Introduction

To meet the need for recording information and ideas, unique forms of calligraphy (the art of writing) have been part of the Chinese cultural tradition through the ages. Naturally finding applications in daily life, calligraphy still serves as a continuous link between the past and the present. The development of calligraphy, long a subject of interest in Chinese culture, is the theme of this exhibit, which presents to the public selections from the National Palace Museum collection arranged in chronological order for a general overview.

The dynasties of the Qin (221-206 BCE) and Han (206 BCE-220 CE) represent a crucial era in the history of Chinese calligraphy. On the one hand, diverse forms of brushed and engraved "ancient writing" and "large seal" scripts were unified into a standard type known as "small seal." On the other hand, the process of abbreviating and adapting seal script to form a new one known as "clerical" (emerging previously in the Eastern Zhou dynasty) was finalized, thereby creating a universal script in the Han dynasty. In the trend towards abbreviation and brevity in writing, clerical script continued to evolve and eventually led to the formation of "cursive," "running," and "standard" script. Since changes in writing did not take place overnight, several transitional styles and mixed scripts appeared in the chaotic post-Han period, but these transformations eventually led to established forms for brush strokes and characters.

The dynasties of the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) represent another important period in Chinese calligraphy. Unification of the country brought calligraphic styles of the north and south together as brushwork methods became increasingly complete. Starting from this time, standard script would become the universal form through the ages. In the Song dynasty (960-1279), the tradition of engraving modelbook copies became a popular way to preserve the works of ancient masters. Song scholar-artists, however, were not satisfied with just following tradition, for they considered calligraphy also as a means of creative and personal expression.

Revivalist calligraphers of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), in turning to and advocating revivalism, further developed the classical traditions of the Jin and Tang dynasties. At the same time, notions of artistic freedom and liberation from rules in calligraphy also gained momentum, becoming a leading trend in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Among the diverse manners of this period, the elegant freedom of semi-cursive script contrasts dramatically with more conservative manners. Thus, calligraphers with their own styles formed individual paths that were not overshadowed by the mainstream of the time.

Starting in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), scholars increasingly turned to inspiration from the rich resource of ancient works inscribed with seal and clerical script. Influenced by an atmosphere of closely studying these antiquities, Qing scholars became familiar with steles and helped create a trend in calligraphy that complemented the Modelbook school. Thus, the Stele school formed yet another link between past and present in its approach to tradition, in which seal and clerical script became sources of innovation in Chinese calligraphy.

Selections

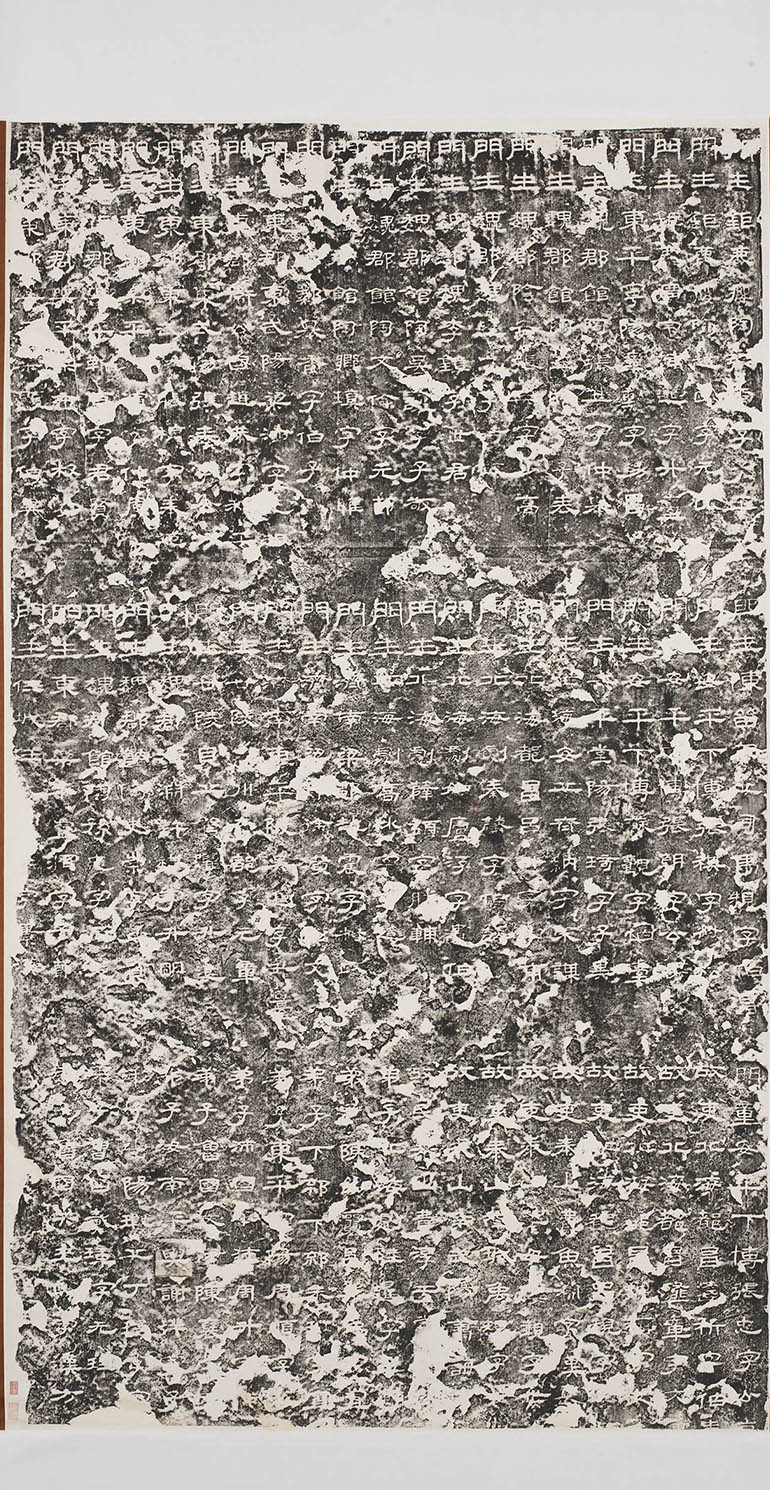

Stele Commemorating Kong Zhou, Commandant in Chief of the Customs Barrier at Mount Tai

- Han dynasty

This stele marked the tomb of Kong Rong's father, Kong Zhou (103-163). Kong Zhou's biography, included in The Book of the Later Han, records how he did his utmost to quell disorder while working as Commandant in Chief of the Customs Barrier at Taishan. He later relinquished his post due to illness, and in the sixth year of the Yanxi reign period under Emperor Huan of the Eastern Han dynasty (163) he passed away. The following year, Kong Zhou's disciples sponsored this stele to commemorate their late teacher's virtuous achievements. This stele is currently housed at the Confucian Temple in Qufu, Shandong province. Its calligrapher used the rounded brushwork of zhuanshu (stele script) to render lishu (official script). The characters are possessed of lithe structures whose smoothly level horizontal and diagonal strokes make the writing seem almost to sway. While the characters are all tightly structured around their center points, they expand bilaterally along their horizontal axes, giving them an especially broad appearance.

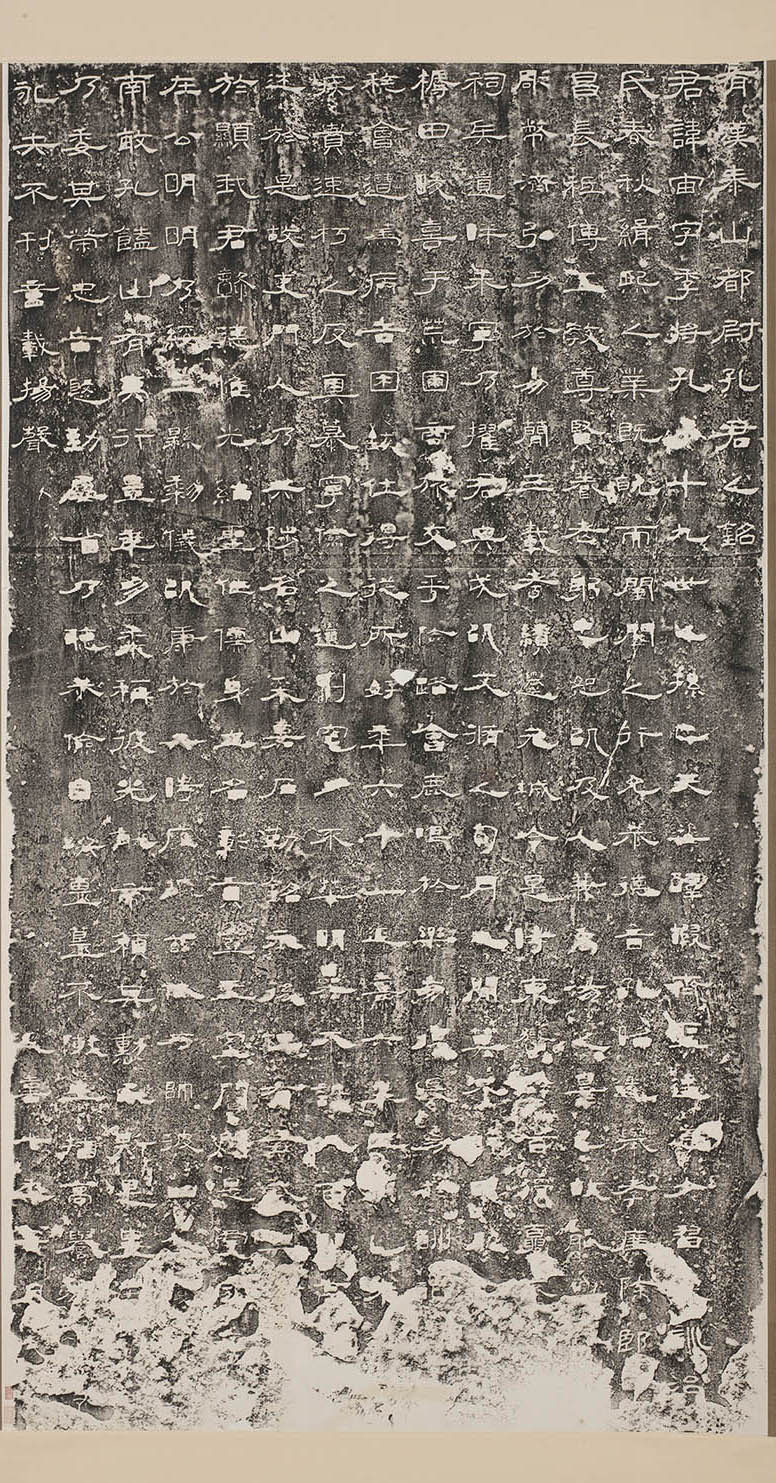

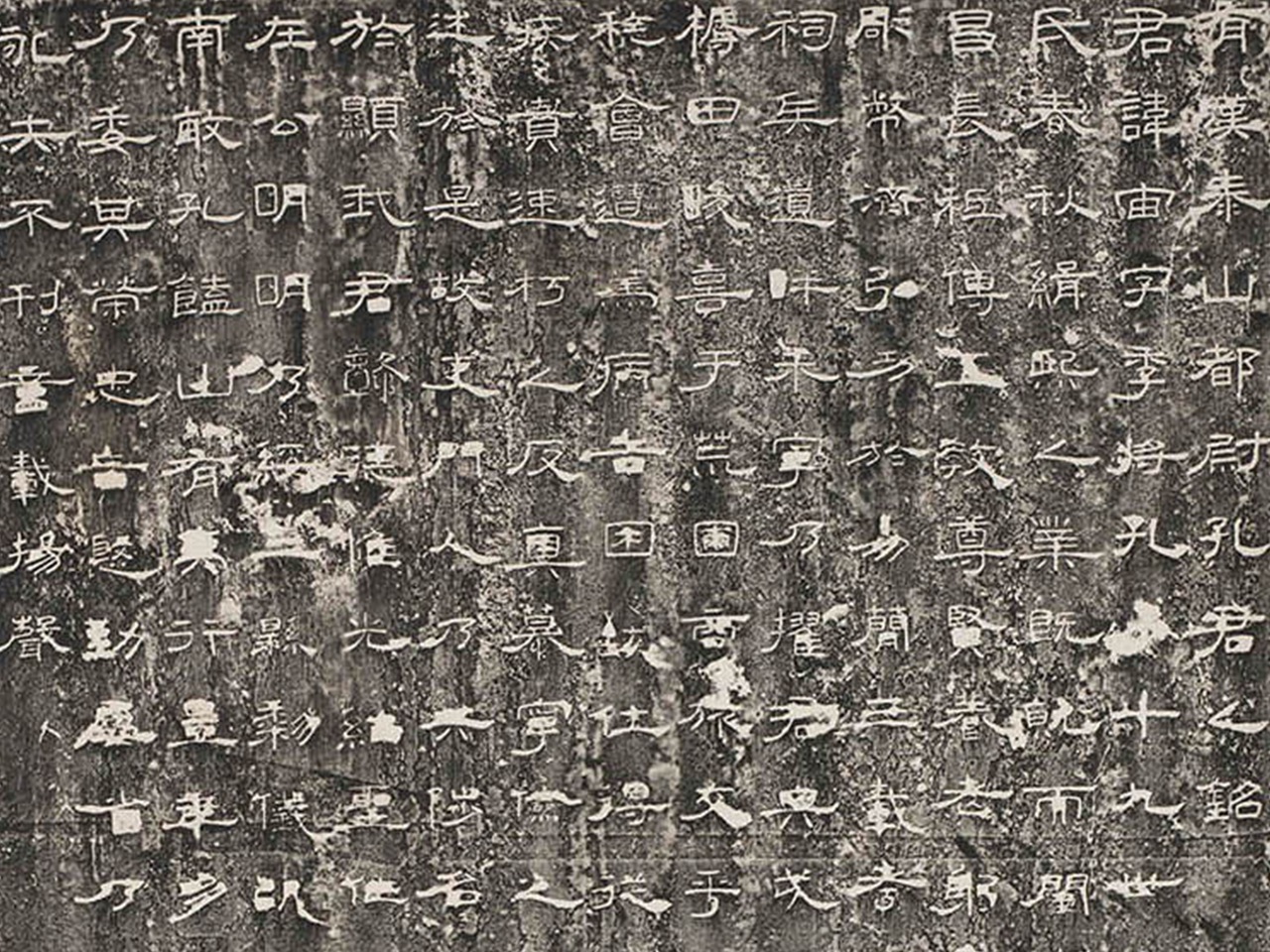

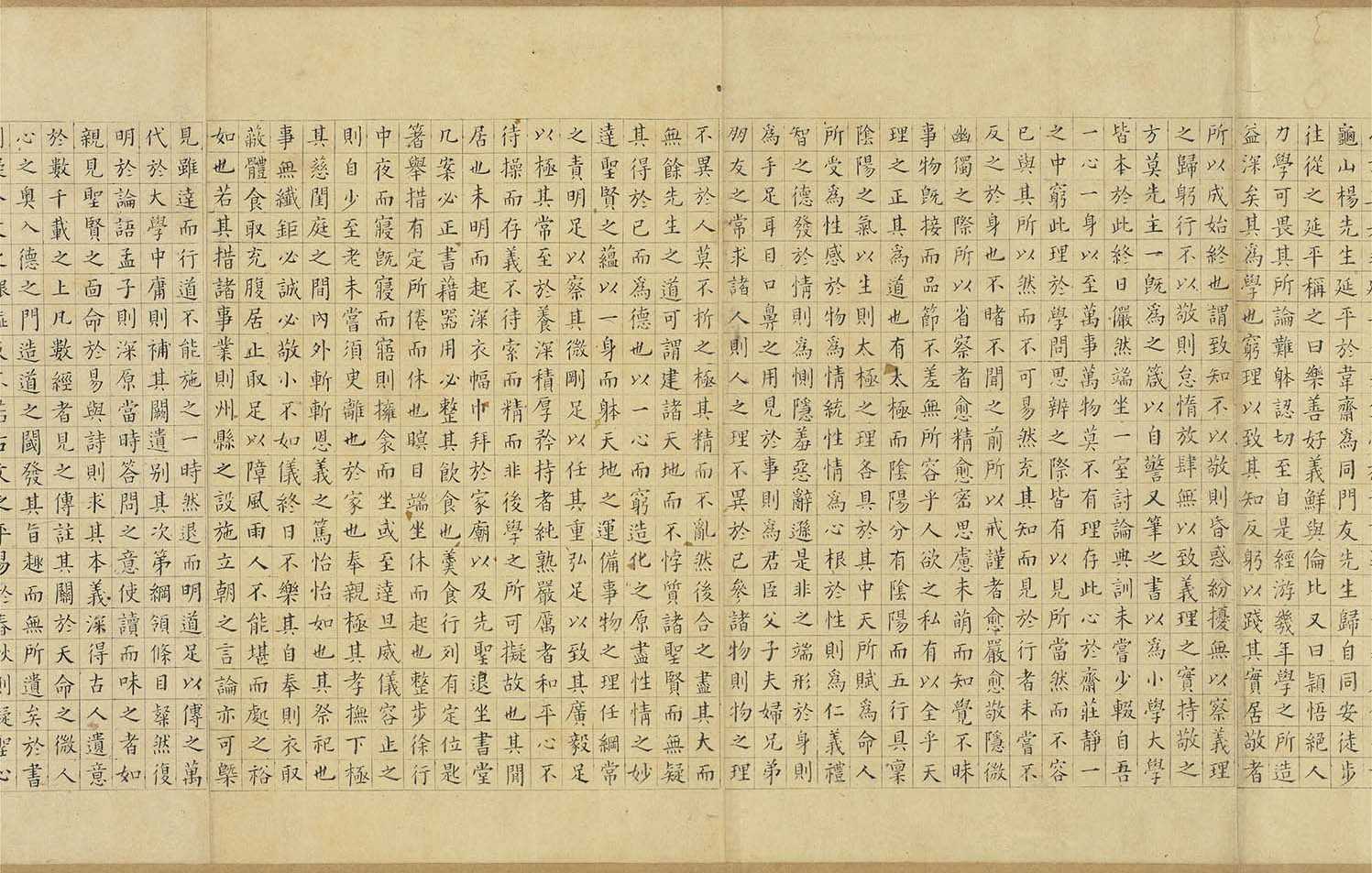

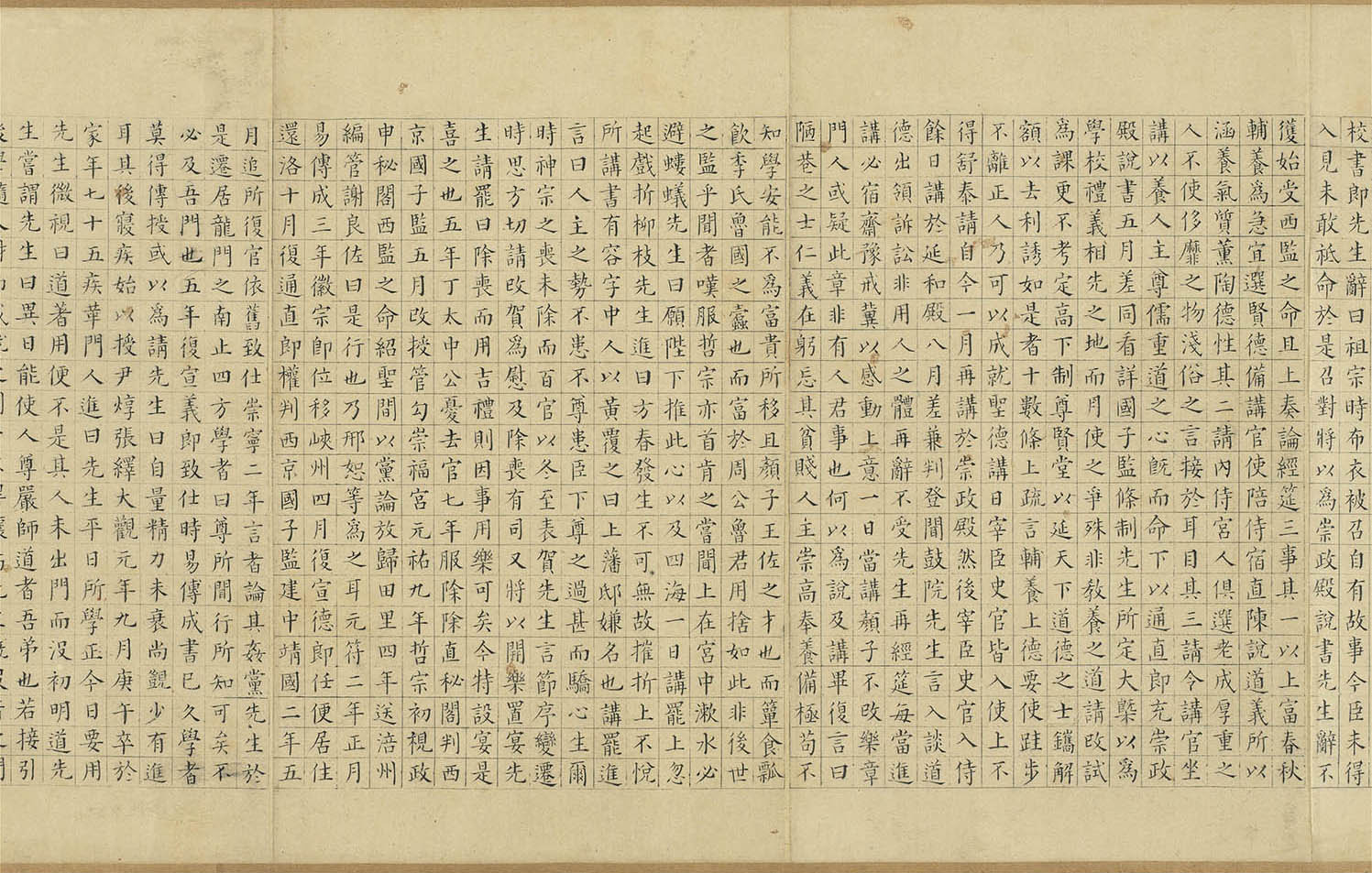

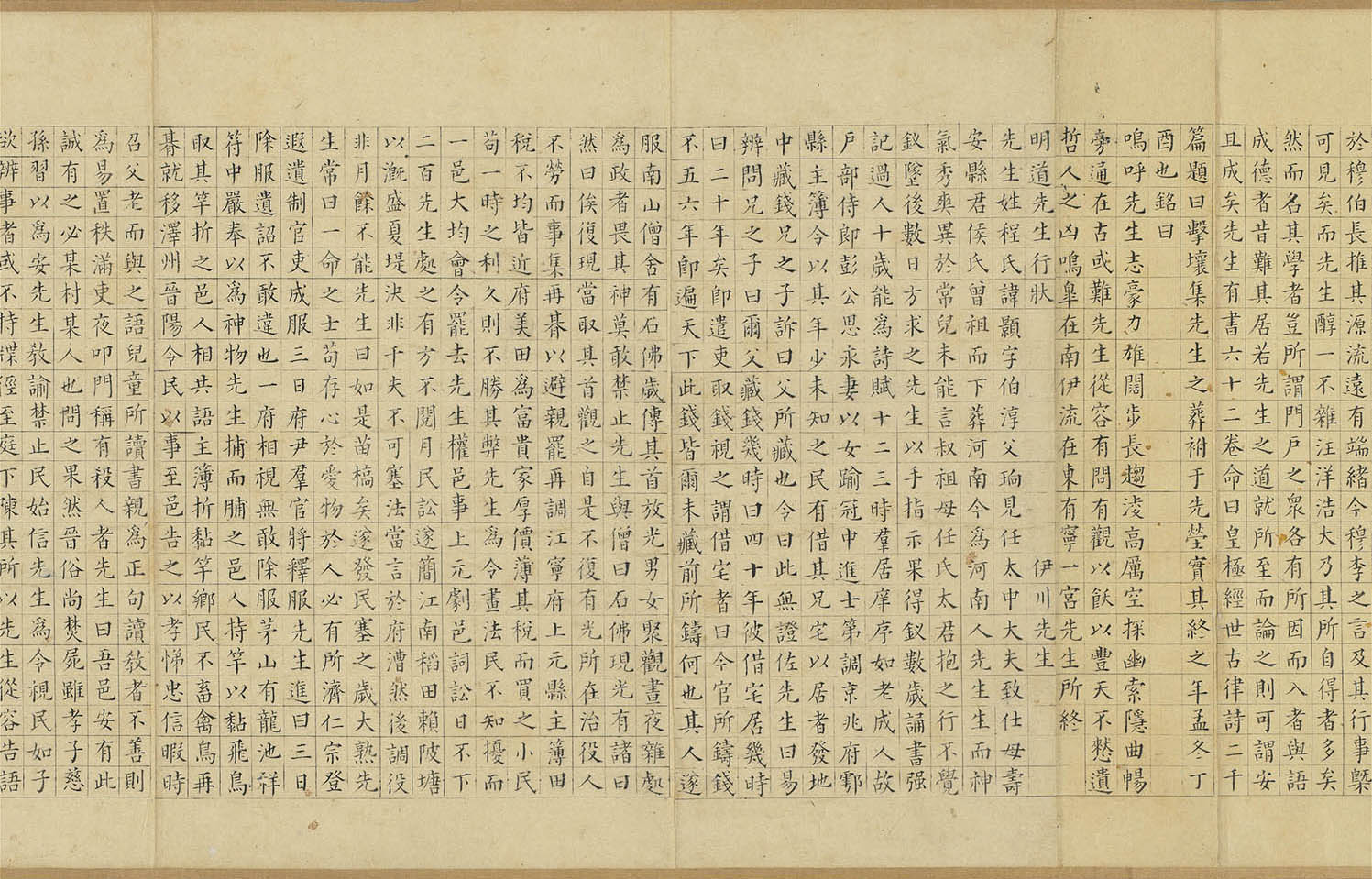

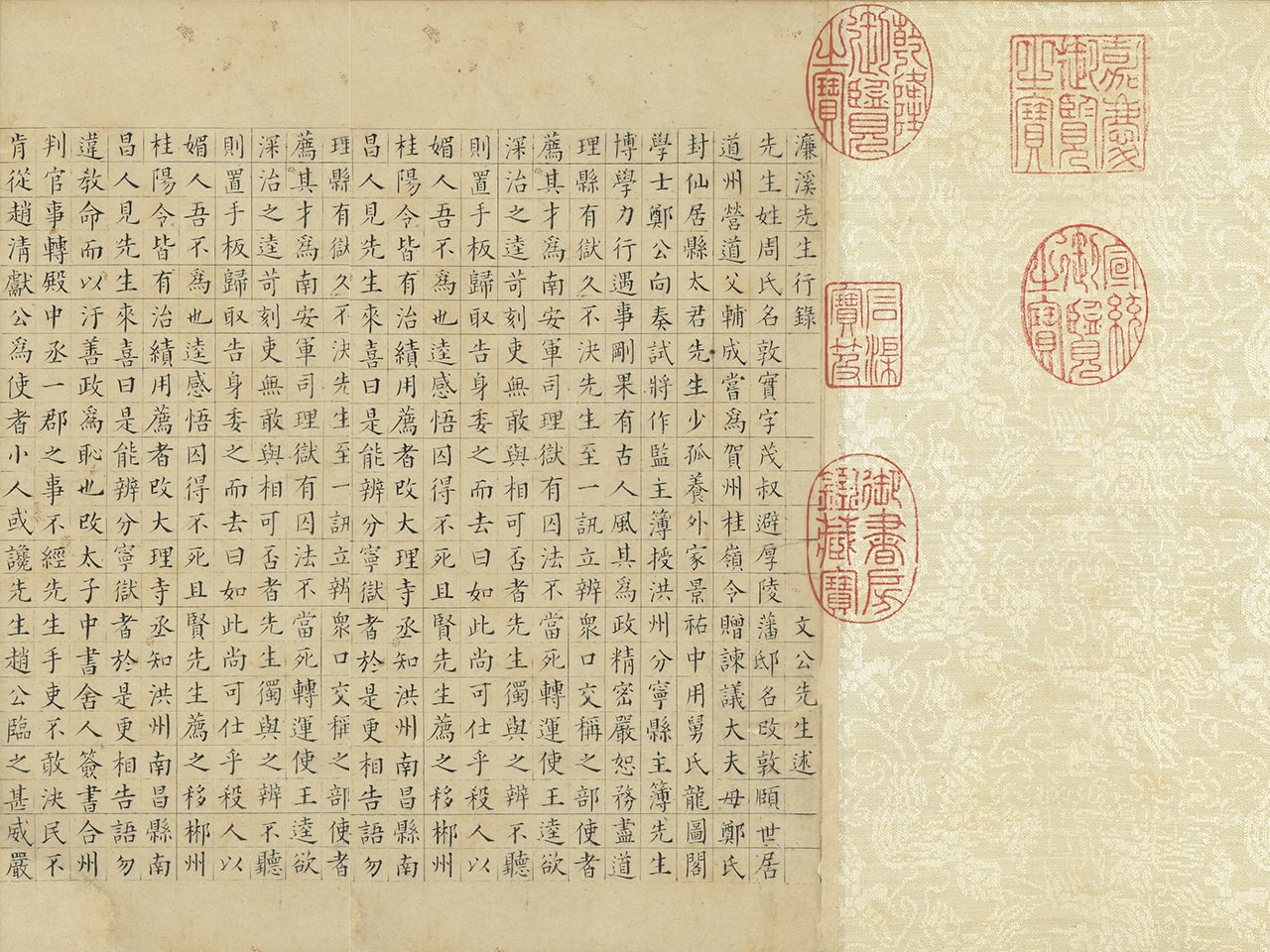

Biographies for the Six Sages of Song Confucianism

- Zhu Yunming (1460-1526), Ming dynasty

Zhu Yunming (1460-1526) encountered wide variety of rubbings from calligraphic models stemming from Jin and Tang dynasty luminaries during his youth. His works of kaishu (regular script), in addition to showing the stylistic influences of Zhong You, Wang Xizhi, and Wang Xianzhi, also clearly show traces of inspiration from various Tang dynasty masters.

This work of xiaokaishu (compact regular script) is heavily infused with the flavors of Tang dynasty kaishu. The characters were given exacting foursquare structures. Zhu moved his brush with force, using an unmuddied vigor that simultaneously evokes the wiry strength infusing Ouyang Xun's (557-641) svelte characters, as well as the delicate luster of Yu Shinan's (558-638) calligraphy. His hooked and right-falling strokes recall the unique characteristics of Yan Zhenqing's (709-785) and Liu Gongquan's (778-865) writing, revealing the depth and breadth of Zhu's studies of the old masters.

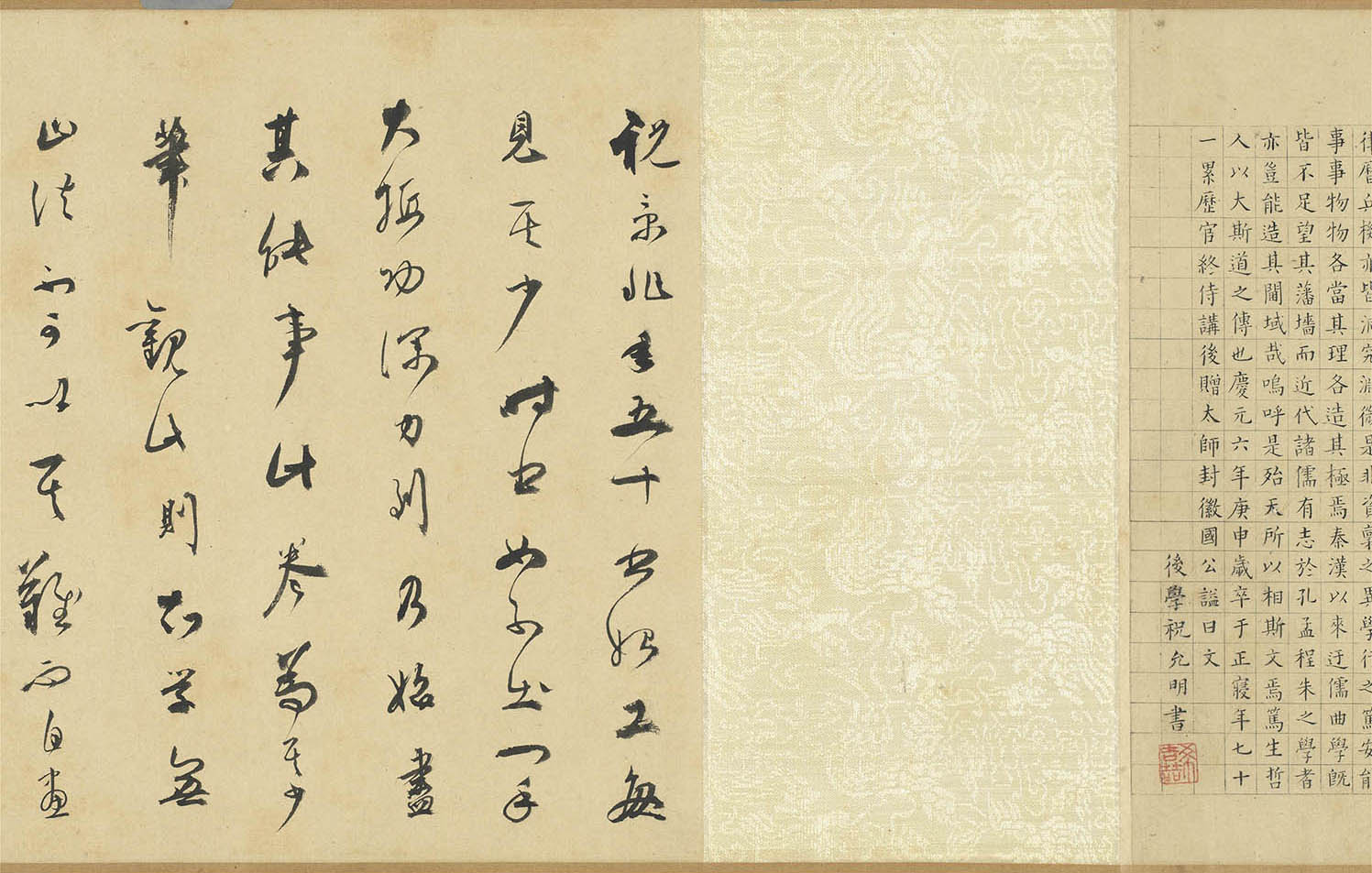

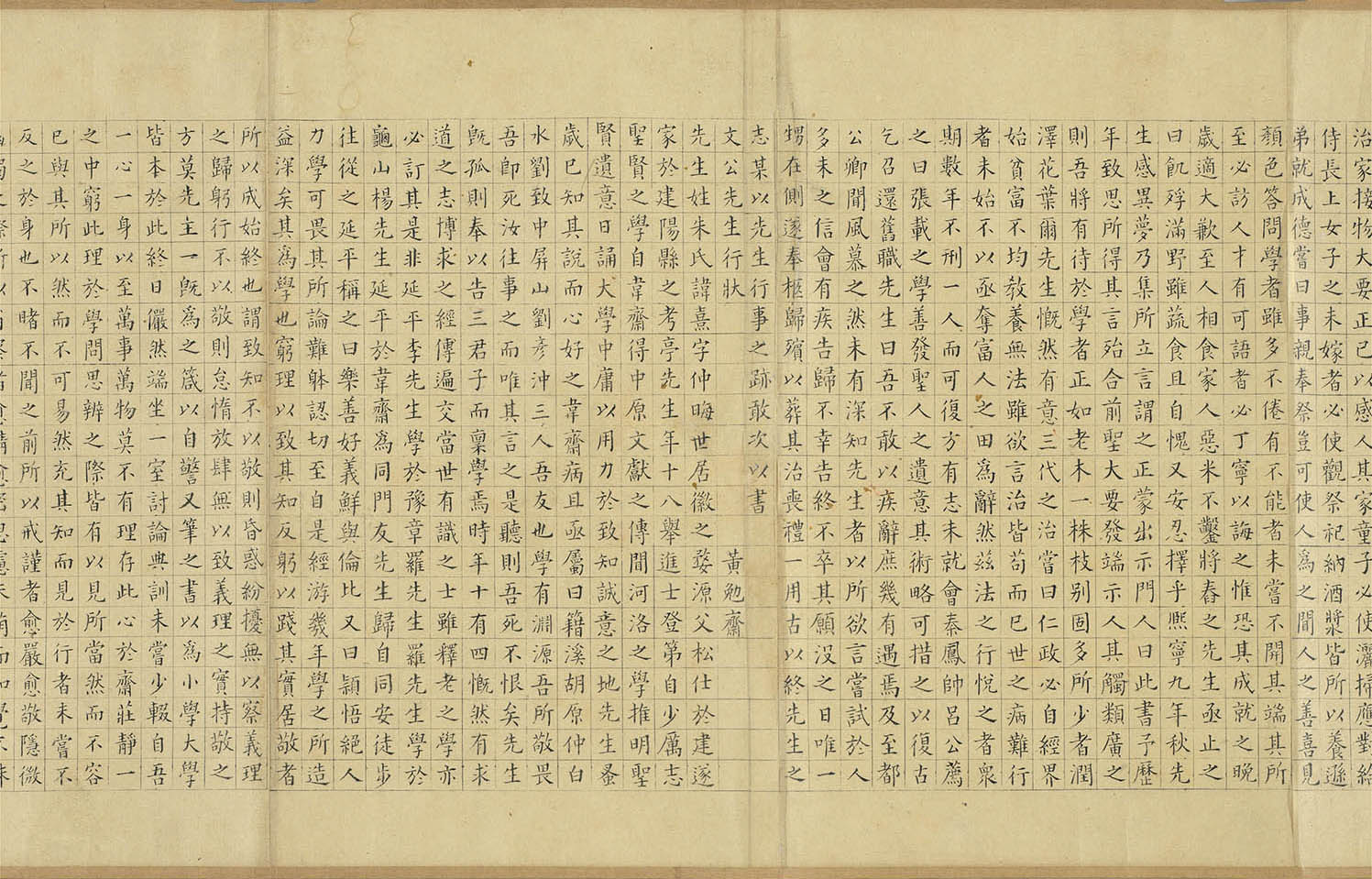

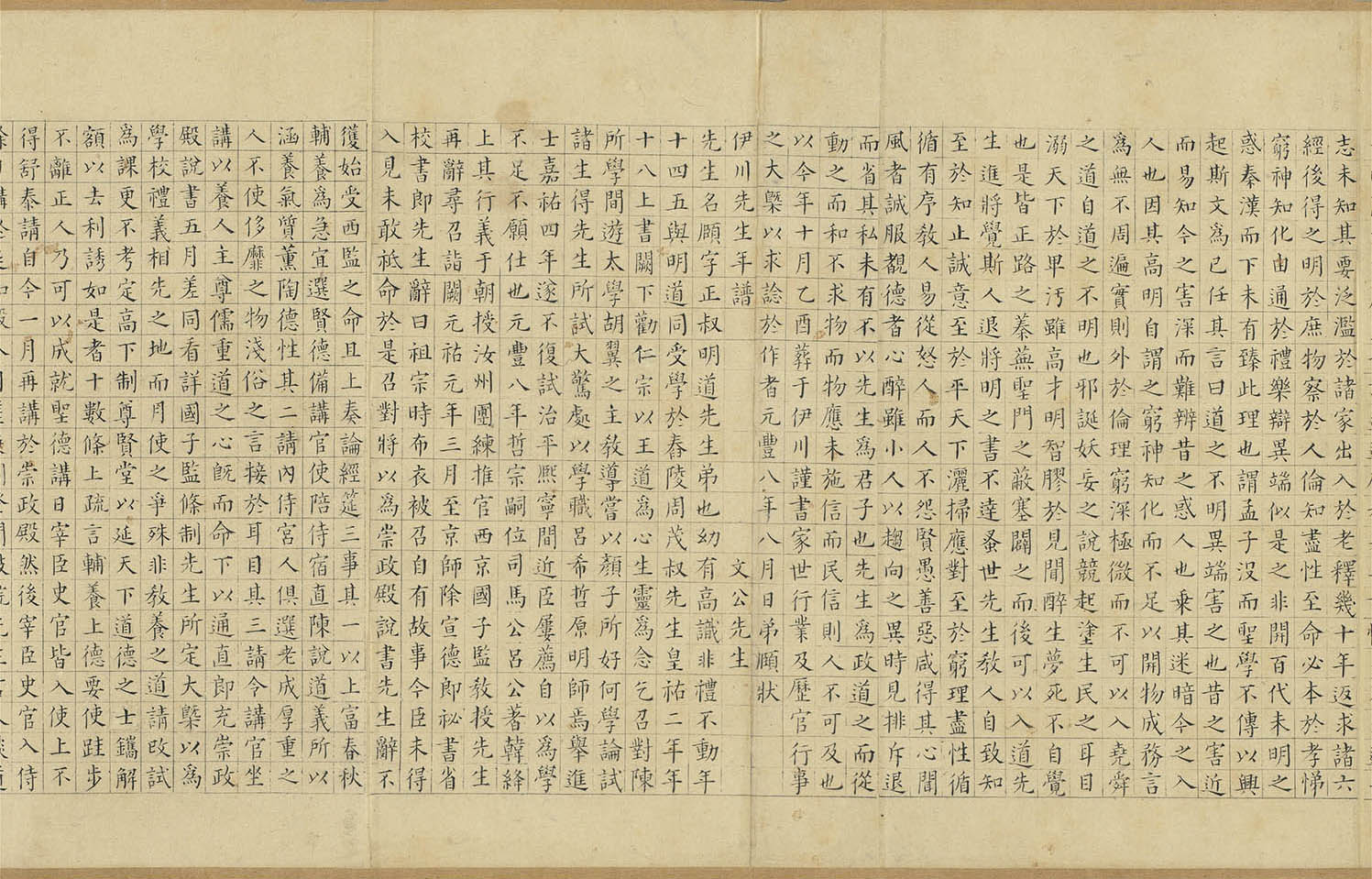

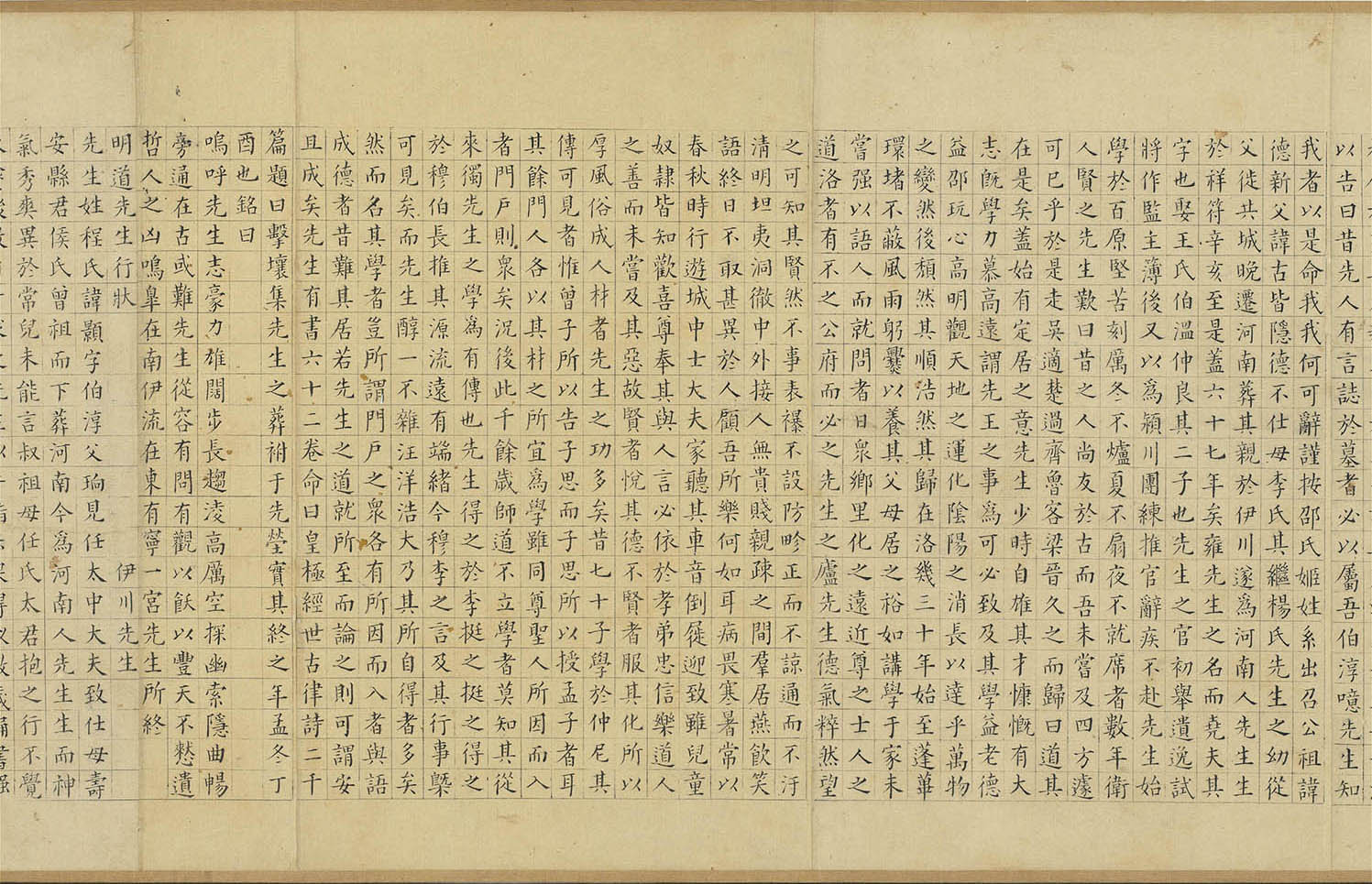

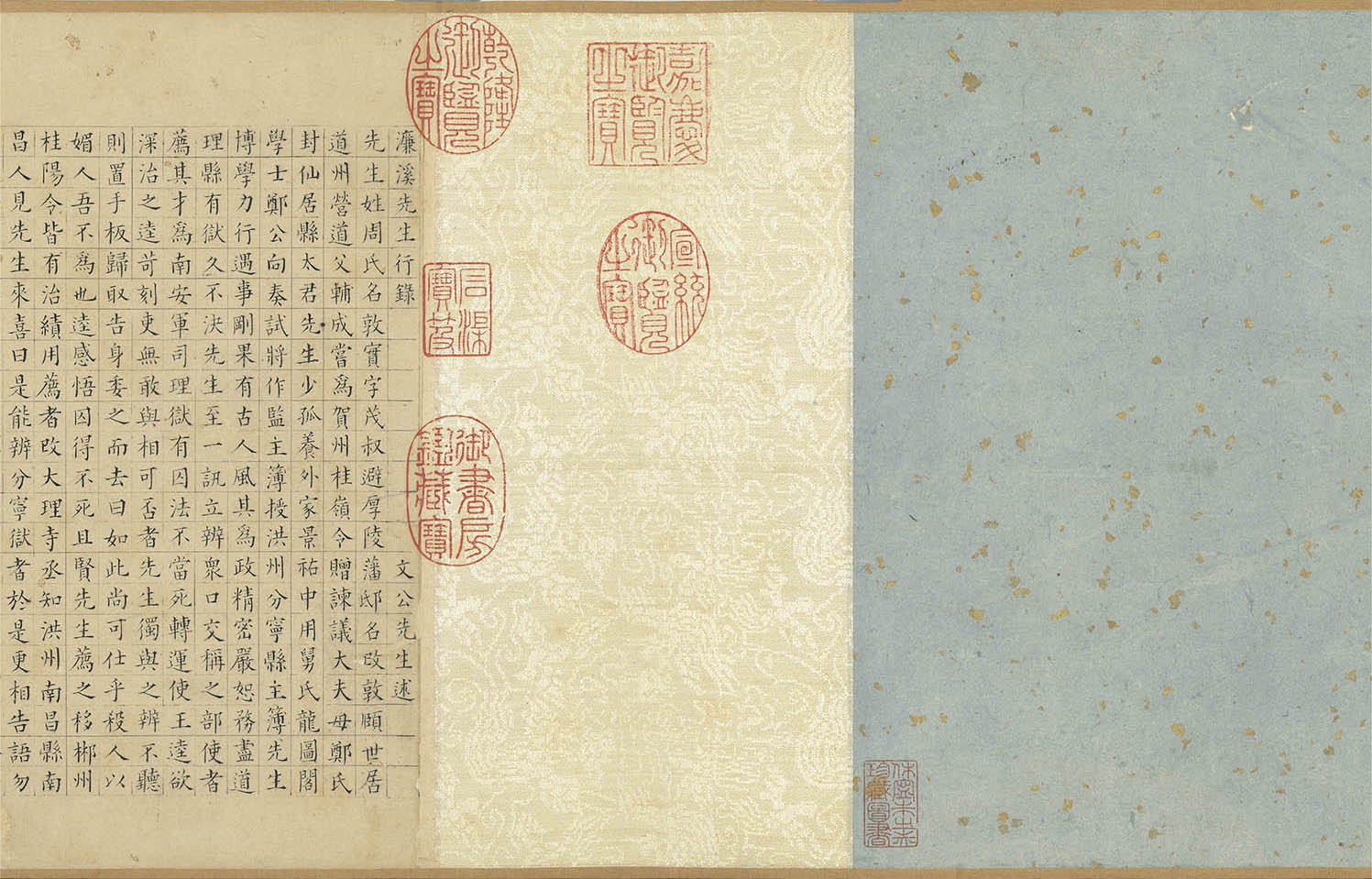

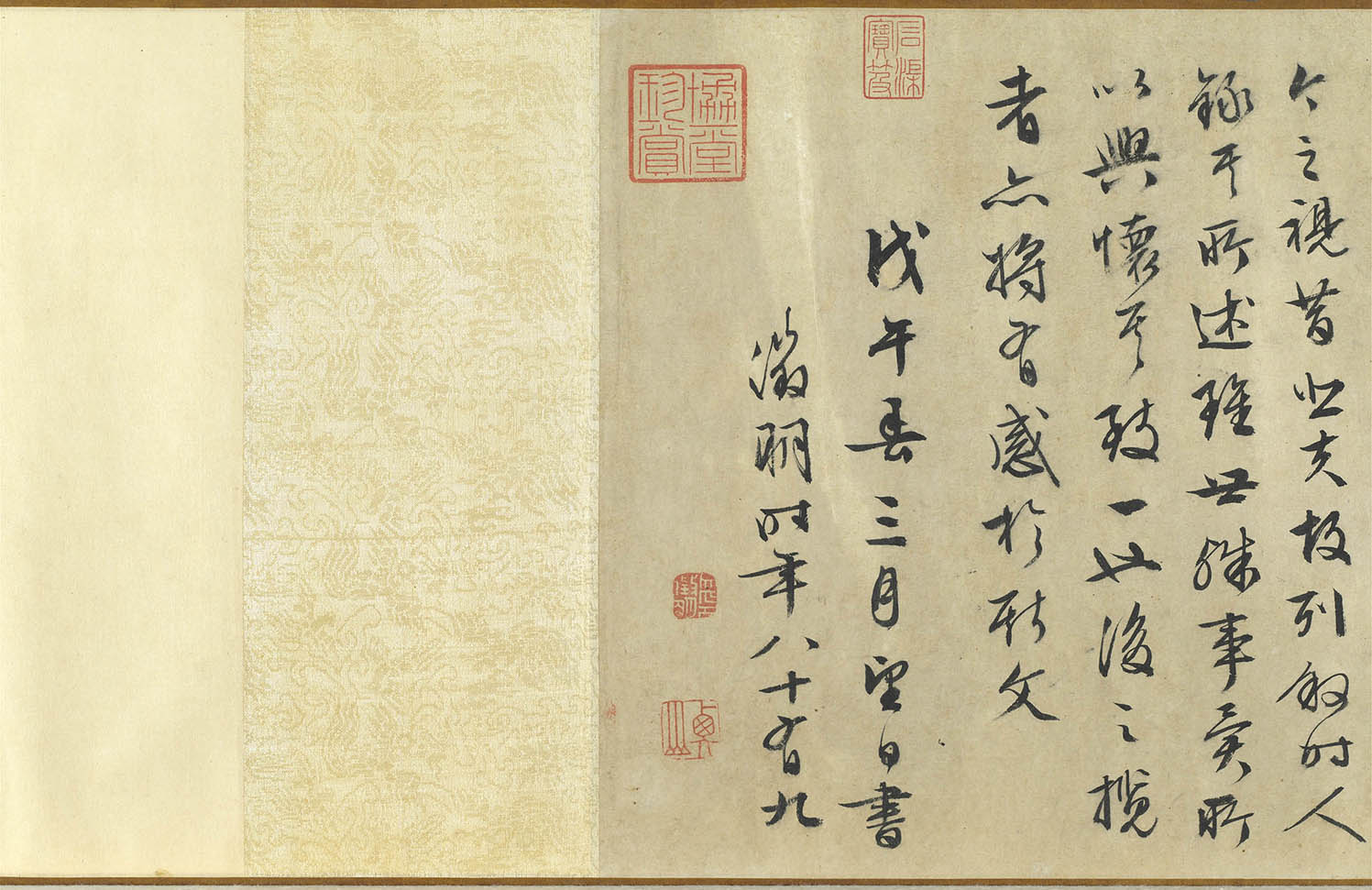

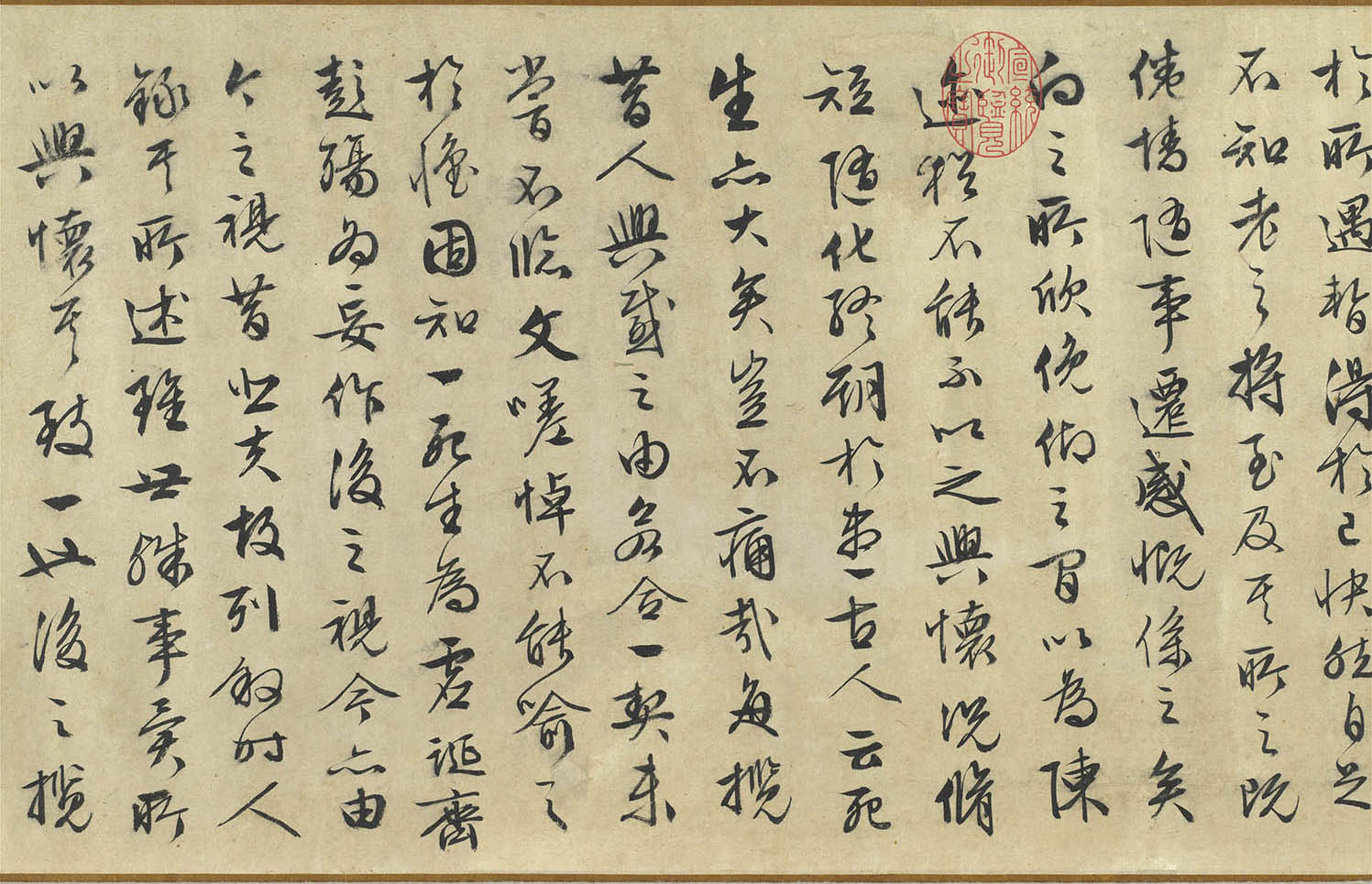

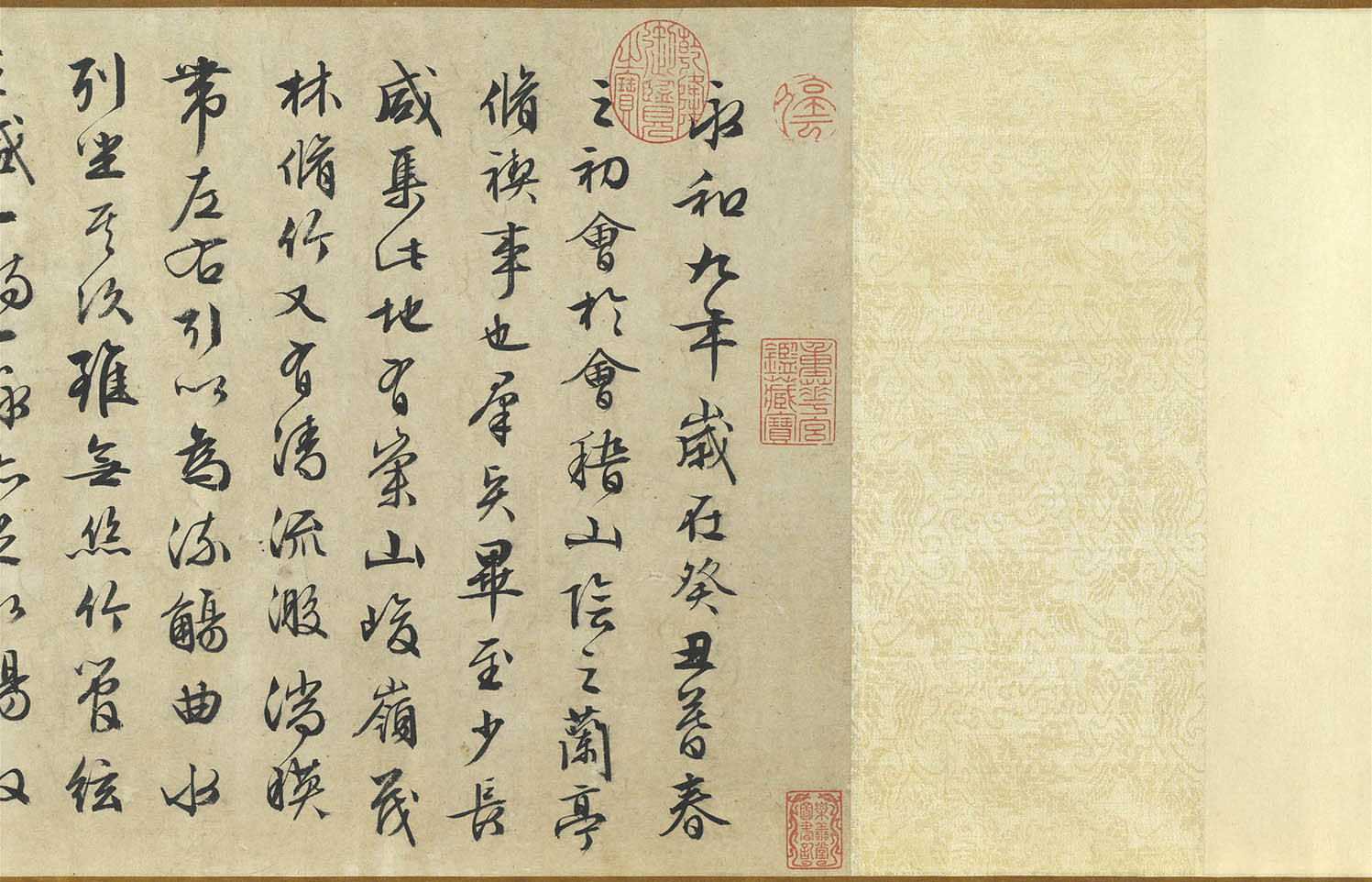

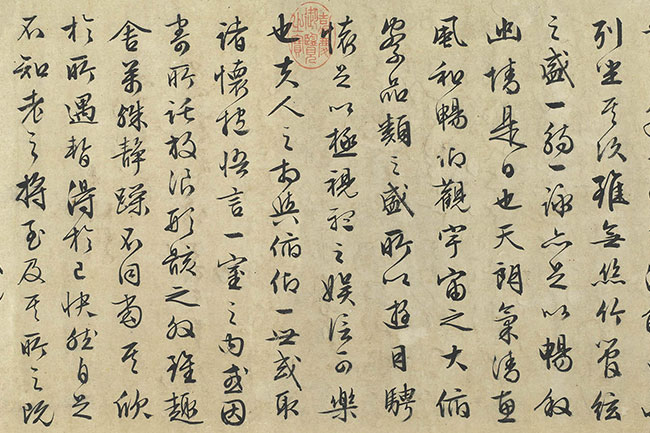

Preface to the Orchid Pavilion

- Wen Zhengming (1470-1559), Ming dynasty

Wen Zhengming (1470-1559) was a native of Changzhou in Jiangsu province. His given name was Bi, and he had the sobriquets He Who Stops the Clouds (Tingyunsheng) and the Recluse of Mount Heng (Hengshan Jushi), but he typically went by his style name, Zhengming. In addition to being an accomplished poet, prosaist, calligrapher, and painter, Wen was also an erudite connoisseur of the arts.

Wen Zhengming was fond of making copies of the "Preface to the Orchid Pavilion." In his inscription on the tail end of this scroll, he noted that he was eighty-nine years of age at the time of writing. Wen's brushwork, the structures of the characters, and the overall composition markedly differ from the received version of the "Preface to the Orchard Pavilion" in Wang Xizhi's (303-361) hand, indicating that Wen was making a study of the spirit of Wang's writing, rather than its technical particulars. Here the brushwork is understated and reserved, allowing for finely-structured characters. The many places where brush strokes flow one into the other give the scroll an outstanding sense of natural movement.

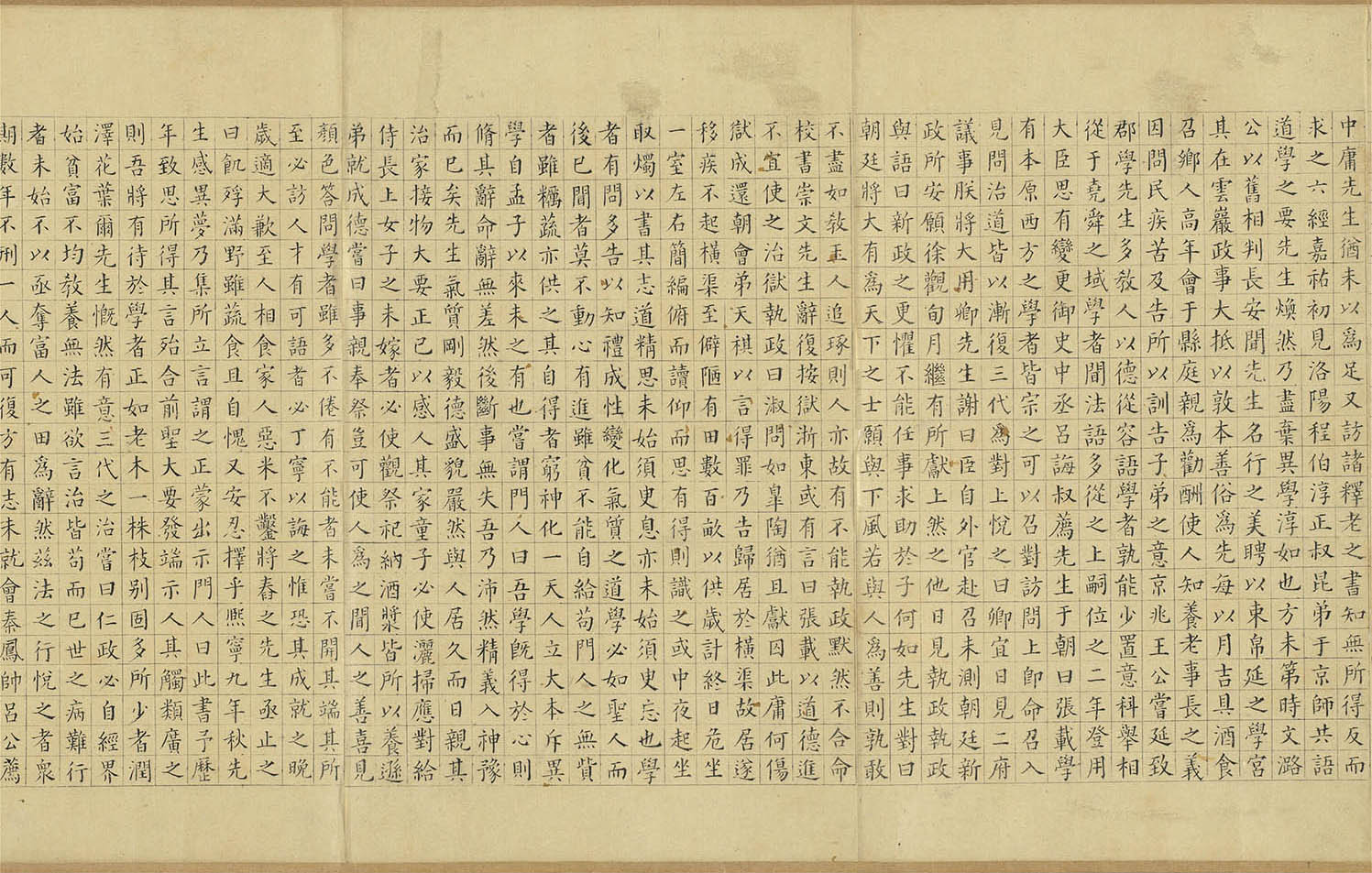

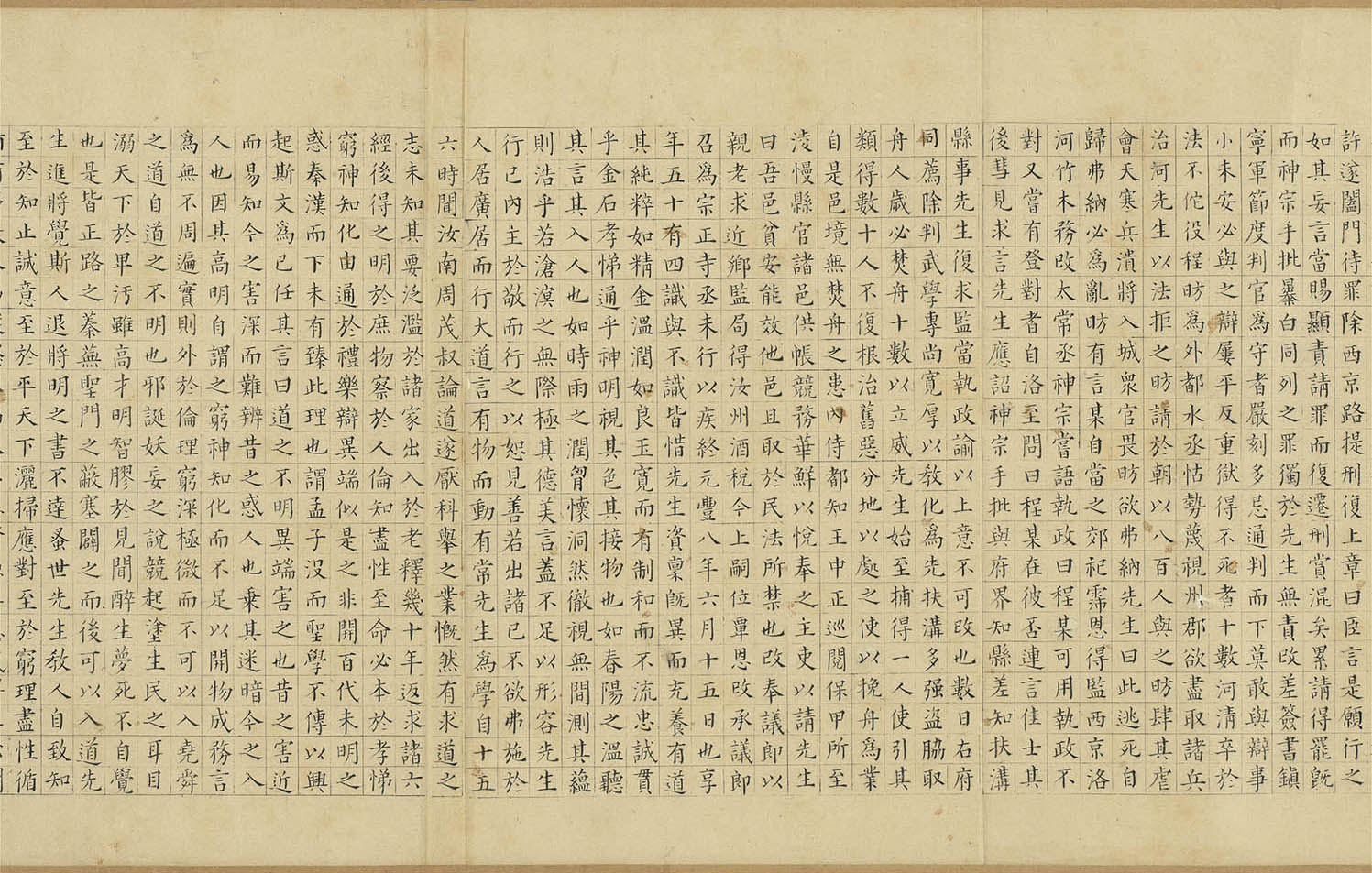

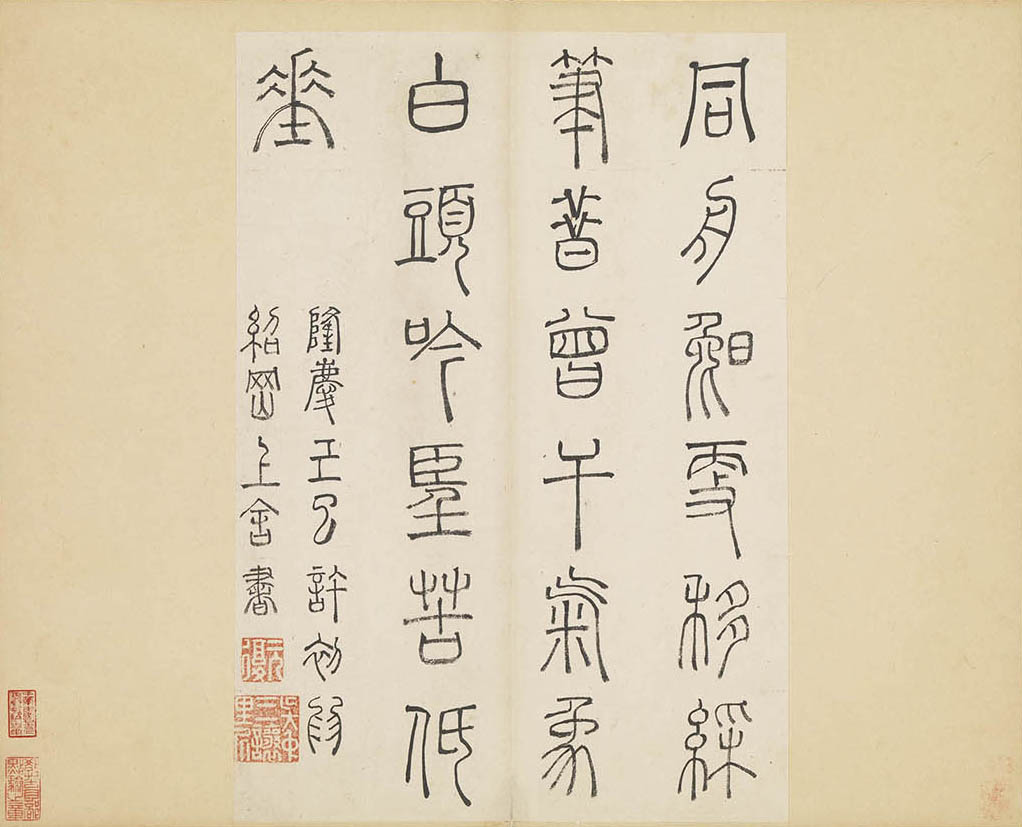

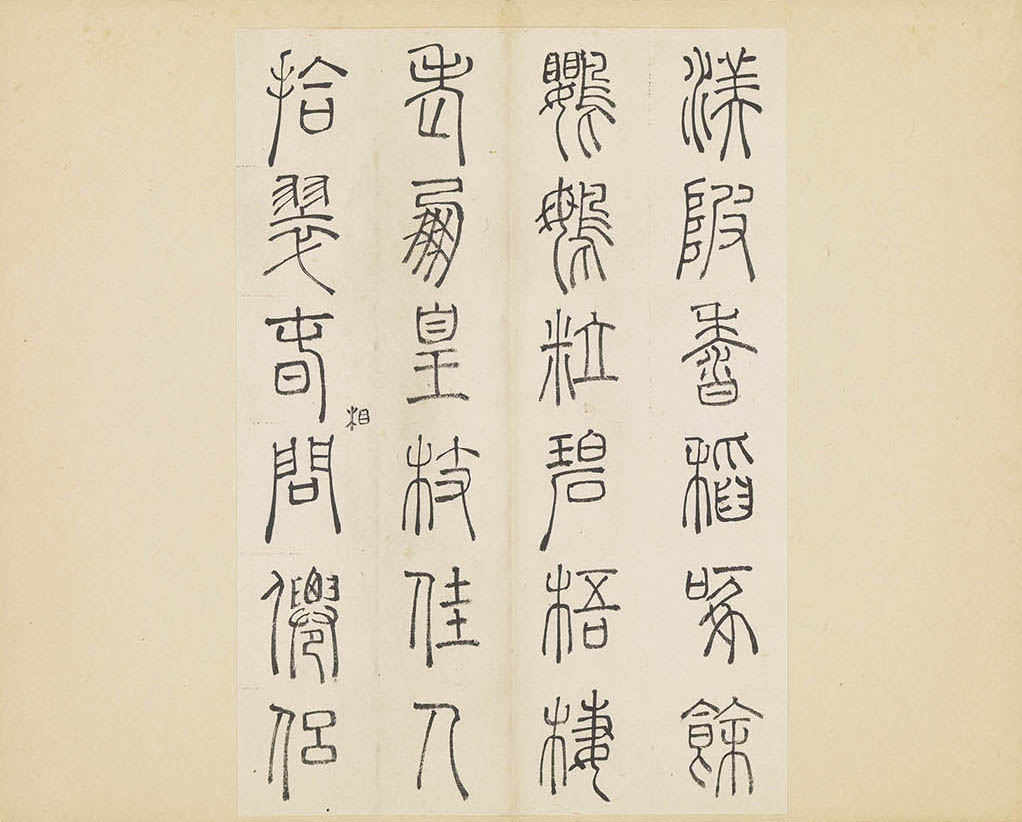

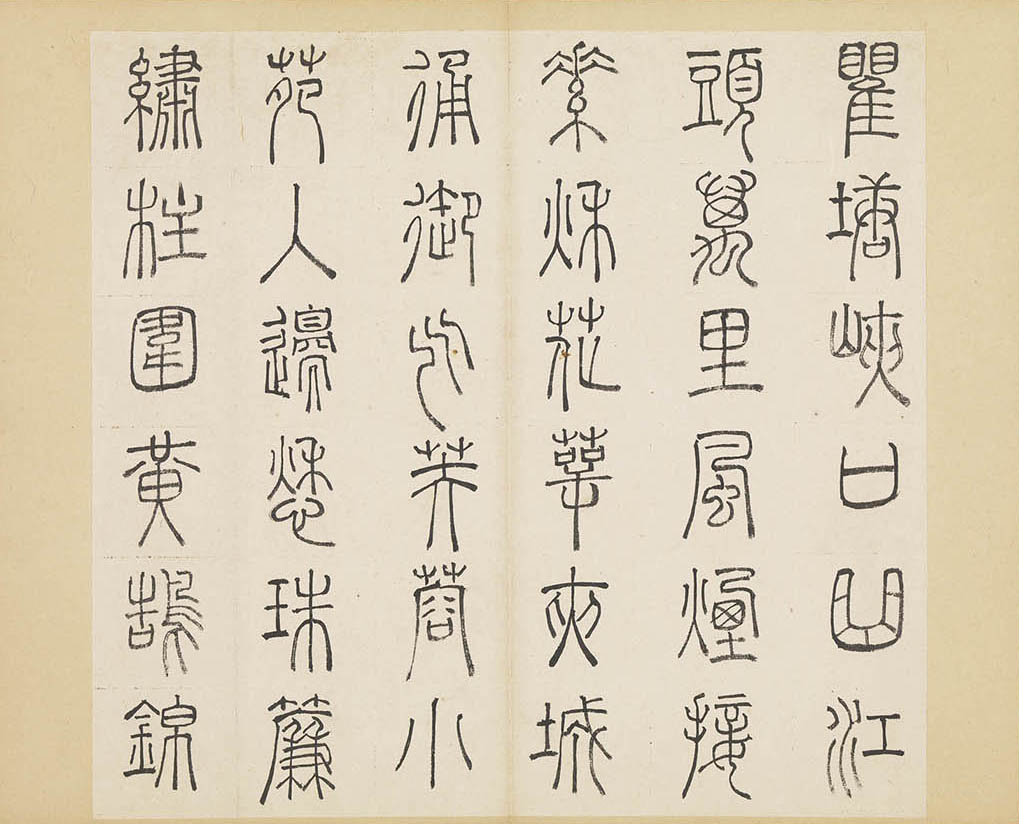

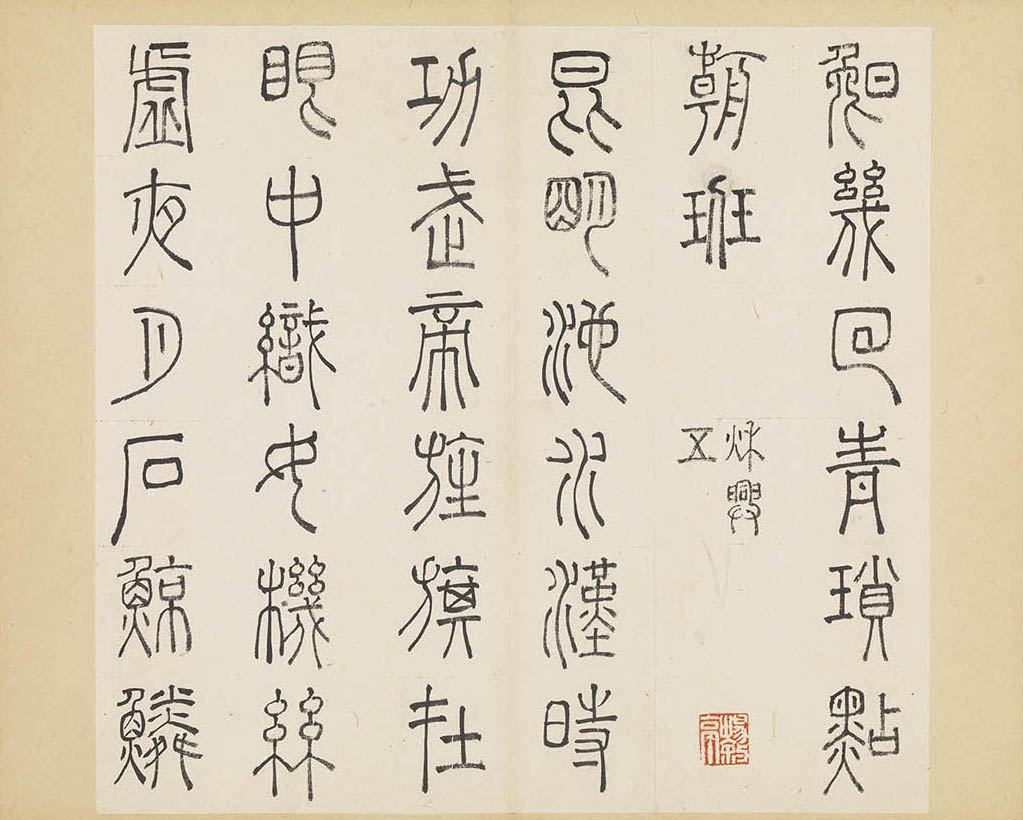

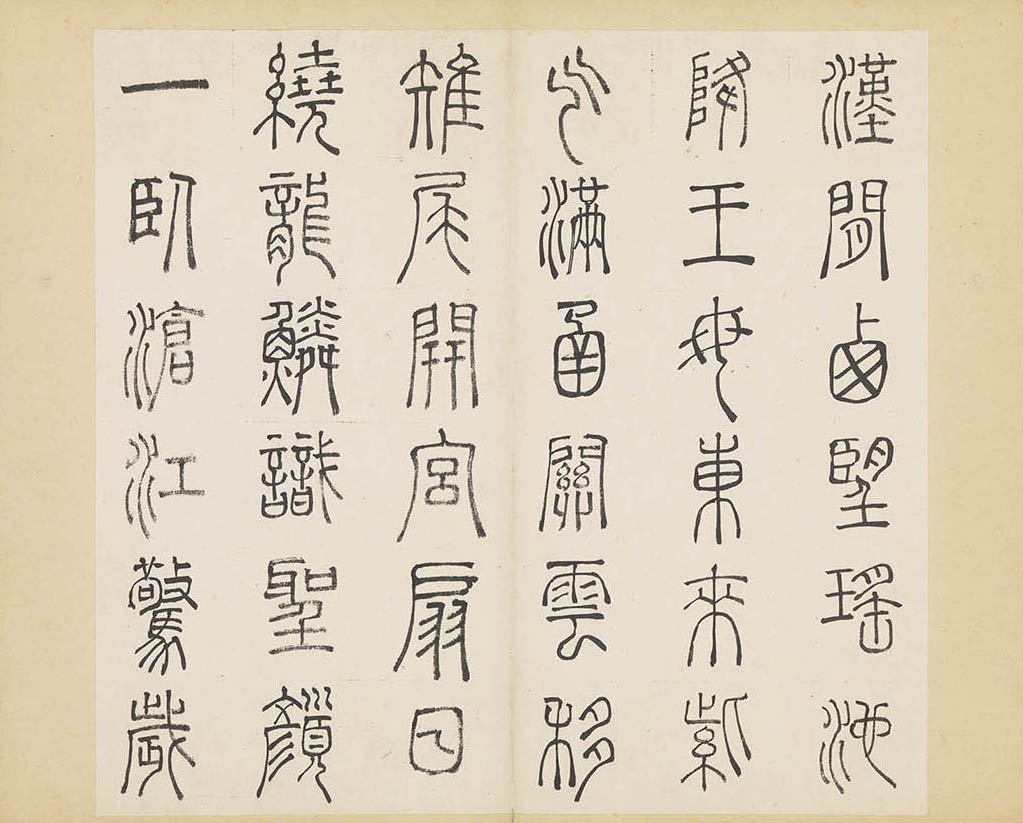

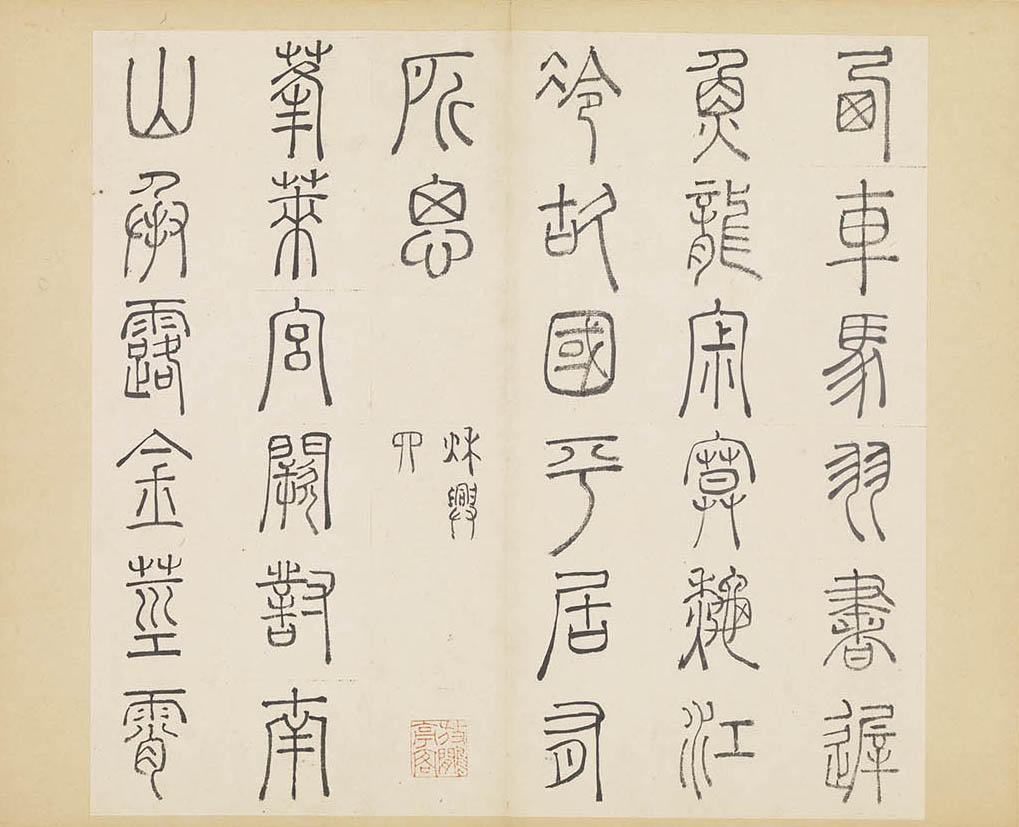

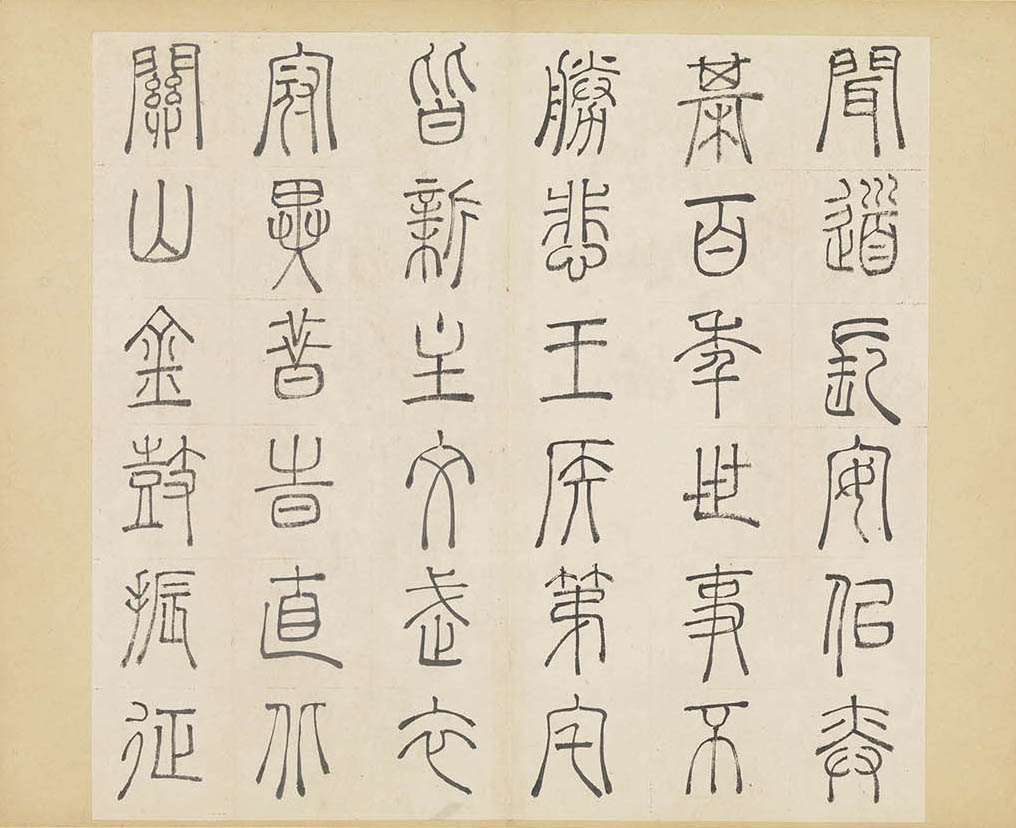

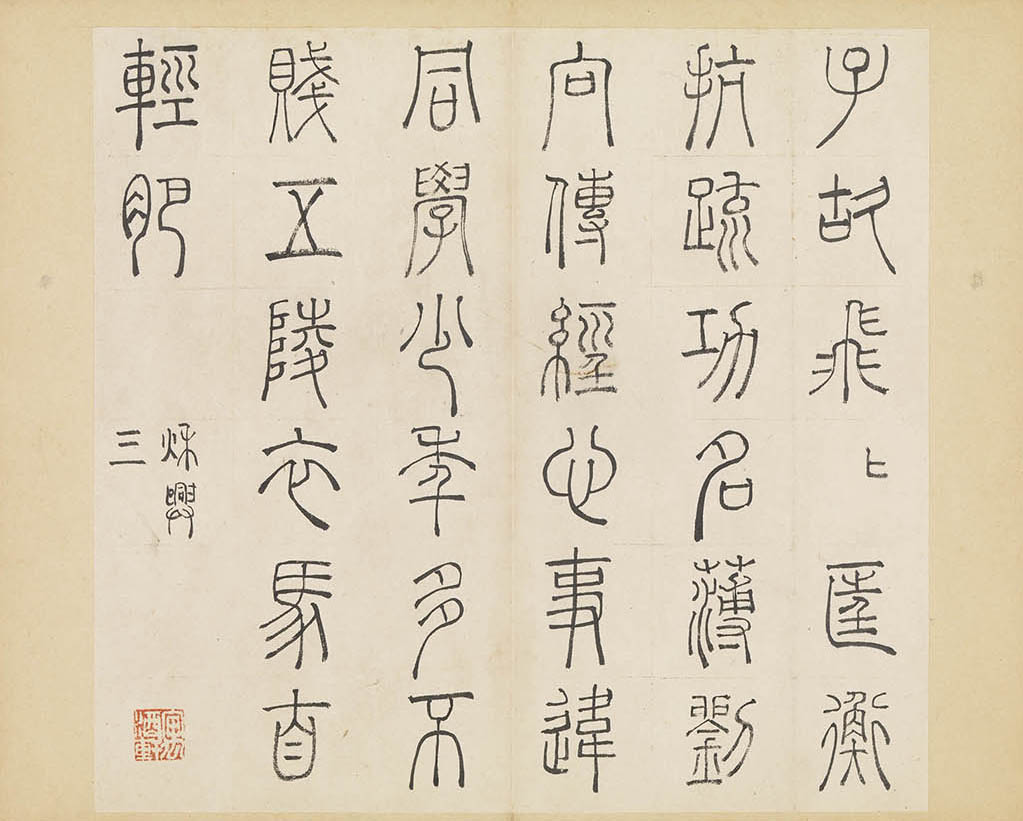

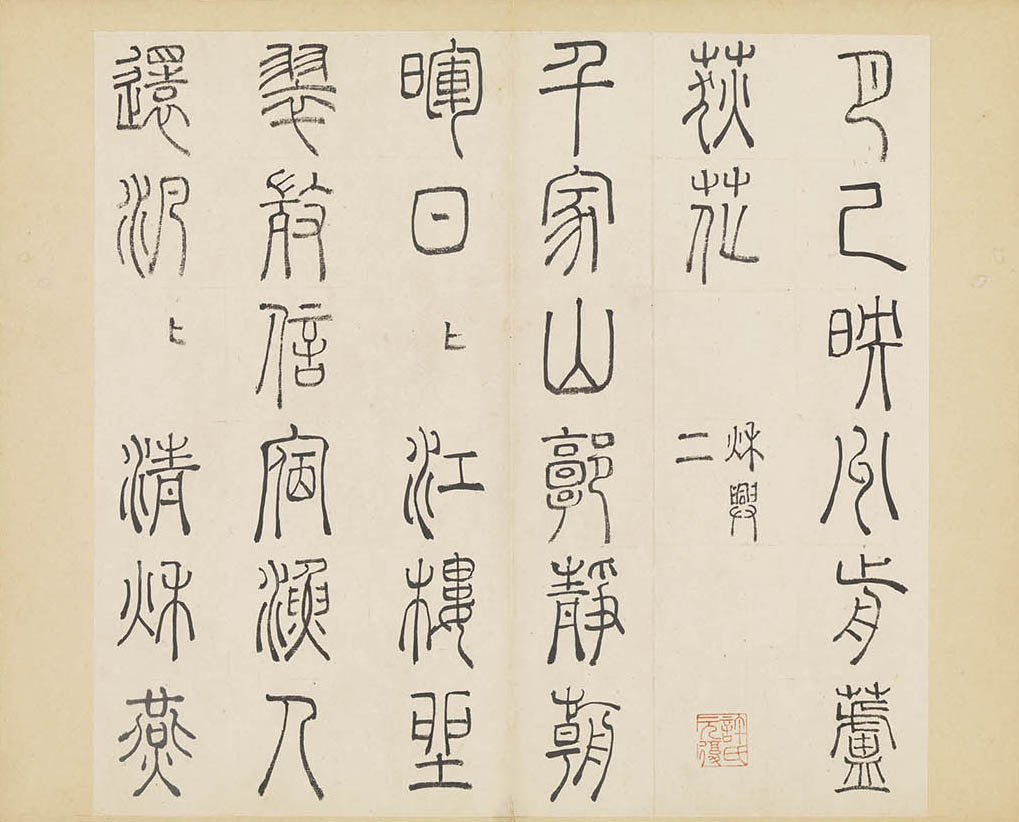

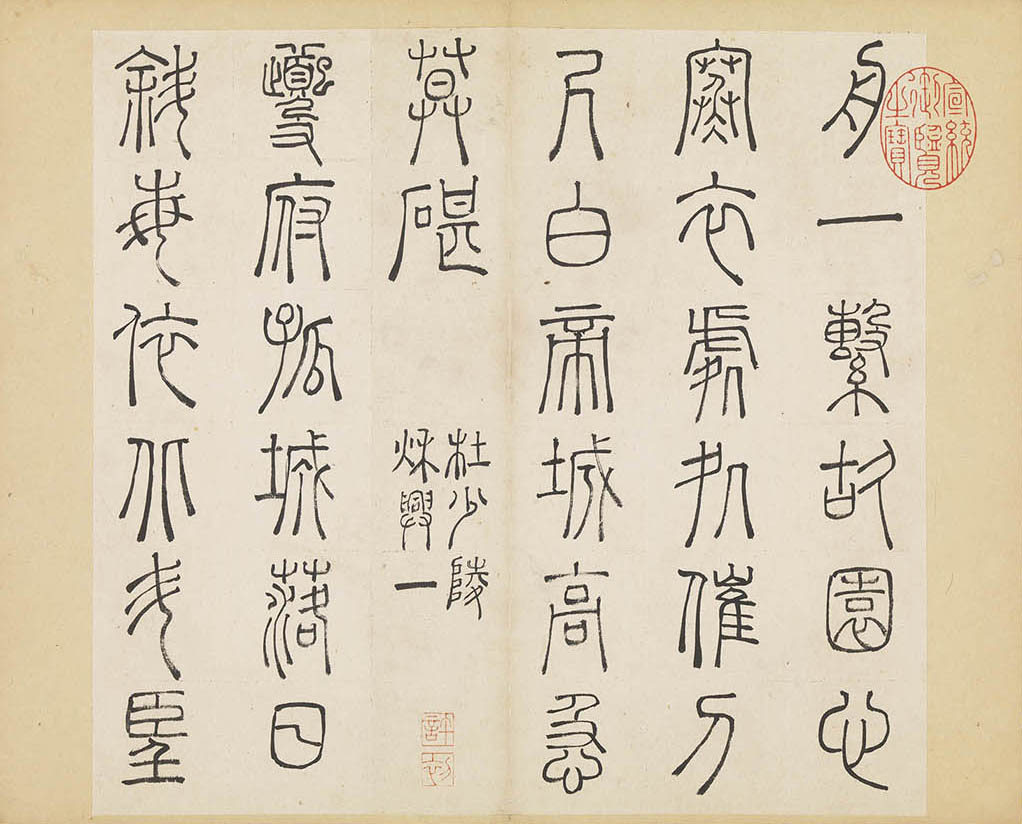

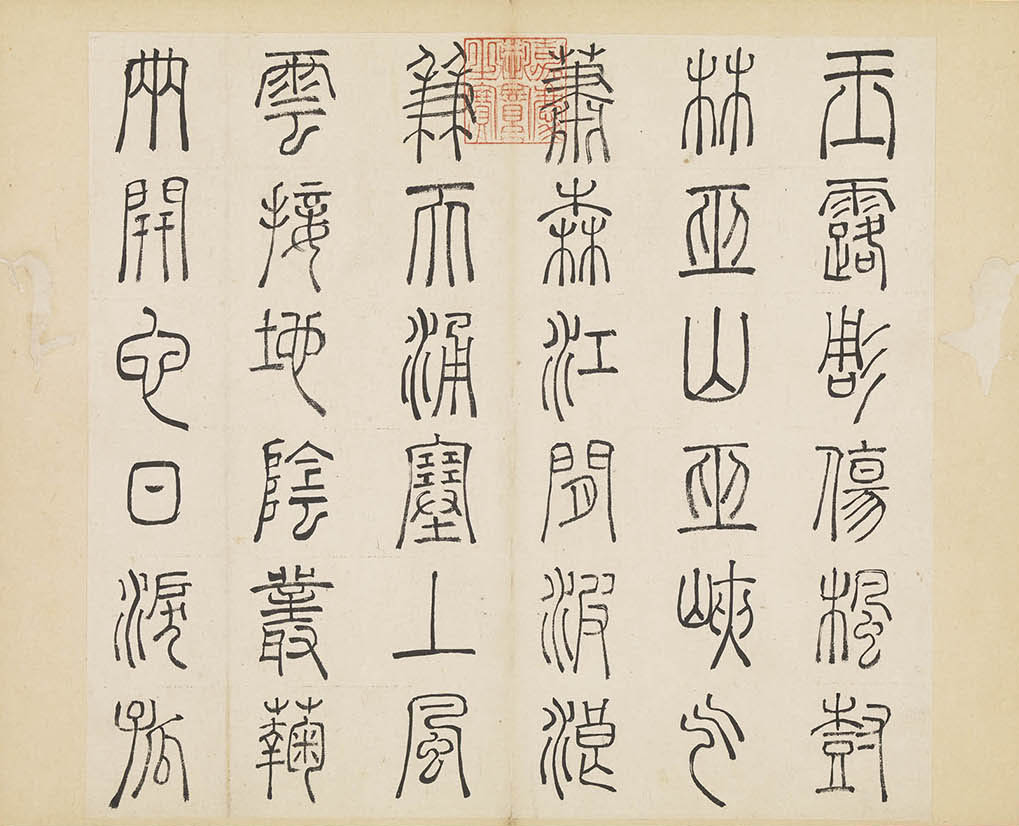

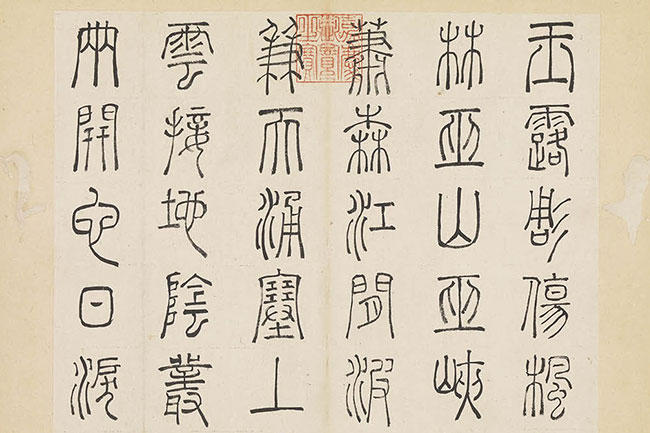

Du Fu's "Poems on Autumn Thoughts" in Seal Script

- Xu Chu (fl. ca. 16th century), Ming dynasty

Xu Chu (fl. ca. 16th century), a native of Suzhou in Jiangsu province, had the style name Yuanfu and the sobriquet Gaoyang. A scholar-official, he served for a time as the Official Registrar of the city of Nanjing. Fond of poetry and prose, engraving seals, and practicing calligraphy, he frequently brushed shoulders with the painter-calligraphers Wen Peng (1498-1573) and Wen Jia (1501-1583), as well as the poet Wang Shizhen (1526-1573).

These leaves were written during the third year of the Ming emperor Longqing's reign (1569). The entire volume was written in zhuanshu (seal script), although elements of kaishu (regular script) brushwork can be discerned in Xu's writing. Xu gave this work a lively, affectedly-unrefined appeal by concealing the sharpness of the brush's tip when writing characters' final strokes, and also by writing dots as though he was adorning the characters with pearls.

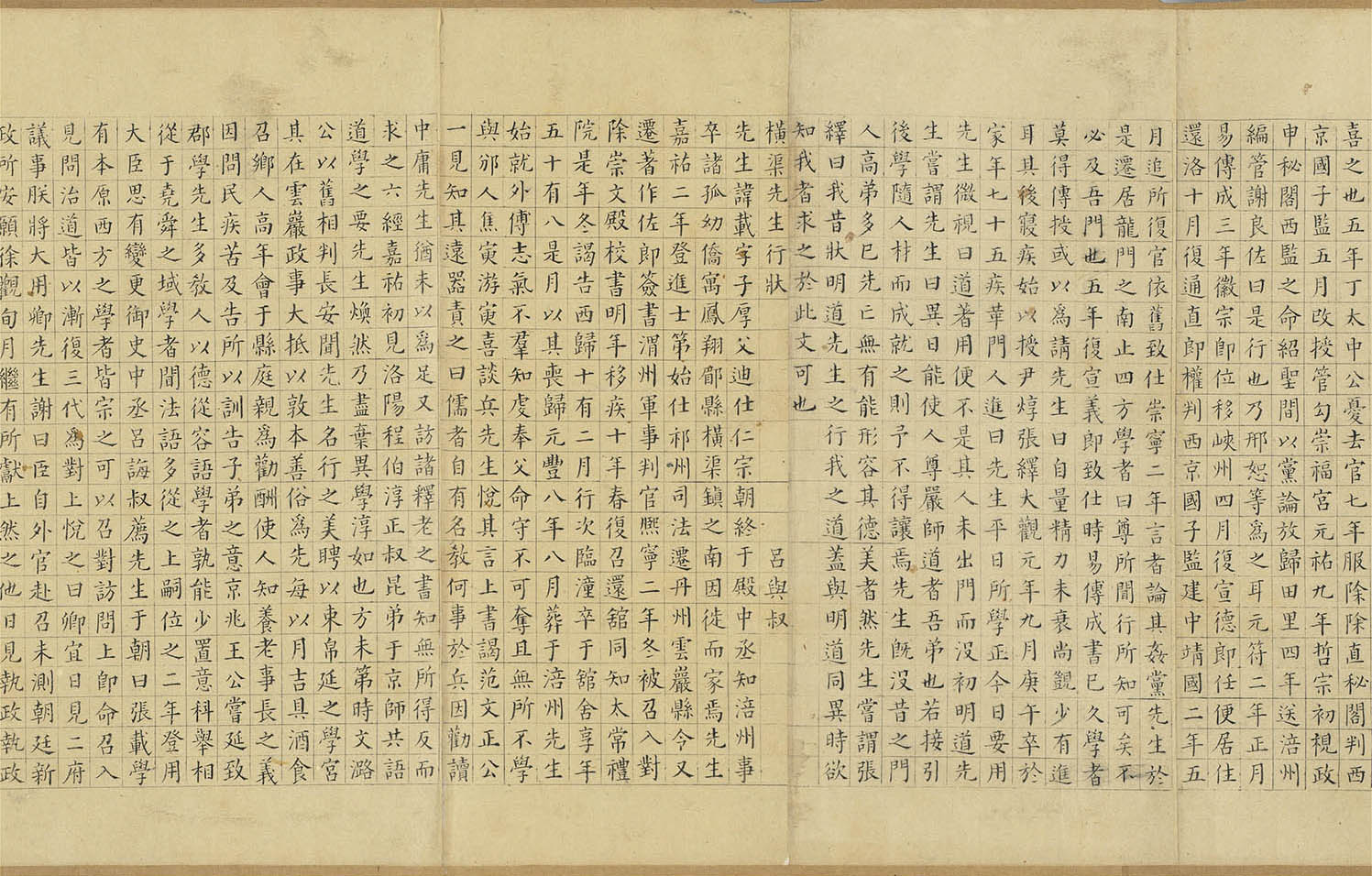

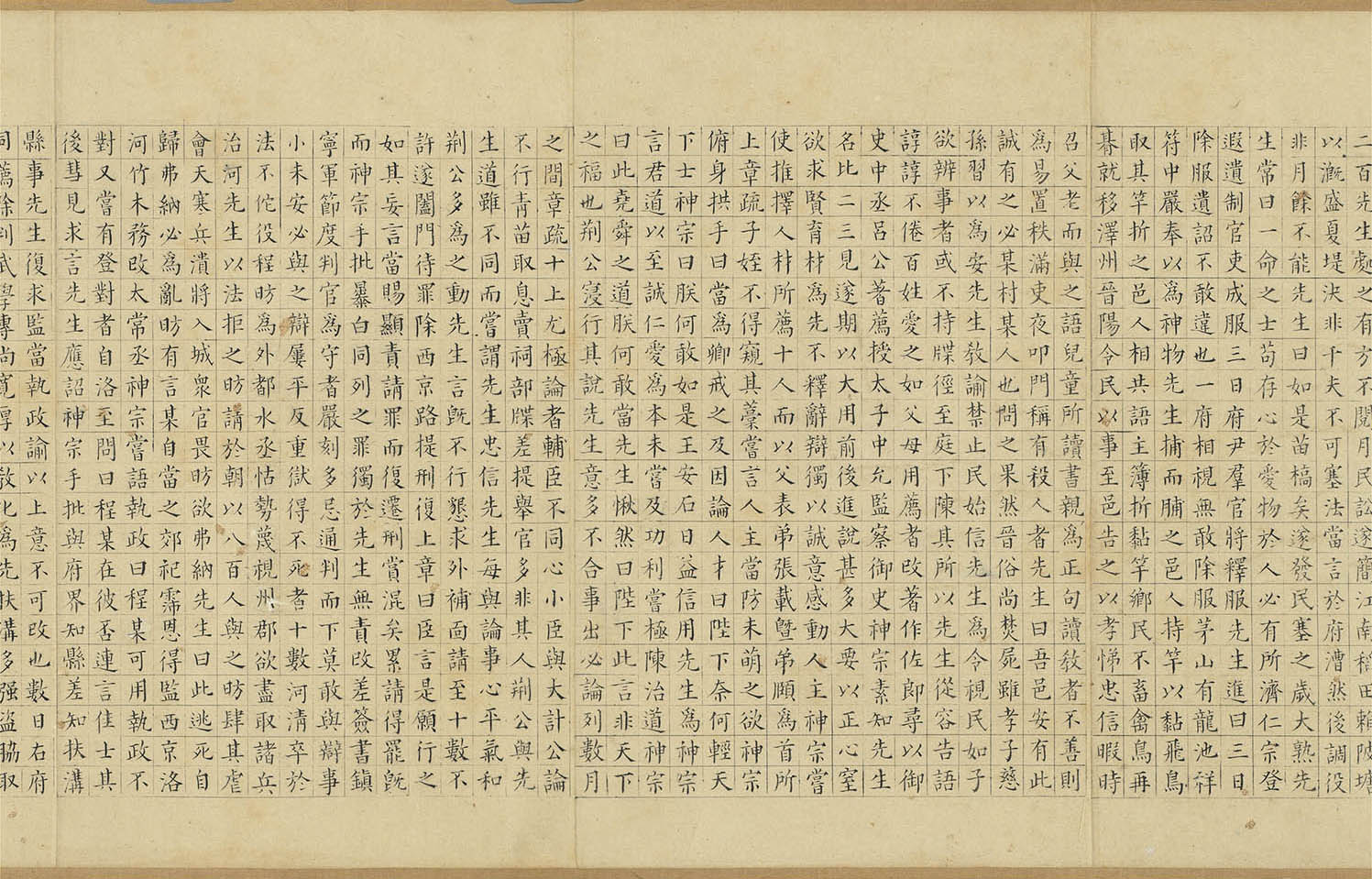

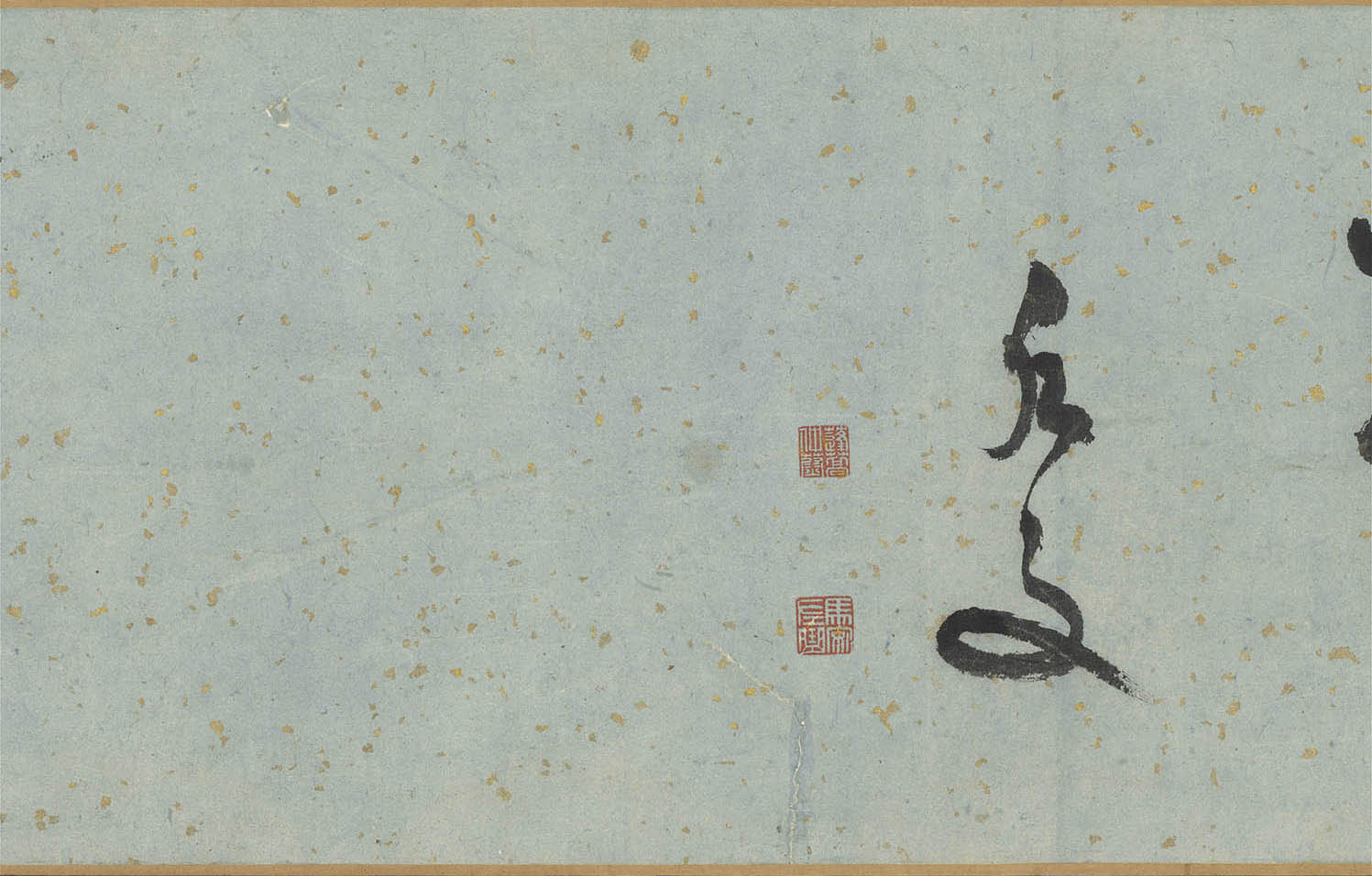

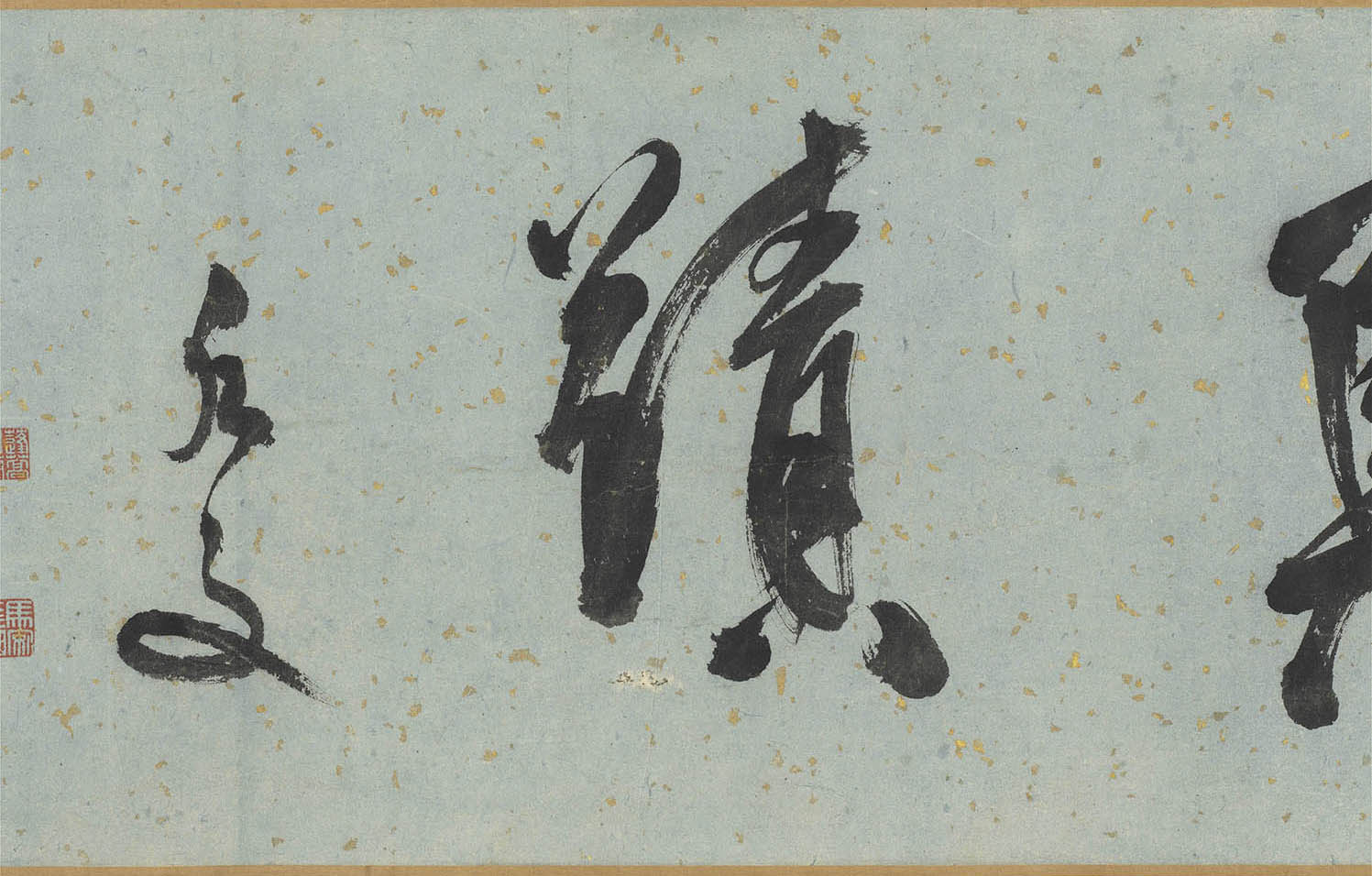

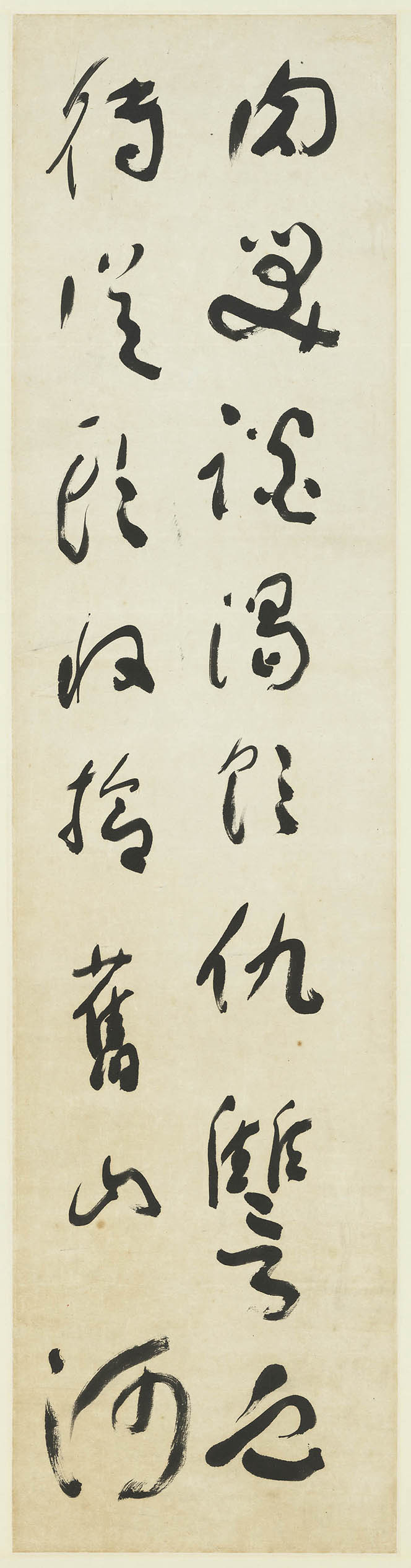

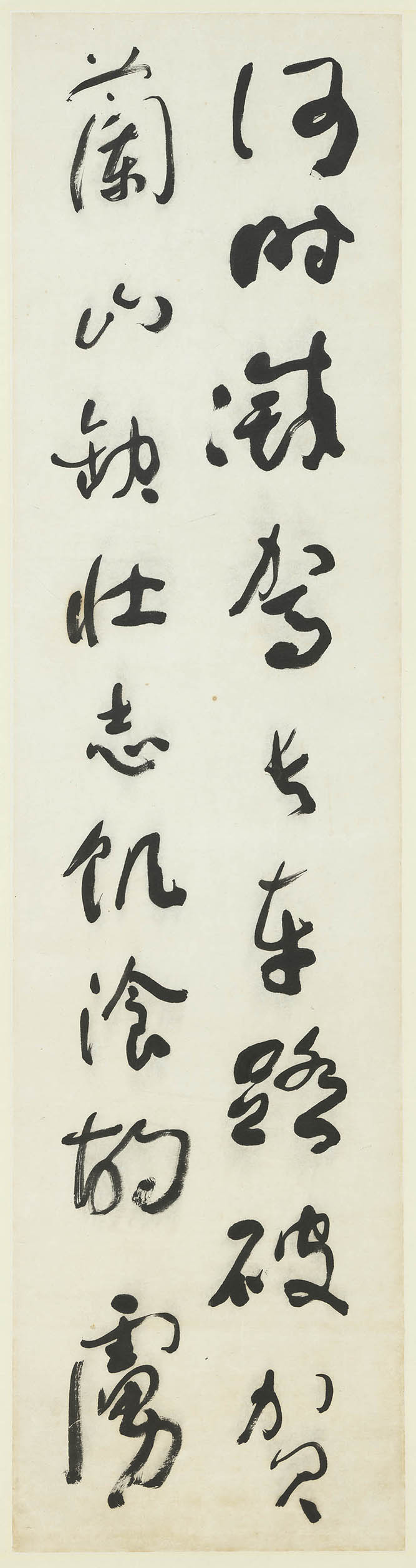

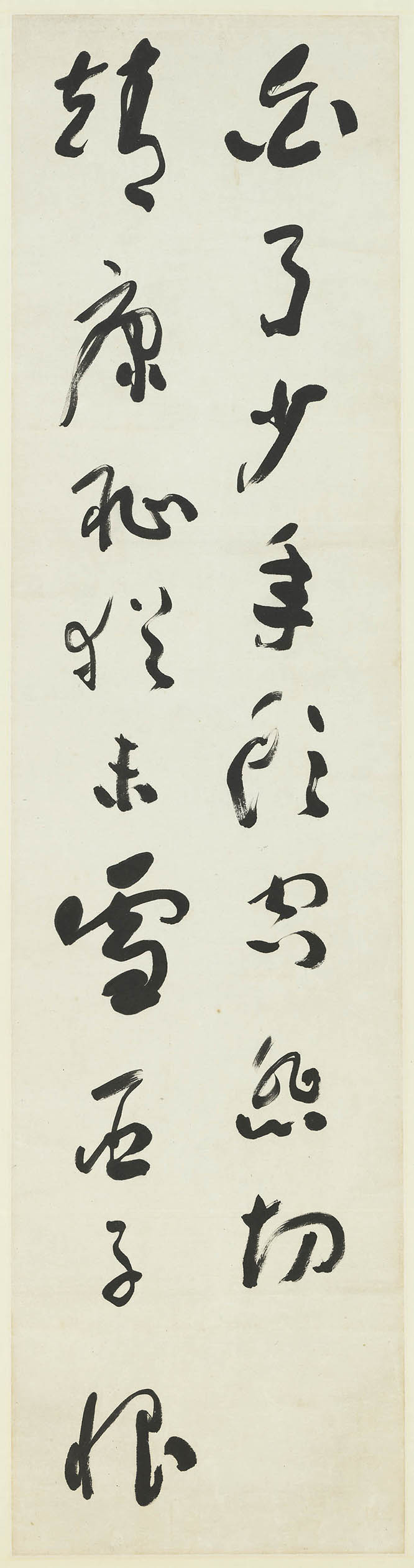

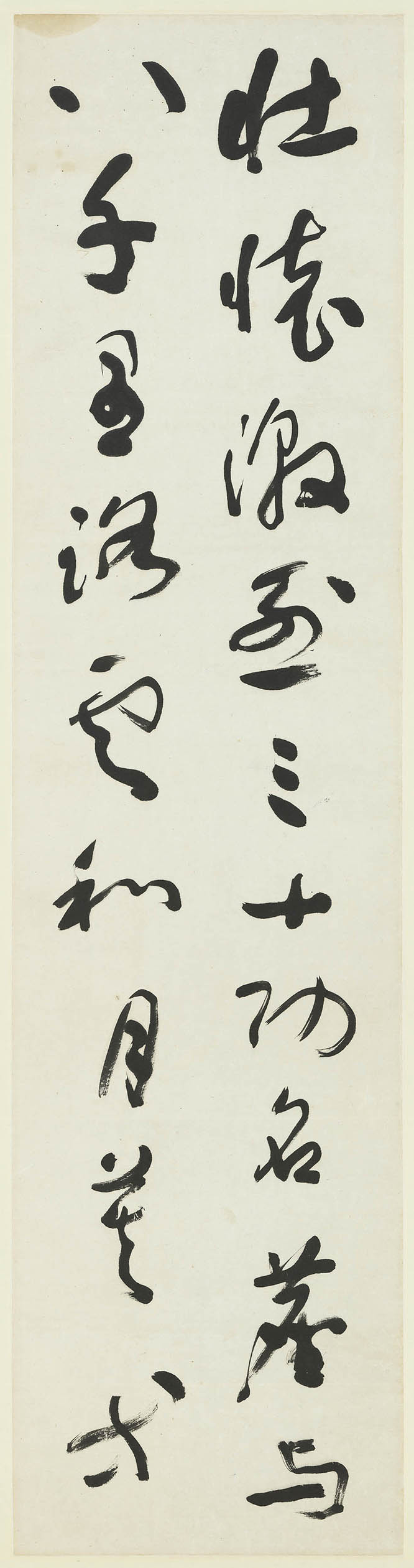

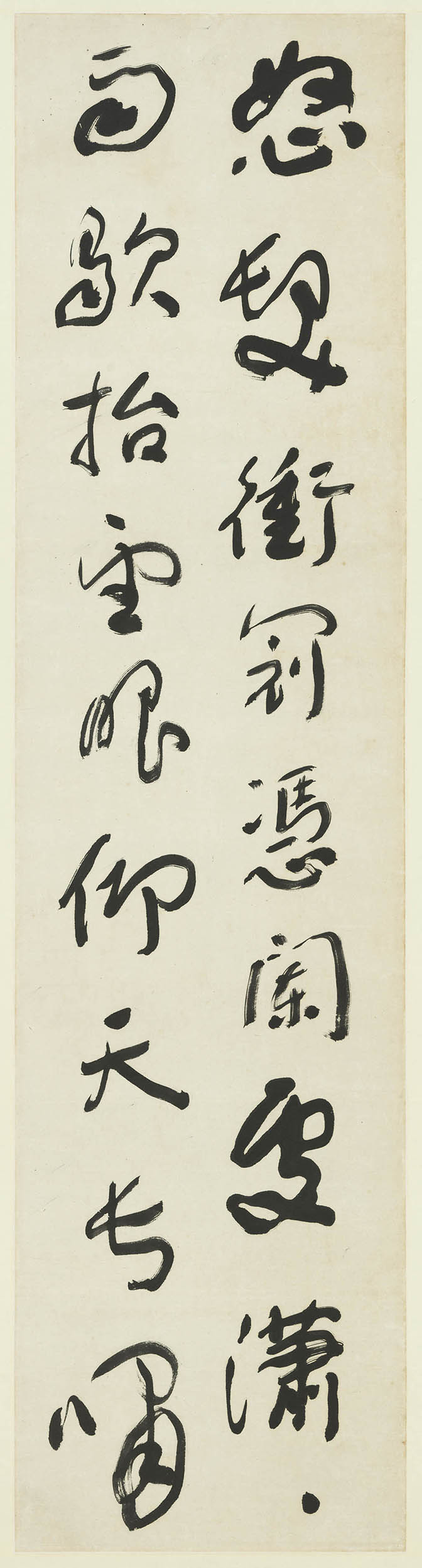

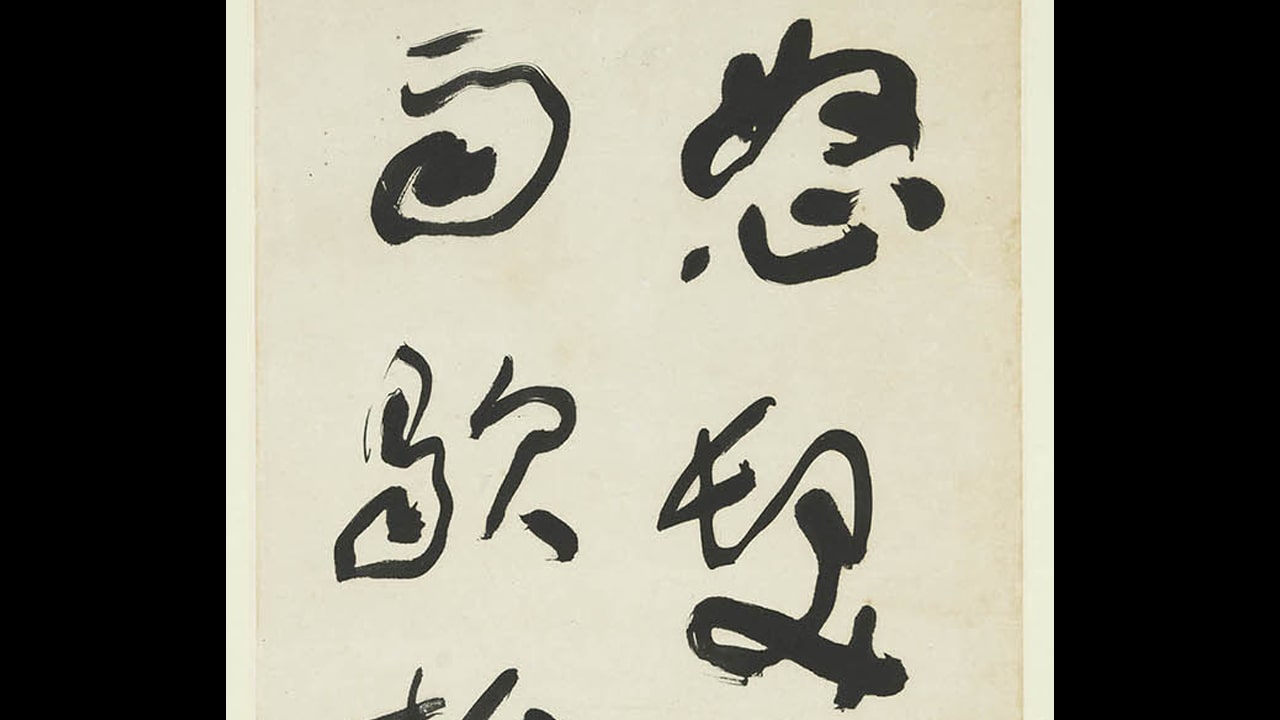

Six Scrolls of the Lyric Poem "Crimson River" in Grass Script

- Yu Youren (1879-1964), Republican era

Yu Youren (1879-1964), who came from Sanyuan in Sha'anxi province, had ancestral roots in Jingyang in the same province. His given name was Boxun, but he later went by Youren, before adopting the sobriquet Taiping Laoren (Old Man of Great Peace) in his later years. Yu was an important near-contemporary calligrapher as well as politician.

These scrolls contain poetic lyrics to the tune of "Crimson River" by General Yue Fei (1103-1142) of the Southern Song dynasty, inscribed when Yu was in his eighties. The brushwork is round, sumptuous, and ample, while the characters were given structures implying leisure and light. The characters, written ad libitum, take their forms naturally, amid richly contrasting applications of ink. Layers can be clearly discerned where the ink bled into the paper, giving this work an aura of resounding vastness. These scrolls exemplify the calligraphy of Yu's autumn years, when his skills were their most seasoned and his style fully mature.

Exhibit List

Swipe to watch table content

| Title | Artist | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Stele Commemorating Kong Zhou, Commandant in Chief of the Customs Barrier at Mount Tai | Han dynasty | |

| The Classic of Filial Piety | Attributed to Sun Guoting (fl. ca. late 7th century) | Tang dynasty |

| The Classic of Mountains and Seas | Cao Shan (ca. 14th century) | Yuan dynasty |

| Biographies for the Six Sages of Song Confucianism | Zhu Yunming (1460-1526) | Ming dynasty |

| Preface to the Orchid Pavilion | Wen Zhengming (1470-1559) | Ming dynasty |

| Du Fu's "Poems on Autumn Thoughts" in Seal Script | Xu Chu (fl. ca. 16th century) | Ming dynasty |

| Calligraphic Five-character Quatrain | Mi Hanwen (fl. ca. 17th century) | Qing dynasty |

| Poems by Shen Dawu Transcribed in Running Script on Four Scrolls | Lin Zexu (1795-1850) | Qing dynasty |

| Four Scrolls in Regular Script | Li Ruiqing (1876-1920) | Republican era |

| Six Scrolls of the Lyric Poem "Crimson River" in Grass Script | Yu Youren (1879-1964) | Republican era |