Figure Painting

-

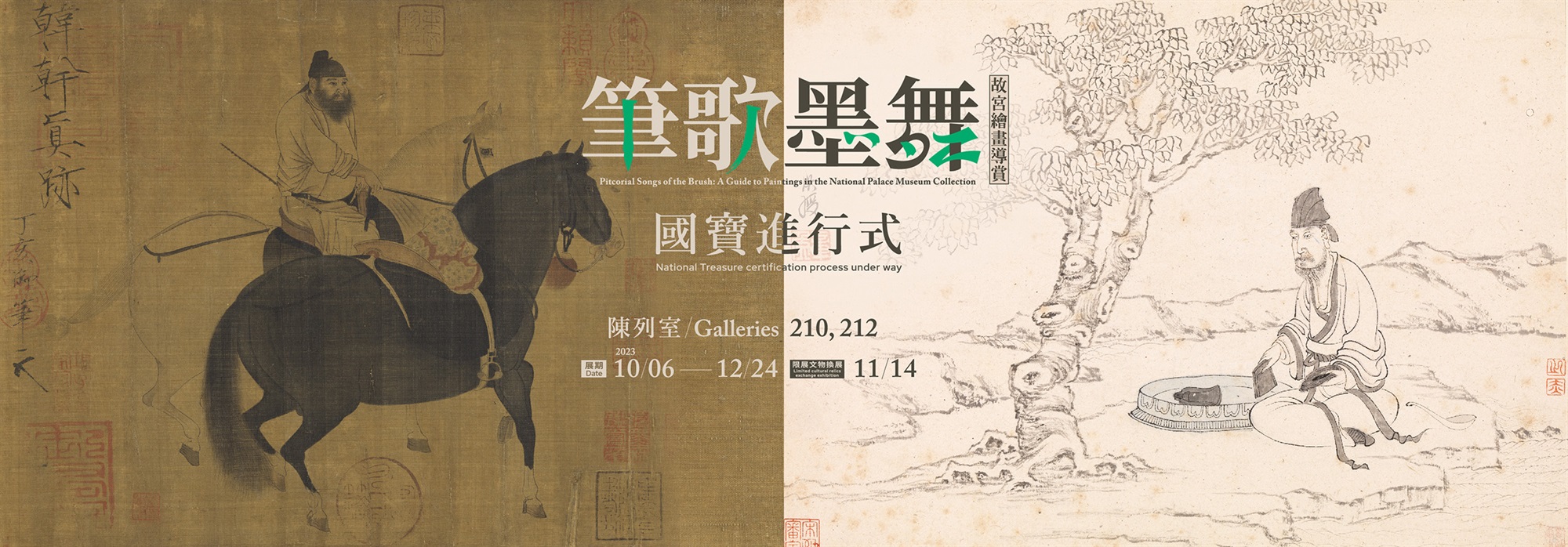

Herding Horses, Han Gan, Tang dynasty

Certified National Treasure

This painting depicts an official groom for imperial horses riding astride a white horse while leading a black steed such that the two animals trot side-by-side. The painting features a calligraphic inscription by the Song dynasty emperor Huizong (1082-1135) dating to the ding-hai year (1107) which reads, “An authentic painting by Han Gan.” Han Gan was a renowned painter of horses who lived during the reign of Tang dynasty emperor Xuanzong (r. 712-756). The groom’s general appearance as well as the horses’ round rumps and short legs are both similar to paintings discovered on the walls of Tang dynasty tombs, which are characterized by depictions of vigorous figures with ample physiques. However, the painting’s fine and nimble brushwork, the use of contiguous brushstrokes with angular turns, and colorful brocade on the saddle all belong to the style of painting current in Huizong’s time. It can thus be surmised that this is a masterful copy of an older painting that was made at the end of the Northern Song dynasty.

-

Traveling by River During the First Snowfall, Zhao Gan (ca. latter 10th century), Southern Tang dyna

Zhao Gan (ca. latter 10th century), of Jiangning in Jiangsu province, was a court painter during in the Southern Tang dynasty. It is said that Li Yu (937-978), the final ruler of this dynasty, wrote the calligraphic inscription at the head of this scroll naming the title of the painting, its creator, and its period. Pale washes were applied to the silk atop which this scroll was painted, after which white pigment was added to depict snow. Although strong, agile brushwork was used to depict the barren, wintry trees, their trunks were textured using a dry brush, creating a sense of dynamic tension. The mounds and foothills were daubed with splotches of pale ink instead of being rendered with specific texturing techniques. This scroll is thematically devoted to riverside travel and the lives of fishermen—not only did the painter precisely portray the various fishermen and their modes of catching fish, he also added details such as a shivering child huddled against the cold and a donkey walking against the wind, yielding a strong visual sense of actually visiting this locale.

-

Recluse in the Shade of a Willow Tree, Anonymous, Song dynasty

A scholar living in seclusion sits in the shade beneath a willow tree atop a leopard skin rug, his feet bare and his robes falling from his chest and back. The look of happy tipsiness in his eyes gives the sense of a person free, at ease, and aloof from the world. The poet Tao Yuanming (365-427) once wrote an essay in which he referred to himself as “the Gentleman of the Five Willows”—from similarities between his essay and this painting’s tree, vessels, and clothing we can infer that the subject is none other than Tao. Sharp, incisive brush turns and lines as strong as iron wire were used to paint the figure and objects. The willow’s trunk appears ancient, its leaves thickly grown. The artist used steady, agile brushwork to create multilayered texturing, giving the painting’s surface a refinedly sumptuous appearance. In terms of composition, brushwork, and coloration, this is an outstanding specimen of figure painting.

-

Spring Dawn in the Han Palace, Qiu Ying, Ming dynasty

Certified National Treasure

Qiu Ying (ca. 1494-1552) had the style name Shifu and the sobriquet Shizhou (“Ten Continents”). As one of the four masters of Ming dynasty painting, Qiu created works marked by the exquisiteness of the imperial painting academy and redolent with literati airs.

This work’s background is a Han dynasty palace at dawn in the springtime. Painted with great beauty and tremendous variety, the environs are interspersed with scenes from the story of Mao Yanshou painting the imperial concubine Wang Shaojun, before being executed for creating an ugly portrait. This piece’s composition is intricate, its brushwork crisp, and its coloration splendidly sophisticated. The trees, decorative stones, and ornate palace buildings play off of one another, in an arrangement that suggests a divine realm’s striking environs. Not only does this painting depict a bevy of gorgeous maidens, it engages them in scholarly leisure activities such as playing stringed instruments, playing go, practicing calligraphy, painting, appreciating antiques, and cultivating flowers. This work is indeed a masterpiece among Qiu Ying’s depictions of historical tales.

-

Sixteen Views of Eremitic Living, Chen Hongshou, Ming dynasty

Chen Hongshou (1598-1652), of Zhuji in Zhejiang province, had the style name Zhanghou and the sobriquet Laolian (“Old Lotus”). Following the jia-shen year of 1644, he began calling himself Huichi and Wuchi. Chen was a superb painter of human figures, flowers, birds, plants, and insects. He instilled his paintings of all of these subjects with originality.

It is not clear what all of the specific stories behind “Sixteen Views of Eremitic Living” are, but these paintings depict sixteen different aspects of the lives of people living as hermits. Some of the paintings themes come from tales of adepts who lived in ancient times, while others derive from some of “Old Lotus’s” own life experiences. Chen painted in a freehand manner in order to convey deep-rooted sentiments. According to an inscription on the work, the artist painted it when he was fifty-four years old, a year before he passed away. In terms of its creativity, composition, and coloration, this is one of Chen’s late-life masterpieces.