The making of woodcut prints begins with the drawing of images. A painter would first sketch the illustra-tions on paper, and the engraver would then work the illustrations into blocks of wood, which are sent with other woodblocks with text to the press for printing and binding. In earlier times, book illustrations were meant to interpret the meaning of texts. Between mid-Ming and early Qing renowned artists and court painters like Chen Hongshou, Jin Guliang, Xiao Yuncong, and Ren Weichang, were involved, at the invitation of book printers, in the sketching of such illustrations. Applying their individual aesthetic styles to the re-interpretation of texts, the illustrations eventually became unique, extraordinary works of art. With the painters’ originals and their woodcut prints juxtaposed, the audiences should be able to look into the simi-larities and differences between the artists’ brush renditions and the printed book illustrations, especially when they address the same subject matters.

In addition, among goods available in the marketplace mutual influences between book illustrations and handicraft products were also detected. Illustrations by famous artists were often adopted as decorative pat-terns on bamboo carvings, porcelains, lacquer wares, ink stones, and ink sticks. It was in this way that the influence of the composition of book illustrations had been extended to commodities of all sorts, whether they were made for the imperial court or for the masses, for domestic distribution or for export markets, making woodcut prints a source of inspirations for creative cultural products.

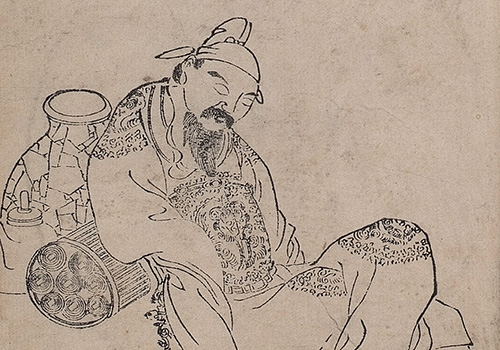

Nanling Wushuang Pu

- Register of Unparalleled Historical Figures

- Compiled and illustrated by Jin Guliang, Ming dynasty

- Imprint of the Kangxi reign, Qing dynasty

The Wushuang Pu, also known as the Nanling Wushuang Pu, is a collection of 40 illustrations depicting se-lected historical figures spanning from the Han to the Song dynasties. All the illustrations were done by Jin Guliang. Since the deeds of these individuals were considered second to none, the work was subsequently named Wushuang Pu. Mao Qiling from the early Qing dynasty period once praised the illustrated Wushuang Pu for embodying “three perfections,” as a book, a painting, and a poetic work. The depiction of Li Qinglian is more or less identical to the composition in the original version, with the exception of the addition of one extra lotus flower in the commentary on the back of the painting, which corresponds to Li Bai’s honorific title of “Qinglian Jushi,” meaning literally the “Householder of Azure Lotus.” (Hsu Yuan-ting).

Petal-shaped carved lacquer case with agricultural illustrations

- 18th Century, Qing dynasty

This petal-shaped case is decorated with landscape, crane, deer and eight treasures on the side. Its cover is also petal-shaped, and decorated with agricultural scenes. In the foreground, the farmland is covered with water. A farmer wears bamboo rain hat, rolls up his trouser, and hurries a water buffalo to pull the stone roller to plough the field. The buffalo moves along as it turns its head. Winding waterways are extended behind the field. A boy rides on a water buffalo by the river, while farmhouses are located on the other side under shades, with a bridge across the waterway. The mountains afar are laid in parallel. The scene shows a diligent farming family living and working in a peaceful setting, and the composition is similar to that of the Gengzhi Tuce (Illustrations of Agriculture and Sericulture) by Leng Mei of the Kangxi reign.

The patterns on the case are revealed by ridding of layers of lacquer in various colors. The upper red layer depicts figures and landscape, the green layer in the middle is used for the river, and the bottom yellow layer represents the background and the sky. It is well constructed and exquisitely carved. Physical farming by emperors was an important part of the ritual worshipping ancestors. It was required by Qing rites that em-perors attending a ritual at the Xiannongtan (Temple of Agriculture) in mid spring, and physically farm the land at the Guangengtai (Platform for the Observation of Farming) to show their commitments to land cultivation and agricultural tilling. (Chen Hui-hsia)

Wucai porcelain plate with illustrated figures from Shuihu Zhuan (Water Margin)

- Kangxi reign, Qing dynasty

Characters from plays, novels and prints often appeared as decorative patterns on porcelains of the late Ming and early Qing. This wucai ceramic plate has wide opening, arc-shaped side and short circular heels. Inside, the bottom features the images of three outlaws out of the 108 from Shuihu Zhuan.

Huyan Zhuo, nicknamed “Double Clubs,” stands at the center, and by his side is Zhang Shun, the “White Stripe in the Waves.” Opposite the two stands Chai Jin, the “Little Whirlwind.” Tags with their names in gold and red are tied to their waists. (Huang L anyin)

Zhang Shengzhi Xiansheng Zhengbei Xixiang Miben

- Zhang Shenzhi’s Genuine Illustrations of the Ro-mance of the West Chamber

- Written by Wang Shifu, Yuan Dynasty; illustrated by Chen Hongshou, Ming dynasty; engraved by Xiang Nanzhou, Ming dynasty

- Imprint of the late Ming dynasty

During the Ming dynasty many annotated, commentated and adapted versions of the Xixiang Ji by Wang Shifu of the Yuan dynasty appeared, and they became widely popular. The Zhang Shengzhi Zhengbei Xixiang Miben is a collective commentary of the late Ming by Zhang Daojun from Shanxi and 32 literati in Hangzhou, including the noted playwrights Meng Chengshun and Shen Zizheng. The illustrator Cheng Hongshou (style name Zhanghou, pseudonym Laolian) was born in Zhuji in Zhejiang Provice. He was a painter of the late Ming, famous for his figure renditions. Not only did he collaborate with the others in the writing of the commentaries, but also painted six illustrations for the work, including “Yingying Xiang,” which was placed before the body text, as well as “Mucheng,” “Jiewei,” “Kuijian,” “Jingmeng” and “Baojie,” which were taken from the different fascicles to highlight the storyline.

The illustration “Kuijian” describes a very unique scene, and it is demonstrative of the ingenuity of a creative painter. Four screens with flower and bird patterns are placed windingly in a stage-like setting. The female protagonist Cui Yingying is seen attentively reading a letter. The naughty Hongniang places a finger on top of her lips and peeks in from behind the screens. The dramatic and nostalgic styles are seamlessly combined in the elegant postures and clear-cut lines of the illustration. (Hsu Wen-mei)

Bamboo brush holder with carved illustration of a lady reading

- Ju Sansong, Ming Dynasty

The patterns on the bamboo brush holder with carved illustration of a lady reading from the late Ming are inspired by the illustrations from Zhang Shengzhi Zhengbei Xixiang Miben. The carvings on the surface of the pillar-like bamboo are transformed from the two-dimensional illustrations of “Kuijian” and “Baojie.” The contemplating Cui Yingying and the naughty Hongniang are still separated by screens. The four screens and flower-and-bird decorations in Cheng Hongshou’s illustrations, however, are simplified into one screen on the brush holder. Vases and stationary are placed in the scene instead. The characters “Sansong” is carved at the lower right corner of the screen. Zhu Sansong was a famous artist of bamboo carving in Jiading in late Ming; his excellent techniques had drawn many followers.

Another handicraft, a bamboo arm rest from the late Ming with carving of a lady reading, also features patterns from Cheng Hongshou’s illustrations. As the arm rest is long and narrow, the relative positions of the reading Cui Yingying, the screens in the back and the table have all been rearranged with creative ap-proaches. (Hsu Wen-mei)