To meet the need for recording information and ideas, unique forms of calligraphy (the art of writing) have been part of the Chinese cultural tradition through the ages. Naturally finding applications in daily life, calligraphy still serves as a continuous link between the past and the present. The development of calligraphy, long a subject of interest in Chinese culture, is the theme of this exhibit, which presents to the public selections from the National Palace Museum collection arranged in chronological order for a general overview.

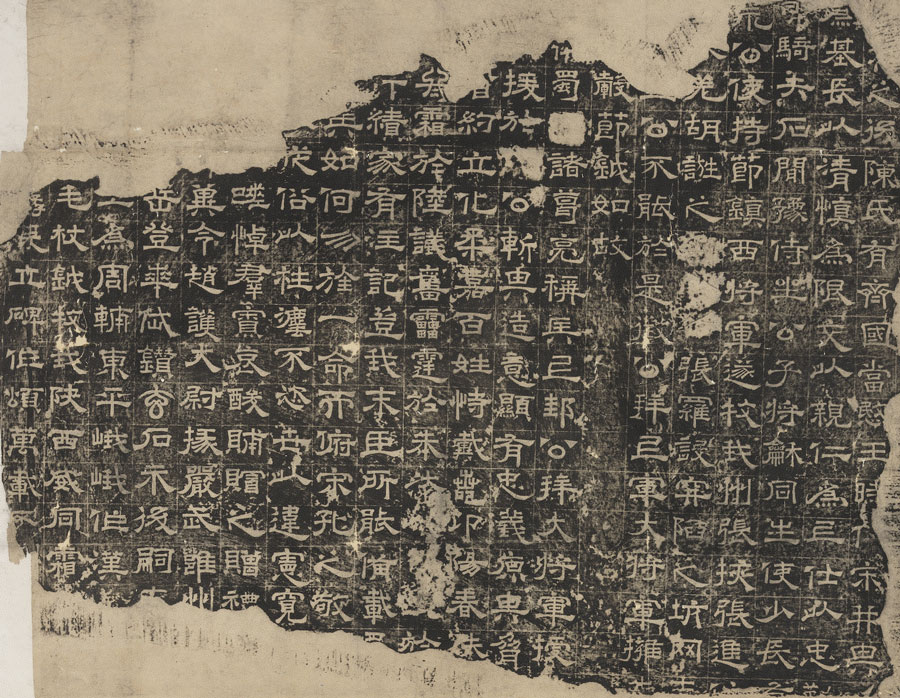

The dynasties of the Qin (221-206 BCE) and Han (206 BCE-220 CE) represent a crucial era in the history of Chinese calligraphy. On the one hand, diverse forms of brushed and engraved "ancient writing" and "large seal" scripts were unified into a standard type known as "small seal." On the other hand, the process of abbreviating and adapting seal script to form a new one known as "clerical" (emerging previously in the Eastern Zhou dynasty) was finalized, thereby creating a universal script in the Han dynasty. In the trend towards abbreviation and brevity in writing, clerical script continued to evolve and eventually led to the formation of "cursive," "running," and "standard" script. Since changes in writing did not take place overnight, several transitional styles and mixed scripts appeared in the chaotic post-Han period, but these transformations eventually led to established forms for brush strokes and characters.

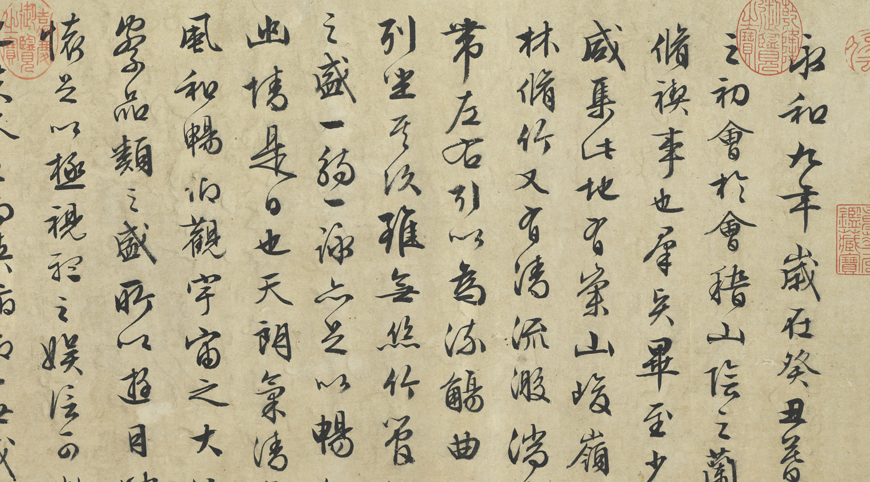

The dynasties of the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) represent another important period in Chinese calligraphy. Unification of the country brought calligraphic styles of the north and south together as brushwork methods became increasingly complete. Starting from this time, standard script would become the universal form through the ages. In the Song dynasty (960-1279), the tradition of engraving modelbook copies became a popular way to preserve the works of ancient masters. Song scholar-artists, however, were not satisfied with just following tradition, for they considered calligraphy also as a means of creative and personal expression.

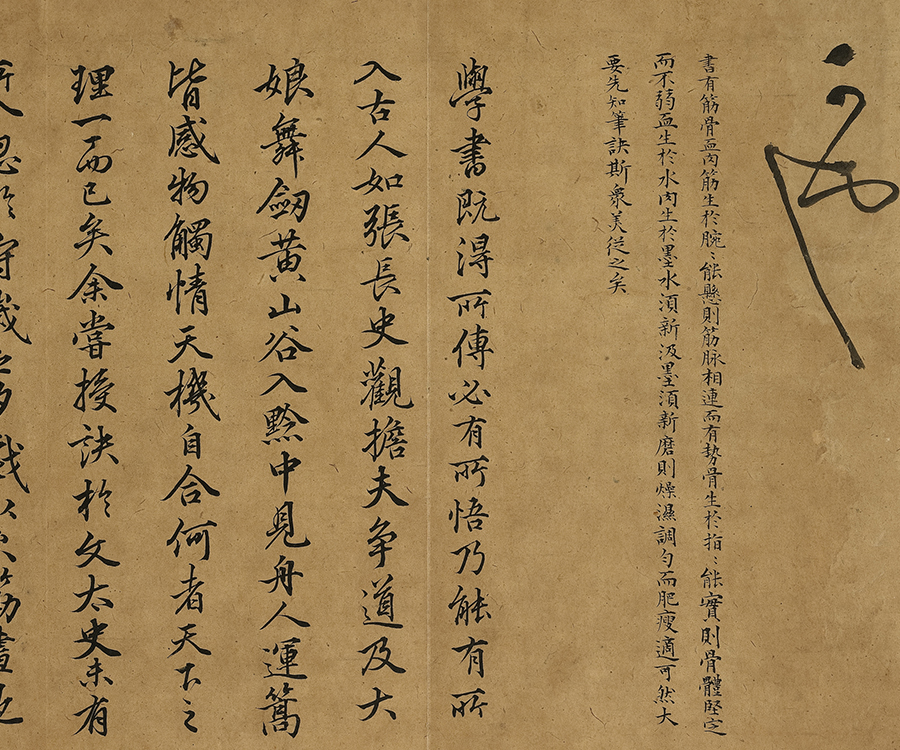

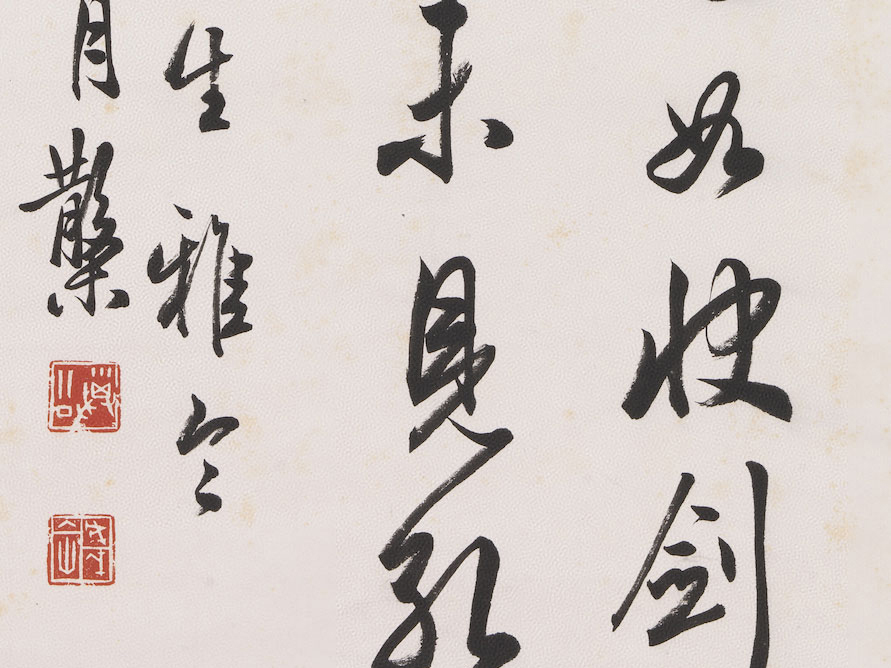

Revivalist calligraphers of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), in turning to and advocating revivalism, further developed the classical traditions of the Jin and Tang dynasties. At the same time, notions of artistic freedom and liberation from rules in calligraphy also gained momentum, becoming a leading trend in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Among the diverse manners of this period, the elegant freedom of semi-cursive script contrasts dramatically with more conservative manners. Thus, calligraphers with their own styles formed individual paths that were not overshadowed by the mainstream of the time.

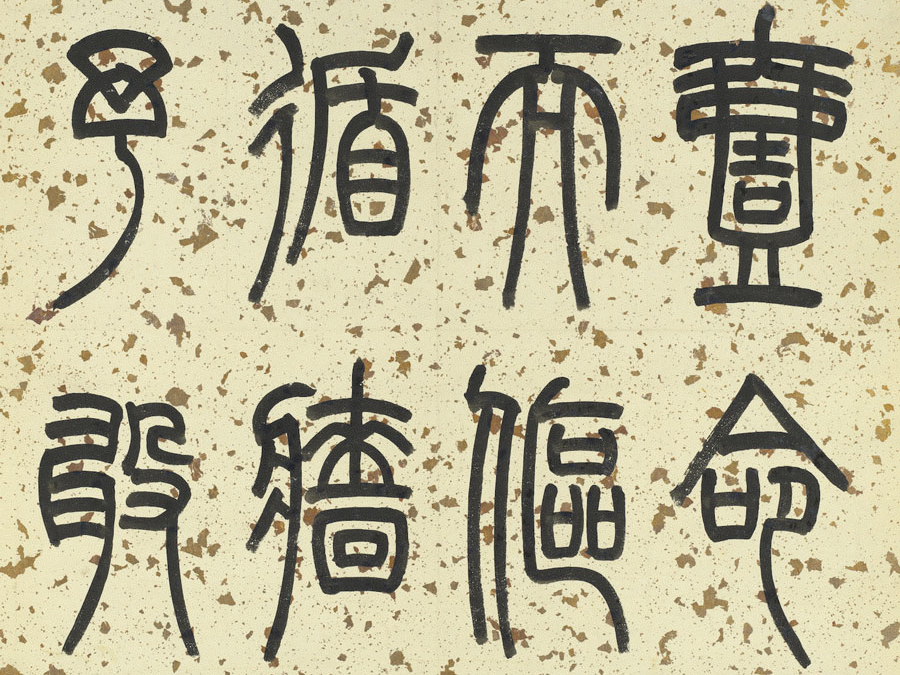

Starting in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), scholars increasingly turned to inspiration from the rich resource of ancient works inscribed with seal and clerical script. Influenced by an atmosphere of closely studying these antiquities, Qing scholars became familiar with steles and helped create a trend in calligraphy that complemented the Modelbook school. Thus, the Stele school formed yet another link between past and present in its approach to tradition, in which seal and clerical script became sources of innovation in Chinese calligraphy.