Selections

Some things to think about before enjoying this exhibit

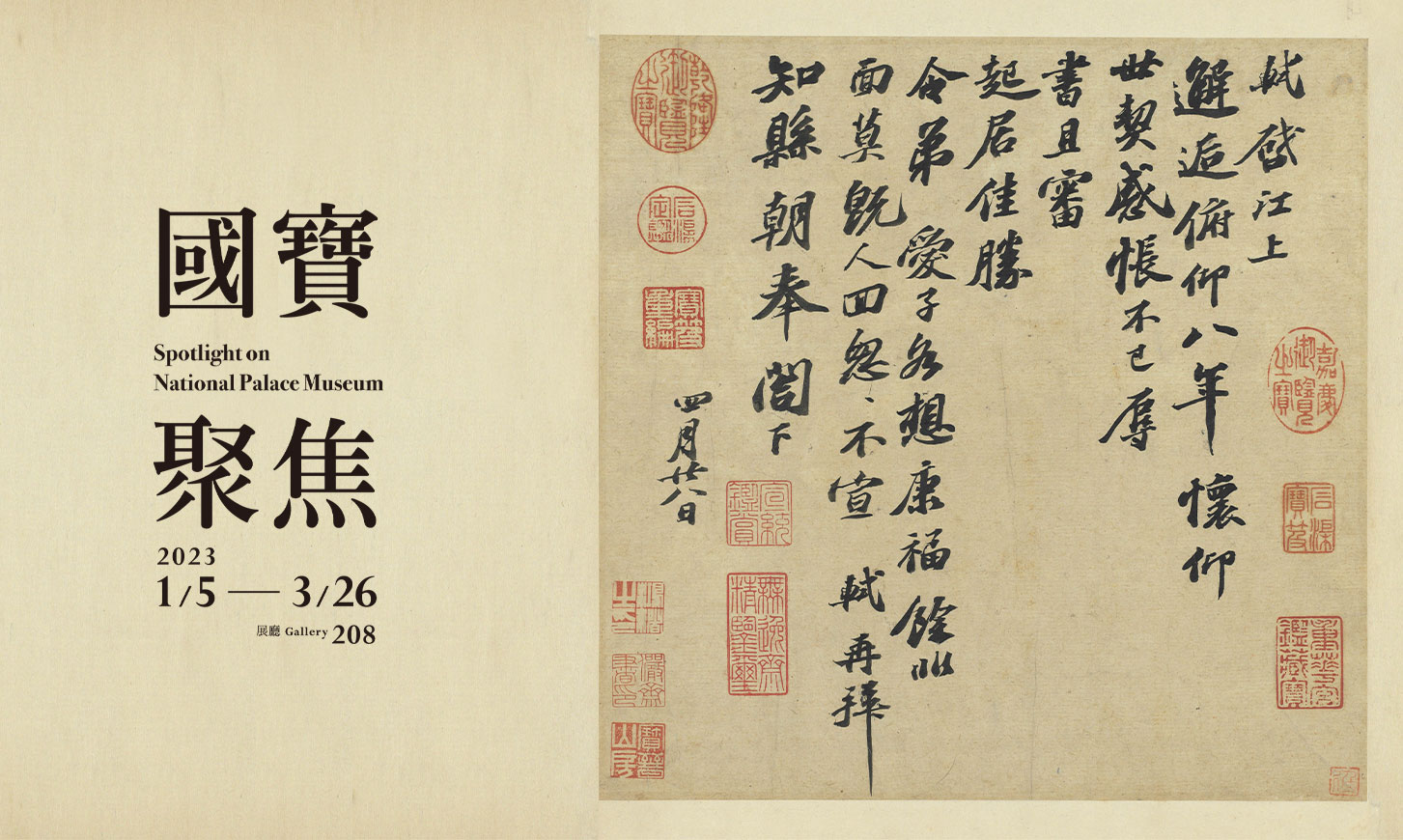

Of all of the extant works of calligraphy written by the Song dynasty literary giant Su Shi, “Letter to the Head County Magistrate, Gentleman in Service of the Court” is the piece written at the latest point in his life—for this reason it has been referred to as his “swansong.” It is also one of the items in the NPM’s collection with the title “National Treasure.” This type of document is known as a chidu, and is what would now be referred to as a handwritten letter. According to historical research, this letter was written to Su Shi’s good friend, Du Mengjian. What would Su’s mind state have been as he wrote this letter? Where was he? How is the artistry inherent in calligraphy meant to be enjoyed? We hope that by presenting text and images in conjunction, this exhibit will help you gain a broader understanding of who Su Shi was, as well as a deeper appreciation for his art.

A Master of Both Poetry and Calligraphy

Su Shi “Watching the Tidal Bore”

Mount Lu’s mists and rain, the Zhe River tidal bore,

If you never see these two things, you’ll suffer a thousand regrets.

But after you’ve seen them and gone home, everything’s the same as it ever was,

Mount Lu’s mists and rain, the Zhe River tidal bore.

Su Shi’s literary talents were unparalleled, and his poems and essays have remained widely appreciated up through to the present day. His poem “Watching the Tidal Bore” is also known by the name of the genre to which it belongs—“Head and Tail Song”—which refers to the fact that the poem’s first and last lines are the same. According to one account, this was Su Shi’s last poem, written for his third son Su Guo (1072-1123) shortly before he passed away. The poem’s lines contain a strong Zen ethos, suggesting a state of mind both expansive and incisive. By reading this poem, we might possibly gain insight into Su Shi’s broad-minded psychological state as he wrote “Letter to the Head County Magistrate, Gentleman in Service of the Court.”

A Chinese term that means “ultimate brushwork” is often used to describe this poem. This term can be interpreted either as referring to a person’s final written work, or to a masterpiece of calligraphy. In this case, the term refers to the fact that “Watching the Tidal Bore” poem may have been Su Shi’s final poem.

Letter to the Head County Magistrate, Gentleman in Service of the Court Su Shi, Song dynasty

- National Treasure

- Officially Certified by the Ministry of Culture of Taiwan in January, 2013

Su Shi (1037-1101), of Meishan in Sichuan province, had the style name Zizhan and the sobriquet Dongpo, or “Recluse of the Eastern Slope.” Su was a master of poetry, prose, calligraphy, and painting. Huang Tingjian (1045-1105) heralded his calligraphy as the Song dynasty’s finest.

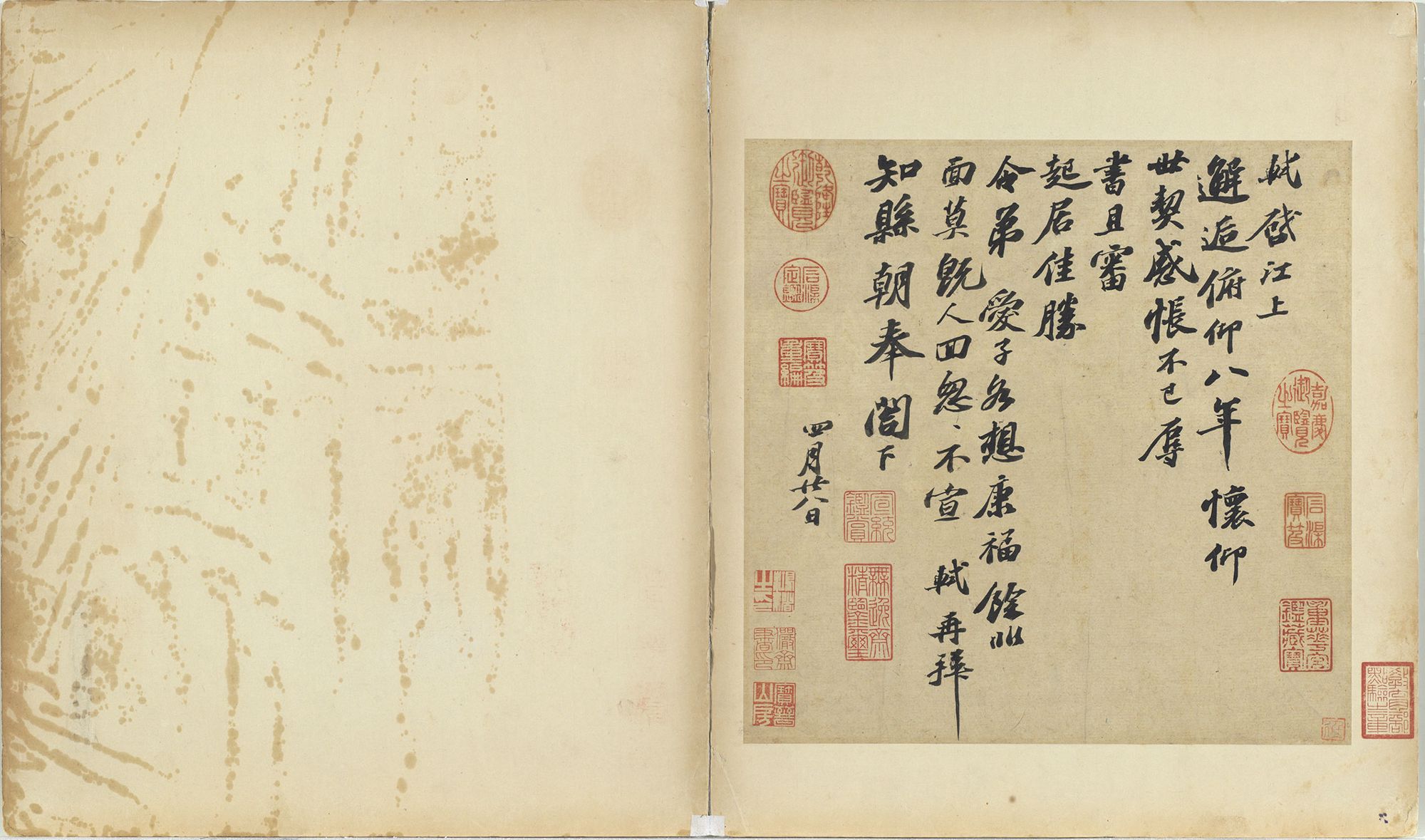

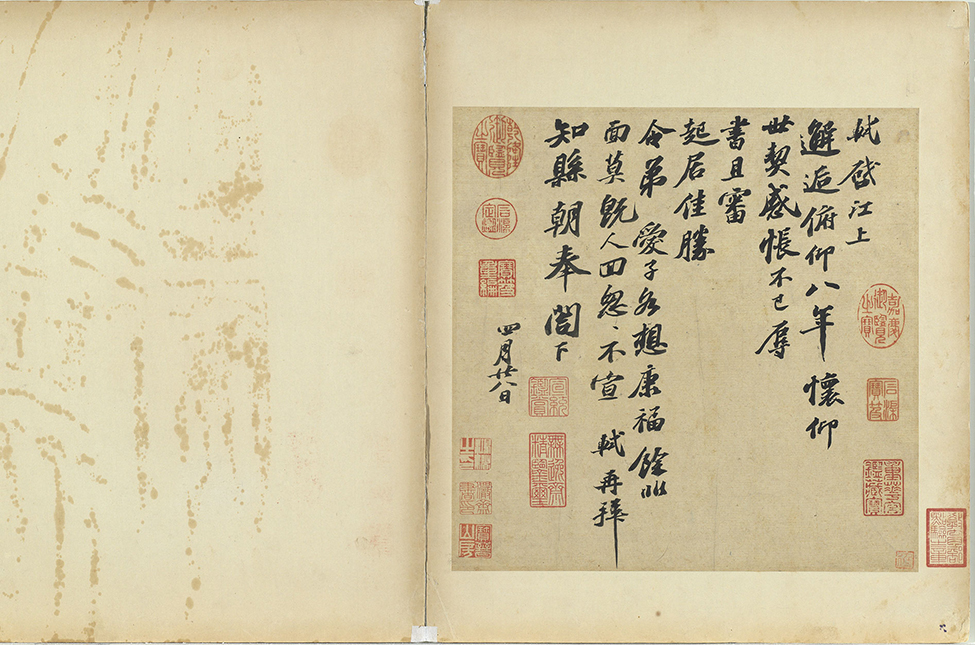

In the third year of Emperor Zhezong’s Yuanfu reign period (1100), Su Shi was ordered to return to the capital from his six-year period of banishment in Danzhou. Before traveling to Jinling (present day Nanjing) the following year, he wrote this letter addressed to an official with the title “head county magistrate, gentleman in service of the court”—research suggests this person was Du Mengjian (dates unknown). The Su and Du families maintained close ties for four generations, which explains why this letter was written in simple, direct language while being full of sincere sentiment. The character structures are skewed so that their right sides are higher than their left sides. Su wielded his brush valorously as he wrote this piece, which is his final extant work of calligraphy.

Calligraphic Style

When Su Shi was young he studied the calligraphy of the “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion,” and then in middle age he turned towards studying the calligraphic works of Yan Zhenqing (709-785) and Yang Ningshi (873-954)—a course of development that, according to Huang Tingjian, made him the Northern Song dynasty’s premier calligrapher. A close look at “Letter to the Head County Magistrate, Gentleman in Service of the Court,” reveals that Su’s brushwork, composition, and character structures all follow the traditions of Jin and Tang dynasty calligraphy. For instance, with the characters 人, 令, and 愛 (meaning “person,” “orders,” and “love,” respectively), Su used a technique in his downward-right concave falling strokes in which the brush’s tip makes three subtle turns within each brushstroke, giving them striking silhouettes. This preference likely had something to do with the influence of Northern Song dynasty calligrapher Zhou Yue (dates unknown), as Su Shi wrote a poem in which he said that he called out to Zhou Yue when lowering his brush to paper. Details such as these allow us to glimpse calligraphy’s historical origins, as well as to witness how calligraphy evolved as an art.

Wandering to the Ends of the Earth

On the thirteen day of the first lunar month of the third year of the Yuanfu reign period (1100), Huizong became emperor of the Song dynasty and, following tradition, issued a nationwide amnesty. Su Shi subsequently received orders to return from Danzhou (present-day Dan county on the island of Hainan) to the capital. However, while en route he died from illness in Changzhou on the twenty-eighth day of the seventh lunar month of the same year. Su had passed his entire adult life rising and falling with the vicissitudes of court life, seldom staying in one place for long. In his later years, while reflecting on the past, he wrote, “My heart is like wood that’s already turned to ash, and my body is like an unmoored boat. If you ask me what I accomplished in my life, it’s Huangzhou, Huizhou, and Danzhou.”

Exhibit List

| Spotlight | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Artist | Title | Form | No. | Remark | |

| Song dynasty | Su Shi | Letter to the Head County Magistrate, Gentleman in Service of the Court | Album | 故書236-1 | National Treasure |