Introduction

The history of Chinese painting can be compared to a symphony. The styles and traditions in figure, landscape, and bird-and-flower painting have formed themes that continue to blend to this day into a single piece of music. Painters through the ages have made up this "orchestra," composing and performing many movements and variations within this tradition.

It was from the Six Dynasties (222-589) to the Tang dynasty (618-907) that the foundations of figure painting were gradually established by such major artists as Gu Kaizhi and Wu Daozi. Modes of landscape painting then took shape in the Five Dynasties period (907-960) with variations based on geographic distinctions. For example, Jing Hao and Guan Tong depicted the drier and monumental peaks to the north while Dong Yuan and Juran represented the lush and rolling hills to the south in Jiangnan. In bird-and-flower painting, the noble Tang court manner was passed down in Sichuan through Huang Quan's style, which contrasts with that of Xu Xi in the Jiangnan area.

In the Song dynasty (960-1279), landscape painters such as Fan Kuan, Guo Xi, and Li Tang created new manners based on previous traditions. The transition in compositional arrangement from grand mountains to intimate scenery also reflected in part the political, cultural, and economic shift to the south. Guided by the taste of the emperor, painters at the court academy focused on observing nature combined with "poetic sentiment" to reinforce the expression of both subject and artist. Painters were also inspired by things around them, leading even to the depiction of technical and architectural elements in the late eleventh century. The focus on poetic sentiment led to the combination of painting, poetry, and calligraphy (the "Three Perfections") in the same work (often as an album leaf or fan) by the Southern Song (1127-1279). Scholars earlier in the Northern Song (960-1126) thought that painting as an art had to go beyond just the "appearance of forms" in order to express the ideas and cultivation of the artist. This became the foundation of the movement known as literati (scholar) painting.

The goal of literati painters in the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), including Zhao Mengfu and the Four Yuan Masters (Huang Gongwang, Wu Zhen, Ni Zan, and Wang Meng), was in part to revive the antiquity of the Tang and Northern Song as a starting point for personal expression. This variation on revivalism transformed these old "melodies" into new and personal tunes, some of which gradually developed into important traditions of their own in the Ming and Qing dynasties. As in poetry and calligraphy, the focus on personal cultivation became an integral part of expression in painting.

Starting from the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), painting often became distinguished into local schools that formed important clusters in the history of art. The styles of "Wu School" artists in the Suzhou area, for example, were based on the cultivated approaches of scholar painting by the Four Yuan Masters. The "Zhe School" consisted mostly of painters from the Zhejiang and Fujian areas; also active at court, they created a direct and liberated manner of monochrome ink painting based on Southern Song models.

The late Ming master Dong Qichang from Songjiang and the Four Wangs (Wang Shimin, Wang Jian, Wang Hui, and Wang Yuanqi) of the early Qing dynasty (1644-1911) adopted the lofty literati goal of unifying certain ancient styles into a "grand synthesis" so that all in mind and nature could be rendered with brush and ink. The result was the vastly influential "Orthodox School," which was supported by the Manchu Qing emperors. The court also took an interest in Western painting techniques (brought by European missionaries) that involved volume and perspective, which became known to and used by some Chinese painters to create a fused style. Outside the court, the major commercial city of Yangzhou developed the trend toward individualism to become a center for "eccentric" yet professional painters. It also spread to Shanghai, where the styles of artists were also inspired by "non-orthodox" manners, which themselves became models for later artists.

Thus, throughout the ages, a hallmark of Chinese painting has been the pursuit of individuality and innovation within the framework of one's "symphonic" heritage. This exhibition represents a selection of individual "performances" from the Museum collection arranged in chronological order in order to provide an overview of some major traditions and movements in Chinese painting.

Selections

Snow-covered Bamboo and Frigid Birds

- Anonymous, Song dynasty

Snowflakes flurry downwards on an icy winter's day; in one small corner of the world, three sparrows alight atop a tree branch to huddle in the cold. The trio of tiny birds keep watch upon one another, instilling the frozen scene with an abundance of vitality.

The twists and turns of the tree's branches in this piece were painted with great attention to detail. To one side they are set off by leaves of bamboo, giving this painting a stylistic element that was endemic to Southern Song dynasty court painting. Originally part of a circular fan, the rounded canvas was later mounted in order to join the leaves of an album. This work is the first leaf in "A Collection of Paintings by Song Dynasty Personages."

A Cluster of Chrysanthemums

- Attributed to an anonymous Yuan dynasty artist

Flowers fill the entirety of this painting of a collection of chrysanthemums in splendid full bloom. Amid the blossoms are embellishments of Taihu stones, butterflies, and other insects—elements which show that the artist was an inheritor of the style of magnificent flower-and-bird themed paintings meant to decorate palaces established by the Southern Tang dynasty artist Xu Xi (fl. ca. 10th century).

Numerous chrysanthemum varietals are depicted in this work, and some of the leaves are inscribed with varietals' names written in golden ink. Names such as "hanging silk chrysanthemum" and "eastern slope chrysanthemum" can be discerned, while others have become illegible. The painting's overall style is a continuation of the appreciation for botany that became prominent in Southern Song court painting.

New Year's Day

- Attributed to an anonymous Song dynasty artist

Its name a reference to the first day of the lunar calendar, this painting conveys wishes for a year with good fortune in all one's affairs. A pair of pheasants can be seen near a stream, surrounded by narcissus, camellia, and plum blossoms. Green bamboo adds lively contrast to this painting's classically refined color palette.

This work has historically been attributed to an artist active during the Song dynasty, but its brush techniques, color scheme, and composition—which combines elements of landscape and flower-and-bird painting—suggest that it was painted during the Ming dynasty by an artist who was influenced by court painter Lü Ji (ca. 1429-1505). This piece is thematically and compositionally similar to the fourth painting in Lü Ji's series in "Flowers and Plants of the Four Seasons," which depicts winter and is held in the Tokyo National Museum. The similarity indicates that this painting may originally have been meant as a wintry flowers-and-birds scene in a series of seasonal paintings.

Mount Shu

- Xu Ben (1335-1380), Ming dynasty

Xu Ben (1335-1380) had the style name Youwen and the sobriquet Scholar of the Northern Walls (Beiguosheng). When Zhang Shicheng rose against the Yuan dynasty, Xu was called to join his forces. He later lived as a recluse with Zhang Yu on Mount Shu in Huzhou (south of Mount Bian in present day Wuxing in Zhejiang province).

Xu Ben painted this work and inscribed it with a poem as a gift for "Mountain Man Lü," a friend from the territory of Wu who visited him at his home on Mount Shu. Zhang Yu added a poetic colophon that states this painting was made for "the studious mountain man." From this we can surmise that the recipient was Lü Min, who, along with Xu Ben, Zhang Yu, and Song Ke, was one of the "Ten Friends of the Northern Wall." Lü Min, a Daoist poet who lived during the late Yuan and early Ming dynasties, had the sobriquet Zhixue, meaning "studious." Song Ke left an inscription dated to the xin-hai year of Emperor Hongwu's reign (1371); the painting was likely completed at an earlier date.

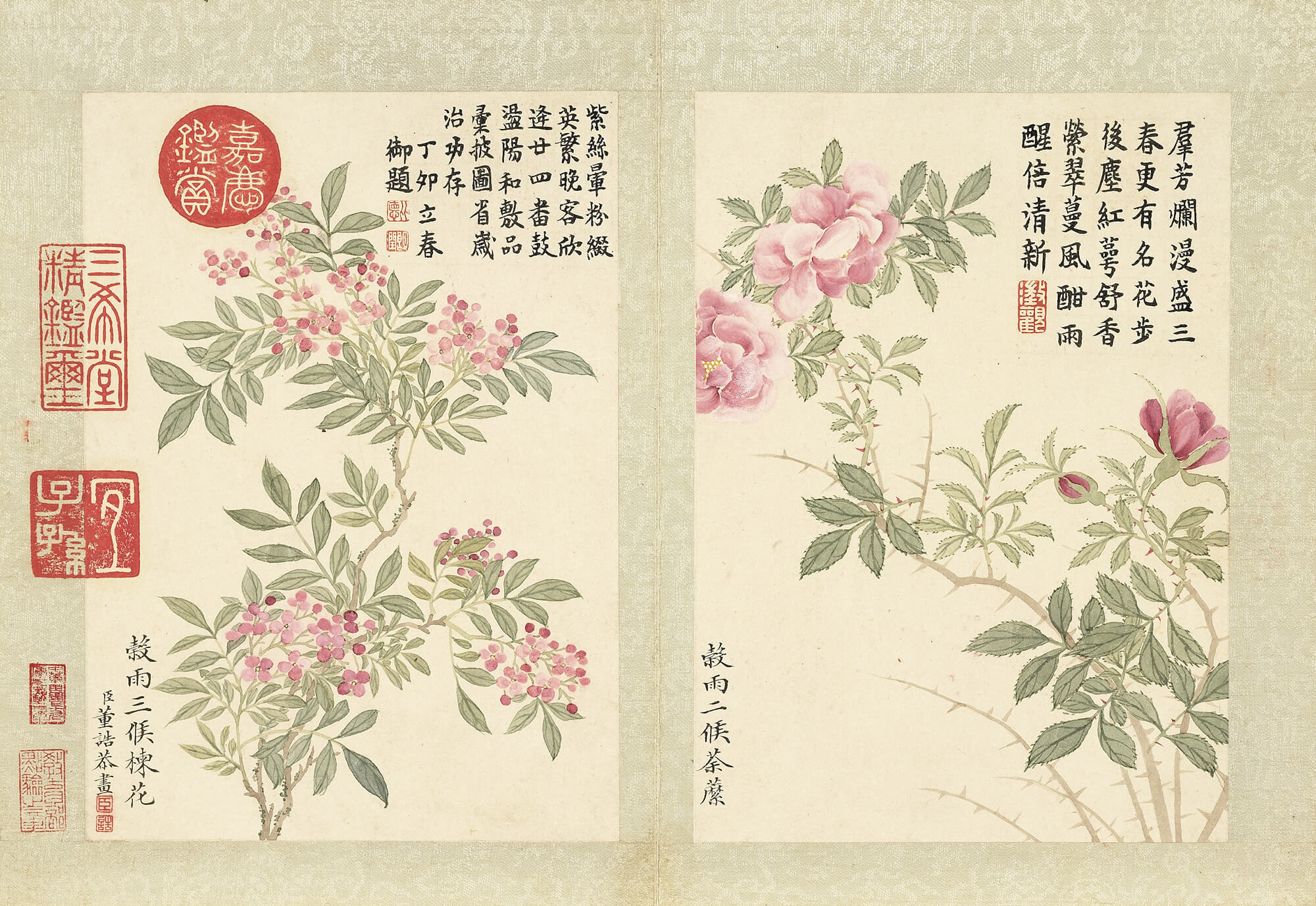

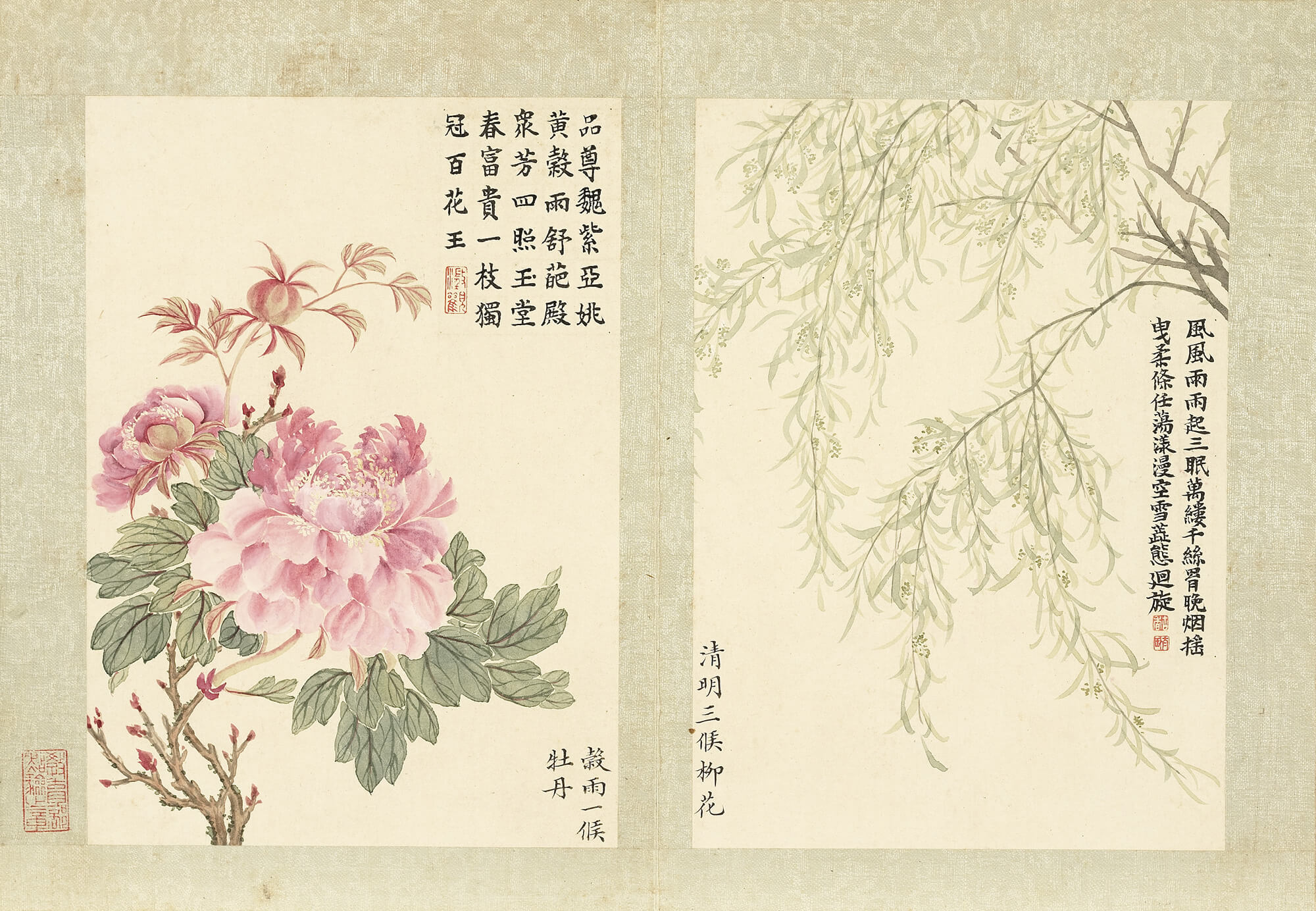

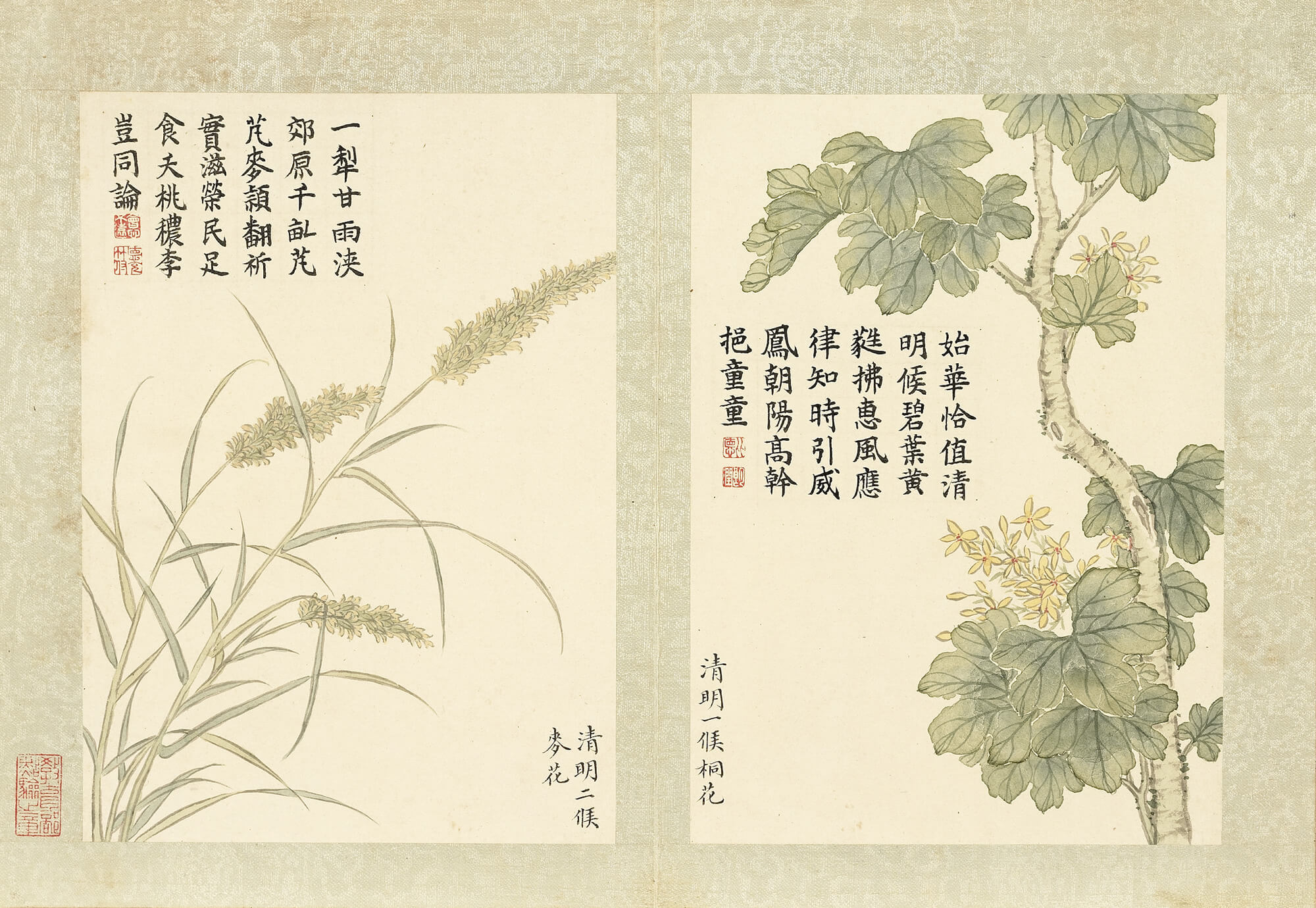

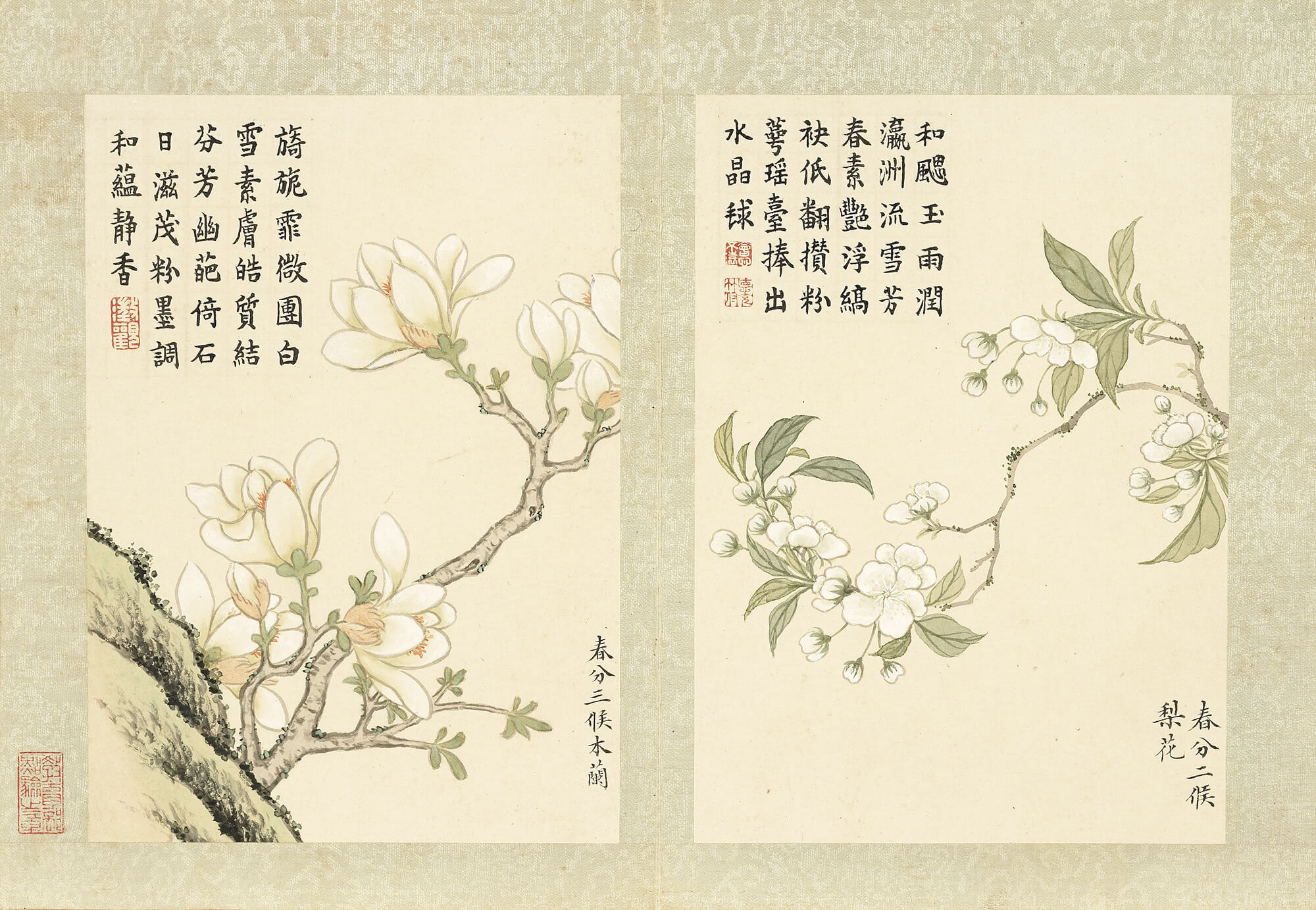

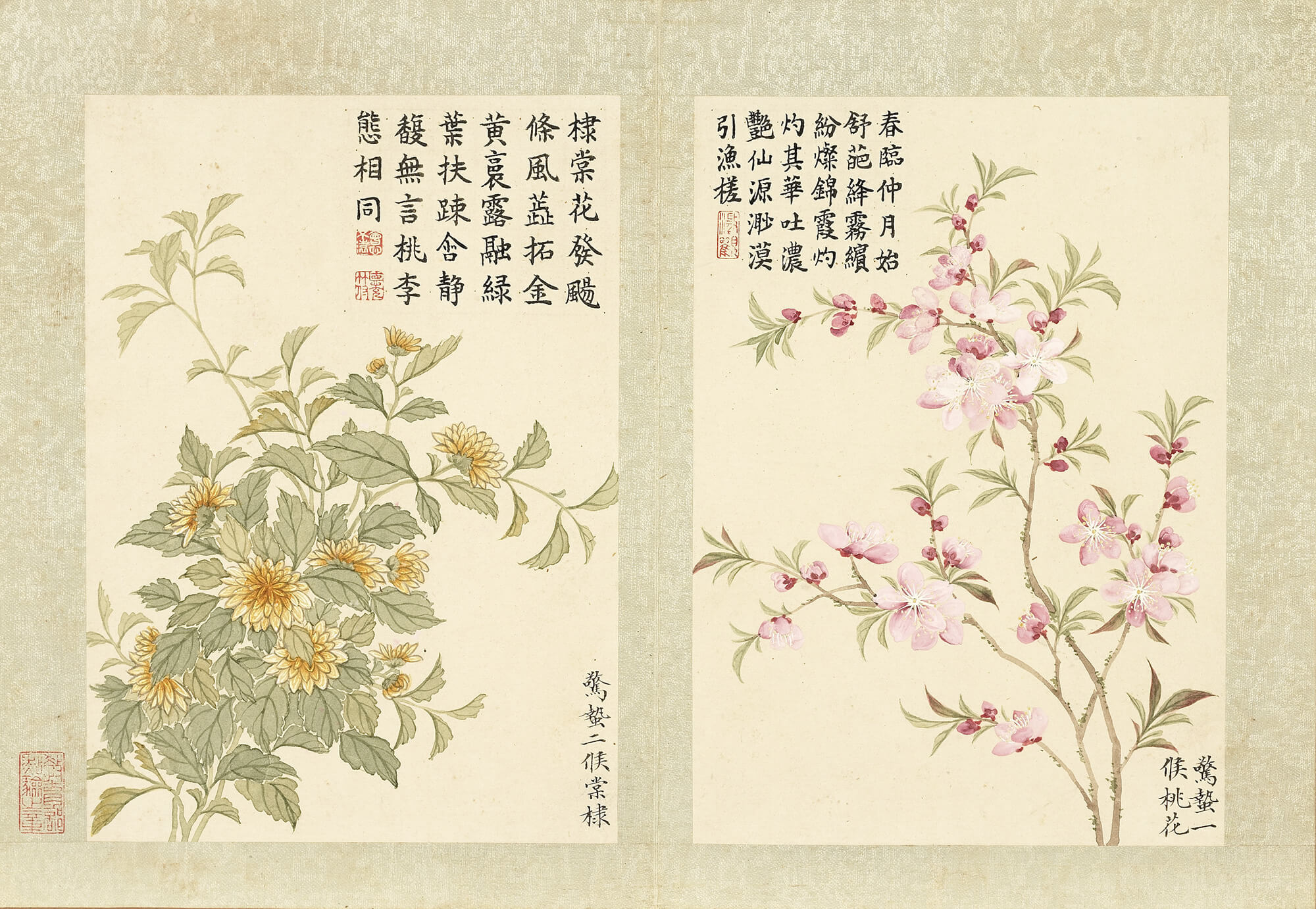

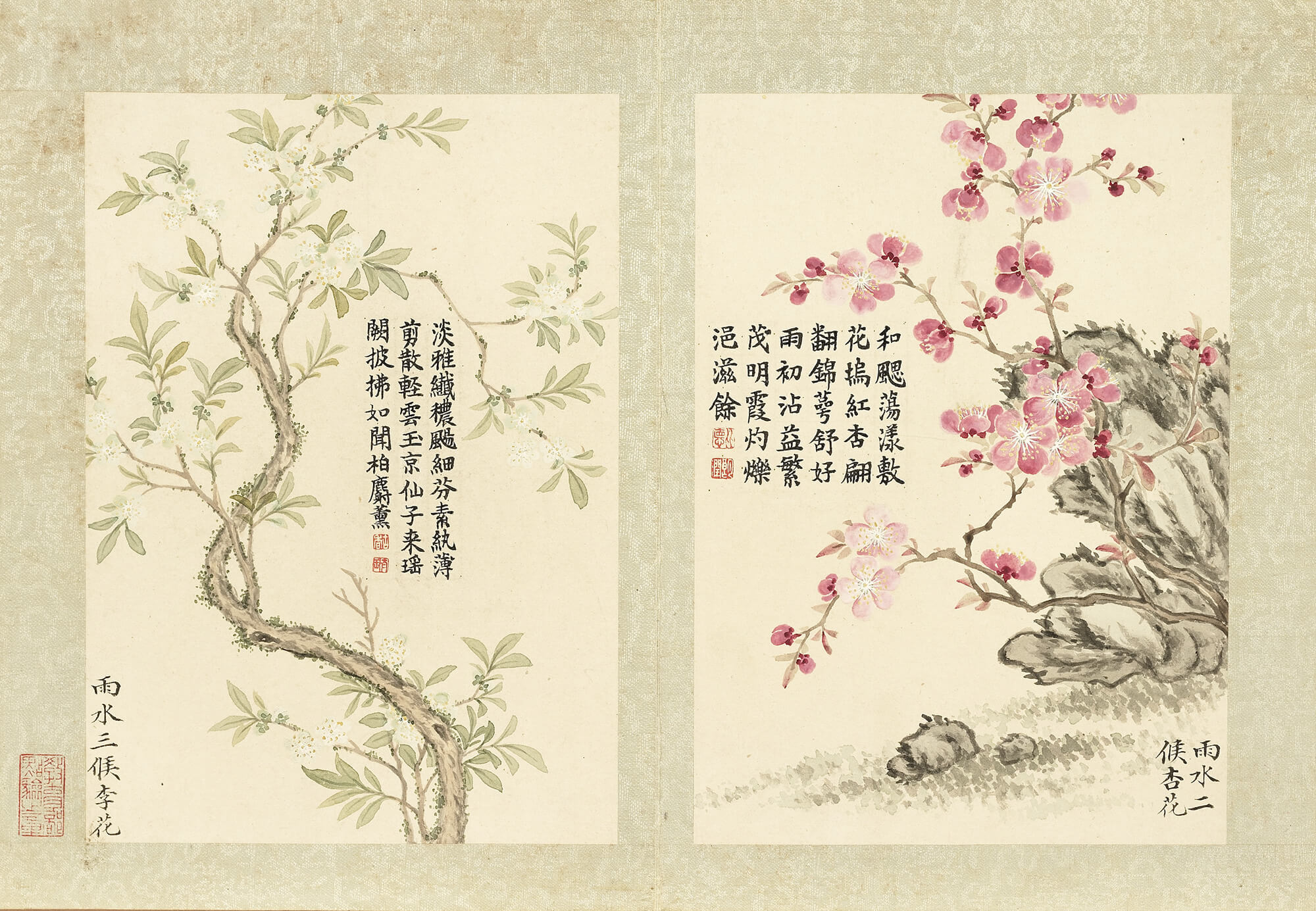

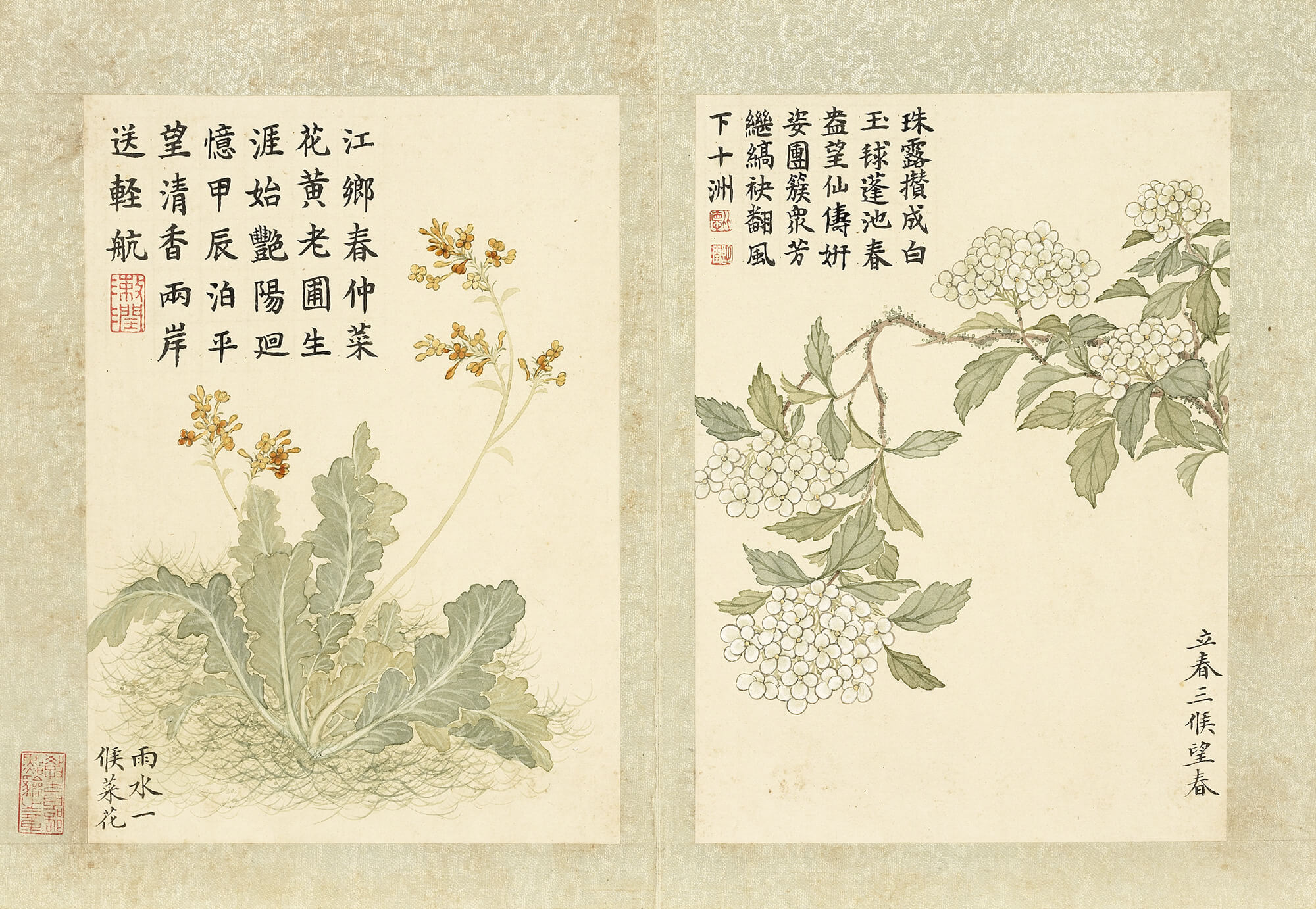

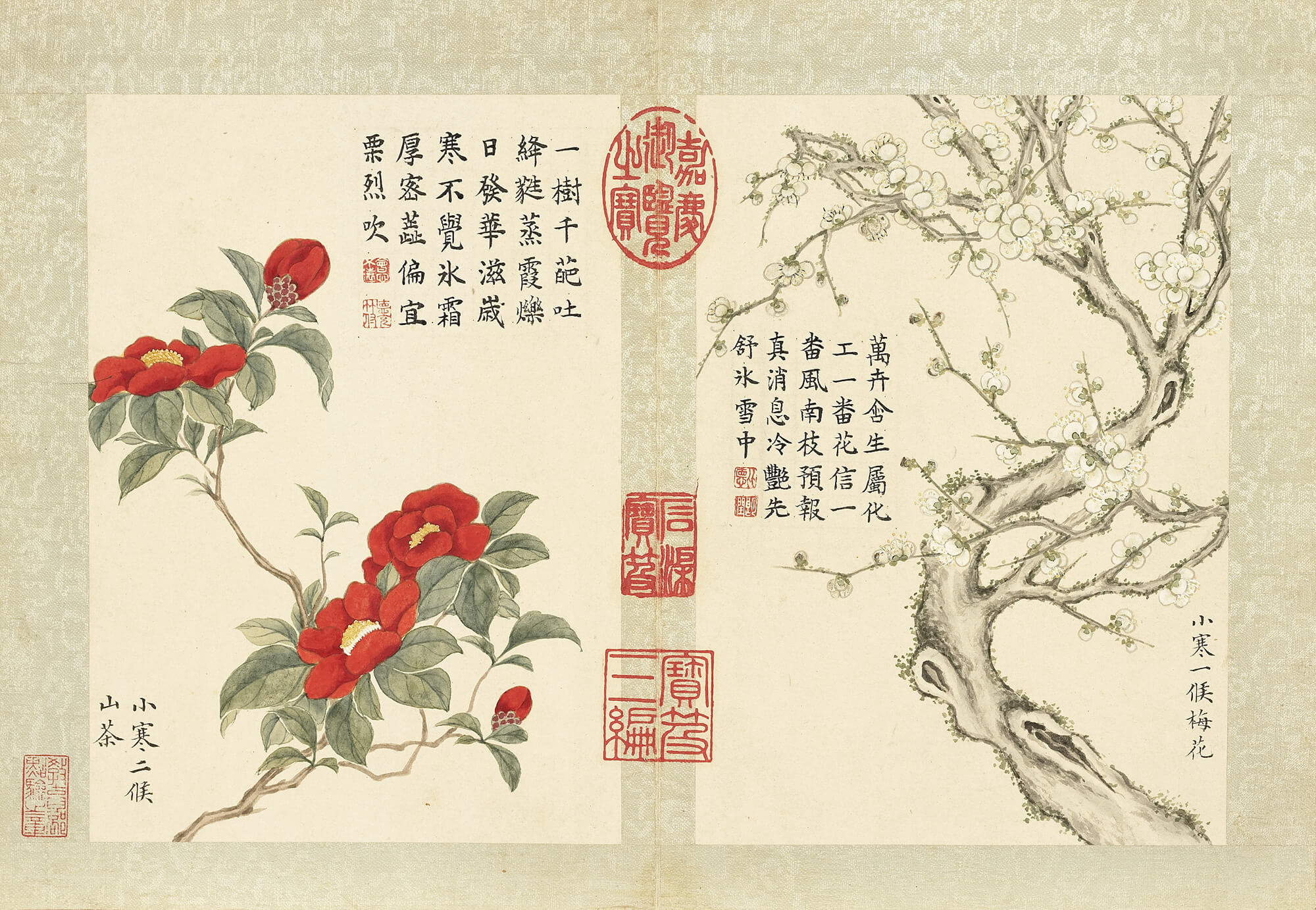

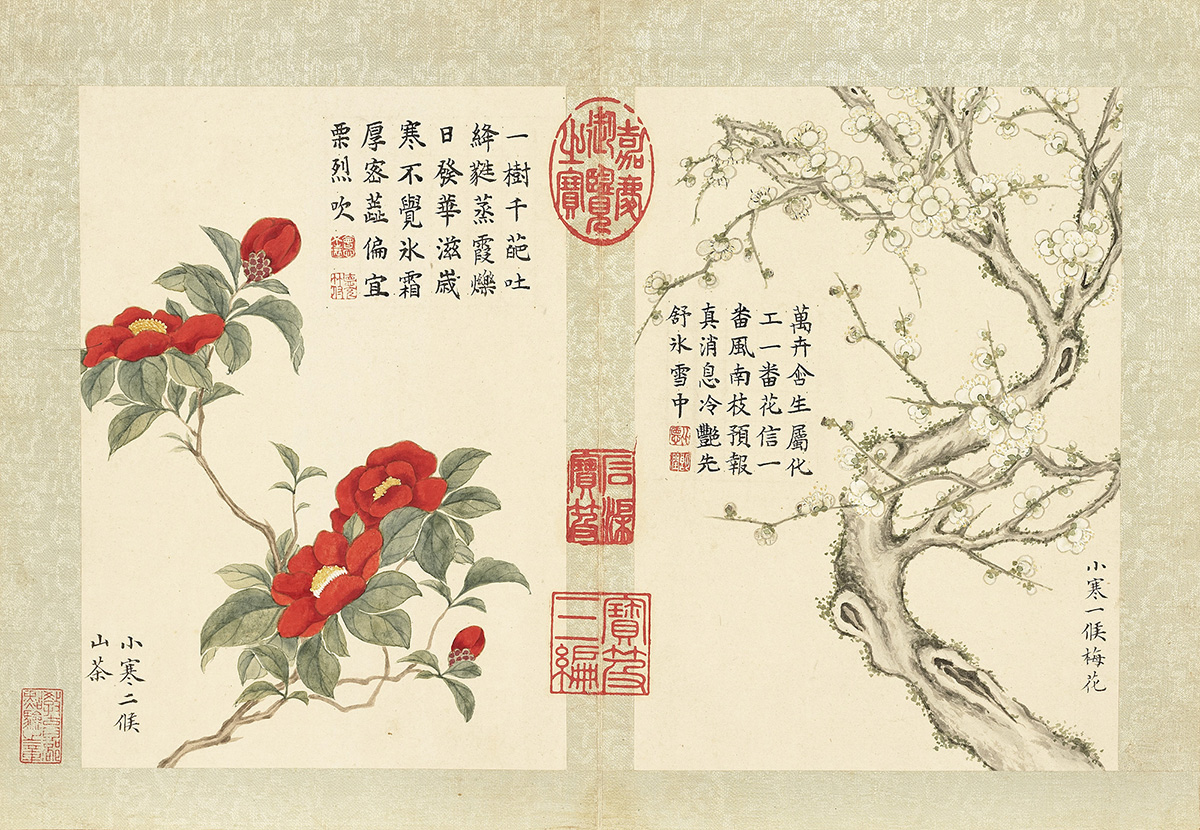

Twenty-four Paired Illustrations of the Flowery Winds of Promise

- Dong Gao (1740-1818), Qing dynasty

The ancients associated spring winds with the keeping of promises, because they arrive just when expected and coax countless flowers to burst into bloom. For this reason, spring breezes are called "flowery winds of promise." Spring covers four months and eight solar terms, from the twenty-third solar term, "lesser cold," to the sixth, "grain rain." There are twenty-four "flowery winds of promise" during this time, starting with plum blossoms, and finishing with chinaberry flowers.

The album comprises twelve leaves and a total of twenty-four paintings, one for each of the springtime winds. The painter, Dong Gao (1740-1818), had the style name Xijing and the sobriquet Zhelin. Hailing from Fuyang in Zhejiang province, he was the eldest son of Dong Bangda (1699-1769). Dong took up a post in the Southern Study in the Forbidden City during Emperor Qianlong's reign; he was promoted to grand secretary of the secretariat in the first year of Emperor Jiaqing's reign (1796).

Exhibit List

| Title | Artist/ Period |

|---|---|

| Drunken Chrysanthemums | Attributed to Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322), Yuan dynasty |

| Inquiring about the Way | Attributed to Yan Lide (?-656), Tang dynasty |

| Snow-covered Bamboo and Frigid Birds | Anonymous, Song dynasty, |

| Flowers and Plants of the Four Seasons | Attributed to Lin Chun (fl.1174-1189), Song dynasty |

| A Dragon Soaring amid Thunder and Rain | Attributed to Chen Rong (ca. 1200-1266), Song dynasty |

| Clouds and Pines in an Ancient Valley | Boyan Buhua (Bayan Buga Tegin, ?-1359), Yuan dynasty |

| A Cluster of Chrysanthemums | Attributed to an anonymous Yuan dynasty artist |

| New Year's Day | Attributed to an anonymous Song dynasty artist |

| A Portrait of Liu Haichan | Attributed to an anonymous Yuan dynasty artist |

| Mount Shu | Xu Ben (1335-1380), Ming dynasty |

| A Cicada Startles a Pekingese | Li Ao (dates of birth and death unknown), Ming dynasty |

| A Host of Immortals | Attributed to Leng Qian (fl. ca. 14th century), Ming dynasty |

| Plum Blossoms and Bamboo | Chen Hongshou (1599-1652), Ming dynasty |

| Fishing | Wu Ling (fl. ca. 17th century), Ming dynasty |

| Twenty-four Paired Illustrations of the Flowery Winds of Promise | Dong Gao (1740-1818), Qing dynasty |

| Listening to the Rain on Xiaoxiang River | Wang Hui (1632-1717), Qing dynasty |

| Ramadas in a Forest under Misty Peaks | Song Junye (?-1713), Qing dynasty |

| After Ni Zan and Huang Gongwang's Landscap | Wang Yuanqi (1642-1715), Qing dynasty |

| Clear Skies after an Autumn Rain in the Imperial Gardens | He Yi (1667-1744), Qing dynasty |

| Tuning Yingzhong | Zhou Kun (fl. early 18th century), Qing dynasty |

| Dalv Xinghui | Yu Xing (ca. 1692-after 1767), Qing dynasty |

| Clearing after Snowfall in the Taihang Mountains | Attributed to an anonymous Yuan dynasty artist |

| “Falling Flowers” Painting and Poems | Shen Zhou (1427-1509), Ming dynasty |

| An Album of Landscapes | Lan Ying (1585-1664), Ming dynasty |

| Five Purities | Wu Hufan (1894-1968), Lu Yifei (1908-1997), Yu Caizi (1915-1992), Zhu Meicun (1911-1993), Zhang Zijing, and Wu Shaoyun, Republican era |