How to Paint Caochong?

Traditional caochong paintings can be divided into two categories: one method is to outline the insects and plants in elaborate details, then filling in corresponding colours cautiously. This 'gongbi (meticulously-illustrated)' caochong painting has an explicit quality as photography that mesmerizingly demonstrates the magnificent features of the subject. The other method is to apply expressive strokes; the varied widths and dynamic of lines collaborate with the subtle blending of ink and colours, which captures the vigorous activities of insects and small creatures among the verdure. The latter is also known as the 'boneless' method; the spontaneous use of brush-stokes and colouration portrays the liveliness of insects to the finest. Painters usually incorporate these methods in different proportions to achieve the desired result that expresses varied charms. Among all the exhibits, which one is your favourite depiction?

'gongbi' vs. 'boneless'

The 'gongbi (meticulously-illustrated)' paintings focus on the precision and details that give the subject a distinguish outline; on the contrary, the 'boneless' artworks emphasize the natural expressions that capture the silhouette with colour blocks. Different painters will adjust the cooperating use of 'gongbi' and 'boneless' methods based on their needs and preferences.

Can you tell from the exhibits which parts are applied with 'gongbi' or 'boneless' painting methods?

Does 'caochong painting' require physical observation?

The painters have to observe nature closely before doing caochong painting; it is the only way to capture the appearances and postures. Nonetheless, the drawings of former painters will most certainly become references for later generations.

However, regardless of how meticulously the insects were portrayed, it does not necessarily qualify as a 'caochong painting'. An example is the teaching charts; the accuracy and details elaborate on the figure and physical composition to students; instead, the caochong paintings often deliver the tranquil vibe of gazing at tiny things, even celebrating the liveliness that blooms in nature.

- Insects and a Cabbage Plant

- Xu Di (fl. 11th c.), Song dynasty

This painting mounted as an album leaf depicts a subject common in daily life--a cabbage plant with a dragonfly, grasshopper, and butterfly all in an apparently simple composition. However, the overly symmetrical arrangement appears a bit too static, suggesting the painting may have been cropped from a larger work. The motifs in the painting appear at first glance to be fine and precisely rendered, but some of the structural details are actually problematic, such as the imprecise position of the dragonfly's wings. Furthermore, the yellowing cabbage leaf lying on the ground is delicately colored, but its structural relationship is not clearly defined and has a somewhat unnatural quality. These features differ from the style of precise rendering seen in Southern Song (1127-1279) painting, suggesting more of the late Southern Song or Yuan dynasty date.

Open Data Download

- Plants and Butterflies

- Sun Long (15th c.), Ming dynasty

This painting is the second leaf of the album "Sketches from Life" painted by Sun Long in the Ming dynasty, and the lower right corner has the painter's seal mark that reads'Sun Long tushu'. Sun had served in the palace in the 15th century and excelled at the technique of ink and colour washes. He used silk pre-coated with alum glue as canvas, contributing to the moist brushstrokes without blurring that leaving his desired shapes; the outcome was the delightful vividness formed by ink and colours.

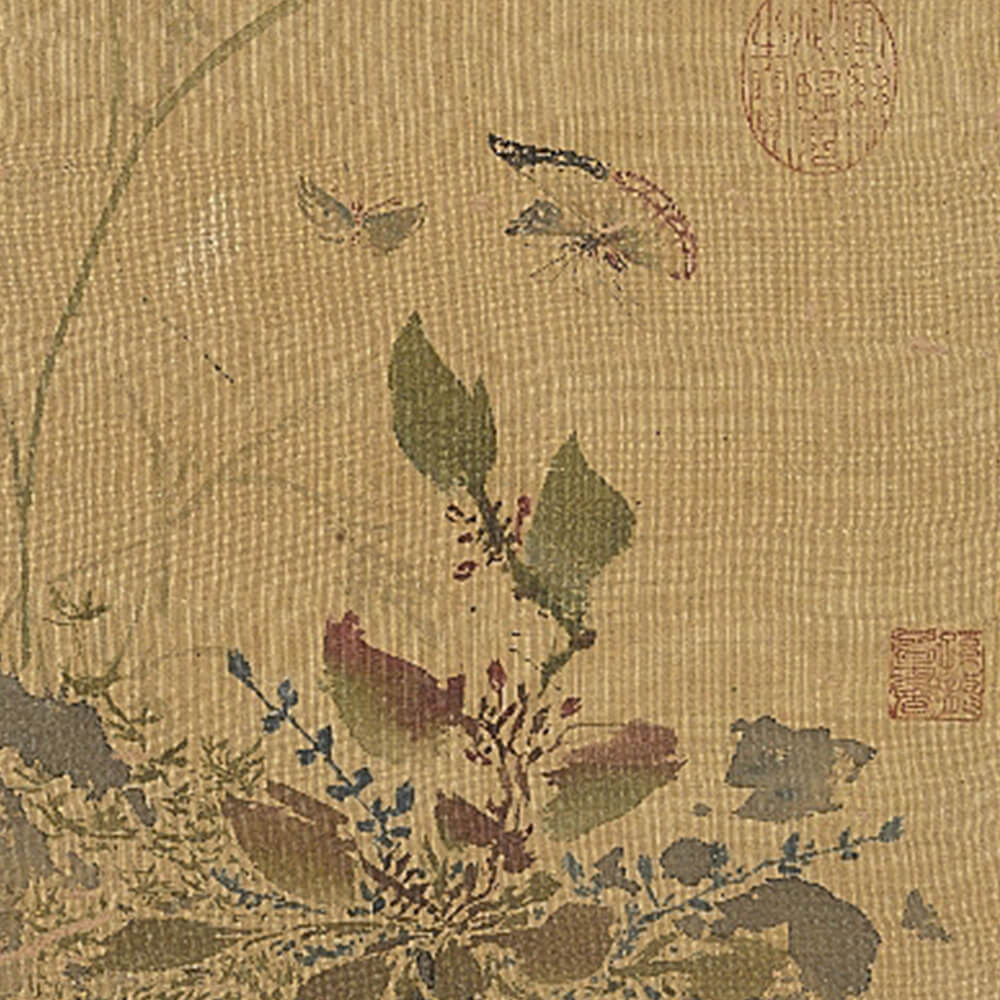

- Insects and Abundant Grain

- Wu Bing (fl. 12th c.), Song dynasty

Wu Ping, a native of Kiangsu province, was a Southern Sung court artist during the Shao-hsi era (1190-1194) and served as a Painter-in-Attendance. This leaf from the album "Collected Gems of Famous Paintings" shows two rice plants with graceful leaves bearing heavy shoots of grain and drooping under their weight. Without any further background scenery and interspersed among them are two dainty and beautiful butterflies as well as a horse fly. A dragonfly is also shown resting one of the blades of rice. The plants and insects were all rendered with exceptional detail and naturalism. Since the top and left margins of the work appear to end abruptly, this painting may have once been part of a larger one that was trimmed (perhaps due to damage) to create the present form.

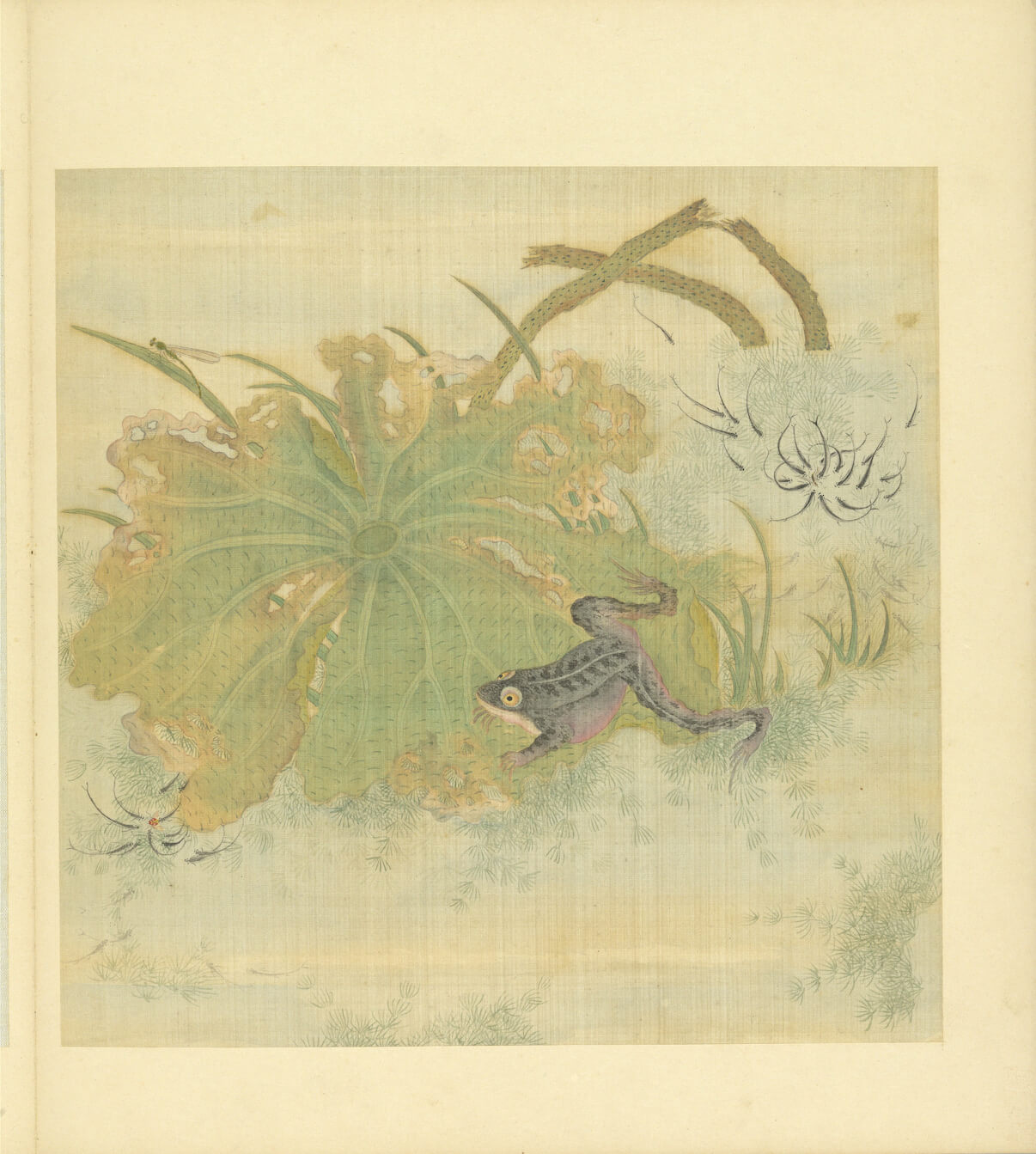

- A Frog and Shoal of Fish Amidst Lotus and Green Algae

- A-er-bai, Qing dynasty (1644-1911)

One damselfly rests upon the lotus leaf, and an adorable frog with silly look pauses in a peaceful position. Flying bugs fall into the water filled with aquatic plants beneath the lotus leaf, and their struggles have caused a stir of tumult among the fish.

The painter used 'gongbi' method to depict damselfly and frog in a static state; the finessed outline came first, followed by layers of colour washes. However, the spontaneous expression took on a few curves and added simple heads and tails, splashed on fins and eyes to present the exhilarating fish.

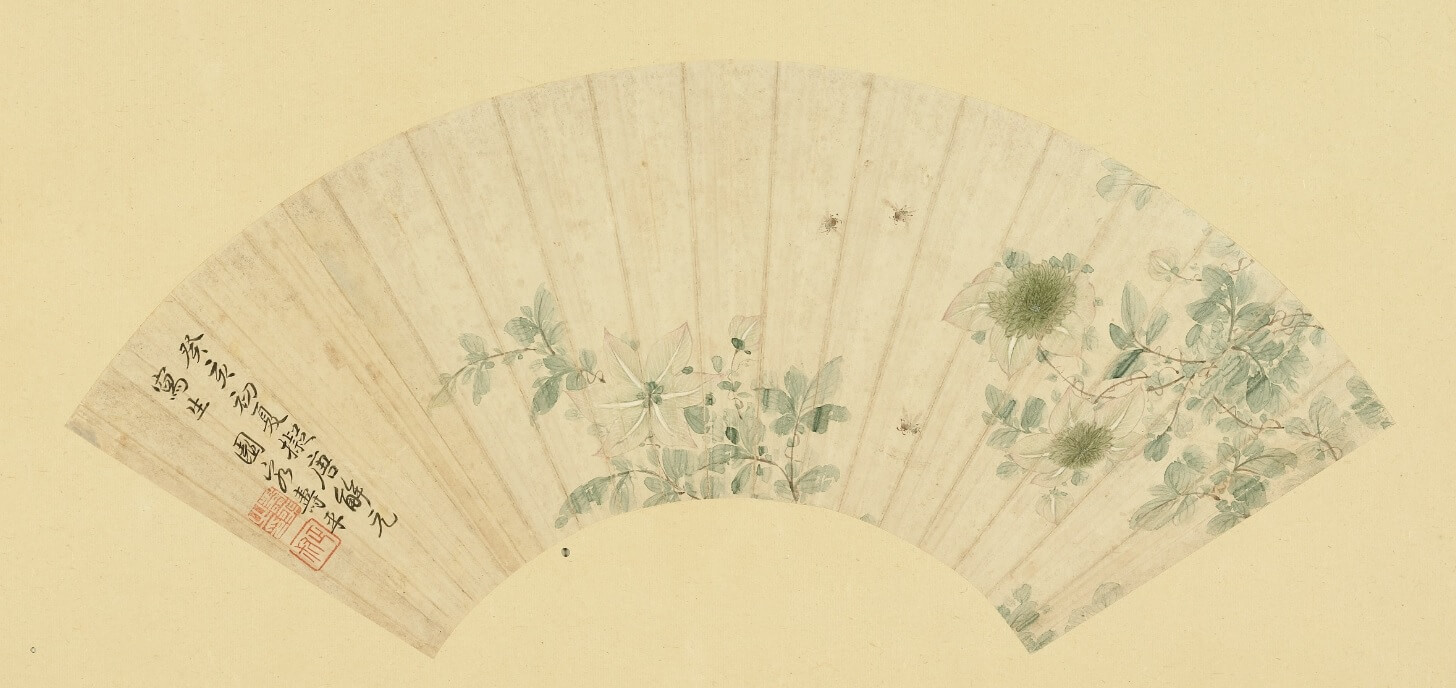

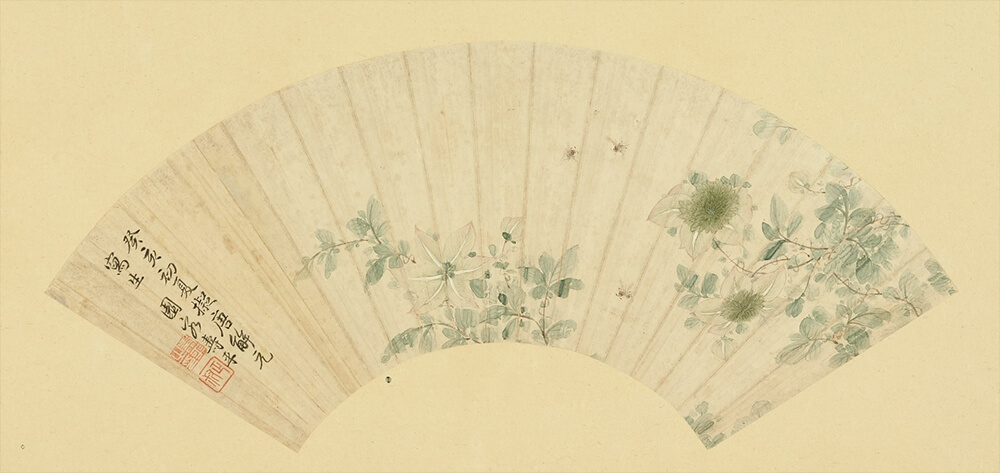

- Passion Flowers

- Yun Shouping (1633-1690), Qing dynasty

Yun Shouping was a renowned painter of flowers. Yun referred to ancient painting techniques on flowers and concentrated on the 'boneless' method, which focuses on colour shading with a moist surface to depict the form of the subjects instead of relying on distinct outlines. The painter used calligraphic lines to express the bending hind legs of the three bees; the clever blend of ink by brush tips demonstrated the blurry image of flapping wings.

- Insects and Autumn Plants

- Li Di (active 12nd c.), Song dynasty

The mantis raises both forelegs and turns to stare at the chafer flying in the air, showing the possible pity of losing prey. The most exciting detail is the delicate change of colours. The shift of tones on the forelegs in yellow-brown, light yellow and deep green tells the detailed shape. The finesse and beauty of the painted subject make it almost possible to ignore that it is a life and death moment of hunting and escaping, but to indulge ourselves in the sensual charms presented by the plants and insects in the painting.

- The Face of Autumn and a Decorative Rock

- Huang Quan (fl. 903-965), Five Dynasties period

The flowers in violet by the stone swing along the wind while a praying mantis stands on the stem staring at a flying butterfly. A locust (acrida) rests on the withered autumn grass, and beetles move along the trail with red berries hiding under the dry grass. The painting has an abundant visual and vivid liveliness, but somehow with a rush finish, showing from the overlapping outlines of the drying grass and many colours in one simple layer. This painting is attributed to the master of flower-and-bird painting, Huang Quan. However, it is most likely by a talented caochong painter from the Ming dynasty.

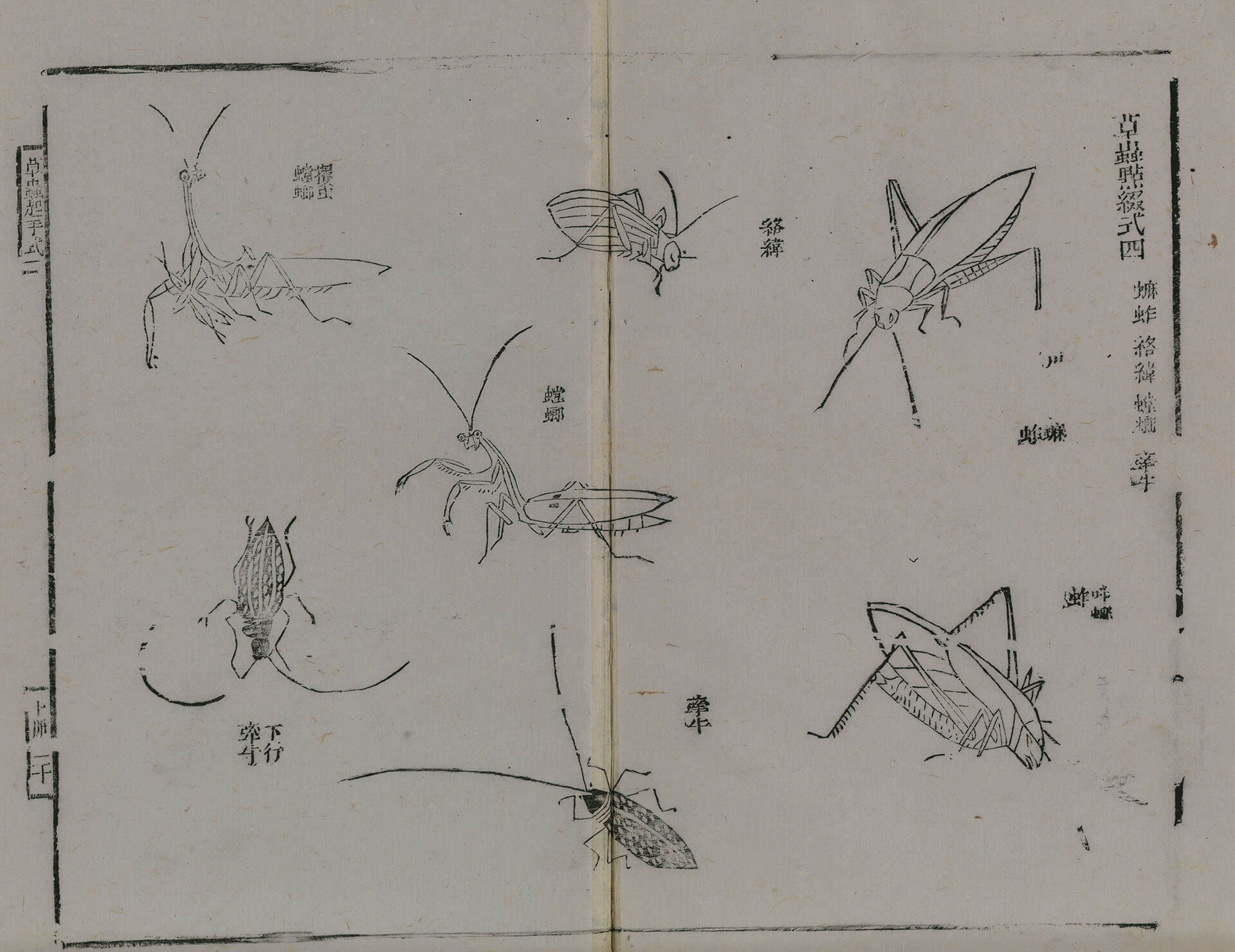

- The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting

- Wang Gai, Qing dynasty (1644-1911)

Do painters require close observations of the insects to paint caochong well? In fact, painters can take references from other painters' works or study all sorts of insects documented in the 'manual of paintings'.

The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting was the famous catalogue edited in the early Qing dynasty, in which is a chapter dedicated to teaching how to paint 'caochong and flowers'. The manual allows painters to copy the instructions and paint similar images without actually seeing the insects.

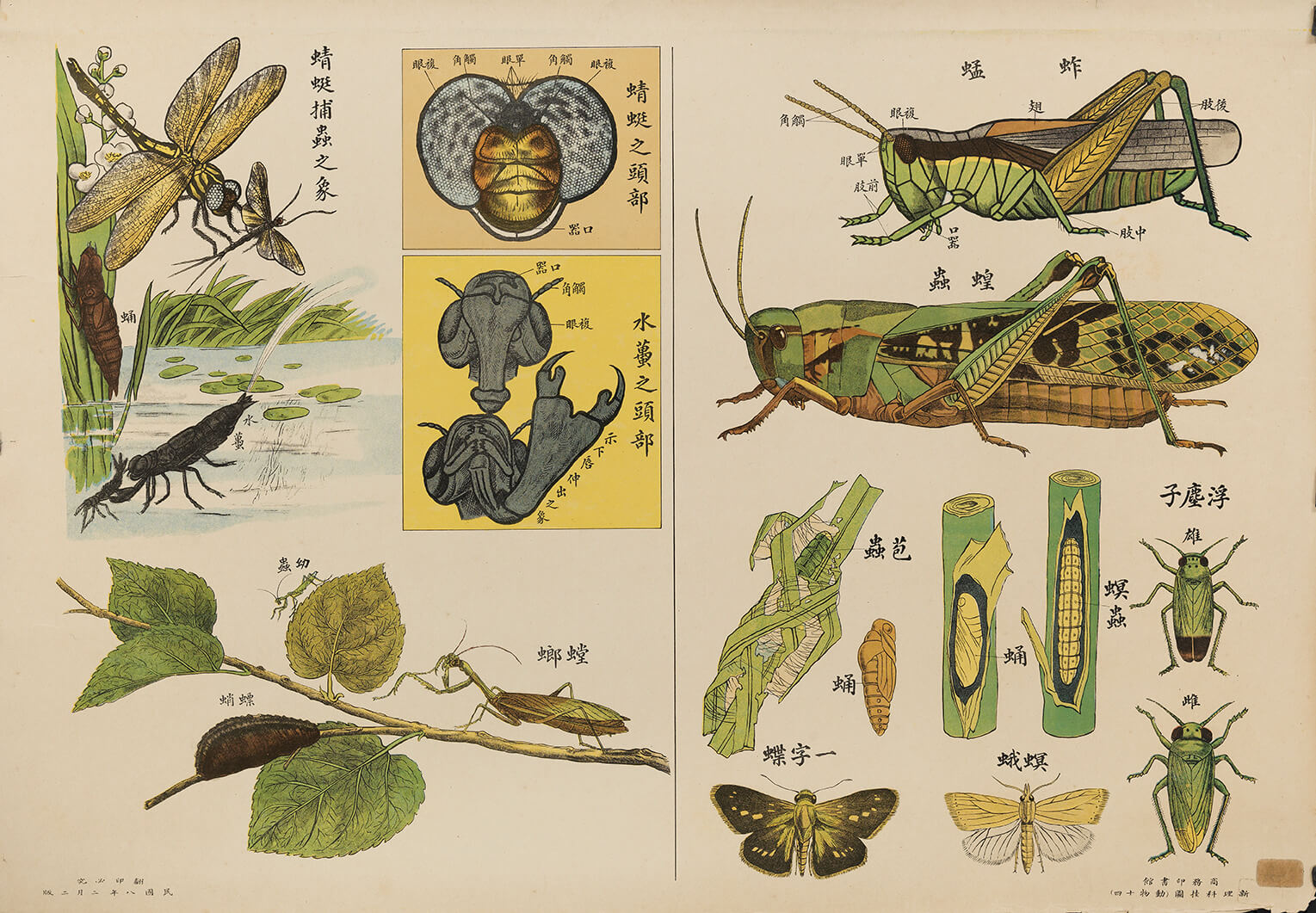

- Illustrations of the Sciences

- Republic period

This rare Illustration of Sciences was the edition printed by the Commercial Press in the 8th year of the Republic period (1919), which might serve the purpose of a teaching tool in the Palace. These scientific charts also include images of insects, which introduce the body parts and organs of insects and present the forms of each stage from egg to imago. The focus sits on the introduction purpose instead of the vivid portrayal in the 'caochong paintings'.

- Lycium Berries and a Quail

- Cui Que (fl. 11th c.), Song dynasty

Ts'ui Ch'ueh, a native of Anhwei province, served at the Northern Sung court of Emperor Shen-tsung (r. 1067-1085) as a painter. He and his elder brother Ts'ui Po both excelled at and achieved fame in bird-and-flower painting. This leaf from the album "Collected Works of T'ang, Sung, and Yuan"; bears neither seal nor signature of the artist, so further study is necessary to determine if it is indeed by Ts'ui. However, in the upper right corner is the partial impression of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) "Tu-sheng shu-hua chih yin"; collection seal, indicating it must date no later than the Sung. This work focuses on a quail and a mole cricket in a rustic setting. They were not outlined with a brush but instead were done directly with washes of ink for a simple yet elegant touch. This so-called "leaving ink"; method of painting is quite rare in Sung art.