Introduction

Taoism is broadly recognized as both a philosophy and a religion. The two are distinct yet interconnected. Philosophical Taoism is rooted in the philosophies of Laozi, Zhuangzi, and the prevalent Huang-Lao school during the Warring States, Qin, and Han dynasties. It centers on “Tao” (the Way) and promotes principles of purity, emptiness, and inaction in self-development and governance, and offers guidance on relationships with people and attitudes to the cosmos with the principle that “the Tao follows its own nature”. Religious Taoism, however, seeks spiritual immortality and enlightenment through the Tao. It includes a rich tapestry of scriptures, doctrines, institutions, rituals, and various sects, which sets it significantly apart from earlier philosophical counterparts. Despite these differences, philosophical Taoism forms the foundation of Taoist religious belief, meaning the two must be considered as interconnected rather than completely separate.

Ji Xiaolan (1724-1805), chief editor of the Complete Library of the Four Treasuries (Siku Quanshu), lauded Taoism for its long history and breadth, which is evident in Taoism’s 1,800-year evolution, beginning with the incorporation of Pre-Qin texts from Laozi and Zhuangzi and growing through centuries of religious practice. Assimilating elements such as alchemy, astrology, divination, and even Buddhist teachings since the Han dynasty, over time Taoism amassed a rich array of scriptures, covering doctrinal codes, methods of internal and external cultivation, and rituals of fasting and offerings.

From the Sui and Tang to the Northern Song dynasties, Taoism thrived, boosted by the reverence of royal and noble families and gaining substantial social influence. Its philosophies, qi cultivation practices, techniques for health preservation, talismans, incantations, and ritual frameworks all underwent refinement during this period. The Golden Elixir sect, which was focused on internal alchemy, gained prominence in the late Tang and Northern Song eras. The Southern Song, Jin, and Yuan periods witnessed the rise of new Taoist sects in North China, including Quanzhen, Taiyi, and Zhengda, while the South saw the emergence of the Shenxiao, Qingwei, and Jingming sects. In the Ming dynasty, emperors including Yongle and Jiajing had close ties with Taoism. However, as imperial preferences shifted towards Buddhism during the Qing dynasty, Taoism’s growth waned and it fell away from the heights of its former glory.

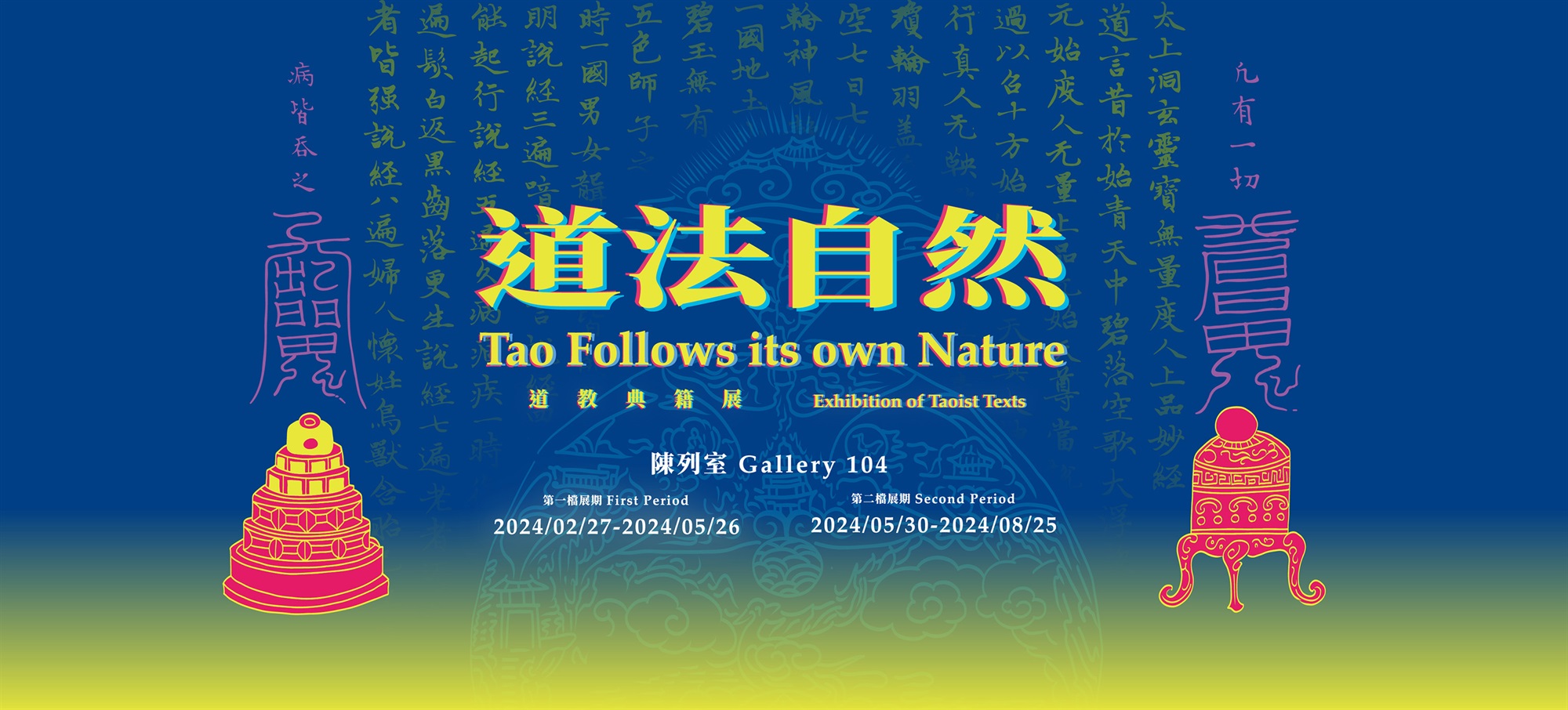

The National Palace Museum's collection of Taoist texts mainly originates from the Yuan and Ming dynasties. While not as extensive as its Buddhist collection, it boasts rare and unique editions from the former Imperial Collections. The exhibition is divided into four sections: Essential Taoist Scriptures, Highlights of the Taoist Canon, Emperors and Taoism, and the Nourishing Life and Longevity.