In Pursuit of Curios in the Market

The prosperity of Jiangnan district in the late Ming encouraged the

escalating needs for antiques

and luxuries of the public. The desire for knowledge of connoisseurship also motivated the

development of publishing industry. The catalogues on connoisseurship of various objects, the

rise of publications such as the "Yangxian Minghuxi", the "Fangshi Mopu" had

appeared to be a

cultural phenomenon that followed the trend.

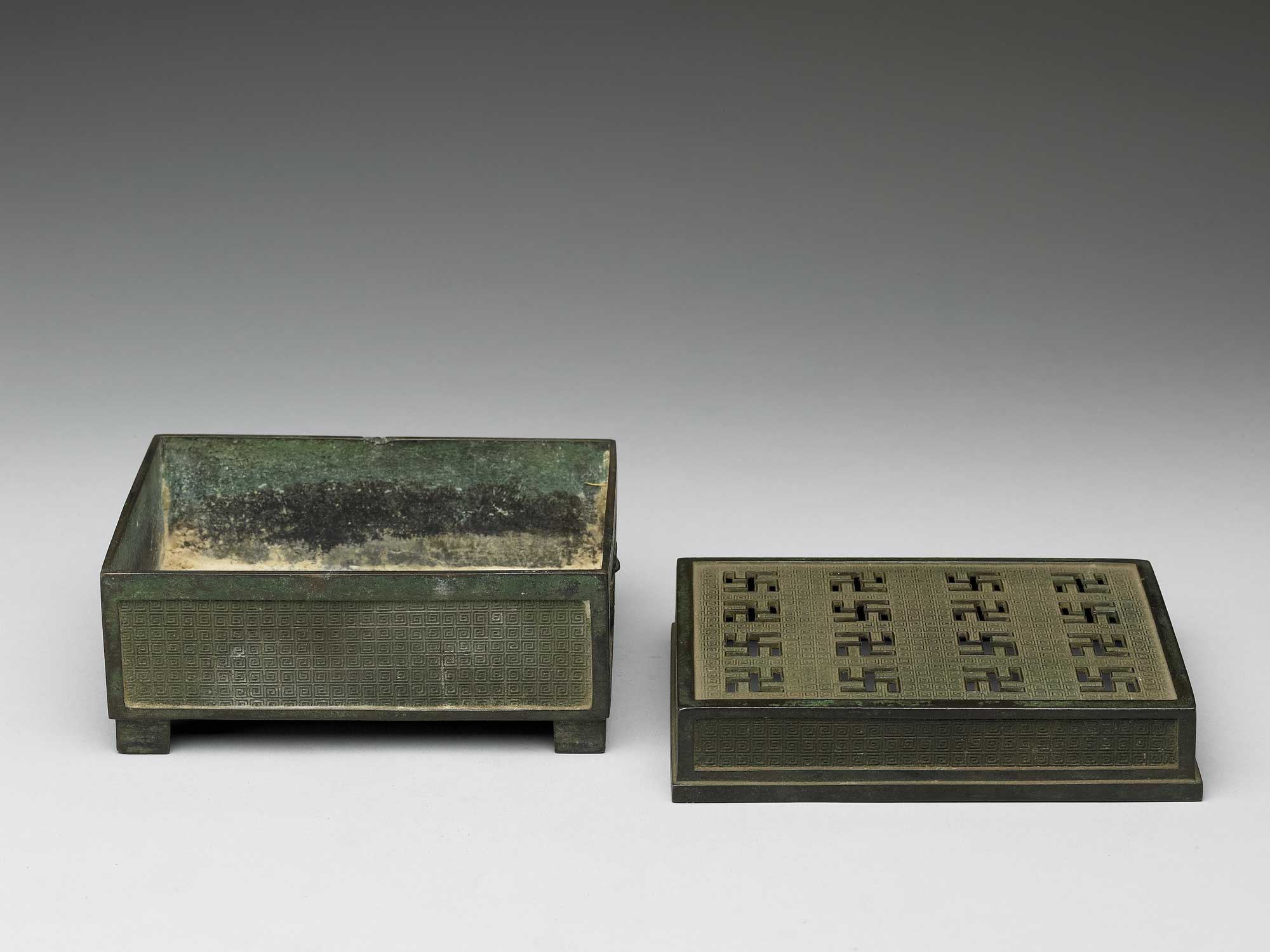

The nobles placed orders of custom-made objects according to

their tastes, and scholars aspired

to the trend were enquiring bronzes of the three dynasties, which were documented in the ancient

catalogues. Local workshops and stores had also promoted merchandises with their own marks. The

craftsmen with exquisite skills, such as porcelain master Zhou Danquan, silversmith Zhu Bishan,

and jade carver Lu Zigang, their works with incredible expertise that were sought after by the

market. Unfortunately, the authentic works were expensive and rare, and in addition to that the

lack of true connoisseurship had also stimulated a great amount of calligraphies, paintings, and

objects that imitated ancient pieces were circulated in the market to greet the needs. Moreover,

even became the mainstream. This situation indicates the significant barrier between the reality

and the literati's ideal from the statements of connoisseurship publications.

-

Porcelain Tripod with Animal-mask Design and Arch Handles in Yellow glaze

- Ming dynasty (1368-1644)

Zhou Danquan was an active master in creating objects in antiquarian style in the circle of antiquity connoisseur in the end of 16th century. According to the legend, once he saw a white porcelain Ding tripod at the house of Tang Taichang (Jinshi, imperial scholar, in 1571), so he borrowed from the owner and carefully noted down its design and patterns. Soon after that, he copied a porcelain tripod which looked the same as the original one. It was so hard to differentiate between the copy and original ones that Tang even bought the copy. This work is also a round tripod. Even though its bottom has a mark of "made by Zhou Danquan," the evidence is not enough to prove it was actually made by Zhou. Therefore, this exhibition sees it as a production from a celebrated craftsman or renowned workshops through word of mouth.

-

Square Yu Basin with Nine Carved Dragons in Yellow Glaze

- Wanli reign (1573-1619), Ming dynasty

Along the rim of this work is a stamped mark. The characters "Wan li nian wu wei zhi (Made by Wu Wei in the Wanli reign)" indicates that this porcelain vessel with nine dragons was made by Wu Wei, one of the few ceramic artists who left their names on their works. According to the legend, he was skilled in trimming clay and controlling firing; and he could make porcelain cups as thin as egg shell.

-

Silver Raft of "Zhang Qian Riding a Raft" with Zhu Bishan's Mark

- Yuan to Ming dynasty(1217-1644)

Publications from the late Ming dynasty, such as Wang Shizheng's Gubugu Lu documented that Zhu was famous for his silversmith, and the price of his works or from other masters specialized in different fields were "double than normal". This shows the master pieces were highly pursued in the market.

-

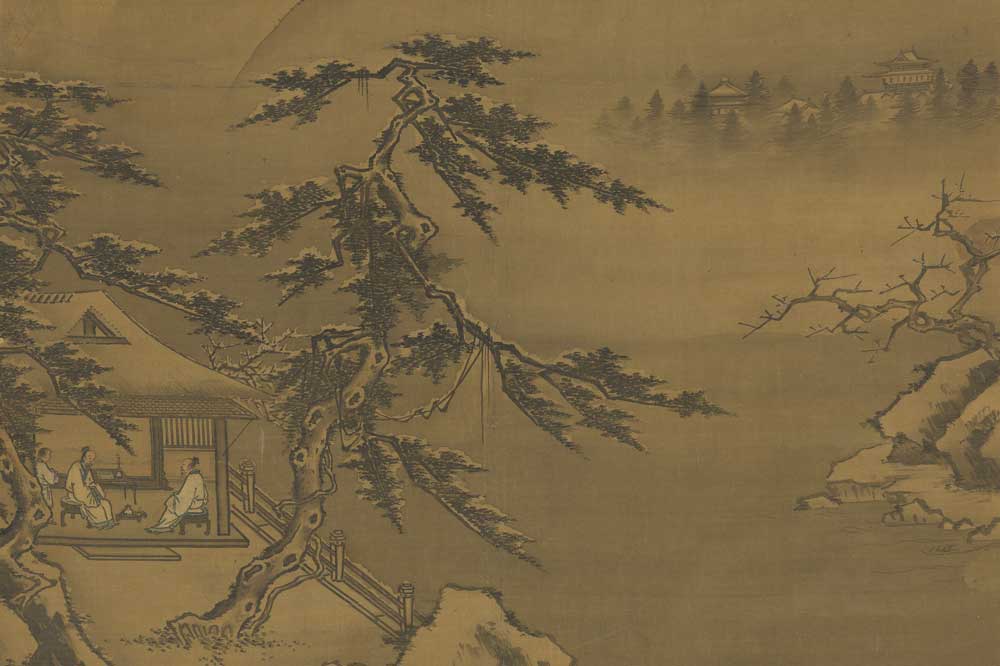

Mountains in Snow

- Attributed to Ma Yuan (active between 1190-1225)

- Song dynasty

Treatise on Superfluous Things marks several Zhe-school painters as the "heterodox school of paintings", and demanded the audiences not to collect their pieces. Zhong Li was one of the listed painters, and it should be the main reason that this painting forged Ma Yuan's signature.

-

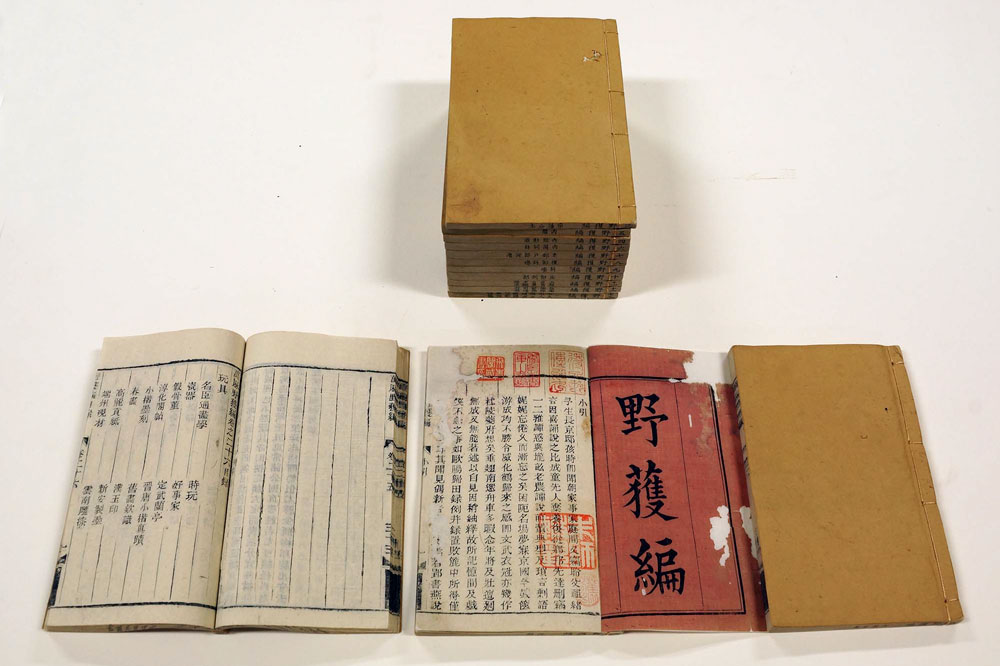

Wanli Yehuobian

Unofficial Matters from the Wanli Reign- Written by Shen Defu, Ming dynasty

- Small-sized imprint of the Qing dynasty

Written by the Ming scholar Shen Defu, the work was completed during the 34th and 35th year (1606-1607) of the Wanli reign. Part of the title specifies the time period covered by its contents, and the remainder indicates that the passages therein are largely gathered from the field, not based on any official or archival materials. From court regulations and anecdotes to local customs, its coverage, rendered in the biji (essay) style, is fairly broad. The fascicle on wanju (joyful objects) is dedicated to the connoisseurship of antiquities and paintings adorned by the author's contemporaries, and the subjects addressed include patingings, calligraphic works, trendy curios, porcelains, dilettantes, forgeries, calligraphic modelbooks, paper, inks, ink stones, lacquerwares, and fans.