The Garden as Microcosm of the Qing Empire

As the second center of political power of the Qing Empire, the architecture and layout of the Chengde Summer Resort were designed to resemble the Forbidden City in Beijing. On the other hand, the gardens were set to symbolize the empire as a unitary multi-ethnic state by incorporating replicas of scenic spots and flora from across the empire.

The resort and its outlying architectural complexes can be roughly divided into the following: palaces, lakes, plains, and temples. The palaces, comprising the emperor's office, living quarters, and ceremonial venues, were built on the same layout as the Forbidden City in Beijing, with the front area devoted to state affairs and the rear rooms used as bedchambers. The lakes were recreational spaces for the emperor. Some pavilions and pagodas had a style unique to the resort, while others were inspired by scenic spots in the Jiangnan region. The flora in this area consisted of plants native to the northern regions or transplanted from the Chinese heartland. The plains area centered around the Ten Thousand Tree Garden (Wanshuyuan), where Qing emperors would have a massive yurt erected to receive Mongolian noblemen and foreign envoys, making this place an important diplomatic venue for the empire. Surrounding the resort were the Eight Outer Temples (Waibamiao), or Chinese- and Tibetan-style temples built during the Kangxi and Qianlong reigns to mark important occasions. These temples are testament to the Qing Empire's use of religious policy to court Mongolian and Tibetan leaders.

The construction and design of the summer resort made it a veritable microcosm of the Qing Empire, reflecting its mode of rule, cultural hybridity, forms of diplomacy, military strategy and deployment, and religious policy. The archives and paintings in the Museum collection give a glimpse into this small universe.

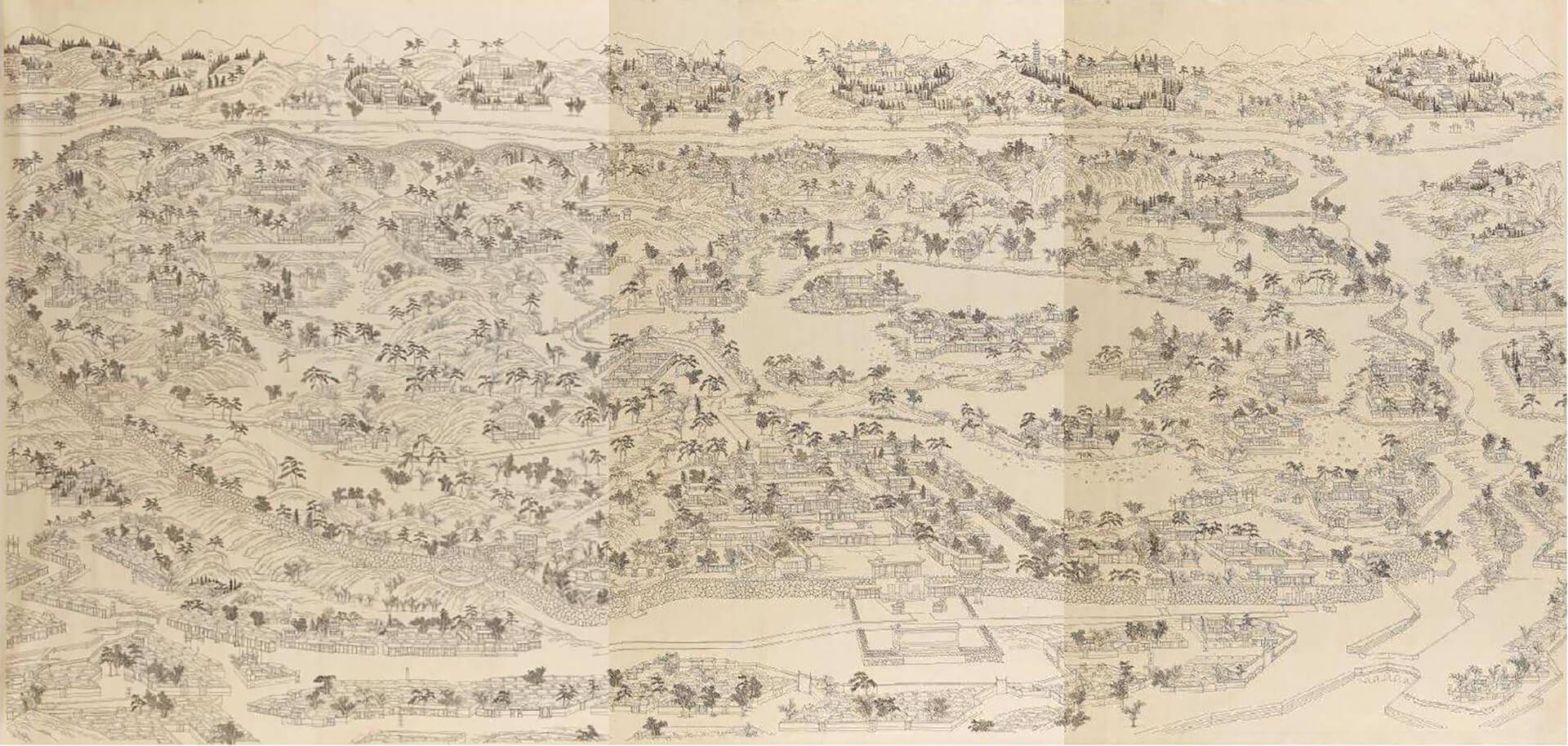

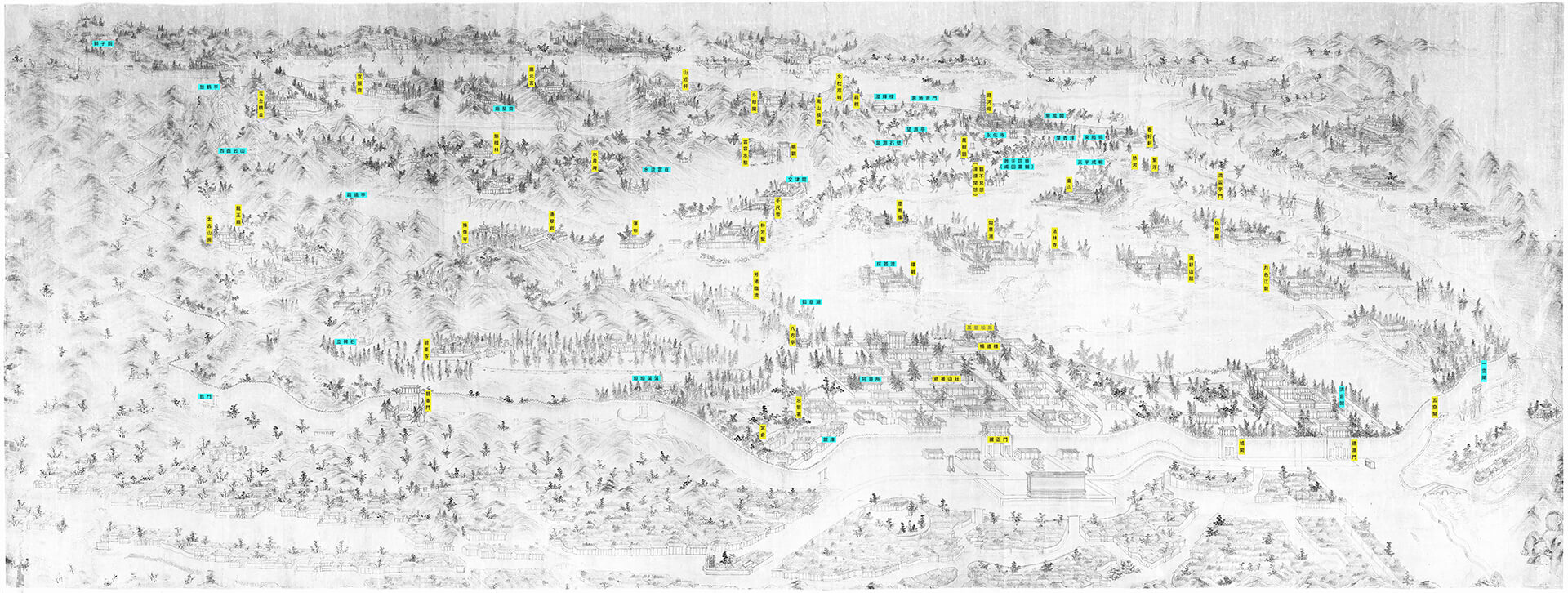

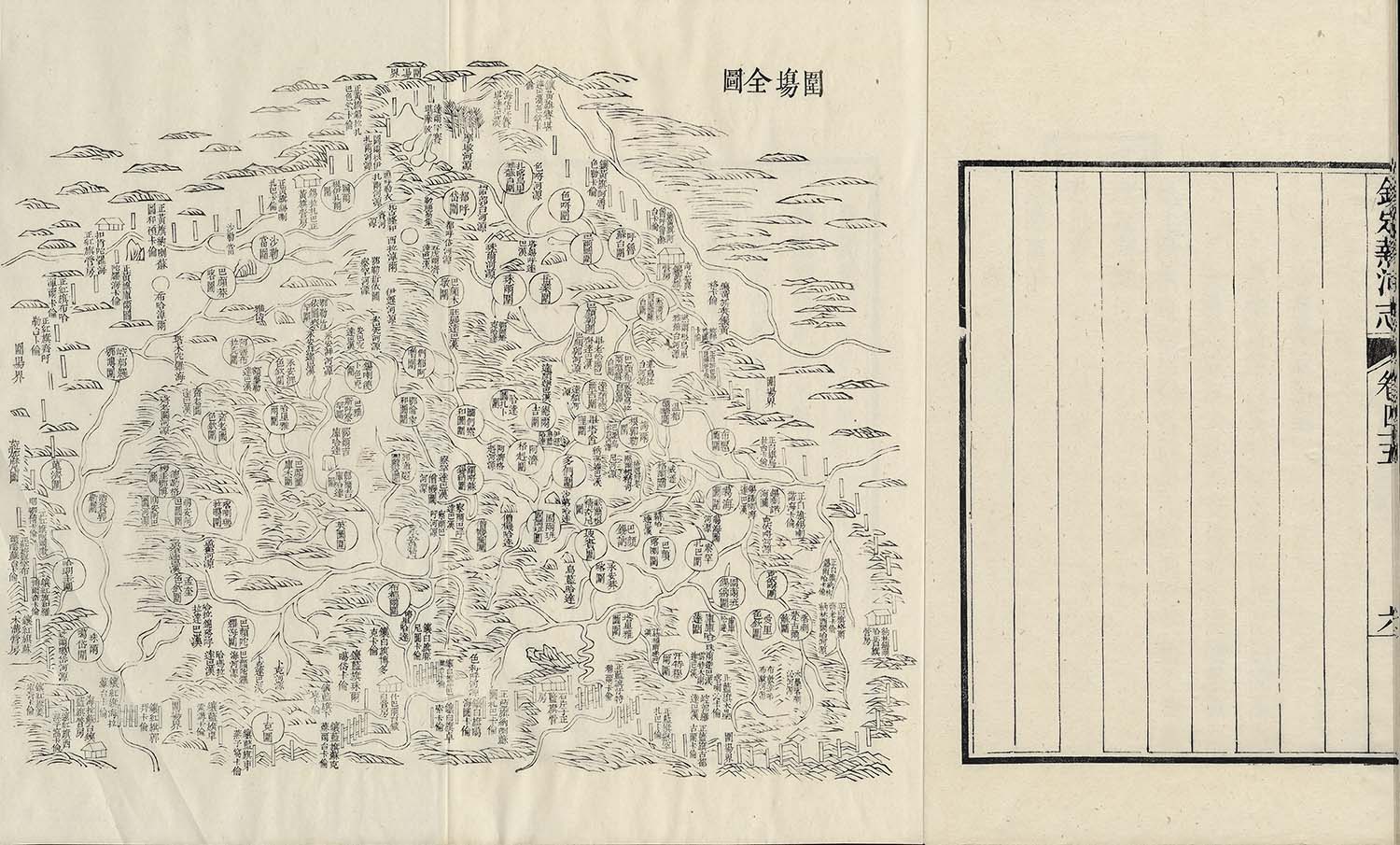

- Illustration of the Summer Resort in Jehol

- Ink on paper

- Qing Dynasty

Judging from the names noted for the various buildings and scenic areas, the painting was created during the late Qianlong era. The bird's-eye view of the painting puts the northern orientation at the top, southern orientation at the bottom, western orientation at the left and eastern orientation at the right. The painting shows the Summer Resort and surrounding areas that are important, including the palace area, lake area, plains area, and the temple and hill area. Overall, 120 palace buildings, terraces and landscape, temples and altars, government offices and dorms, and water conservancy facilities are shown, depicting the form and style of the Summer Resort and associated buildings during the height of the Qing dynasty. The painting also reflects how the Beijing palace area is at the core of the empire, surrounded by lakes and rivers in the south, grassy plains in the northwest, the mountains in the northeast.

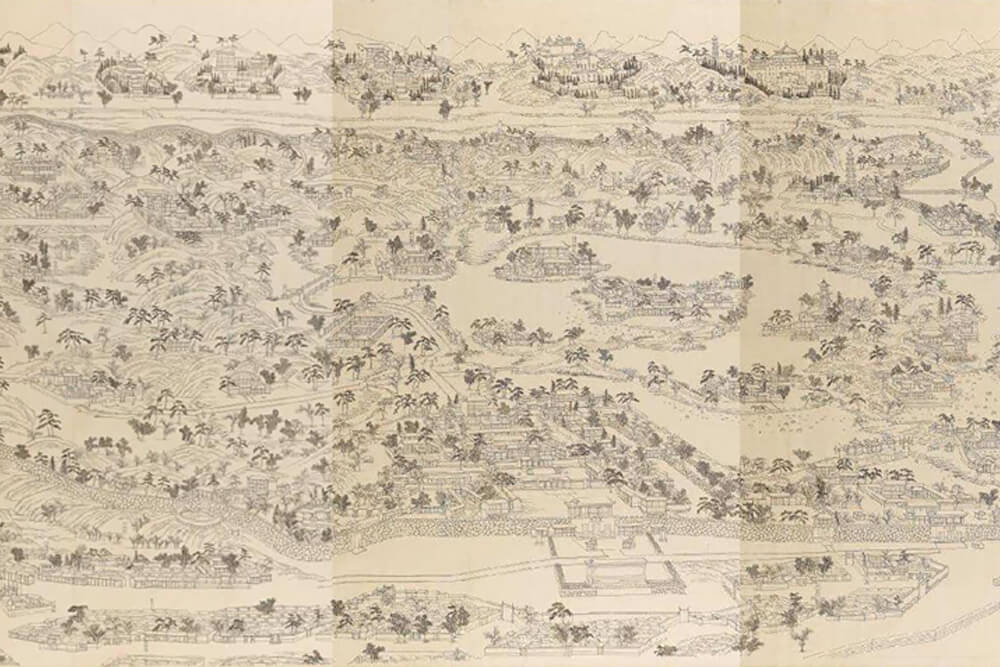

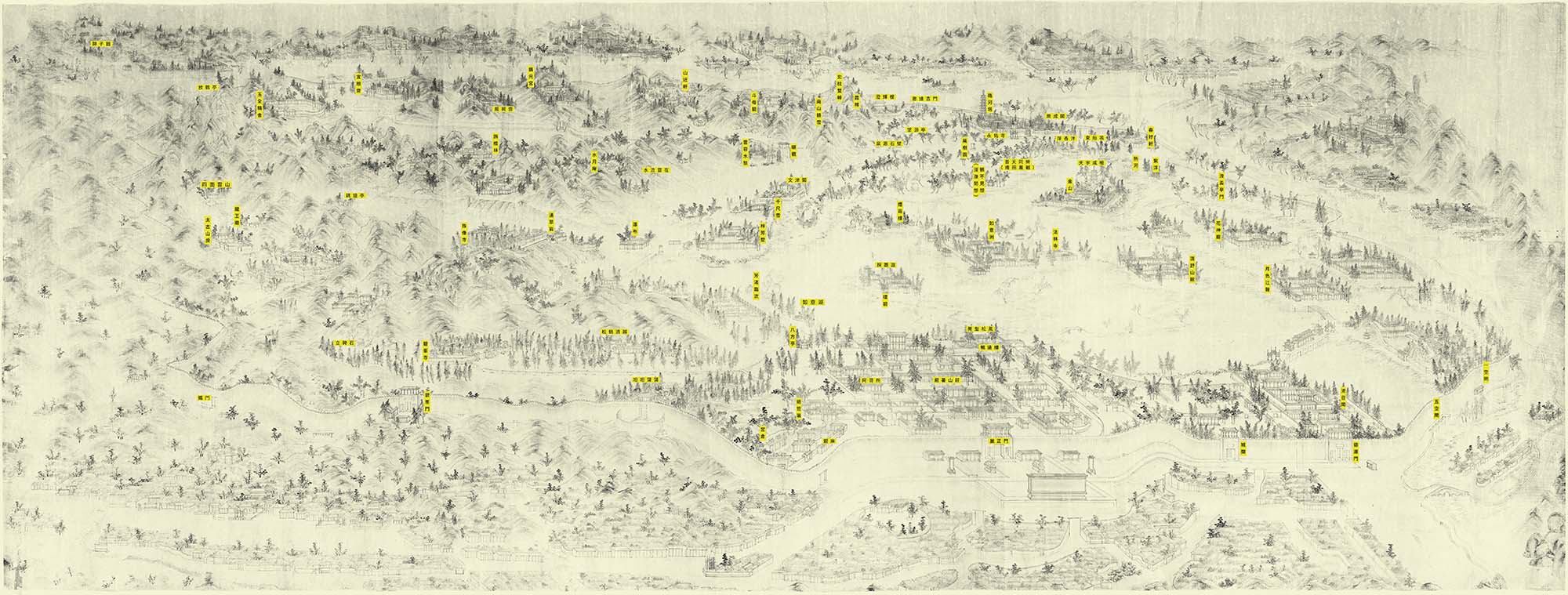

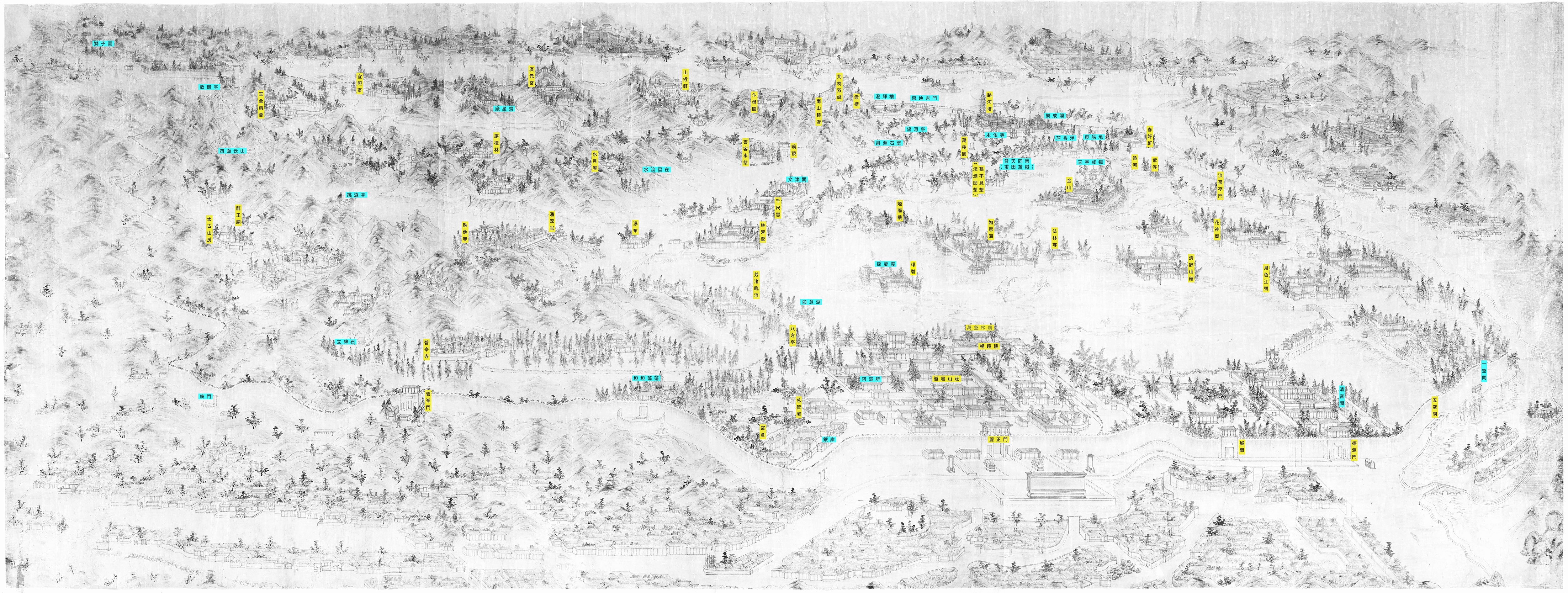

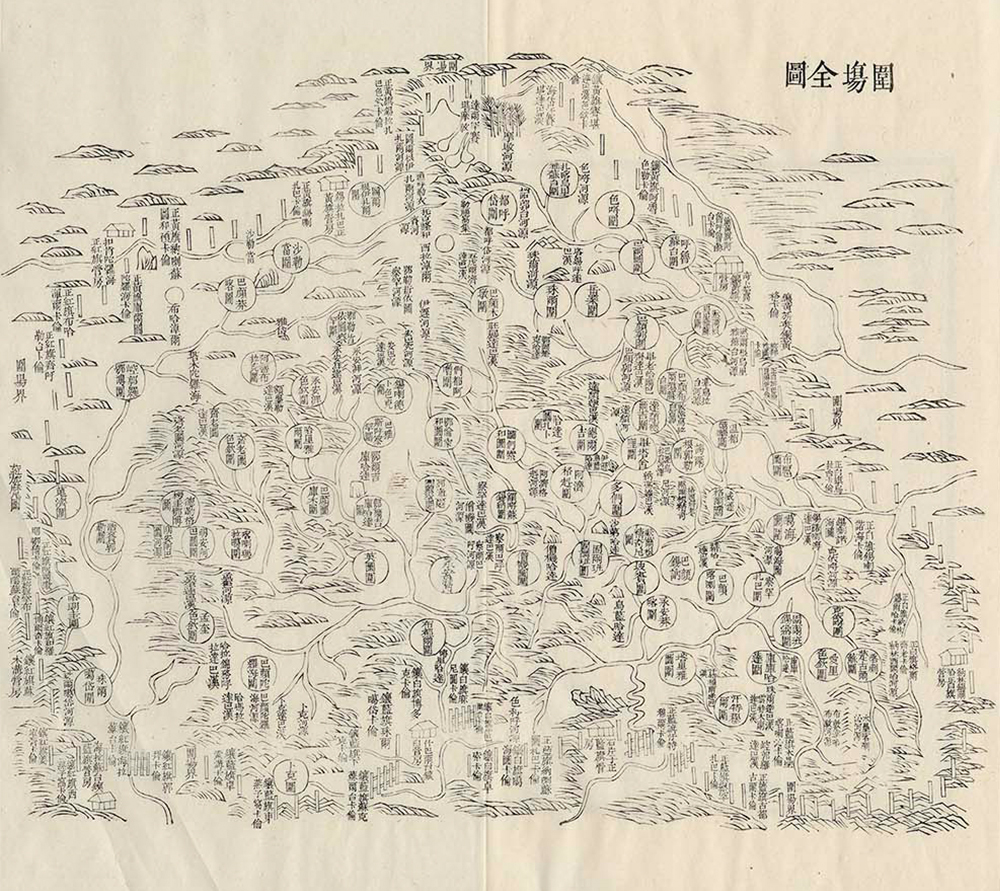

- Illustration of the Summer Resort in Jehol

- Ink and color on paper

- Qing Dynasty

The author of "Illustration of the Summer Resort in Jehol," housed in the National Palace Museum, remains unknown. However, judging from the names of the various buildings and scenic areas, one can deduce that the painting was created by a court painter during the late Qianlong era. The bird's-eye view of the painting puts the southern orientation at the top, northern orientation at the bottom, eastern orientation at the left, and western orientation at the right, and the painting shows a full view of the Summer Resort and its surrounding temples. A closer look at the painting reveals the painters' careless painting techniques and inelegant brushwork. Also, a few of the scenic spots or buildings have spelling errors. An actual count shows that there are 73 buildings and scenic spots with names in the painting; those with names are all inside the resort, whereas those without names are outside the resort and in the mountain temple areas. Despite the painting being a relatively careless work, it was created during the late Qianlong period, a time when the resort had just undergone an expansion. Thus, the painting serves as an important reference for people to understand the history of the resort.

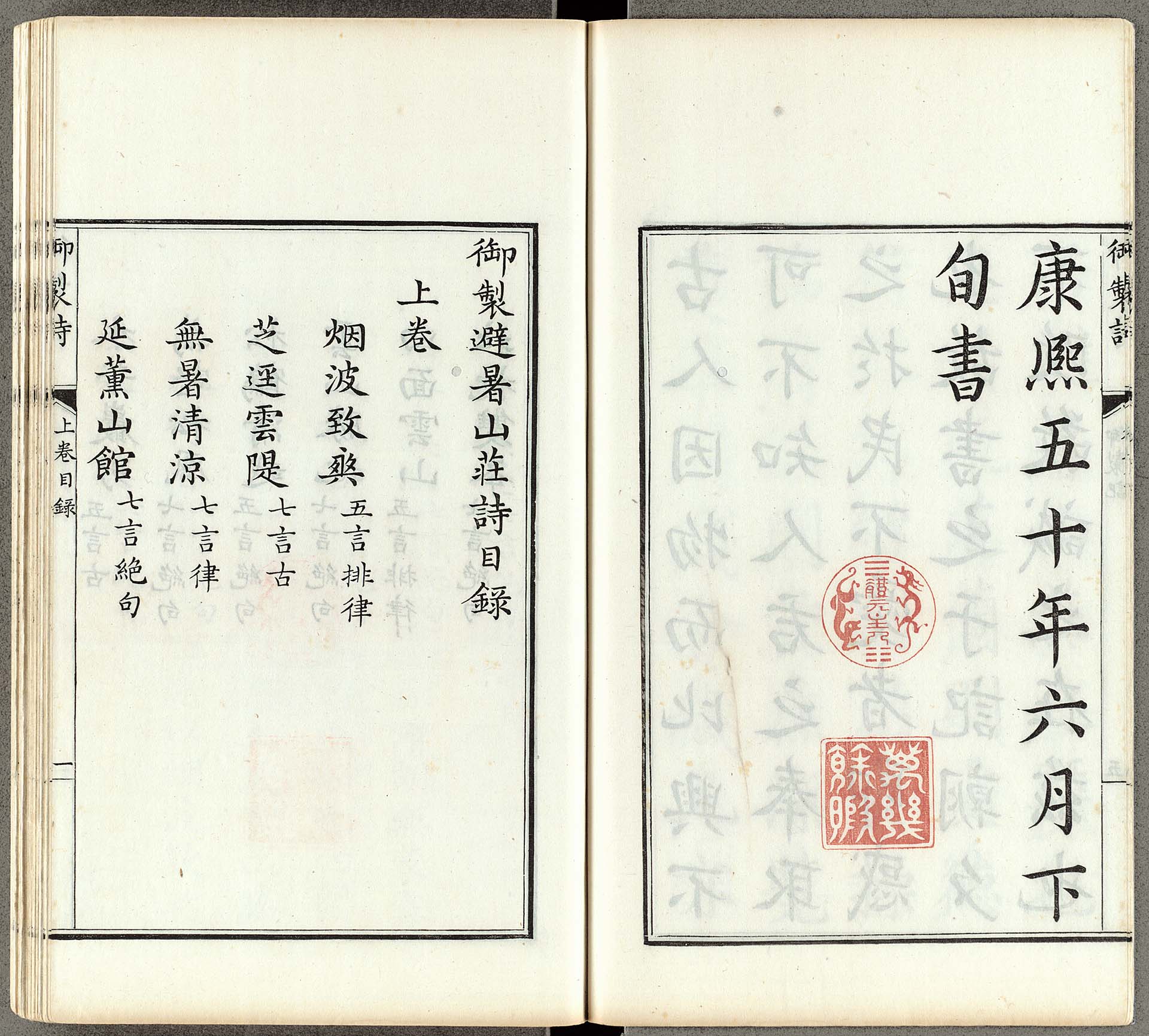

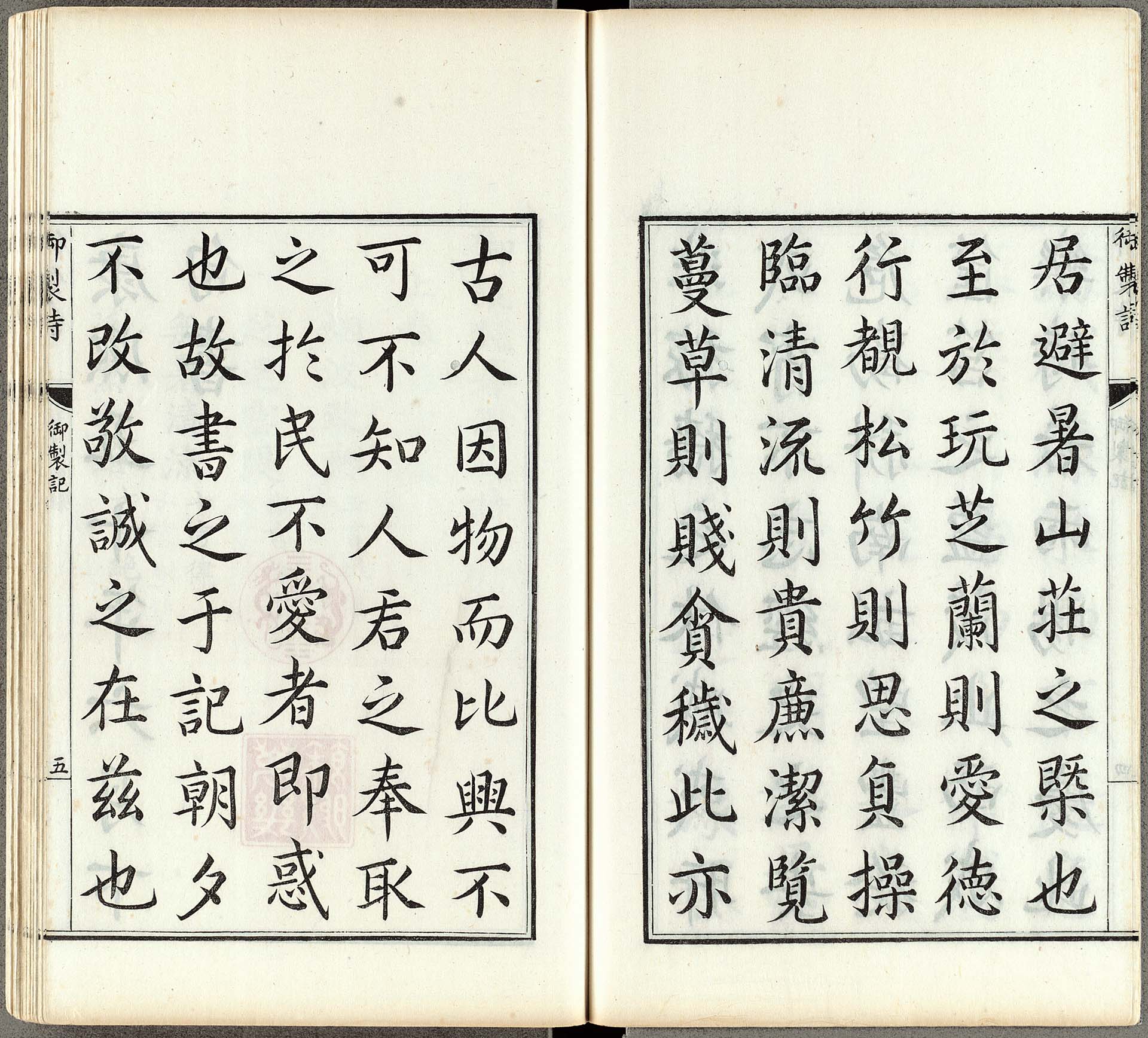

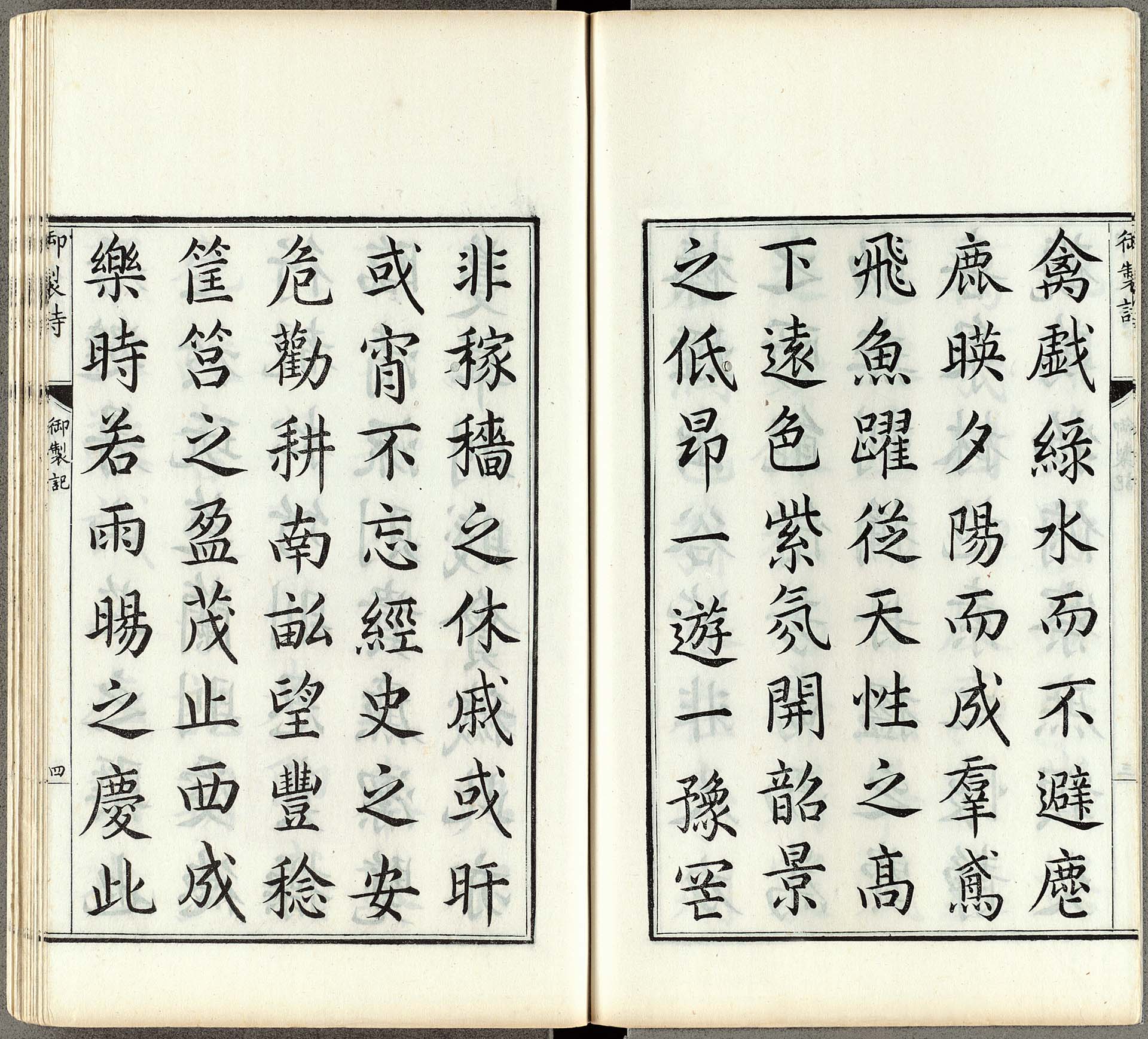

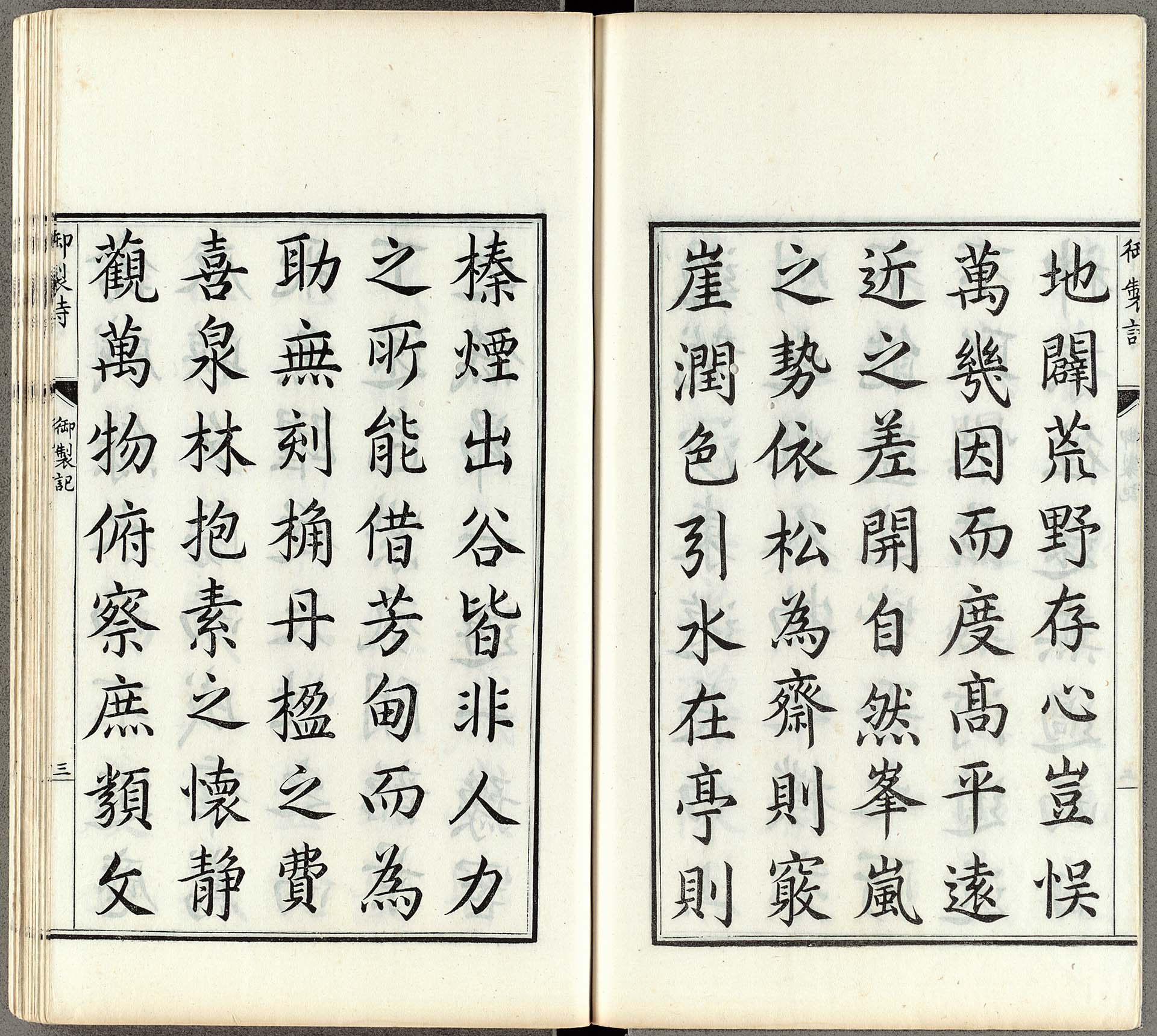

- Notes on the Summer Resort

- From fascicle 22 of Yuzhiwen Sanji (Second Supplement to the Collection of Imperial Literary Works)

- Written by Emperor Kangxi, Qing dynasty

- Jiang Lian edition, the 53rd year of the Kangxi reign (1714), Qing dynasty

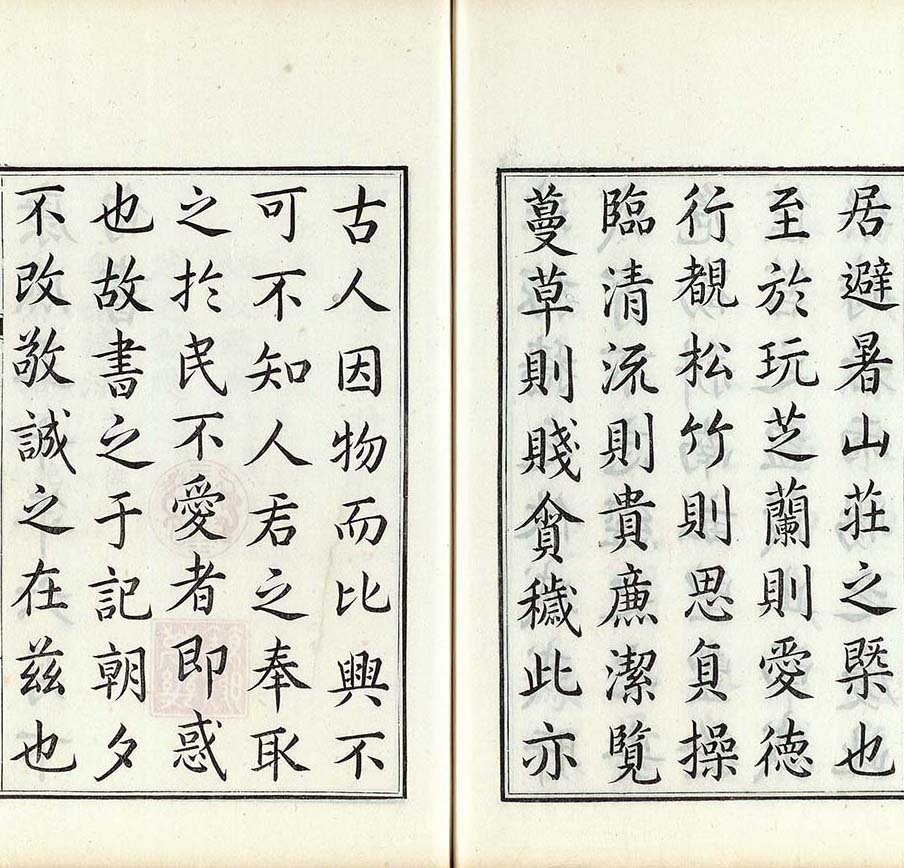

The "Notes on the Summer Resort" is an important reference for us to understand how the Summer Resort went from the Jehol Resort to the Summer Resort. The document was written in the second half of June 1711, which corresponds to the year that Emperor Kangxi changed the name of the Jehol Resort to the Summer Resort. The text states that Emperor Kangxi chose Jehol as his resort because it was close to the capital (two days round trip). Functionally, it was not much different than the Forbidden City. Another reason was that the weather and environment of Jehol was suitable for relaxation and spiritual cultivation. Finally, the text points out that the geographical scenery at Jehol allows the emperor to quietly gain insight into people's livelihoods and living, so that he can understand how to use governance to serve the people.

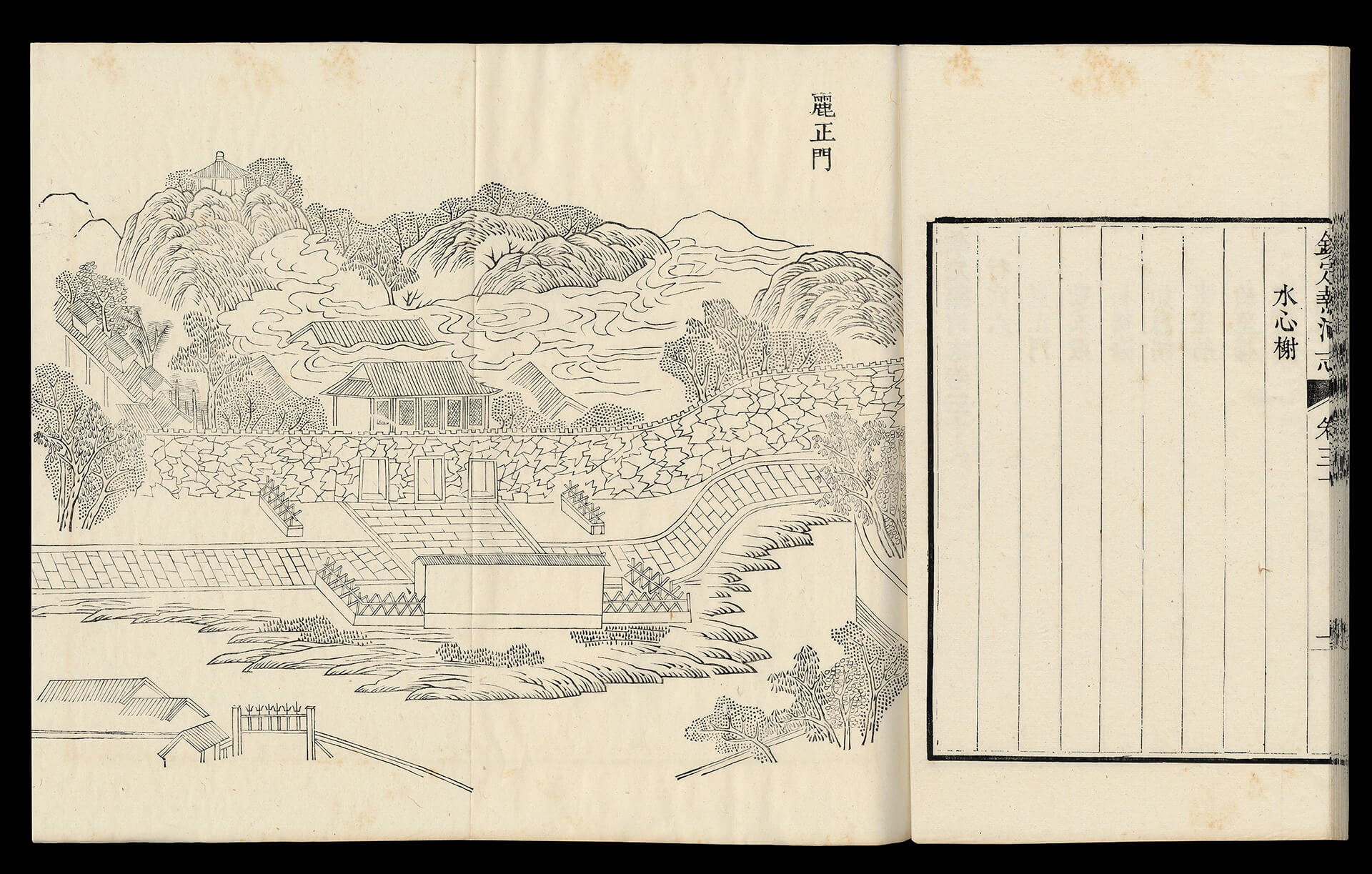

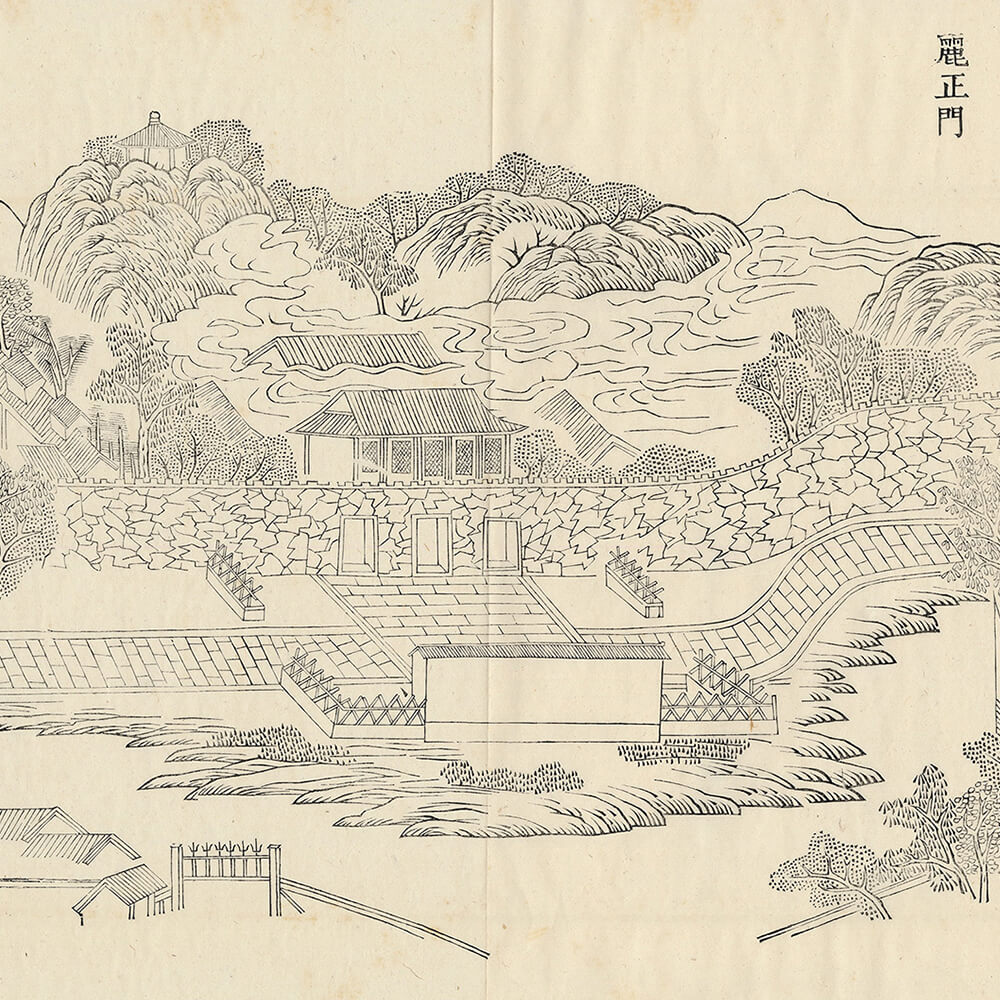

- From fascicle 30 of Qinding Jehol Zhi (Imperially Endorsed Local Gazetteer of Jehol)

- Compiled by He Shen, et al., on imperial order

- Imprint by the Imperial Printing Office at Wuyingdian Hall, 46th year of the Qianlong reign (1781), Qing dynasty

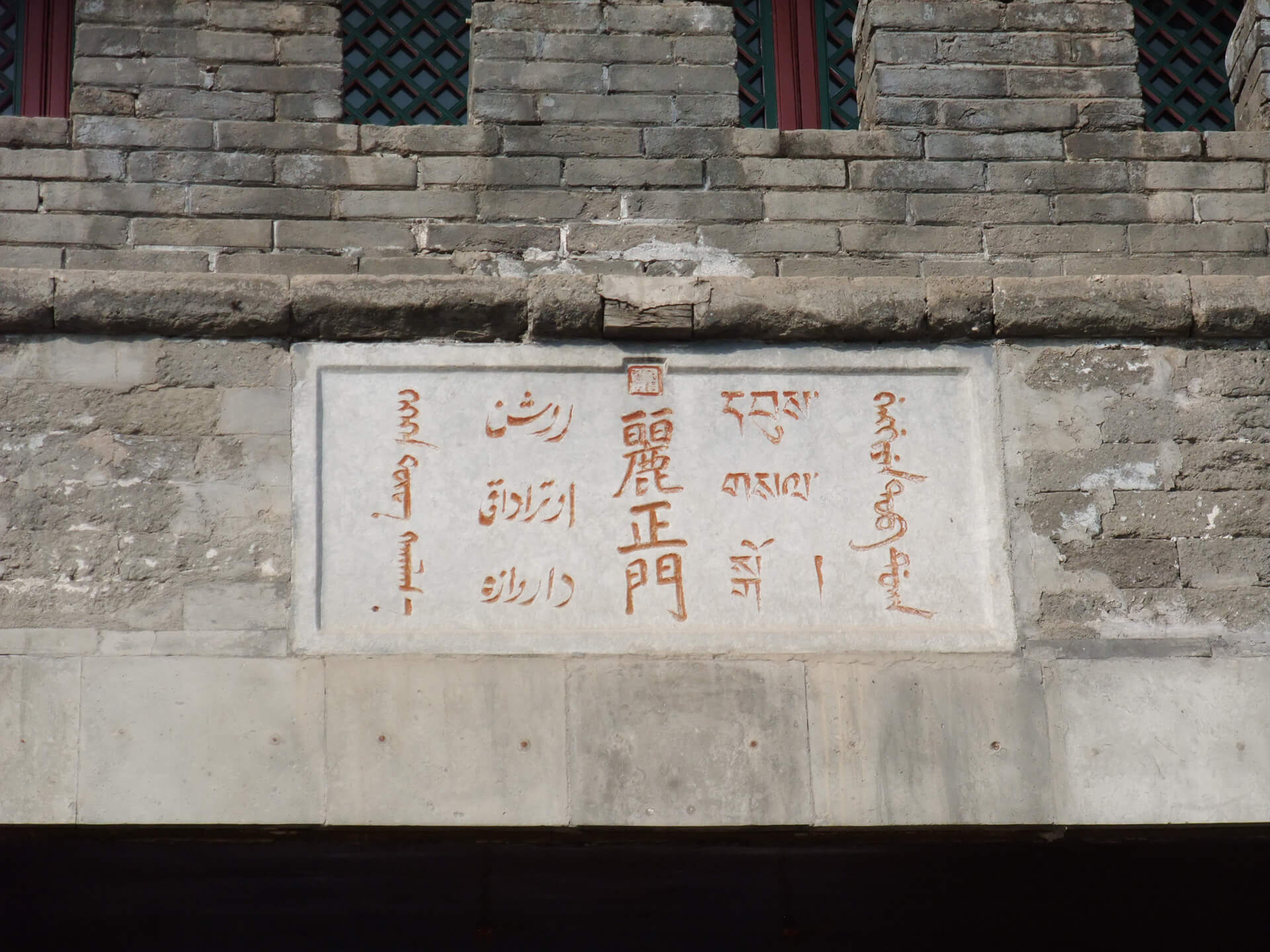

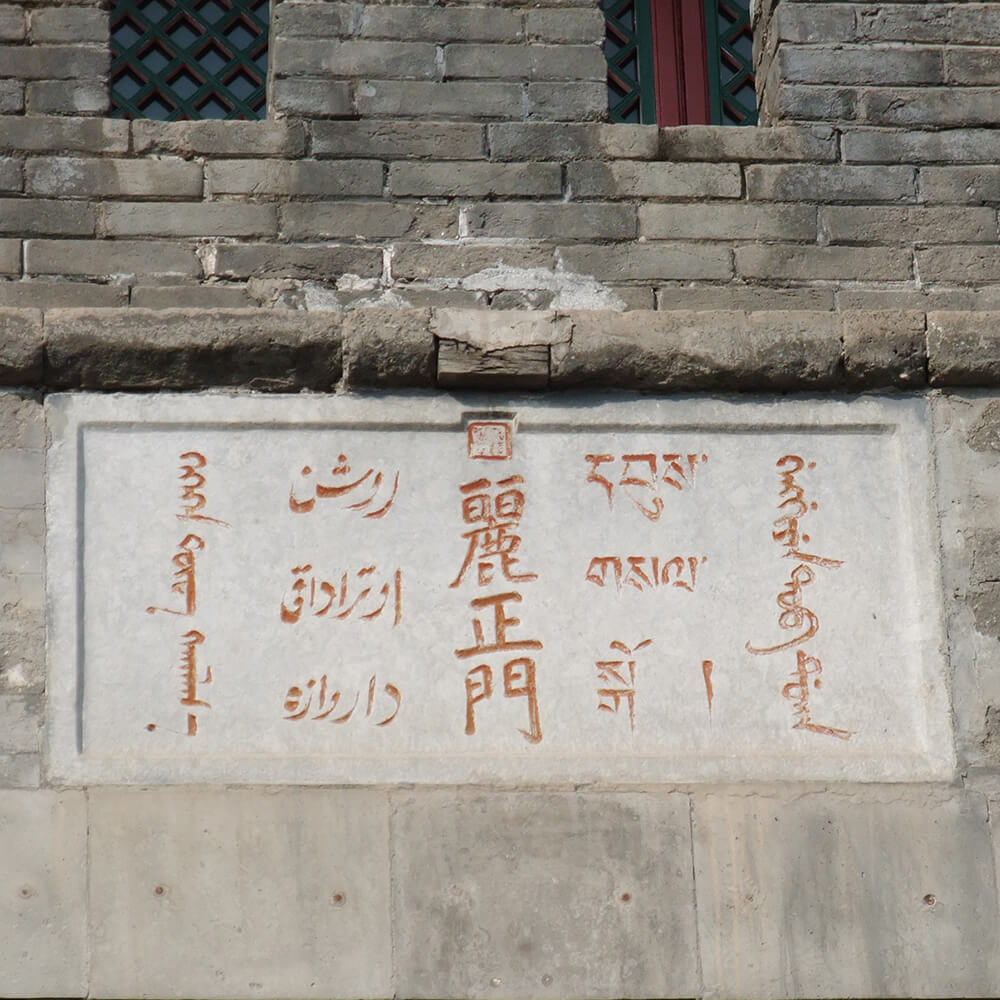

The main gate of the Summer Resort, the "Gate of Beauty and Integrity," is the first entry for entering the palace area's Main Palace. The watchtower-style building adds to the imposing atmosphere. This gate was built in 1754 and has a plaque bearing the words "Gate of Beauty and Integrity" written in Chinese by Emperor Qianlong. The same text is repeated in Manchu, Tibetan, Hui, and Mongolian from right to left. The Chinese words "Beauty and Integrity" was inspired by a section of the I Ching (the Book of Changes), "The sun and moon have their place in the sky. All the grains, grass, and trees have their place on the earth. The double brightness adheres to what is correct, and the result is the transforming and perfecting all under the sky". In Manchu (genggiyen tob duka), it means "bright gate," which is a simpler meaning. The five different languages on the gate reflect the many ethnic cultures under the Qing rule.

Useless Great Wall Theory

After the Revolt of the Three Feudatories (1673-1681) was put down in 1681, the Qing dynasty began to focus on improving the safety of the northern border. To protect against threats from Russian and the Oirats Dzungar Tribe, the Qing dynasty took a diplomatic strategy and actively wooed the Southern Gobi Desert Mongols and the Khalkha Mongols. The Qing used marriage between the Manchu and the Mongols to shore up border defense. Emperor Kangxi believes that China's tradition of building the Great Wall added to the burden of the public, but could not ensure the safety of the nation. By engaging in marriage to the northern Mongol alliance and by awarding them with titles, the Qing fortified the north and had a border policy that ensured long-term peace. The "useless Great Wall theory" was Emperor Kangxi's border strategy for using various Mongol tribes as a screen. The Jehol area and the Summer Resort played an important role in the empire's border defense strategy.

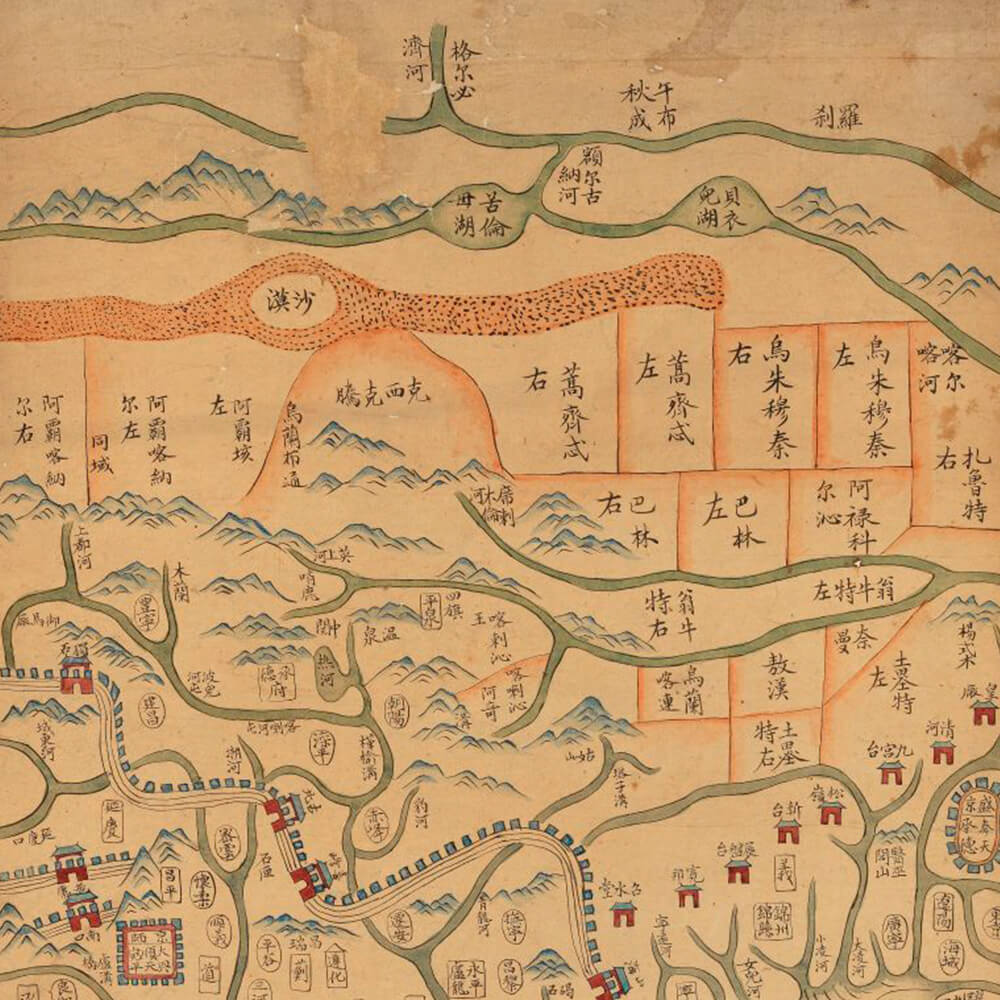

Complete Map of the Great Qing's Unified Realm of All Under Heaven

- Ink and color on paper

- 16th year of the Jiaqing reign (1811), Qing dynasty

This painting was painted in 1811 by an unknown painter based on supplements done in 1767 to Huang Qianren's (Zhejiang Yuyao; 1694-1711) old paintings. The lines are simple and the colors elegant. Many copies of this painting are in circulation. The grandfather of Huang Qianren was the famed philosopher Huang Zongxi from the Ming and Qing dynasty (1610-1695). His father was Huang Baijia (1643-1709), a Jiangnan literatus in Qing dynasty famed for his loyalty and righteousness. This painting is composed of eight hanging scrolls, among which three depict the geography of Beijing, Jehol, and Mongolia to the north. The painting specifically reflects the important position that Jehol had in relation to the Qing Empire and Mongolia.

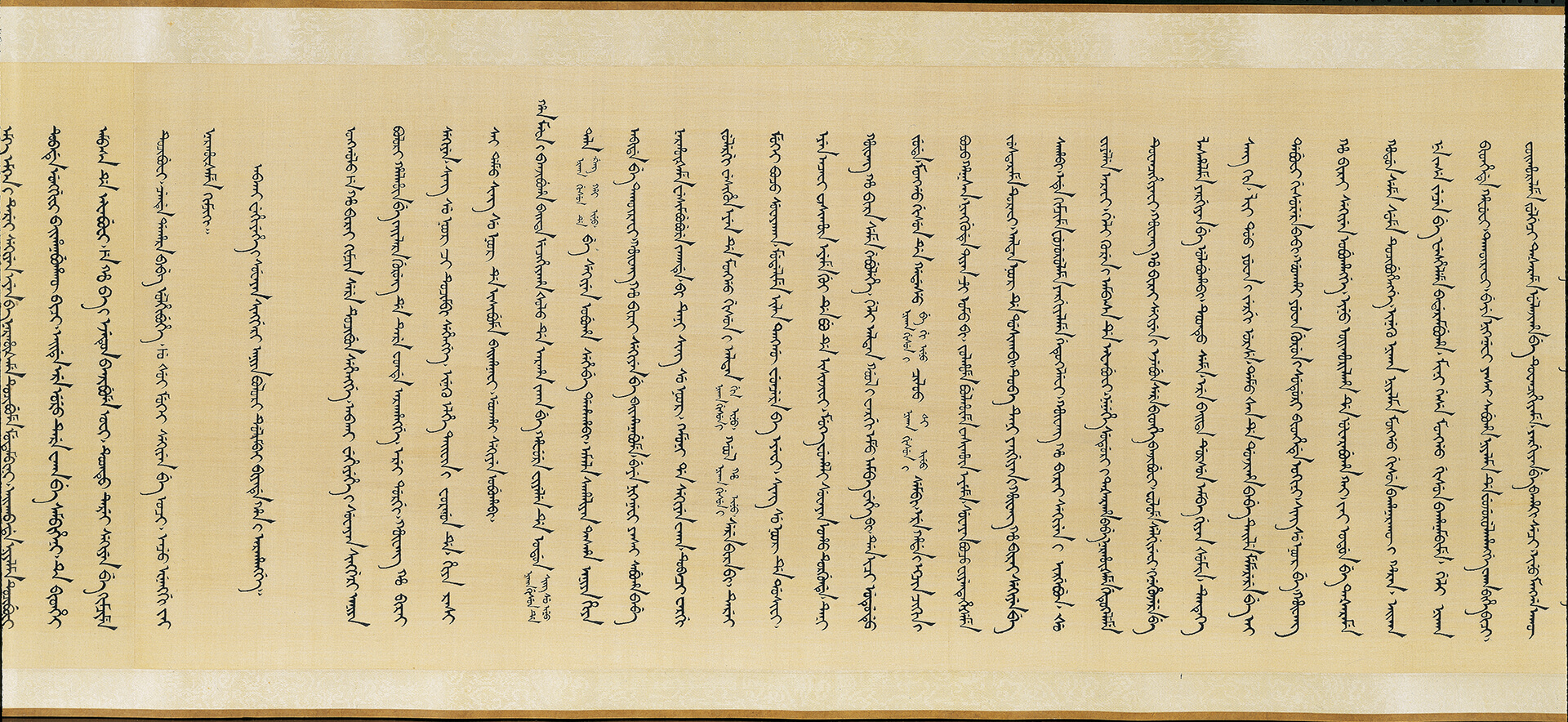

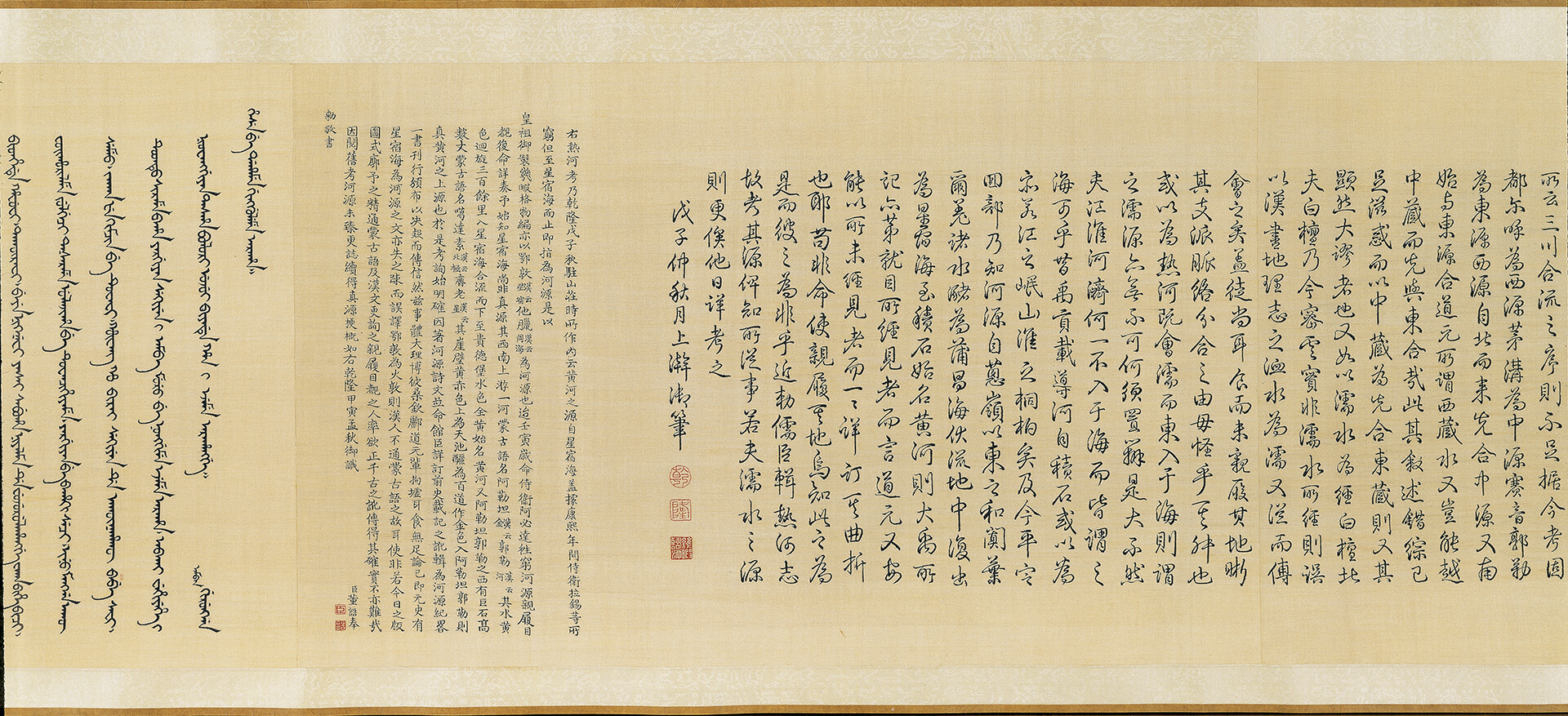

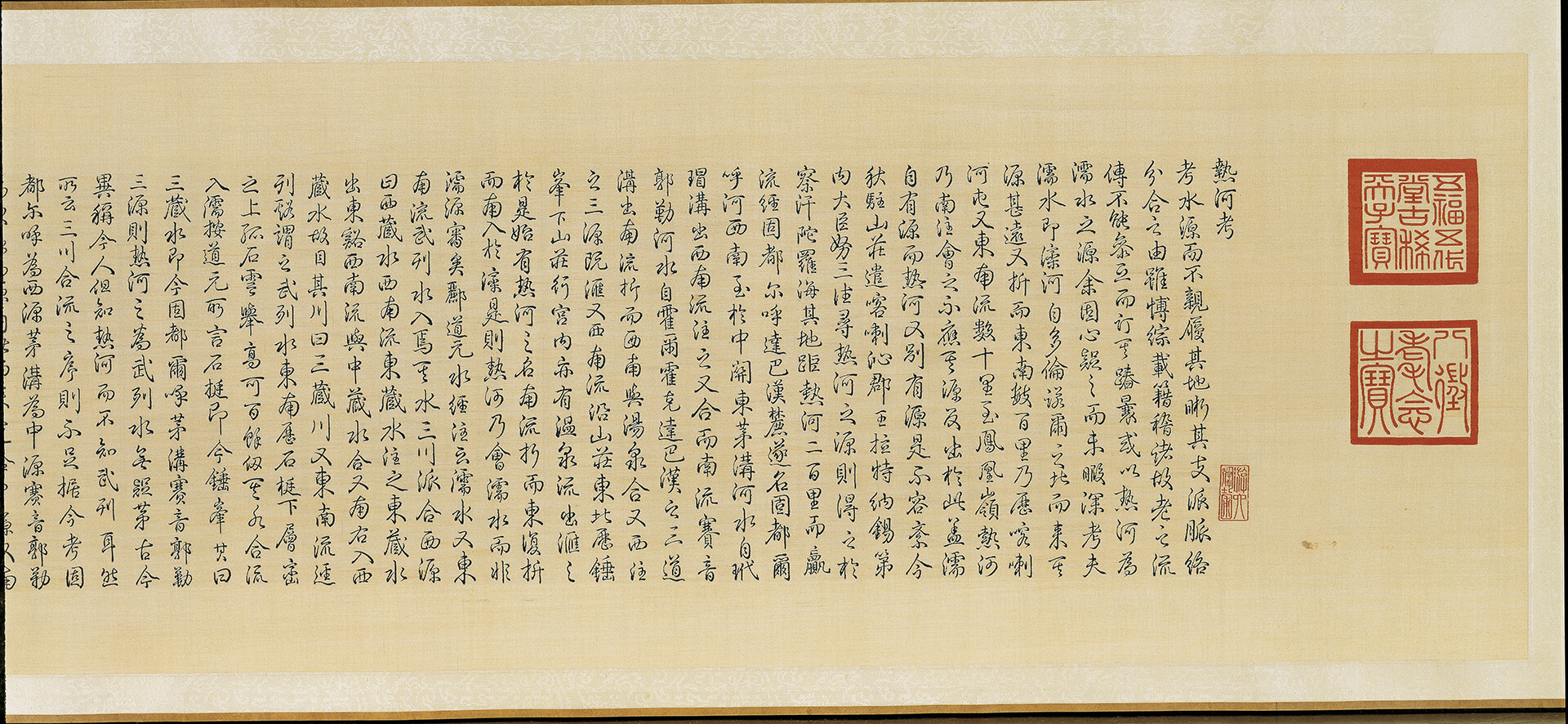

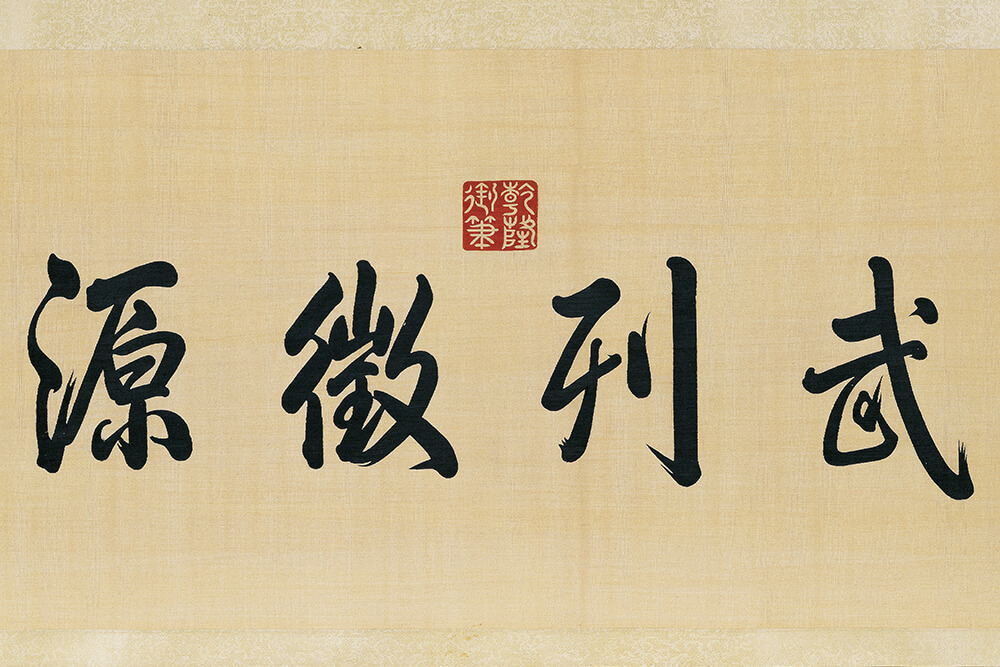

Tapestry with Emperor Qianlong's Transcription of "Study on Jehol"

- Written by Emperor Qianlong, Qing dynasty

- 33rd year of the Qianlong reign (1768), Qing dynasty

This tapestry contains Emperor Qianlong's study of the rivers surrounding Jehol in 1768. He was under the impression that Jehol (formerly Wulieshui) earned its name because of the hot springs found in the Jehol Palace. The heading of the tapestry, written on beige kesi, consists of big black Chinese characters "Wu Lie Zheng Yuan" written in semi-cursive script. The combination of Chinese characters in cursive script and Manchu alphabets (written by the emperor) creates an elegant, refined style. Also found in the tapestry is evidence of the origins of the Yellow River that Dong Gao (1740-1818) copied at the emperor's order, indicating that this tapestry was made in the later years of the emperor's reign.

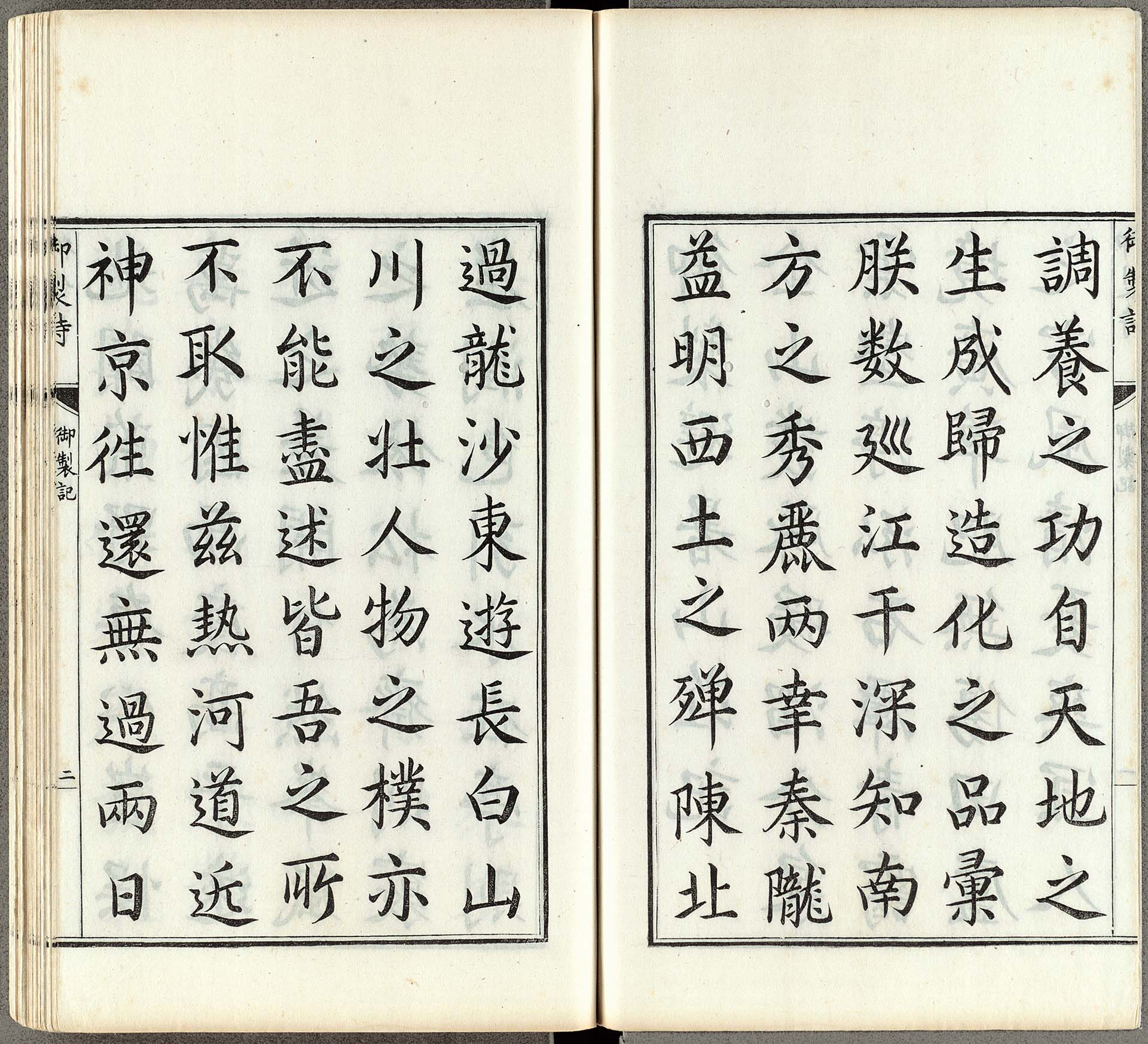

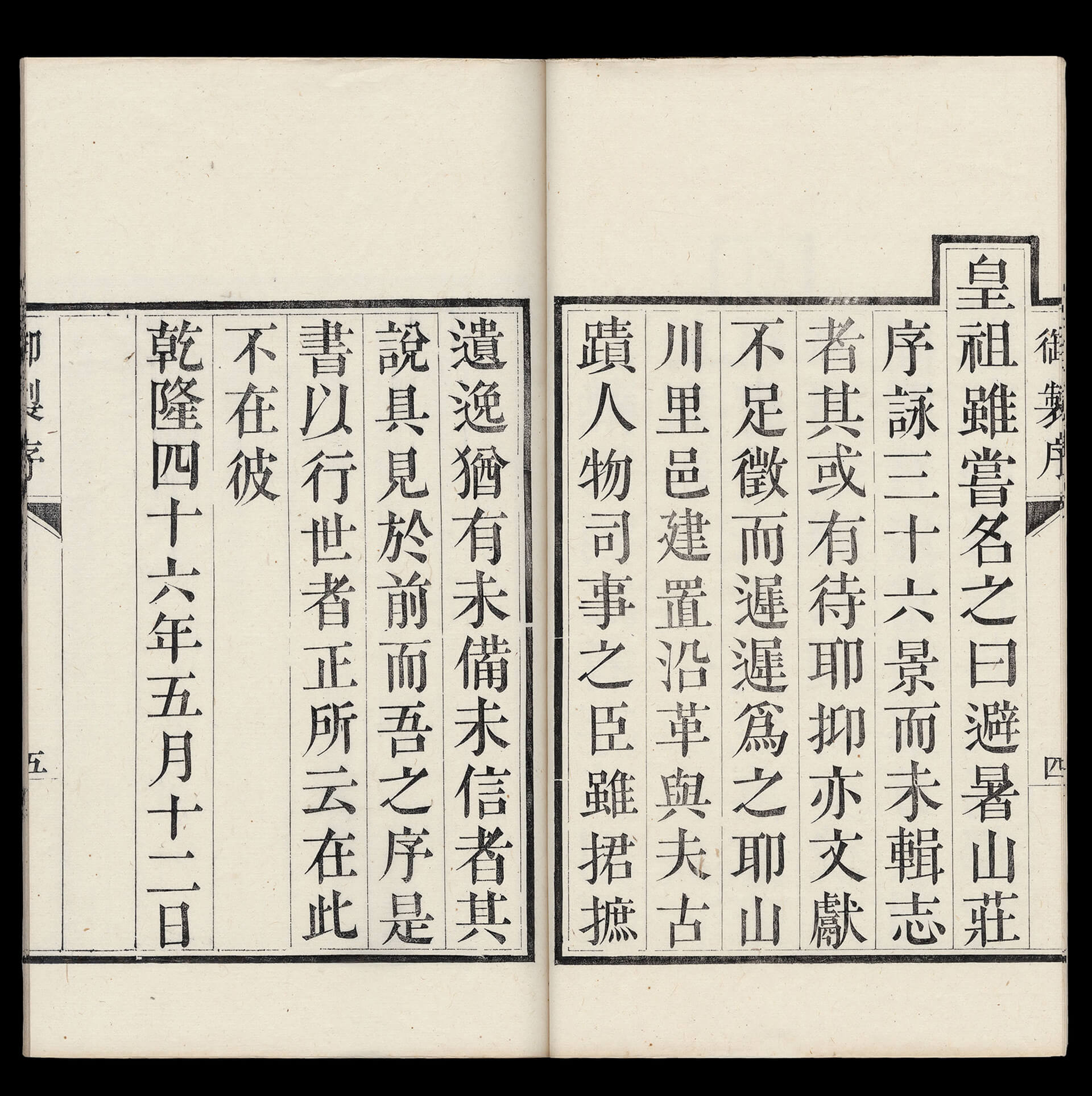

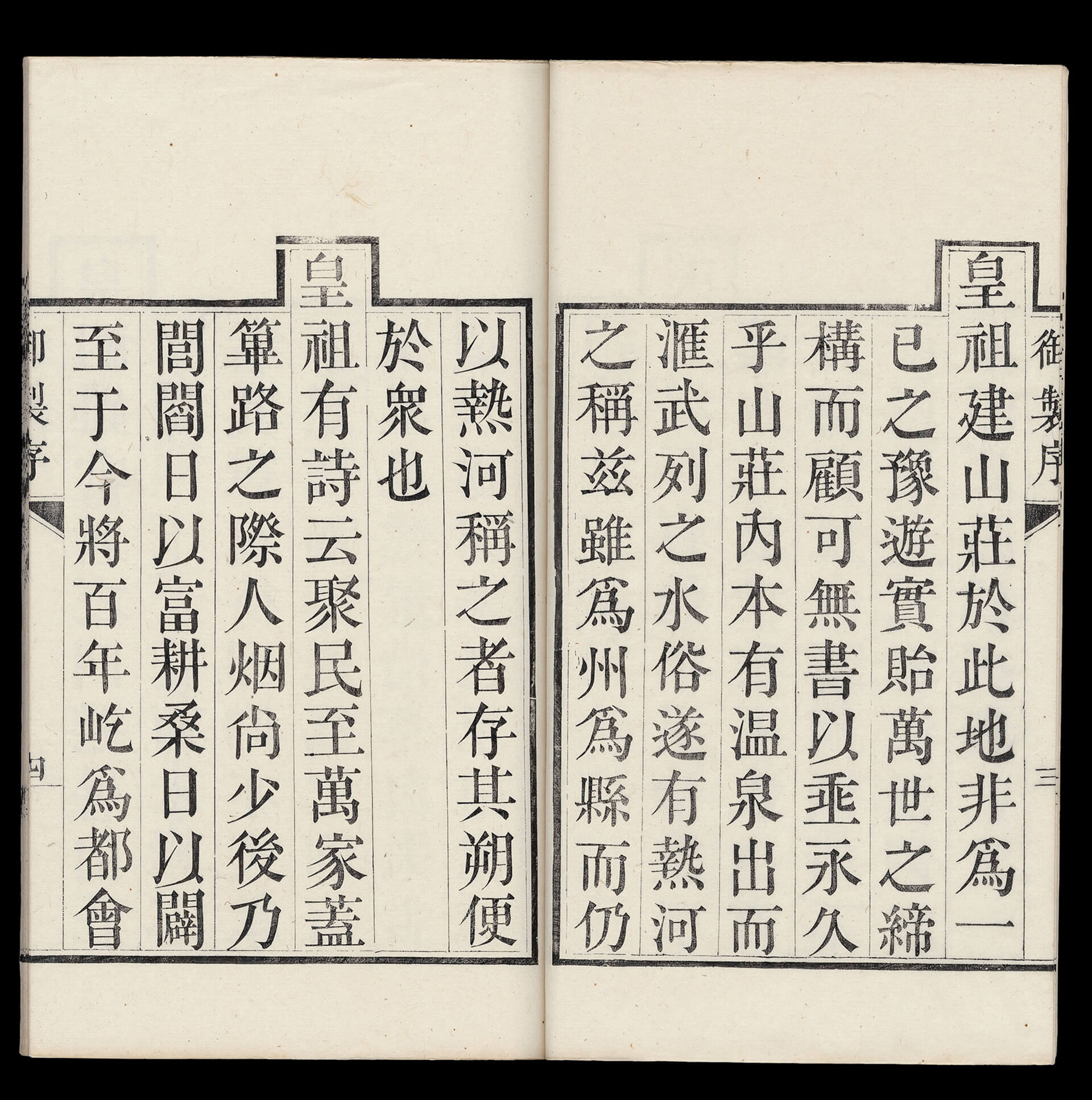

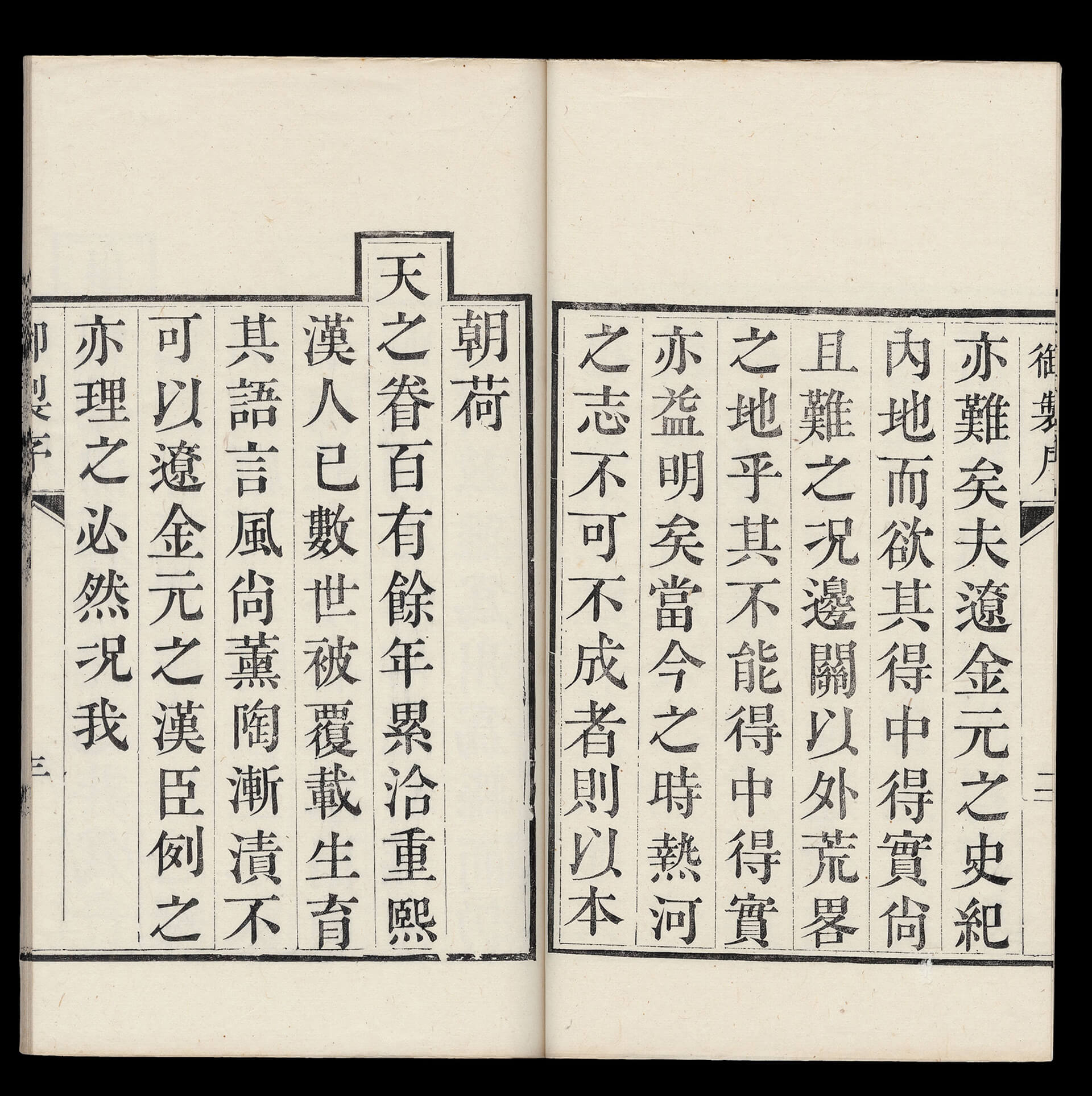

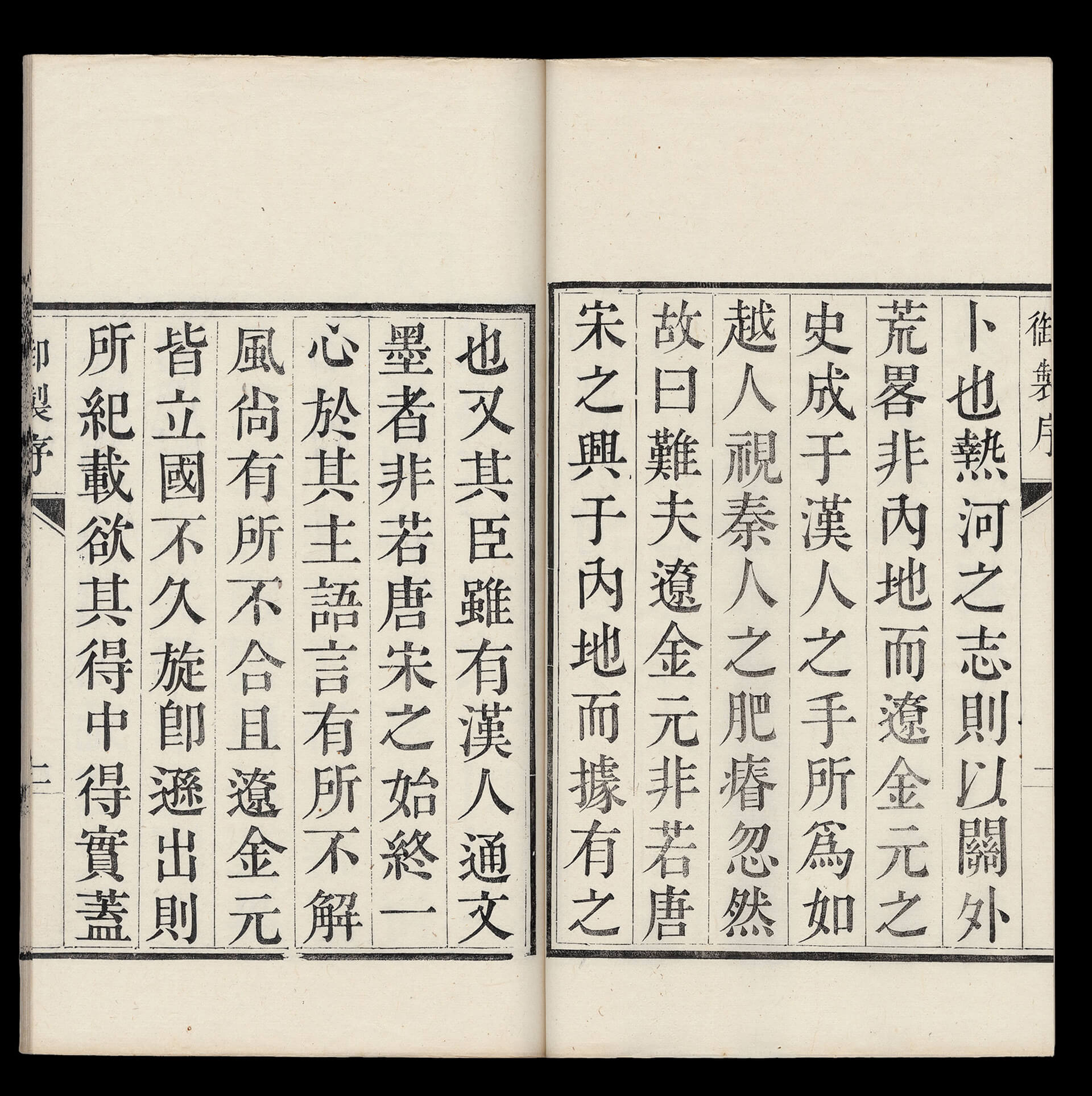

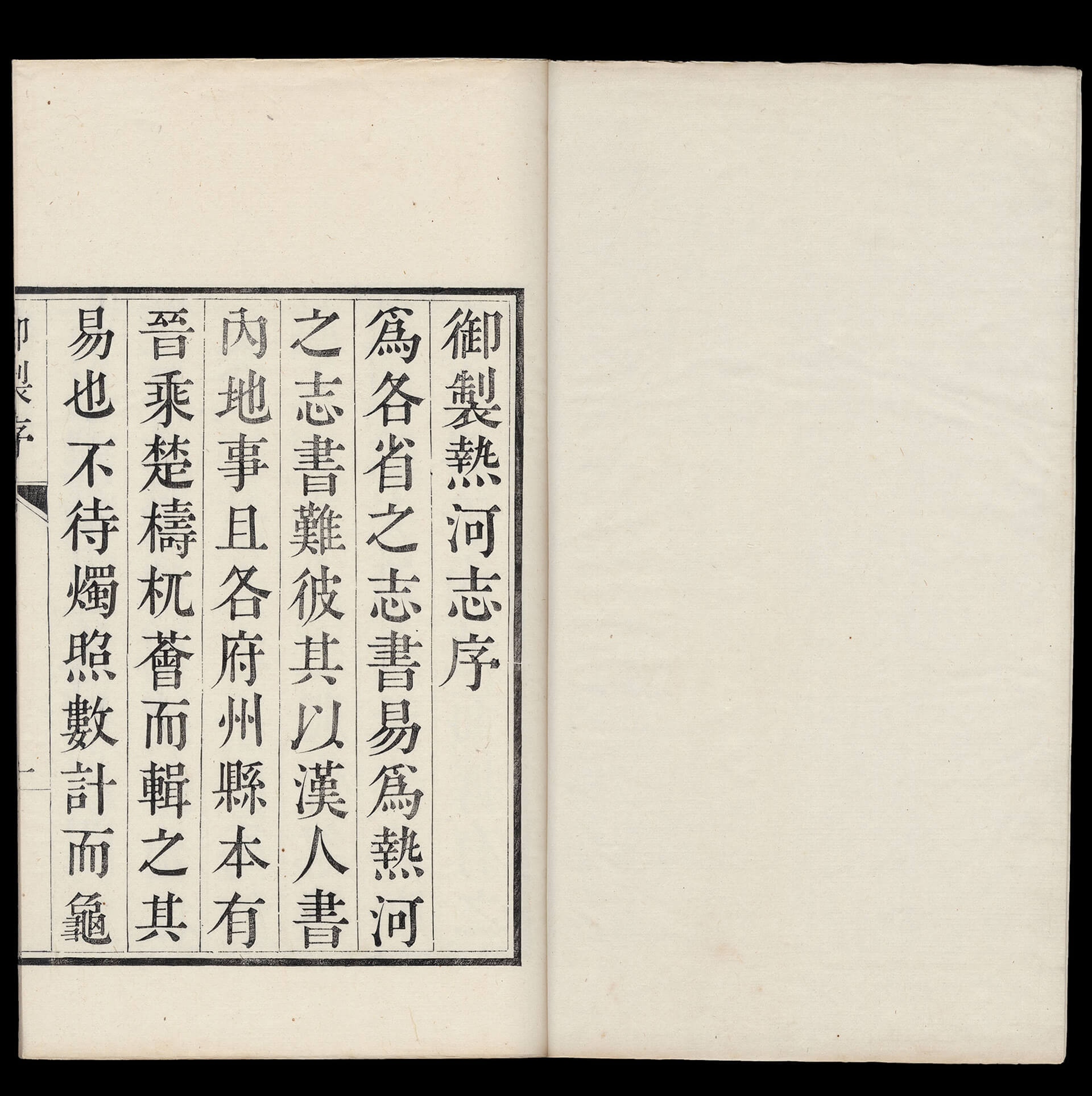

Preface to Jehol Zhi (Local Gazetteer of Jehol) by Emperor Qianlong

- rom Qinding Jehol Zhi (Imperially Endorsed Local Gazetteer of Jehol)

- Compiled by He Shen, et al., on imperial order

- Imprint by the Imperial Printing Office at Wuyingdian Hall, 46th year of the Qianlong reign (1781), Qing dynasty

Jehol Zhi is a unique local chronicle. Contrary to most local chronicles, which are compiled by local state and prefectures, Jehol Zhi was compiled by important officials such as He Shen (1750-1799) and Liang Guozhi (1723-1786) at the order of the Qing central government. This revealed how important Qing government valued Jehol.

The chronicle was completed in 1781, with a preface written by the emperor. The chronicle highlighted two reasons why it was written as well as two major challenges hindering its completion. The two reasons were (a) since the establishment of Jehol by Emperor Kangxi over a century ago, it had witnessed a growing population and slowly became a city; and (b) Emperor Kangxi ran the city and summer resort not for personal pleasure (i.e., to visit there for vacations during the summer) but to strengthen the northern border defense against Mongolia. The two challenges were (a) located in a remote region, Jehol lacked historical data; and (b) most of the existing historical data of Jehol were written by Han people who lacked a thorough understanding of the local customs and languages of the city. The last segment of the preface explains that Jehol earned its name because of its confluence of hot springs and the Wulie River. The authors used the name of the city to name its chronicle.

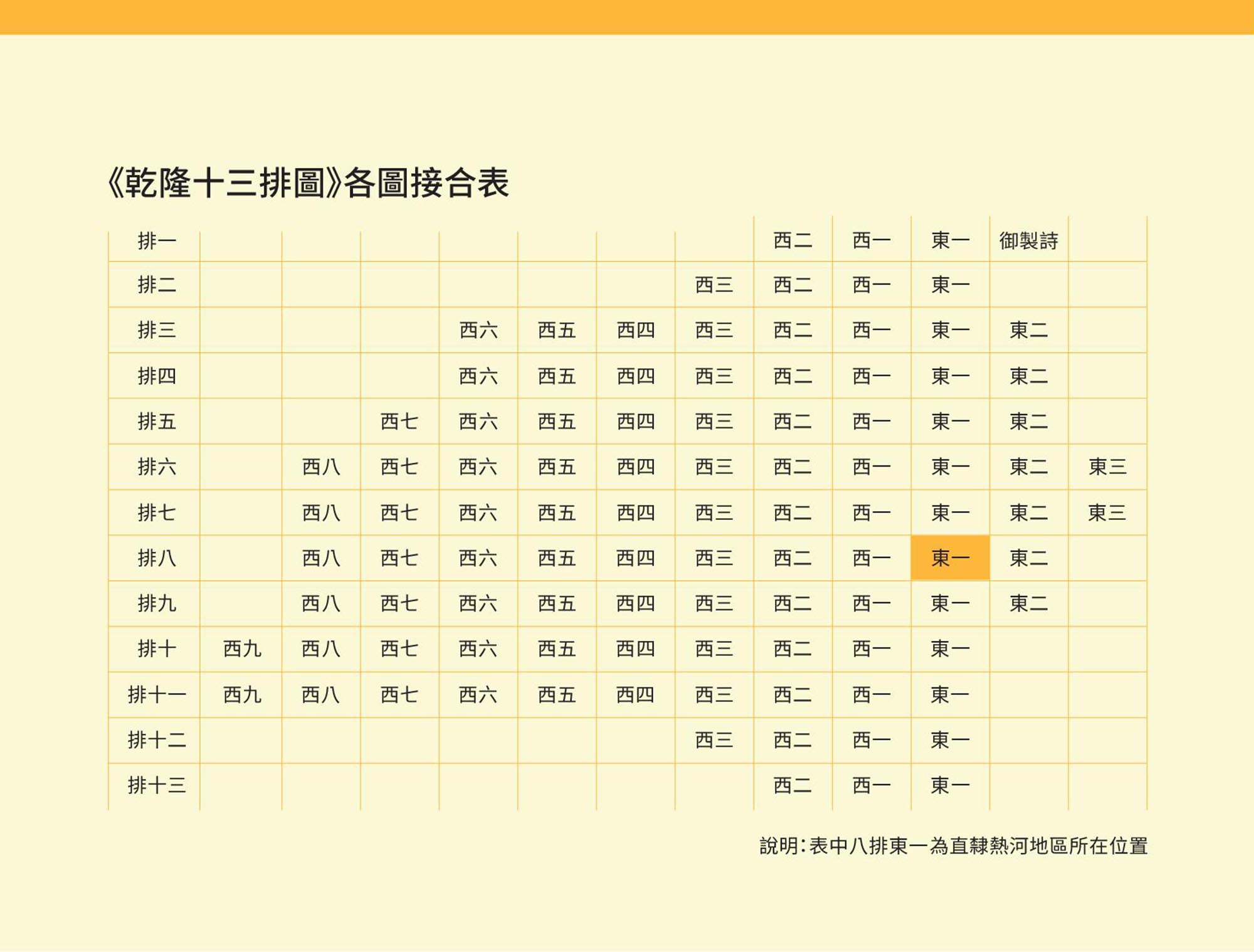

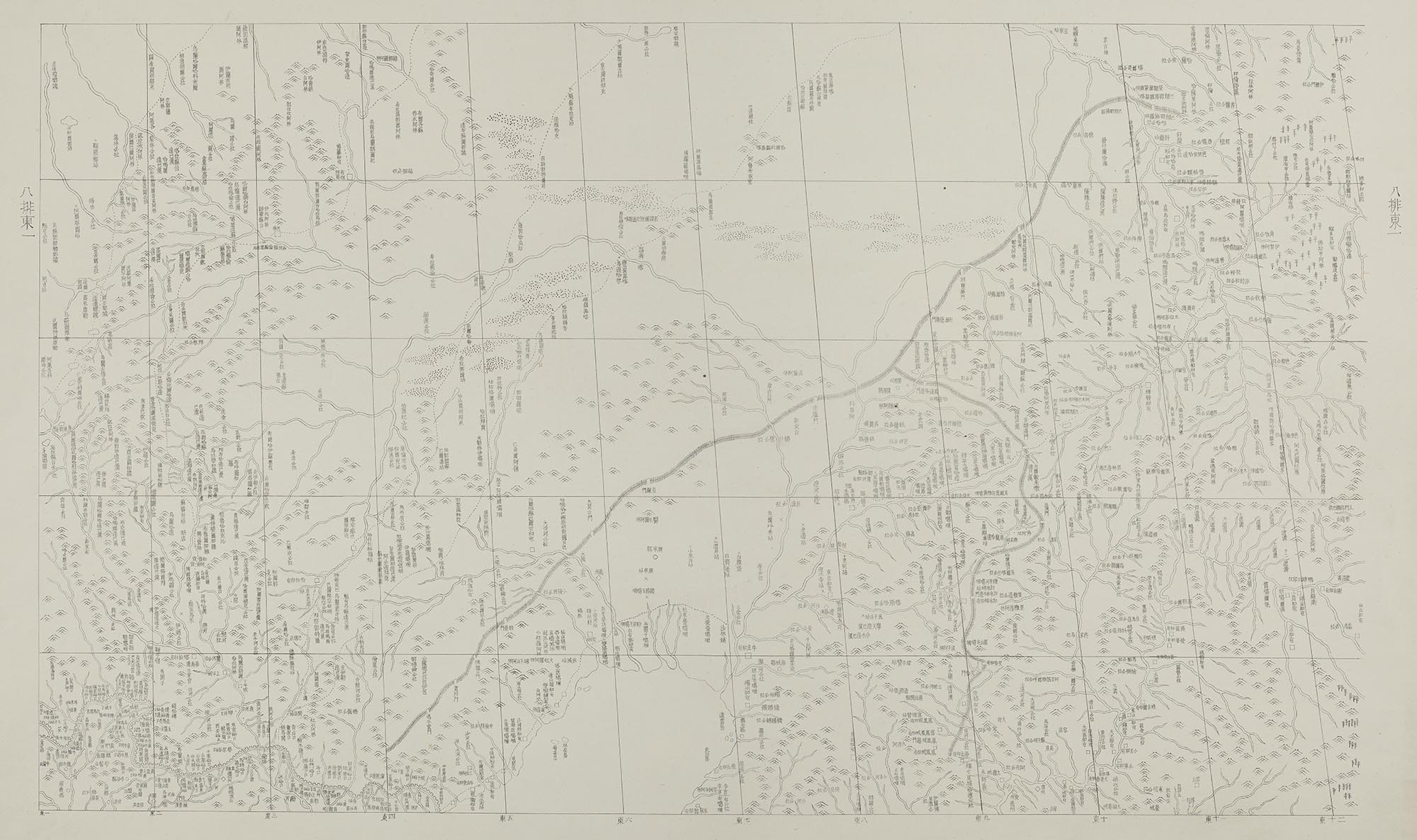

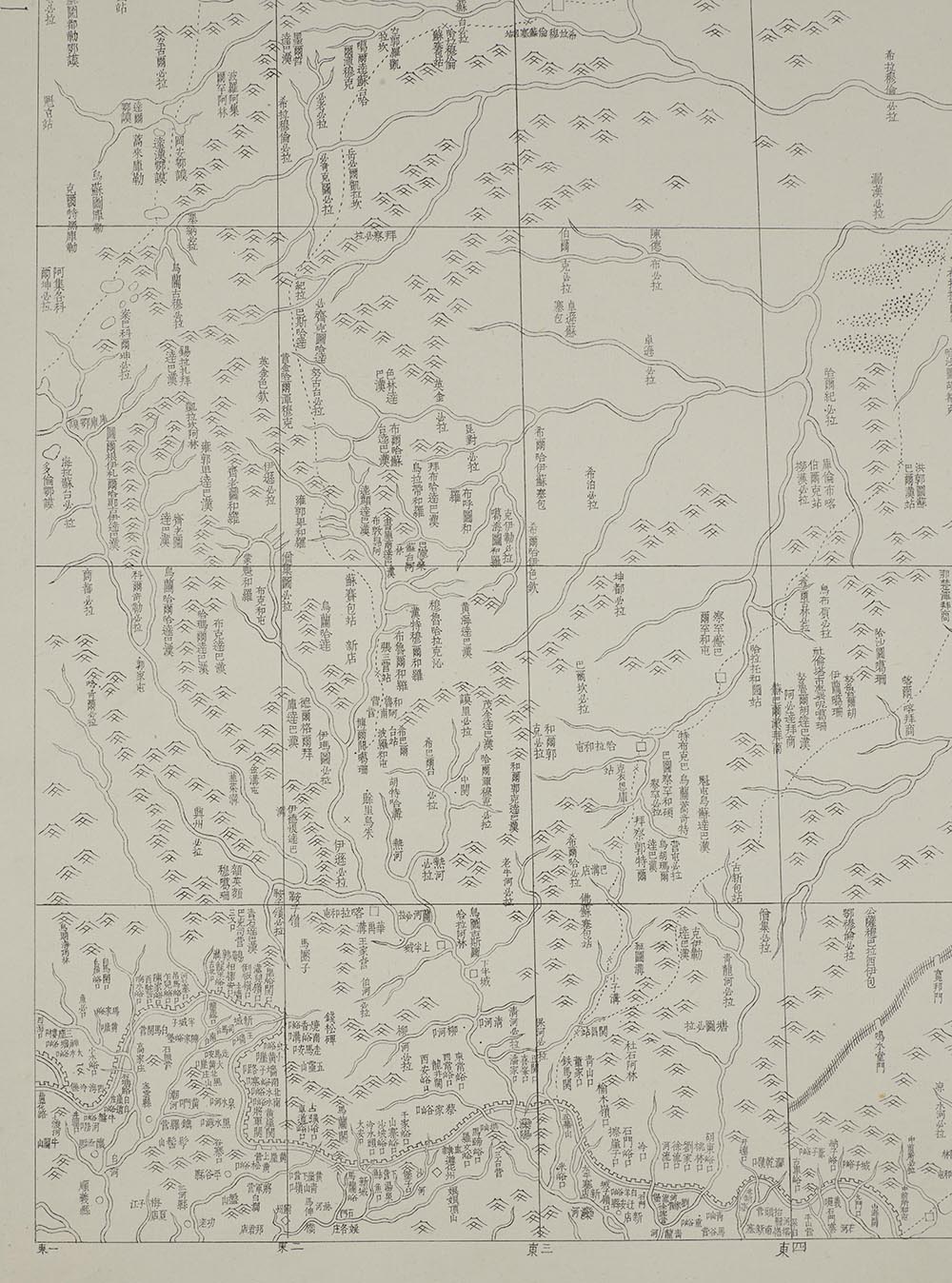

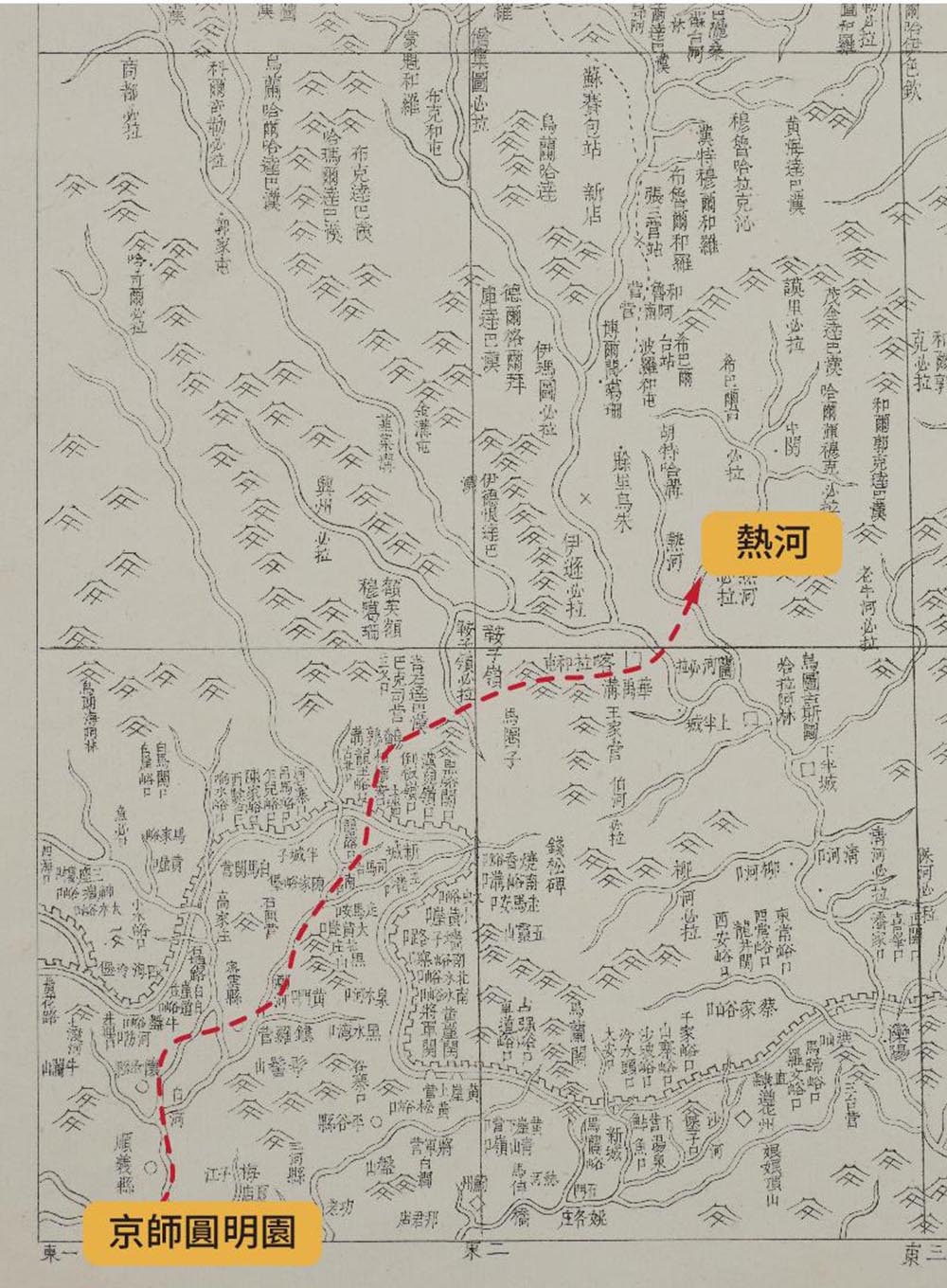

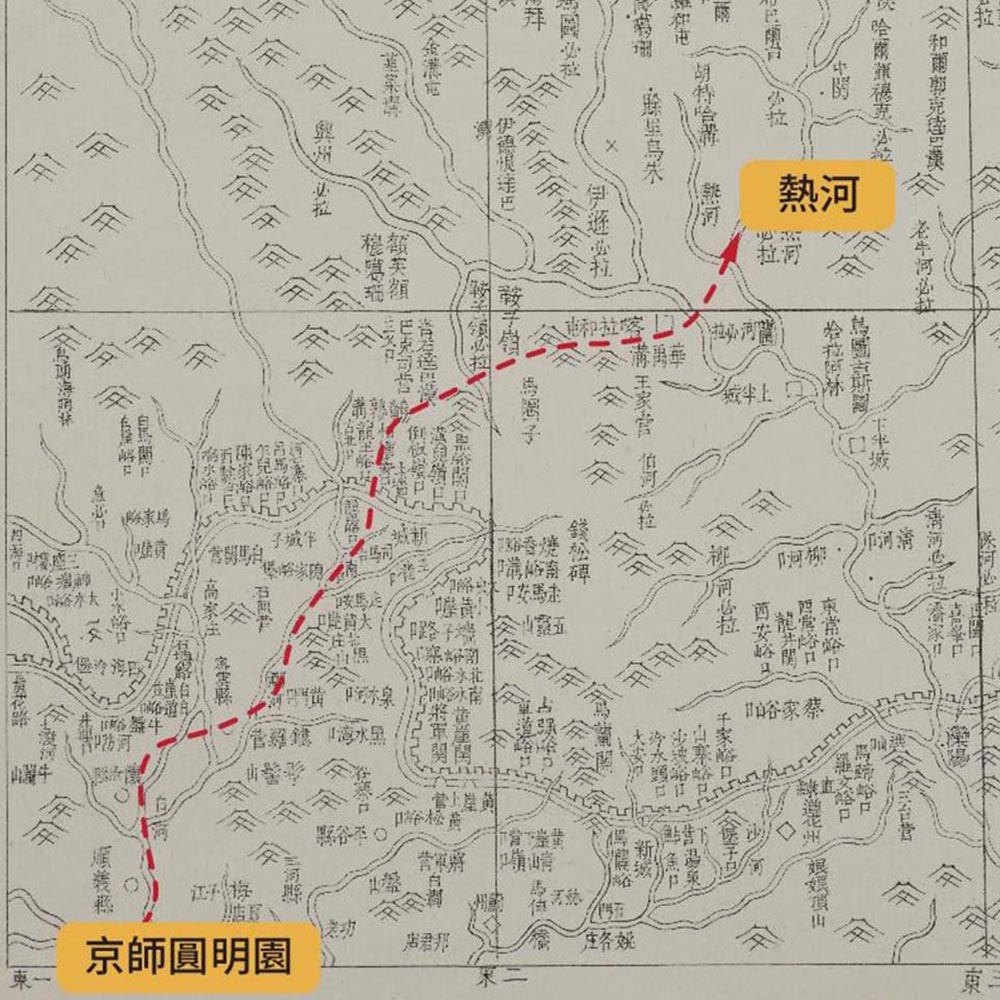

The Qianlong Map in 13 Rows: 8th Row East 1

- Reprinted by the Palace Museum in 1932 from the copperplates produced in the 25th year of the Qianlong era (1760)

During the early Qing dynasty (i.e., Kangxi and Yongzheng's reigns), the emperors sent Western missionaries to survey and map all Chinese provinces, successively completing the "Kangxi Imperial Atlas of China" and the "Yongzheng Map in 10 Rows." During the 1950s and 1960s, the inclusion of Xinjiang led to the creation of the "Qianlong Map in 13 Rows." Said atlas was redrawn on the basis of the original maps and was known as the most comprehensive map in Asia at that time.

There are 103 pages in this map plus another page containing imperial poems written by Emperor Qianlong. French missionary Micheal Benoist (1715-1774) converted the 104 pages into 104 copperplate etching-based printing. The map, which covers Asia in its entirety, is divided into a row every five degrees in latitude. The map is crucial to understanding the administrative regions of the Qing empire, river station distributions, and place name changes in the 18th century.

The first edition of "The Qianlong Map in 13 Rows" was printed in a small number, which was a rare occurrence. When the National Palace Museum made an inventory of its artifacts in in 1925, it discovered that the aforementioned original copper plates were perfectly preserved. Professor Zhu Xizu (1879-1944) of Peking University later identified the plates as being made during the Qianlong era. 10 sets of this map were then printed using such copper plates, and one of which was taken by the National Palace Museum when it relocated southwards during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Said set is the "The Qianlong Map in 13 Rows" in the collection of the National Palace Museum today.

The 8th Row East 1 being displayed here shows the capital city and Jehol. The painting was done in great detail, the place names are clear, and the distribution of zhou, counties, mountains, and rivers is thoroughly marked, enabling viewers to understand the geographical environment surrounding Jehol.

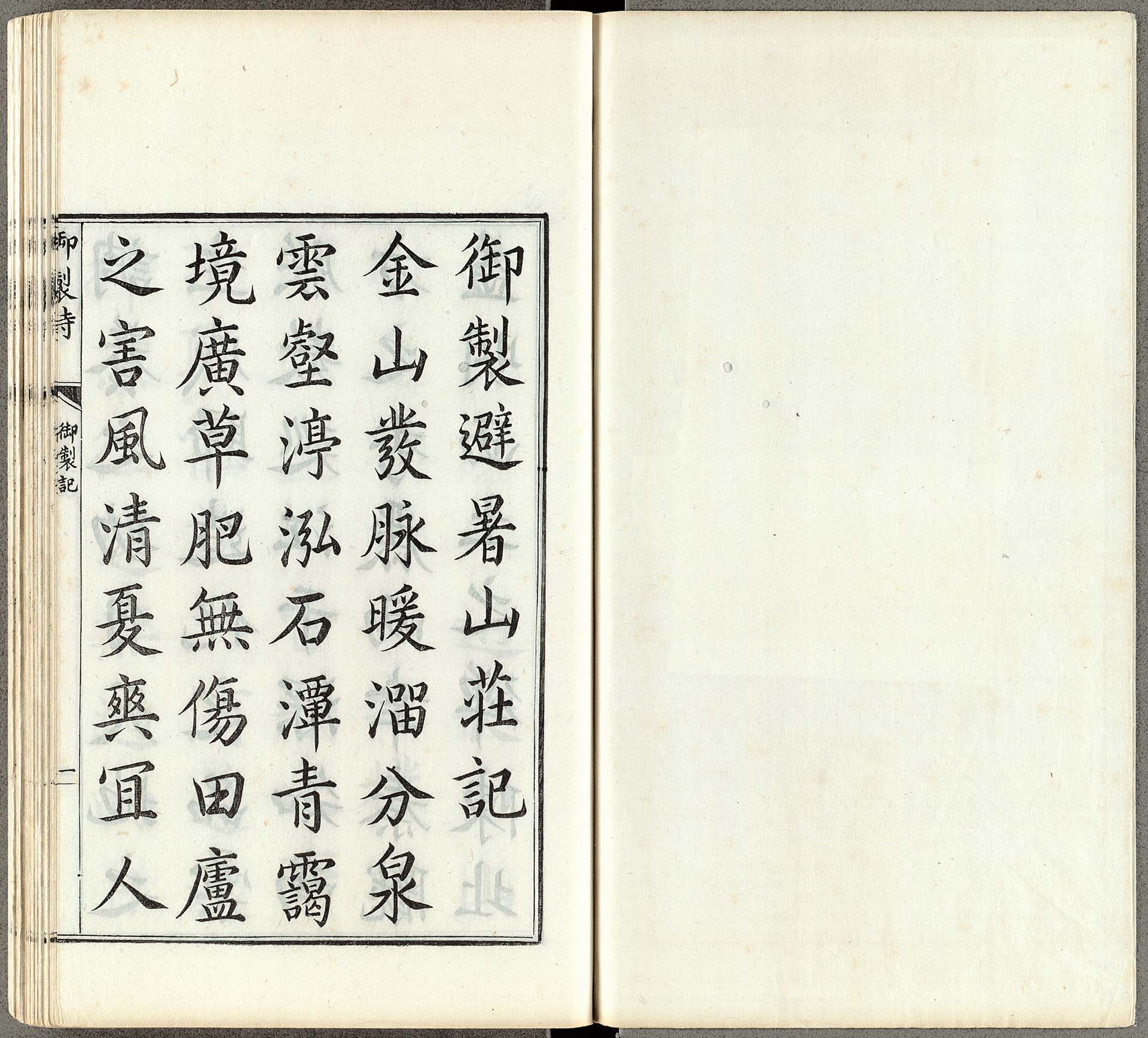

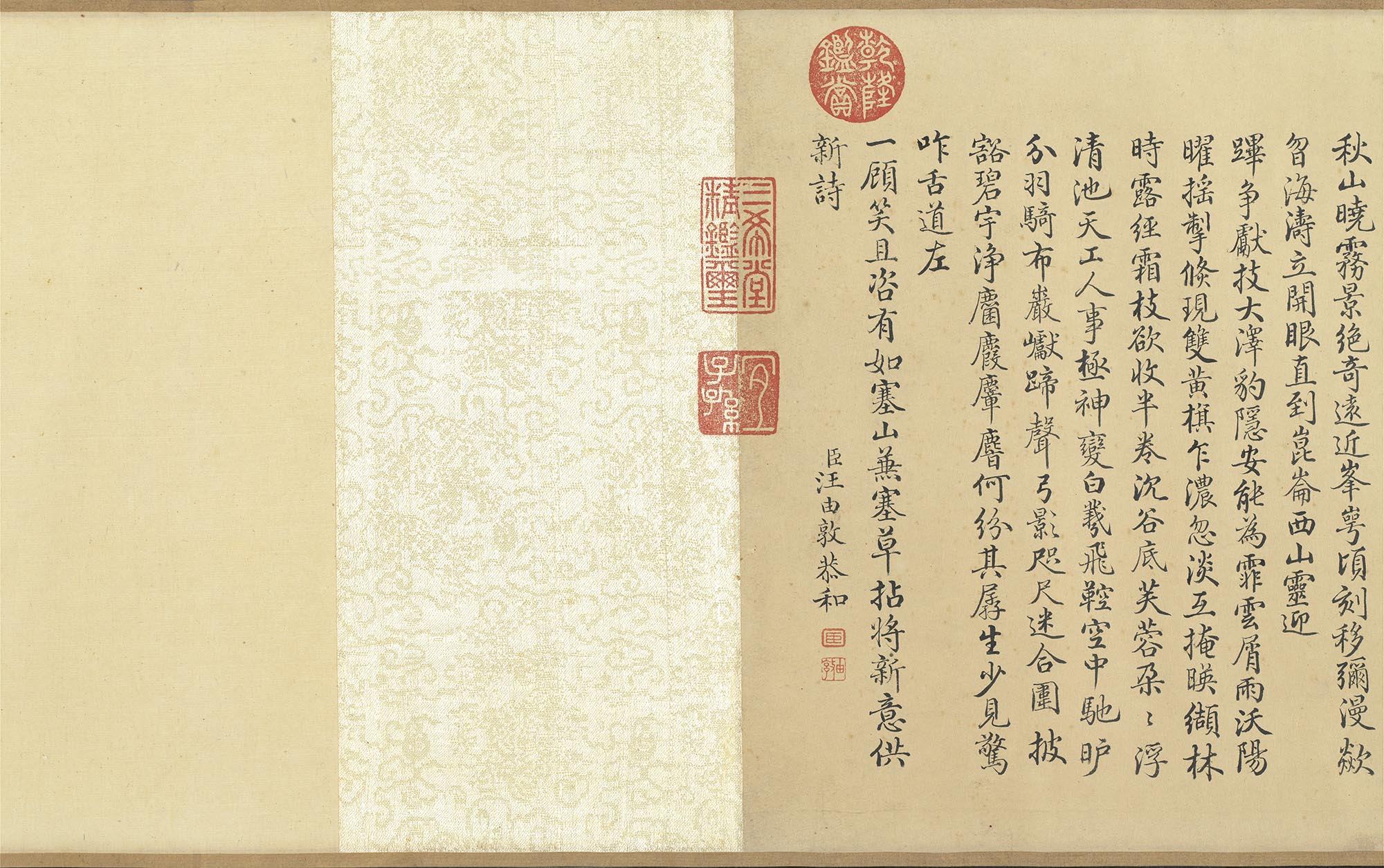

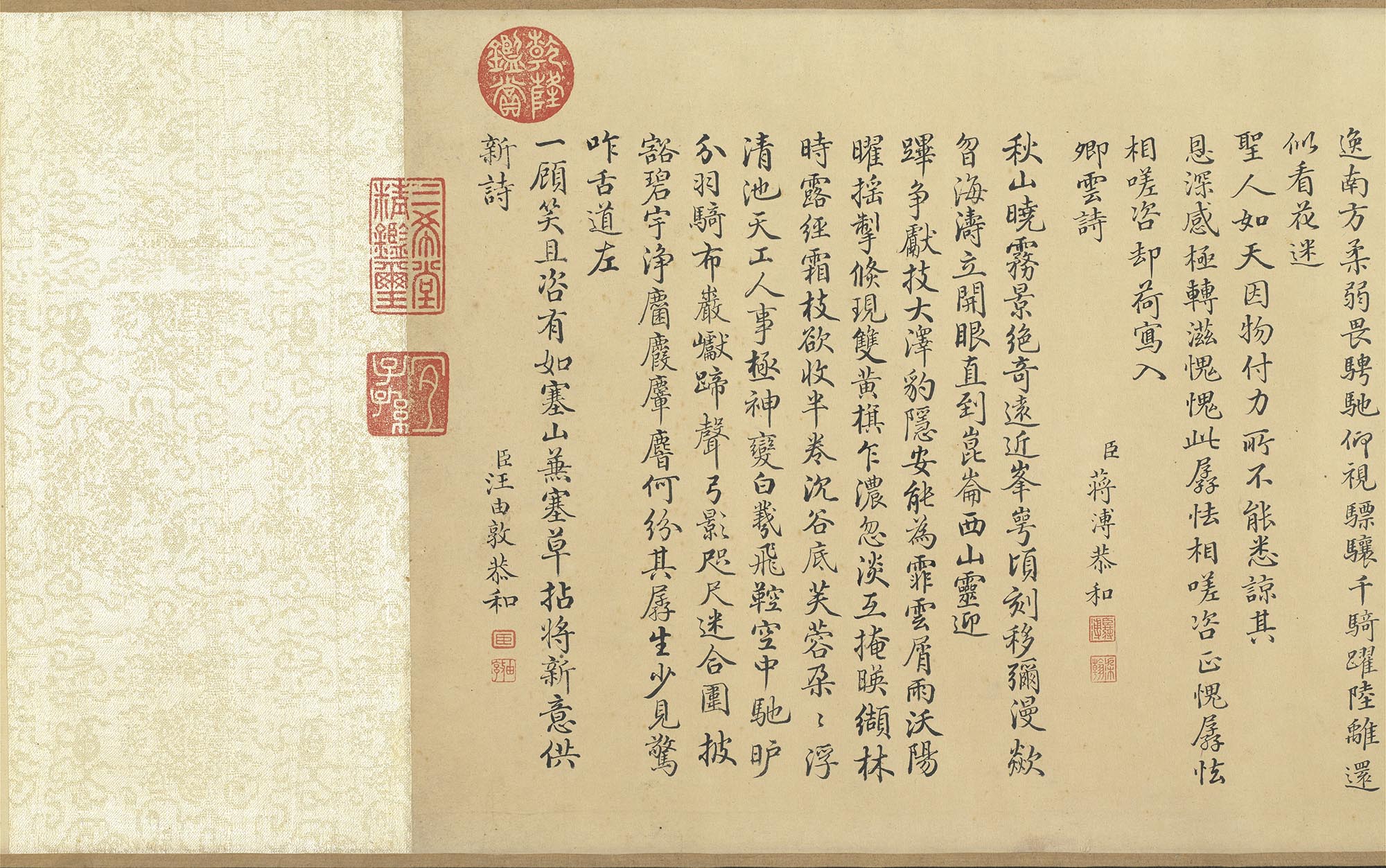

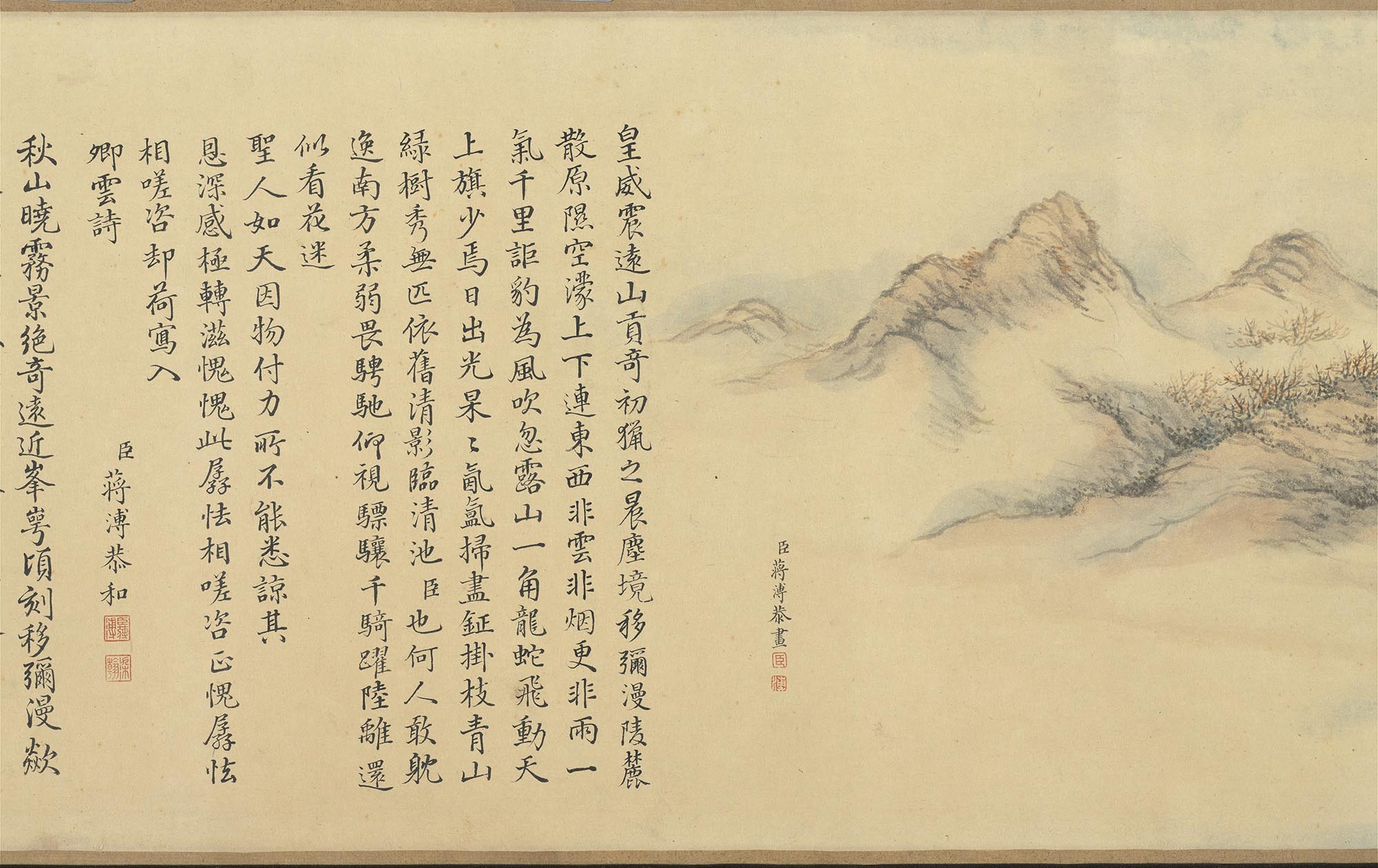

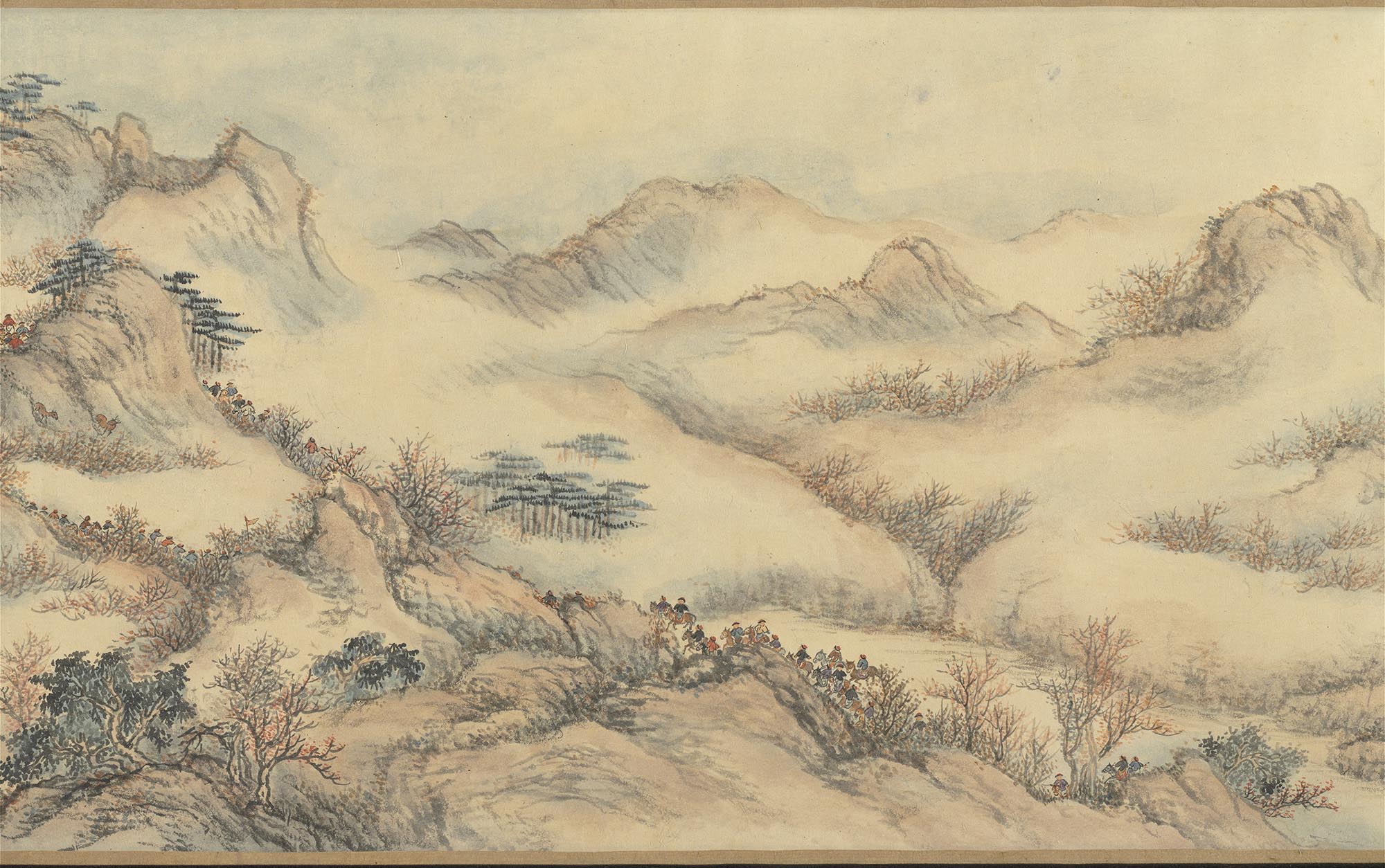

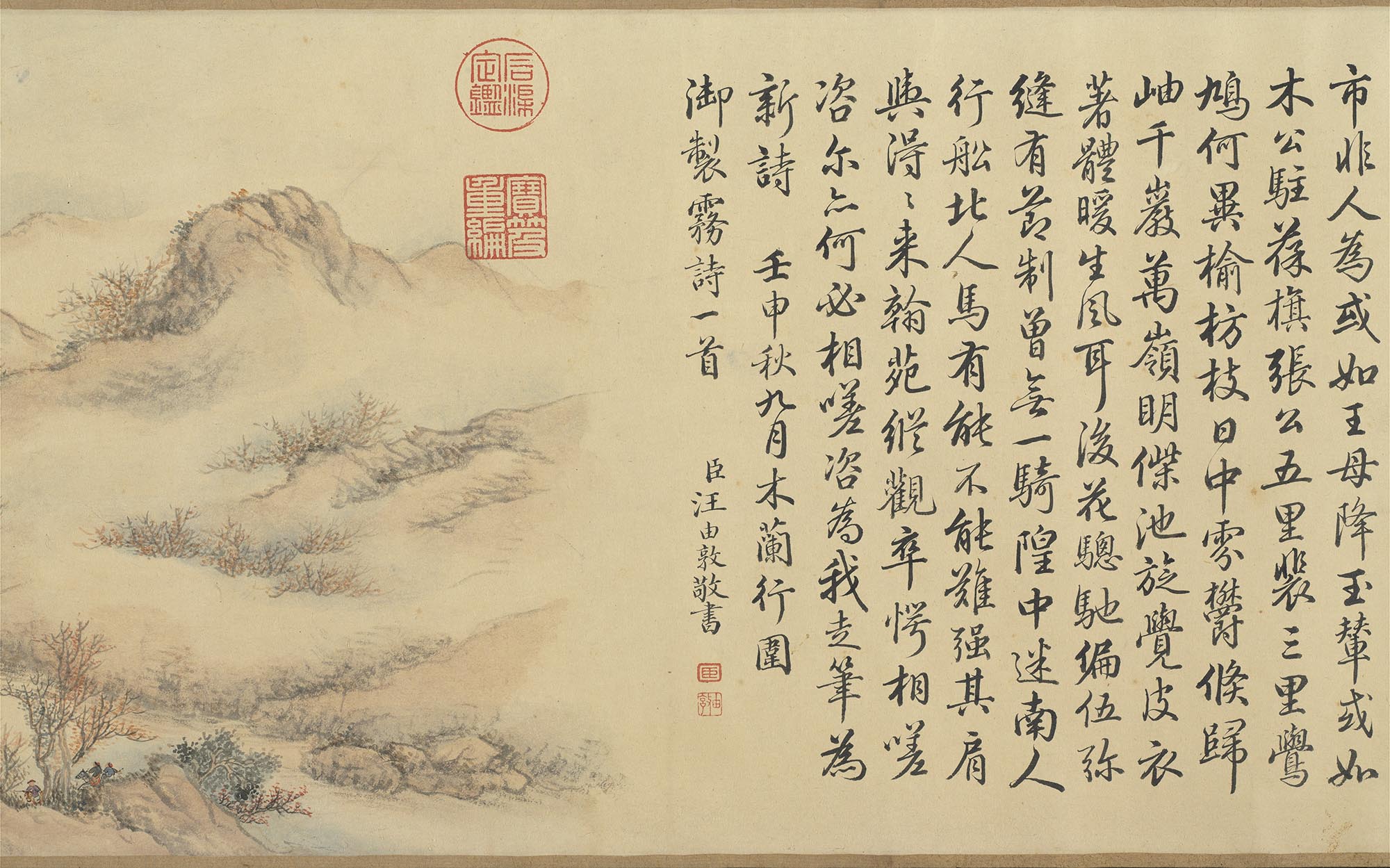

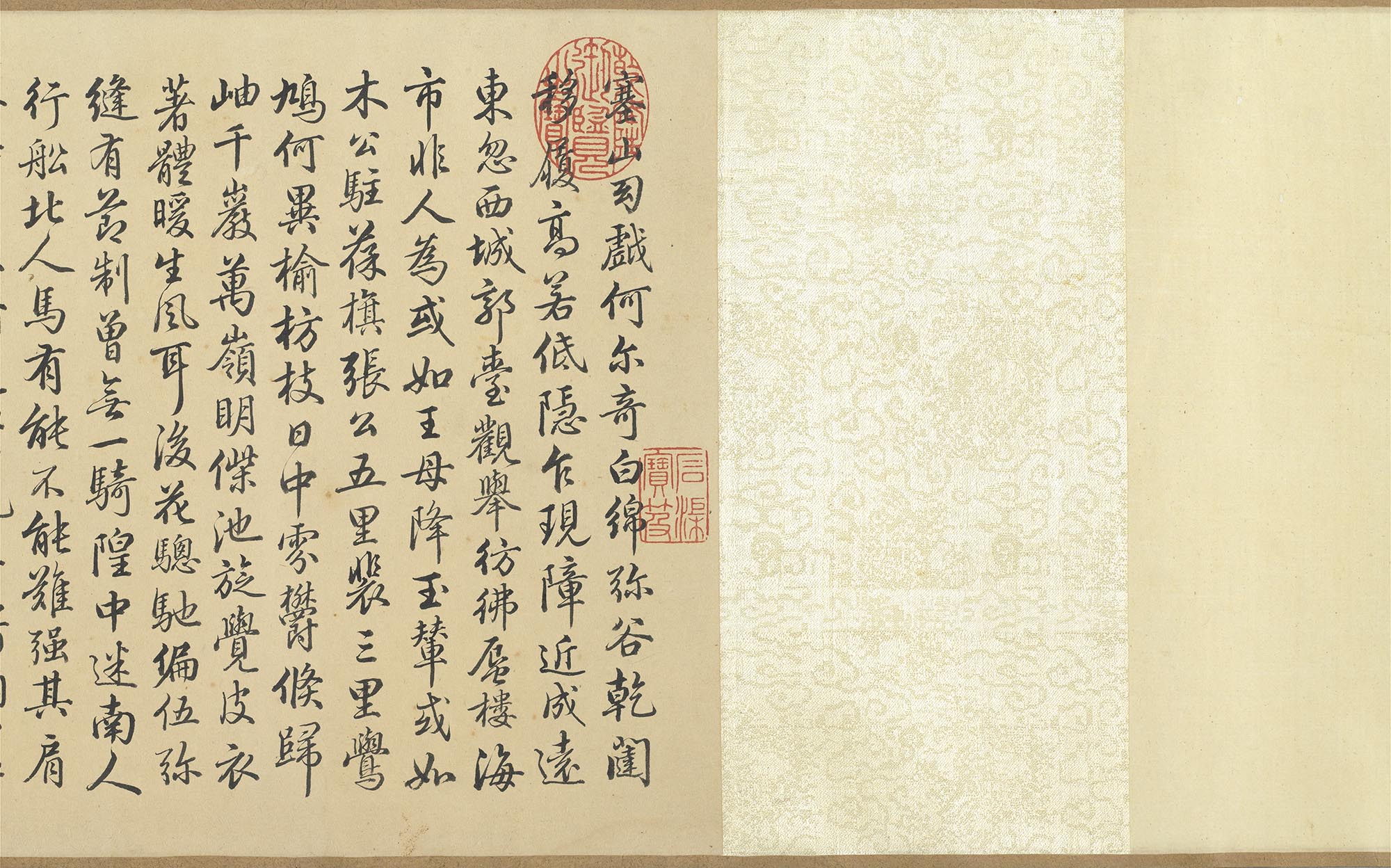

Poem on the Mist-covered Mount Saishan and Mulan Hunting Ground, written by Emperor Qianlong

- Response poems written by Wang Youdun and Jiang Pu, illustrated by Jiang Pu, Qing dynasty

- Qianlong reign (1736-1795), Qing dynasty

This long scroll contains a poem written by Wang Youdun (1692-1758) by copying Emperor Qianlong's original poem "Fog" released in 1752. "Fog" was also made into a painting by poet/painter Jiang Pu (1708-1761). Behind the painting are two poems, one written by Wang and the other Jiang. The contrast between the officials reciting poems and the hunting scene depicted in the painting creates a stark contrast between civil and military atmosphere. "Fog" details a scene of the imperial hunt team arriving a hunting ground one early morning and encountering a heavy mountain fog. Judging from the small number of hunting teams illustrated in the painting, this was a time when the emperor led two to three hundred people to a pre-hunting activity called "small encirclement" before the official hunt. In the poem, the emperor ridiculed Wang and Jiang, both of whom were born in the south, for being unskilled at horseback hunting. They subsequently resorted to writing poems for the emperor to record the hunt scenes.

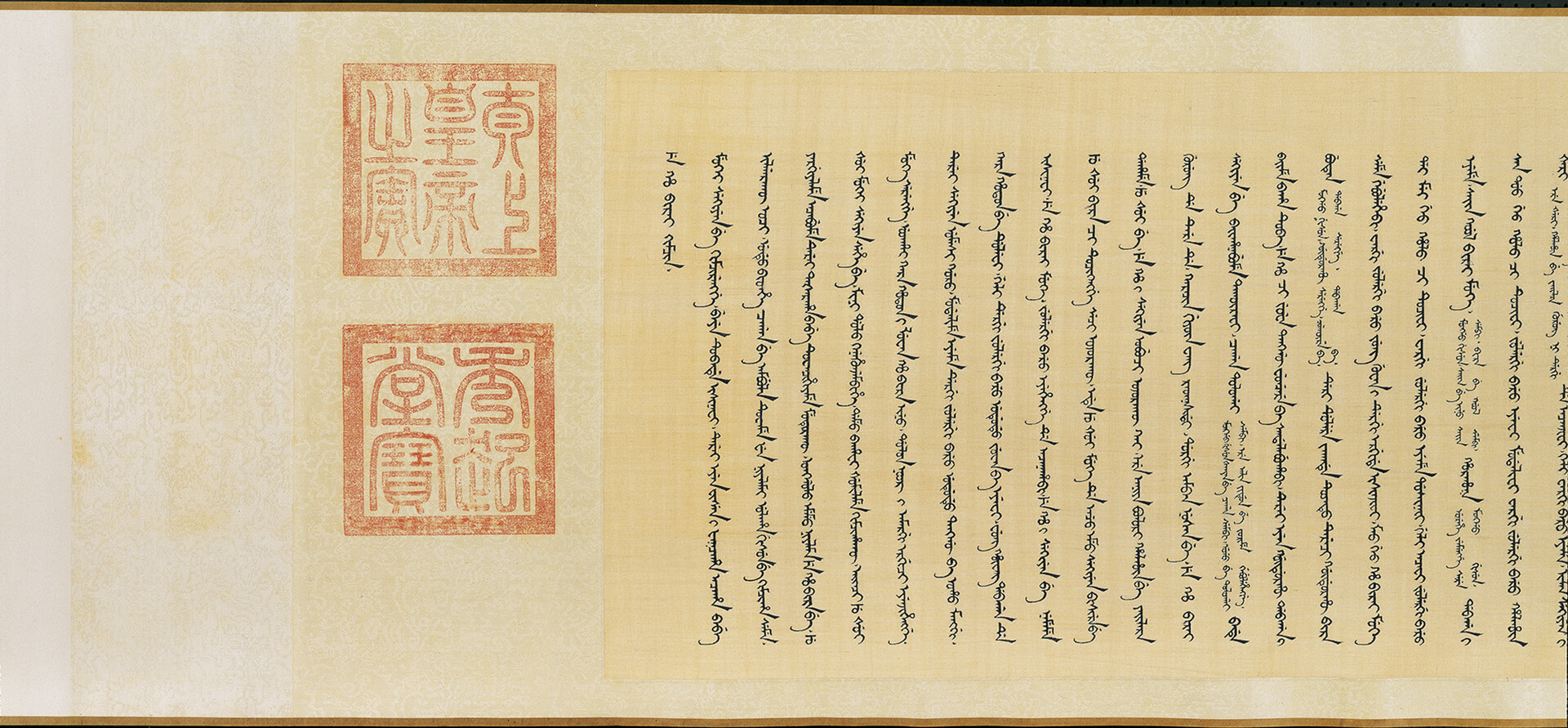

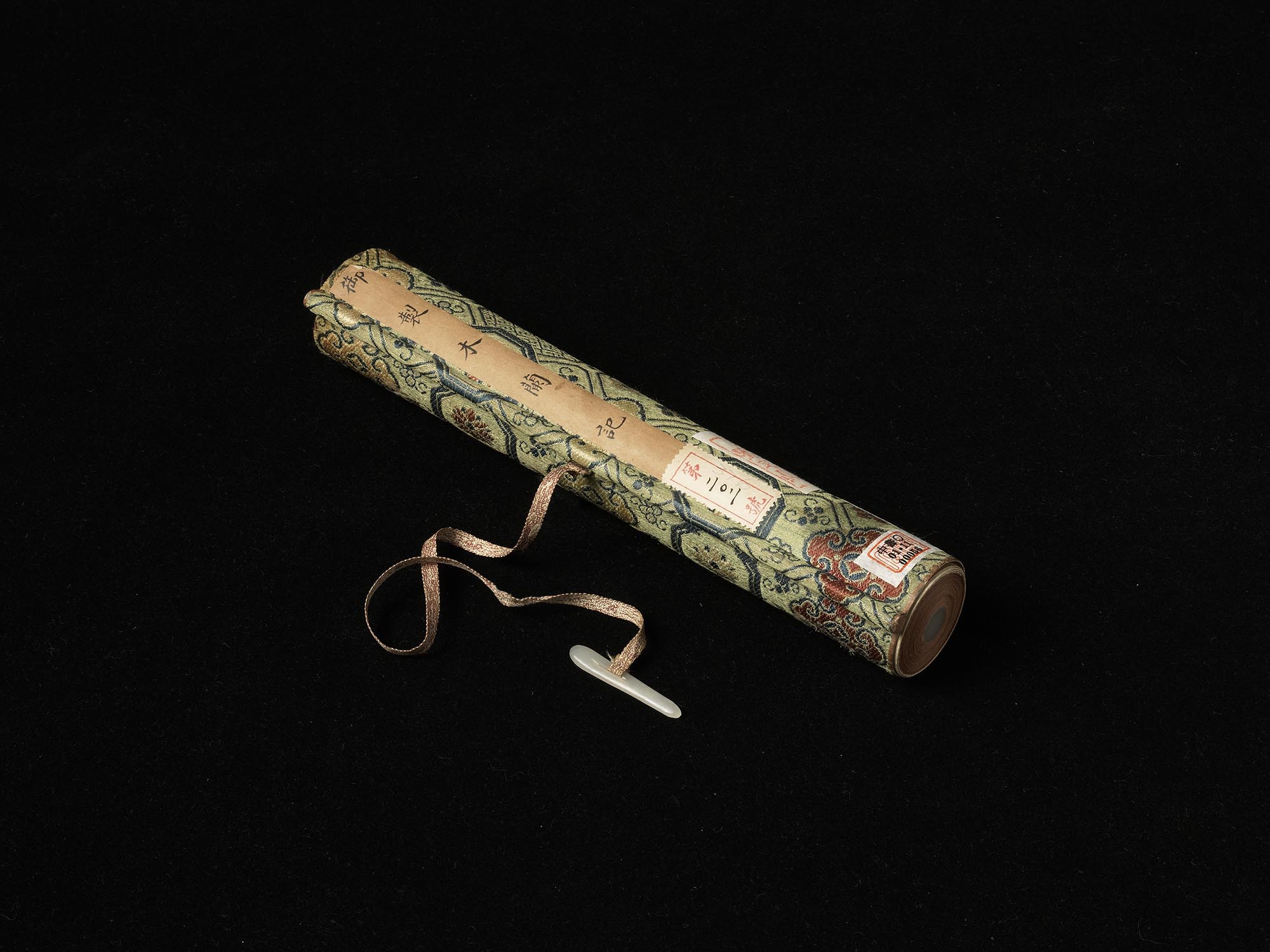

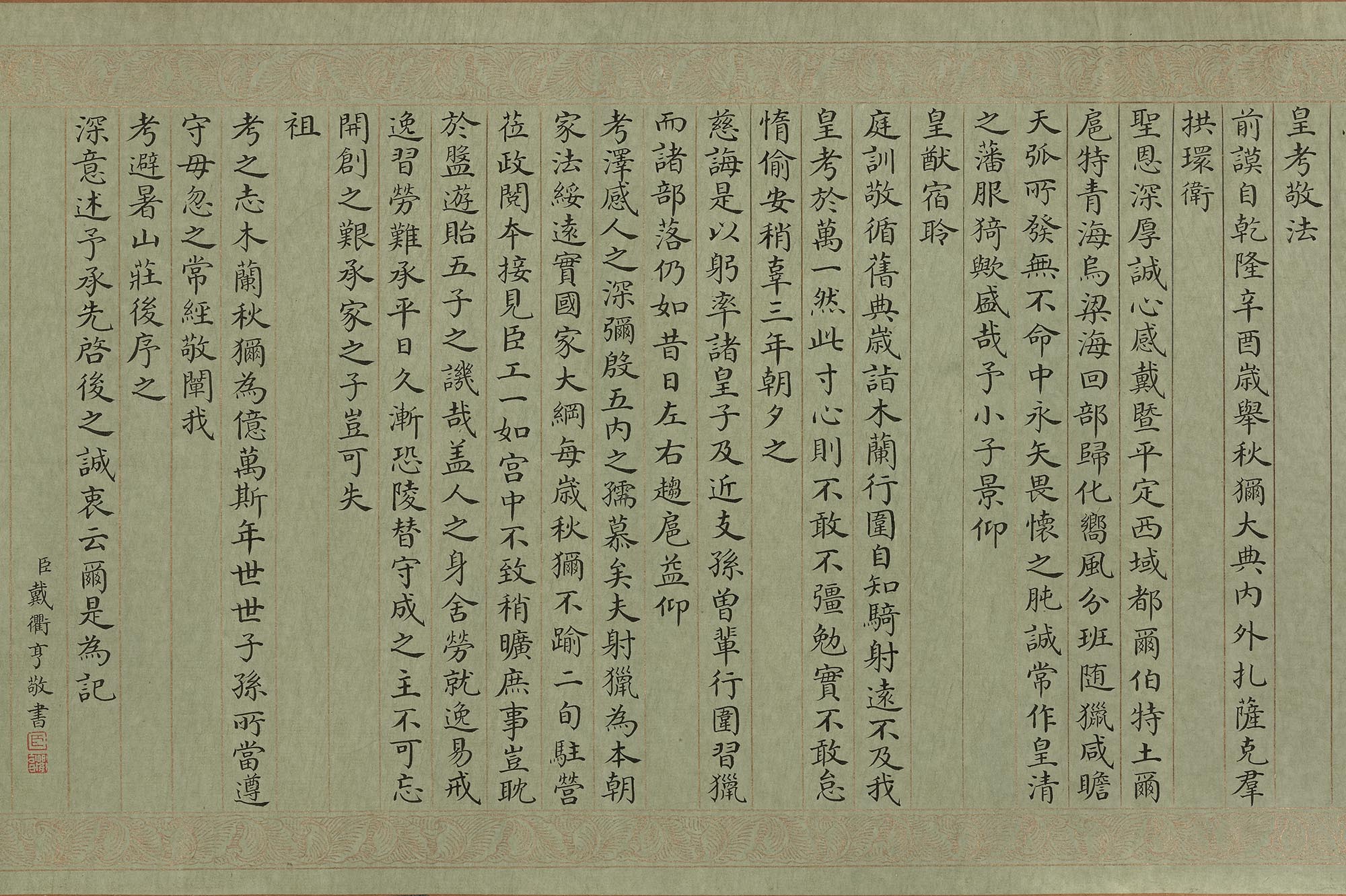

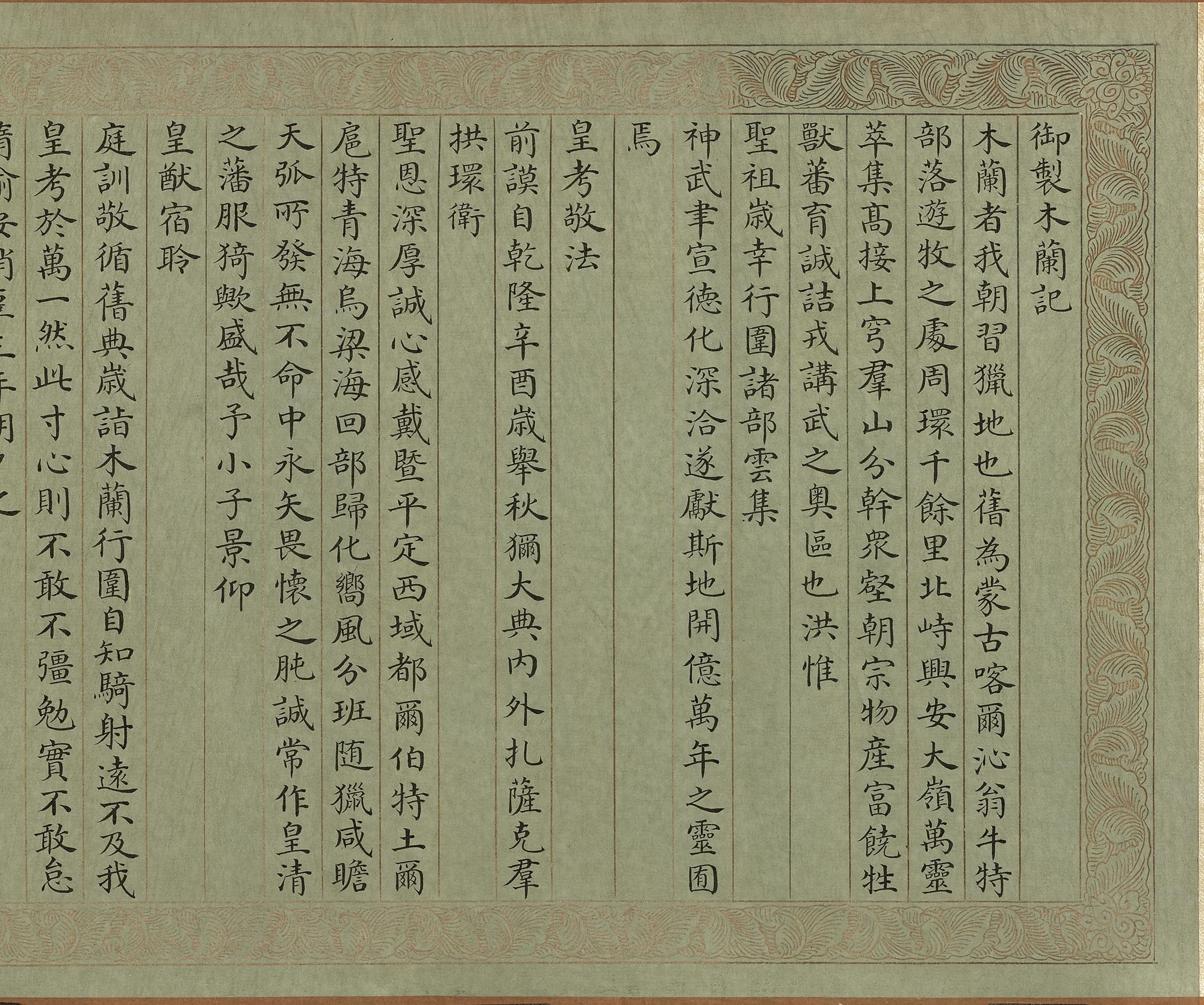

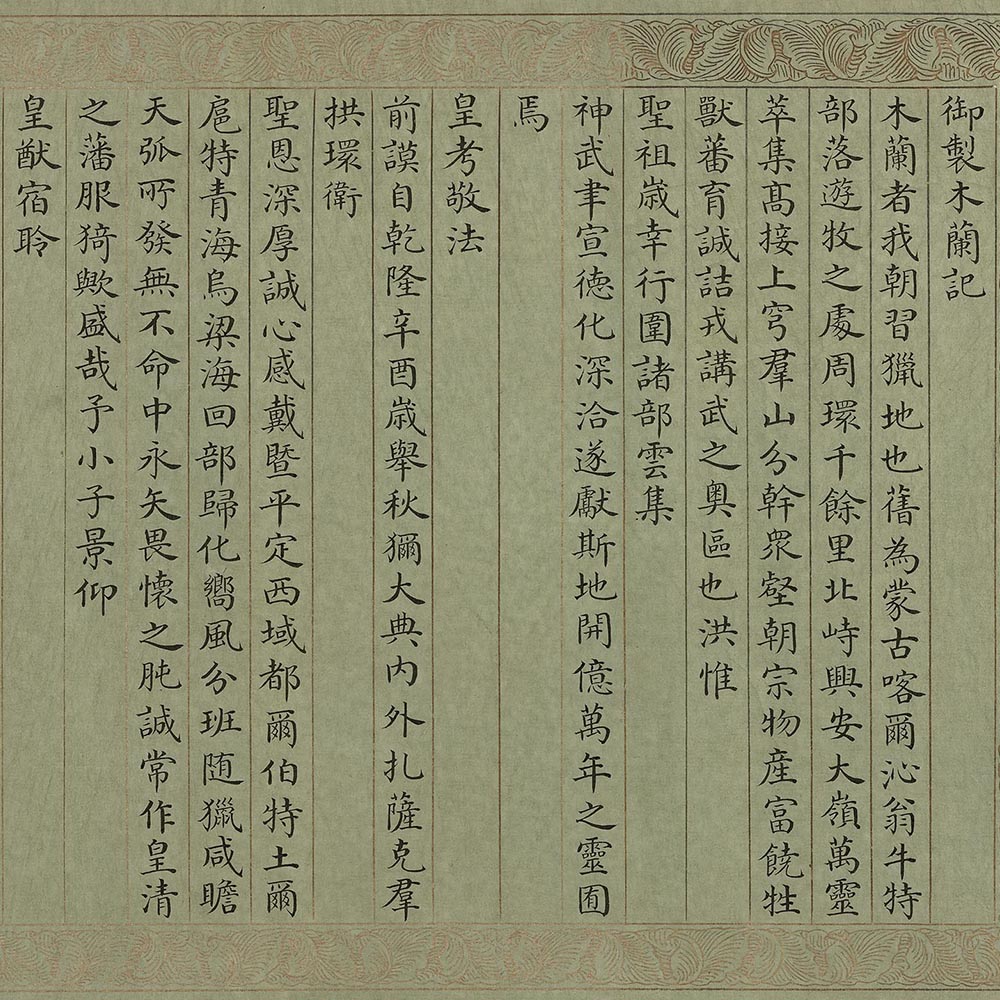

Notes on the Mulan Hunting Ground, inscribed by Emperor Jiaqing

- Written by Dai Quheng, Qing dynasty

- Jiaqing reign (1796-1820), Qing dynasty

"Notes on the Mulan Hunting Ground" is an article written by Emperor Jiaqing on the eve of a northern inspection tour to Jehol in 1807 to indicate that the imperial hunt would take place as usual. In addition to being included in the imperial anthology published by the emperor, this article was also copied into a hand scroll by Dai Quheng (1755-1811), a grand secretariat, with the hand scroll being kept inside the imperial palace. "Notes on the Mulan Hunting Ground" reveals that as the ruler of the Qing empire, the emperor must follow the old custom of going on an imperial hunt every autumn established by his father and grandfather. In addition to improving the Eight Banners martial arts drills, the emperor ordered all his retinues to promote imperial martial arts, thereby achieving imperial order. The emperor mentioned in the notes that Hunting was a family tradition of the Qing dynasty that had to be followed to ensure national order. This showed that the annual imperial hunt of the Qing dynasty was carried out to follow the tradition as well as to bring Manchurian and Mongolian princes, dukes, and nobles together to stabilize the northern defense.