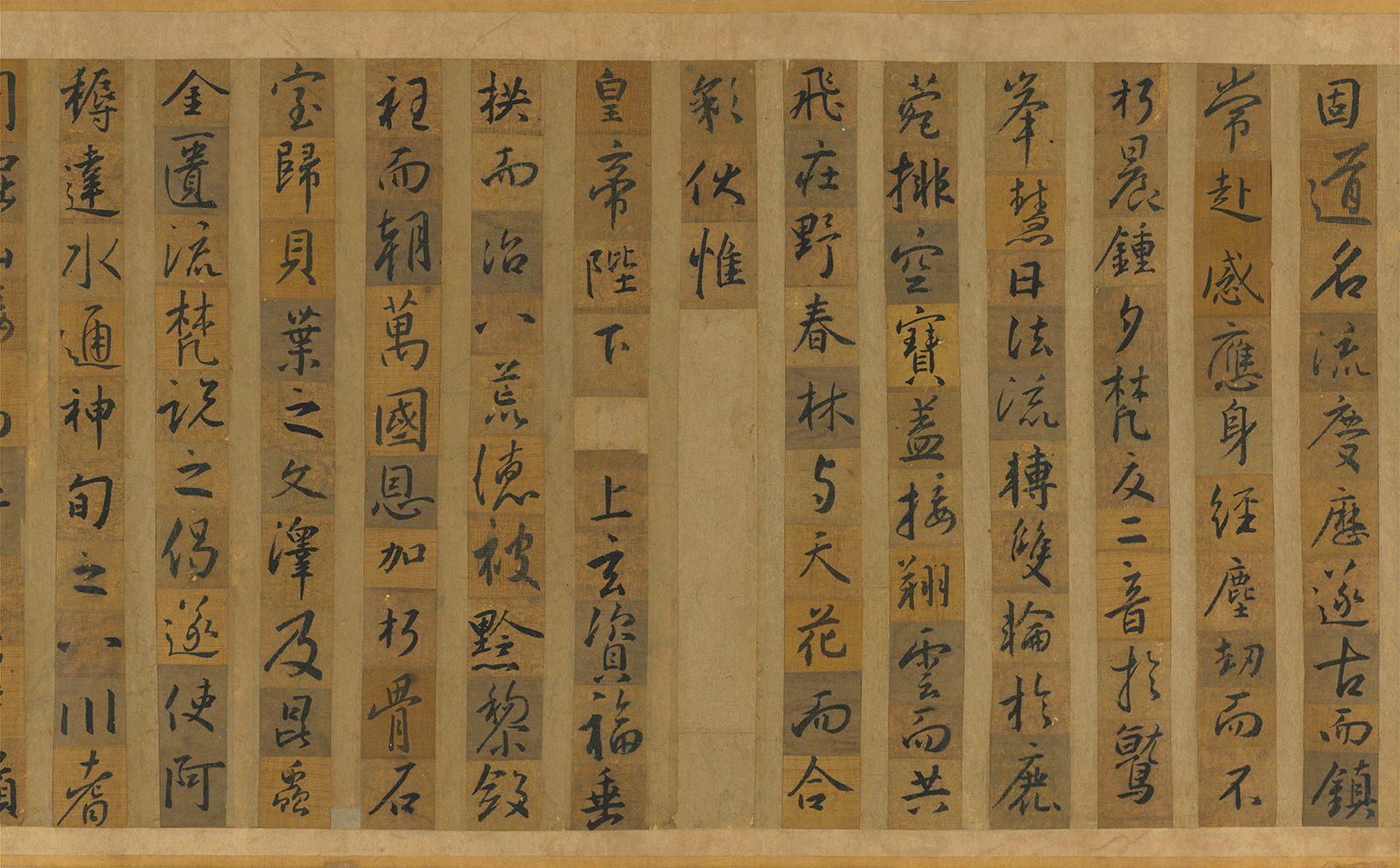

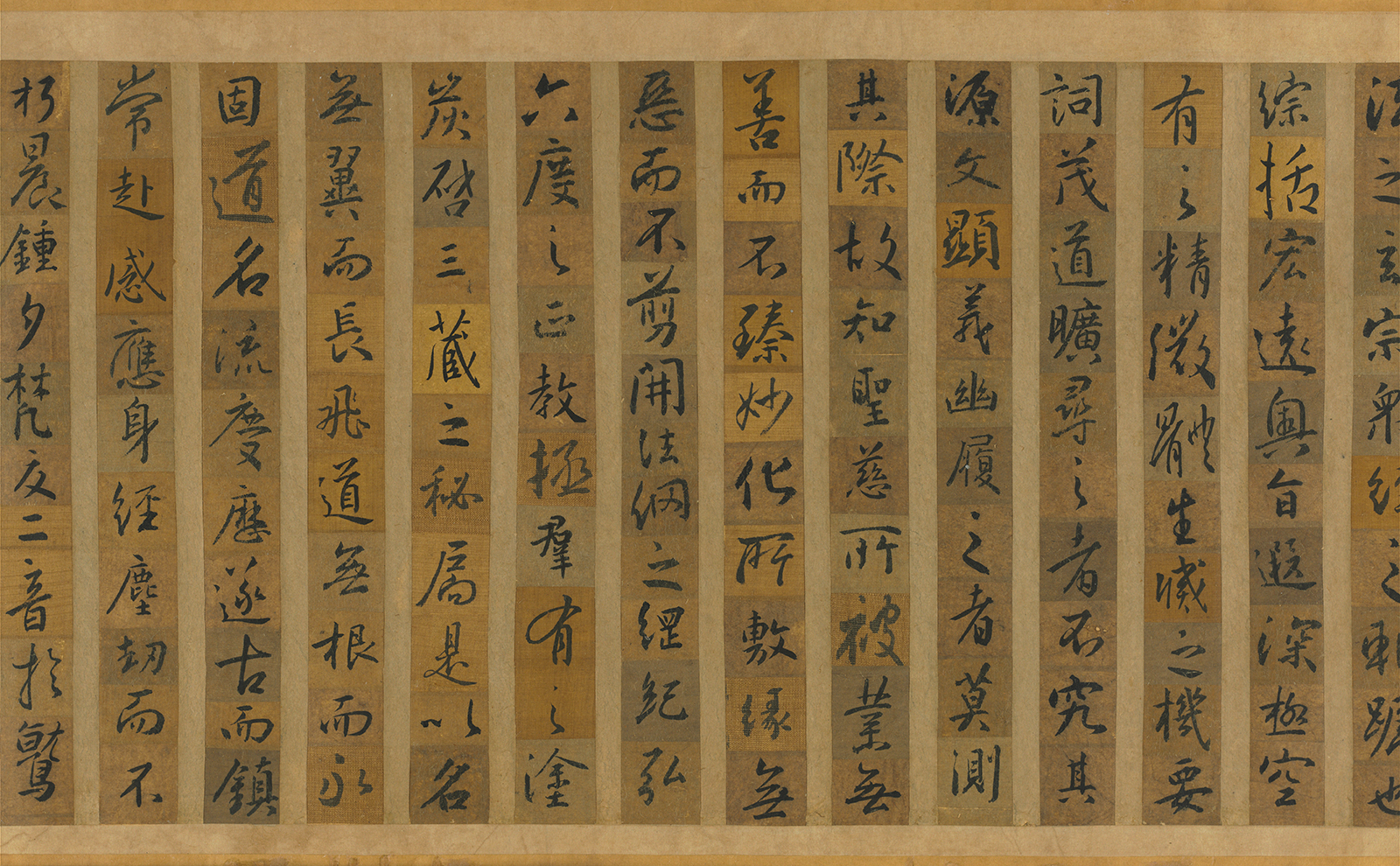

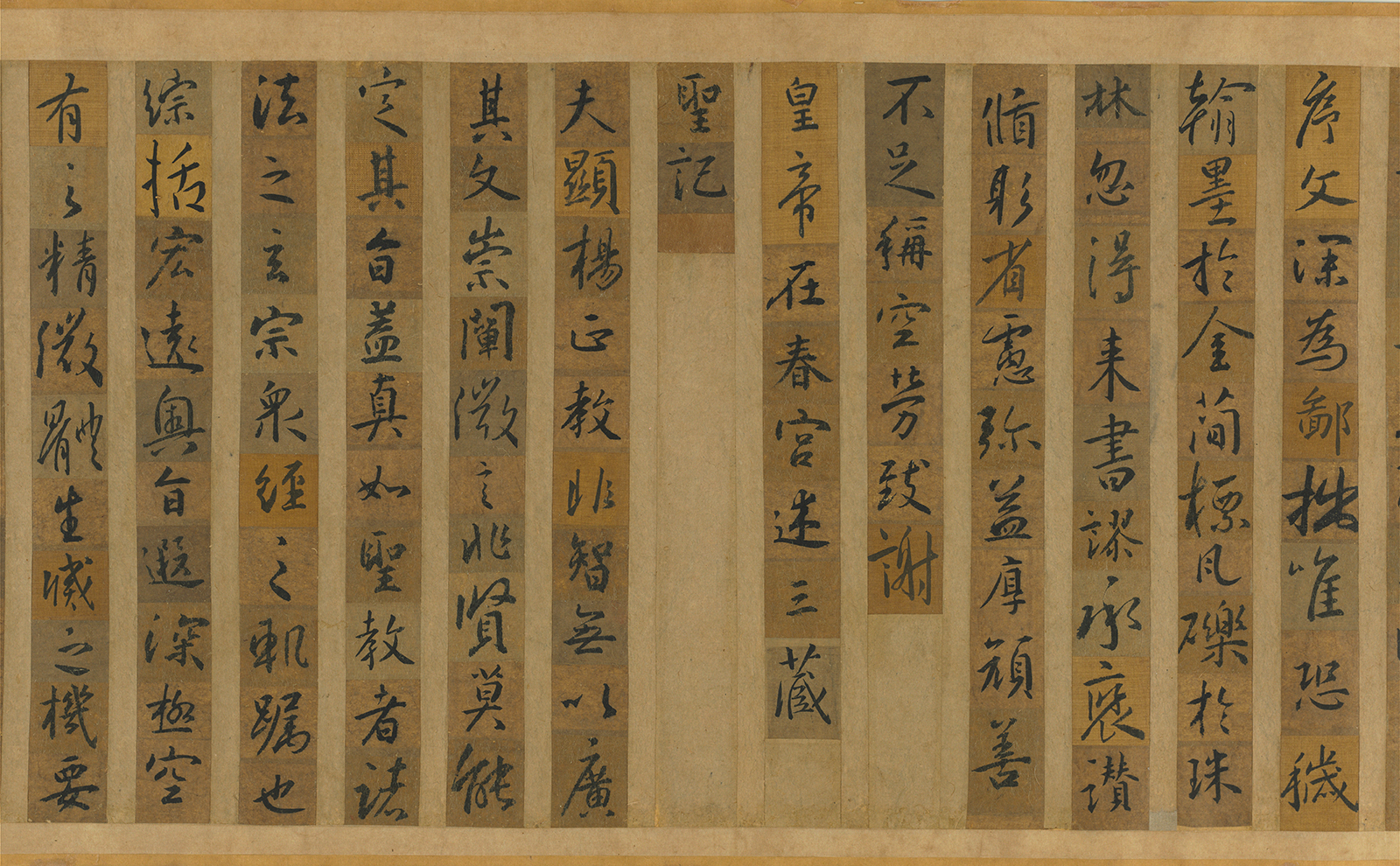

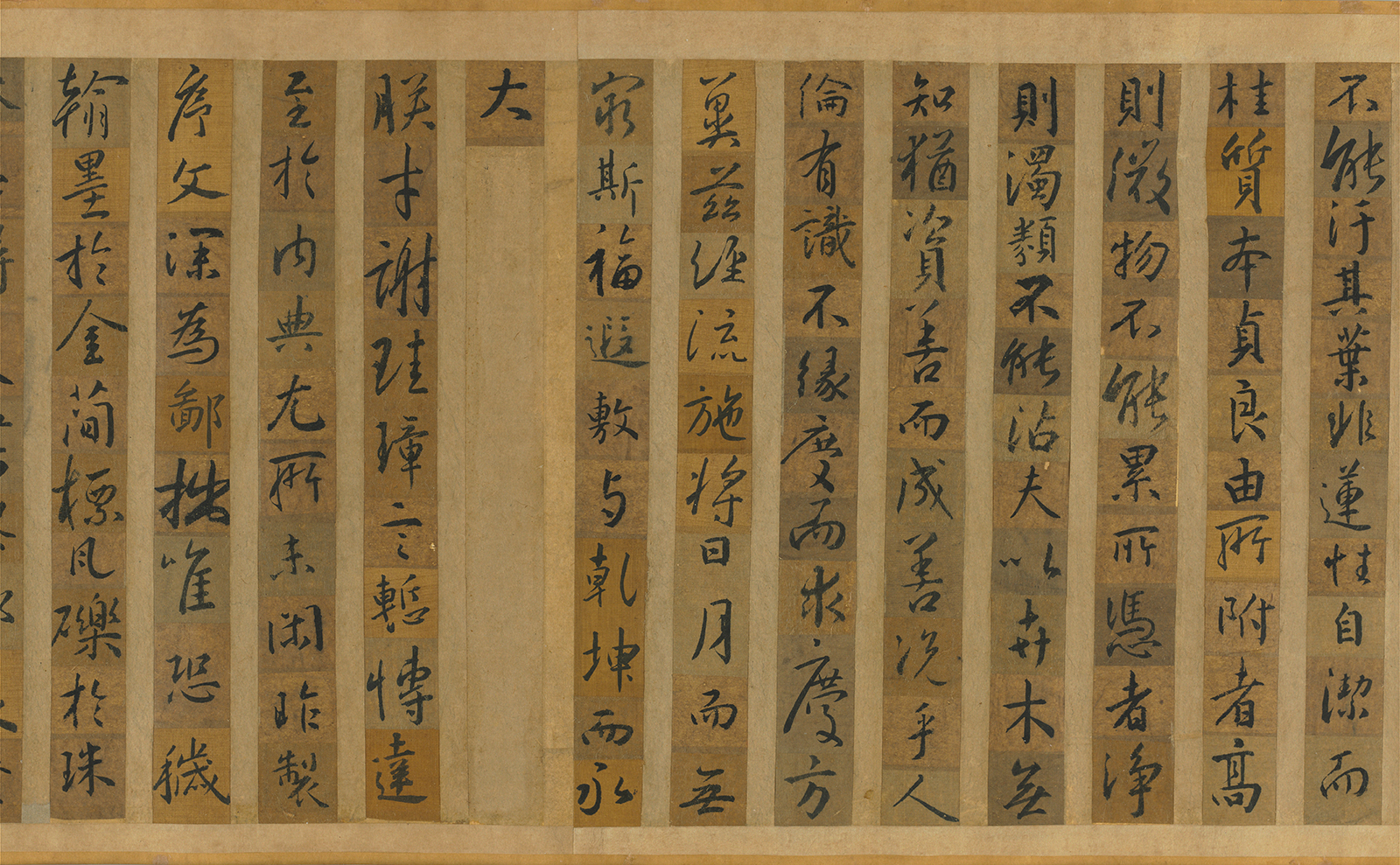

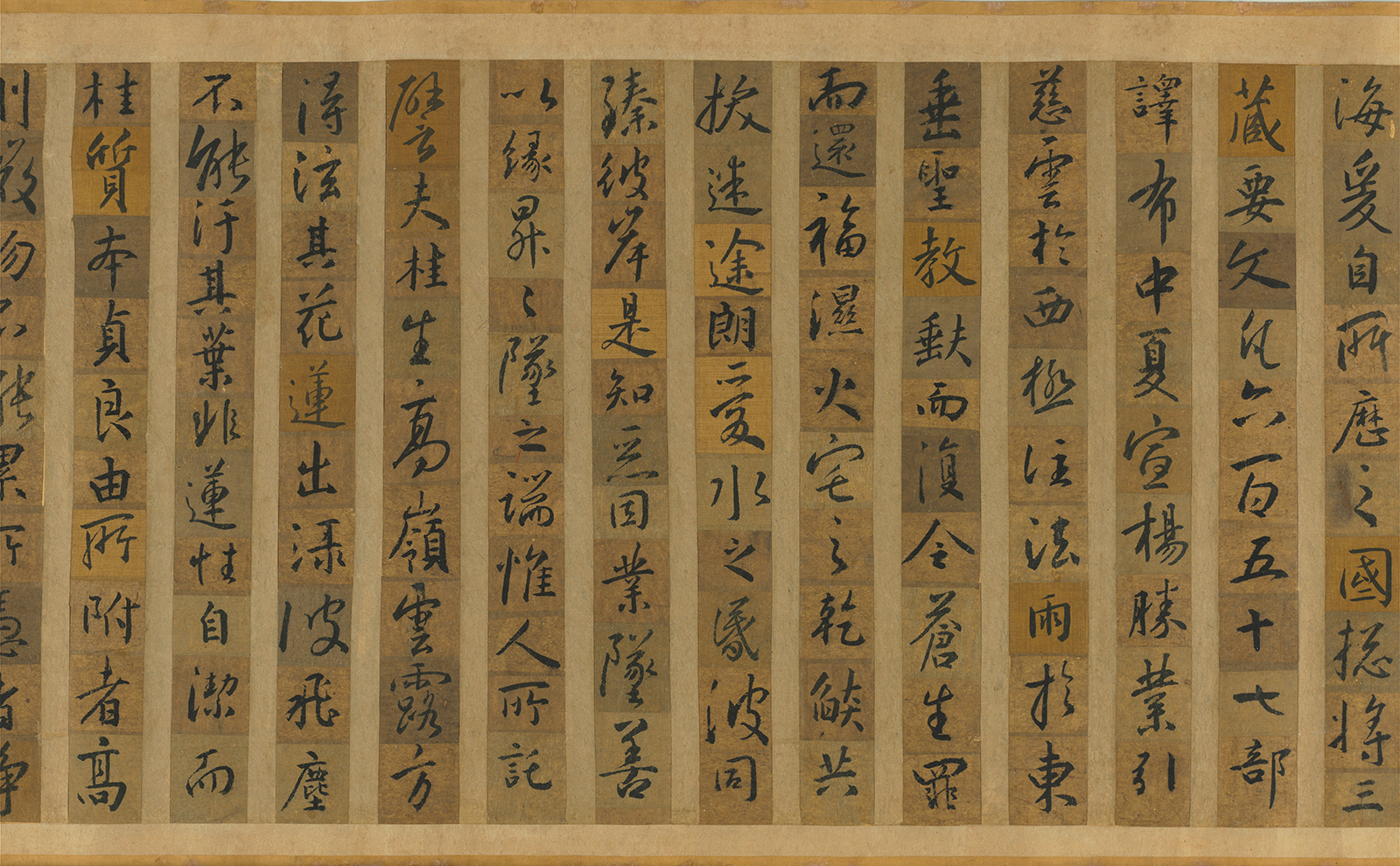

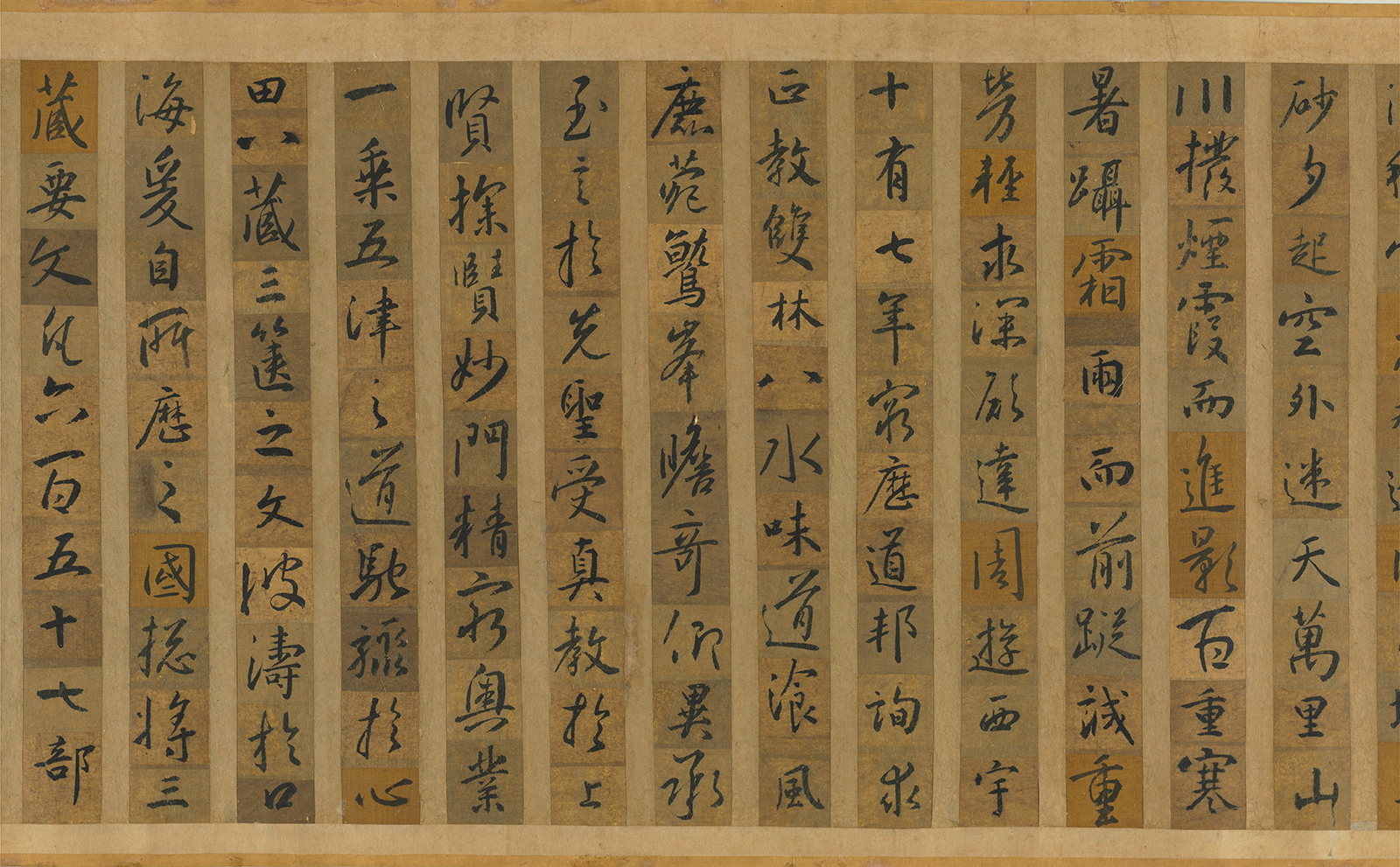

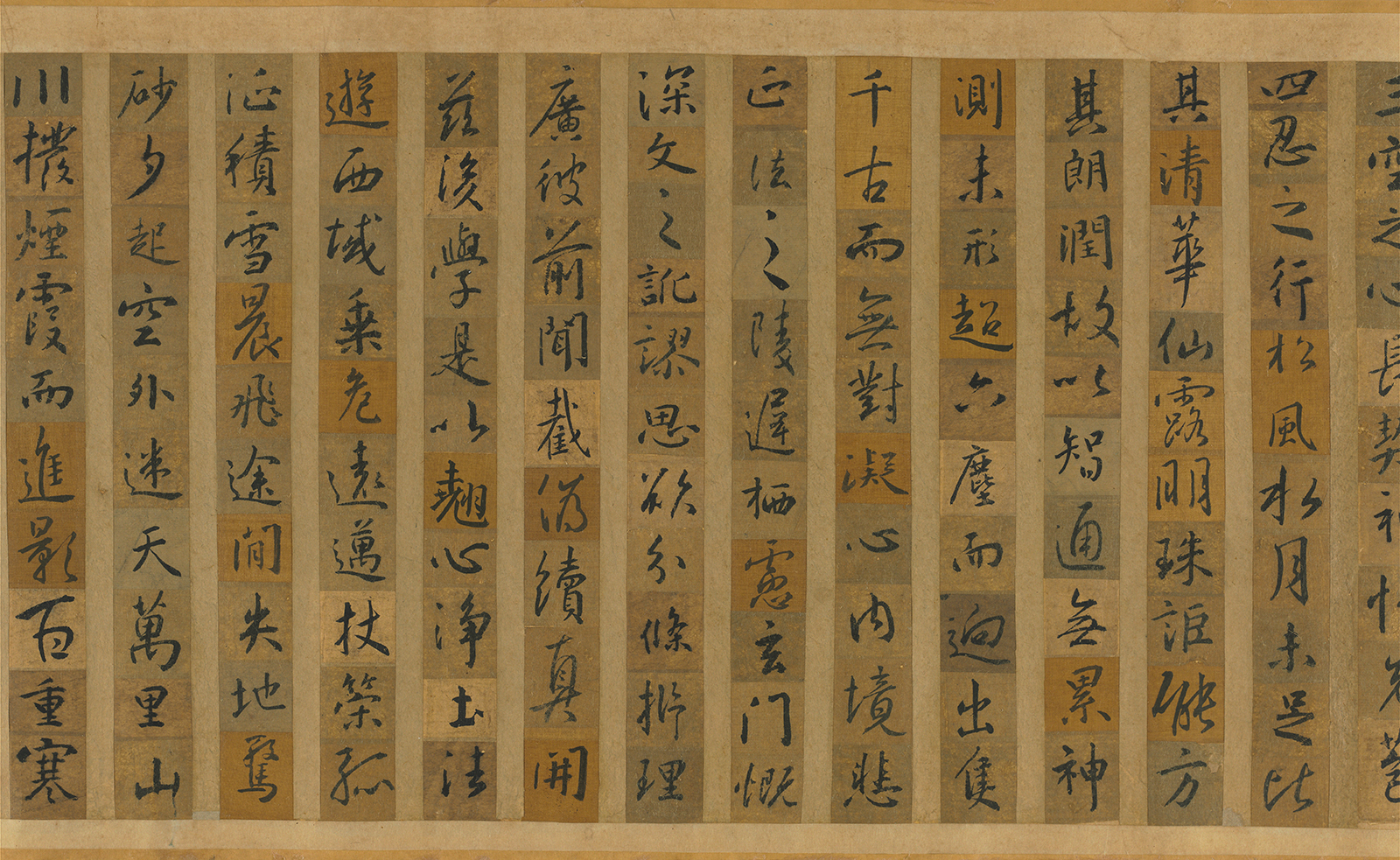

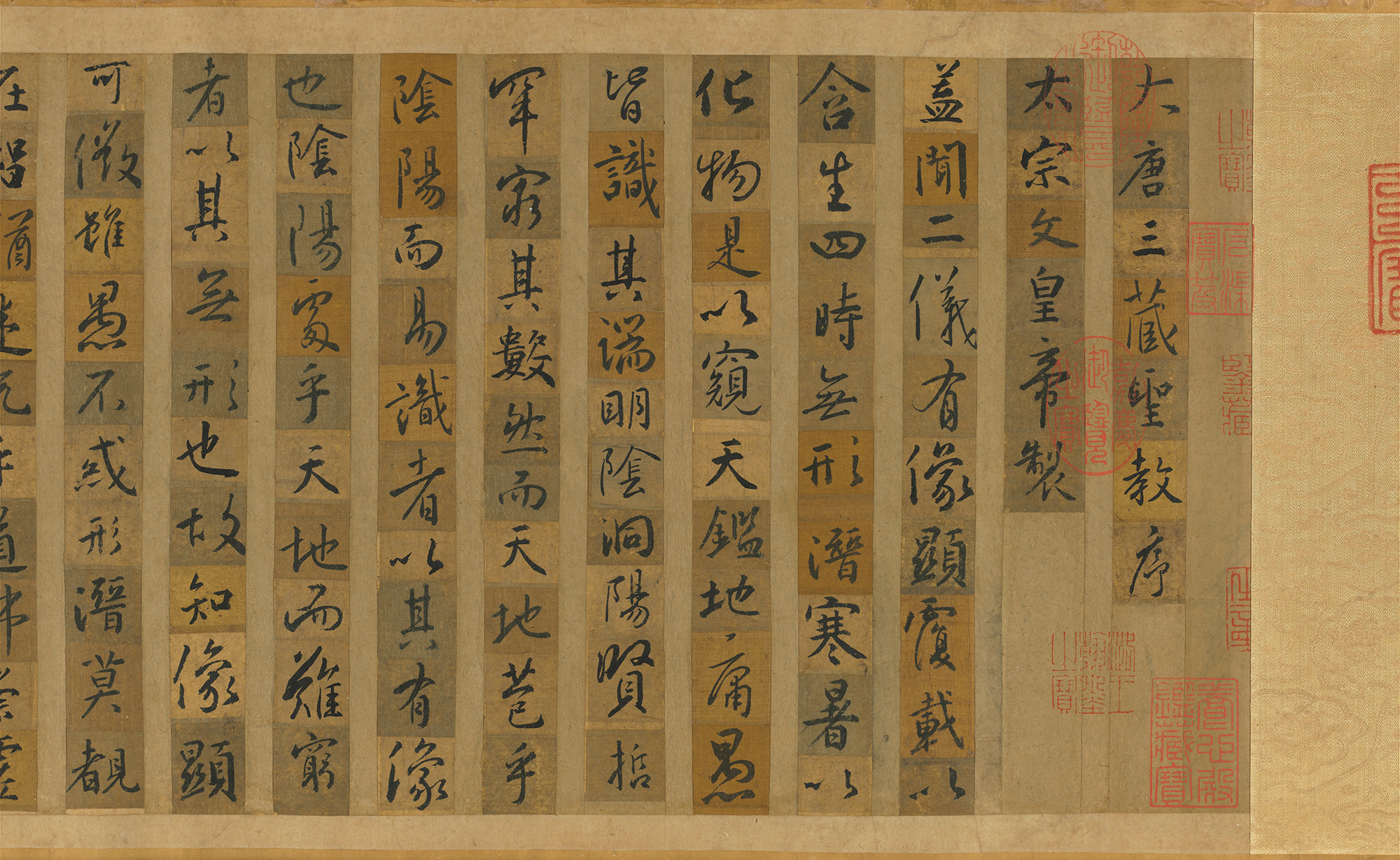

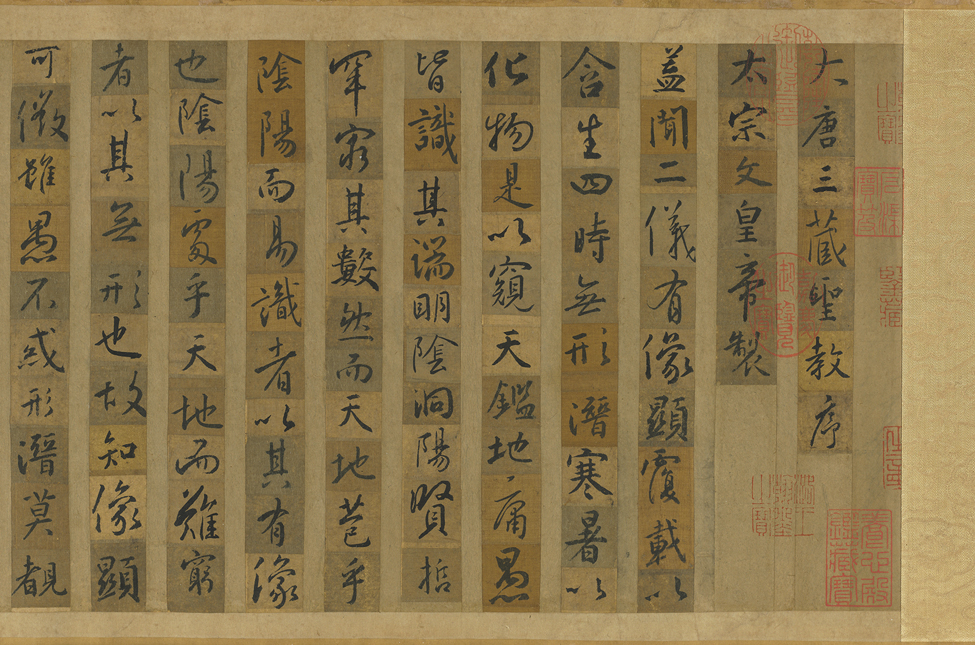

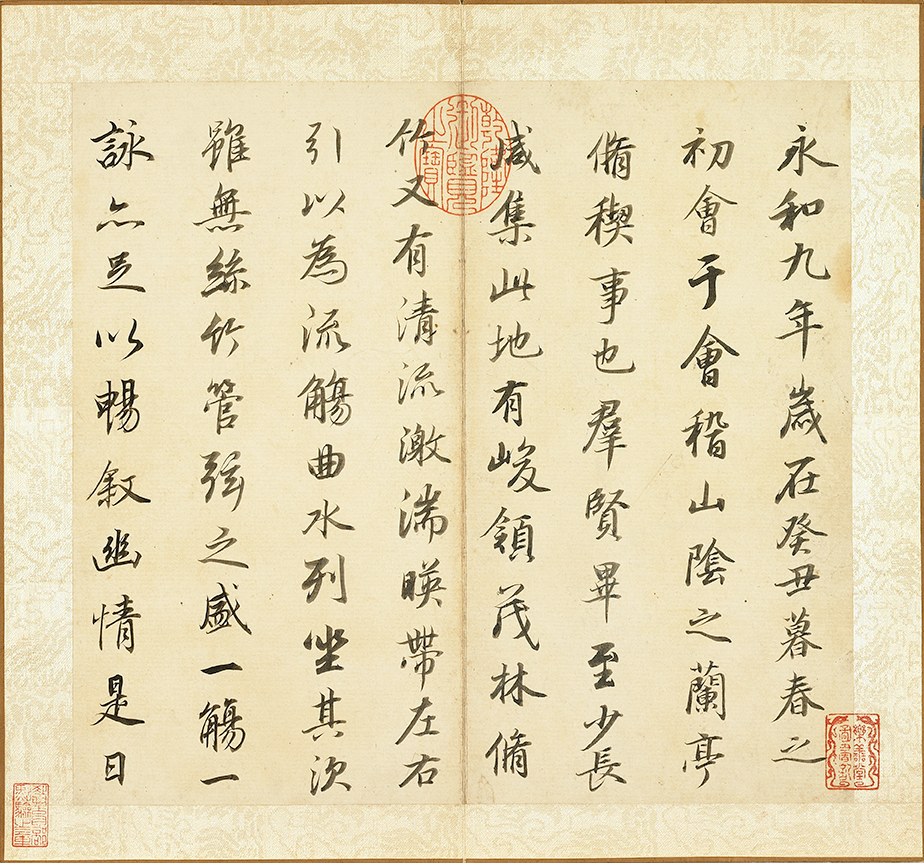

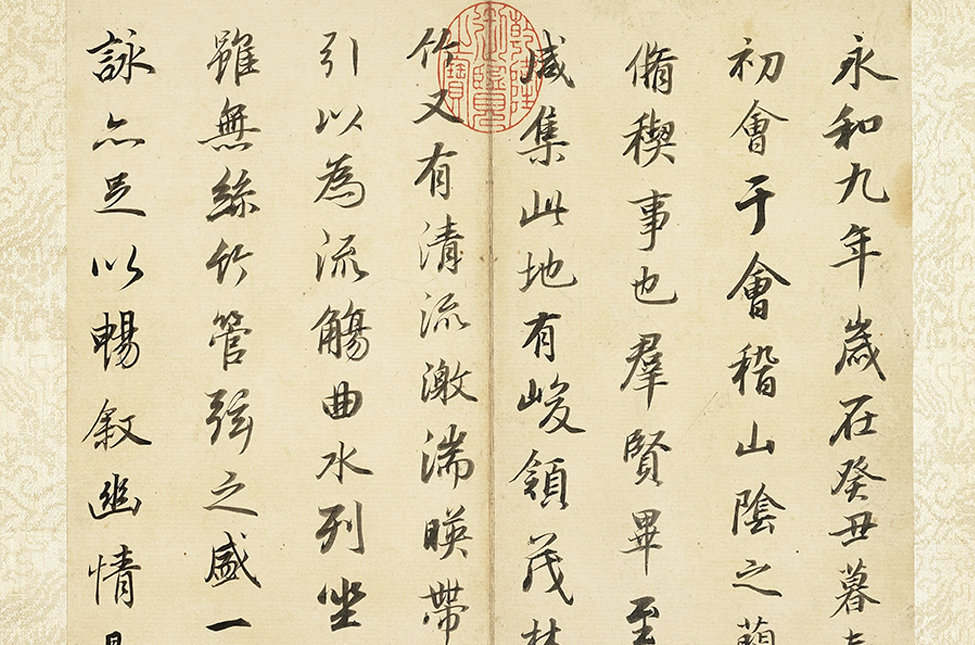

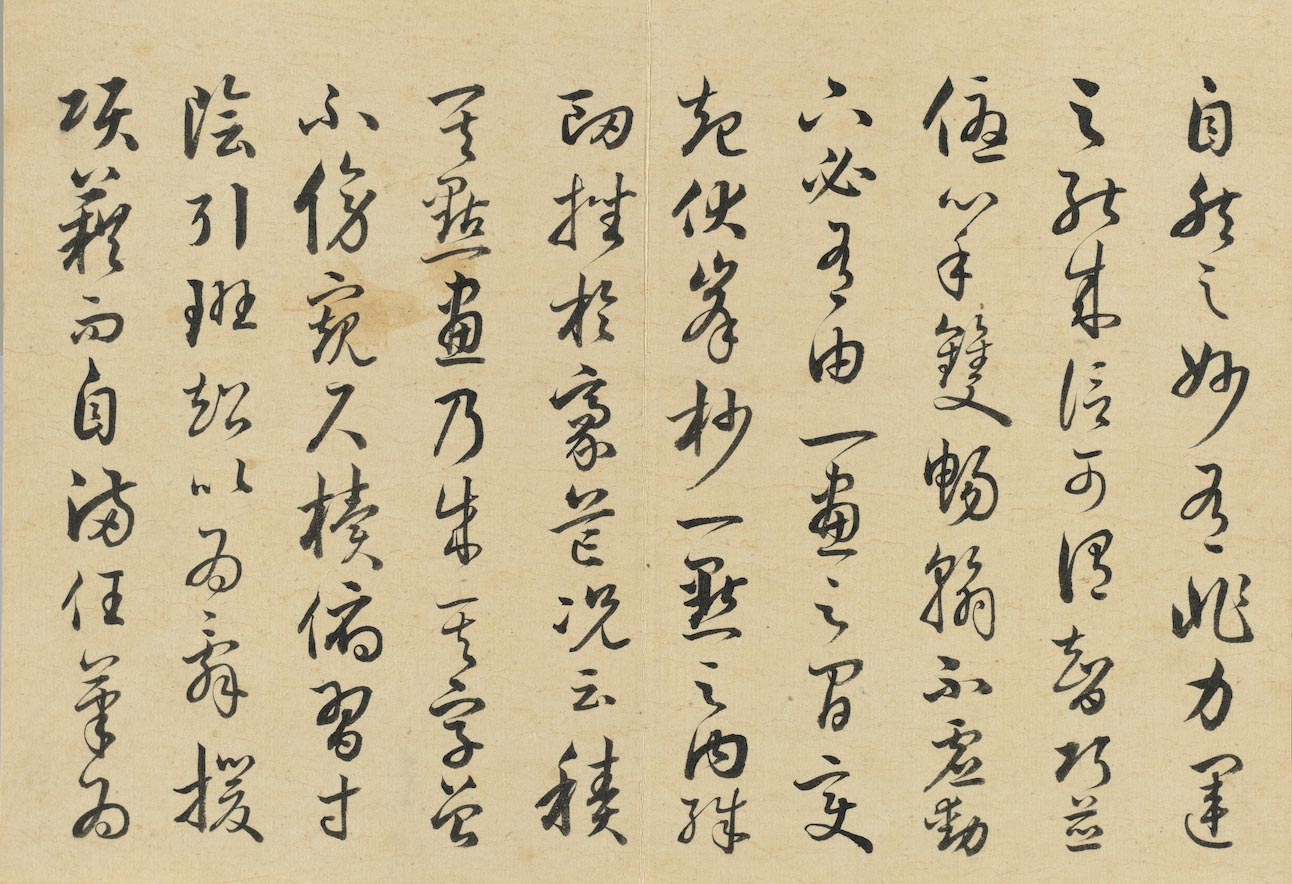

Preface to the Collected Sagely Teachings

- Huai Ren, Tang dynasty

This piece is comprised of Huai Ren’s copies of Wang Xizhi’s calligraphy, written when he had the originals before him. The scribe first wrote the calligraphy on paper and silk of different colors, before affixing it piece-by-piece to a decorative backing in the form of a handscroll. This is a highly original way of highlighting that this work is a “jizi” or “composite of characters.” Composites are made when a piece of writing (in this case, an essay by the second Tang dynasty emperor, Taizong) is transcribed by copying the requisite characters from disparate pieces of a master’s calligraphy.

Huai Ren made “Preface to the Collected Sagely Teachings” under order of Tang dynasty emperor Taizong (7th century) by copying characters from various pieces of running script calligraphy written by Wang Xizhi (303-361). It was engraved onto a stele in the third year of the Xianheng reign period (672), becoming a renowned calligraphic classic.

-

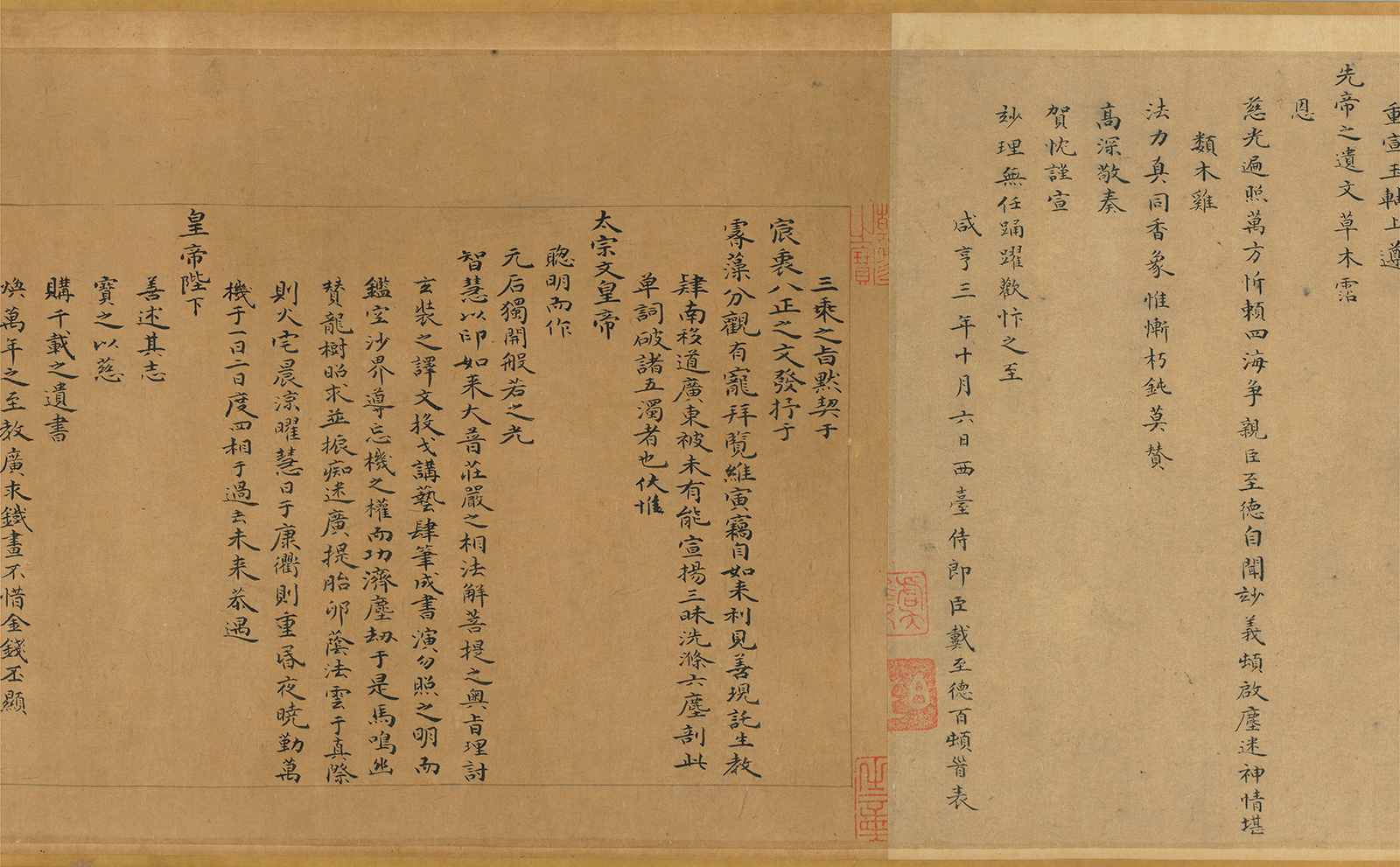

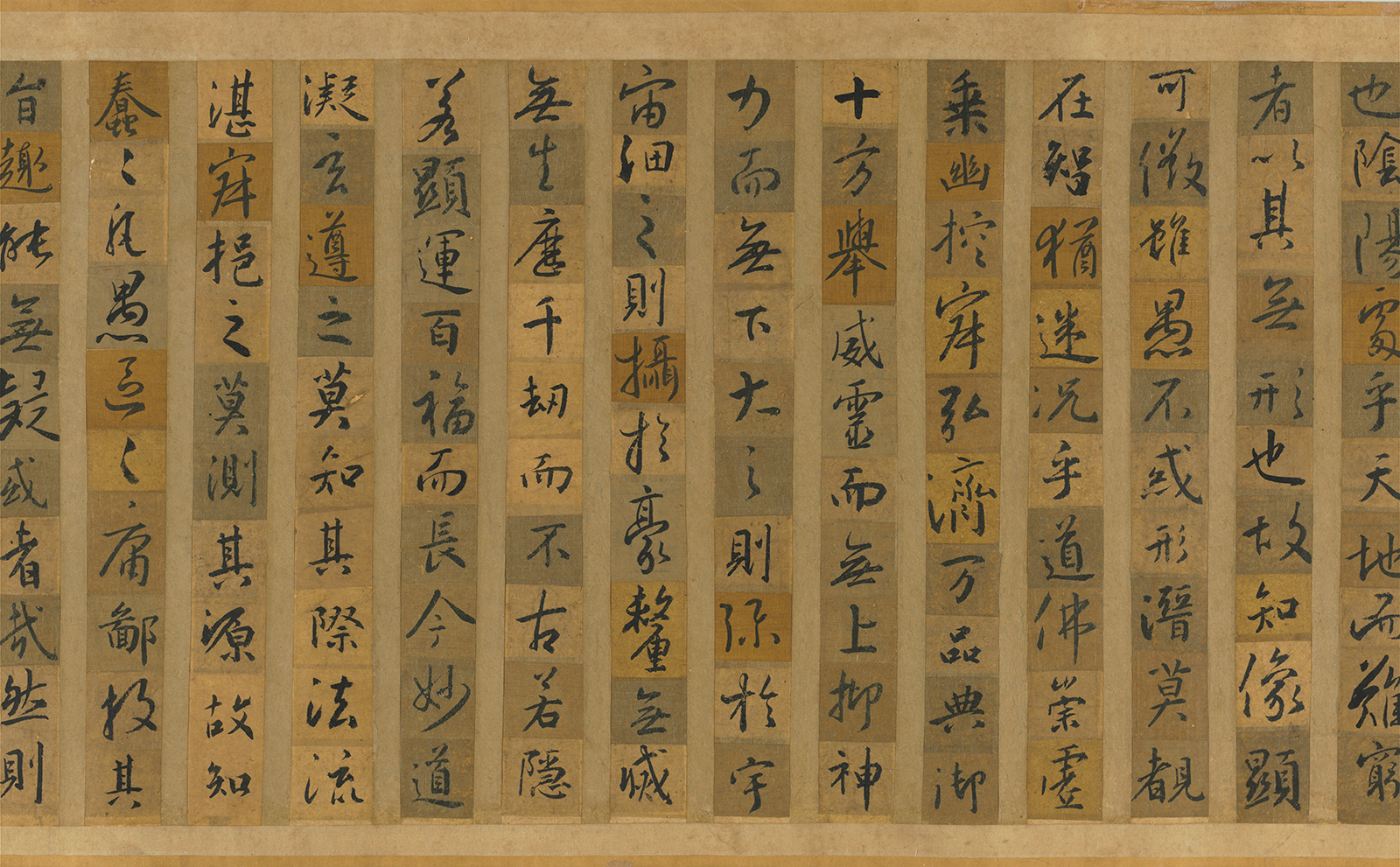

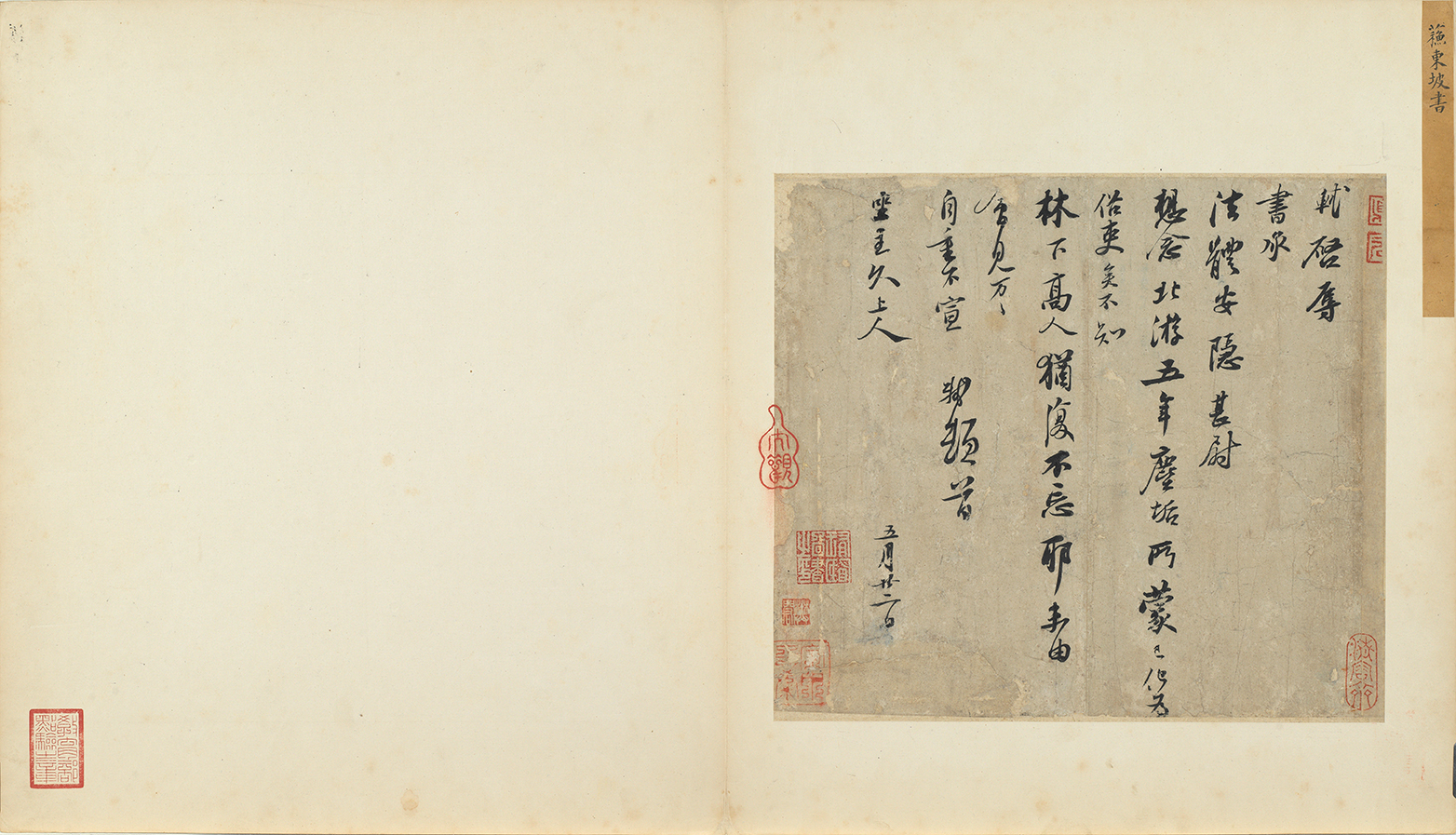

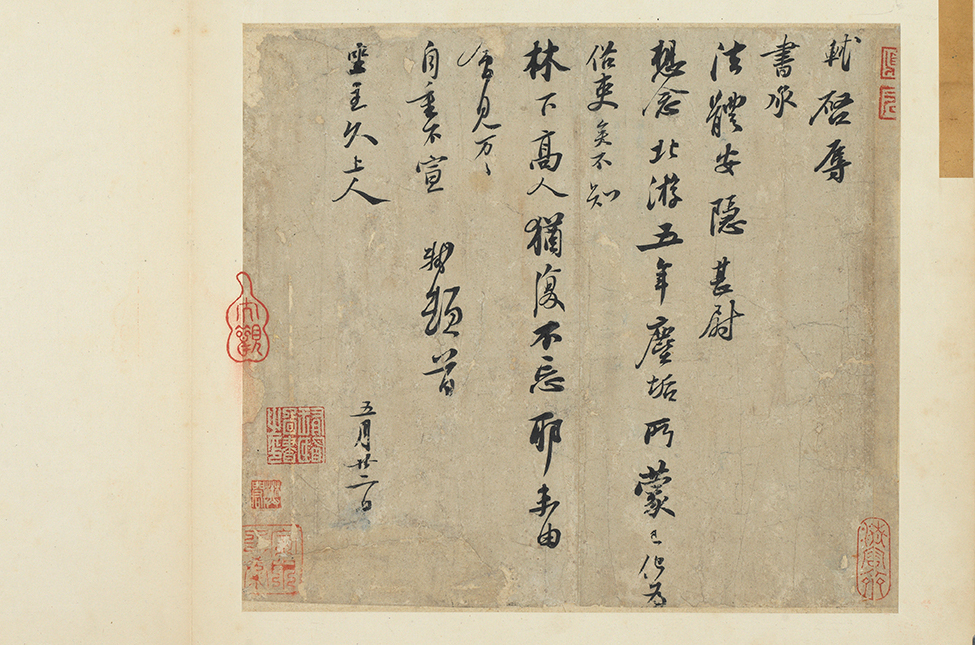

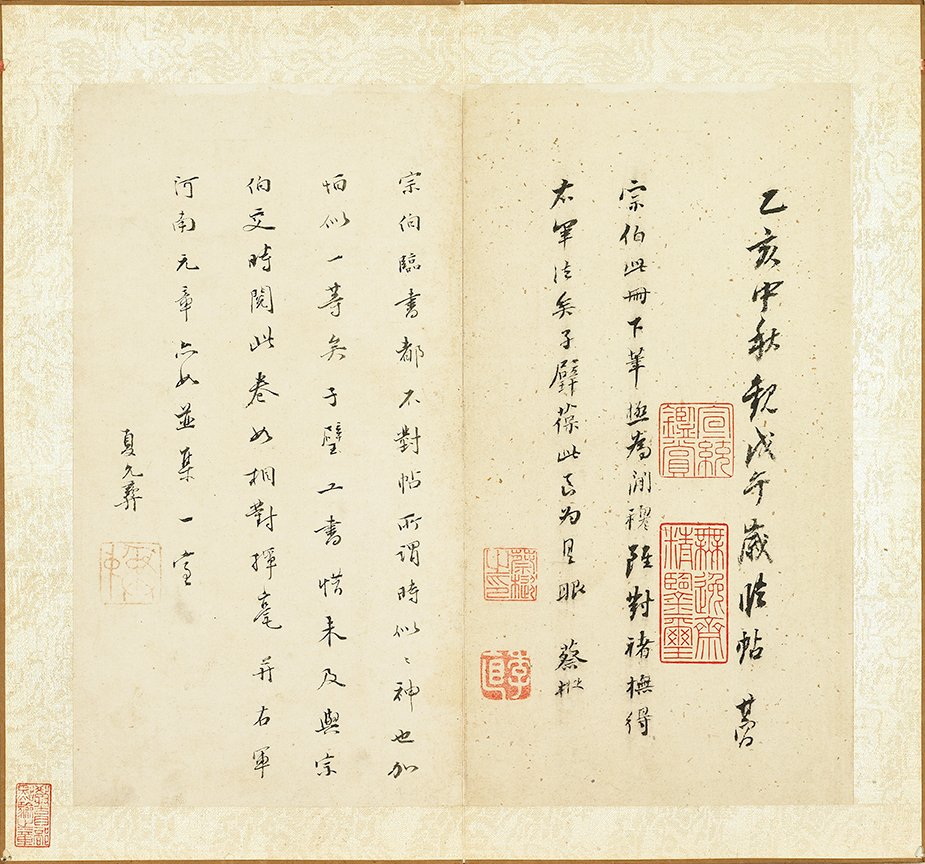

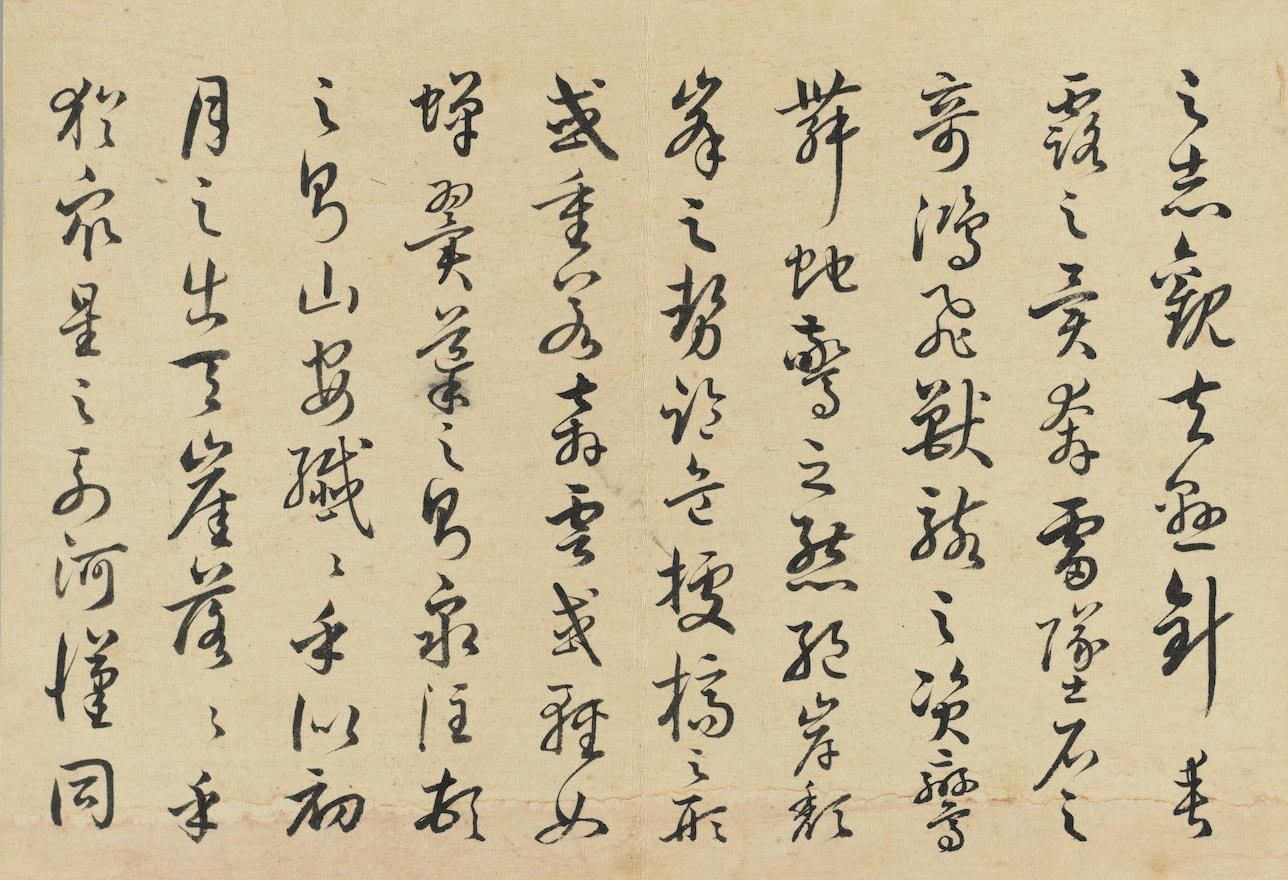

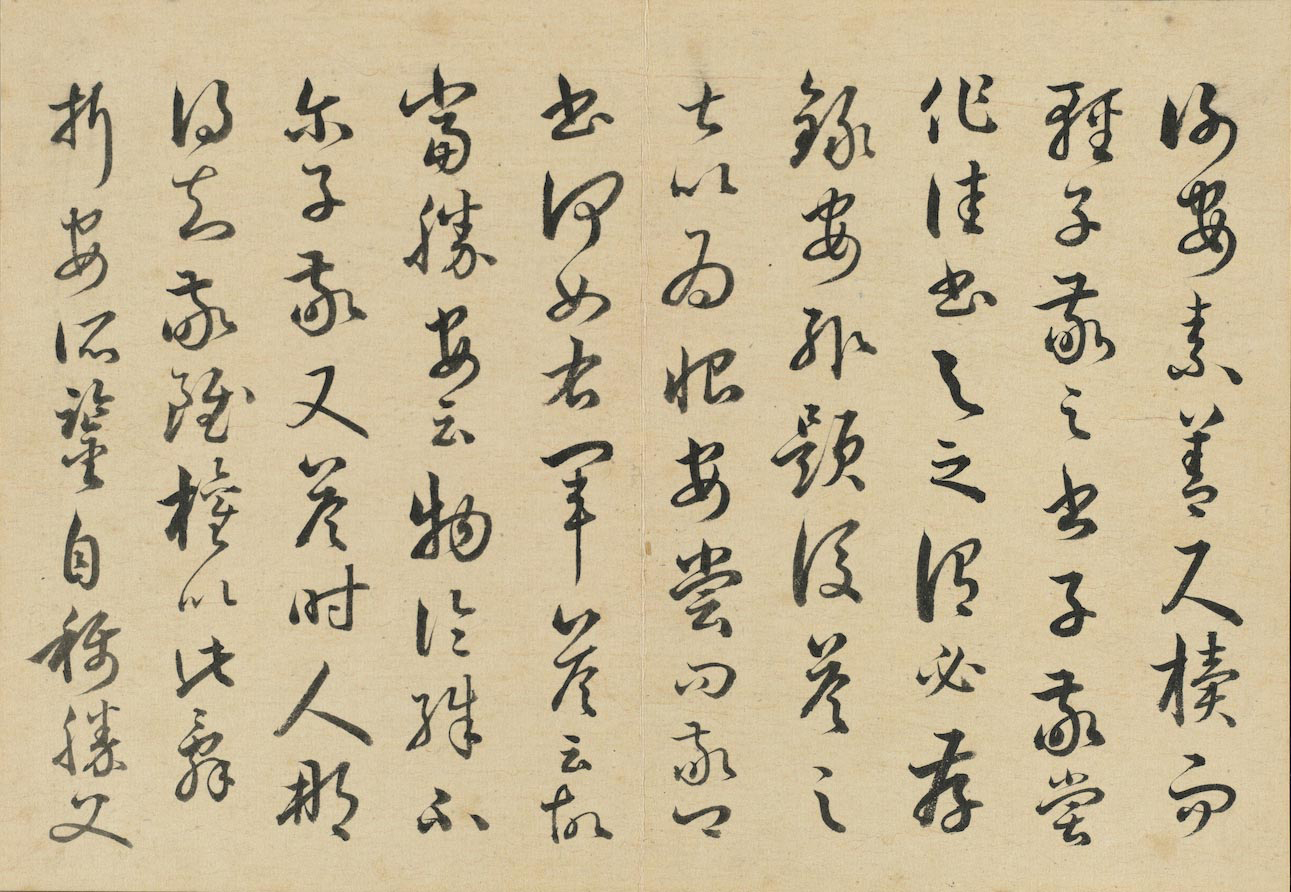

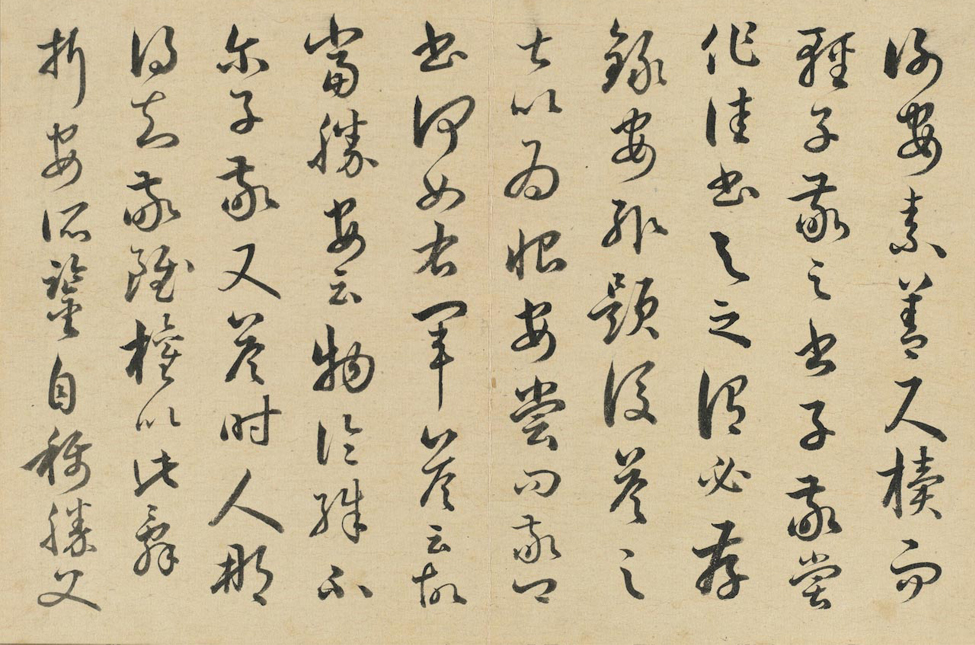

Letter

- Su Shi, Song dynasty

Su Shi (1037-1101), whose style name was Zizhan, was a native of Meishan in Sichuan province. This letter was addressed to Kejiu of Xiangfu Buddhist Monastery, a renowned monk-poet contemporary of Su’s.

Research points to Su Shi having written this letter in the second year of the Yuanfeng reign period (1079). At the time of writing, Su was serving as the magistrate of Huzhou. He had already left Hangzhou to go northwards five years’ prior, leading him to write the line “I’ve traveled in the north for five years.” In the eighth lunar month of the same year, the verdict of the “Crow Terrace Poetry Case” (in which he was accused of slandering the emperor in his poems) saw Su thrown in jail. In this letter, the function of the very tip of the brush is highly emphasized, revealing the influence of Su Shi’s studies of the calligraphy in the “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion” in his youth.

-

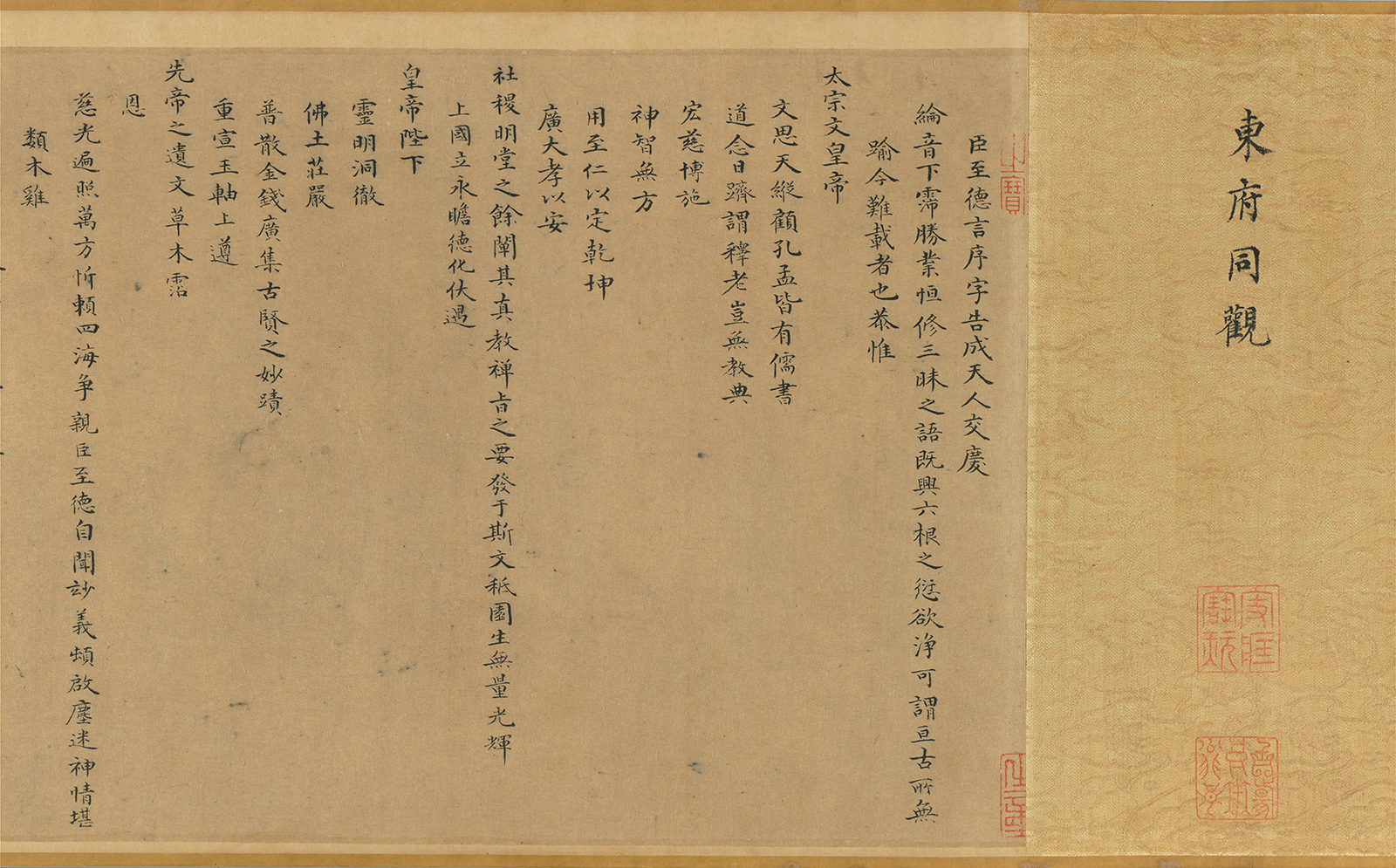

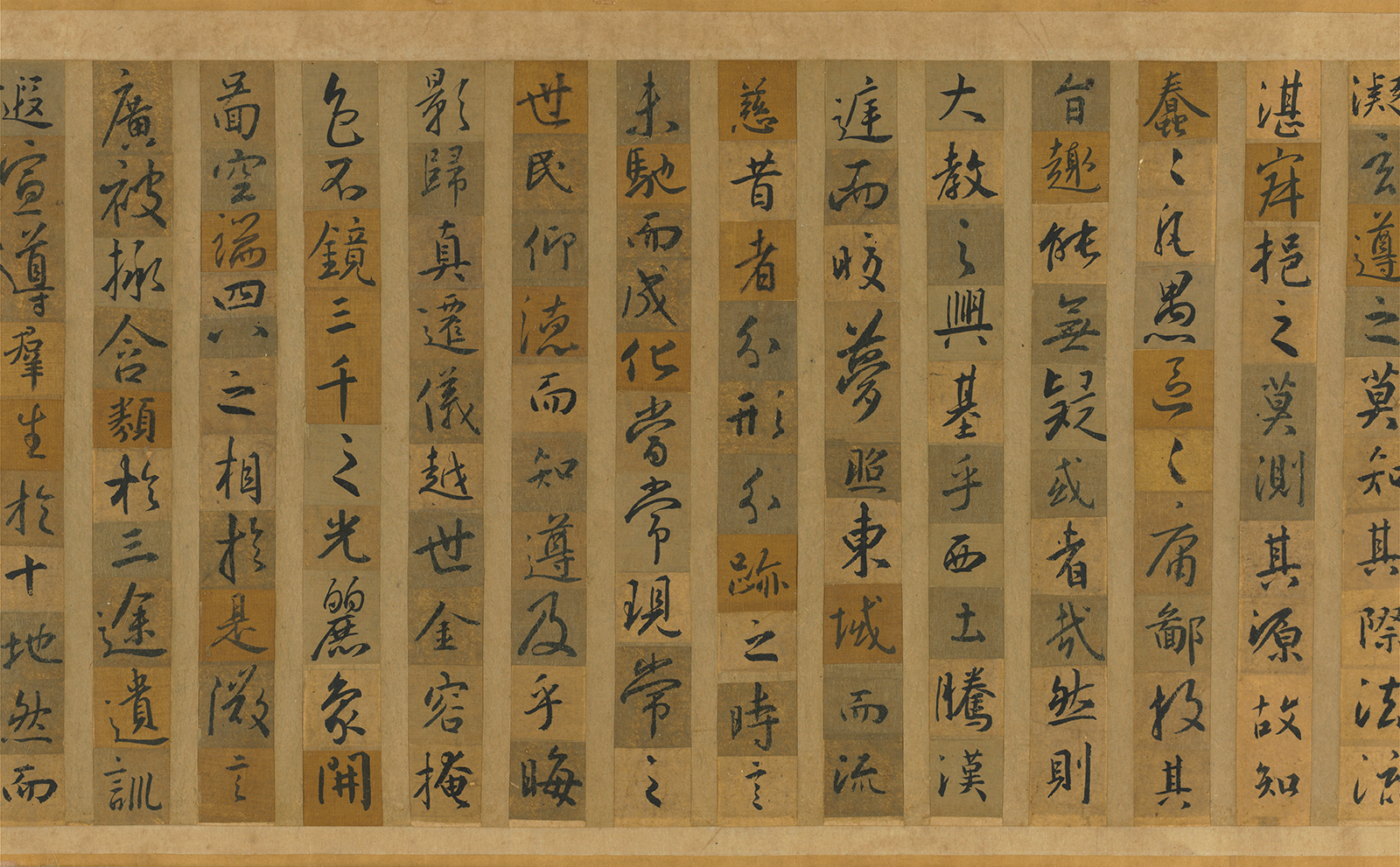

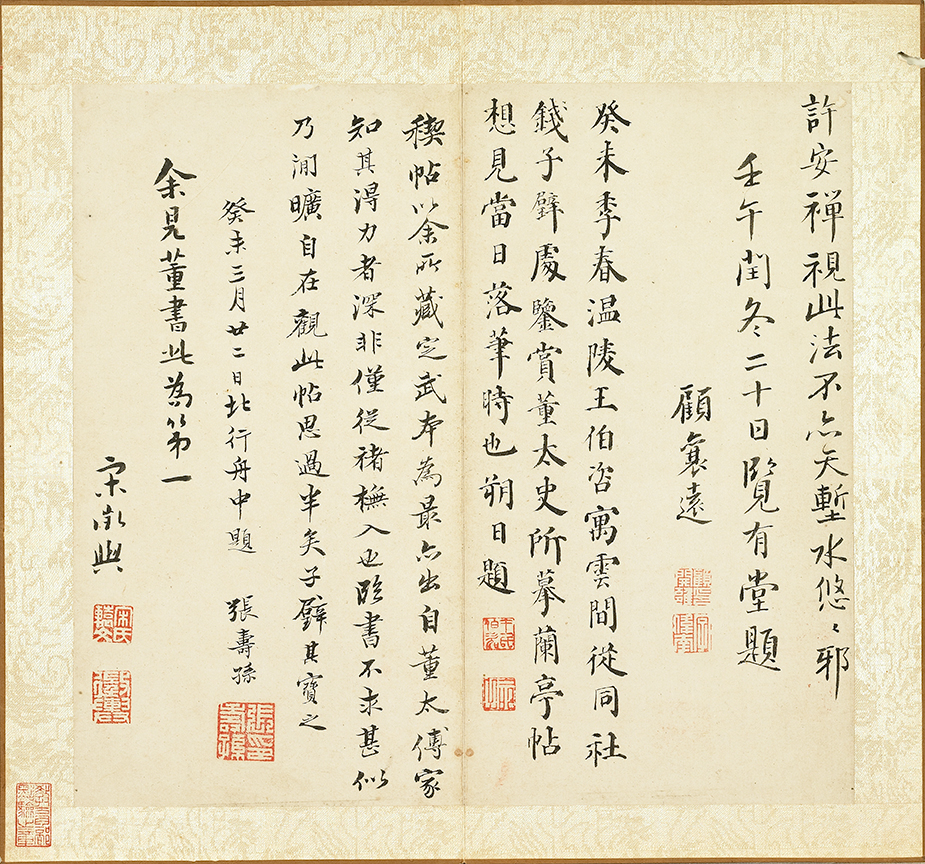

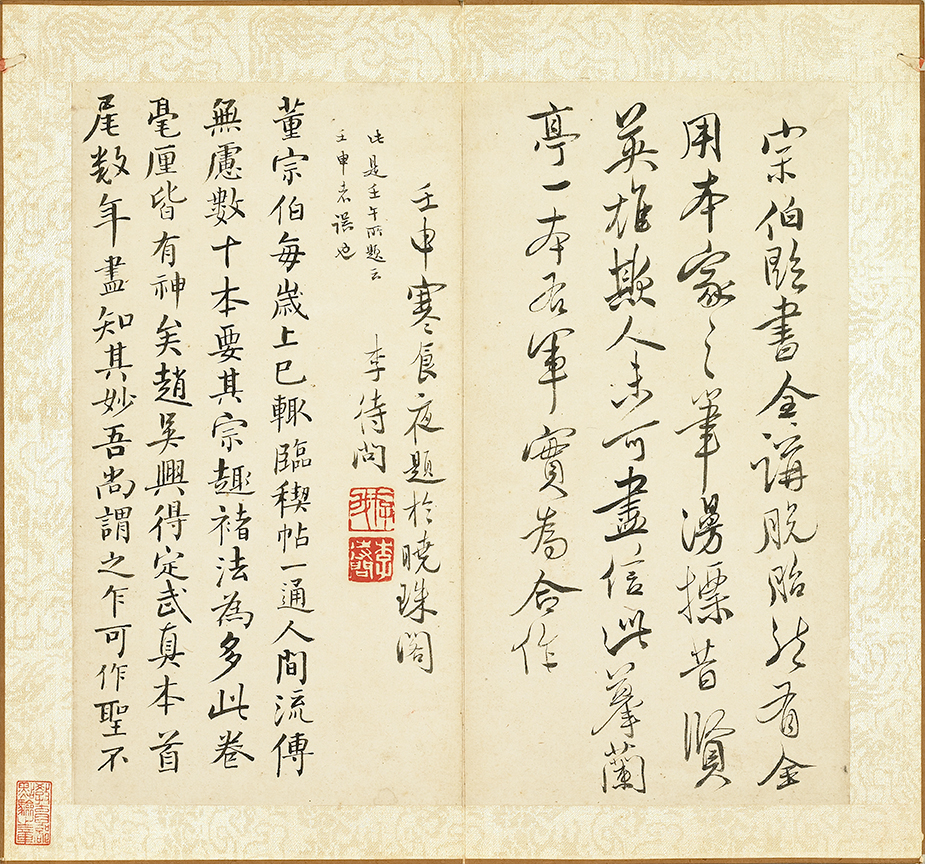

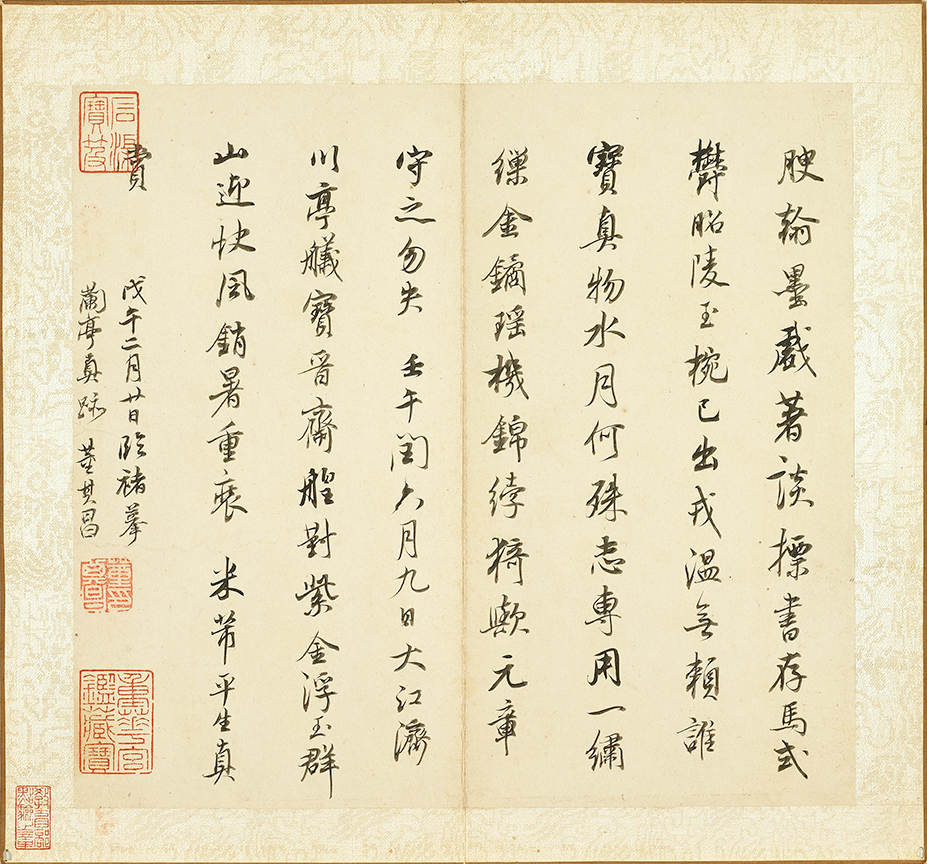

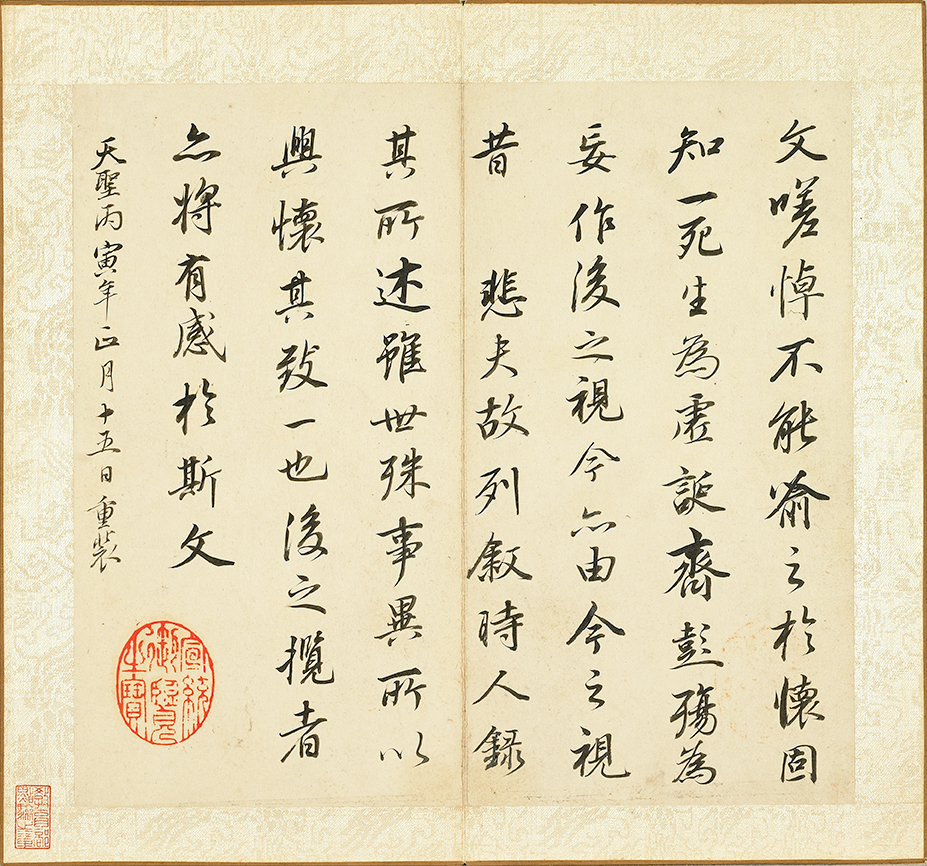

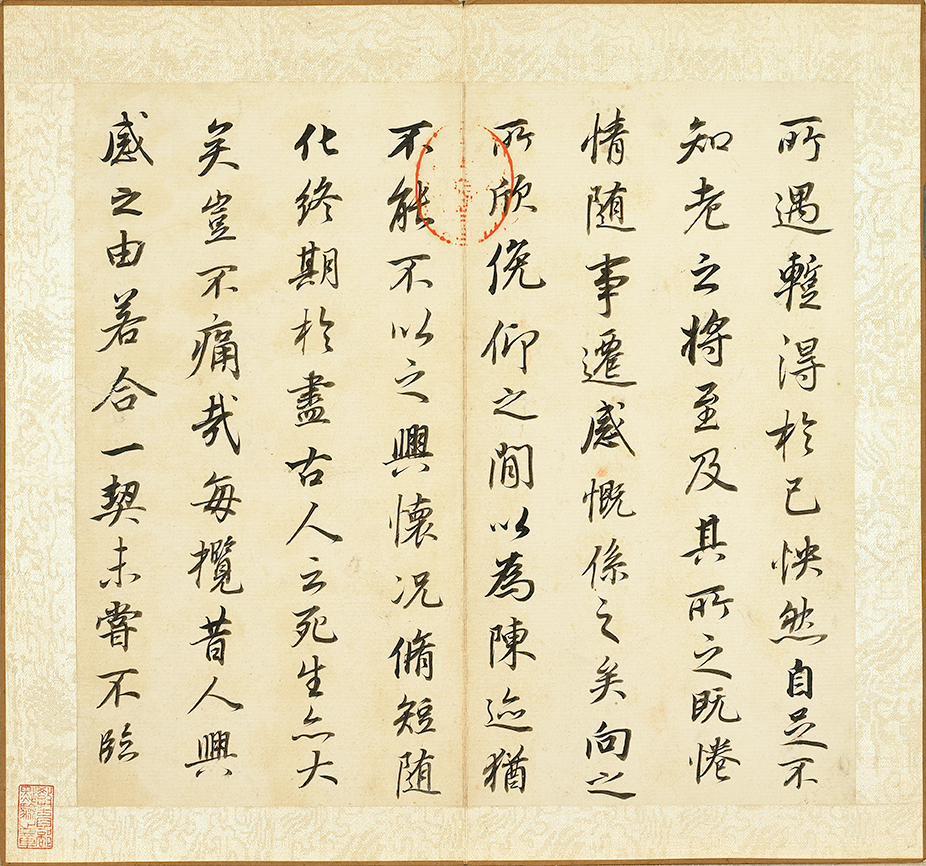

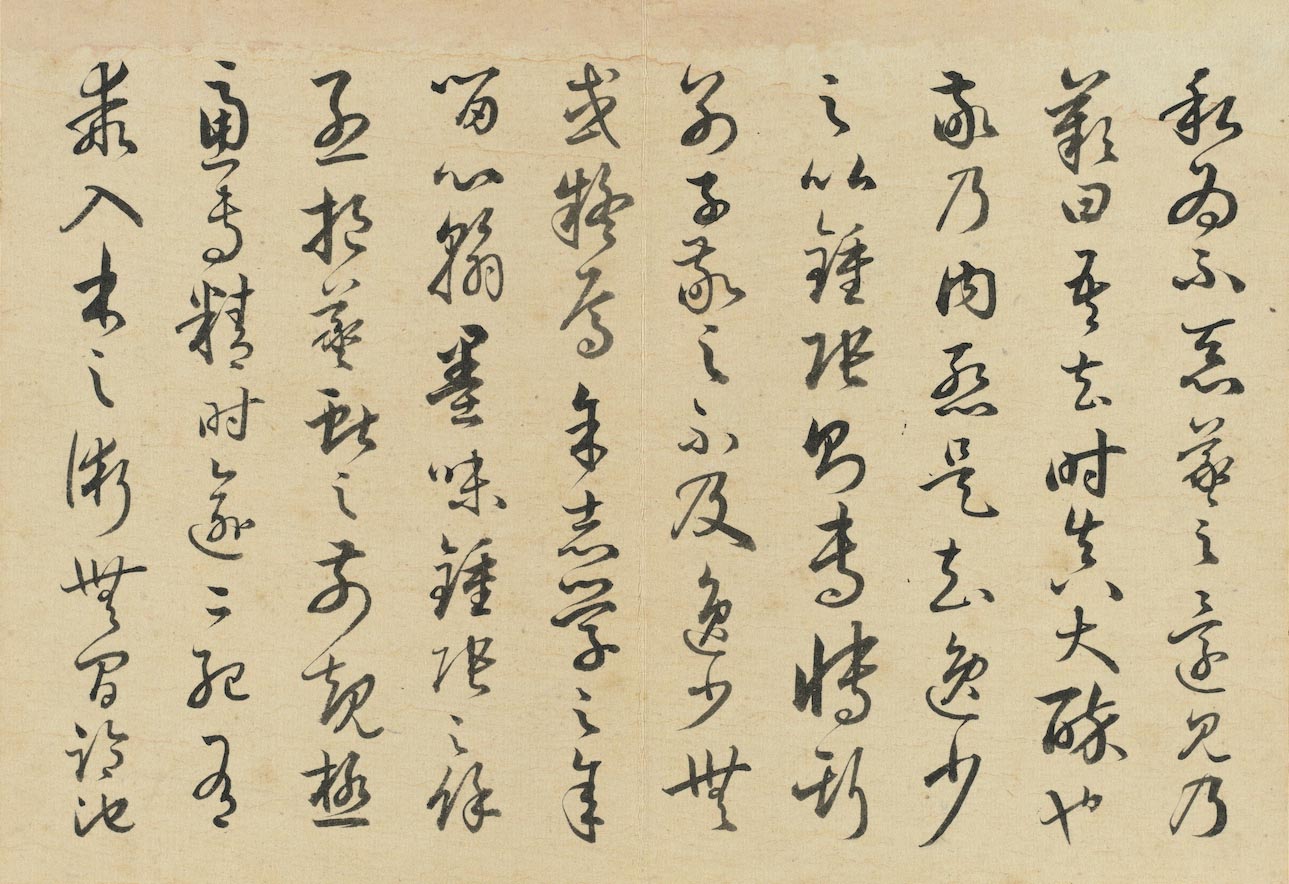

Copy of Chu Suiliang’s “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion”

- Dong Qichang, Ming dynasty

Dong Qichang (1555-1636), who had the style name Xuanzai and the sobriquet Sibai, was from Huating in Jiangsu province. In the seventeenth year of the Wanli reign period (1589), he obtained the rank of presented scholar in the imperial examinations. He was posthumously conferred the name Wenmin.

Dong’s calligraphy was strongly influenced by the “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion,” and it is said that each year, at the time of the ceremony of purification in late spring, he would transcribe a copy of the entire preface—a proclivity that makes clear his respect and fondness for the calligraphic sages of old. The writing in this album was created with fluid and dexterous brushwork, with character structures that adhere closely to the original from which they were copied. Dong adeptly satisfied all of the requirements for copying calligraphy with this piece, which Ming dynasty literatus Song Zhengyu (1618-1667) praised as Dong Qichang’s finest work.

-

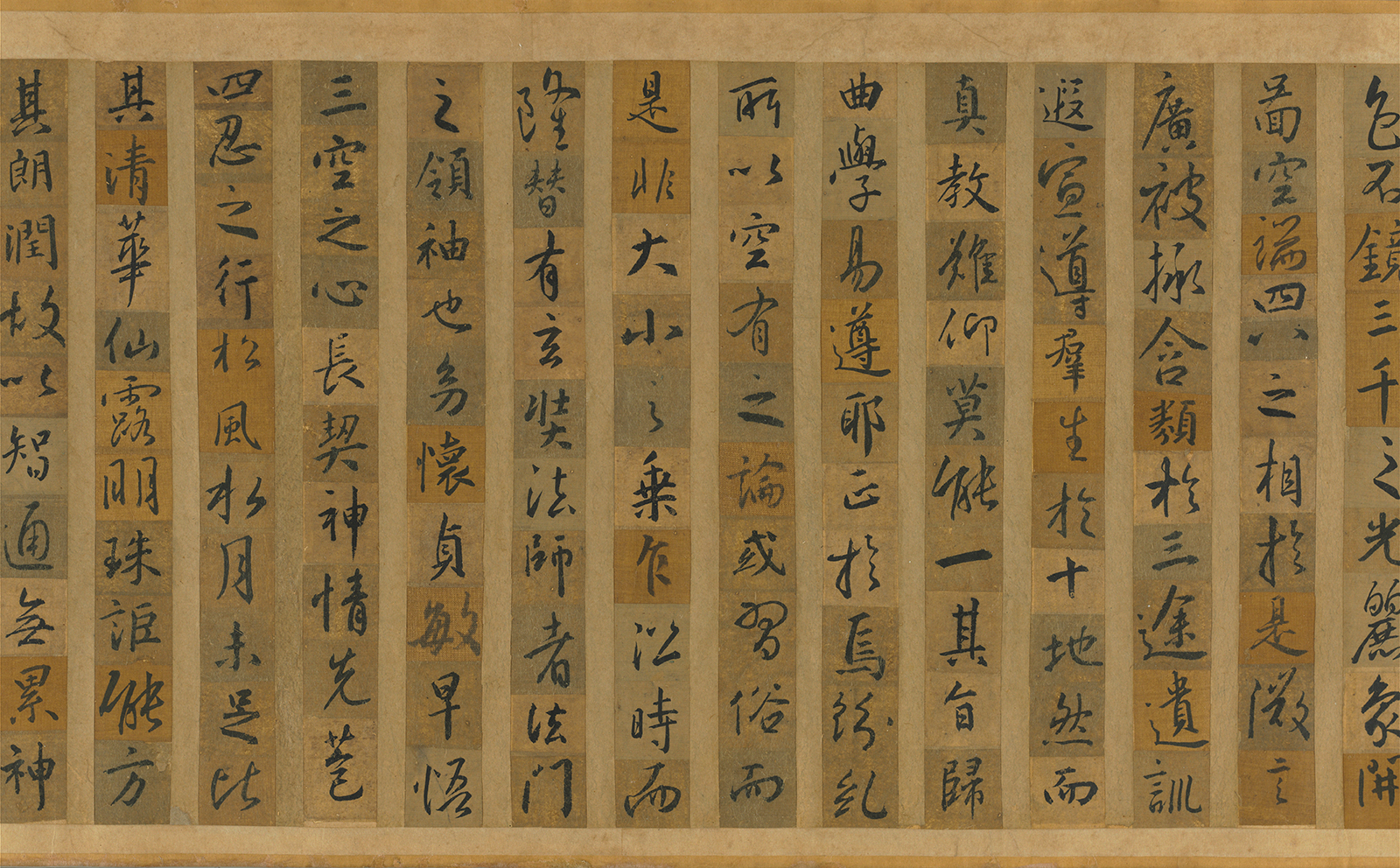

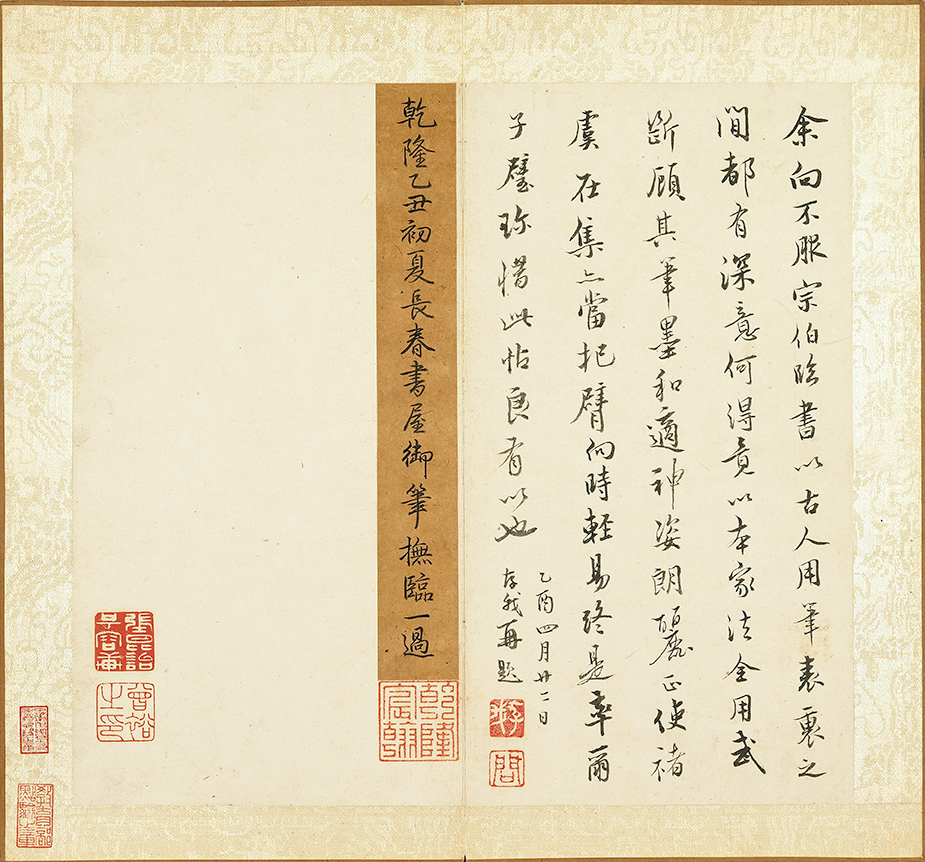

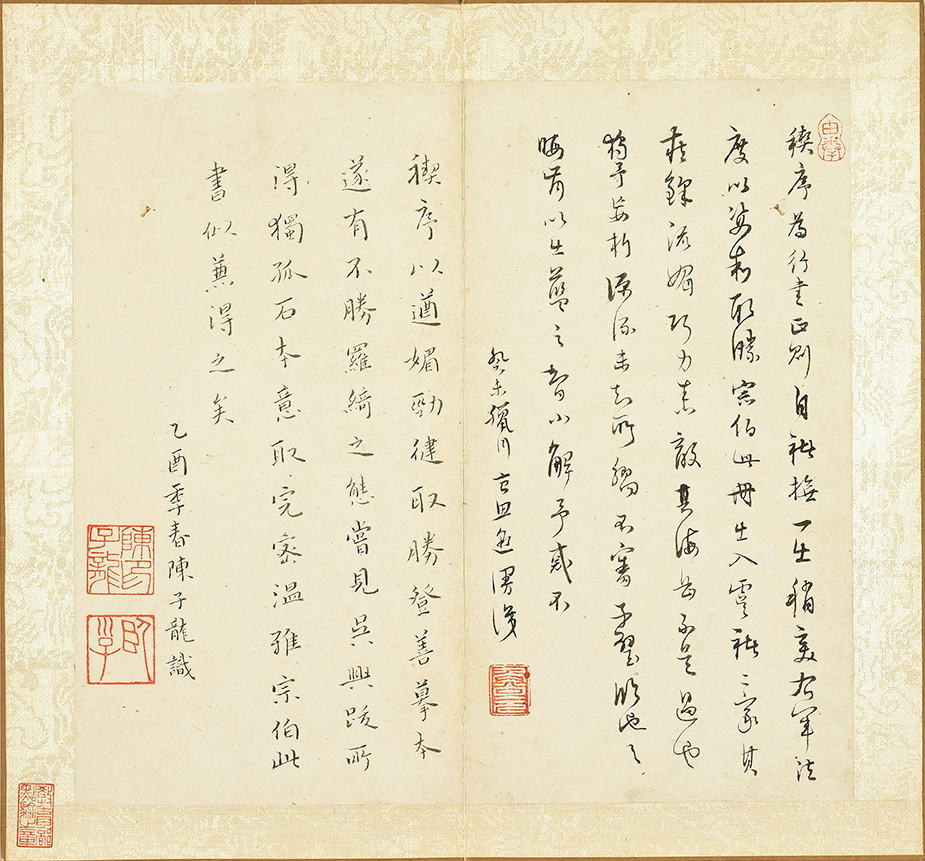

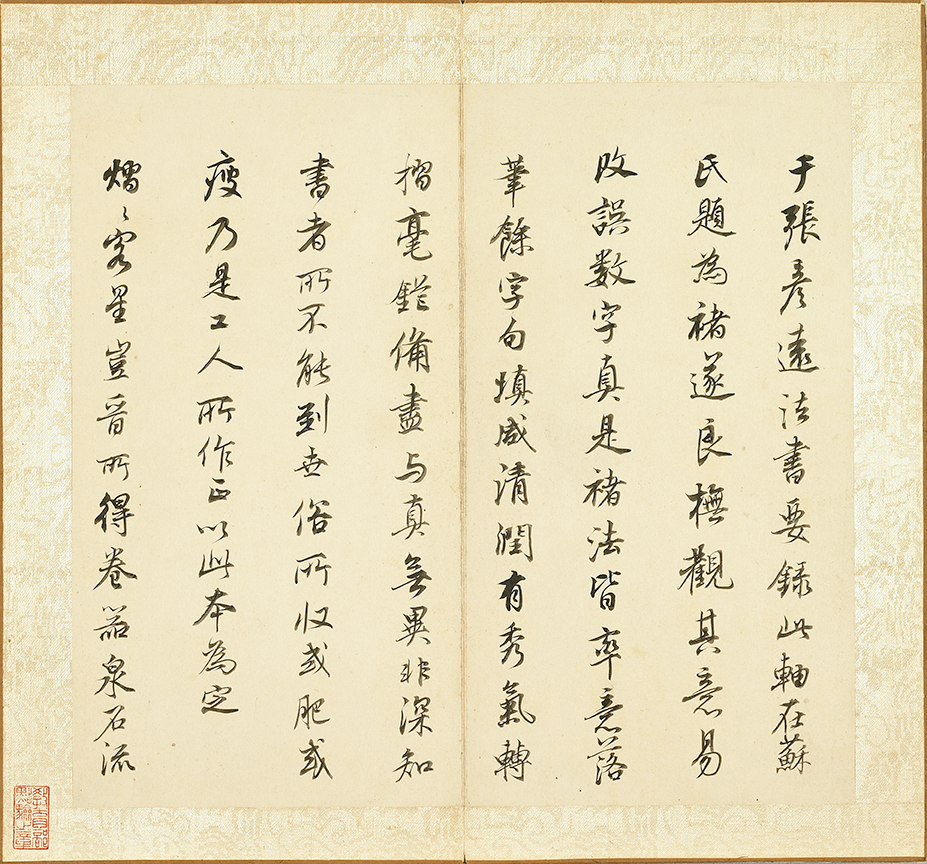

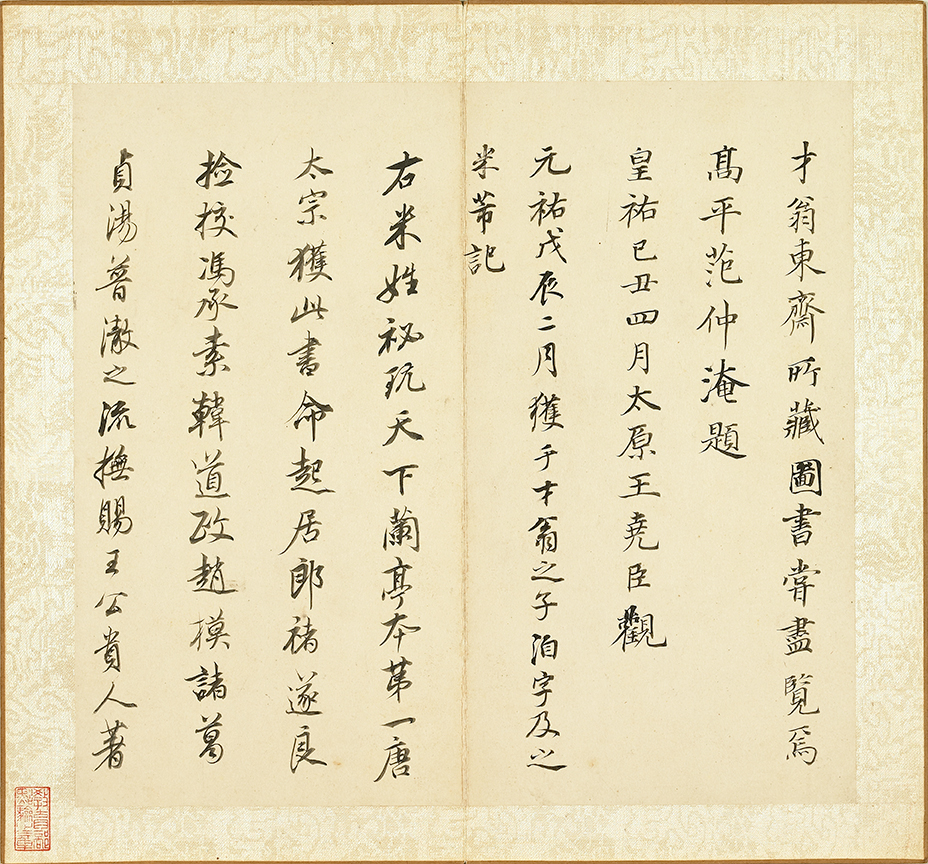

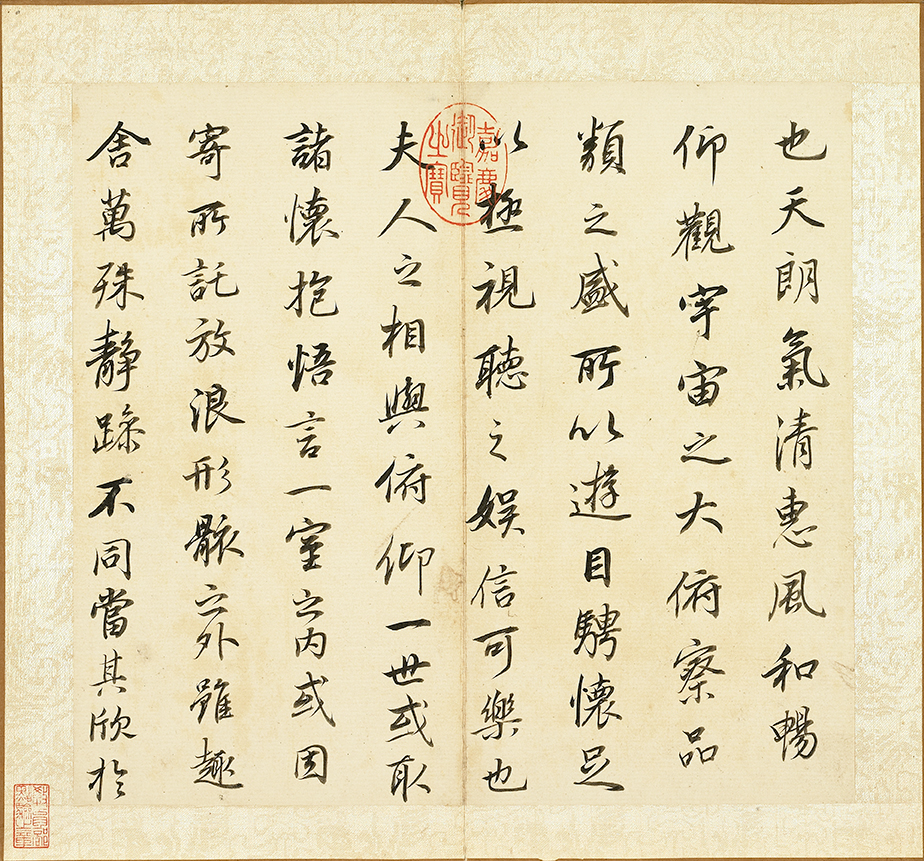

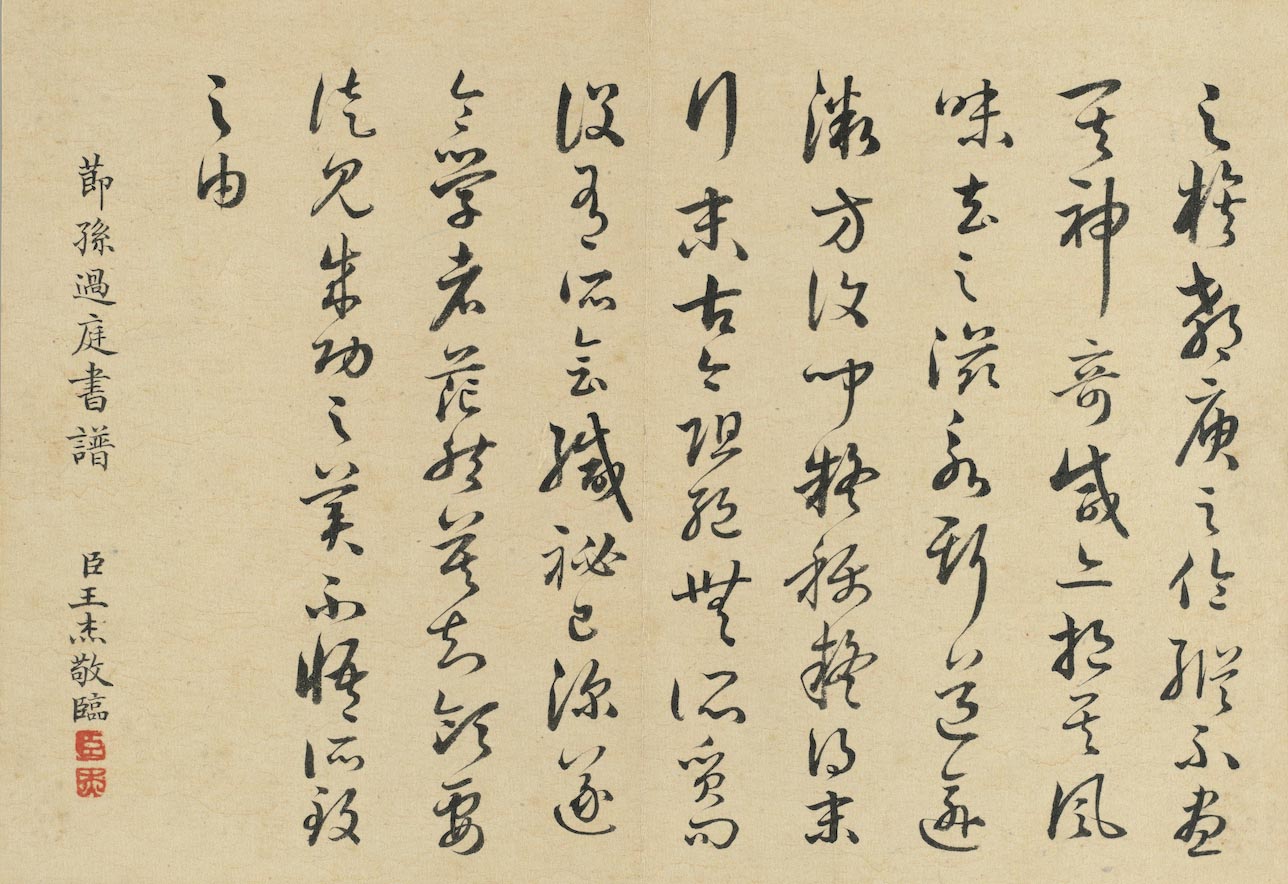

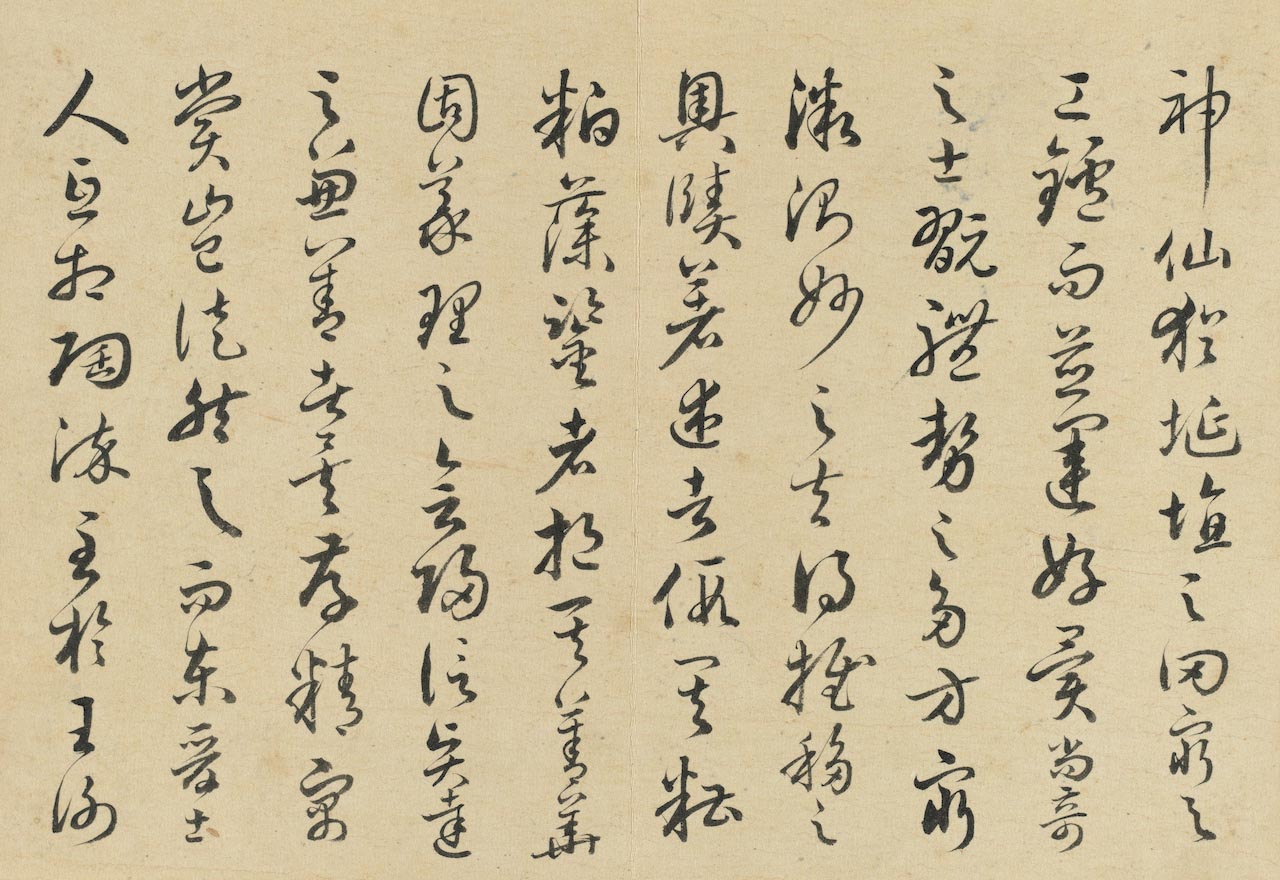

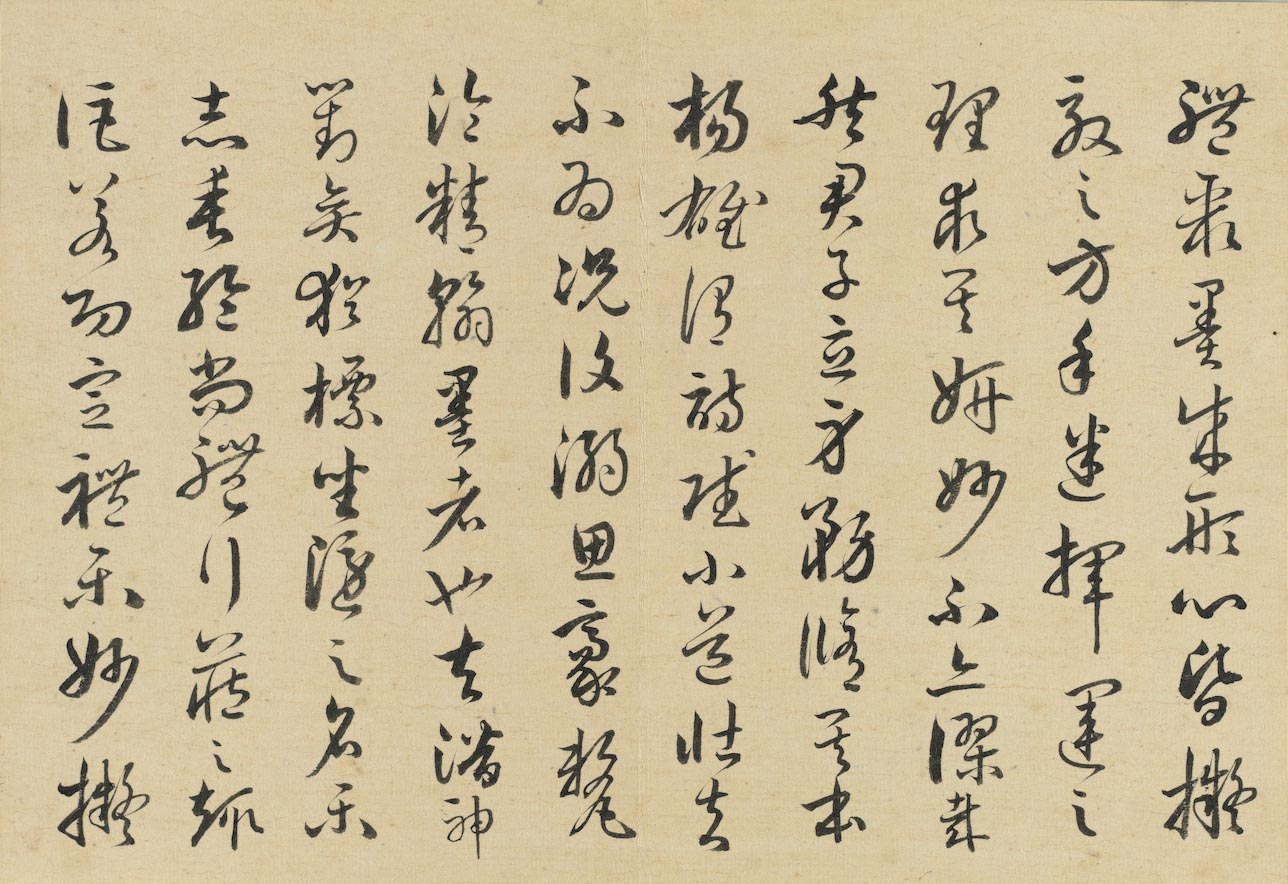

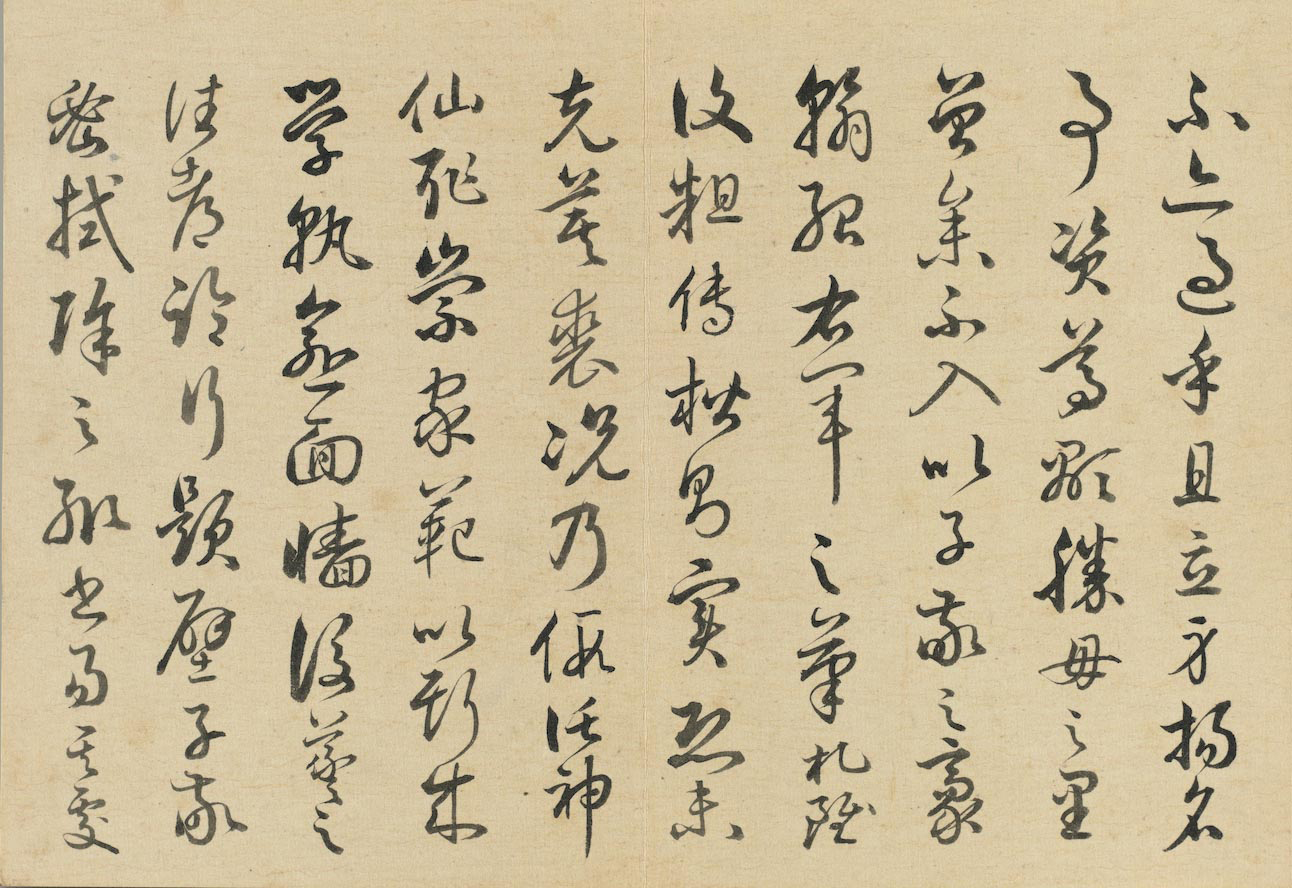

Copy of the “Essay on Calligraphy”

- Wang Jie, Qing dynasty

Wang Jie (1725-1805), whose style name as Weiren, was from Hancheng county in Shaanxi province. During the twenty-sixth year of Qianlong’s reign (1761) he placed first in the imperial examinations and was made grand secretary of the secretariat. He was celebrated as “the most famous minister from Shaanxi.”

This piece is a study of Tang dynasty calligrapher Sun Guoting’s “Essay on Calligraphy.” Although its layout differs somewhat from the original, in terms of its strokes and dots as well as the characters’ overall structures it is a faithful replica, suggesting that Wang wrote this piece with the original before him. Wang’s brushwork and character structures tend to be more cautious and conservative than Sun’s, but he was still profoundly capable of emulating the techniques of the great Tang dynasty calligraphers, creating a composition with an abundance of spaciousness, delicacy, and meaning.

-

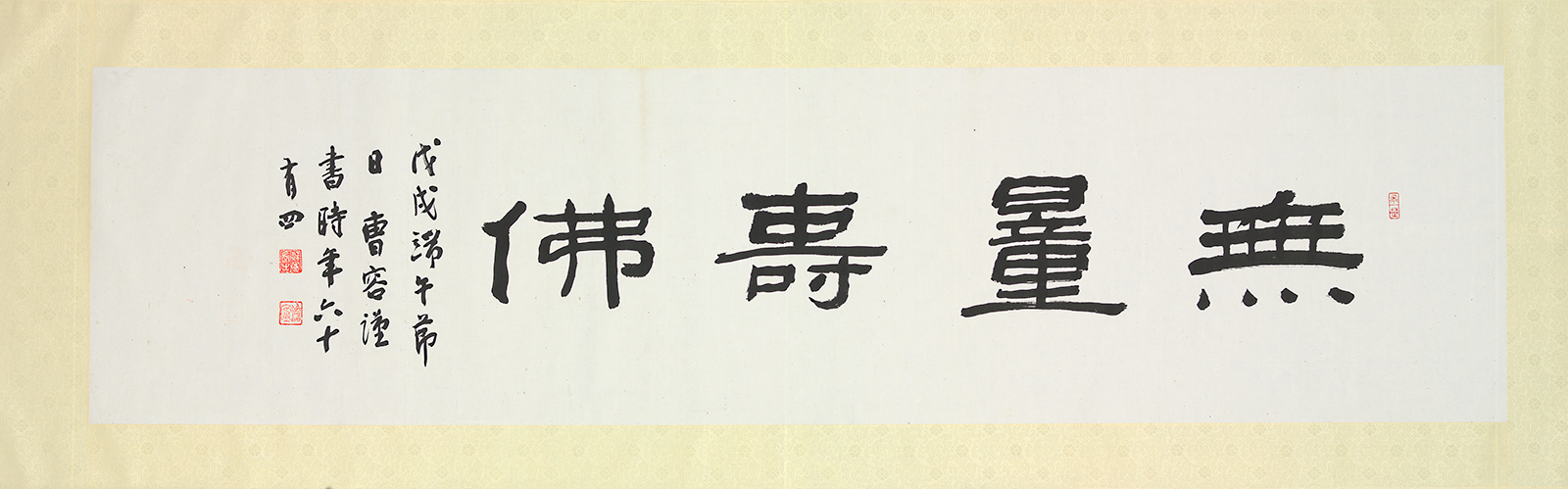

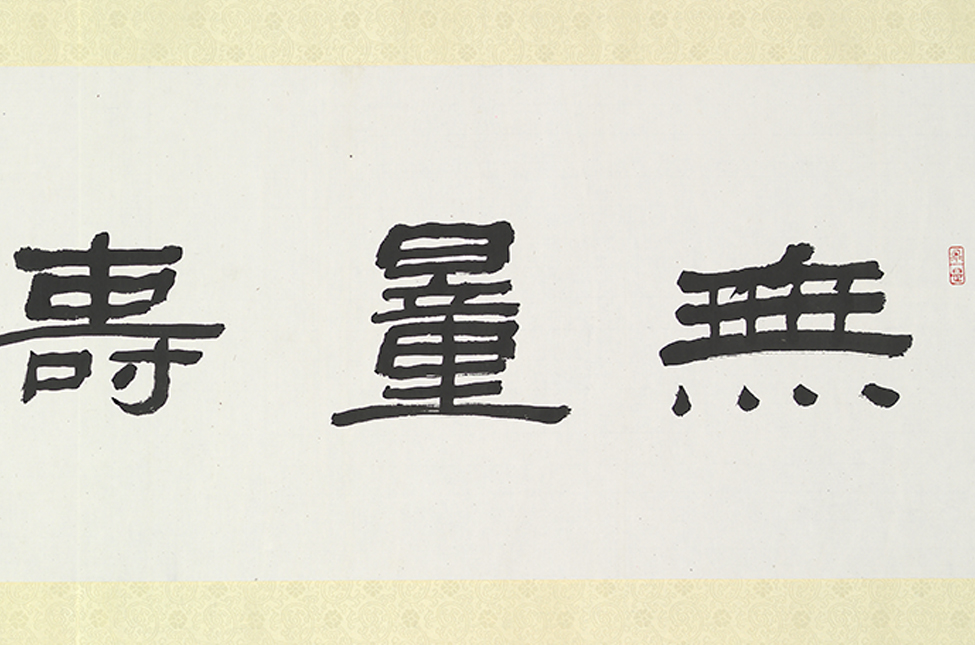

“Buddha of Boundless and Infinite Life” in Clerical Script

- Cao Rong, Republican era

Cao Rong (1895-1993), a native of Taipei, had the style name Qiupu. He founded the Danlu Calligraphy Society in the eighteenth year of the R.O.C. (1929), establishing its core ethos of “Calligraphy, Dao, and Chan.” He mentored countless outstanding students.

Cao’s clerical script (lishu) blends elements from Han dynasty clerical script with Lü Xicun’s (1784-1855) character structures and brushwork, allowing him to adhere to tradition while infusing it with a breath of fresh creativity. For this piece, Cao used his brush in an intentionally clumsy manner that creates a sense of timelessness and unaffected simplicity. The overall composition is upright and spacious, employing its ample negative space to share the harmonious beauty of uncluttered emptiness with the viewer. This work, brushed by Cao Rong in his sixty-fourth year, was donated to the National Palace Museum by Mr. Ts’ao Shu.

Exhibit List

| Title | Artist | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Ink Rubbing of a Damaged Stele Starting with the Word “Upright” | Han dynasty | |

| Ink Rubbing from a Roofing Tile with the Character “Protection” | Han dynasty | |

| Ink Rubbing of a Pagoda Inscription from Guanggu Buddhist Monastery | Northern Qi dynasty | |

| Copy of Four Pieces by Wang Xizhi and Sons | Chu Suiliang | Tang dynasty |

| Preface to the Collected Sagely Teachings | Huai Ren | Tang dynasty |

| Letter | Cai Xiang | Song dynasty |

| Letter | Su Shi | Song dynasty |

| Letter | Huang Tingjian | Song dynasty |

| Letter | Mi Fu | Song dynasty |

| Memorandum to a Supervisory Official | Cheng Yuanfeng | Song dynasty |

| Four Maxims from “A Summary of the Rules of Propriety” | Anonymous | Yuan dynasty |

| Copy of Chu Suiliang’s “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion” | Dong Qichang | Ming dynasty |

| Copy of the “Essay on Calligraphy” | Wang Jie | Qing dynasty |

| Ink Rubbing of a Copy of The Classic of Eternal Clarity and Stillness | Prince Aisin Gioro Yongxing | Qing dynasty |

| Thirteen-character Antithetical Couplet in Seal Script | Qian Dian | Qing dynasty |

| “Buddha of Boundless and Infinite Life” in Clerical Script | Cao Rong | Republican era |