Propagation of the Kerchief-box Editions

Following Prince Xiao Jun's rendition of "Five Classics in a Kerchief-box," Xiao Yi),

Emperor Yuan of the Liang dynasty, also produced small-sized texts. An avid

bibliophile, he had been collecting books for four decades and was able to assemble

some 80,000 juan (fascicles) of texts. In the Jushu (Assembling Books) chapter of his

work Jinlouzi (Master of the Golden Chamber), the emperor said, "I had Kong Ang

transcribe the Qian Hanshu (History of the Former Han), the Hou Hanshu (History of the

Later Han), the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian), the Sanguozhi (Records of the

Three Kingdoms), the Jinyangqiu (A Chronicle of Jinyang), the Zhuangzi (Master Zhuang),

the Laozi (Daode Jing), the Zhouhoufang (Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies),

and the Lisao (Sorrow After Departing) into a total of 634 juan (fascile). These texts are stored

in a kerchief-box, and the characters are extremely fine and small." This record

indicates that Xiao Yi had a vast collection of books, and many of which were

transcribed in small characters. It is obvious that the kerchief-box editions made by

Xiao Yi surpassed Xiao Jun’s renditions in both scope and quantity, encompassing not

only the Confucian classics studied by the literati, but also other types of books.

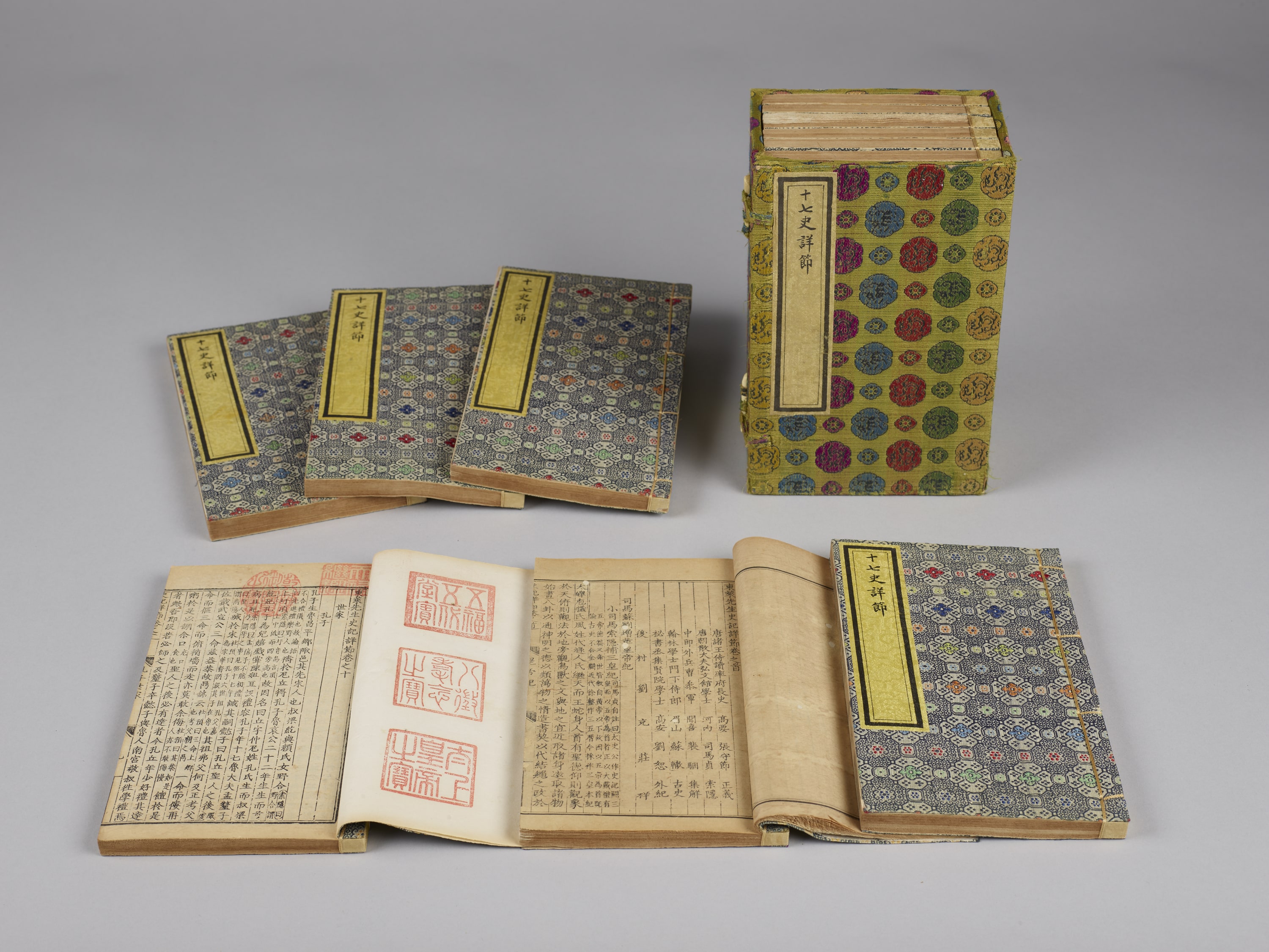

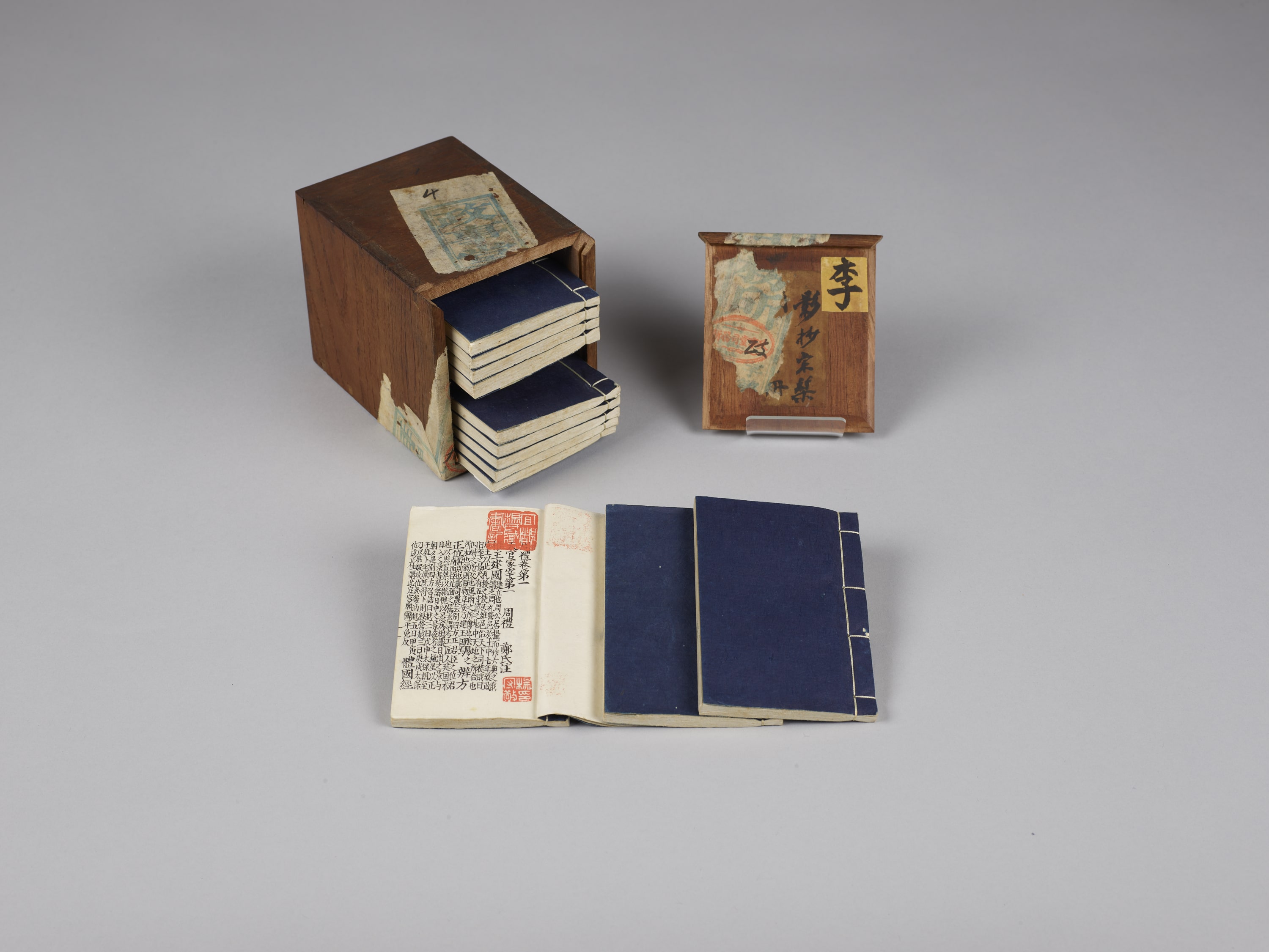

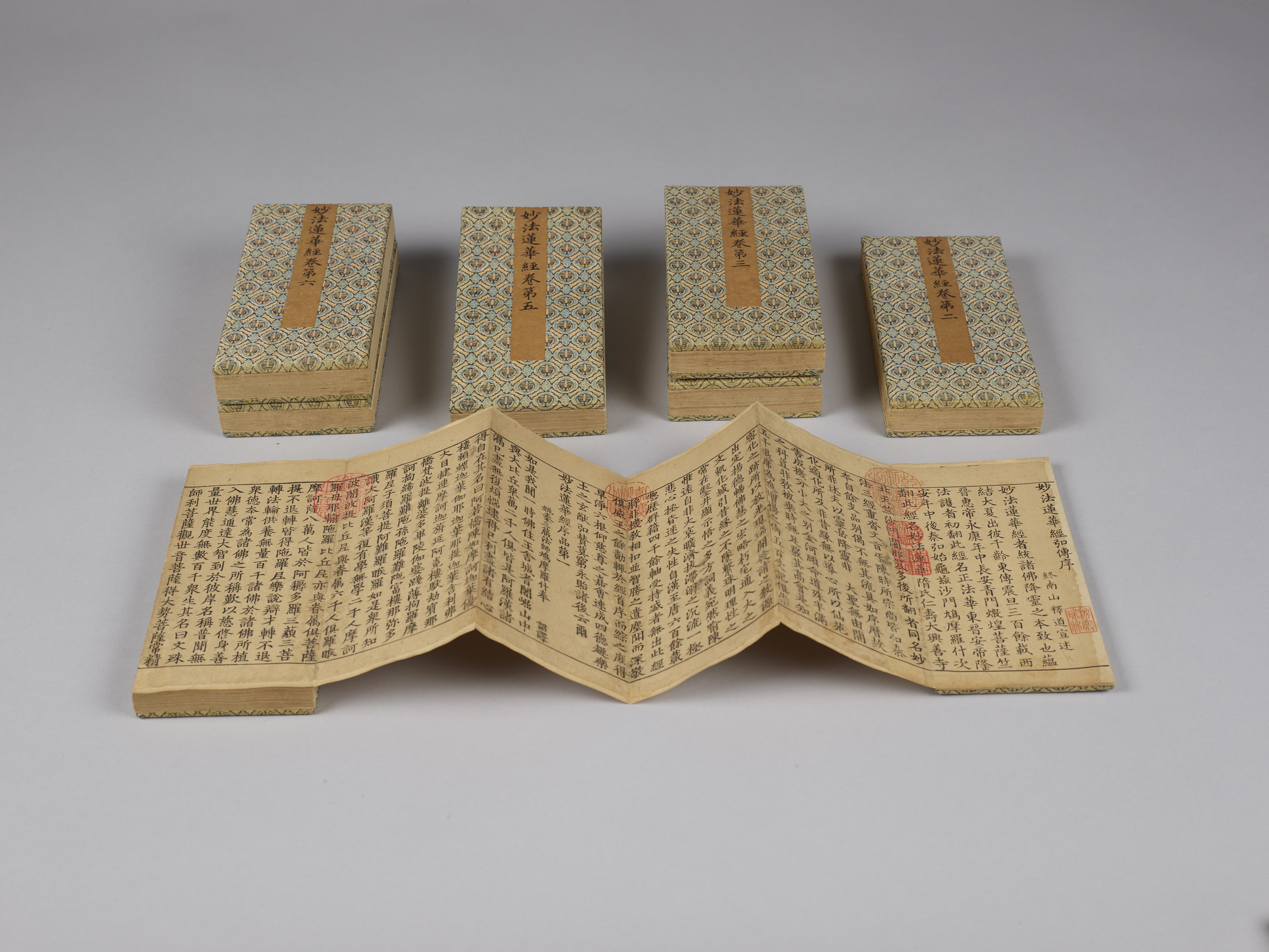

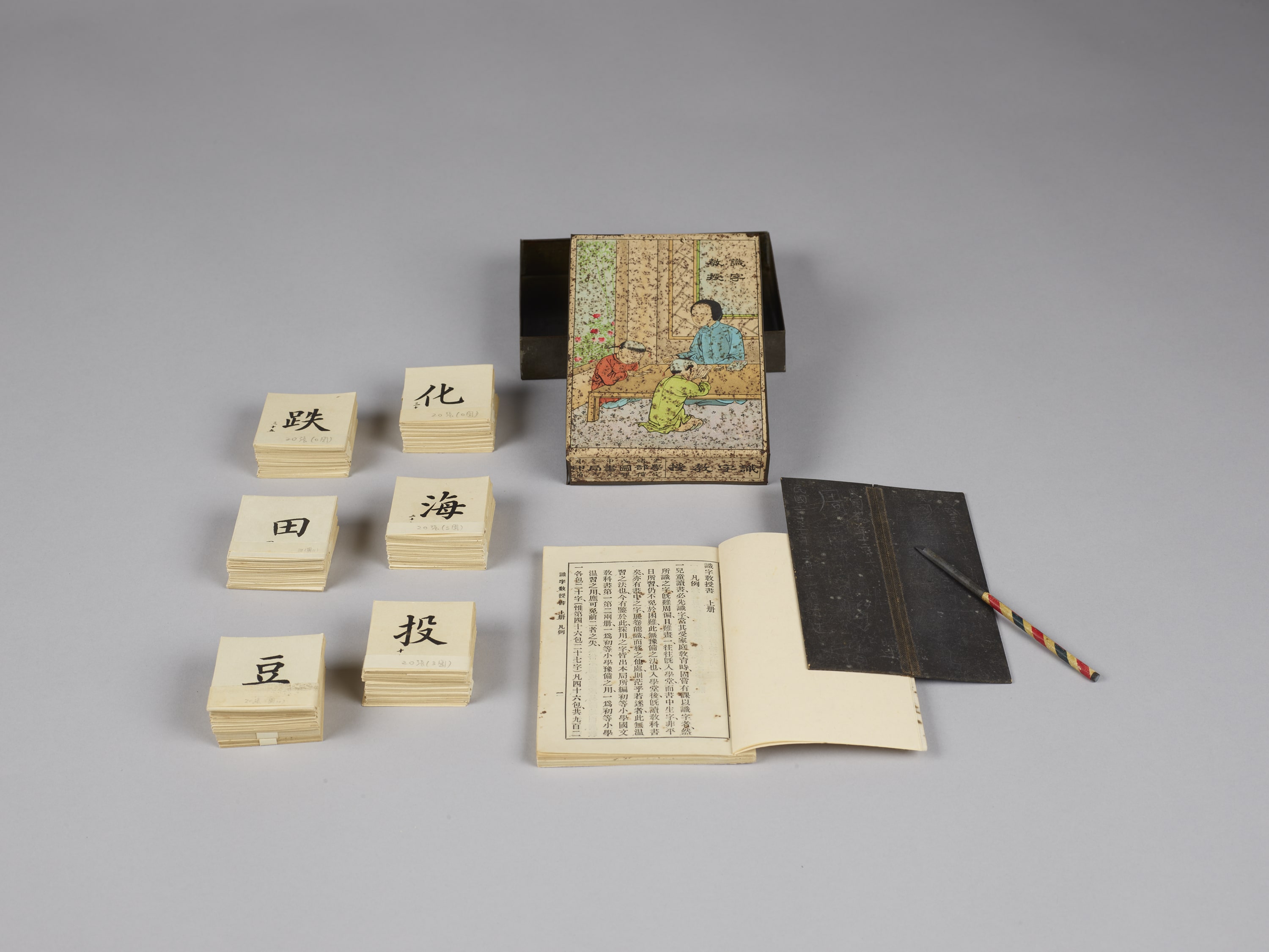

The kerchief-box edition started to flourish and received wide circulation roughly

around the time the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127) gave way to the Southern Song

dynasty. At that time, woodblock printing was already facilitating the publication and

circulation of books. On the other hand, commercial print houses also published many

classics, histories, collections of masters, imperial examination preparation

materials, contemporary texts, lexicons, rhyme books, and literary collections. The

kerchief-box editions released by the print houses, commonly known as "small copies,"

"small volumes," or "small booklets," did not have uniform dimensions, but were

considerably smaller than regular books. Their ease of carriage and circulation and

their low cost contributed to their widespread popularity in the market, and went on to

influence the woodblock prints in the Yuan (1271-1368), Ming, and Qing dynasties. The

introduction of lithography and stereotypography in the late Qing dynasty led to the

printing of a large number of small-sized lithographic and stereotypographic editions,

providing literati and readers with more purchase options.