Introduction

To meet the need for recording information and ideas, unique forms of calligraphy (the art of writing) have been part of the Chinese cultural tradition through the ages. Naturally finding applications in daily life, calligraphy still serves as a continuous link between the past and the present. The development of calligraphy, long a subject of interest in Chinese culture, is the theme of this exhibit, which presents to the public selections from the National Palace Museum collection arranged in chronological order for a general overview.

The dynasties of the Qin (221-206 BCE) and Han (206 BCE-220 CE) represent a crucial era in the history of Chinese calligraphy. On the one hand, diverse forms of brushed and engraved "ancient writing" and "large seal" scripts were unified into a standard type known as "small seal." On the other hand, the process of abbreviating and adapting seal script to form a new one known as "clerical" (emerging previously in the Eastern Zhou dynasty) was finalized, thereby creating a universal script in the Han dynasty. In the trend towards abbreviation and brevity in writing, clerical script continued to evolve and eventually led to the formation of "cursive," "running," and "standard" script. Since changes in writing did not take place overnight, several transitional styles and mixed scripts appeared in the chaotic post-Han period, but these transformations eventually led to established forms for brush strokes and characters.

The dynasties of the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) represent another important period in Chinese calligraphy. Unification of the country brought calligraphic styles of the north and south together as brushwork methods became increasingly complete. Starting from this time, standard script would become the universal form through the ages. In the Song dynasty (960-1279), the tradition of engraving modelbook copies became a popular way to preserve the works of ancient masters. Song scholar-artists, however, were not satisfied with just following tradition, for they considered calligraphy also as a means of creative and personal expression.

Revivalist calligraphers of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), in turning to and advocating revivalism, further developed the classical traditions of the Jin and Tang dynasties. At the same time, notions of artistic freedom and liberation from rules in calligraphy also gained momentum, becoming a leading trend in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Among the diverse manners of this period, the elegant freedom of semi-cursive script contrasts dramatically with more conservative manners. Thus, calligraphers with their own styles formed individual paths that were not overshadowed by the mainstream of the time.

Starting in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), scholars increasingly turned to inspiration from the rich resource of ancient works inscribed with seal and clerical script. Influenced by an atmosphere of closely studying these antiquities, Qing scholars became familiar with steles and helped create a trend in calligraphy that complemented the Modelbook school. Thus, the Stele school formed yet another link between past and present in its approach to tradition, in which seal and clerical script became sources of innovation in Chinese calligraphy.

Selections

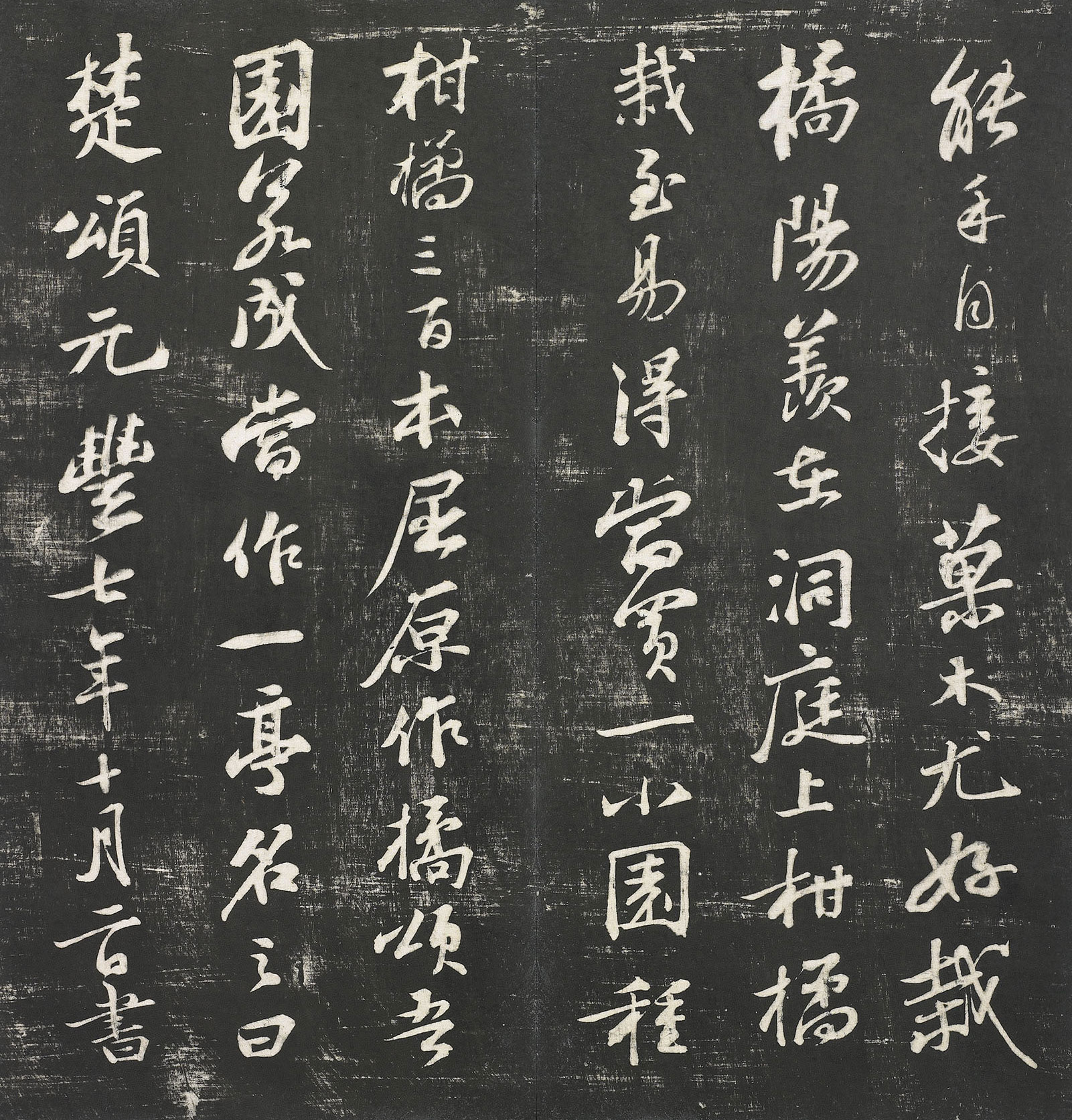

Chusong Modelbook

- Su Shi, Song dynasty

Su Shi (1037-1101), whose style name was Zizhan and whose sobriquet was Dongpo ("Eastern Slope"), was one of the four masters of Northern Song dynasty calligraphy.

In 1084, while Su Shi was traveling overwater to Yangxian (Yixing in present day Jiangsu province), he wrote the contents of the "Chusong Modelbook," which express his desire to plant mandarin oranges and build a pavilion in this region. Su's original inscription is lost, and only block-printed editions remain. This modelbook, written entirely in running script (xingshu), was donated to the NPM by Mr. Tan Boyu and Mr. Tan Jifu. It is distinguished by lines that show generous thickness as well as discretion where they make rounded turns, but are decisive and forceful where they make angular turns. The characters fluctuate in size, given rein to gradually grow until brought to sudden stops. The overall composition is unrestrainedly natural and utterly unaffected—this is clearly a work of excellence written in a flourish of inspiration.

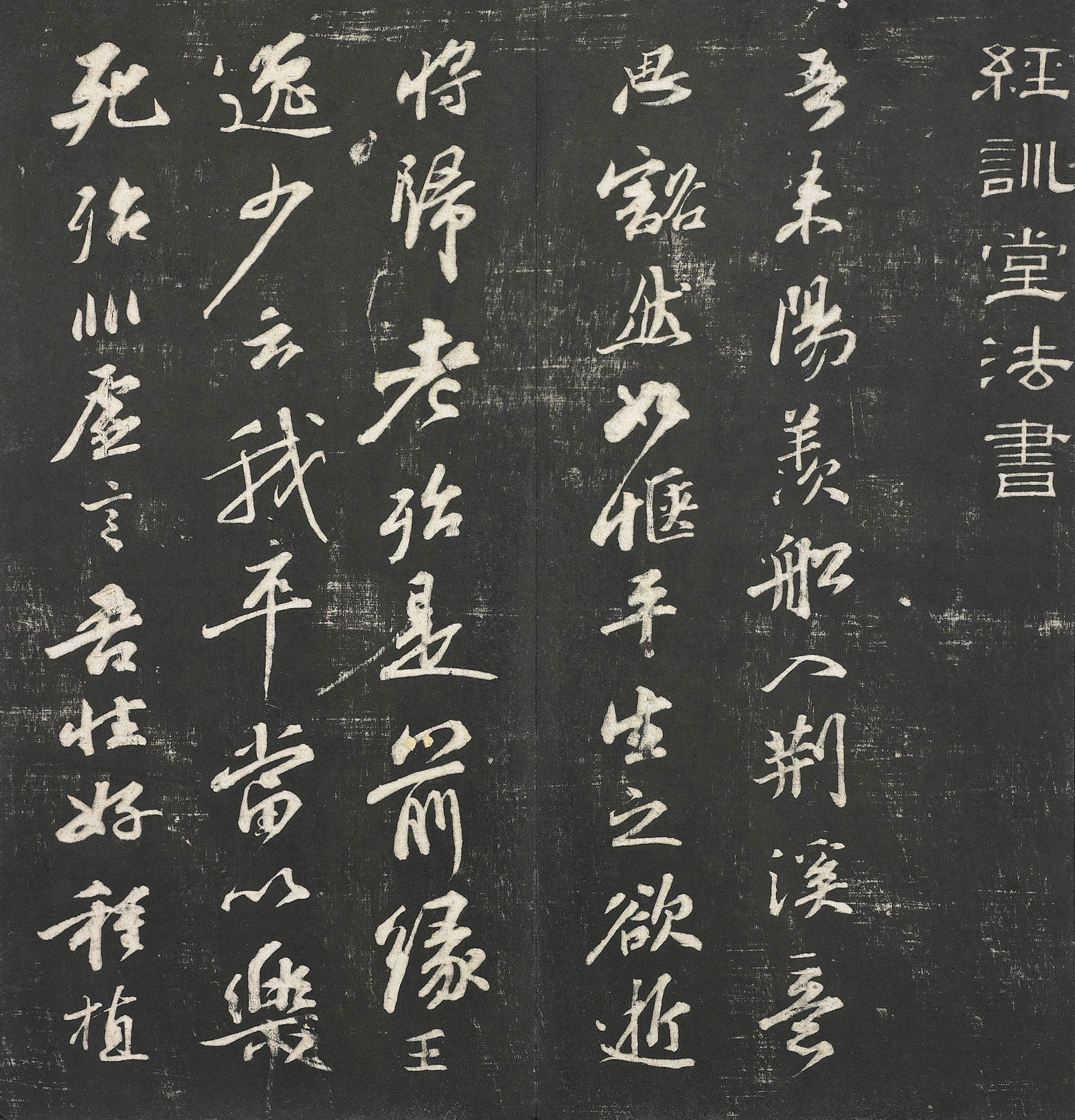

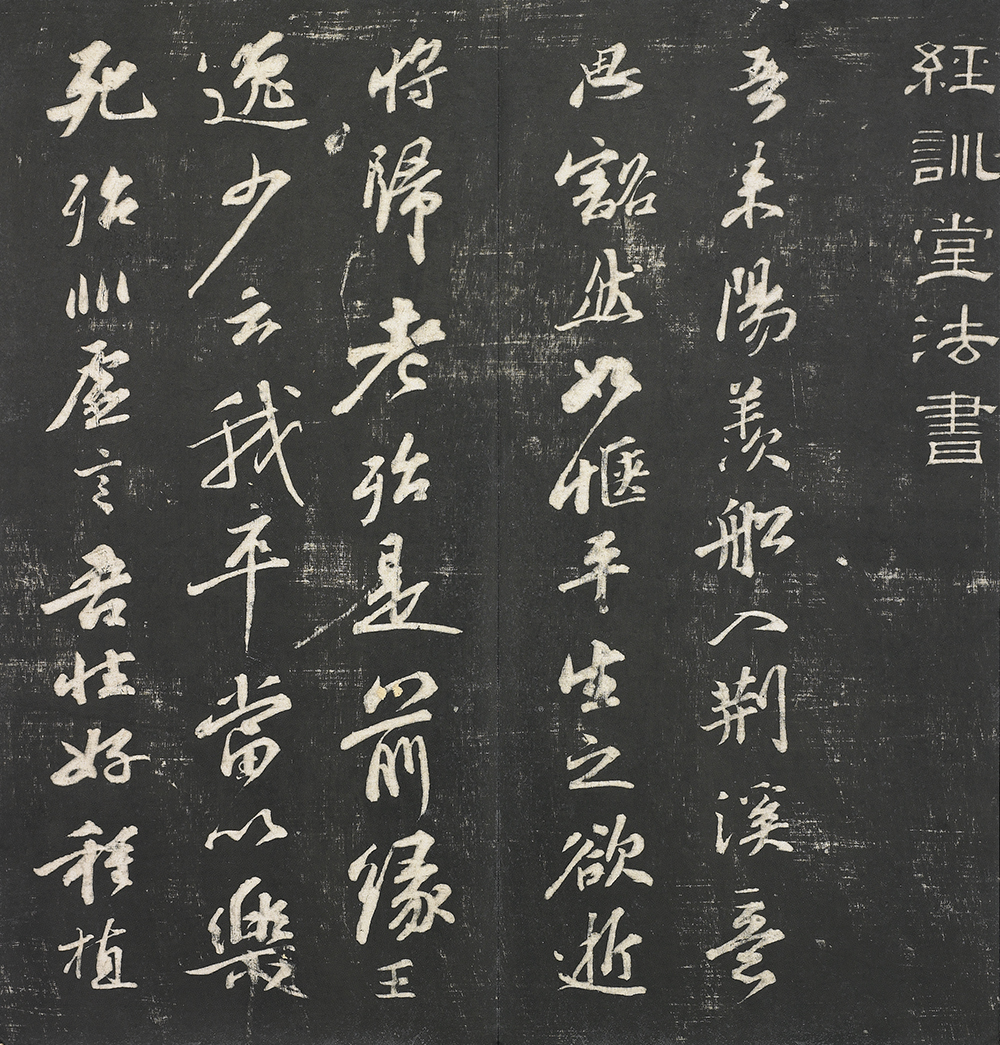

Roumao Modelbook

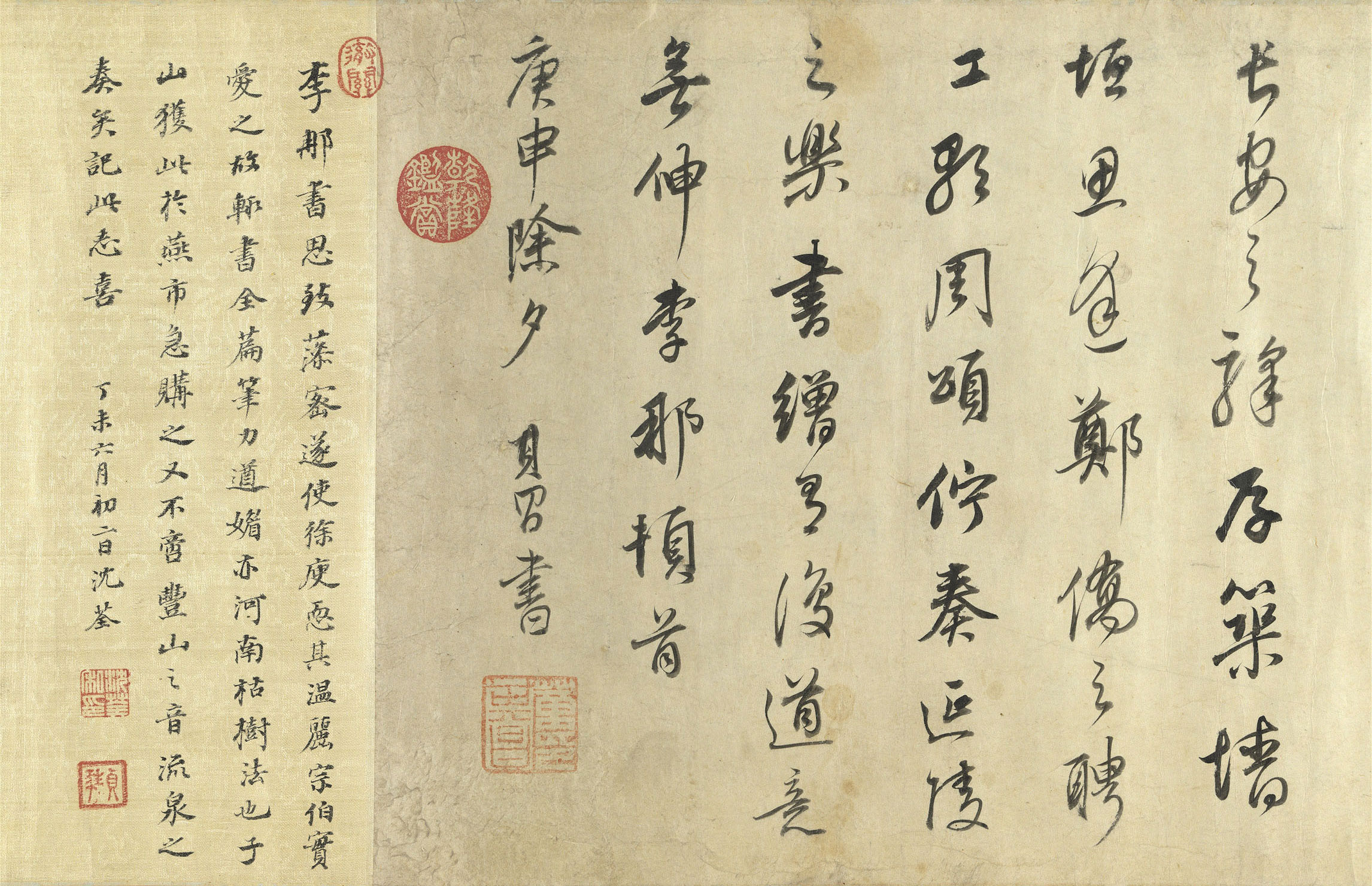

- Zhao Mengfu, Yuan dynasty

Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) was a leader in Yuan dynasty literati painting and calligraphy. The artistic principles he espoused, which called for a return to ancient ways, had a far-reaching influence.

The contents "Roumao Modelbook" were originally a formal letter included along with a gift. "Roumao" is a reference to sheep. The letter was written in running script (xingshu), with the occasional appearance of draft cursive (zhangcao). There are rich permutations in the sizes of the characters and the thicknesses of the lines. The columns of writing present dignified straightness, while the overall composition is one of delightfully elegant disorder. This calligraphy is Wang Xizhi's (303-361) stylistic descendant, but it includes frequent use of decisive, heavy downward pressure on the brush and full exposure of the brush's tip. These techniques set off the interactions between the angular and rounded turns in the characters' lines, as well as the quick traces of the brush's movements and the relationship between dots and lines, increasing the work's charming sense of fluency.

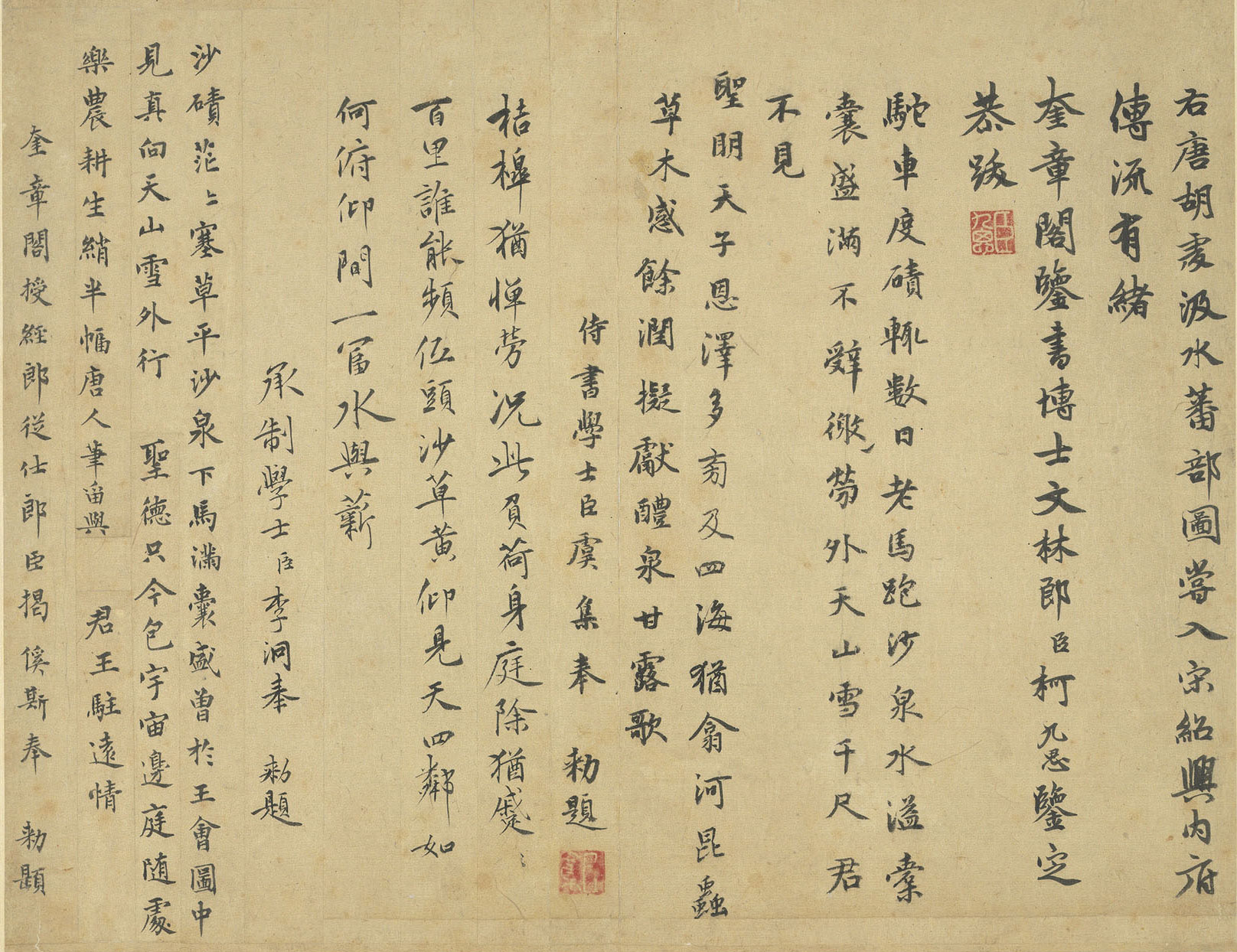

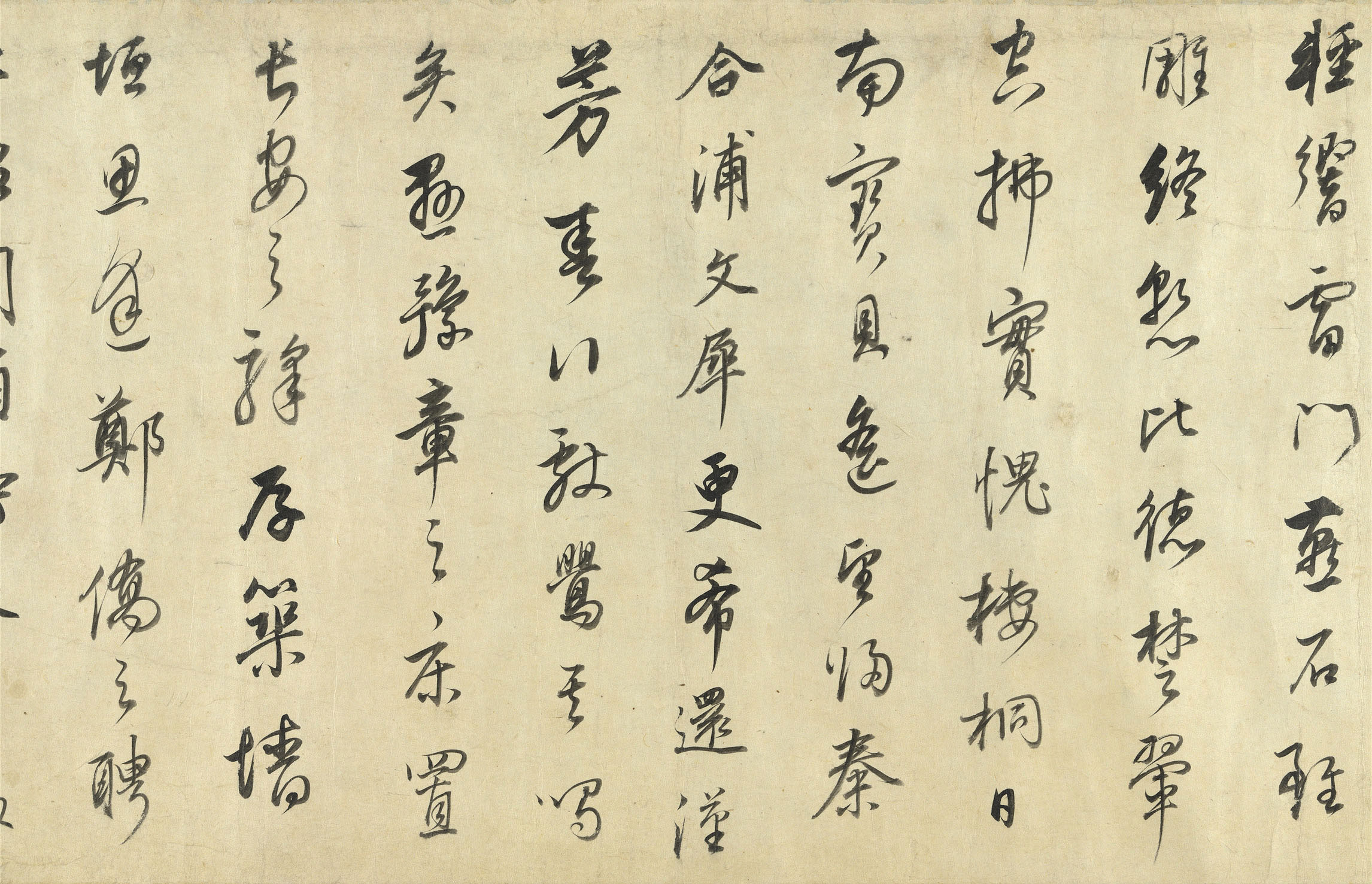

Poems Affixed to Paintings

- Various, Yuan dynasty

This piece comprises the calligraphic works of Ke Jiusi (1290-1343), Yu Ji (1272-1348), Li Jiong (1274-1332), and Jie Xisi (1274-1344), all of whom were renowned scholar-officials associated with the Academy of the Pavilion of the Star of Literature during the reign of Yuan dynasty emperor Wenzong (1304-1332). Ke's inscription is a colophon he wrote after being ordered by the emperor to appraise a painting by a Tang dynasty artist, while the other three calligraphers wrote poems. The four men's inscriptions are distinct in appearance, with stylistic elements that trace to Ouyang Xun (557-641), Yu Shinan (558-638), and Zhu Suiliang (596-658). These characteristics reflect that the four scholars traversed the works of Tang dynasty masters in their attempts to reach back to the spirit of the even earlier Jin dynasty master Wang Xizhi (303-361). The Yuan dynasty conviction that "Calligraphy's ancestry is found in the Jin and Tang dynasties" is embodied in this piece.

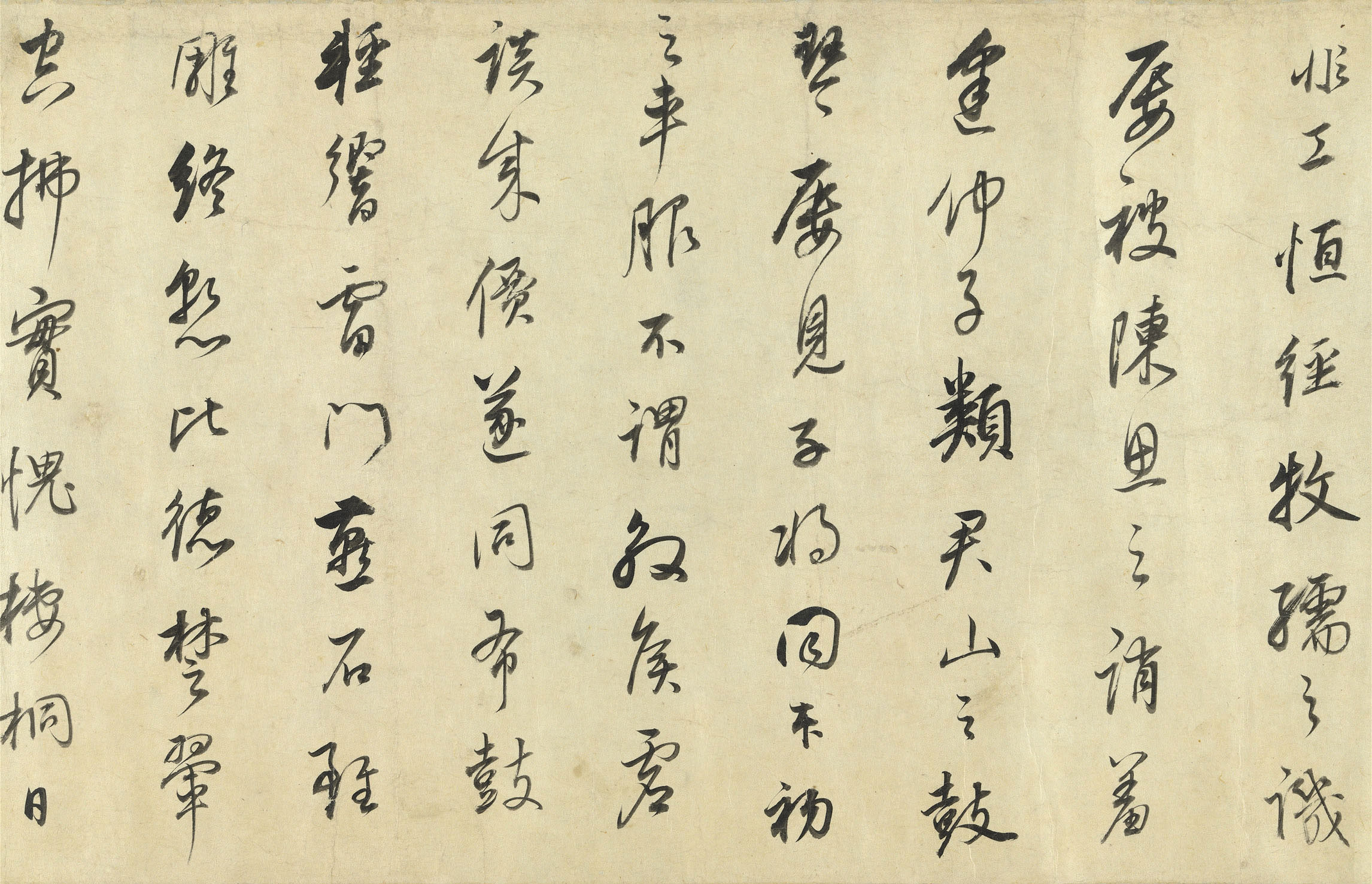

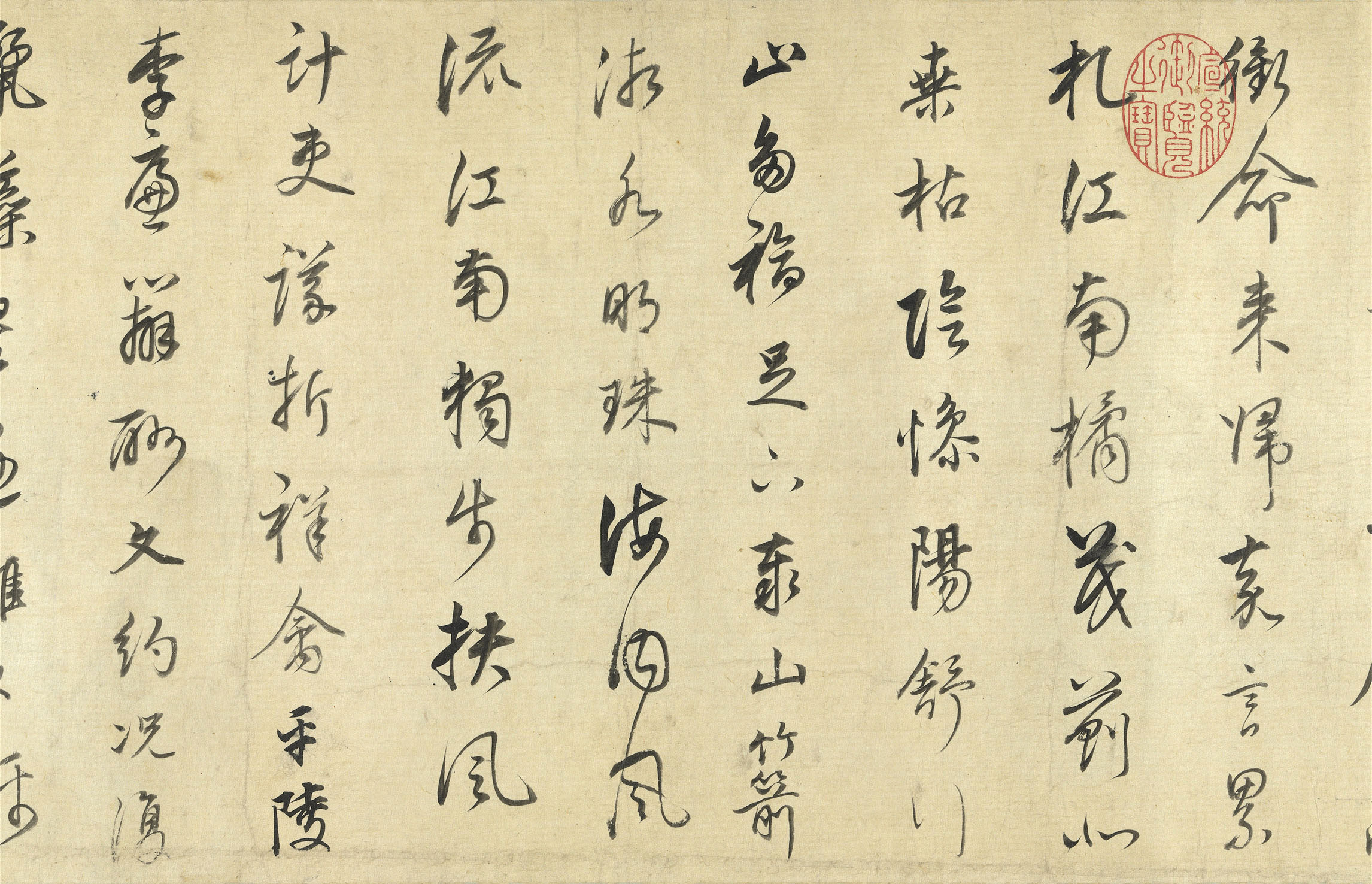

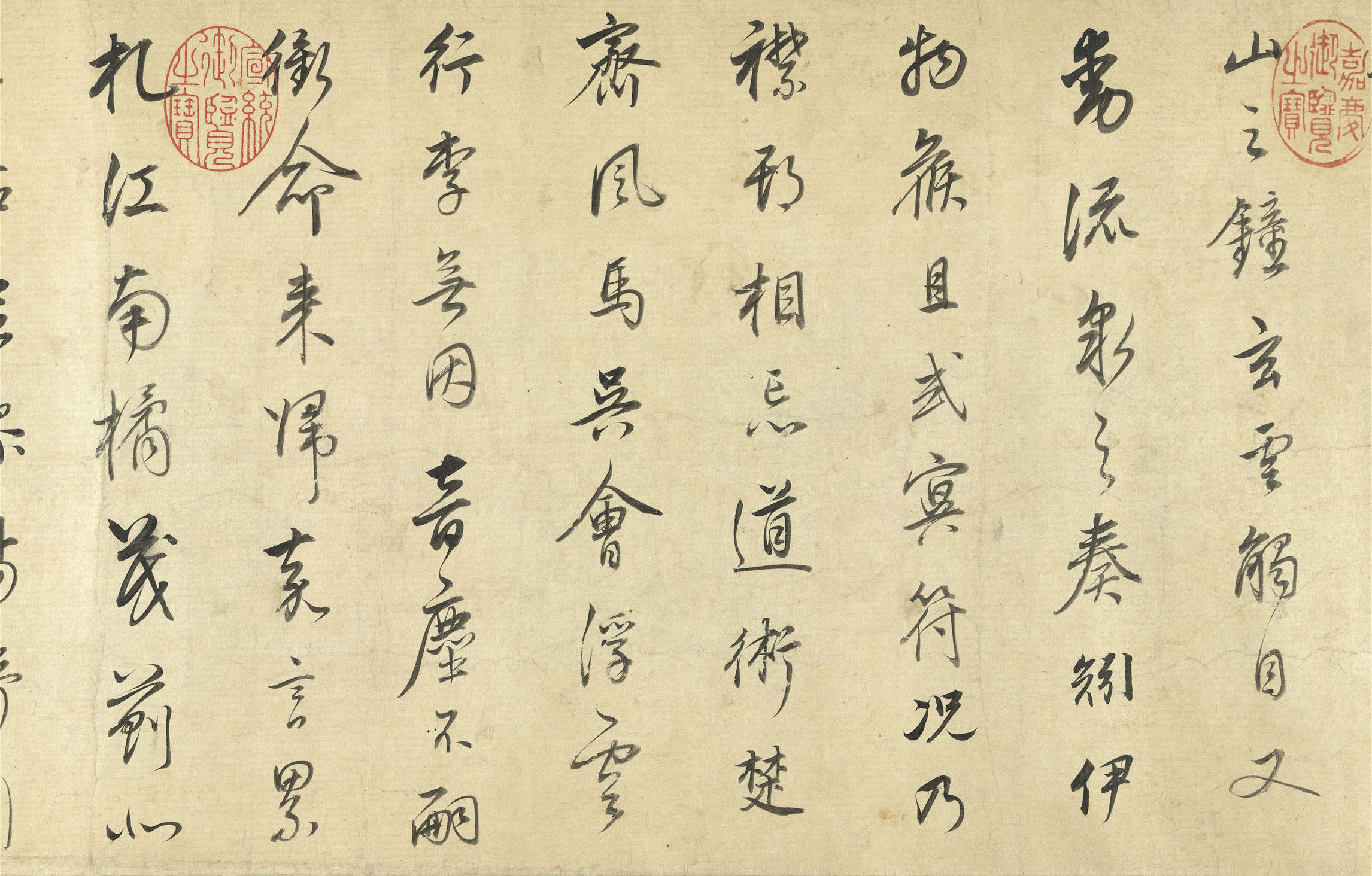

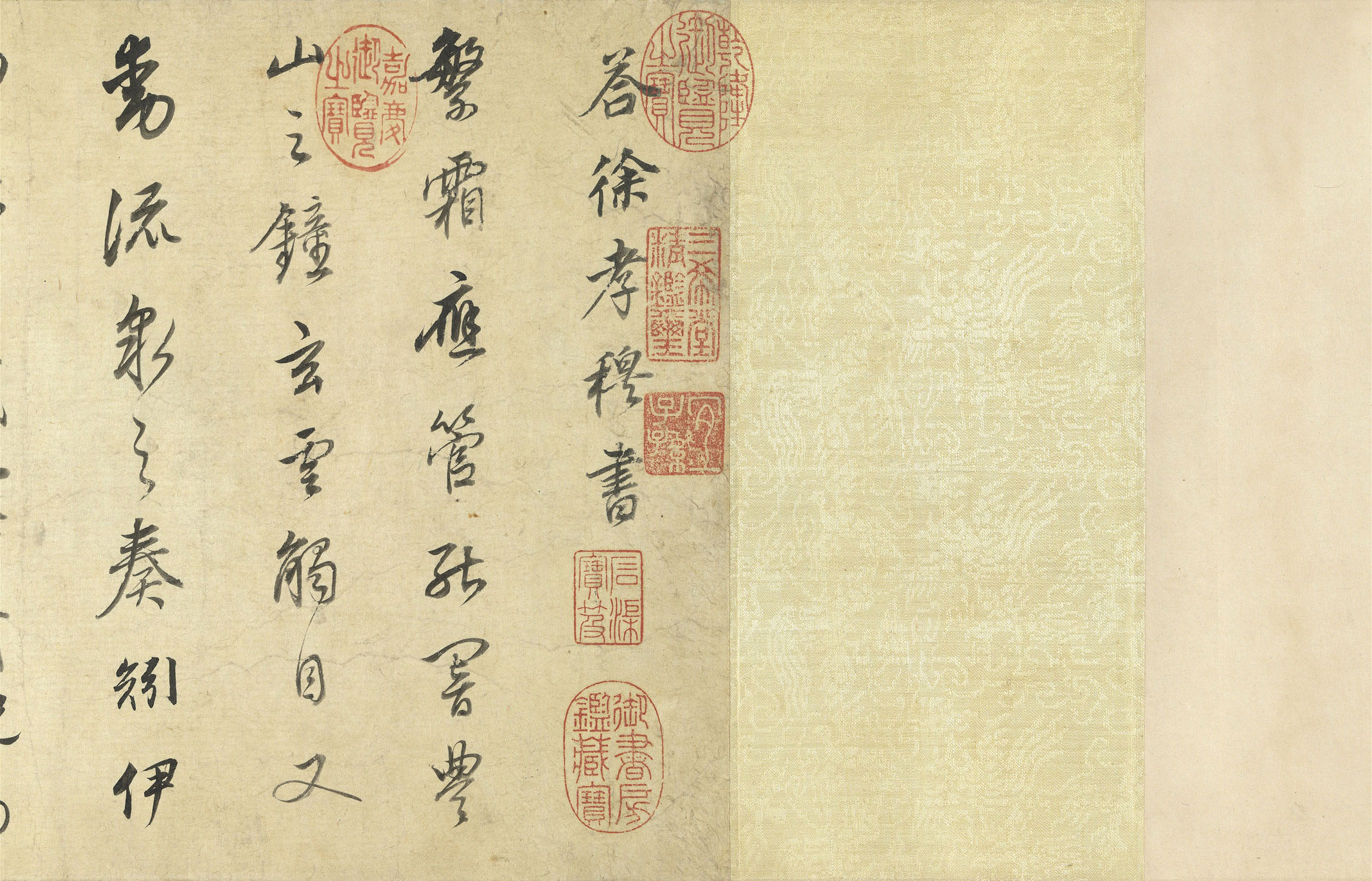

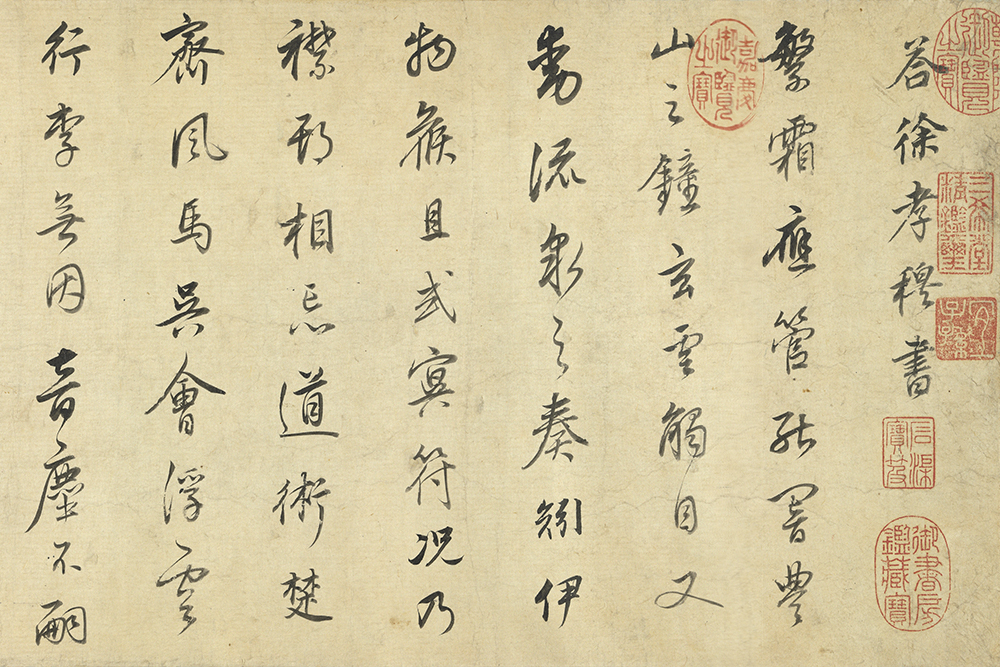

A Reply to Xu Xiaomu's Letter

- Dong Qichang, Ming dynasty

Dong Qichang (1555-1636), was a late-Ming dynasty official as well as an important calligrapher, painter, and collector of the arts.

This scroll comprises a transcription of a letter Li Chang (516-565) wrote to Xu Ling (style name Xiaomu, 507-583) in running and cursive scripts, written when Dong was sixty-seven years old. The ample, robust lines evoke the calligraphy of Yan Zhenqing (709-785), while the occasionally lean, even gaunt characters recall Huaisu (ca. latter half of the 8th century). The brush's tip is frequently revealed, and in places the brushstrokes seem to be cut off even though the writer's intent continues unbroken. There are sudden shifts between lifting and pressing as well as rounded and angular strokes, yielding a sense of freedom and ease reminiscent of Mi Fu (1052-1107). Richness abounds in the ink's tonal gradations, with numerous strings of characters that go from dark to light while creating a feeling of visual cadence. The generous spacing of the columns plays off against the allure of Dong's brushwork and use of ink, adding lively emptiness and a graceful aura.

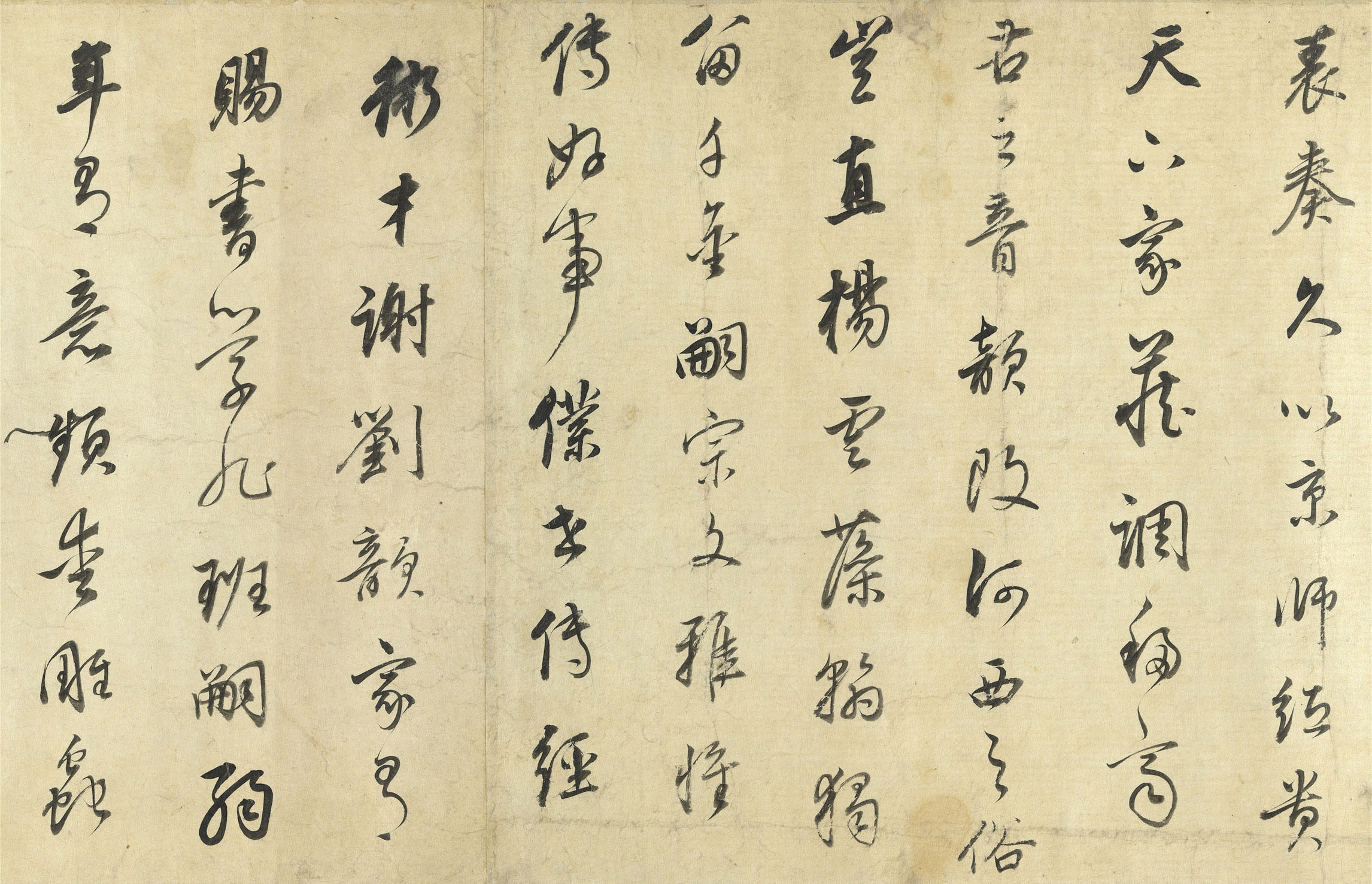

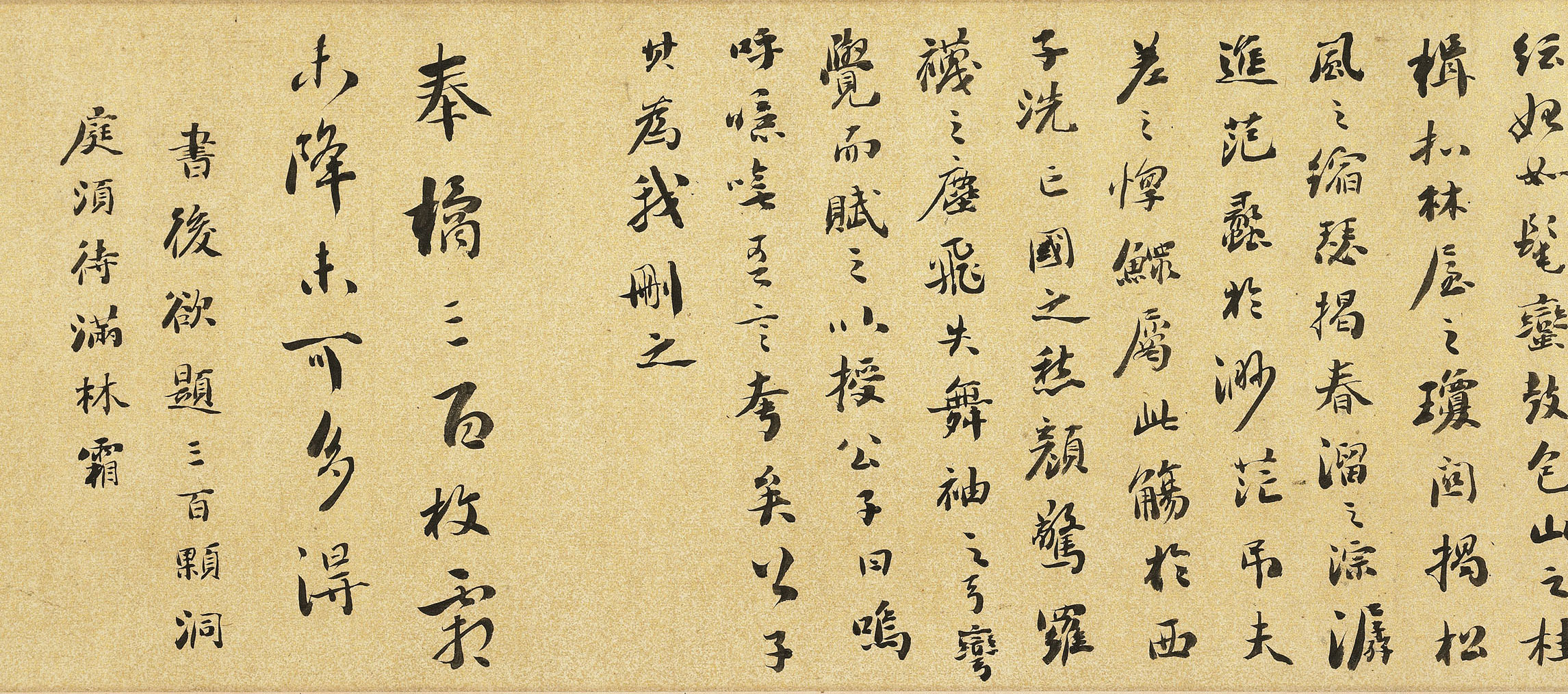

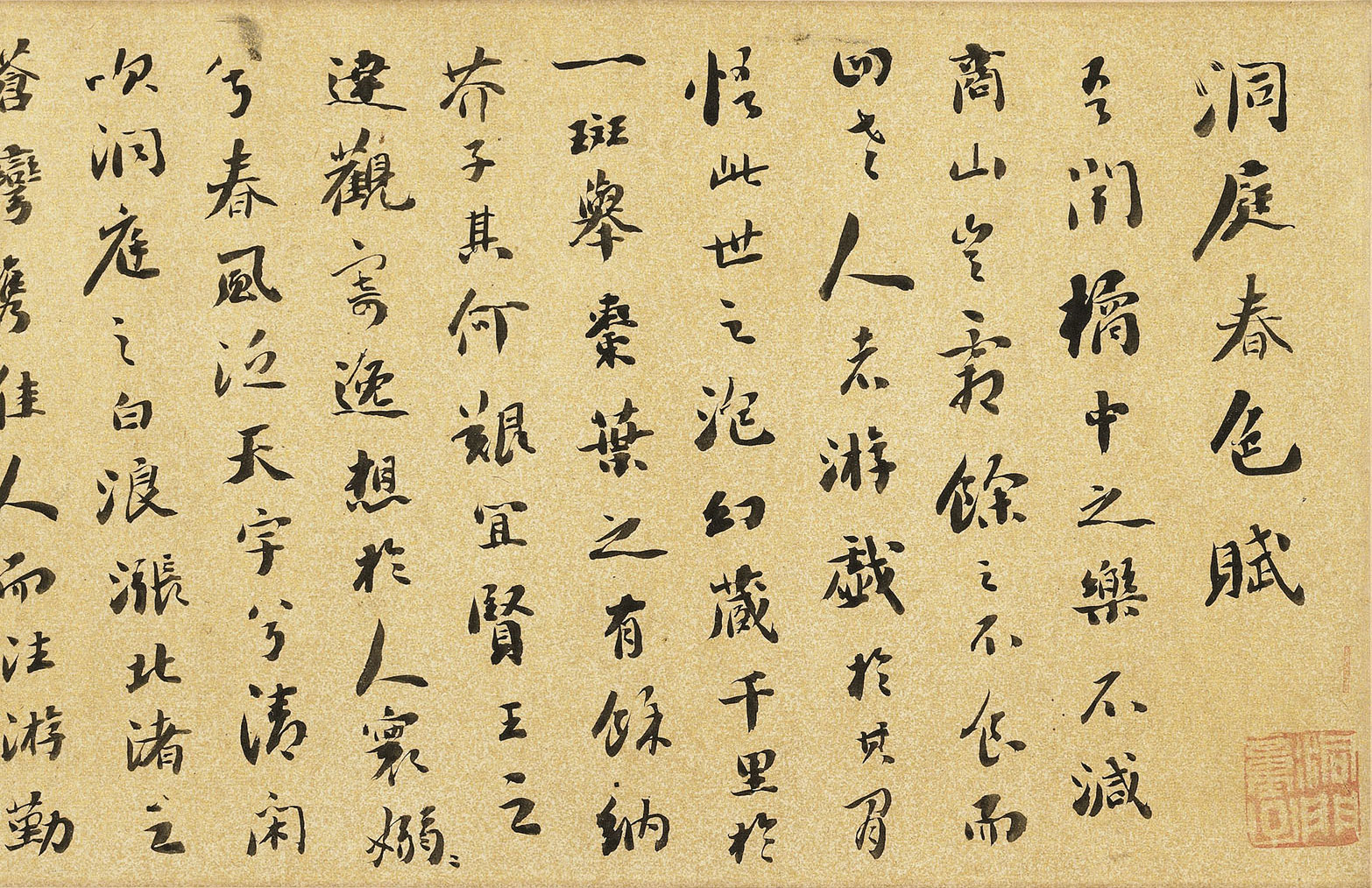

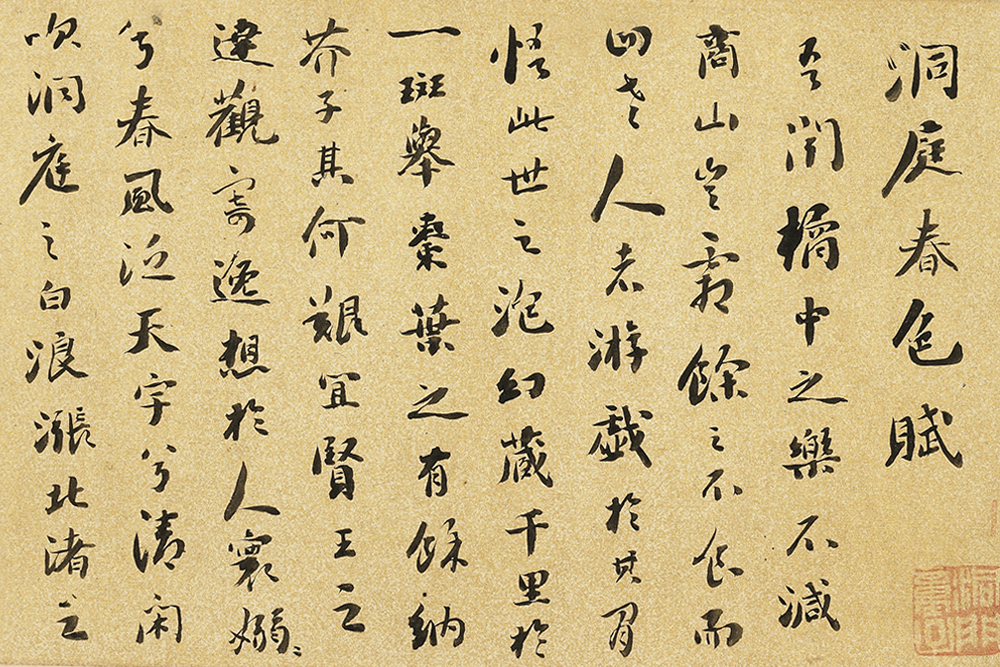

Calligraphy of "Rhapsody on Dongting Spring Colors Wine" and Other Works

- Liu Yong, Qing dynasty

Liu Yong (1720-1804), an official who attained the rank of grand secretary, was so skilled at calligraphy that he earned the moniker "Grand Councilor of Thick Ink."

This scroll was bestowed to the NPM by Mr. Tan Boyu and Mr. Tan Jifu. On it, Liu calligraphically transcribed Su Shi's (1037-1101) "Rhapsody on Dongting Spring Colors Wine," Wang Xizhi's "Fengju Modelbook," and a poem by Wei Yingwu (737-792). The seal mark reading "Child of the Grotto's Entrance" (Dongmen Tongzi) at the start of the scroll indicates that it Liu completed this work when he was eighty-five years of age. The entire piece was written by keeping the brush's tip concealed in the center of the lines, which strike balances between thickness and sluggishness, as well as agility and flightiness. This effect leaves the viewer with the sense of an accomplished hand writing at will, handling tricky aspects of calligraphy with such ease that the writing is simultaneously powerful and yet reserved. These features place this masterwork amid heirs to the influence of Yan Zhenqing (709-785).

Exhibit List

| Title | Artist | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Fengju Modelbook | Wang Xizhi | Jin dynasty |

| Li Ji Stele | Emperor Gaozong | Tang dynasty |

| Yanzi Modelbook | Emperor Taizong | Song dynasty |

| Chusong Modelbook | Su Shi | Song dynasty |

| Modelbook of the Poem "The River Tiao" | Mi Fu | Song dynasty |

| Roumao Modelbook | Zhao Mengfu | Yuan dynasty |

| Poems Affixed to Paintings | Ke Jiusi, et al. | Yuan dynasty |

| Ode to Mandarin Trees Modelbook | Shen Zao | Ming dynasty |

| "A Gift of a Pipa" and Other Poems | Wu Kuan | Ming dynasty |

| "Jade Chopsticks Seal Script" from "An Album of Various Forms of Seal Script" | Lu Yiyue | Ming dynasty |

| Elegant Comfort Amid Forests and Springs with Seven-character Poetry | Wen Zhengming | Ming dynasty |

| "A Mournful Night in the Mountains" & "Playing a Long Flute" | Wang Chong | Ming dynasty |

| A Reply to Xu Xiaomu's Letter | Dong Qichang | Ming dynasty |

| Myriad Sounds are Quieted Rhapsody | Huang Daozhou | Ming dynasty |

| After the "Fengju" and Other Modelbooks | Wang Shu | Qing dynasty |

| Study of Mi Fu's Modelbook of the Poem "The River Tiao" | Zhang Zhao | Qing dynasty |

| Imperially Commissioned Calligraphy of a Poem on Rain | Wang Youdun | Qing dynasty |

| Climbing the Northern Xietiao Tower along the Xuan City Wall in Autumn | Zheng Xie | Qing dynasty |

| Study of Mi Fu's Modelbook of the Poem "The River Tiao" | Gaozong | Qing dynasty |

| Calligraphy of "Rhapsody on Dongting Spring Colors Wine" and Other Works | Liu Yong | Qing dynasty |

| An Inscription of Huang Tingjian of the Song dynasty's Colophon for Wang Youjun's Calligraphy | He Shaoji | Qing dynasty |

| "South of the Yangtze River" in Running Script | Xu Shaosong | Republican era |