The printing of book illustrations rendered on woodblocks was executed in monochrome and duotone; the former (in black) was preferred for its relatively easier application, while the latter (in black and red) was employed to demonstrate the printmaker’s craftsmanship. During the Wanli reign of the Ming dynasty the print shops run by Min Chiji and Ling Mengchu in Wuxing ventured into polychrome printing, and their il-lustrated books were well received by the market. The polychrome technique was followed by the advent of douban (assorted block) color printing, which required the engraving of three or four dozens of smaller blocks, and gonghua (blanked stamping) overprinting, one that would produce protruding patterns and create low relief effects. Of the books printed at this time, the Luoxuan Biangu Jianpu (Trumpet Vine Pavilion’s Stationery Catalogue) carved by Wu Faxing of Jiangning and the Shizuzhai Shuhuapu (Manual of Painting and Calligraphy from the Ten-bamboo Studio) by Hu Zhengyan of Jingling were the most prominent representative works of the printmaker’s ingenuity. Their innovative techniques were delicate, complex, and rich in literary character and spirit, and douban and gonghua were soon to drive the market to supply more multi-colored overprint works.

While Western iconography was introduced by the Italian Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) during the late Ming, it was not until the Kangxi reign of the Qing dynasty when the engraving of copperplate images was put into practice, and the origin of which being the dialogues on visual art between the emperor and the Jesuit priest Matteo Ripa (1682-1745). After much trial and error, Ripa was able to produce his etched version of the Bishu Shanzhuang Sanshiliujing Shitu (Thirty-six Views of the Summer Resort, with Poems and Illustrations), based on an earlier woodcut rendition, and his work is considered the first set of European-style copperplate engravings in China. The copperplate engravings produced during the Qianlong reign to document his military conquests are, too, fine examples of producing images on paper.

The technique of printing from lithographic lime stones was introduced to China after mid-Qing by foreign book traders. As lithography was initially created to be a less expensive method of reproducing images, it soon won the favor of many publishers, who, out of concern for business gains, strived for low-cost, high-yield, and express printing of pictorials and illustrated books. However, the quality of the lithographically printed illustrations was not as delicate and impressive as that of their counterparts produced with the woodcut and etching techniques.

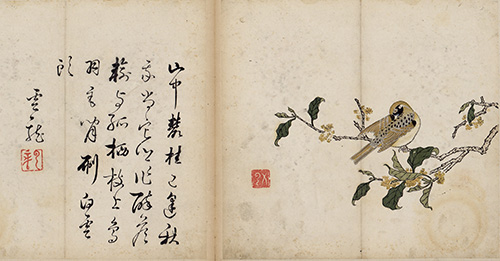

Shizuzhai Huapu - Lingmao Pu

- Manual of Painting from the Ten-bamboo Studio: Birds and Animals

- Edited by Hu Zhengyen, Ming dynasty

- Multicolor imprint of the late Ming dynasty

Shizuzhai Shuhuapu

- Manual of Painting and Calligraphy from the Ten-bamboo Studio

- Edited by Hu Zhengyen, Ming dynasty

- Reprint of 1879 by the Jiaojing Shangfang Studio, Guangxu reign, Qing dynasty

The Shizuzhai Shuhuapu, edited by Hu Zhengyen (c. 1580-1671) from the late Ming dynasty, is a collection of large-size prints created with watercolor woodcut blocks using douban (assembled block) printing technique. The douban technique, which originated in the last years of the Ming dynasty, is a printing approach building upon the basis of painting colors onto woodcut blocks. During the printing process, the color settings of the draft illustration are separately imitated and carved into tens and even hundreds of small wood blocks. These wood blocks are then fixed into their positions with paste, and subsequently go through either filled-in or layer printing process from light to dark color with the use of ink, paint dye, and paste.

The Shizuzhai Shuhuapu from the Museum’s collection consists of twenty six leaves in total; among these twenty two leaves make up the Lingmao Pu, while the remaining four leaves belong to the Shuhua Ce. Judging from its bibliographic attributes this copy appears to comprise both the original version from the late Ming dynasty and the reprint by the Jieziyuan Studio dating in the 23rd year of the Jiaqing reign (1818) of the Qing dynasty. The painting shown here is taken from the Lingmao Pu, showing a seal in the center of the painting with the characters “Wuyun.” The subject is a lifelike close-up depiction of a bird resting on a branch of osmanthus in a posture of turning the neck to clean the feathers on its wing. The brush strokes used here exhibit the “outlines filled with colors” method, showing a style reminiscent of Song dynasty paintings. The matching title in cursive script likely belongs to the first print version from the Chongzhen reign in late Ming dynasty. Among the Shizuzhai Shuhuapu, the Lingmao Pu is considered to be a work from later periods, with tasteful and beautiful use of color as well as excellent and elegant knife work. Compared to other manuals, the craft of imprinting for this work is more complex and mature.

另The other work is from one of the leaves in Shuhua Ce. The subject of the painting is a bird resting on a branch as it feasts upon the fruits with its beak. The work is painted with “outlines filled with colors” method, with the position of the branch on the surface of the leaf closely resembling reality. There is a rich variety of shades of colors on the oriole and of brush strokes of the lines. The composition of the painting is steadfast with reminiscence of Song dynasty works. The seal spells out the characters “Maolin.” The title “Zaici Baoshan” is written in running script, along with a seal with the characters “Shizuzhai Shuhuaji.” Looking at the traces of adhesives and fold crease present at both the center of the painting on the album leaves and on the paired title, it is assumed that the first print was done in butterfly-style album mounting, but later owners switched to five-inlay style album leaves during a remounting process for purpose of preservation. (Hong Shun-hsing)

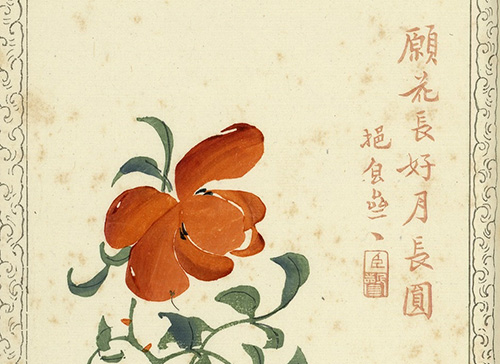

Wenmeizhai Shijian Pu

- An Album of Poetry-writing Papers from the Wenmeizhai Studio

- Edited by Jiao Shuqing; illustrated by Zhang Zhaoxiang and Wang Zhensheng, Qing dynasty

- Multicolor imprint of 1911 by the Wenmeizhai Studio in Tianjin, Xuantong reign, Qing dynasty

Wenmeizhai Shijian Pu is a compilation of 100 floral paintings color-printed on special paper sheets using doban and gonghua techniques. During the late Qing, reputed painters such as Zhang Zhaoxiang (1852-1908) and Wang Zhensheng (1842-1922) were invited to tender their works by Jiao Shuqing (1842-?), owner of the Wenmeizhai Studio in Tianjin.

On the left is a painting of lily magnolia by Zhang Zhaoxiang with his given name sealed at the bottom. Zhang (style name Hean) studied the mogu (or boneless) style of washes of Yun Shouping (1633-1690) and gained fame in Tianjin for his flower paintings. The bud of lily magnolia resembles the head of a brush and the blossom is as big as a cup. Jiao Shuqing asked the technicians to meticulously apply various tones in exact order for the flowers and leaves using the doban technique, exemplifying the precision and intricacy of color-printing technology.

On the right is the work by Wang Zhensheng (style name Shaonong, soubriquet Lanke Shanqiao). Granted the degree of jinshi (a successful candidate in the imperial civil service examination) in 1874, Wang specialized in flower-and-bird paintings as well as calligraphy. In “Yuan Huachanghao Yuechangyuan (May the flowers remain blooming and the moon stay full)” the Capparis bodinieri and its yellow fruit were used to symbolize the wish for a long-lasting relationship. (Hsu Yuan-ting)

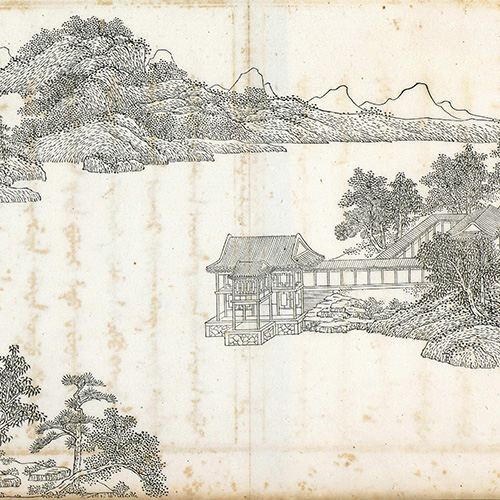

Yuzhi Bishu Sanzhuang Shi (Bingtu)

- Imperially Produced Poems for the Summer Resort, with Illustrations

- Written by Emperor Kangxi, Qing dynasty; illustrated by Shen Yu, Qing dynasty; engraved by Ma Guoxian (Matteo Ripa) of Italy

- Imprint in red and black by the Wuyingdian Imperial Printing Office in 1713, Kangxi reign, Qing Dynasty

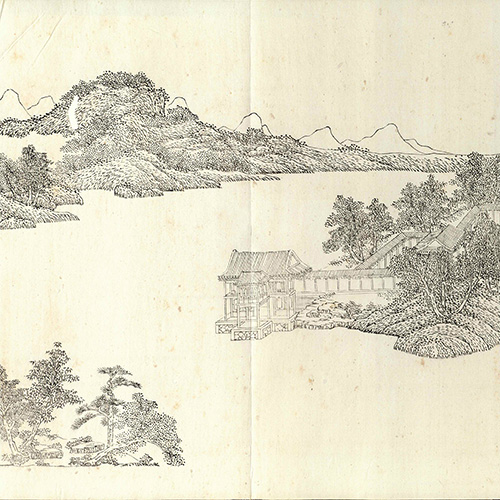

Yuzhi Bishu Sanzhuang Shi (Bingtu)

- Imperially Produced Poems for the Summer Resort

- Written by Emperor Kangxi, Qing dynasty; illustrated by Shen Yu, Qing dynasty; engraved by Zhu Gui and Mei Yufeng, Qing dynasty

- Manchu imprint of 1713 by the Wuyingdian Imperial Printing Office, Kangxi reign, Qing dynasty

Yuzhi Bishu Sanzhuang Shi (Bingtu)

- Imperially Produced Poems for the Summer Resort, with Illustrations

- Written by Emperor Kangxi, Qing dynasty; responded in the same rhyming sequence by Emperor Qianlong, Qing dynasty; illustrated by Shen Yu, Qing dynasty

- Imprint in red and black by the Wuyingdian Imperial Printing Office in 1741, Qianlong reign, Qing dynasty

The summer resort at Rehe is the largest remaining imperial garden from the Qing dynasty in China today. The facility was built in the 42nd year of Kangxi reign (1703). The temporary imperial residence was used for short stays and respite by Qing emperors during their hunting expeditions in autumn. After his ascension to the throne, Qianlong continued to work on its expansion, making the resort even more magnificent and impressive. In the 51st year of Kangxi reign (1712), the emperor selected thirty six major scenic sites across the resort; each was given a name in four characters and accompanying poetry compositions, as well as an illustration drawn by court painters. There was one poem for each of the sites, and one illustration for each poem. These writings with poetic touches and illustrations focusing on details were meant to demonstrate the harmony between heaven and men through the natural landscape and building architecture at the resort.

The drafts of all the illustrations were done by Shen Yu, and the Imperial Printing Office at the Wuyingdian Palace embossed and printed two versions, one in the Machu script and the other in Han Chinese. The illustrations for the Chinese version were created by a team of court painters led by the European missionary Matteo Ripa (1682-1745). The artists employed the Western copperplate etching technique to recreate the illustrations shown on the drafts, becoming the first instance during the Qing Dynasty of applying the art of copperplate engraving to the production of imperial prints. The thirty six illustrations for the Machu-script version, on the other hand, were handled by Zhu Gui (c. 1644-1717) and Mei Yufeng by using wood engraving techniques. In the 6th year of the Qianlong reign (1741), the emperor made his first return visit to the summer resort since assuming the throne. Recalling the short period of time during his childhood years that he spent with Emperor Kangxi at the resort, he came up with the idea of reprinting the Bishu Sanzhuang Shi. He responded in the same rhyming sequence to each of the thirty six original poems created by Emperor Kangxi, and retained the original wood engravings by Zhu Gui for the illustrations.

The works on view are the Manchu and Chinese versions from the Kangxi reign, as well as the illustrations of “Xiling Chenxia (Morning Mist on West Ridge)” and “Fengquan Qingting (Clear Listening of the Windy Springs)” from the Chinese version made during Qianlong’s time. The copperplate etchings from Kangxi’s Chinese version show a clear gradient from light to dark, while the objects of the scenes appear vivid and lifelike, demonstrating a strong sense of reality. The wood engraved illustrations from the Machu version are elegant and beautiful, highlighting the emphasis on spontaneous expression in traditional paintings. The illustrations in Qianlong’s Chinese version were reprints of the original wood engravings by Zhu Gui. However, due to the age of Zhu’s original carved printing blocks, there are places in the reprinted illustrations showing signs of wear and tear.

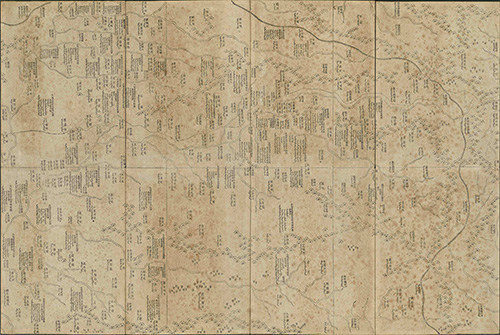

Shengjing Yutu

- Map of Shengjing

- Written by Hong Xiang, et al., on imperial order

- Copperplate print of 1778, Qianlong reign, Qing dynasty

Originally named Shengjing Jilin Heilongjiang Dengchu Biaozhu Zhanji Yuto, the map was produced in 1776 when Emperor Qianlong of the Qing dynasty commanded General Hong Xiang to make a grand picture of the mountains, rivers, roads and villages of northeastern China, including their names in Manchu and Han Chinese scripts. A draft was submitted to the Imperial Map-making Department for copper engraving, and it was finally completed in 1778. The map contains 144 frames. In addition to place names in both languages, the key battlegrounds on which the Ming and Qing armies once fought were marked and annotated. The characters of the right rows are Han Chinese, and those of the left Manchu. The map is divided into four regions: Yuan, Yuan, Liu and Chang. Featured here is an imperial edict of Emperor Qianlong, together with his poetic composition and a map of Shengjing. Copperplate engraved and printed, the map shows clear lines and sharp characters. It is an important source of information for those who wish to learn the topography of northeastern China in the 17th and 18th centuries.

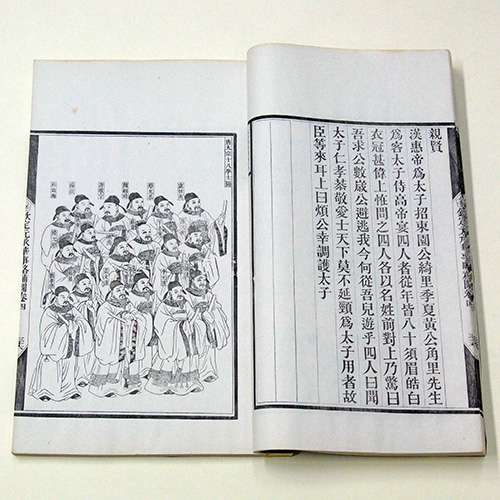

Qinding Yuan Wangyun Chenghua Shilue Butu

- Imperially Endorsed Summaries of the Actions of a Crown Prince, with Supplemental Illustrations

- Written by Wang Yun, Yuan dynasty

- Imprint of 1896 by Zhang Zhidong in Suzhou, Guanxu reign, Qing dynasty

Qinding Yuan Wangyun Chenghua Shilue Butu

- Imperially Endorsed Summaries of the Actions of a Crown Prince, with Supplemental Illustrations

- Written by Wang Yun, Yuan dynasty

- Lithographed imprint of 1896 by Zhang Zhidong in Suzhou, Guanxu reign, Qing dynasty

Chenhua Shilue is a work on rulership, written by the imperial censor Wang Yun (1227-1304) of the Yuan dynasty for Kublai Khan’s second son Zhenjin (1243-1286). In 1895, the Qing emperor Guangxu (1871-1908) ordered the Hanlin academicians of the Southern Library to make annotated illustrations for the work, paragraph by paragraph. Subsequent work, which includes the making, engraving and printing of such illustrations, was later handed over to Zhang Zhidong (1837-1909). All of the accomplished painters in ther Suzhou area were invited to draw the illustrations. Several dozens of engravers were gathered from Suzhou, Shanghai, Yangzhou, Guangdong and Hubei. All of the required illustrations were completed after nine months at the cost of seven thousand taels of silver.

The 40 illustrations draw reference from antiquarian nomenclature. The lines and patterns are fine and graceful, which make them more difficult to carve than the written words. The all-popular and already-mature lithographic printing technique was highly valued in the production process. In the end Zhang presented the woodcut and the lithographed imprints to the emperor. The National Palace Museum is home to both versions. They are illustrative of the combination of traditional printmaking and the application of new techniques.