The Qianlong emperor collected Di Xue (Treatise on How to Become an Emperor), and issued an imperial edict that requested the princes to study and transcribe the entire context. It can be inferred that the Qianlong Emperor understood that to invest great endeavours into academic studies, to follow footsteps of forefathers and emperors, and to govern the country with all devotions were essentialities required for a successful emperor to build the prosperous nation. The quality that separated the Qianlong Emperor from previous emperors was his keen admiration for antiquities. The Qianlong Emperor frequently expressed his opinions through imperial writings and poems, and consciously kept the evidences of identification and restoration during the process of advanced maintenance. Through examinations of the inherited legacy, we can see the "tapestry with repeated-octagon patterns" that he used to remount calligraphy works and paintings, specially made "belt with eight-treasures pattern" for securing hand scrolls, and several exhibits presented with the engraved signature of the Qianlong emperor. From the perspective of the art works, close examinations also reveal that many works produced during Qianlong's reign were based on copies of the old Qing court collection. Regardless of whether innovated creations possibly have altered the styles and characteristics of original works, the constantly reappearing signatures of the Qianlong emperor delivered his ambition to build up a new brand name.

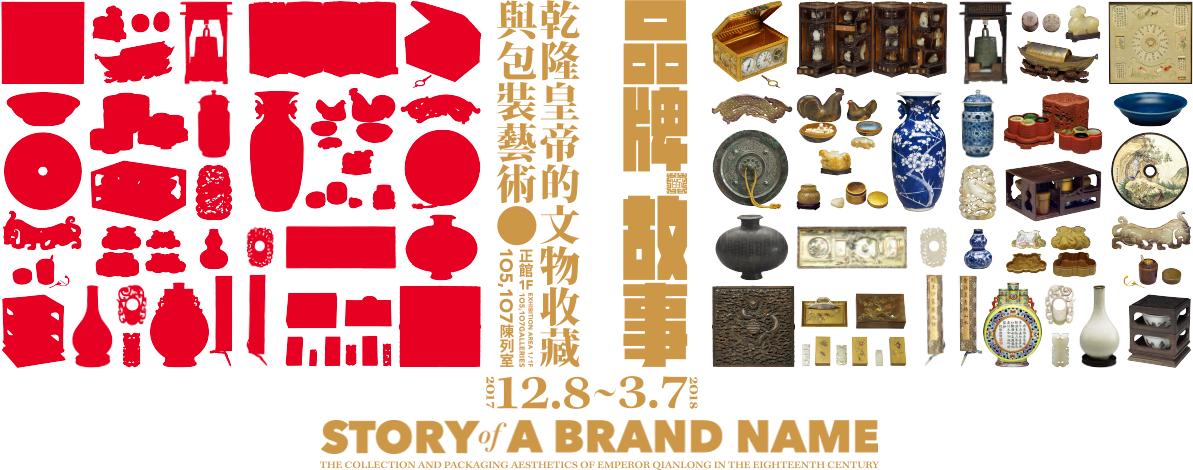

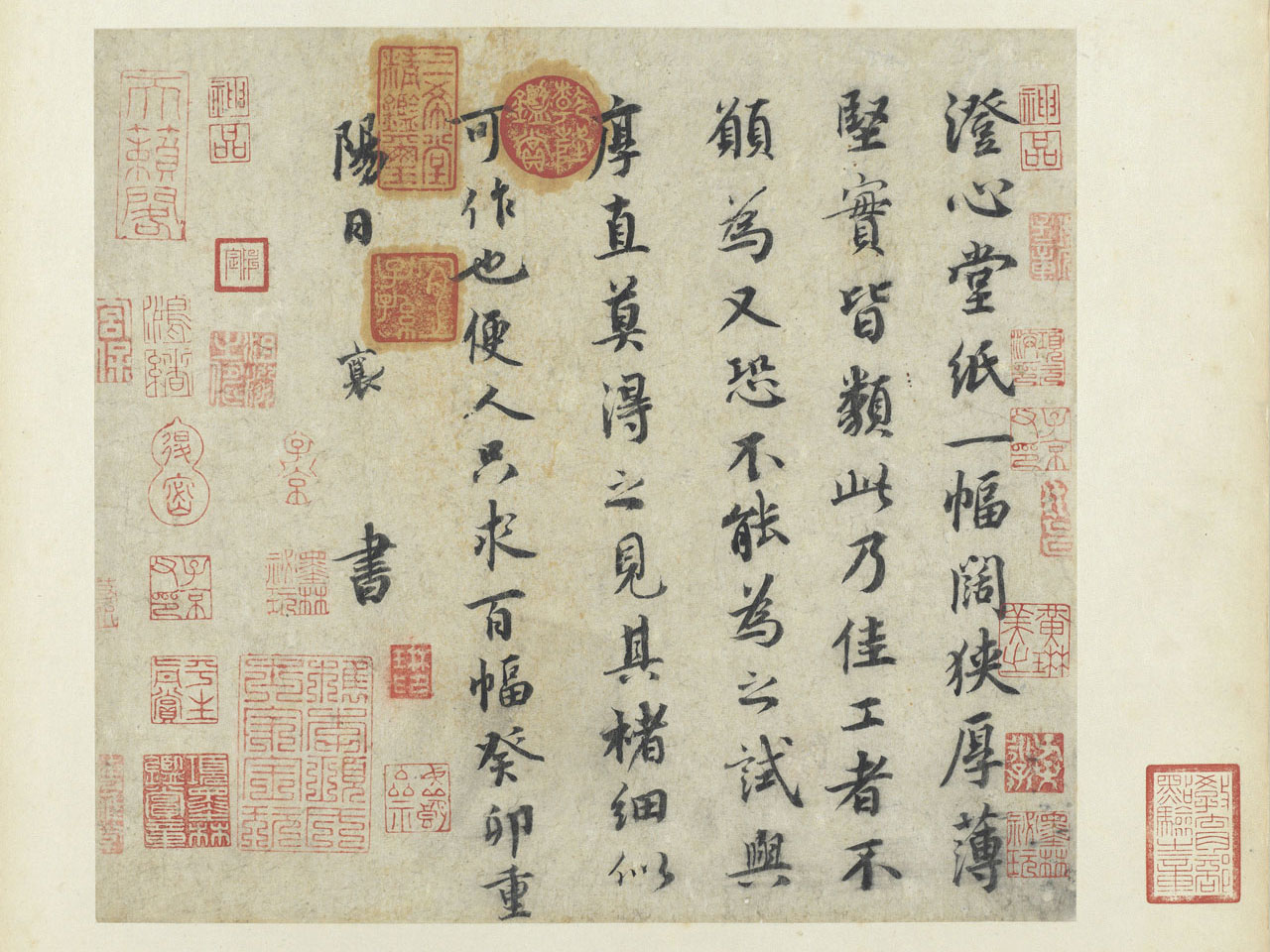

Letter

- Cai Xiang (1012-1067), Song dynasty

- Album leaf, ink on paper, 42.1x71.3 cm

Cai Xiang (1012-1067), style name Junmuo, native of Xienyou, Fujian Province. This piece was written in regular script, and the fluency of his writing gave a sense of modesty to this excellent calligraphy. Paper of Cheng Xin Studio with smooth surface and resilient quality is believed that had been made by imperial court of Southern Tang dynasty. This piece of paper was not considered as paper of Cheng Xin Studio in the Treasured Book of the Stone, which indicates that Qing court held different opinions regarding this paper.

Paper of Cheng Xin Studio. It will be marvelous to have the same quality as this paper. Makers out of their fear of failure were reluctant to produce. Attempt was made to reproduce but could not have results. Might be possible to reproduce after close examination. One hundred pieces were required. 9th of September of lunar calendar. Year 1063. Wrote by Xiang.

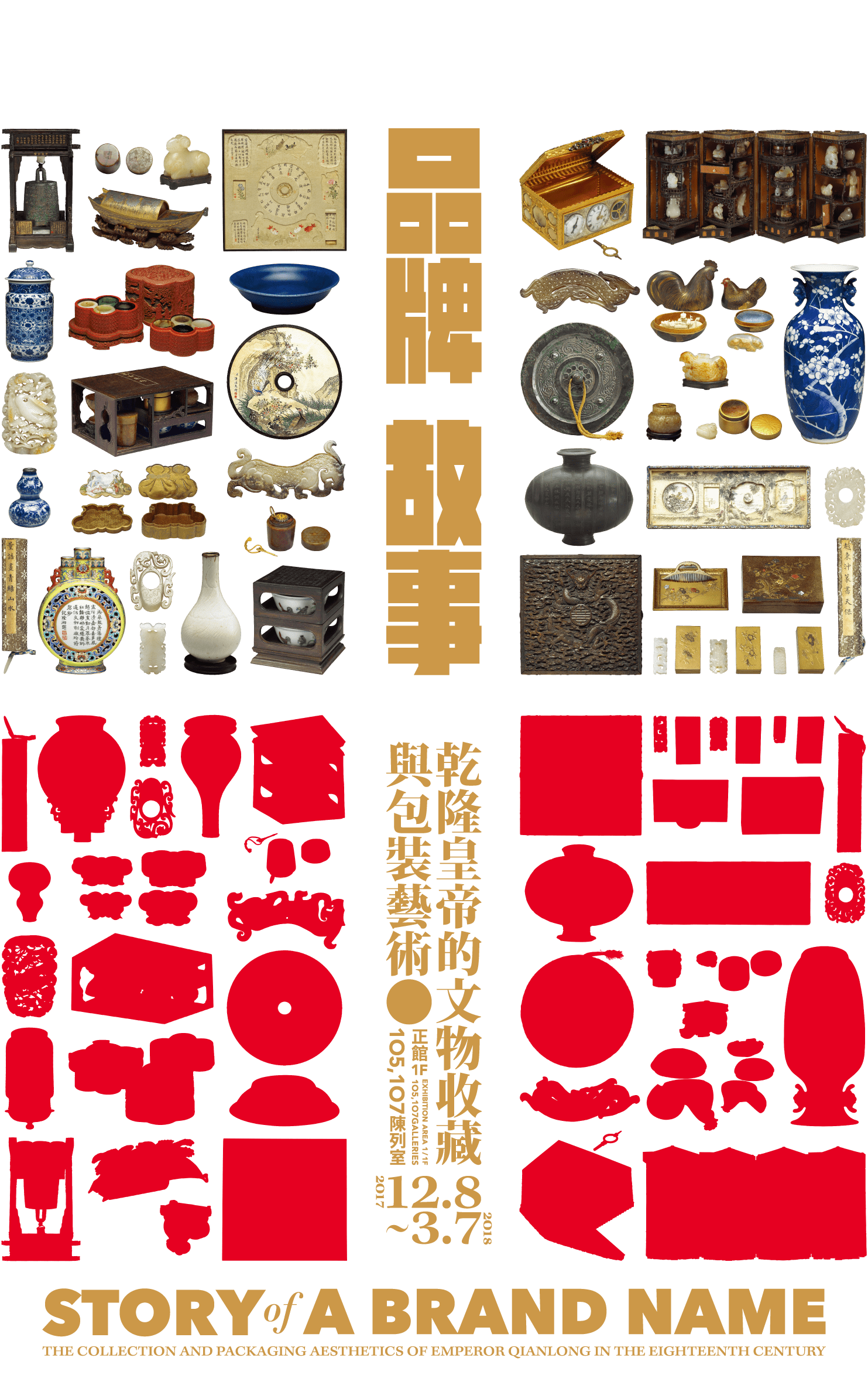

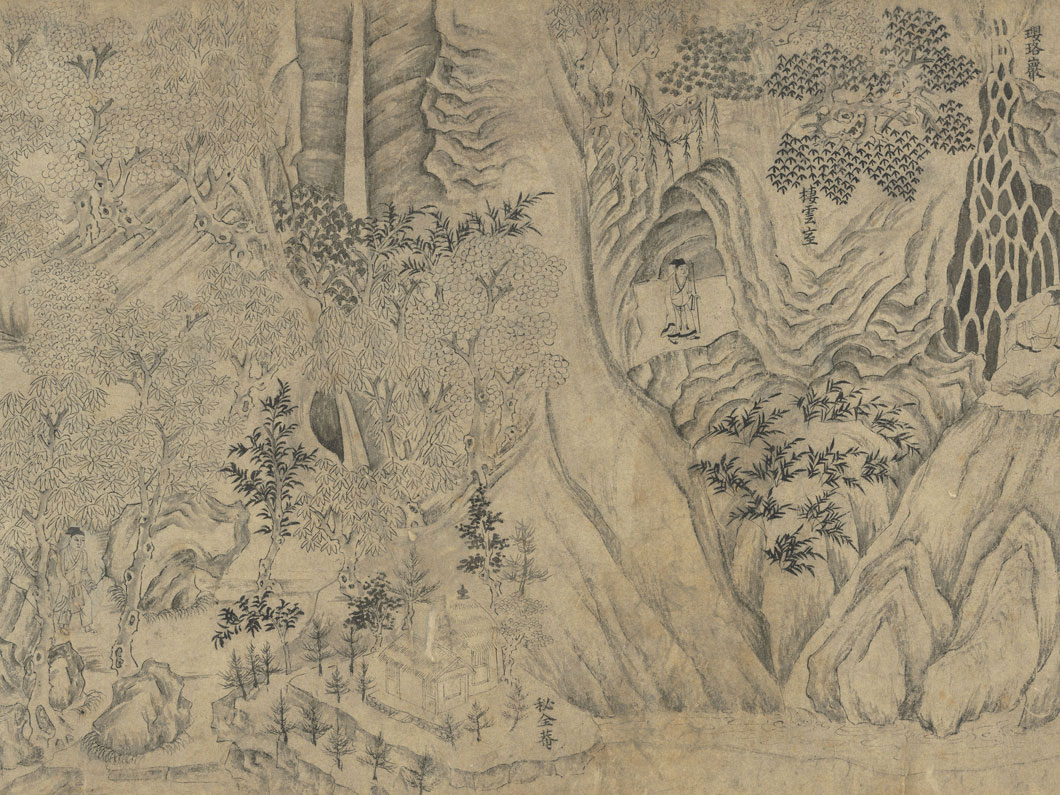

Painting of Mountain Villa

- Li Gonglin (1049-1106), Song dynasty

- Handscroll, ink on paper, 28.9x 364.6 cm

This Painting of Mountain Villa is anonymous, and traditionally attributed to Li Gonglin (1049-1106). This is one of the many circulating versions. The set of twenty poems titled, 'Painting of Mountain Villa by Li Gonglin' written by Su Che (1039-1112) indicated that the calligraphy written on the painting gave the name of each scenery. Although the poem is not entirely coherent to the painting, still the essences of the interaction between Li and his friends were captured. Li's creativity was demonstrated by the refined details drawn with plain strokes and the geometric landscapes. The "Painting of Wang River" painted by Wang Wei from the Tang dynasty influenced the intricate interaction seized by Li's painting, to amplify the quality of literati. Li Gonglin, sobriquet Longmian Jushi, and a native of Shuzhou, Anhui Province. Li took pleasure in collecting artworks and was specialized in painting figures, horses, and landscapes.

Inscription done by Dong Qichang indicated that paper of Cheng Xin Studio was used for Li Gonglin's personal works, and plain silk was used for the re-traced paintings. Although the Qianlong emperor held different opinions from Dong Qichang, but still convinced by the relationship of Li Gonglin and the paper of Cheng Xin Studio, and identified originals from the fakes based on this idea. The connection between Li Gonglin and the paper of Cheng Xin Studio was straightforwardly suggested, as he was the descendant of people from the Southern Tang dynasty. Additionally, the limited information regarding the paper of Cheng Xin Studio since the Song dynasty reinforced these opinions in the history of painting.

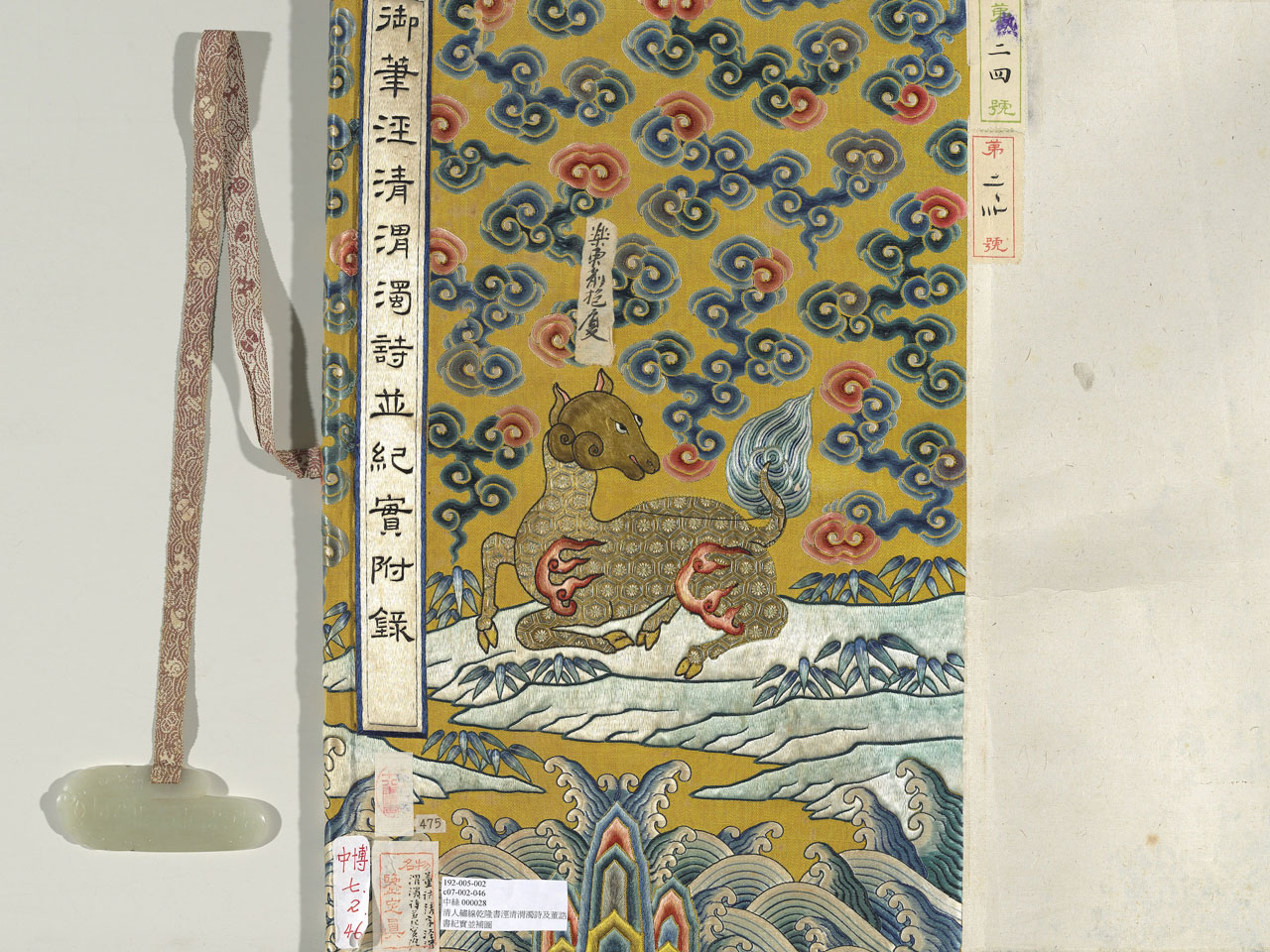

Division of Good and Evil poem by Emperor Qianlong and Complete Documentary and Painting by Dong Gao

- Qing dynasty, Chinese embroidery

- Hand scroll, 28x 354.4cm

The mount of this hand scroll had used the yellow silk tapestry decorated with ruyi-clouds in five colors and a deer resting among the landscape. The white-jade pin has the phoenix in low relief carved on the outside, and the "imperial manuscript of Division of Good and Evil poem" carved on the inside in clerical script and filled with gold paint. The "eight-treasure" belt with flower-and-water decoration on a white ground was attached to the pin. The context of this hand scroll is divided into two sections. The first part consists of the imperial manuscript of Division of Good and Evil poem, and the second part has Dong Gao's calligraphy work and the painting of the Jing and Wei river basin.

According to the Archives of the Imperial Workshops (Huojidang), an imperial edict was issued on the 21, March, the fifty-fifth year of the Qianlong reign to have Zheng Rui (1734-1815) in Suzhou Province to mount a hand scroll with silk tapestry decorated with gold dragon. On the 29, April of the same year, another hand scroll was delivered to Suzhou Province and requested for the same treatment. Comparisons of the inscription, context, and mounting method indicate that the exhibit and the two pieces recorded in the Archives of the Imperial Workshops (Huojidang) share high resemblances, but still have differences. At the same year, The archive of July at Ruyi hall recorded that, "Written by the minister Dong Gao on the jade bie plate, The set consists of the imperial manuscript of Division of Good and Evil poem, a written report by Qin Chengen, and an illustrated catalogue. The imperial edict was issued to have the hand scroll mounted by the Ruyi hall and then delivered to Jehol." The exhibit also fit this description, but the lack of information regarding the four-letter inscription and the material used for mounting, it cannot be certain if it is the exhibited piece. Based on the records, hand scrolls could had been mounted not only by the imperial workshop and the Ruyi hall, but also by the workshop in Suzhou Province.

Arguments of Emperor Qianlong against the Record of the Chao Ran Observatory by Su Shi

- Qing dynasty, Chinese silk tapestry

- Hand scroll, 34 x 90.3cm

In the fifty-seventh year of the Qianlong reign, Zheng Rui (1734-1815) was responsible for the mounting of hand scrolls in Suzhou Province. The set was completed with a jade bie plate, fabric cover, and a wood case, but the fabric cover was lost. The imperial edict was issued by the Gaozhong to have the silk tapestry applied on the front page, main context, and the cover, and the yellow paper was used for the original draft. The four letters 'Neixin Chouzhi' had been written on the front page on the xuan paper, and with the edges decorated with the Song pattern. The mount of this hand scroll had used the yellow silk tapestry decorated with ruyi-clouds in five colors and a deer resting among the landscape. The white-jade pin decorated with phoenix in low relief had the 'Arguments of Emperor Qianlong against the Record of the Chao Ran Observatory by Su Shi' carved on the inside and filled with gold paint. The "eight-treasure" belt with flower-and-water decoration on a white ground was attached to the pin.

The red sandalwood case was decorated with cloud-and-dragon pattern and polished with wax. The imagery of three dragons playing with a ball among the landscapes was carved on the lid. The title of this piece was carved on the centre of the case in clerical script and inlayed with delicate mother-of-pearl shell. The fine brass line surrounded the double-layered edges of the title, and the dark colour of the red sandalwood highlighted the decorative effect. The hand scroll and the wood case demonstrated the intricate and glamorous craftsmanship, and the complicated packaging was the signature of the royal court.

-

Lamp with floral decoration in underglaze blue

- Ming dynasty, Xuande reign (1426-1435)

- H. 10.6cm, diam. of mouth 4cm, diam. of mouth 4.7cm

-

Lamp with floral decoration in underglaze blue

- Ming dynasty, Xuande reign (1426-1435)

- H. 10.4cm, diam. of mouth 3.8cm, diam. of base 4.6cm

These two identical porcelain lamps have "Made in Xuande Reign, Great Ming" written in underglaze blue placed in between the neck and the spout. Two parallel strings of flowers surrounded the belly and the leg of the lamp, and supported by a round plate underneath. The set was protected by the tapestry cover and stored in the case. 'A Pair of Lamps from the Xuan Kiln' was marked on the case.

The numbering system begins with the letter "tian" indicates that these lamps were displayed at the Xinuan court, Qianqing palace. Based on Sun Ji's research, the lamps with a spout originated from the West. But in fact the lamps in underglaze blue appeared in the fifteenth century shared more resemblances to the Islamic bronze lamps of the twelfth century that had once unearthed from Kashgar region of Xinjiang Province. The interaction between China and Central and West Asia either travelled by land or sea was active during the Yongle and Xuande reign of the Ming dynasty, thus the production of the lamps in underglaze blue should be recognized within this context.

These lamps passed down to the Yongzheng and Qianlong reign also inspired the reproduction of copies. The Archives of the Imperial Workshops (Huojidang) from the sixteenth year of the Qianlong reign (1751) recorded that 'cases' and 'fabric cover' was given to the originals of the Xuande production. These activities manifested that during the time when artworks had been organized under Qianlong's imperial edicts, new creations were also developed along the process.

Chicken cups in doucai painted enamels

- Ming dynasty, Chenghua reign (1465-1487)

- H. 4cm, diam. of mouth 8cm / H.3.6 cm, diam. of mouth 8.2 cm

The chicken cup from the Chenghua reign contains a flared rim and a low foot. Two sets of chickens were painted on the surface. The two exhibits came with the openwork wood cases made under authorization of the Qianlong emperor. The imperial poem written in the forty-first year of the Qianlong reign (1776) was carved on the case, which documented the journey of his connoisseurship. The numbering system produced by the 'Inventory committee of the Qing court' suggested that this piece was originally stored in the curios box located in Yangxin hall, Forbidden city.

Tracing back to the Archives of the Imperial Workshops (Huojidang) based on the seal mark reads, "bingsheng"(1776). The record revealed that the imperial kiln located in Jiangxi Province had produced copies of the chicken cups at the same year. Comparing to the originals, copies from the Qianlong reign presents a fuller shape with modified decorations. The imagery of a child and chickens was inspired by the story "Jia Chang training fighting chicken" from the Tang dynasty. The same imperial poem was carved on the wood box of both Qianlong's copy and the originals from the Ming dynasty. The 'month of mengchun' marked on the case indicated that it was only six months apart from the November when the copies had been produced. The evidence suggested the possibility that the Qianlong emperor took inspirations from the old collection to create new artworks with various styles.

"The finest objects will disappear, and the glamour might change in a trice. As I've always borne the qi poem at heart, therefore cannot indulge myself in comfort." The Qianlong emperor took "qi" poem written by Yuan Gusheng in the Tang dynasty to serve as a metaphor of the "Tang Wu revolution". The copies had been made in the Qianlong reign revealed the emperor's intention that he had taken history as references and to motivate himself in becoming a wise lord.

Yu Zhi Shi Chu Ji

- Imperial Poem, volume 1

- Wrote by Gaozong, compiled by Jiang Pu and others, Qing dynasty

- Qing court manuscript in black-lined columns, the 14th year of Qianlong reign (1749)

- Portrait of 39-year-old Emperor Qianlong

The Imperial Poems (volume 1), (volume 2) and (volume 3) were each final-edited in year 1749, 1759 and 1771. Base on this idea, the assumption can be inferred that the portrait placed on the opening page of each volume was done when Emperor Qianlong presumably 39. 49 and 61 years old. This was the most accomplished and glorious years of the Qianlong reign. Not only the personal impression was formed by having royal portraits drawn, but also the idea to build up a brand name or style of the emperor was concealed by the action.