Selections

-

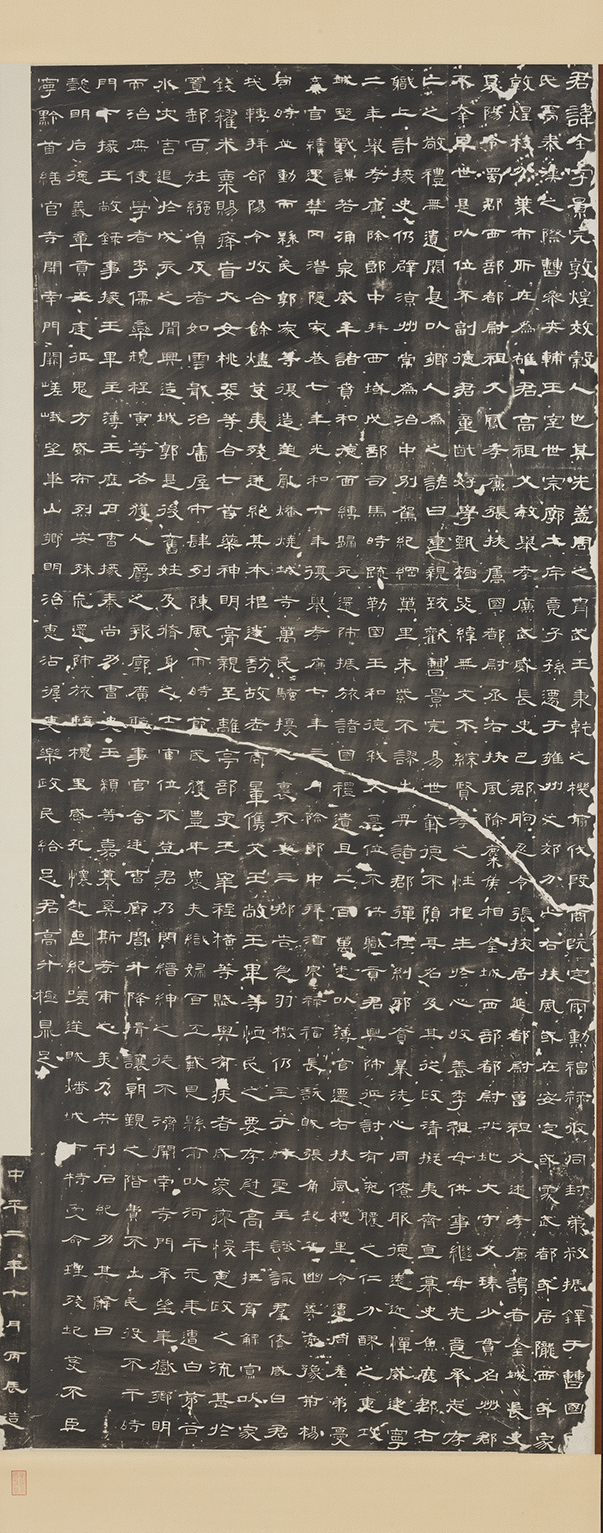

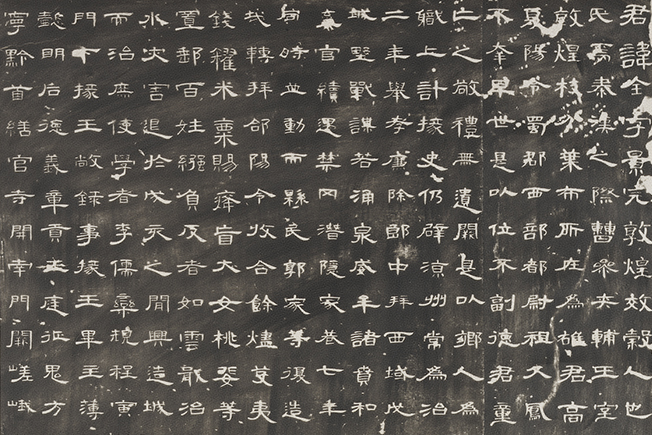

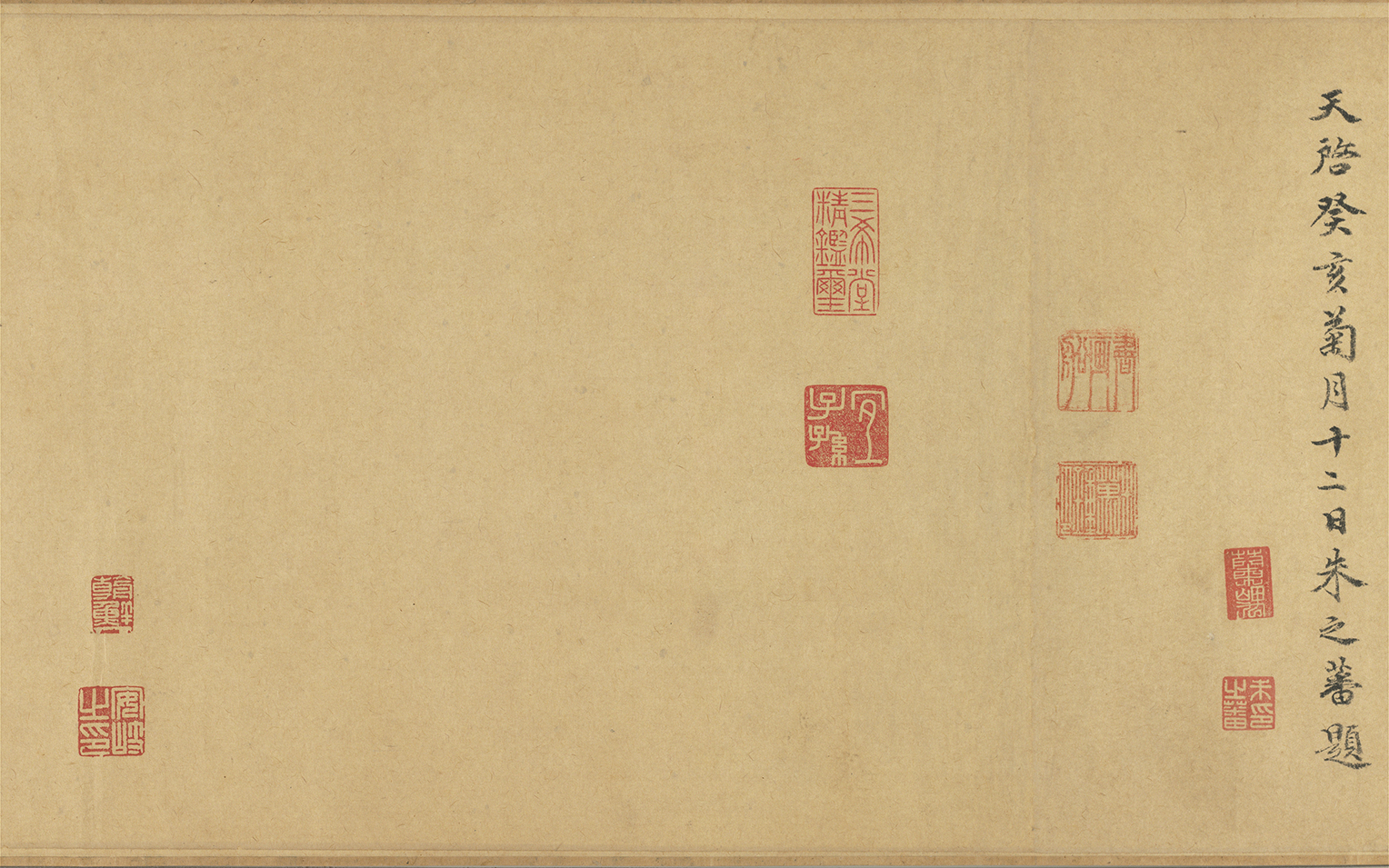

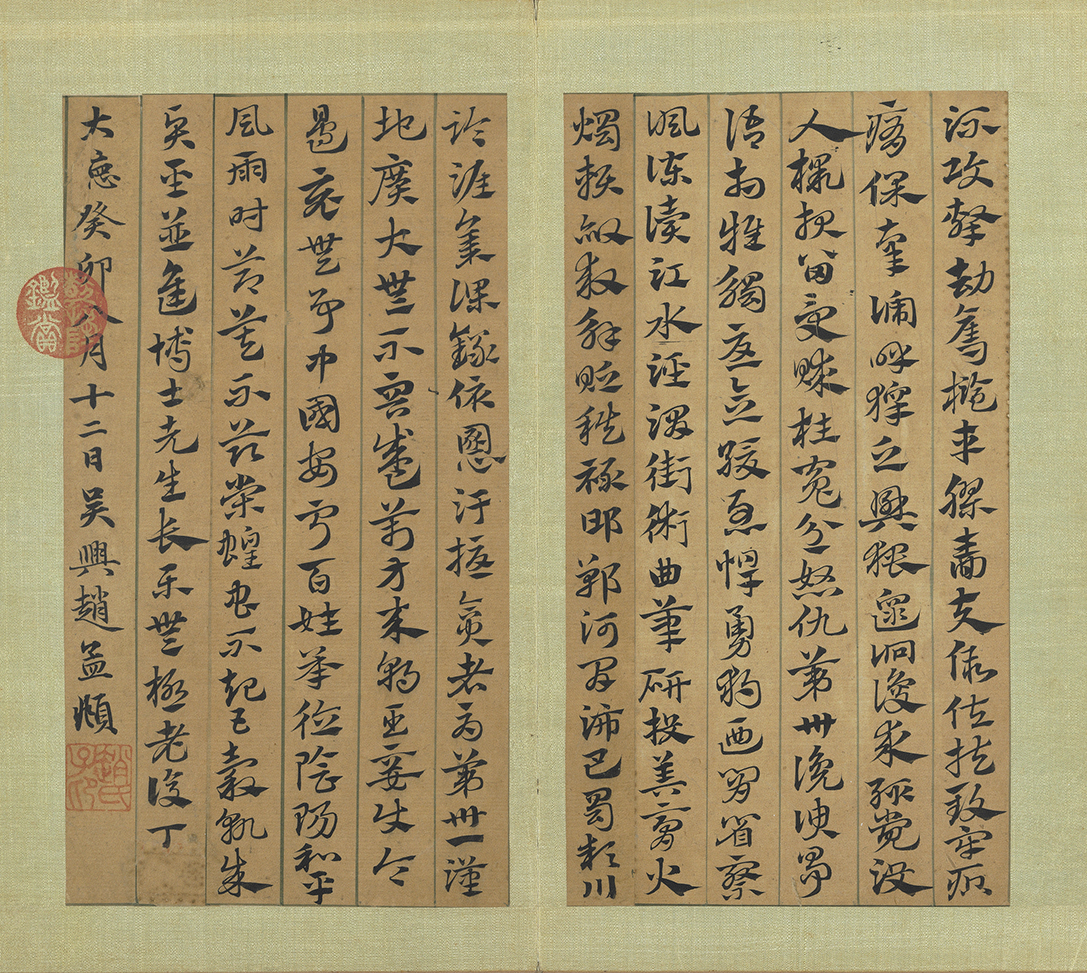

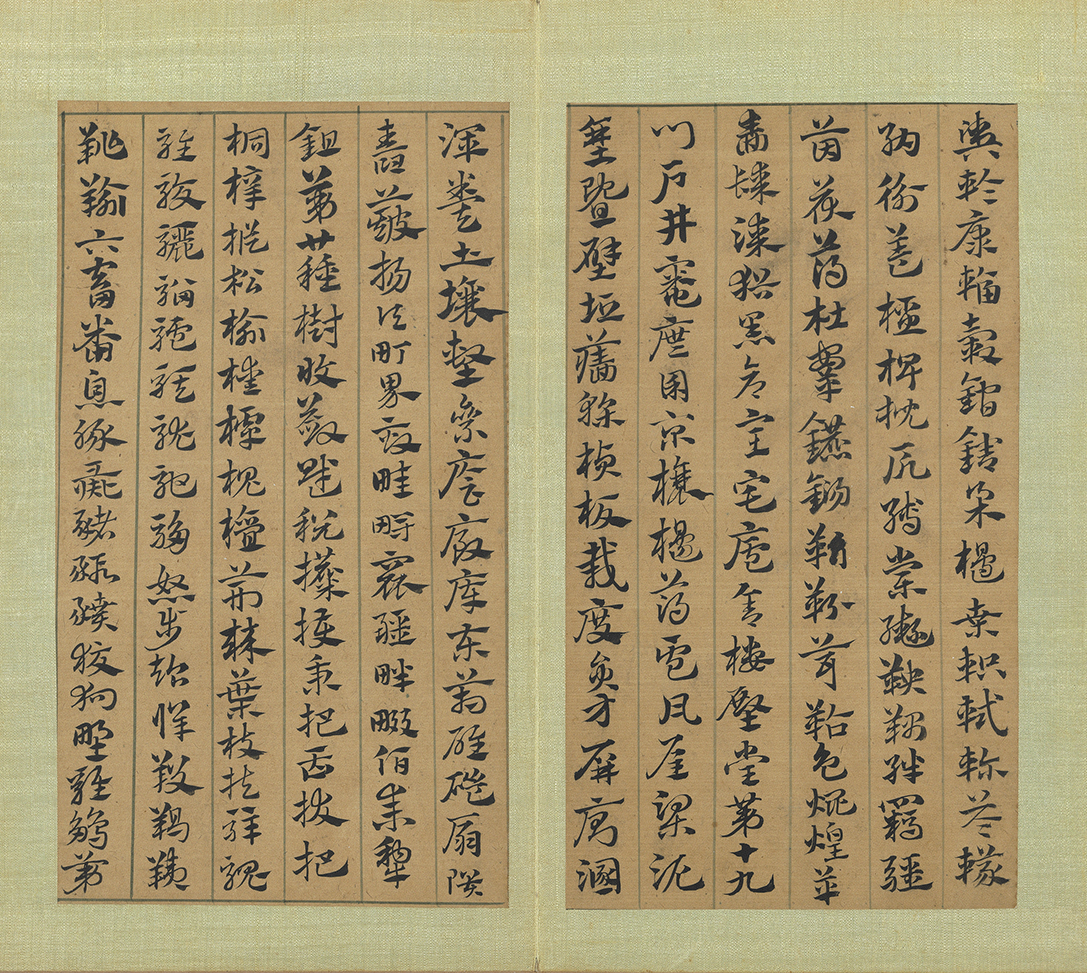

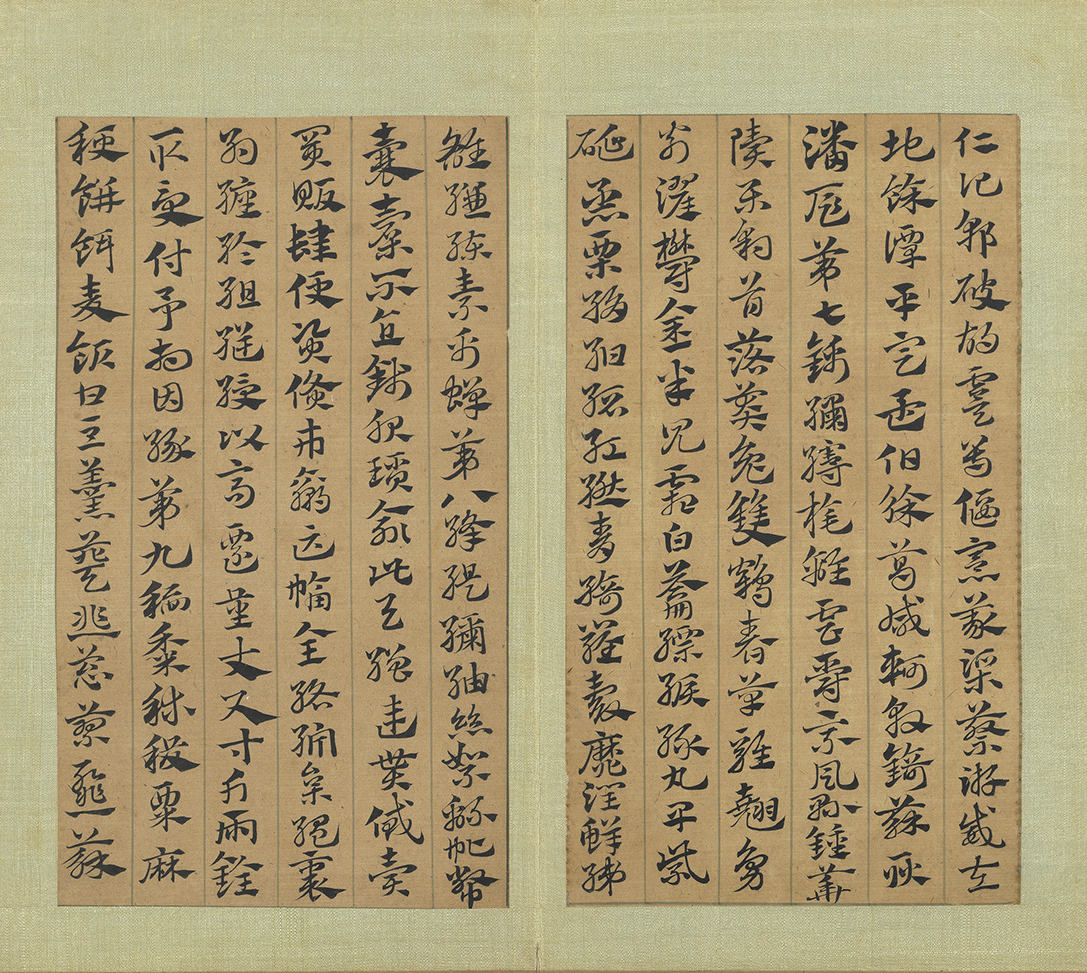

Rubbing of the Cao Quan Stele

- Anonymous, Han dynasty

The complete name of this stele is "The Stele in Geyang in Honor of Minister Cao Quan." The engraved capstone of the original is lost to time. Cao Quan was a native of Dunhuang in present day Gansu province who was known to have shown extraordinary filial devotion to his parents. While serving as a minister in Geyang in present day Shaanxi province, Cao performed numerous kind deeds, prompting his peers to extol his virtuous character. His merits and achievements were memorialized upon a stone stele during the second year of the Zhongping reign period of Emperor Ling of the Eastern Han dynasty (185 CE).

This stele was excavated during the reign of Emperor Wanli of the Ming dynasty. The characters were written with very uniform and even structures, the calligrapher possessing such fluid control over the brush's movements that the writing seems both leisurely and elegant. The writing succeeds at being refined without losing its vitality, containing rustic vigor and sophisticated beauty in equal amounts. The simultaneous presence of fluency within solidity reveals mature proficiency in calligraphic techniques, making this stele one of the representative works of Han dynasty official script (lishu). -

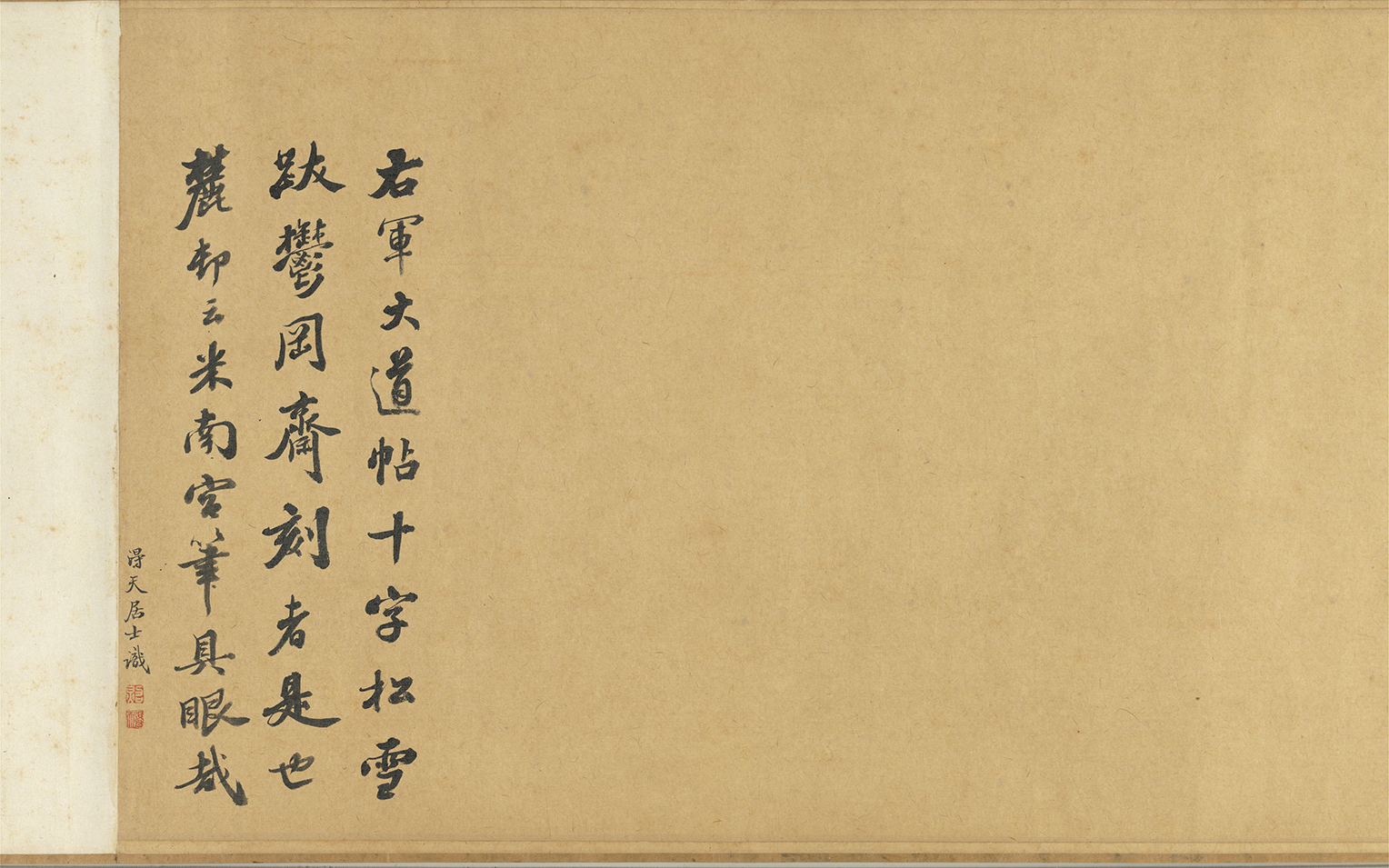

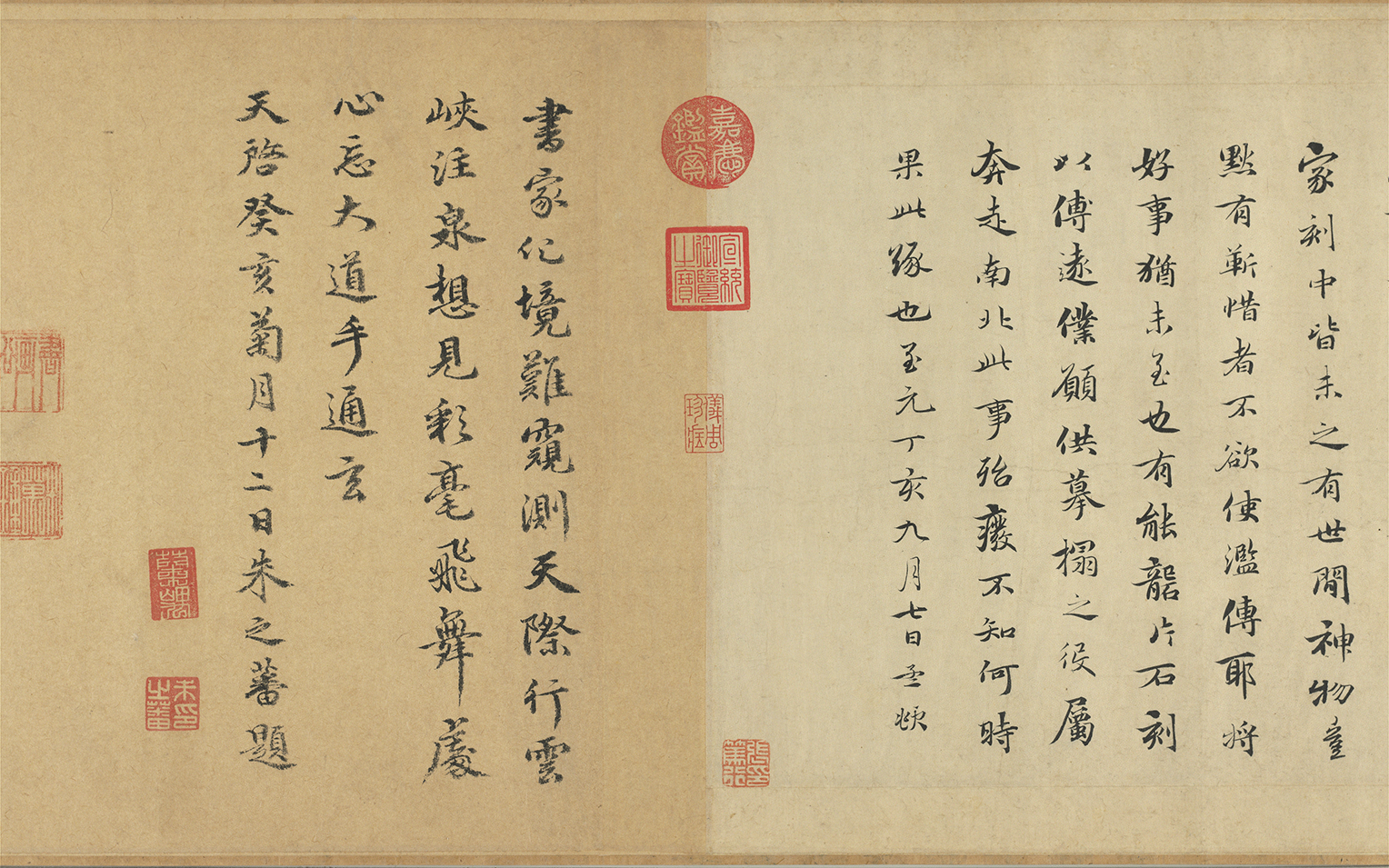

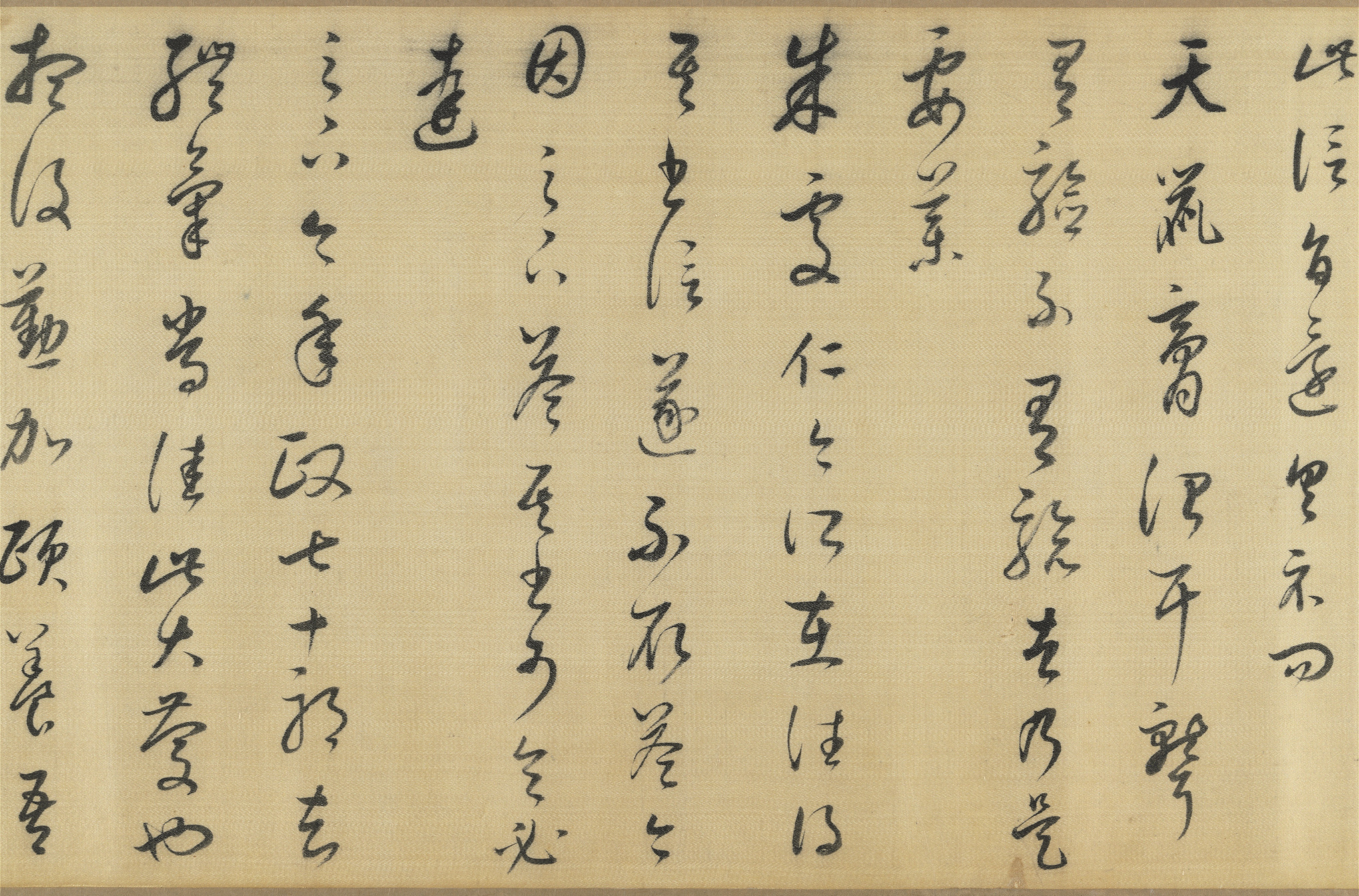

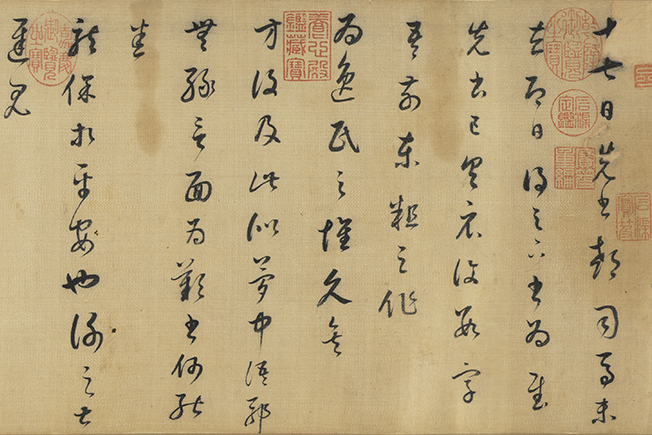

The Great Dao Inscription

- Attributed to Wang Xizhi (303-361), Jin dynasty

This inscription comprises two lines written in cursive script (also called "grass script," from caoshu). The first reads, "The Great Way has not descended for some time, how were things not this way before?" Additional paper later attached to the scroll contains a calligraphic colophon written by Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) in the Dinghai year of the Yuan dynasty (1287), which compares Wang's brushwork to a "dragon leaping through Heavens' Gate or a tiger lying at Phoenix Pavilion."

The brushstrokes in Wang's inscription are ample and rounded. In the first line, all of the characters—from the first one, "great," to the last one, "descended"—were written in a single flourish. The final brushstroke in the ultimate character, an exclamation pronounced "ye," was incredibly drawn-out, and then thickened at its tail end before turning in an arc. Because there are no other extant works by Wang Xizhi in this style, most theorists posit that it is likely a study of Wang's work by Mi Fei (1052-1108). -

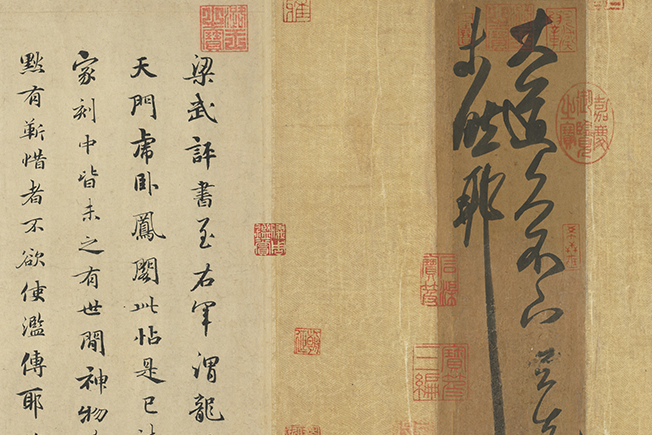

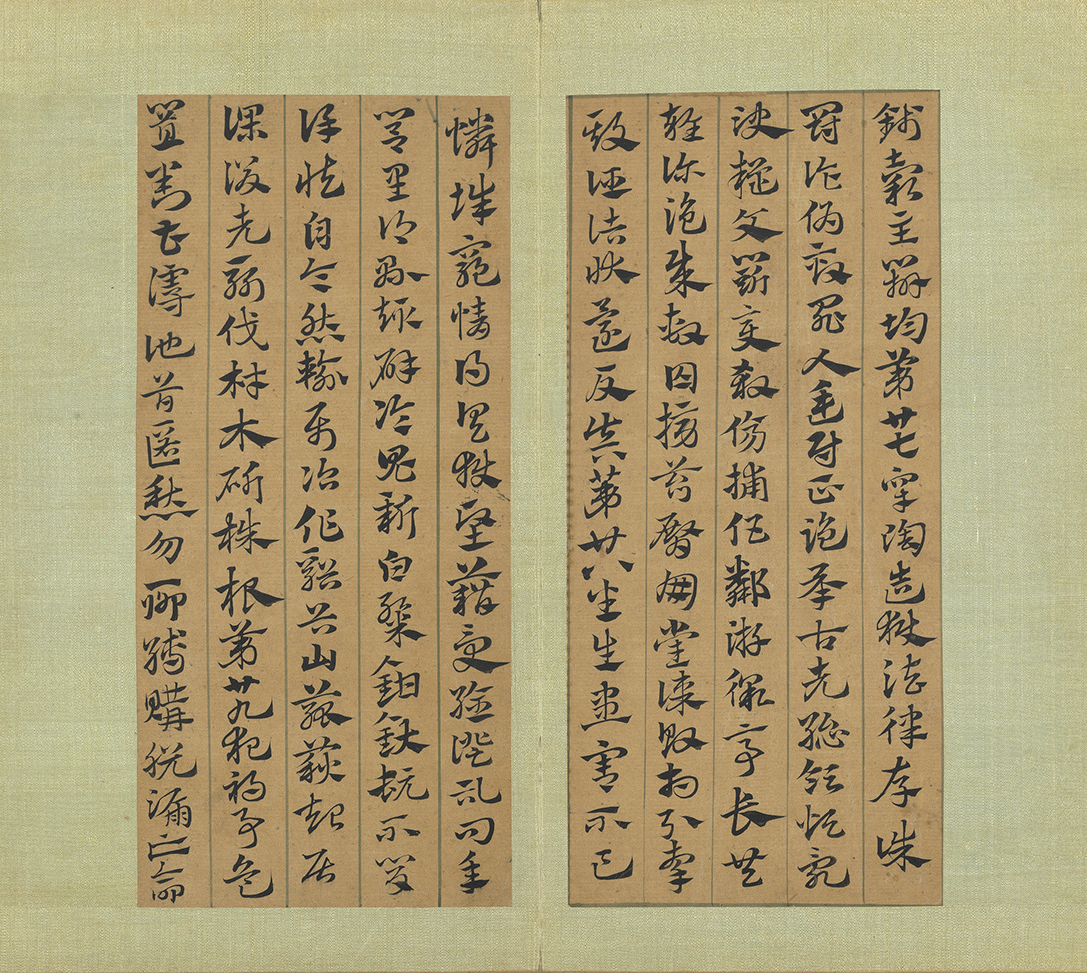

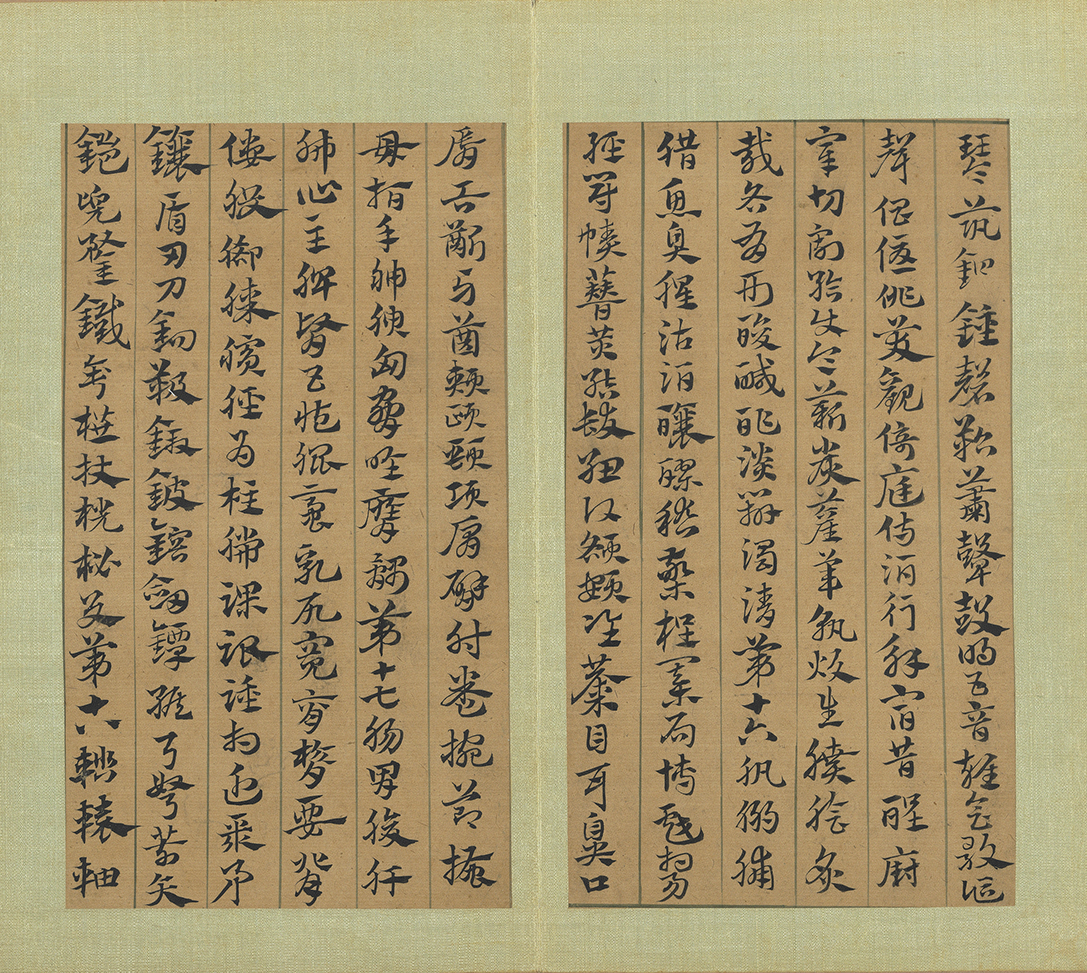

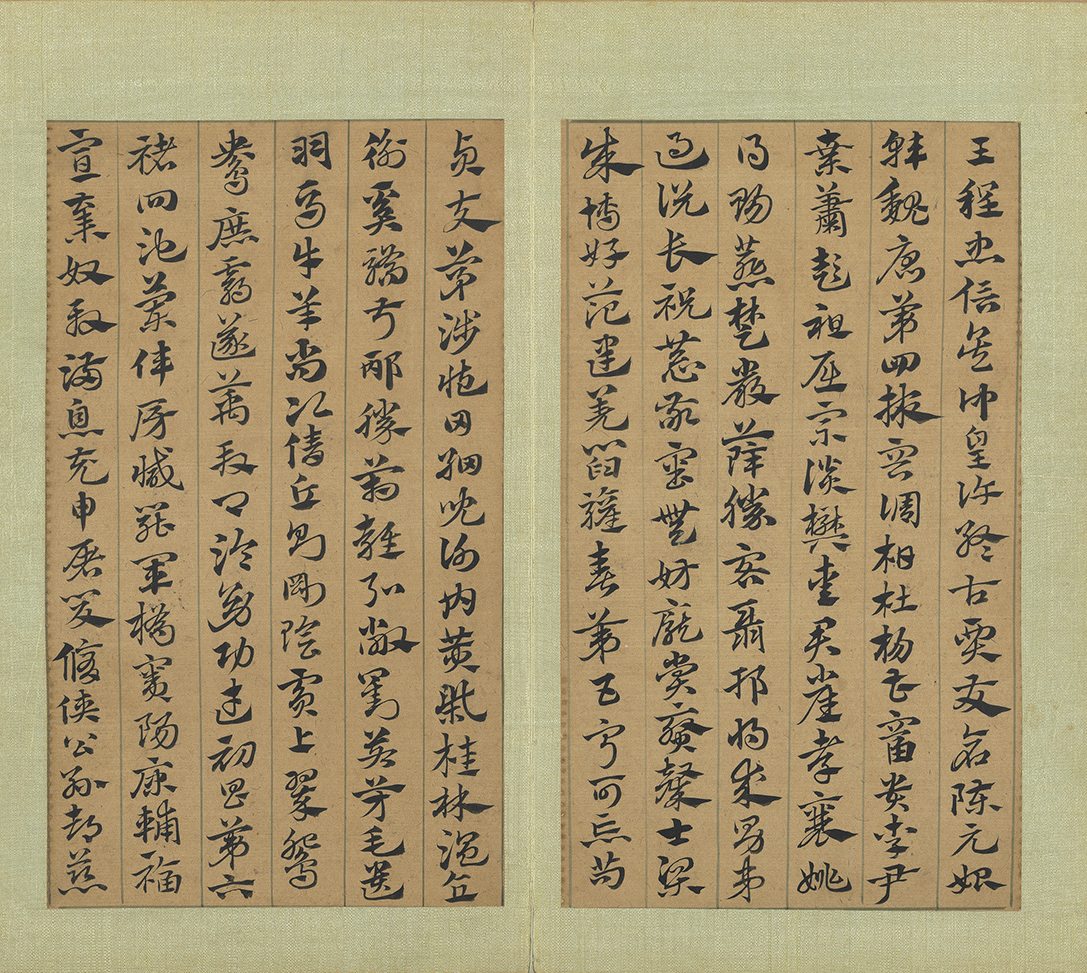

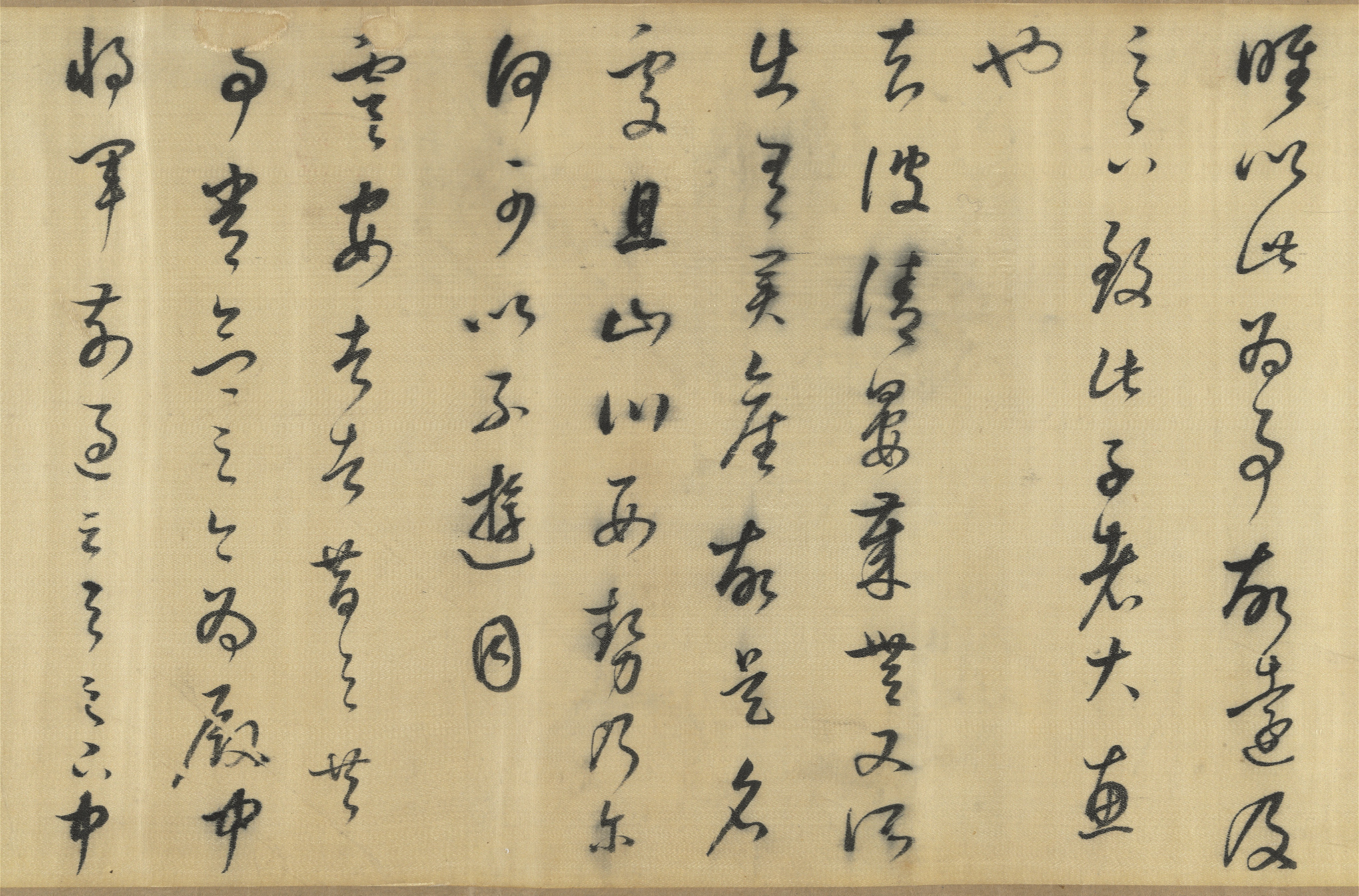

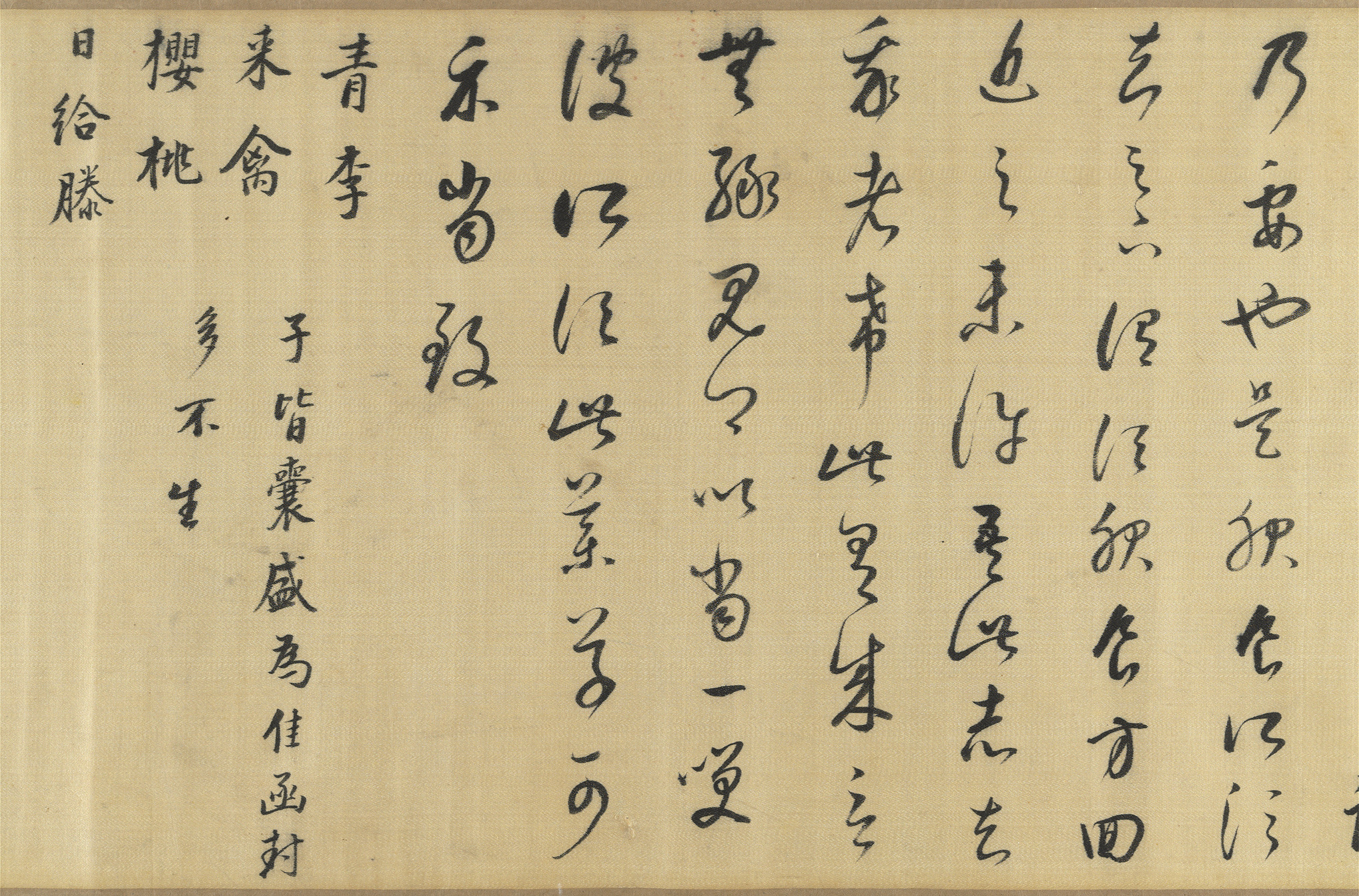

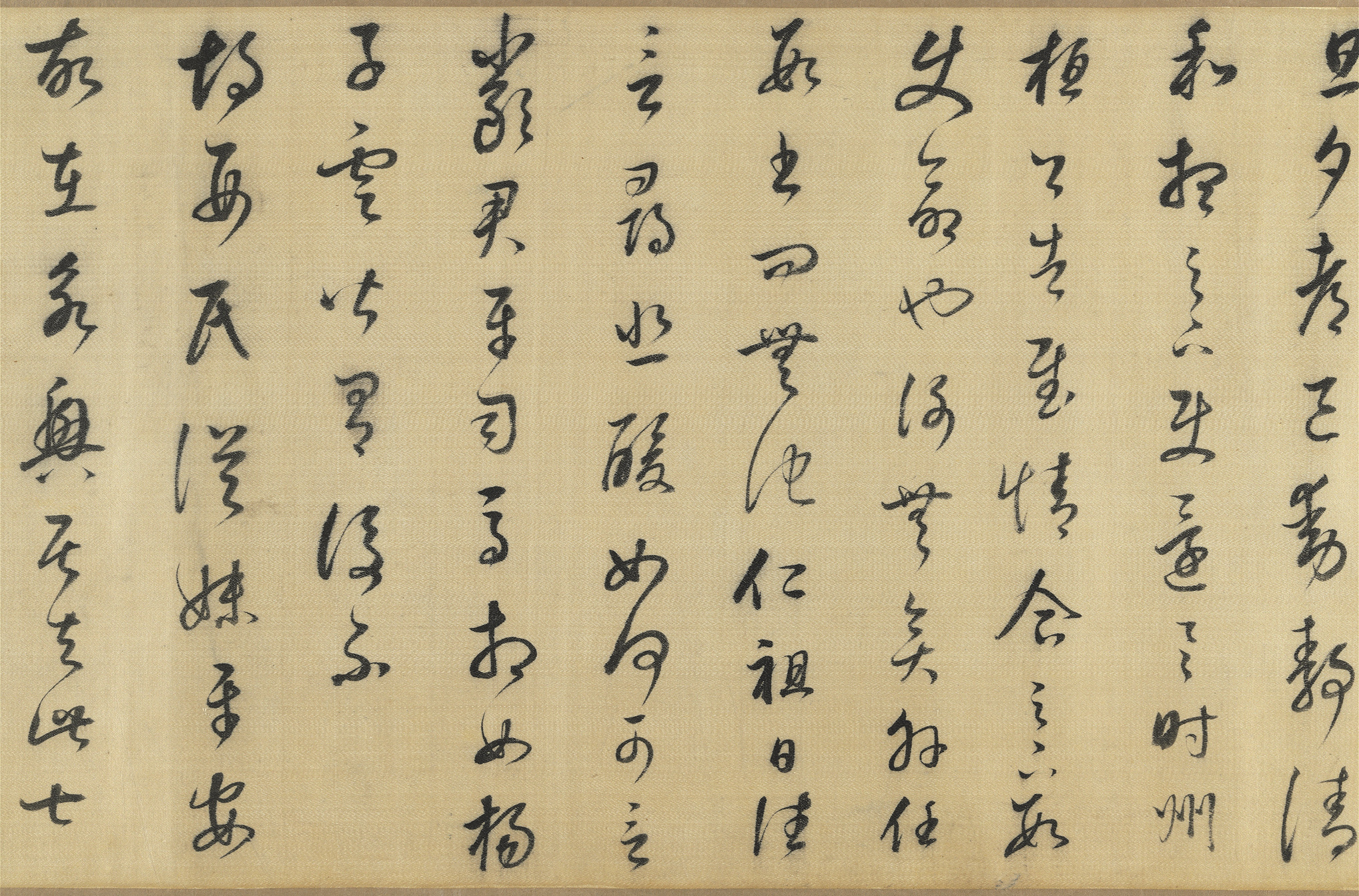

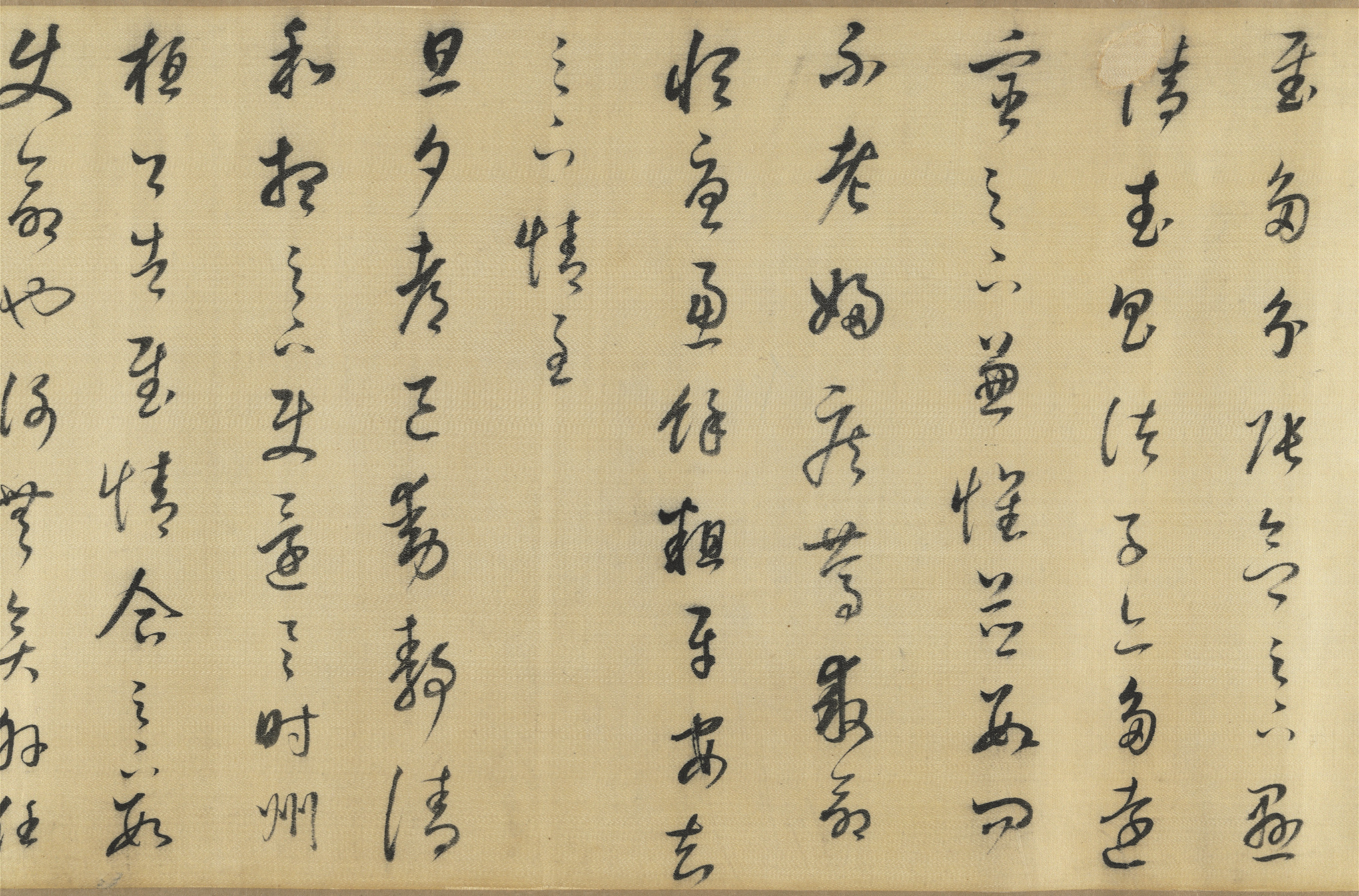

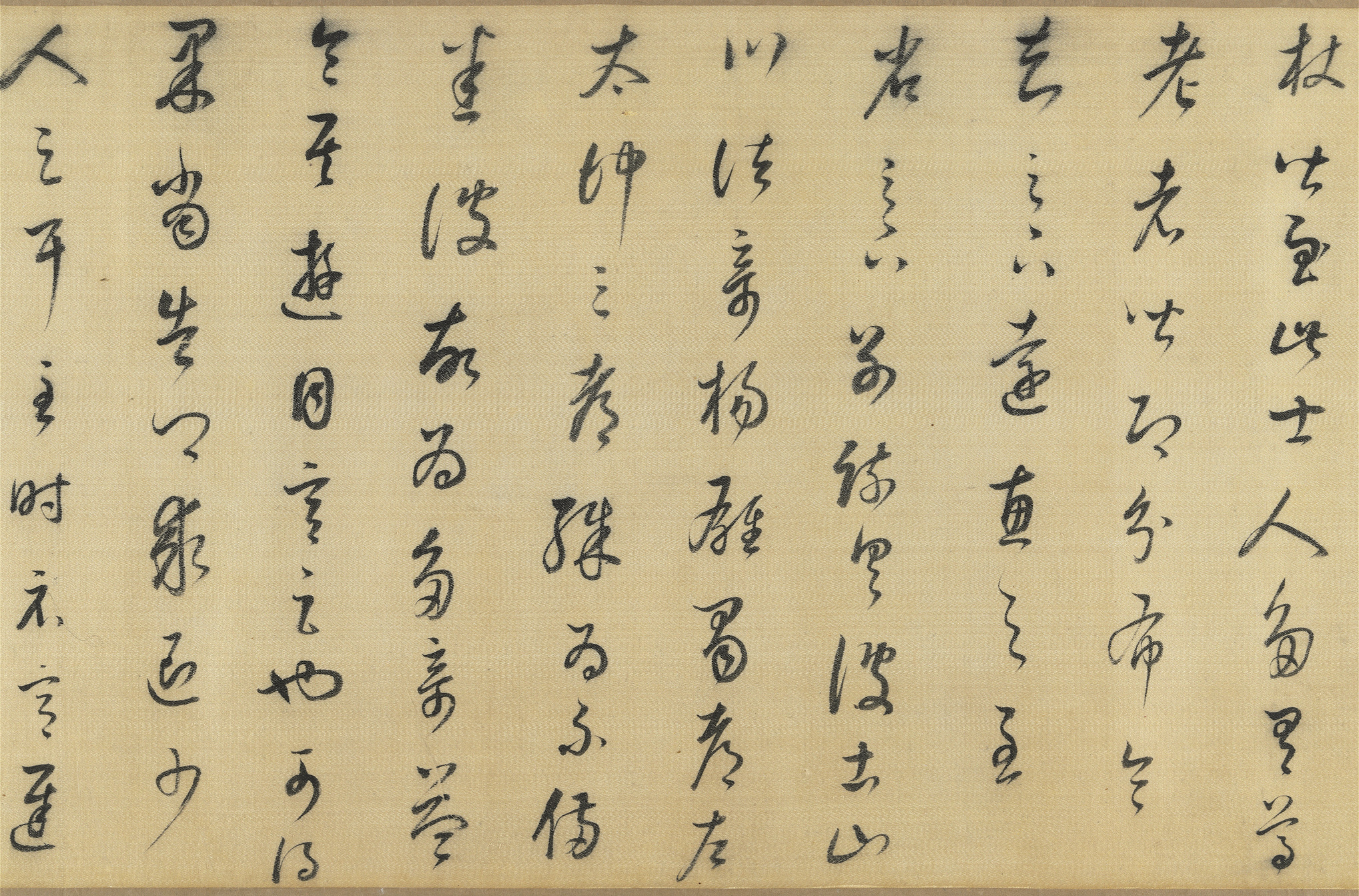

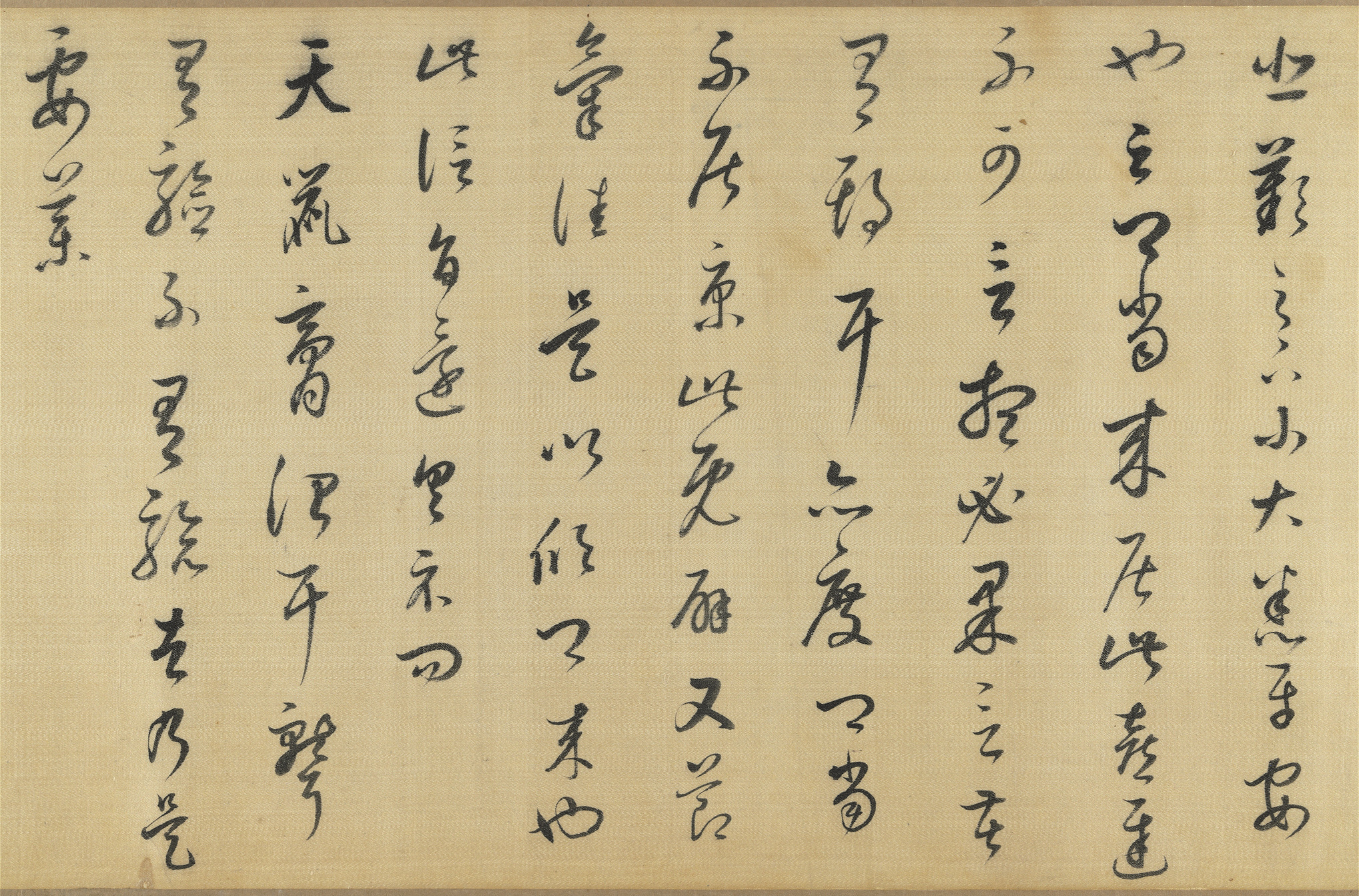

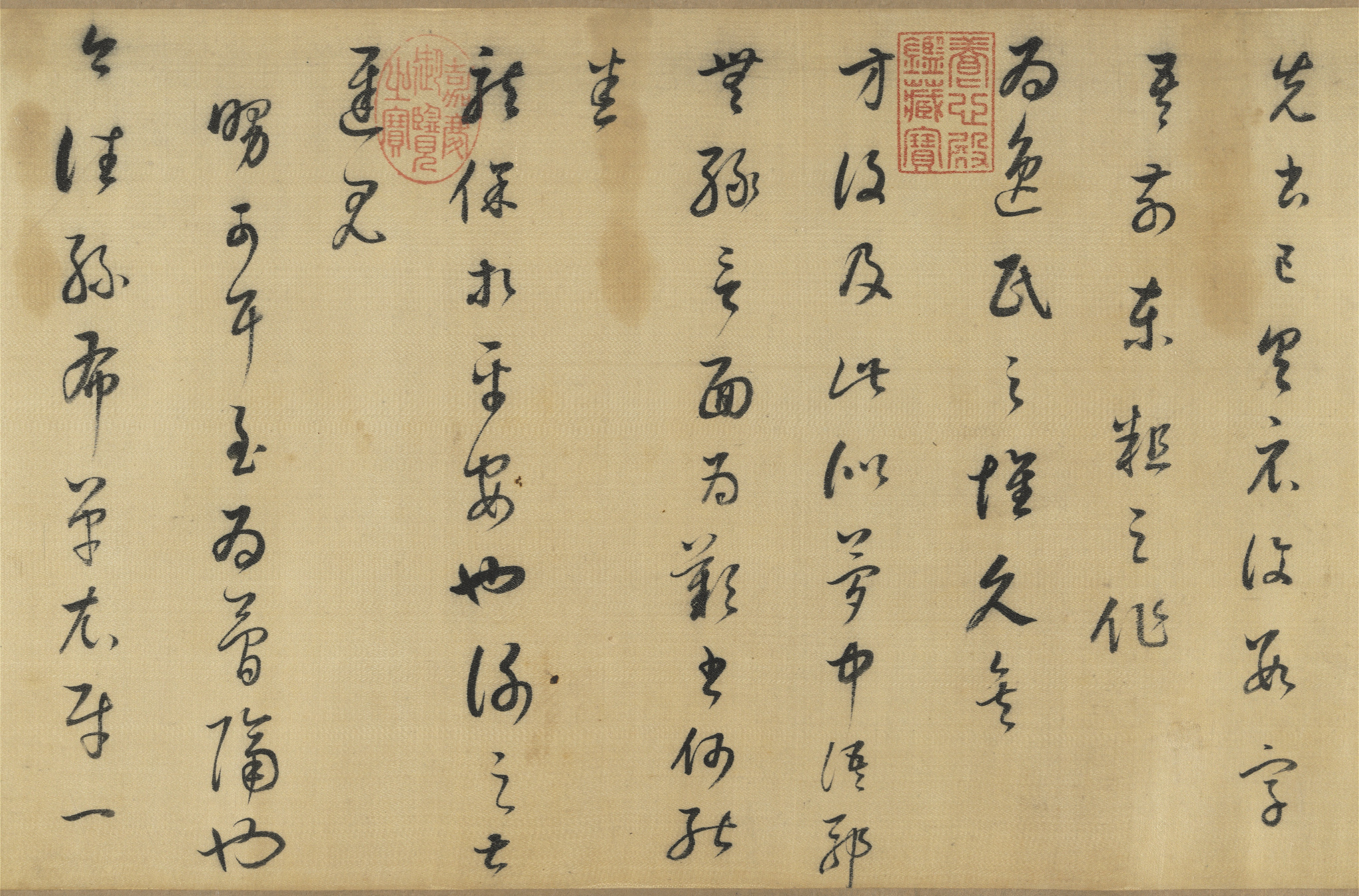

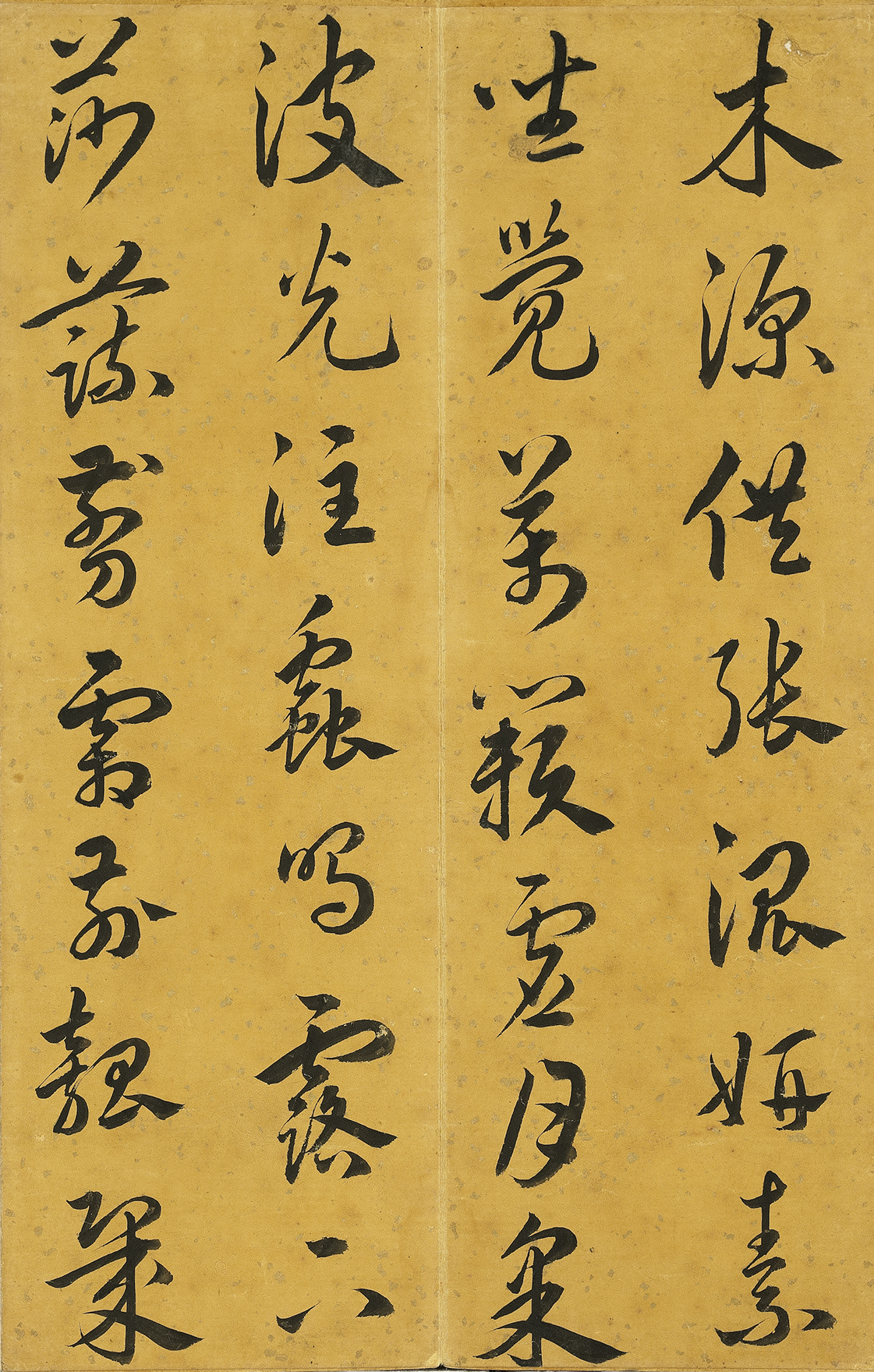

A Tract in Draft Cursive

- Attributed to Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322), Yuan dynasty

This inscription was previously called "A Tract in Draft Cursive Written by Zhao Mengfu of the Yuan Dynasty," but a number of researchers hold that it is likely a work by Yu He (1307-1382), written in his later years. A close reading of the colophon on the reverse side of this leaf reveals that it was probably a study of Zhao's calligraphy by Yu.

Yu He, who was also known by the style name Zizhong and the sobriquet "He of the Purple Glossy Ganoderma" (Zizhisheng), was a resident of Hangzhou. According to popular accounts, he received tutelage from Zhao Mengfu in his youth, and as a result his calligraphy became so similar to Zhao's that they were indistinguishable. This piece was written in the style of draft cursive script (zhangcao) from the Han and Jin dynasties. The characters appear in a state of transition from ancient simplicity towards enchanting elegance, with marked angulation of the brush's movements employed in the writing of the long horizontal and right-falling strokes, combined with abrupt stops in the shorter horizontal strokes. Yu used the technique of creating angled corners in some of the freestanding dots in this work, while also lifting his hand so as to reveal traces of the brush's tip when writing short horizontal strokes. As a result, his brushwork appears transformative and agile. -

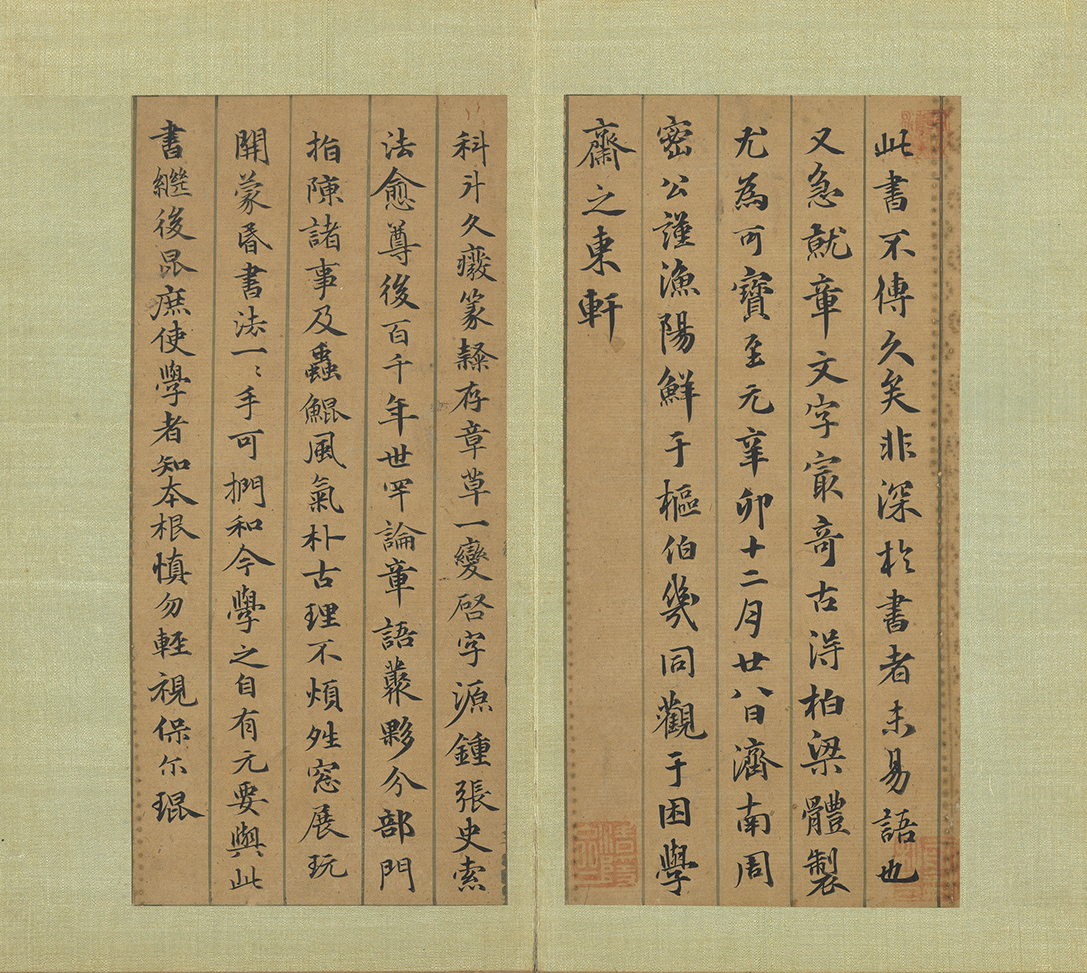

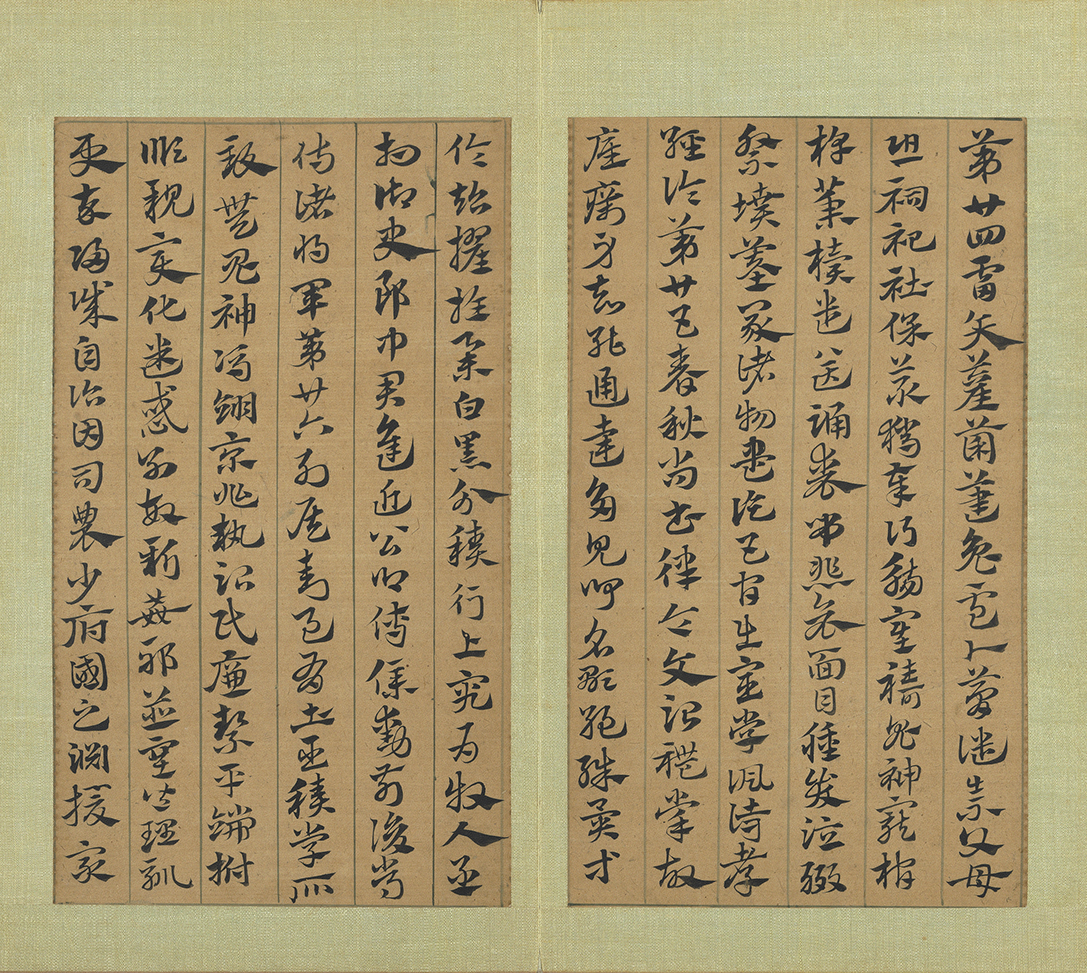

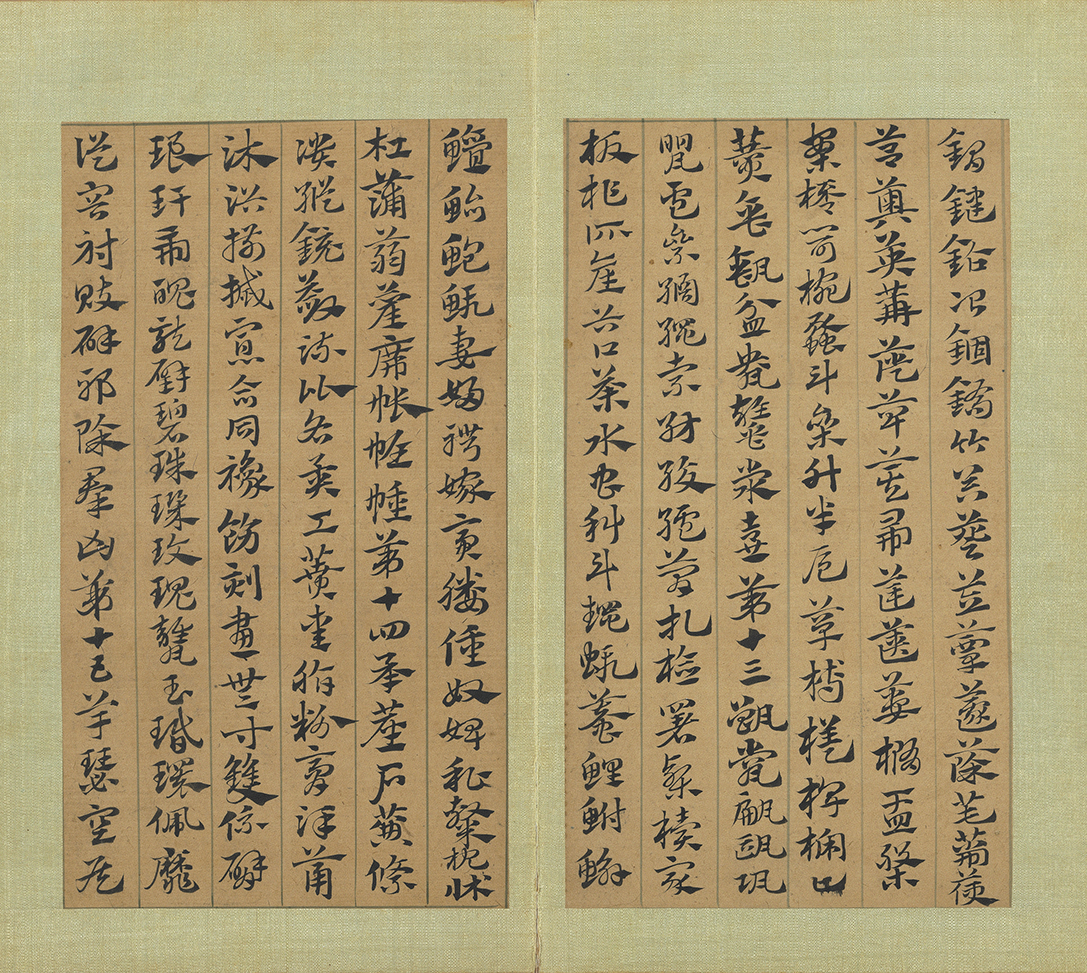

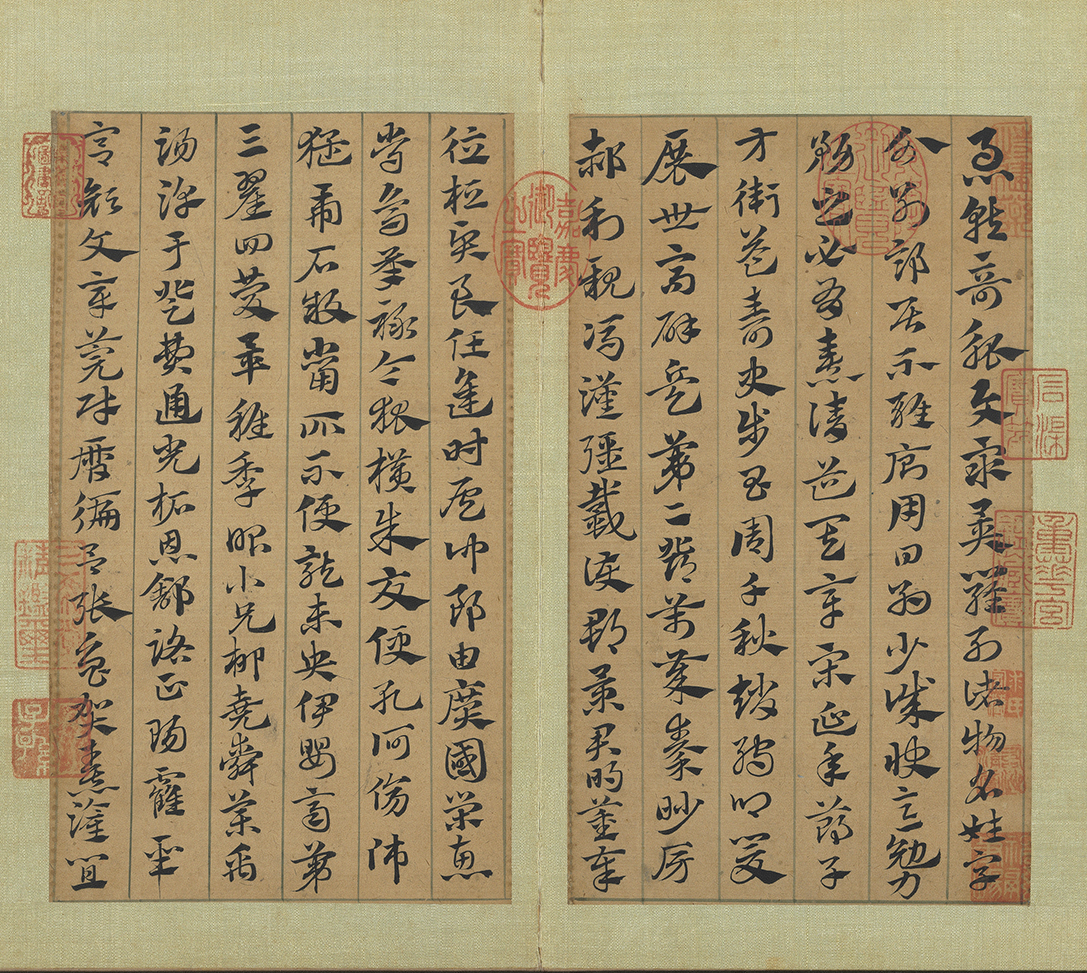

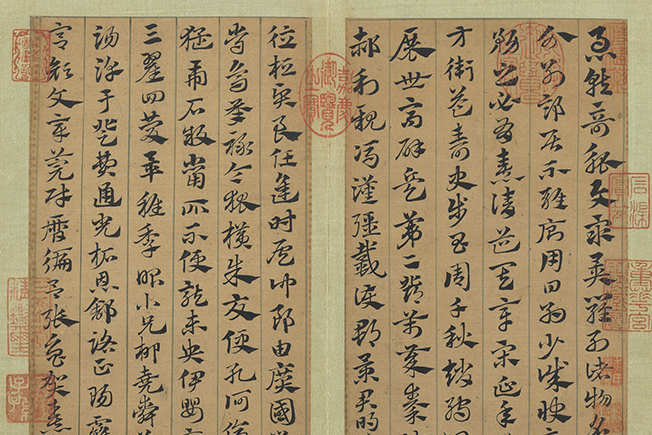

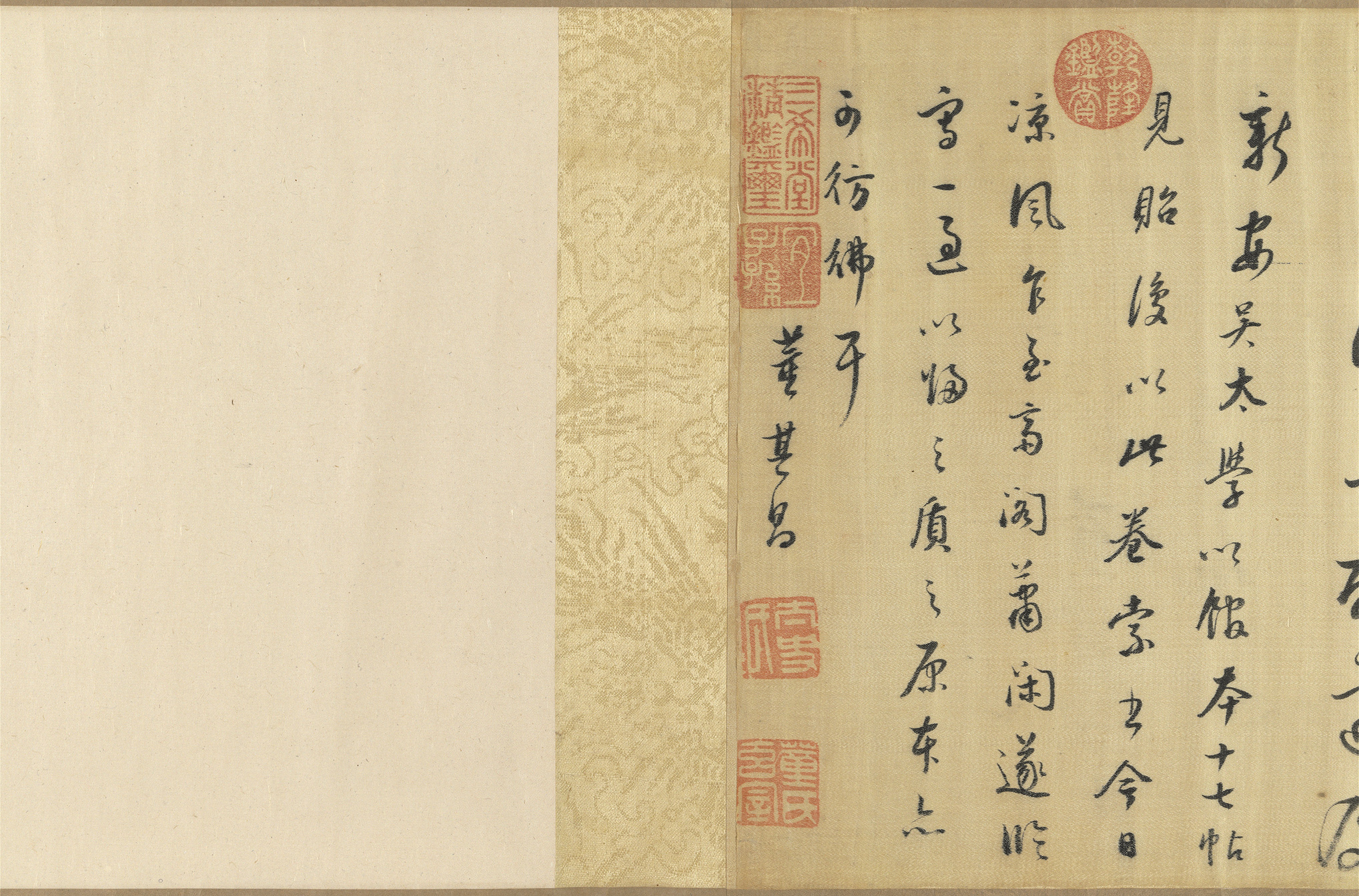

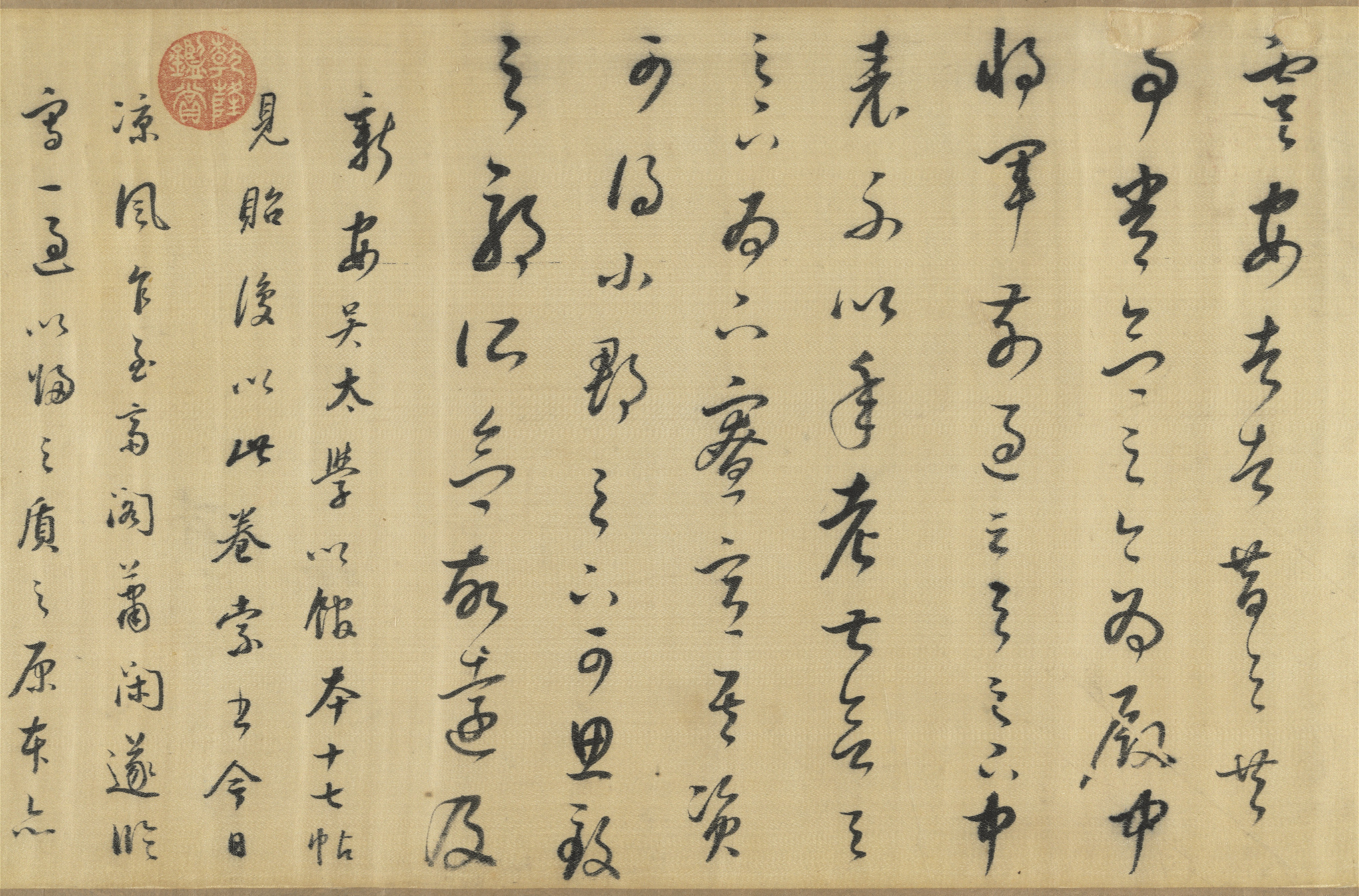

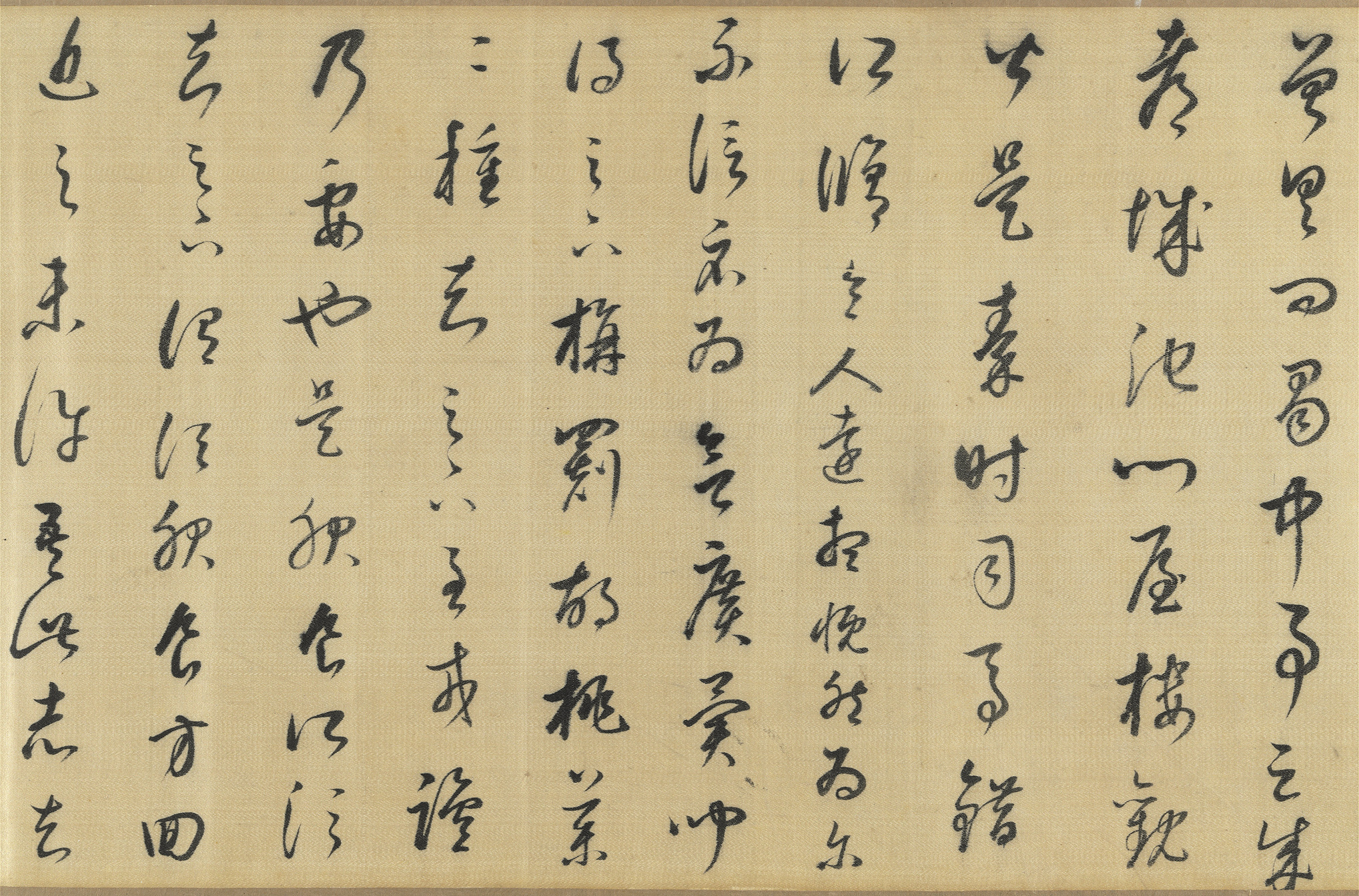

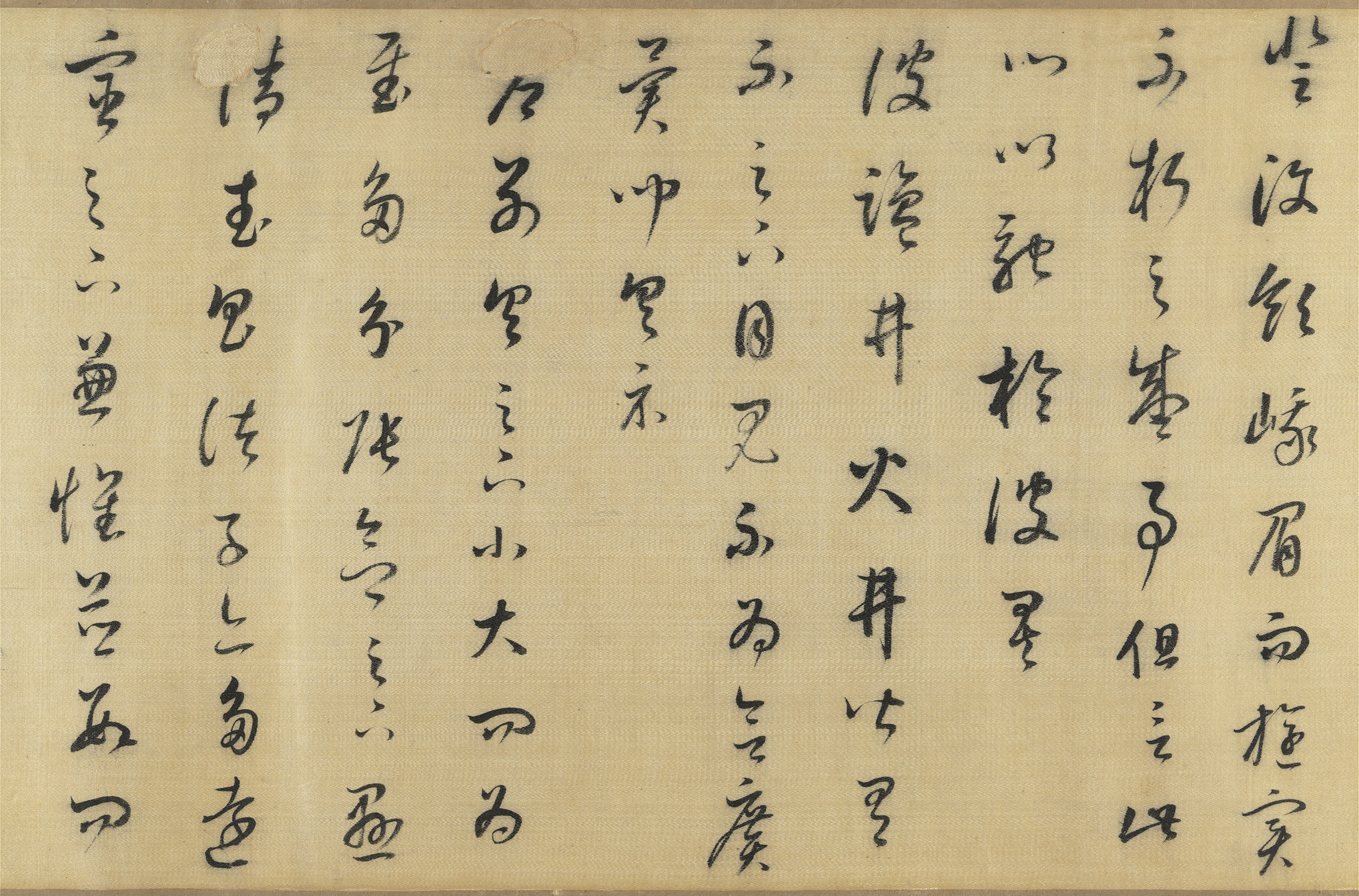

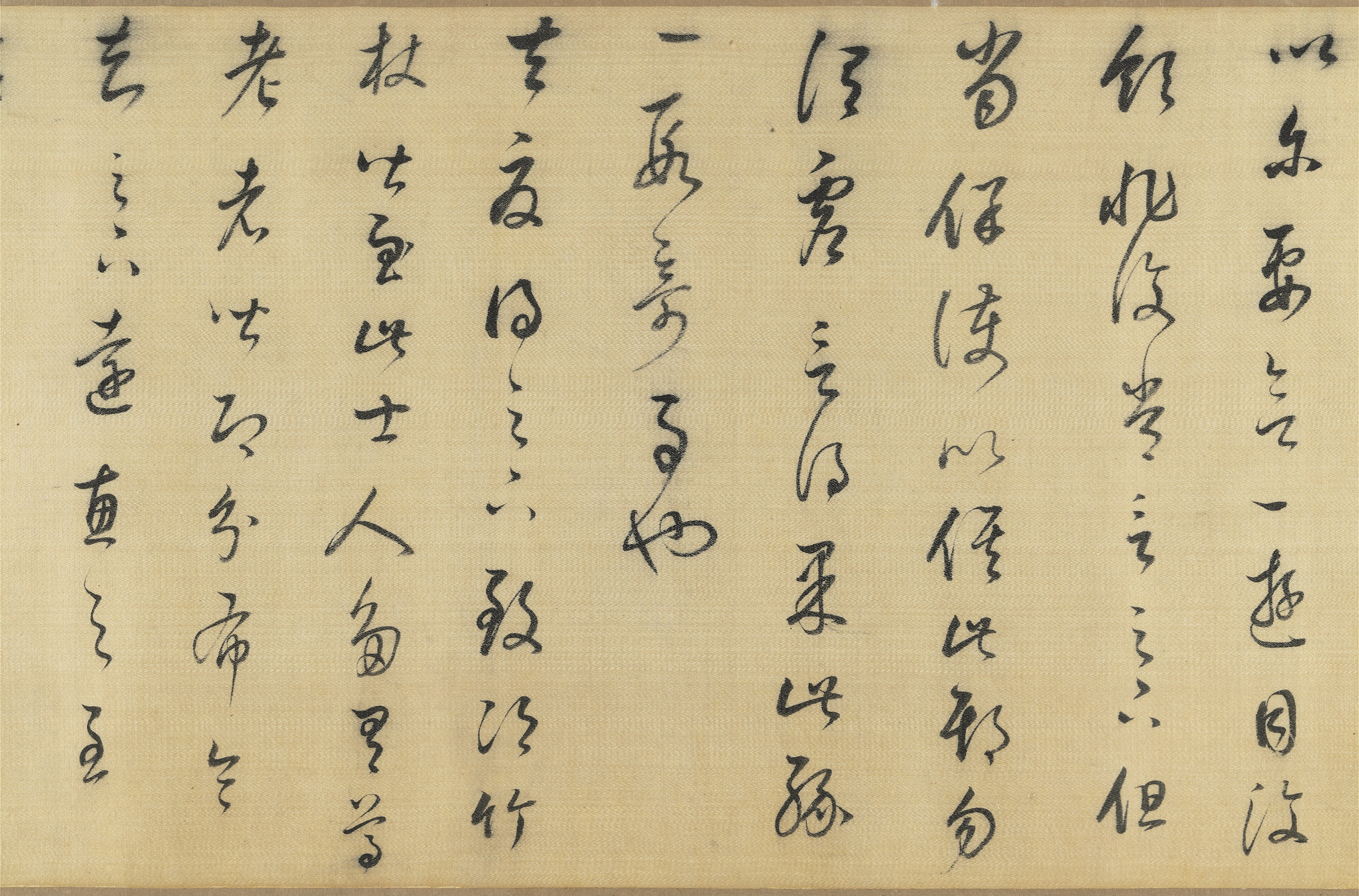

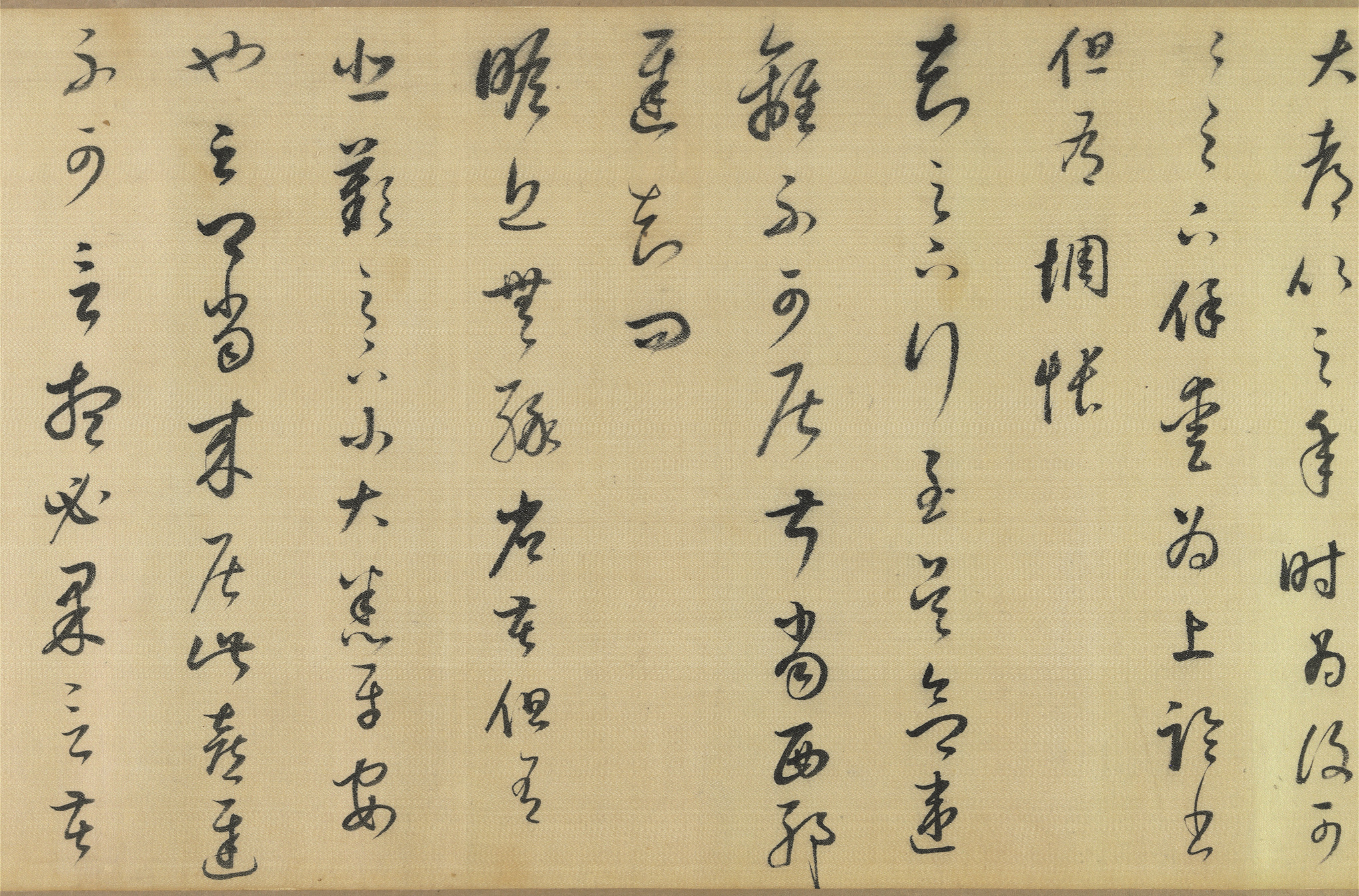

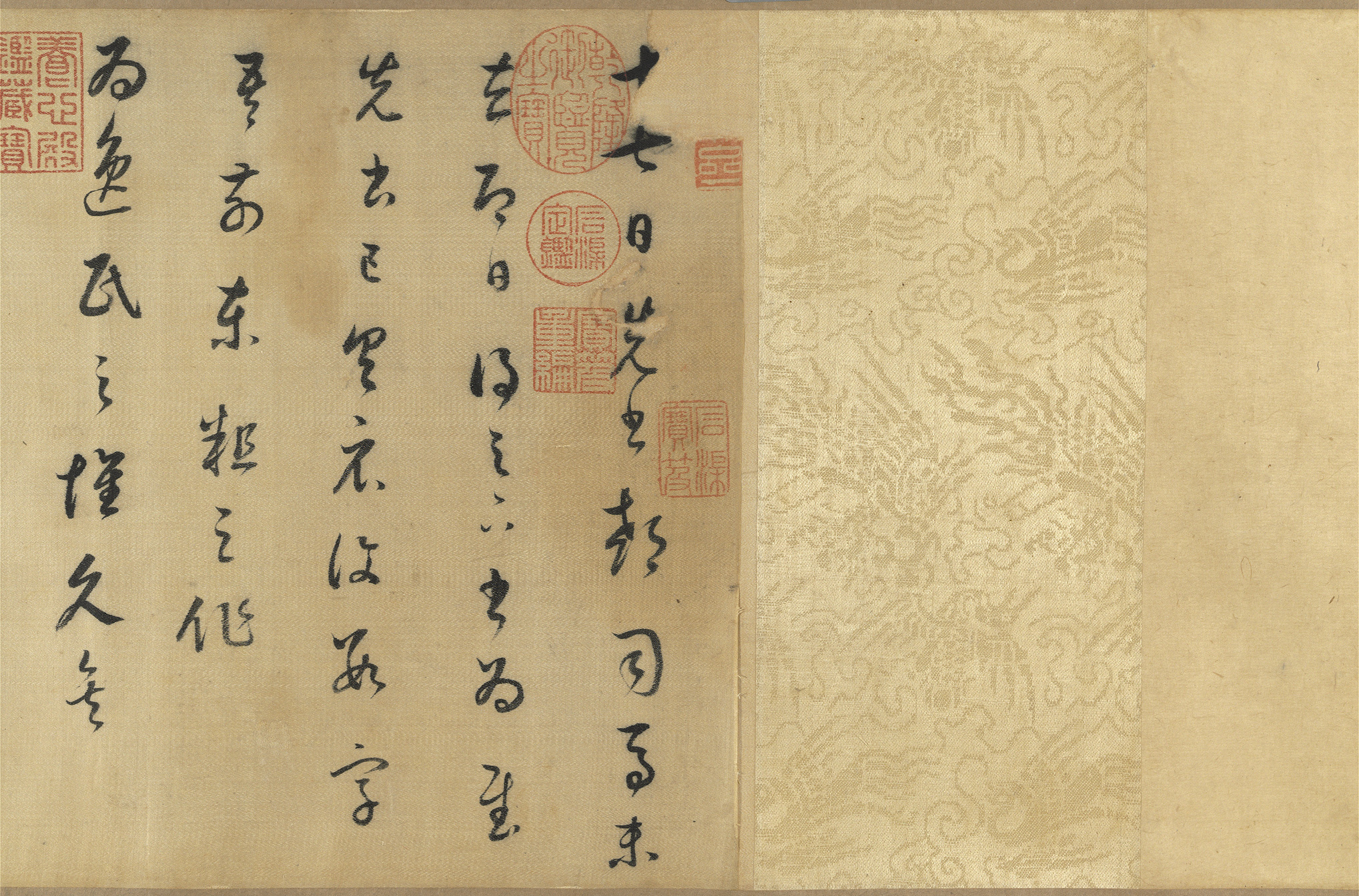

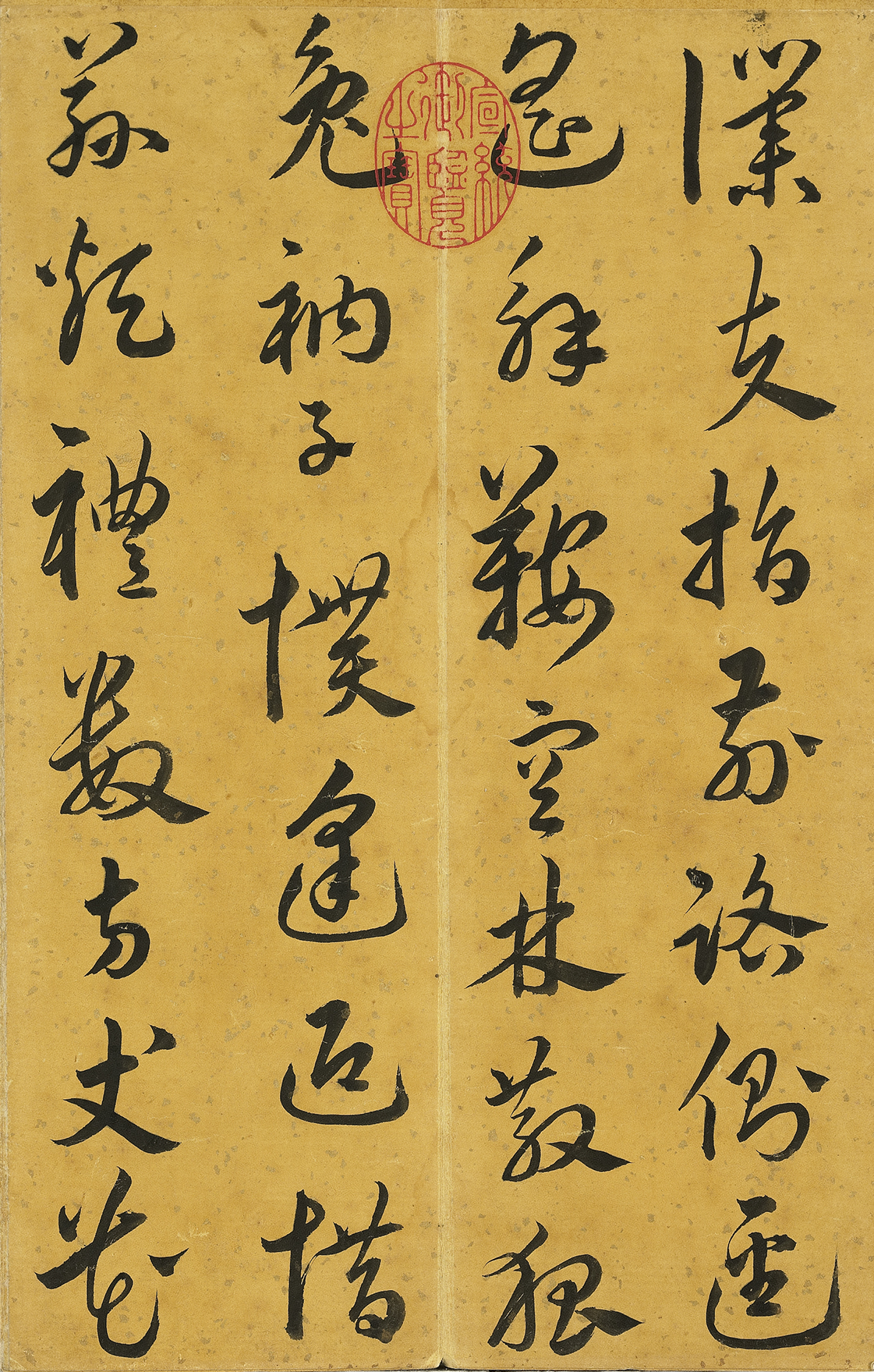

After "The Seventeen Inscription"

- Dong Qichang (1555-1636), Ming dynasty

Dong Qichang (1555-1636), whose style name was Xuanzai and whose sobriquet meant "Contemplating Emptiness" (Sibai), was a native of Huating in Jiangsu province. In the seventeenth year of Ming emperor Wanli's reign (1589), he passed the imperial examinations and obtained the rank of presented scholar (jinshi), after which he received an official appointment to the Ministry of Rites. Dong was a talented calligrapher and painter as well as an art collector with refined skills of connoisseurship and appraisal. He was later given the posthumous title Wenmin.

This piece is undated, but researchers hold that it is almost certainly a study of the version of "The Seventeen Inscription" included in an anthology entitled Yuqing Studio Calligraphic Models. This observation places this piece after the twenty-fourth year of Emperor Wanli's reign (1596). The piece on display gives us a glimpse of the "The Seventeen Inscription's" popularity of during the late Ming epoch, while also providing evidence of the equal weight Dong Qichang placed upon making studies of ancient masterworks and performing textual research in his calligraphic practice. -

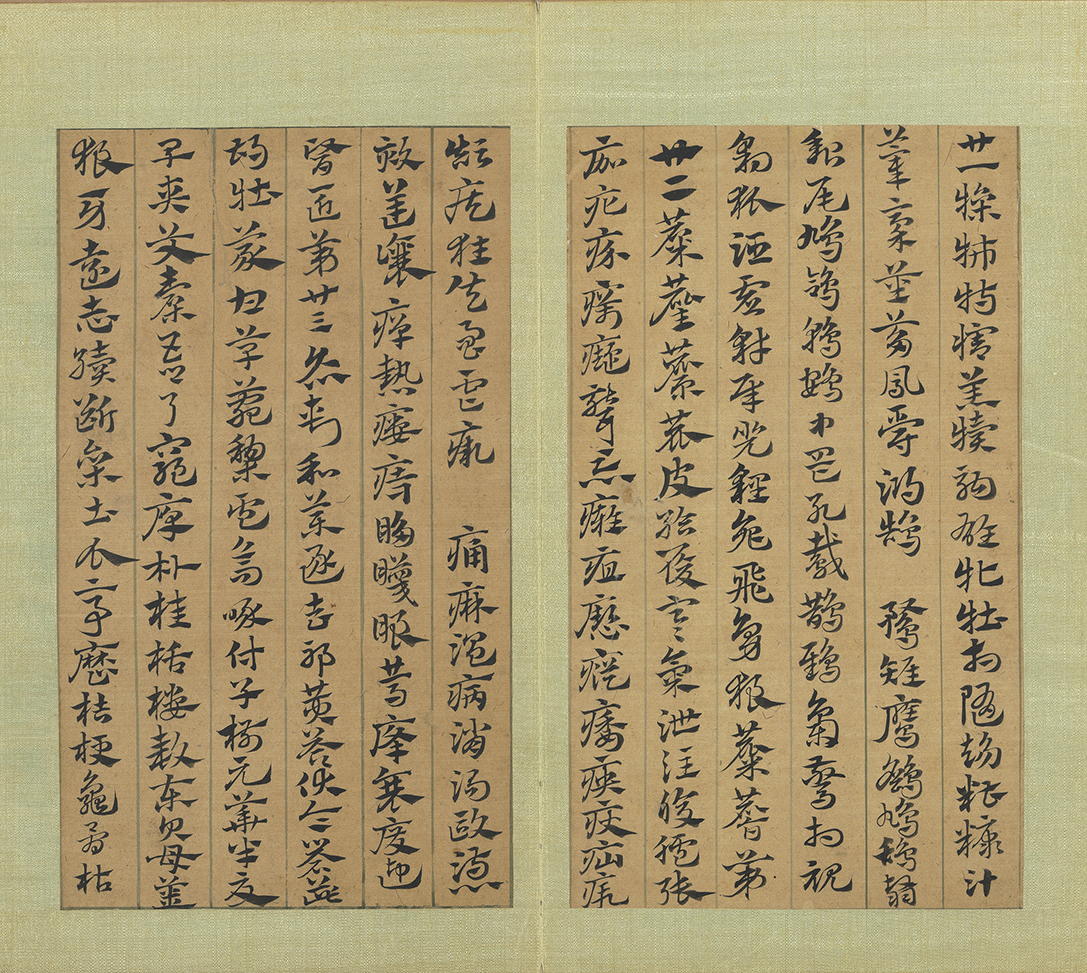

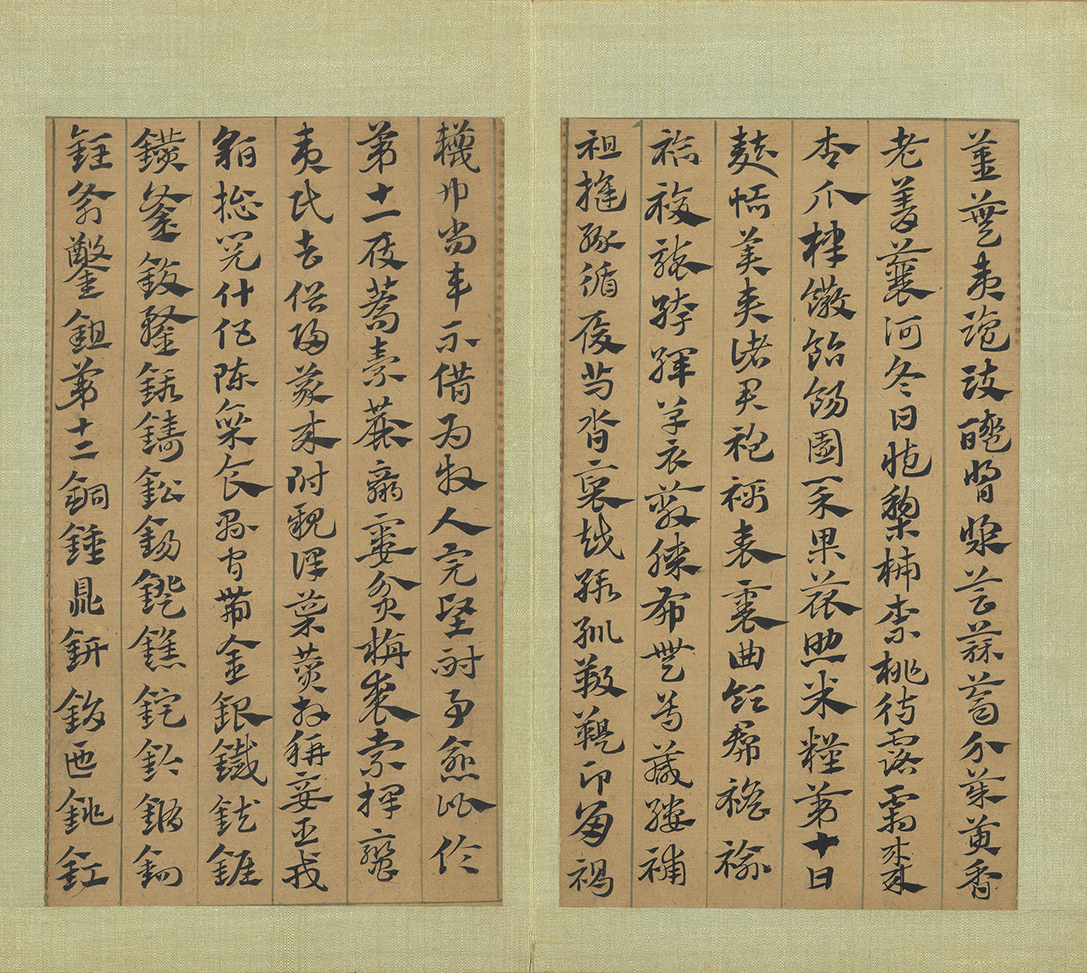

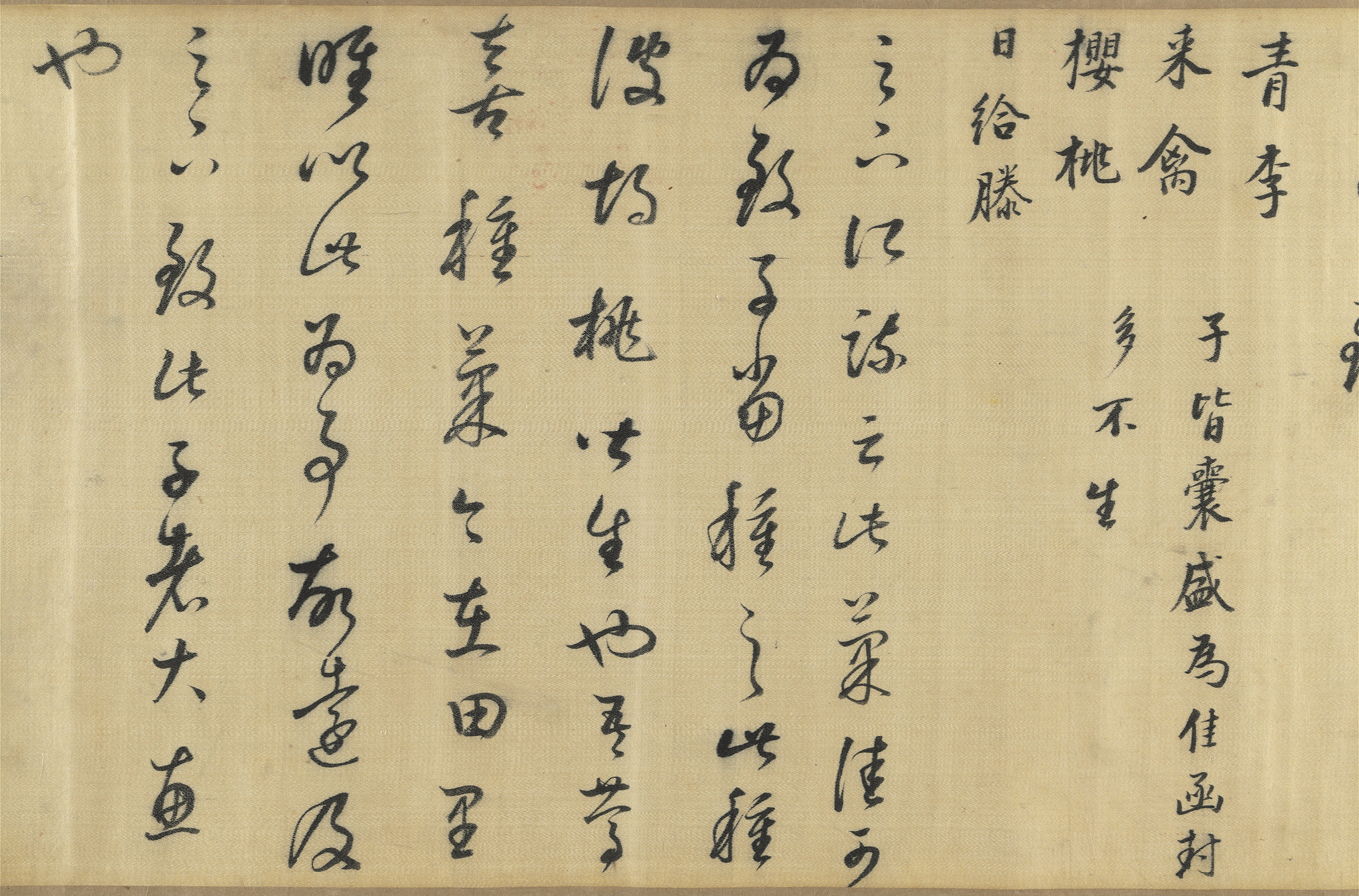

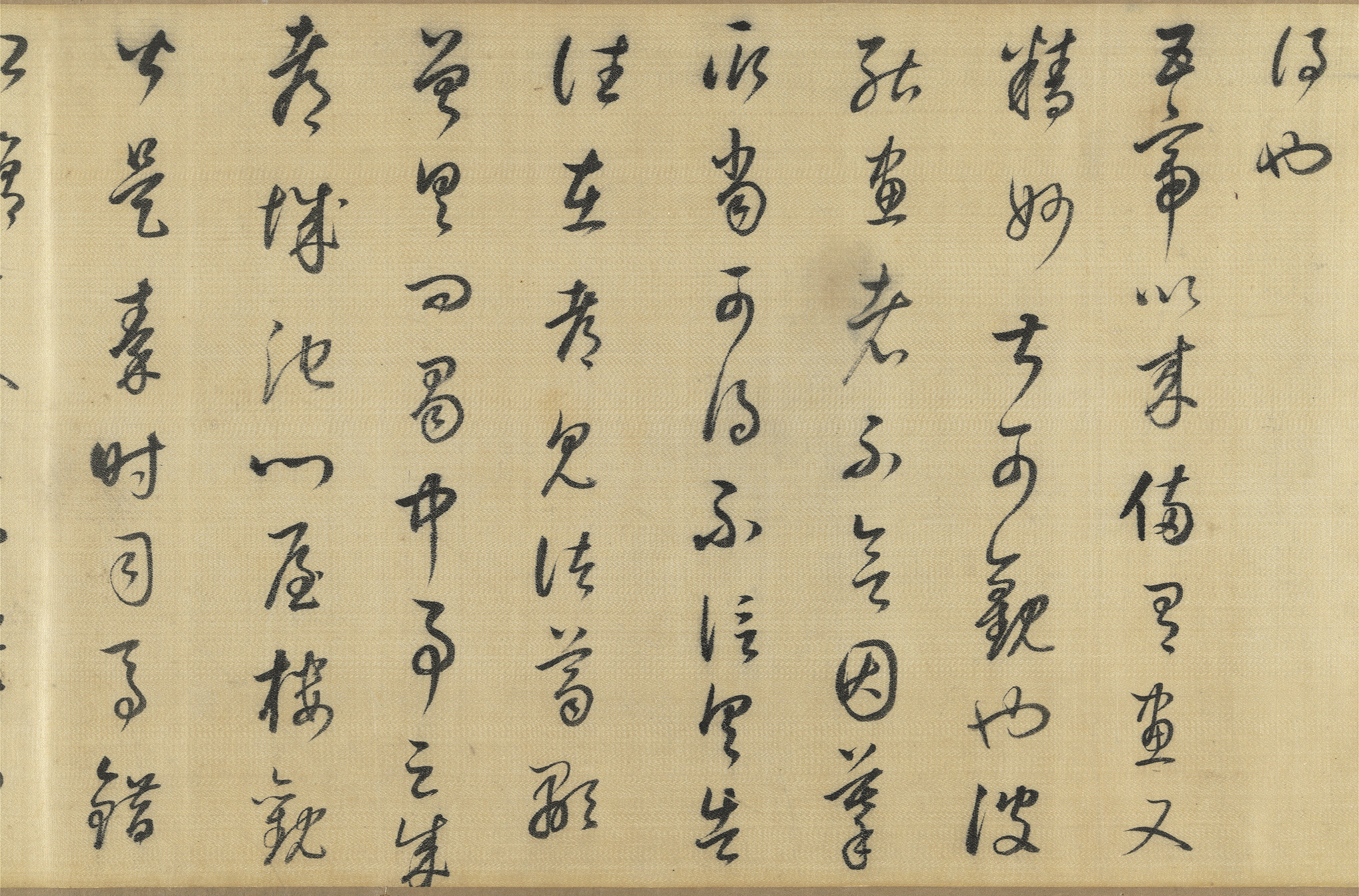

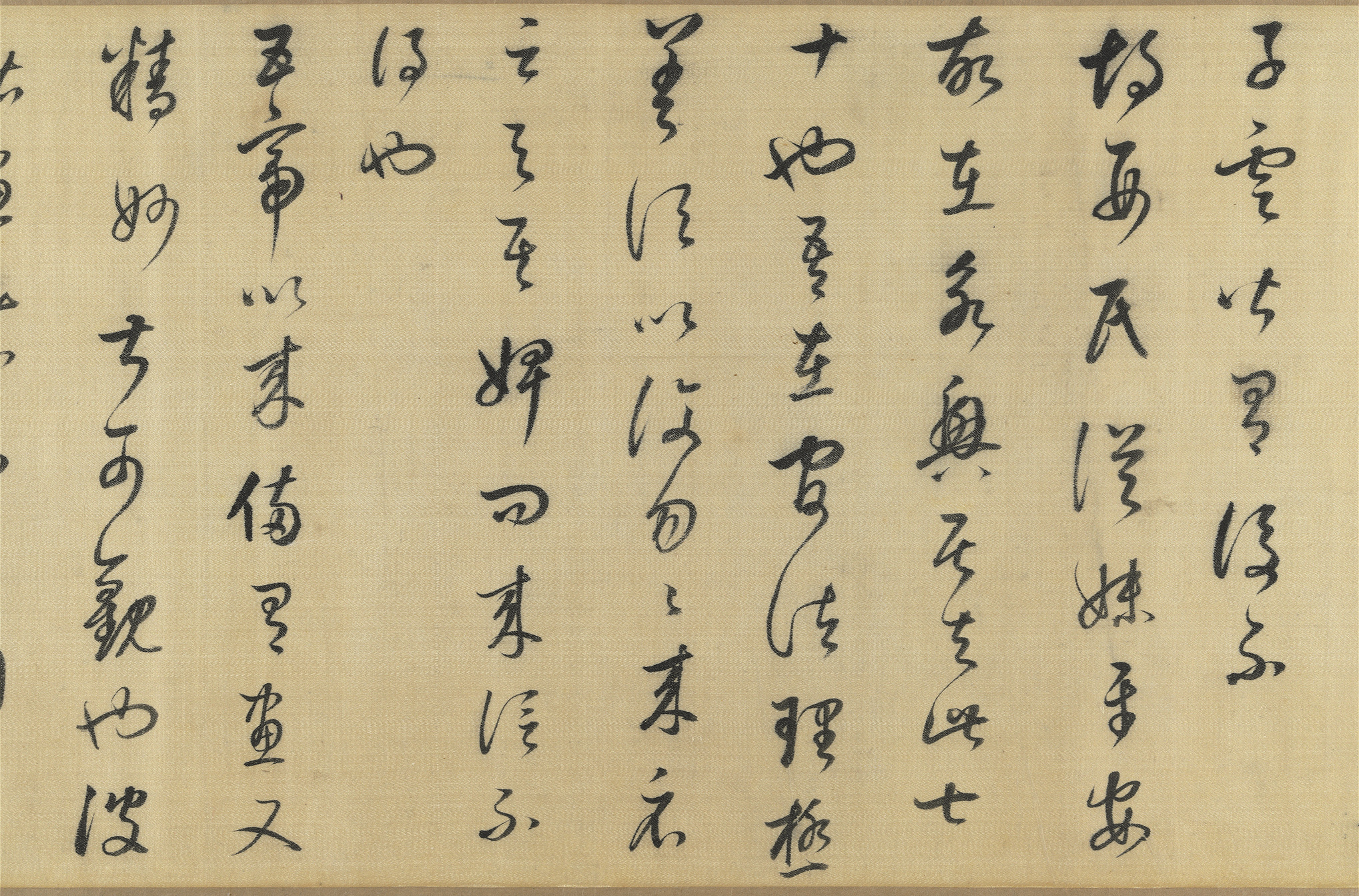

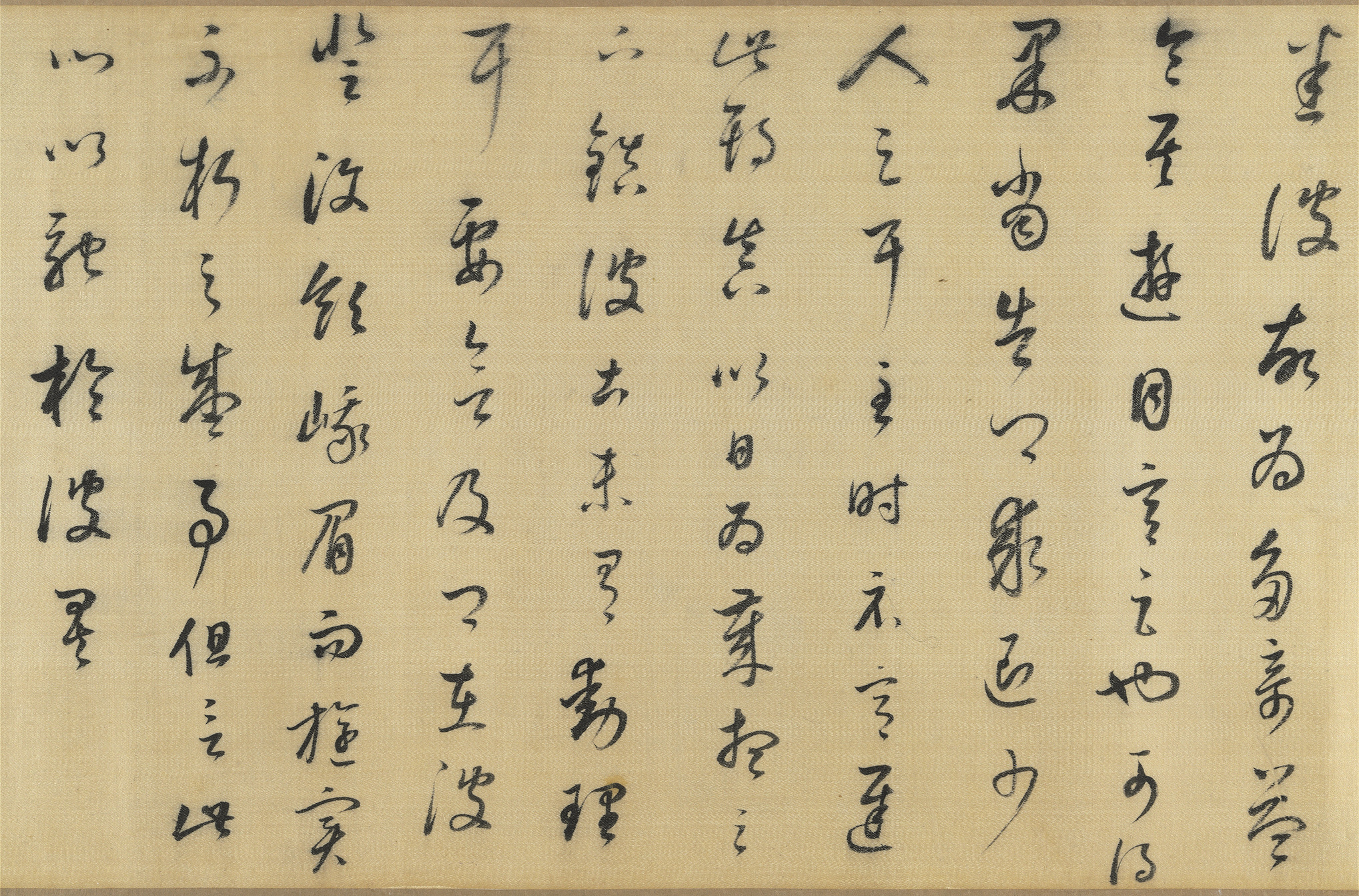

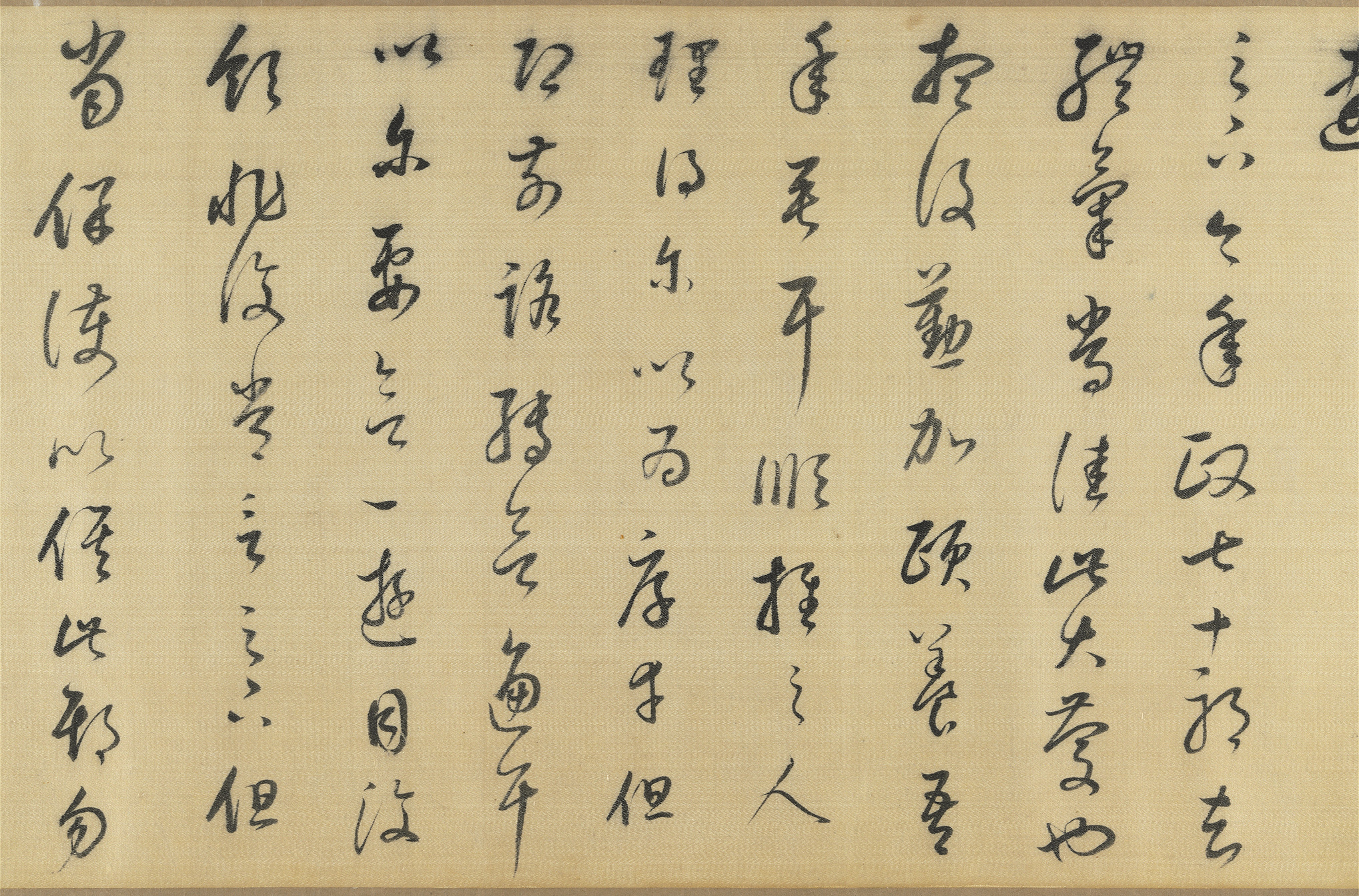

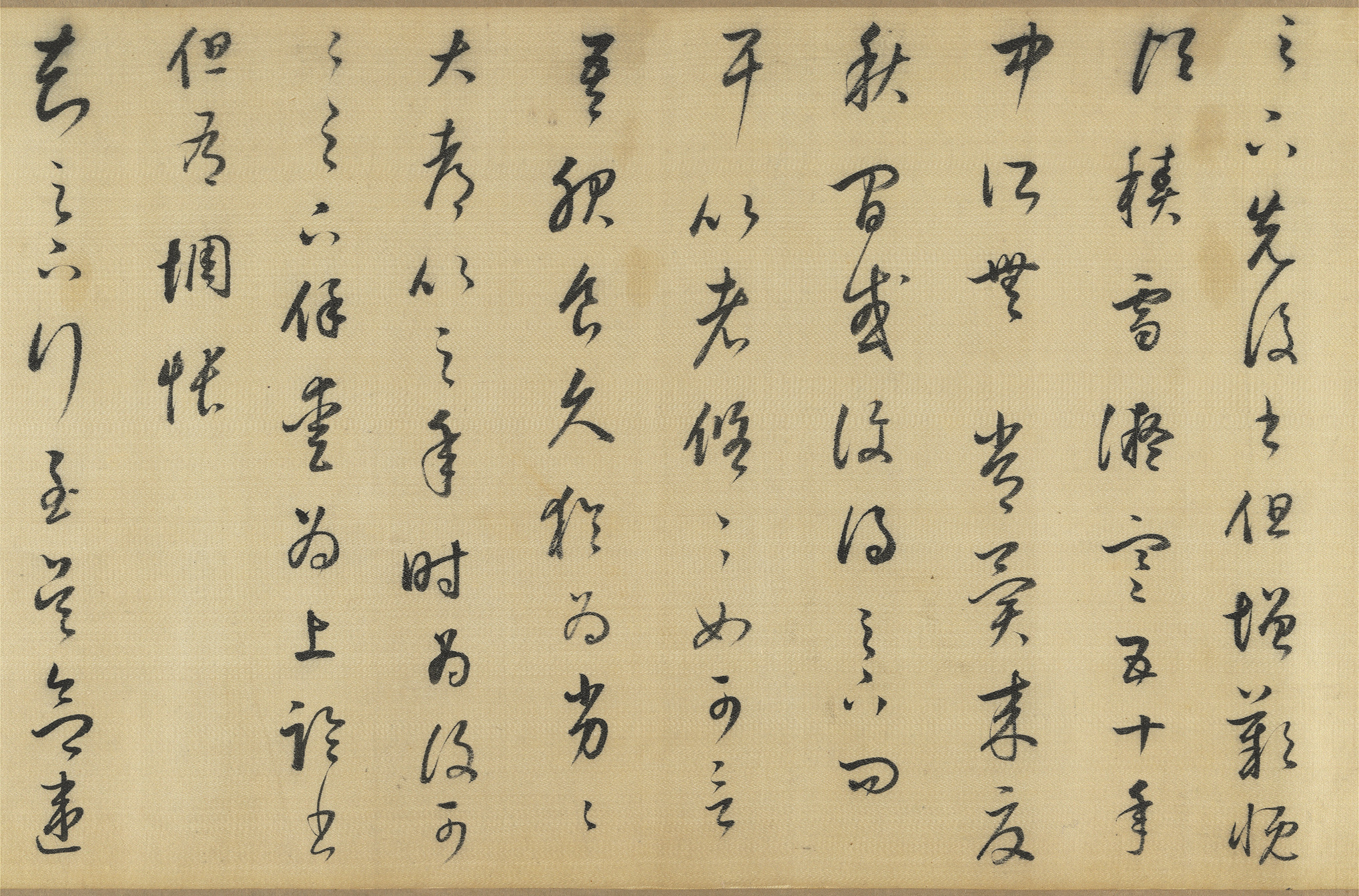

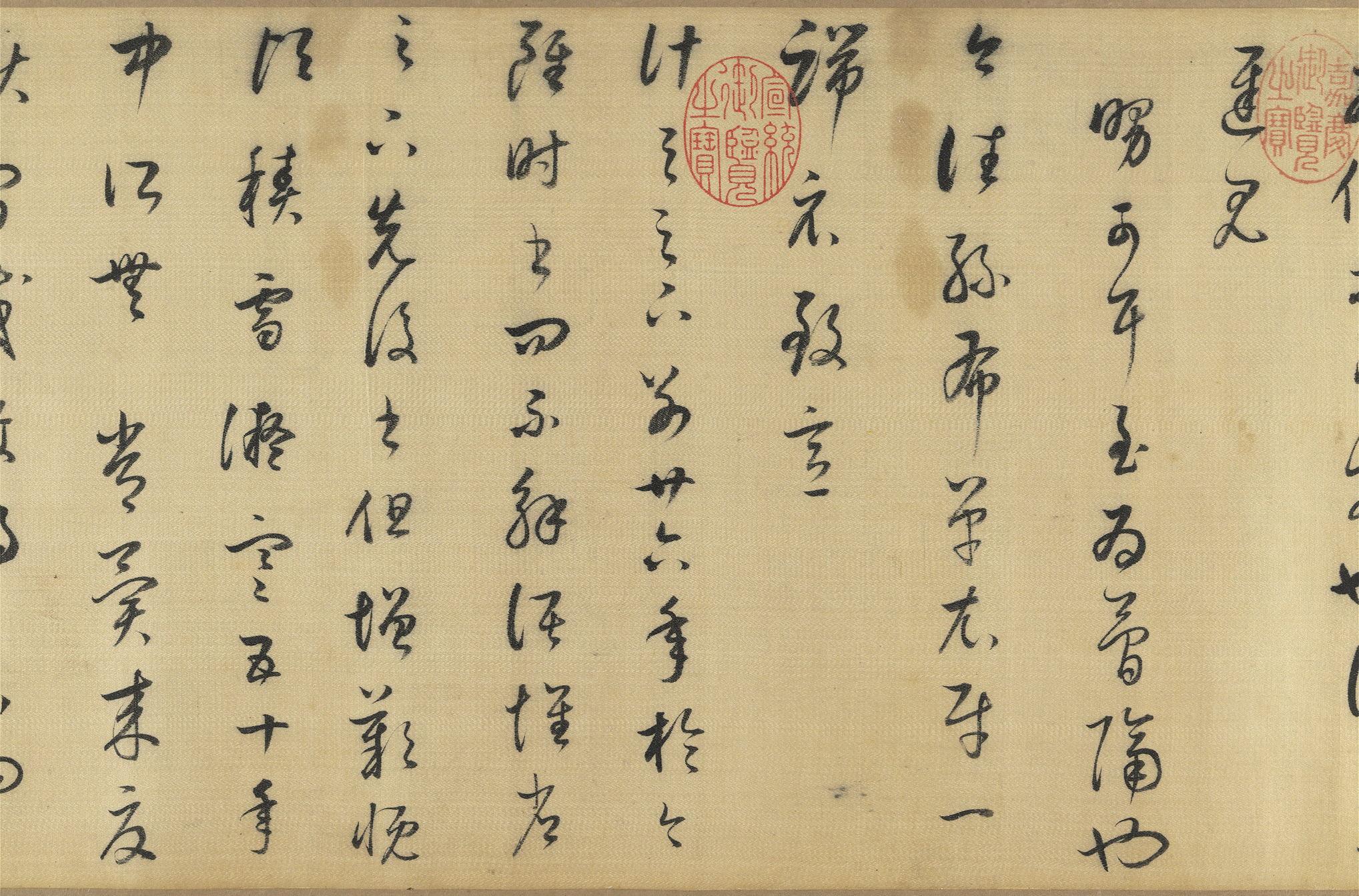

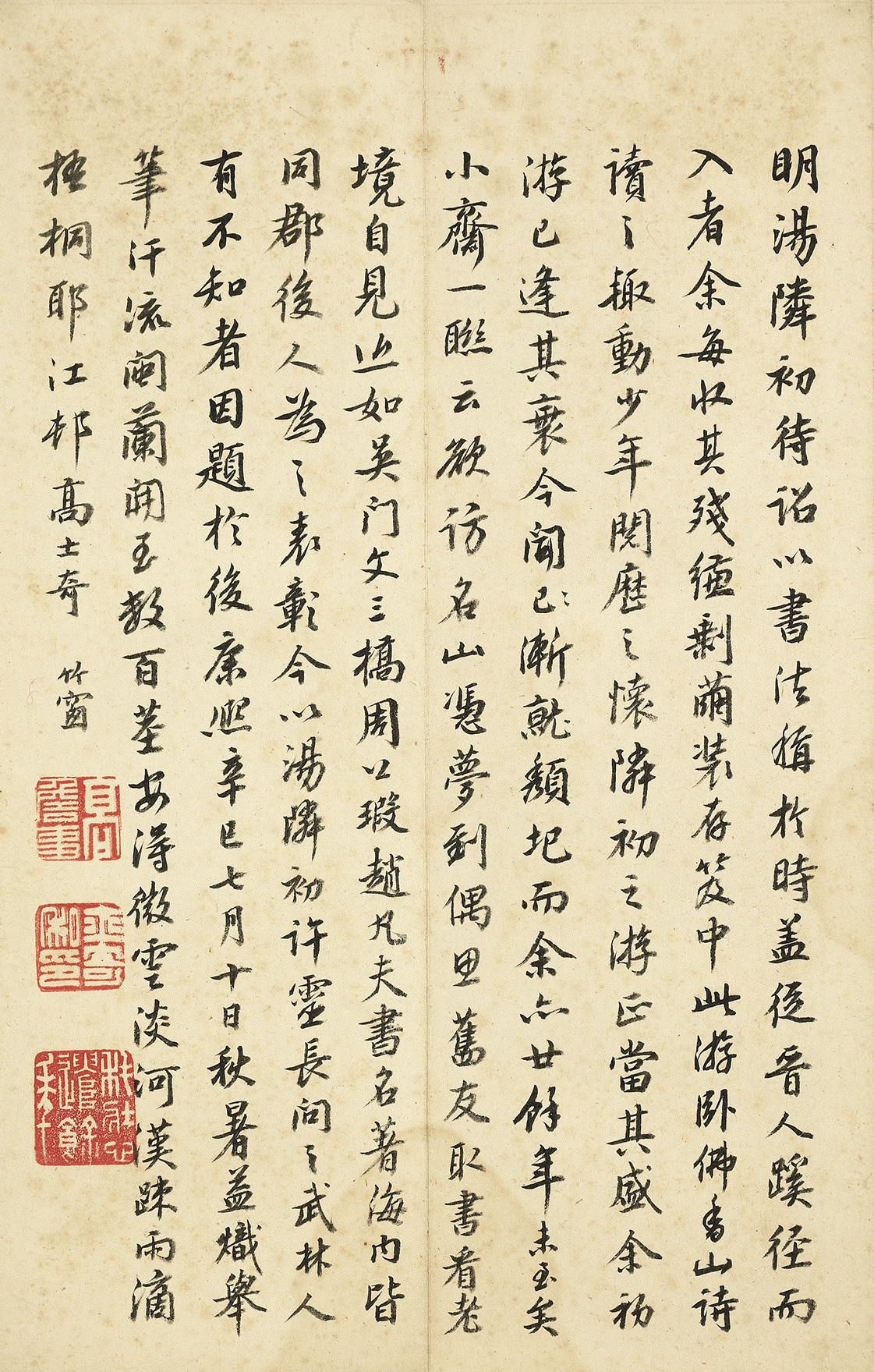

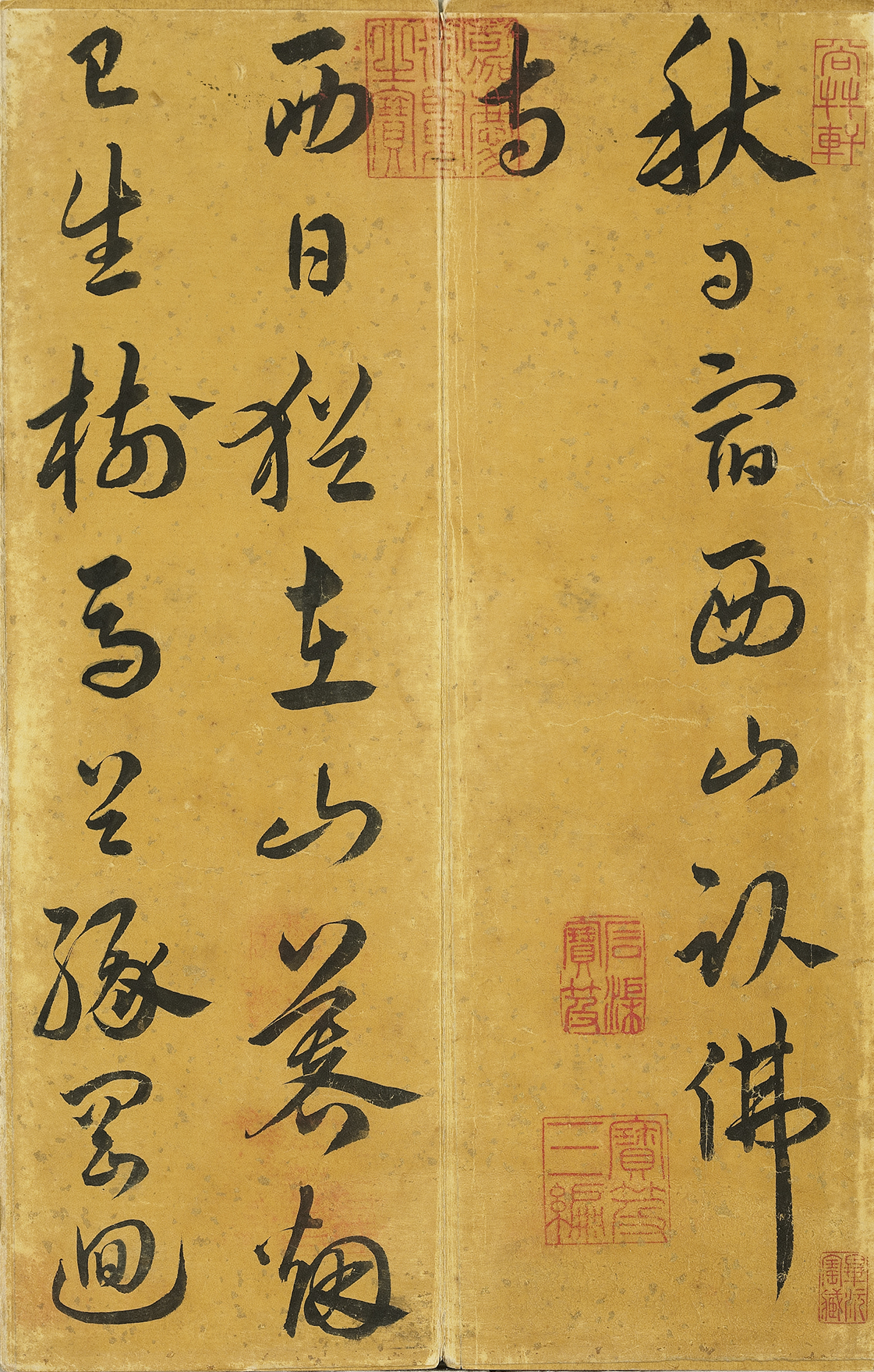

Poems on Traveling to the Western Mountains

- Tang Huan, Ming dynasty

Tang Huan (dates of birth and death unknown), had the style name Yaowen and the sobriquet Linchu. A native of Hang County in present day Zhejiang, he passed the imperial examinations at the provincial level in the fourth year of Ming dynasty emperor Longqing's reign (1570). Tang was both a talented painter as well as an expert carver of seals. Gao Shiqi (1644-1703) once said of Tang, "renowned in his own lifetime for his calligraphy, he embarked upon his path by studying the Jin dynasty masters."

This work contains two poems, entitled "Taking Lodging at Lying Buddha Temple in the Western Mountains in Autumn" and "A Trip to Fragrant Hills Temple." Revealing the influence of Yuan dynasty "mixed script," its calligraphy contains a blend of kaishu, xingshu, caoshu, and zhangshu (regular script, cursive script, grass script, and draft script, respectively). However, clearly marching to the beat of his own drummer, Tang writes in a manner freer, bolder, and more untrammeled than his influences.