A Glimpse into the Lives of Khubilghans

The Gelug lineages of khubilghans were mostly formed during the Qing dynasty. They were active not only in Tibetan regions, but also in Outer and Inner Mongolias; even the capital of Beijing had eight important Khutukhtus based there. The khubilghans in different regions played different roles and exerted varying levels of influence. The important ones endorsed by emperors were more than religious teachers; they were strongly influential on the political and economic development of their regions and were effectively preeminent politico-religious leaders. This section showcases a variety of objects giving an overview of the khubilghans' personal lives as well as their religious and political work during the Qing dynasty. The Tibetan Buddhist artifacts housed in the Qing court also offer a glimpse into the deep influence of khubilghans on the faith of the Qing imperial household.

Religious Rituals and Assemblies

Religious rituals in the Qing court followed set rules and involved a variety of religious implements and musical instruments. Some of these objects came from the Tibetan region, while others were replicas made by workshops of the Qing Imperial Household Department.

Khaṭvāṅga

- Made in Tibet, Qing dynasty (1644-1912)

The khaṭvāṅga, or heavenly club, derived from the staff used by early Tantric yogis in India (a Brahmin skull mounted on a wooden staff). Later on, the khaṭvāṅga became one of the hand attributes of the consort, goddess, or Ḍākinī. It symbolizes the ultimate bodhicitta: the perfect union of great bliss and emptiness. The khaṭvāṅga is a complex object; it consists of a shaft crowned with a crossed-vajra, a vase, a freshly severed human head, a decaying head, a dry skull, and a surmounting vajra.

The crossed-vajra symbolizes the four purified elements, the four types of activities, the four immeasurables, and the four doors to liberation; the vase with its nectar represents the attainment of wisdom; the three impaled heads represent the eradication of the three poisons (ignorance, attachment, and aversion), and the surmounting vajra symbolizes the sixth element of wisdom. This gilt-silver khaṭvāṅga has a shaft inlaid with turquoise rings and a ribbon with gold embroidery decorated with pearls, coral beads, and sapphire pendants on two ends. The use of the finest materials is befitting for a ritual object used in the imperial court.

Pair of human tibia trumpets with brass mounting

- Made in Tibet, Qing dynasty (1644-1912)

The tibia trumpet is a bored horn mostly fashioned from the thighbones of women who died in miscarriage. The mouthpiece is either bound with copper wire or encased in a metal ferrule. The trumpet is said to be able to produce sounds that are pleasing to all wrathful deities and yet are terrifying to all evil spirits and demons. Tantric practitioners such as yogis and siddhas often hold it as a hand attribute.

One of the displayed trumpets is made from a shin bone, with the mouthpiece and the opening encased in metal ferrules. The trumpet body has a metal ring, but without tone holes. The other trumpet is made from a thighbone. The mouthpiece is encased in a bronze ferrule decorated with lotus petal patterns, and the opening is decorated with patterns of dragons with their mouths wide open. It is a ritual object unique to Tibetan Buddhism.

Hook

- Qing dynasty (1644-1912)

The hook was originally used to control and tame wild elephants. In Buddhism, the "wild elephant" is a metaphor for the untamed human mind. The hook is often used together with a noose: deities hold the hook in their "method" right hand to trap or tame the evil karma of sentient beings and steer them towards the path to liberation.

Ritual sword

- Produced by imperial workshop, Qing dynasty (1644-1912)

The sword is a symbol of wisdom that cuts through ignorance and obscuration. It is also a weapon used by many deities to sever and vanquish enemies and demons. The handle is usually made of gold and sealed with a pommel consisting of a five-pronged half-vajra. The double-edged blade represents the unity of relative and absolute truth, while the pointed tip symbolizes the perfection of wisdom.

Gold bumpa vase with turquoise inlay

- Produced by imperial workshop, Qing dynasty (1644-1912)

The bumpa is a vase used in Tibetan Buddhist ceremonies such as the empowerments or Buddha-bathing festivals. It has a lidded round body and a spout, and may come with a handle. This bumpa was made from several different parts welded together. The surface is decorated using repoussé and filigree techniques and inlaid with turquoises. The decorative patterns are mostly those of lotus, while the body and foot, as well as the upper and lower ends of the neck are decorated with lotus petal patterns. The bottom is decorated with crossed-vajra patterns, and the center of the crossed-vajra is carved with connected stylized flowers. This bumpa shows the finest craftsmanship and the most magnificent of colors.

Ivory ceremonial costume

- Produced by imperial workshop, Qing dynasty (1644-1912)

A skull headpiece adorned with the Five Dhyāni Buddhas made of ivory or animal bones and a skirt decorated with strings of jewelry are part of the costumes worn by dancing lamas at Mongolian and Tibetan festivals and rituals. This headpiece is decorated with Sanskrit letters representing the Five Dhyāni Buddhas. The elaborate skirt is embellished around the waist with dharma wheels, vajras, pendants, and bells. Both items were made in the imperial workshop and originally stored in the Yangxindian Hall, the emperor's living quarters.

Statue of Uṣṇīṣa Sitātapatrā

- Made in Tibet, late 18th century

- Collection of the Ga-te Studio

This statue is the Sitātapatrā-dhāraṇī in the form of a deity. Followers believe that reciting the Sitātapatrā-dhāraṇī will ward off disaster and disease and even protect the state. This statue, with its thousand faces, arms, and legs, shows the commonest iconography. The three main heads consist of a wrathful form in the middle and two peaceful forms either side. The five-pointed crowns on their heads are missing. The thousand faces, more than 20 layers high, are shaped like a stūpa.

The right hand of the main arm holds a dharma wheel, while the left hand holds the deity's most identifiable feature, a white parasol that wards off all karma. The other hands are arranged in a fan pattern. The deity wears a splendid robe carved with the eight auspicious symbols, including two golden fish and a conch shell. Beneath her thousand feet are the sentient beings under her protection, and behind her blazing flames.

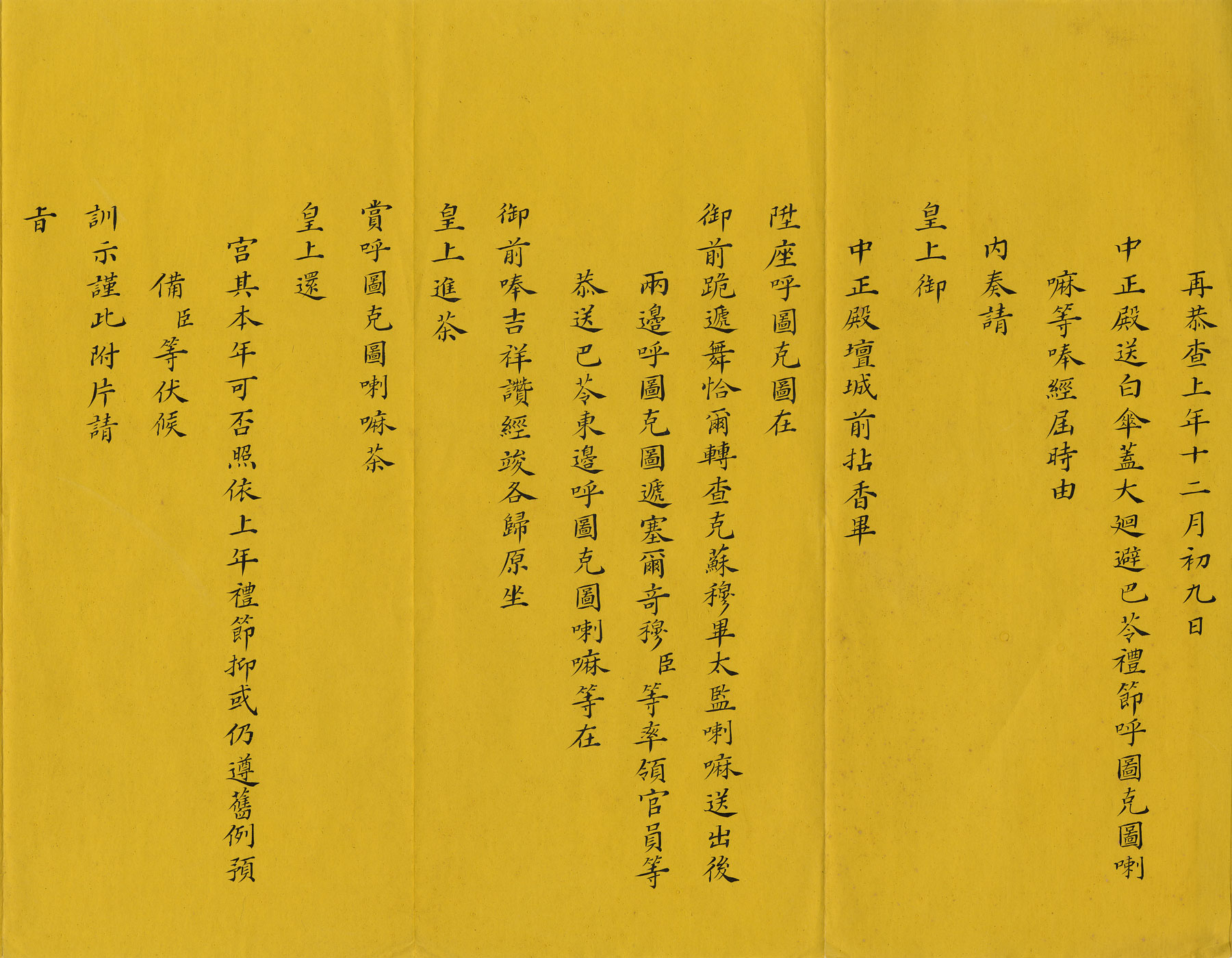

Palace memorial enquiring if the Uṣṇīṣa Sitātapatrā obstacle-removing ceremony at Zhongzhengdian Hall should follow previous year's example or old procedures and terms

- Xianfeng reign (1850-1861), Qing dynasty

In the 36th year of the Kangxi reign (1697), the Qing government set up at the Zhongzhengdian Hall an office to take charge of Tibetan Buddhist affairs of the court. Buddhist events were routinely organized at various sites in the Hall. According to this palace memorial, the Uṣṇīṣa Sitātapatrā obstacle-removing ceremony was held on the 9th day of the 12th month every year in the Zhongzhengdian Hall. By custom, the emperor burned incense in front of the mandala and served tea and gave alms to the various Khutukhtus stationed in the capital.