Selections

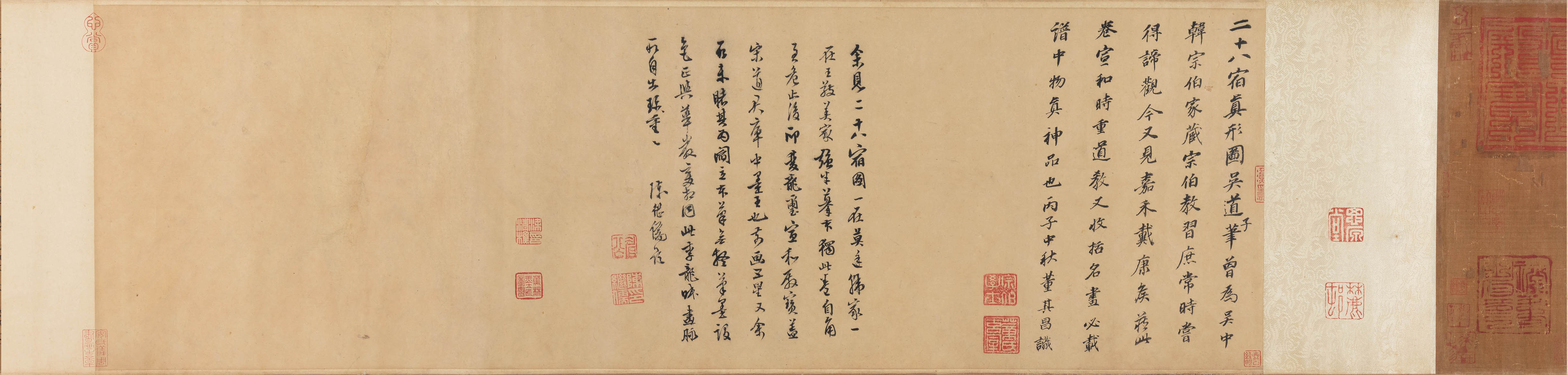

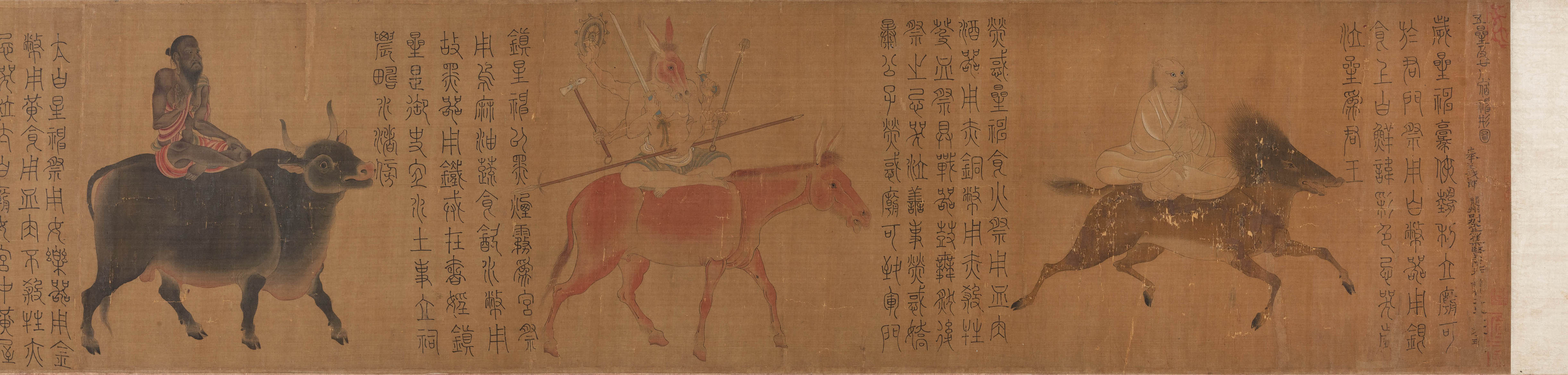

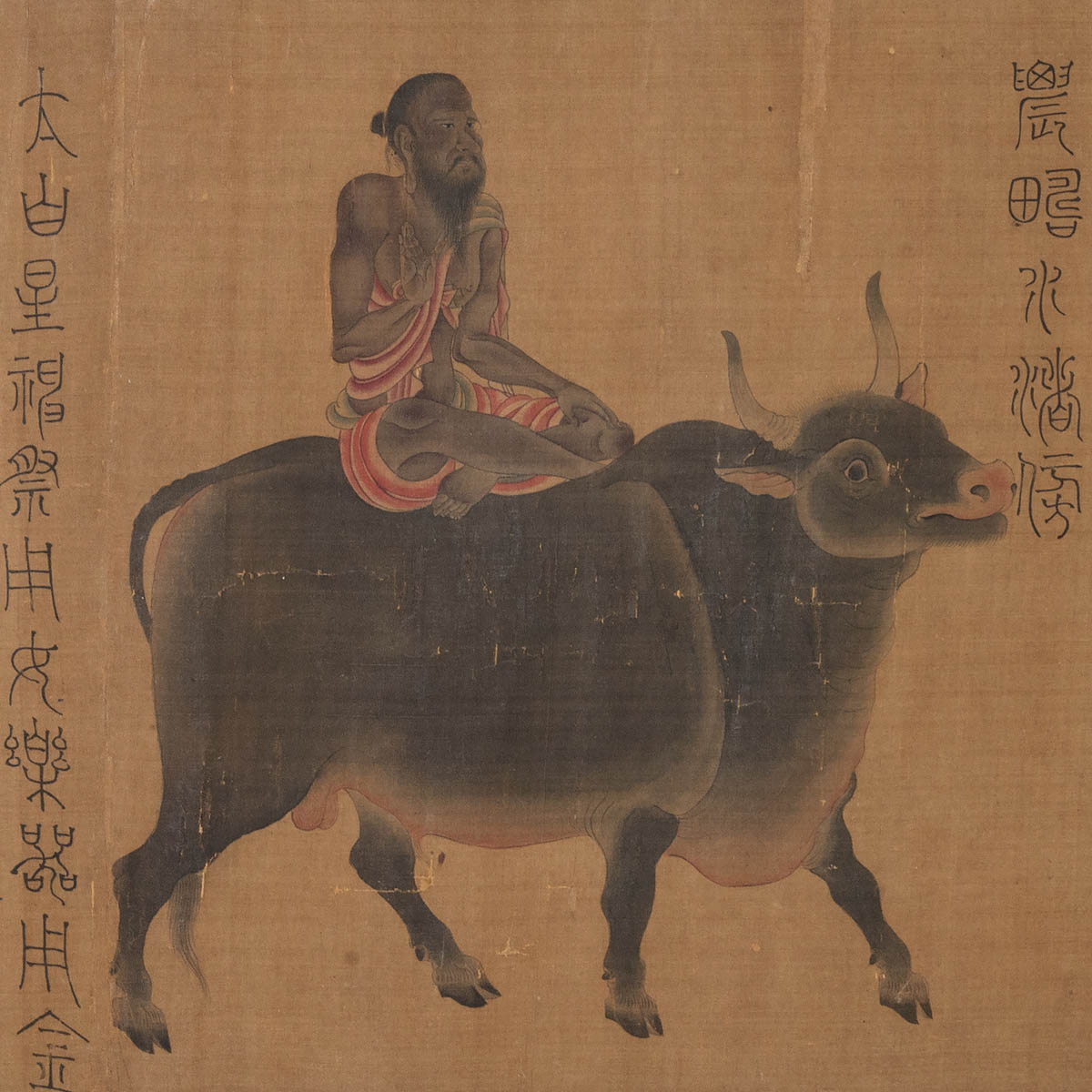

The Five Planets and Twenty-Eight Constellations

The Five Planets and Twenty-Eight Constellations

- Zhang Sengyou (479-?), Liang dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

This handscroll painting depicts personifications of spirits and beings associated with five planets and 28 constellations in traditional Chinese astronomy. Next to each is an explanatory inscription in seal script calligraphy, the contents giving the name, disposition, and sacrifices for each. Today, only seventeen of the figures survive. The painting features these spirits in human form, with animals, or as animal-headed figures in a variety of different and unusual manners. The style in terms of execution is quite precise and reveals a high quality of rendering.

Attributions for the period and artist of this handscroll include Zhang Sengyou of the Southern Dynasties era. Another opinion is that it comes from the hand of the Tang dynasty artist Liang Lingzan or is a later tracing copy after Liang's original. Scholars, however, have yet to reach a consensus.

Attributions for the period and artist of this handscroll include Zhang Sengyou of the Southern Dynasties era. Another opinion is that it comes from the hand of the Tang dynasty artist Liang Lingzan or is a later tracing copy after Liang's original. Scholars, however, have yet to reach a consensus.

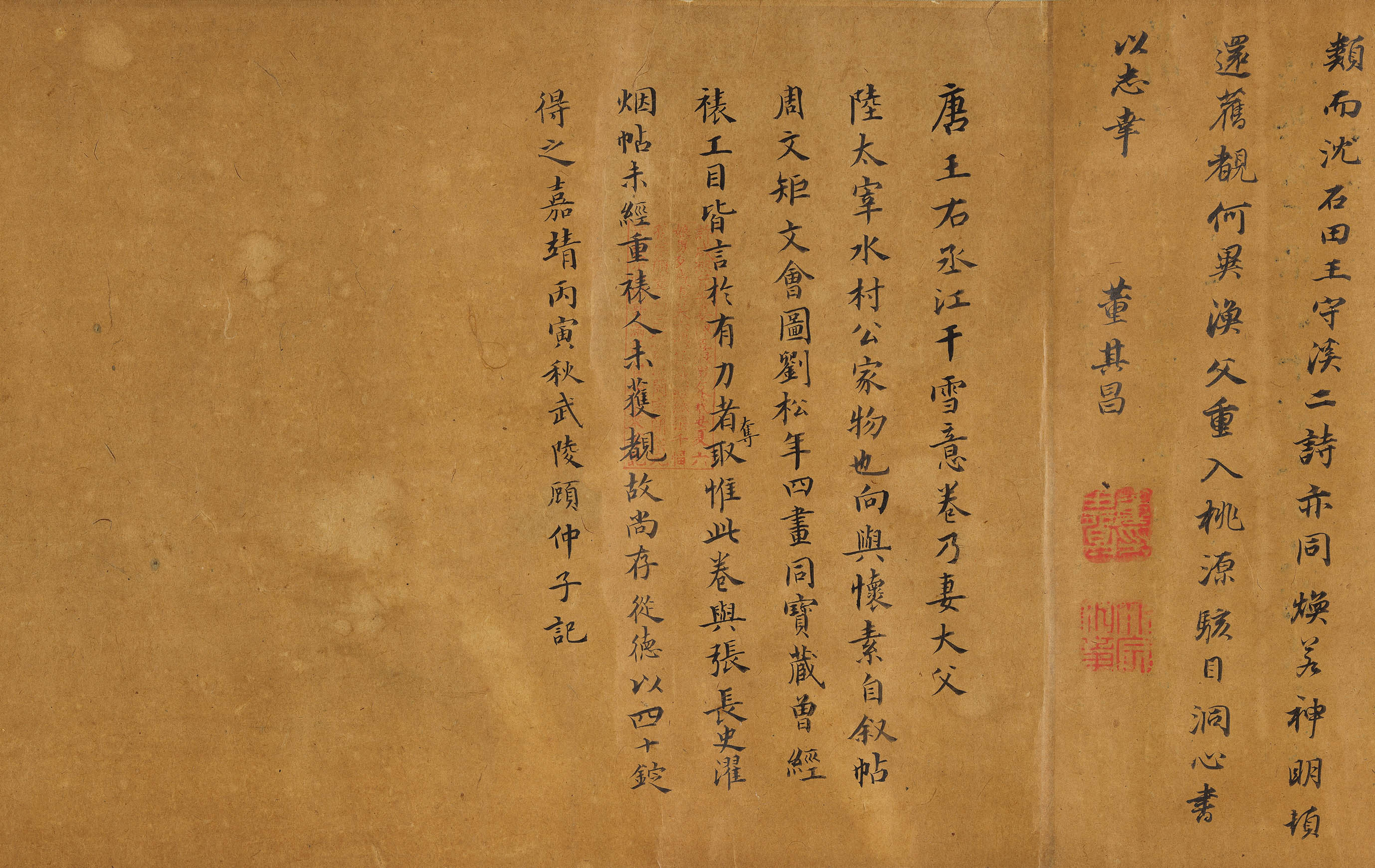

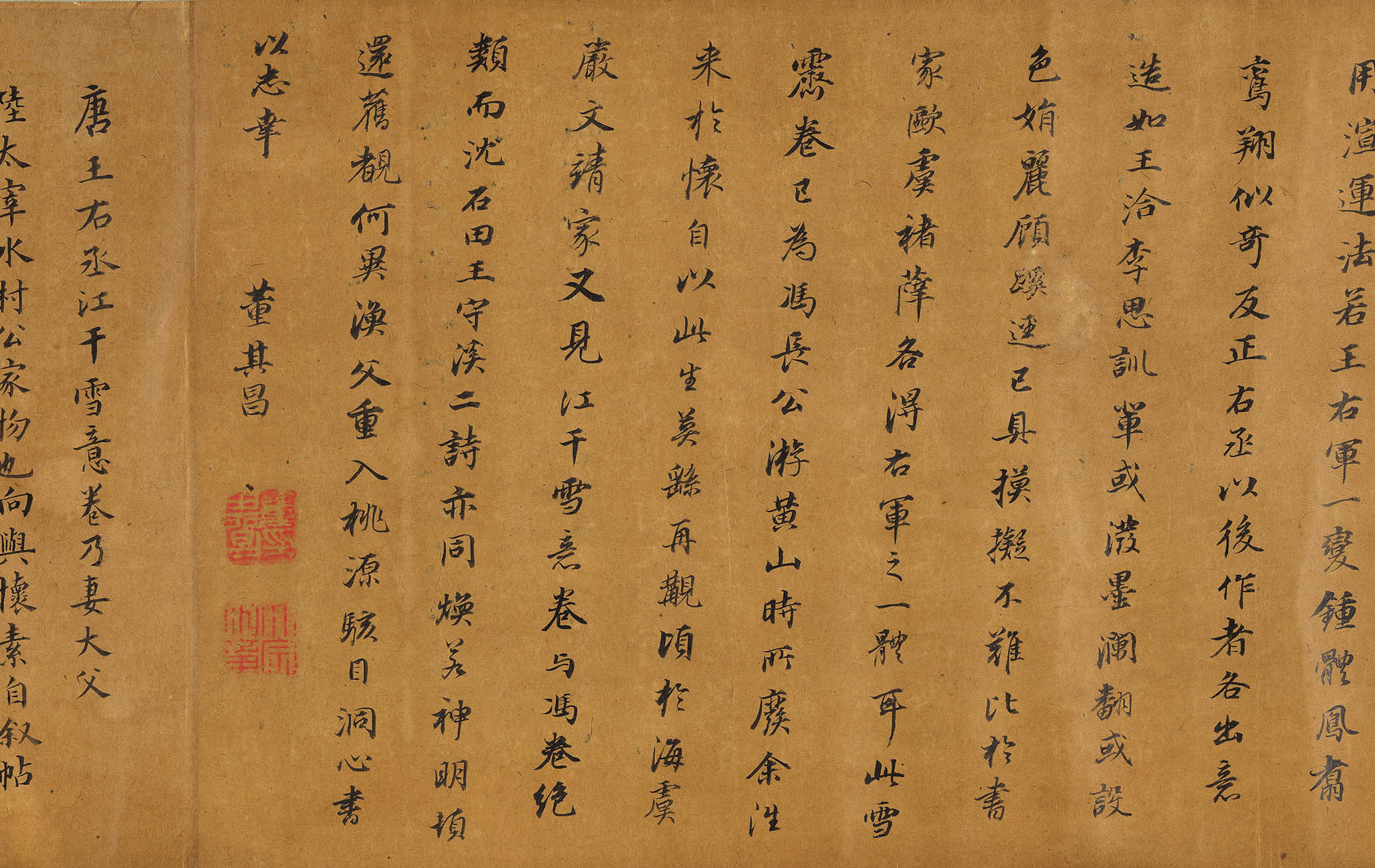

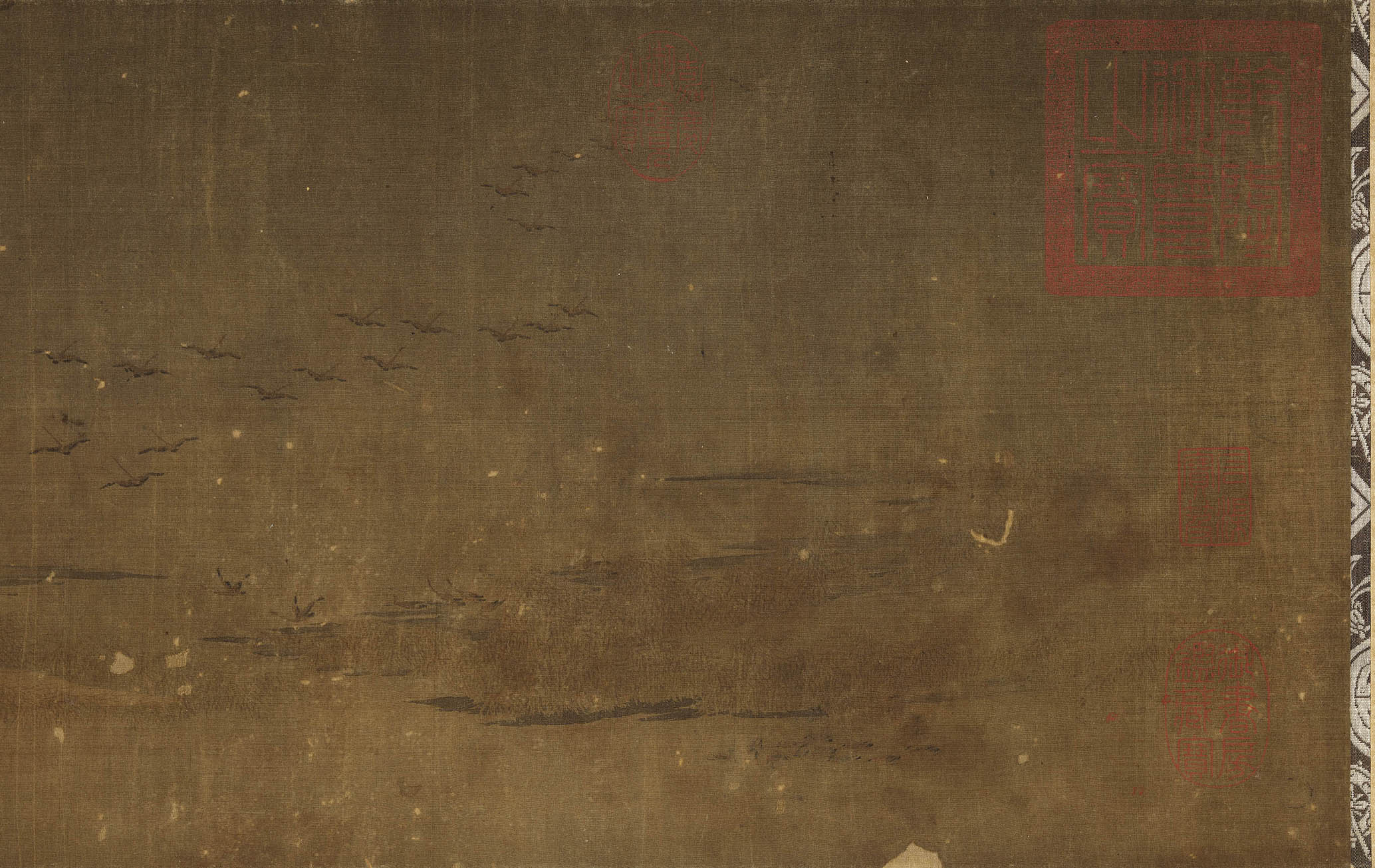

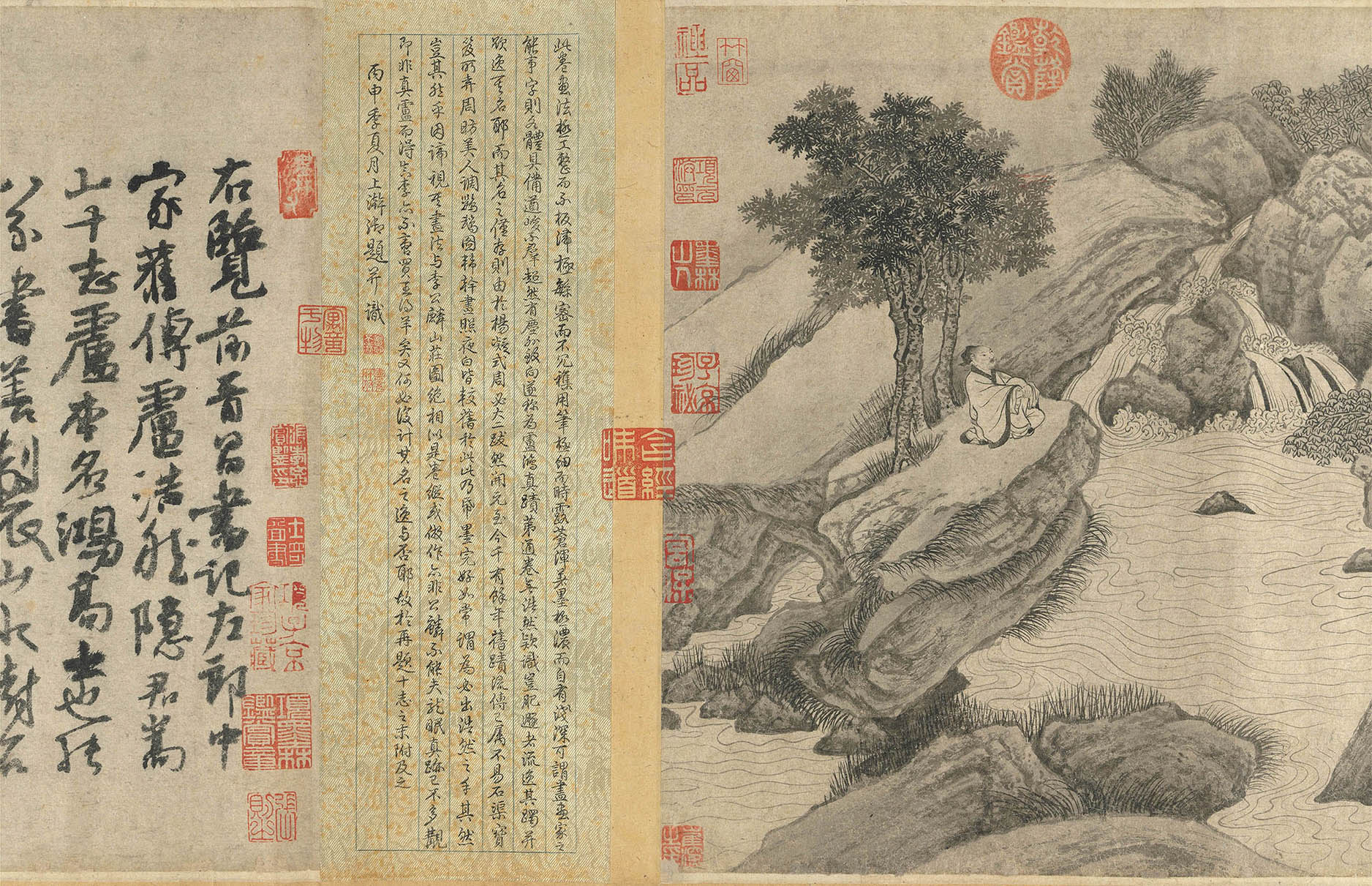

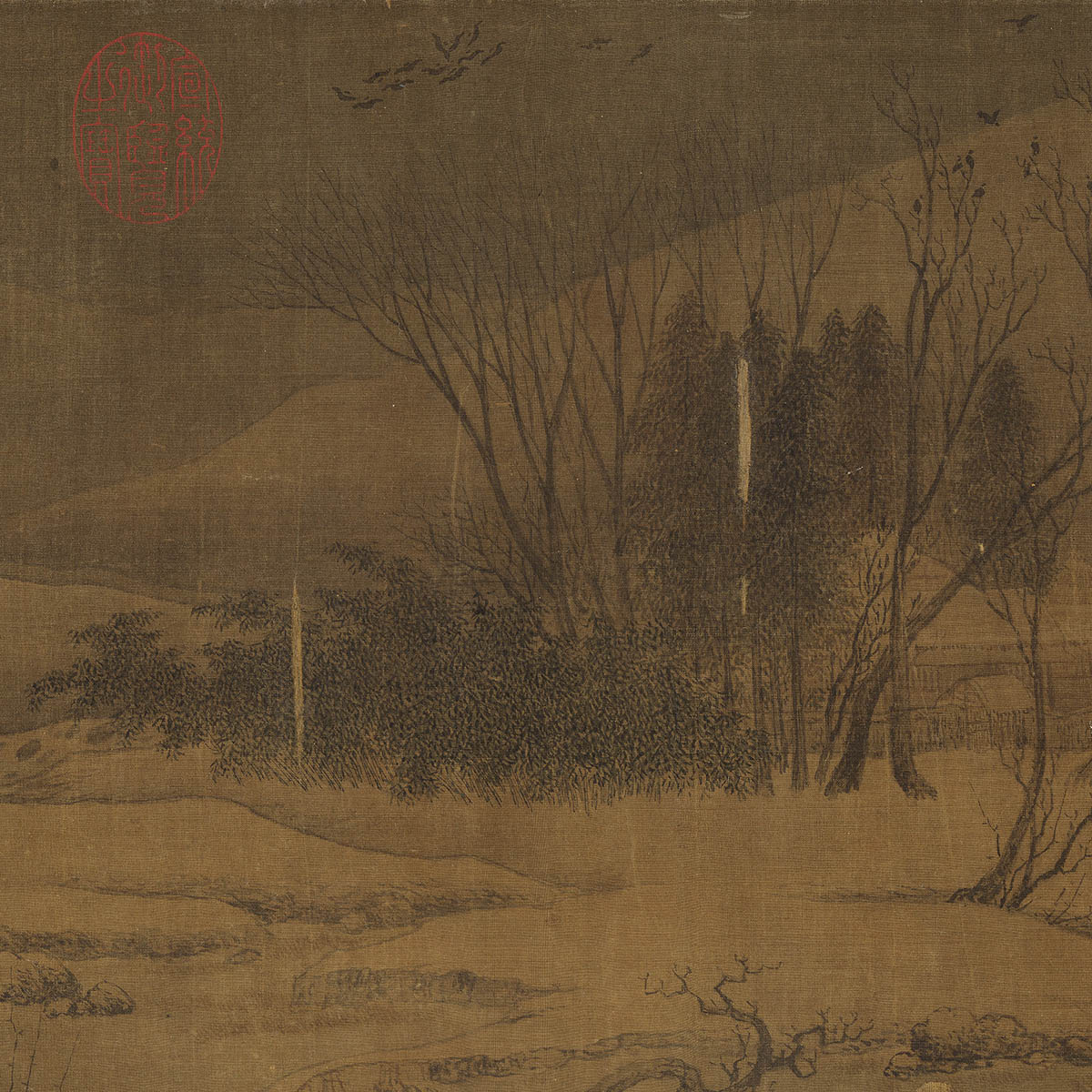

The Idea of Snow on a River

The Idea of Snow on a River

- Wang Wei (701-761), Tang dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in April 2014 as a Significant Historical Artifact

Wang Wei (style name Mojie; alternate birth and death given as 699-759) was a famous poet of the Tang dynasty also renowned for painting and calligraphy. His landscape paintings focused mainly on scenery inspired by particular ideas or poetic concepts.

In this handscroll painting of a frigid river in winter is a scene of village huts by banks as a blanket of snow covers the ground, its trees and vegetation long since withered. Formations of wild geese in the sky give this lonely, desolate scene a hint of life. Judging from the painting style, the soft and elegant method of rendering appears closer to that of Zhao Lingrang (11th-12th c.) in the Northern Song, thus suggesting it is not actually by Wang Wei.

In this handscroll painting of a frigid river in winter is a scene of village huts by banks as a blanket of snow covers the ground, its trees and vegetation long since withered. Formations of wild geese in the sky give this lonely, desolate scene a hint of life. Judging from the painting style, the soft and elegant method of rendering appears closer to that of Zhao Lingrang (11th-12th c.) in the Northern Song, thus suggesting it is not actually by Wang Wei.

The Heavenly King Sees Off His Son

The Heavenly King Sees Off His Son

- Wu Daoxuan (?-792), Tang dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

This handscroll painting also goes by the title "The Birth of Shakyamuni" and describes the birth of Shakyamuni Buddha. Towards the end of the scroll to the left is a depiction of his father King Suddhodana holding Prince Siddhartha, the future Buddha. Also shown is his mother Queen Maya making offerings at a shrine as deities pay homage to the Buddha, demonstrating the venerated status of the infant shown here.

Wu Daoxuan early had the name Daozi and came to be honored as the "Sage of Painting" in Chinese art. He excelled at depicting Buddhist and Daoist images as well as figures, excelling especially at wall painting. This work retains the brush manner associated with his "Wu Style" along with features of arrangements found in early Chinese figure painting. This handscroll is probably a copy or a copy thereafter attributed to Wu at a later date.

Wu Daoxuan early had the name Daozi and came to be honored as the "Sage of Painting" in Chinese art. He excelled at depicting Buddhist and Daoist images as well as figures, excelling especially at wall painting. This work retains the brush manner associated with his "Wu Style" along with features of arrangements found in early Chinese figure painting. This handscroll is probably a copy or a copy thereafter attributed to Wu at a later date.

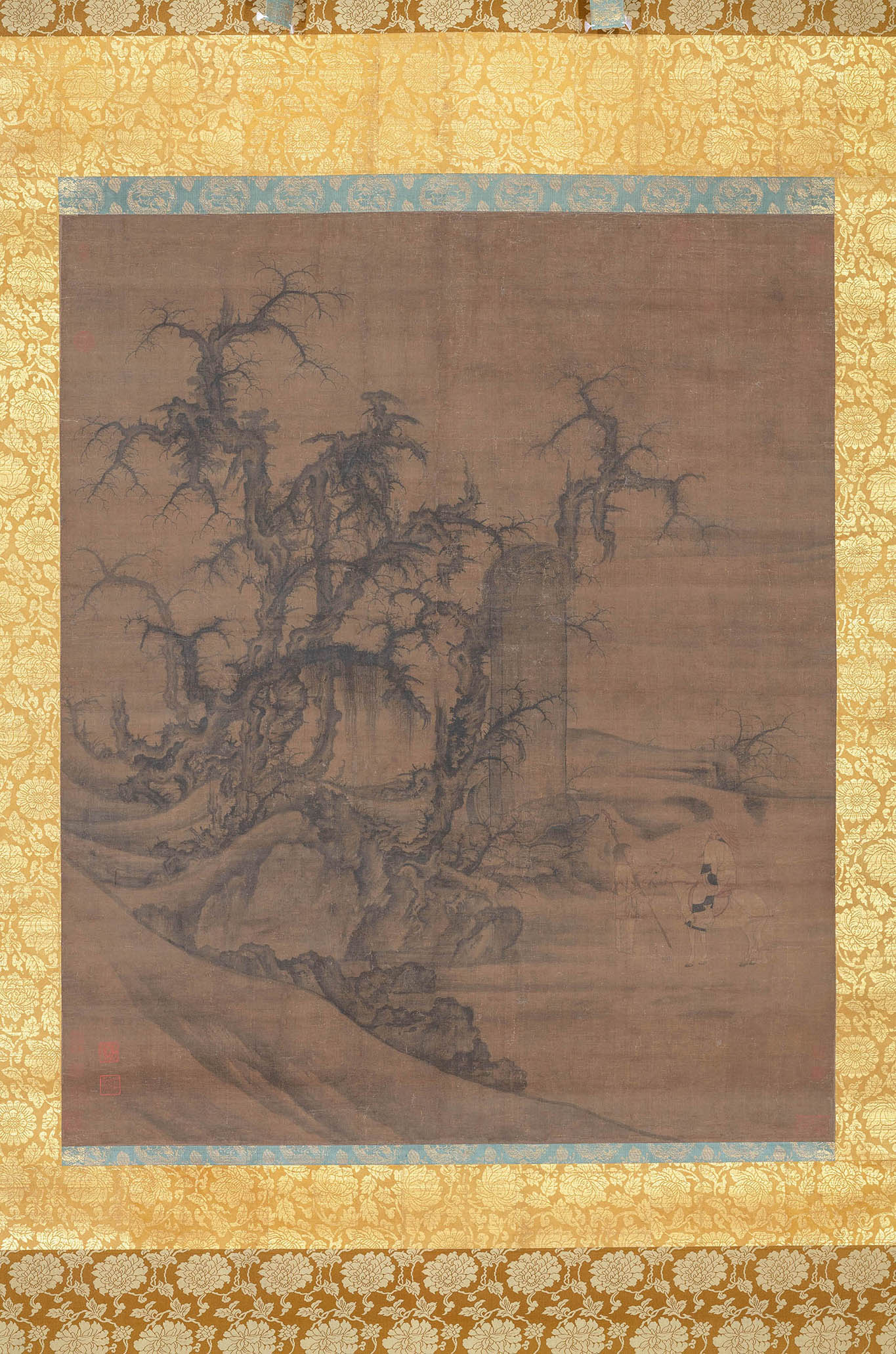

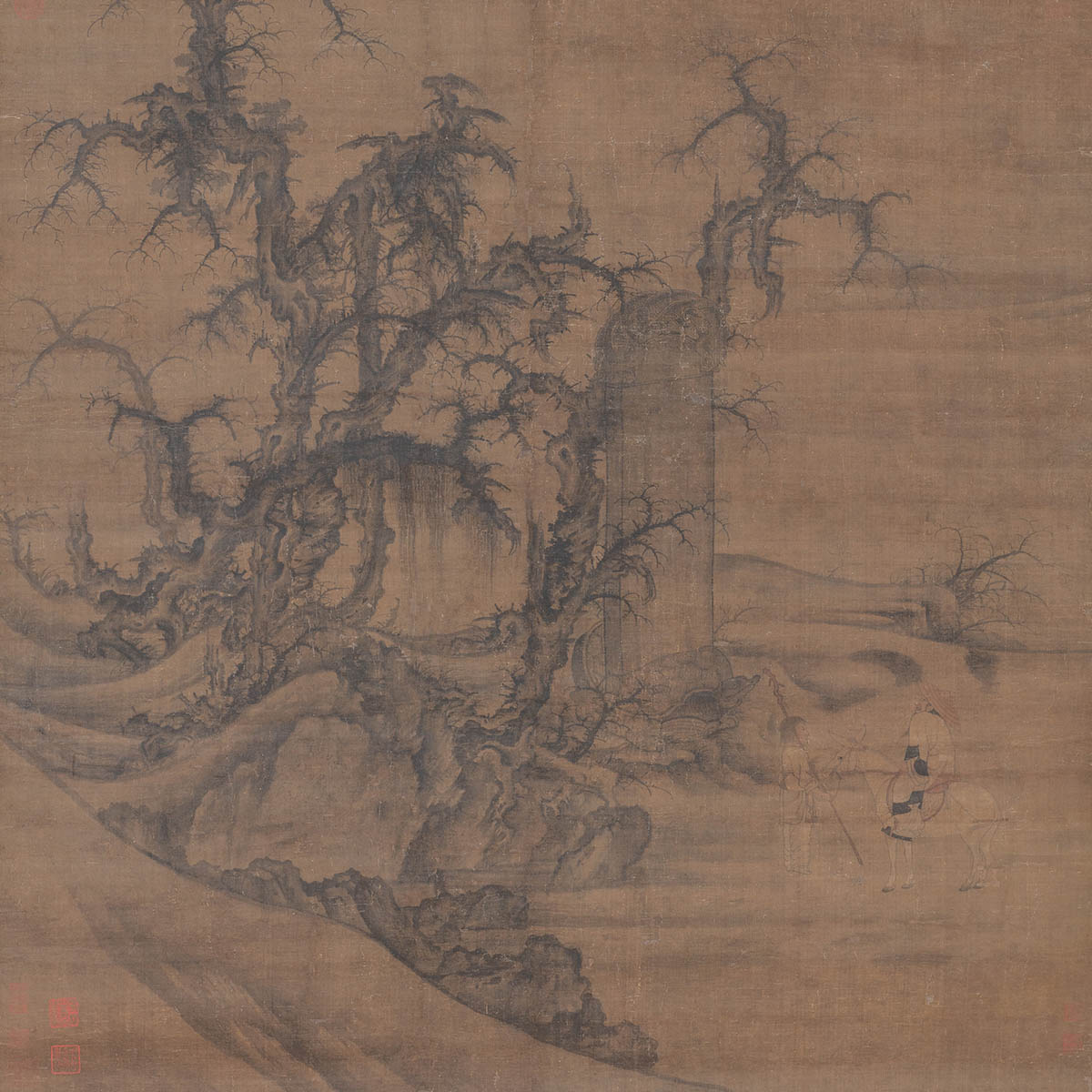

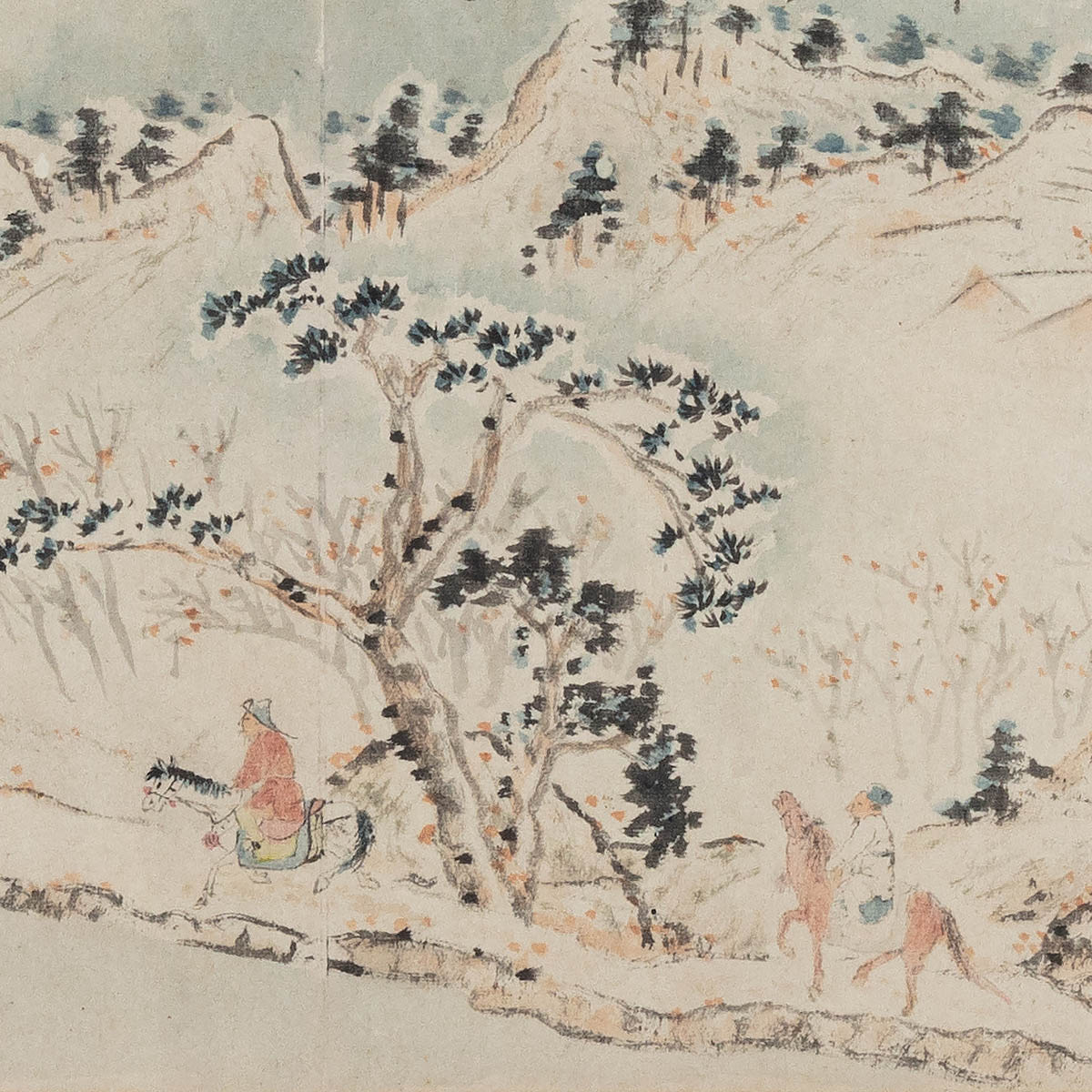

Reading the Memorial Stele

Reading the Memorial Stele

- Li Cheng (919-967) and Wang Xiao (fl. mid-10th c.), Song dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

This painting, done on two adjoining bolts of silk, depicts desolate scenery on a winter's day. An older figure on a donkey with a child attendant has come to stop in front of an old official stele that he is reading. The side of the stele reveals a faint signature: "Figures by Wang Xiao, trees and rocks by Li Cheng."

Li Cheng, originally from Chang'an (modern Xi'an in Shaanxi) and excelling at landscape painting, rendered mostly level-distance scenes of desolate and expansive landscapes. The rocks in his works are noted for "curled-cloud" texture strokes. For his wintry trees, he created the "craw-claw" method. His style came to have a major influence on the development of Northern Song landscape painting. Wang Xiao, a painter of the Five Dynasties to early Song period, was a native of Sizhou (modern Sishui County, Shandong) who excelled at depicting birds as well as figures.

Li Cheng, originally from Chang'an (modern Xi'an in Shaanxi) and excelling at landscape painting, rendered mostly level-distance scenes of desolate and expansive landscapes. The rocks in his works are noted for "curled-cloud" texture strokes. For his wintry trees, he created the "craw-claw" method. His style came to have a major influence on the development of Northern Song landscape painting. Wang Xiao, a painter of the Five Dynasties to early Song period, was a native of Sizhou (modern Sishui County, Shandong) who excelled at depicting birds as well as figures.

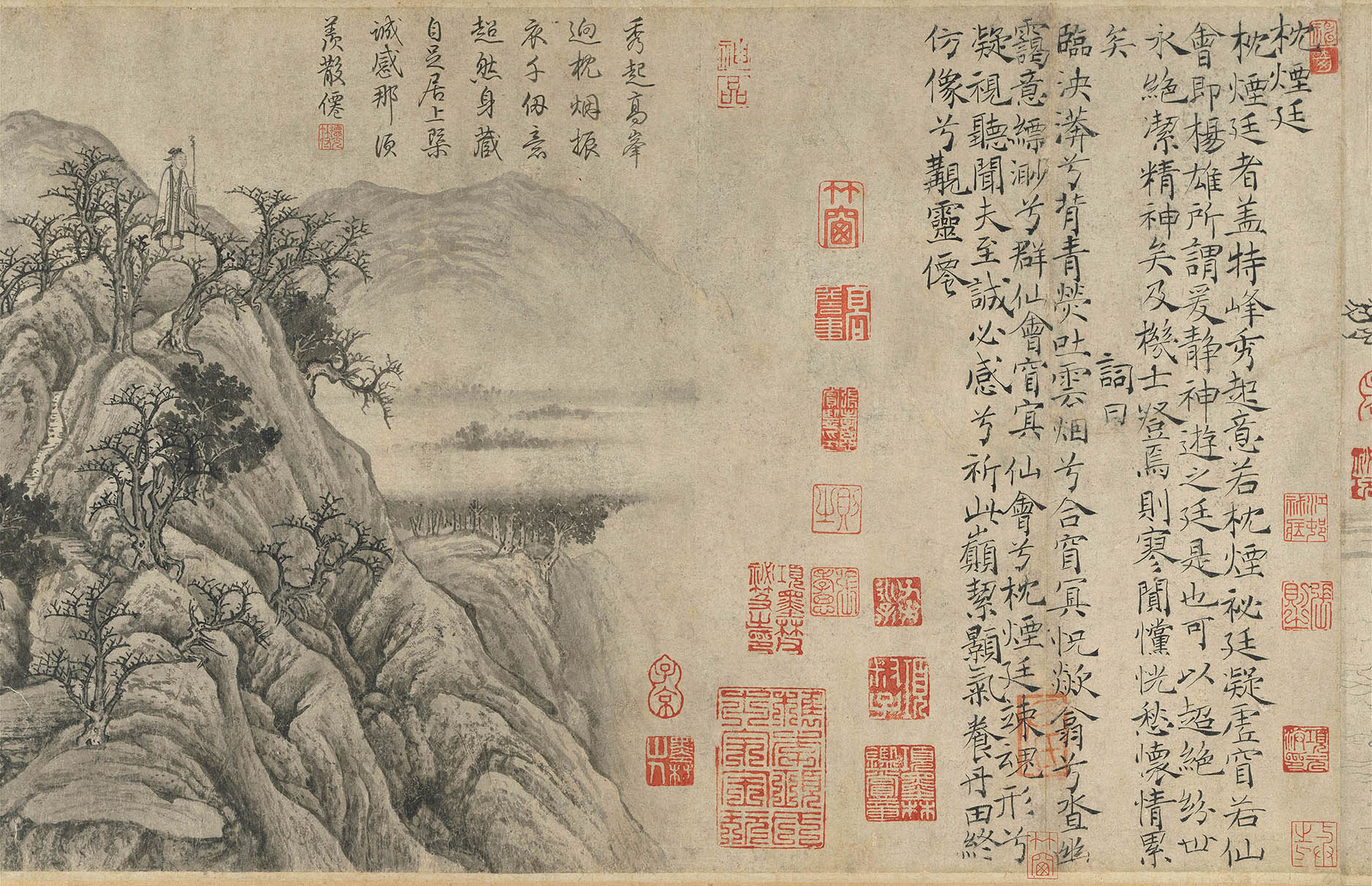

Viewing a Stele

Viewing a Stele

- Guo Xi (ca. 1023-after 1087), Song dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

Guo Xi, style name Chunfu, was a native of Wenxian in Henan. At the court, he became a Scholar of Arts in the Painting Academy during the Xining reign (1068-1077) of the Northern Song emperor Shenzong, excelling at landscapes and studying the painting methods of Li Cheng.

This hanging scroll shows a wintry forest and a level distance landscape with pines featuring gnarled branches. Two figures are seen standing next to a stele with four figures in the lower right, the attendant on a horse with a parasol having a highly expressive face. This scene probably represents the story of Cao Cao (155-220) and Yang Xiu (175-219) viewing the stele of Cao E. No seal or signature of the artist is found on the painting, but the "curled-cloud" and "crab-claw" painting methods led it to be attributed to Guo Xi. The brushwork, composition, and style, however, are all closer to those of artists active in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

This hanging scroll shows a wintry forest and a level distance landscape with pines featuring gnarled branches. Two figures are seen standing next to a stele with four figures in the lower right, the attendant on a horse with a parasol having a highly expressive face. This scene probably represents the story of Cao Cao (155-220) and Yang Xiu (175-219) viewing the stele of Cao E. No seal or signature of the artist is found on the painting, but the "curled-cloud" and "crab-claw" painting methods led it to be attributed to Guo Xi. The brushwork, composition, and style, however, are all closer to those of artists active in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

Minghuang's Summer Palace

Minghuang's Summer Palace

- Guo Zhongshu (?-977), Song dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

This painting employs a bird's-eye perspective to present an elaborate terraced palace compound surrounded by courtyards and hallways, creating a beautiful and spectacular scene. Combined with the distant mountains and foreground trees, it conveys an idea of misty scenery associated with immortals. Given to the artist Guo Zhongshu, the landscape forms as well as trees and rocks are actually more closely related to the style of Li Cheng and Guo Xi as practiced in the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368). The dense "baimiao" style of linear ink strokes is exceptionally refined, and the "ruled lines" are all even and symmetrically arranged. The architectural structure, however, is more simplified and slightly formulaic. The composition and size of this painting are comparable to Li Rongjin's (fl. 13th-14th c.) "The Han Palace" in the National Palace Museum, the only difference being the more varied arrangement of trees. Both probably derived from the same model.

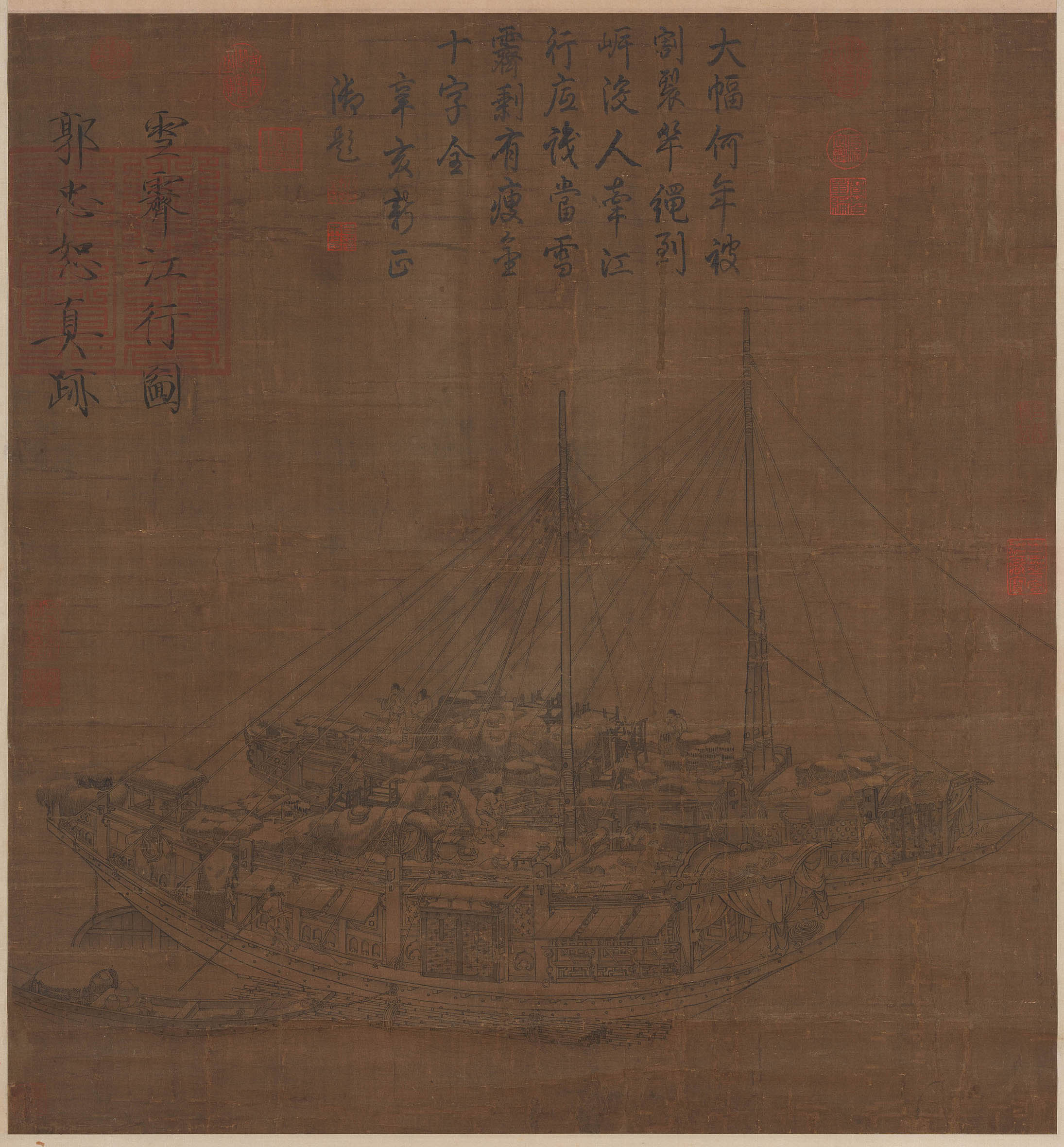

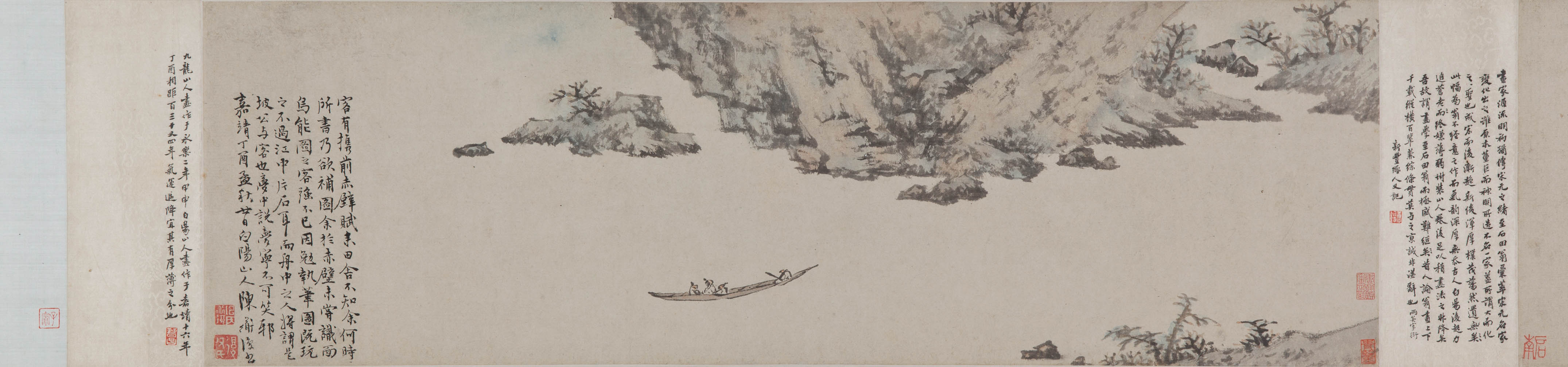

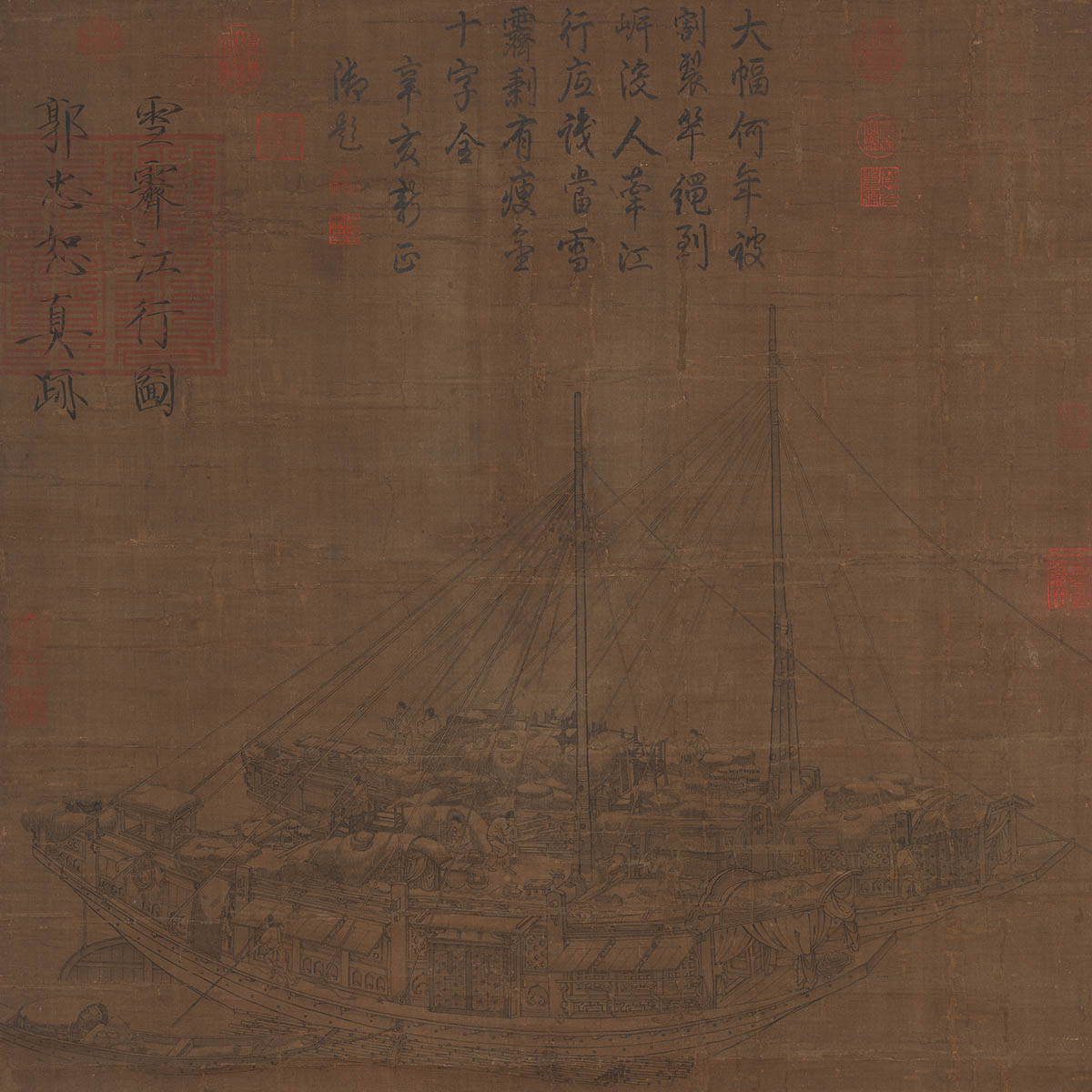

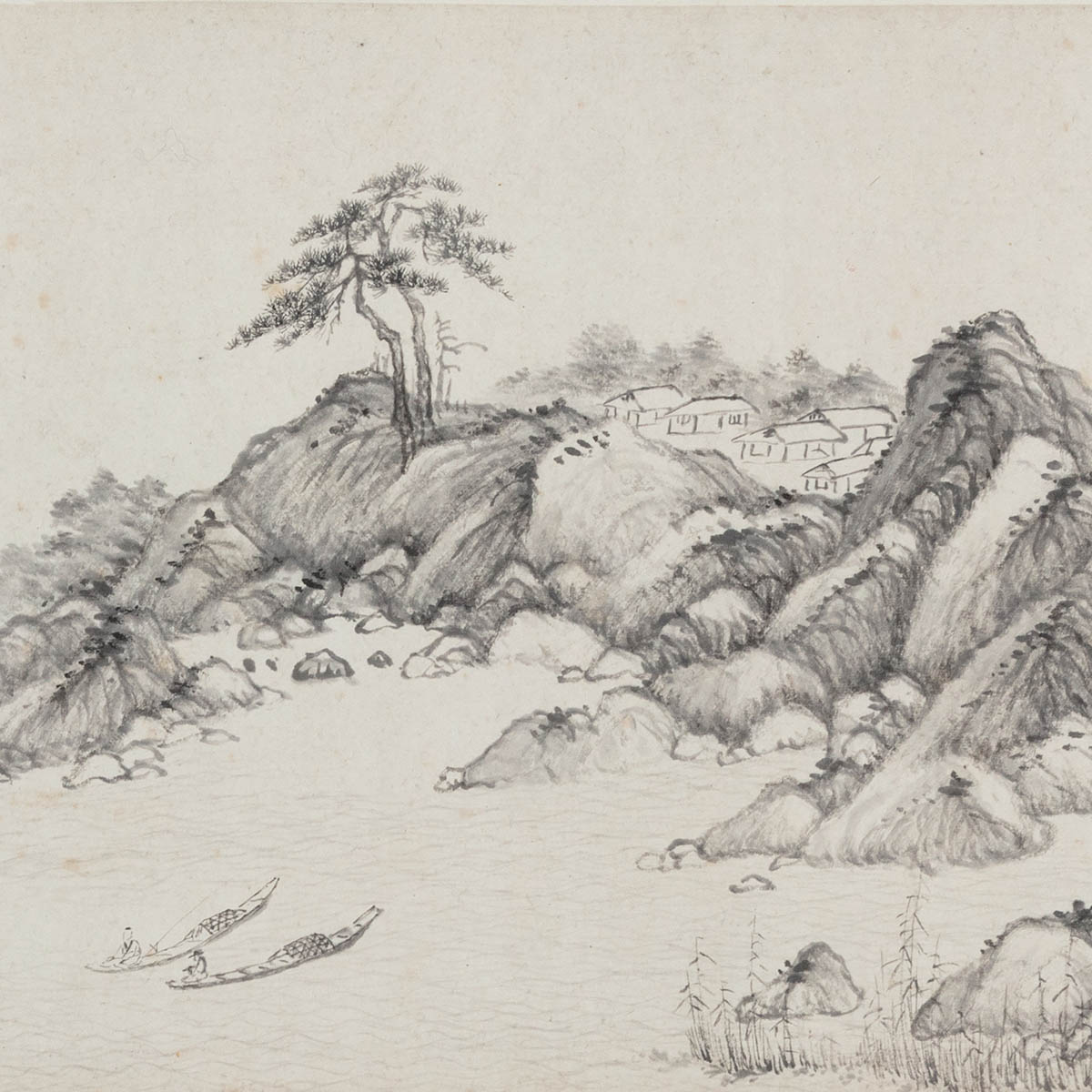

Traveling on a River After Snow

Traveling on a River After Snow

- Guo Zhongshu (?-977), Song dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in June 2013 as a National Treasure

Guo Zhongshu (style name Shuxian), a native of Luoyang in Henan, excelled at depicting landscapes and was especially gifted at painting multistory terraced buildings. His exacting method of "ruled-line" painting was precise but not stiff, and he was accurate in rendering relative size and proportions.

In this painting, two commercial ships are transporting grain on a canal in the Northern Song capital of Bianjing (modern Kaifeng). The cabin structure, rudder, and mast portions of the ships are delicately and accurately portrayed in a highly realistic style. This work had been cropped in the past, and a painting preserving the entire composition with the same title in Chinese is now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City (translated as "Towing Boats Under Clearing Skies After Snow"). The foreground of that work depicts a shoreline, and Professor Wai-Kam Ho has indicated that the method of depicting the rocks and trees is close to the style of Jin dynasty or Southern Song painting.

In this painting, two commercial ships are transporting grain on a canal in the Northern Song capital of Bianjing (modern Kaifeng). The cabin structure, rudder, and mast portions of the ships are delicately and accurately portrayed in a highly realistic style. This work had been cropped in the past, and a painting preserving the entire composition with the same title in Chinese is now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City (translated as "Towing Boats Under Clearing Skies After Snow"). The foreground of that work depicts a shoreline, and Professor Wai-Kam Ho has indicated that the method of depicting the rocks and trees is close to the style of Jin dynasty or Southern Song painting.

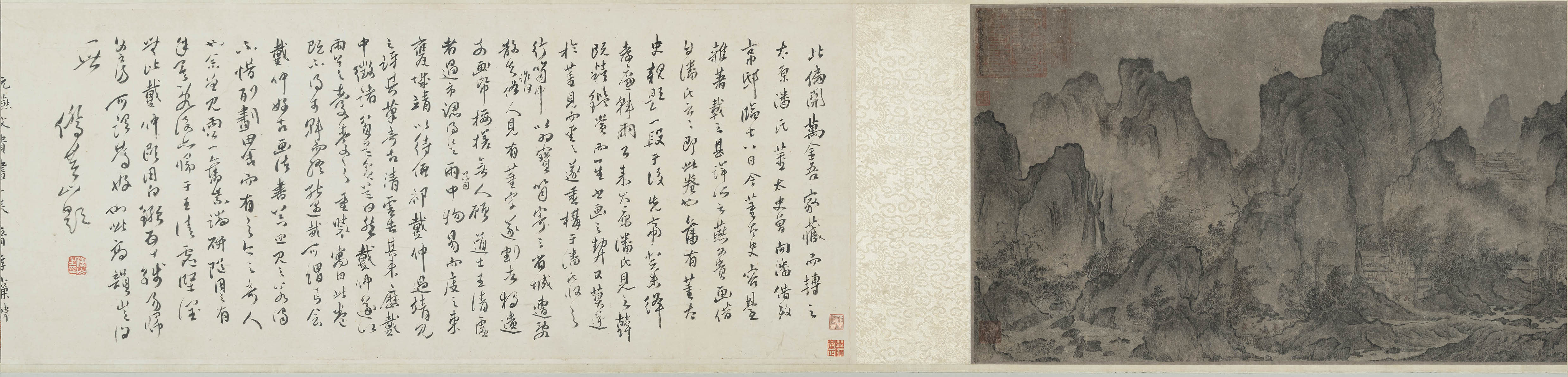

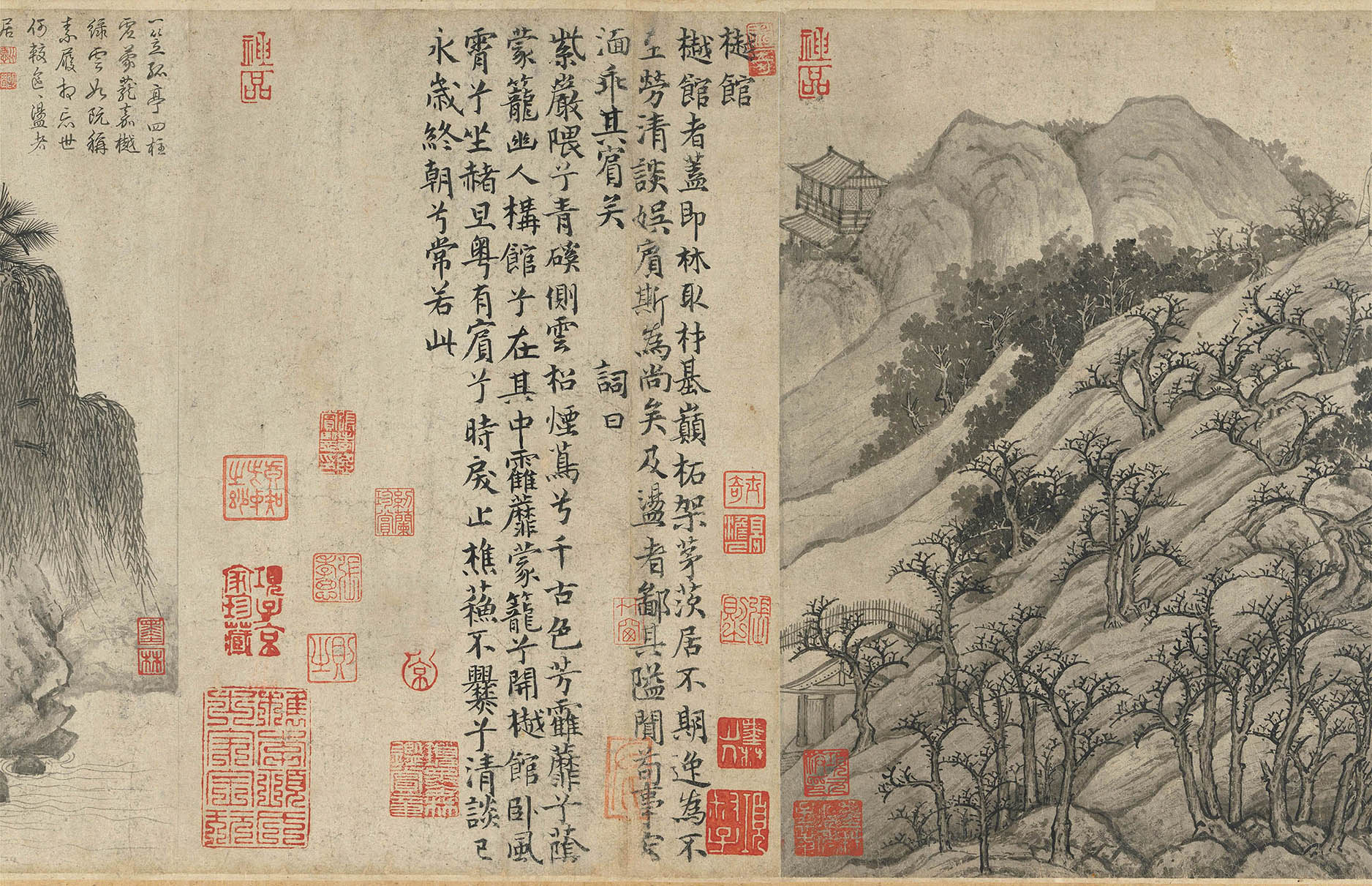

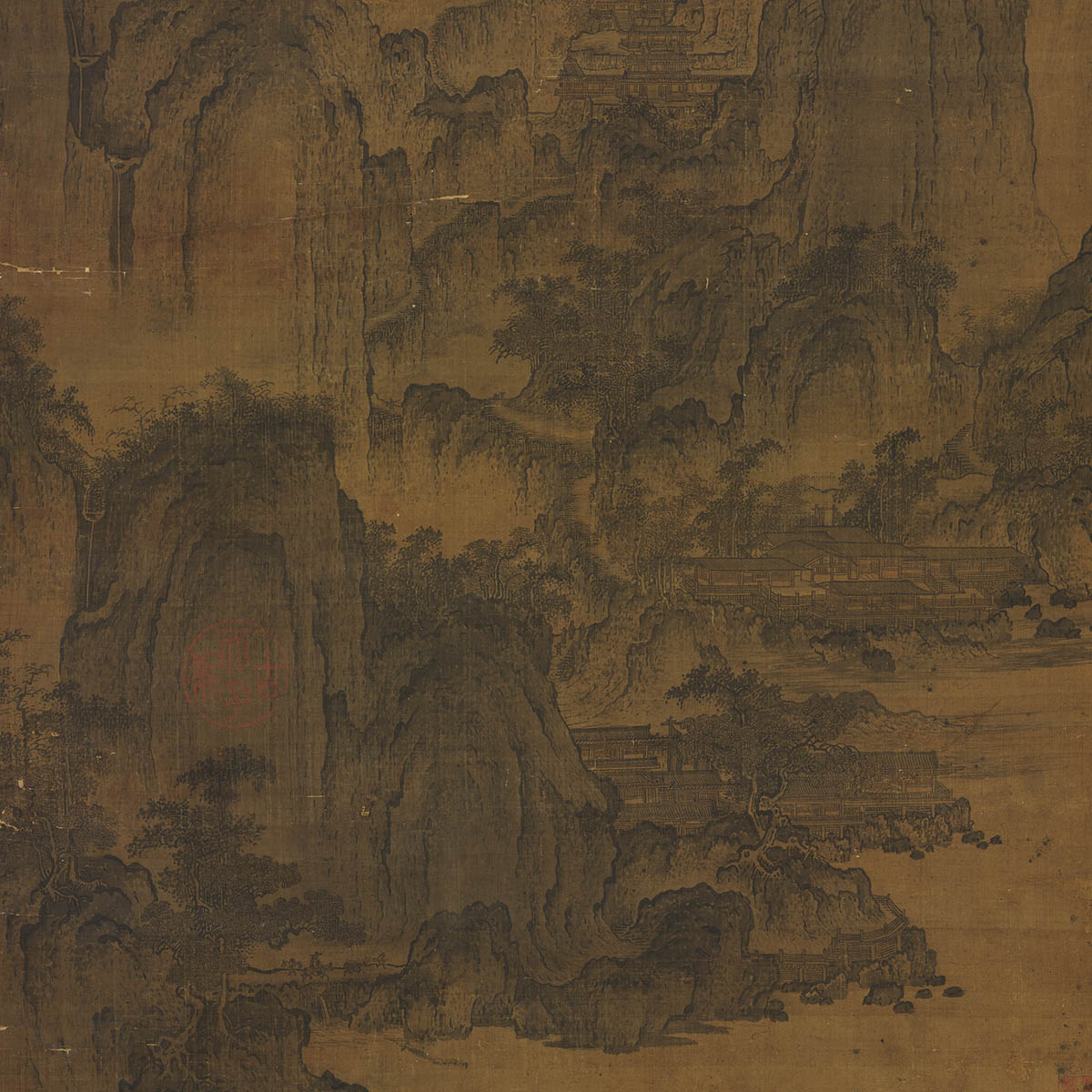

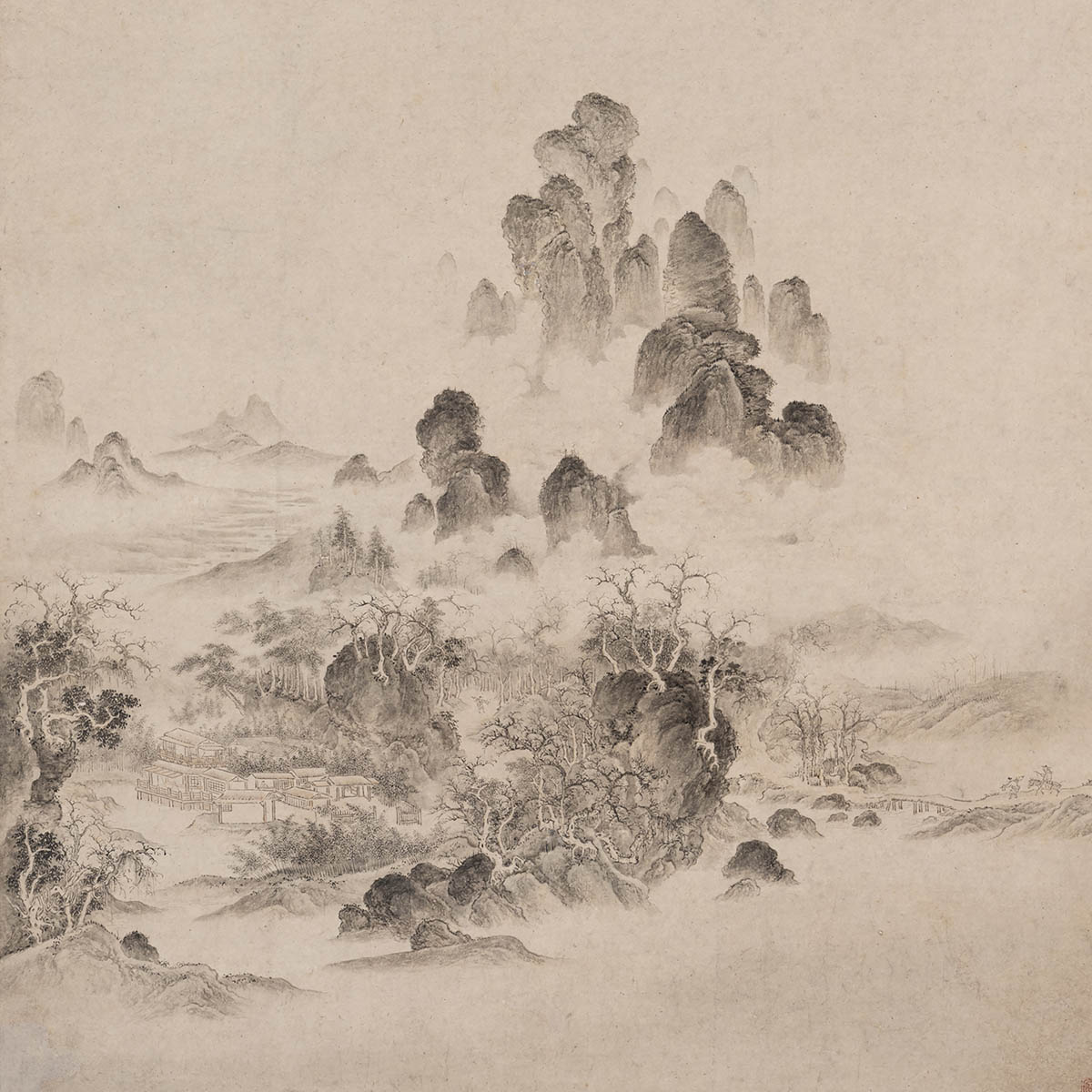

Pavilions Among Mountains and Rivers

Pavilions Among Mountains and Rivers

- Yan Wengui (fl. latter half of the 10th-first half of the 11th c.), Song dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

In landscape painting, Yan Wengui often employed massive ridges and layered peaks to create compositions that appear pure and refined.

At the beginning of this handscroll to the right are river banks and sandy shoals. Various trees verdant in leaf are with buildings scattered throughout the scenery. Winding from the middle, hills extend into background peaks enshrouded in clouds and mists. Finally, at the end to the left are massive peaks and layered ridges with a winding mountain path; buildings and pavilions appear there in a richly detailed and wondrous arrangement. This work employs a handscroll format to render the complex spatial structure of level, high, and deep distances often found in Northern Song monumental hanging scroll landscapes. Exceptionally creative in terms of its ingenious composition, the brushwork is also delicate and compact, the scenery seemingly extending infinitely, yet intimate enough to invite the viewer into the scenery.

At the beginning of this handscroll to the right are river banks and sandy shoals. Various trees verdant in leaf are with buildings scattered throughout the scenery. Winding from the middle, hills extend into background peaks enshrouded in clouds and mists. Finally, at the end to the left are massive peaks and layered ridges with a winding mountain path; buildings and pavilions appear there in a richly detailed and wondrous arrangement. This work employs a handscroll format to render the complex spatial structure of level, high, and deep distances often found in Northern Song monumental hanging scroll landscapes. Exceptionally creative in terms of its ingenious composition, the brushwork is also delicate and compact, the scenery seemingly extending infinitely, yet intimate enough to invite the viewer into the scenery.

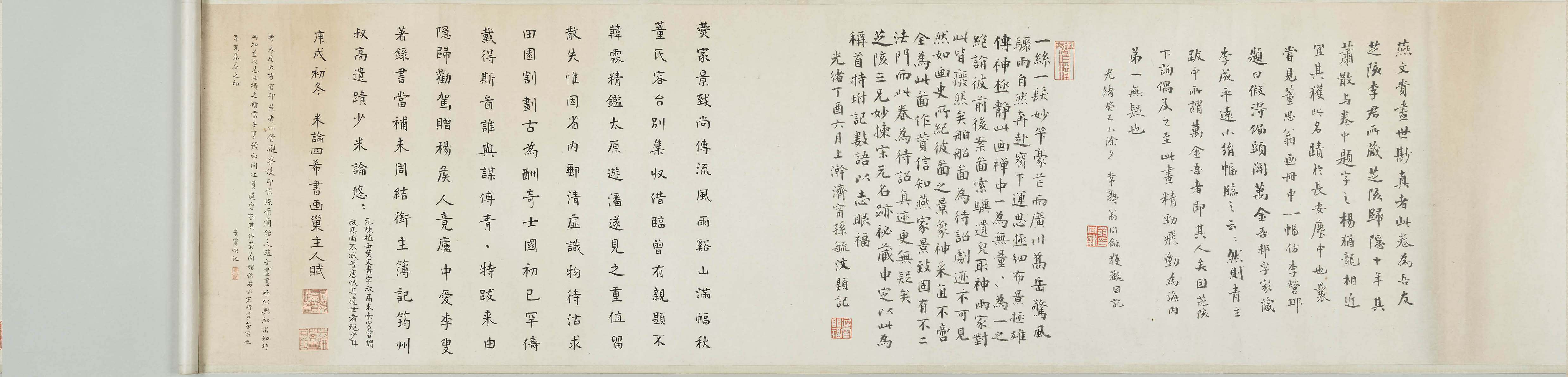

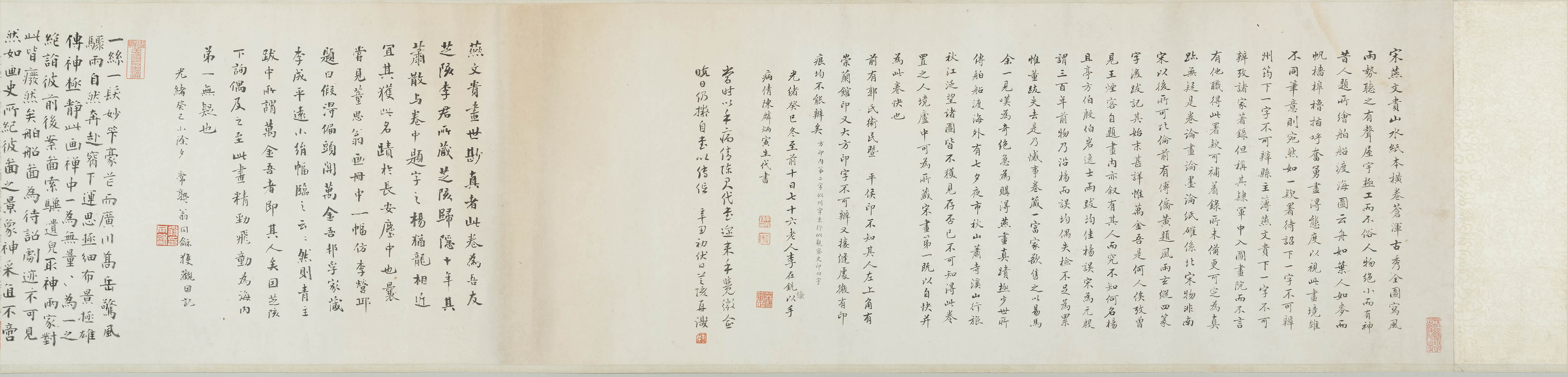

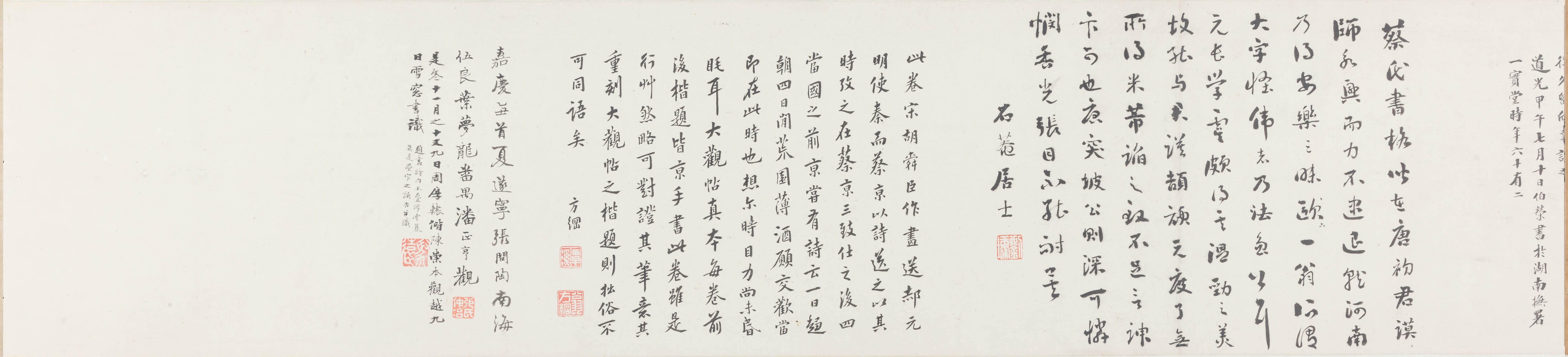

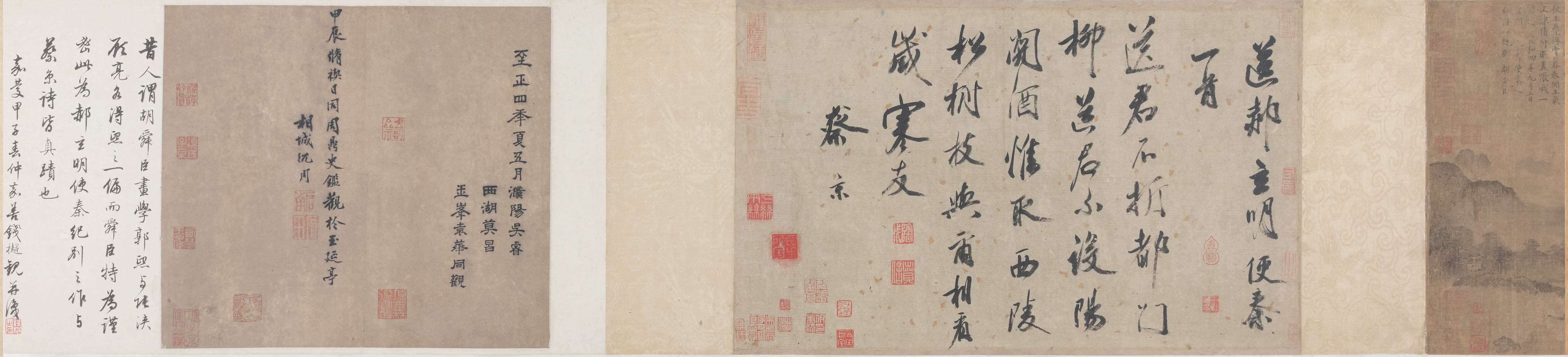

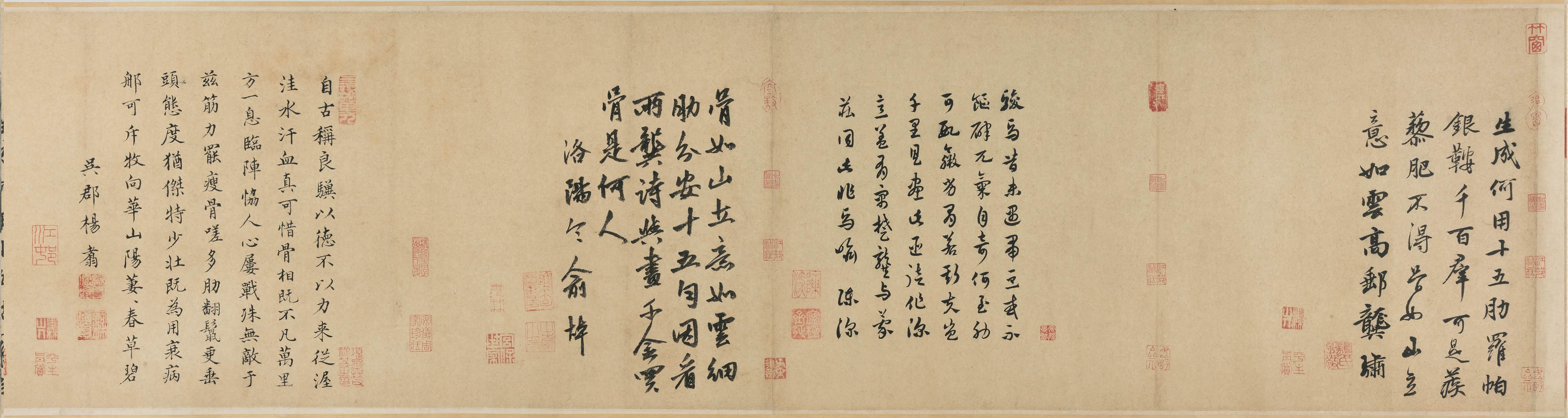

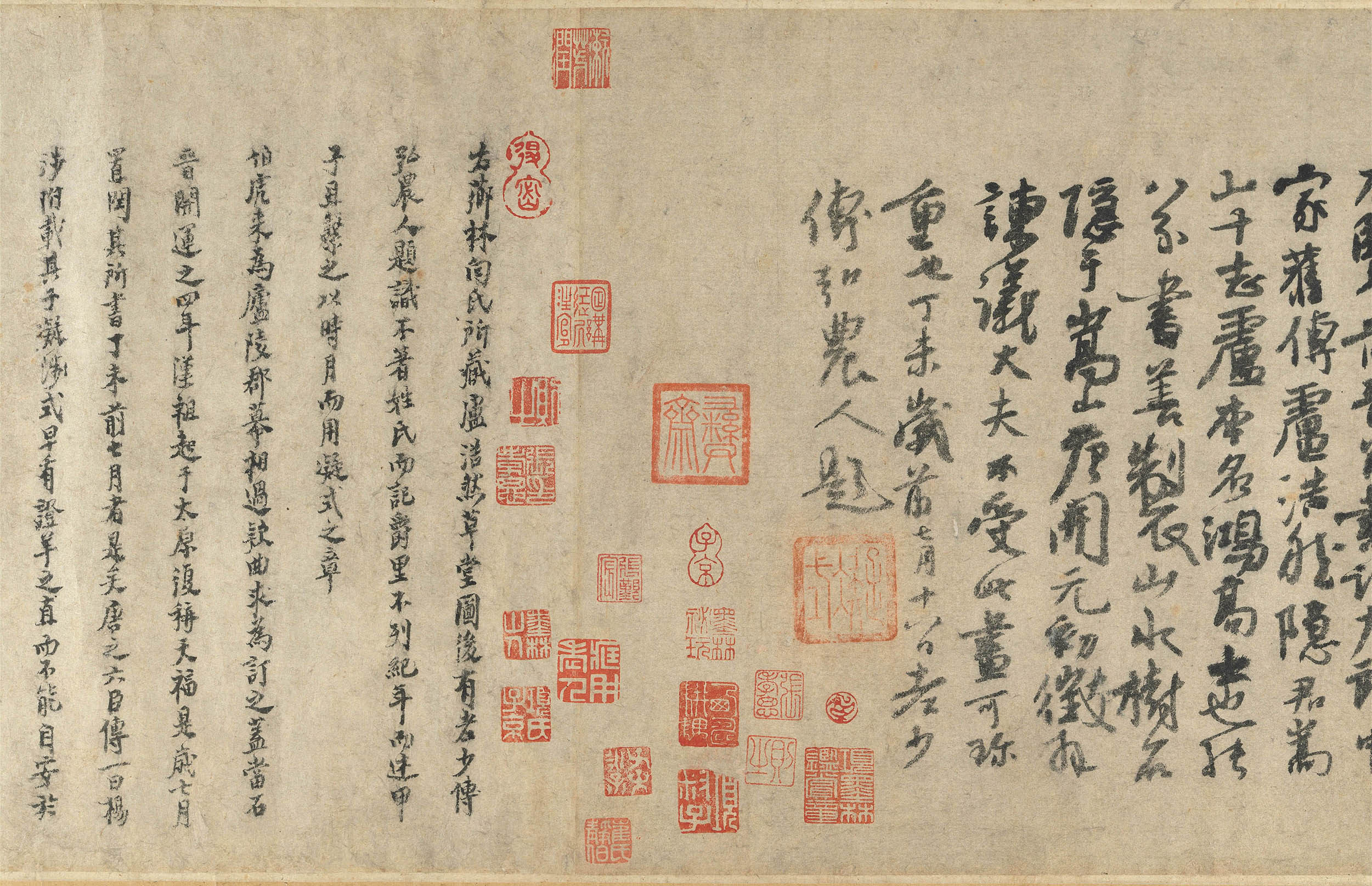

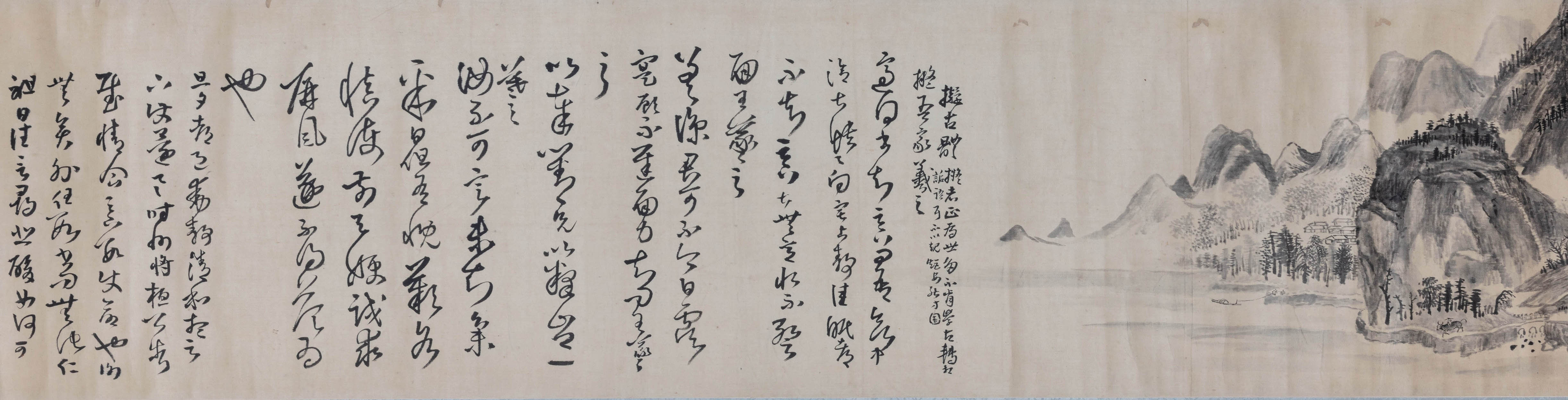

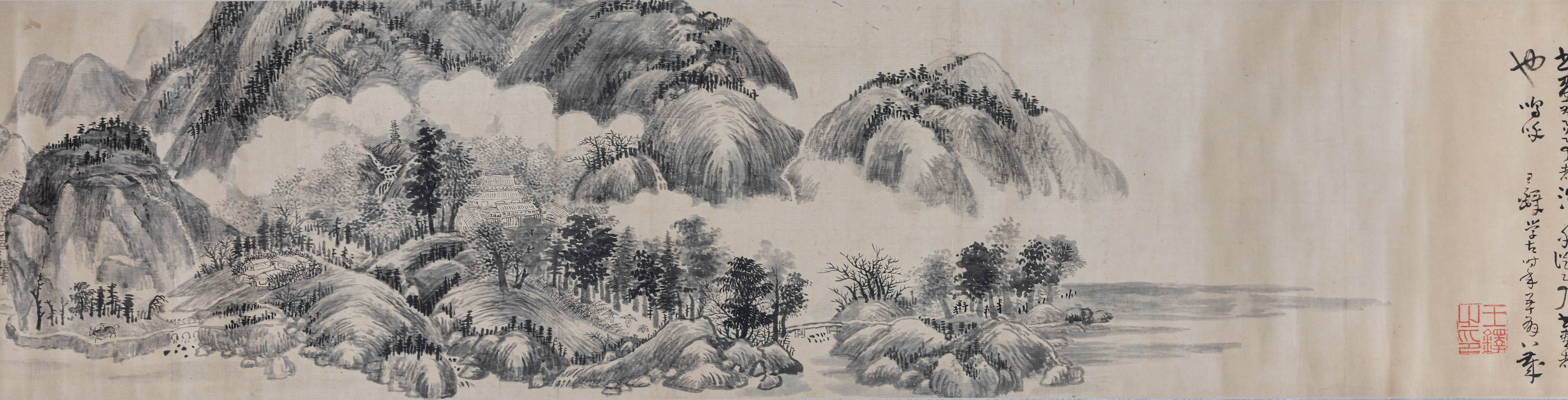

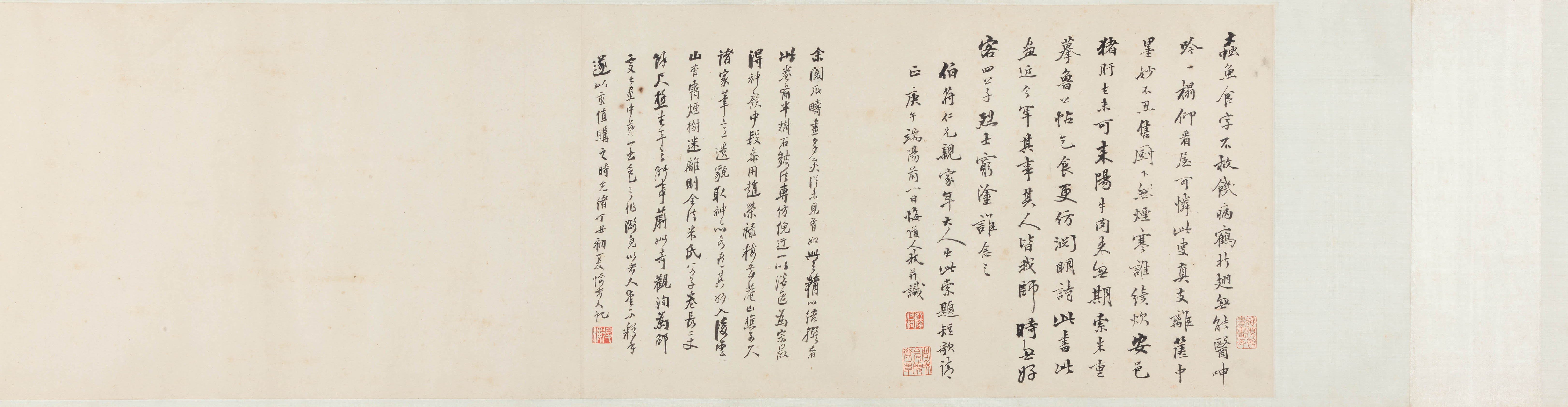

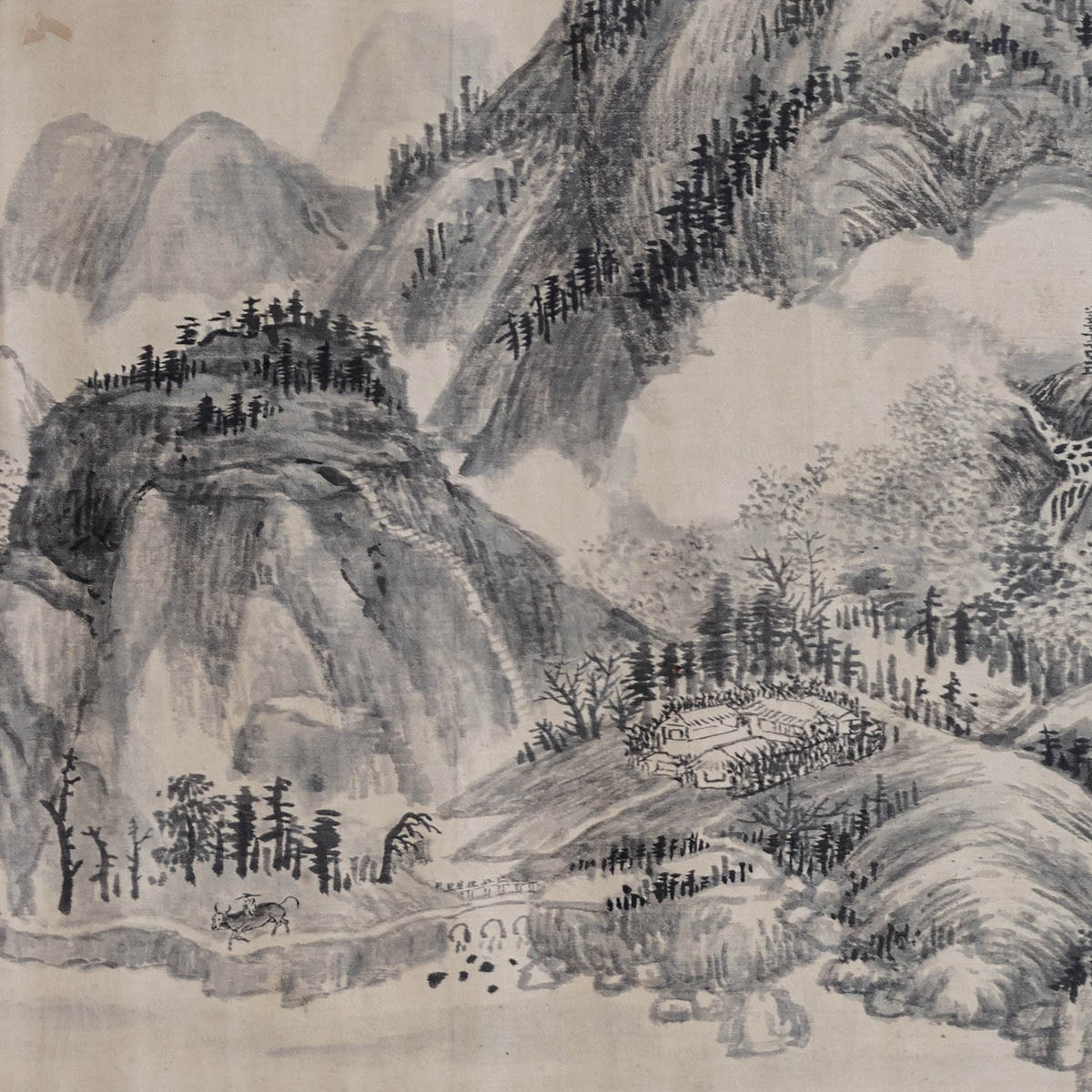

Painting and Calligraphy for Hao Xuanming Upon His Dispatch to Qin

Painting and Calligraphy for Hao Xuanming Upon His Dispatch to Qin

- Yan Wengui (fl. latter half of the 10th-first half of the 11th c.), Song dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

- Provisionally classified by the National Palace Museum as a Significant Historical Artifact

Yan Wengui, an early Song artist active in the Painting Academy, often carefully arranged ridges and peaks in his landscape paintings in a pure and refined manner.

This painting depicts mountains by a river with flying cascades off to the left. Ridges and peaks soar upwards with buildings placed discreetly among them. The outlines of the mountains are rendered using coarse and trembling lines filled with a texturing method similar to raindrops, giving the earthen faces a tactile and weighty appearance despite the delicate brushwork. Other brush lines are rounded and supple, which differ from the strong and angular brushwork associated with Yan Wengui's style. Although the signature, "From the brush of the Hanlin Painter-in-Attendance Yan Wengui," appears on the rock face to the left, the lines are slightly thin and weak, suggesting a derivation of Yan's style from the 12th or 13th century instead.

This painting depicts mountains by a river with flying cascades off to the left. Ridges and peaks soar upwards with buildings placed discreetly among them. The outlines of the mountains are rendered using coarse and trembling lines filled with a texturing method similar to raindrops, giving the earthen faces a tactile and weighty appearance despite the delicate brushwork. Other brush lines are rounded and supple, which differ from the strong and angular brushwork associated with Yan Wengui's style. Although the signature, "From the brush of the Hanlin Painter-in-Attendance Yan Wengui," appears on the rock face to the left, the lines are slightly thin and weak, suggesting a derivation of Yan's style from the 12th or 13th century instead.

Painting and Calligraphy for Hao Xuanming Upon His Dispatch to Qin

Painting and Calligraphy for Hao Xuanming Upon His Dispatch to Qin

- Hu Shunchen and Cai Jing (1047-1126), Song dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Hu Shunchen did this painting as a farewell gift for the Song court emissary Hao Xuanming and also wrote the following inscription on the scroll to the left: "On the second day of the ninth month of the fourth Xuanhe year (1122), Emissary Xuanming received orders for dispatch to Qin, and I have done this to bid him farewell. Hao Xuanming." The inscription also features an impression in intaglio of his seal "Shunchen." Appearing after the painting is a poem calligraphed by the prominent political figure Cai Jing.

A record from Precious Mirror of Painting by Xia Wenyan (1365 preface) in the Yuan dynasty states that Hu Shunchen was a student of Guo Xi and practiced a "dense" painting style. The figures and landscape elements throughout this scroll are done with concentrated brushwork that conveys much of this artistic idea. The coloring, texture, and washes are all well controlled, indicating that he indeed studied Guo Xi's style, representing a style of landscape painting from the late Northern Song.

A record from Precious Mirror of Painting by Xia Wenyan (1365 preface) in the Yuan dynasty states that Hu Shunchen was a student of Guo Xi and practiced a "dense" painting style. The figures and landscape elements throughout this scroll are done with concentrated brushwork that conveys much of this artistic idea. The coloring, texture, and washes are all well controlled, indicating that he indeed studied Guo Xi's style, representing a style of landscape painting from the late Northern Song.

Fishing Boat on an Autumn River

Fishing Boat on an Autumn River

- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

This painting portrays a refined scene of mountains and a river in autumn. Tall trees rise from the riverbanks and large rocks appear there, the leaves having started to turn red and interspersed with craggy bare branches that look like crab claws. A fishing boat plies the water, the flat surface of which contrasts with the lofty and majestic mountains rising above but at the same time creates the leisurely atmosphere of a scholar-fisherman angling at ease. The cliffs shift side to side as they recede to create the effect of an expansive distance. The strong black ink outlines of the rocks, the mountain forms in light ink that they form, the enveloping mists, and the expressive effects of the mountaintops indicate this work fuses several styles associated with the Five Dynasties and Northern Song period.

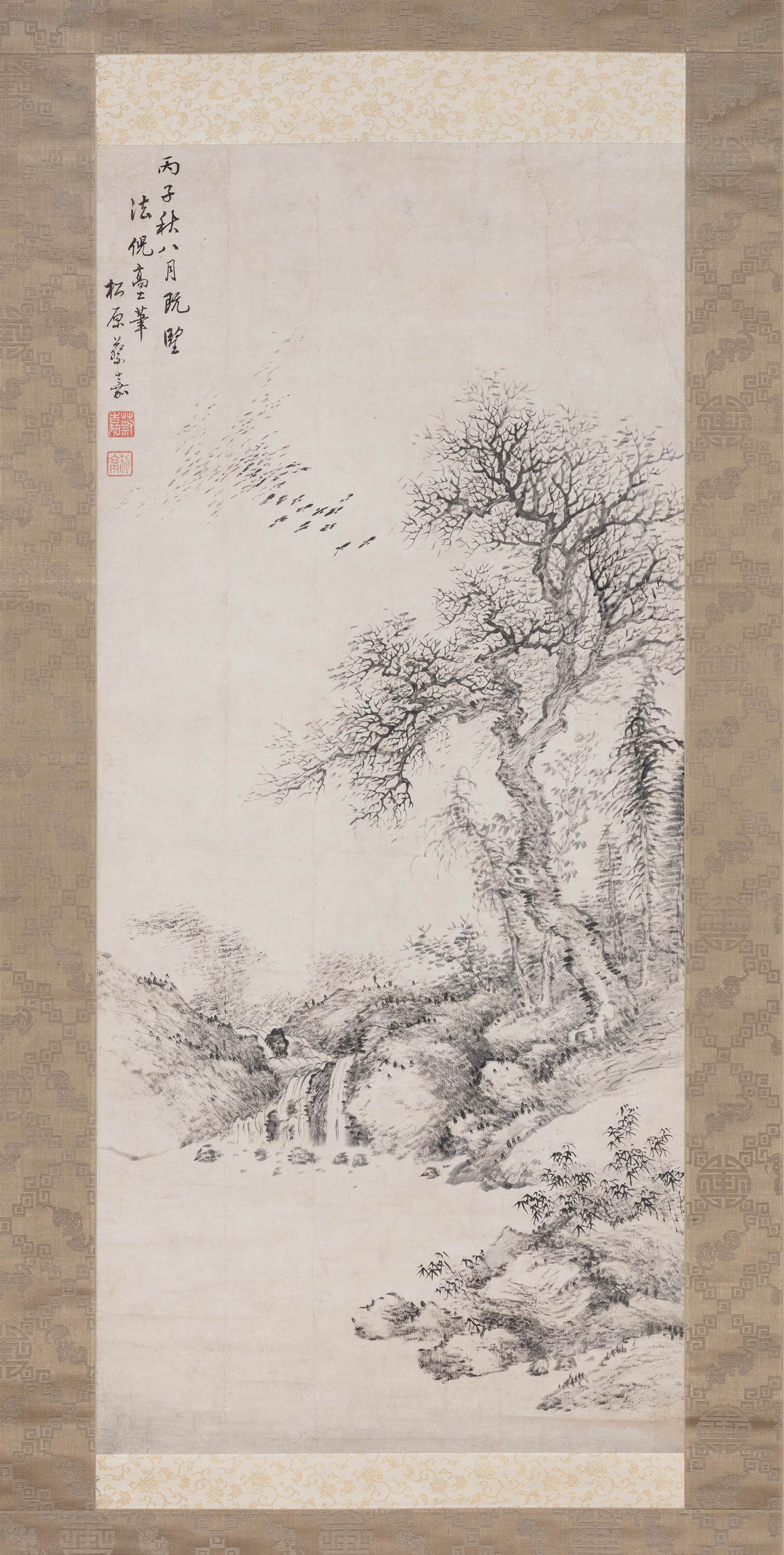

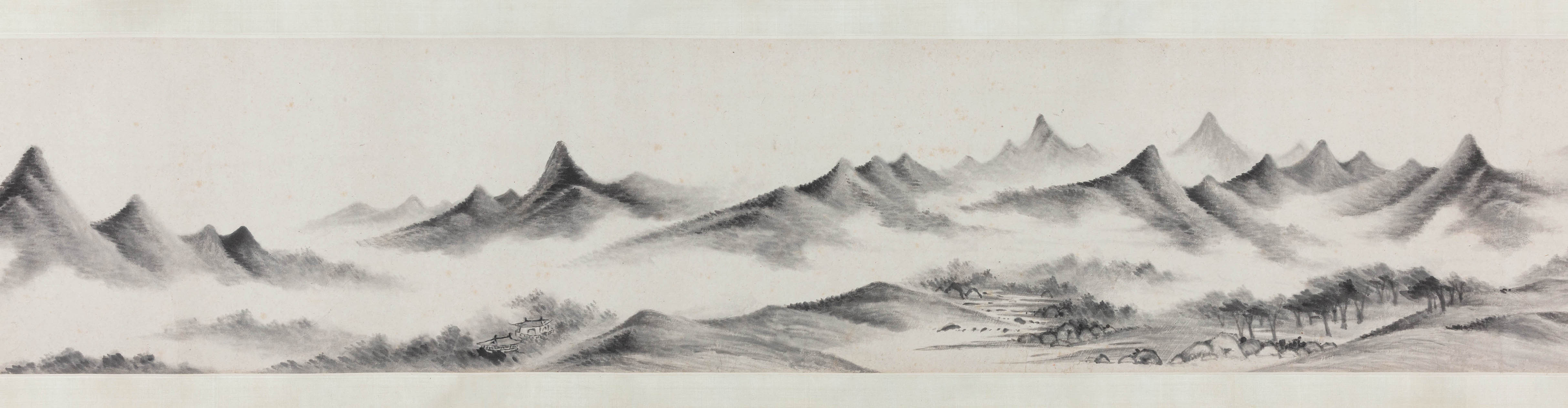

Waiting for the Ferry by a Wintry Grove

Waiting for the Ferry by a Wintry Grove

- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

Landscape paintings on the theme of wintry trees were very popular in North China during the Five Dynasties and Northern Song period. In particular, Li Cheng (919-967) and the subject of "wintry trees and a level distance" that he created were most representative of it.

This painting portrays a desolate rustic scene with travelers and a ferry. The washes of ink highlight a sense of frigid cold against the frosty sky to suggest hues of snow. The reduced size of the trees in the foreground and the heightened vantage point transfer the focus of the painting back to the plains beyond and the action of travelers in the remote expanse of the background. Judging from the brush texturing and ink washes for the rocks and trees as well as the composition, this is probably a work from the Southern Song period (1127-1279) influenced by the school of Li Cheng and Guo Xi.

This painting portrays a desolate rustic scene with travelers and a ferry. The washes of ink highlight a sense of frigid cold against the frosty sky to suggest hues of snow. The reduced size of the trees in the foreground and the heightened vantage point transfer the focus of the painting back to the plains beyond and the action of travelers in the remote expanse of the background. Judging from the brush texturing and ink washes for the rocks and trees as well as the composition, this is probably a work from the Southern Song period (1127-1279) influenced by the school of Li Cheng and Guo Xi.

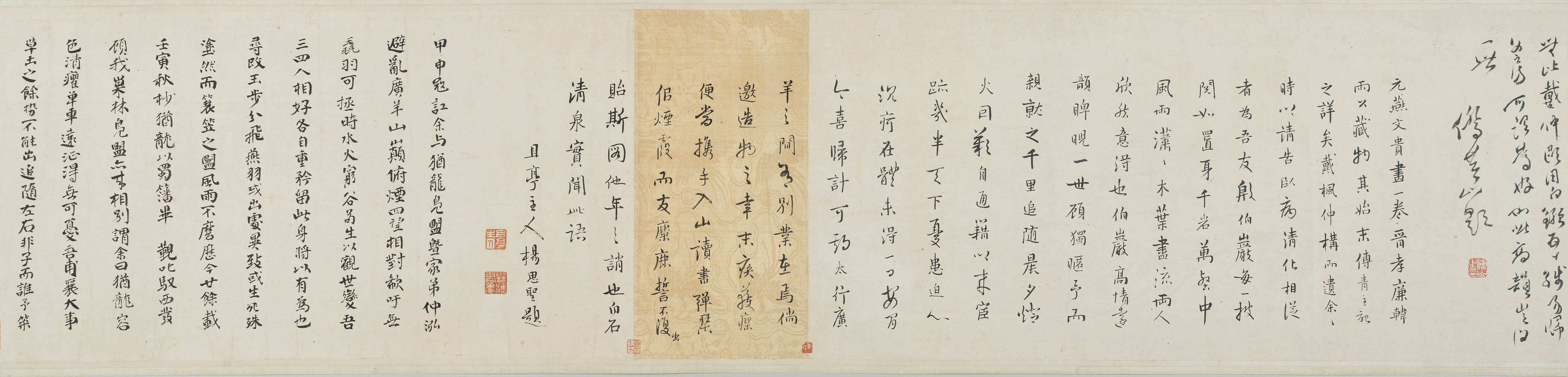

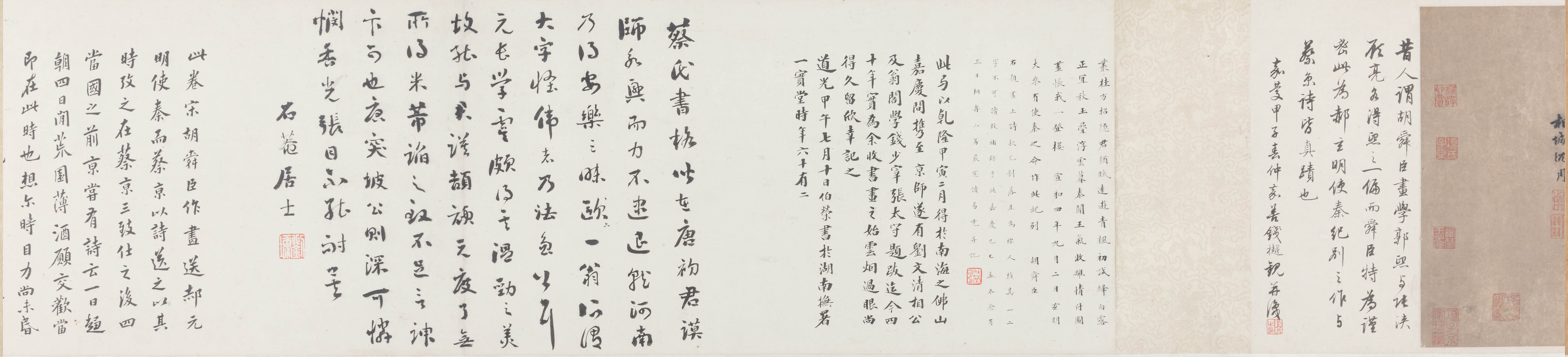

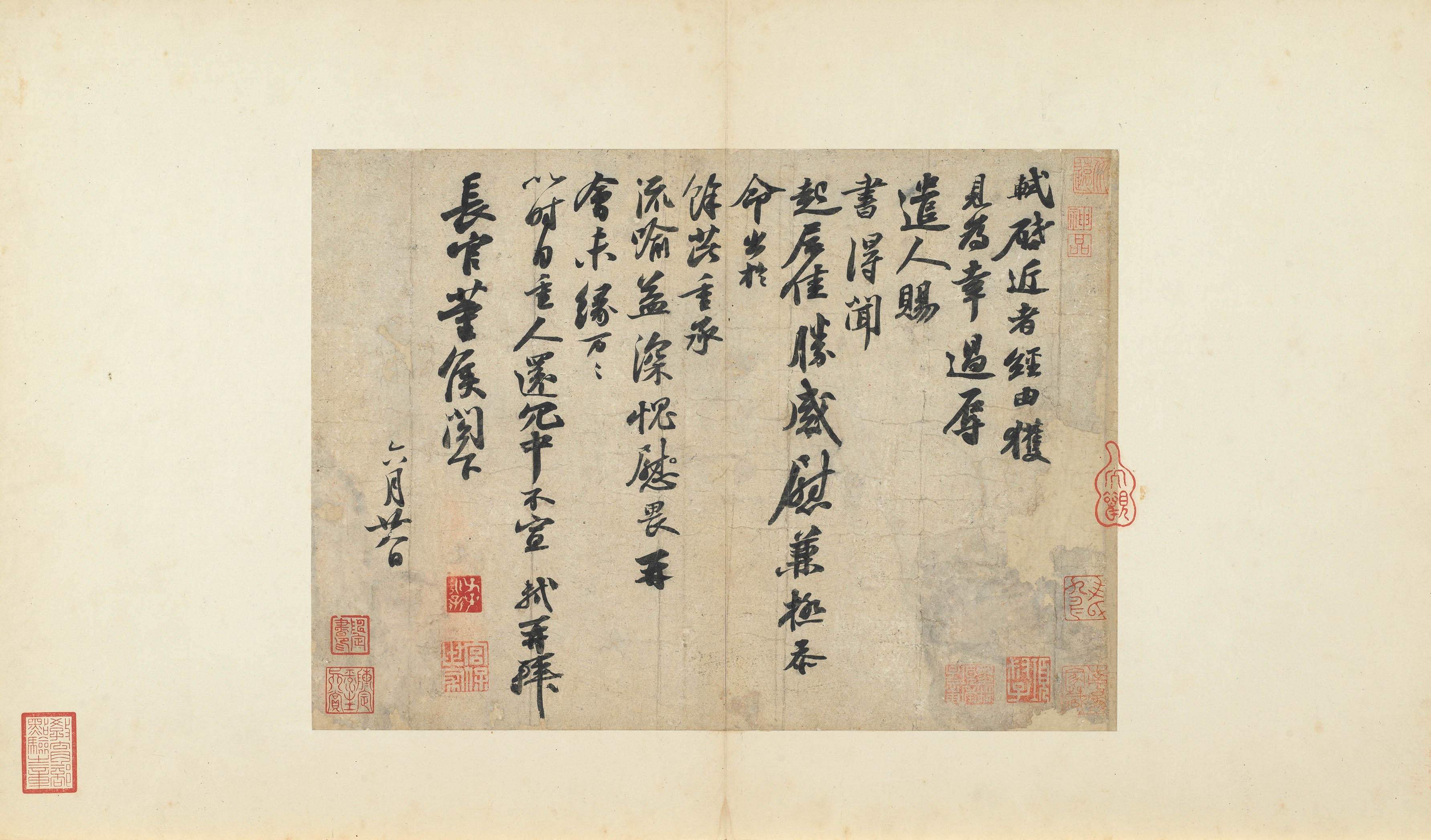

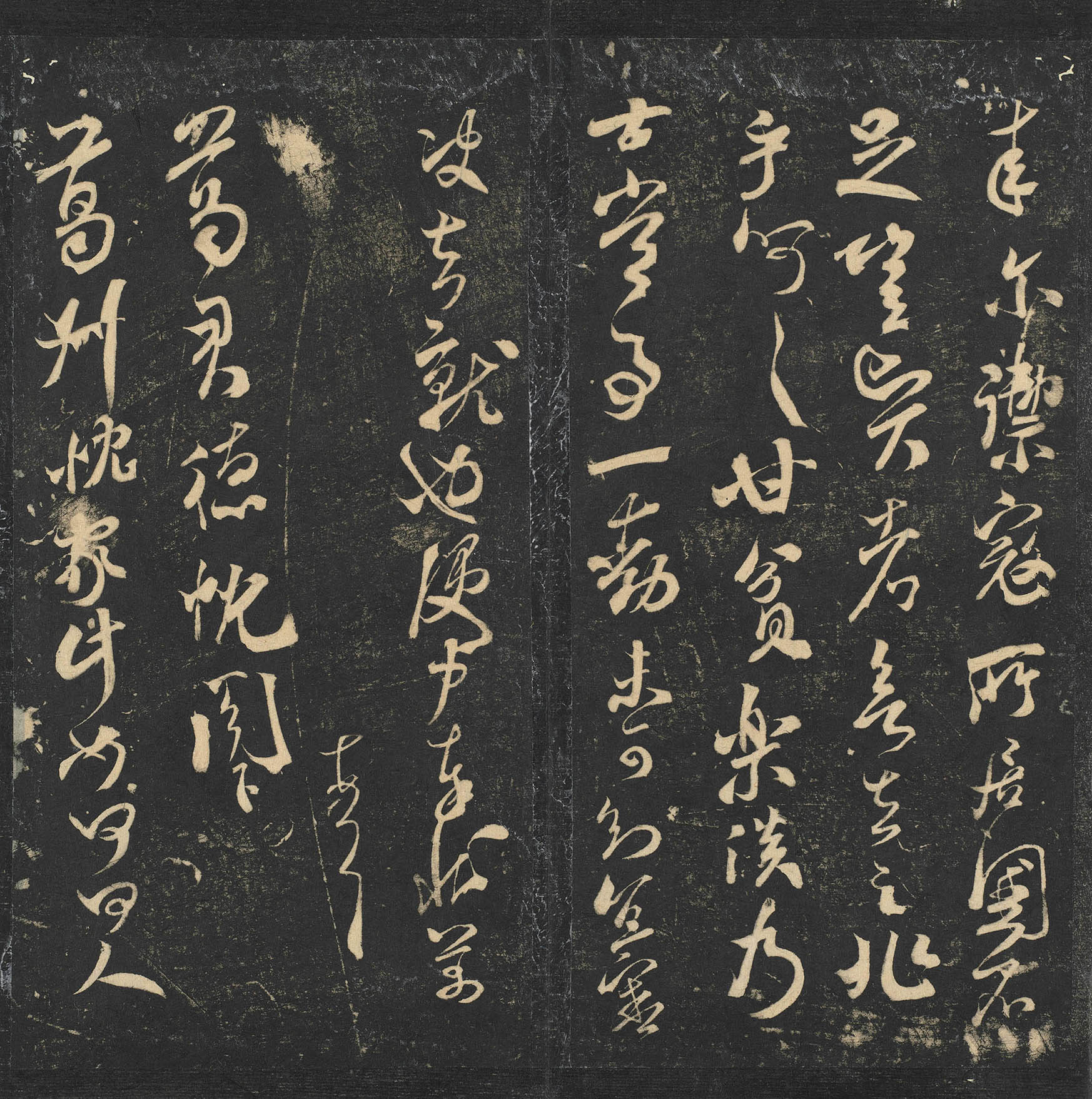

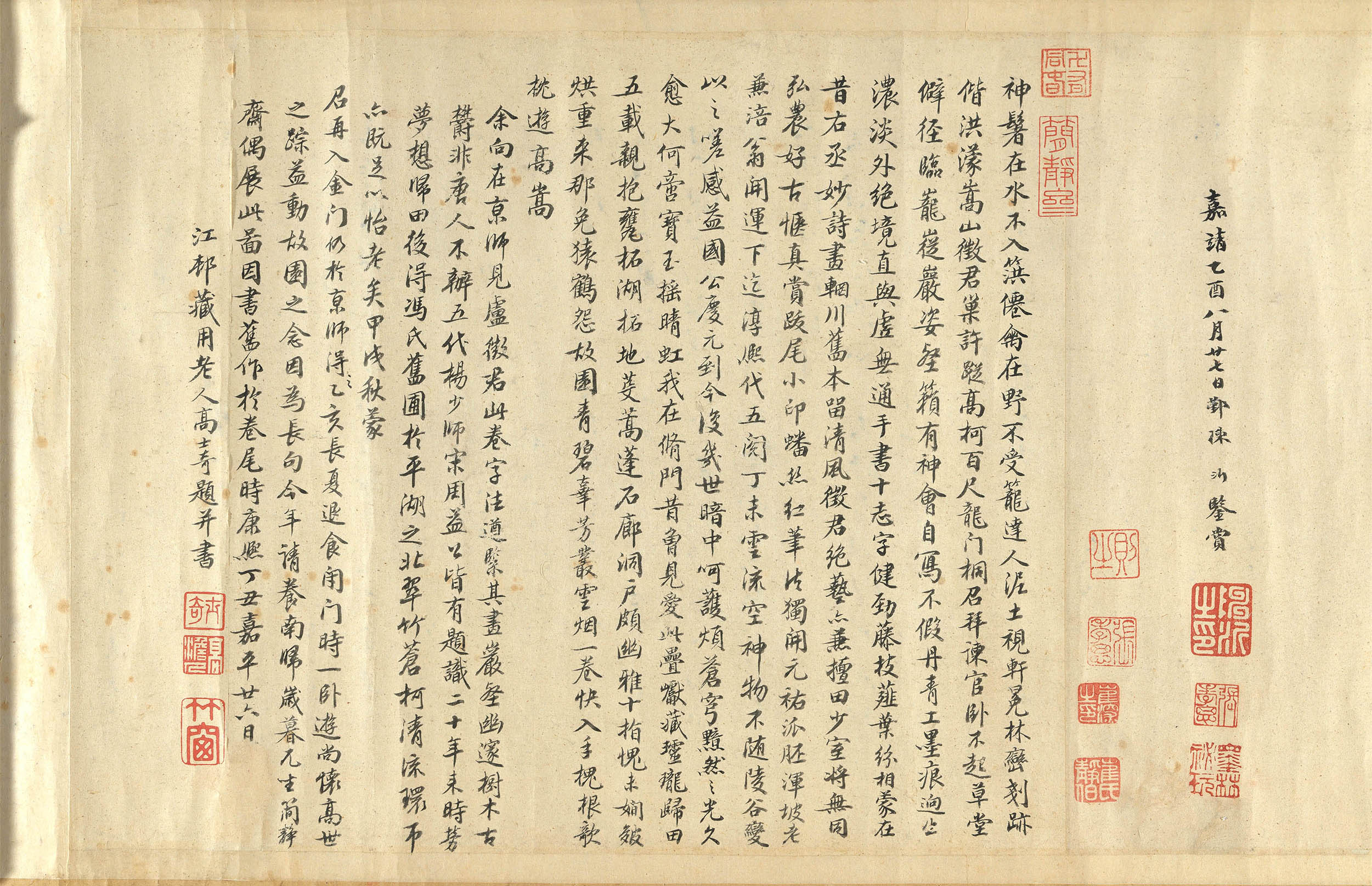

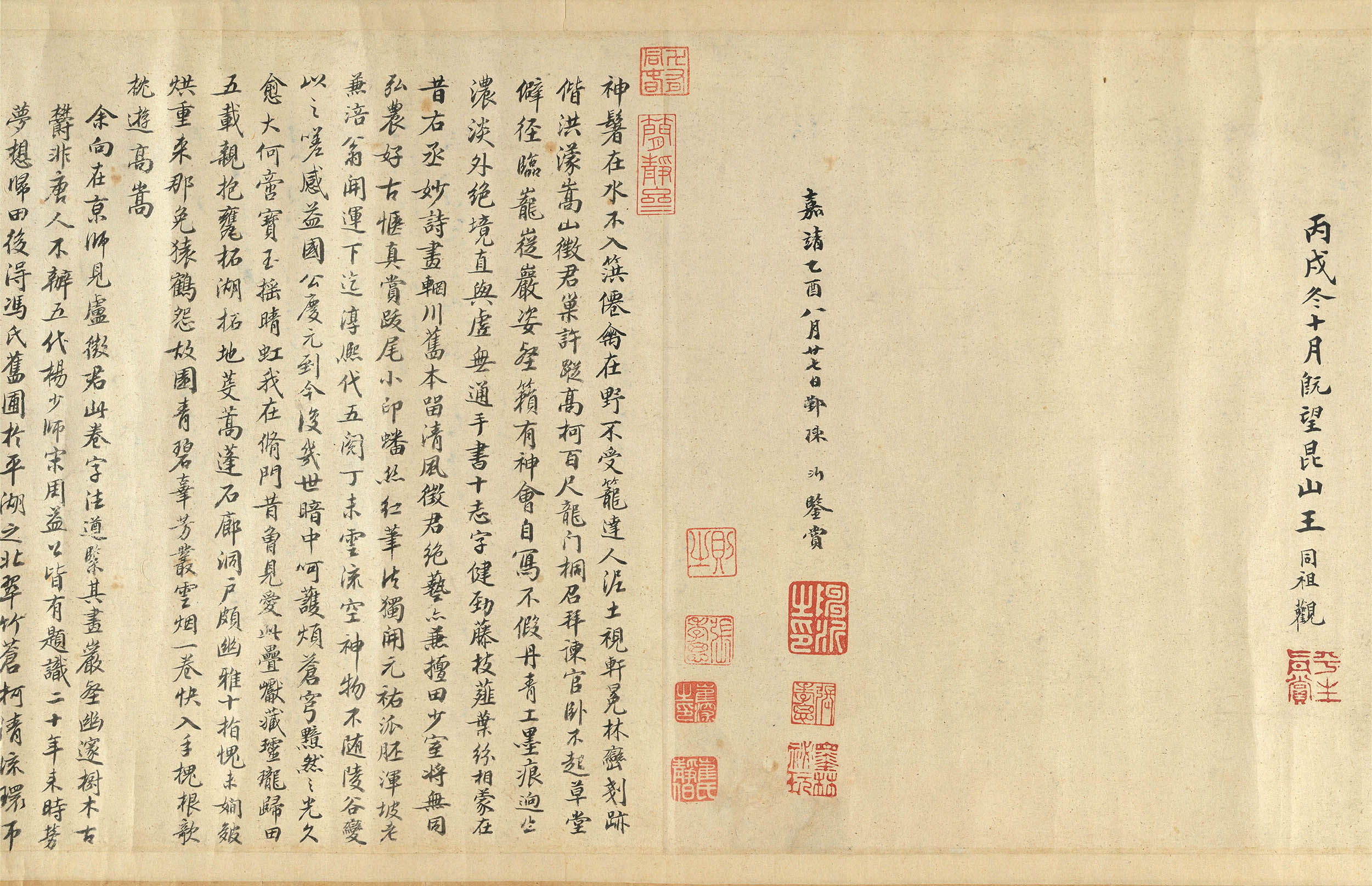

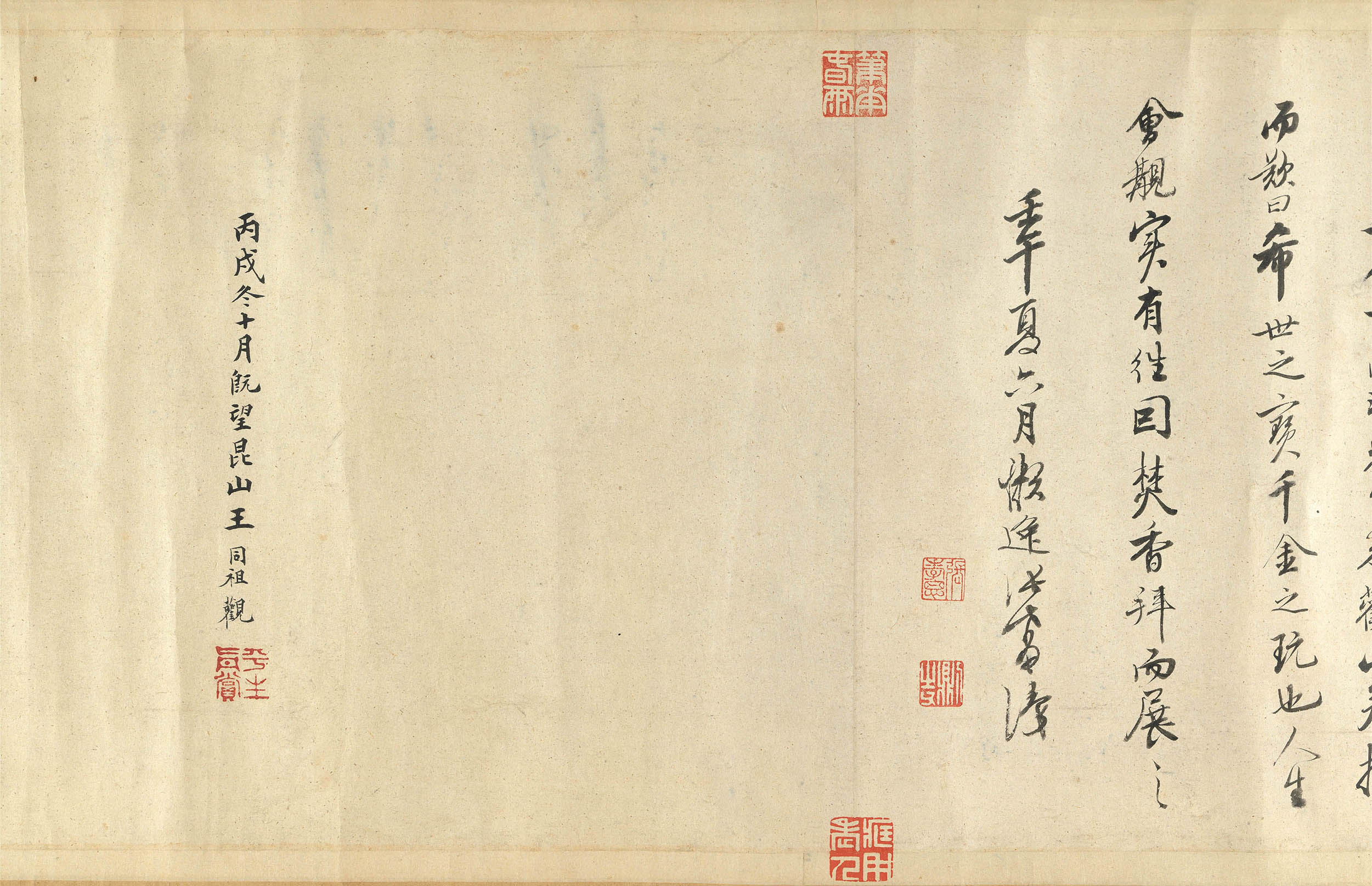

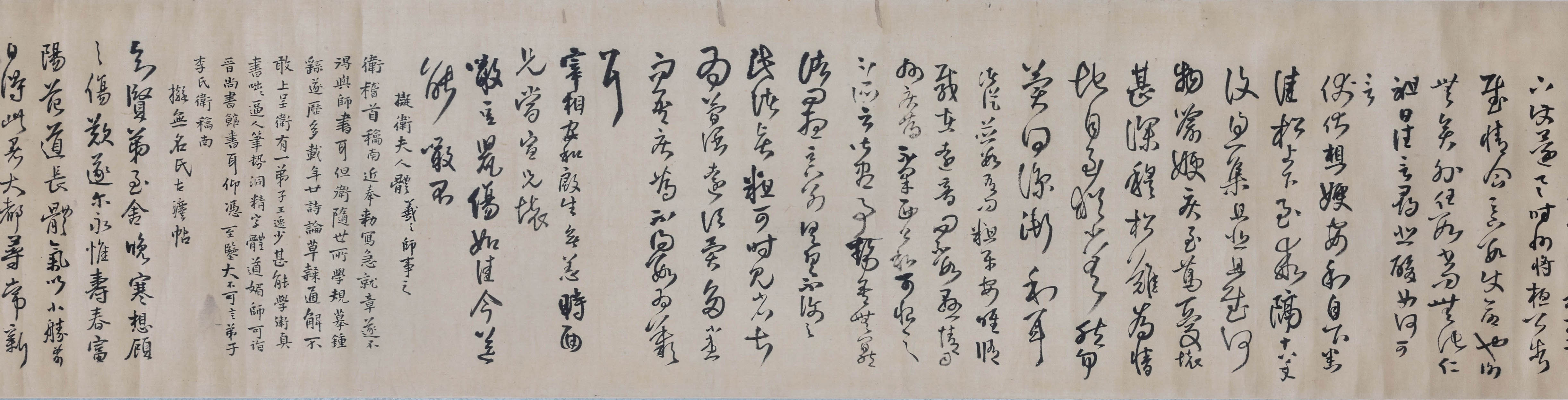

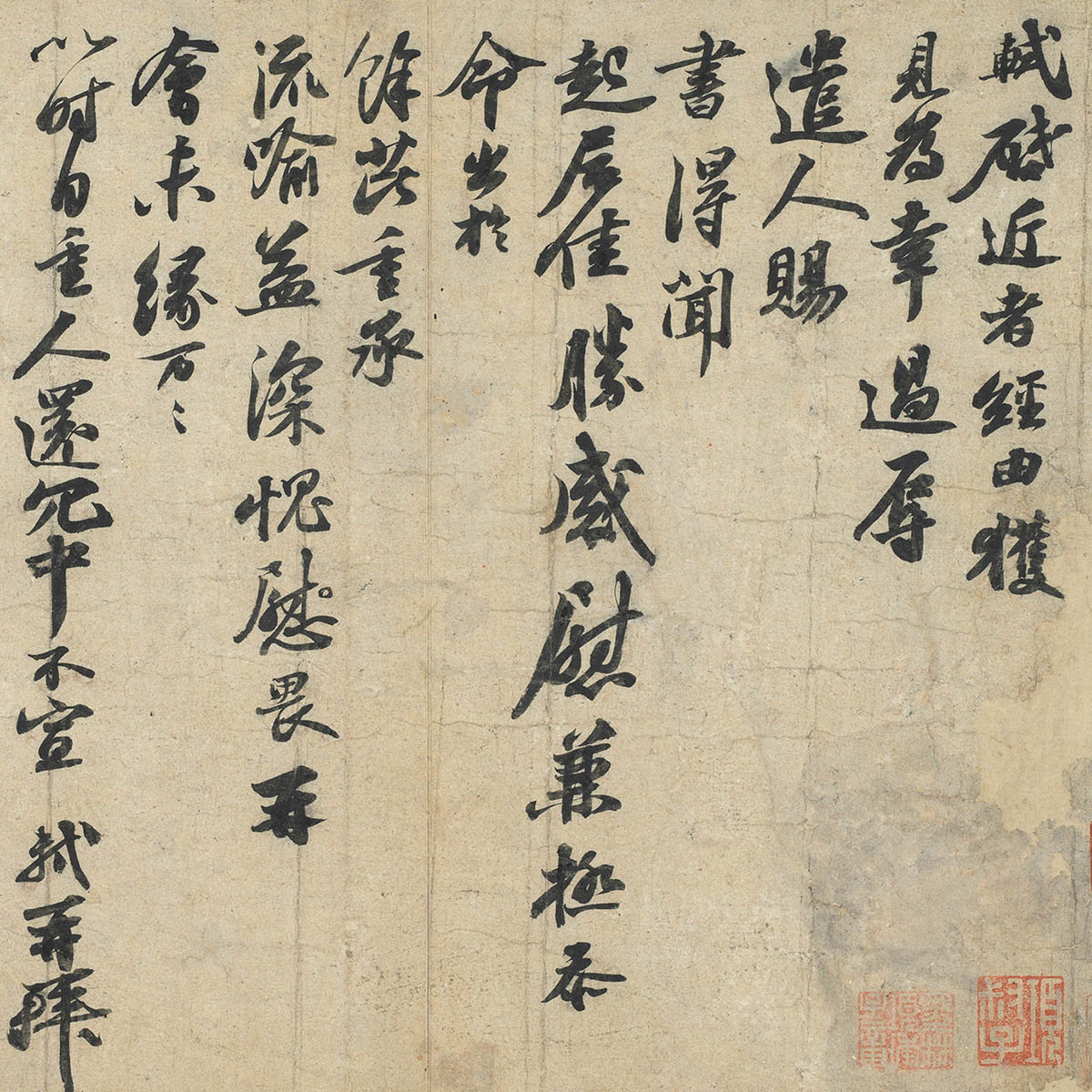

Letter

Letter

- Su Shi (1037-1101), Song dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in October 2015 as a Significant Historical Artifact

This letter by Su Shi is also known as "Huojian" and, according to its contents, believed to have been sent to Dong Yue (11th c.) in 1082. Dong Yue (style name Yifu) was an upright and aloof official who was framed by Chancellor Cai Bian (1048-1117) and relieved from office, thereupon taking his family back to Haikou. On the way, he went out of his way to stop by Huangzhou to see his friend, Su Shi, who was also living in banishment. Su's letter reveals their strong friendship despite times of trouble. The choice of paper aptly reflects the depth of their friendship as well. Throughout the paper is a pressed decoration of peonies and scrolling vegetation, between which are two large phoenixes. It was a very expensive kind of impressed letter paper at the time, and special lighting at a low angle is now able to reveal this decoration that has been all but hidden for almost a thousand years.

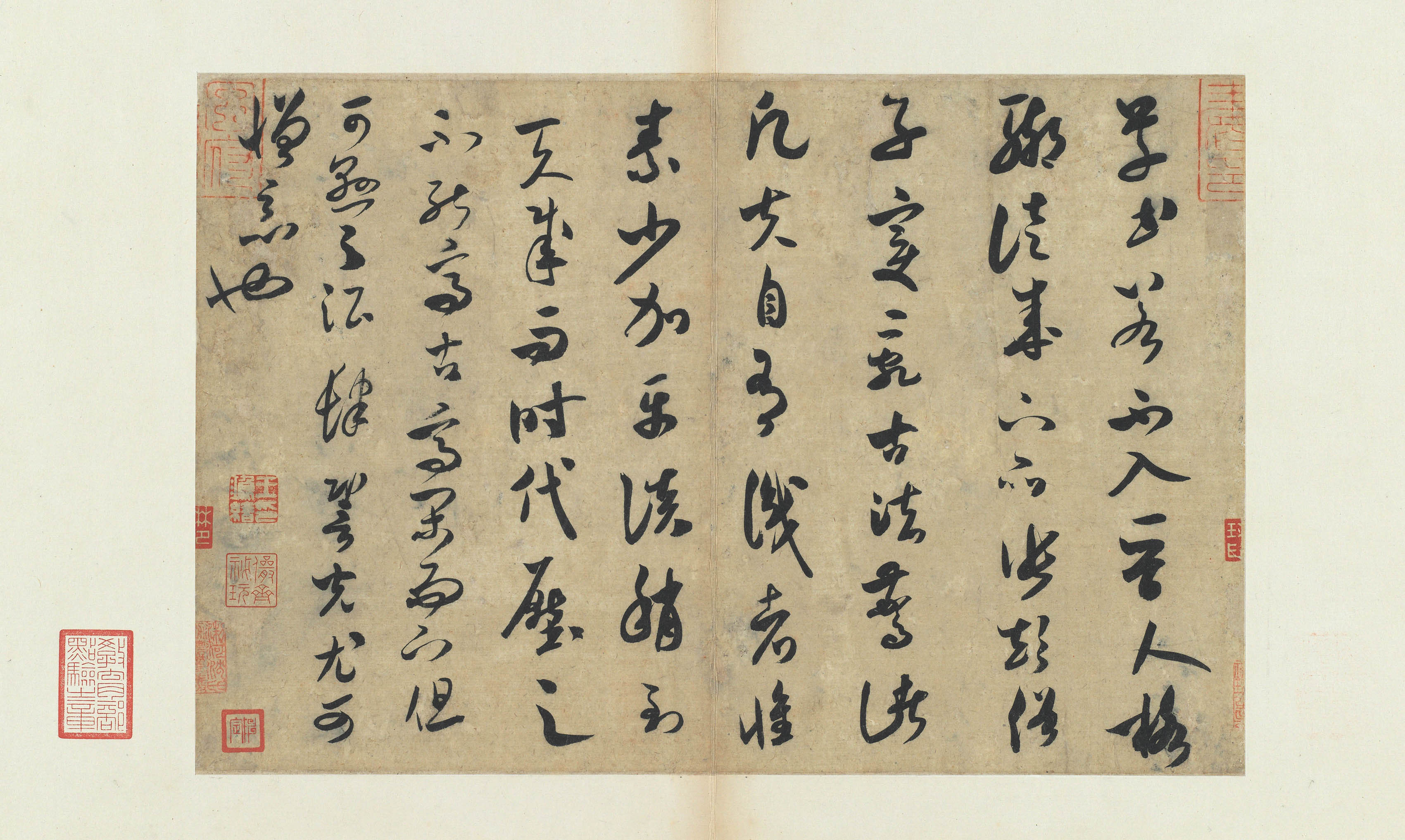

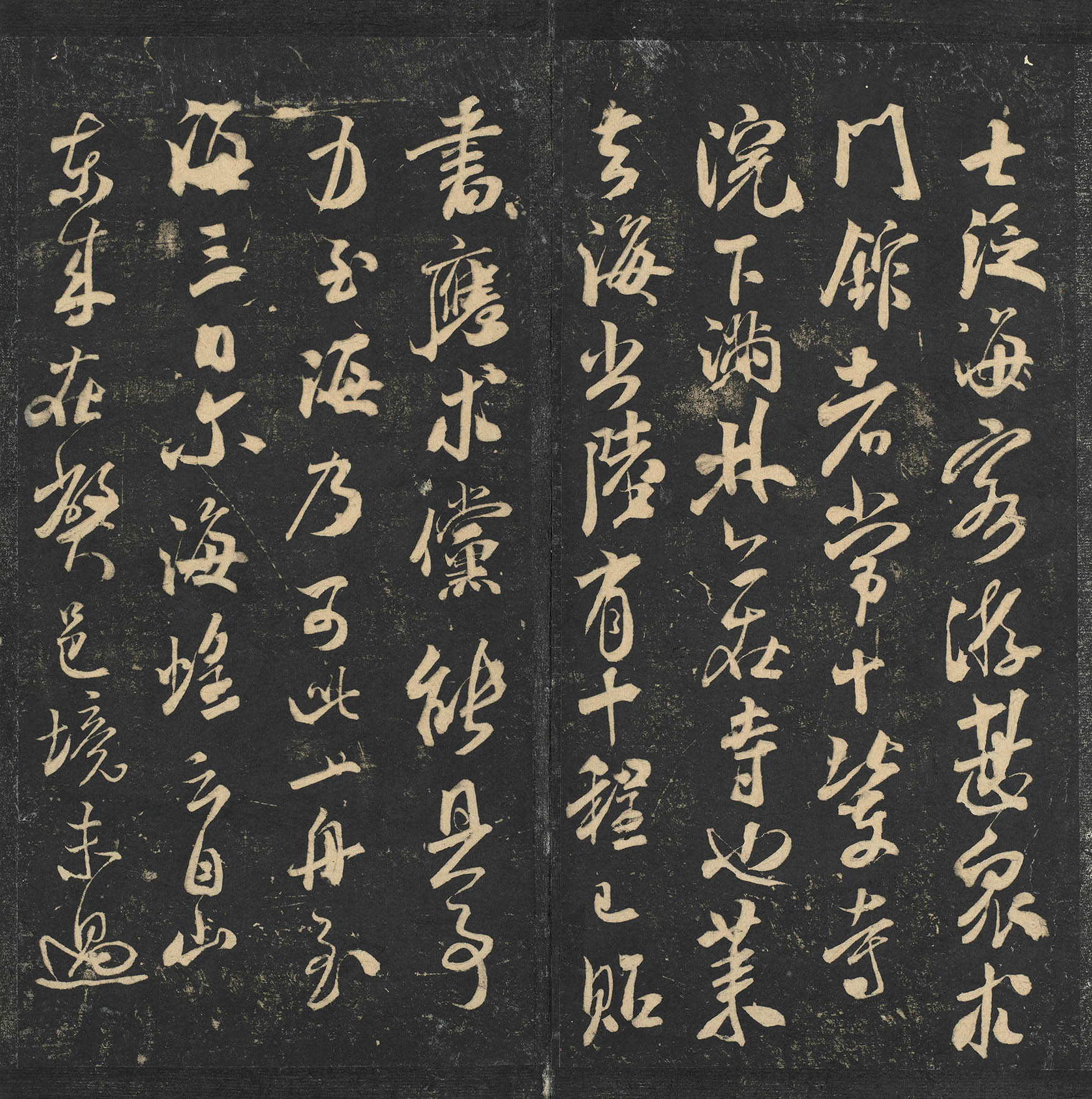

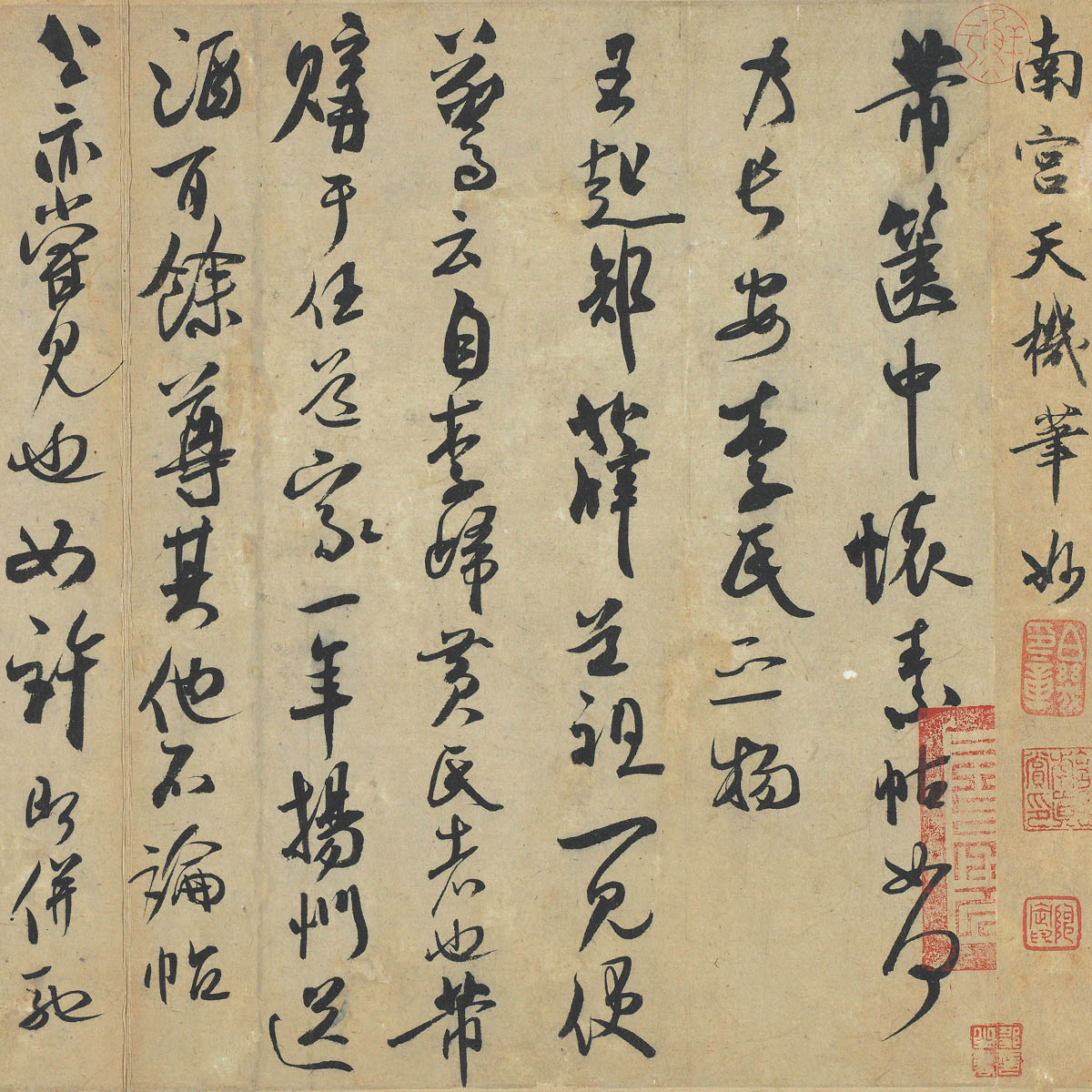

Letter to Jingwen, Honorable Xi

Letter to Jingwen, Honorable Xi

- Mi Fu (1052-1108), Song dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in January 2013 as a National Treasure

Mi Fu wrote this letter in 1091 to his friend Liu Jisun (933-1092), who also went by the style name Jingwen. In it, Mi Fu discusses a transaction involving calligraphy and objects of the scholar's studio. Although the letter is quite short, it fully reveals transitions in both brush movement and mood. In this work mostly done using running script are also elements of cursive script, with great variety in the complexity and speed of the brush strokes. For example, the five characters in the second line from the end at the left, reading "(Mi) Fu bows and calls again," form a continuous flow of rhythmic strokes that expresses Mi Fu's own free and unbridled spirit.

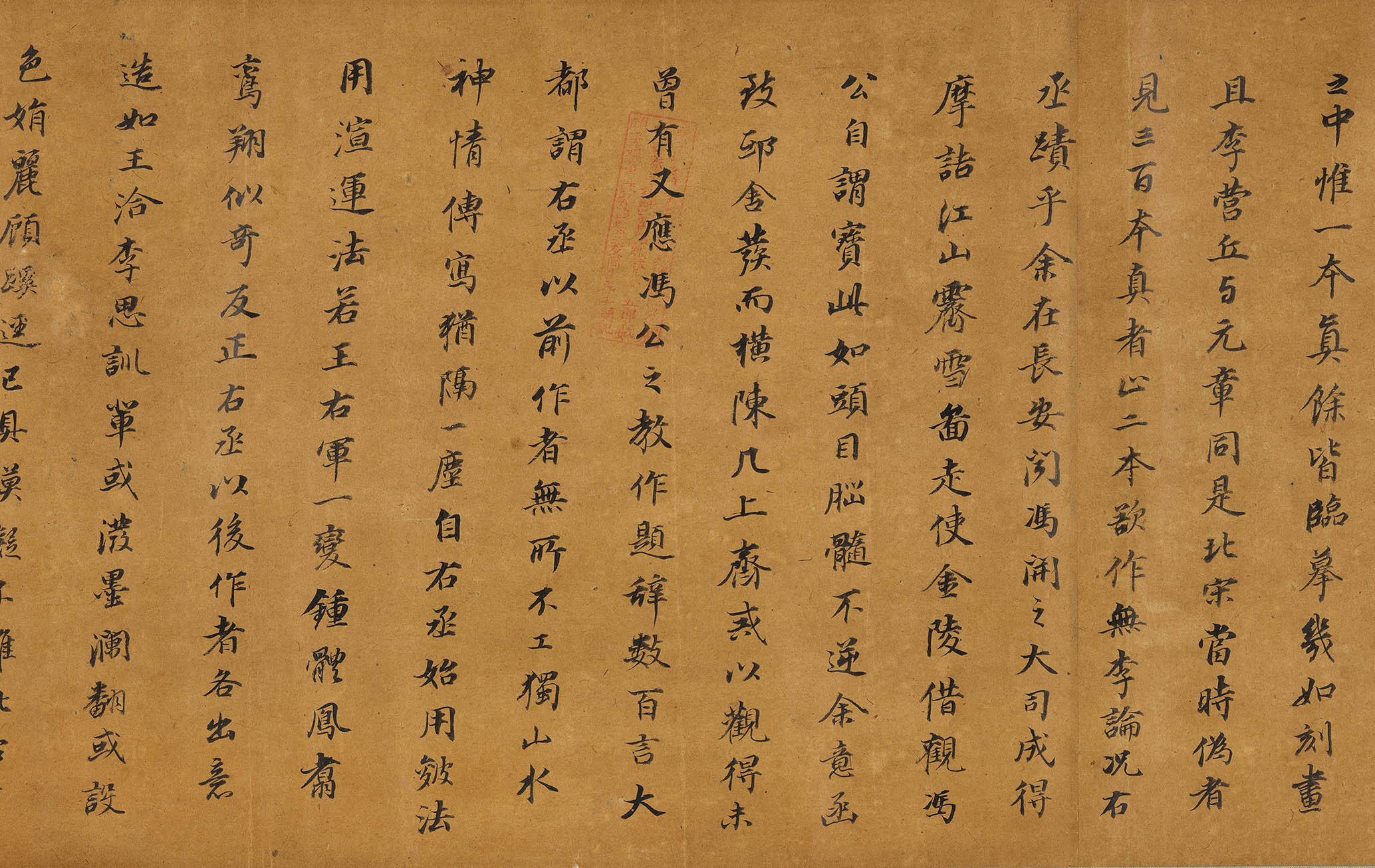

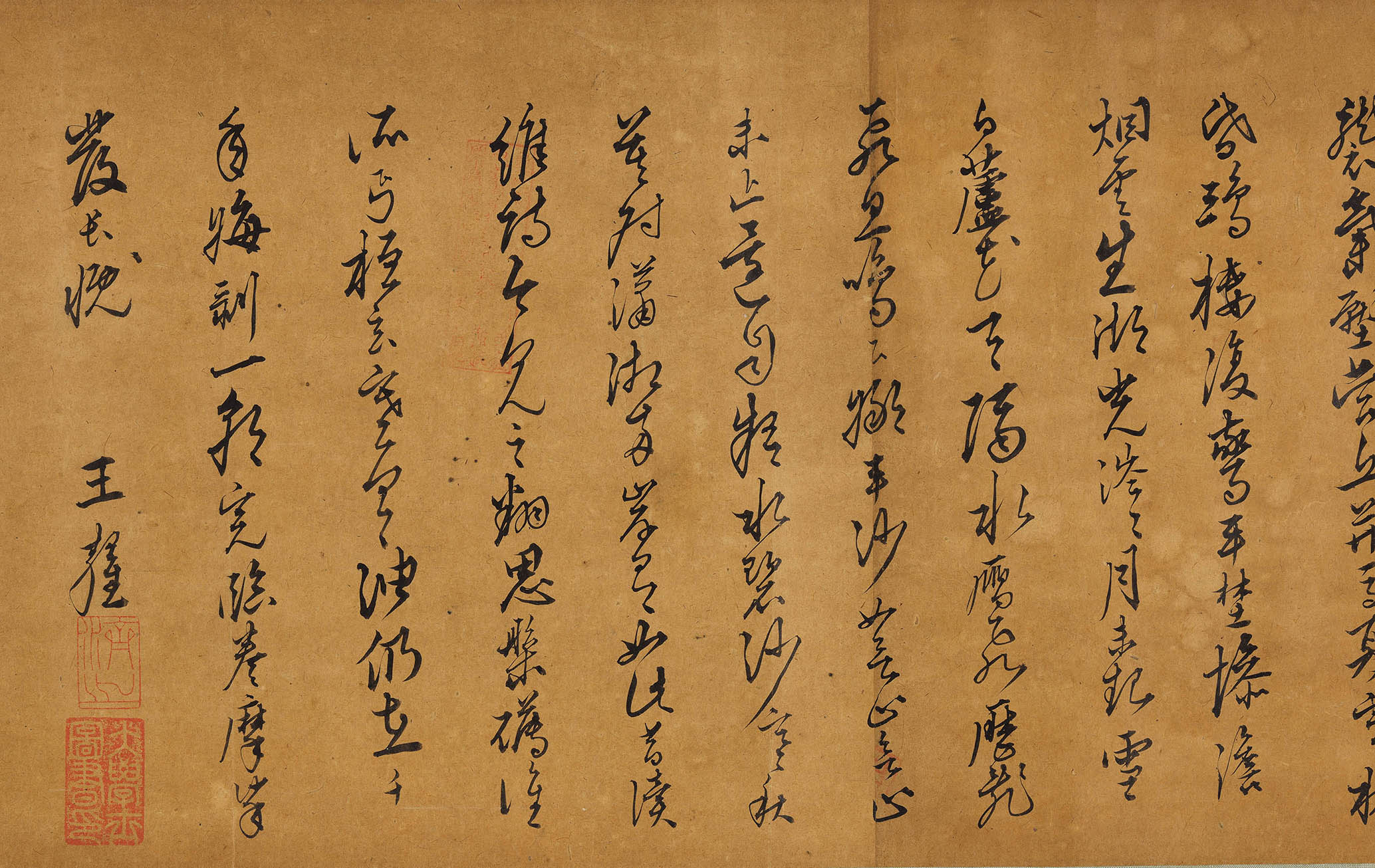

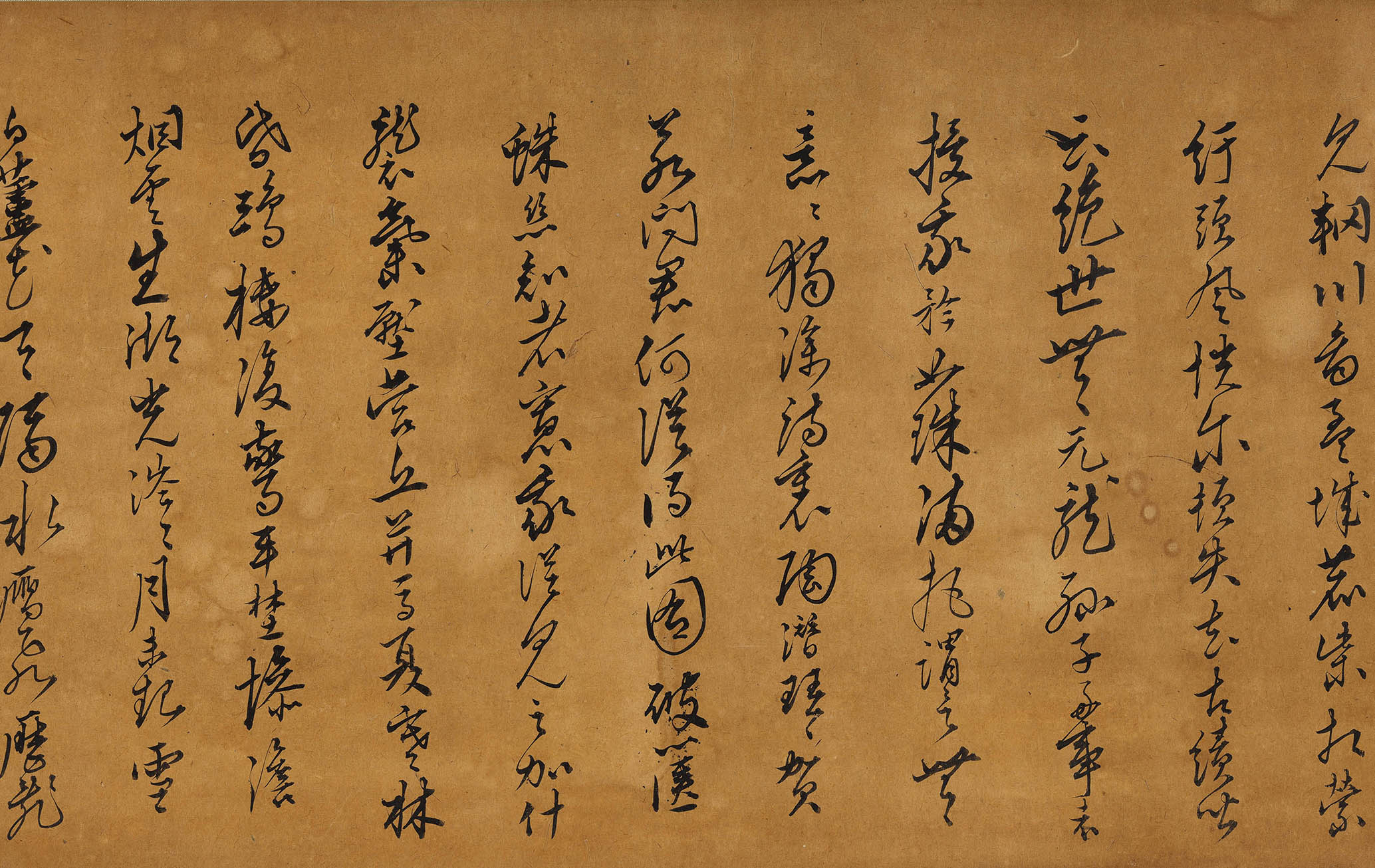

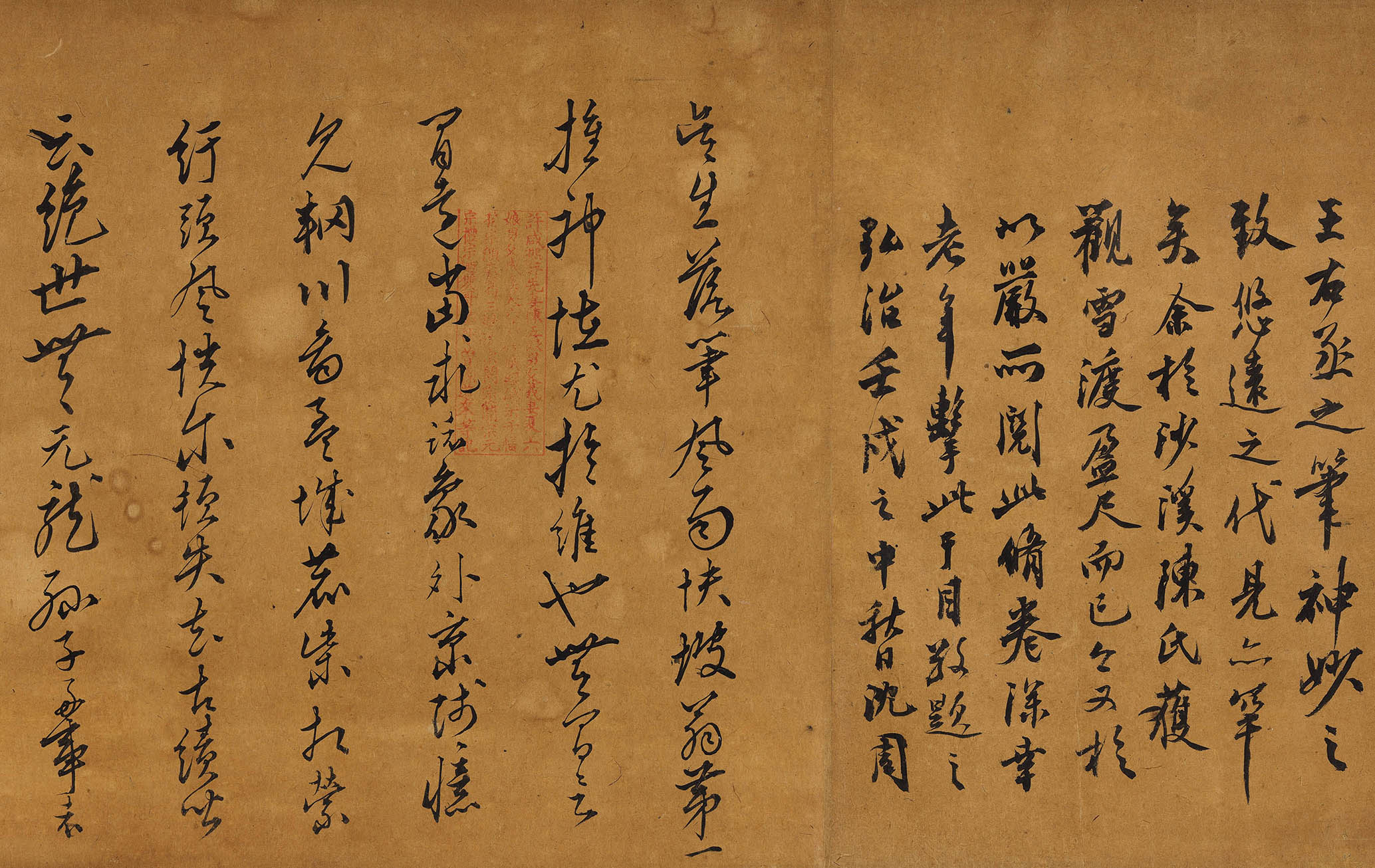

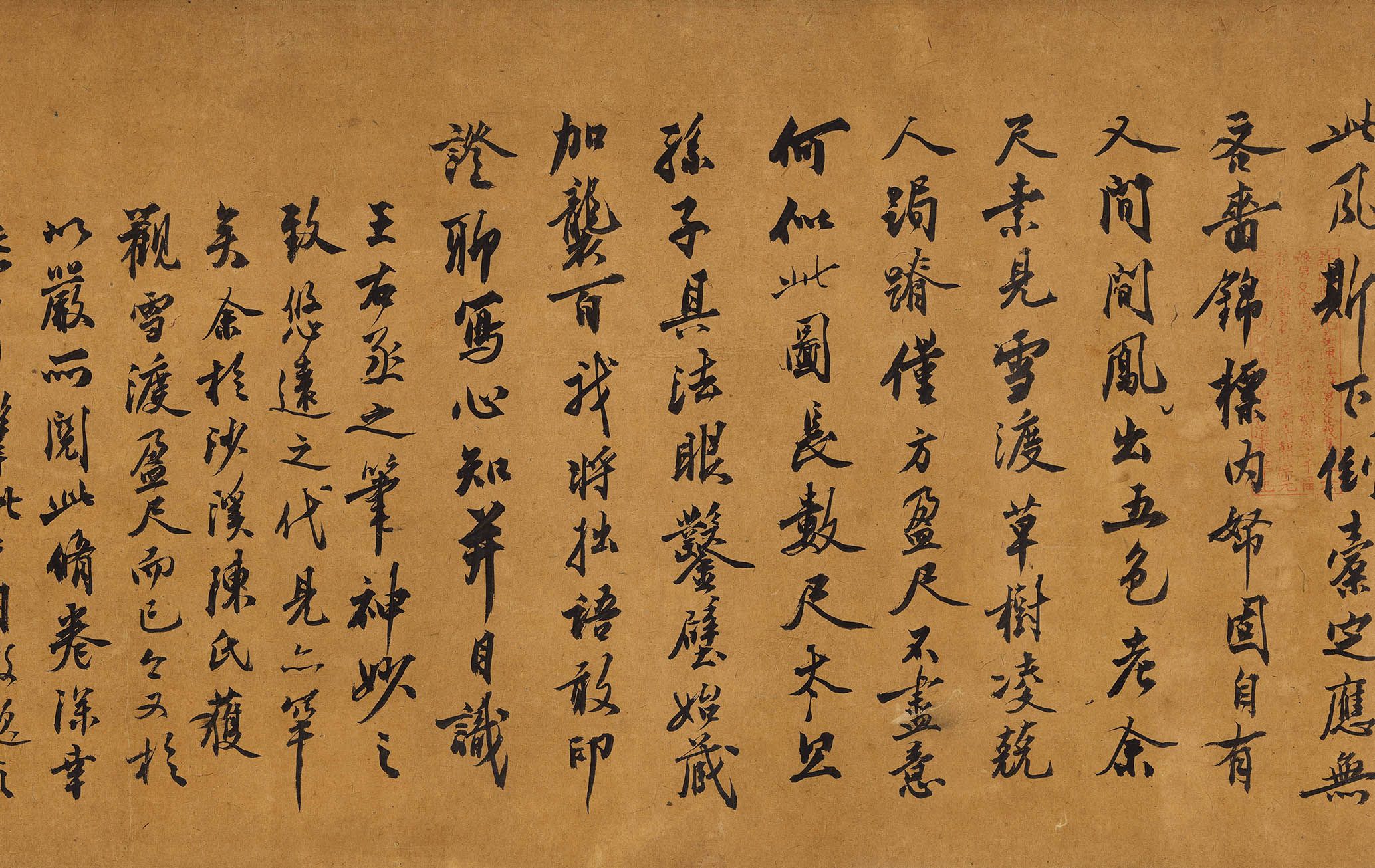

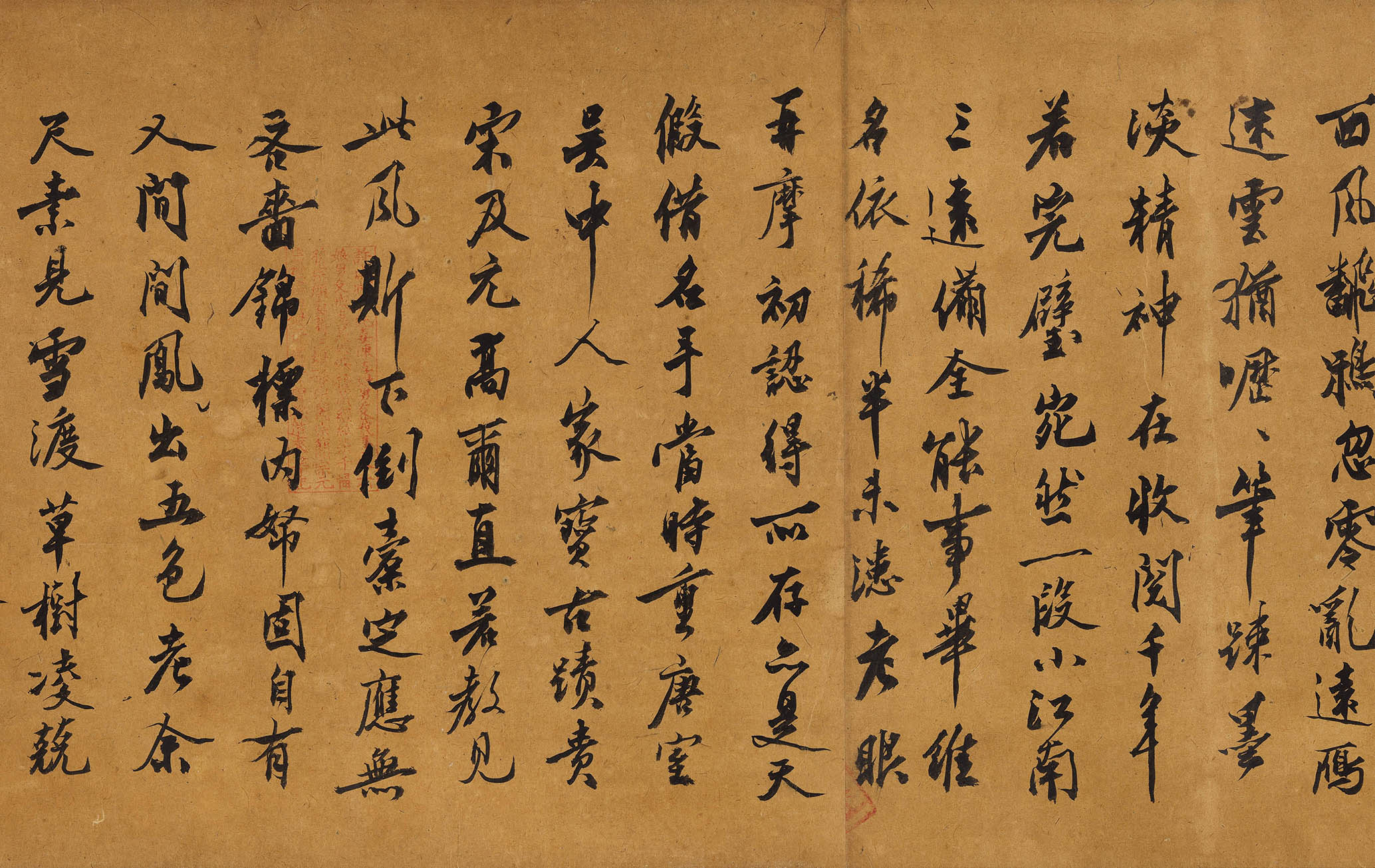

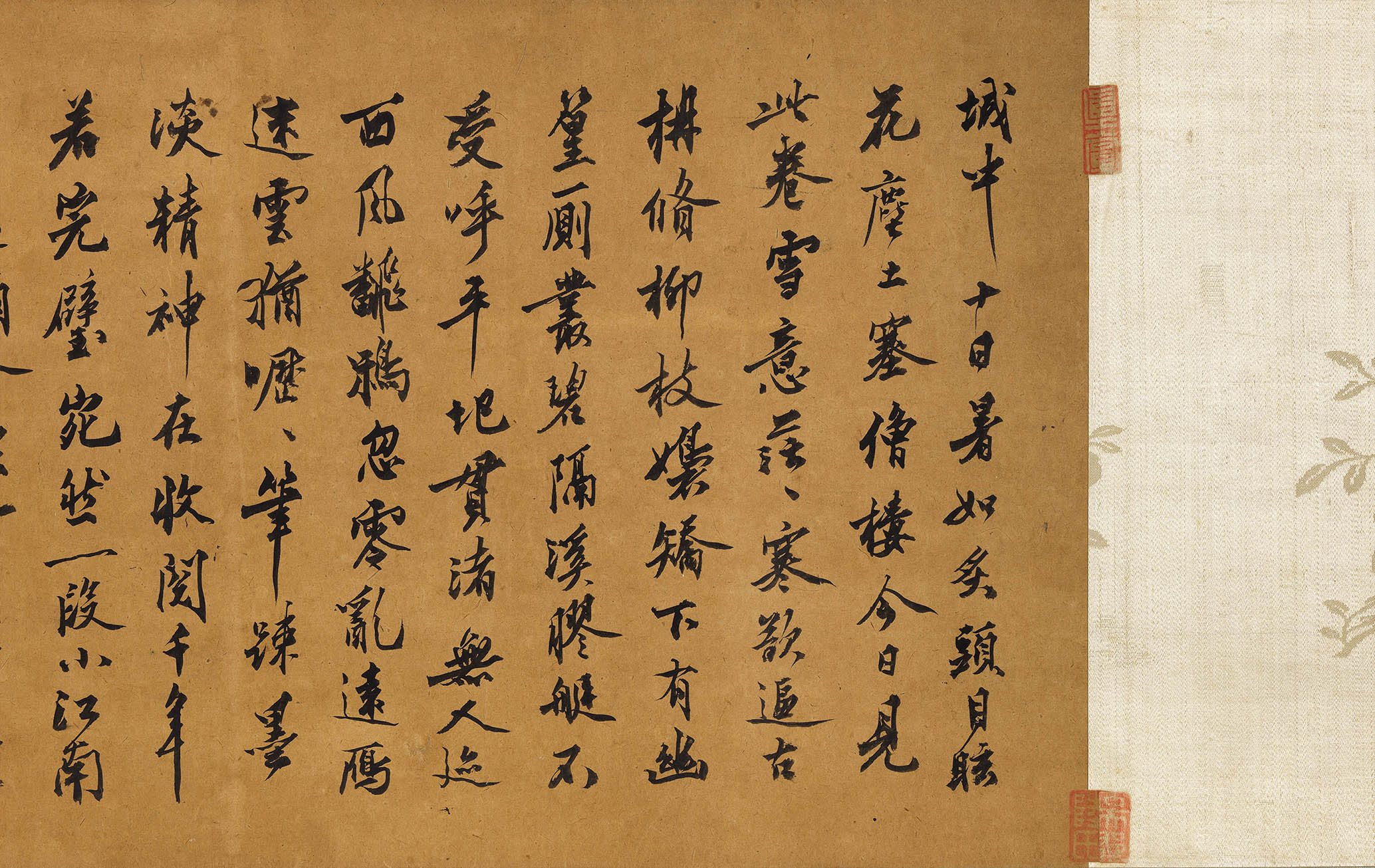

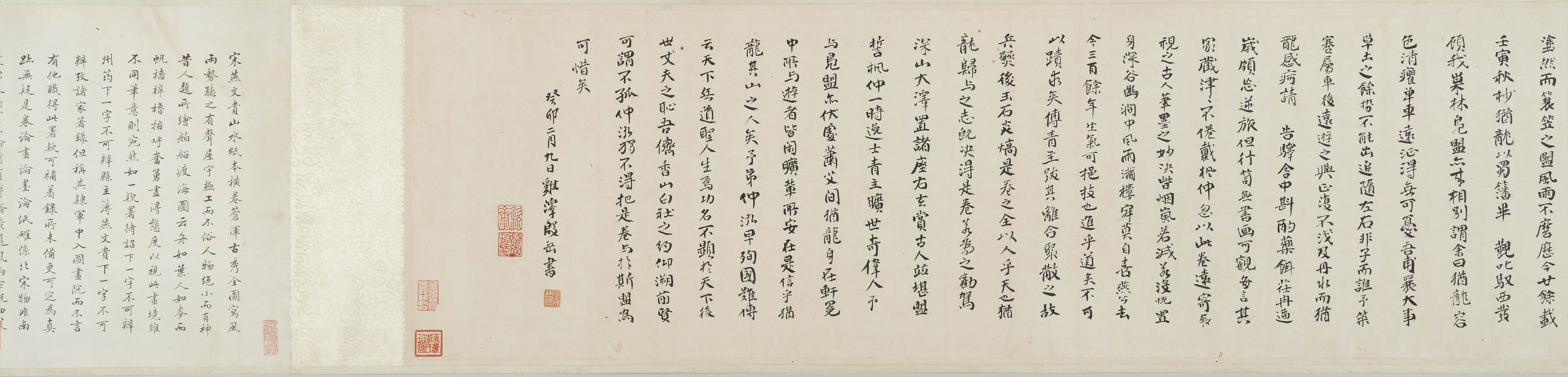

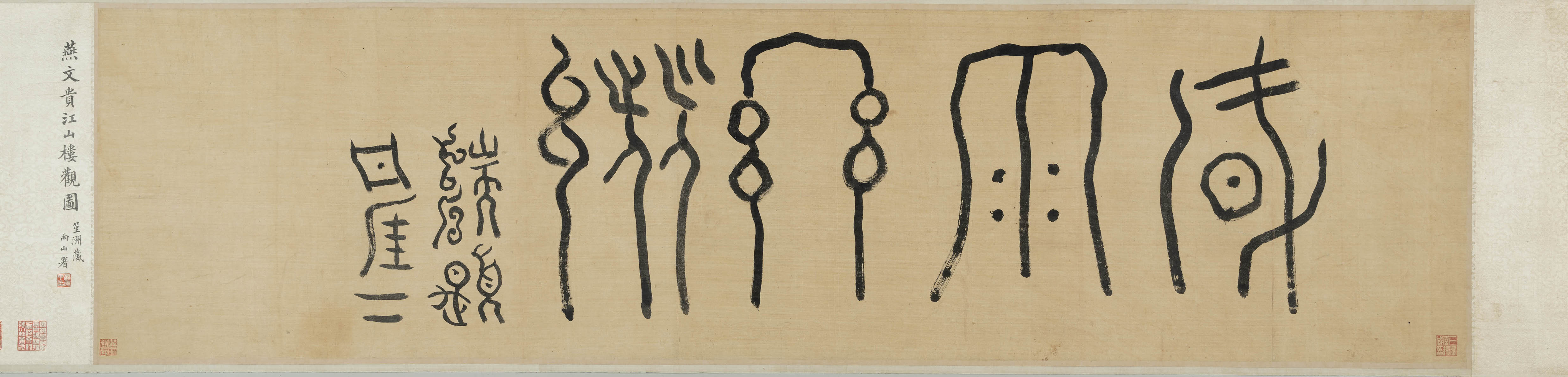

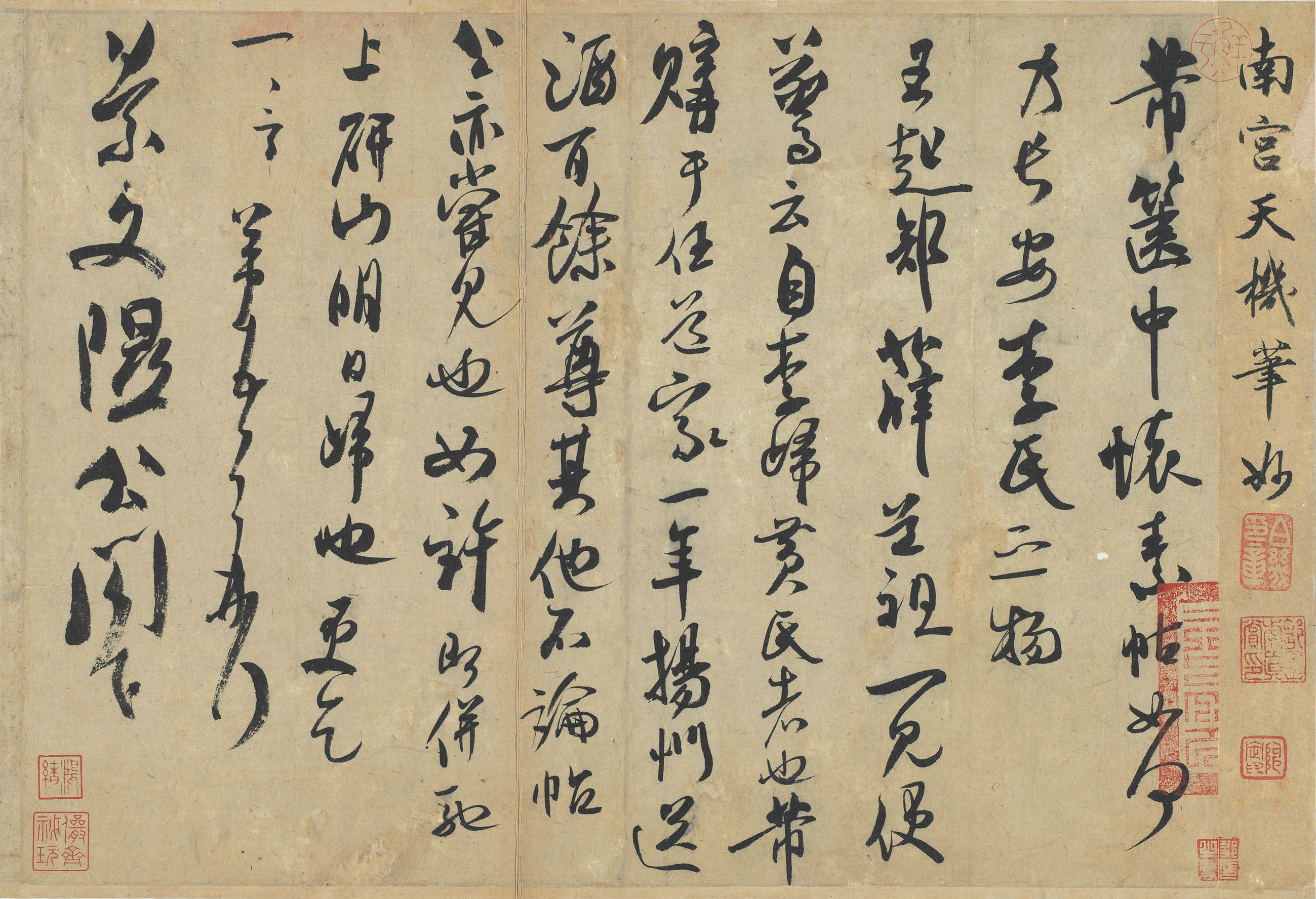

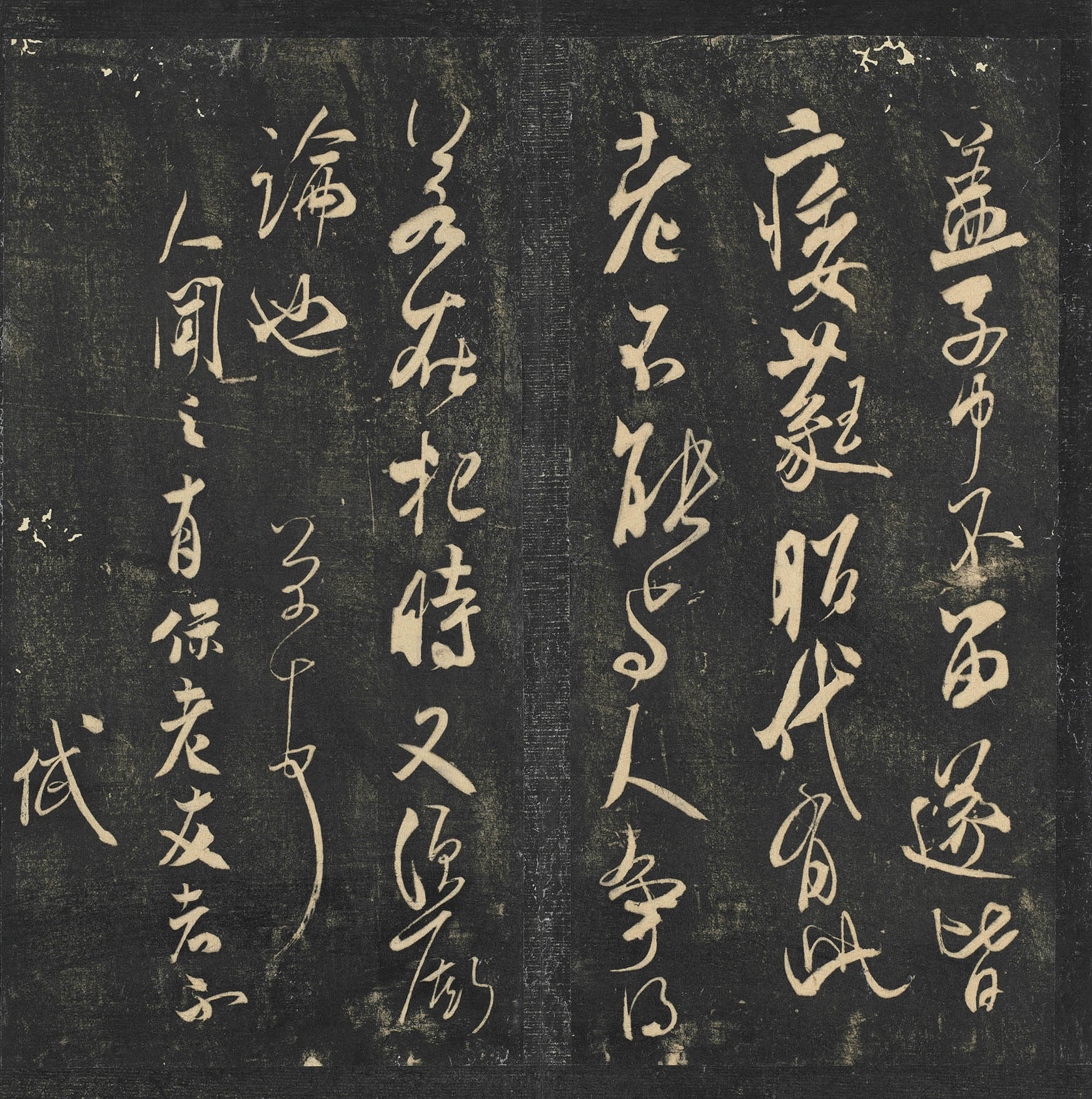

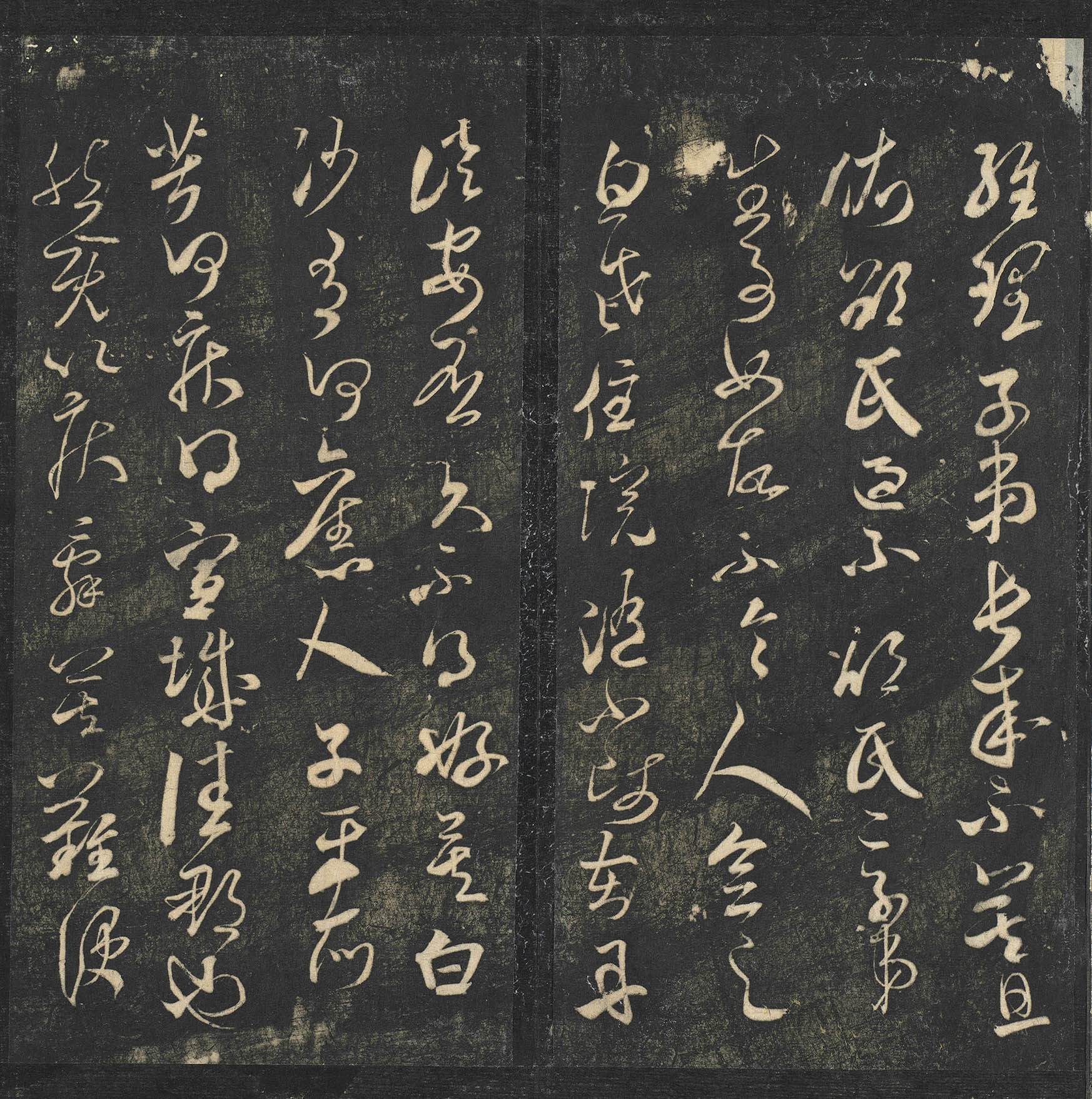

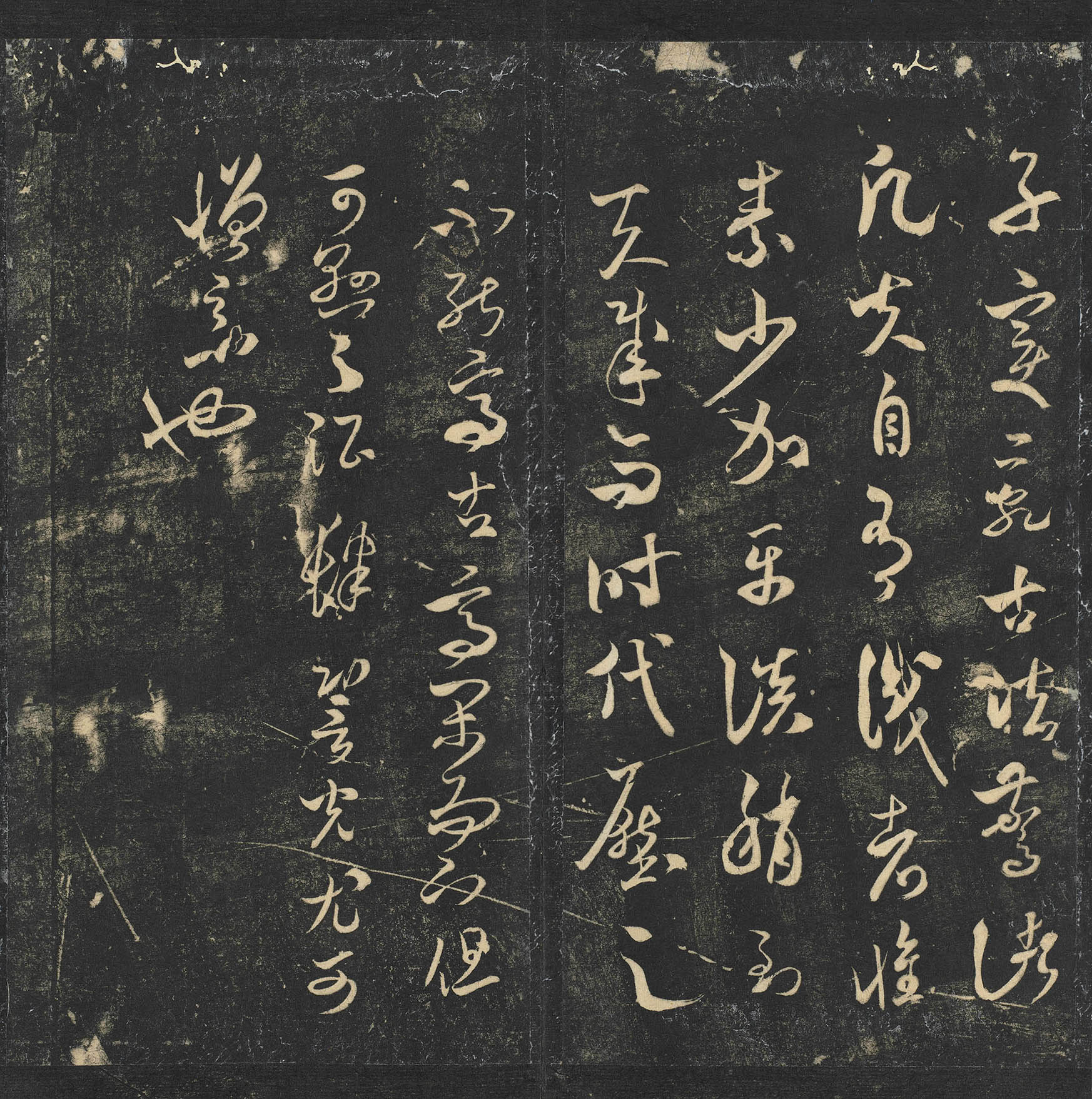

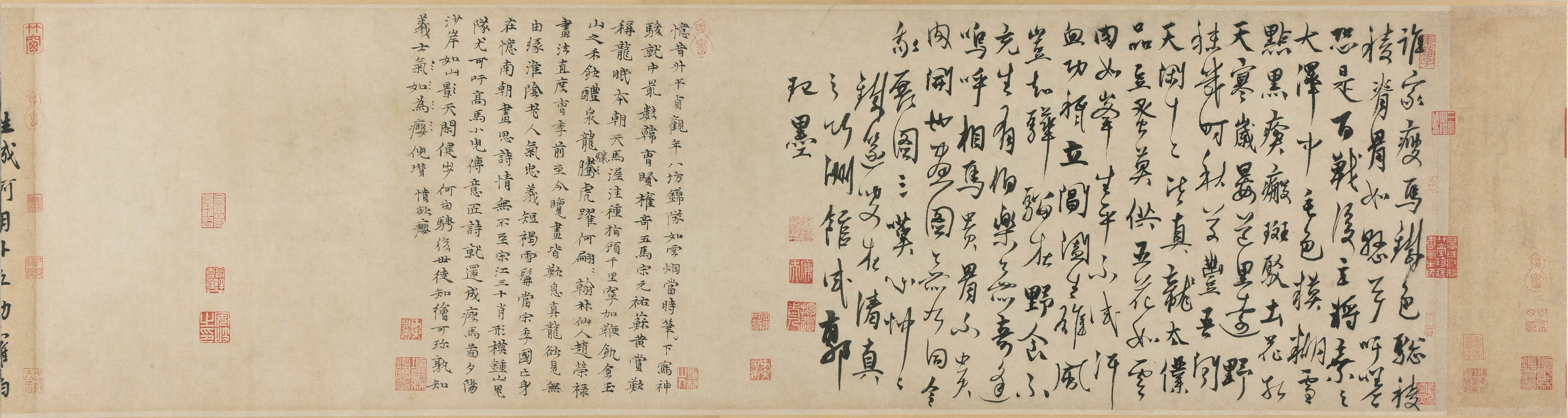

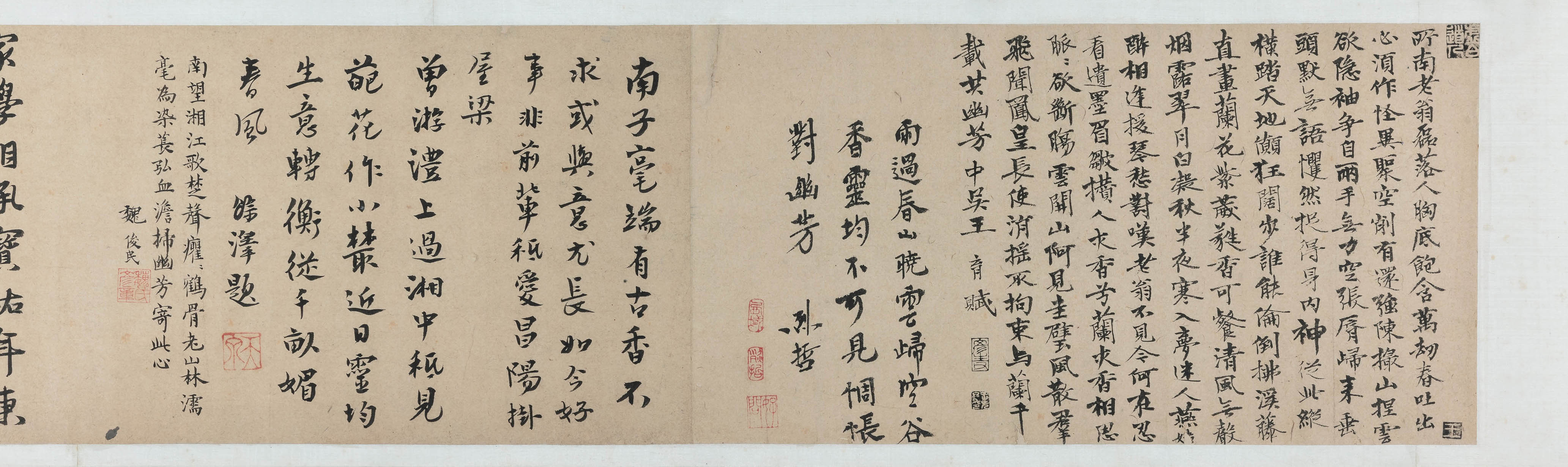

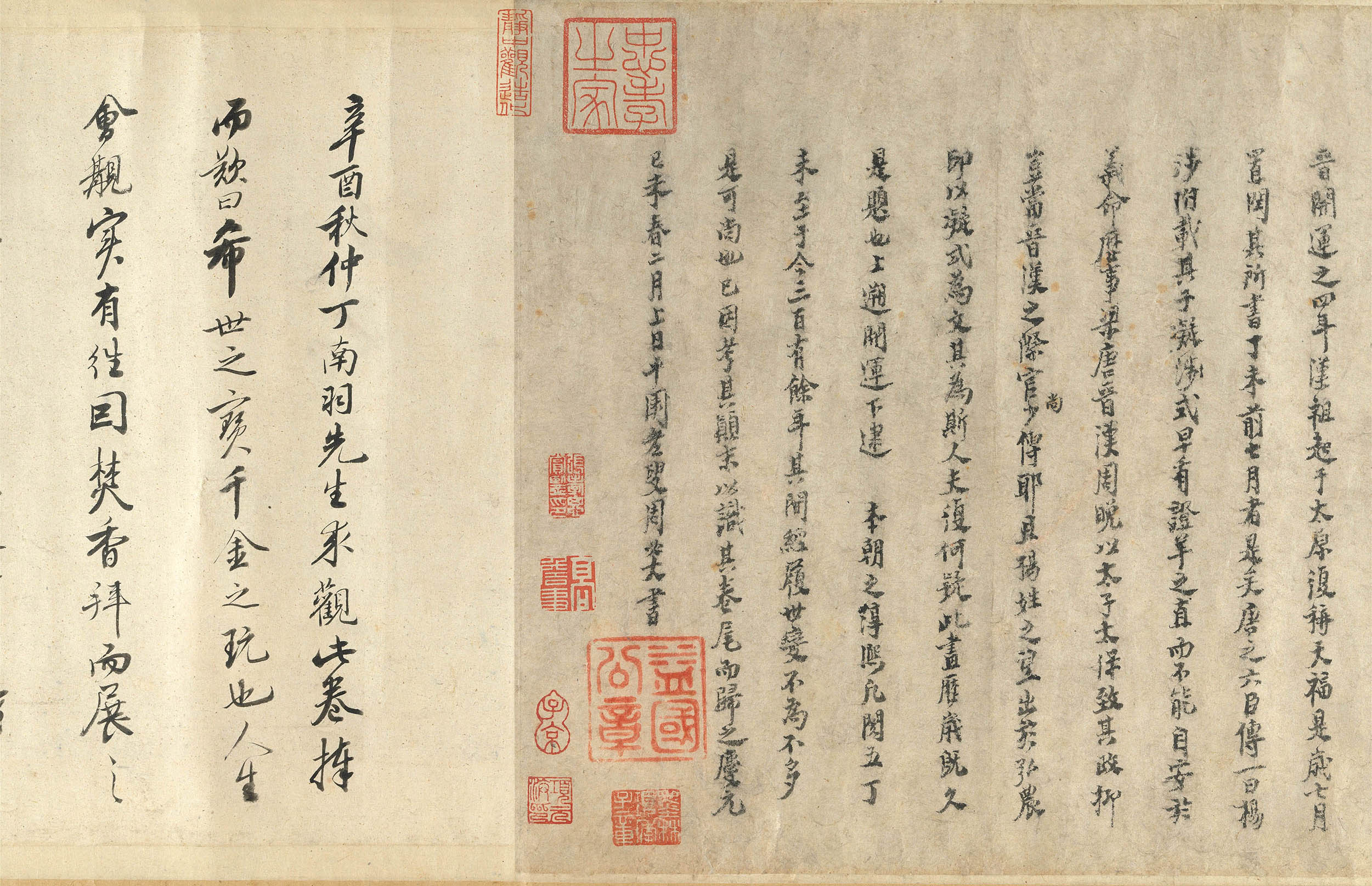

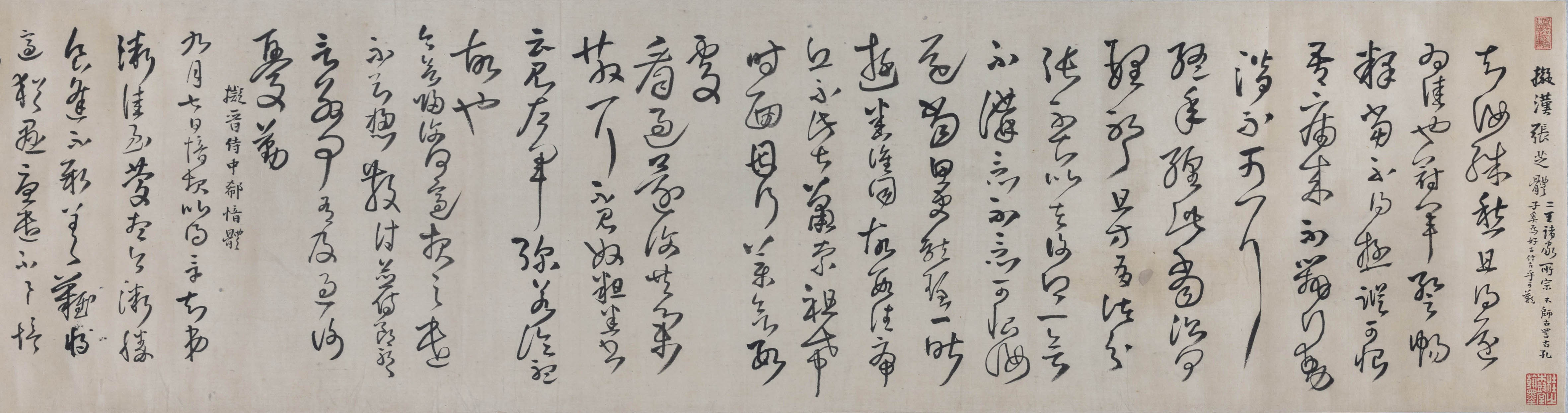

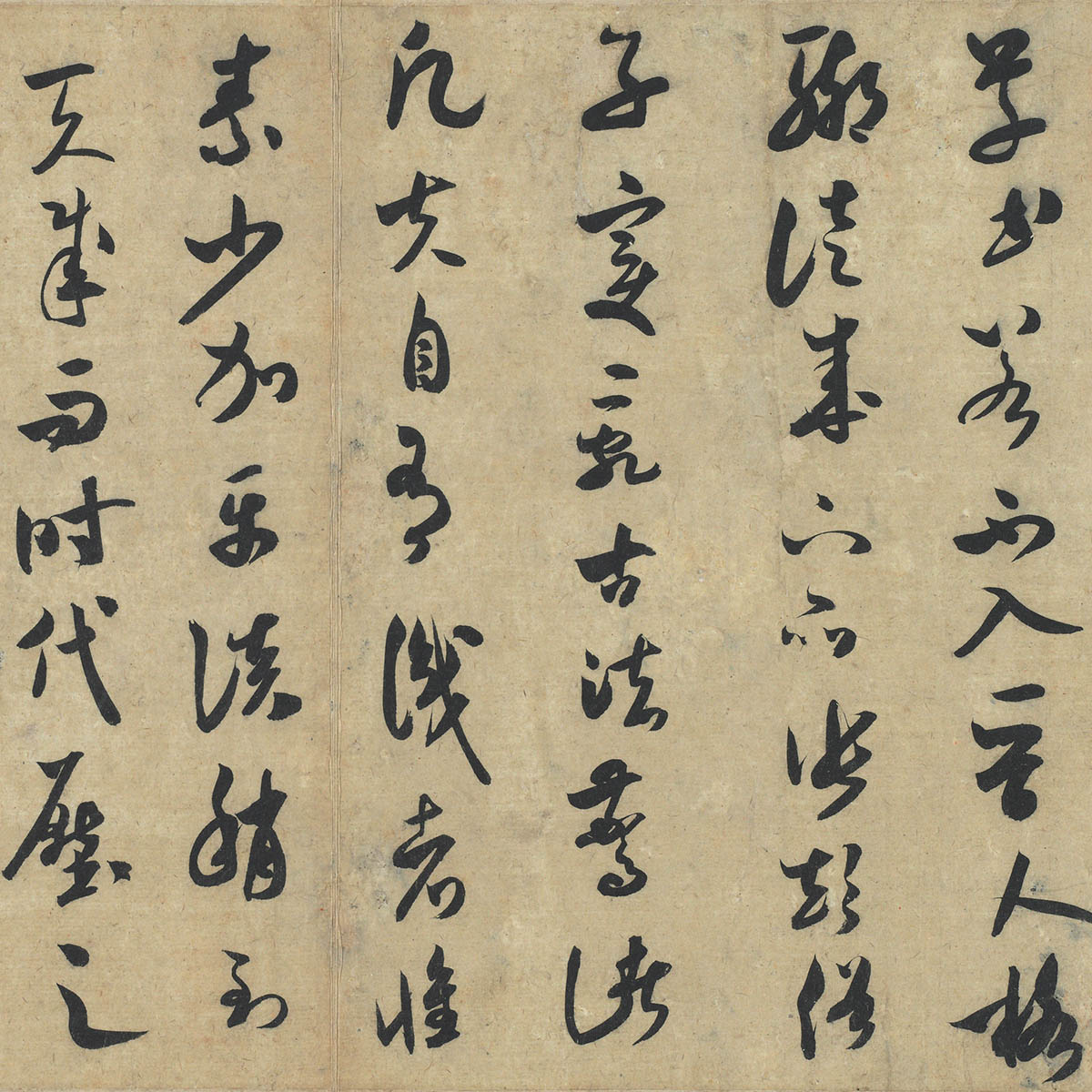

Discourse on Calligraphy

Discourse on Calligraphy

- Mi Fu (1052-1108), Song dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in January 2013 as a National Treasure

Mi Fu, style name Yuanzhang, was a native of Xiangyang in Hubei and an excellent art connoisseur summoned during the reign of Emperor Huizong to serve the court as Erudite of Painting and Calligraphy.

This modelbook is the fifth one from "Nine Modelbooks of Cursive Script" and also known as "Caoshu" (or "Cursive Script"). The contents are a discourse on and ranking of cursive script, upholding the style of Jin dynasty calligraphers as the highest standard while using more denigrating terms for the cursive script of such Tang dynasty masters as Zhang Xu, Huaisu, and Gao Xian. Similar discussions upholding the Jin and looking down on the Tang can be found throughout his text. In terms of style, the entire work is done in the modern cursive manner of plain simplicity associated with Jin calligraphers and avoids the "wilder" brush methods of Tang cursive, Mi Fu's style expressing the ideas that he advocated in his text.

This modelbook is the fifth one from "Nine Modelbooks of Cursive Script" and also known as "Caoshu" (or "Cursive Script"). The contents are a discourse on and ranking of cursive script, upholding the style of Jin dynasty calligraphers as the highest standard while using more denigrating terms for the cursive script of such Tang dynasty masters as Zhang Xu, Huaisu, and Gao Xian. Similar discussions upholding the Jin and looking down on the Tang can be found throughout his text. In terms of style, the entire work is done in the modern cursive manner of plain simplicity associated with Jin calligraphers and avoids the "wilder" brush methods of Tang cursive, Mi Fu's style expressing the ideas that he advocated in his text.

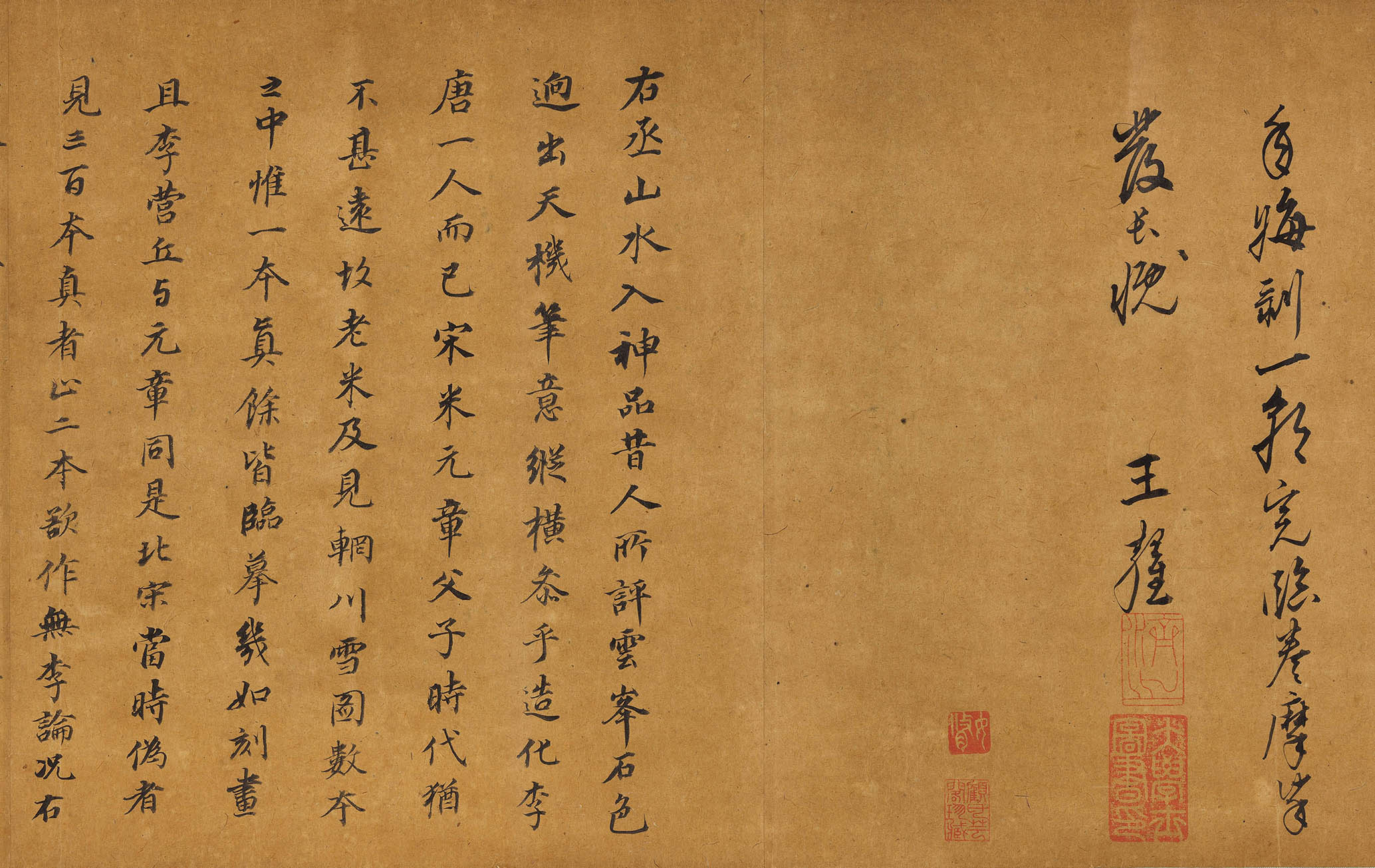

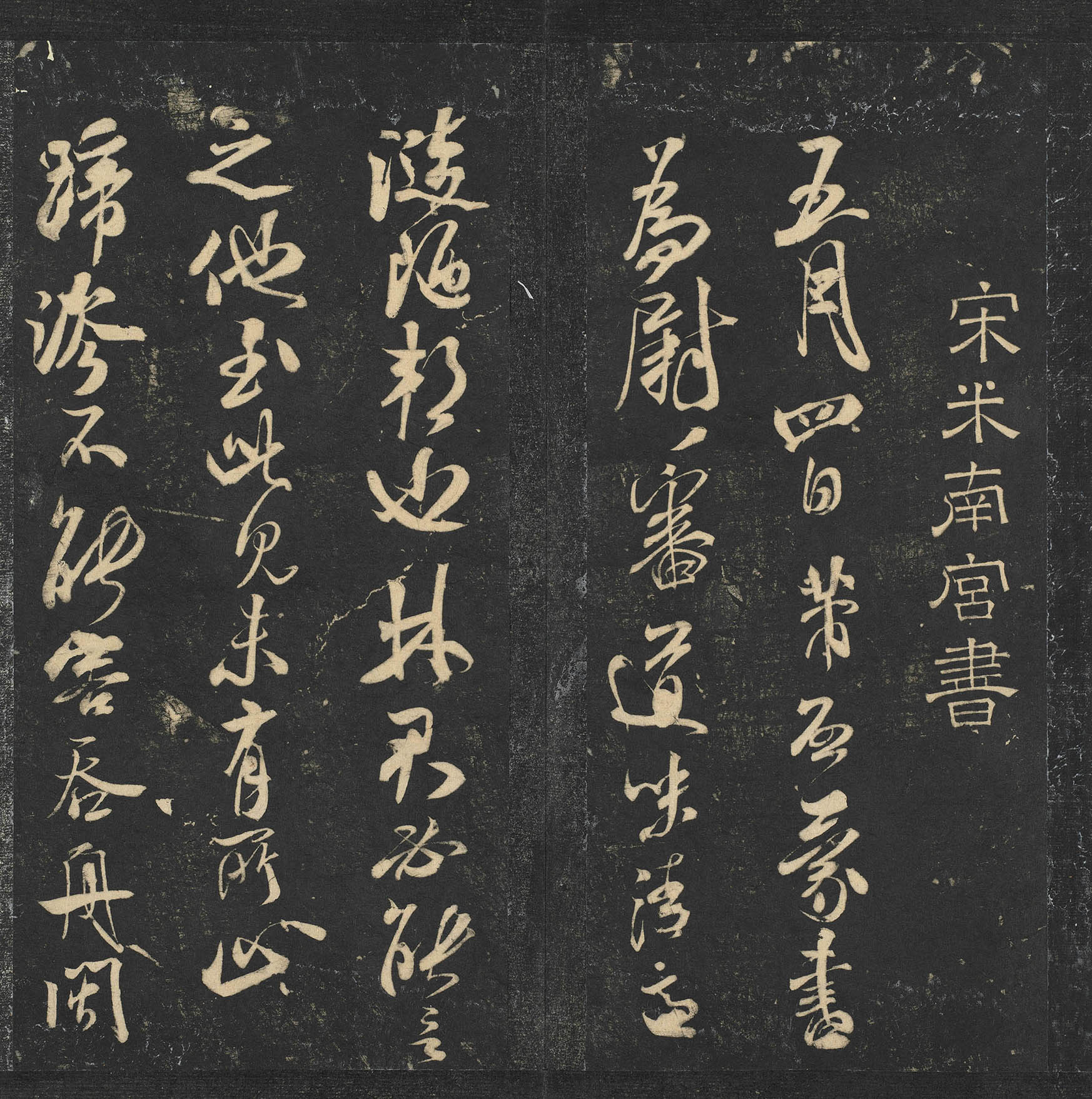

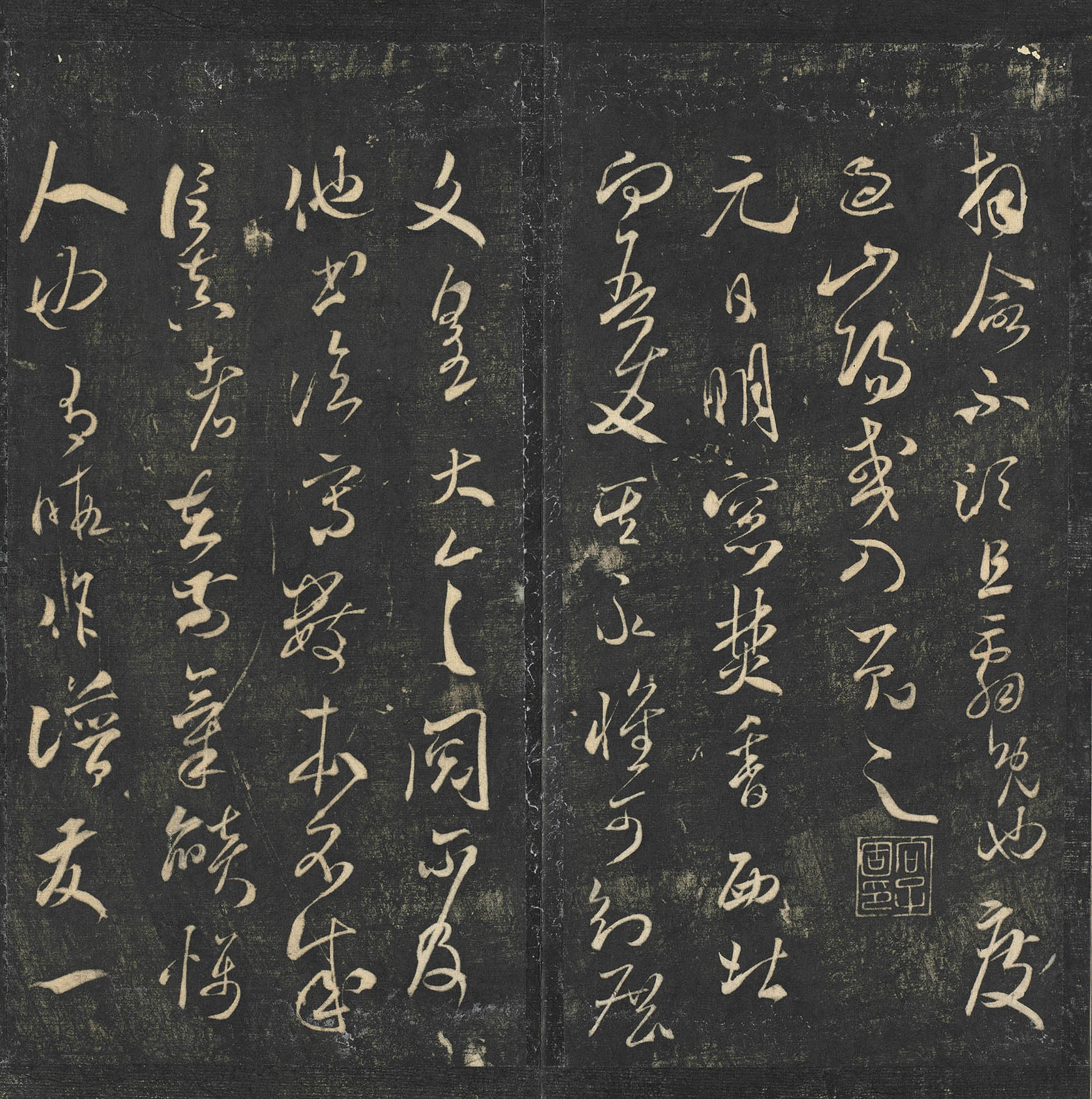

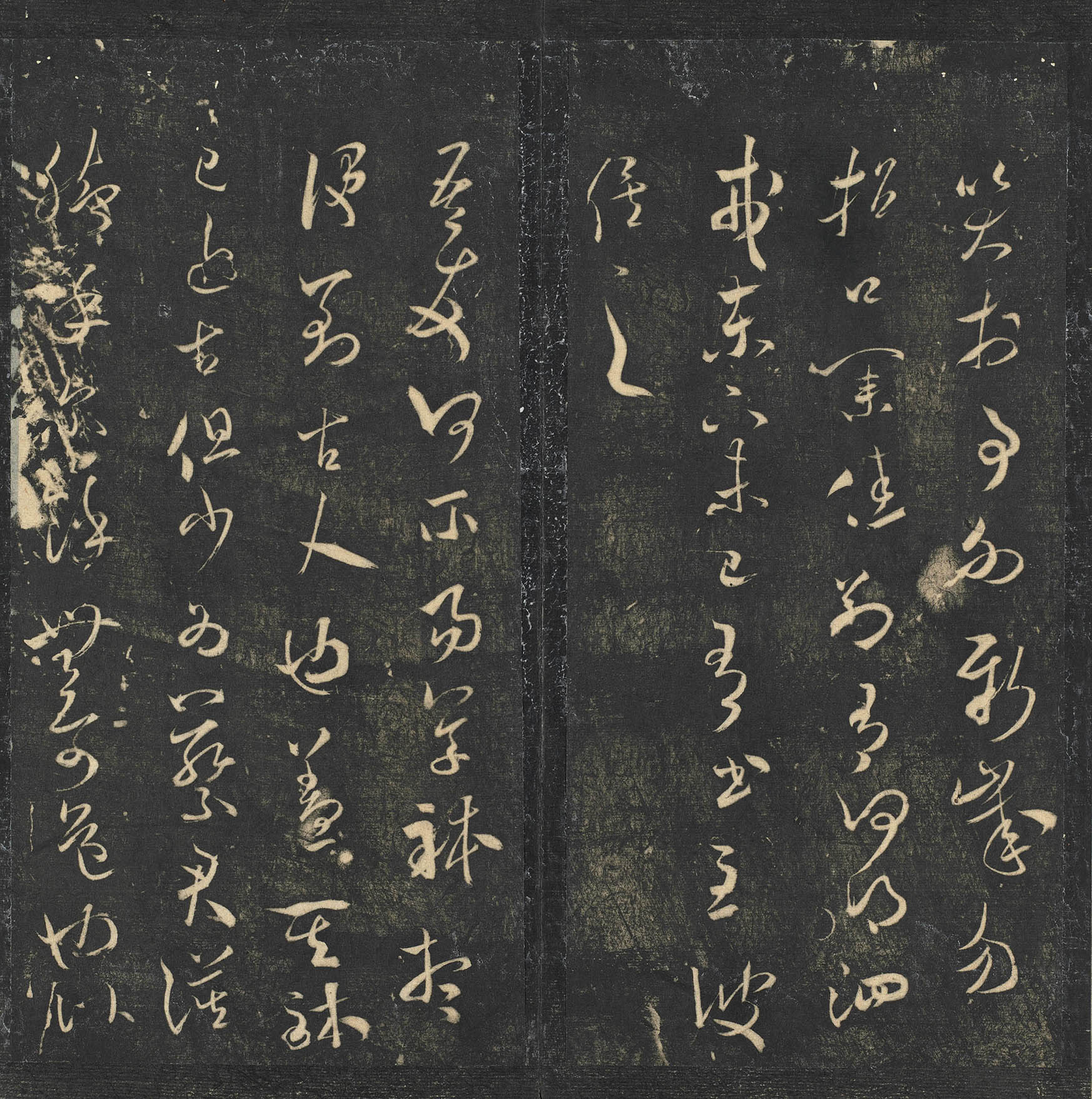

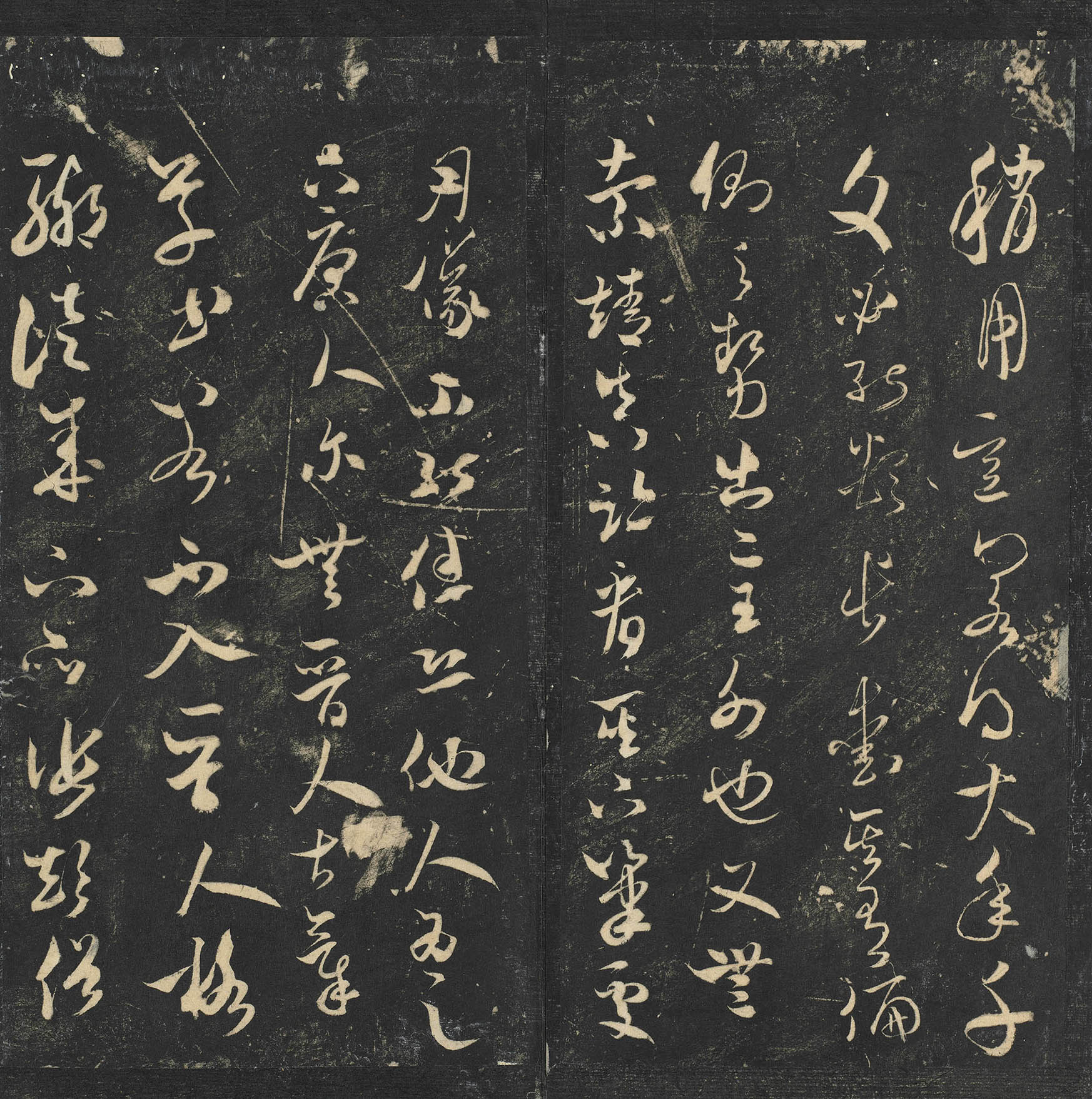

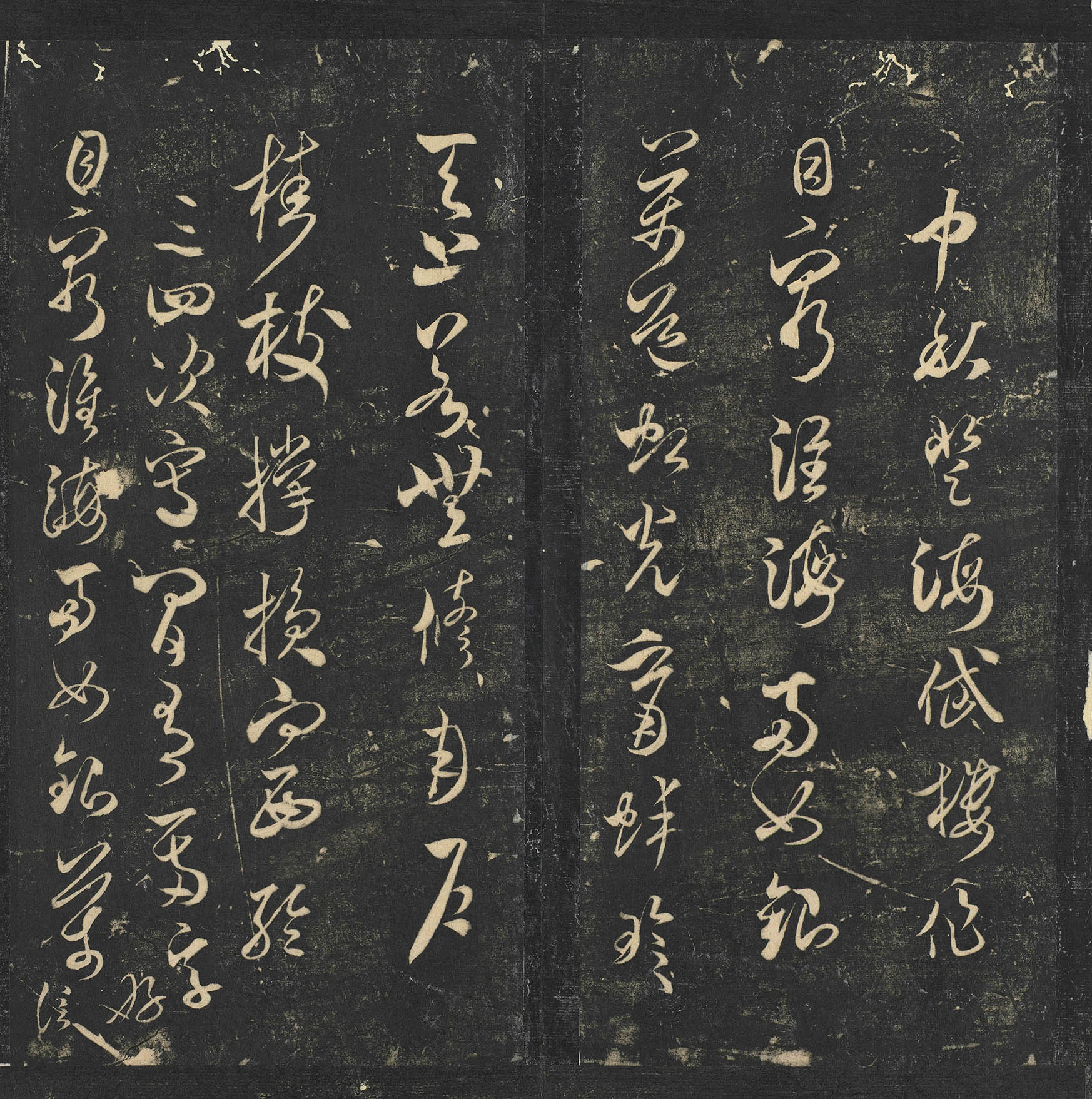

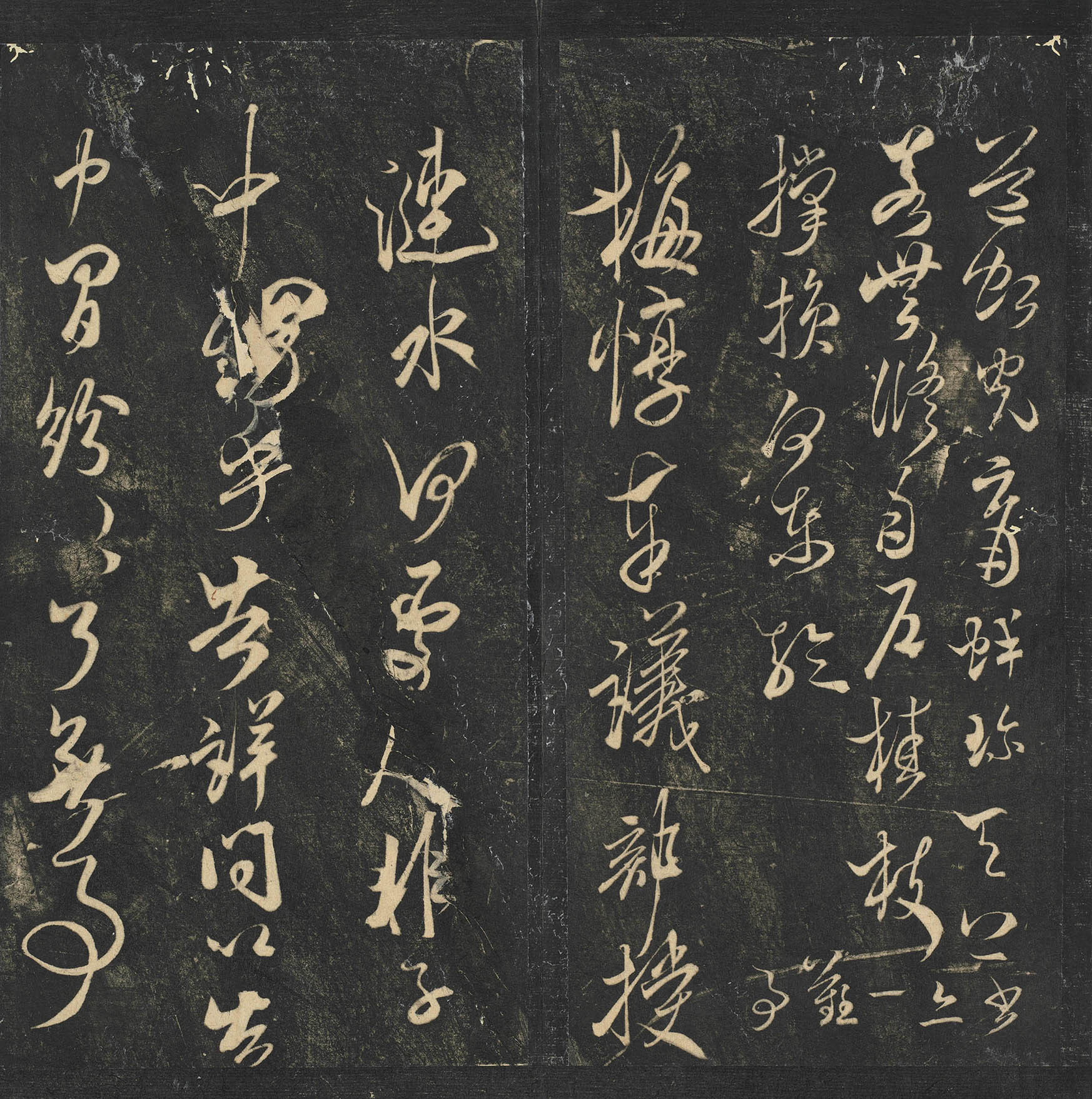

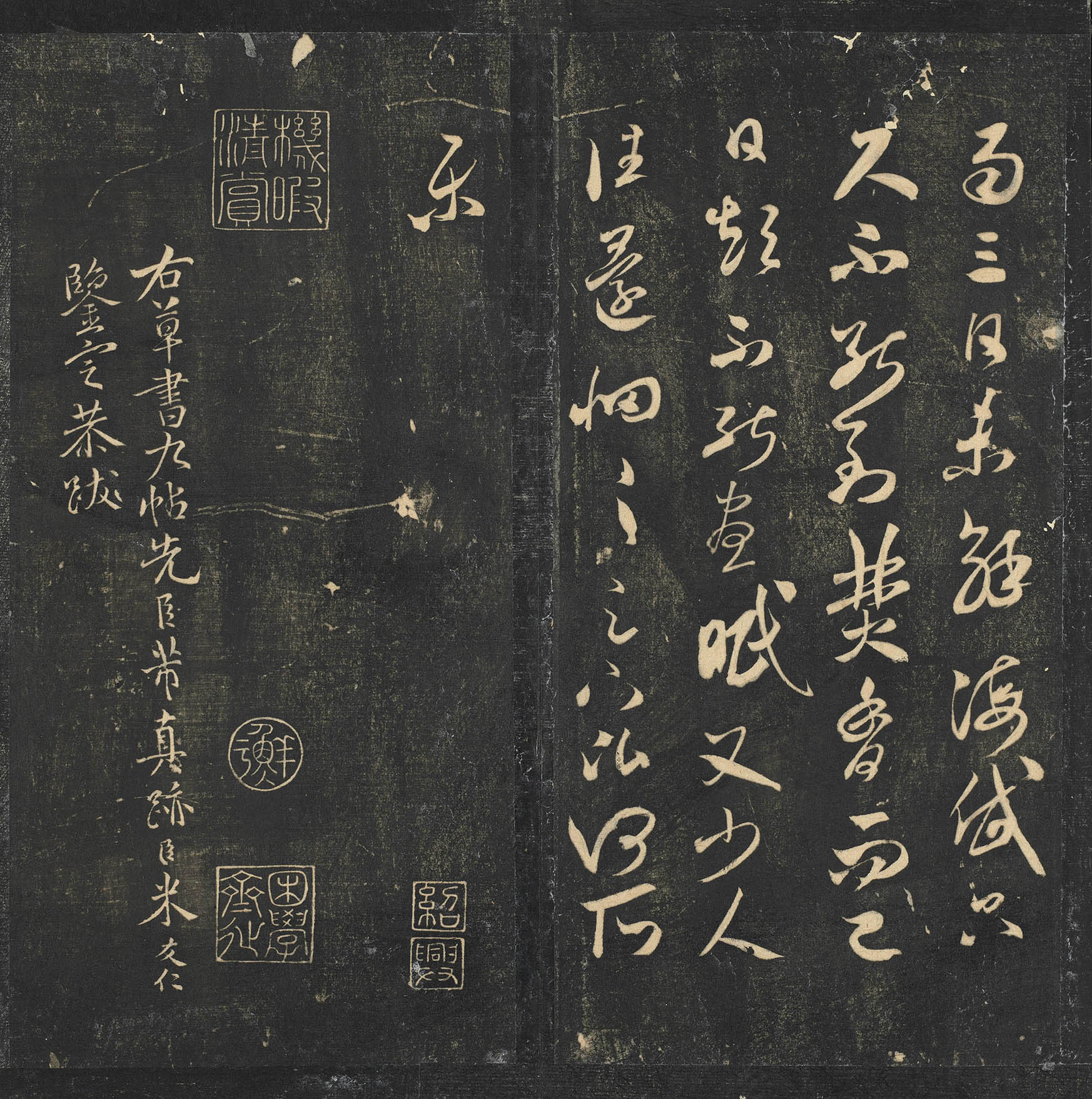

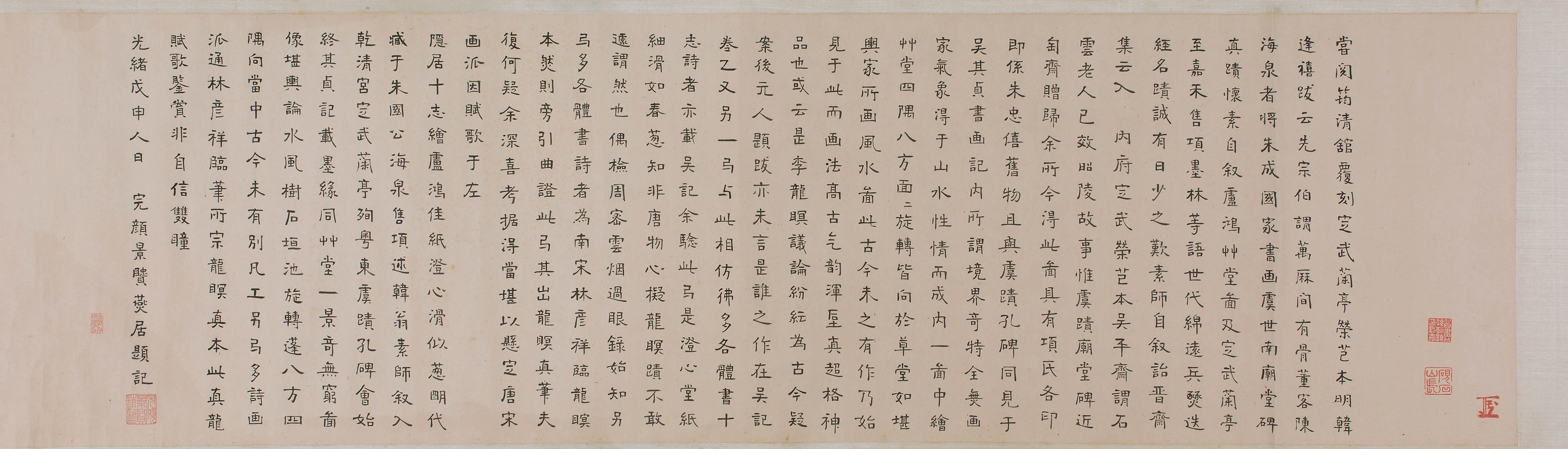

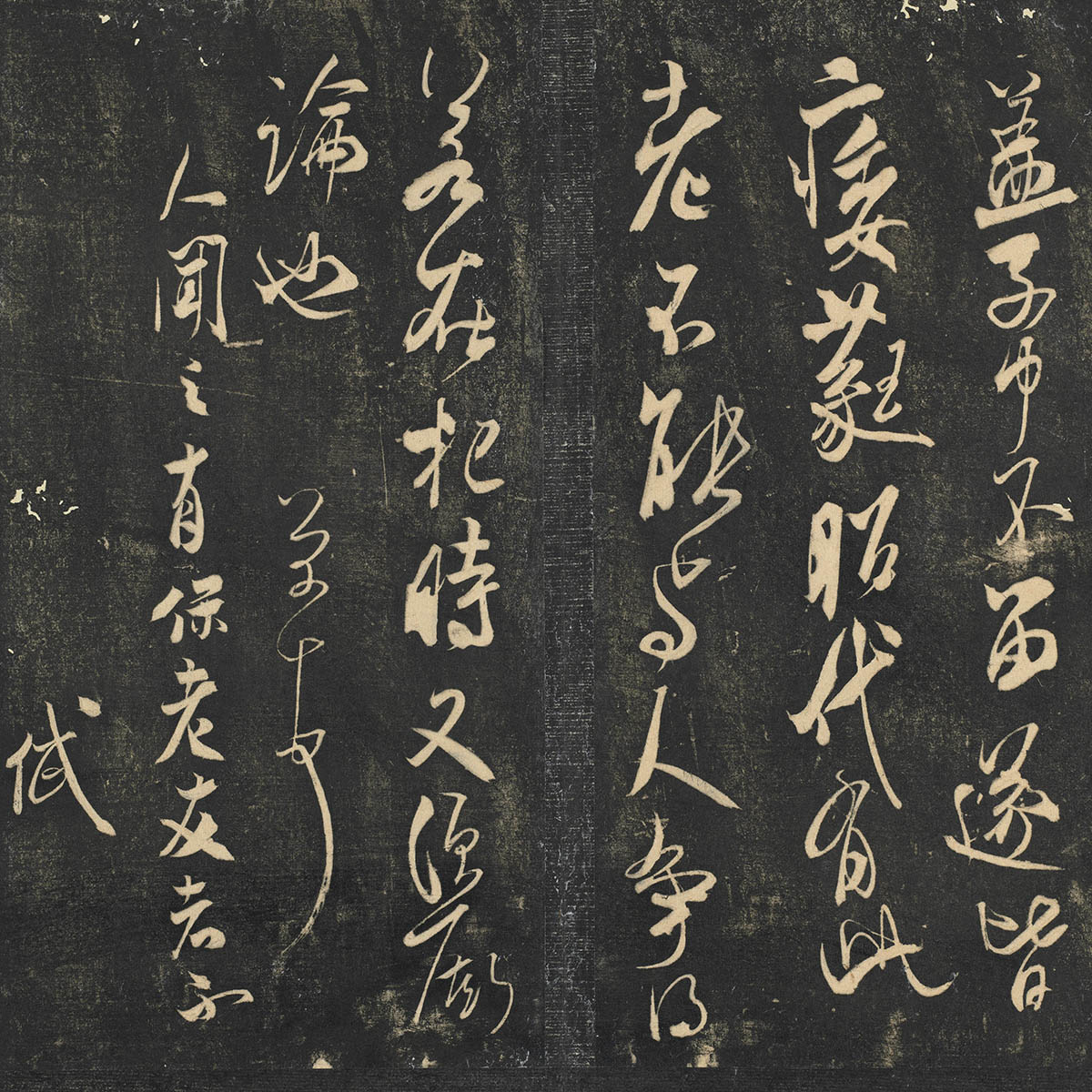

Rubbings of Calligraphic Modelbooks from the Tingyun Hall (Album 5)

Rubbings of Calligraphic Modelbooks from the Tingyun Hall (Album 5)

- Anonymous, Ming dynasty (1368-1644)

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

These rubbings made in the Ming dynasty are based on "Nine Modelbooks of Cursive Script" by the Song dynasty calligrapher Mi Fu. "Nine Modelbooks of Cursive Script" had been in the court collection of the Southern Song emperor Gaozong (1107-1187) and featured a colophon by Mi Fu's son Mi Youren (1074-1151) confirming its authenticity. Later, between the years 1537 and 1560 in the Ming dynasty, Wen Zhengming (1470-1559) and his sons Wen Peng (1497-1573) and Wen Jia (1501-1583) made a copy of Calligraphic Modelbooks from the Tingyun Hall and included the nine modelbooks in their entirety in the fifth compilation of "Calligraphy by Famous Figures of the Song." The engraving from which this rubbing derives was done by the master Zhang Jianfu (1491-1572), who carefully selected the pieces to have them carved into stone, making it a representative example of Ming dynasty engraved collectanea.

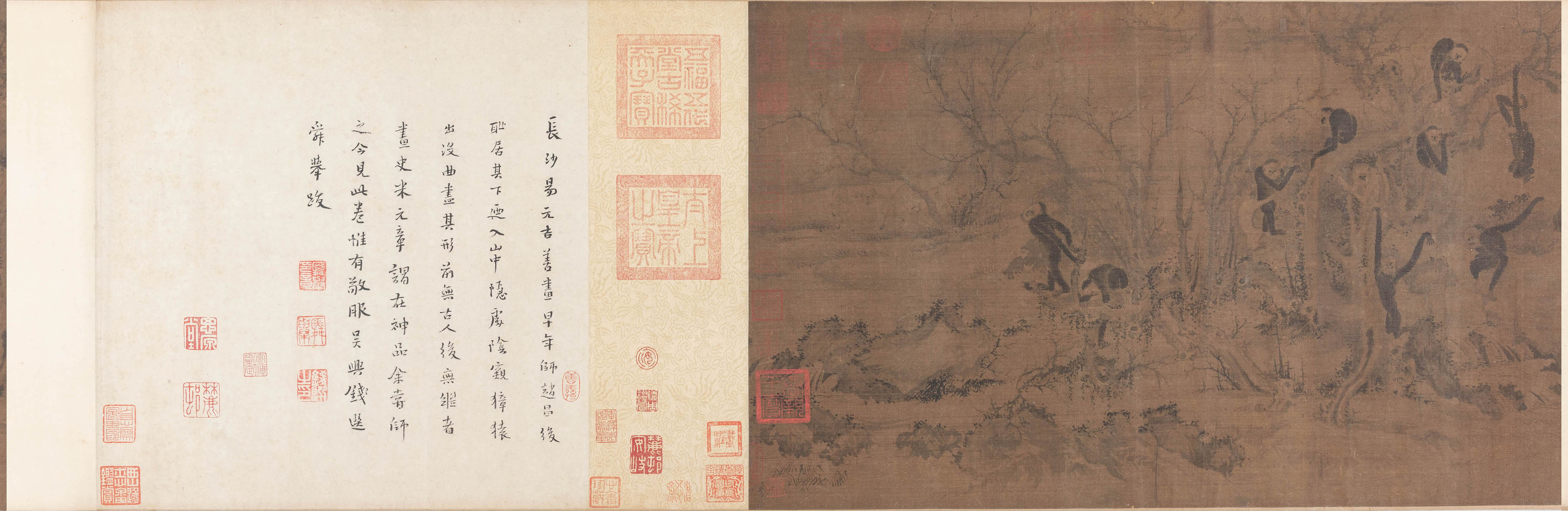

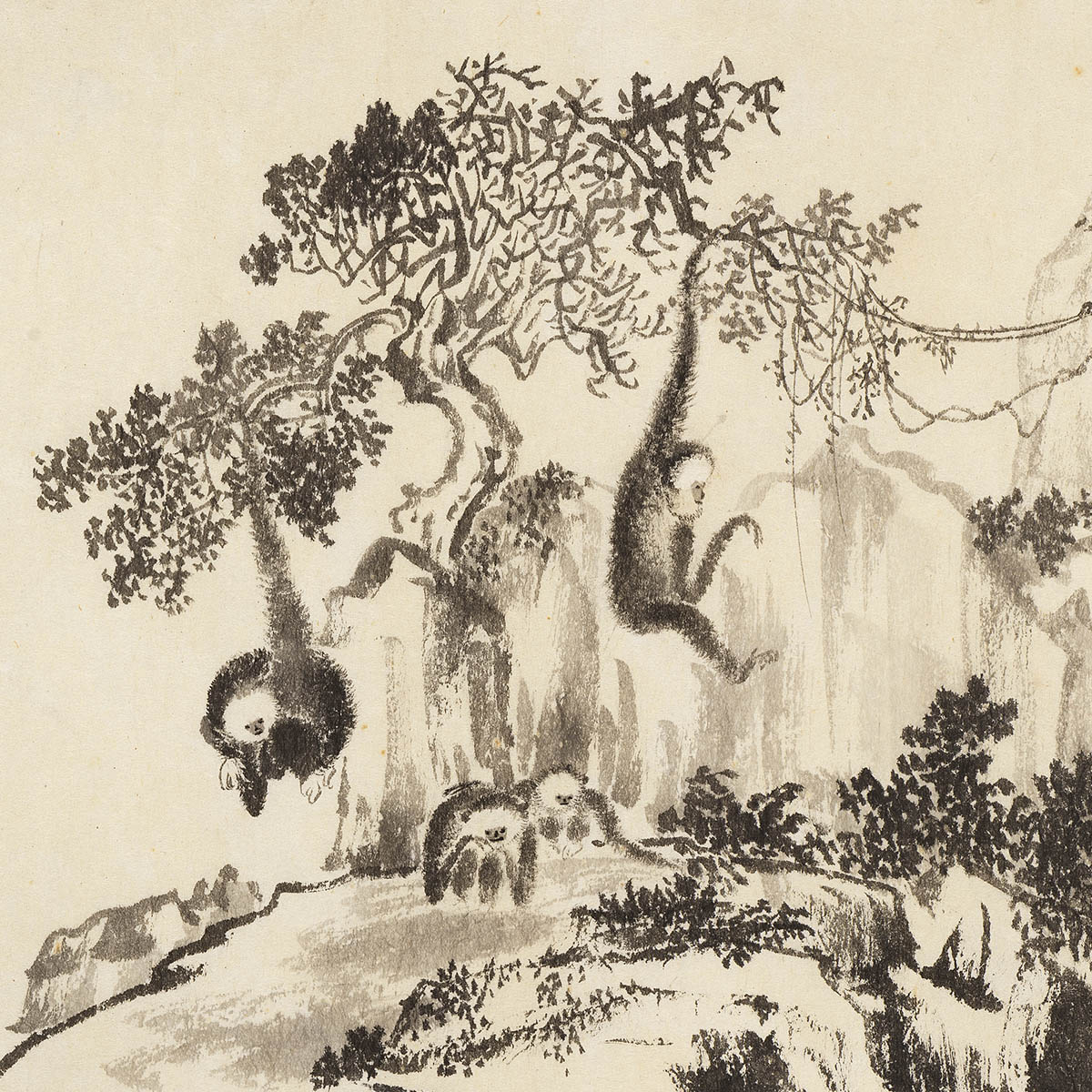

Gathering of Gibbons

Gathering of Gibbons

- Yi Yuanji (fl. latter half of the 11th c.), Song dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

This handscroll was originally part of the household collection at the residence of Prince Gong (1833-1898) in the late Qing dynasty. The painting does not have a signature, but a colophon attributes it to the Song painter Yi Yuanji. It depicts a mountain valley with trees featuring withered branches. A stream surges in the area below with a group of black gibbons rendered in long strokes of black ink and washes with blank areas for the faces. This is in contrast to the white gibbons highlighted against the ink washes. The gibbons are shown in a variety of poses and actions, such as climbing rocks, hanging from trees, or scooping up water. Only the brushwork for rendering the water indicates its later date, perhaps from the Southern Song period (1127-1279).

Yi Yuanji excelled at going into nature to experience and observe his objects of study, for which he achieved fame as a painter. He especially excelled at portraying gibbons, his renown extending to later generations as well.

Yi Yuanji excelled at going into nature to experience and observe his objects of study, for which he achieved fame as a painter. He especially excelled at portraying gibbons, his renown extending to later generations as well.

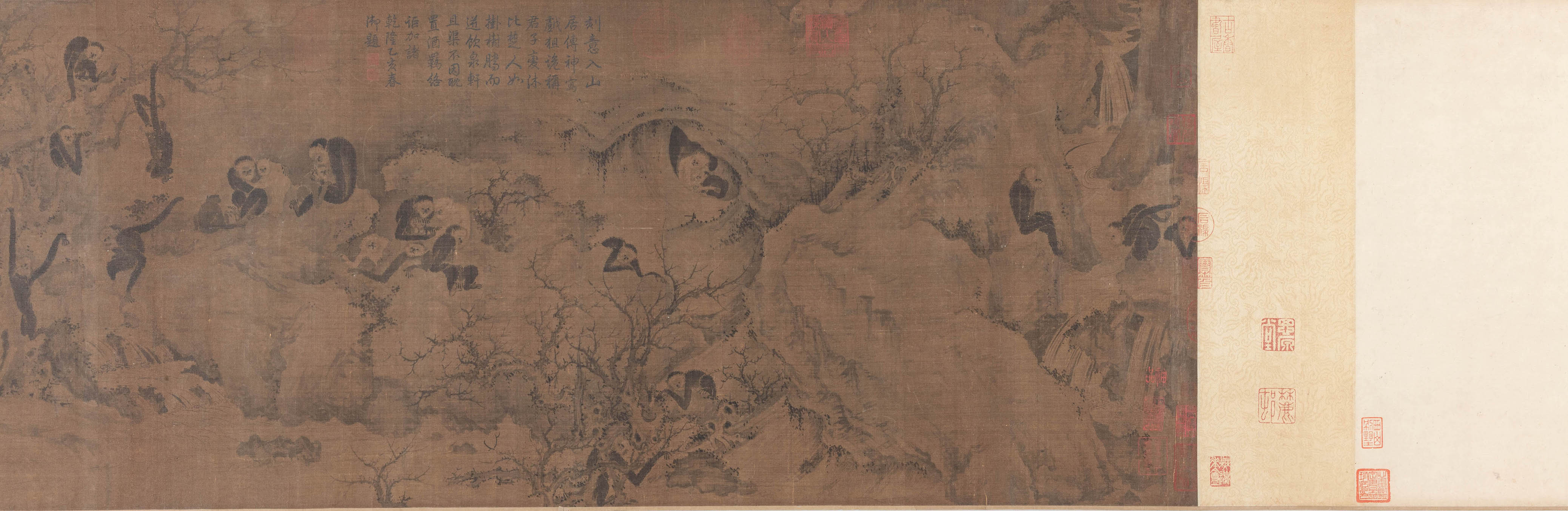

Seven Gibbons

Seven Gibbons

- Pu Ru (1896-1963), Republican period

- Entrusted to the National Palace Museum from the Cold Jade Hall

Pu Ru, also known as Pu Hsin-yu, was a member of the Qing dynasty imperial family and the grandson of the influential Yixin (Prince Gong, 1833-1898). Since childhood, Pu Ru delved into literature, calligraphy, and painting. Self-learned in the latter, his style was pure and untrammeled. Contemporaries praised his as the painter of the Republican era who best captured the essence of tradition.

In this painting entrusted to the National Palace Museum from Pu Ru's Cold Jade Hall are actually eight black gibbons and one white one among rocks and branches as they play and swing about. A stiff and slightly dry brush was used to sketch the white-faced black gibbons, while the white gibbon was rendered using abbreviated light ink in short strokes set off from the background by staining. Although the artist claimed in his inscription to have been inspired by a Yi Yuanji painting in the former collection of Prince Gong, the brushwork for the trees, rocks, and gibbons are all in his own style instead.

In this painting entrusted to the National Palace Museum from Pu Ru's Cold Jade Hall are actually eight black gibbons and one white one among rocks and branches as they play and swing about. A stiff and slightly dry brush was used to sketch the white-faced black gibbons, while the white gibbon was rendered using abbreviated light ink in short strokes set off from the background by staining. Although the artist claimed in his inscription to have been inspired by a Yi Yuanji painting in the former collection of Prince Gong, the brushwork for the trees, rocks, and gibbons are all in his own style instead.

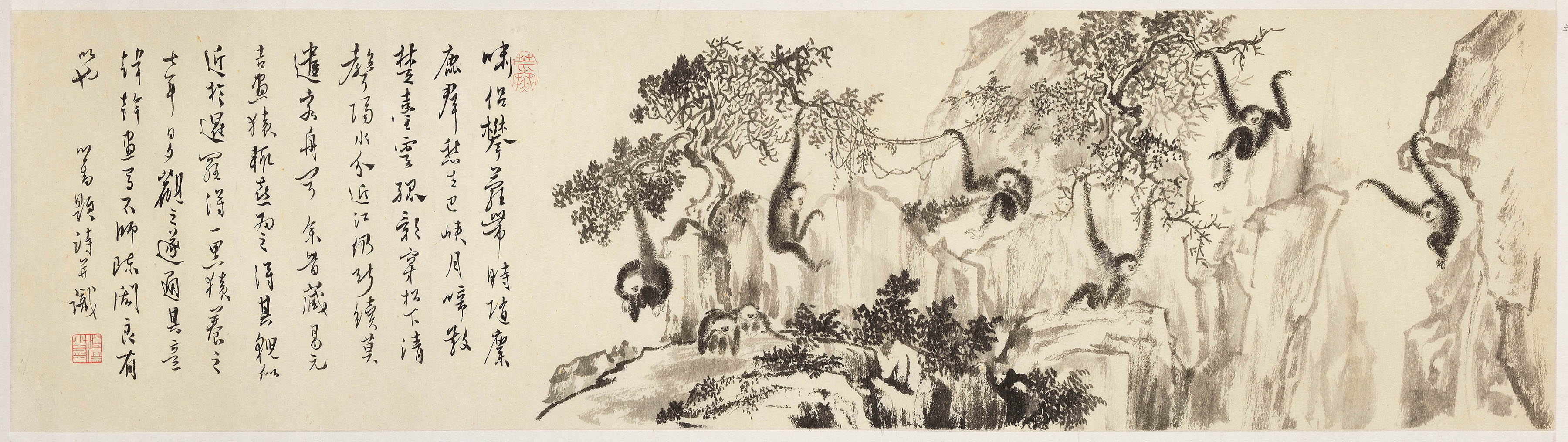

Autumn Colors on Mountains and Streams

Autumn Colors on Mountains and Streams

- Huizong (1082-1135), Song dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in October 2012 as a Significant Historical Artifact

In this painting are shoals and trees extending from the foreground to the layered peaks and ridges in the background. The light washes of ink embellish this rustic water scene enveloped in mists, creating an evocative landscape imbued with lyricism. Although this hanging scroll features the cipher and "Yushu" seal of the Northern Song emperor Huizong (r. 1100-1126), it does not include his oft-seen signature seal and therefore may have been forged. The scenery in this composition is concentrated in the left half of the painting, which also differs from the monumental landscape style with a central peak rising majestically in the middle frequently found in the Northern Song period.

Judging from the style, this work probably dates to the early Southern Song period (1127-1279). The brushwork is fine and delicate, combining the use of brush and ink associated with the school of Li Cheng and Guo Xi while exhibiting the spirit harmony of light ink used in literati painting. A representative example of the transition from Northern Song to Southern Song landscape painting, it is significant work in the history of Chinese art.

Judging from the style, this work probably dates to the early Southern Song period (1127-1279). The brushwork is fine and delicate, combining the use of brush and ink associated with the school of Li Cheng and Guo Xi while exhibiting the spirit harmony of light ink used in literati painting. A representative example of the transition from Northern Song to Southern Song landscape painting, it is significant work in the history of Chinese art.

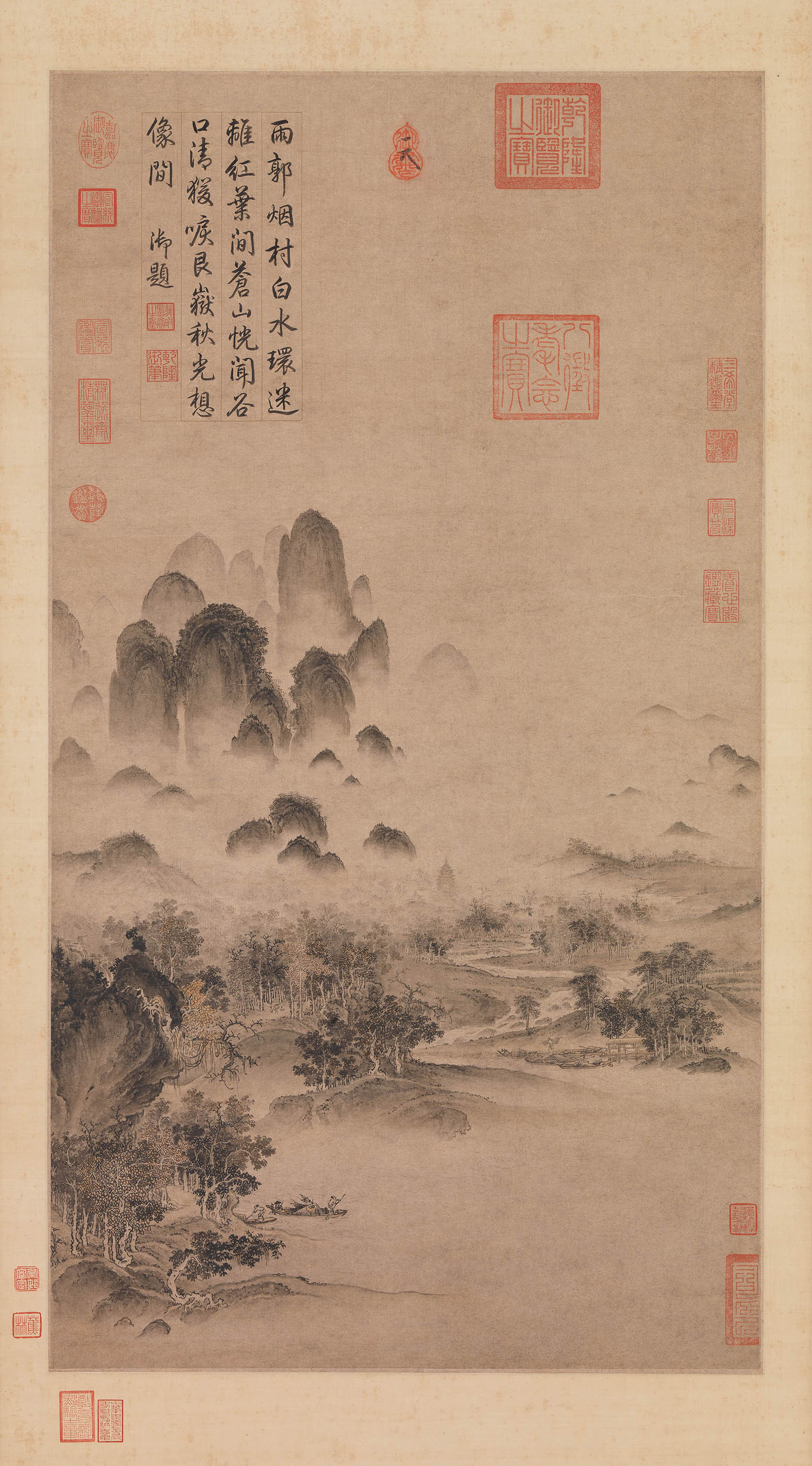

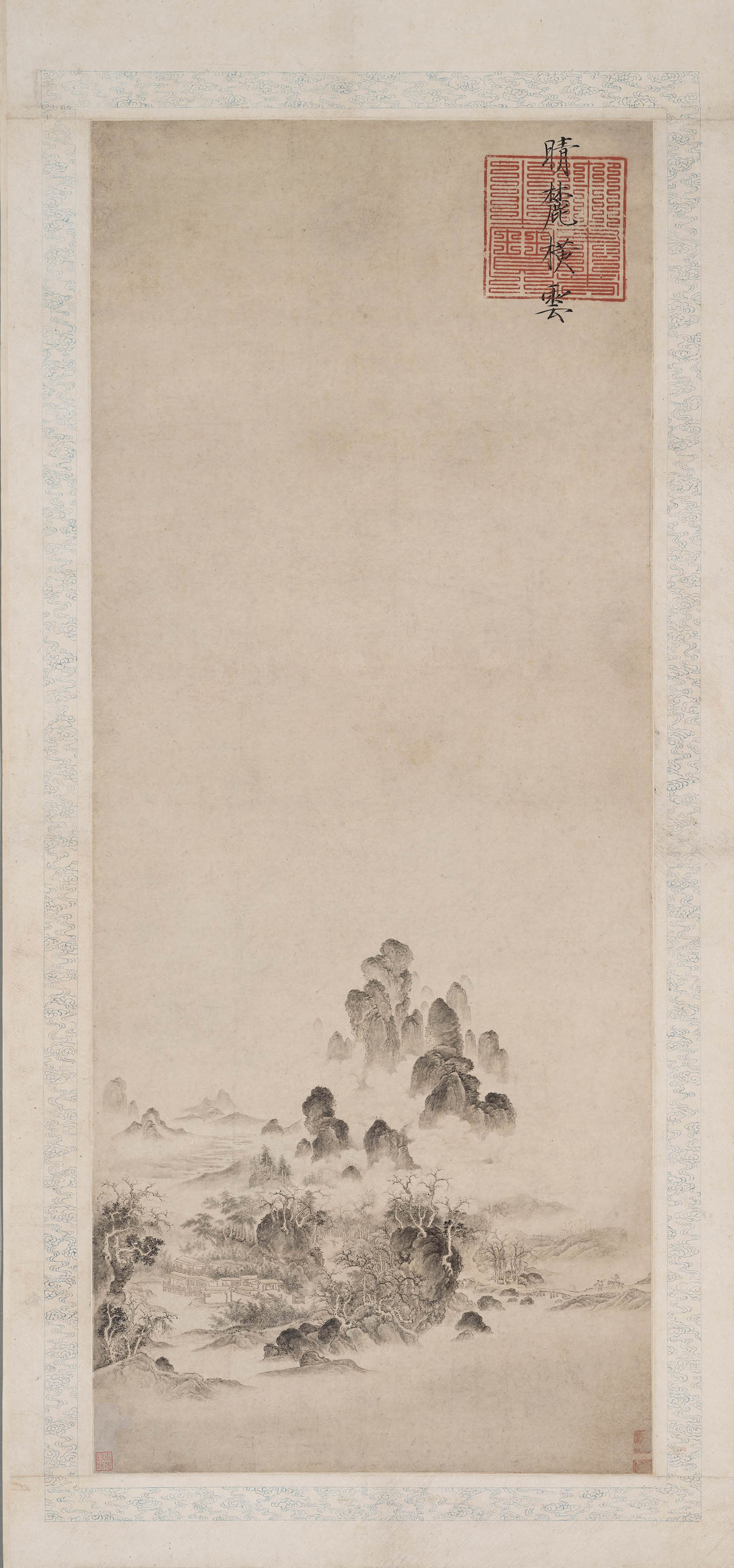

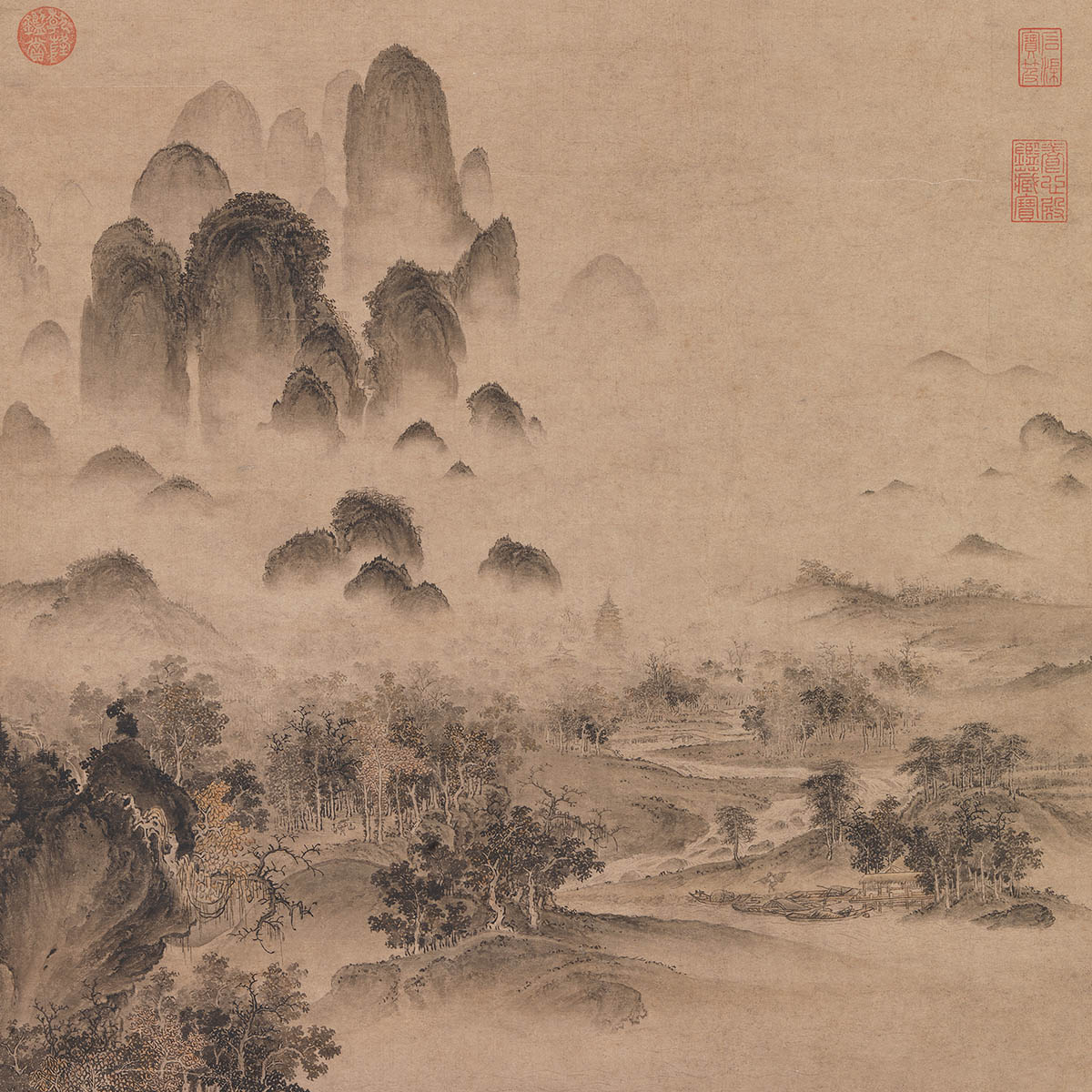

Clearing Foothills Surrounded by Clouds

Clearing Foothills Surrounded by Clouds

- Huizong (1082-1135), Song dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

The scenery and its arrangement in this work are similar to "Autumn Colors on Mountains and Streams" given to Huizong in the National Palace Museum. However, the landscape is concentrated in the lower middle with the rest of the composition left blank. The peaks are shaped like clouds and similar to the style of Li Cheng and Guo Xi, but the brushwork is exacting and the textured washes quite refined, which differs from the dramatic changes in line thickness found in the Li-Guo style. Scholarly opinion is that this work follows the Li-Guo tradition as practiced in the Jin dynasty (1215-1234).

In the upper right part of the painting is a four-character inscription for the title done in the "slender-gold" script of Emperor Huizong. However, the style of writing is slightly flaccid, and the Huizong seal "Yushu zhibao" also suspect, suggesting a later artist working in emulation.

In the upper right part of the painting is a four-character inscription for the title done in the "slender-gold" script of Emperor Huizong. However, the style of writing is slightly flaccid, and the Huizong seal "Yushu zhibao" also suspect, suggesting a later artist working in emulation.

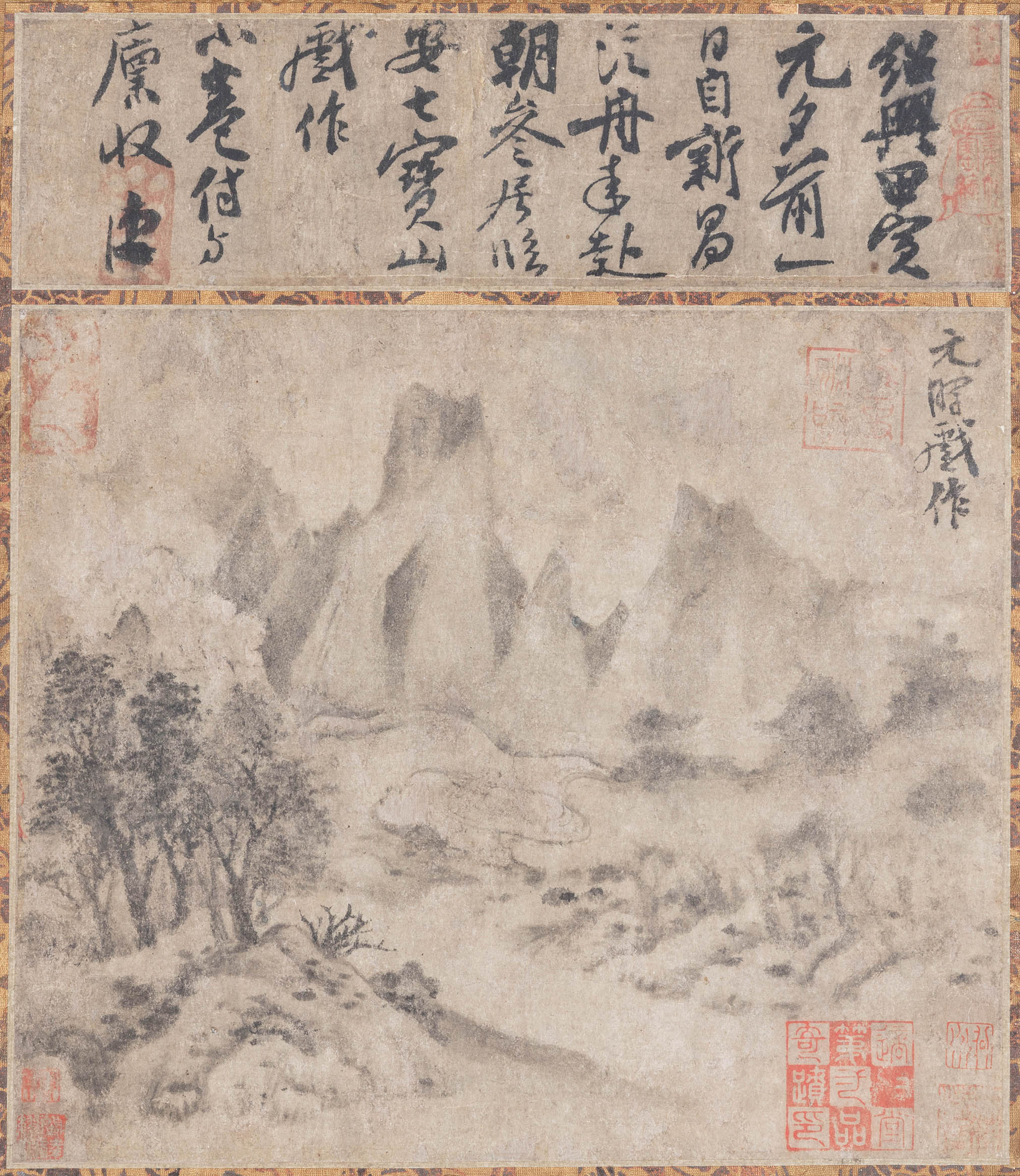

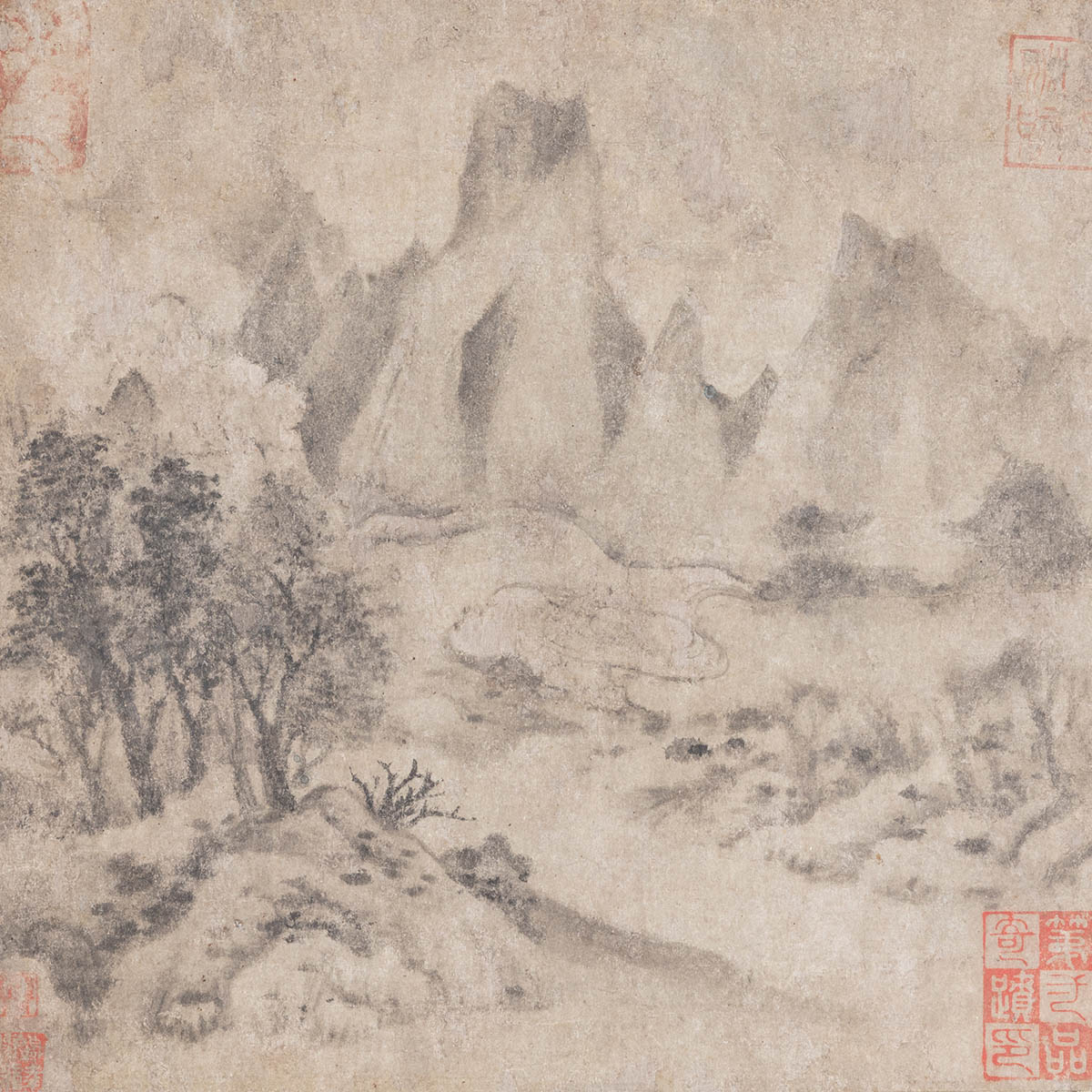

Distant Peaks and Clearing Clouds

Distant Peaks and Clearing Clouds

- Mi Youren (1074-1151), Song dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Mi Youren (style name Yuanhui) was the eldest son of the Northern Song calligrapher-connoisseur Mi Fu (1052-1108). In painting and calligraphy, he followed in his father foosteps and achieved fame equal to him. Both excelled in using shaded ink washes to render the watery mist-filled scenery of the Jiangnan region. Their style of painting became later known as "Mi-family cloudy mountains" or "Mi-family landscape."

Surviving paintings by Mi Youren are rare, and this is one of the more exceptional ones. Done in light shades of ink on paper, it is signed, "Playfully done by Yuanhui." According to the inscription attached to the painting also by Mi Youren, the scenery depicted here represents the landscape that he saw when boating from Xinchang on his return to Qibaoshan in Lin'an (modern Hangzhou).

Surviving paintings by Mi Youren are rare, and this is one of the more exceptional ones. Done in light shades of ink on paper, it is signed, "Playfully done by Yuanhui." According to the inscription attached to the painting also by Mi Youren, the scenery depicted here represents the landscape that he saw when boating from Xinchang on his return to Qibaoshan in Lin'an (modern Hangzhou).

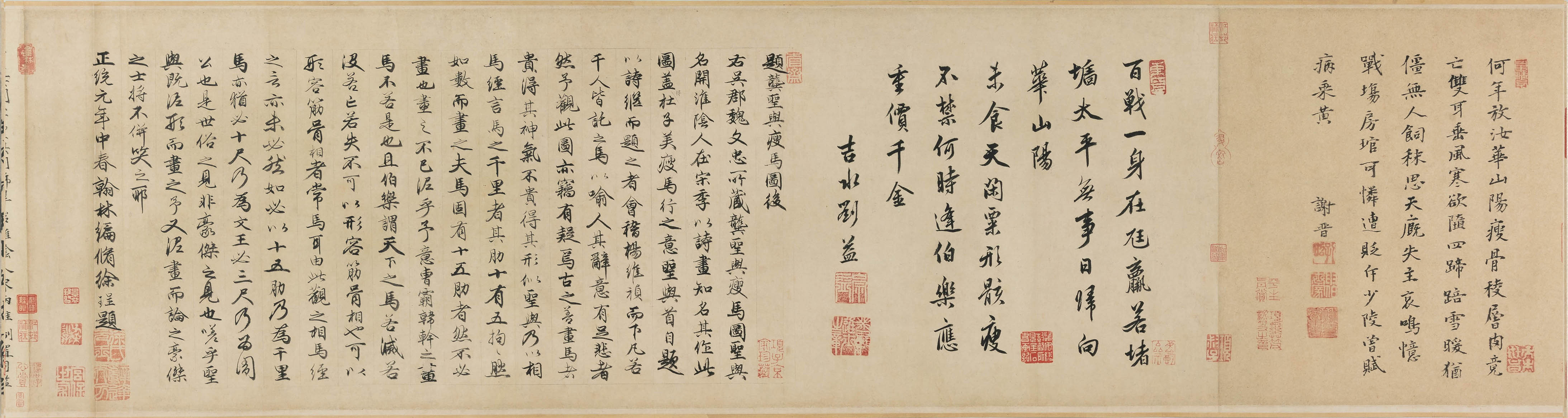

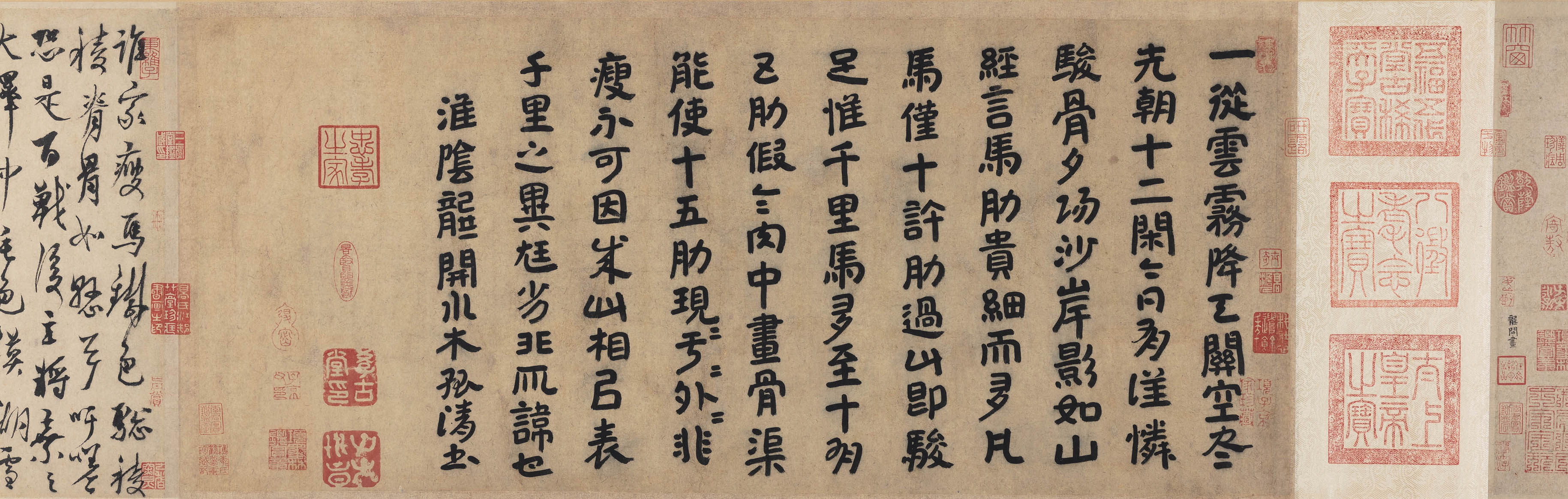

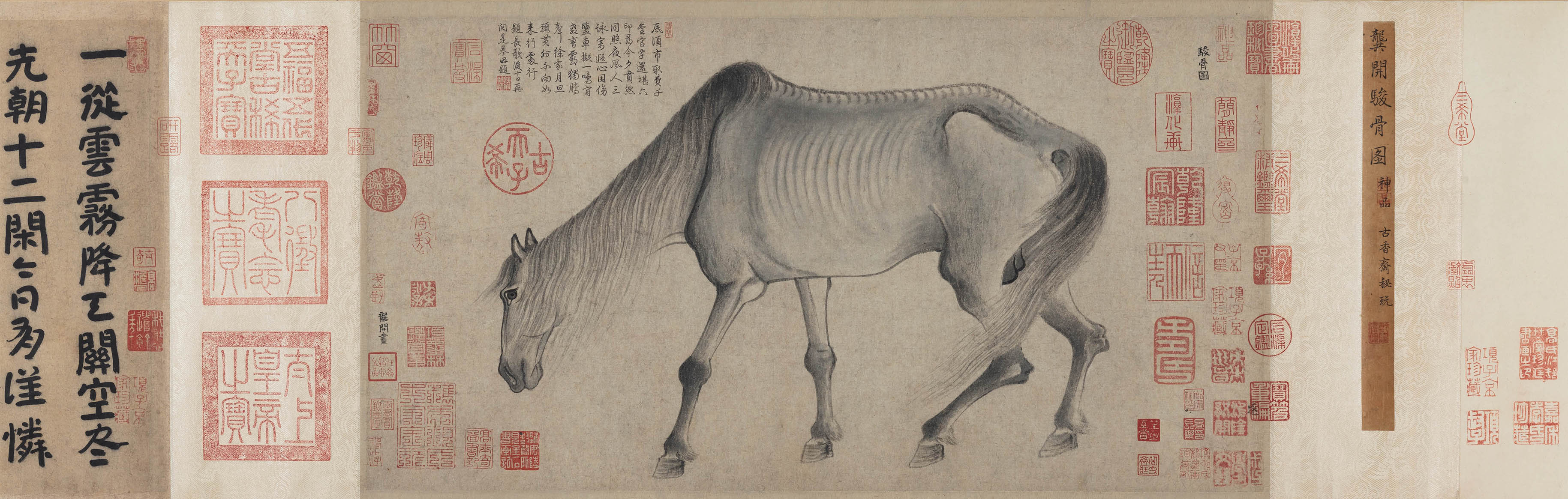

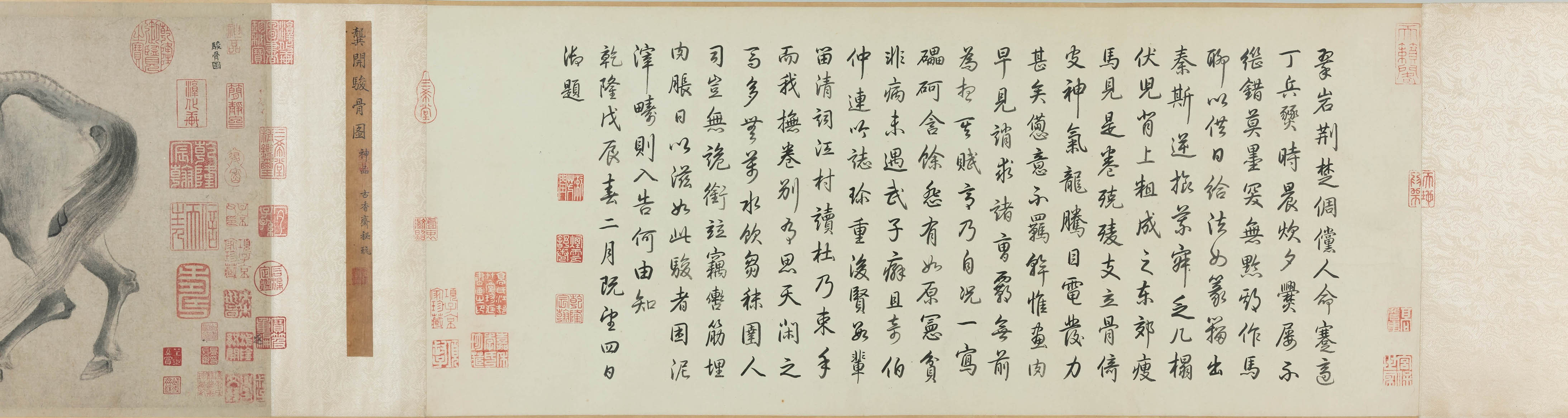

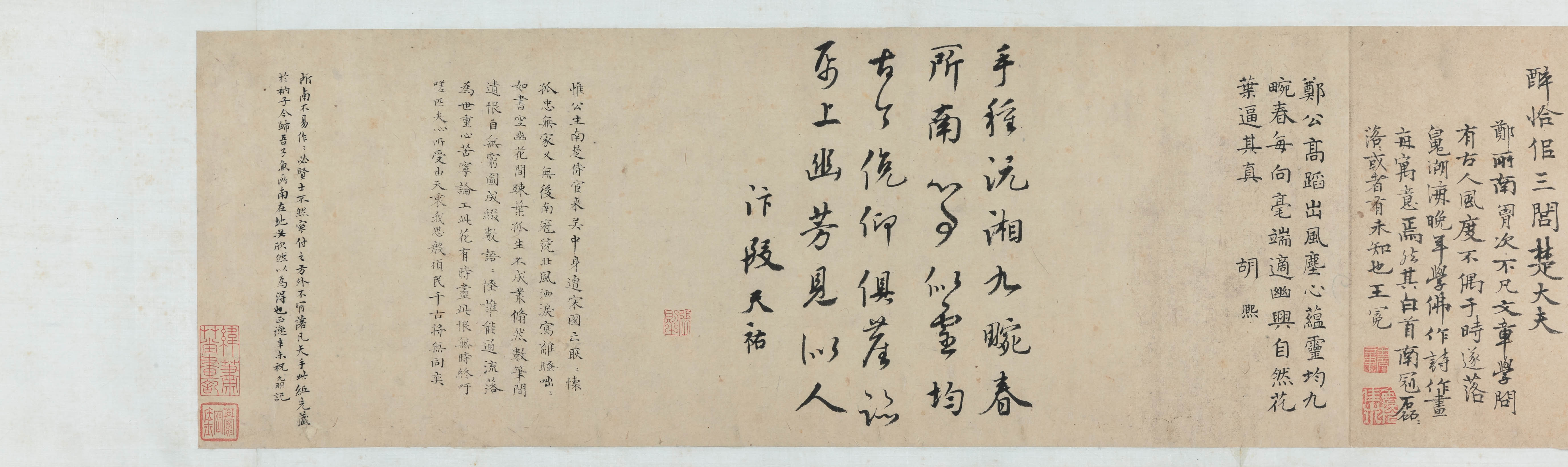

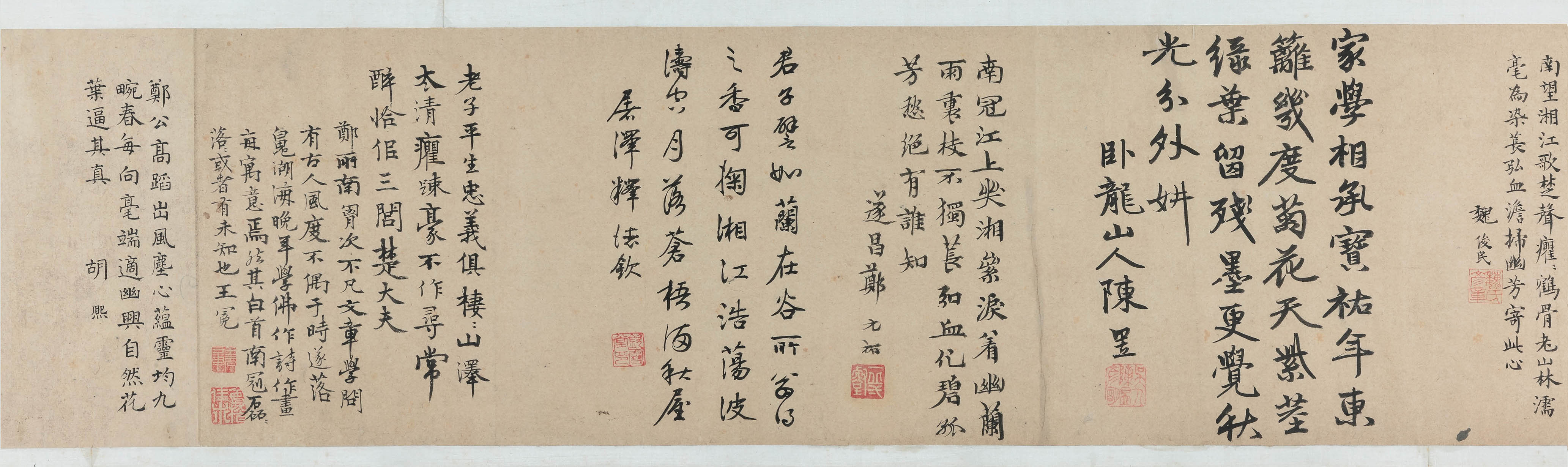

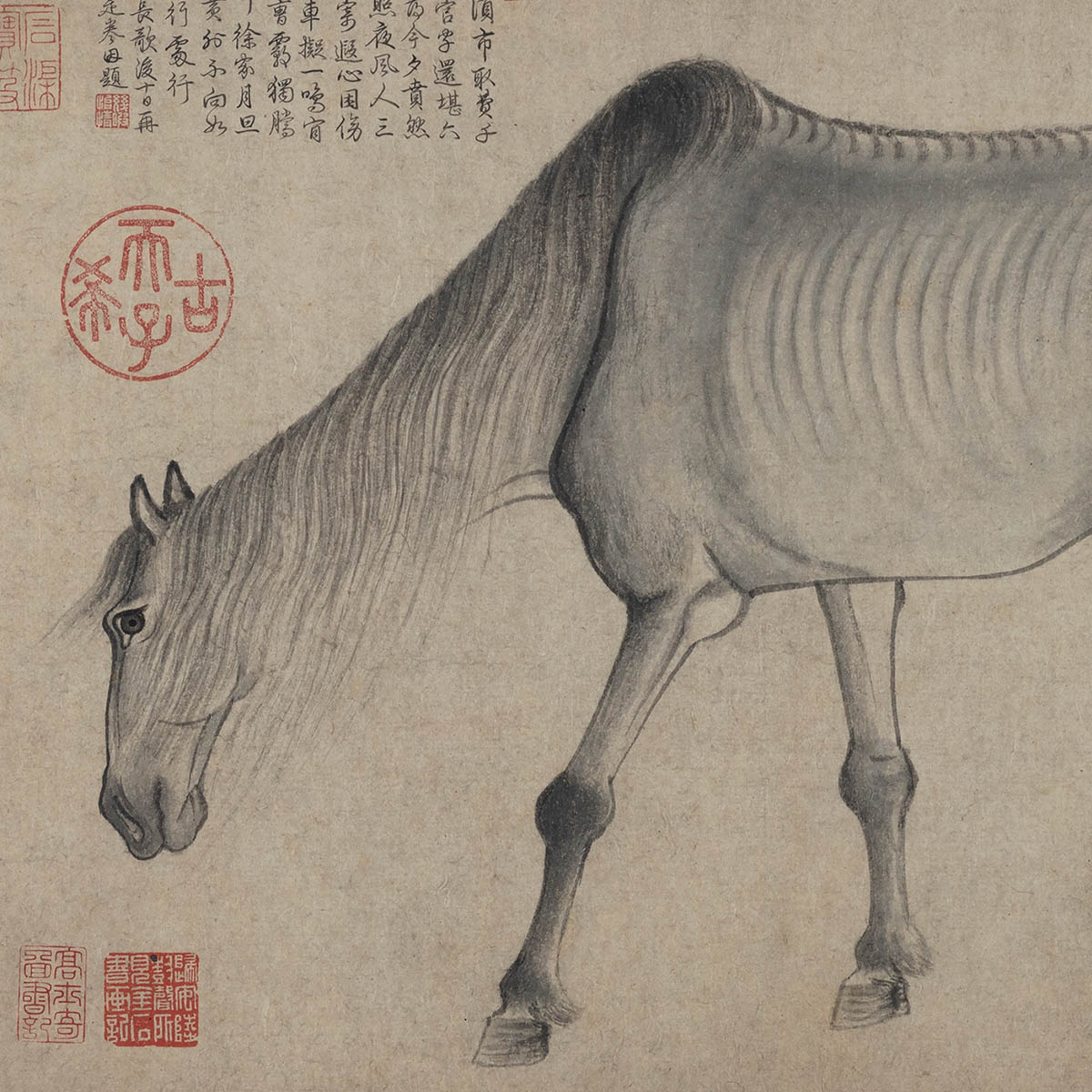

Emaciated Horse

Emaciated Horse

- Gong Kai (1222-?), Song dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Gong Kai was a native of Huaiyin (modern Huai'an, Jiangsu). At the fall of the Southern Song, he became a recluse and did not seek office in the Mongol Yuan dynasty, using his talents in the literary arts as well as painting and calligraphy to express grief and nostalgia for the dynasty of old.

This painting depicts a bony emaciated horse standing against a blank background. Not only does its spine clearly stand out, the hip and rib bones are also quite evident. Nonetheless, a hint of the horse's character can be seen in the spirit of its eyes, which exhibit an inner strength despite the posture. The poem Gong Kai inscribed on the scroll reads, "Nowadays who will pity this bony stallion, whose shadow is like a mountain in the sunset on sandy banks?" It echoes the horse's image in the painting and expresses the author's misgivings about the final collapse of the Song dynasty.

This painting depicts a bony emaciated horse standing against a blank background. Not only does its spine clearly stand out, the hip and rib bones are also quite evident. Nonetheless, a hint of the horse's character can be seen in the spirit of its eyes, which exhibit an inner strength despite the posture. The poem Gong Kai inscribed on the scroll reads, "Nowadays who will pity this bony stallion, whose shadow is like a mountain in the sunset on sandy banks?" It echoes the horse's image in the painting and expresses the author's misgivings about the final collapse of the Song dynasty.

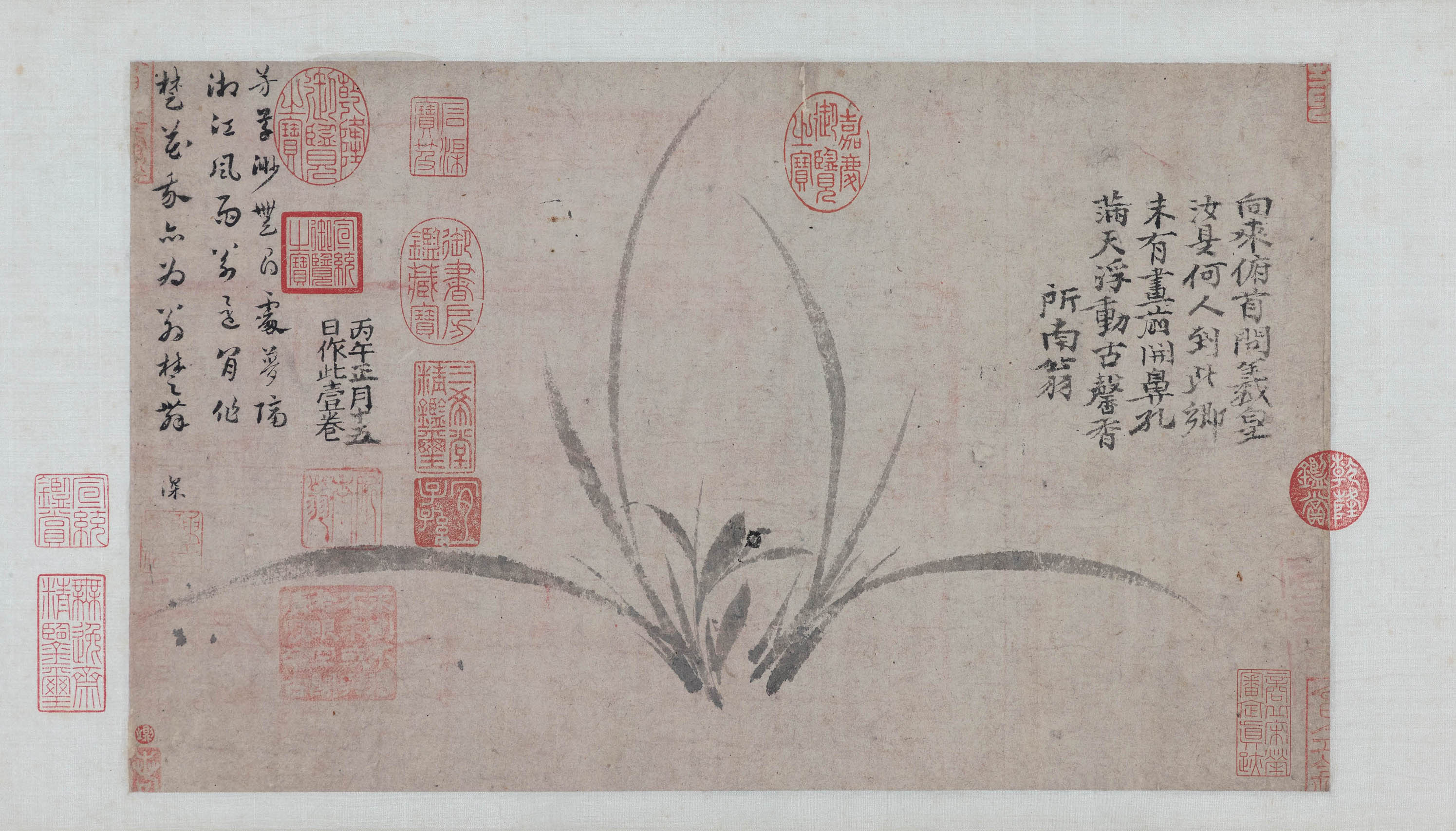

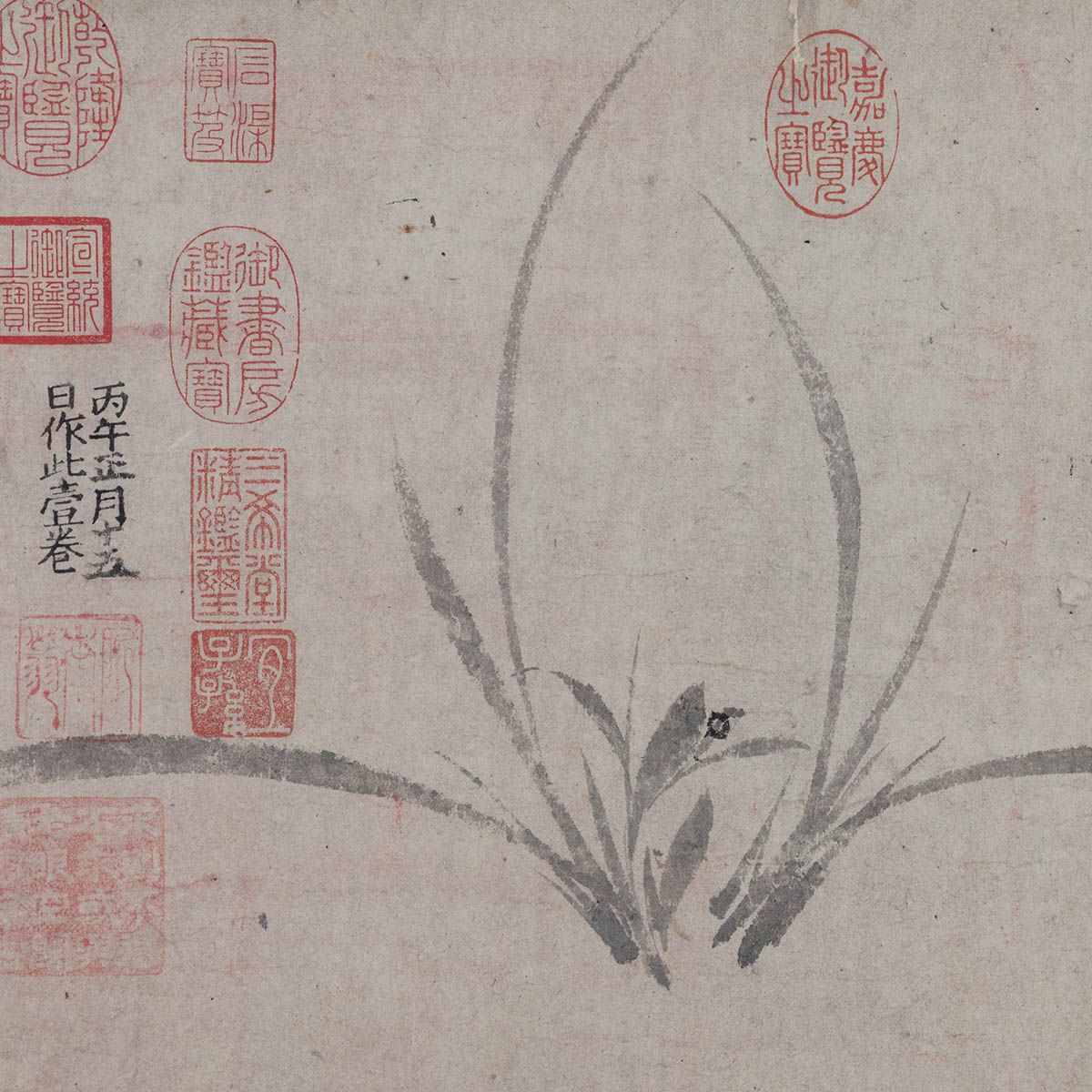

Ink Orchid

Ink Orchid

- Zheng Sixiao (1241-1318), Song dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Zheng Sixiao (alternate dates: 1239-1316) was a Song dynasty loyalist who lived into the early Yuan dynasty. A poet and a painter, this work of his depicts an orchid with a few blades in a very succinct manner and is his most famous surviving one. Most painters of orchids choose to render the slender blades crisscrossing in different patterns. Zheng, on the other hand, depicted a solitary orchid blossom here in very light shades of ink almost symmetrically with a few stems and shorter blades, creating a sense of pure archaism in its individual strength. His signature at the left reads, "This handscroll was done on the fifteenth day of the first lunar month in the ‘bingwu' year (1306).'" Except for the characters "first" and "fifteenth," the others appear to be printed in ink, which is quite unusual, because it suggests that Zheng mass-produced this kind of painting of "orchid without roots."

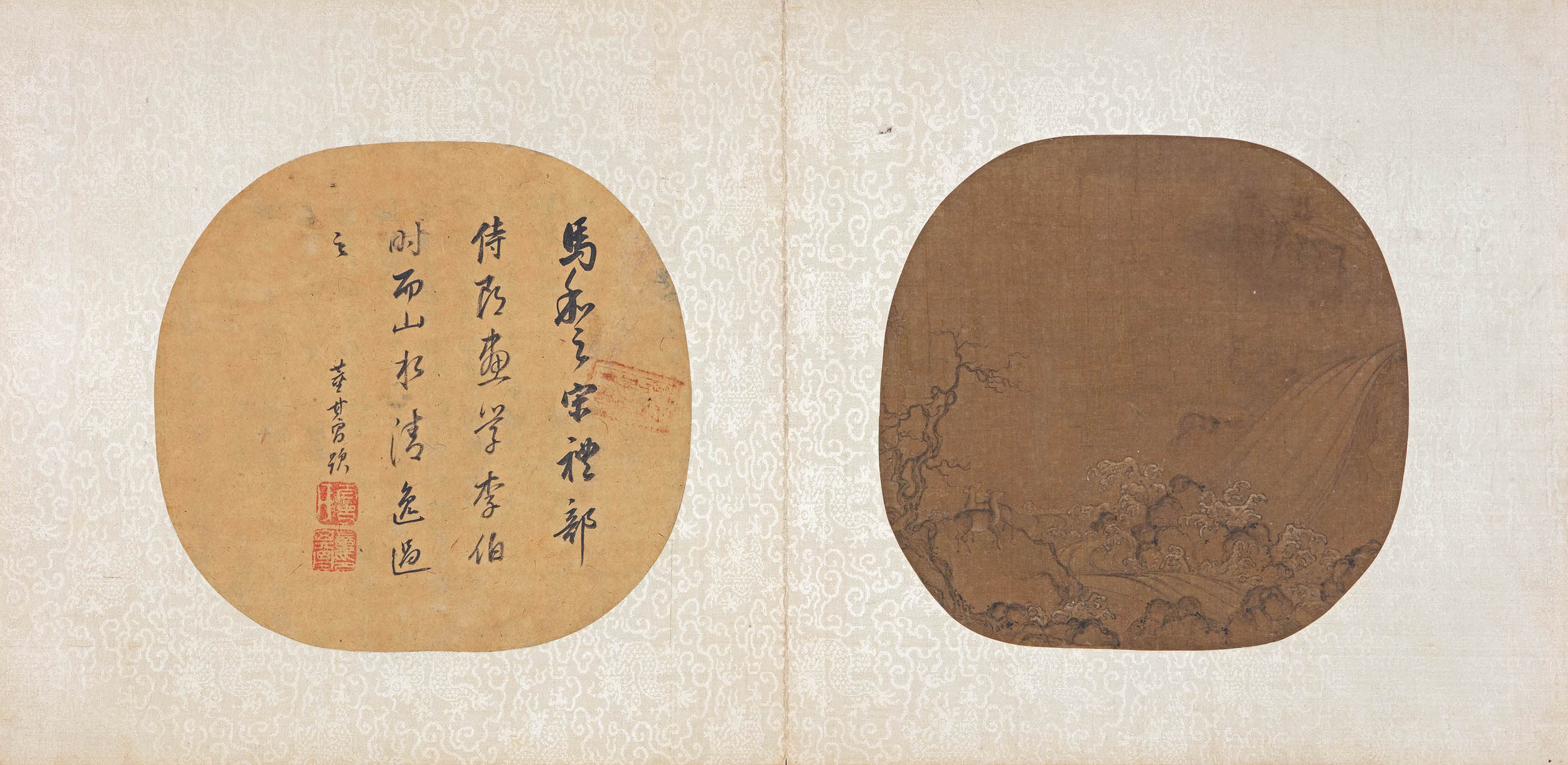

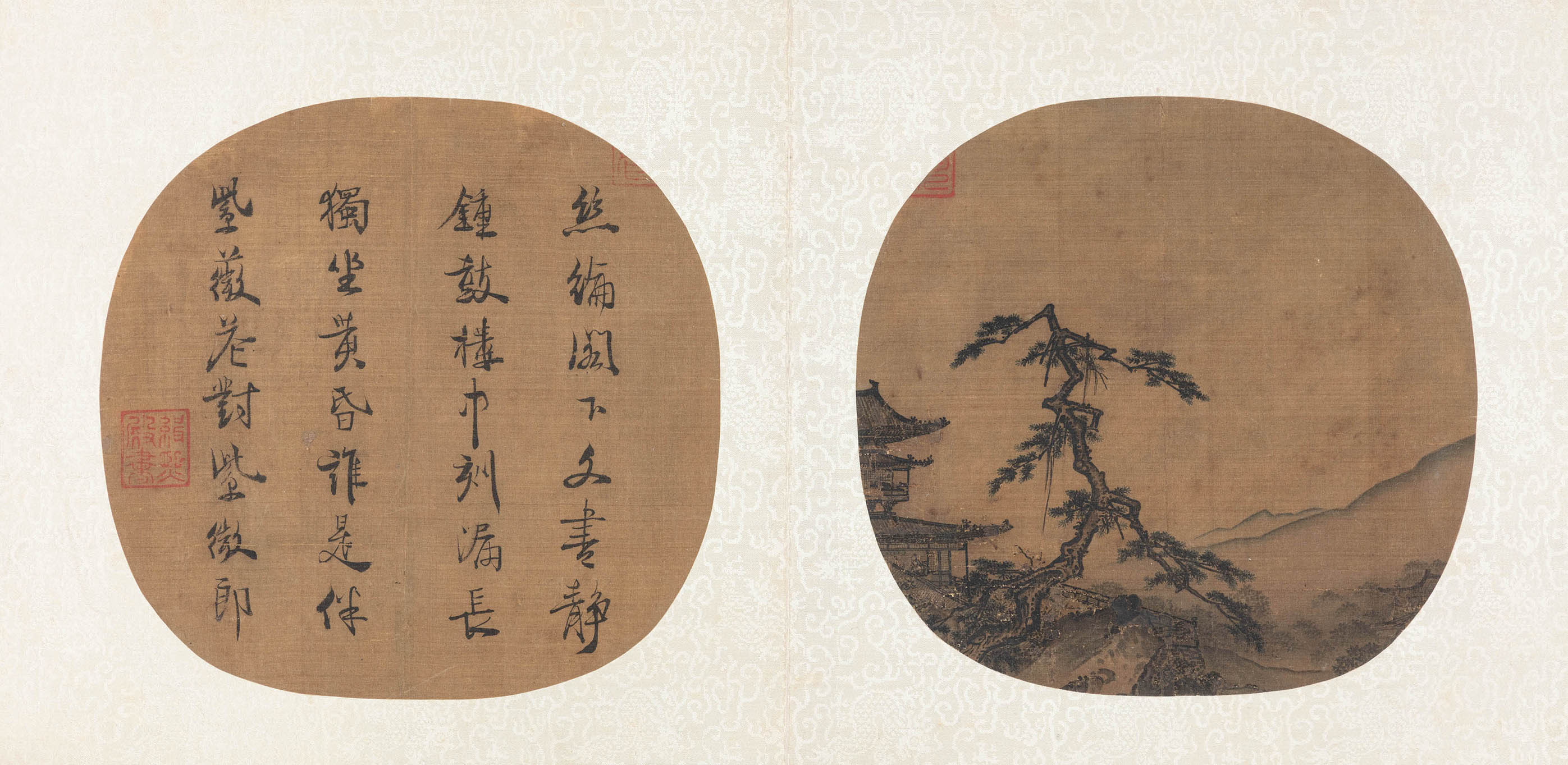

Album of Precious Paintings by Famous Sages

Album of Precious Paintings by Famous Sages

- Various artists, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

This album contains twelve leaves, of which five Song dynasty paintings have been loaned for display in this exhibition. All originally round fans later remounted in the current format, their titles are "Oxherding" (leaf 4), "Solitary Residence by a Lakeshore" (leaf 5), "Deer Roaming by a Waterfall" (leaf 6, with an opposing leaf of calligraphy by Dong Qichang), "Viewing a Waterfall" (leaf 7), and "Pavilion Among Ancient Pines" (leaf 10, with an opposing leaf by the Southern Song emperor Lizong).

"Solitary Residence by a Lakeshore," "Viewing a Waterfall," and "Pavilion Among Ancient Pines" are paintings in the style of the Southern Song court painters Ma Yuan (fl. 1189-1225) and Xia Gui (fl. 1180-1230). According to a record in Reflections on Painting and Calligraphy by Li Zuoxian in the late Qing dynasty, the entire album had first been in the collection of Chen Shouqing before being acquired by Wanyan Jingxian (1876-1926). Then, before entering the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, it had been in the collections of Takei Ayazou (1871-1932) and Fusajirō Abe (1868-1937).

"Solitary Residence by a Lakeshore," "Viewing a Waterfall," and "Pavilion Among Ancient Pines" are paintings in the style of the Southern Song court painters Ma Yuan (fl. 1189-1225) and Xia Gui (fl. 1180-1230). According to a record in Reflections on Painting and Calligraphy by Li Zuoxian in the late Qing dynasty, the entire album had first been in the collection of Chen Shouqing before being acquired by Wanyan Jingxian (1876-1926). Then, before entering the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, it had been in the collections of Takei Ayazou (1871-1932) and Fusajirō Abe (1868-1937).

Heavenly King Protecting the Buddhist Law

Heavenly King Protecting the Buddhist Law

- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Deities who protect the Buddhist teachings refer to divine figures upholding the doctrine and protecting all living beings. The belief in such deities who guard the Buddhist law includes a large pantheon of spiritual figures, the Heavenly Kings being one of the most important of these deities. The appearance of such guardian deities varies considerably, the weapons and religious objects they carry symbolizing their function of eradicating evil and defending the Buddhist lineage. They also came to represent wisdom and wealth, thereby adding to their auspicious significance.

The figures that appear in this painting have various religious paraphernalia. Though rendered in exceptional detail, the figures differ from the heavenly kings protecting the Buddhist law seen in cave and temple paintings that survive today.

The figures that appear in this painting have various religious paraphernalia. Though rendered in exceptional detail, the figures differ from the heavenly kings protecting the Buddhist law seen in cave and temple paintings that survive today.

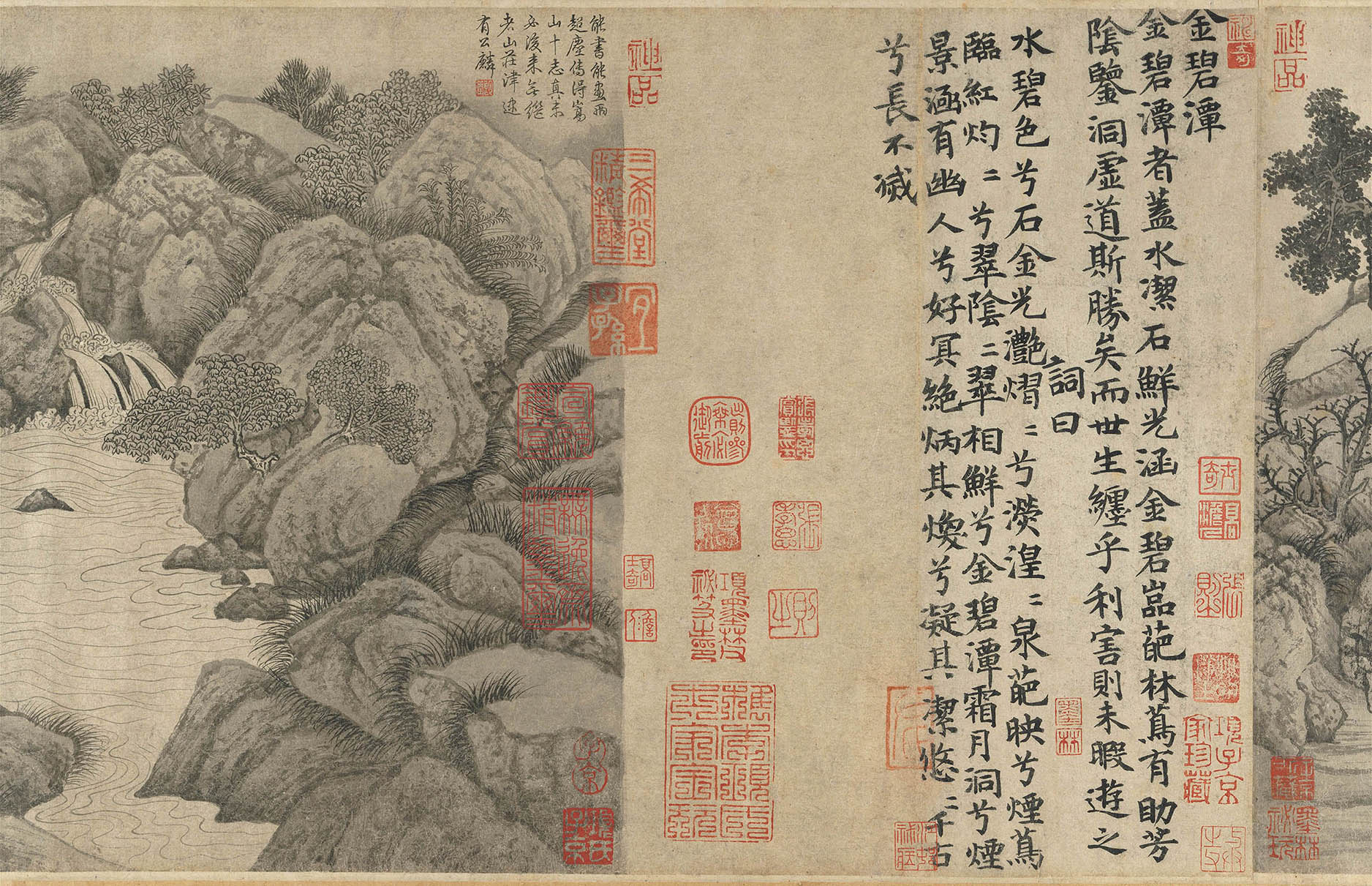

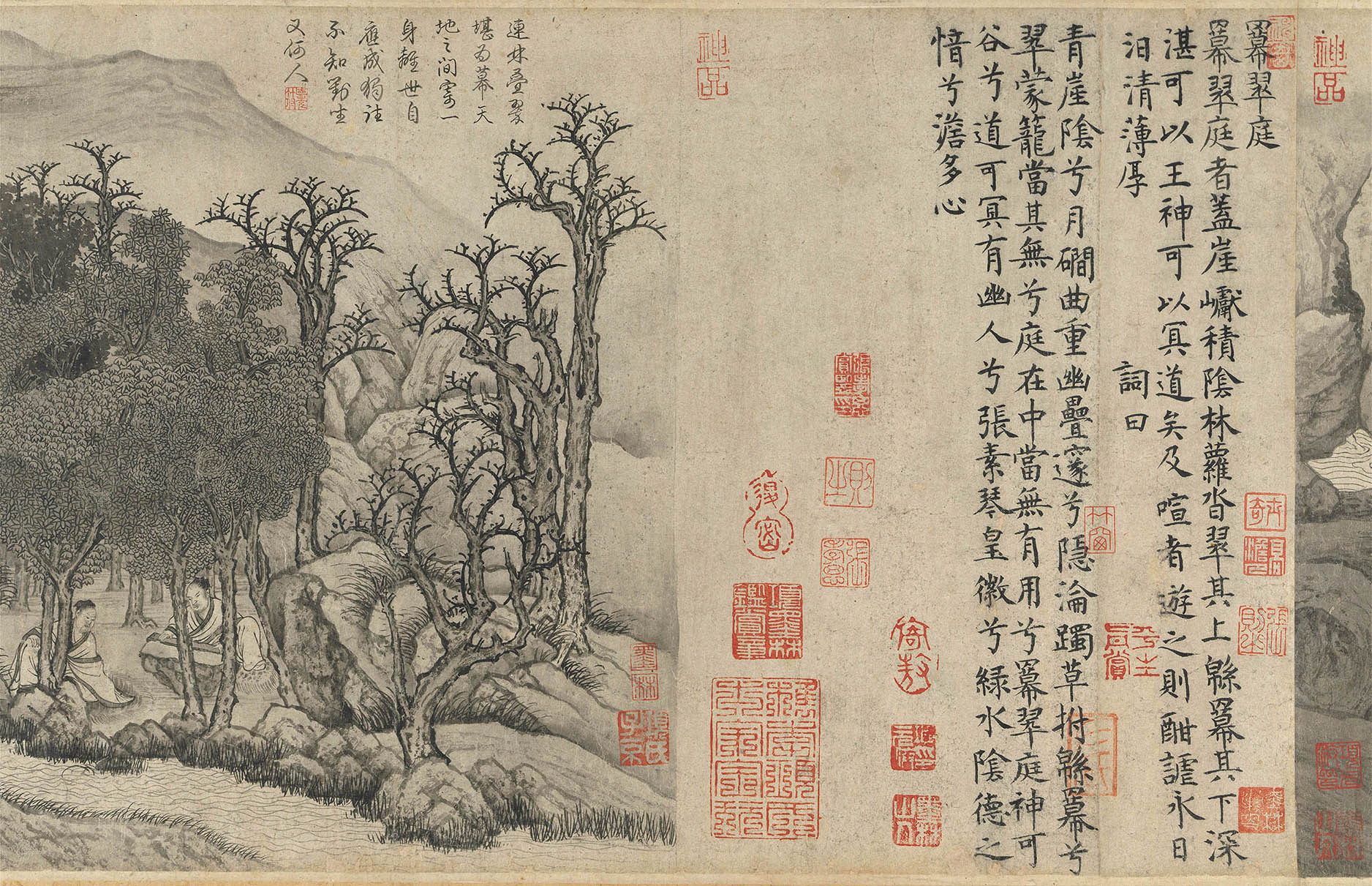

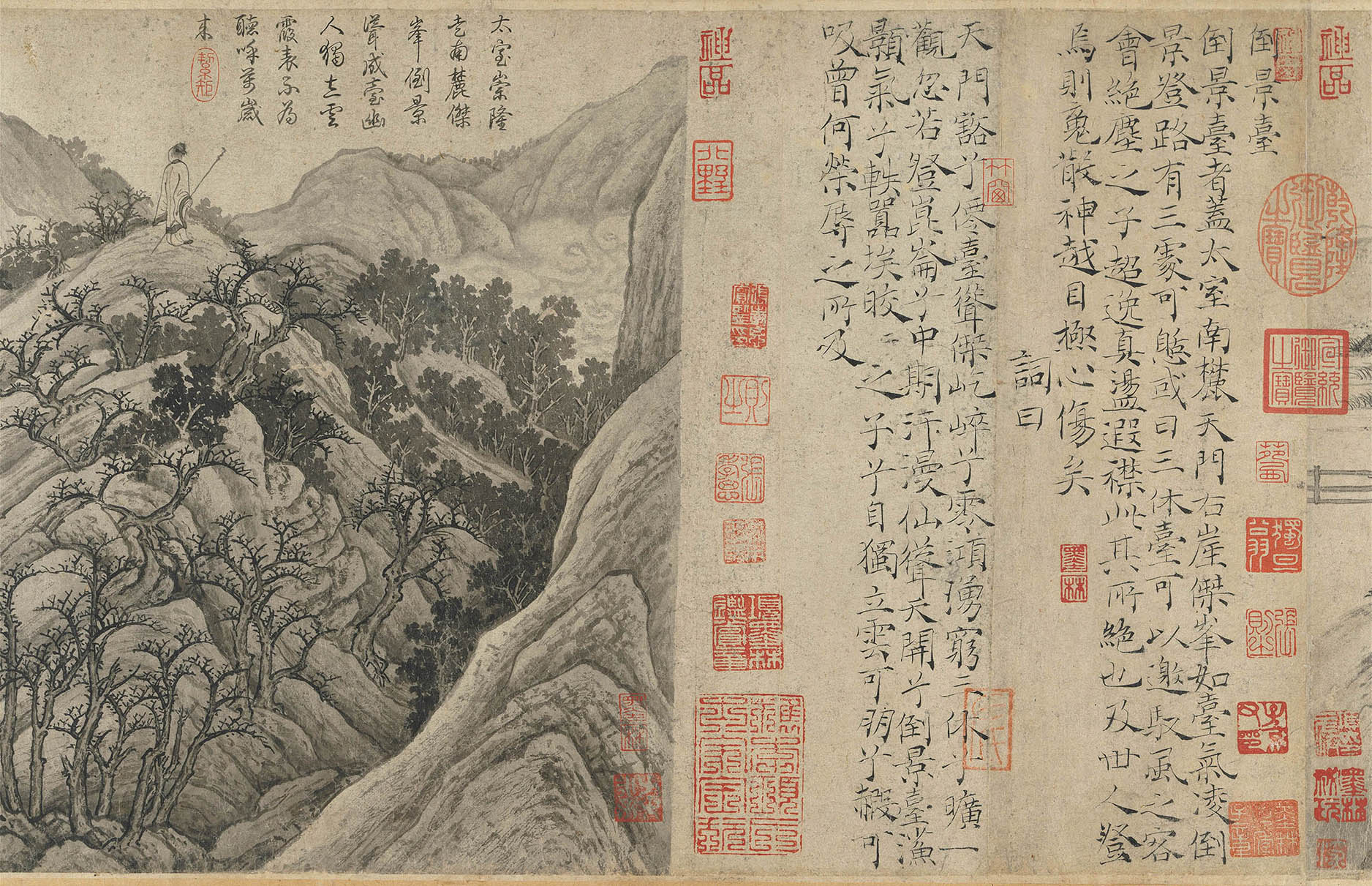

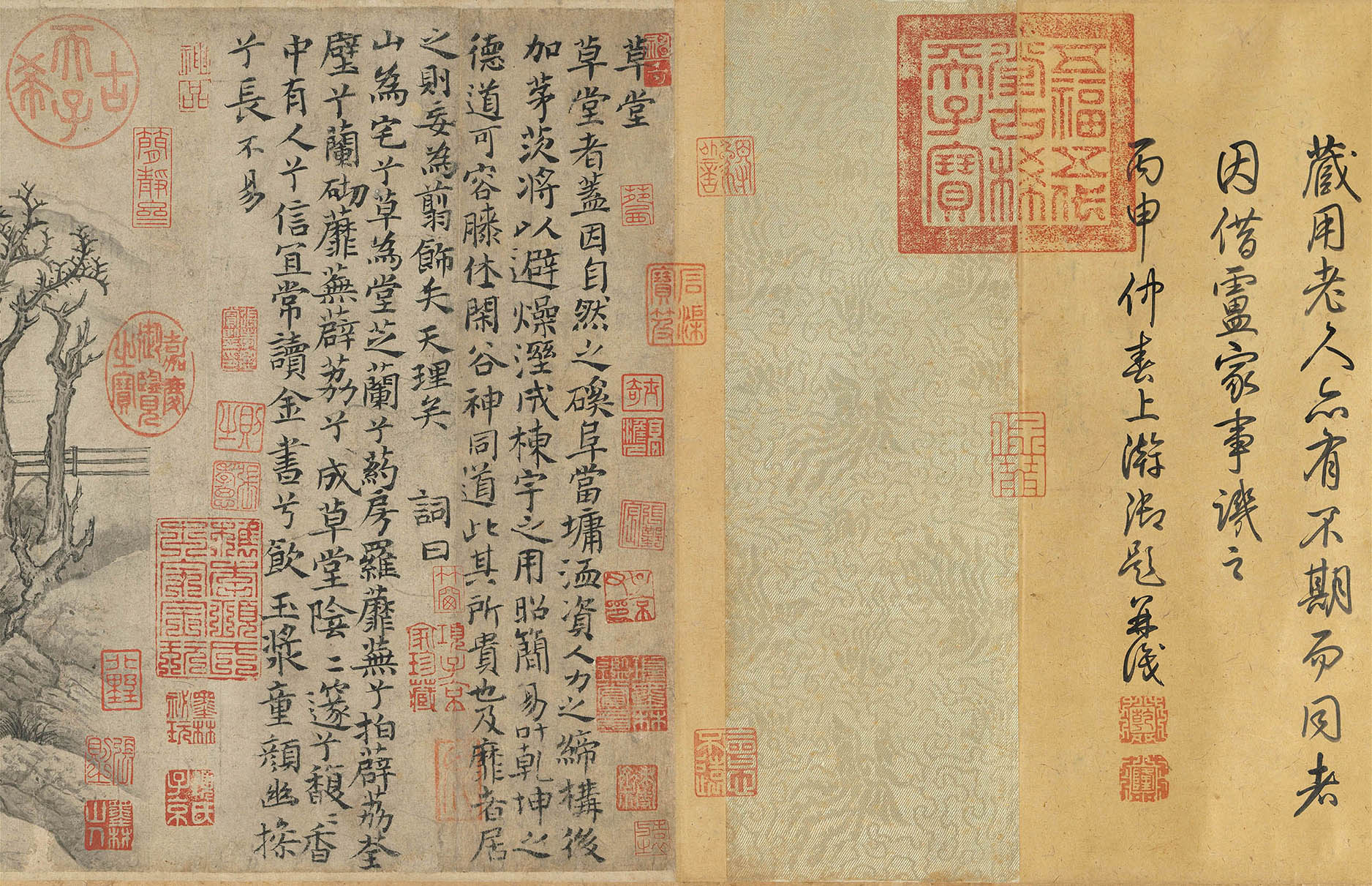

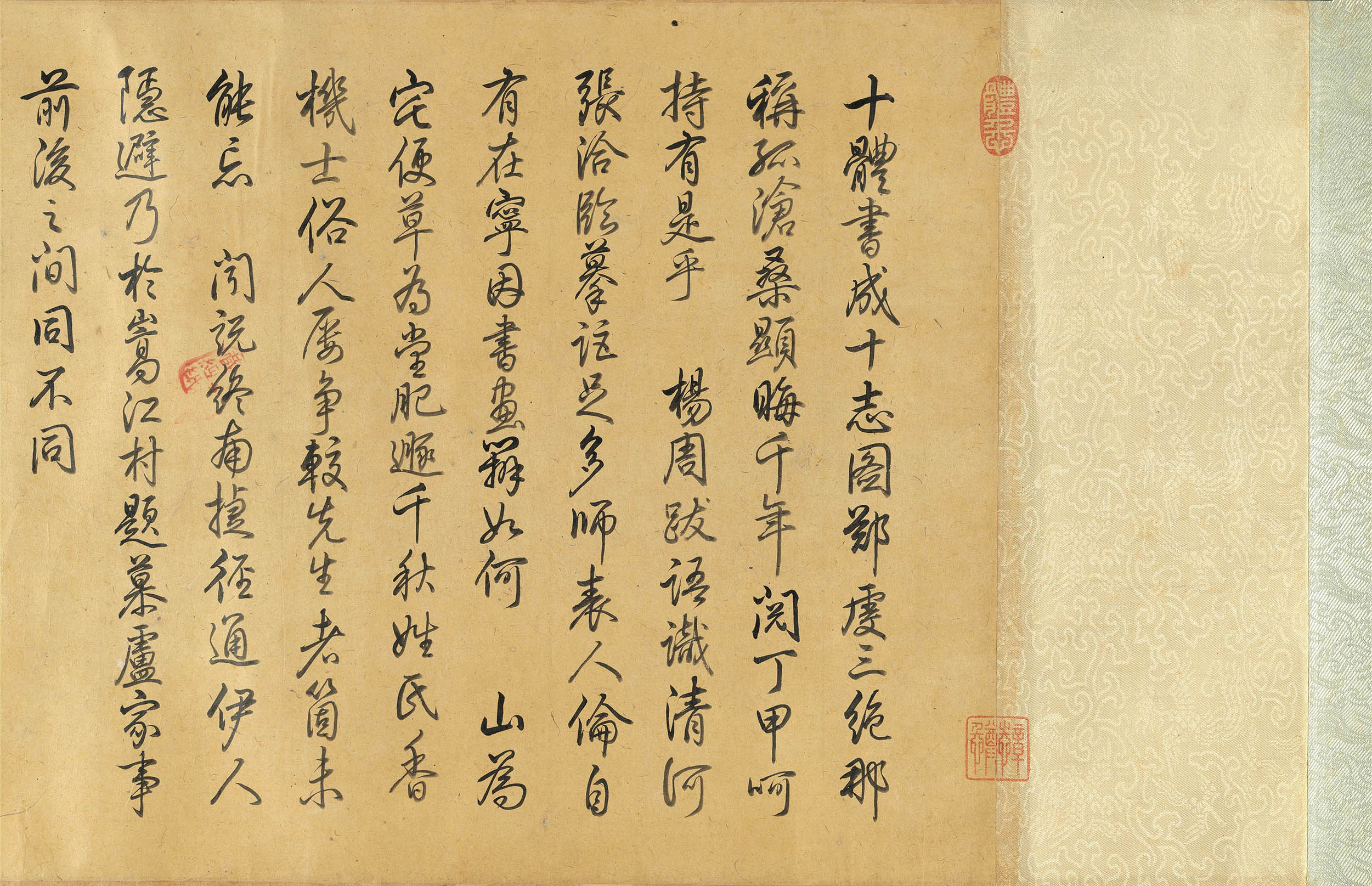

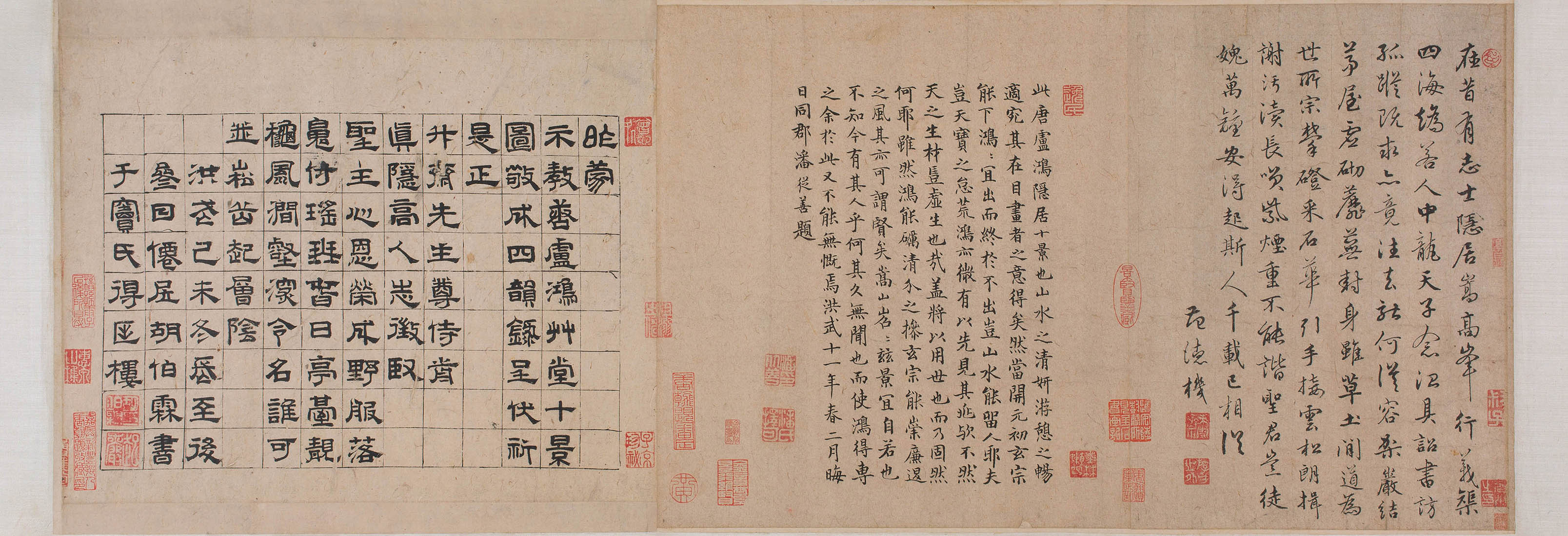

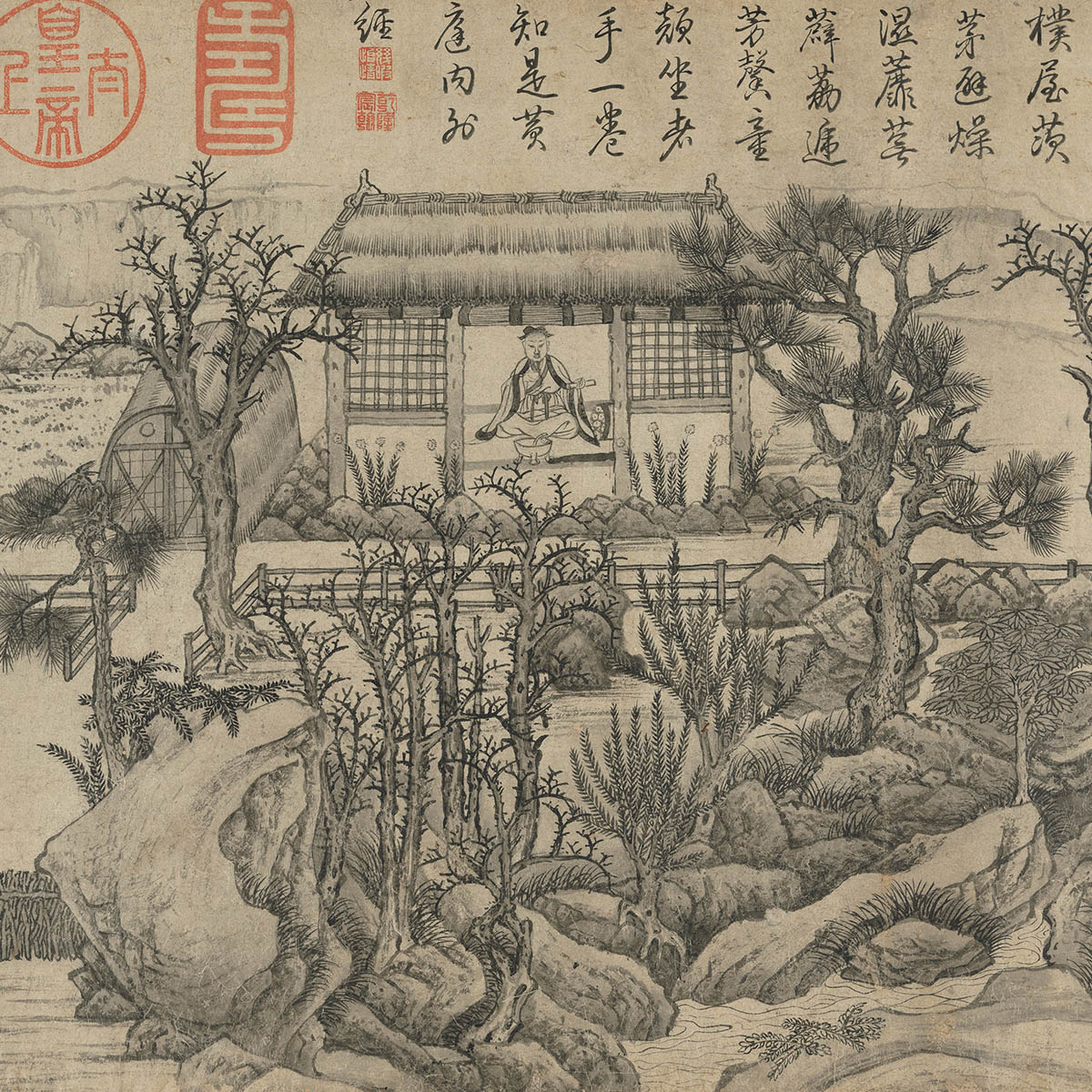

Ten Views from a Thatched Hut

Ten Views from a Thatched Hut

- Lu Hong (7th-8th c.), Tang dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in March 2012 as a Significant Historical Artifact

Lu Hong, an erudite gifted at painting and calligraphy, was summoned by the Tang emperor Xuanzong to serve his court on several occasions but refused. The emperor presented him with a thatched hut as a hermitage to listen to him. It is said that Lu Hong once depicted ten scenic sites around his hermitage, and this handscroll depicts the ten scenes in monochrome ink divided by ten sections of poetry on the views. Although not a painting from the Tang dynasty, scholars have determined it to have been done in the tenth century during the Five Dynasties period, making it possibly the closest copy of the Tang original by Lu Hong. It is an important paradigm for literati landscapes of the recluse and had a major influence on the visual expression of the landscape for living in seclusion throughout Chinese history.

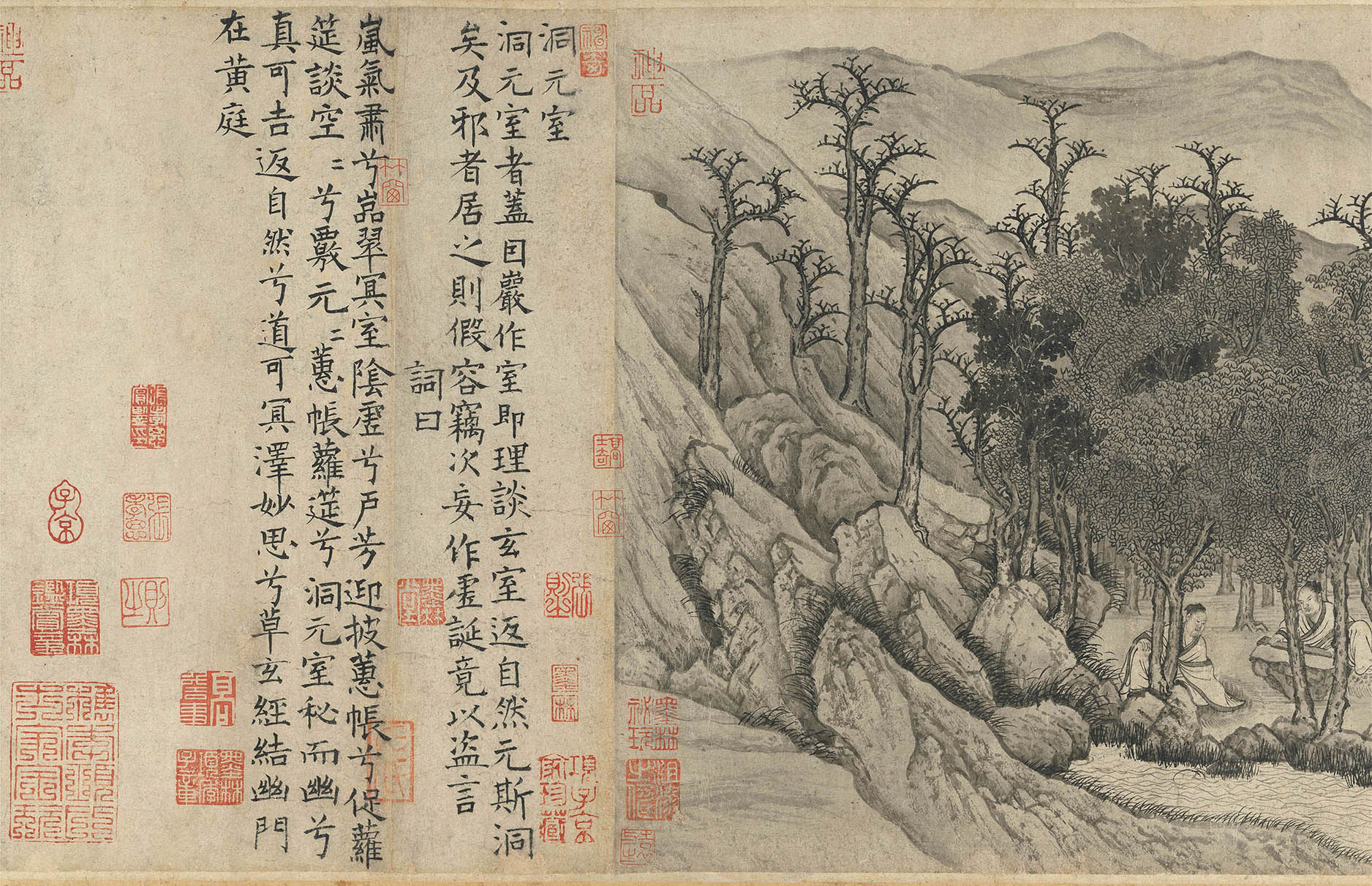

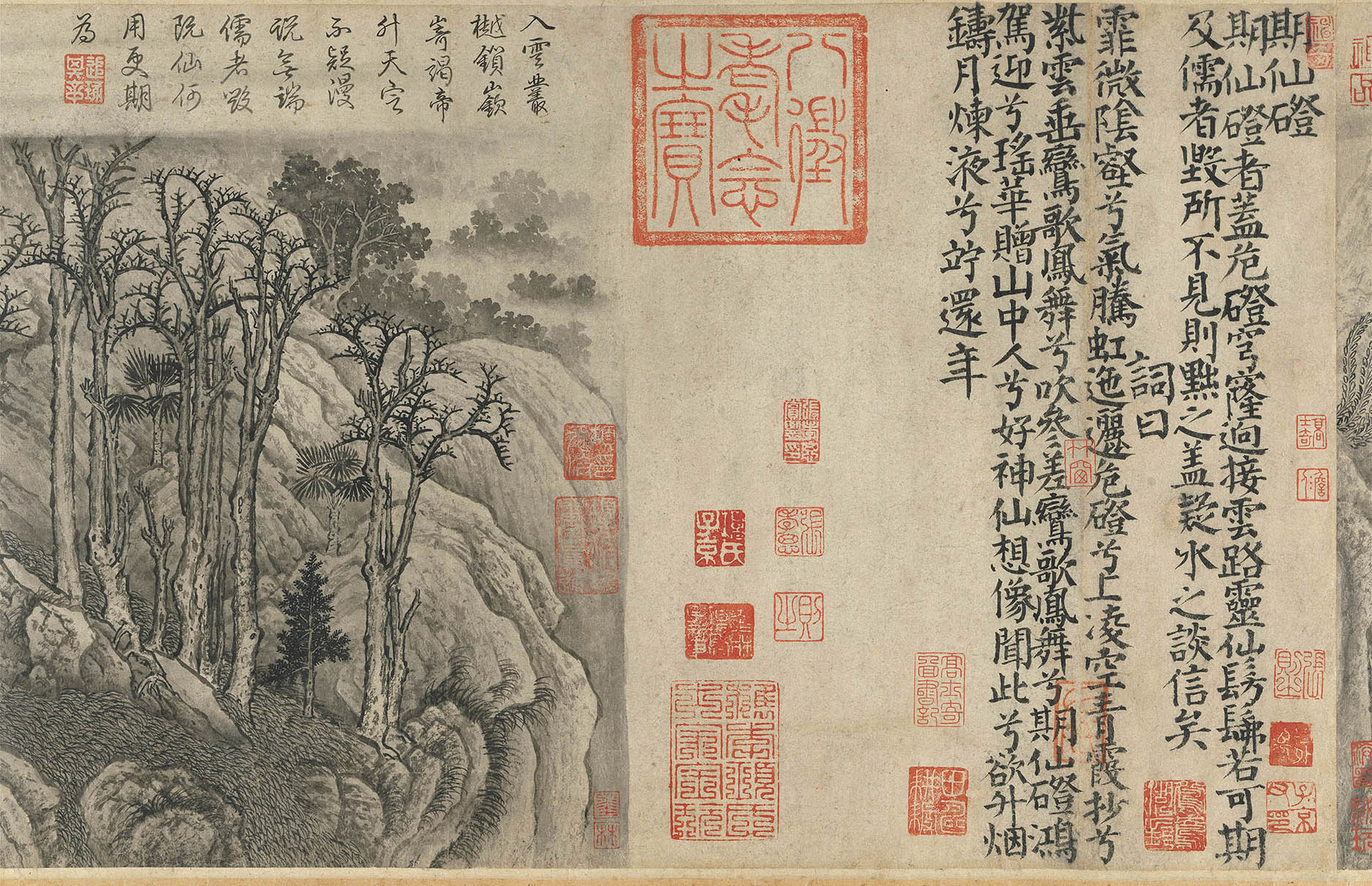

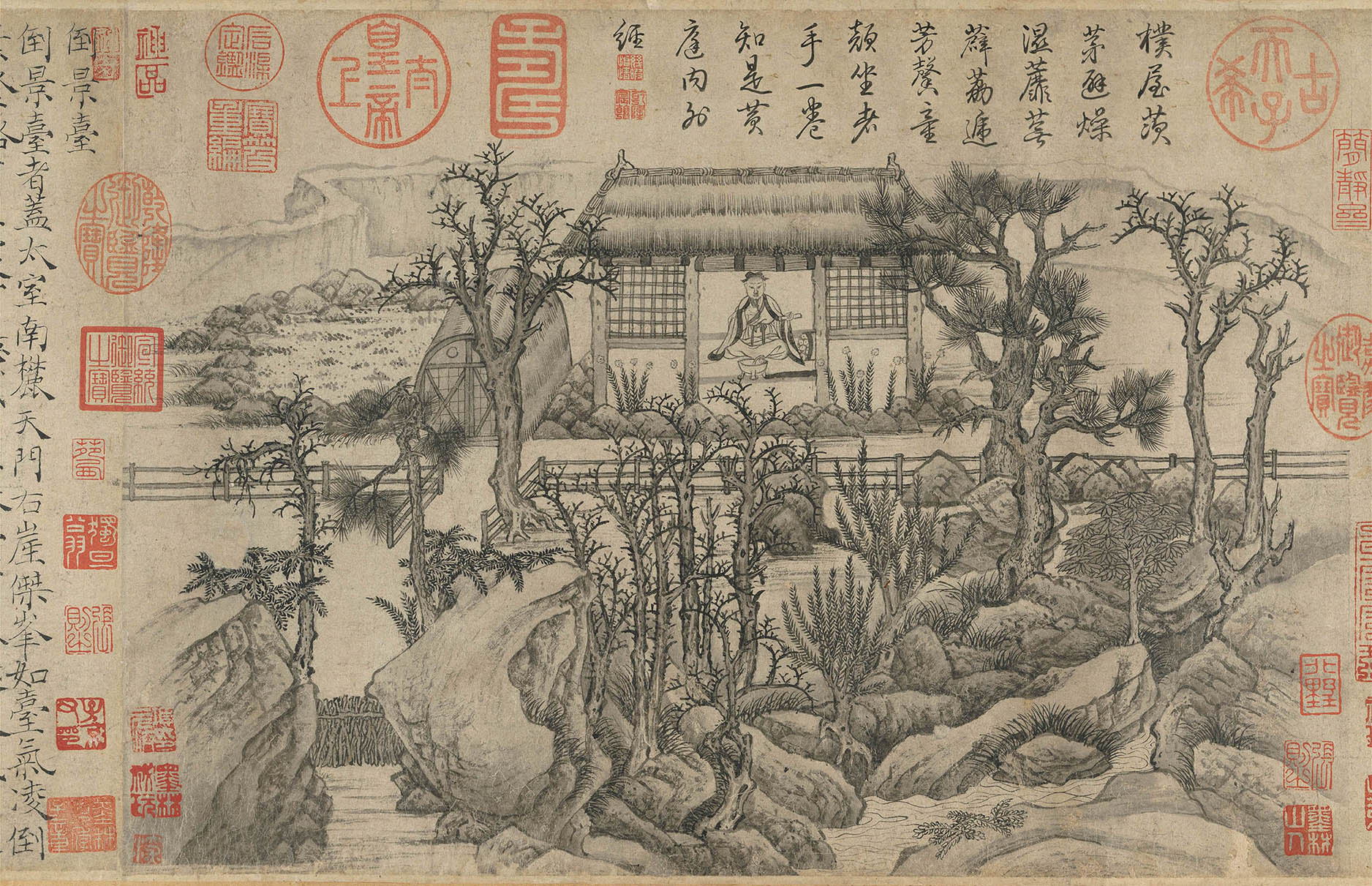

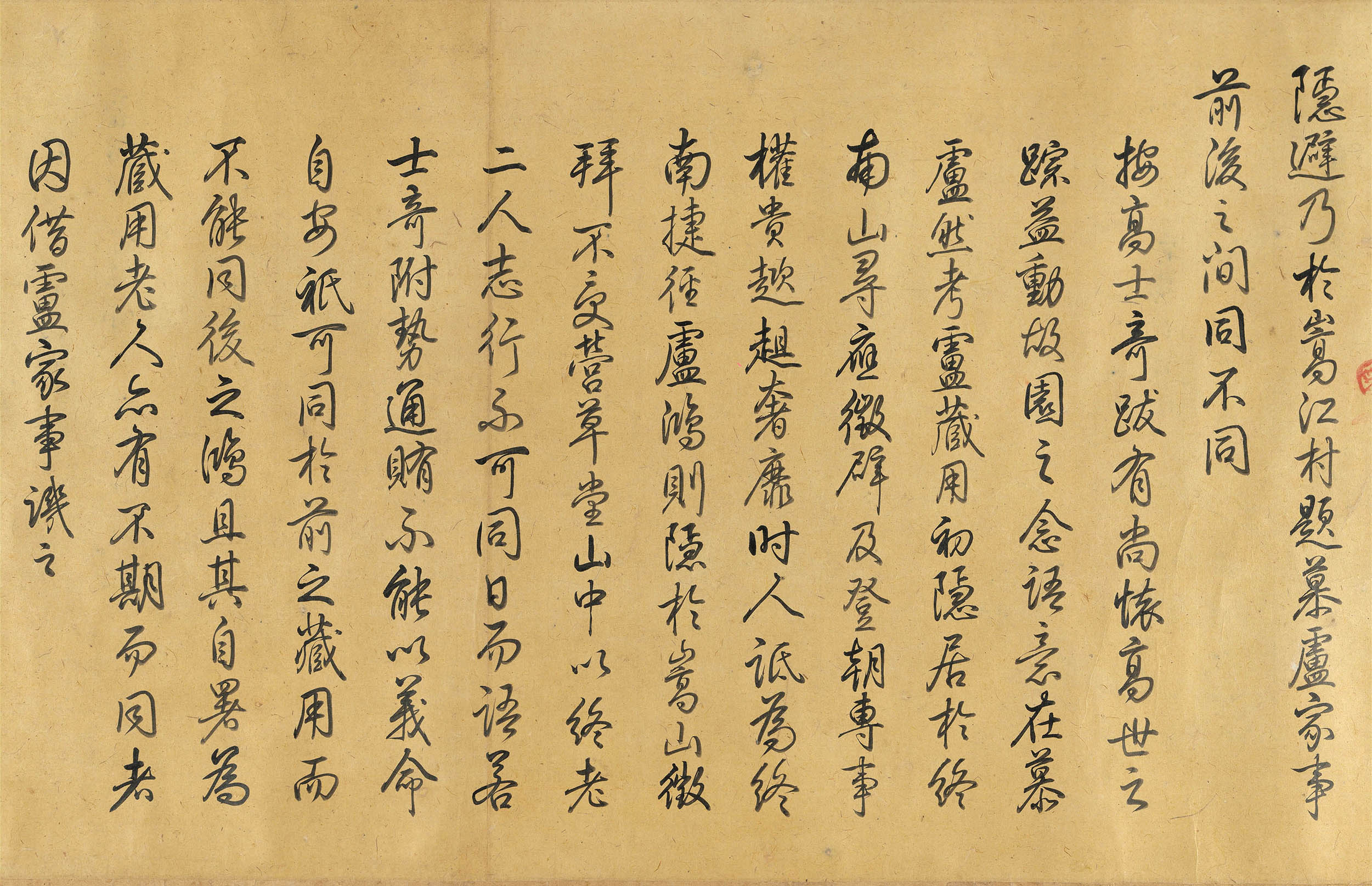

Copy of Lu Hong's "Ten Views from a Thatched Hut"

Copy of Lu Hong's "Ten Views from a Thatched Hut"

- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Researchers consider this handscroll to have been painted in the thirteenth century either during the Southern Song or Jin dynasty. Compared to the dense visuality of "Ten Views from a Thatched Hut" attributed to Lu Hong in the National Palace Museum, this work employs moist dabs of the brush to create an effect of being enveloped in clouds and mists. Making the imagery thus appear more dispersed, the space extends further into the distance. The lifting and application of the brush for the outlines of the rocks create variations in the thickness of the lines. This, combined with the "crab-claw" tree branches, places the work in the Li Cheng and Guo Xi school of painting. Confidently expressing a reinterpretation of the "Ten Views from a Thatched Hut," it represents an extension based on the National Palace Museum version.

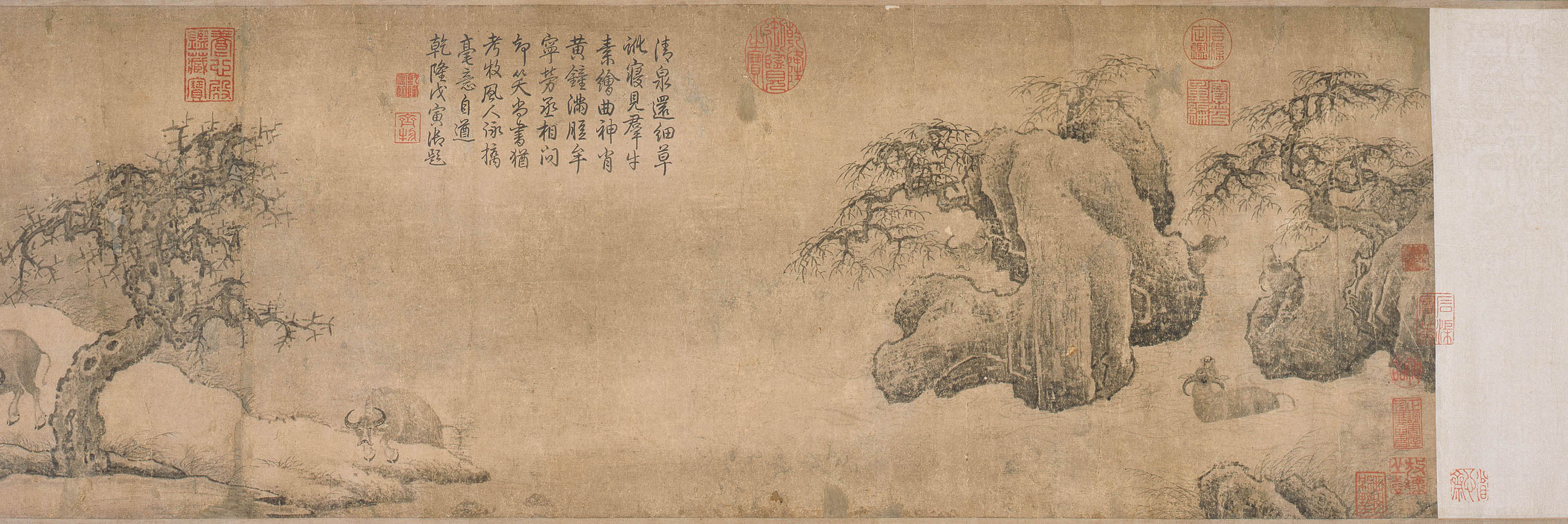

Oxen Grazing

Oxen Grazing

- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

For its background, this handscroll features river scenery that appears to extend without end. In the foreground is a level slope that continues from one end to the other and includes young herders riding on oxen. Some of the oxen, divided into small groups and interspersed in the scroll, go forward with head upraised, pulling in resistance, are locked in battle, or frolic in the water. The various poses and activities are spirited and expressive, the washes and shades of ink for the river highlighted against the shore to appear almost like snow. Combined with the "crab-claw" wintry tree branches and scale-like landscape forms rendered in delicate touches of the brush, a sense of life and vitality permeates the desolate scenery here of herders and oxen unhindered by the cold weather.

Tea Tasting

Tea Tasting

- Qian Xuan (1239-1302), Yuan dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Qian Xuan (style name Shunju) was a native of Wuxing in Zhejiang. Gifted in the literary arts as well as painting and calligraphy, he became known as head of the "Eight Gentleman of Wuxing."

Although this painting is entitled "Tea Tasting," it is actually related to the painting tradition of "tea competitions" popular since the Tang dynasty. This work depicts six men; the ones at the left with a pot, pouring tea, or holding a basket in opposition to the three on the other side holding a cup, drinking, or waiting for tea to appreciate. However, the overall expressions of the figures appear stiff and the coloring slightly monotonous, the painting style unlike the more refined literary elegance of Qian Xuan's manner, suggesting the work of a later hand with Qian's name added to it.

Although this painting is entitled "Tea Tasting," it is actually related to the painting tradition of "tea competitions" popular since the Tang dynasty. This work depicts six men; the ones at the left with a pot, pouring tea, or holding a basket in opposition to the three on the other side holding a cup, drinking, or waiting for tea to appreciate. However, the overall expressions of the figures appear stiff and the coloring slightly monotonous, the painting style unlike the more refined literary elegance of Qian Xuan's manner, suggesting the work of a later hand with Qian's name added to it.

Drink Sellers

Drink Sellers

- Yao Wenhan (fl. 1736-1795), Qing dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

- Provisionally classified by the National Palace Museum as a Significant Historical Artifact

Yao Wenhan (style name Zhuoting) served as a painter at the court of the Qianlong emperor and specialized in religious subjects and figures. The Qing imperial catalogue Forest of Pearls in the Secret Hall ranks his religious works as exceptionally grand and refined, comparable to those Ding Guanpeng, another eighteenth-century artist famous for such subject matter.

This painting depicts a scene of selling tea at a market. Ten figures, including male and female as well as young and old, are shown in a variety of activities, such as fanning a stove to brew tea, holding a pot selling tea, or enjoying tea in an interesting and lively scene. The tea poles and utensils are all rendered in great detail with nothing missing. The coloring throughout is pure and beautiful, the brushwork precise and strong. The faces of the figures are also rendered with slight shading to suggest shadows that give them a sense of volume.

This painting depicts a scene of selling tea at a market. Ten figures, including male and female as well as young and old, are shown in a variety of activities, such as fanning a stove to brew tea, holding a pot selling tea, or enjoying tea in an interesting and lively scene. The tea poles and utensils are all rendered in great detail with nothing missing. The coloring throughout is pure and beautiful, the brushwork precise and strong. The faces of the figures are also rendered with slight shading to suggest shadows that give them a sense of volume.

Bamboo and Sparrows

Bamboo and Sparrows

- Wang Yuan (fl. 14th c.), Yuan dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Wang Yuan in his earlier years received instruction from the famous artist Zhao Mengfu and was particularly skilled at bird-and-flower painting.

This work features a pair of partridges in the foreground by some rocks with bamboo and tall plants accompanied by such wildflowers as dianthus and dandelions scattered about the scene. Sparrows are seen perched, flying, and pecking for food, the rock face at the left inscribed as follows: "Copy of Huang Quan's ‘Bamboo and Sparrows' by Ruoshui, Wang Yuan." The composition of this work is similar to "Blue Magpie and Thorny Shrubs" by Huang Jucai in the National Palace Museum and follows the tradition of birds and flowers by a tree that goes back to at least the Tang dynasty (618-907). The contrast between light and dark ink throughout this work is exceptionally fine, the forms rendered simply with a high degree of antiquarianism.

This work features a pair of partridges in the foreground by some rocks with bamboo and tall plants accompanied by such wildflowers as dianthus and dandelions scattered about the scene. Sparrows are seen perched, flying, and pecking for food, the rock face at the left inscribed as follows: "Copy of Huang Quan's ‘Bamboo and Sparrows' by Ruoshui, Wang Yuan." The composition of this work is similar to "Blue Magpie and Thorny Shrubs" by Huang Jucai in the National Palace Museum and follows the tradition of birds and flowers by a tree that goes back to at least the Tang dynasty (618-907). The contrast between light and dark ink throughout this work is exceptionally fine, the forms rendered simply with a high degree of antiquarianism.

Hawk Pursuing a Thrush

Hawk Pursuing a Thrush

- Wang Yuan (fl. 14th c.), Yuan dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

- Provisionally classified by the National Palace Museum as a Significant Historical Artifact

Wang Yuan earlier learned painting from the famous artist Zhao Mengfu and excelled at the traditional subject of "birds and flowers."

A hawk is shown in this painting quickly diving from the sky at an angle as it prepares to attack a thrush taking cover below. The hawk's beak curves to a sharp point, and its eyes are fierce and beaming. Its strong and powerful claws are retracted as it dives. The thrush, on the other hand, opens its beak and shrieks in terror at the impending attack. The brushwork is exceptionally precise, the depiction of the hawk and thrush also quite realistic. The bamboo and tree with withered reeds gently sway, as if moving in response to the momentum of the action taking place. The scenery is rich and dynamic, the coloring warm and elegant, much in the old style of Song dynasty painting.

A hawk is shown in this painting quickly diving from the sky at an angle as it prepares to attack a thrush taking cover below. The hawk's beak curves to a sharp point, and its eyes are fierce and beaming. Its strong and powerful claws are retracted as it dives. The thrush, on the other hand, opens its beak and shrieks in terror at the impending attack. The brushwork is exceptionally precise, the depiction of the hawk and thrush also quite realistic. The bamboo and tree with withered reeds gently sway, as if moving in response to the momentum of the action taking place. The scenery is rich and dynamic, the coloring warm and elegant, much in the old style of Song dynasty painting.

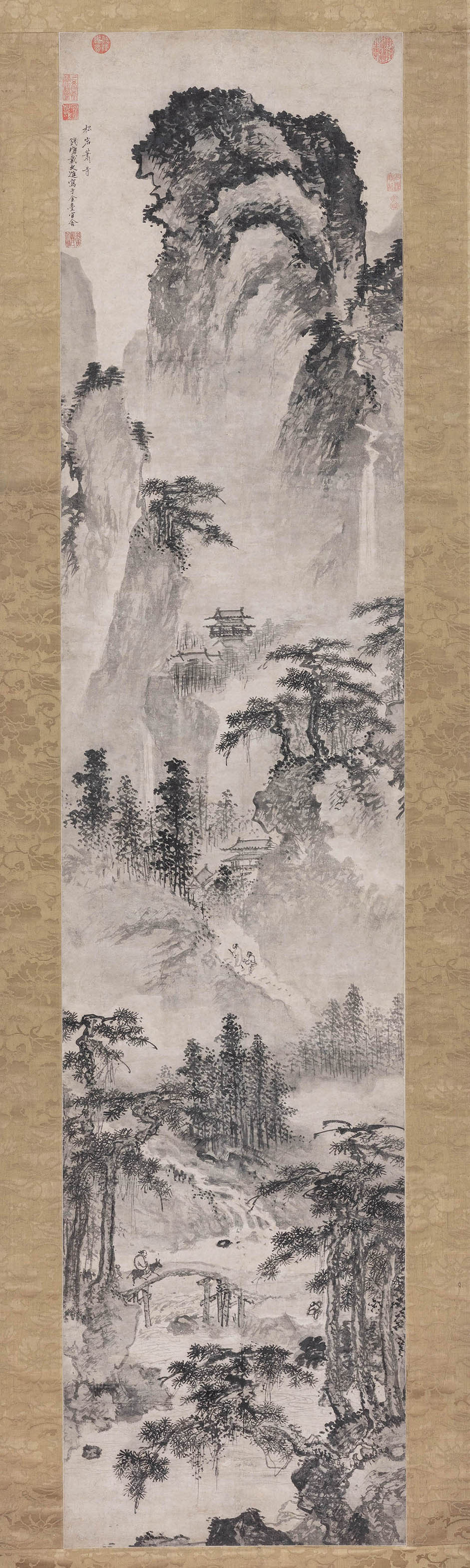

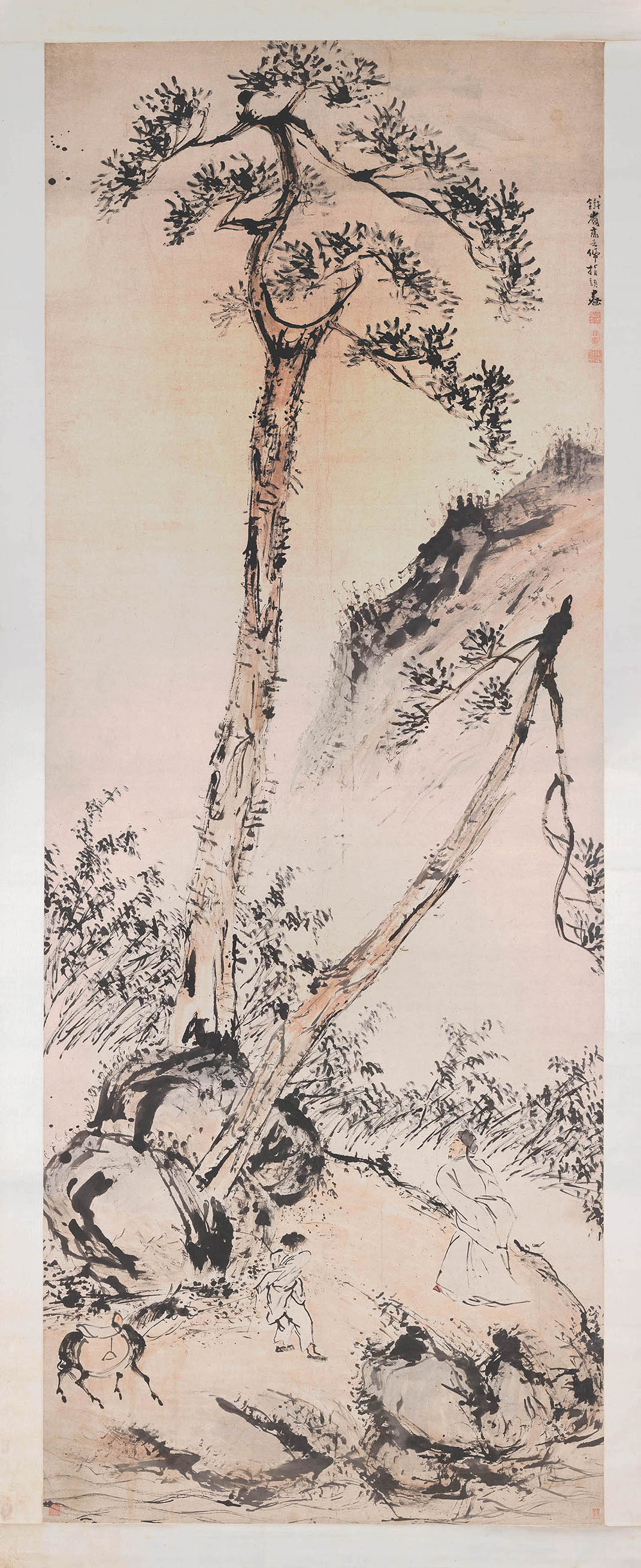

Torrent at Mount Taibai

Torrent at Mount Taibai

- Fang Congyi (fl. 1302-1393), Yuan dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Fang Congyi (style name Wuyu, sobriquet Fanghu) was a Daoist at the Shangqing Temple on Mount Longhu (Dragon Tiger) in Jiangxi. When younger, he studied Daoism under Jinliantou and later traveled to the capital of Dadu and visited the famous mountains associated with Daoism.

This painting adopts a compositional formula dividing into a foreground with a middle ground, distant view, and far distance. The foreground scenery depicts a lofty recluse-scholar among the mountain forms and trees, while the middle features mountains delicately outlined in fine brushwork. This is followed by a precipitous cliff rising upwards that lead to a distant landscape rendered in wet ink to create the effect of deep and secluded distance. To the right is a waterfall cascading in segments over the cliff, thus highlighting the majestic appearance of Mount Taibai reaching into the clouds.

This painting adopts a compositional formula dividing into a foreground with a middle ground, distant view, and far distance. The foreground scenery depicts a lofty recluse-scholar among the mountain forms and trees, while the middle features mountains delicately outlined in fine brushwork. This is followed by a precipitous cliff rising upwards that lead to a distant landscape rendered in wet ink to create the effect of deep and secluded distance. To the right is a waterfall cascading in segments over the cliff, thus highlighting the majestic appearance of Mount Taibai reaching into the clouds.

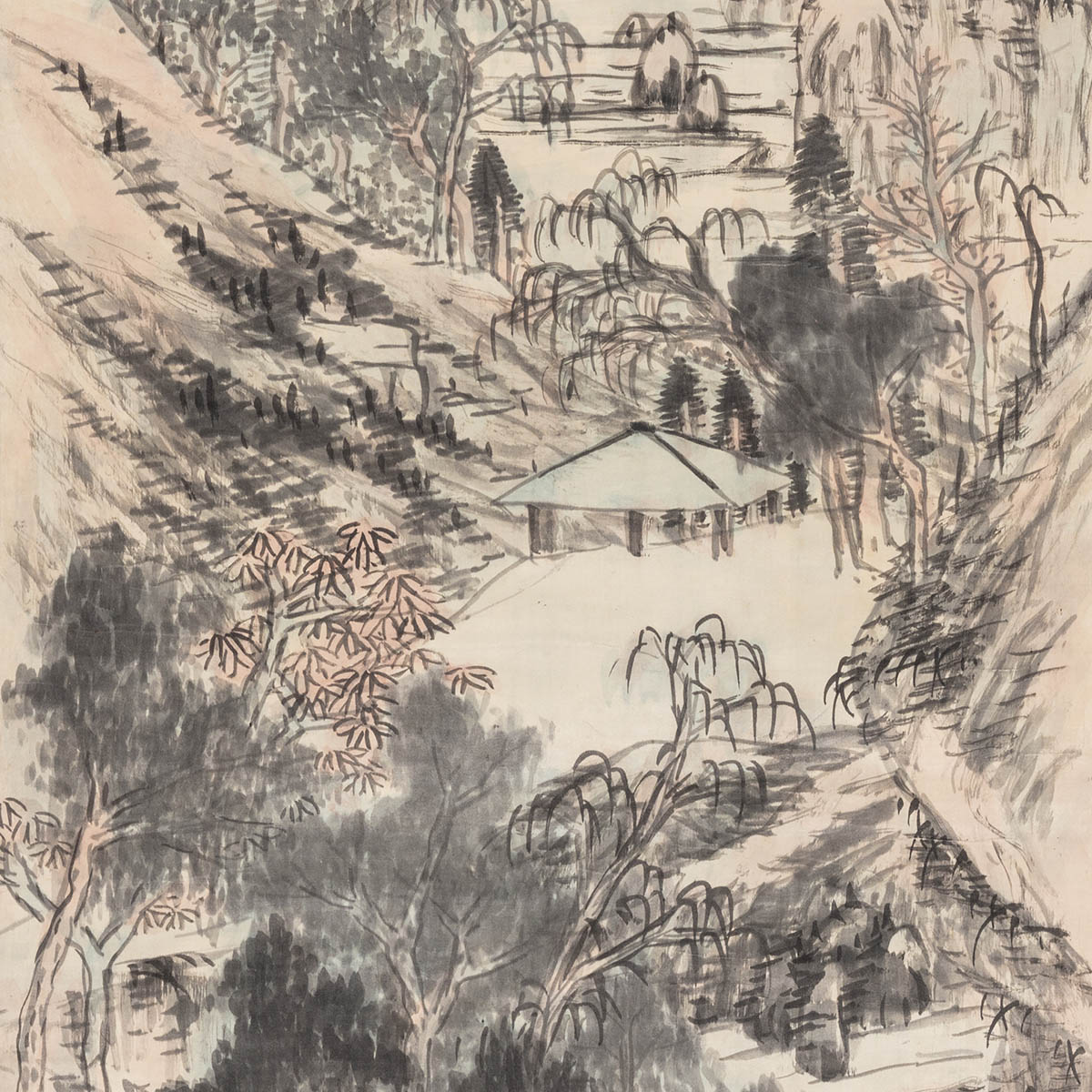

Literary Gathering at a Mountain Pavilion

Literary Gathering at a Mountain Pavilion

- Wang Fu (1362-1416), Ming dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in December 2008 as a Significant Historical Artifact

Wang Fu (style name Mengduan; sobriquets Youshisheng, Jiulong shanren) excelled at painting ink bamboo and landscapes. He was a major artist of the late Yuan and early Ming period.

This painting done in 1404 depicts such motifs as a secluded residence in a mountain forest with an elegant gathering taking place in a kiosk and boating, exhibiting a yearning for a "Peach Blossom" utopian world. The composition is complex but clearly distinguished between main and subsidiary motifs without a sense of overbearing. Everything is rendered in layers of strokes and washes, starting with dry brushwork and leading to darker ink that is complicated but not chaotic. The work incorporates the manners of such Yuan literati artists as Wang Meng (1308-1385) and Wu Zhen (1280-1354), combining a pure and spirited freshness with an atmosphere of solid weightiness to make it a masterpiece from Wang Fu's hand.

This painting done in 1404 depicts such motifs as a secluded residence in a mountain forest with an elegant gathering taking place in a kiosk and boating, exhibiting a yearning for a "Peach Blossom" utopian world. The composition is complex but clearly distinguished between main and subsidiary motifs without a sense of overbearing. Everything is rendered in layers of strokes and washes, starting with dry brushwork and leading to darker ink that is complicated but not chaotic. The work incorporates the manners of such Yuan literati artists as Wang Meng (1308-1385) and Wu Zhen (1280-1354), combining a pure and spirited freshness with an atmosphere of solid weightiness to make it a masterpiece from Wang Fu's hand.

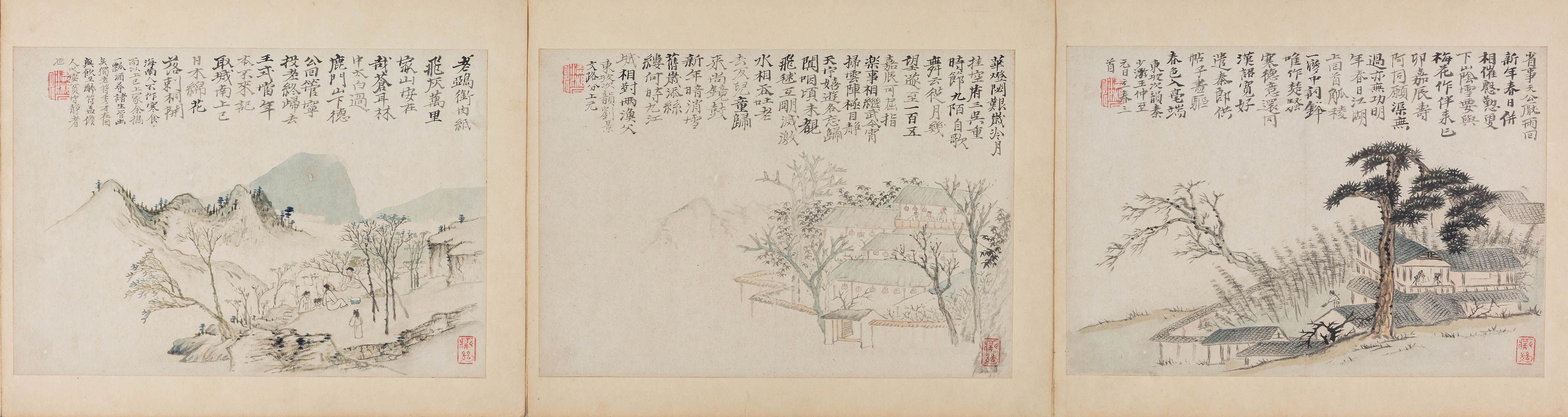

Collective Mounting

Collective Mounting

- Various painters, Ming dynasty (1368-1644)

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

This handscroll features three works mounted together done mostly in dabs and washes of the brush by three renowned literati painters of the Ming dynasty. The first on the right is entitled "Landscape Painted for Mizhai" by Wang Fu (1362-1416) and dates from the Yongle reign (1402-1424). Judging from the inscription, this scene of a riverbank painted by Wang Fu (style name Mengduan) on the ninth day of the fifth lunar month in the Yongle "jiashen" year (1404) was a farewell gift for a friend named Mizhai. Gu Yin also wrote a poetic ode on the painting.

The second painting in the middle is by Shen Zhou (1427-1509, style name Qi'nan) and titled "Sparse Trees and Leisurely Abode." On the right, the third one is "Former Ode on the Red Cliff" by Chen Chun (1483-1544, style name Daofu). According to Chen's inscription, he did the painting in response to someone who had brought him a work of calligraphy on "Former Ode on the Red Cliff" that he had done in the past, and so he added the painting.

The second painting in the middle is by Shen Zhou (1427-1509, style name Qi'nan) and titled "Sparse Trees and Leisurely Abode." On the right, the third one is "Former Ode on the Red Cliff" by Chen Chun (1483-1544, style name Daofu). According to Chen's inscription, he did the painting in response to someone who had brought him a work of calligraphy on "Former Ode on the Red Cliff" that he had done in the past, and so he added the painting.

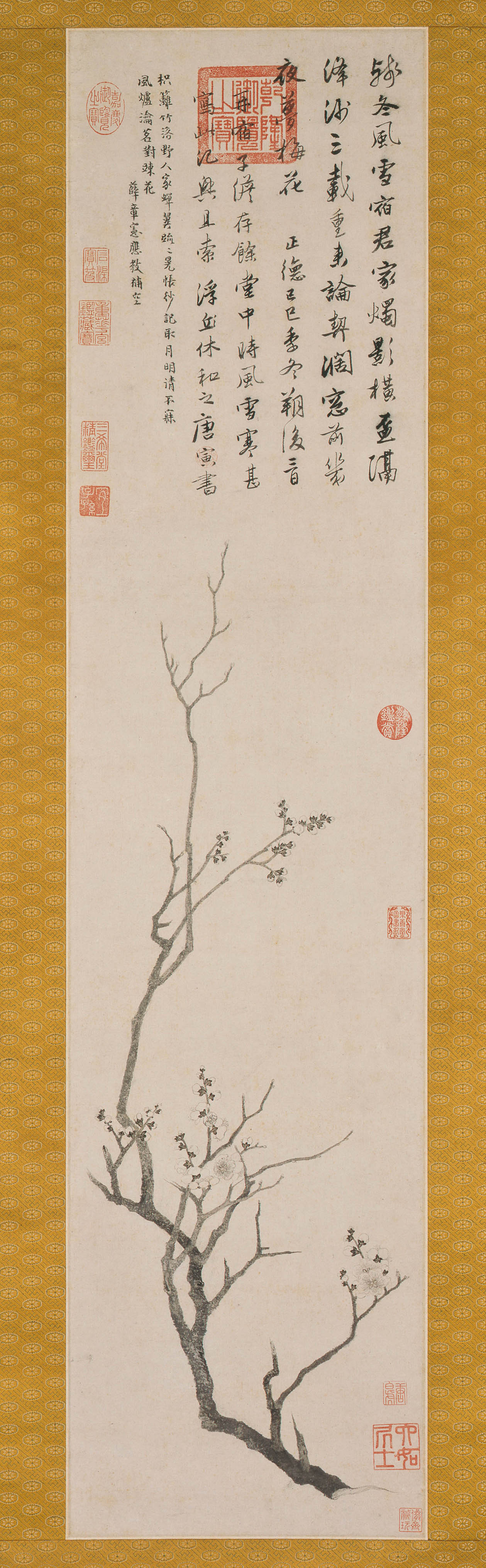

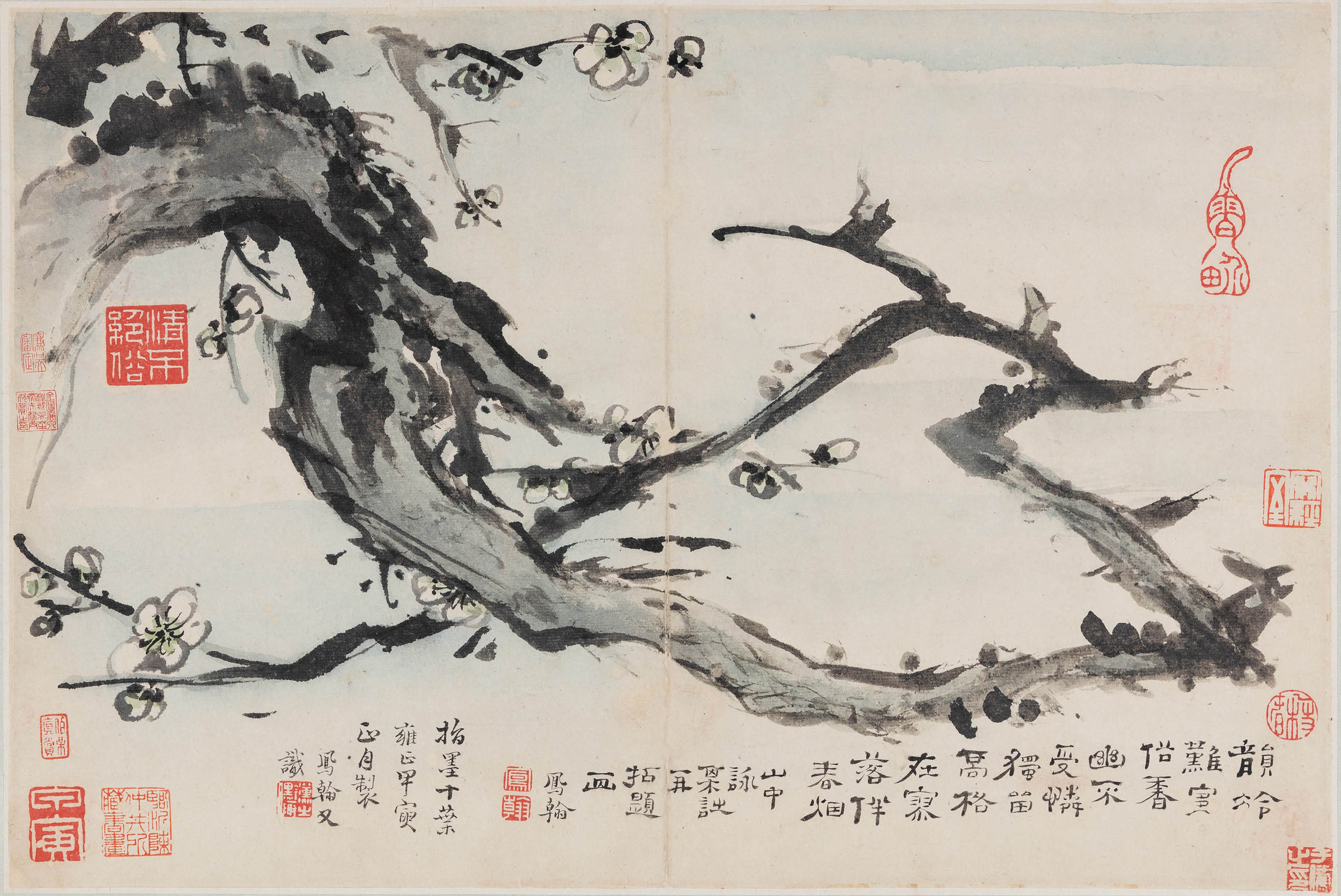

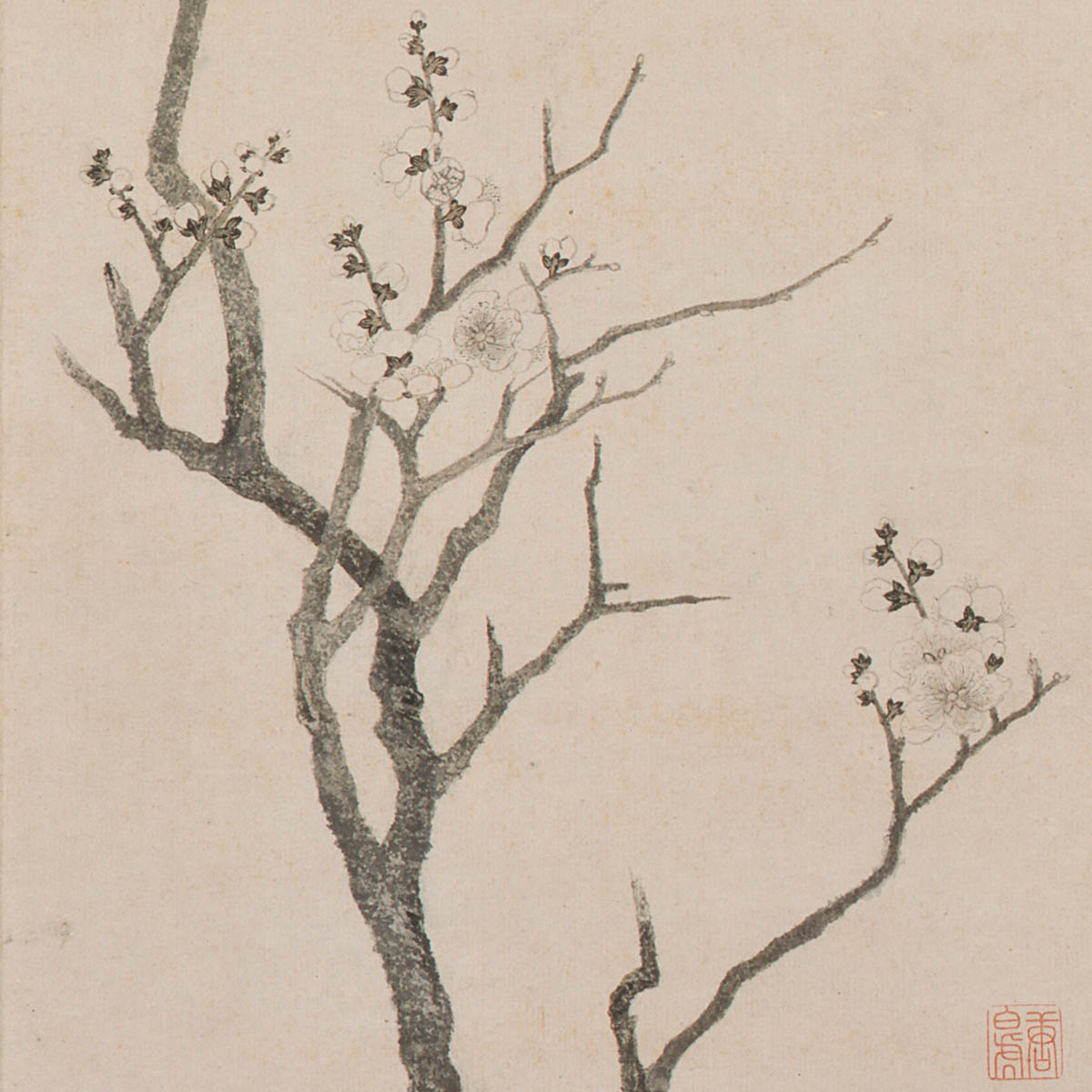

Plum Blossoms

Plum Blossoms

- Tang Yin (1470-1524), Ming dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Tang Yin (style name Bohu, sobriquet Liuru jushi) was friends with such figures as Wen Zhengming, Zhu Yunming, and Xu Zhenqing, and people called them the "Four Talents of Wu."

This painting depicts the branch of a blossoming plum tree rising from the lower part of the composition, the concept of which differs somewhat from other depictions of plum blossoms. The brushwork is strong and powerful, the ink tones rich and varied. The new twigs on the old branch overlap with clearly distinguished spacing, the blossom petals done in "baimiao" outlines that appear both dynamic and lifelike. The large area of blank paper makes the blossoms stand out against the vast pristine background, allowing them to echo the inscription of poetry in the upper part of the composition.

This painting depicts the branch of a blossoming plum tree rising from the lower part of the composition, the concept of which differs somewhat from other depictions of plum blossoms. The brushwork is strong and powerful, the ink tones rich and varied. The new twigs on the old branch overlap with clearly distinguished spacing, the blossom petals done in "baimiao" outlines that appear both dynamic and lifelike. The large area of blank paper makes the blossoms stand out against the vast pristine background, allowing them to echo the inscription of poetry in the upper part of the composition.

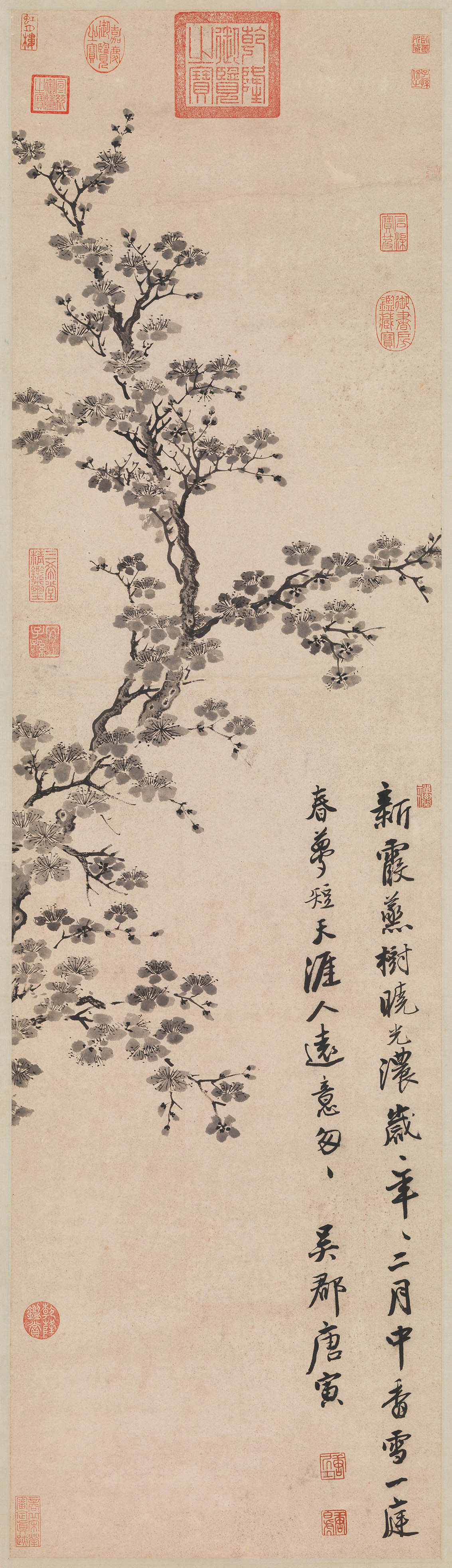

Apricot Blossoms

Apricot Blossoms

- Tang Yin (1470-1524), Ming dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

Tang Yin (style name Bohu, sobriquet Liuru jushi) was a native of Wuxian in Jiangsu.

This painting depicts the branch of an apricot tree extending from the left up to the top and also to the right using dark ink and texturing brush strokes. The dense blossoms composed of dots and washes in light and dark ink feature complex petals with pistils and stamens combining both precise and free-hand techniques of brushwork to give them a clear and vivid appearance. The composition features a strong sense of space, and the balance between dense forms and open space, along with the succinct use of brush and ink, make the blank paper seem to come alive. The inscribed poetry takes the object of expression to convey emotions, the calligraphy likewise flowing and agreeable, allowing these three art forms to echo each other well. This is one of the characteristics of literati painting in the Ming dynasty.

This painting depicts the branch of an apricot tree extending from the left up to the top and also to the right using dark ink and texturing brush strokes. The dense blossoms composed of dots and washes in light and dark ink feature complex petals with pistils and stamens combining both precise and free-hand techniques of brushwork to give them a clear and vivid appearance. The composition features a strong sense of space, and the balance between dense forms and open space, along with the succinct use of brush and ink, make the blank paper seem to come alive. The inscribed poetry takes the object of expression to convey emotions, the calligraphy likewise flowing and agreeable, allowing these three art forms to echo each other well. This is one of the characteristics of literati painting in the Ming dynasty.

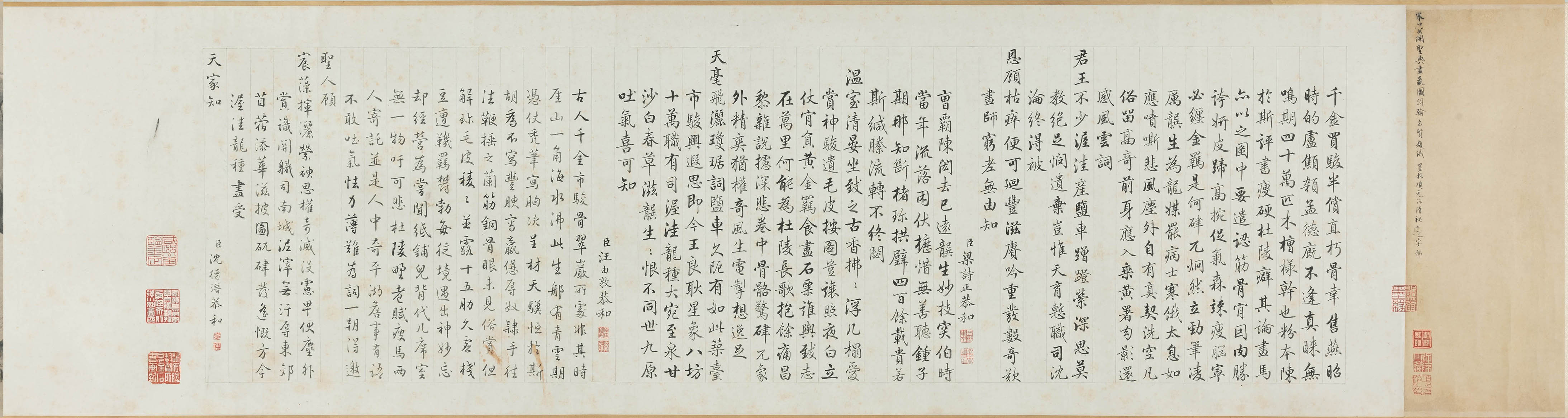

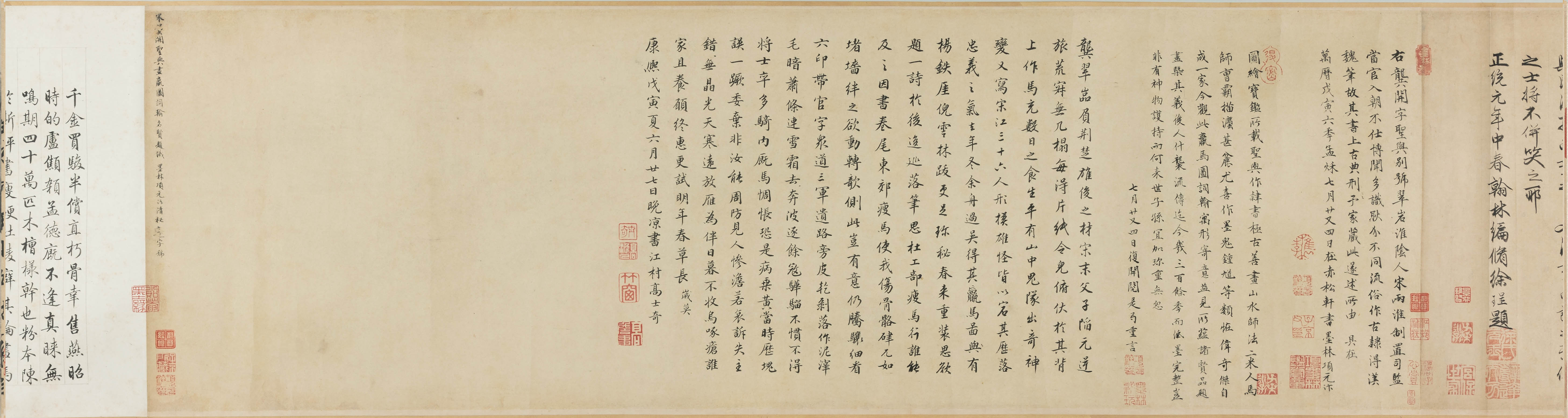

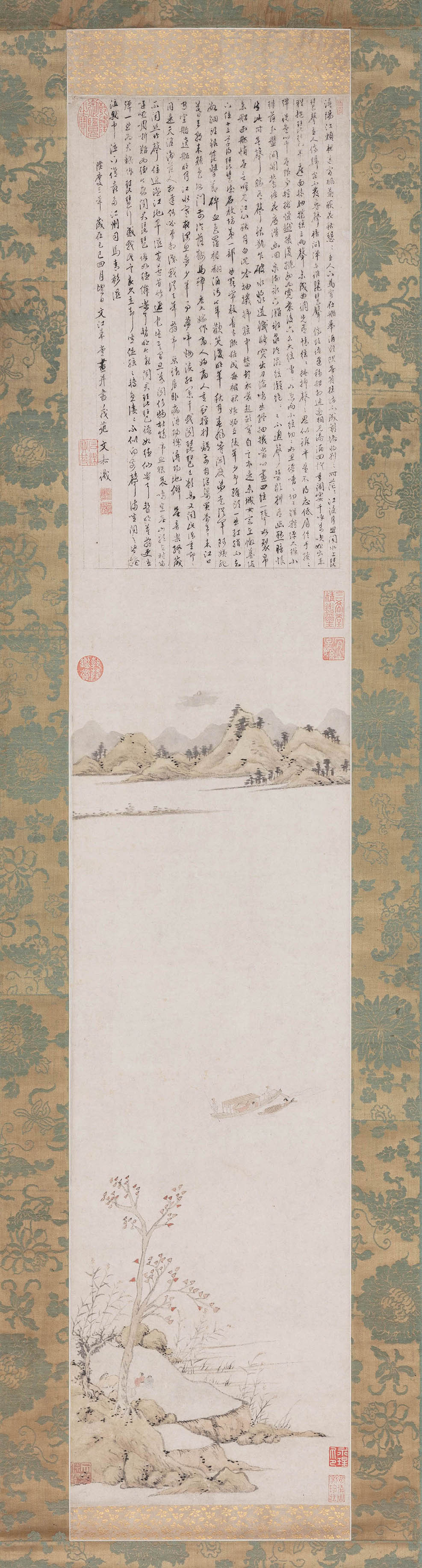

Song of the Pipa

Song of the Pipa

- Wen Jia (1501-1583), Ming dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Wen Jia, a native of Suzhou in Jiangsu, was the second son of the famous artist Wen Zhengming and skilled at poetry as well as calligraphy and painting, following closely in the tradition of his father.

This painting dated to 1569 is based on the famous poem "Song of the Pipa" by Bai Juyi (772-846) of the Tang dynasty. It depicts the poet banished to Jiujiang, spending a night on a boat by the riverbank, listening to a courtesan from Chang'an play a song on a pipa, and recounting the sad state into which he had befallen. At the top of the painting is a transcription in semi-cursive script for "Song of the Pipa," the brushwork quick and fluid with much diagonal force. The brushwork in the landscape, on the other hand, is beautiful and refined. The effect of expansiveness and distance serves as an ultimate expression of the refined elegance conveyed in the Wu School of Ming dynasty literati painting.

This painting dated to 1569 is based on the famous poem "Song of the Pipa" by Bai Juyi (772-846) of the Tang dynasty. It depicts the poet banished to Jiujiang, spending a night on a boat by the riverbank, listening to a courtesan from Chang'an play a song on a pipa, and recounting the sad state into which he had befallen. At the top of the painting is a transcription in semi-cursive script for "Song of the Pipa," the brushwork quick and fluid with much diagonal force. The brushwork in the landscape, on the other hand, is beautiful and refined. The effect of expansiveness and distance serves as an ultimate expression of the refined elegance conveyed in the Wu School of Ming dynasty literati painting.

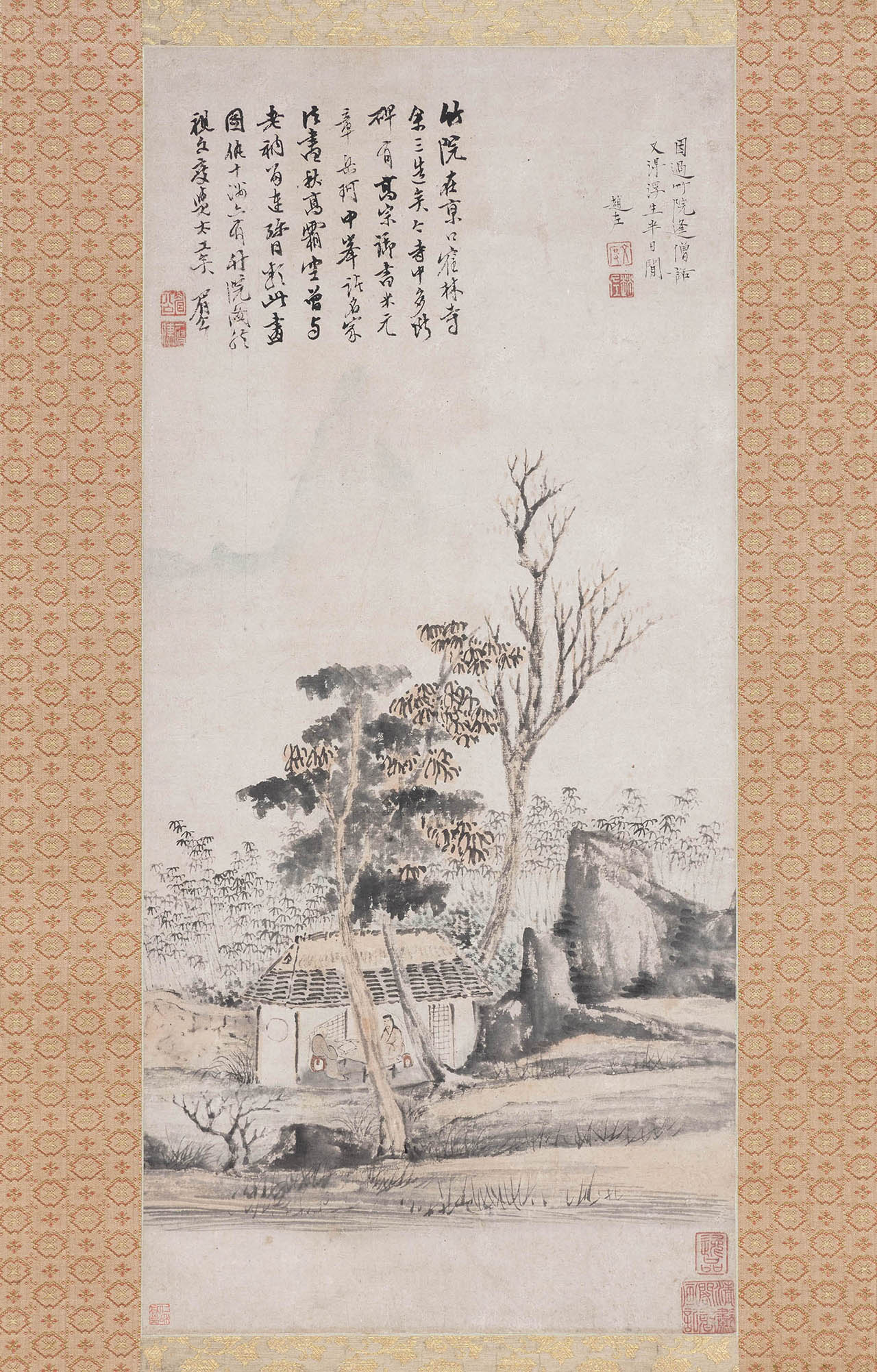

Encountering a Monk in a Bamboo Courtyard

Encountering a Monk in a Bamboo Courtyard

- Zhao Zuo (1573-1644), Ming dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Zhao Zuo's style combined the painting traditions of both the Suzhou and Songjiang regions. In this painting appears a literatus seated facing a Buddhist monk in a thatched hut, the scene corresponding to two lines originally by a Tang poet written in the upper part: "Passing by a bamboo courtyard and meeting with a monk, I once again gain a half-day's leisure in this fleeting life of mine." This was a popular subject at the time, and Zhao Zuo's means of interpretation included not only the bamboo and trees but also large rocks and water as well as an expansive area of mists to make the bamboo courtyard stand out further. Even more interesting is how he utilized the tree trunks and enclosure to create a space cell to frame the scholar and emphasize the limited leisure of appreciation.

Autumn Trees and Distant Peaks

Autumn Trees and Distant Peaks

- Yang Wencong (1597-1646), Ming dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Yang Wencong (style name Longyou) was a native of Guiyang in Guizhou and a member of literati circles in the Jiangnan region. He was also an early member of the "Revival Society" and entered officialdom in 1634, serving as the Vice Commissioner of Defense in the Southern Ming exile government of the Prince of Fu.

This painting from 1631 features a "one-river, two banks" compositional formula. In the foreground are trees painted in different manners of brushwork, the ink tones richly varied and translucent. The rounded rocks are full of twisting energy, to which "hemp-fiber" texture strokes have been combined with coarse curving lines similar to seaweed. The "moss dots" of varying lengths also add considerable energy. The ink tones on the damask silk here further highlights the atmosphere of a bright and refreshing day in autumn.

This painting from 1631 features a "one-river, two banks" compositional formula. In the foreground are trees painted in different manners of brushwork, the ink tones richly varied and translucent. The rounded rocks are full of twisting energy, to which "hemp-fiber" texture strokes have been combined with coarse curving lines similar to seaweed. The "moss dots" of varying lengths also add considerable energy. The ink tones on the damask silk here further highlights the atmosphere of a bright and refreshing day in autumn.

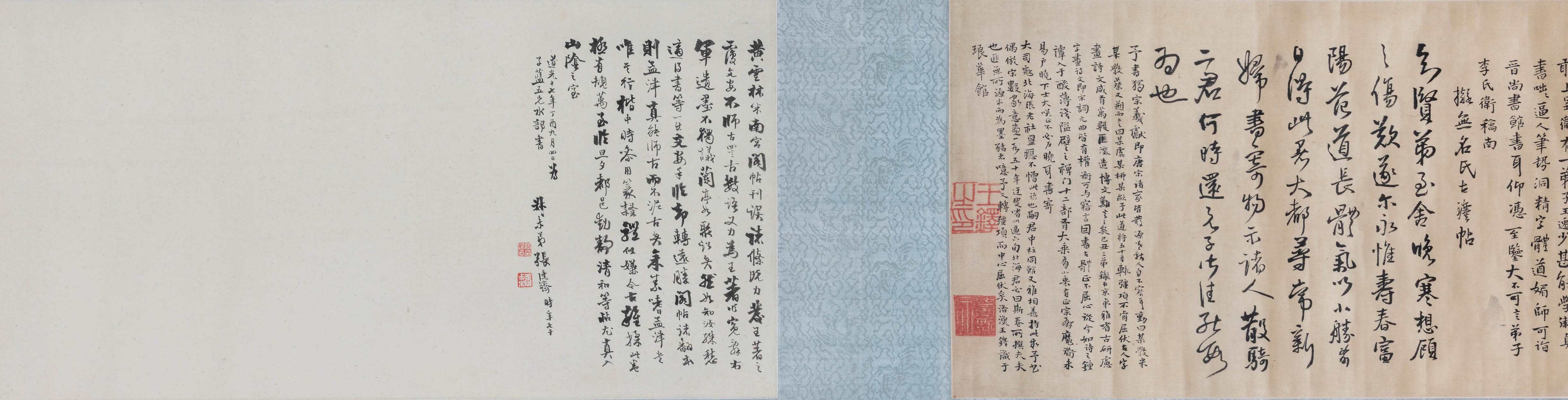

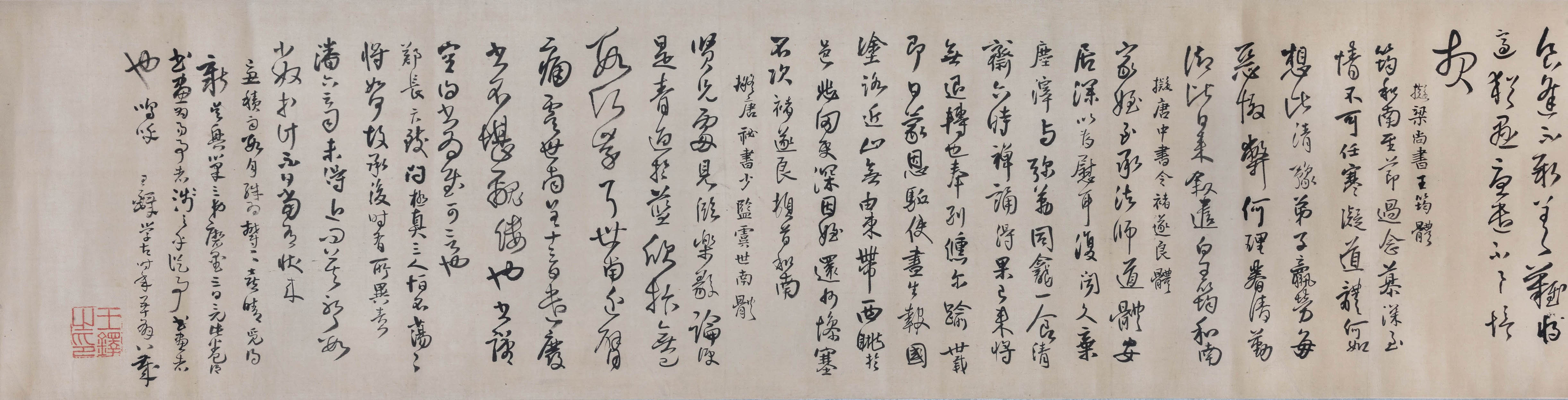

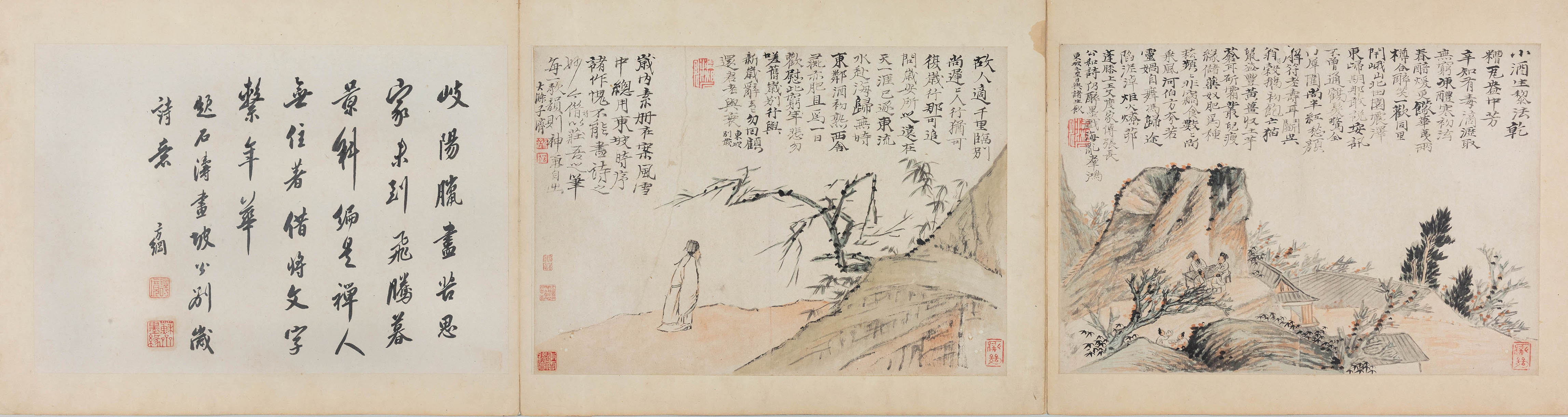

Painting and Calligraphy

Painting and Calligraphy

- Wang Duo (1592-1652), Qing dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Wang Duo (style name Juesi), a native of Mengjin in Henan, was a Presented Scholar of 1622 in the late Ming dynasty. After the fall of the Ming, he served as Grand Academician at the Hongwen Academy under the Qing. He was also appointed as the Minister of Rites and given the posthumous name Wen'an.

This handscroll is composed of three parts: one painting in between two pieces of calligraphy. The beginning calligraphy at the right includes examples copied from the ancients, the contents featuring the styles of various masters from the Han to Tang dynasty. The brushwork flows naturally and at ease with great variety. In the middle is a landscape with clouds rendered in washes of monochrome ink, the veins and structure of the land done mostly in intersecting "hemp-fiber" texture strokes of differing lengths that imbue it with a rich and archaic quality. Finally, at the end on the left is another collection of calligraphy copied after works by ancient masters.

This handscroll is composed of three parts: one painting in between two pieces of calligraphy. The beginning calligraphy at the right includes examples copied from the ancients, the contents featuring the styles of various masters from the Han to Tang dynasty. The brushwork flows naturally and at ease with great variety. In the middle is a landscape with clouds rendered in washes of monochrome ink, the veins and structure of the land done mostly in intersecting "hemp-fiber" texture strokes of differing lengths that imbue it with a rich and archaic quality. Finally, at the end on the left is another collection of calligraphy copied after works by ancient masters.

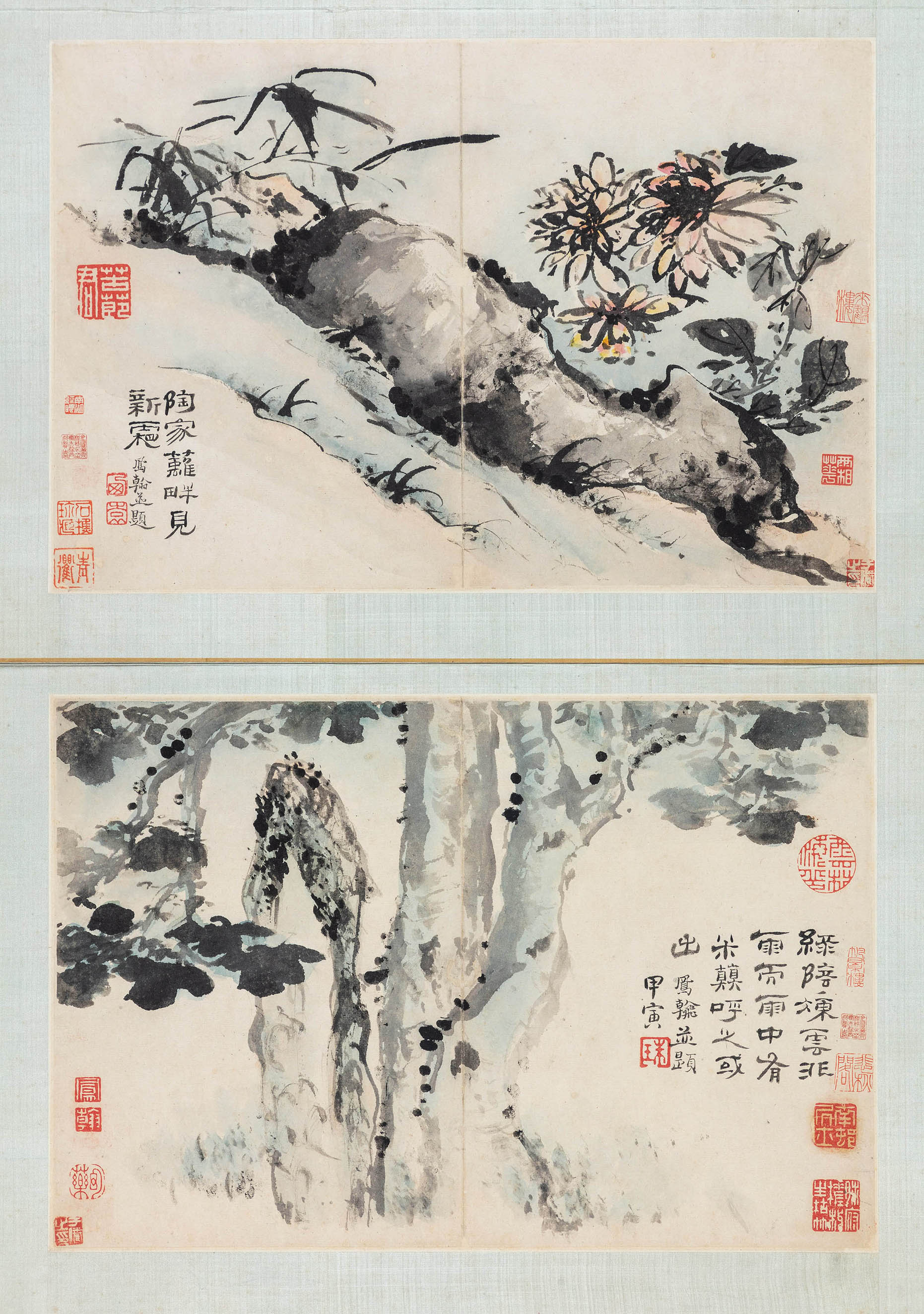

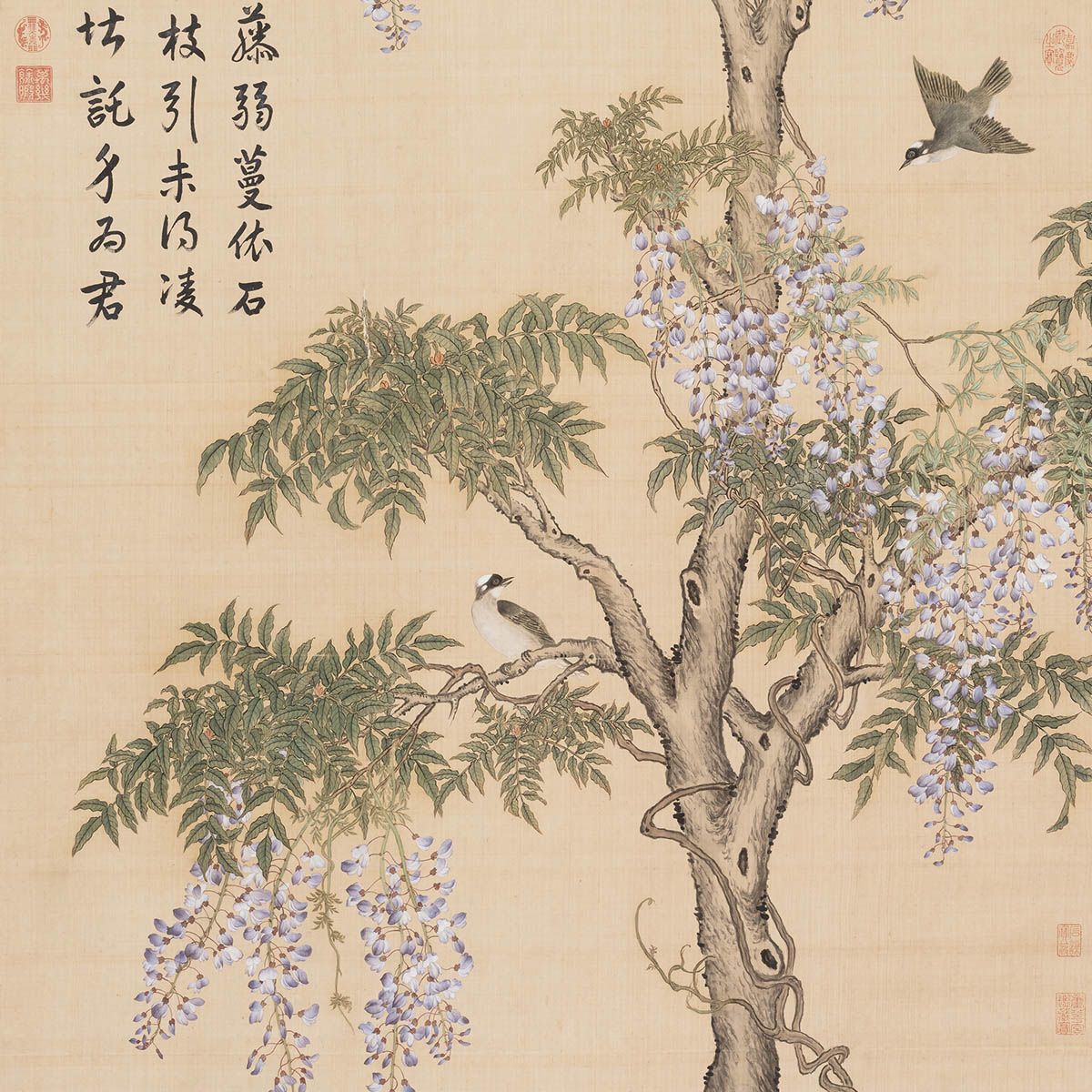

Album of Flowers

Album of Flowers

- Yun Shouping (1633-1690), Qing dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Yun Shouping originally had by the name Ge and the style name Shouping, by which he later went. A native of Wujin in Jiangsu, he excelled at painting flowers in the "boneless" manner of washes. Using no outlines, he directly applied washes of ink and color to depict flowers, a technique for which he became known as the founder of the "Changzhou Painting School."

This album is comprised of twelve leaves of painting that depict peony, begonia, flowering peach, magnolia, wisteria, lotus, orange day-lily, osmanthus, amaranth, chrysanthemum, rose, and chimonanthus subject matter. The coloring is refined and delicate, being beautiful yet otherworldly. The calligraphy is also nimble and spirited, the painting and calligraphy complementing each other for a perfect match.

This album is comprised of twelve leaves of painting that depict peony, begonia, flowering peach, magnolia, wisteria, lotus, orange day-lily, osmanthus, amaranth, chrysanthemum, rose, and chimonanthus subject matter. The coloring is refined and delicate, being beautiful yet otherworldly. The calligraphy is also nimble and spirited, the painting and calligraphy complementing each other for a perfect match.

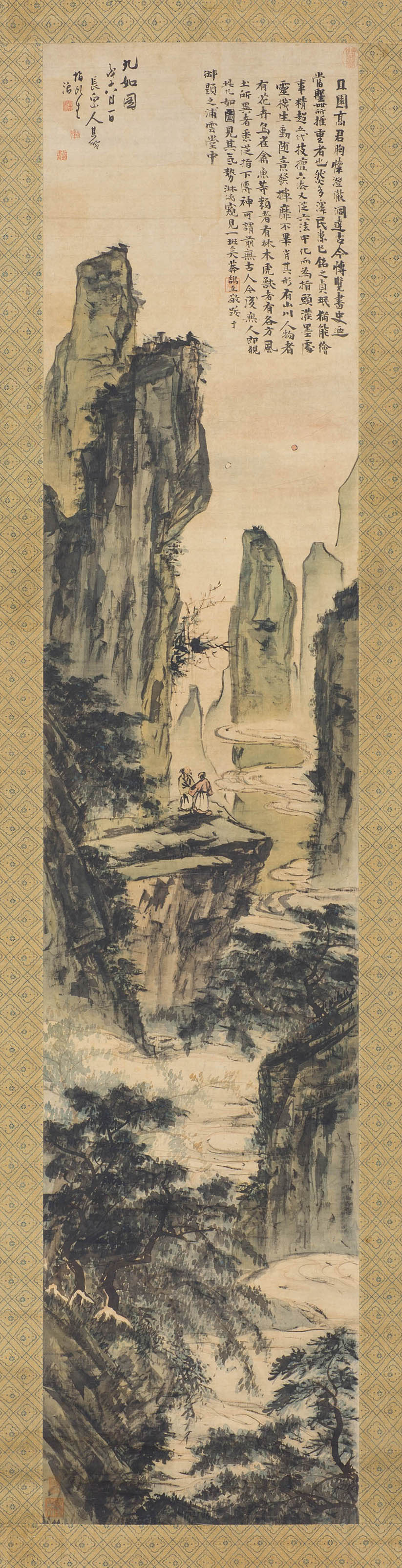

Rising Peaks and Suspended Falls

Rising Peaks and Suspended Falls

- Zhang Ruitu (1570-1644), Ming dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Zhang Ruitu was a calligrapher of the Individualist School in the late Ming dynasty whose style was highly unusual and untrammeled. He also excelled at landscape painting, his works powerful and bold, though very few of them have survived.

The tall and spindly peaks in this painting pierce the enveloping clouds and mists. There is building on the mountaintop, while in the distance one can make out a sail on the river and distant mountains. The innovative composition here went beyond the norms of the time. The signature, "Ruitu of the White-hair Hut," indicates that Zhang painted it in the Chongzhen reign (1611-1644) after retirement. His calligraphy in this phase tended to become more stable and calm. In both technique and spirit, a change can be clearly seen in his style at this time.

The tall and spindly peaks in this painting pierce the enveloping clouds and mists. There is building on the mountaintop, while in the distance one can make out a sail on the river and distant mountains. The innovative composition here went beyond the norms of the time. The signature, "Ruitu of the White-hair Hut," indicates that Zhang painted it in the Chongzhen reign (1611-1644) after retirement. His calligraphy in this phase tended to become more stable and calm. In both technique and spirit, a change can be clearly seen in his style at this time.

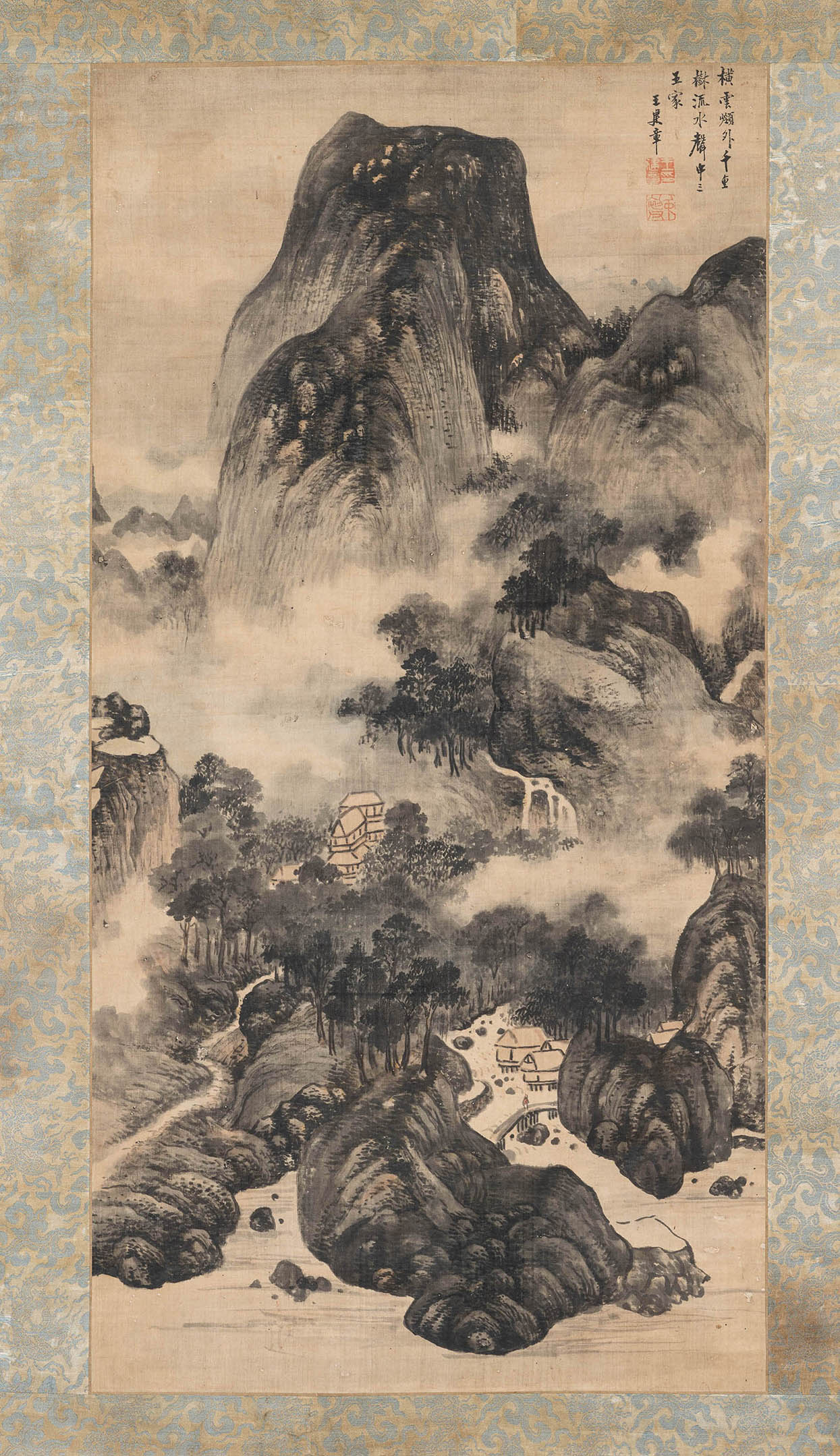

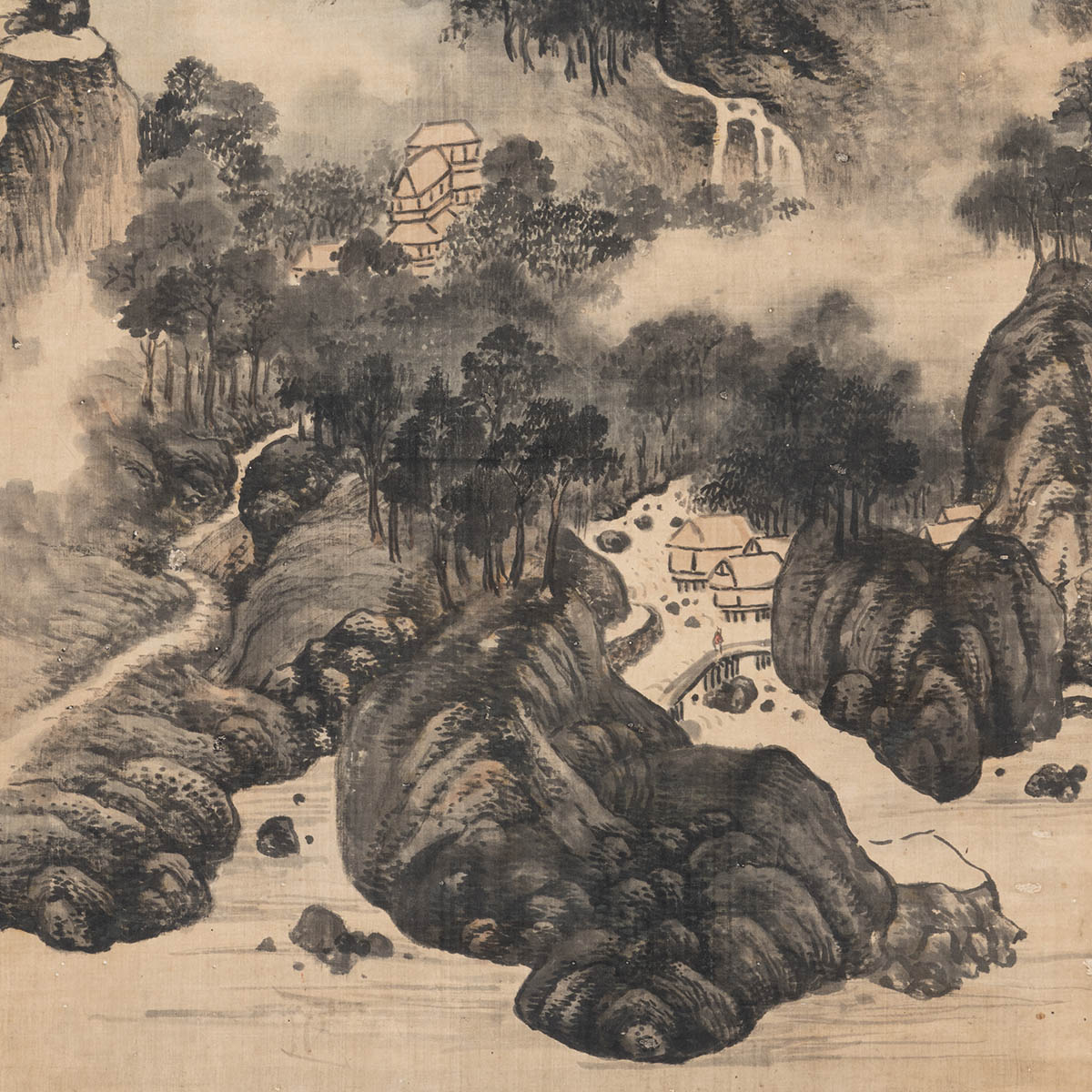

Cloudy Ridges and the Sound of Water

Cloudy Ridges and the Sound of Water

- Wang Jianzhang (17th c.), Ming dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Wang Jianzhang was active from the late Ming to the early Qing period. A native of Quanzhou in Fujian, he was a friend of Zhang Ruitu and once traveled to Japan, where most of his works now survive.

In this painting, mountain forms are layered one atop another with a stream and path winding among them. Some buildings are scattered among the trees, the scenery cloaked in clouds and mists that evoke the lines of poetry inscribed on it: "Clouds beyond ridges with a thousand ‘li' of trees, in the sound of flowing waters are few abodes." The rock forms are rendered in "hemp-fiber" texture strokes, while the trees and misty clouds are done using richly layered ink washes and staining. The brushwork is also strong and powerful, expressing momentum within the hoariness and solidity.

In this painting, mountain forms are layered one atop another with a stream and path winding among them. Some buildings are scattered among the trees, the scenery cloaked in clouds and mists that evoke the lines of poetry inscribed on it: "Clouds beyond ridges with a thousand ‘li' of trees, in the sound of flowing waters are few abodes." The rock forms are rendered in "hemp-fiber" texture strokes, while the trees and misty clouds are done using richly layered ink washes and staining. The brushwork is also strong and powerful, expressing momentum within the hoariness and solidity.

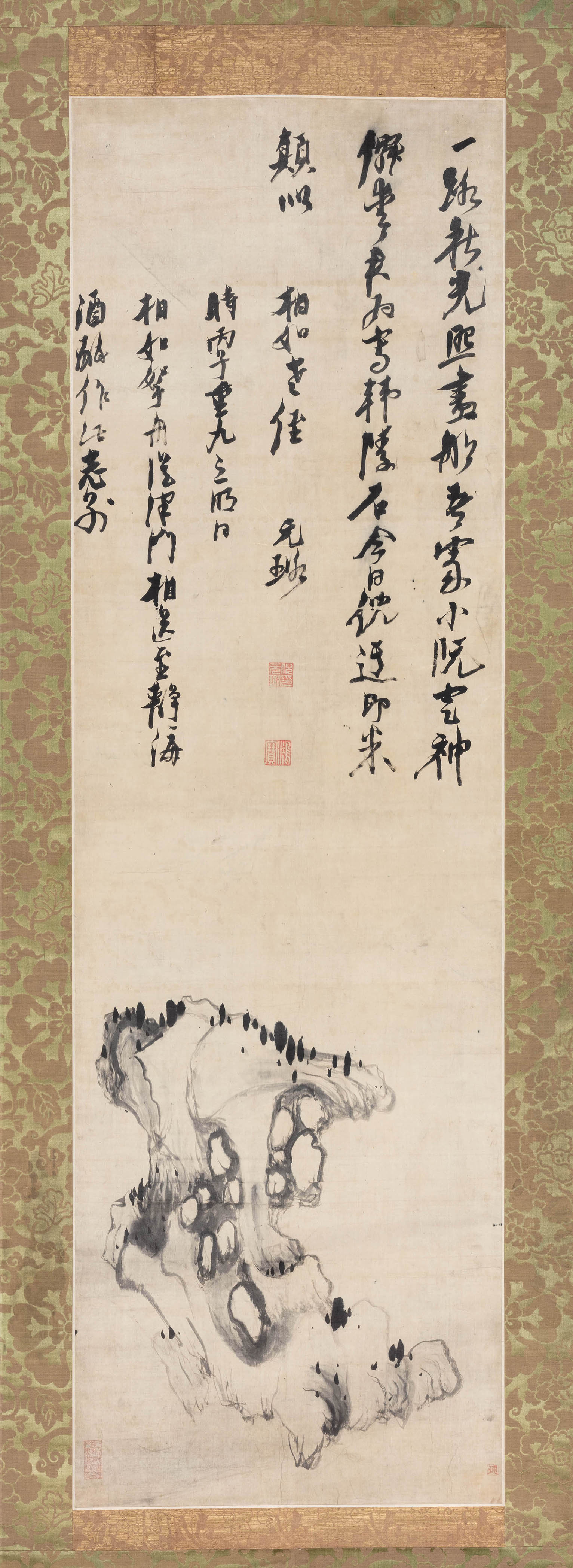

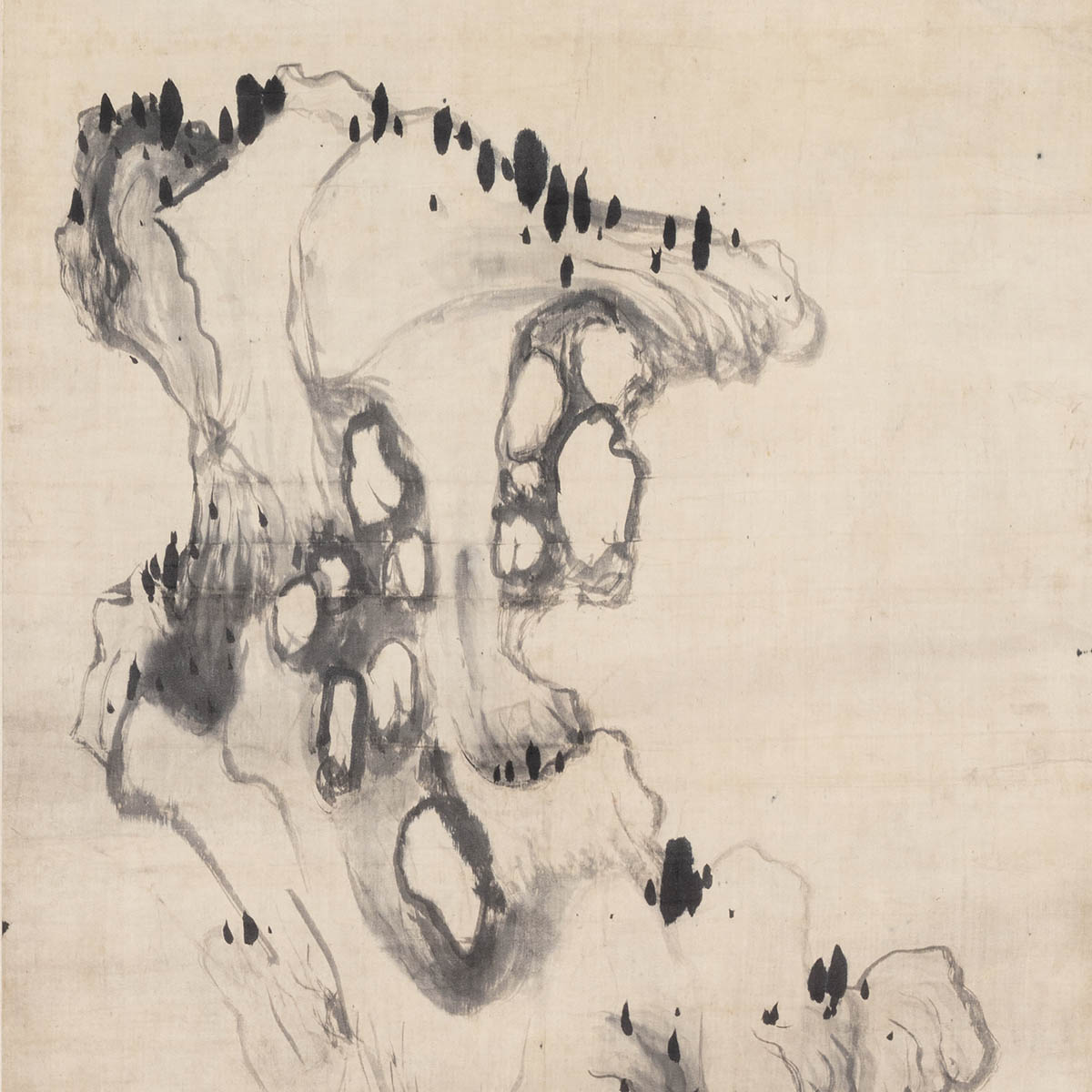

Scholar's Rock

Scholar's Rock

- Ni Yuanlu (1593-1644), Ming dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Ni Yuanlu, a native of Shangyu in Zhejiang, was a calligrapher of the Individualist School in late Ming dynasty. After the rebel leader Li Zicheng (1606-1645) entered the capital and the last Ming emperor committed suicide, Ni also chose to kill himself.

Throughout his life, Ni Yuanlu enjoyed painting landscapes and depictions of pines, bamboo, and scholar's rocks using simple brushwork. He did many paintings of scholar's rocks in monochrome ink, frequently including profound inscriptions on them. This work depicts a rock in outlines featuring ink that ranges from light to dark and wet to dry. The brushwork is full of changes in heaviness, the washes for the parts in shade and the "moss dots" on the bright side giving the work as a whole a dynamic and spirited sense of beauty. Both the eccentricity of the calligraphy and the unusual appearance of the rock reflect the open and straightforward quality of the artist's character.

Throughout his life, Ni Yuanlu enjoyed painting landscapes and depictions of pines, bamboo, and scholar's rocks using simple brushwork. He did many paintings of scholar's rocks in monochrome ink, frequently including profound inscriptions on them. This work depicts a rock in outlines featuring ink that ranges from light to dark and wet to dry. The brushwork is full of changes in heaviness, the washes for the parts in shade and the "moss dots" on the bright side giving the work as a whole a dynamic and spirited sense of beauty. Both the eccentricity of the calligraphy and the unusual appearance of the rock reflect the open and straightforward quality of the artist's character.

Landscape in Colors

Landscape in Colors

- Zhu Da (ca. 1626-ca. 1705), Qing dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Zhu Da, also known by his sobriquet Bada shanren, was one of the famous "Four Monk" painters in artistic circles of the early Qing dynasty.

This painting is a landscape done in light ocher. Foreground rocks in the corner appear with tall trees, the formation of mountain forests dense and the use of brush and ink complex to express a sense of luxuriant growth and vitality that makes the viewer feel as if actually there. The mountain forms in the middle extend into the distance but do not contact the floating clouds and peaks in the far distance, the spatial break imparting a deep sense of separation. The terraced mountain forms create the axis of the composition but have no way of reaching them. On a terrace stands a lonely pavilion that is deserted, adding a further feeling of desolation and seclusion to the scenery.

This painting is a landscape done in light ocher. Foreground rocks in the corner appear with tall trees, the formation of mountain forests dense and the use of brush and ink complex to express a sense of luxuriant growth and vitality that makes the viewer feel as if actually there. The mountain forms in the middle extend into the distance but do not contact the floating clouds and peaks in the far distance, the spatial break imparting a deep sense of separation. The terraced mountain forms create the axis of the composition but have no way of reaching them. On a terrace stands a lonely pavilion that is deserted, adding a further feeling of desolation and seclusion to the scenery.

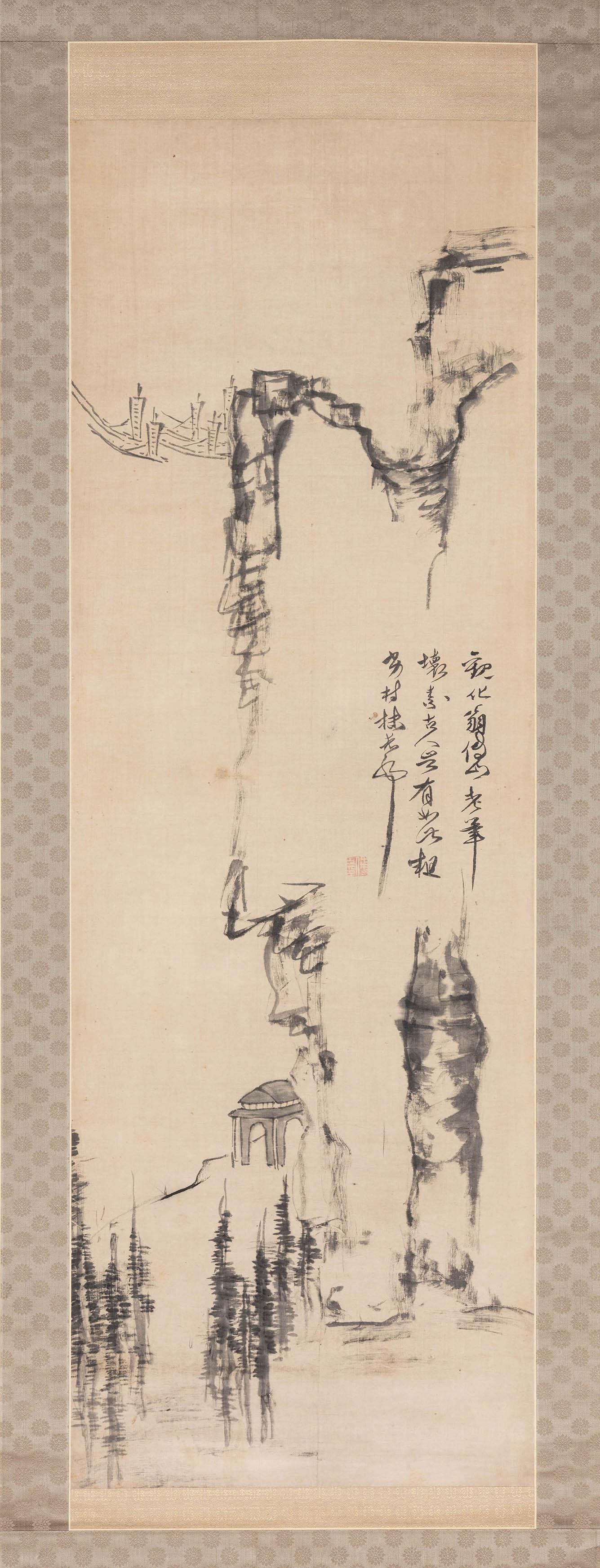

Precipitous Cliffs and Flying Sails

Precipitous Cliffs and Flying Sails

- Fu Shan (1607-1684), Qing dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Fu Shan went by other names, including Guanhuaweng. He practiced medicine and was also a calligrapher of the late Ming dynasty.

Depicted in this painting is a tall precipitous cliff, a solitary building, foreground trees, and distant boats. Since the painting employs a large area of blank space to highlight the dramatic composition along with unrestrained applications of brush and ink, the lower portion of the cliff face below the inscription is easily mistaken as a rocky column, and what was originally space for the water's surface is easily seen as a mountain form. This kind of "figure-ground illusion" in painting, because it makes the viewer unable to directly interpret the surface and thus cause anxiety, has been associated with the social chaos in the late Ming and early Qing period along with the aesthetics of "creativity" and "originality" at the time.

Depicted in this painting is a tall precipitous cliff, a solitary building, foreground trees, and distant boats. Since the painting employs a large area of blank space to highlight the dramatic composition along with unrestrained applications of brush and ink, the lower portion of the cliff face below the inscription is easily mistaken as a rocky column, and what was originally space for the water's surface is easily seen as a mountain form. This kind of "figure-ground illusion" in painting, because it makes the viewer unable to directly interpret the surface and thus cause anxiety, has been associated with the social chaos in the late Ming and early Qing period along with the aesthetics of "creativity" and "originality" at the time.

Album of Landscapes and Flowers

Album of Landscapes and Flowers

- Gao Fenghan (1683-1749), Qing dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Gao Fenghan (style name Xiyuan, sobriquet Nancun) excelled at the arts of seal carving, painting, and calligraphy. He was a famous artist of the Yangzhou School in the middle Qing dynasty.

This album consists of ten leaves with paintings depicting flower, landscape, rock, and tree subjects. The artist's inscription indicates that they were done in "finger ink" in the equivalent of 1734. Gao used his finger or even the palm of his hand instead of a brush to do each work. The lines are fluid and dashing at times, untrammeled and mature at others. The light washes of coloring skillfully highlight scenery that overflows with life. The atmosphere throughout the album is pure and elegant, equaling the beautifully boundless and profound style of the famous earlier finger painter Gao Qipei (1660-1734).

This album consists of ten leaves with paintings depicting flower, landscape, rock, and tree subjects. The artist's inscription indicates that they were done in "finger ink" in the equivalent of 1734. Gao used his finger or even the palm of his hand instead of a brush to do each work. The lines are fluid and dashing at times, untrammeled and mature at others. The light washes of coloring skillfully highlight scenery that overflows with life. The atmosphere throughout the album is pure and elegant, equaling the beautifully boundless and profound style of the famous earlier finger painter Gao Qipei (1660-1734).

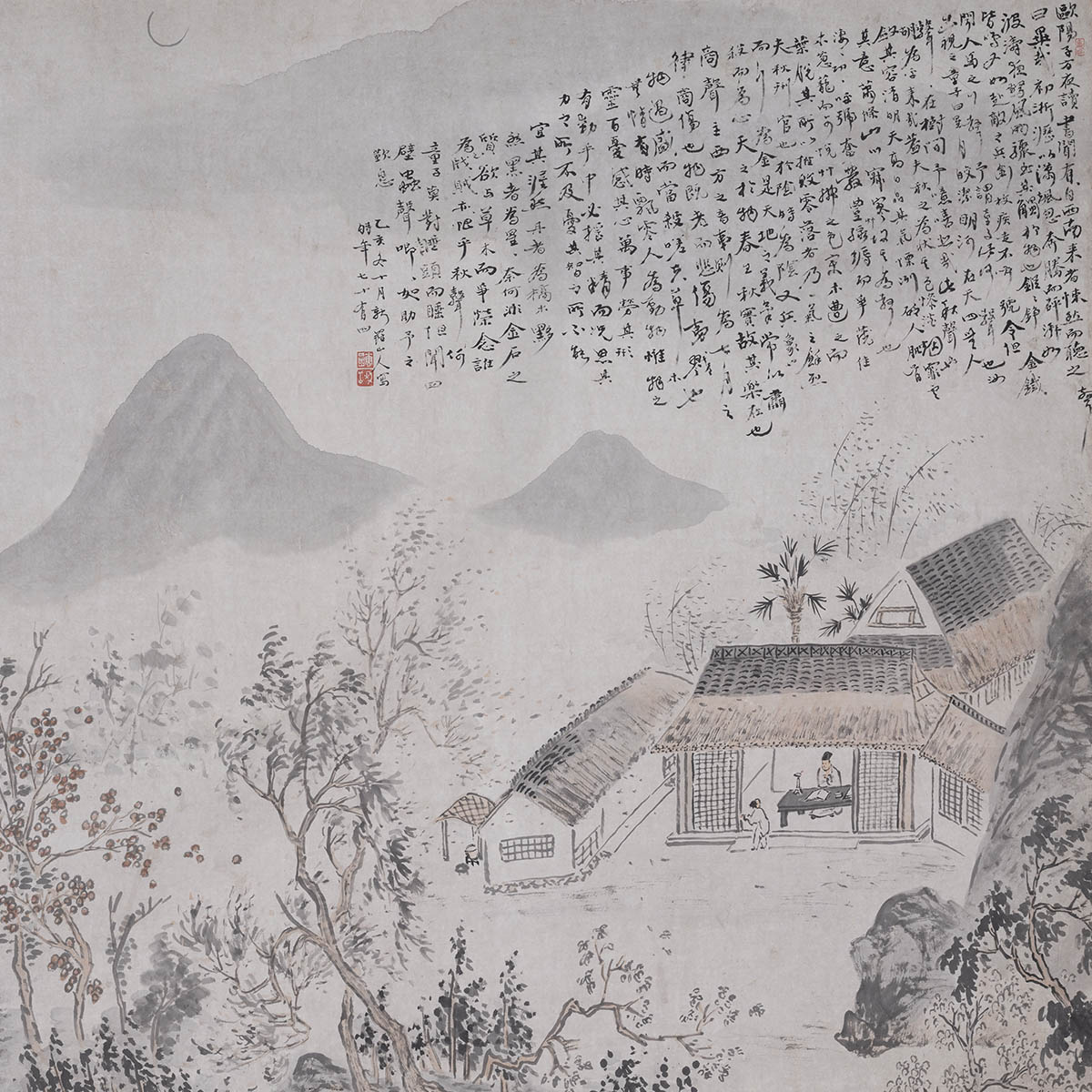

The Idea of "Ode to the Sounds of Autumn"

The Idea of "Ode to the Sounds of Autumn"

- Hua Yan (1683-1756), Qing dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Hua Yan, a native of Shanghang in Fujian, had the style name Qiuyue and such sobriquets as Xinluo shanren and Ligou jushi.

This painting depicts a moon high above and in contrast with a small lamp below. Two figures are in conversation as the tree leaves sway, the scenery illustrating "Ode to the Sounds of Autumn" by Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072) of the Northern Song: "I ask the child, ‘What is that sound? Go out to have a look.' The child says, ‘The moon and stars are clear, a bright river is in the sky. Without the sound of people around, the sound is in the trees.'" According to the inscription, this work was done in the equivalent of 1755.

This painting depicts a moon high above and in contrast with a small lamp below. Two figures are in conversation as the tree leaves sway, the scenery illustrating "Ode to the Sounds of Autumn" by Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072) of the Northern Song: "I ask the child, ‘What is that sound? Go out to have a look.' The child says, ‘The moon and stars are clear, a bright river is in the sky. Without the sound of people around, the sound is in the trees.'" According to the inscription, this work was done in the equivalent of 1755.

Old Tree and Jackdaws

Old Tree and Jackdaws

- Cai Jia (fl. mid-18th c.), Qing dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Cai Jia (style name Songyuan; sobriquets Xuetang and Lüting) was a native of Danyang in Jiangsu who resided in Yangzhou. He was later included in the Jingjiang school of painting.

The artist did this painting in 1756 and inscribed it as being done in a brush method imitating the Yuan dynasty master Ni Zan (1301-1374). The scenery consists of a rocky slope with water flowing to demarcate the foreground. A withered tree stands to the right on the bank and extends into the middle, the background filled with void and accentuated by a flock of jackdaws receding into the distance to further suggest space. The artist used simple and slightly dry ink with short dabs of the brush, building up the forms and textures of the objects in the scenery to create a pure and frigid effect.

The artist did this painting in 1756 and inscribed it as being done in a brush method imitating the Yuan dynasty master Ni Zan (1301-1374). The scenery consists of a rocky slope with water flowing to demarcate the foreground. A withered tree stands to the right on the bank and extends into the middle, the background filled with void and accentuated by a flock of jackdaws receding into the distance to further suggest space. The artist used simple and slightly dry ink with short dabs of the brush, building up the forms and textures of the objects in the scenery to create a pure and frigid effect.

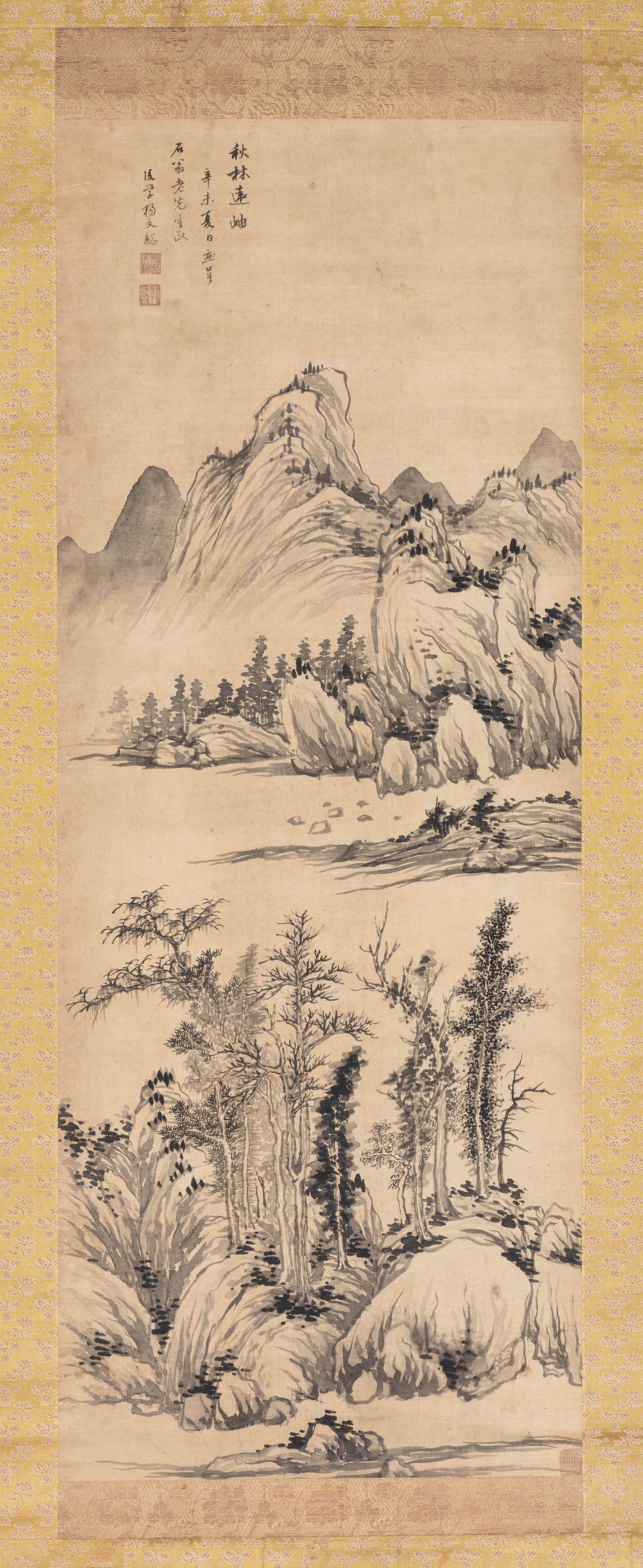

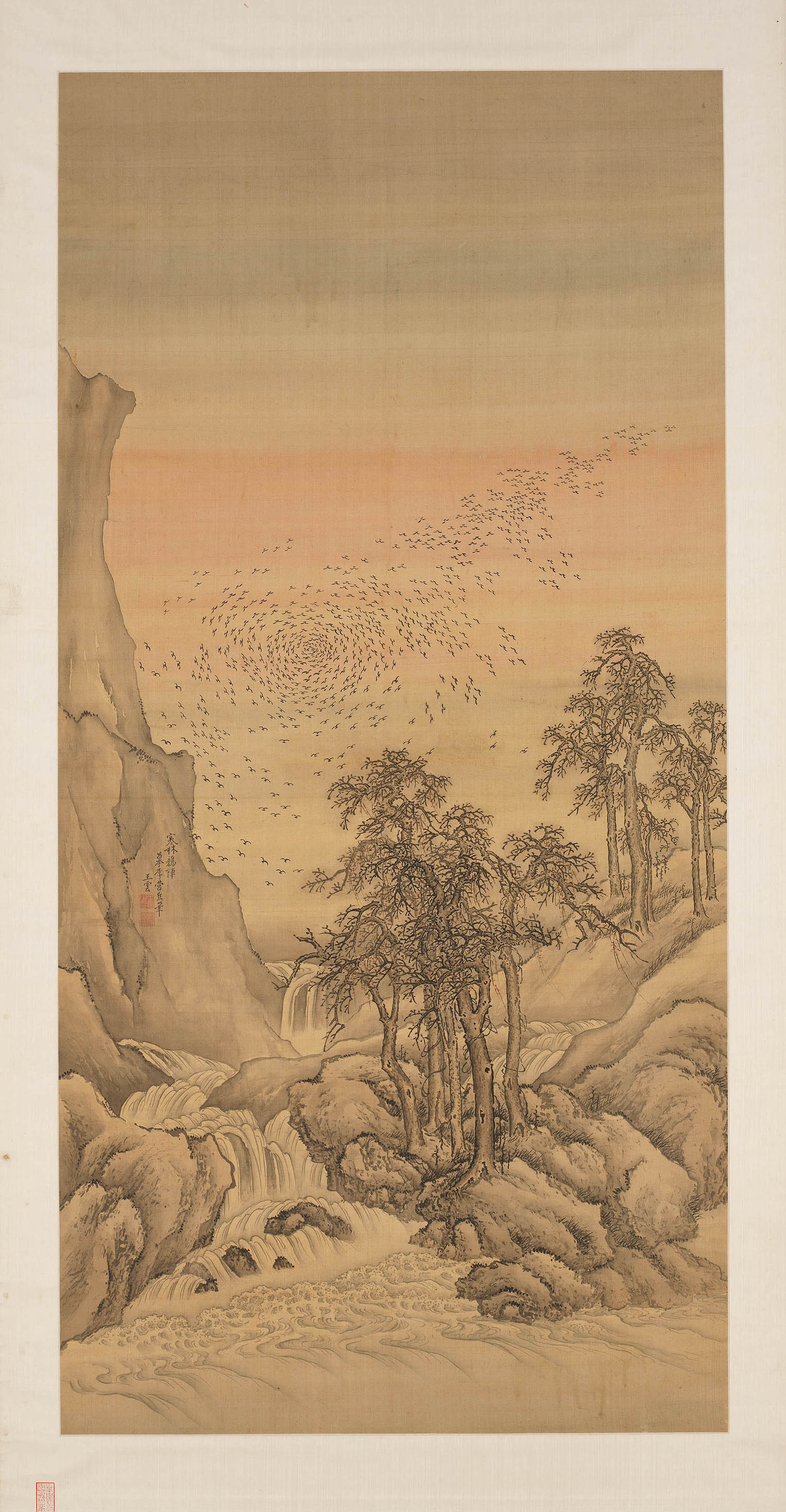

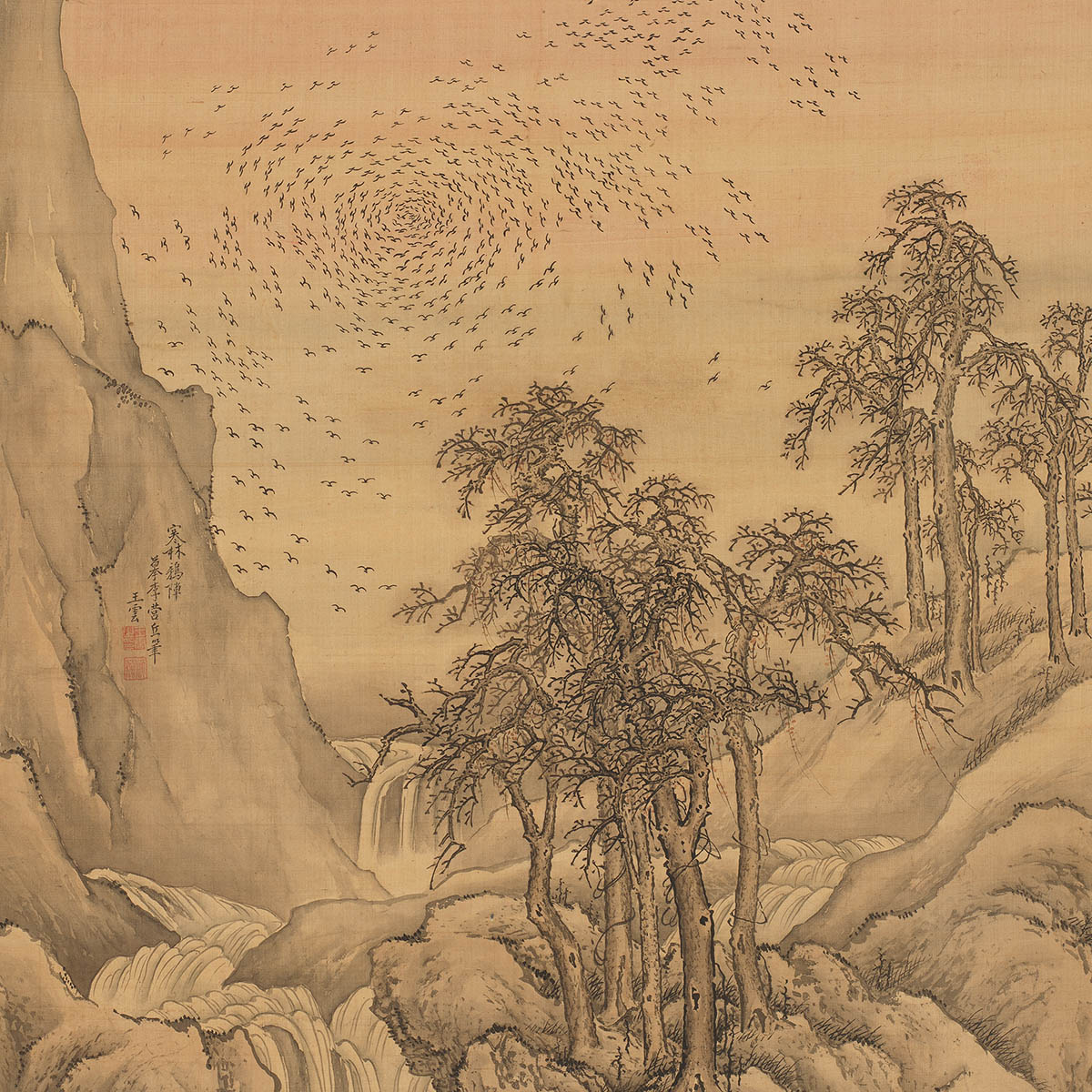

Imitating Li Cheng's "Wintry Trees and a Flock of Jackdaws"

Imitating Li Cheng's "Wintry Trees and a Flock of Jackdaws"

- Wang Yun (1652-after 1735), Qing dynasty

- Collection of the National Palace Museum

Wang Yun (style name Hancao), a native of Gaoyou in Jiangsu, painted figures and buildings in a style similar to that of the Ming master Qiu Ying (ca. 1494-1552). He served the Qing court during the Kangxi reign (1661-1722) and was a member of a group that painted the "Kangxi Southern Inspection" handscrolls. Famous in the Jiang-Huai region, he was also a renowned Yangzhou painter in the early Qing.

Ms. Lo Sun Ping-tsung donated this painting to the National Palace Museum that depicts a stream flowing among rocks by a wintry forest at sunset with a flock of jackdaws. In the foreground is a slope rendered with texture strokes that are fine and energetic, while the background cliff is done in large swaths of ink washes. The subject of wintry trees is most often associated with the style of the Northern Song painter Li Cheng (919-967), which accounts for the inscription here stating it was done "in imitation of the brush of Li Yingchiu (Cheng)." The flock of returning jackdaws form a whorl against the backdrop of rosy-colored skies at sunset for a visually dynamic effect.

Ms. Lo Sun Ping-tsung donated this painting to the National Palace Museum that depicts a stream flowing among rocks by a wintry forest at sunset with a flock of jackdaws. In the foreground is a slope rendered with texture strokes that are fine and energetic, while the background cliff is done in large swaths of ink washes. The subject of wintry trees is most often associated with the style of the Northern Song painter Li Cheng (919-967), which accounts for the inscription here stating it was done "in imitation of the brush of Li Yingchiu (Cheng)." The flock of returning jackdaws form a whorl against the backdrop of rosy-colored skies at sunset for a visually dynamic effect.

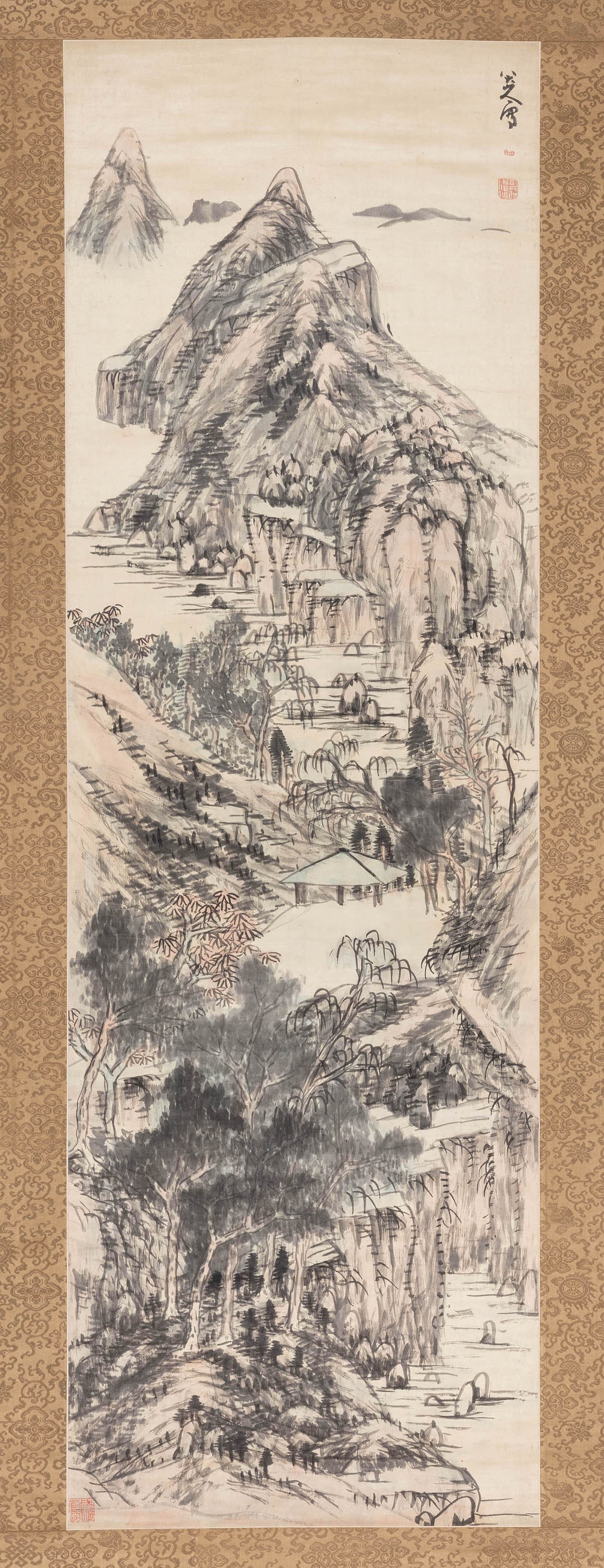

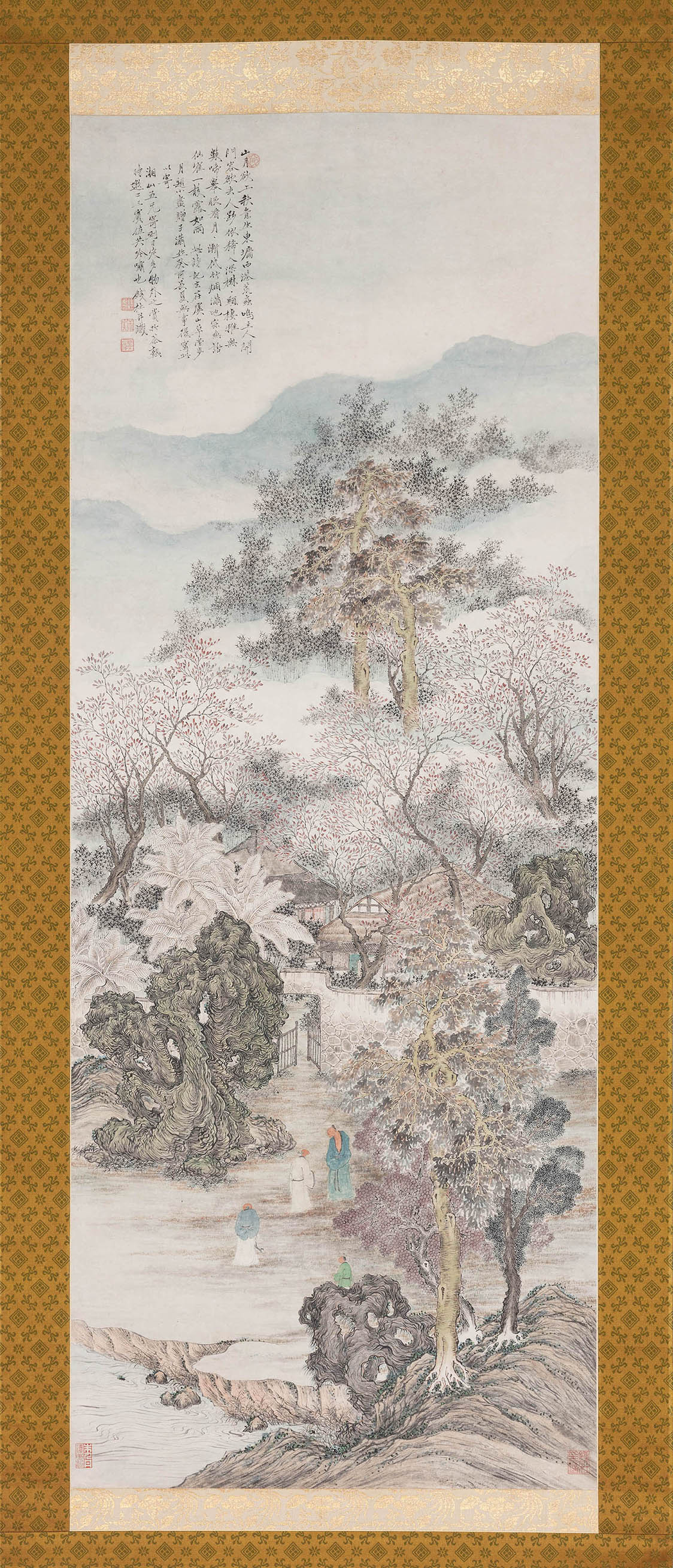

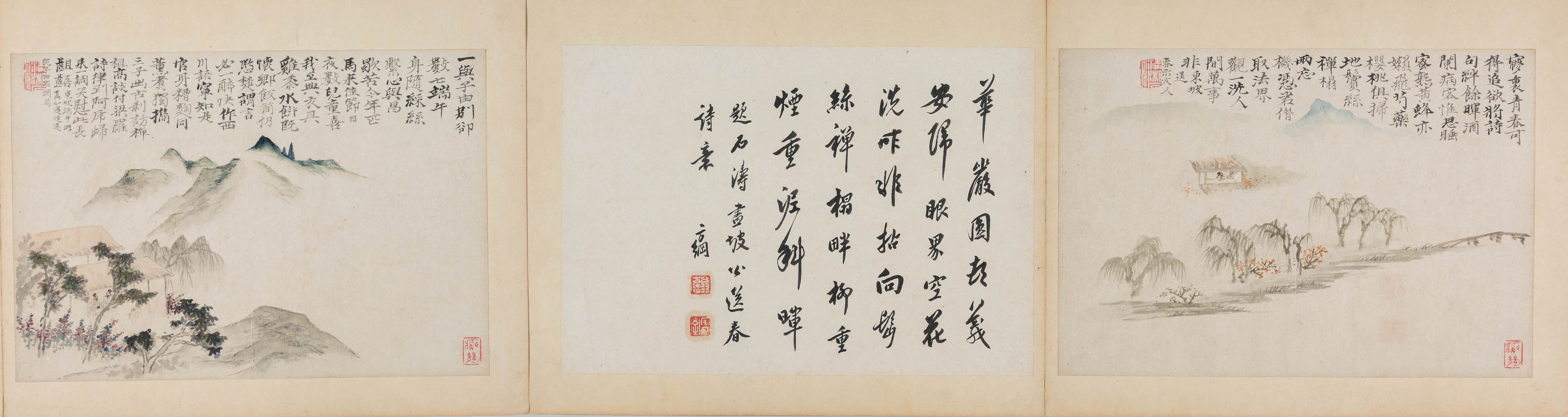

The Poetic Idea of Strolling Under the Moon at a Thatched Hut on Mount Yu

The Poetic Idea of Strolling Under the Moon at a Thatched Hut on Mount Yu

- Qian Du (1763-1844), Qing dynasty

- Collection of the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts

Qian Du was an innovative painter in the style associated with the Ming literati master Wen Zhengming (1470-1559) working in a manner of his own during the nineteenth century. He developed a unique interpretation of the refined and beautiful yet sometimes decorative mode in the Wen School.