Paintings of Fauna

-

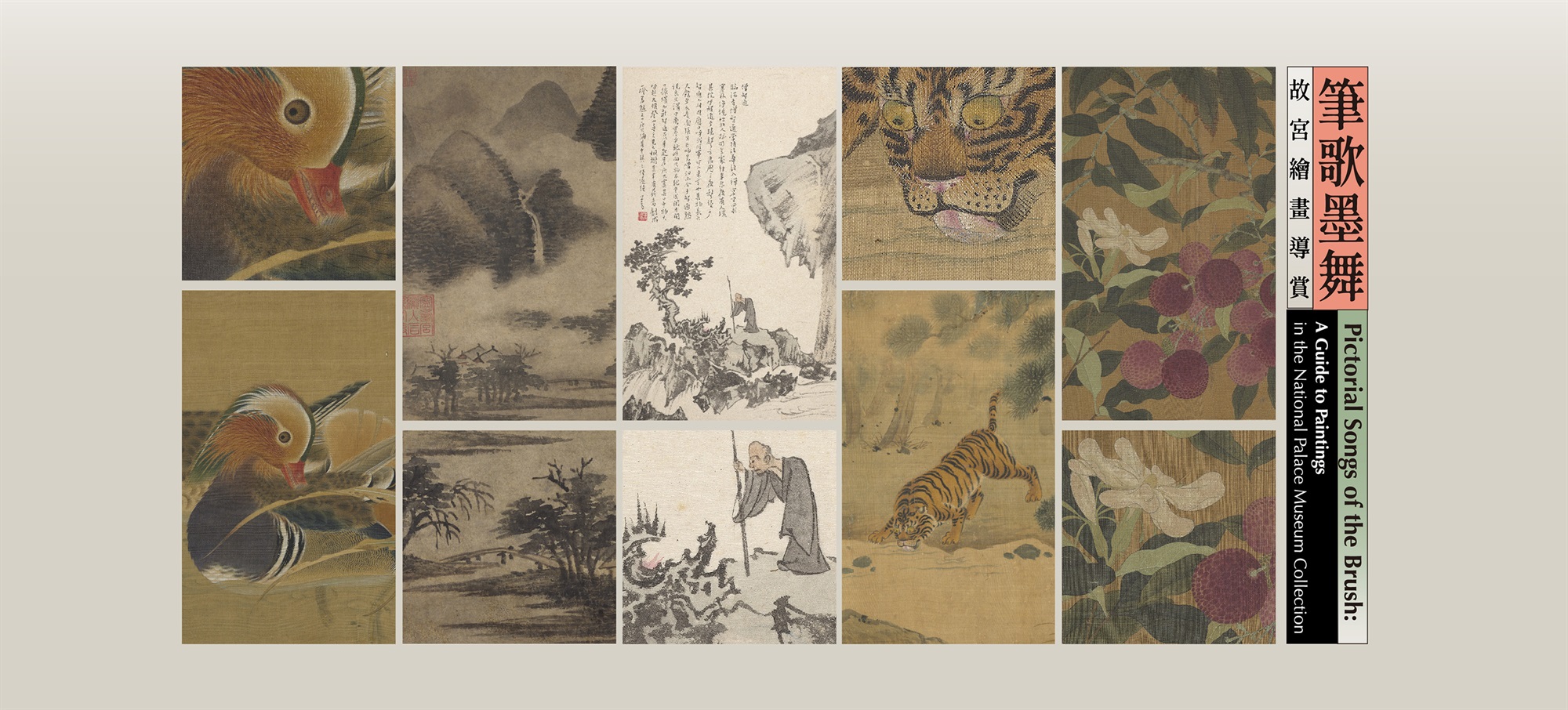

Tigers in a Windswept Forest

Zhao Ruyin, Ming dynasty

Zhao Ruyin (fl. 1436-1449) painted this work in 1441 for Yao Peng (fl. mid-15th century), assistant instructor at the Huai’an prefectural-level government-run Confucian academy. The painting depicts tigers in a variety of incredibly lively poses, including drinking spring water, licking their paws, and scraping their claws along. The rocky outcroppings, spring-fed streams, and trees’ forms, as well as the painting techniques used to create them, are also highly transformative. The tigers were painted in a manner very similar to that seen in “Tigers Painted by a Yuan Dynasty Artist” and “Zouyu” (named after a type of mythical animal similar to a tiger), both of which are held by the NPM, as well as “Floating Tigers,” painted by Zan Xugui (fl. 1465-1487) and held by the Cincinnati Art Museum. The stripes and whiskers on the tigers in this painting were all outlined with precision, possibly indicating that this piece was created in the tradition of the early Ming dynasty court painter Zhao Lian (fl. 1403-1424).

-

Painting from Life Depicting Plumage Attributed to Huizong

Anonymous, Ming dynasty

This scroll features two richly colored paintings in the gongbi style. The first work, a painting of seven birds and a solitary butterfly amid lychee branches and cape jasmine flowers, derives from the same sketch as a related work held by the British Museum. The NPM’s version, however, features a higher degree of meticulousness and accuracy in its portrayals, its details, and its spatial sensibility, as well as a richer variety of painting techniques. For example, in order to give the cape jasmine branches their spiny appearance, titanium dioxide pigment was applied atop the still-wet ink after the branches were painted using the unoutlined “boneless” technique. Additionally, adjoining layers of coloration were used to create the dried-out edges of some of the leaves’ surfaces. In light of the verisimilitude of the numerous seals apparently belonging to Xiang Yuanbian (1525-1590), it can be surmised that this piece was probably a high-quality copy made during the 17th century. The second painting’s water lilies, islet, and paired mandarin ducks were painted with more mastery than the first painting, with highly-accurate forms and coloration that dazzles without becoming gaudy. The brushwork is delicate and transformative, such that each feather and leaf was painted with tangible texturing, and the ducks’ submerged webbed feet appear filled with life. This is indeed an excellent specimen of 17th century painting.