Introduction

To meet the need for recording information and ideas, unique forms of calligraphy (the art of writing) have been part of the Chinese cultural tradition through the ages. Naturally finding applications in daily life, calligraphy still serves as a continuous link between the past and the present. The development of calligraphy, long a subject of interest in Chinese culture, is the theme of this exhibit, which presents to the public selections from the National Palace Museum collection arranged in chronological order for a general overview.

The dynasties of the Qin (221-206 BCE) and Han (206 BCE-220 CE) represent a crucial era in the history of Chinese calligraphy. On the one hand, diverse forms of brushed and engraved "ancient writing" and "large seal" scripts were unified into a standard type known as "small seal." On the other hand, the process of abbreviating and adapting seal script to form a new one known as "clerical" (emerging previously in the Eastern Zhou dynasty) was finalized, thereby creating a universal script in the Han dynasty. In the trend towards abbreviation and brevity in writing, clerical script continued to evolve and eventually led to the formation of "cursive," "running," and "standard" script. Since changes in writing did not take place overnight, several transitional styles and mixed scripts appeared in the chaotic post-Han period, but these transformations eventually led to established forms for brush strokes and characters.

The dynasties of the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) represent another important period in Chinese calligraphy. Unification of the country brought calligraphic styles of the north and south together as brushwork methods became increasingly complete. Starting from this time, standard script would become the universal form through the ages. In the Song dynasty (960-1279), the tradition of engraving modelbook copies became a popular way to preserve the works of ancient masters. Song scholar-artists, however, were not satisfied with just following tradition, for they considered calligraphy also as a means of creative and personal expression.

Revivalist calligraphers of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), in turning to and advocating revivalism, further developed the classical traditions of the Jin and Tang dynasties. At the same time, notions of artistic freedom and liberation from rules in calligraphy also gained momentum, becoming a leading trend in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Among the diverse manners of this period, the elegant freedom of semi-cursive script contrasts dramatically with more conservative manners. Thus, calligraphers with their own styles formed individual paths that were not overshadowed by the mainstream of the time.

Starting in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), scholars increasingly turned to inspiration from the rich resource of ancient works inscribed with seal and clerical script. Influenced by an atmosphere of closely studying these antiquities, Qing scholars became familiar with steles and helped create a trend in calligraphy that complemented the Modelbook school. Thus, the Stele school formed yet another link between past and present in its approach to tradition, in which seal and clerical script became sources of innovation in Chinese calligraphy.

Selections

Oversized Masterpiece Scrolls in the Museum Collection

-

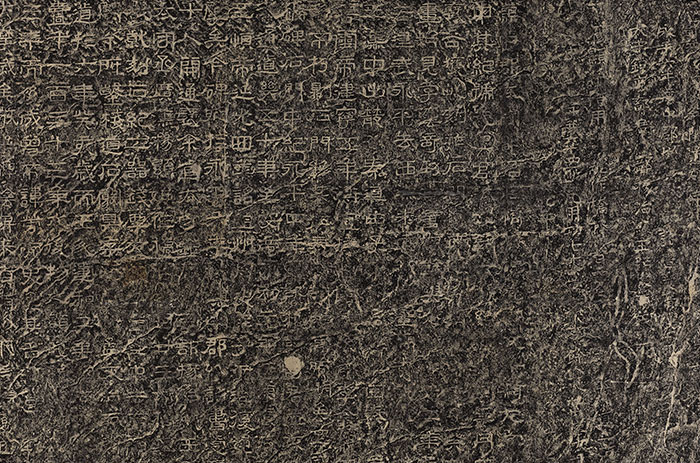

Ink Rubbing of the “Shanhe Weir Reconstruction Stele” Yan Mao, Song dynasty

Yan Mao (style name Chute) is a native of Linchuan (modern-day Jiangxi) during the Southern Song dynasty and an offspring of the famous Northern-Song politician, essayist, and poet Yan Shu (991-1055). Yan Mao’s calligraphy is representative of the clerical script from the Song dynasty. From 1190 to 1194 CE, he served as the Magistrate of Nanzheng in Shaanxi. Among the thirteen local cliff inscriptions situated near the earliest artificial tunnel in China, three are the work of Yan Mao. In this exhibition, “Shanhe Weir Reconstruction Stele”, the biggest among all 104 cliff inscriptions in the Shimen area, was carefully selected by the curation team for display. This stele was engraved in 1194 CE near the entrance of Shimen. The characters carry an open quality and a majestic, awe-inspiring flow.

The Expressive Significance of Brush and Ink : A Guided Journey Through the History of Chinese Calligraphy

-

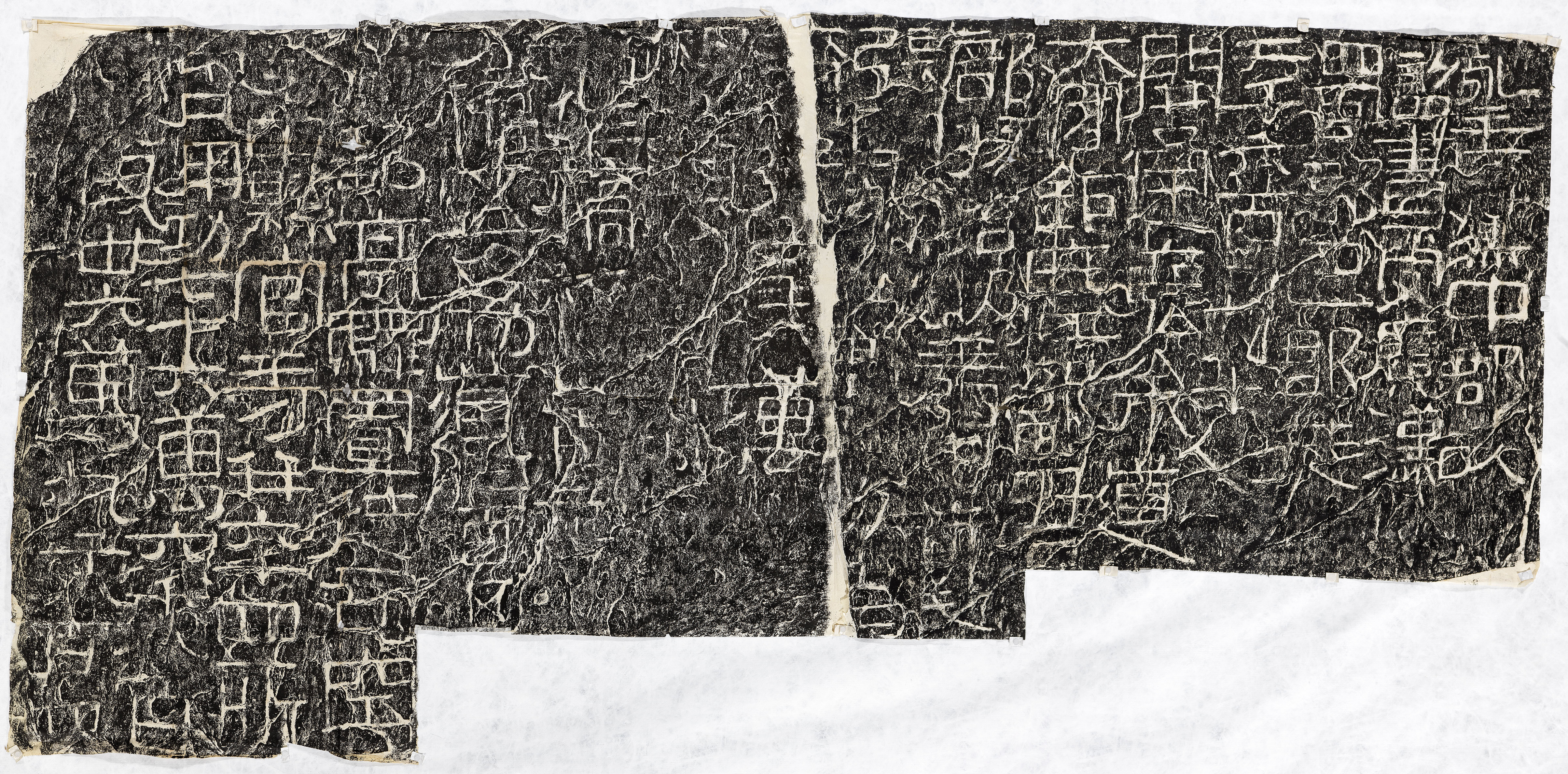

Ink Rubbing of the “Queen Mother Temple at Huishan in Jingzhou Renovation Eulogy”Shangguan Bi, Song dynasty

In 948 CE, Queen Mother Temple at Huishan in Jingzhou was renovated, and Hanlin Academy scholar Tao Gu (904-970) composed a eulogy and wrote the stele text as well as the heading. However, fascinating writer as Tao was, his personality was questioned by many. Thus, after the stele had been erected, the stele text was erased twice in a mere 56 years. The first incident occurred 30 years after the erection of the stele, with the text re-written by Mengying, famed for his seal script. The second incident happened in 1025 CE, as Song-dynasty Councilor Shangguan Bi did not appreciate the calligraphy of Mengying, and re-wrote the text in “jade chopstick seal script”. The work on display this time is the ink rubbing of Shangguan Bi’s work.

-

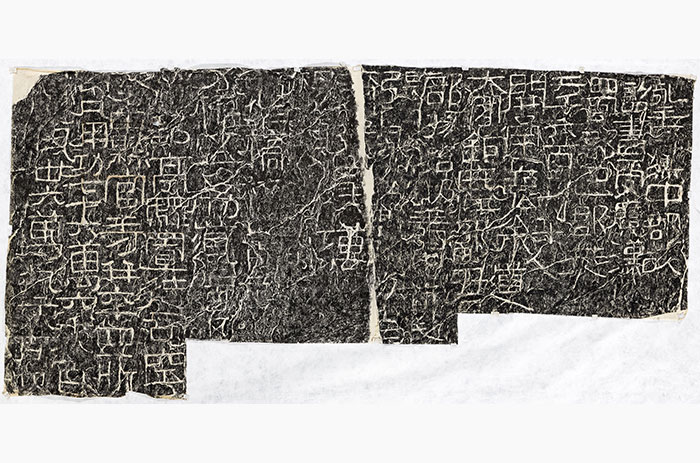

Ink Rubbing of the Inscription “Yan Mao’s Interpretation of Chu Chun Opens the Baoxie Cliff Plankway”Yan Mao, Song dynasty

This ink rubbing was a collection of Tai Chingnung. The full title of the inscription is “Yan Mao’s Interpretation of Chu Chun Opens the Baoxie Cliff Plankway”, but the work is abbreviated as “The Kaitong (which means “opening”) Inscription in Small Font” by many. The original (also known as “The Kaitong Inscription in Big Font”) states that in 66 CE, Chu Chun, the Prefecture Chief of Hanzhong, ordered 2,690 prisoners to open the Baoxie Cliff Plankway. In 1194 CE, the inscription was found by Yan Mao, who engraved his interpretation beside the original inscription after the same style. The work by Yan Mao was later covered in moss, and was re-discovered by Shaanxi Governor Bi Yuan (1730-1797) in the Qing dynasty. From then on, many ink rubbing versions started circulating, but more than 30 characters had already gone missing in “The Kaitong Inscription in Big Font” when compared to Yan Mao’s work.

-

Ink Rubbing of the “Baoxie Cliff Plankway Opening Inscription”Anonymous, Han dynasty

This ink rubbing was a collection of Shu Yunchang (1886-1973), later donated to the National Palace Museum by his wife. The full title of this inscription is “Chu Chun Opens the Baoxie Cliff Plankway”. The work is abbreviated as “The Kaitong (which means “opening”) Inscription in Big Font” by many, and is the earliest (existing) cliff inscription in clerical script from the Eastern Han dynasty. The flow of calligraphy is powerful yet rounded, with a touch of the seal script, creating a plain but majestic style. The characters come in all sizes and appear in various forms. Inscription expert Yang Shoujing (1839-1915) regarded this work as a masterpiece by remarking that “the characters come in all lengths, widths, and sizes, which resemble the natural lines on the rock, making it a unique piece which cannot be modeled after in any generation to come.”

-

Ink Rubbing of the “Shimen Inscription” Wang Yuan, Northern Wei dynasty

The “Shimen Inscription” is a cliff inscription in regular script completed during the Northern Wei dynasty, also known as “Shimen Inscription in Commemoration of Yang Zhi from Taishan to Re-open the Cliff Plankway”. The characters were first written by Qinliang Commander Wang Yuan of Taiyuan, then engraved in 509 CE by engraver Wu Aren. The inscription commemorates how prefectural governor Yang Zhi (458-516) helped re-open the southern part of Baoxie Cliff Plankway, which had been jammed for more than 200 years, under the order of the Emperor Xuanwu, as well as the achievements of other officials who contributed to the project. The “Shimen Inscription” boasts powerfully rounded brushwork with an elegant, smooth quality, making it a unique piece among works from Northern Wei which usually comprise sharp, edged brushwork.

-

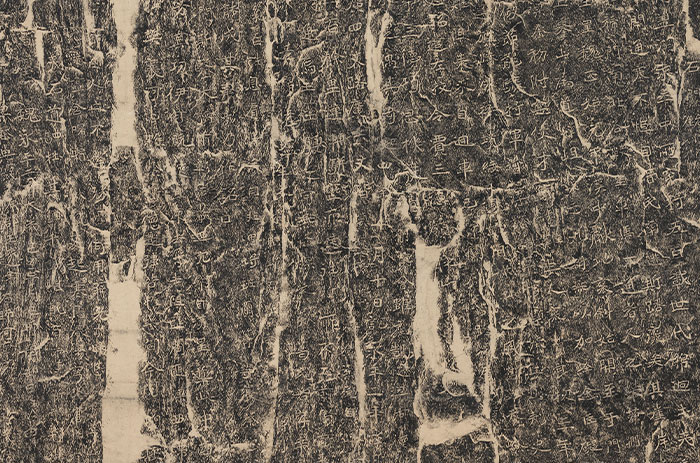

Ink Rubbing of the “Shimen Eulogy” Anonymous, Han dynasty

The original for this rubbing is an engraving made in 148 CE during the Eastern Han dynasty on the cliffs at Shimen (“Stone Gate”) at Baoxie Cliff Plankway (in modern-day Shaanxi). The inscription commemorates the completion and opening of a plankway passage along the Shimen cliffs, in praise of the unswerving official Yang Mengwen, who had petitioned multiple times to have the project done. Thus, the inscription is also known as “Eulogy to Metropolitan Commandant Yang Mengwen”.

This engraving boasts powerfully rounded, straight-forward, and pure brushwork with an open quality of its characters. It is therefore considered representative of the path taken in the more unusual and unrestrained expression of Han-dynasty clerical script. The “Shimen Eulogy”, the Lueyang “Fuge Eulogy” (172 CE), and the Gansu “Xixia Eulogy” (171 CE) are collectively known as the “Three Prominent Eulogies from the Han Dynasty” and have profoundly influenced works in later generations.

-

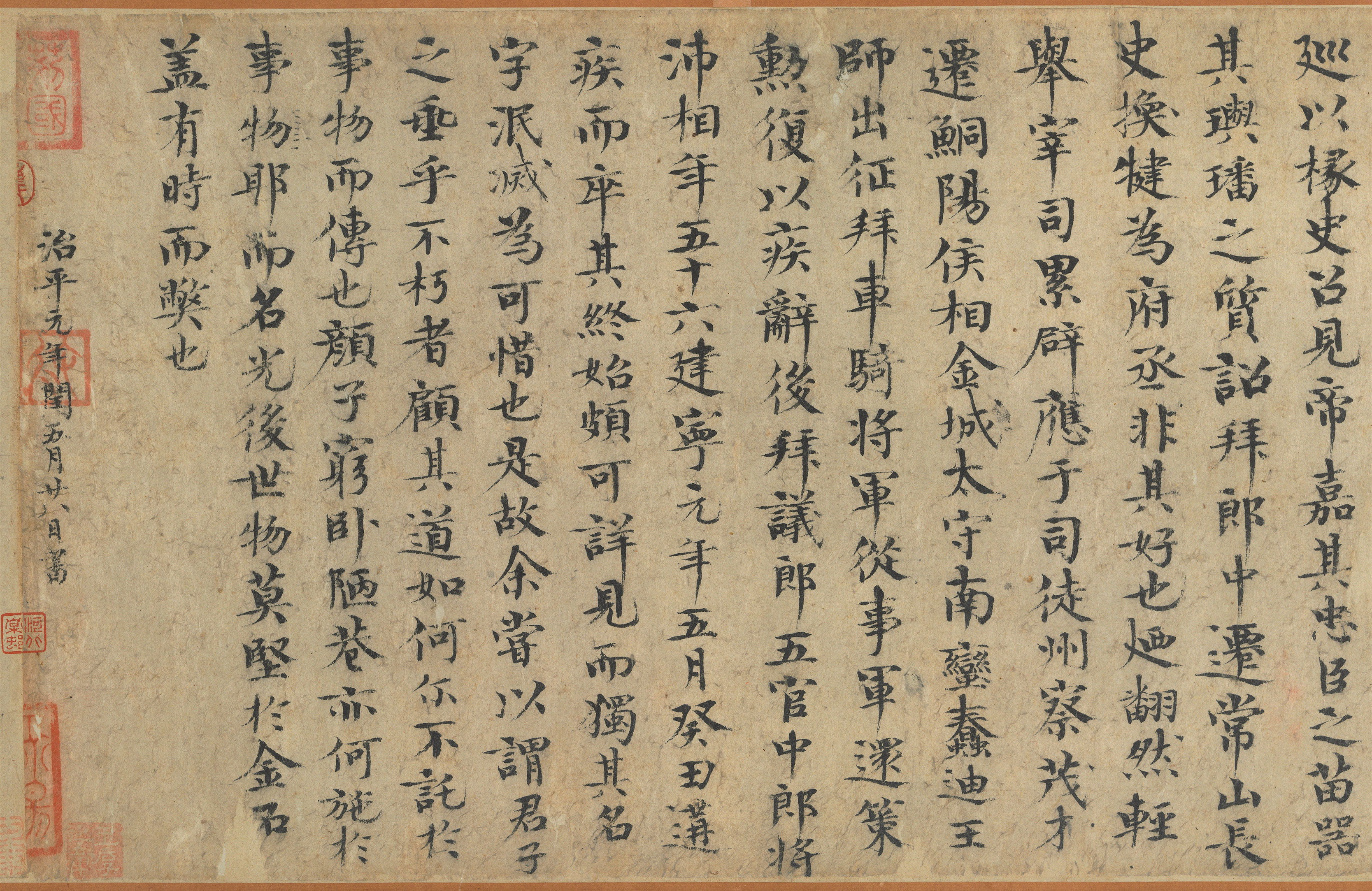

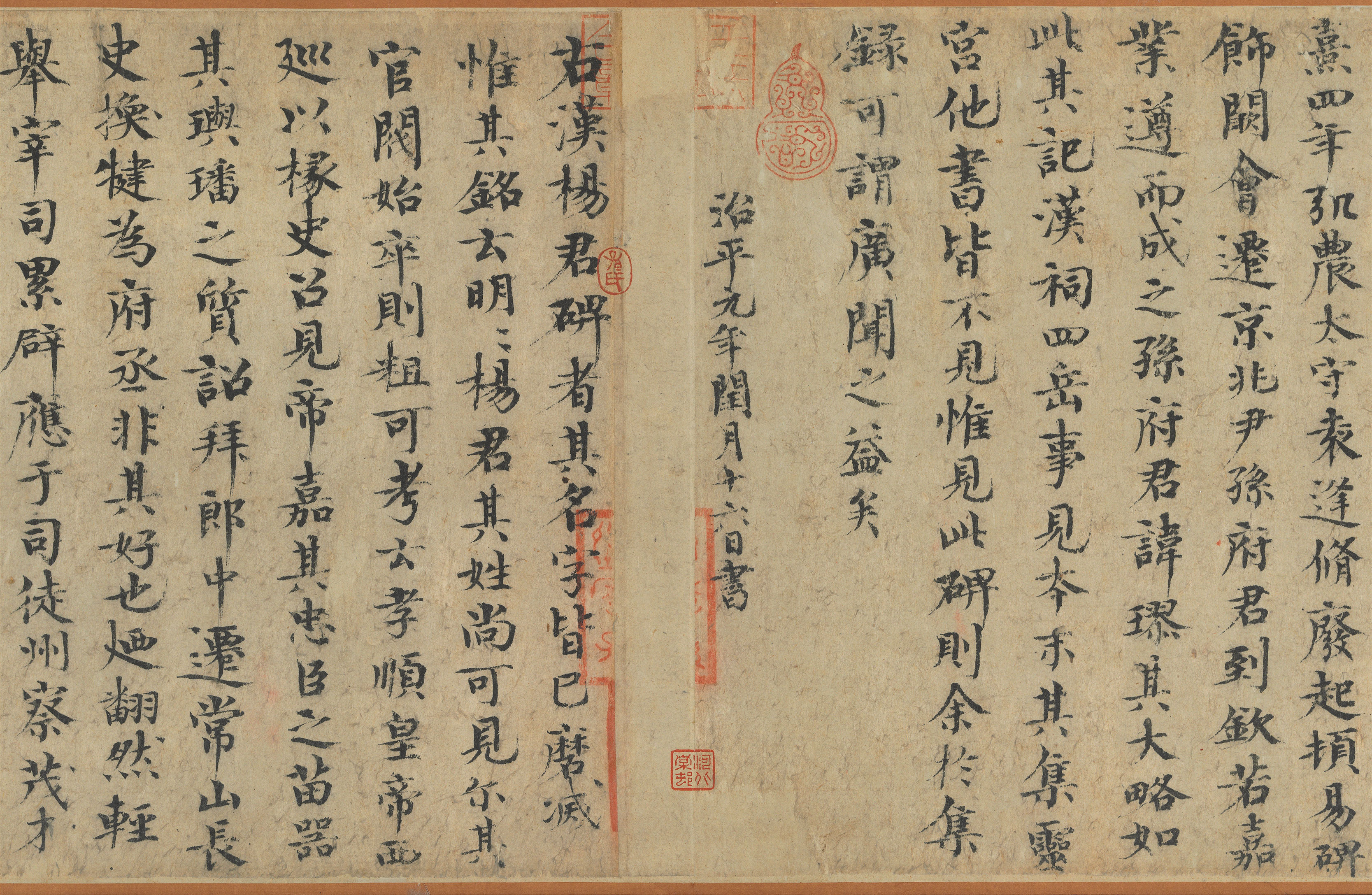

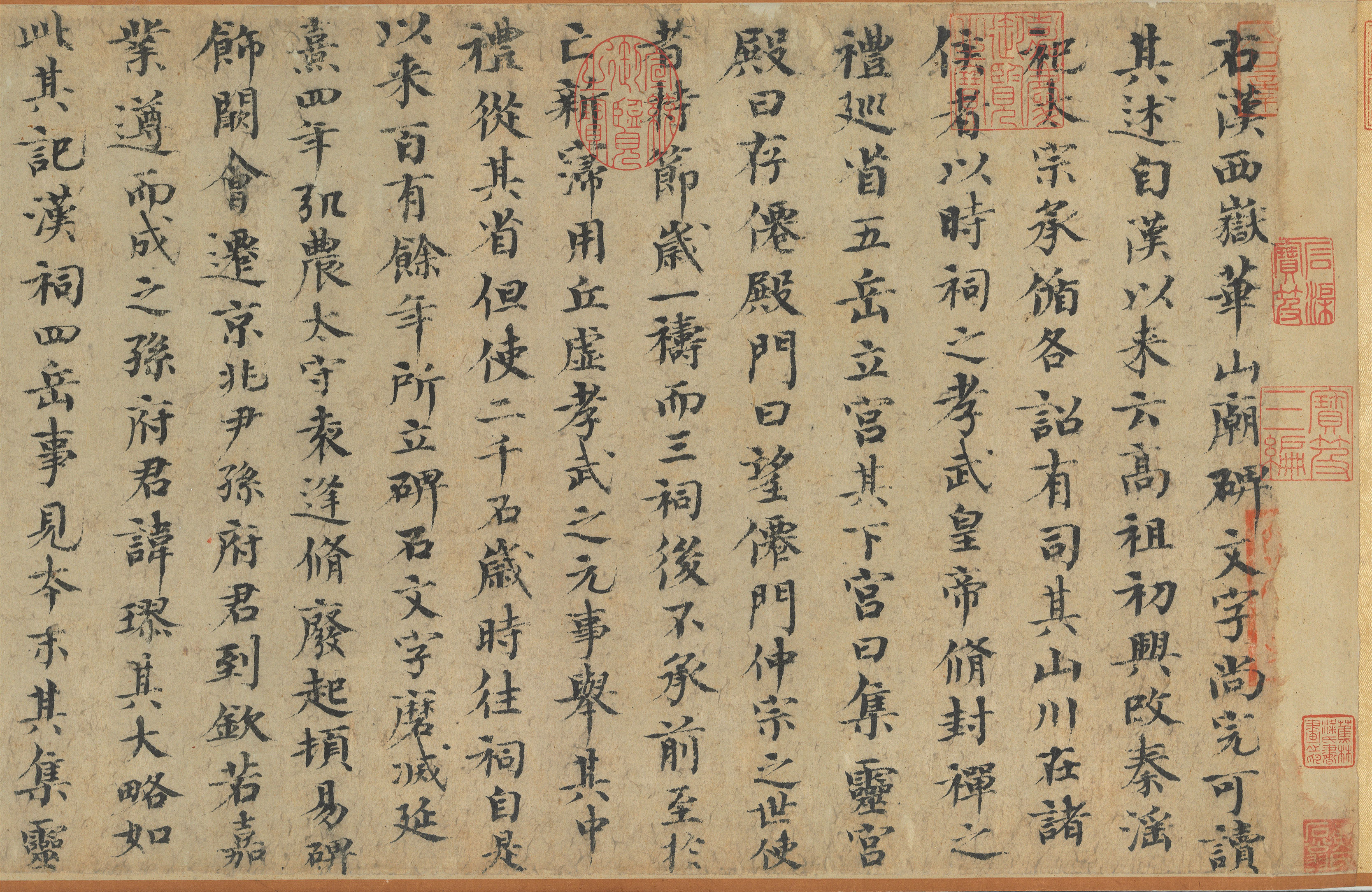

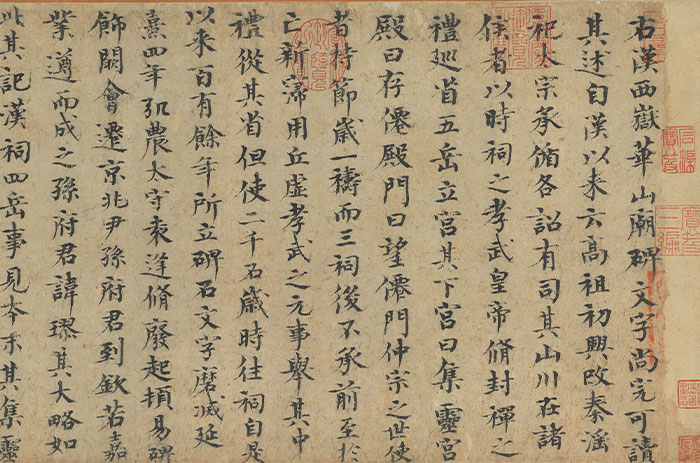

Colophon to Collected Ancient Inscriptions Ouyang Hsiu, Song dynasty

Ouyang Hsiu (1007-1072; style name Yungshu, sobriquet Tsuiweng, and late sobriquet Liu’i Jushi) was a native of Luling (modern-day Ji’an in Jiangxi) during the Song dynasty. This handscroll was done in regular script with restrained and precise characters. In terms of the brushwork, the horizontal strokes are light and the vertical ones are heavier. The distinction between the application and lifting of the brush is pronounced but in a manner akin to a peaceful and introverted movement, demonstrating a pure and untrammeled ambience. The four sections on “Han Dynasty Stele at the Western Peak of Mt. Hua”, “Han Dynasty Stele of Gentleman Yang”, “Biography of the Sage of Tea Lu Yu in the Tang Dynasty”, and “Record of Plants at the Mountain Dwelling of Pingchuan” have been mounted together into a single scroll here. Written in 1064 CE, the contents differ from those in the print edition of Colophons to the Catalogue of Antiquities, indicating that this is probably a manuscript version.

Exhibit List

| Work | Area |

|---|---|

| Ink Rubbing of the “Inscription to Kao Yuanyu Stele” Liu Gongquan, Tang dynasty |

202 |

| Ink Rubbing of the “Preface to the Thousand Character Classic Stele” Huangfu Yen, Song dynasty |

202 |

| Ink Rubbing of the “Shanhe Weir Reconstruction Stele” Yan Mao, Song dynasty |

202 |

| Ink Rubbing of the “Baoxie Cliff Plankway Opening Inscription” Anonymous, Han dynasty |

204 |

| Ink Rubbing of the “Shimen Eulogy” Anonymous, Han dynasty |

204 |

| Ink Rubbing of the “Shimen Inscription” Wang Yuan, Northern Wei dynasty |

204 |

| Preface to Zhang Zhongxun’s Copy of Lives of Eminent Buddhist Monks Meng Ying, Song dynasty |

204 |

| Ink Rubbing of the “Queen Mother Temple at Huishan in Jingzhou Renovation Eulogy” Shangguan Bi, Song dynasty |

204 |

| Colophon to Collected Ancient Inscriptions Ouyang Hsiu, Song dynasty |

204 |

| Ink Rubbing of the Inscription “Yan Mao’s Interpretation of Chu Chun Opens the Baoxie Cliff Plankway” Yan Mao, Song dynasty |

204 |

| Poems Shen Shihxing, Ming dynasty |

204 |

| Four Gains Essay in Regular Script The Qianlong Emperor, Qing dynasty |

206 |

| “Longevity” Blossoms Xia Zonglu, Qing dynasty |

206 |

| Heart Sutra in Official Script Li Shu-tong, Republican era |

206 |