The Maritime Era

To seek new markets and business opportunities, fleets from European countries such as Portugal and Spain had been locked in a maritime race since the late 15th century. Along the nautical routes near the west coast of Africa, the Cape of Good Hope and the Indian Ocean, or through the Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea, the Americas and the Pacific Ocean, discoveries were made and bases were created as the seafarers made their way to the East Asian Seas.

The East Asian trade structure was anchored by the tribute/sea ban systems of the Ming court in China, though the smuggling trade was also thriving. The arrival of the Europeans accelerated the waning of the sea ban policy. As a response to the changing times, the Ming dynasty finally legalized international trade in Yuegang, Zhangzhou, Fujian province in the late1560s.

Goods, plants and silver circulated throughout the world in massive quantities for the first time in history, bringing people a newfound understanding of the sea. Aside from the resources and opportunities, challenges also presented themselves. The sea, as the bridge between the landmasses, preluded a new age for the flow and movement of goods.

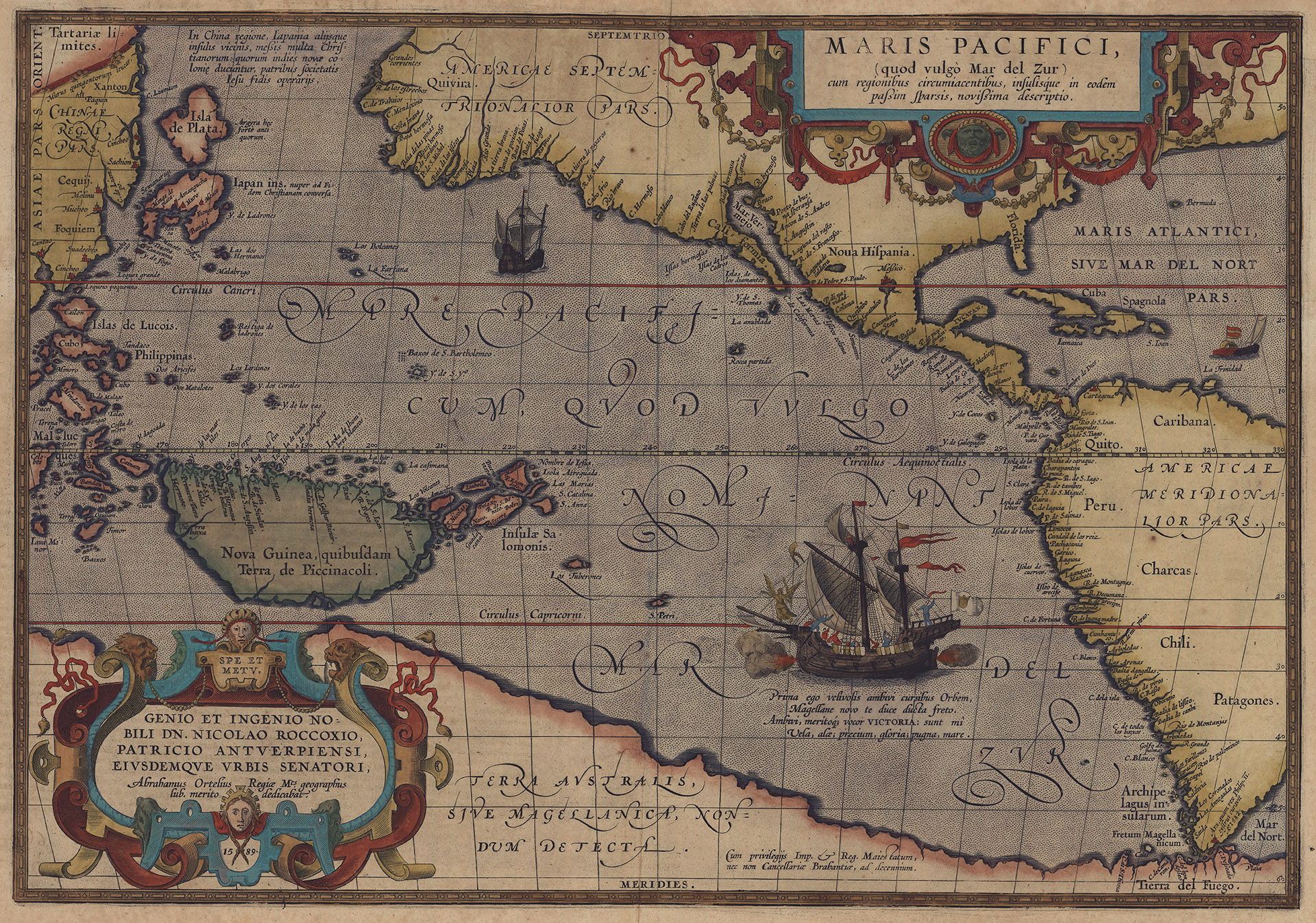

- Maris Pacifici (Description of the Pacific Ocean) | 1589

- Abraham Ortelius, Netherland

- Height 56.9cm, Width 47.1cm

- National Museum of Taiwan History 2009.011.0460

Copper-plate printed on paper and hand colored, Maris Pacifici (Description of the Pacific Ocean) is from the 1601 edition of Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Atlas of the World) by Netherlands cartographer Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598). It is the earliest known printed map to feature the Pacific Ocean. On the right is the Americas, and on the left are the East Asian Seas. Occupying the bottom portion is the hypothetical continent, Terra Australis (the Southern Land), also called Magellanica. The vast water body in the middle is the Pacific Ocean. A ship on the lower right is led by an angel across the Fretum Magellanicum (Strait of Magellan), entering the Pacific Ocean through the southern tip of South America. The ship is a depiction of the Victoria, one of Ferdinand Magellan’s (1480-1521) squadron of kraak during his circumnavigation around the globe.

Portugal and Spain had been locked in a tight race of maritime expeditions since the late 15th century. In 1519, King Carlos I (1500-1558) of Spain funded Portuguese explorer Magellan’s expedition, which set sail from Seville. The long and treacherous voyage ended in 1522 with the return of the only surviving ship, the Victoria. Magellan’s circumnavigation inspired the creation of Maris Pacifici as well as similar nautical maps that followed, reflecting Europeans’ fervent passion for maritime expedition in the 16th century.

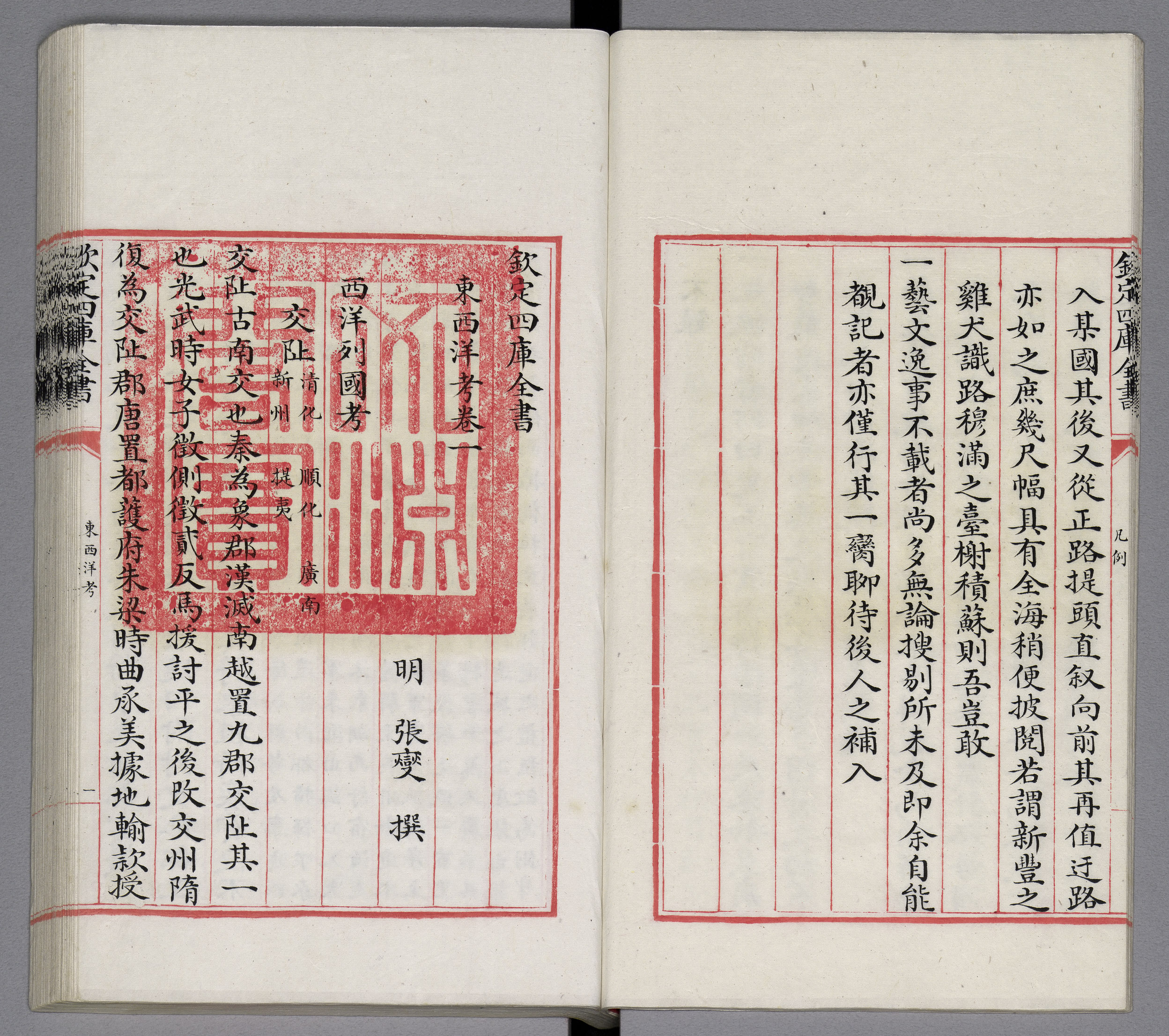

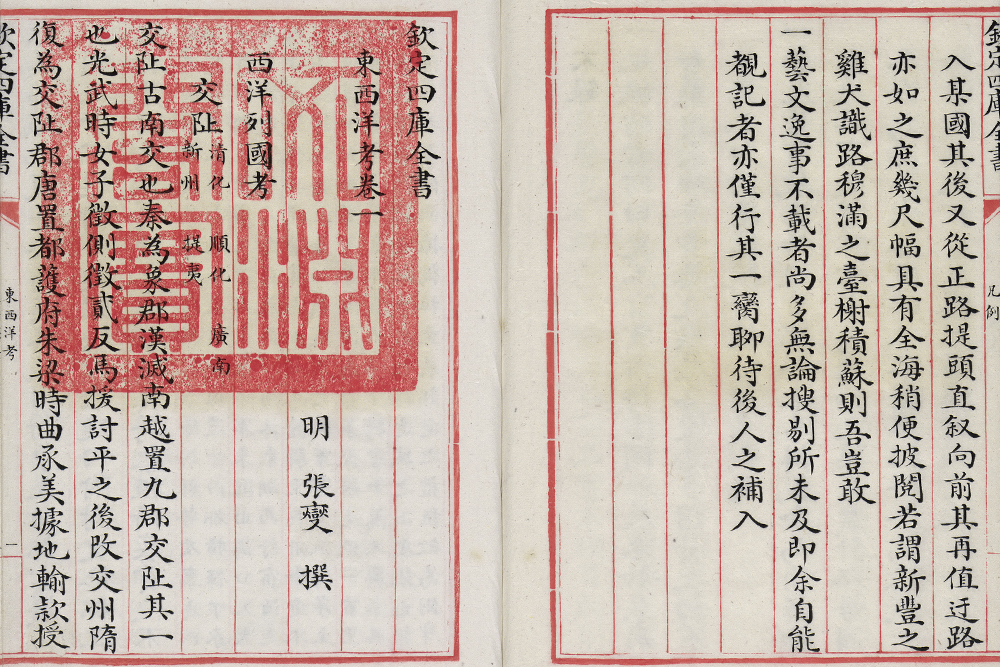

- Dongxi Yang Kao (On the Eastern and Western Oceans) | 1617

- Zhang Xie, Ming Dynasty

- Qing manuscript copy of the Siku Quanshu (Wenyuange Edition), Qianlong rei

- Length 31.5cm, Width 20cm

- National Palace Museum Gu Ku 012877-012880 National Treasure

Completed in 1617, Dongxi Yang Kao (On the Eastern and Western Oceans) is an important document about the oceans from the Ming dynasty. The author, Zhang Xie, whose style name was Shaohe and sobriquet Haibin Yishi, was a native of Longxi, Fujian. Zhang compiled the individual Haidao Zhenjing (nautical routes and compass charts) from the Ming dynasty into one document and added contemporary events. Dongxi Yang Kao sums up the countries that had come into contact with southeast China up to the early 17th century as well as the trade activities.

Countries listed in this book are divided into a group of 15 from the west oceans and a group of seven from the east oceans. Japan and Dutch are singled out in Waiji Kao (Additional Records). Descriptions of each country begins with a historical background, followed by details on notable landmarks, local products and trade. Countries from the west oceans include Cochin, Champa, Siam, Xiagang (modern Java), Cambodia, Dani (modern Kelantan), Palembang, Malacca, Aceh, Pahang, Johor, Dingjiyi, Sigi Gang, Bandjarmasin and Chimen (Timor) with information regarding geography, history, climate, attractions and products, a truly thorough account.

- Dragon-shaped Kendi in Underglaze Blue | ca. 1575-1600

- Height 22.4cm, Diameter (Rim) 5.7cm

- Rijksmuseum AK-RAK-1981-1

The term, “kendi,” is derived from Sanskrit, referring to “kundika,” a vessel of ritual liquid and a daily object in India. In China, most kendis were produced in Jingdezhen and the Dehua kilns, and some were produced in Swatow. The majority of kendis produced during the Ming and Qing dynasties were exported to Southeast Asia. With a dish-shaped rim, this kendi has a long and slender concaving neck, ovaloid belly and flat foot. A dragon ascending along the curved belly and looking upwards functions as the spout. The rim and the neck are embellished with four tiers of patterns. From the top down are a band of triangular decoration; twined floral motifs; cloud-shaped panels filled with Chinese chainmail motifs; banana-leaf lappet motifs. The left and right shoulders are adorned with the dragon’s spreading wings with its scales exposed on the back, and the belly is painted with the wave patterns. Scholars had pointed out that this kendi was paired with a lid, which has been lost.

This piece is dated to approximately the late 16th century, a period when Jingdezhen produced kendis in additional animal forms such as the elephant , toad and phoenix.The elephant- and toad-shaped kendis are also among the collection of the shrine of Shaykh Safi al-Din Ardabili in Ardabil, Iran. The pairing of the winged dragon motif with the wave motif in underglaze blue started in Jingdezhen back in the 15th century. Examples include Bowl with Sea Creature Motif in Underglaze Blue and Stem Cup with Sea Creature Motif in Underglaze Blue from the Xuande reign (1426-1435), Ming dynasty from the collection of the National Palace Museum. Kendis in the form of a winged dragon are also among the collection of Sir Percival David (1892-1964, currently the British Museum collection). An example is the late-16th century Swatow ware, a kendi in the shape of winged dragon in wucai polychrome decoration.

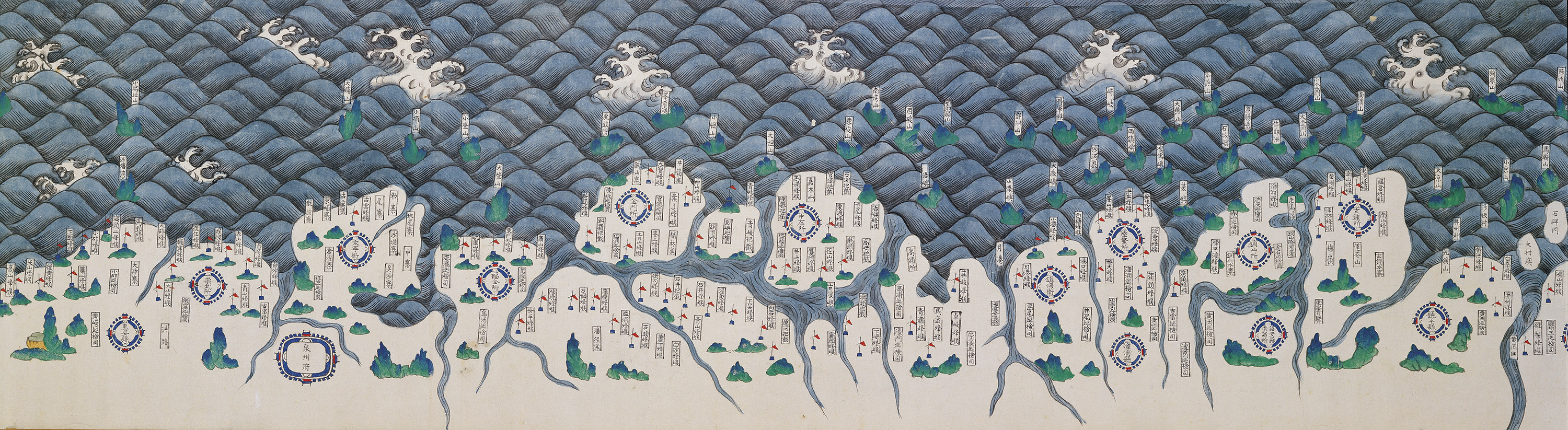

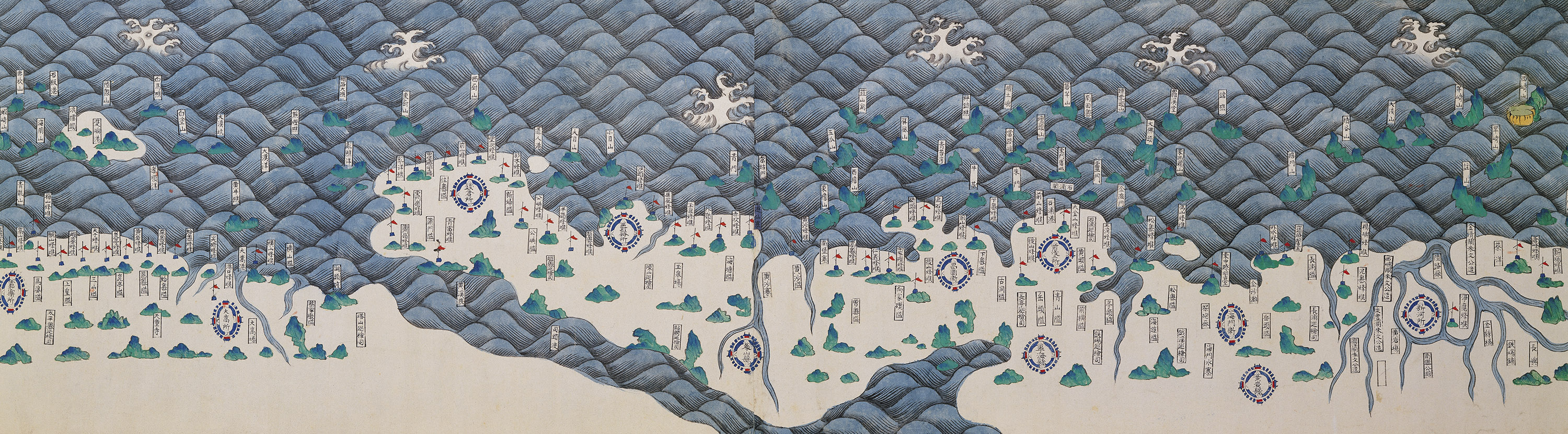

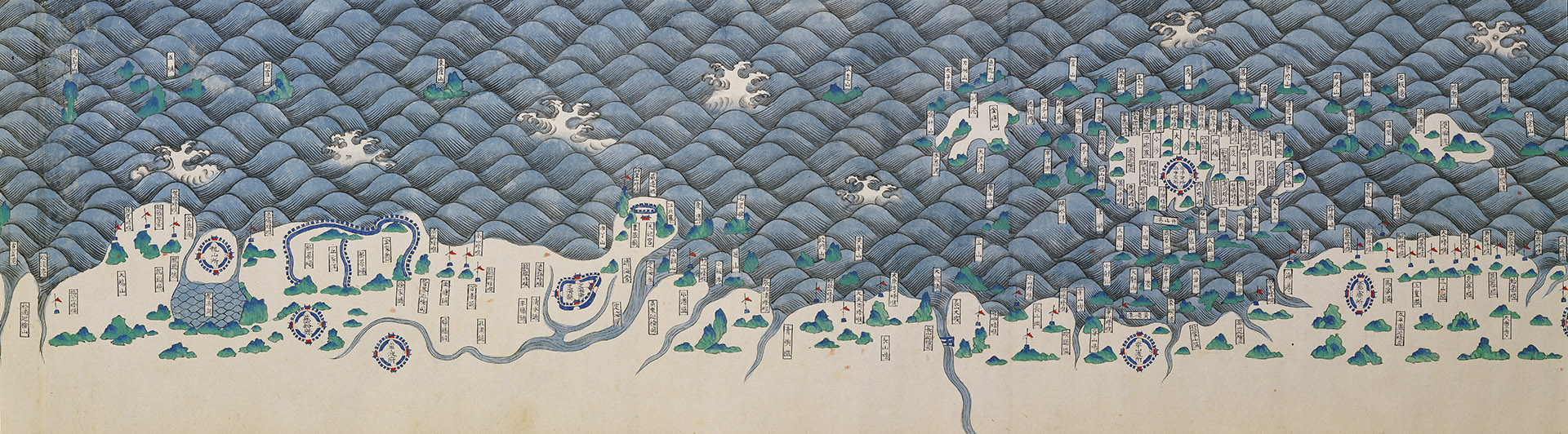

- Nautical Map | ca. 1560s

- Height 30.5cm, Width 2,081cm

- National Palace Museum Ping Tu 020865

Color painted on paper, Nautical Map depicts coastal features such as the coastline, rivers and islands between Hainan Island and the Yalu River estuary in the style of a landscape painting. Land depictions focus on military strongholds such as military posts, citadels, waterfront fortresses and watchtowers, showing signs of influence from the 1562 Chouhai Tubian (Illustrated Book on Maritime Defense) by Zheng Ruoceng (1503-1570). At the frontispiece are four words, “hai bu yang bo” (a peaceful ocean without waves), and a brief account at the endpiece narrates the strategic defense along the coasts of Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangnan, Shandong, North Zhili and all of Liaodong. The section on Fujian mentions, “defense against intruders from Jinmen and Yuegang,” which dates this map to the 1560s, prior to the legalization of Yuegang as a trading port in 1567. Without a specific title, “Strategic Coastal Defense between Hainan Island and Yalu River Estuary” should be a fitting one based on the painting and the account.

Since the mid-14 th century, the Ming dynasty seized geopolitical and trade dominance in East Asia through the sea ban and tribute systems. However, smuggling remained an active form of illegal trading on the sea. Local forces formed alliances and weaponized, becoming what the government considered to be “pirates.” Nautical Map illustrates the coastal defense posts during the Ming dynasty with an emphasis on facilities like watchtowers, reflecting the coastal defense approach of Ming officials, such as Hu Zongxian (1512-1565) against piracy in the mid-16 th century. Drastically different than those from the European contemporaries, the map alludes to a weakening sea ban system.

- Dish with Compass and Sail Ship Motifs in Wucai Polychrome Decoration | 1573-1620

- Zhangzhou Ware

- Wanli Reign, Ming Dynasty

- Height 7.8cm, Diameter (Rim) 34.7cm

- Guimet National Museum of Asian Arts

The Ming court lifted the sea ban during the reign of Emperor Longqing (1567-1572),and Yuegang, which is located in Zhangzhou, Fujian province, became a legalized port for maritime trade in China. Since then, the port had become a hub for merchants from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou to connect with the world.In addition to the Jingdezhen ware in underglaze blue, the ceramic ware onboard the ships bound for foreign destinationsalso included locally produced ceramics, which had been regarded as Swatow wareamong the academia until the 1980s. The overturn came after archeologists discovered the kiln sites in Nansheng and Wuzhai in Zhangzhou, Fujian province. Through cross-comparisons made between the excavated and collected pieces, it is confirmed that a portion of the so-called Swatow ware are actually from the Zhangzhou kilns, including this unique large dish from the collection of the Guimet National Museum of Asian Arts in France. As shown in the photo, the upper surface of this dish is decorated with motifs in overglaze alum red and turquoise blue. Written in the center are three characters, “Tianxia Yi (One under the Heaven),” surrounded by two circles of inscriptions. The inner set refers to the nine stars in the Taoist Big Dipper, which consists of the two “attendant” stars, and the outer set refers to the heavenly and earthly ordinals as well as the divination hexagrams from YiChing (Book of Changes). Additional decorations include the sailing ship, fish, wave, mountain and constellation motifs. Works of similar style are also found in museums in countries such as Japan and the Netherlands.In particular, the excavated pieces from the Jokamachi (castle town) in Osaka, when paired with the collected pieces in Japan,may explain the export of Zhangzhou ware to not onlythe neighboring regions, but throughout Europe as East Asiaaligned with the global trade after the second half of the 16 th century.

Also worth noting is that the inscriptions in the center of the dish, “Tianxia Yi,” may be interpreted as anchoring the world through one direction. Under the context of maritime exploration, perhaps dishes such as this, as scholars pointed out, could be used as a backup compass during the voyage.