The development of Chinese painting history can be compared to a marvelous symphony. The styles and traditions of figure, landscape, and bird-and-flower painting formed themes that continue today to blend into a single piece of music in Chinese art. Painters throughout the ages have made up this "orchestra," composing and performing many movements and variations within this long tradition.

During the Six Dynasties period (222-589) to Tang dynasty (618-907), the foundations of figure painting were gradually laid by such important artists as Gu Kaizhi and Wu Daozi. Modes of landscape painting then took shape in the Five Dynasties period (907-960) with distinctions based on geography. For example, Jing Hao and Guan Tong depicted monumental peaks to the north, while Dong Yuan and Juran represented water-filled scenery of hills to the south in Jiangnan. In bird-and-flower painting, the noble Tang court manner was passed down in Sichuan through the style of Huang Quan, contrasting with the more rustic one of Xu Xi in the Jiangnan area.

Also in the Song dynasty (960-1279), landscape painters such as Fan Kuan, Guo Xi, and Li Tang developed new manners based on previous traditions. The transition in compositional arrangement from grand mountains to intimate scenery also reflected in part the political, cultural, and economic shift to the south at the time. Guided by the taste of the emperor, painters at the court academy focused on observing nature combined with "poetic sentiment" to reinforce the effect of both formal likeness and personal expression. Painters were continually inspired by the things around them, leading to the depiction of technical and architectural elements, for example, in the late eleventh century. The focus on poetic sentiment naturally brought together the "Three Perfections" of painting, poetry, and calligraphy in the same work (often as an album leaf or fan) by the Southern Song period (1127-1279). Scholars earlier in the Northern Song era (960-1126), however, thought that painting as an art had to go beyond just the "appearance of forms" in order to express their ideas and cultivation. This became the foundation for a movement known as literati painting.

One of the goals of Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) literati artists, including Zhao Mengfu and the Four Yuan Masters (Huang Gongwang, Wu Zhen, Ni Zan, and Wang Meng), was to revive the antique styles of the Tang and Northern Song as a starting point for personal expression. This variation on revivalism transformed old "melodies" into new and personal tunes, some of which developed into important traditions of their own in the following Ming and Qing dynasties. As in poetry and calligraphy, personal cultivation was often an integral part of expression in painting.

Starting in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), painting became increasingly distinguished by local schools forming important clusters in the history of Chinese art. The styles of "Wu School" artists in the Suzhou area, for example, were based on the cultivated approaches of literati painting by the Four Yuan Masters. The "Zhe School," on the other hand, consisted mostly of painters from the Zhejiang and Fujian areas; also active at court, they created a direct and liberated form of monochrome ink painting based on Southern Song models.

The influential late Ming master Dong Qichang and the Four Wangs (Wang Shimin, Wang Jian, Wang Hui, Wang Yuanqi) of the early Qing dynasty (1644-1911) adopted the literati goal of unifying ancient styles into a "grand synthesis" to render the mind and nature with brush and ink. The result was the "Orthodox School" supported by the Manchu Qing emperors. The court also took a keen interest in Western painting techniques (brought by European missionaries) involving volume and perspective, which became known to and used by some Chinese painters to create a fusion style. Outside the court, the major commercial hub of Yangzhou became a center for "eccentric" yet professional painters who led the trend toward individualism. It spread to Shanghai as well, where the styles of artists were inspired by "non-orthodox" manners, which themselves became models for later artists.

Thus, throughout the ages, one of the hallmarks of Chinese painting has been the pursuit of individuality and innovation within this traditional "symphonic" heritage. The exhibition here represents a selection of individual "performances" from the Museum collection to allow viewers to appreciate and understand Chinese painting. Arranged in chronological order, these works provide an overview of some major traditions and "interludes" in Chinese art history.

Introduction

Selections

Late Greenery of Autumn Mountains

- Guan Tong (fl. early 10th c.), Five Dynasties period

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 140.5 x 57.3 cm

This painting has no seal or signature of the artist but is ascribed to the Five Dynasties artist Guan Tong on the basis of a colophon written in 1649 by Wang Duo (1592-1652) in the early Qing. Guan Tong's landscapes are known for their solid rock forms, serrated mountain peaks, and lush forests, elements of which can be seen in this work. However, the brushwork and composition here suggest a slightly later date in the early to middle Northern Song period, circa the eleventh century.

The most interesting aspect below the layered peaks here is the massive rock form that appears in the middle. A path appears here and there behind the rocks, creating a serene valley inaccessible to outsiders. This is perhaps the artist's intended effect in an attempt to fathom the depths of the majestic landscape. This painting has been remounted several times in the past and retouched as well. For example, mountain rocks in the upper right and on the massive cliff, and even the buildings on the peaks, are all later additions.

Mending a Cassock

- Attributed to Liu Songnian (fl. late 12th-early 13th c.), Song dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 141.9 x 59.8 cm

This painting depicts two Buddhist monks sitting on a meditation platform. The elder one focuses on mending a robe as the other behind him looks on and clasps his knees. Two attendants are shown standing in the area behind the screen preparing tea. The figures' expressions are lively and natural, the brushwork for the drapery lines also fluid and powerful. The artist's signature in the lower left reads, "Reverently presented by Liu Songnian, Recipient of the Golden Belt and Painter-in-Attendance at the Painting Academy." It and his seal, however, are both spurious.

Paintings of lohans (Buddhist worthies) from the Song and Yuan dynasties often show monks in daily activities. This scroll with a monk mending clothes also falls into this category of lohan painting. Liu Songnian was a Southern Song court painter active into the early thirteenth century, his three "Lohan" paintings in the National Palace Museum collection being most representative of his work. This hanging scroll, however, differs in style, suggesting the hand of a late Southern Song or Yuan dynasty artist to which Liu's name was added.

Rongxi Studio

- Ni Zan (1301-1374), Yuan dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink on paper, 74.7 x 35.5 cm

Ni Zan painted this work in 1372 during the early Ming dynasty, two years later inscribing and presenting it to the physician Pan Renzhong. By the early Ming, Ni Zan had already given up his family property and led a life of wandering around the waters of the Lake Tai area for almost twenty years following the chaos of the late Yuan.

This painting depicts the scenery of a river and its two banks. The foreground slope appears slightly wider, the empty kiosk making it look even sketchier. The angular texture strokes, derived from the Jing-Guan (Jing Hao and Guan Tong) style of the tenth century, blur the outlines of the landscape forms. They also transform the moist and dense strokes of Dong Yuan, another tenth-century artist, and create a kind of pure and clean style. More than twenty years earlier, Huang Gongwang (1269-1354) pointed out the appearance of Dong Yuan's style in Ni Zan's "Six Gentlemen," now more refined and with a tempered visual vocabulary.

Hunting on Horseback

- Attributed as anonymous, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 39.4 x 60.1 cm

This small hanging scroll shows several people on horseback, the skies above dark and the mountains in the background glistening. The bright colors of autumn foliage, as well as the opulent clothing of the figures, add a rich yet serene quality to the atmosphere. The composition follows that of hunting scenes often seen in Song and Yuan dynasty painting, but the mountains reveal the method of depicting snowy landscapes in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

In the painting, two figures are riding side by side, and both wear red clothing with a yellow outer garment. One of them is bearded and looks like the Ming emperor Xuanzong (1399-1435), while the woman with makeup next to him is similar to a court lady. Following behind are two female attendants on horseback, each leading another horse. The exact meaning of the scene, however, awaits further study. This work had been attributed to a Yuan dynasty artist in the past, but the method of painting is quite similar to "Emperor Xuanzong Hunting" in the Beijing Palace Museum, suggesting a product of the Ming court instead.

Snowy Landscape and Birds

- Lü Ji (fl. 1439-1505), Ming dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 169.6 x 90.5 cm

Lü Ji (style name Tingzhen, sobriquet Yaoyu [or Leyu]), a native of Yinxian in Zhejiang (modern Ningbo), served up to Commander in the Imperial Bodyguard (a military unit providing sinecures for court painters) at the Renzhi Hall during the Hongzhi reign (1488-1505). He early studied the bird-and-flower painting of Bian Wenjin and later emulated the paintings of famous Tang and Song dynasty artists. He integrated the "fine line" and "sketching" techniques to achieve marvelous results.

In this desolate scene after a snowfall, the river and sky appear dark and gloomy, the effect attained by ink washes. Wild ducks are shown dozing on the bank as they huddle against the cold to keep warm. Sparrows and a dove are perched on the branches of the wintry willow tree. Lü Ji was able to effectively describe the chill of this cold winter scene with brushwork uncontrived and simple. Compared to some of his other works, this painting possesses an even greater sense of archaism.

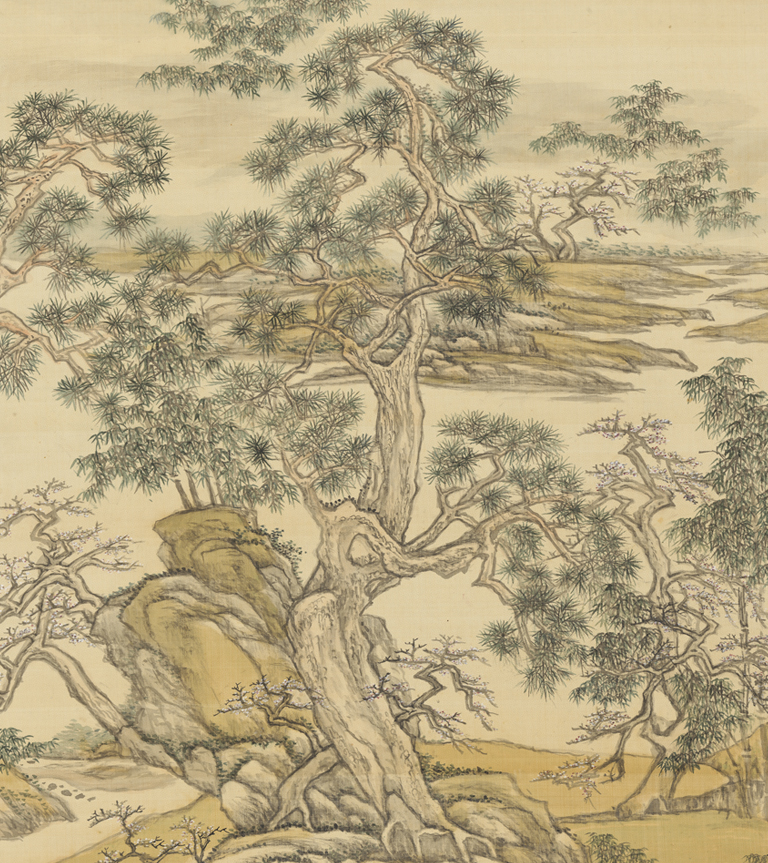

Imitating Li Tang's "Spring Trees of a Myriad Years"

- Wang Yuanqi (1642-1715), Qing dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 106.1 x 53.3 cm

Wang Yuanqi (style name Lutai) was the grandson of the famous early Qing artist Wang Shimin. Receiving instruction in the art of landscape painting from his grandfather since childhood, he went on to become a Presented Scholar in 1670. He was promoted in the seventh month of 1705 to Hanlin Expositor-in-Waiting and in the fourth month of the following year to Hanlin Reader-in-Waiting. In the lower left, he signed the work as "Respectfully painted and submitted by Your Servant, Wang Yuanqi, Hanlin Expositor-in-Waiting," indicating it was done during this interval.

This painting deals with the subject of an old pine, which stands tall and rugged in the center of the composition against a level-distance background. The arrangement differs from Wang's usual technique of piling up mountains seen in his other works, giving the painting surface here a more expansive effect. This scroll reportedly imitates that of the Southern Song artist Li Tang (ca. 1070s-1150s), but the low horizon and suggestion of a vanishing point indicate that Wang Yuanqi may have relied more on the techniques of Western painting practiced by court artists at the time.

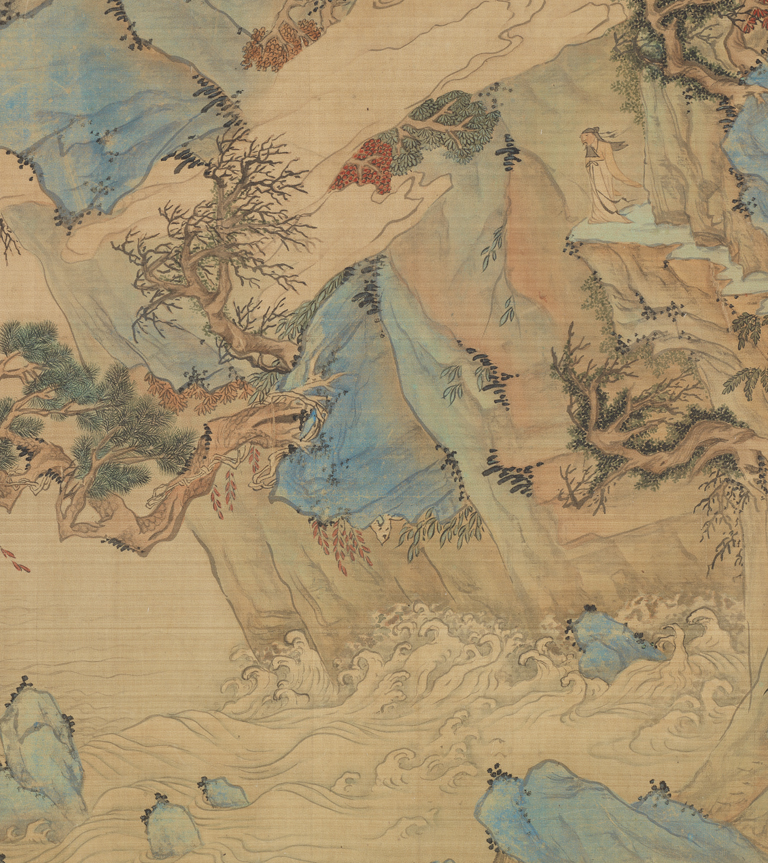

After Zhao Bosu's "Latter Ode on the Red Cliff"

- Wen Zhengming (1470-1550), Ming dynasty

- Handscroll, ink and colors on silk, 31.5 x 541.6 cm

Wen Zhengming originally had the name Bi and style name Zhengming, by which he became known. This painting is based on Su Shi's famous "Latter Ode on the Red Cliff" and divided into eight sections depicting Su and his two friends bringing fish and wine to revisit the Red Cliff. The painting is done throughout with light blue-and-green coloring. Although in imitation of the Song artist Zhao Bosu (?-ca. 1162), the translucent brushwork and sense of layering are closer to the blue-and-green literati tradition of Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322).

The lines for the figures here are simple and archaic, the rocks built up with variety and rhythm to demonstrate the leisurely and refined aesthetic of literati towards exotic scenery. The painting is dated to the equivalent of 1548, when Wen Zhengming was 79 by Chinese reckoning. Afterwards is a record by his son, Wen Jia (1501-1583), who states the handscroll was presented to an important official of the time, which is why Wen Zhengming did this copy of an ancient work.

Dragon Roaming Among Flowers

- Anonymous, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

- Album leaf, silk tapestry, 22.5 x 31.3 cm

Colored silk threads woven in a tapestry against a plain background depict a five-clawed dragon with its head upright roaming among numerous blossoms that create a riot of colors and shapes forming a complex background. The flowers here suggest auspiciousness and good fortune, symbolizing an orderly change of the seasons and such congratulatory notions as "riches in an everlasting spring" and "riches in halls of jade."

The skillful weaving is masterful, the tapestry threads dense with the golden dragon on a background of red threads. Gold strands were then propped to highlight the scales, the dragon's body outlined with dark brown to make it stand out. The lines are rounded and powerful, so that even though the dragon is concealed within a myriad blossoms, its nimble pose is clearly evident. The flower shapes are gentle and beautiful, the distinction between the layers rich and clear. Although having the decorative effect of a carpeted flowers, the motifs are still realistic in form, suggesting unlimited vitality.

Tapestry of a Wagtail

- Zhu Kerou (fl. 12th c.), Song dynasty

- Album leaf, silk tapestry, 29.7 x 24.8 cm

This scene, woven in colors against a light ochre background, features a wagtail perched on a rock in a stream looking down at shrimp among the rocks. Butterflies dance above for a lively and natural scene. "Long and short propping" methods of weaving create continuous variations that yield an effect similar to color washes, bringing out the layers of the wagtail's feathers and the translucent quality of the shrimp for a moist effect as well. The great use of two different kinds of colored silk delicately express the varied colors to the shadows in the water.

To the left is a woven seal that reads, "Seal of Zhu Kerou," referring to a famous Southern Song weaver active in the period of Emperor Gaozong (r. 1127-1162). Zhu's weaving here is tight and even, the techniques consummate, making this a fine work by her.

Yellow Oranges and Green Tangerines

- Zhao Lingrang (fl. ca. 1070-after 1100), Song dynasty

- Album leaf, ink and colors on silk, 24.2 x 24,9 cm

This rounded fan painting remounted as an album leaf depicts citrus trees along banks, the hues of yellow and green fruit complementing stones of various sizes in the water to create different subtle colors. The banks feature light blue-green washes, to which texturing in the form of ink brushwork was added for the shoals, instilling the scenery with much serenity and calm. Water plants grow here and there as a pair of wagtails and two pairs of waterfowl add considerable vitality to the work. Although the artist is given as Zhao Lingrang, scholars are still debating the identity of the actual painter.

This type of subject matter depicting banks and shoals, often known as "intimate scenery" in Chinese art history, was popular in the period between the Northern and Southern Song during the twelfth century. This work is an ideal example of such, depicting realistic scenery with an archaic touch. The opposing leaf has a transcription of poetry by Su Shi (1037-1101) that forms an ideal match for the painting here, the style of calligraphy appearing similar to that of the Southern Song emperor Gaozong (1107-1187).

Sport and Games in Ancient China

Ancient Chinese scholars did not just spend their time composing poetry or doing painting and calligraphy. In addition to the realm of cultural refinements, the ancients also took part in sport and game. To celebrate the Summer Universiade being held in Taipei this year, the National Palace Museum has specially selected works of art from its collection on the subject of sport and game. They include such skills as horseback riding, a kind of kickball, dragon boat regattas, entertainments on ice, a game called "pitch pot," and a type of polo. With the paintings on display here, let us see how the ancient Chinese demonstrated their sporting and gaming skills.

Playing "Cuju" at Leisure in a Courtyard

- Zhang Dunli (?-1107), Song dynasty

- Album leaf, ink and light colors on silk, 28.2 x 29.7 cm

This painting mounted as an album leaf depicts five figures under a tree playing a form of kickball. The person in the midst of kicking the ball has a more effeminate countenance and wears hair in a different way from the others. The figure even has a hairpin and a golden chest pendant, suggesting she is a lady! The story behind this scene, however, awaits further research.

The drapery lines of the figures in this painting feature strong and delicate brushwork, and particular attention has been placed on the description of the figures' faces. The shading washes are also refined. Despite its small size, it is still a masterpiece of figure painting. The traditional title slip gives Zhang Dunli as the artist. He was an imperial son-in-law of the Song emperor Zhezong who specialized in painting and calligraphy. However, very few works in his name have survived for comparison, making it difficult to confirm the attribution here.

(This work is on display from July 1 to August 14, 2017.)

Emperor Minghuang Playing "Jiju"

- Ding Guanpeng (ca. 1708-after 1771), Qing dynasty

- Handscroll, ink on paper, 35.6 x 251.9 cm

Ding Guanpeng, a native of Shuntian, entered the Qing court to serve as a painter in 1726. Studying Western painting techniques under Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining), he was an important court artist in the Qianlong reign. This work depicts the Tang dynasty emperor Minghuang (Xuanzong, 682-762) playing a game called "jiju," which is similar to polo. He is accompanied by eight palace ladies and attendants, and on the left and right are goal posts with goalkeepers.

The drapery lines of the figures in this painting refer to the "baimiao" monochrome ink methods of the Song artist Li Gonglin (1040-1106), to which some ink washes have been added to give a more volumetric effect. "Jiju" was a game played at the Tang dynasty court in which the players rode on horseback using sticks to hit a ball, the rules similar to those of field hockey.

Eight Princes on a Spring Excursion

- Attributed to Zhao Yan (fl. first half of the 10th c.), Five Dynasties period (Liang)

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 161.9 x 102 cm

This hanging scroll depicts eight figures on horseback riding in a fine garden and apparently demonstrating their equestrian skills. The figure in the middle bends over holding a whip and is probably the main character. The others are shown around him, confirming him as the focus. Scholarship has shown that the clothing of the figures here is similar to that of the Tang dynasty (618-907) and that the opulent horse ornaments are also part of equestrian attire among nobility in the late Tang and Five Dynasties period.

This painting is traditionally ascribed to the Five Dynasties painter Zhao Yan, but the arrangement of the figures in the garden is actually closer to the composition in the Song emperor Huizong's "Literary Gathering" from the early twelfth century, suggesting the date of production to be around the same time. Thus, the scroll may instead be an imaginative reconstruction of a Tang dynasty outing on the part of a Song artist.

(This is a "restricted" work for display from August 15 to September 25, 2017.)

Exhibit List

| Title | Artist | Period | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Idea of Snow on a River | Wang Wei (701-761 or 699-759), attributed to | Tang dynasty | - |

| Late Greenery of Autumn Mountains | Guan Tong (fl. early 10th c.) | Five Dynasties period | - |

| Tapestry of Birds and Flowers | Anonymous | Song dynasty (960-1279) | - |

| Tapestry of a Mynah and Peach Blossoms | Anonymous | Song dynasty (960-1279) | - |

| Lohan | Li Song (ca. 1170-1255), attributed to | Song dynasty | - |

| River in Snow | Li Tang (ca. 1070s-1150s), attributed to | Song dynasty | - |

| Waterfowl and Hibiscus | Liang Kai (fl. early 13th c.) | Song dynasty | - |

| Mending a Cassock | Liu Songnian (fl. late 12th-early 13th c.), attributed to | Song dynasty | - |

| Wild Pheasants Among Plum Blossoms and Bamboo | Ma Yuan (ca. 1190-1225) | Song dynasty | - |

| Tapestry on the Poetic Idea of Autumn Mountains | Shen Zifan | Song dynasty (960-1279) | - |

| Crape Myrtle Sketched from Life | Wei Sheng | Song dynasty (960-1279) | - |

| Insects and a Cabbage Plant | Xu Di | Song dynasty (960-1279) | - |

| Yellow Oranges and Green Tangerines | Zhao Lingrang (fl. ca. 1070-after 1100) | Song dynasty | - |

| Tapestry of a Wagtail | Zhu Kerou (fl. 12th c.) | Song dynasty | - |

| Tapestry of a Thrush Among Peach Blossoms | Zhu Kerou (fl. 12th c.) | Song dynasty | - |

| Dragon Roaming Among Flowers | Anonymous | Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) | - |

| Hunting on Horseback | Anonymous, attributed as | Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) | - |

| Rongxi Studio | Ni Zan (1301-1374) | Yuan dynasty | - |

| Sketching from Life | Wang Yuan (fl. first half of the 14th c.) | Yuan dynasty | - |

| Seven Star Junipers | Anonymous | Ming dynasty (1368-1644) | - |

| Snowy Landscape and Birds | Lü Ji (fl. 1439-1505) | Ming dynasty | - |

| After Zhao Bosu's "Latter Ode on the Red Cliff" | Wen Zhengming (1470-1550) | Ming dynasty | - |

| Tapestry of White Duckweed and Red Polygonum with Imperial Poetry | Anonymous | Qing dynasty (1644-1911) | - |

| Activities of the Twelve Months: The Eighth Month | Court painters | Qing dynasty (1644-1911) | - |

| Spring Dawn in the Han Palace | Court painters | Qing dynasty (1644-1911) | - |

| Amitayus Butdha | Ding Guanpeng (ca. 1708-after 1771) | Qing dynasty | - |

| After a Landscape by Guan Tong | Wang Hui (1632-1717) | Qing dynasty | - |

| In Imitation of Wang Wei's "Clearing After Snow in Shanyin" | Wang Hui (1632-1717) | Qing dynasty | - |

| In Imitation of Li Cheng's "Seven Trees on a Riverbank" | Wang Hui (1632-1717) | Qing dynasty | - |

| Imitating Li Tang's "Spring Trees of a Myriad Years" | Wang Yuanqi (1642-1715) | Qing dynasty | - |

| Sport and Games in Ancient China | |||

| Eight Princes on a Spring Excursion | Zhao Yan (fl. first half of the 10th c.), attributed to | Five Dynasties period (Liang) | On display 8/15-9/25 |

| Playing "Cuju" at Leisure in a Courtyard | Zhang Dunli (?-1107) | Song dynasty | On display 7/1-8/14 |

| Dragon Boat Snatching the Pennant | Wu Tinghui (fl. 14th c.), attributed to | Yuan dynasty | - |

| Activities of the Twelve Months: The Eleventh Month | Court painters | Qing dynasty (1644-1911) | - |

| Emperor Minghuang Playing "Jiju" | Ding Guanpeng (ca. 1708-after 1771) | Qing dynasty | - |

| Illustrating the Imperial Ode on Ice Games | Shen Yuan (fl. 18th c.) | Qing dynasty | - |