Selections

-

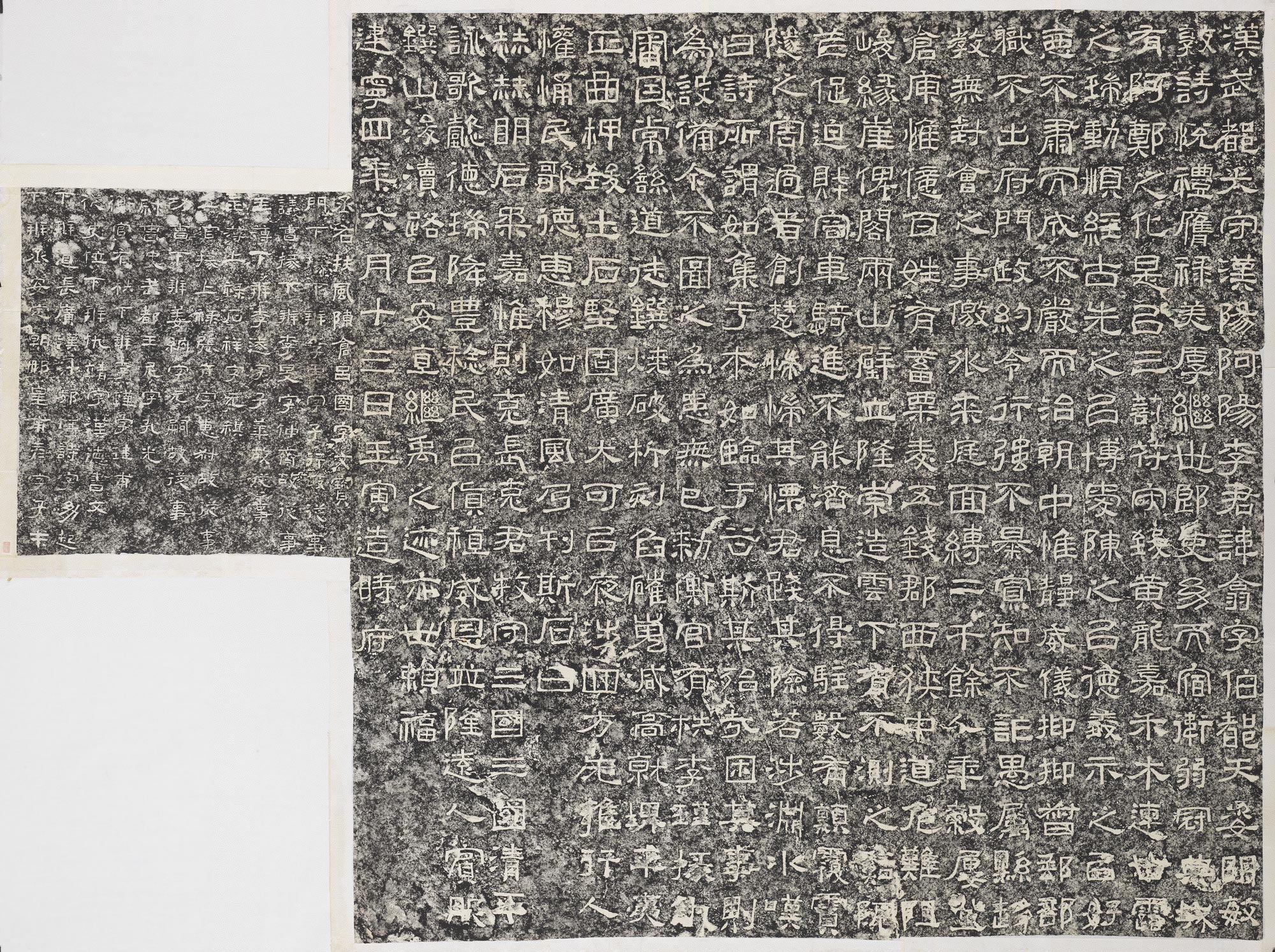

Li Xi Stele

- Chou Jing, Han dynasty

The Li Xi Stele, also known as the Western Pass Ode, was carved directly into the rock of Tianjing Mountains in present day Cheng county in Gansu province in 171 CE. The stele's inscription commemorates the official Li Xi's renovation of the plank road in the western pass of the Tianjing Mountains. The text was drafted and inscribed by Chou Jing, who used a very uniform hand in this work of calligraphy. Chou used square-shaped brushwork for both the initial and final parts of the strokes, leading to clearly defined corners. In contrast, he switched to rounded brushstrokes when tracing curves to produce softness that pleasingly offsets the characters' hard angles. Variations in brush pressure in the left- and right-falling strokes are very subtle, a feature that gives the calligraphy a simple, staid beauty. All of the characters in the inscription are upright and foursquare, and are endowed with a proportionate abundance of negative space. The inscription's orderly columns and rows give it a crisp neatness. The overall effect is to impress viewers with a sense of dignity and majesty.

-

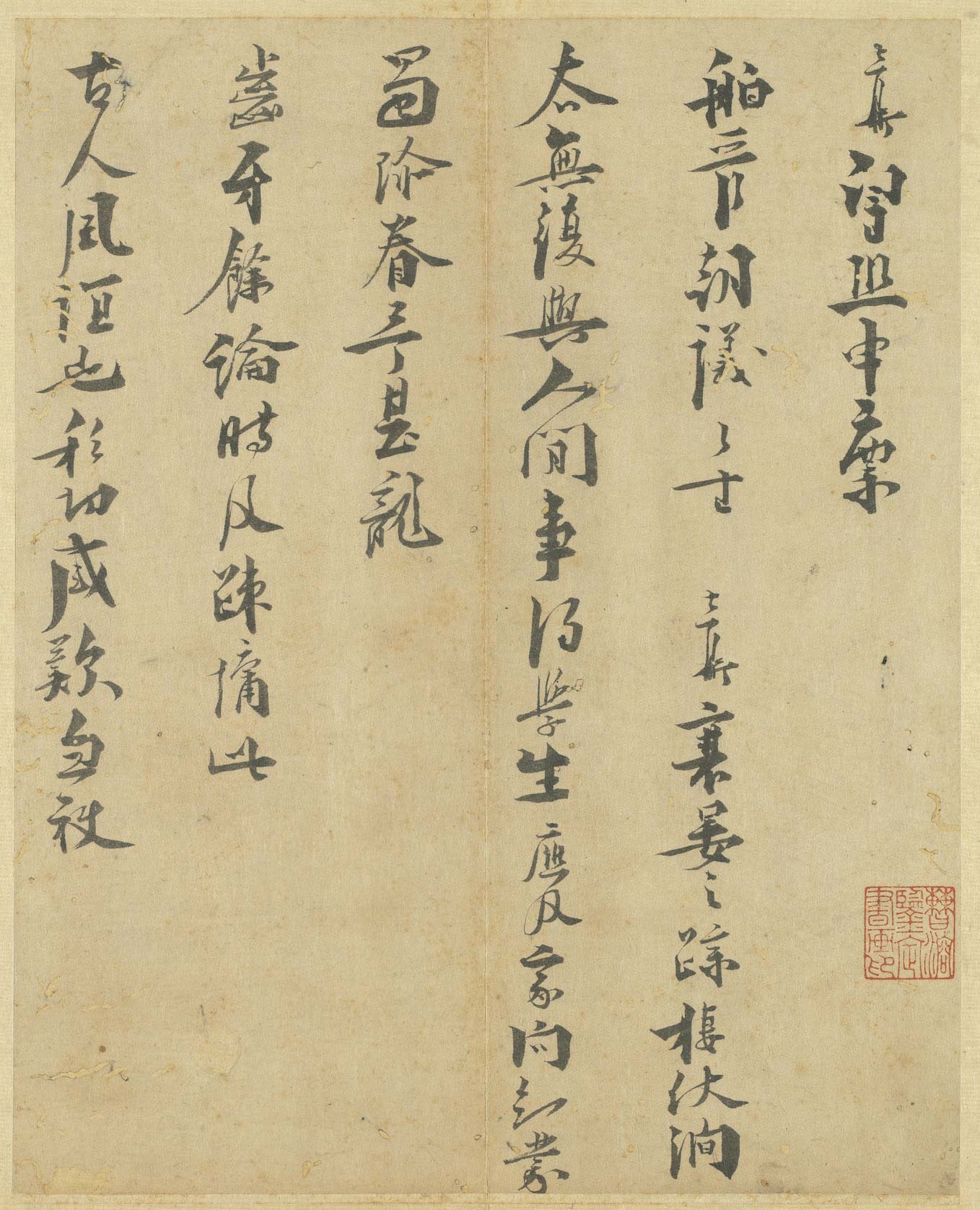

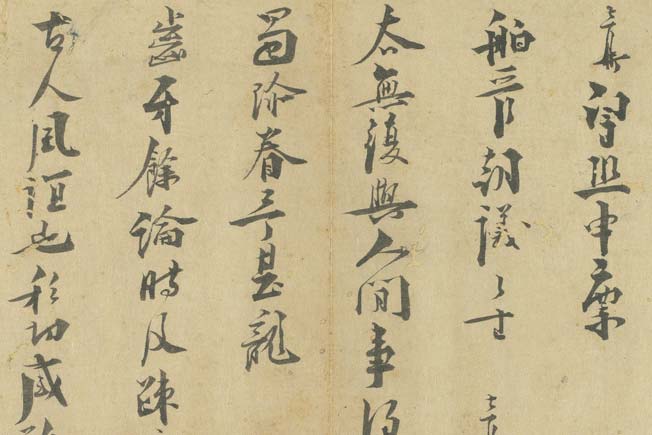

Letter to a Customs Official

- Ye Mengding, Song dynasty

Ye Mengding (1200-1279) was a famous official who lived during the Southern Song dynasty. He is known to have frequently intervened in government affairs to plead on behalf of common people, and to have stood up to chancellor Jia Sidao (1213-1275).

This letter was written circa 1273 after Ye retired from his official post and went to live in seclusion. The letter is written in the “Yan style” of Tang dynasty calligrapher Yan Zhenqing. This style of running script couples light, thin horizontal brushstrokes with thick, heavy vertical strokes. However, Ye's calligraphy also shows hard angles in the turns of the brush, numerous places where the brush tip is revealed, and a swift, almost fierce hand. In this work there are marked contrasts between long and short strokes, heavy and light pressure, and the alternating tightness and diffuseness of the lines. The characters here vary greatly, sometimes appearing elongated, and other times flattened. In spite of these variations, the smaller, narrower characters never feel cramped, nor do the wider and flatter characters seem ponderous. Rather, both types of characters exude an air of robustness and dexterity. -

Four Poems on Ink

- Wu Zhichun (fl. 14th century), Yuan dynasty

Wu Zhichun (fl. 14th century), was a poet and seal carver who was especially talented at writing lishu (official script).

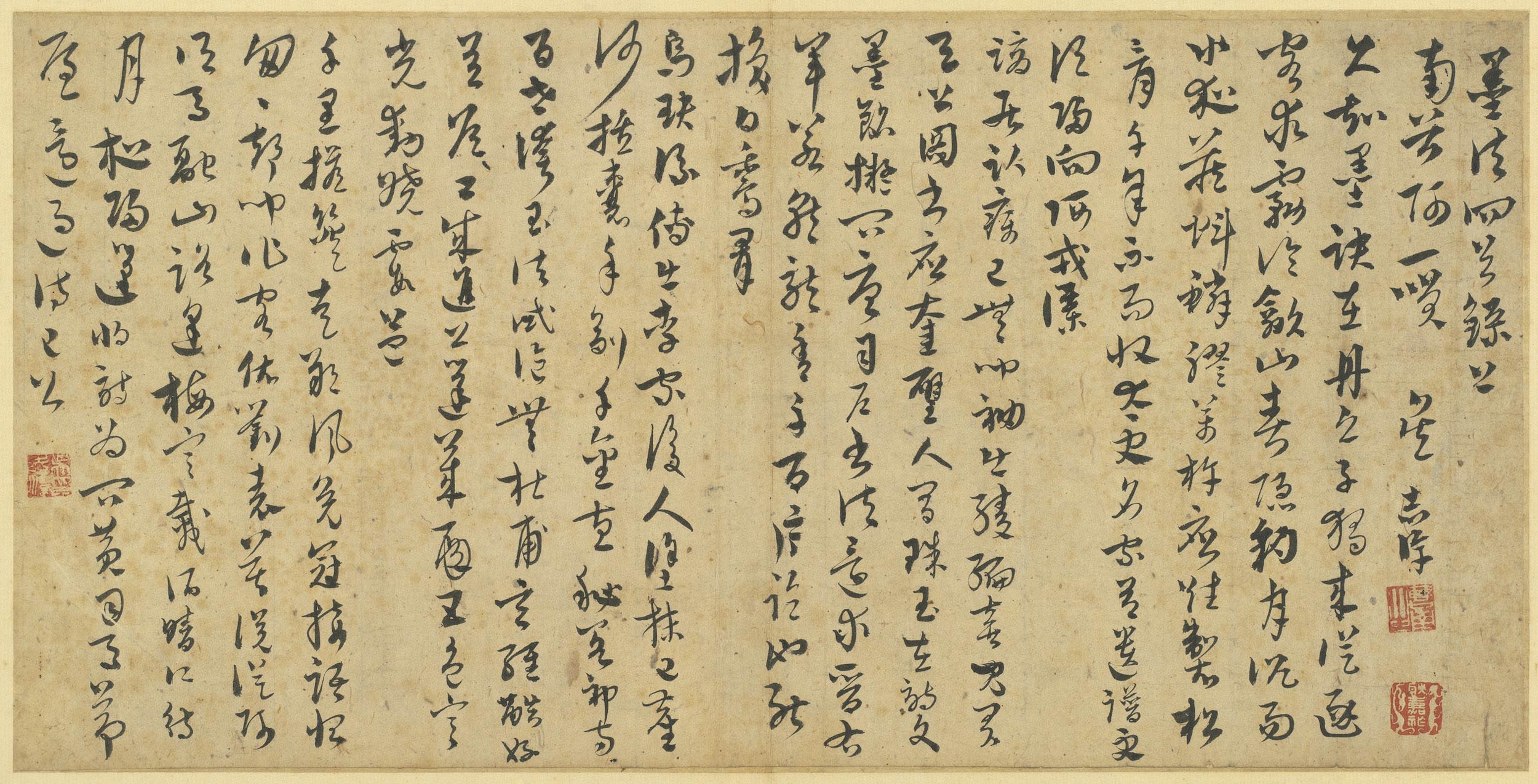

This work comprises four poems written in zhangcaoshu (cursive or “grass” script that was ostensibly for writing drafts), each of which is four lines long with seven characters per line. Wu Zhichun wrote them to extol the virtues of excellent ink, which was hard to come by, and to express nostalgic sentiments towards his friends. The characters in this work are all clearly separated and given slightly broadened structures. Ink is especially heavy where characters are dotted and in short horizontal strokes. Turns of the brush are quite pronounced the in right-falling strokes, a feature that gives full play to the charms of lishu calligraphy. Wu also paid homage to Kangli Zishan's (1295-1345) style by elongating many strokes, giving the characters subtly raised “shoulders” on their right sides, and maintaining tight adherence to the center point in their structures. Other traits include a tendency towards angular brushwork, a preference for cornering over rotating the brush, and allowing the brush's tip to be revealed. These traits give Wu's calligraphy a robust, almost precipitous beauty and make it a celebrated specimen of zhangcaoshu dating to the transitional period between the late Yuan and early Ming dynasties. -

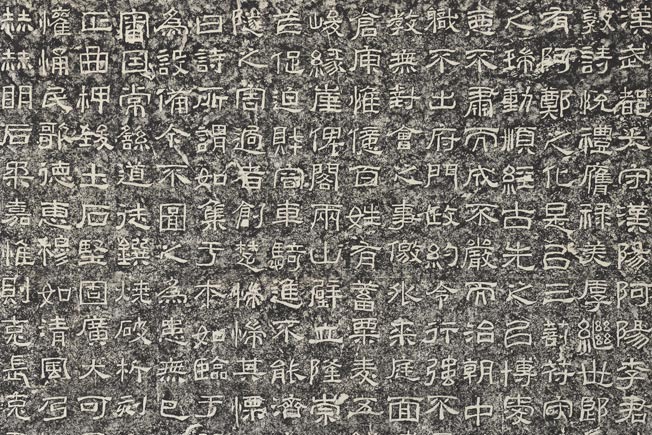

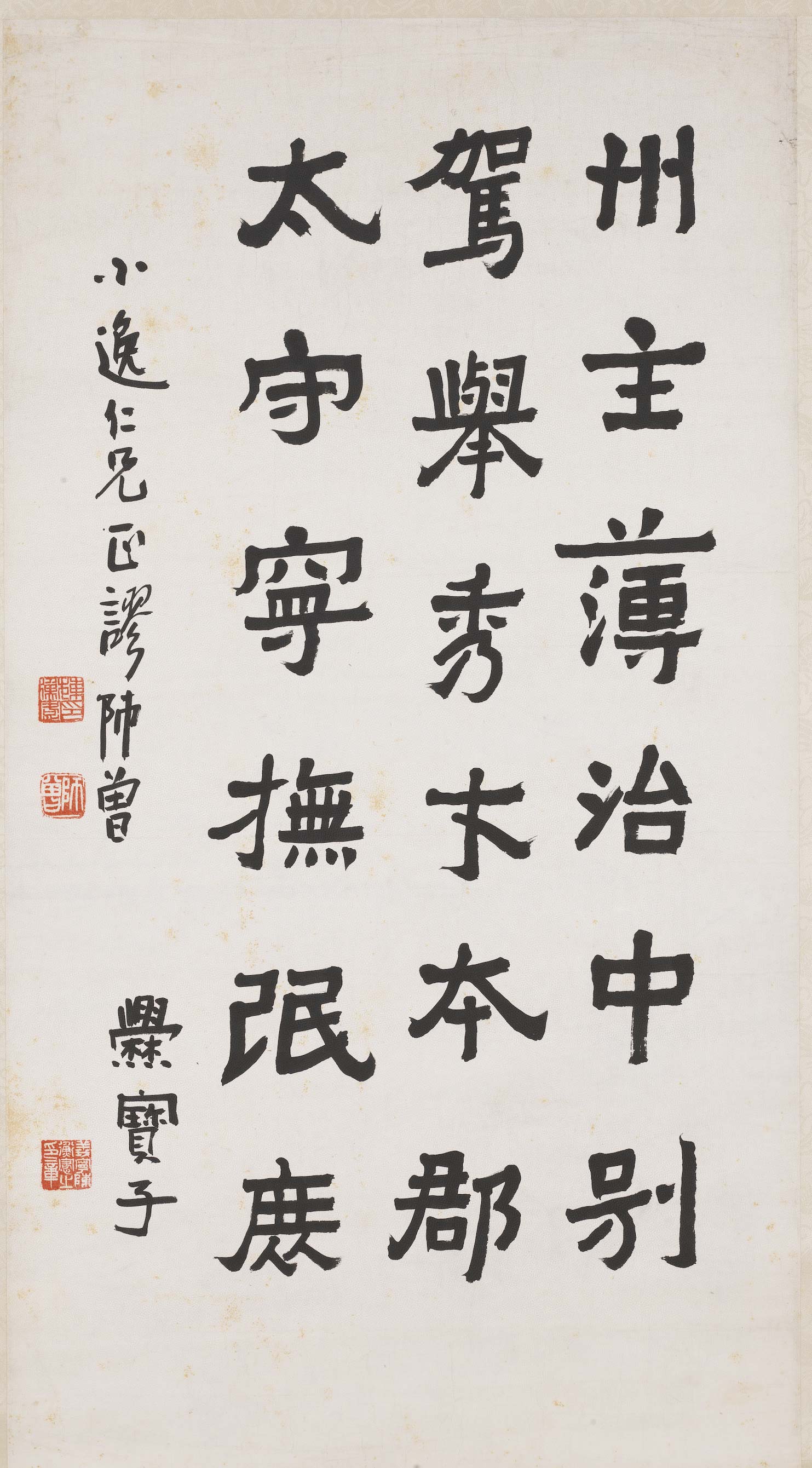

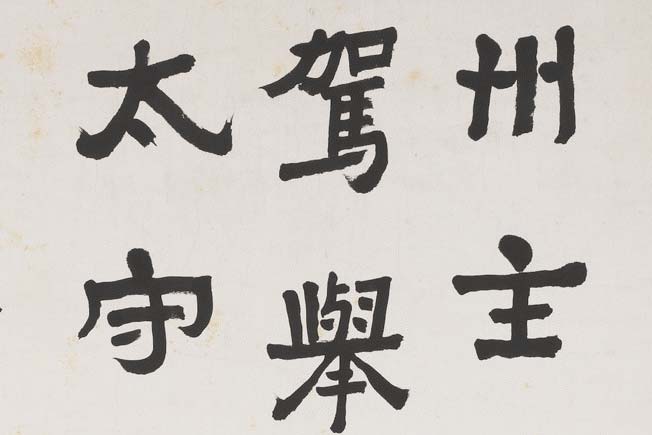

A Copy of the Huashan Stele

- Weng Fanggang, Qing dynasty

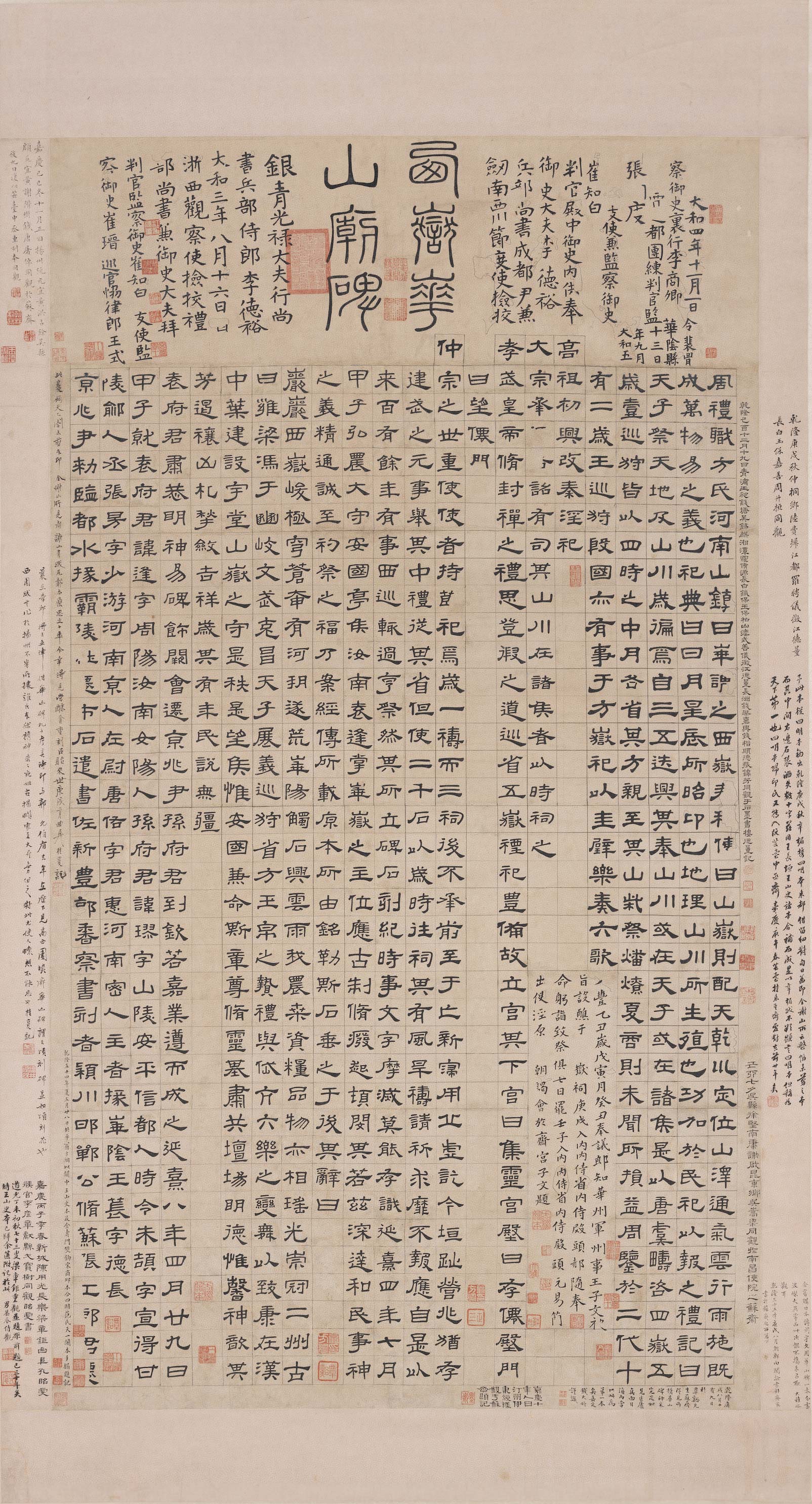

In 165 CE, Yuan Feng erected the Huashan Stele in order to memorialize the Han dynasty emperors' performance of sacrificial rites atop Mount Hua, their restoration of its temples, and their prayers for rain. This stele also recorded the name of the scribe who created it—Guo Xiangcha—making it an incredibly rare specimen. The Huashan Stele was erected on Mount Hua before the Western Peak Temple, but it was destroyed by an earthquake in 1555, after which its only remaining traces were four rubbings.

Weng Fanggang (1733-1818) created this work by using the shuanggou kuotian or “double-outlining” technique to copy a rubbing of the stele in 1789, going so far as to copy the inscriptions placed atop the rubbing during the Tang dynasty. Although the characters' structures are quite rectangular and the strokes appear slightly too vigorous, this work still succeeds in conveying to the viewer an impression of the original stele. This piece is widely regarded as an indispensable resource for researchers into the history of calligraphy. -

A Study of the Cuan Baozi Stele

- Chen Hengke, Qing dynasty

Chen Hengke (1876-1923) had the style name Shizeng. He was a native of Ningzhou in present day Jiangxi province, renowned in his time as a calligrapher, painter, and seal carver.

This study of the Cuan Baozi Stele engages with the original's pronouncedly rectangular brushwork and the many places in which the brush's tip is revealed. Chen instead opts for more rounded brushwork and the concealment of the brush's tip, an approach that fleshes out the structure of the characters whilst also making them more delicate. He also produces characters that appear more upright and foursquare than the original's and shrinks large characters while enlarging small ones. These modifications conjoin to create an ingeniously pleasing composition. There is symmetry between the first and third columns, while the middle column appears as though randomly placed. A subtle tension is thus created that leads to the sense of emptiness in the midst of substance. This work's greatness lies in its synergetic interactions between symmetry and asymmetry as well as order and chaos.