Introduction

To meet the need for recording information and ideas, unique forms of calligraphy (the art of writing) have been part of the Chinese cultural tradition through the ages. Naturally finding applications in daily life, calligraphy still serves as a continuous link between the past and the present. The development of calligraphy, long a subject of interest in Chinese culture, is the theme of this exhibit, which presents to the public selections from the National Palace Museum collection arranged in chronological order for a general overview.

The dynasties of the Qin (221-206 BCE) and Han (206 BCE-220 CE) represent a crucial era in the history of Chinese calligraphy. On the one hand, diverse forms of brushed and engraved "ancient writing" and "large seal" scripts were unified into a standard type known as "small seal." On the other hand, the process of abbreviating and adapting seal script to form a new one known as "clerical" (emerging previously in the Eastern Zhou dynasty) was finalized, thereby creating a universal script in the Han dynasty. In the trend towards abbreviation and brevity in writing, clerical script continued to evolve and eventually led to the formation of "cursive," "running," and "standard" script. Since changes in writing did not take place overnight, several transitional styles and mixed scripts appeared in the chaotic post-Han period, but these transformations eventually led to established forms for brush strokes and characters.

The dynasties of the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) represent another important period in Chinese calligraphy. Unification of the country brought calligraphic styles of the north and south together as brushwork methods became increasingly complete. Starting from this time, standard script would become the universal form through the ages. In the Song dynasty (960-1279), the tradition of engraving modelbook copies became a popular way to preserve the works of ancient masters. Song scholar-artists, however, were not satisfied with just following tradition, for they considered calligraphy also as a means of creative and personal expression.

Revivalist calligraphers of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), in turning to and advocating revivalism, further developed the classical traditions of the Jin and Tang dynasties. At the same time, notions of artistic freedom and liberation from rules in calligraphy also gained momentum, becoming a leading trend in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Among the diverse manners of this period, the elegant freedom of semi-cursive script contrasts dramatically with more conservative manners. Thus, calligraphers with their own styles formed individual paths that were not overshadowed by the mainstream of the time.

Starting in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), scholars increasingly turned to inspiration from the rich resource of ancient works inscribed with seal and clerical script. Influenced by an atmosphere of closely studying these antiquities, Qing scholars became familiar with steles and helped create a trend in calligraphy that complemented the Modelbook school. Thus, the Stele school formed yet another link between past and present in its approach to tradition, in which seal and clerical script became sources of innovation in Chinese calligraphy.

Selections

-

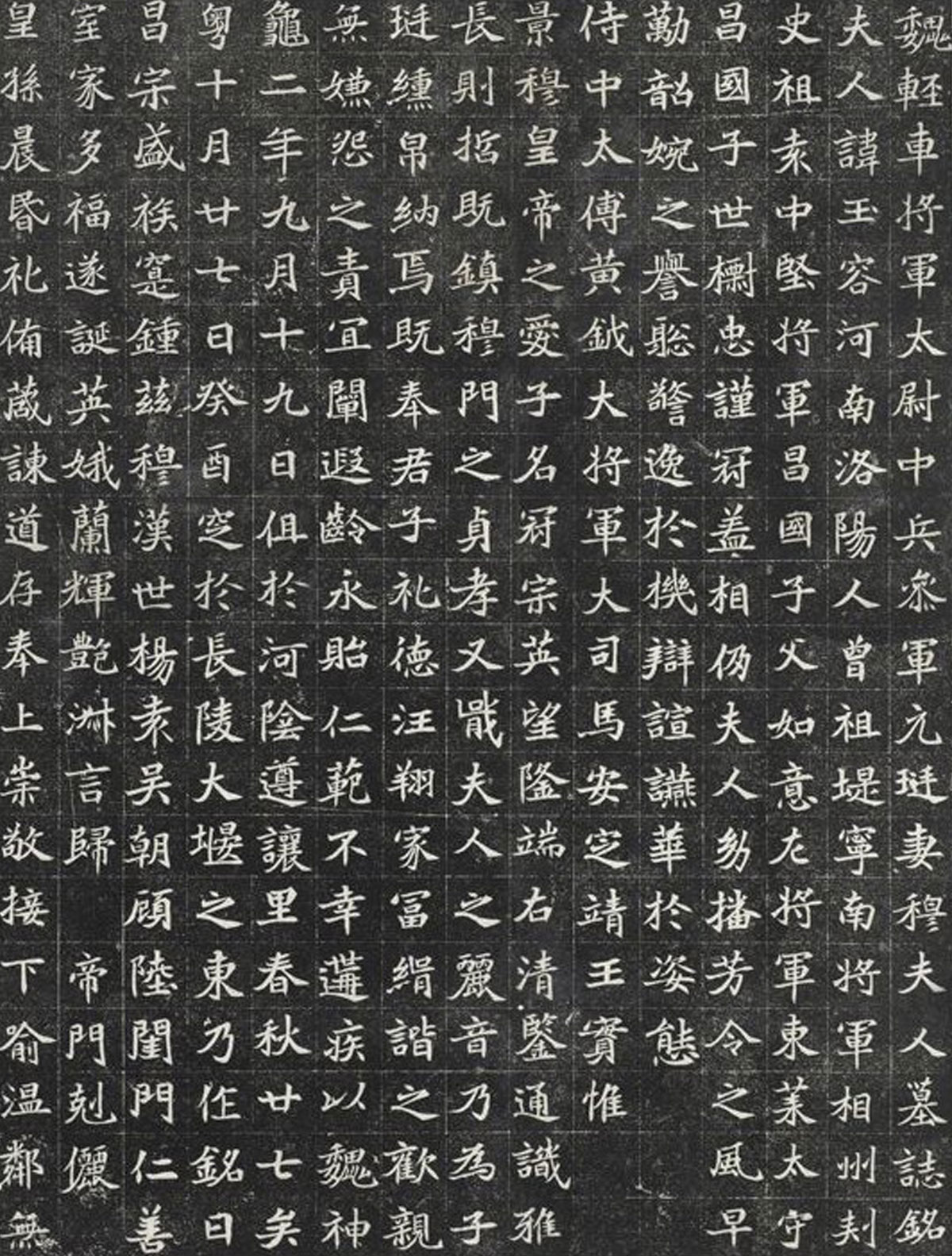

Mu Yurong Memorial Inscription

- Northern Wei dynasty

This memorial inscription, engraved in 519, records the genealogy, familial history, and virtuous character of Mu Yurong (493-519), wife of Yuan Ting (493-519), a member of the Northern Wei dynasty imperial family. Excavated near the village of Nanchenzhuang in Luoyang 1922, this is one of the renowned “Seven Memorial Inscriptions Written for Lovers,” which are now housed in the Stele Forest Museum in Xi’an. The entire piece was written with slightly flattened character structures. Its horizontal strokes rise diagonally rightwards, while its left- and right-falling strokes are expansive, appearing like birds spreading their wings and conveying a sense of uplifting vigor. Most of the brushstrokes begin and end with sharp turns or the revealing of the brush’s tip, leading to the presence of numerous corners and angles. Many of the hooked strokes are triangular or sickle-shaped. When writing the midsections of the lines, the calligrapher employed techniques for rounded turns from the Southern dynasty. The rounded lines demonstrate a merging of calligraphic methods from the Northern and Southern Dynasties, where lithe curvaceousness yields a beauty that is both firm and delicate.

-

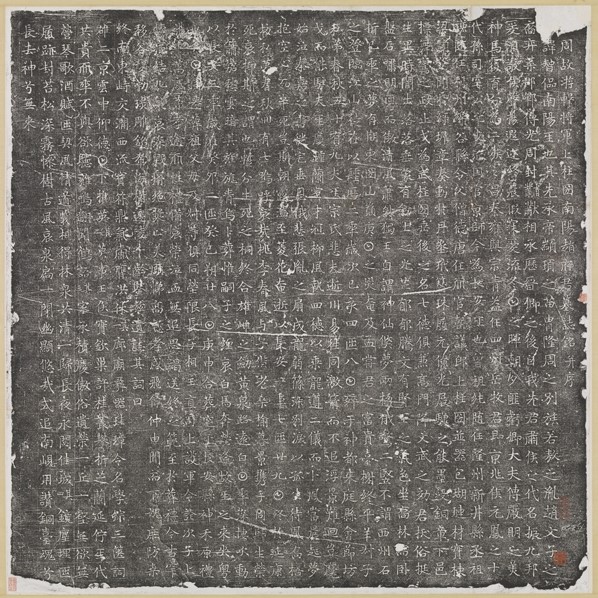

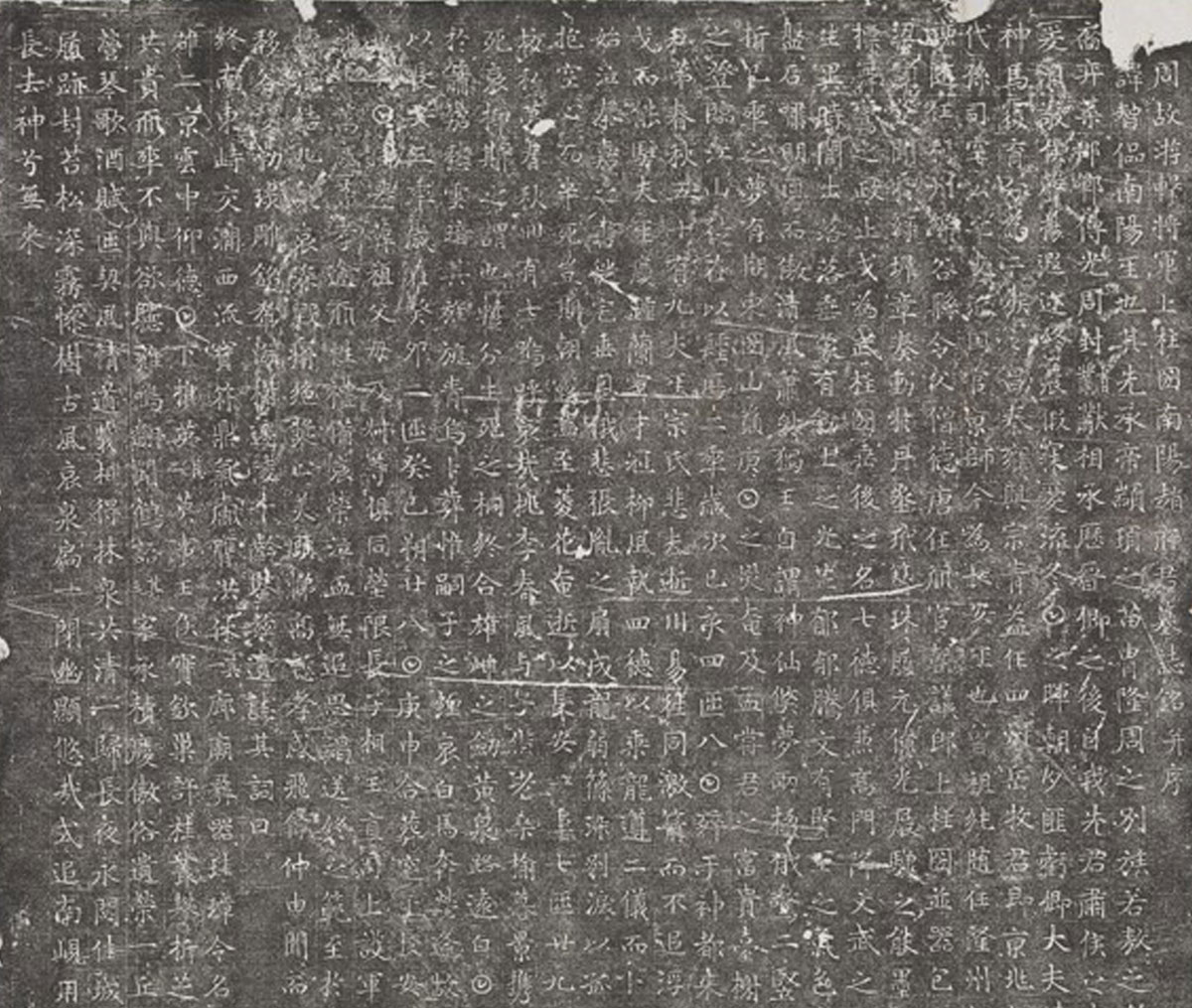

Zhao Zhikan Memorial Inscription

- Wu Zhou dynasty

This memorial inscription, engraved in 703, records the deeds of the late Zhao Zhikan (641-699). It also records how, following the passing of Zhao’s wife (surnamed Zong, 656-702), their son arranged a glorious funeral dedicated to both of his parents before seeing to the reburial of his paternal grandparents and Zhao’s younger brother together in a family burial site. Such grand effort and expenditure reflects how people of the time believed that husbands and wives as well as families at large relied on each other in death just as much as in life. From this belief grew the concept of an ideal final resting place for a clan’s members. The whole inscription was written in semi-cursive regular script (xingkaishu), in a style that shows the influence of Chu Suiliang’s (596-657) “Goose Pagoda Preface for ‘The Sacred Teachings.’” The calligrapher wrote with graceful beauty, and even included characters newly created in that era. This is truly one of the finest memorial inscriptions of the early Tang dynasty.

-

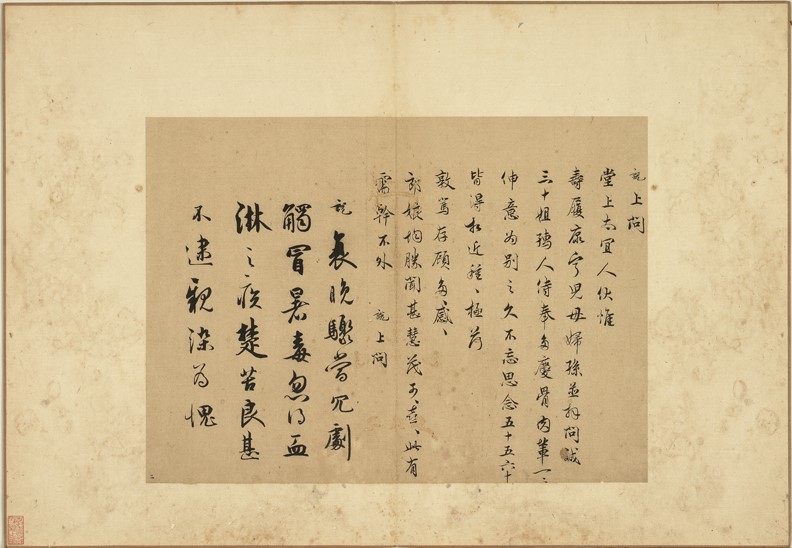

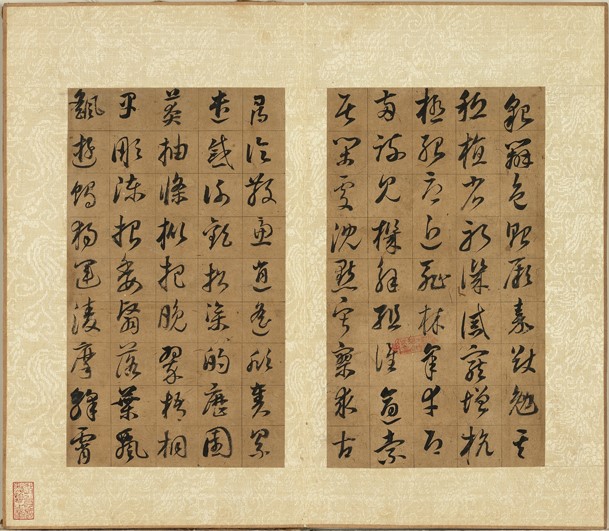

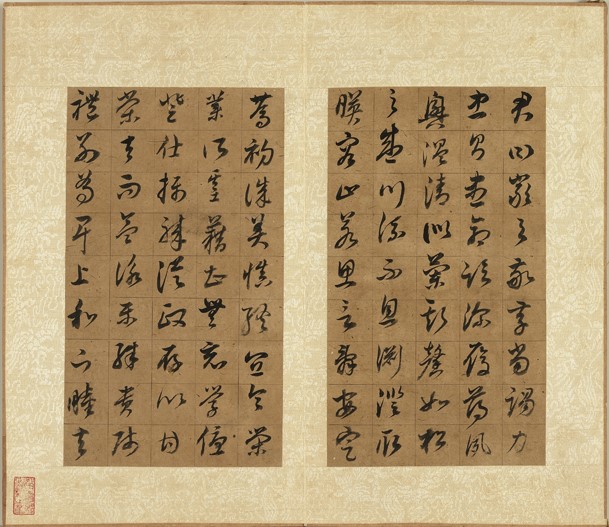

Shangwen Hall Inscription

- Wu Yue, Song dynasty

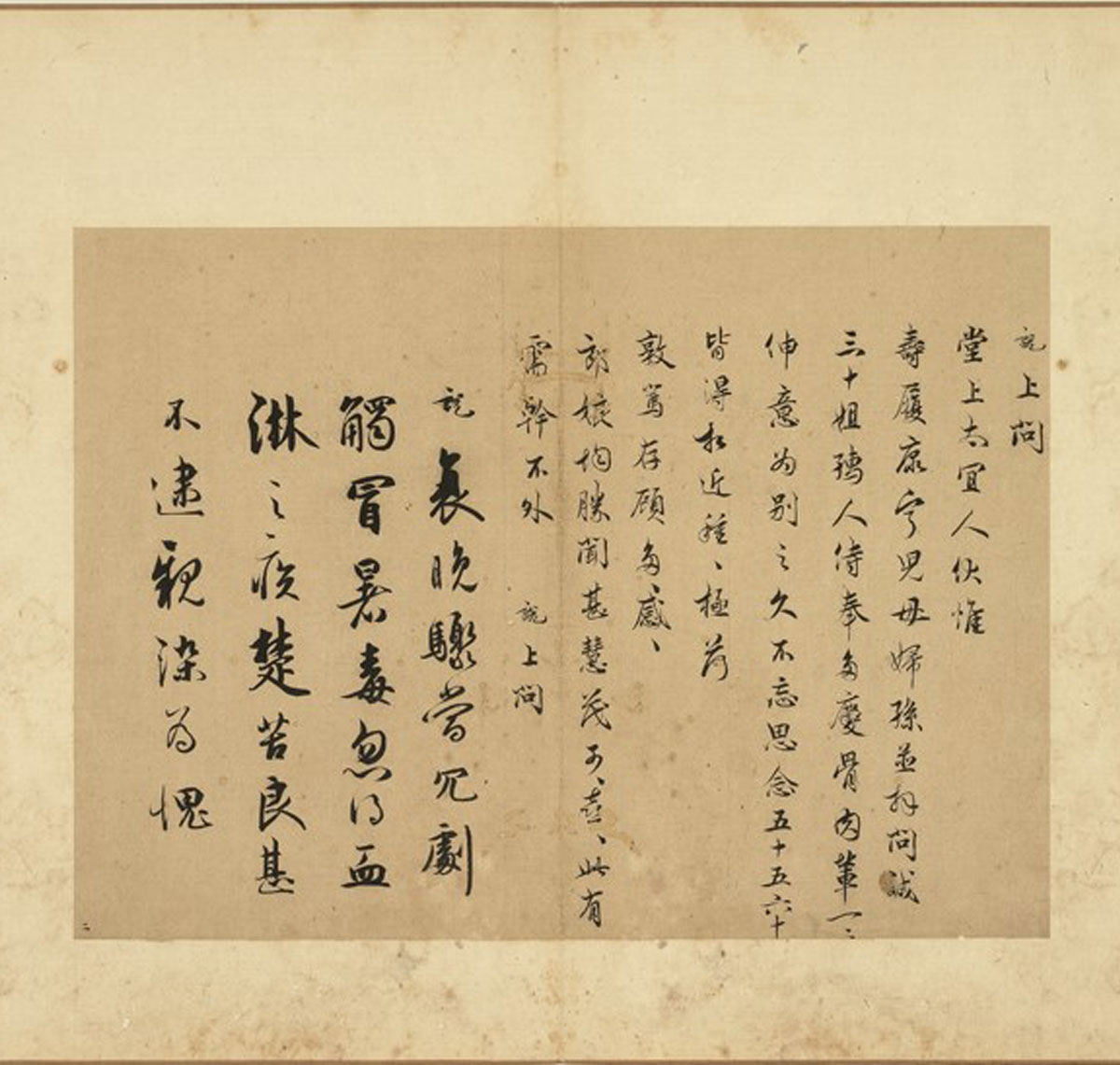

Wu Yue (?-after 1169) was a Southern Song dynasty official, literatus, and calligrapher.

This work is a handwritten letter. In the main body of the text, on the right side, Wu Yue asks after family and friends. This portion was written on Wu’s behalf by scribe who employed sharply pointed brushwork with rounded turns and character structures that change inelegantly. The latter portion of the letter, on the left, is an addendum written in Wu’s own hand, giving updates on recent news and explaining why he was unable to write the first part of the letter himself. In this section, the characters jump in size from large to small, while the brushstrokes alternate between tightness and looseness. While these contrasts are pronounced, the overall flow of the composition is in fact quite orderly. All throughout Wu’s inscription the lines’ forms range fluidly between angularity and roundedness as well as thickness and thinness, demonstrating superior brushwork deeply informed by the spirit of Wang Xizhi’s (303-361) calligraphy.

-

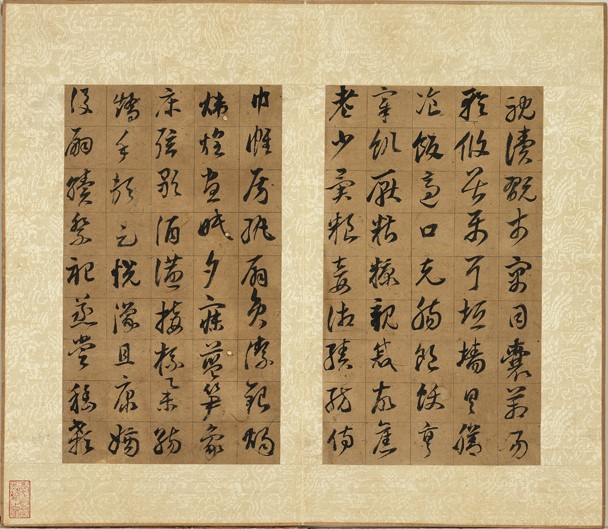

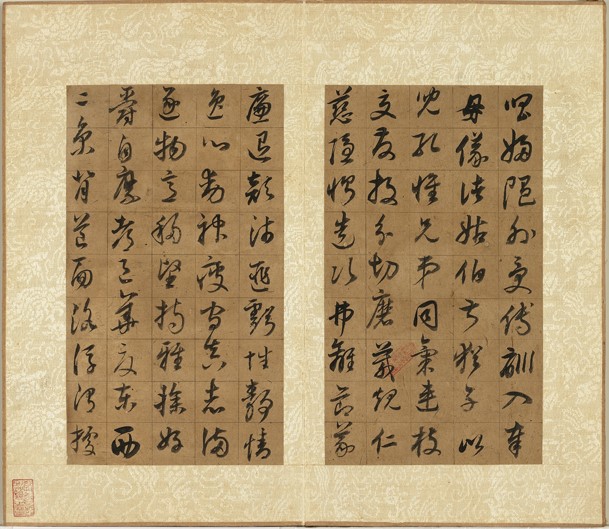

On Lychee Biscuits

- Fan Chengda, Song dynasty

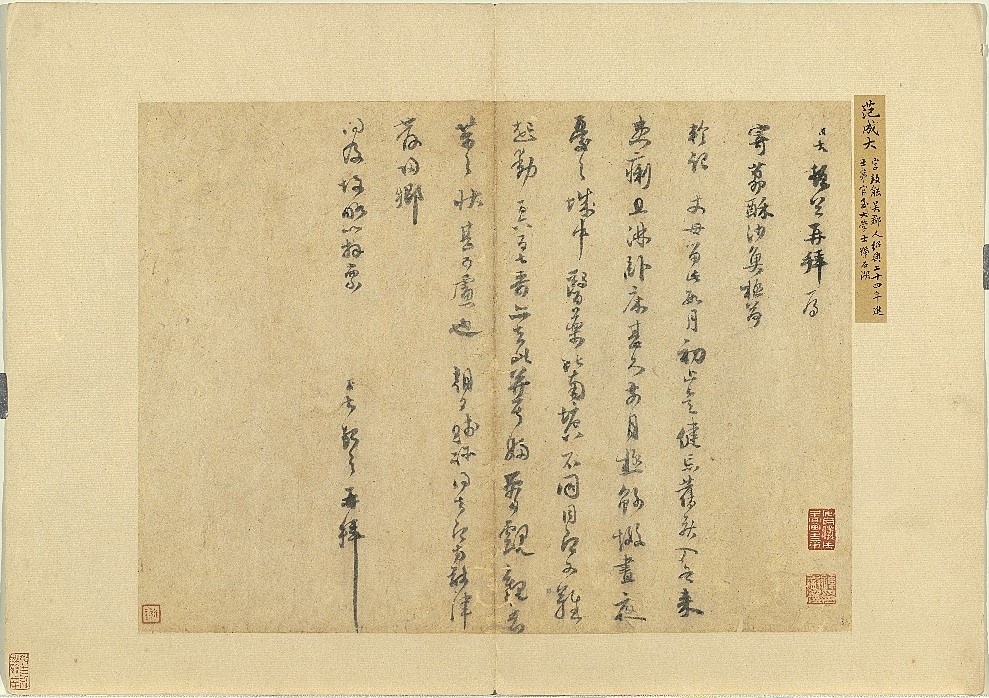

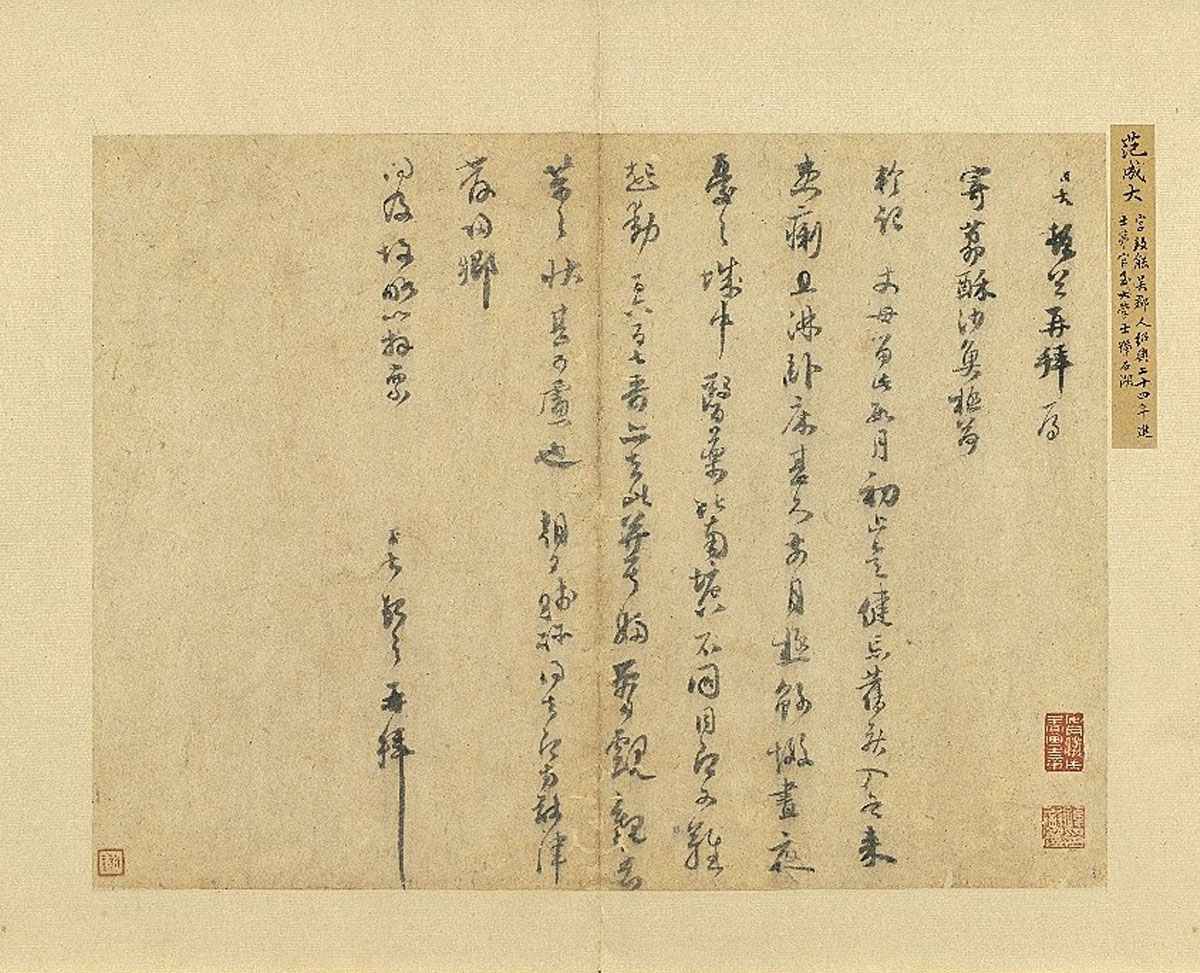

Fan Chengda (1126-1193) was an important politician and literatus who lived during the Southern Song dynasty. He was also an excellent calligrapher, listed among the four masters of the Southern Song dynasty.

This piece was originally written as a letter, its contents revolving around recent events in Fan’s mother-in-law’s life. Its wording is free-flowing and colloquial, expressing sentiments of worry and fondness in simple and straightforward terms. Fan wrote the letter in running-cursive script (xingcao), merging the styles of Su Shi (1037-1101) and Huang Tingjian (1045-1105). In terms of calligraphic techniques, Fan liberally employed rounded turns, exposures of the brush’s tip, and strokes connected with threadlike traces of the brush. His writing was natural, confident, and unembellished. The characters sometimes start large and gradually become small, and other times begin small before expanding. This effect, in combination with alternations in the brushstrokes’ thickness and thinness, gives Fan’s calligraphy an elegant, unostentatious sense of movement and rhythm. This piece’s beauty shines forth in its freshness, mellowness, and earnestness.

-

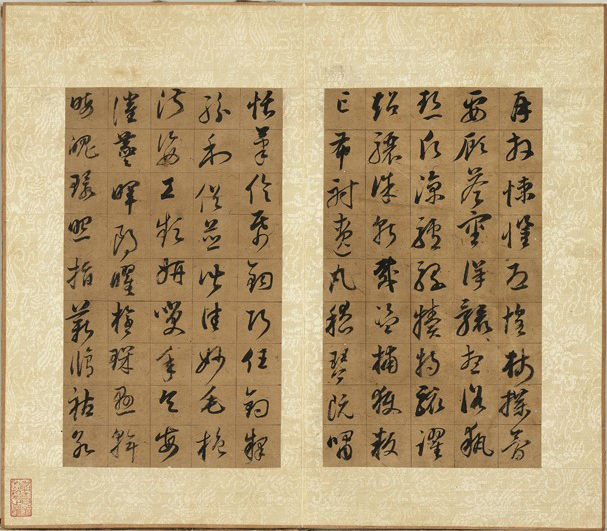

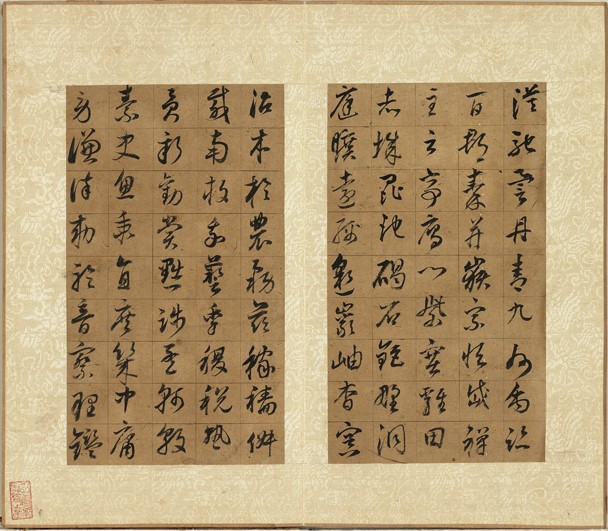

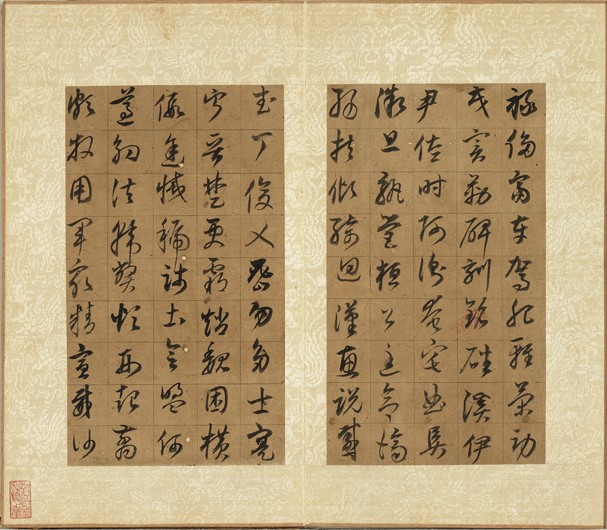

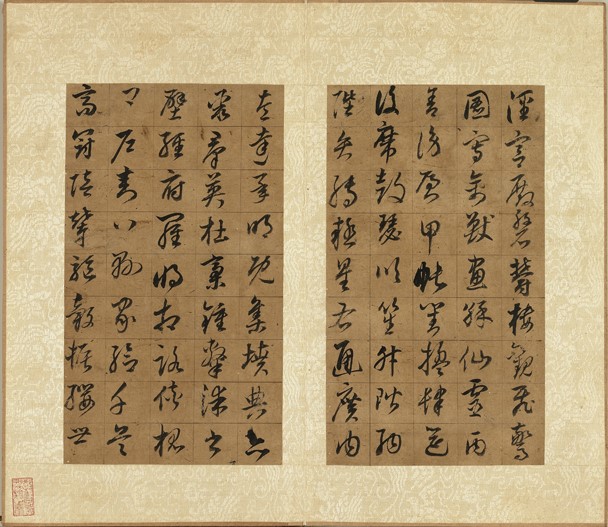

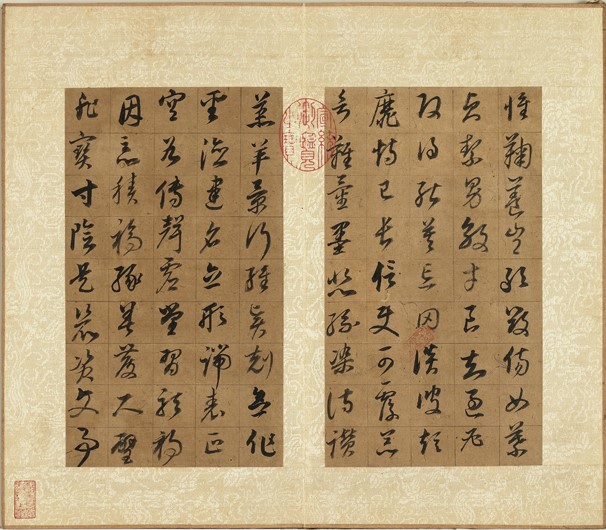

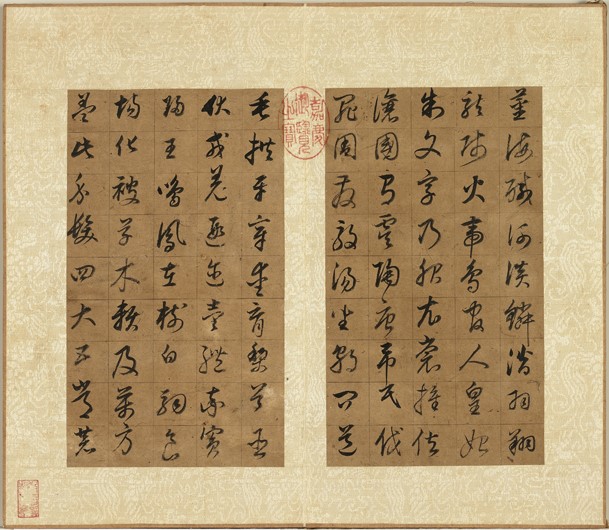

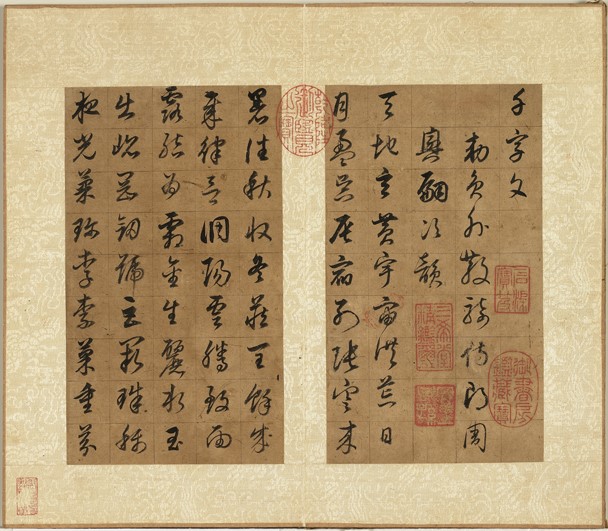

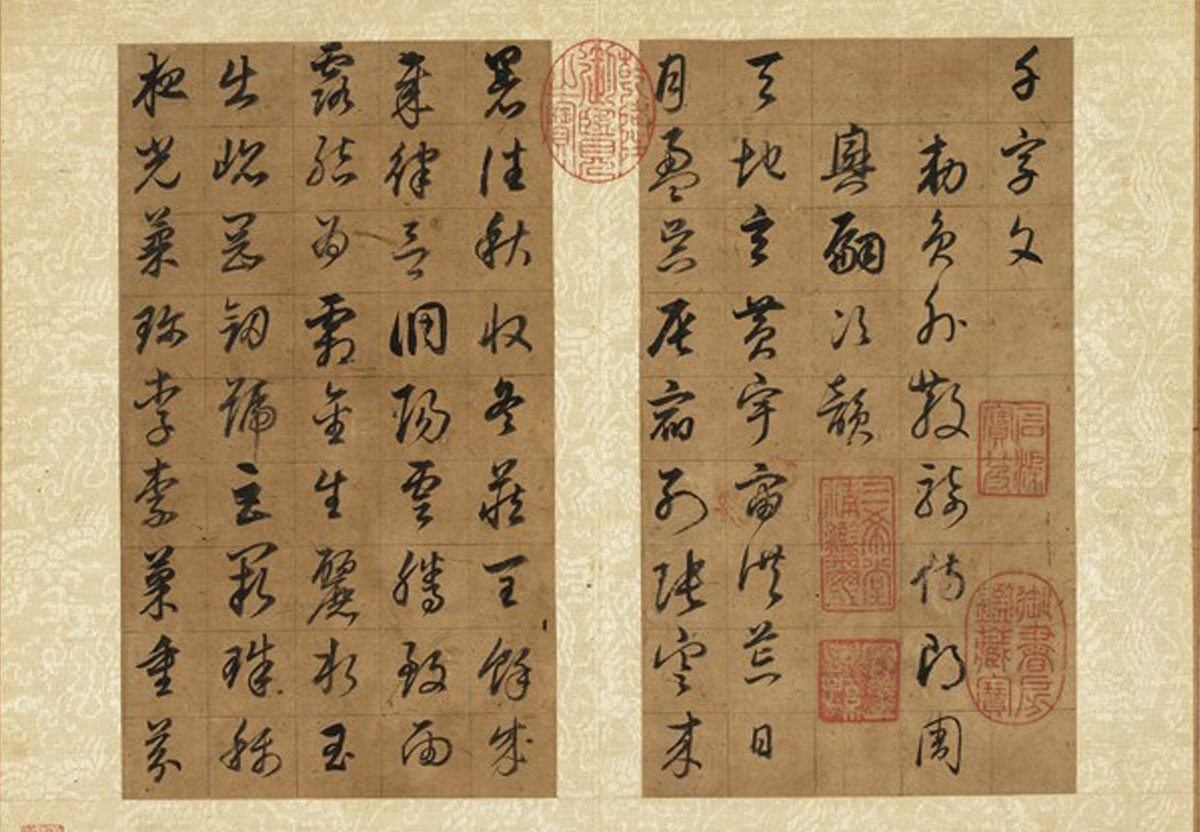

Copy of Ouyang Xun’s Thousand Character Classic

- Dong Qichang, Ming dynasty

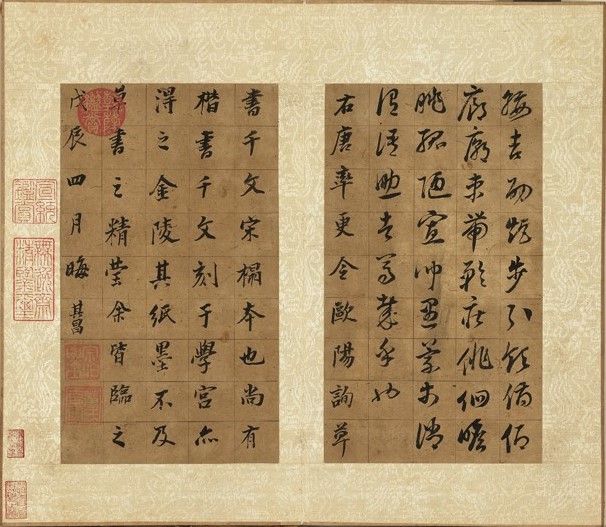

Dong Qichang (1555-1636), whose style name was Xuanzai, was a Ming dynasty official who reached the rank of Director in the Ministry of Rites. Dong was a highly influential calligrapher, painter, connoisseur, and art historian.

According to Dong’s own inscription, this album was written as a copy of “Ouyang Xun’s (557-641) Thousand Character Classic in Cursive Script” in 1628. Dong’s brushwork regularly reveals the brush’s tip, and allows for marked contrasts between rounded and angular as well as thick and thin lines. He wrote in cursive, and yet the characters all stand alone and are similar in size, presented in a composition with remarkably classical sensibilities. The gradual transitions in the ink’s tone from heavy to light lead to the creation of strings of characters that provide a sense of visual cadence. These features reflect Dong Qichang’s masterful calligraphic technique, and his easygoing, confident state of mind.

Exhibit List

| Era | Artist | Work | Format | Dimensions(cm) | Item Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Han dynasty | Cao Quan Stele | Album | 24x15 | 贈拓324 | |

| period | Gu Lang Stele | Framed work | 110x86.5 | 購拓54 | |

| Northern Wei dynasty | Mu Yurong Memorial Inscription | Scroll | 187x63.6 | 贈拓233 | |

| Tang dynasty | Master Longchan Stele | Scroll | 282x97.1 | 購拓245 | |

| Wu Zhou dynasty | Zhao Zhikan Memorial Inscription | Scroll | 212×79 | 購拓360 | |

| Northern Song dynasty | Mengying | The Thousand Character Classic Seal Script Stele | Album leaf | 35.2x36 | 贈拓321-1001 |

| Southern Song dynasty | Wu Yue | Shangwen Hall Inscription | Album leaf | 42.3x61.2 | 故書150-6 |

| Southern Song dynasty | Fan Chengda | On Lychee Biscuits | Album leaf | 42.2x59.6 | 故書240-17 |

| Yuan dynasty | Zhao Yong | Thousand Character Classic in Cursive Script | Album leaf | 33x39 | 故書161-3 |

| Ming dynasty | Qian Bo | Copy of Zhao Mengfu’s Calligraphy of the Bodhisattva Guanyin Sutra | Album leaf | 29.1x36 | 故書306-6 |

| Ming dynasty | Illustrated Guide to an Imperial Edict | Scroll | 158.5x79 | 購拓431 | |

| Ming dynasty | Record of the Building of a New Gilt-bronze Shrine Hall at Yongming Huazang Buddhist Monastery on Mount Da’e | Scroll | 134.5x74.5 | 購拓276 | |

| Ming dynasty | Dong Qi chang | Copy of Ouyang Xun’s Thousand Character Classic | Albumleaf | 22.2x12.7 | 故書207-6 |

| Ming dynasty | Cai Yuqing | The Classic of Filialty | Albumleaf | 23.3x13 | 故書229-13 |

| Republican era | Yu Youren | Elegy of Remembrances of the Second World War | Album | 26.3×18.1 | 購書1500 |