The Changkya Khutukhtu of Amdo and the Jebtsundamba Khutuktu of Mongolia

The Changkya Khutukhtu was the highest-ranking khubilghan of the Gelug lineage in Inner Mongolia, Amdo (a traditional Tibetan region) and Beijing during the Qing dynasty. The title originated in the Kangxi reign (1661-1722), when the emperor conferred the title of Khutukhtu on the Second Changkya and presented him with a gold seal naming him Great State Preceptor.

The Qing dynasty saw six Changkya Khutukhtus, from the Second to the Seventh. The Jebtsundamba Khutuktu was the highest-ranking khubilghan of the Gelug lineage in Outer Mongolia during the Qing dynasty, which saw a total of eight Jebtsundamba Khutuktus, from the First to the Eighth. Losang Denpai Gyaltshan (1635-1723) was the First Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, and the title was awarded to him by the Fifth Dalai Lama (1617-1682) during his stay in Tibet studying Buddhism. In the 57th year of the Kangxi reign (1718), the emperor bestowed upon the First Jebtsundamba Khutuktu the title of Leader of the Yellow Sect in Outer Mongolia.

This section presents artifacts from the Museum's collections that relate to the Third Changkya, Rölpé Dorjé (1717-1786), who lived in the Qianlong reign (1735-1795) and is the most famous of his lineage. It also features objects that belonged to the Seventh Changkya (1891-1957) who relocated to Taiwan together with the Republican government. Included in this lineup of exhibits are his religious paraphernalia, correspondence and written works, on loan for the first time from the Ministry of Culture's Mongolian and Tibetan Cultural Center. For the Jebtsundamba Khutuktu lineage, the exhibition focuses on important documents in the Museum's collection relating to the two most influential leaders, the First Jebtsundamba (1635-1723) of the Kangxi reign and the Eighth Jebtsundamba (1869-1924) in the late Qing dynasty.

The Third Changkya Khutukhtu and Mount Wutai

As Mount Wutai was seen in both Chinese and Tibetan Buddhism as a center for the worship of Mañjuśrī, Qing emperors accorded importance to this sacred site not far from the capital. The Qianlong emperor gifted the Zenhai Monastery to the Third Changkya, and the religious leader often spent his summers there.

Poem Composed during a Visit to the Wenshu Monastery on Mount Lingjiufeng

- From fascicle 6 of of Qingding Qingliangshan Zhi (Imperially Endorsed Mount Qingliang Gazetteer)

- Compiled on the order of Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799), Qing dynasty

- Court manuscript in red-lined columns, Qianlong reign (1736-1795), Qing dynasty

Qingliangshan, or Mount Wutai, is seen as a center for Mañjuśrī worship and a sacred site for the Gelug School of Tibetan Buddhism. As the pronunciation of "Mañjuśrī" is similar to that of "Manchuria," the Qing court was much more meticulous about developing and managing Mount Wutai. The Qingding Qingliangshan Zhi documents the Qianlong emperor's six trips to Mount Wutai, and this poem was composed during his fifth visit in the 51st year of his reign (1786).

At that time the Third Changkya Khutukhtu headed a group of monks to greet the emperor, and accompanied him in worship at the Wenshu Monastery. However, less than a month after Qianlong returned to the capital, the news of the Third Changkya's passing arrived, and this poem became a record of their last interaction.

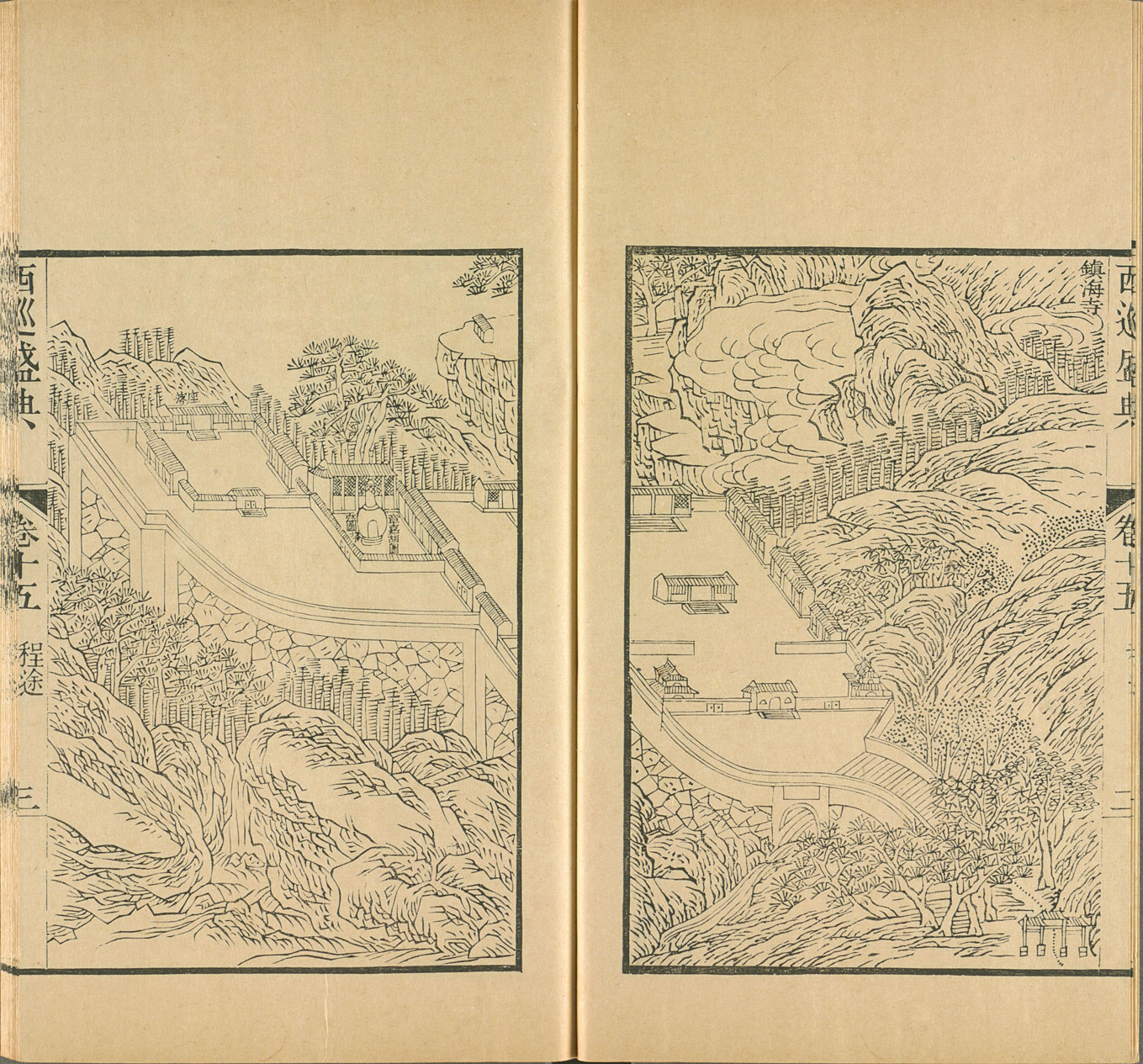

Illustration of the Zenhai Monastery

- From fascicle 15 of Xixun Shengdian (Accounts on Imperial Favours Bestowed during the Western Inspection Tours)

- Compiled on imperial order by Dong Gao (1740-1818) et. al., Qing dynasty

- Moveable-type printed edition by the Imperial Printing Office at Wuyingdian Hall, Jiaqing reign (1796-1820), Qing dynasty

Mount Wutai, a site of worship for the Mongolian and Tibetan nobles and leaders of the Gelug School, played an important role in maintaining the stability of the Qing dynasty's western borders. In his "Notes on Mount Qingliang," the Jiaqing emperor (r. 1796-1820) hailed Mount Wutai as "the right arm of the capital" and "China's Tibet." The stūpa shown in this illustration of the Zhenhai Monastery was built by the Qianlong emperor to commemorate the Third Changkya Khutukhtu. It was the first monastery dedicated to the Changkya on Mount Wutai.

Statue of Vajravārāhī

- Made in Beijing or Inner Mongolia, 18th century

- Collection of the Garuda Tibetan Art Studio

Vajravārāhī is a type of Dākinī and her distinguishing feature is the sow's head above her right ear. Consort of Chakrasamvara of the Anuttarayoga Tantra, Vajravārāhī is also often worshipped on her own in kuṇḍalinī practice.

The main iconographic form of Vajravārāhī is red in color, with one face, three eyes, two arms, disheveled hair, and a wrathful expression. Naked, she wears a crown of five skulls, a variety of bone ornaments, and a necklace of 50 freshly severed human heads. A tiger skin is draped over her loins, and ribbons flutter on either side of her body. She holds a curved knife in her right hand and a kapāla filled with blood in her left. Her elbow leans upon a khaṭvāṅga (skull staff). She holds a dancer's posture, standing on a corpse. This statue accords with the deity's iconography in every detail. It is worth noting that the triangle between the corpse and the lotus pedestal should be the dharmodaya, from which Vajravārāhī emerges.

Statue of Vajrapāṇi

- Made in Inner Mongolia, 18th century

- Collection of Hung's Arts Foundation

The stocky wrathful Vajrapāṇi sits back on his right leg and stretches out the left. His right arm is raised towards the sky, the hand originally holding a vajra (missing), while the left hand held in front of the chest makes the gesture of tarjani-mudrā to ward off evil. His three round and fierce eyes, short and powerful nose, and bared teeth and protruding tongue make for a very vivid facial expression.

The bare chest is decorated with strings of jewelry, a tiger-skin skirt (fine carved lines bringing out the texture of the fur) wrapped around his waist, and small snakes coiling around the wrists and ankles. While statues from Inner Mongolia tend to look rigid, this work is undoubtedly a rare and fine specimen: the gilding is sumptuous and both the curved fingers performing the tarjani-mudrā gesture and raised toes appear supple.

Statue of the Six-armed Mahākāla

- Made in Inner Mongolia, 18th century

- Private collection

The six-armed Mahākāla is the wrathful form of Avalokiteśvara. Originally a deity of the Shangpa Kagyu lineage and the most unique, important protector of the Gelug School, he is depicted in a walking pose, and in pictures showing Tsongkhapa (1357-1419) compelling demons he is portrayed as a warrior. The six-armed Mahākāla is typically black in color, with flying hair, a single face, three wide-open eyes, fangs bared, a lolling tongue, and six arms. The main arms hold a flaying knife (now missing) in front of the chest and a kapāla filled with blood, while the other four arms hold skull prayer beads, a trident (now missing), a hand-drum, and a lasso. Adorned with a crown of five skulls, snakes, and a necklace of freshly severed heads, the six-armed Mahākāla also wears a tiger-skin loin cloth and is holding an elephant skin in his two upper arms. He stands on the Hindu deity Ganesha, which holds a kapāla and a radish.

This large statue has a relatively thin copper body. Items including the crown of five skulls, earrings, kapāla, and elephant skin were manufactured separately and then attached to the statue. The chasing and repoussé technique is a strong feature of inner Mongolian statues.

Statue of Palden Lhamo

- Made in Inner Mongolia or Beijing, 18th century

Revered by the Gelug School, Palden Lhamo is the only female dharmapāla of the Anuttarayoga Tantra of Tibetan Buddhism, and is typically depicted crossing a sea of blood riding side-saddle on a mule. This statue has one head and two arms, and in accordance with ritual convention, she brandishes a club in her right hand and holds a skull cup full of blood in her left.

The stylized mountains on the pedestal (representing a sea of blood) show that this statue was produced in Inner Mongolia or the Beijing area. What makes this statue a rarity is that the copper body is painted. Large statues with partly painted copper bodies are occasionally seen in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in Gansu, Inner Mongolia, and Beijing, but they have often been washed excessively because their colors shed or because they are blackened by smoke. This small-size statue has retained its colors, possibly because it was long wrapped in fabric.