Descriptions of the Works

-

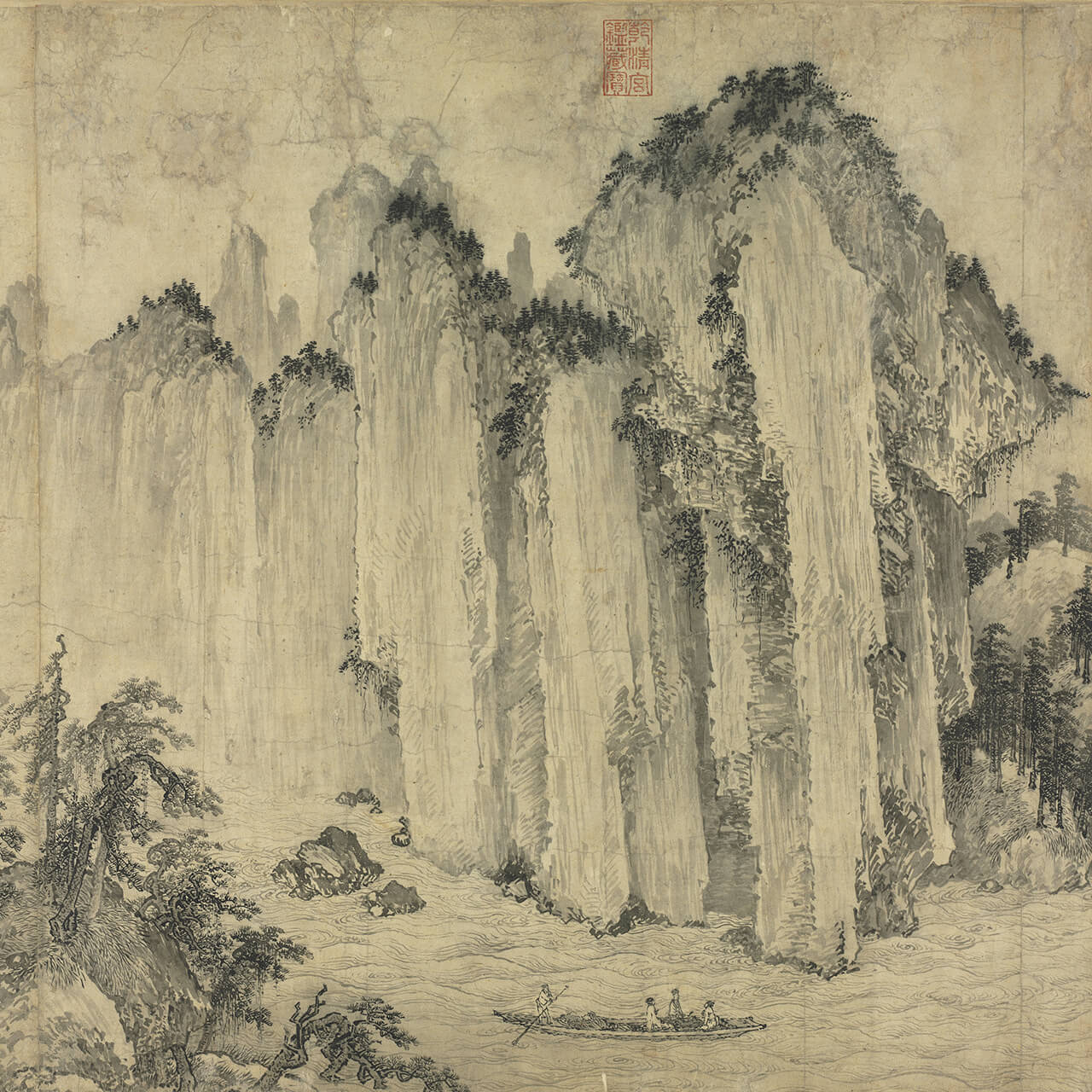

Autumn Woods and Flying Cascade (Open)

Autumn Woods and Flying CascadeAutumn Woods and Flying Cascade (Close)Autumn Woods and Flying Cascade

Autumn Woods and Flying CascadeAutumn Woods and Flying Cascade (Close)Autumn Woods and Flying Cascade- Fan Kuan (ca. 950-ca. 1031), Song dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 181 x 99.5 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in March 2012 as a National Treasure

-

Seated Portrait of Song Taizu (Open)

Seated Portrait of Song TaizuSeated Portrait of Song Taizu (Close)Seated Portrait of Song Taizu

Seated Portrait of Song TaizuSeated Portrait of Song Taizu (Close)Seated Portrait of Song Taizu- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 191 x 169 cm

- Provisionally classified by the National Palace Museum as a National Treasure

-

Seated Portrait of Song Renzong's Empress (Open)

Seated Portrait of Song Renzong's EmpressSeated Portrait of Song Renzong's Empress (Close)Seated Portrait of Song Renzong's Empress

Seated Portrait of Song Renzong's EmpressSeated Portrait of Song Renzong's Empress (Close)Seated Portrait of Song Renzong's Empress- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 172.1 x 165.3 cm

- Provisionally classified by the National Palace Museum as a National Treasure

- Display period: 2018/10/04-11/14

-

Calico Cat Under Noble Peonies (Open)

Calico Cat Under Noble PeoniesCalico Cat Under Noble Peonies (Close)Calico Cat Under Noble Peonies

Calico Cat Under Noble PeoniesCalico Cat Under Noble Peonies (Close)Calico Cat Under Noble Peonies- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 141 x 107.3 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in March 2012 as a National Treasure

-

Refusing the Seat (Open)

Refusing the SeatRefusing the Seat (Close)Refusing the Seat

Refusing the SeatRefusing the Seat (Close)Refusing the Seat- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 146.8 x 77.3 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in June 2013 as a National Treasure

-

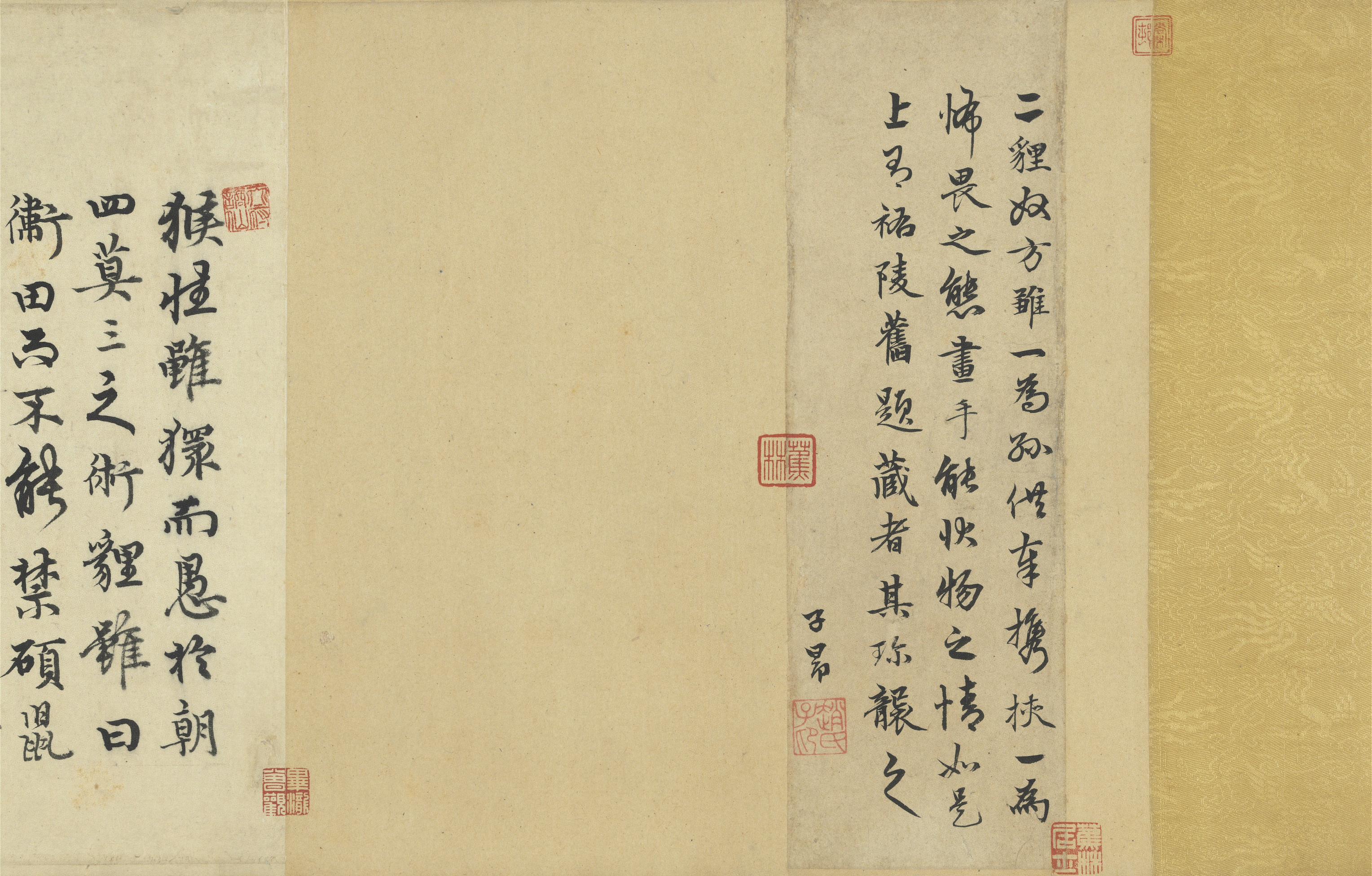

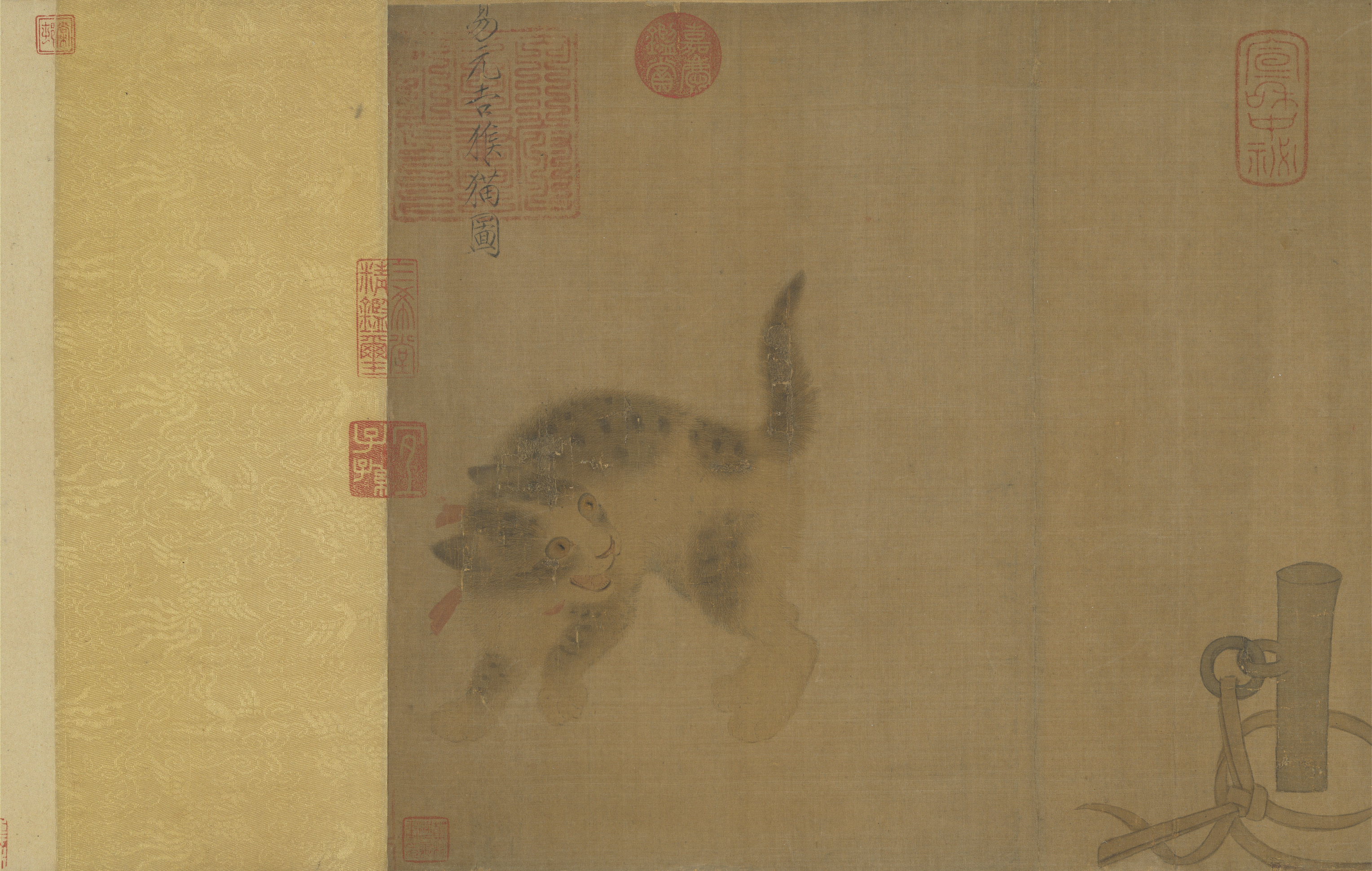

Monkey and Cats (Open)

Monkey and CatsMonkey and Cats (Close)Monkey and Cats

Monkey and CatsMonkey and Cats (Close)Monkey and Cats- Yi Yuanji (latter half of the 11th c.), Song dynasty

- Handscroll, ink and colors on silk, 31.9 x 57.2 cm

- Provisionally classified by the National Palace Museum as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/11/15-12/25

-

Children Playing on a Winter Day (Open)

Children Playing on a Winter DayChildren Playing on a Winter Day (Close)Children Playing on a Winter Day

Children Playing on a Winter DayChildren Playing on a Winter Day (Close)Children Playing on a Winter Day- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 196.2 x 107.1 cm

- Provisionally classified by the National Palace Museum as a National Treasure

-

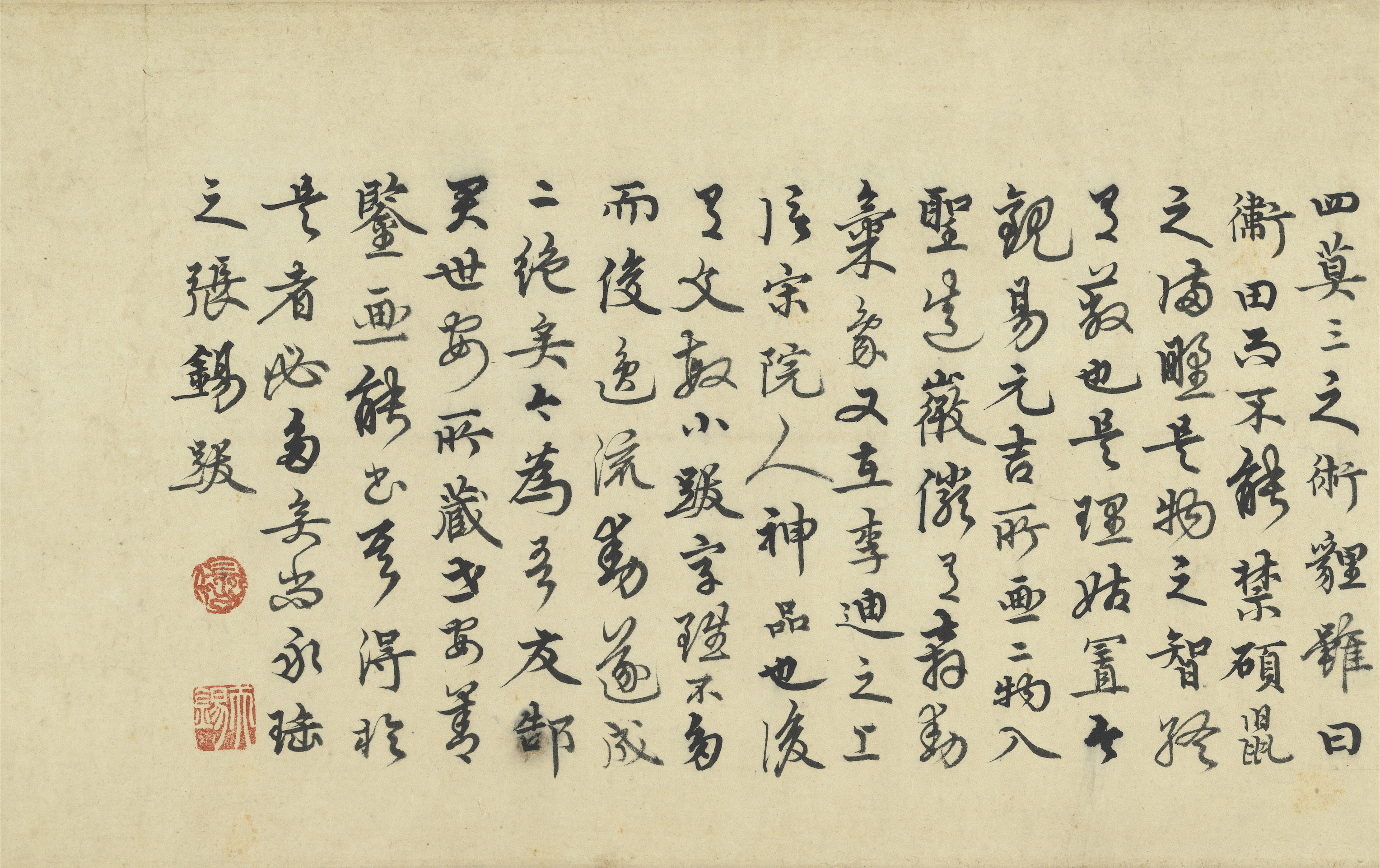

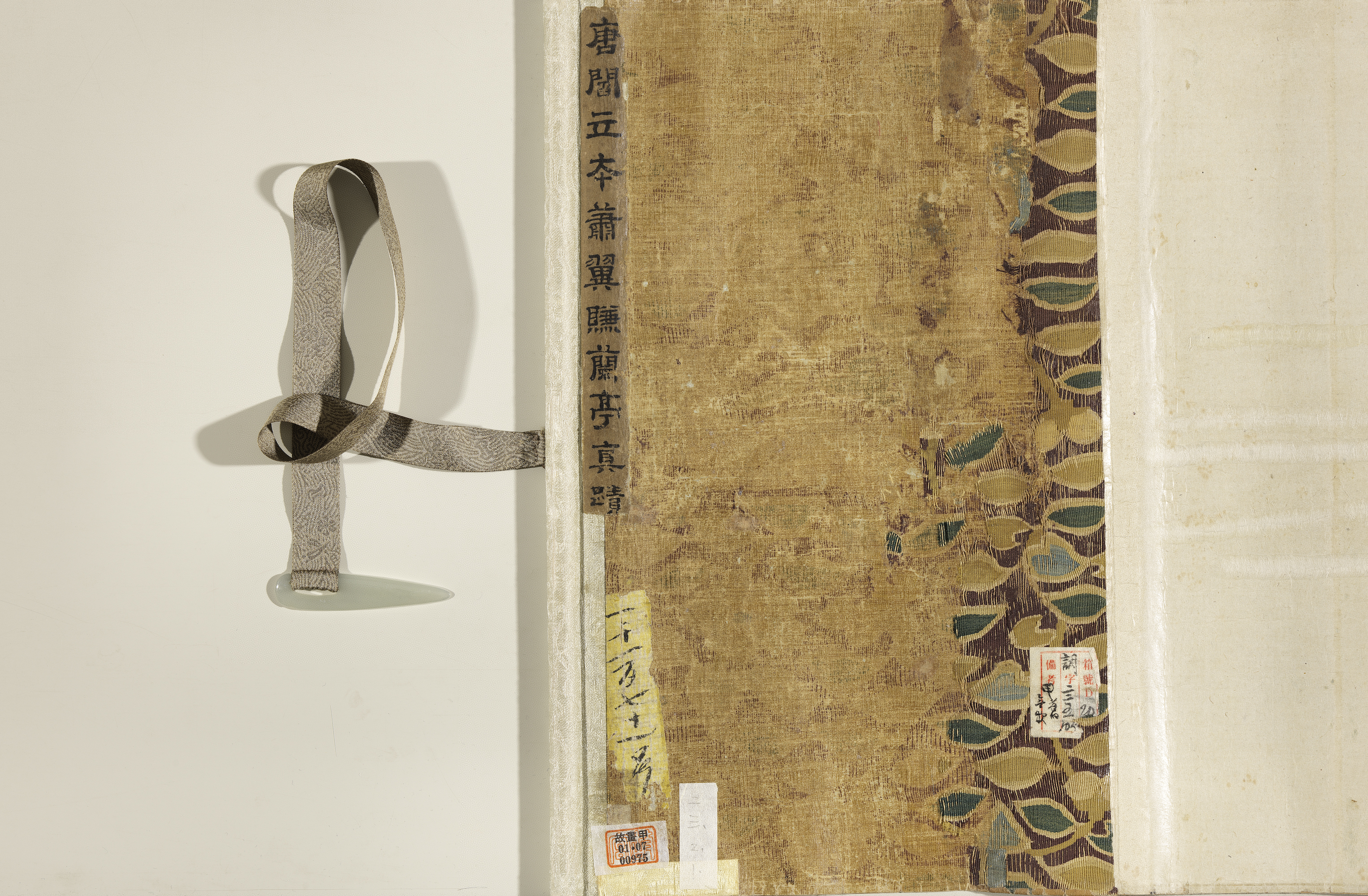

Xiao Yi Acquiring the "Orchid Pavilion Preface" by Deception (Open)

Xiao Yi Acquiring the "Orchid Pavilion Preface" by DeceptionXiao Yi Acquiring the "Orchid Pavilion Preface" by Deception (Close)Xiao Yi Acquiring the "Orchid Pavilion Preface" by Deception

Xiao Yi Acquiring the "Orchid Pavilion Preface" by DeceptionXiao Yi Acquiring the "Orchid Pavilion Preface" by Deception (Close)Xiao Yi Acquiring the "Orchid Pavilion Preface" by Deception- Yan Liben (?-673), Tang dynasty

- 27.4 x 64.7 cm

- Handscroll, ink and colors on silk, 27.4 x 64.7 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in March 2012 as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/10/04-11/14

-

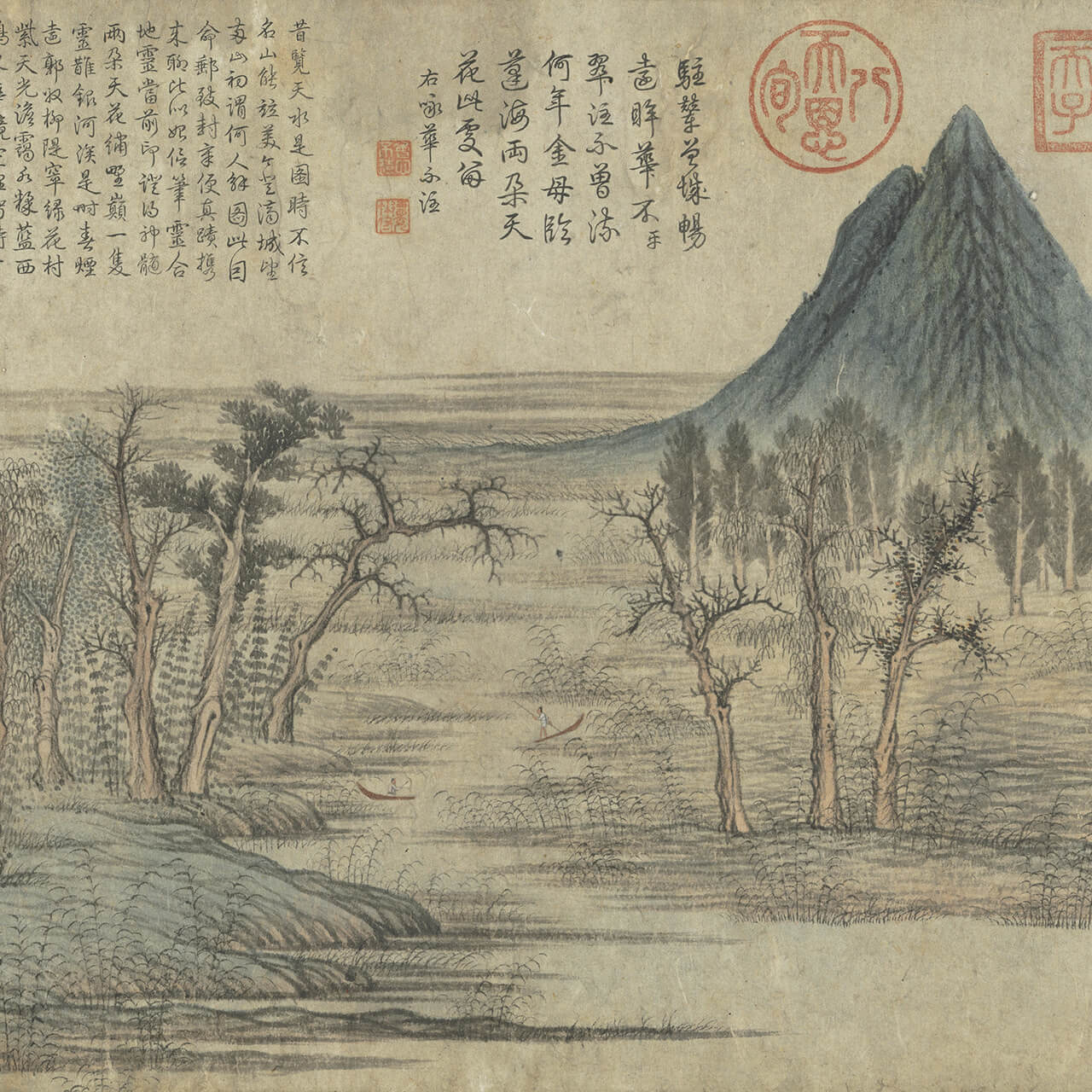

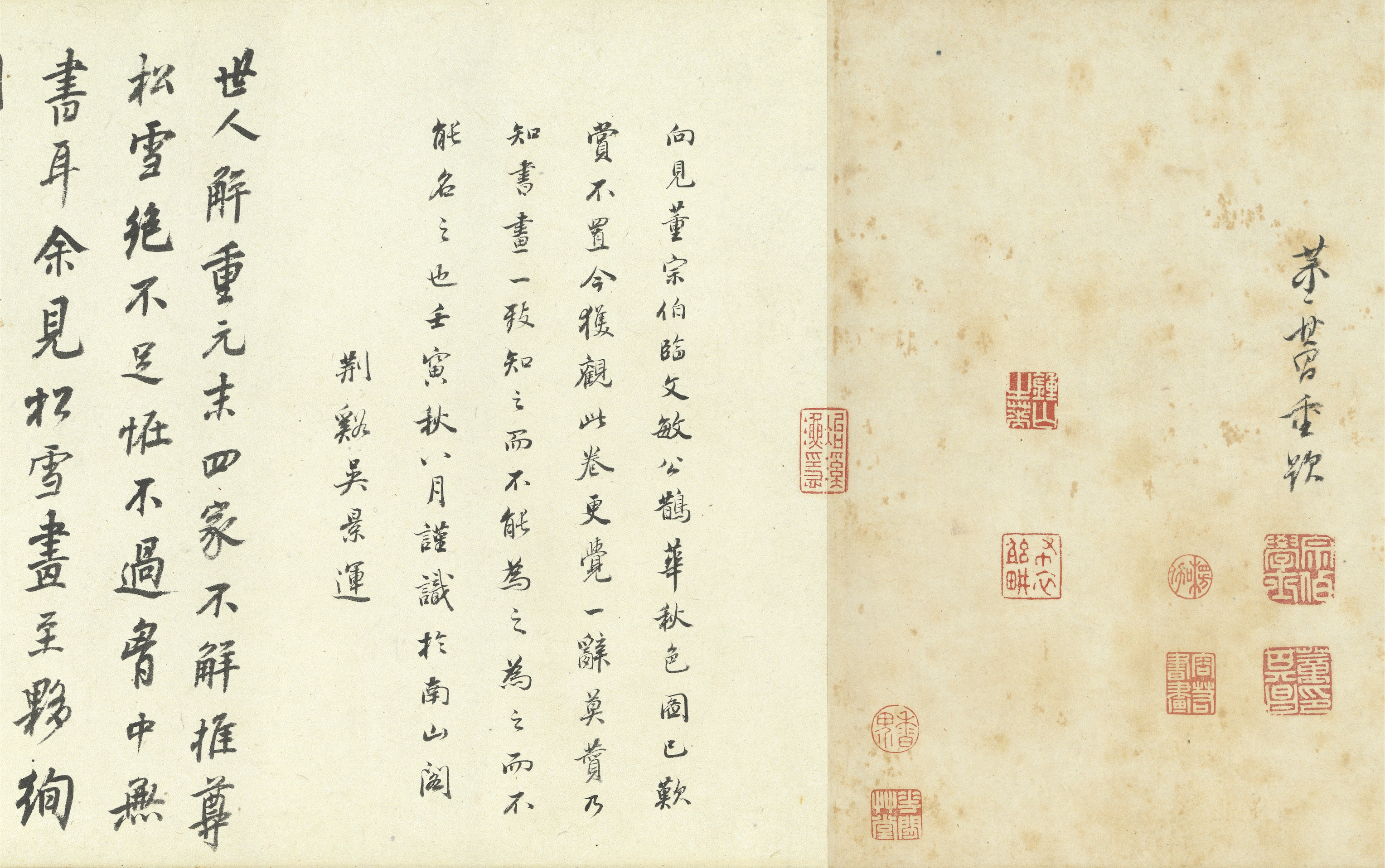

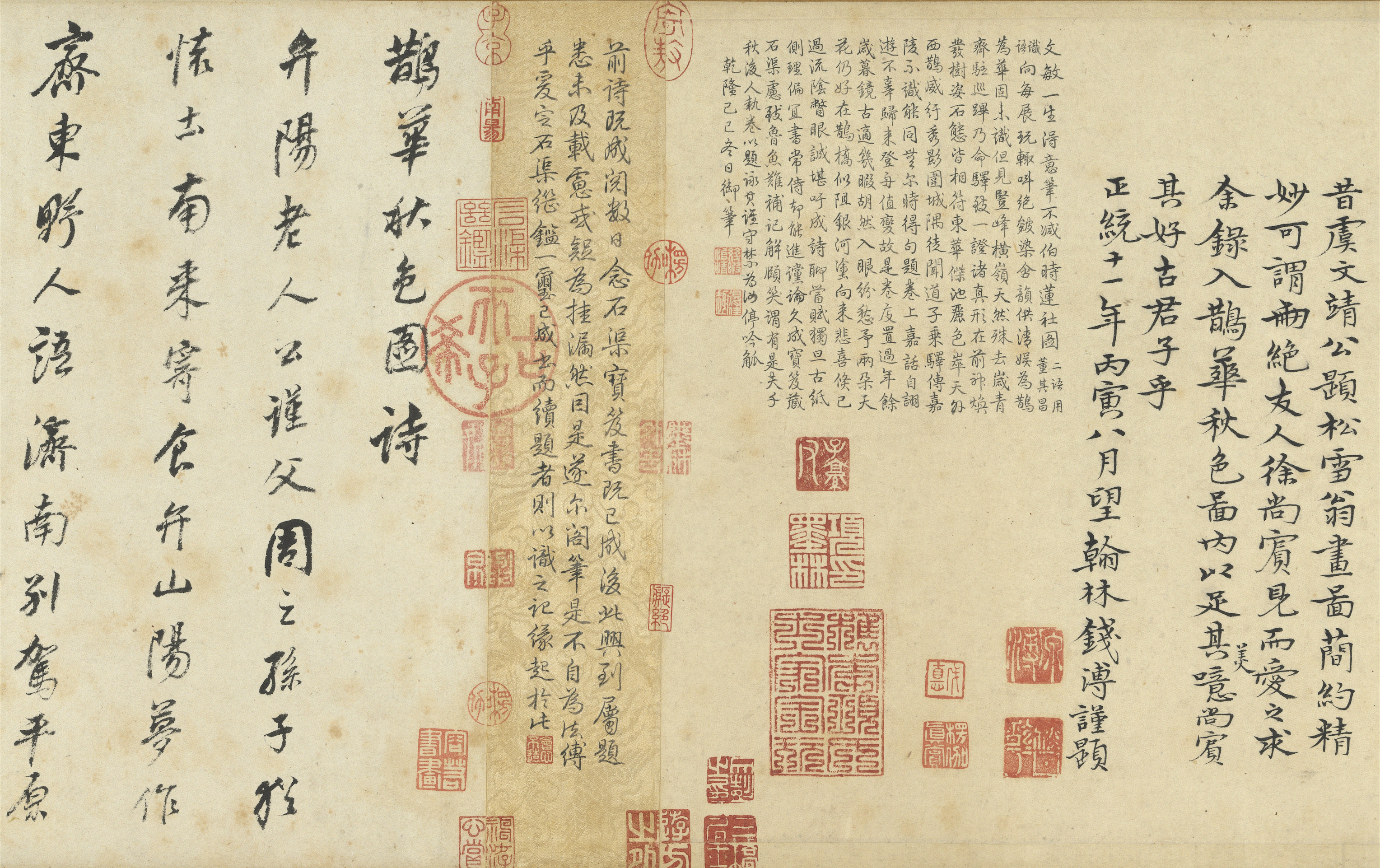

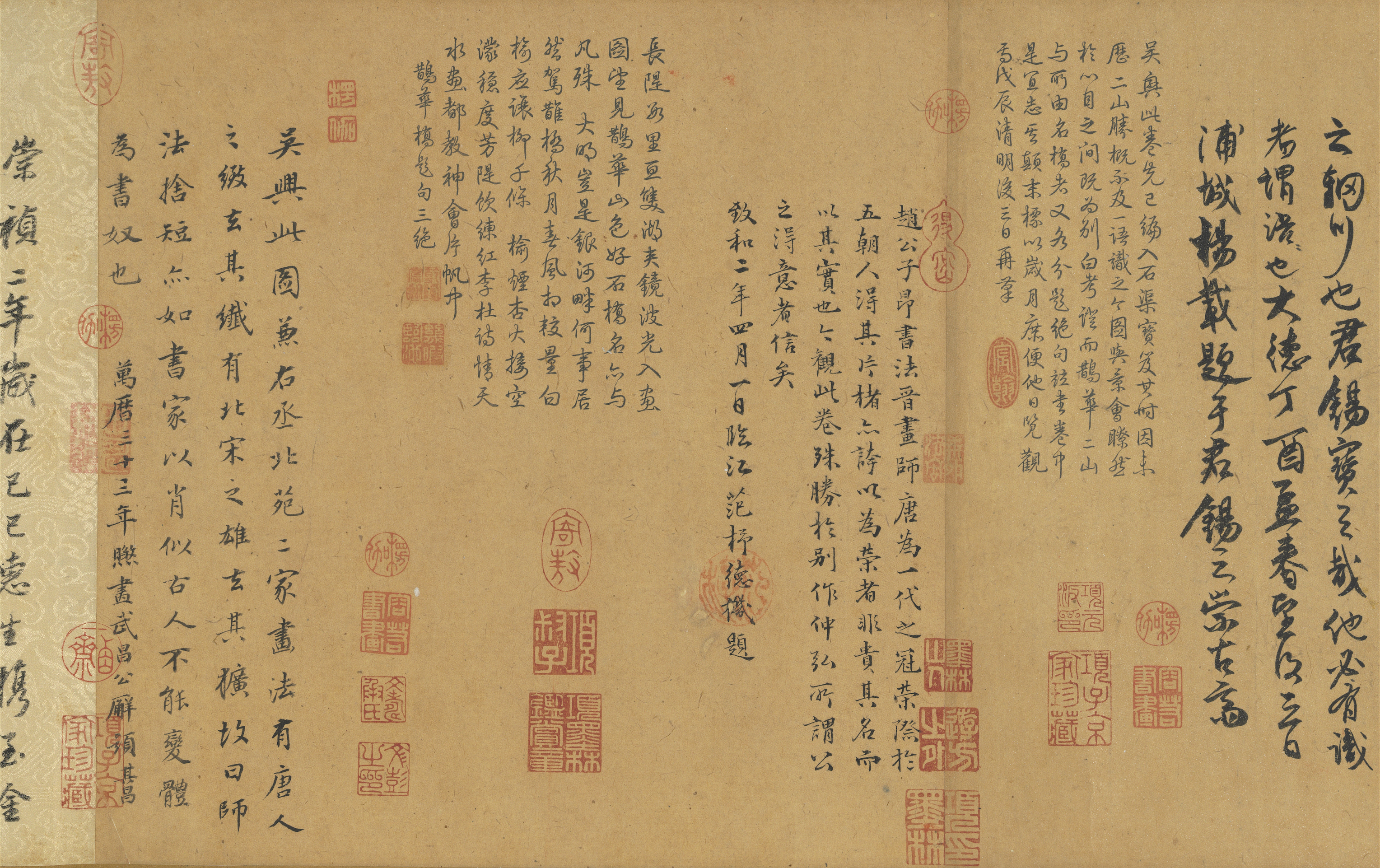

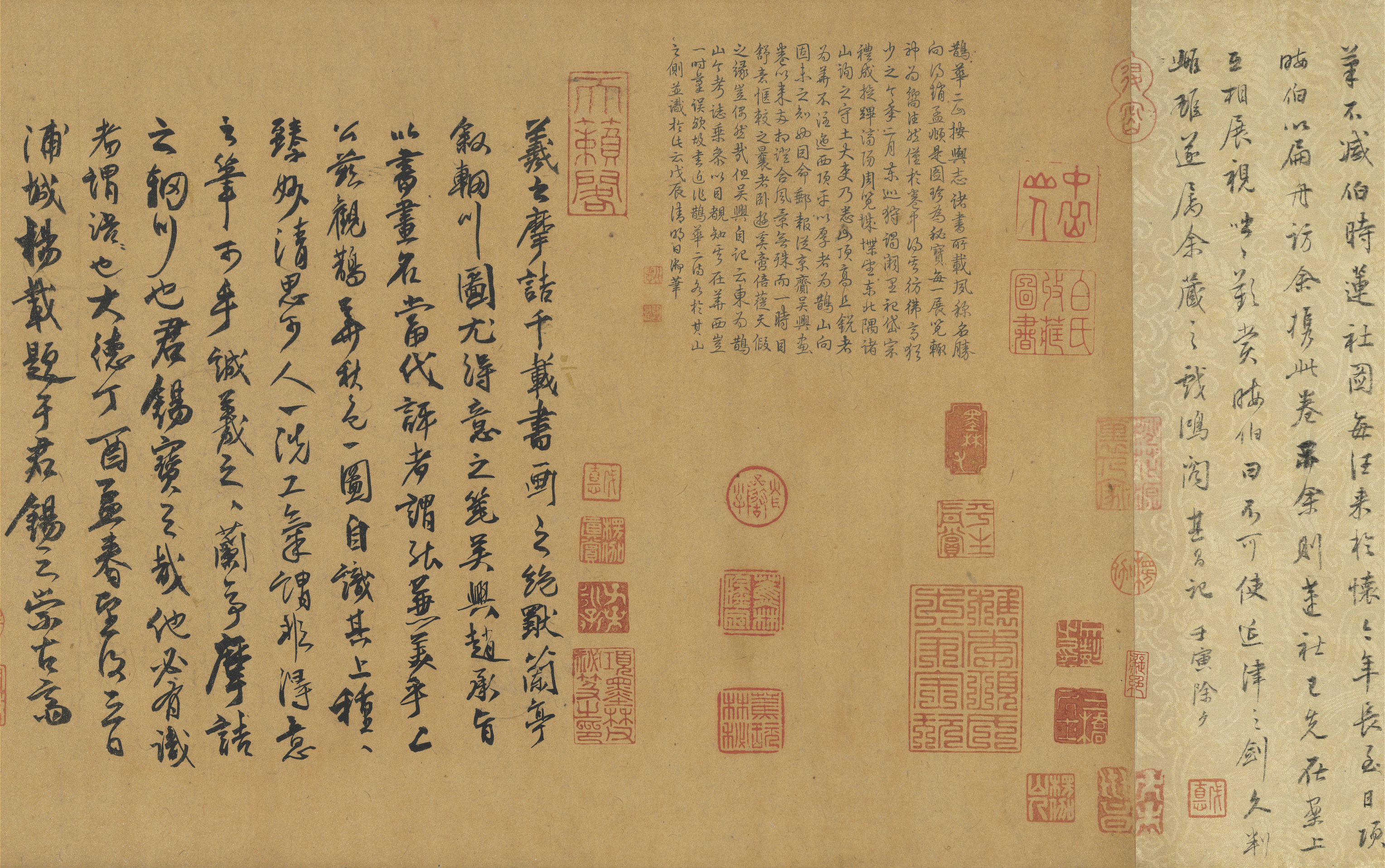

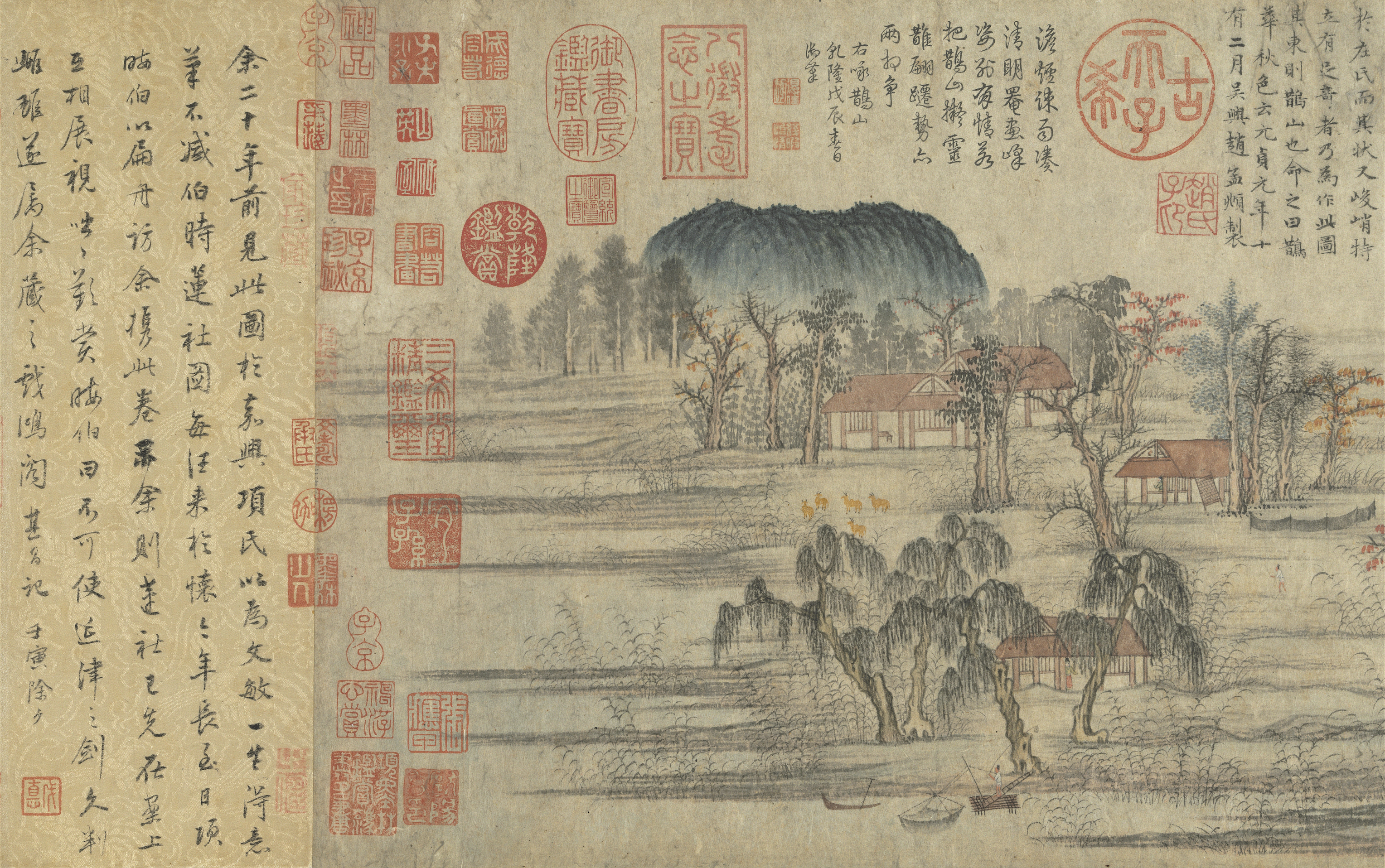

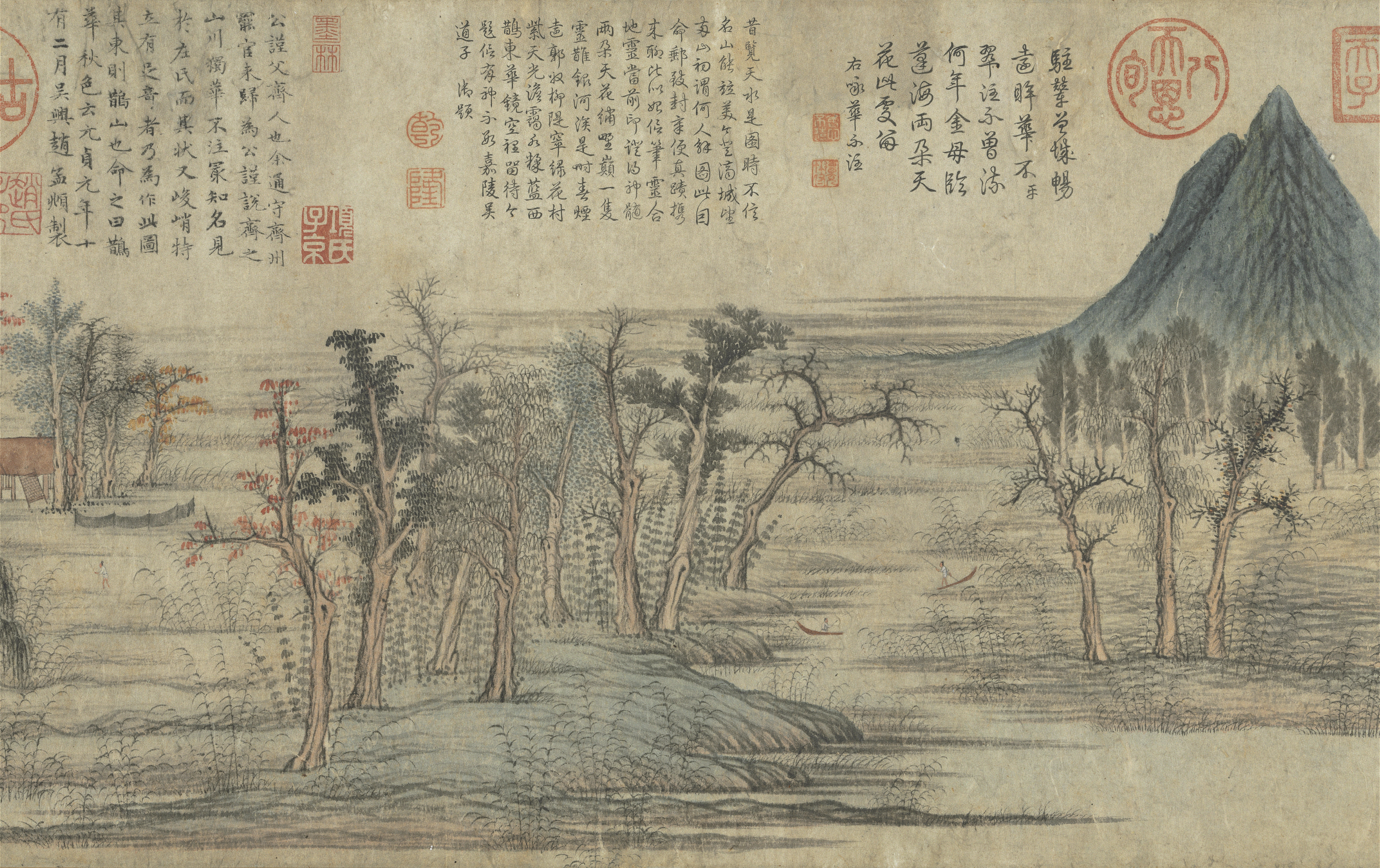

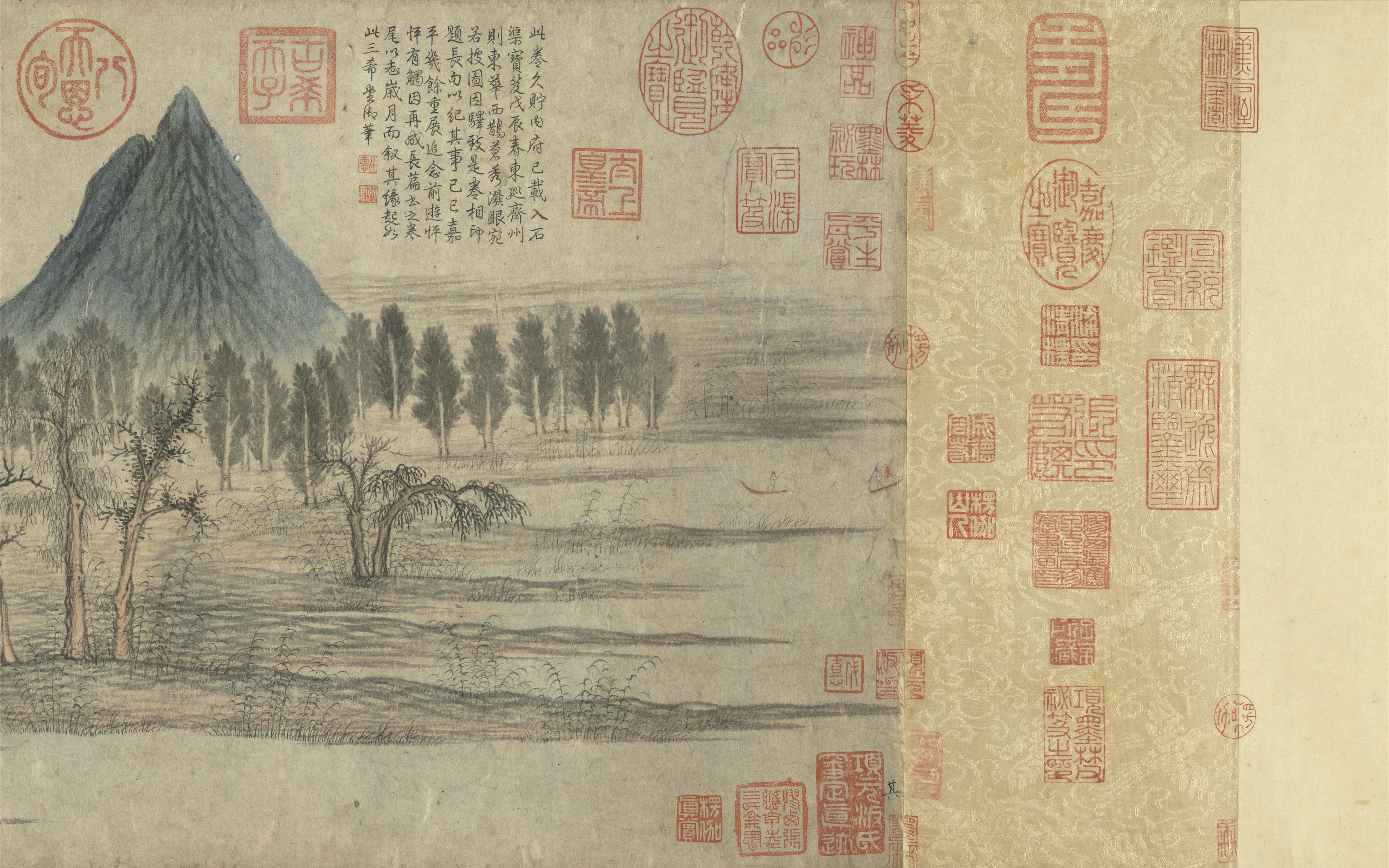

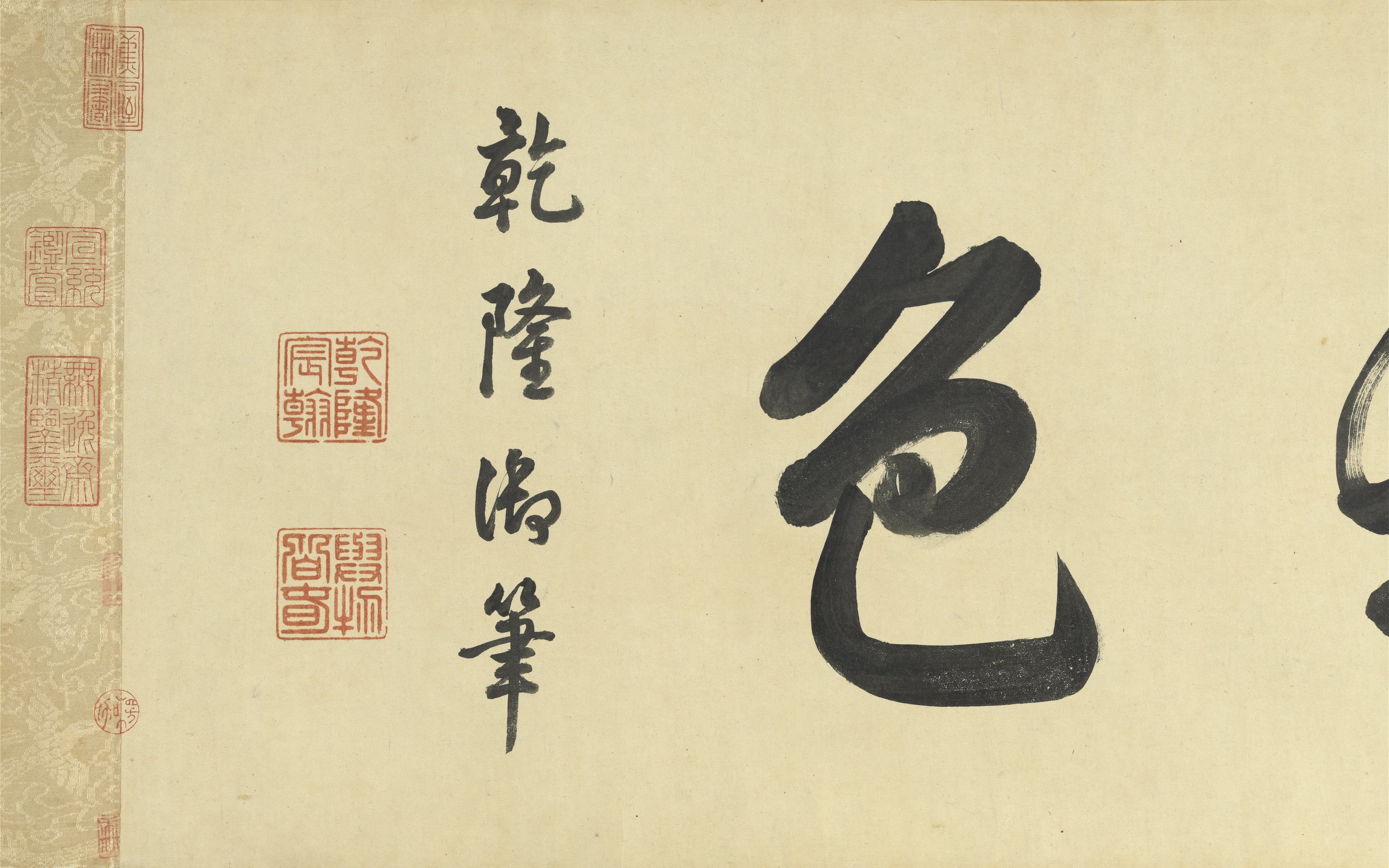

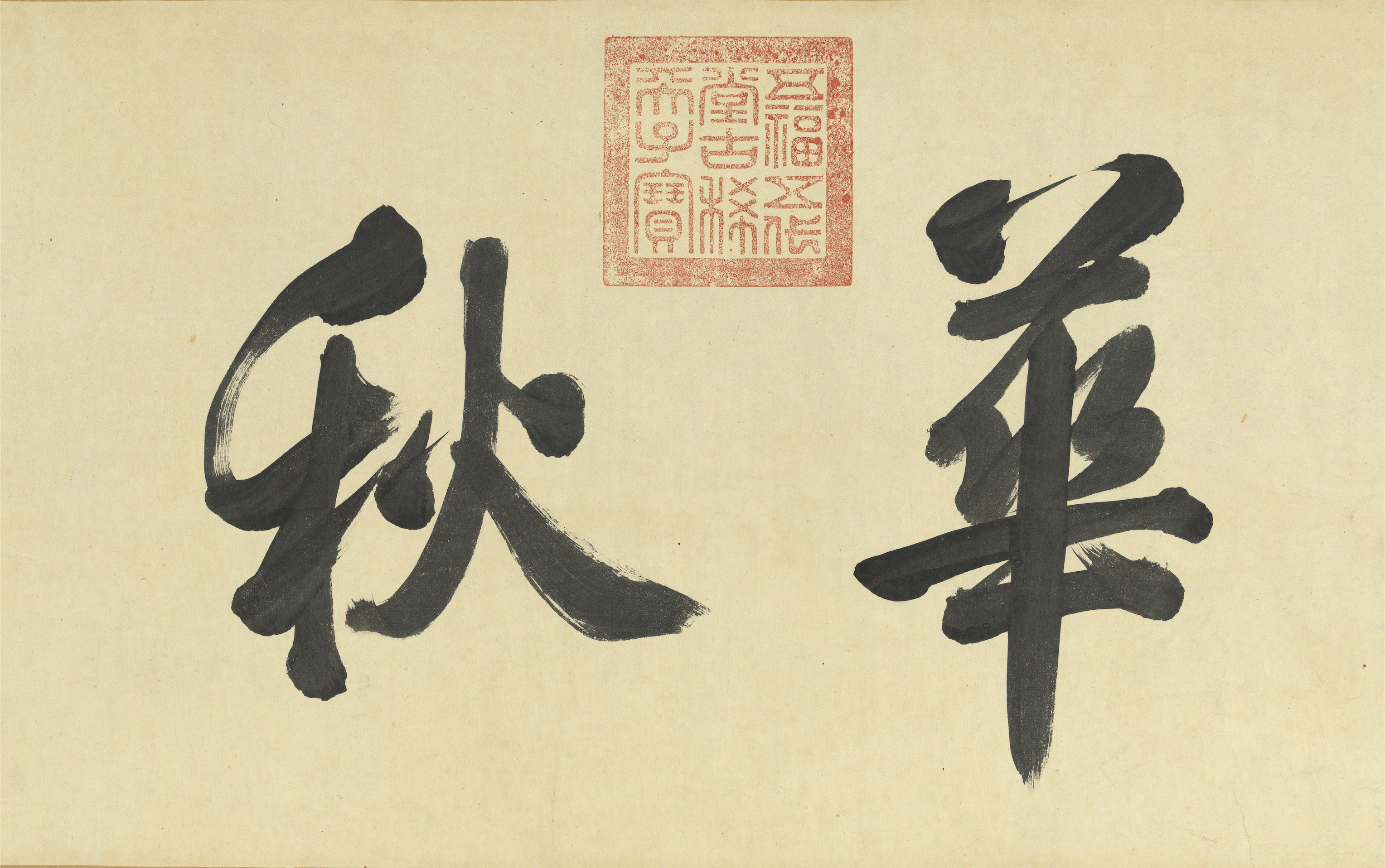

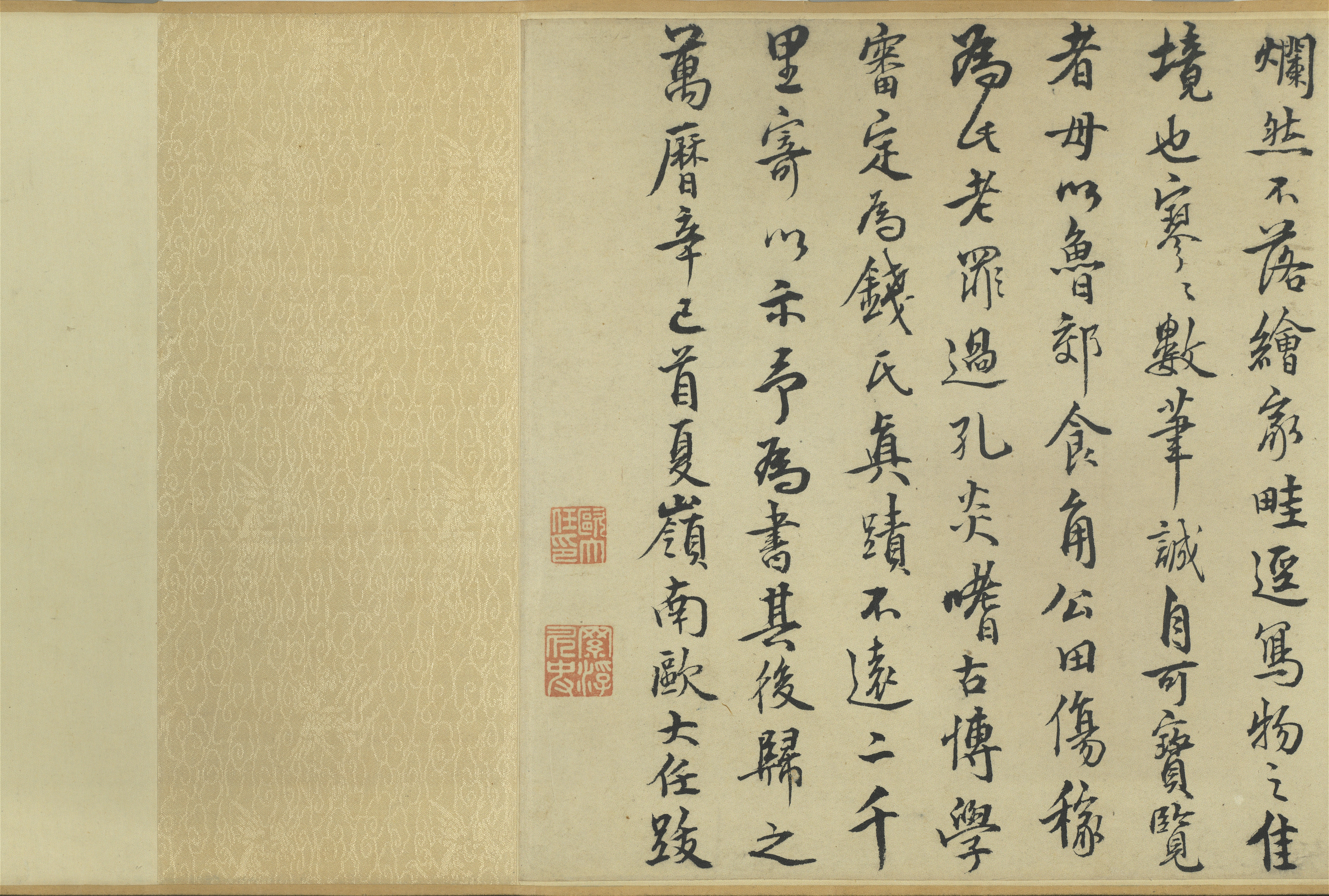

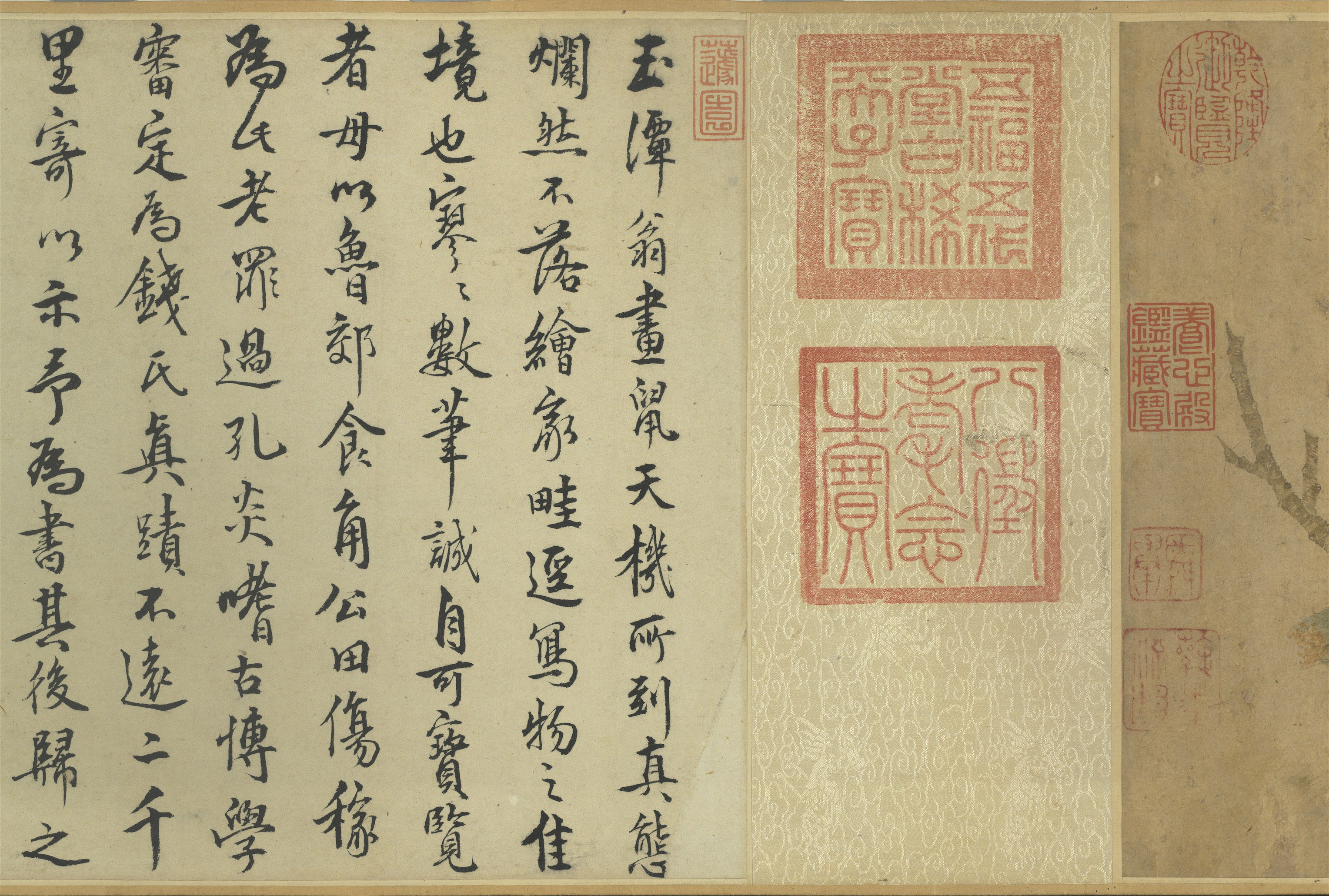

Autumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua Mountains (Open)

Autumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua MountainsAutumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua Mountains (Close)Autumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua Mountains

Autumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua MountainsAutumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua Mountains (Close)Autumn Colors on the Qiao and Hua Mountains- Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322), Yuan dynasty

- Handscroll, ink and colors on paper, 28.4 x 93.2 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in September 2011 as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/10/04-11/14

-

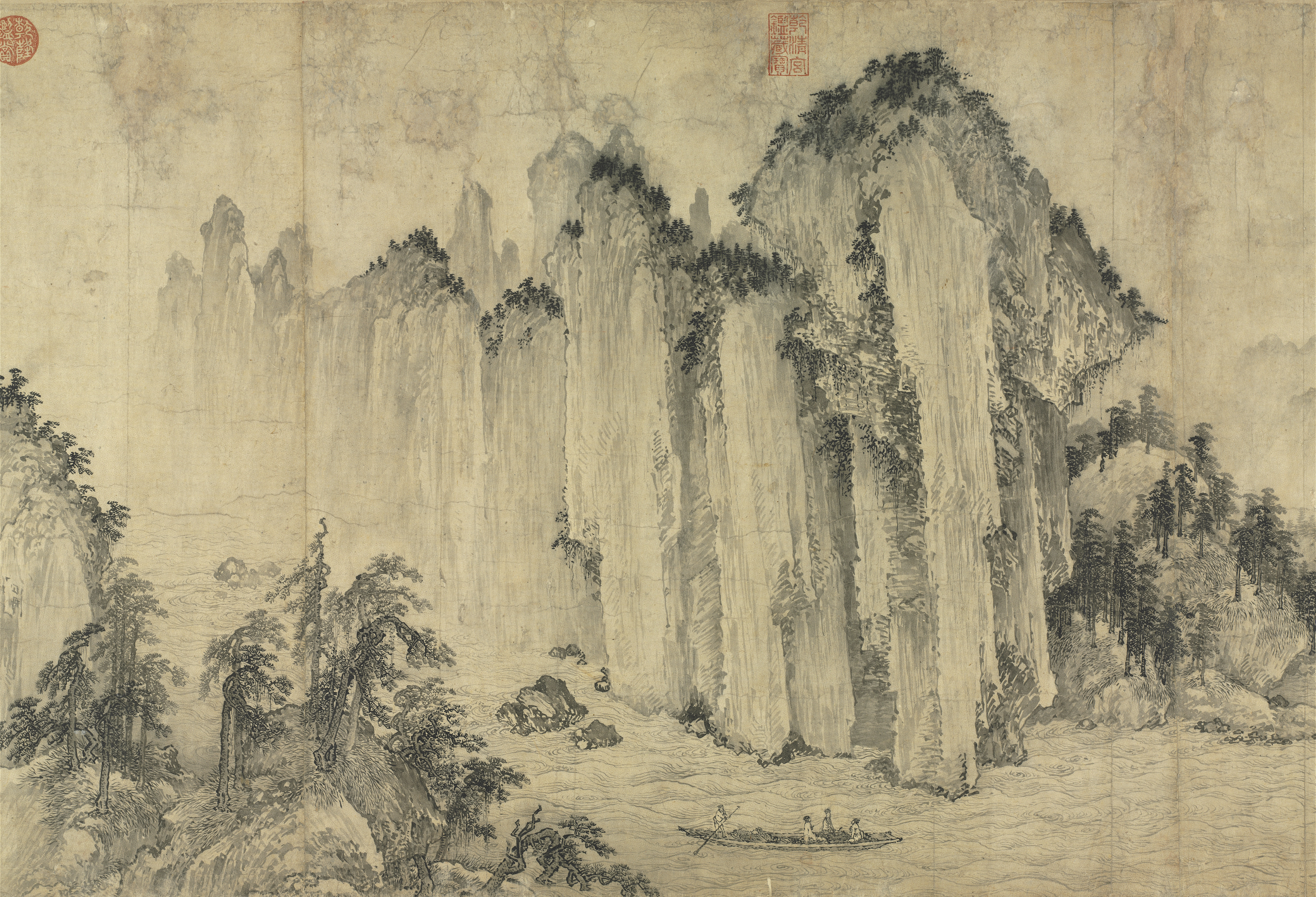

The Red Cliff (Open)

The Red CliffThe Red Cliff (Close)The Red Cliff

The Red CliffThe Red Cliff (Close)The Red Cliff- Wu Yuanzhi (fl. 1149-1189), Jin dynasty

- Handscroll, ink on paper, 50.8 x 136.4 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in April 2011 as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/11/15-12/25

-

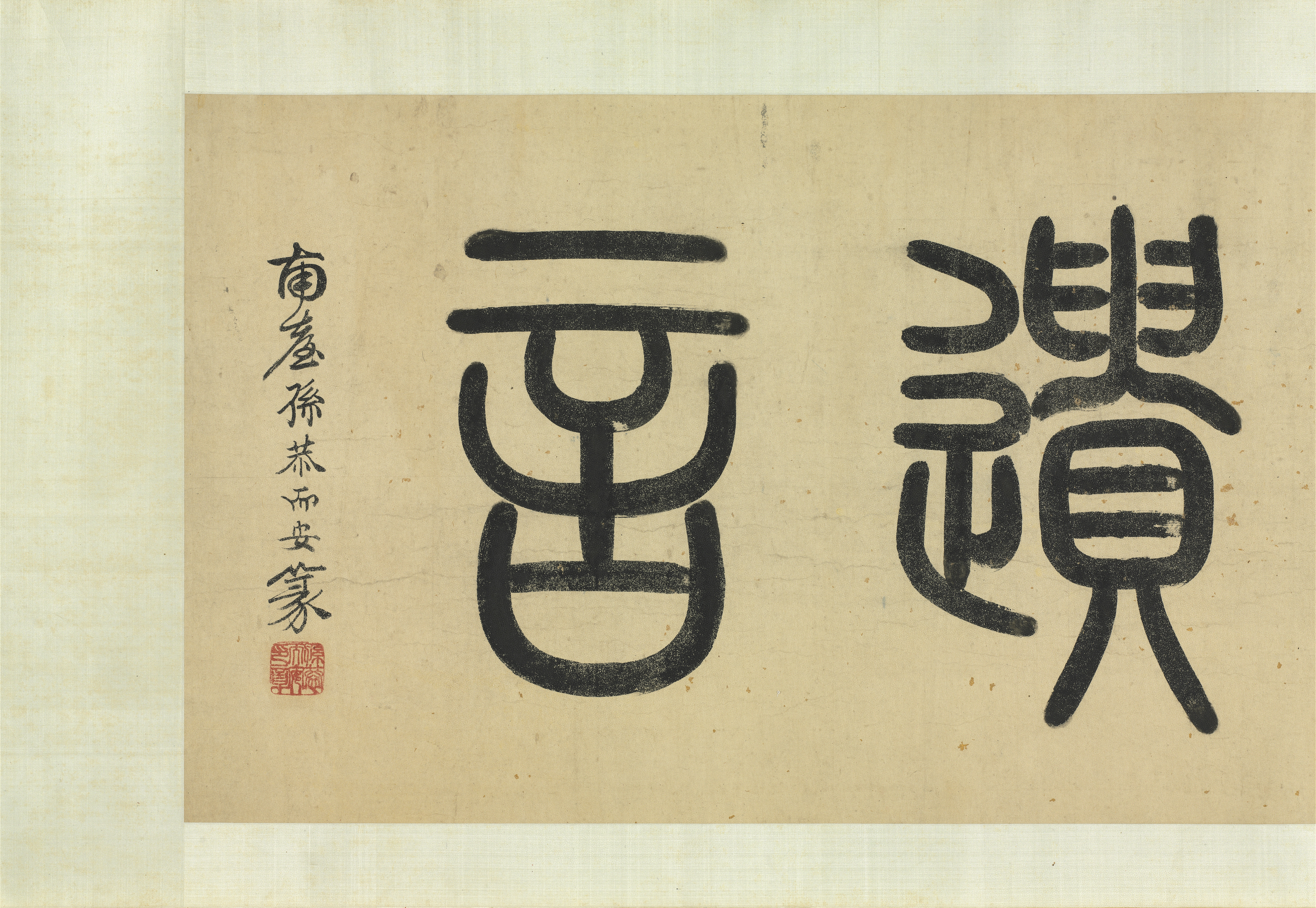

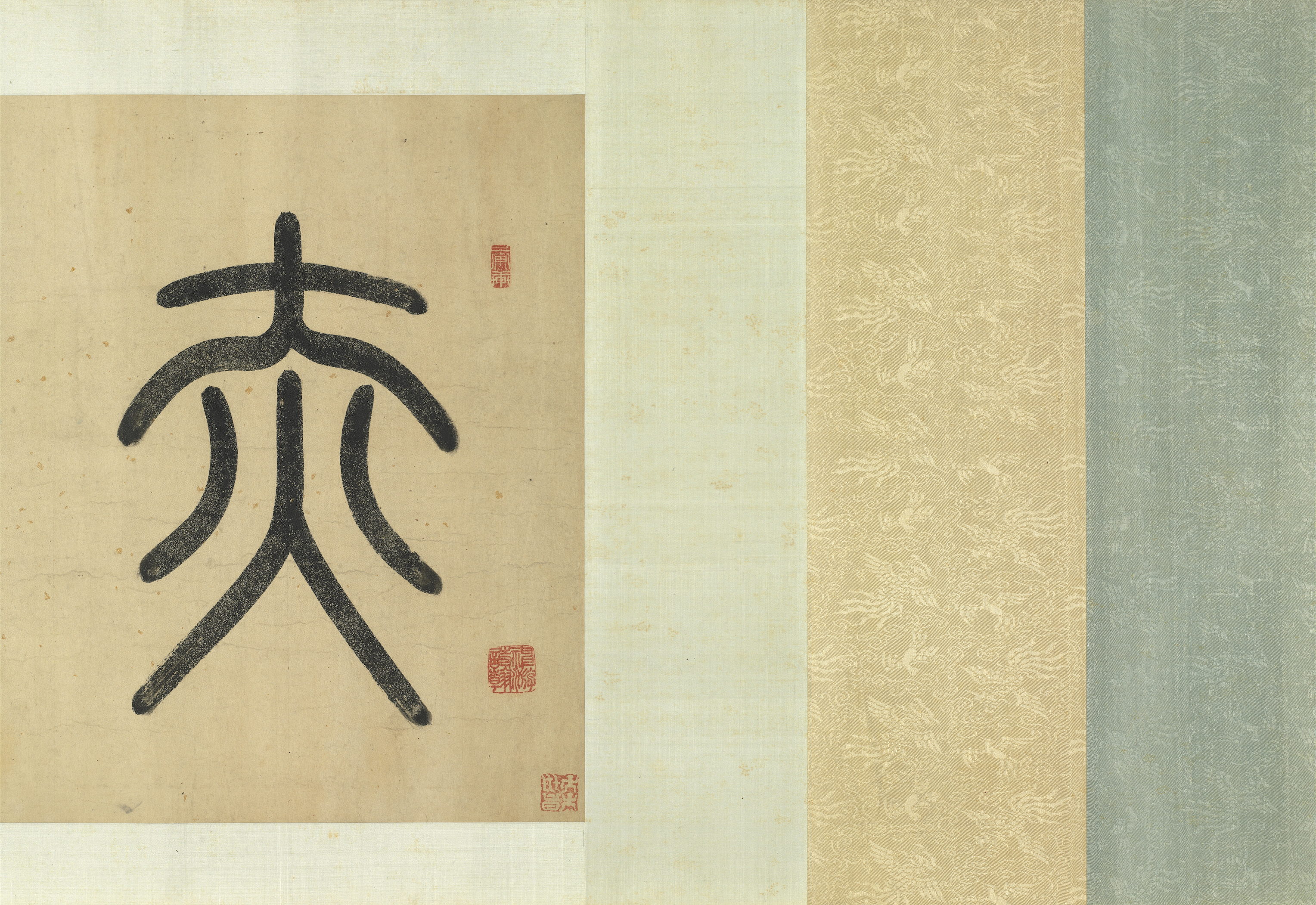

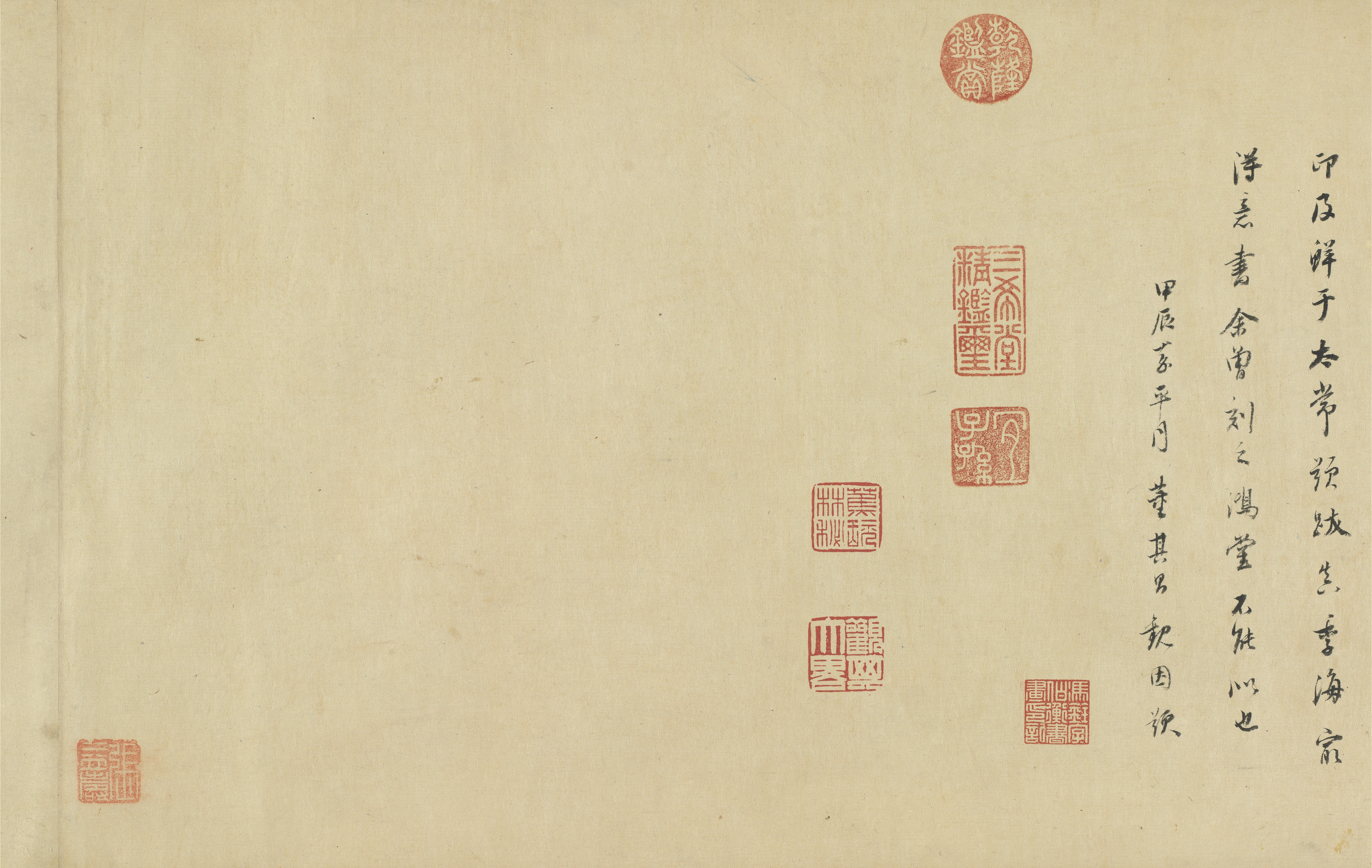

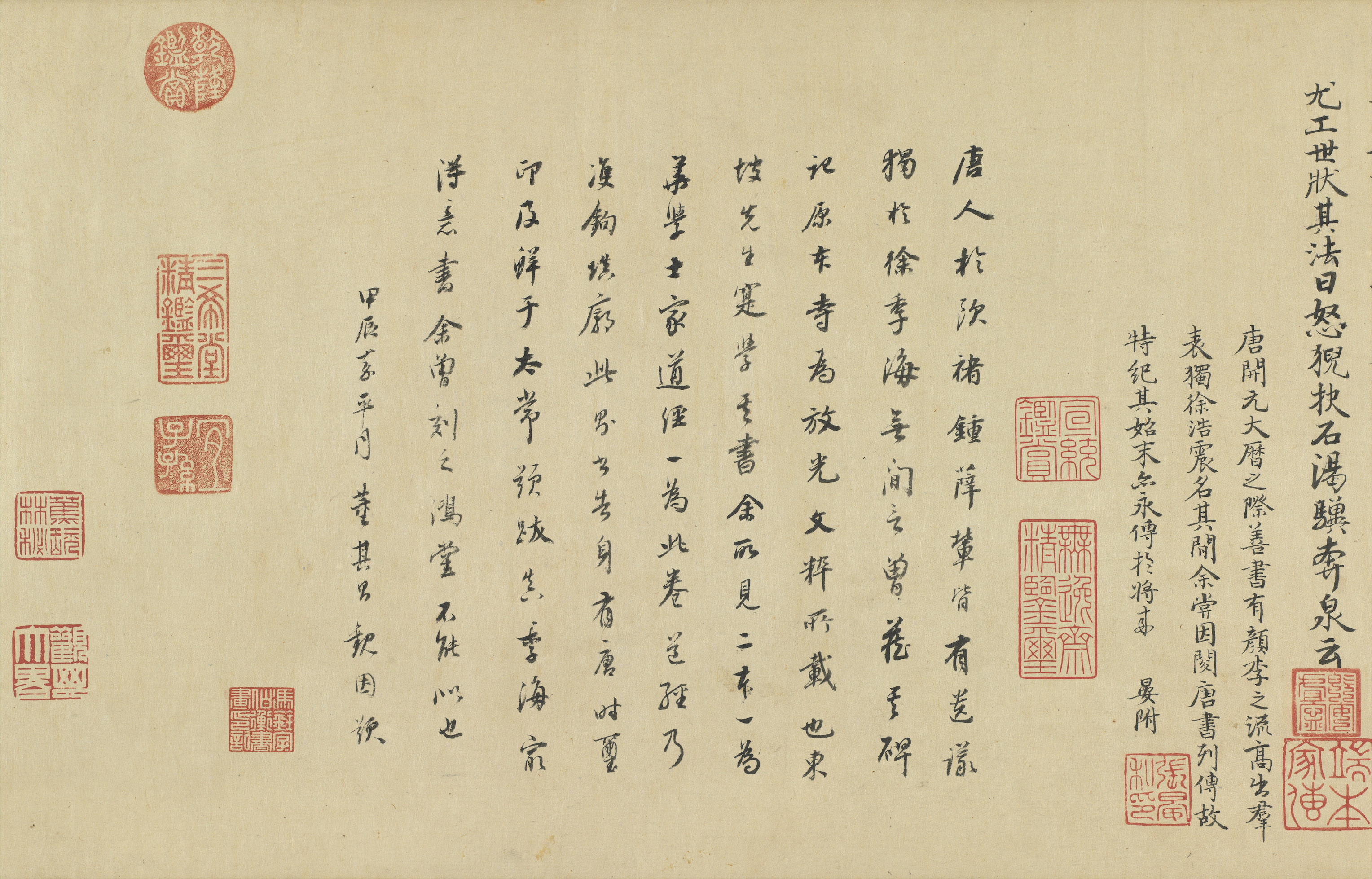

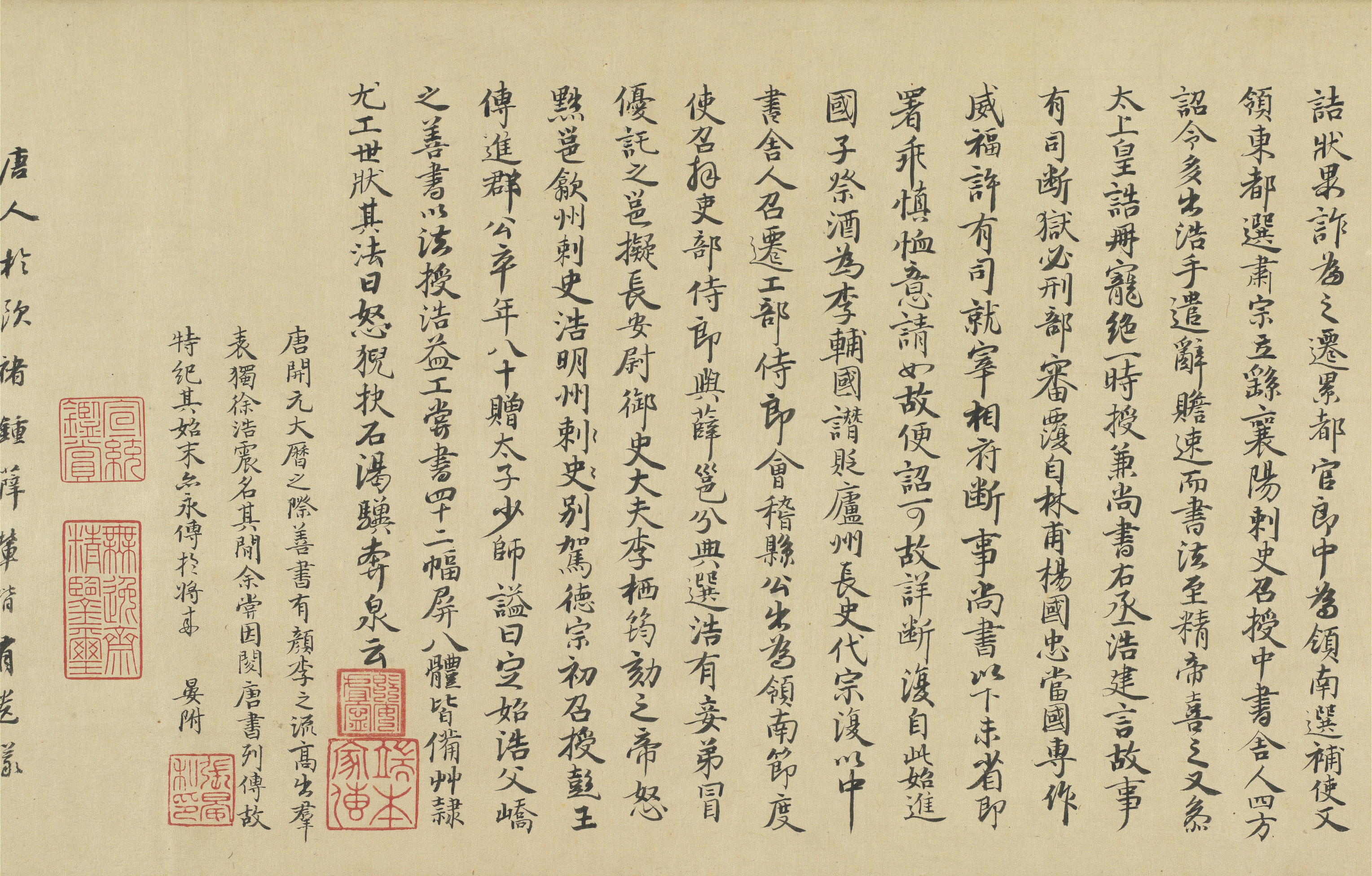

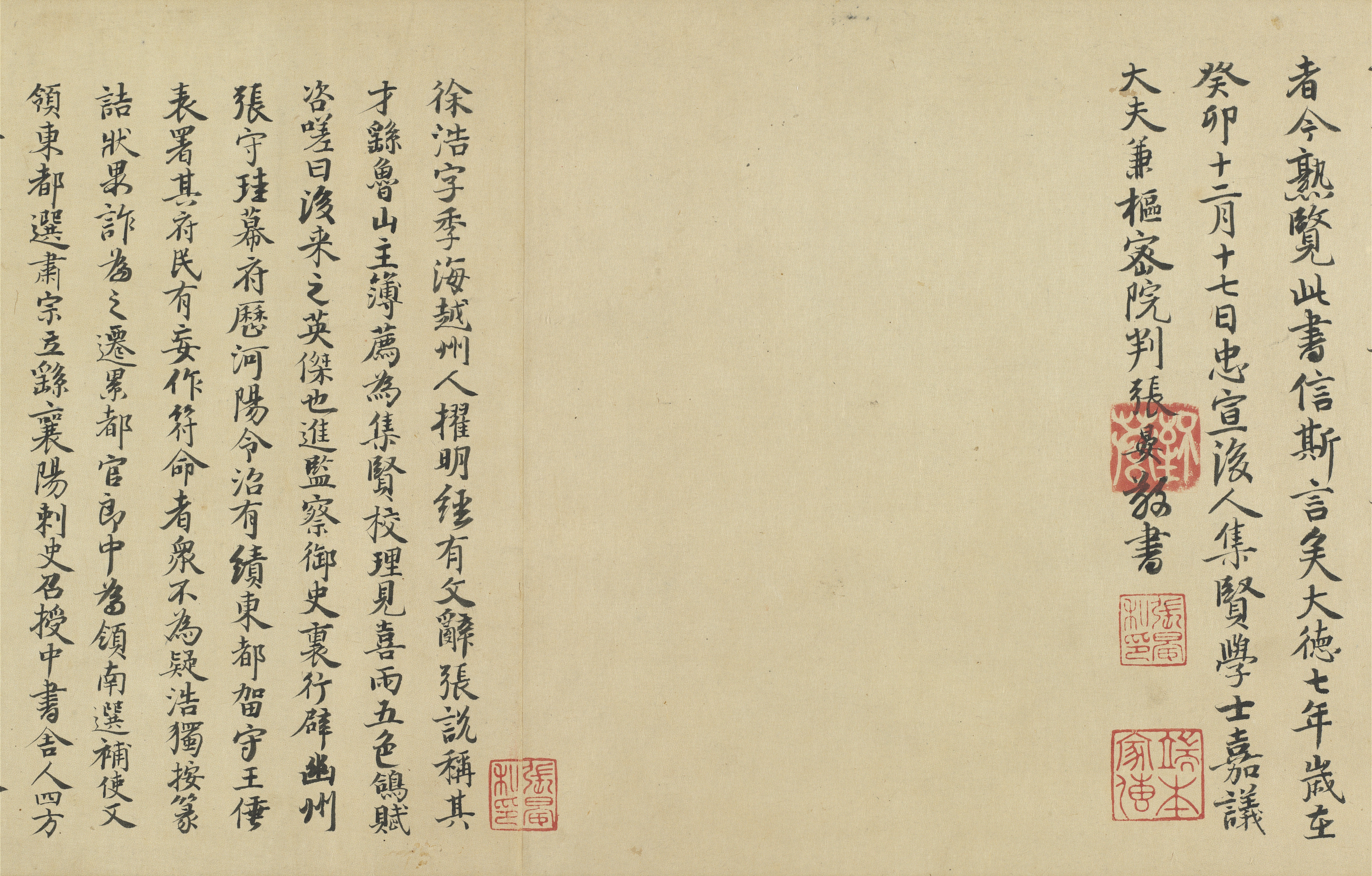

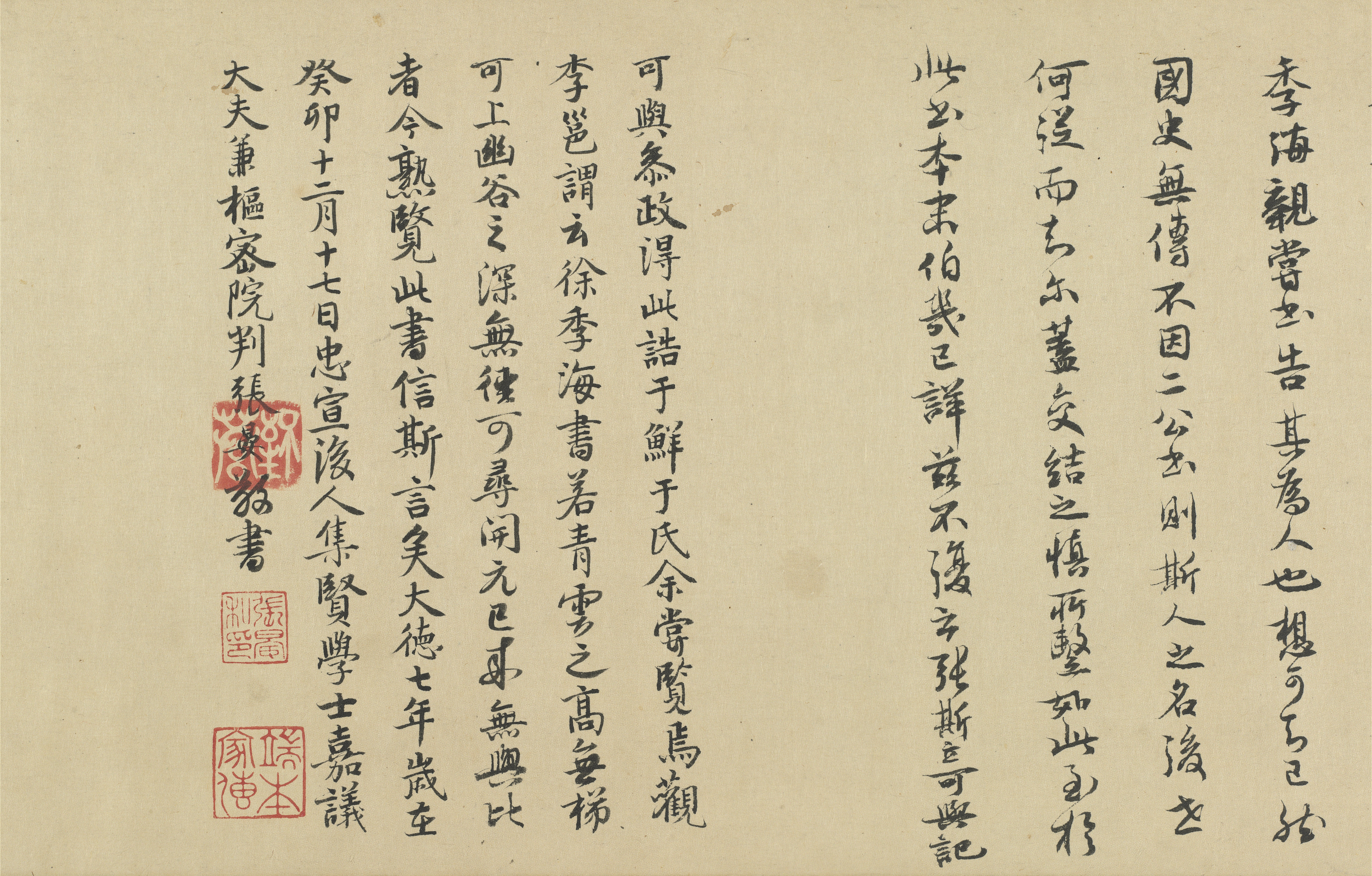

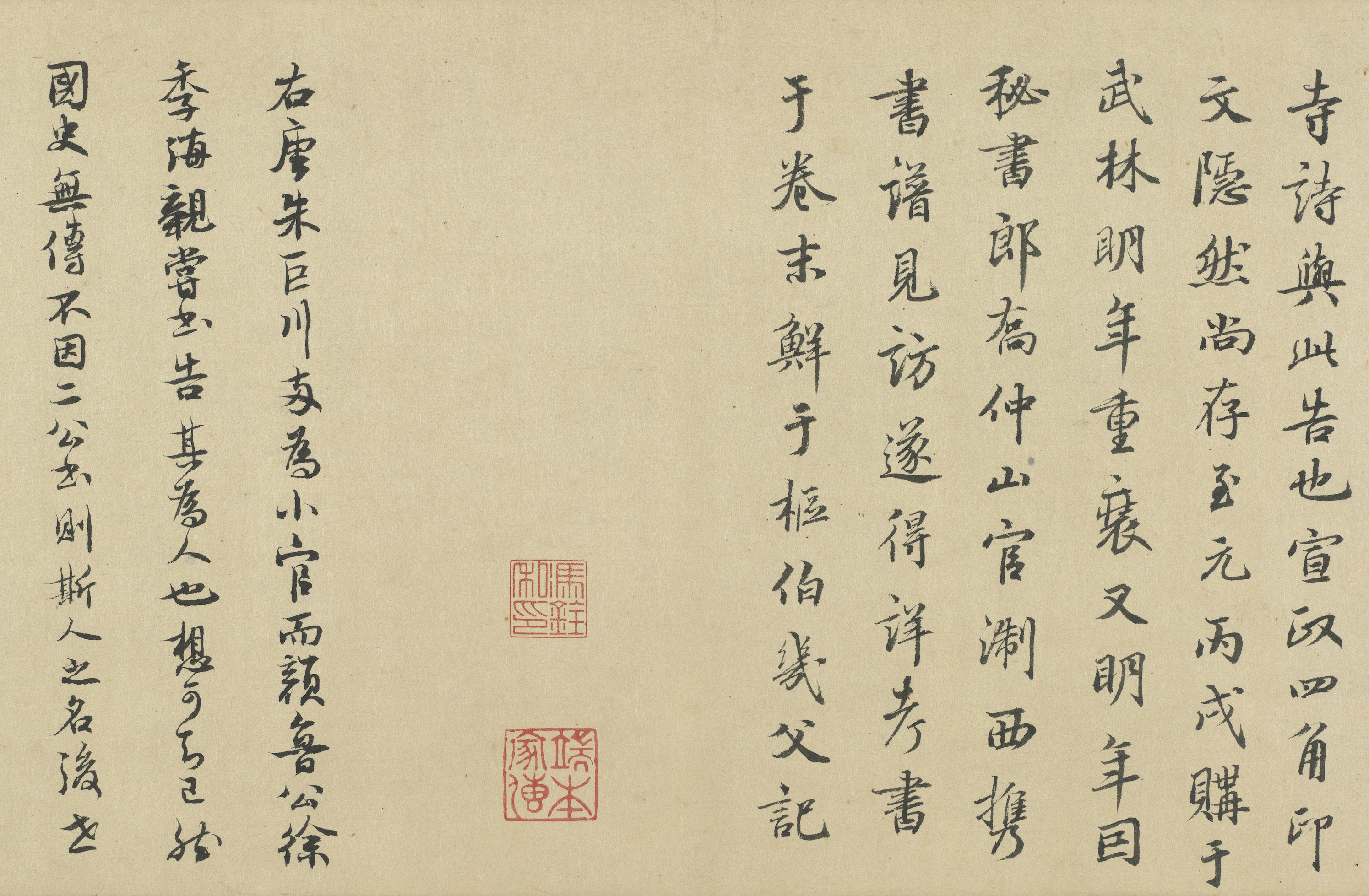

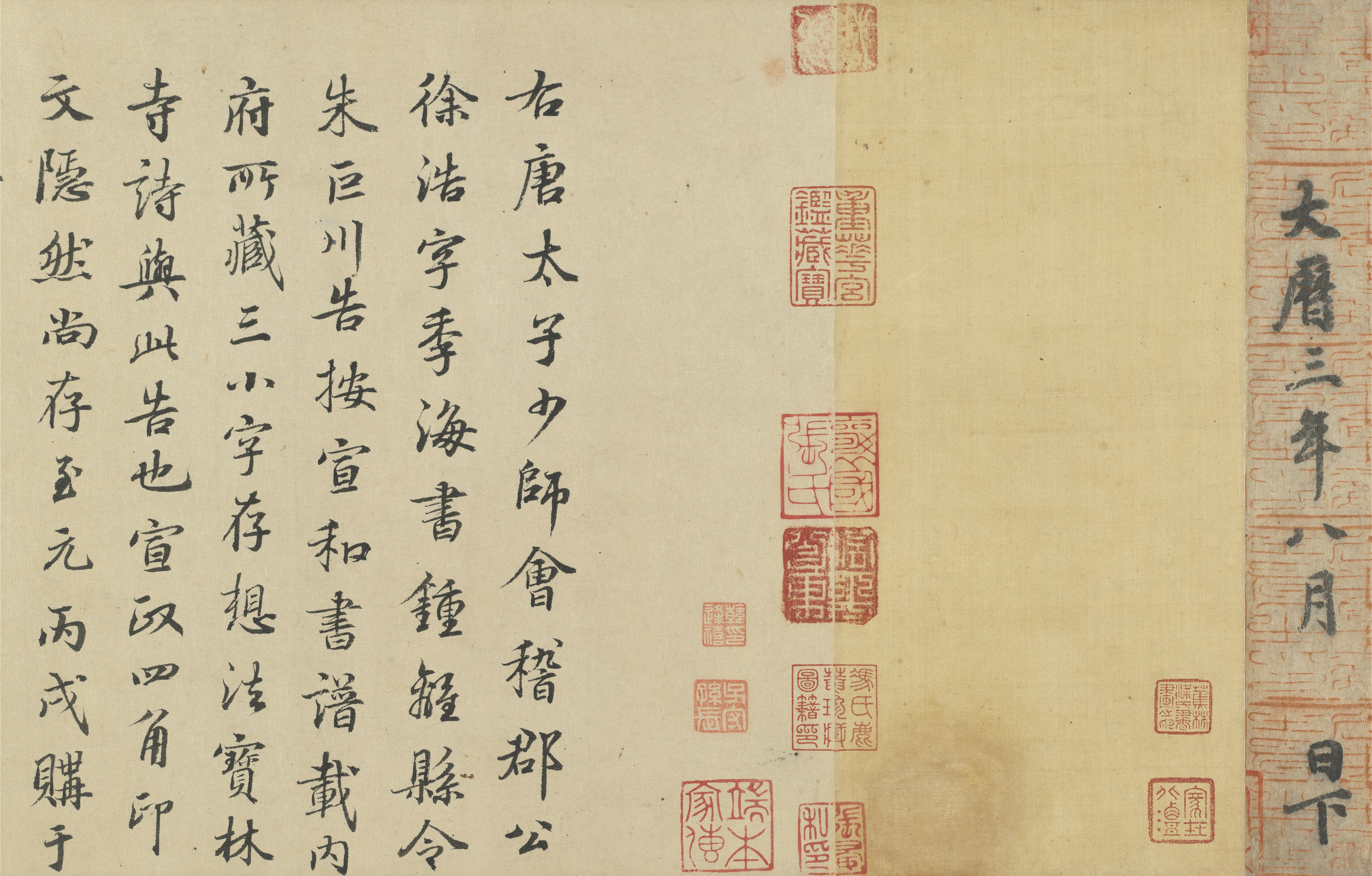

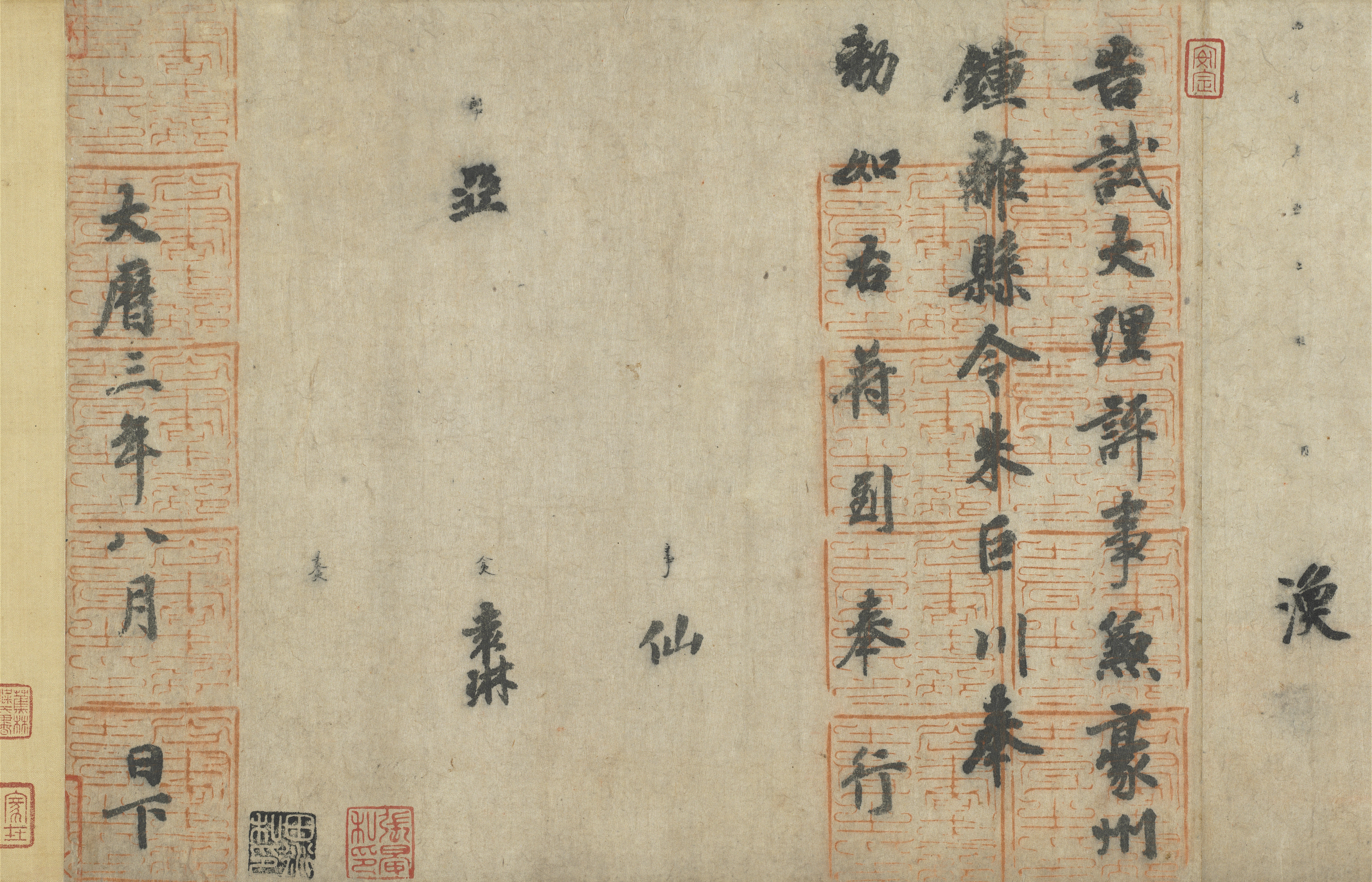

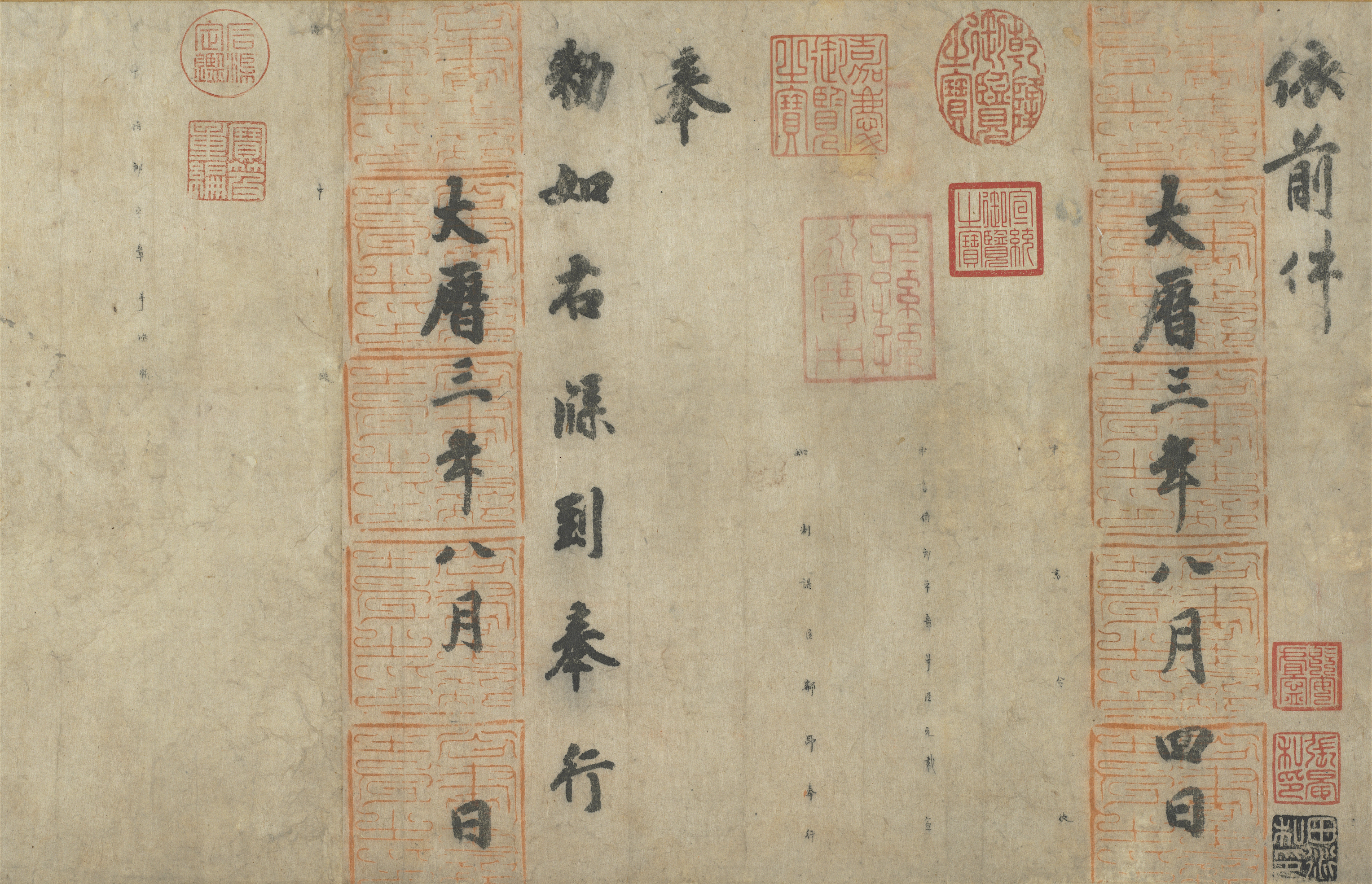

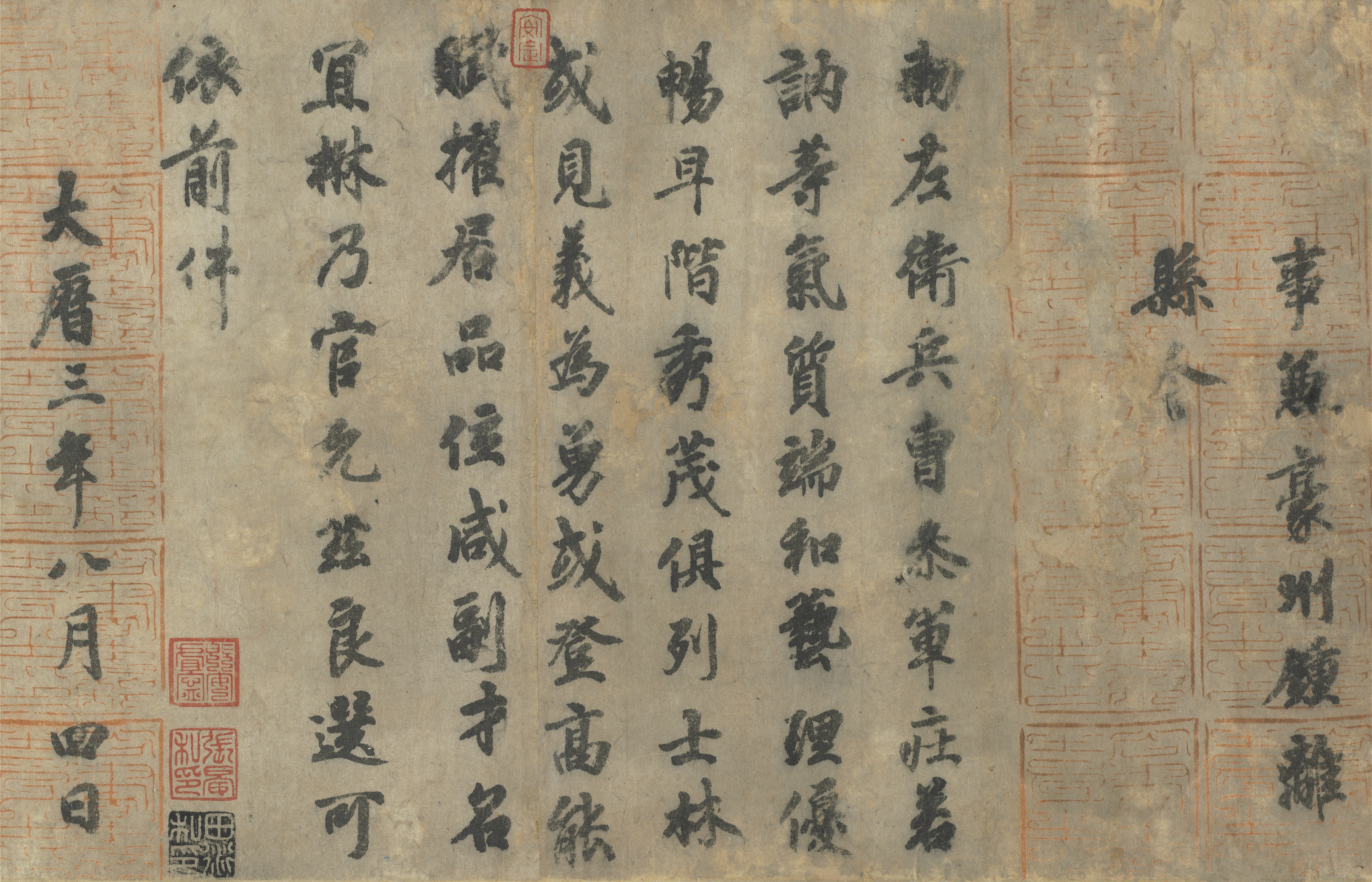

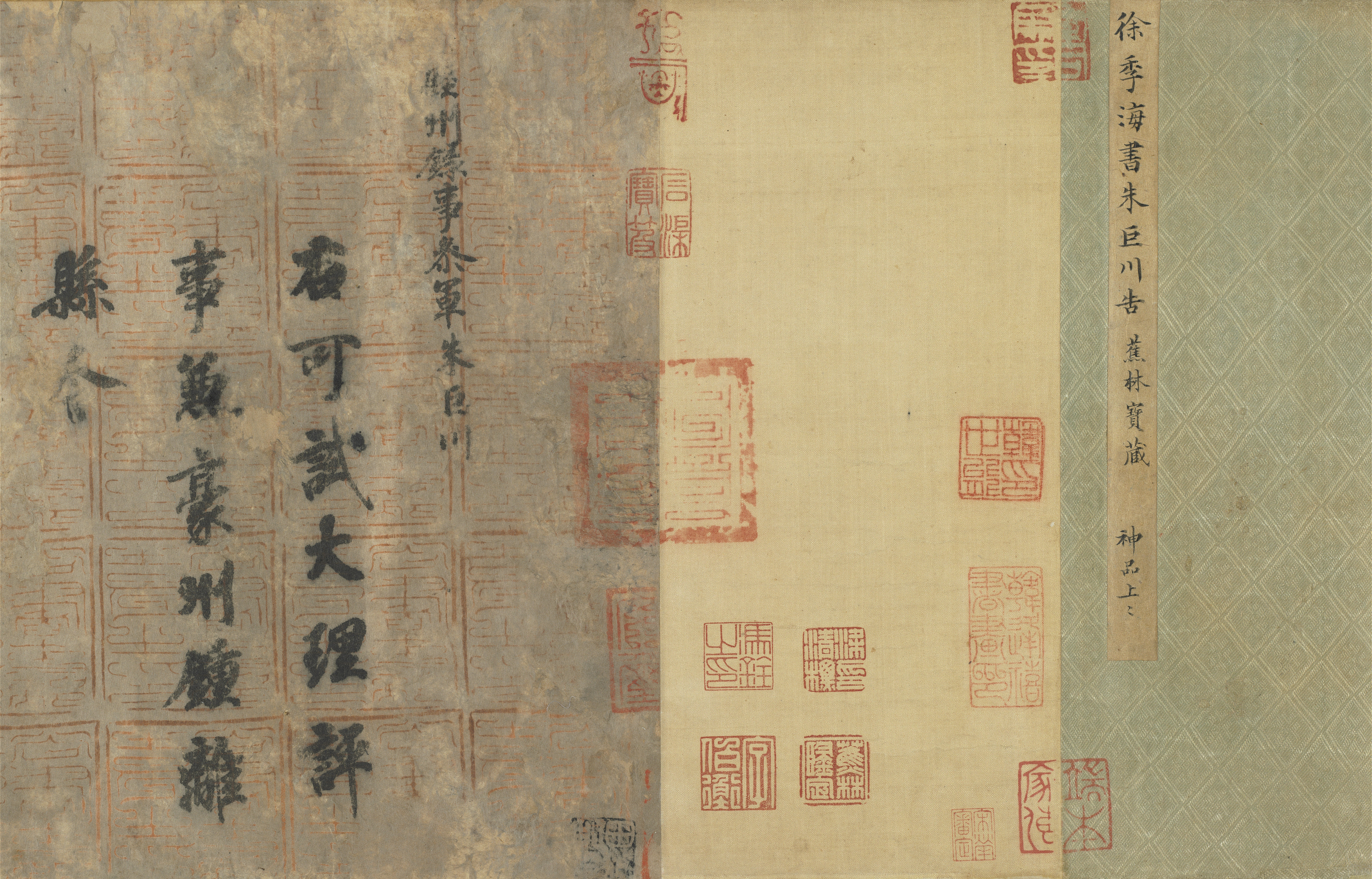

Certificate for Zhu Juchuan (Open)

Certificate for Zhu JuchuanCertificate for Zhu Juchuan (Close)Certificate for Zhu Juchuan

Certificate for Zhu JuchuanCertificate for Zhu Juchuan (Close)Certificate for Zhu Juchuan- Xu Hao (703-782), Tang dynasty

- Handscroll, ink on paper, 27 x 185.8 cm

- Provisionally classified by the National Palace Museum as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/11/15-12/25

-

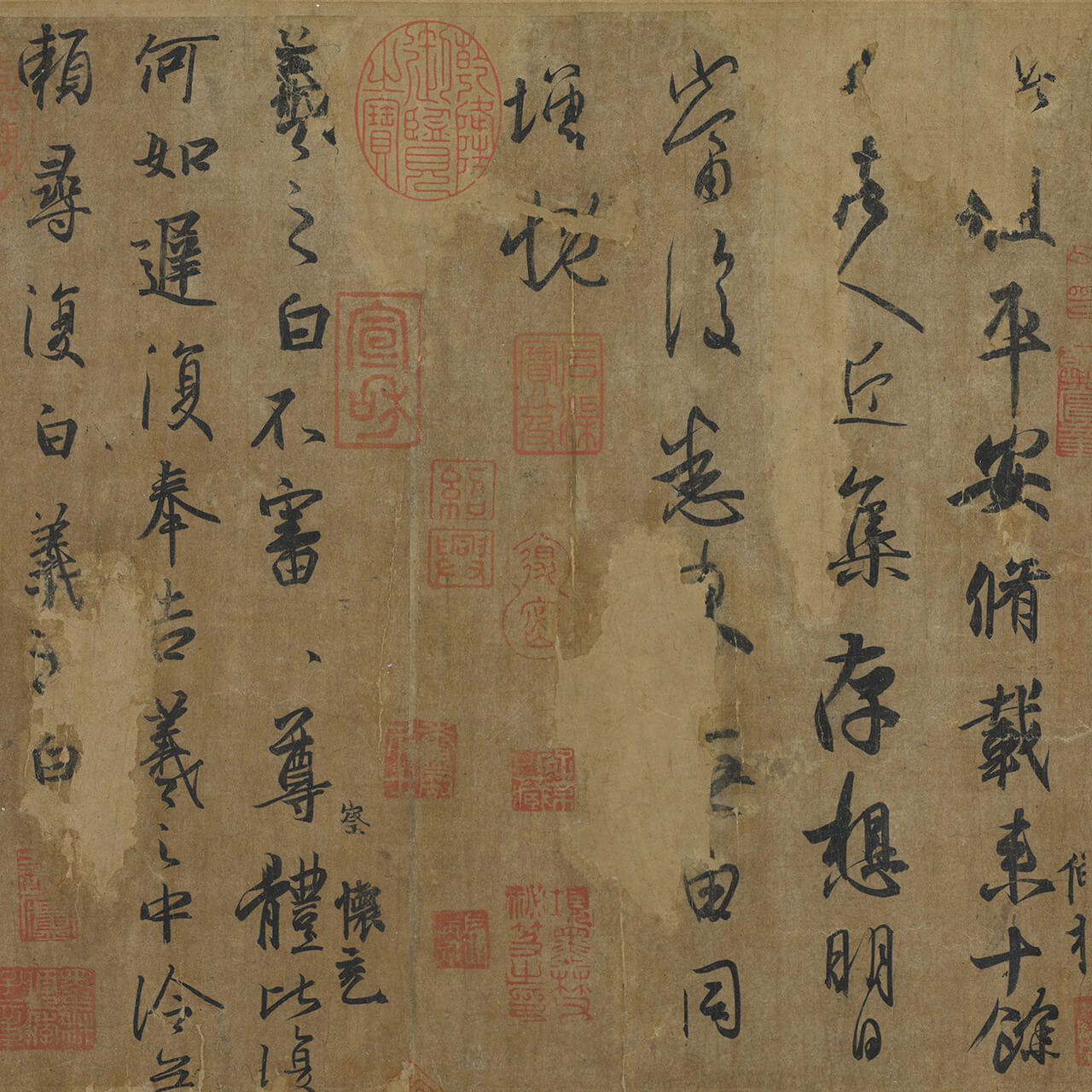

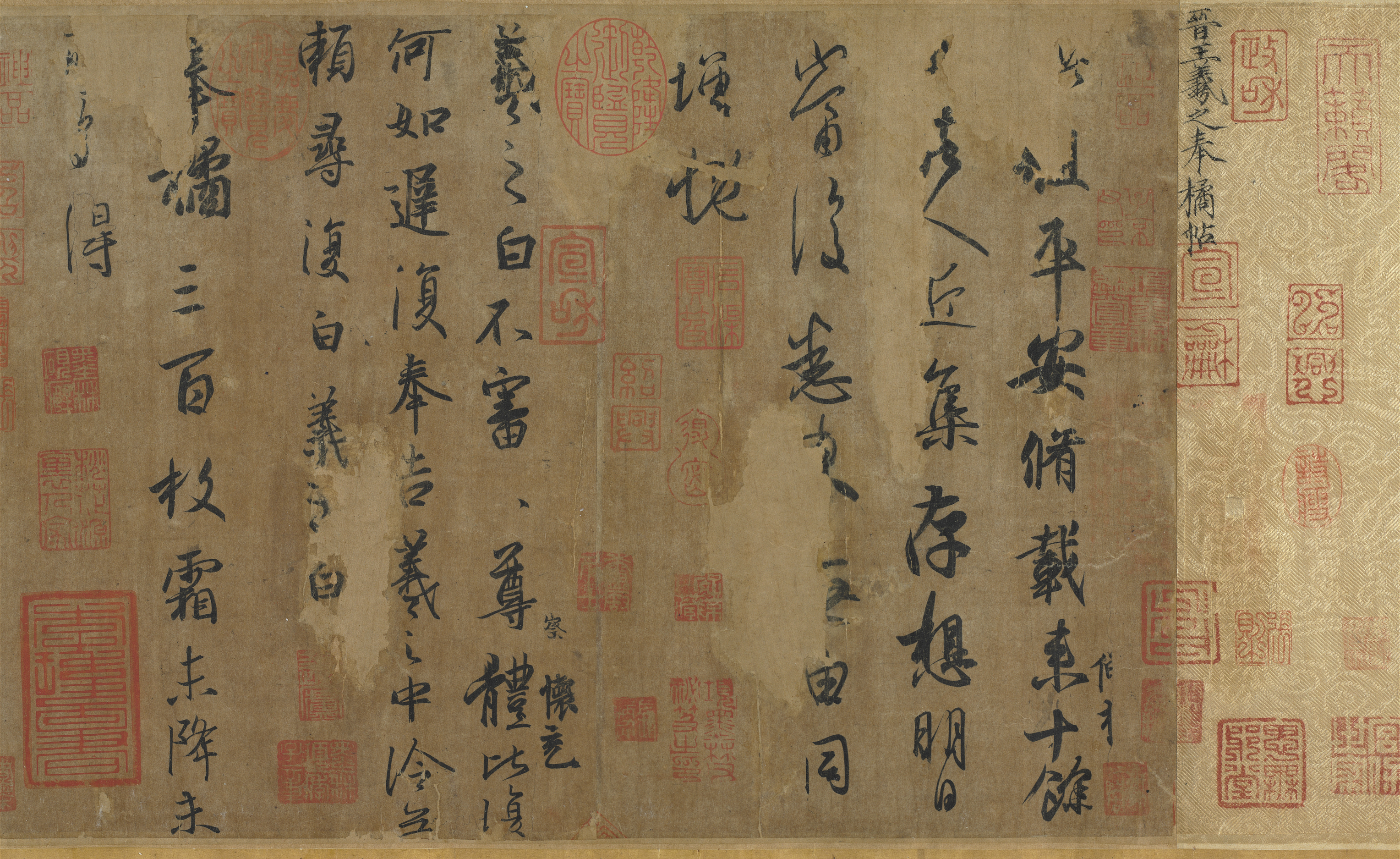

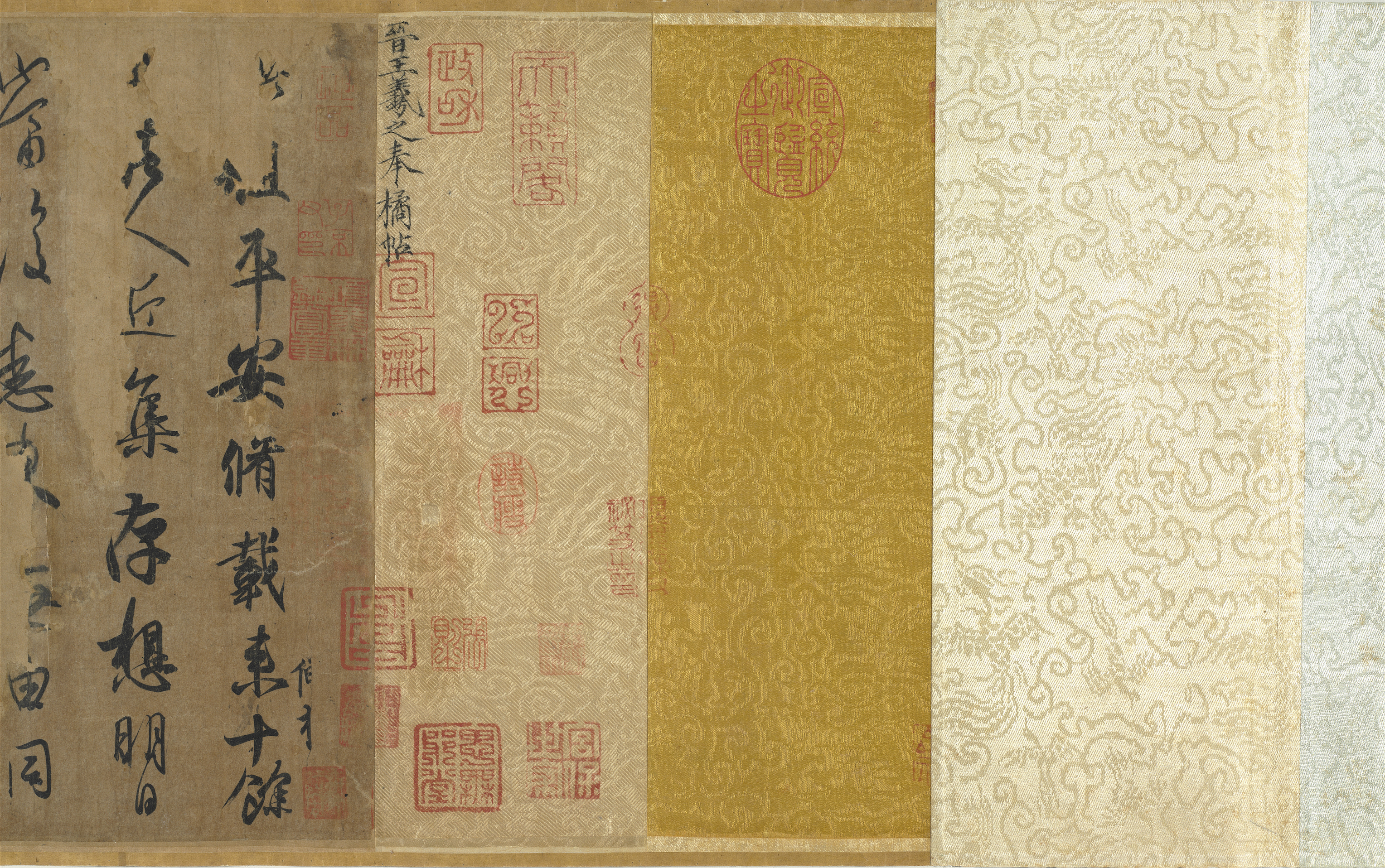

Three Passages: Ping'an, Heru, and Fengju (Open)

Three Passages: Ping'an, Heru, and FengjuThree Passages: Ping'an, Heru, and Fengju (Close)Three Passages: Ping'an, Heru, and Fengju

Three Passages: Ping'an, Heru, and FengjuThree Passages: Ping'an, Heru, and Fengju (Close)Three Passages: Ping'an, Heru, and Fengju- Wang Xizhi (303-361), Jin dynasty

- Handscroll, ink on paper, 24.7 x 47.3 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in March 2012 as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/10/04-11/14

-

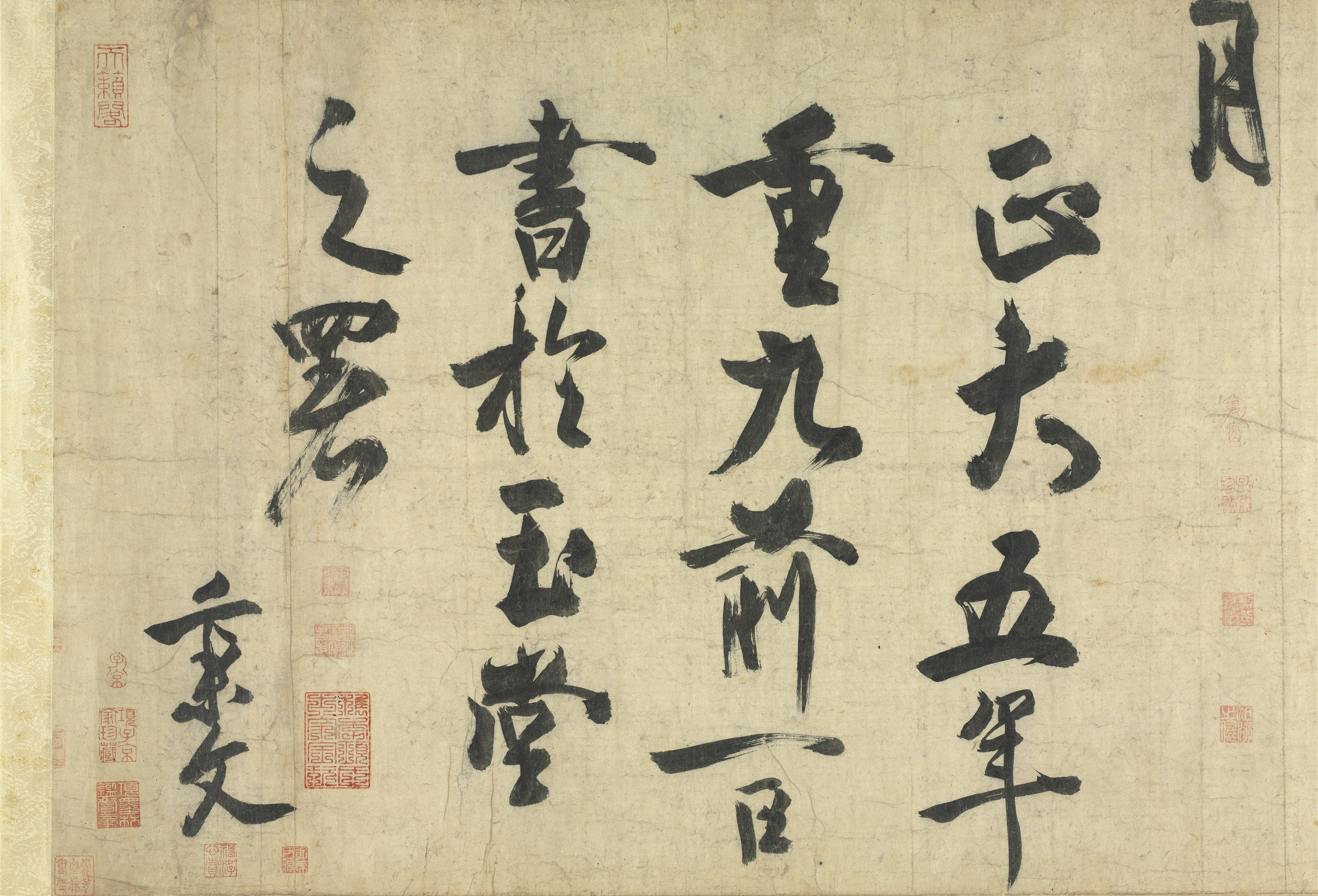

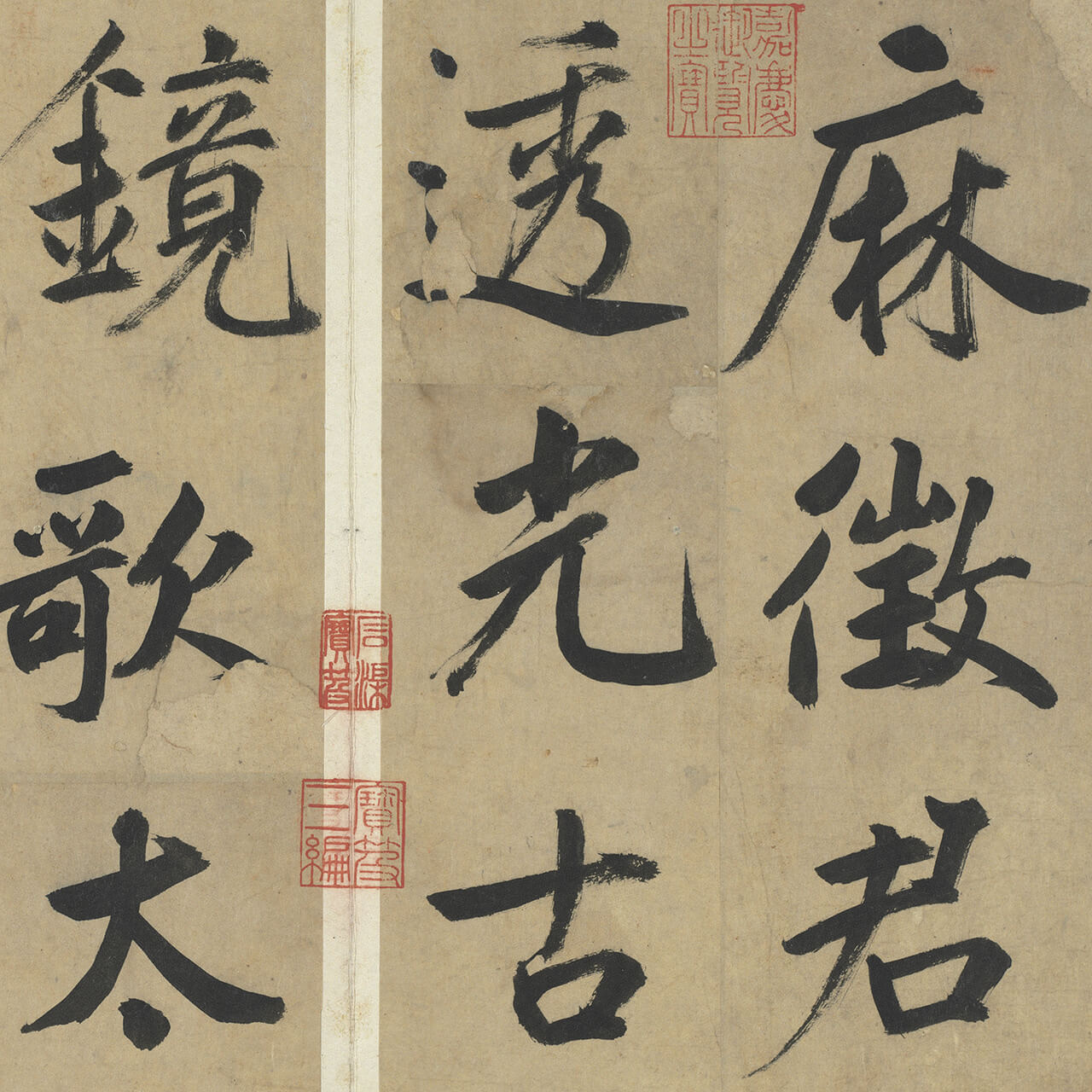

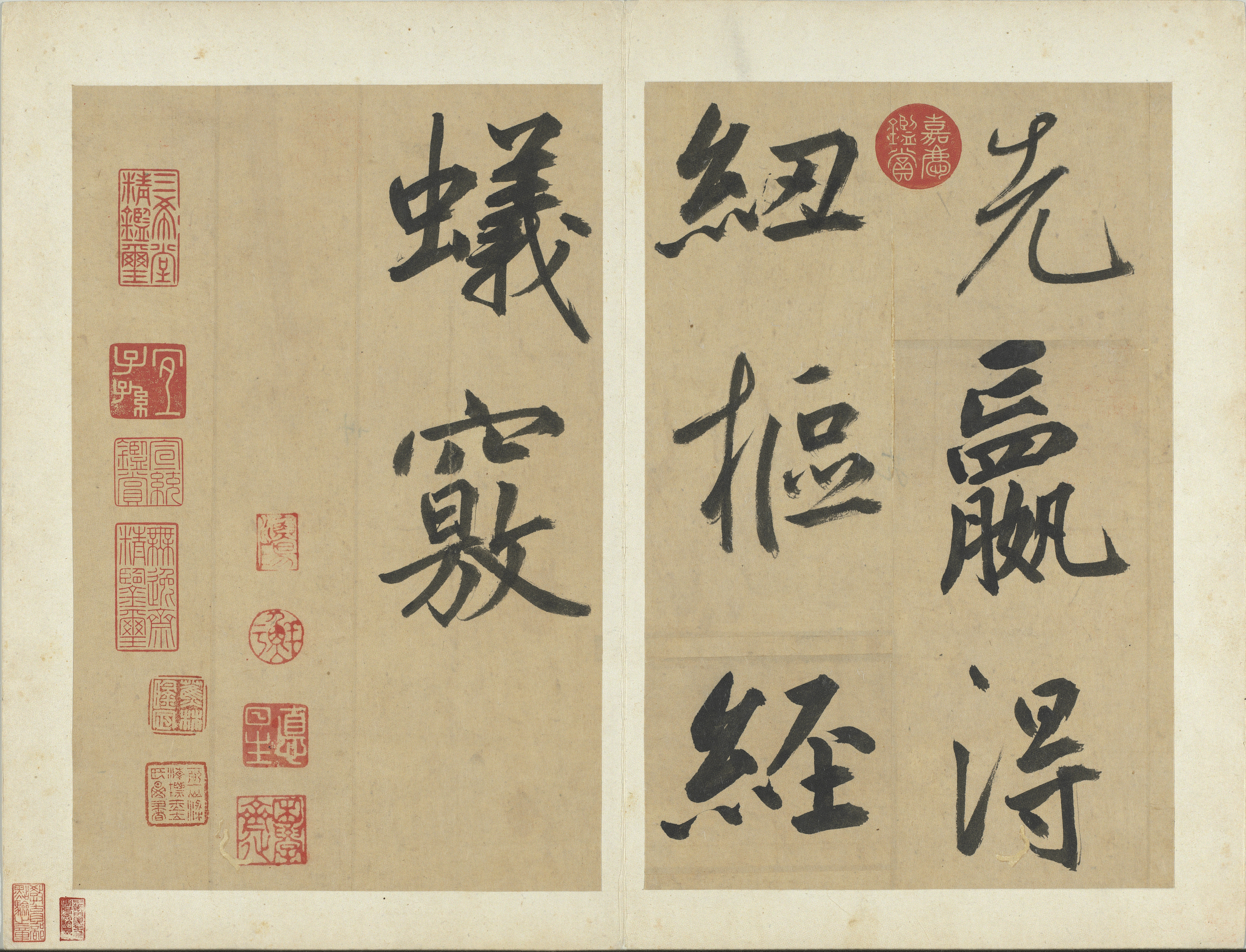

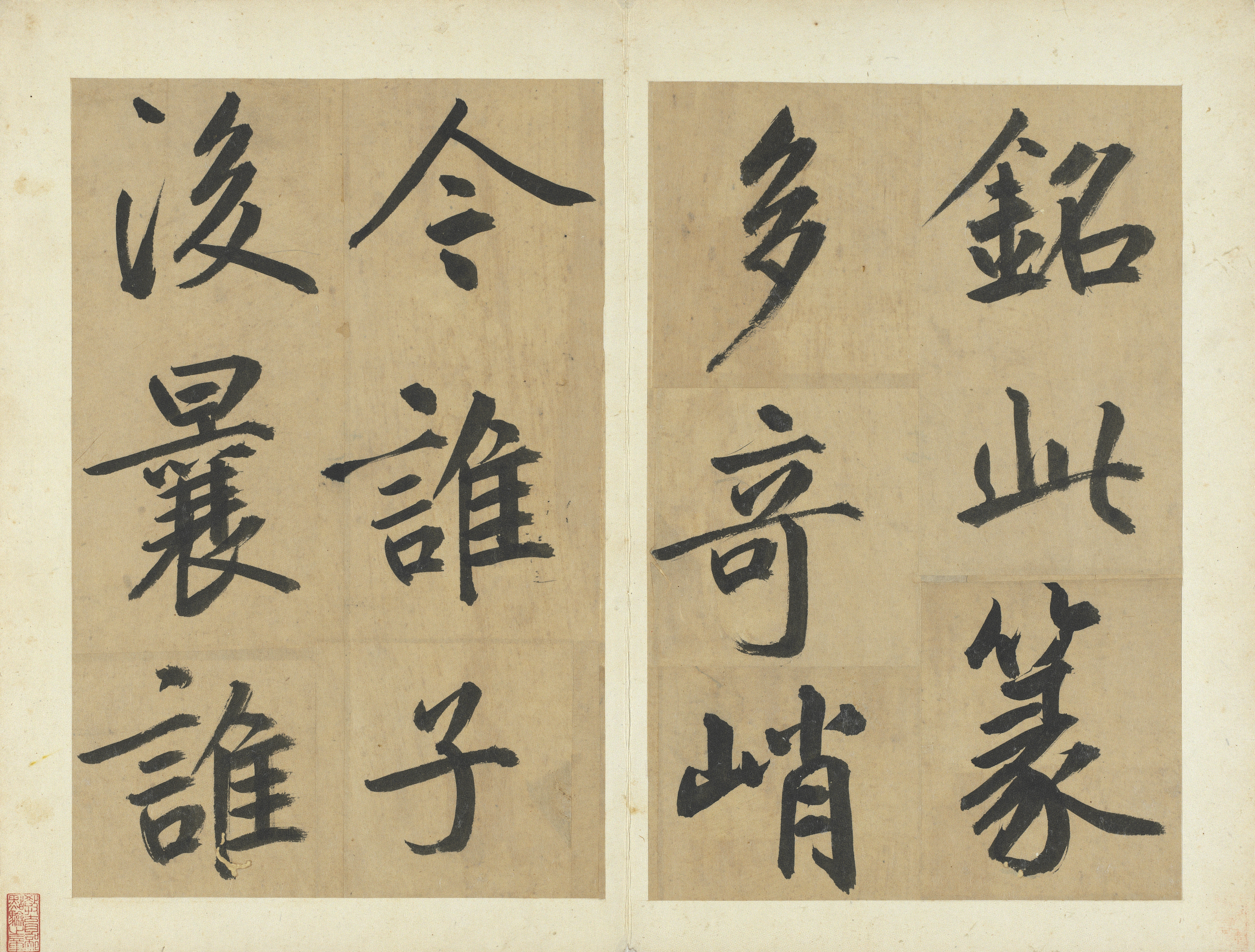

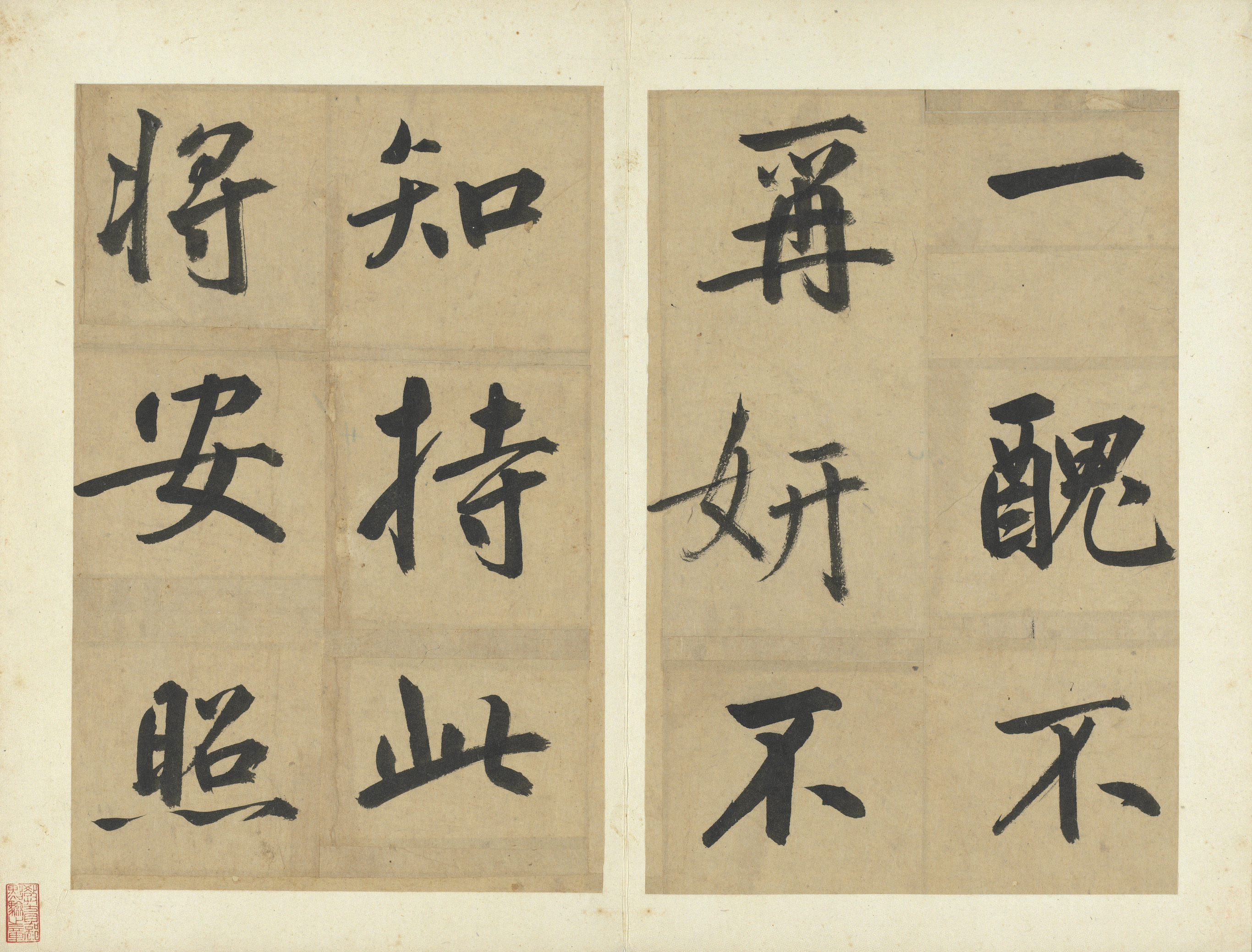

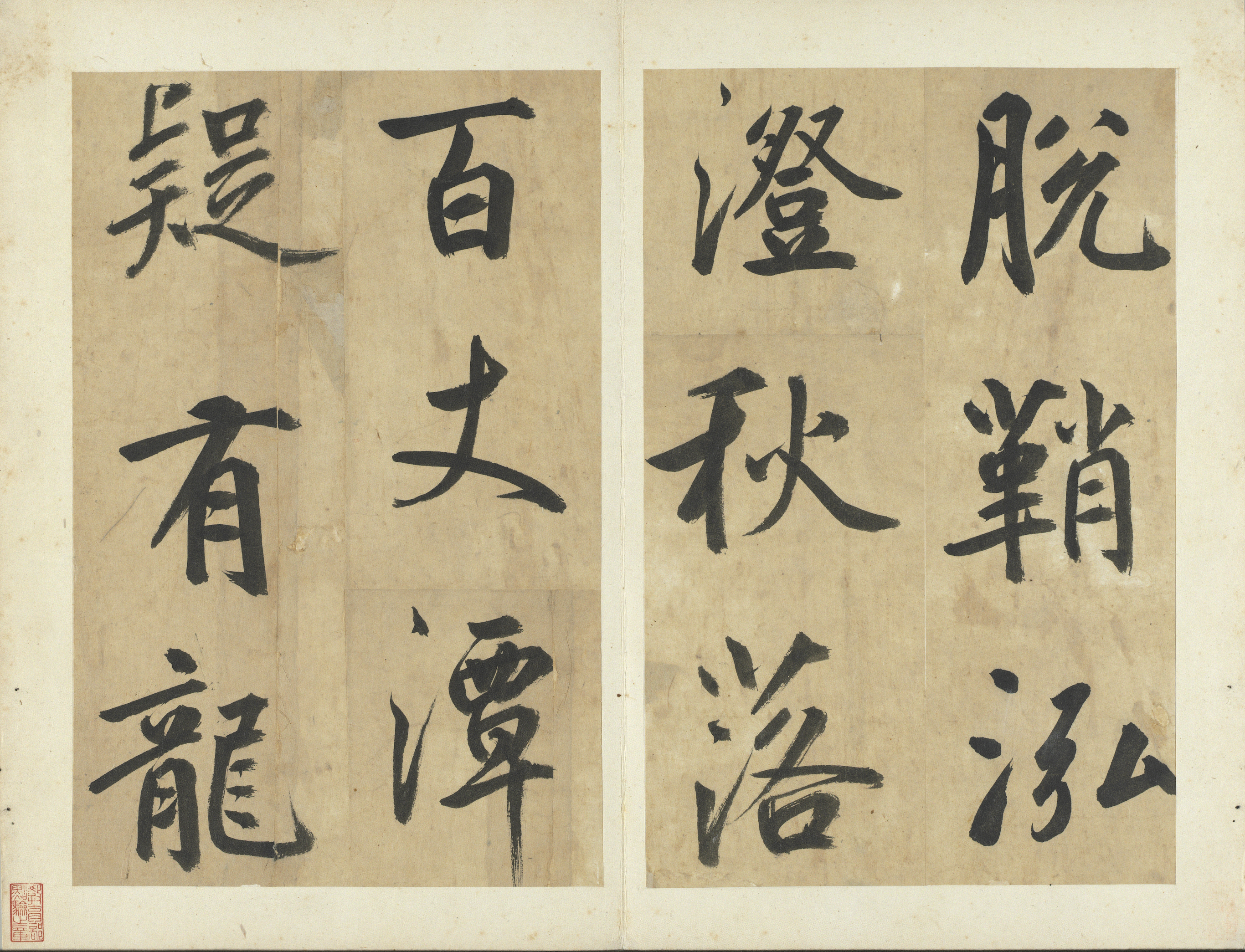

Song on a Light-Transmitting Mirror (Open)

Song on a Light-Transmitting MirrorSong on a Light-Transmitting Mirror (Close)Song on a Light-Transmitting Mirror

Song on a Light-Transmitting MirrorSong on a Light-Transmitting Mirror (Close)Song on a Light-Transmitting Mirror- Xianyu Shu (1246-1302), Yuan dynasty

- Album leaf, ink on paper, 30.5 x 19.8 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in March 2012 as a National Treasure

-

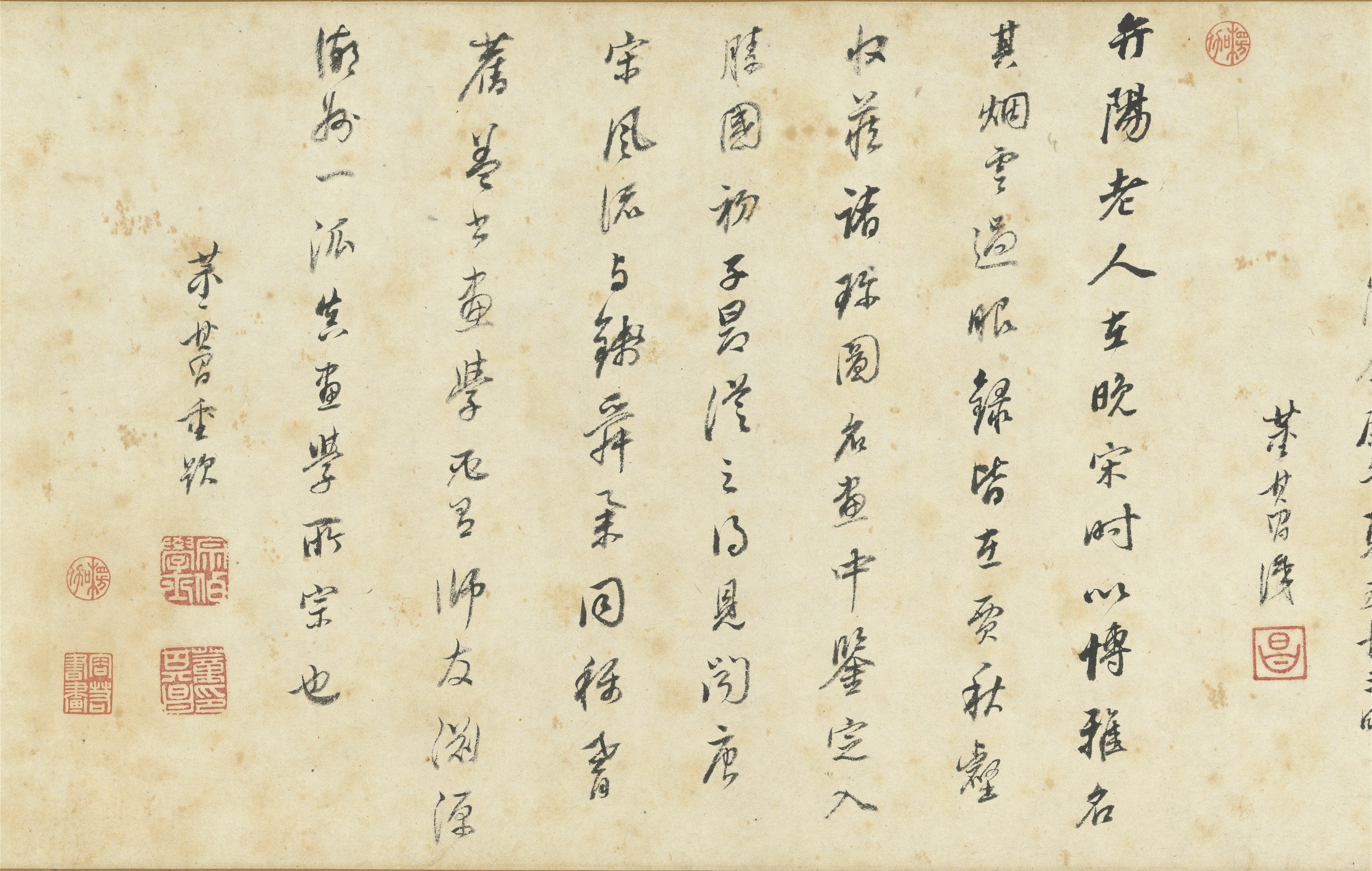

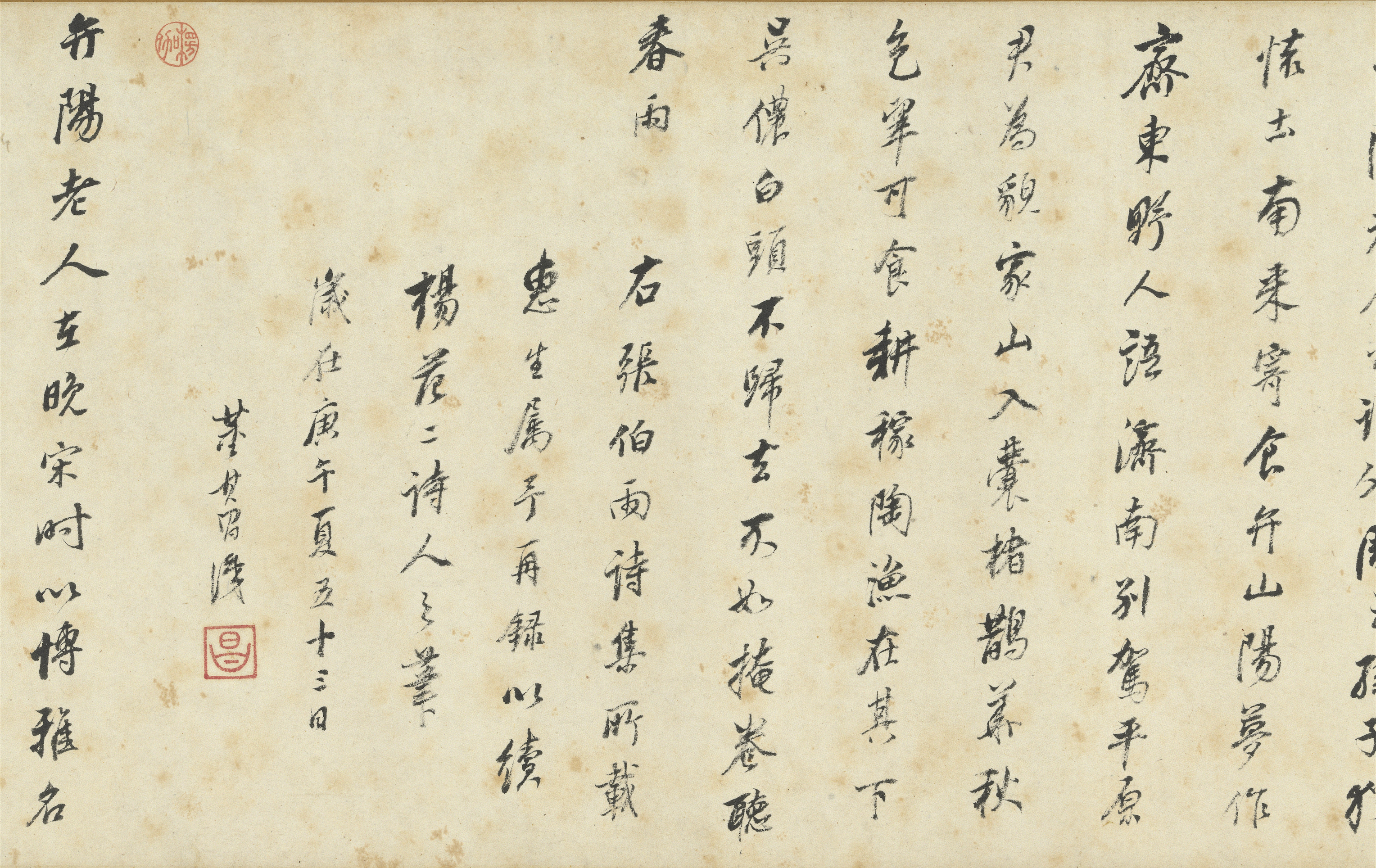

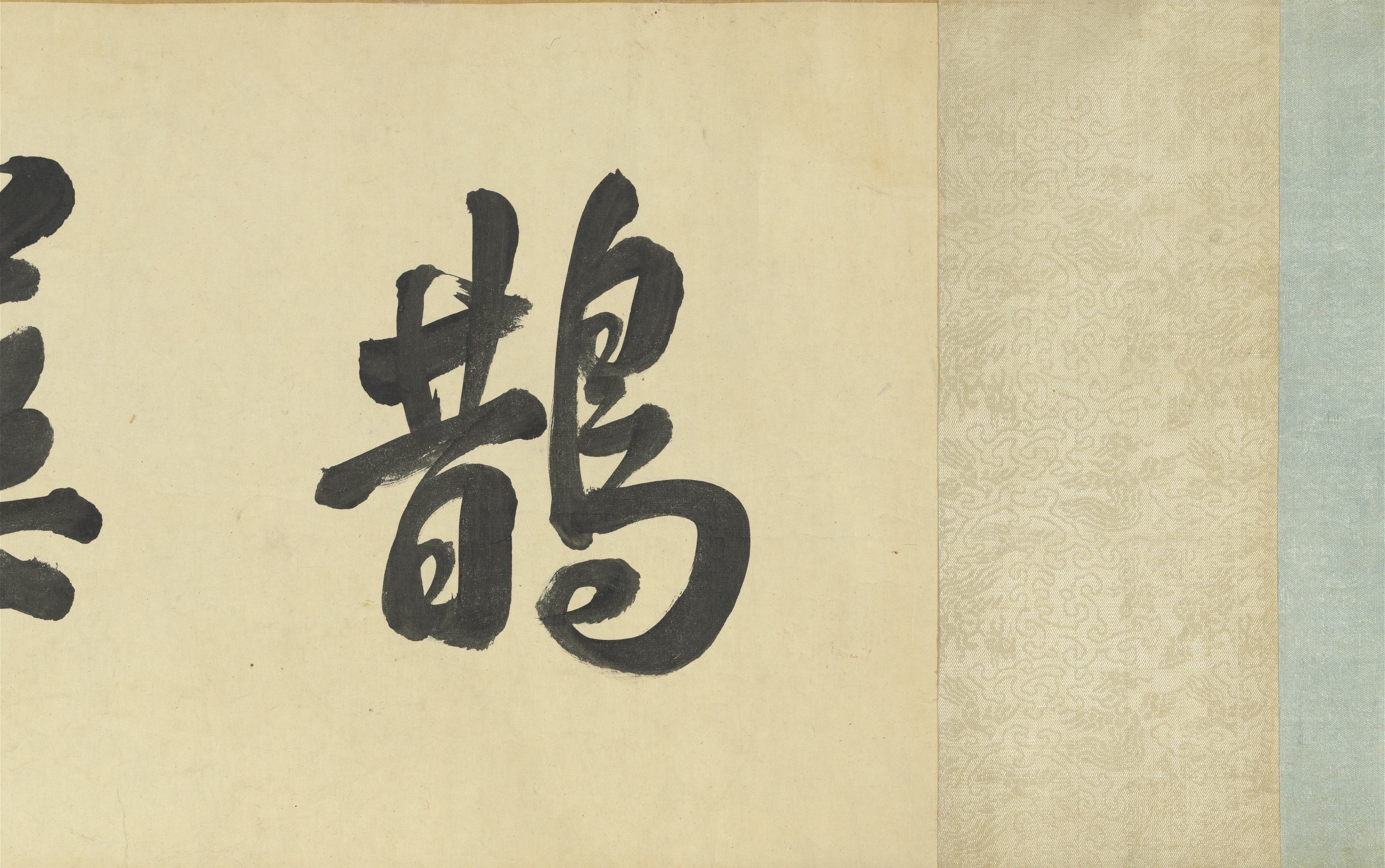

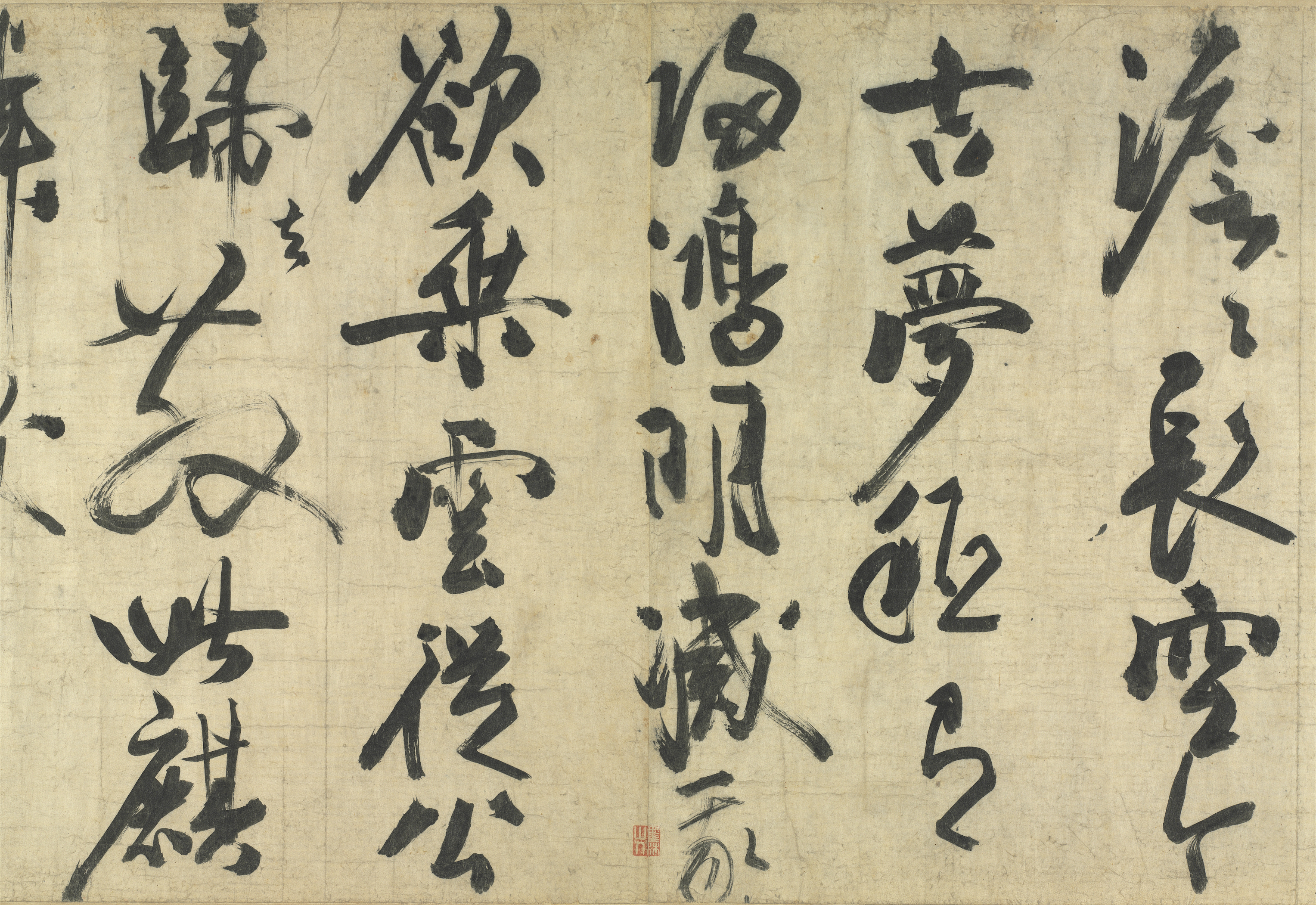

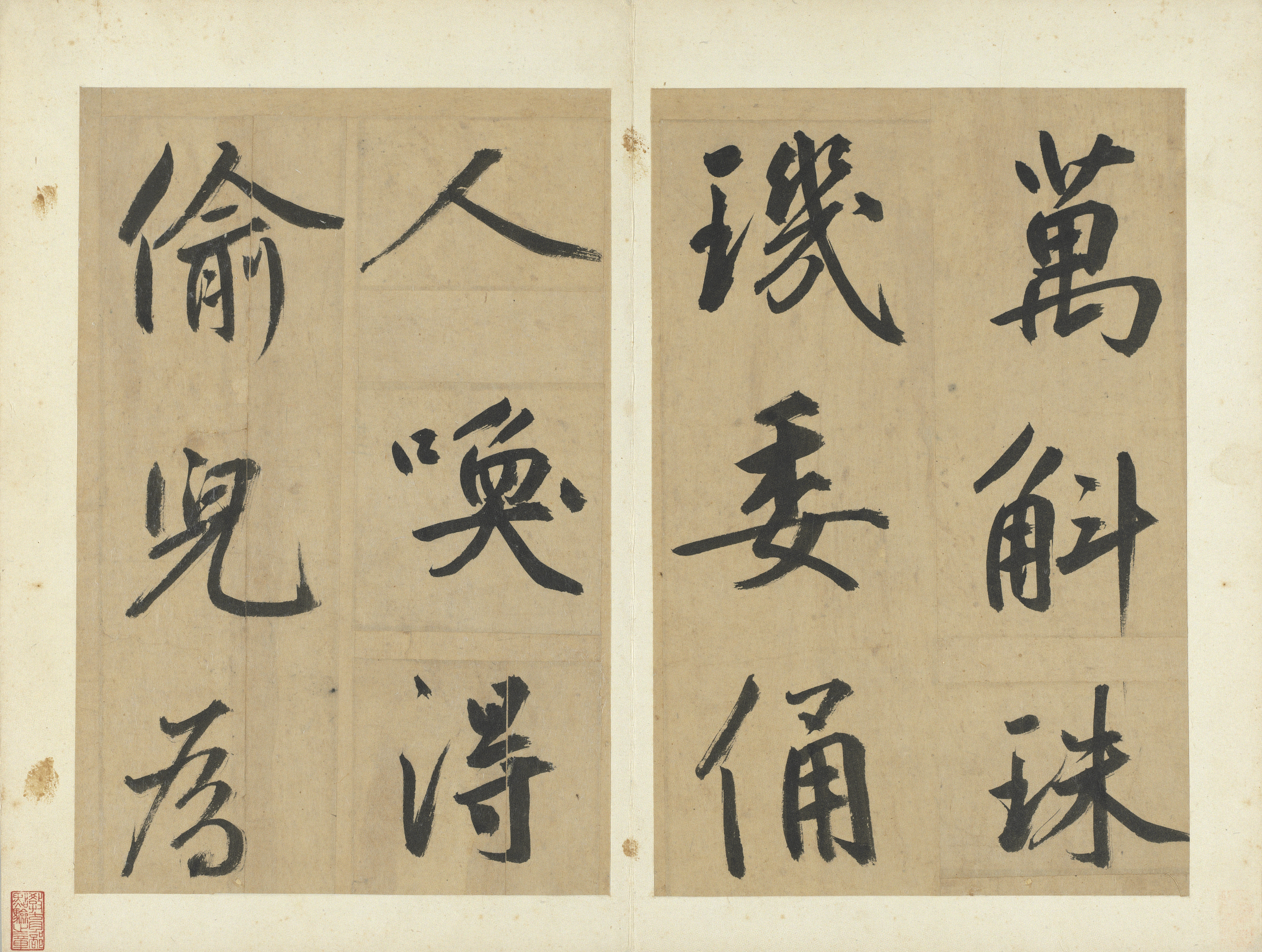

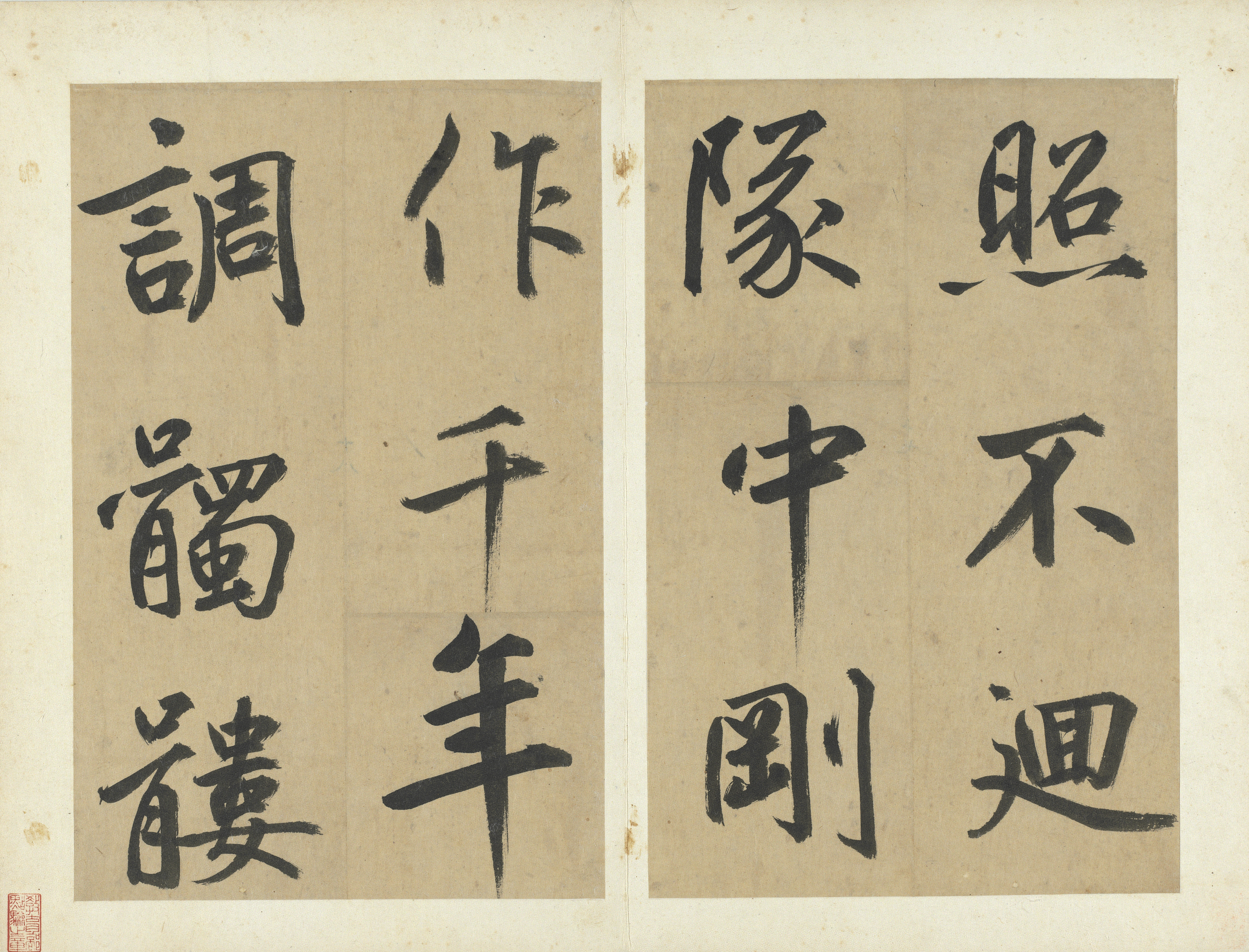

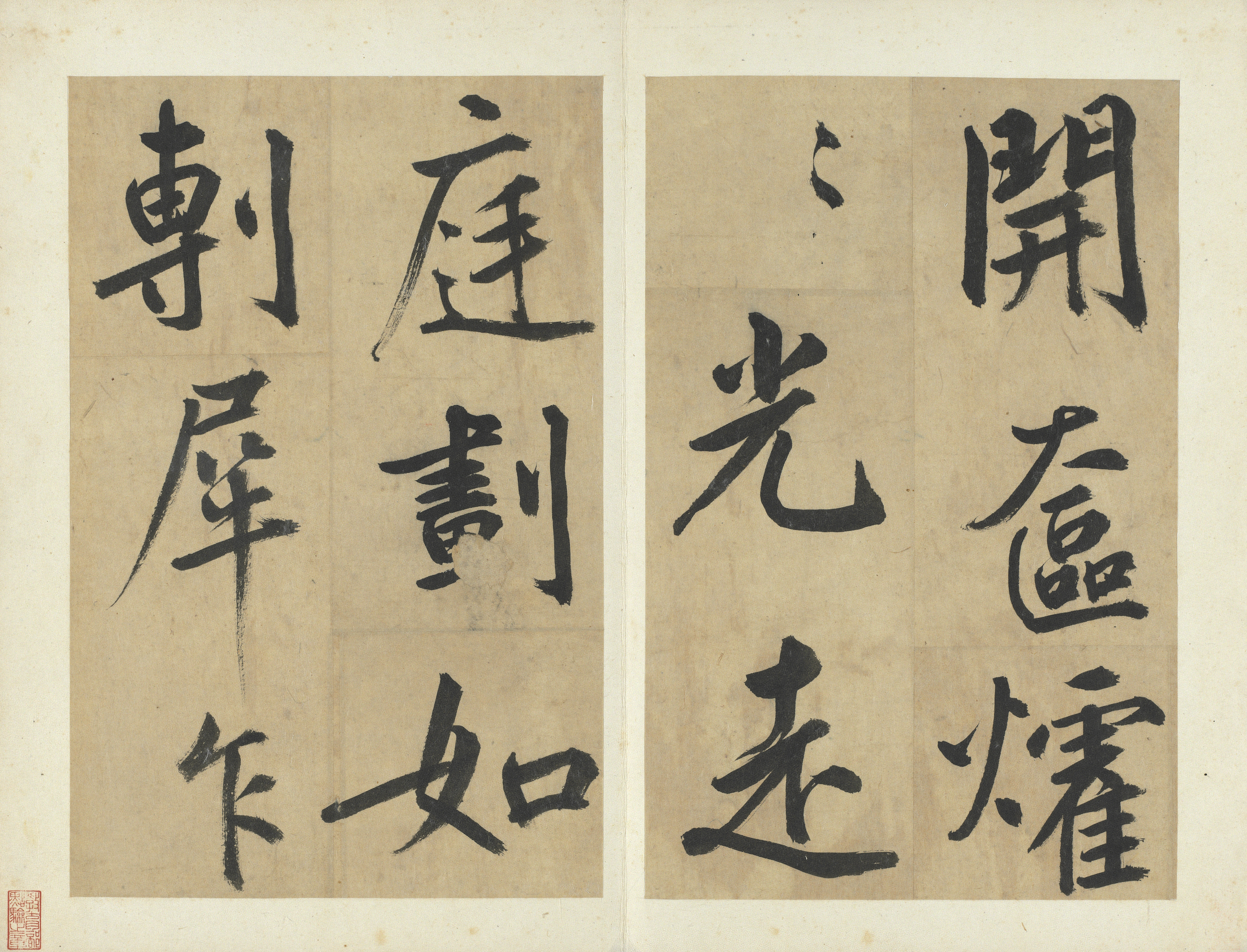

Ode on Pied Wagtails (Open)

Ode on Pied WagtailsOde on Pied Wagtails (Close)Ode on Pied Wagtails

Ode on Pied WagtailsOde on Pied Wagtails (Close)Ode on Pied Wagtails- Xuanzong (685-762), Tang dynasty

- Handscroll, ink on paper, 24.5 x 184.9 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in March 2012 as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/11/15-12/25

-

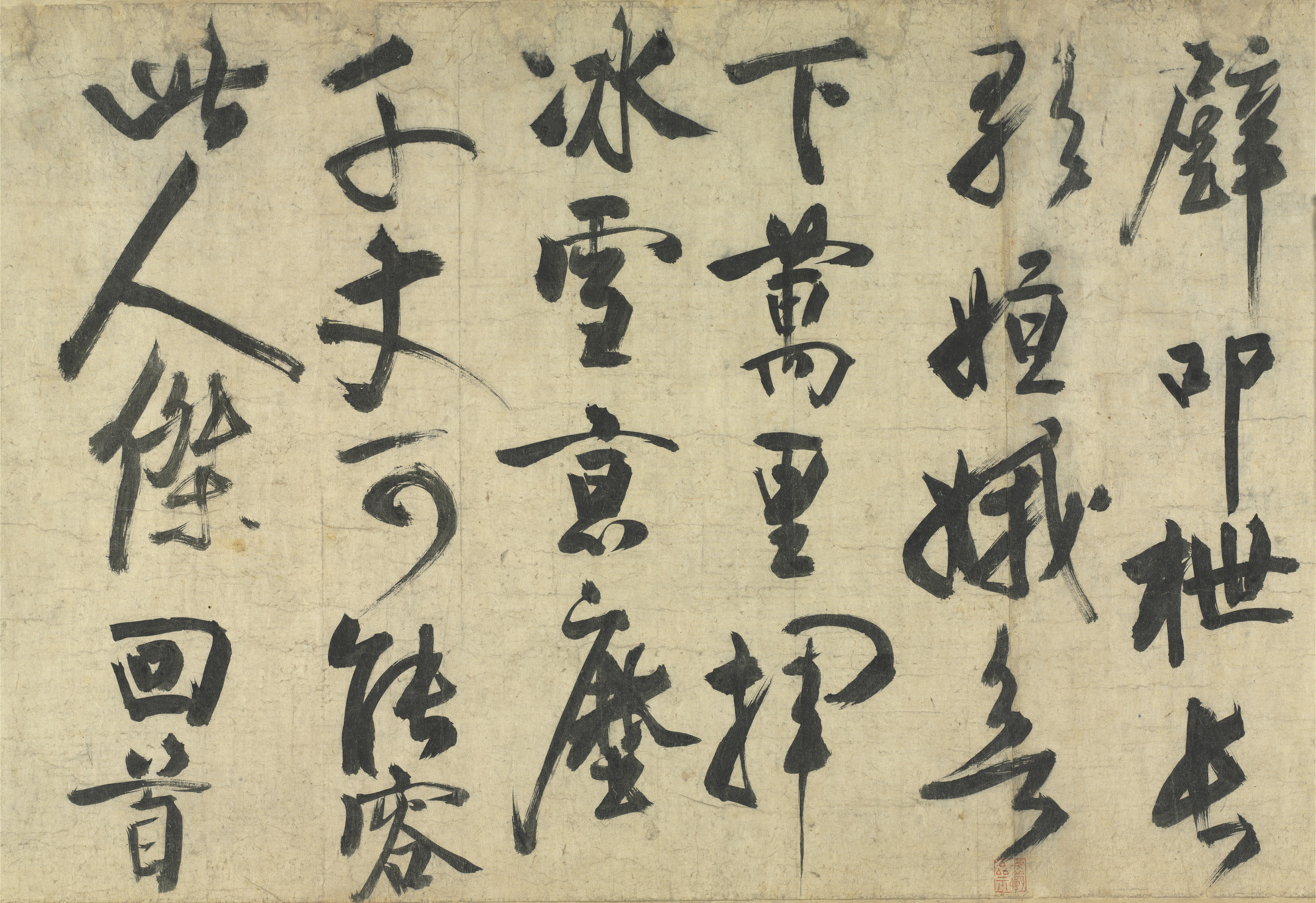

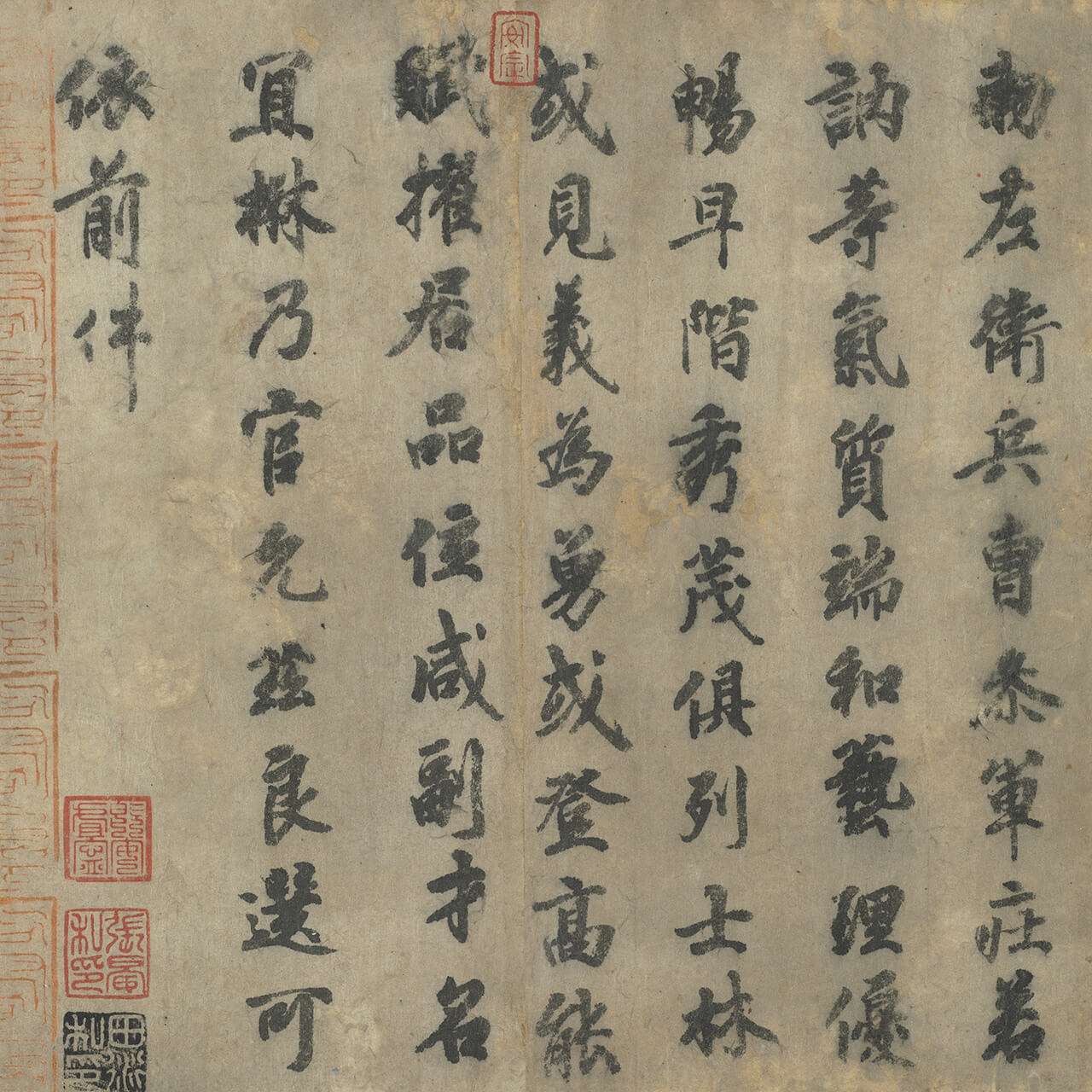

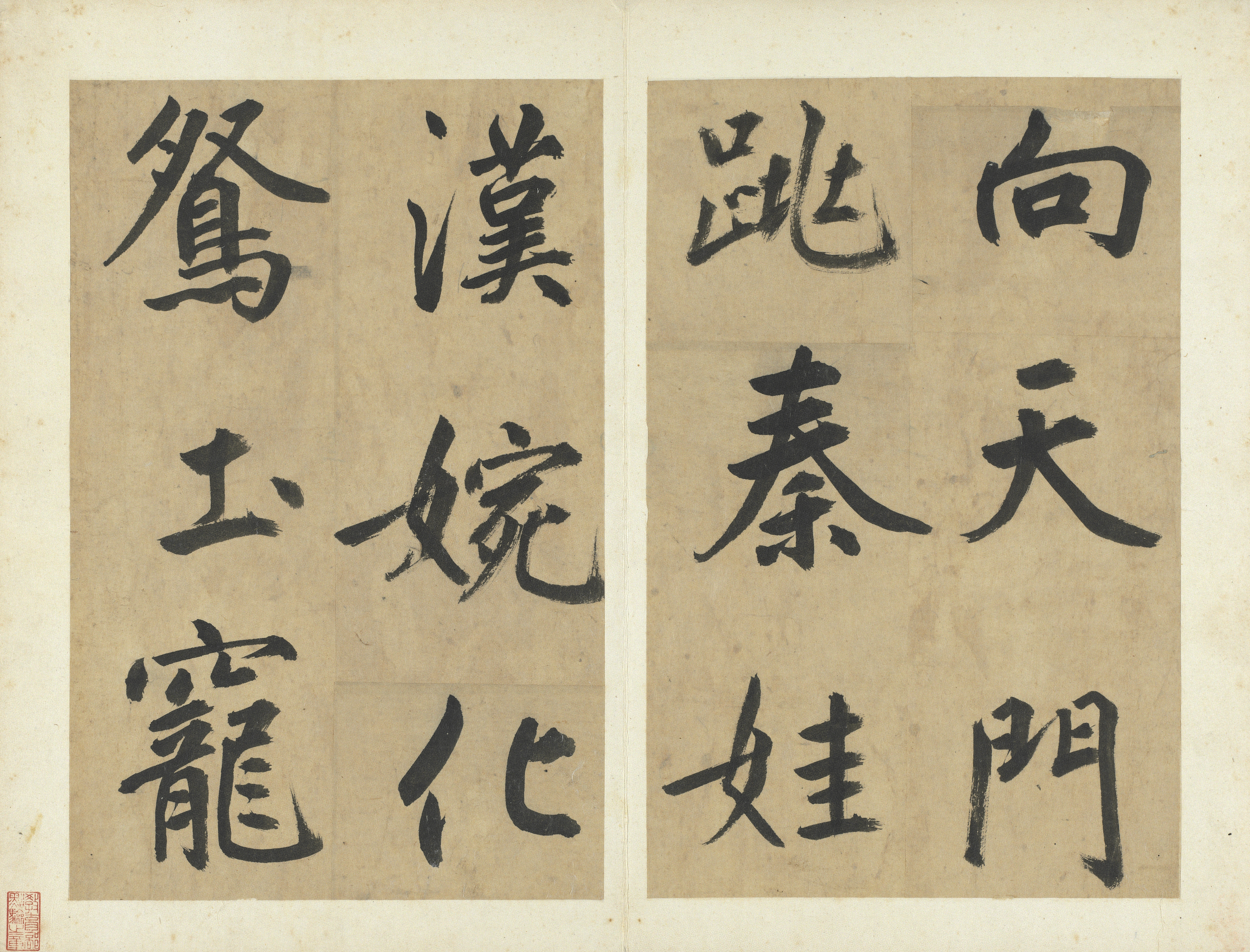

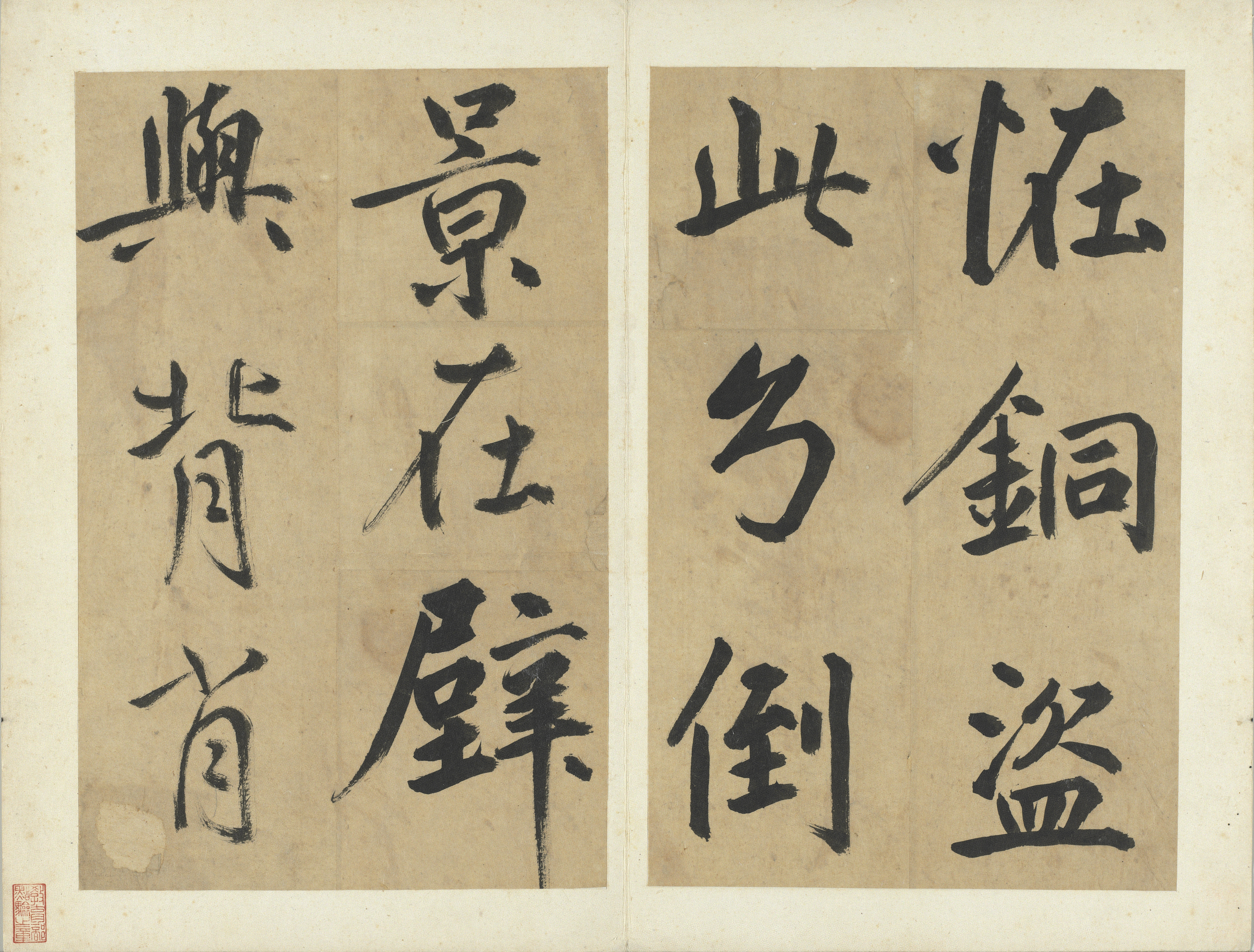

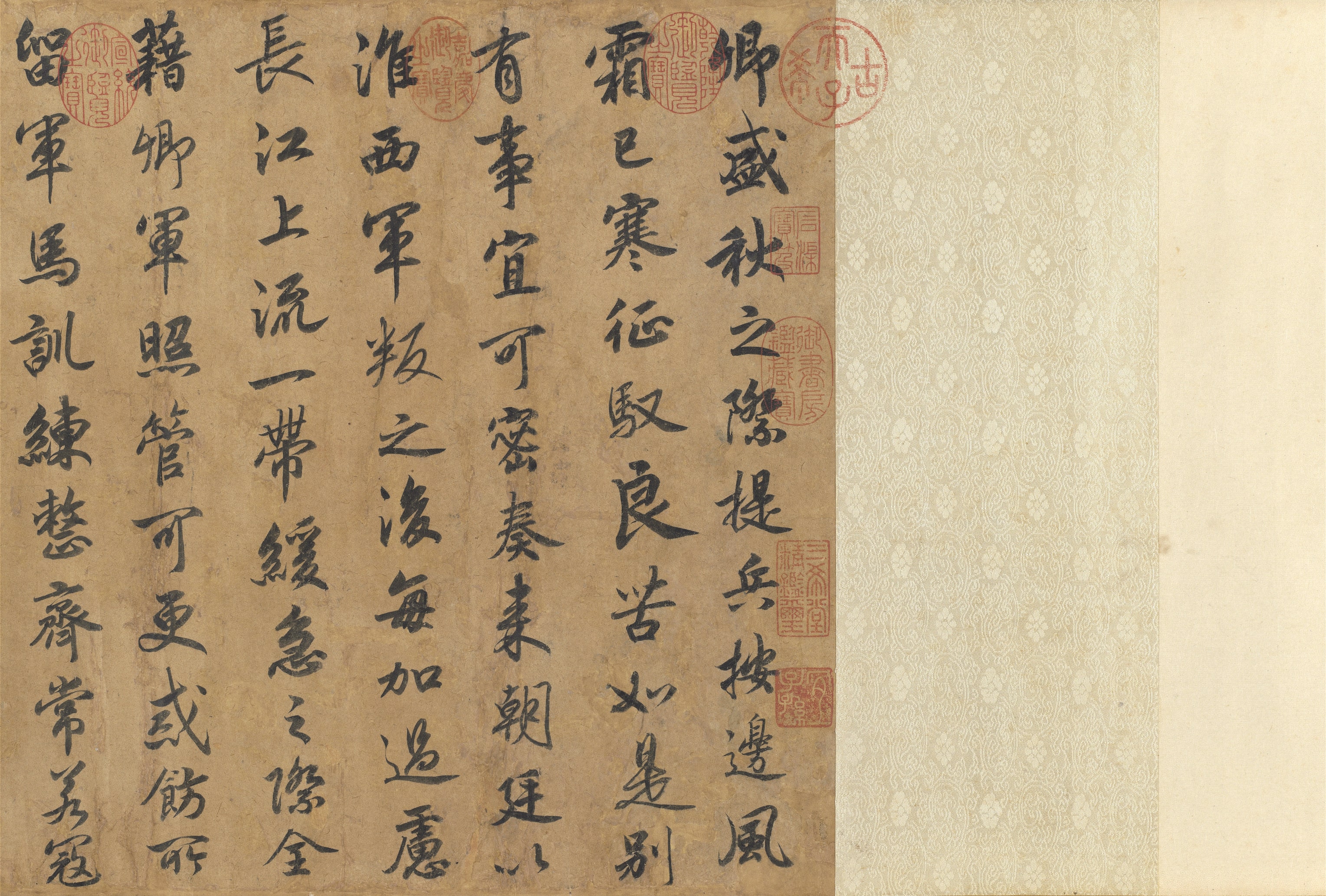

Imperial Order Presented to Yue Fei (Open)

Imperial Order Presented to Yue FeiImperial Order Presented to Yue Fei (Close)Imperial Order Presented to Yue Fei

Imperial Order Presented to Yue FeiImperial Order Presented to Yue Fei (Close)Imperial Order Presented to Yue Fei- Gaozong (1107-1187), Song dynasty

- Handscroll, ink on paper, 37 x 61.4 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in April 2011 as a National Treasure

-

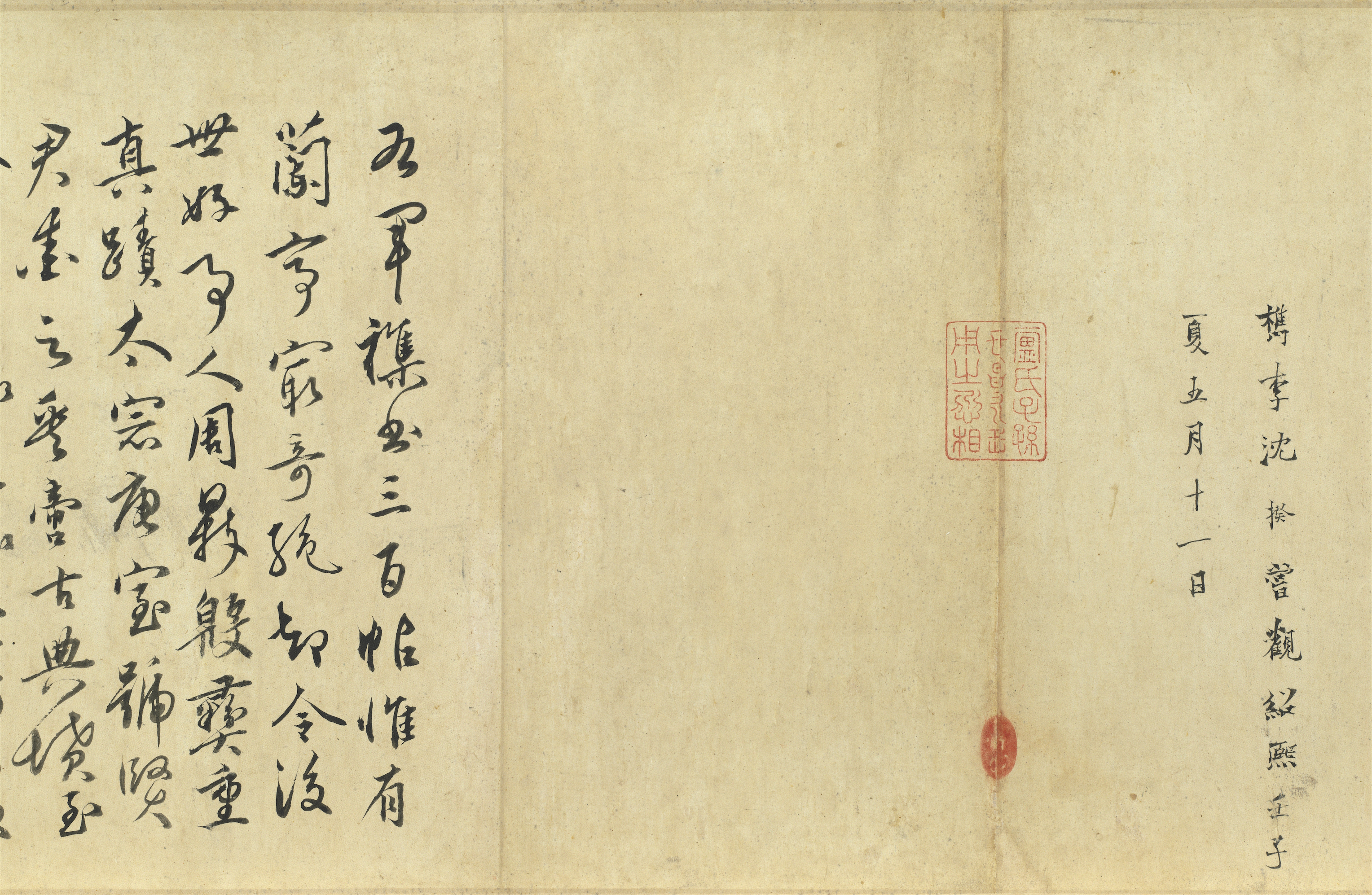

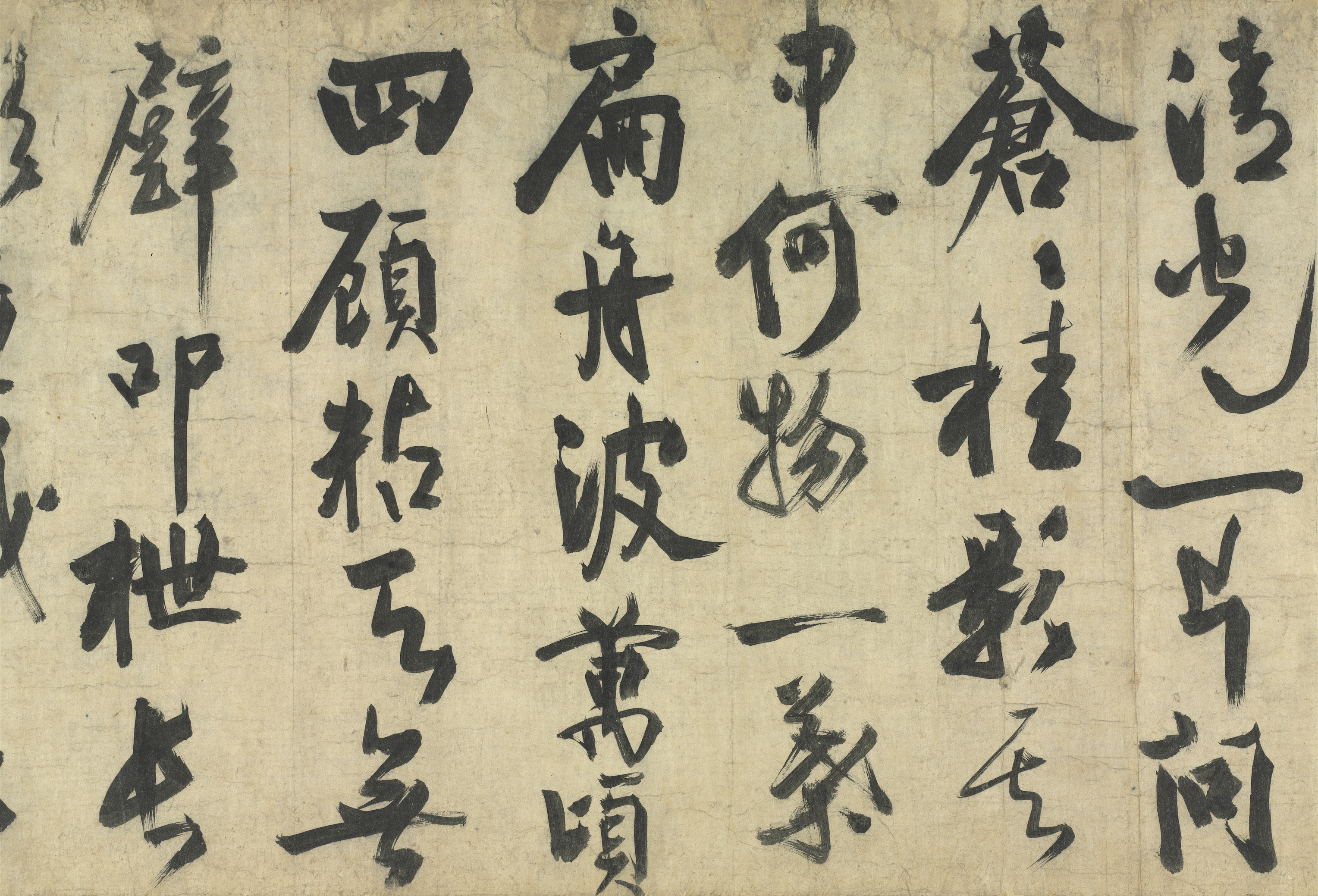

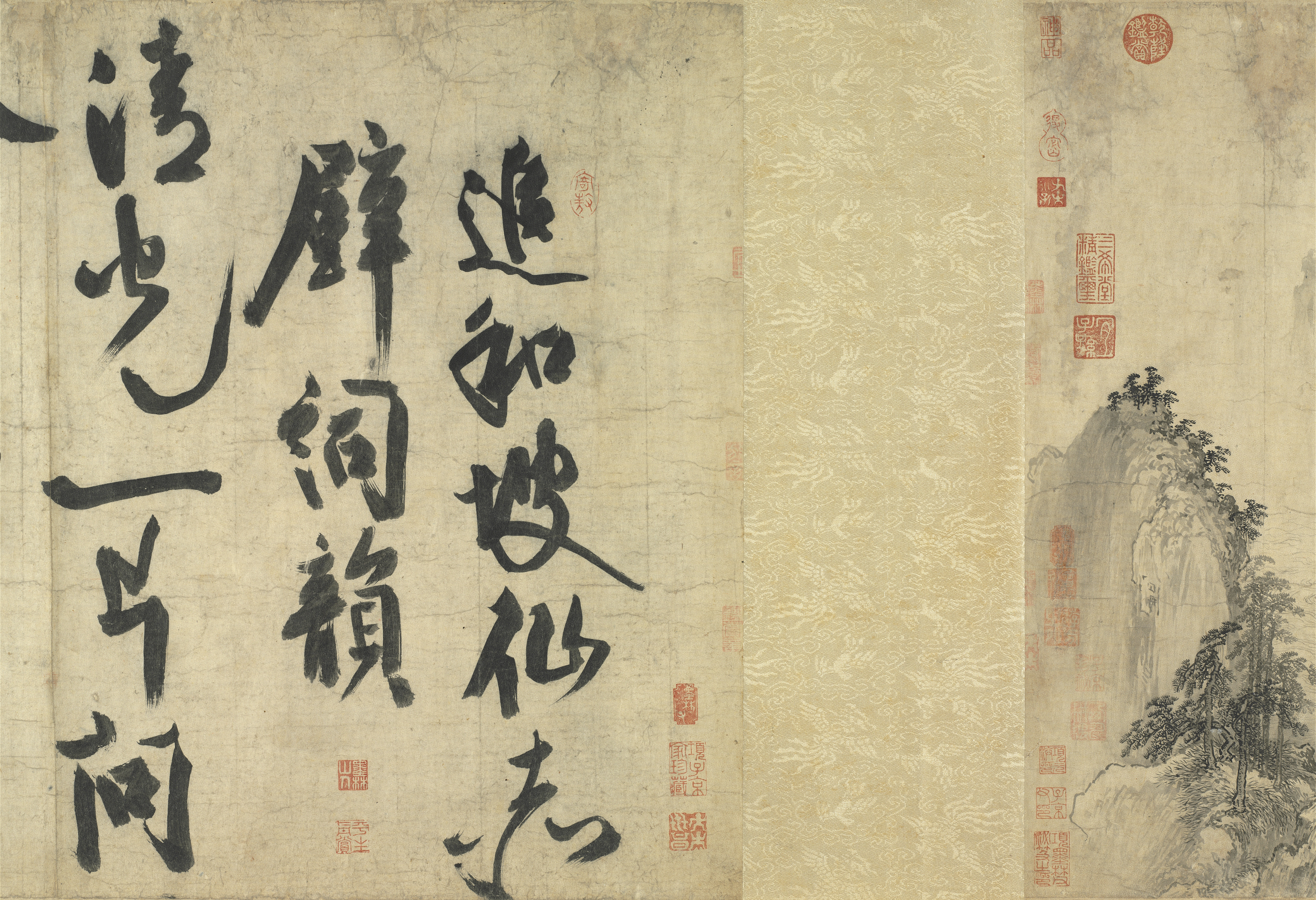

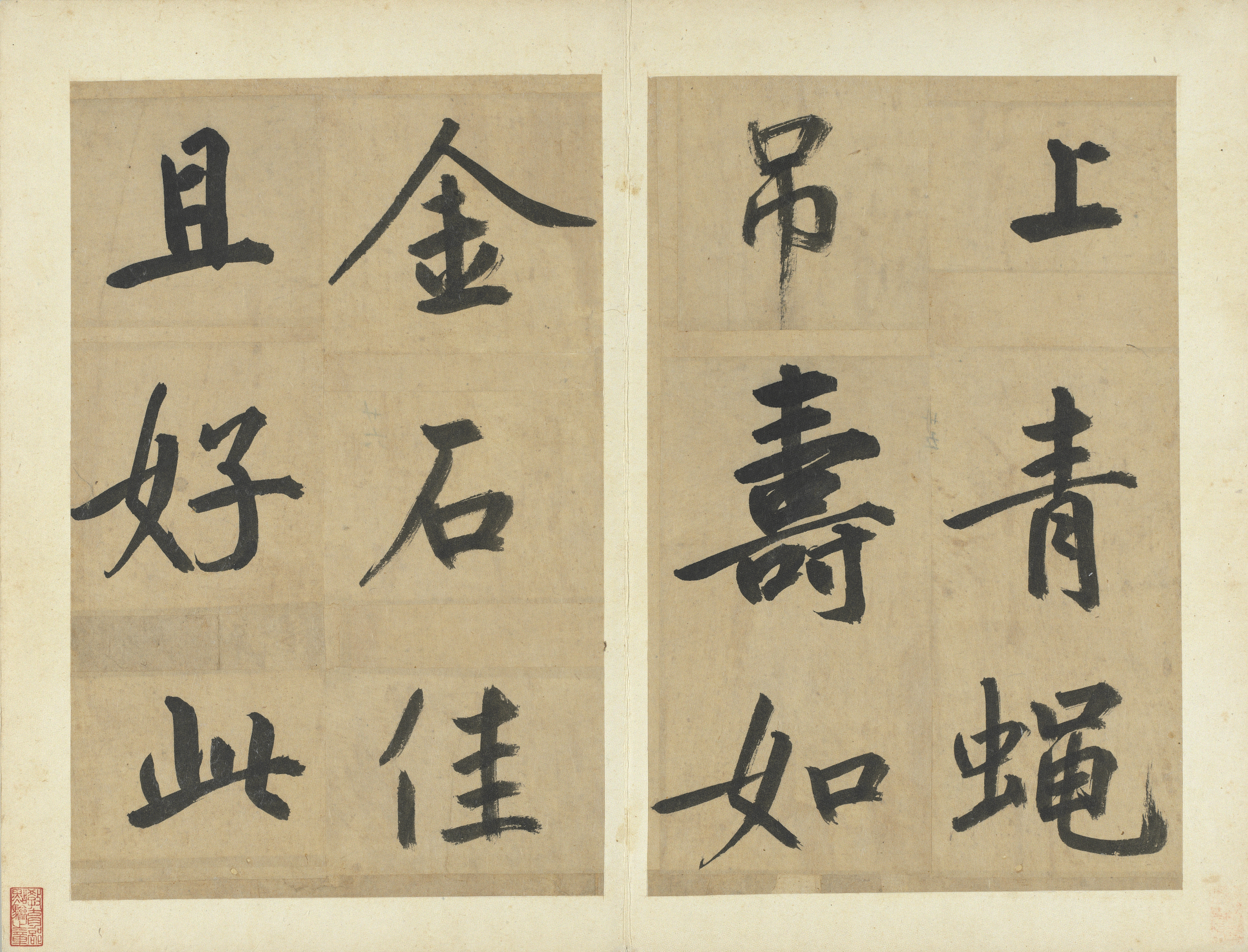

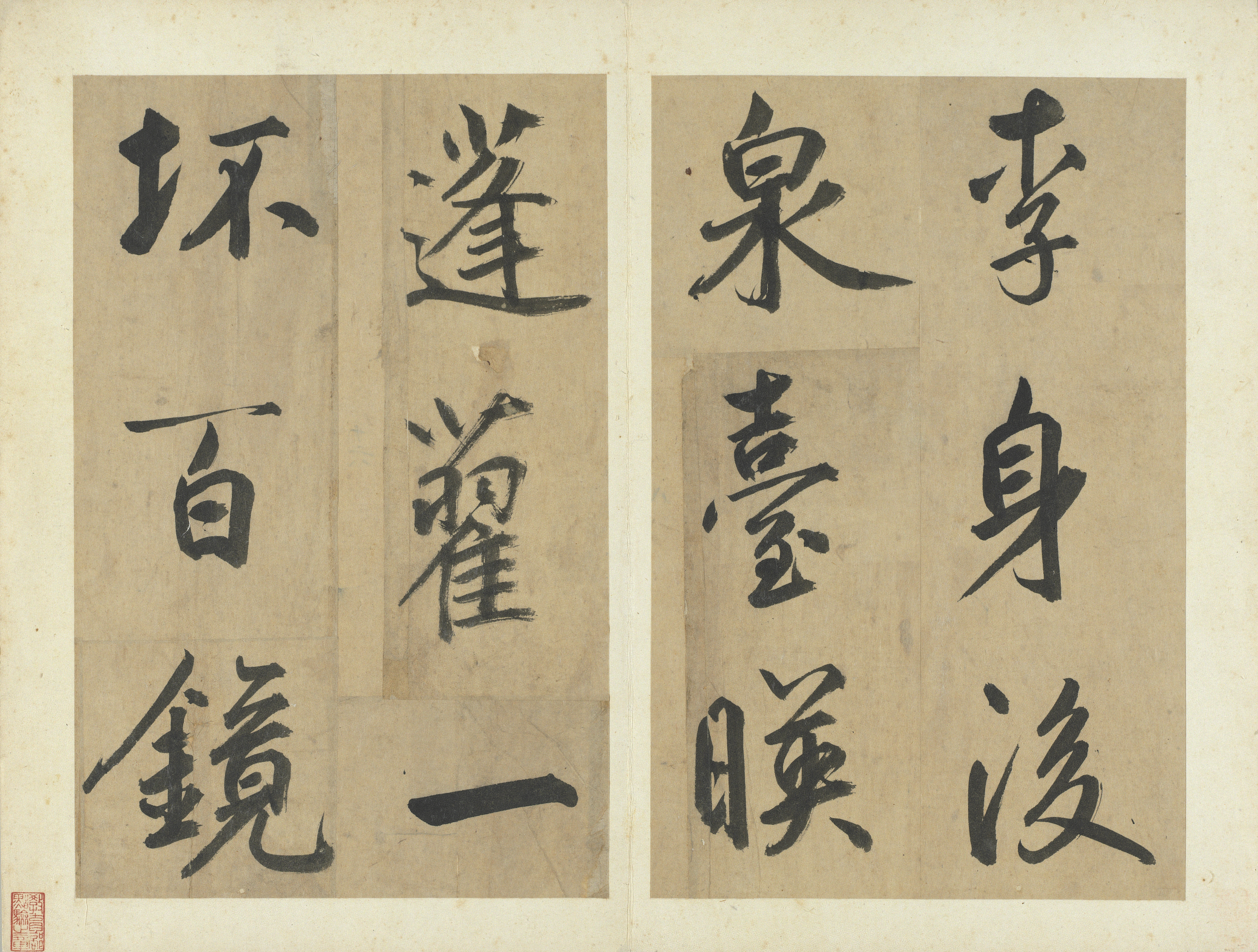

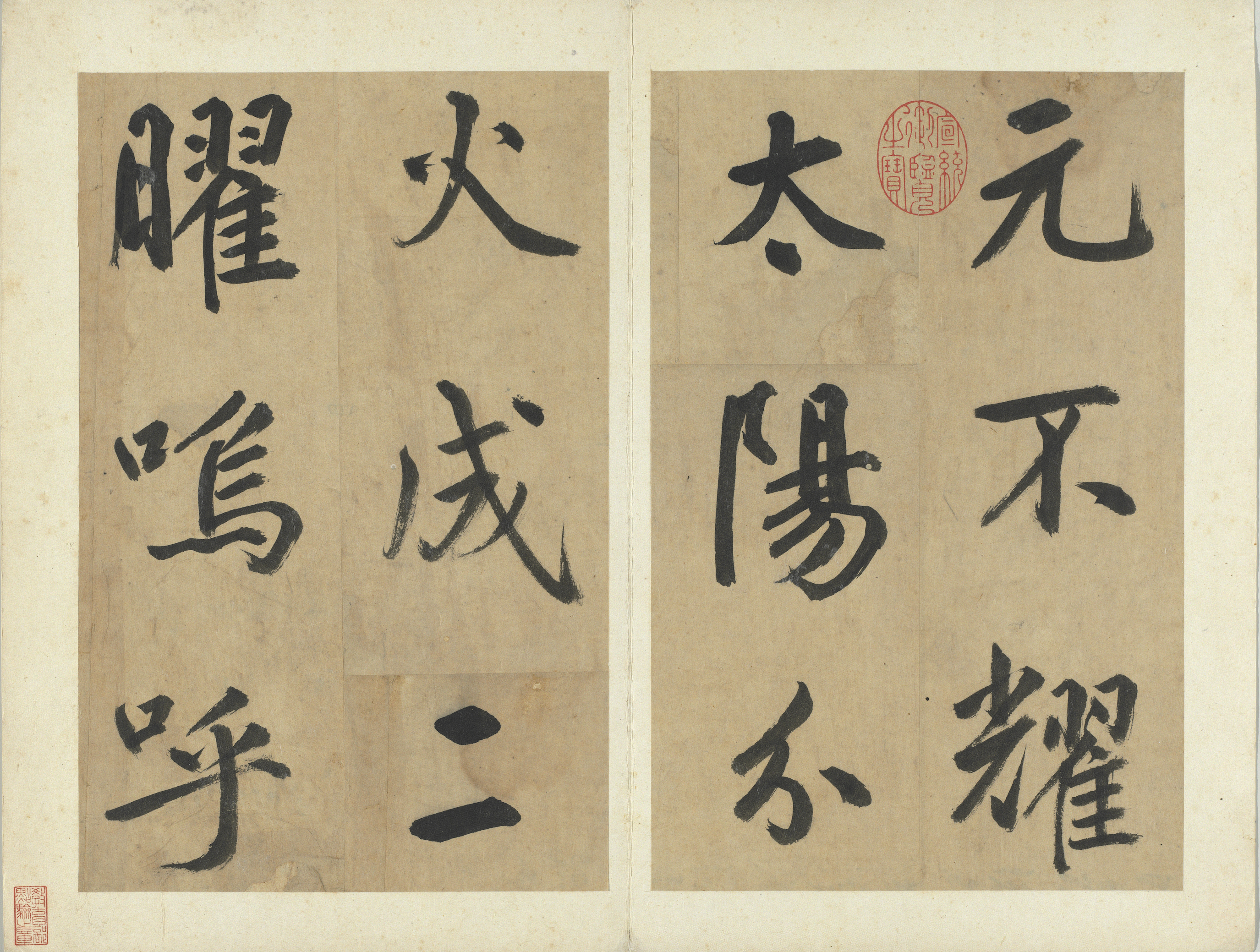

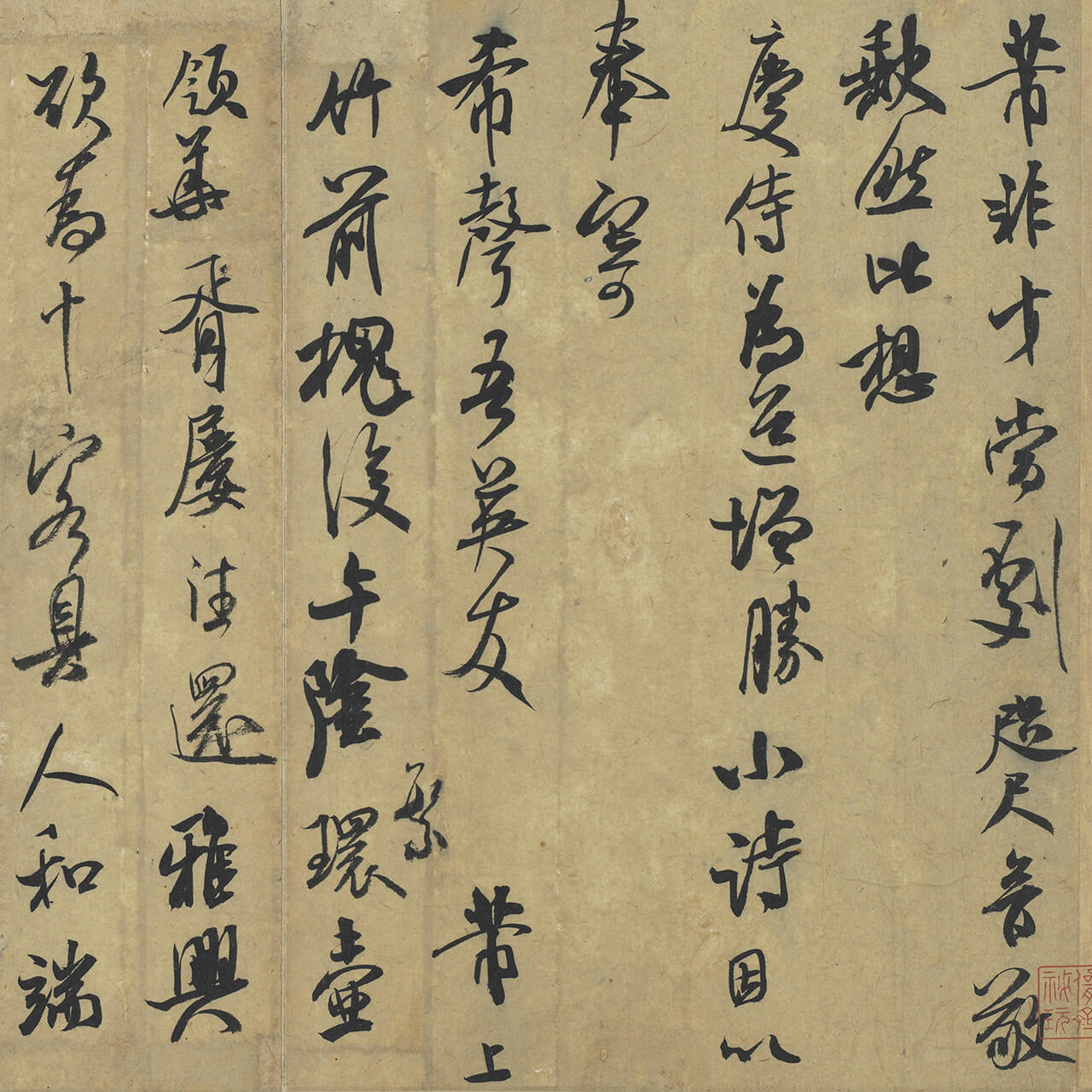

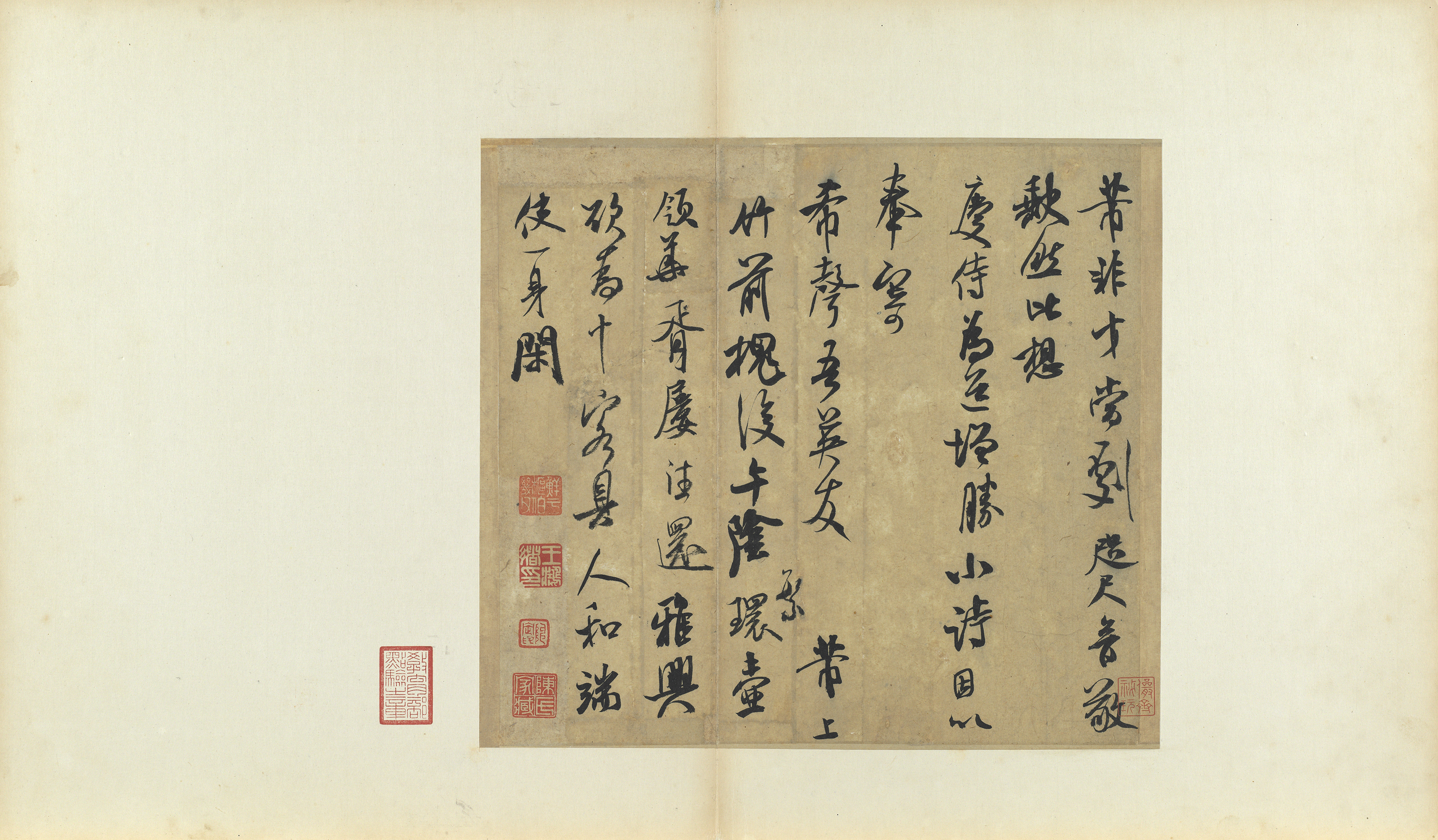

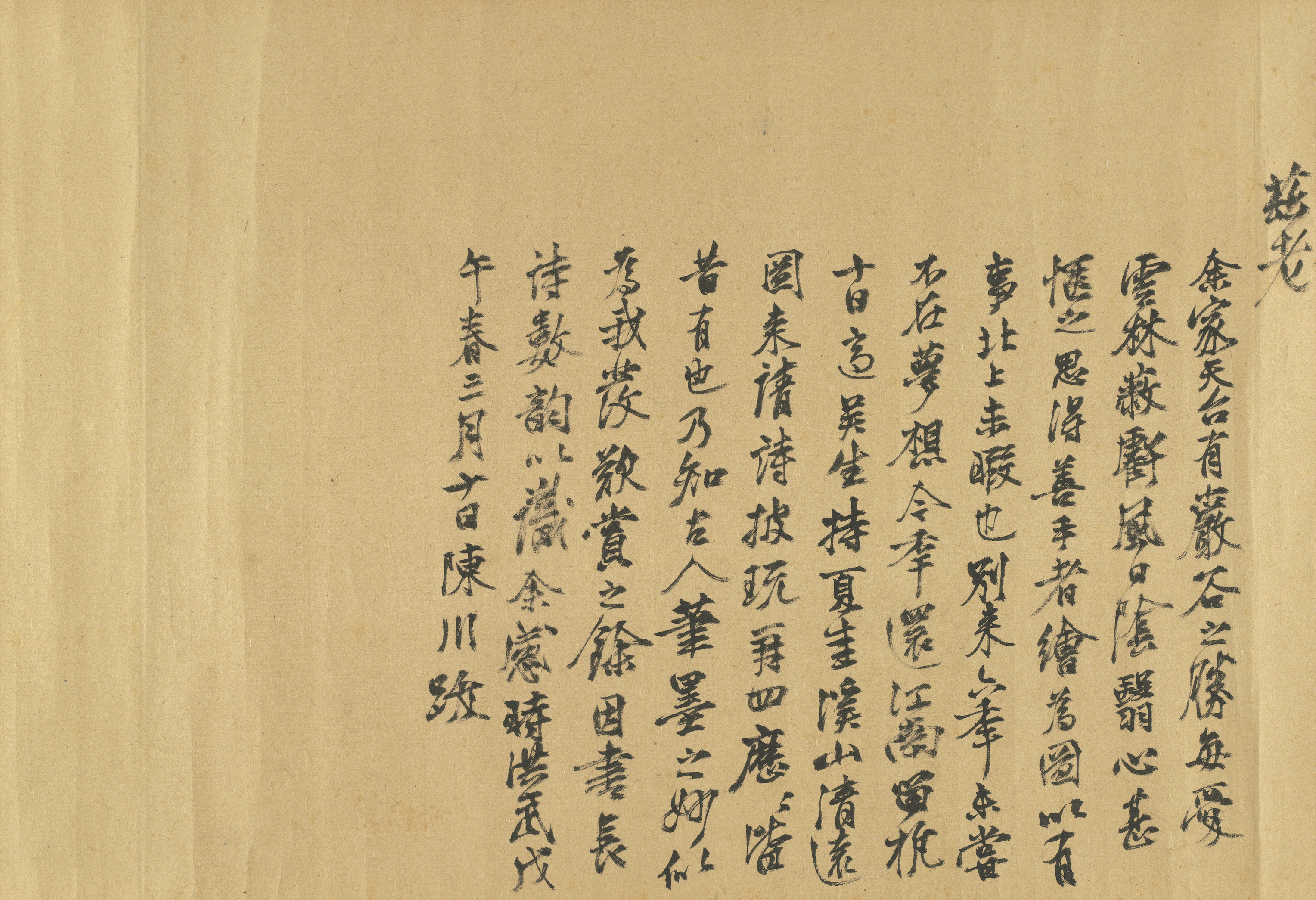

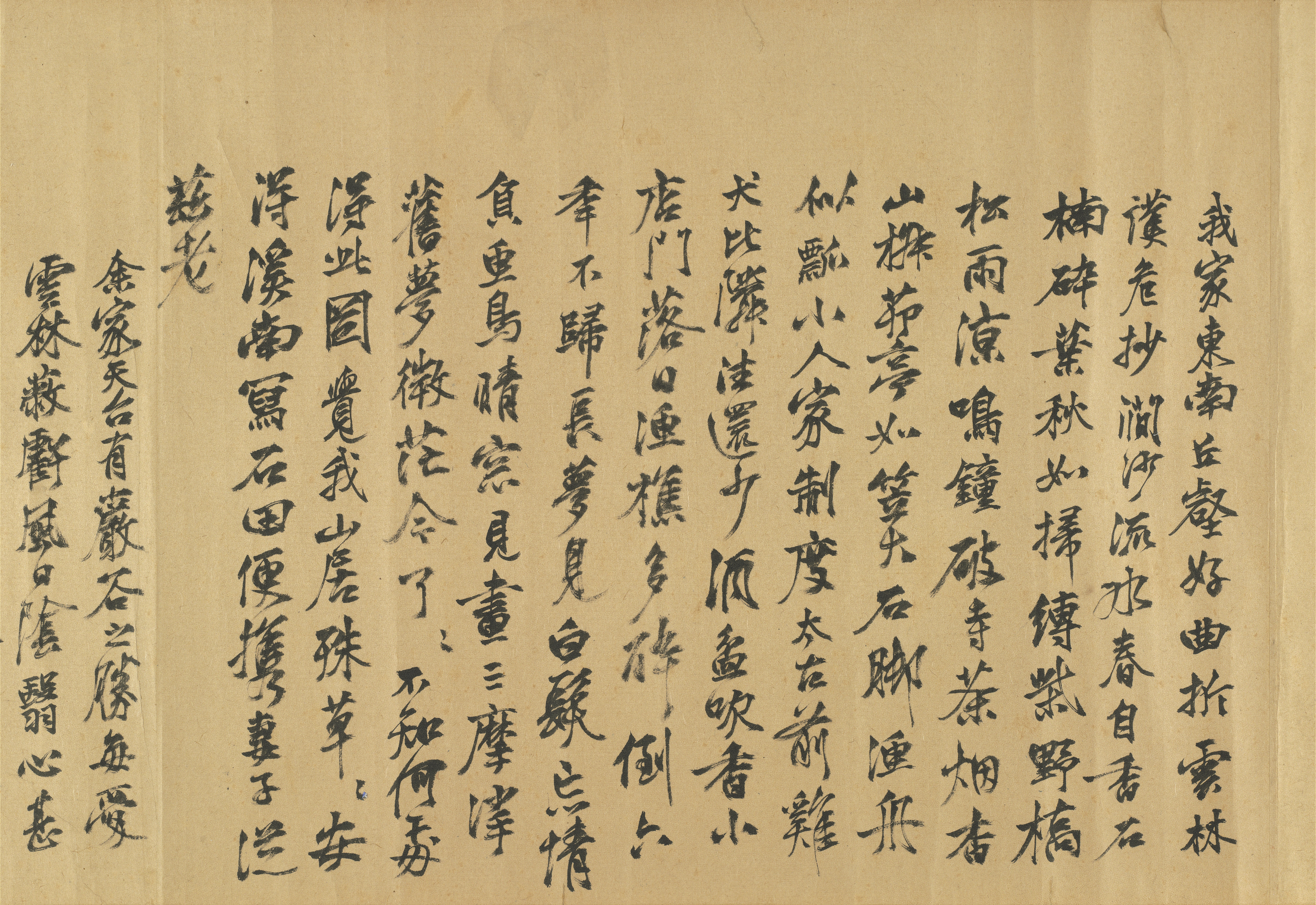

Letter to My Friend Xisheng with a Seven-character Poem (Open)

Letter to My Friend Xisheng with a Seven-character PoemLetter to My Friend Xisheng with a Seven-character Poem (Close)Letter to My Friend Xisheng with a Seven-character Poem

Letter to My Friend Xisheng with a Seven-character PoemLetter to My Friend Xisheng with a Seven-character Poem (Close)Letter to My Friend Xisheng with a Seven-character Poem- Mi Fu (1051-1108), Song dynasty

- Album leaf, ink on paper, 30 x 33.5 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in January 2013 as a National Treasure

-

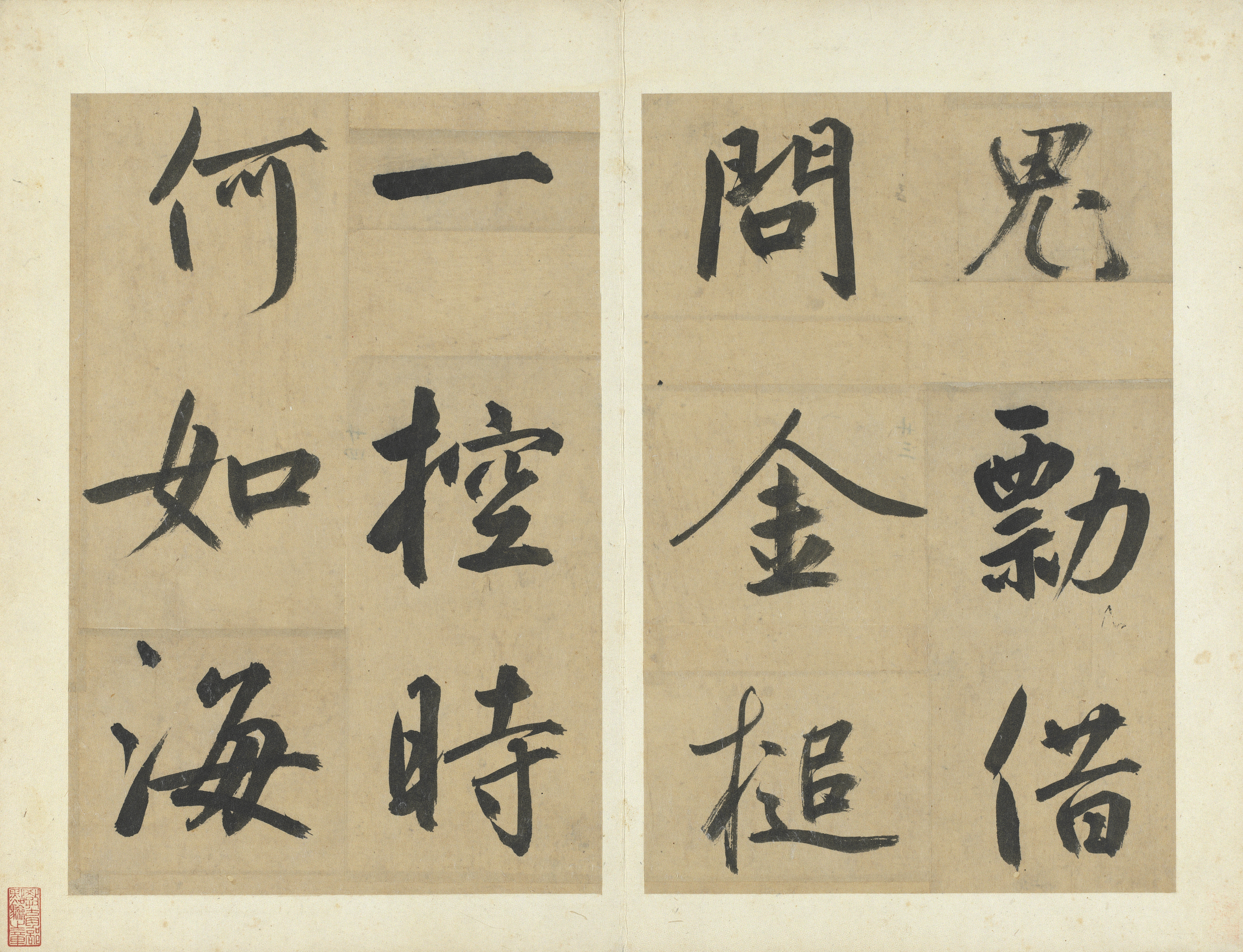

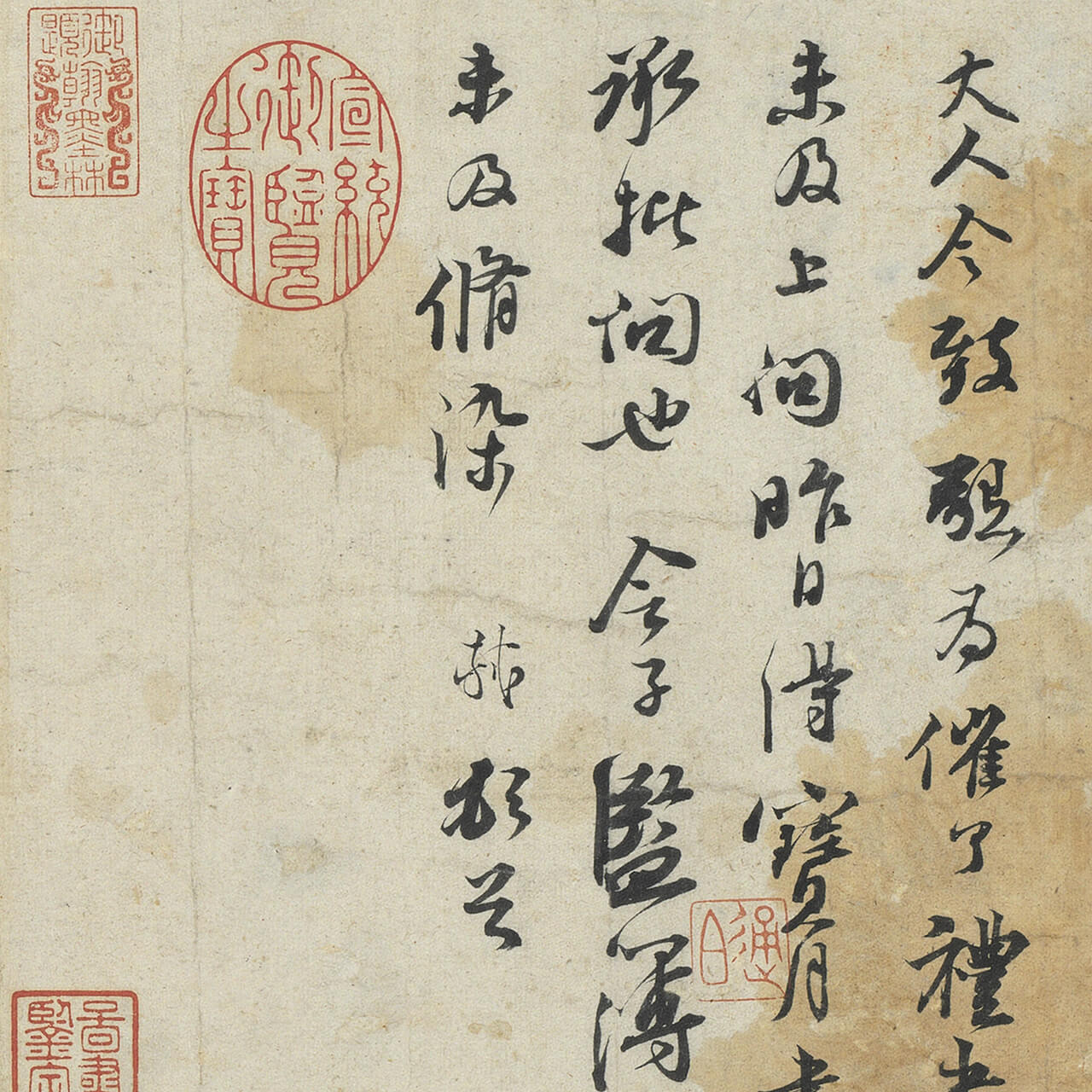

Letters (Baoyue, Chicha) - Open

Letters (Baoyue, Chicha)Letters (Baoyue, Chicha) - CloseLetters (Baoyue, Chicha)

Letters (Baoyue, Chicha)Letters (Baoyue, Chicha) - CloseLetters (Baoyue, Chicha)- Su Shi (1037-1101), Song dynasty

- Album leaf, ink on paper, 23.2 x 17.8 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in May 2015 as a National Treasure

-

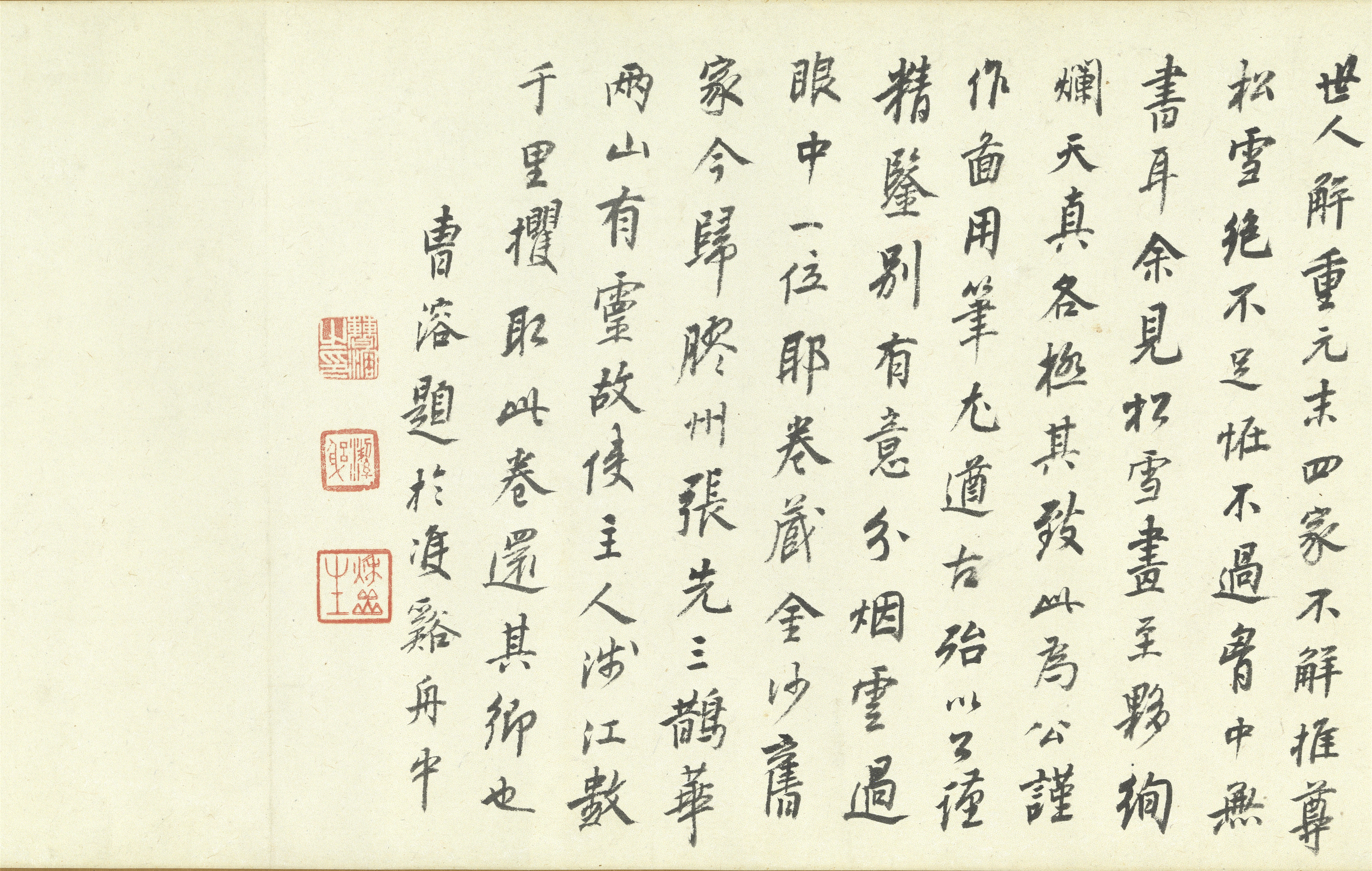

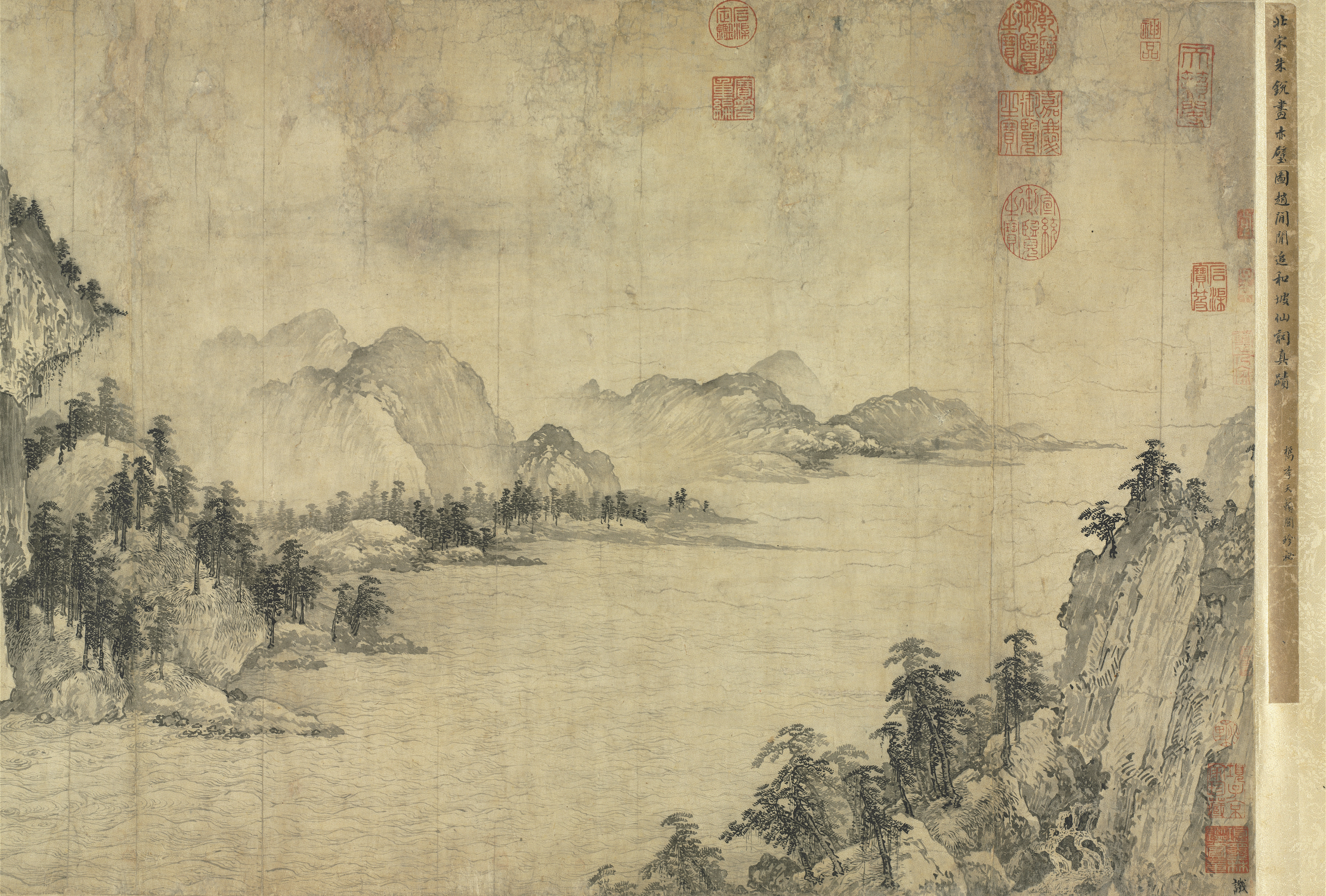

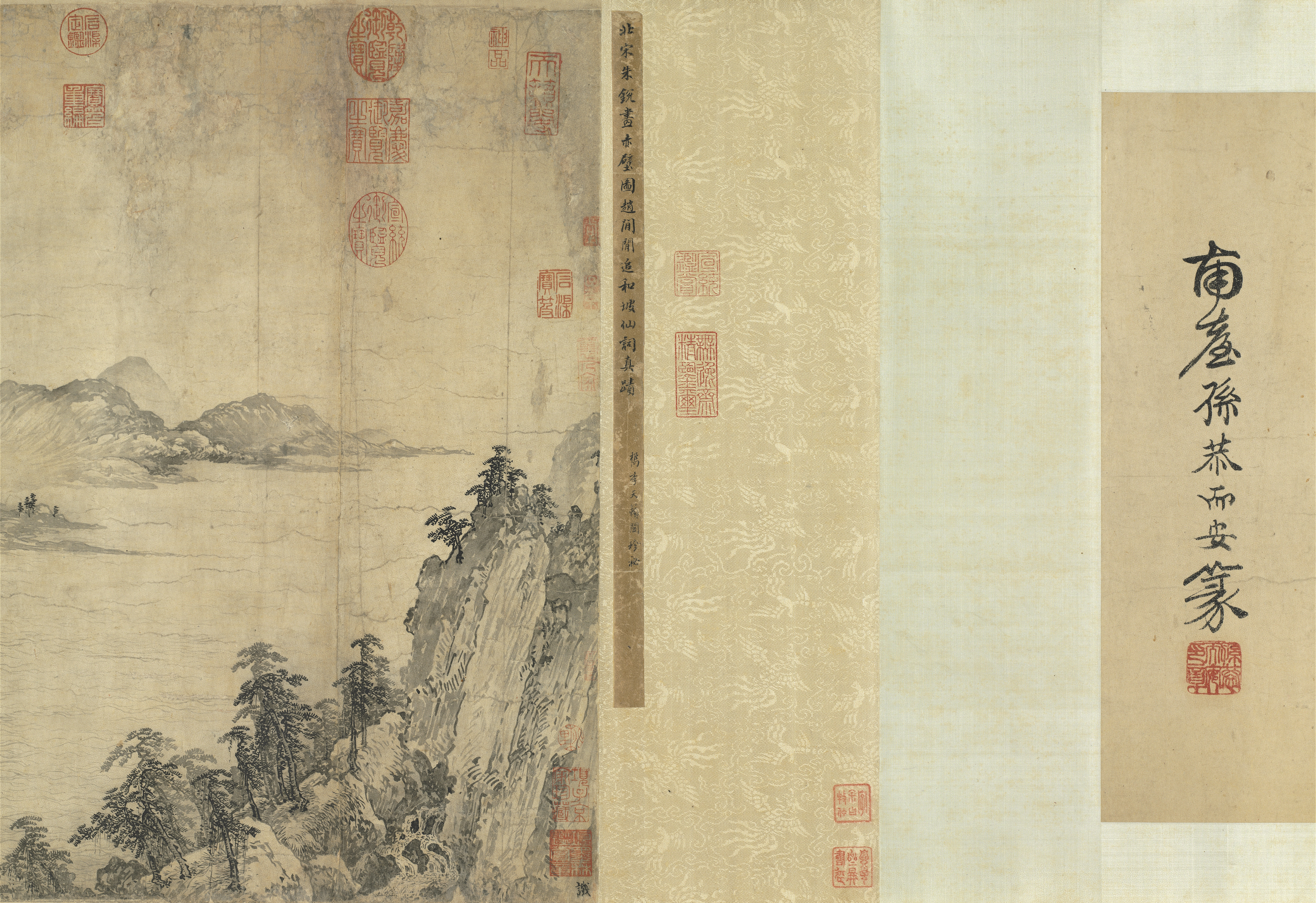

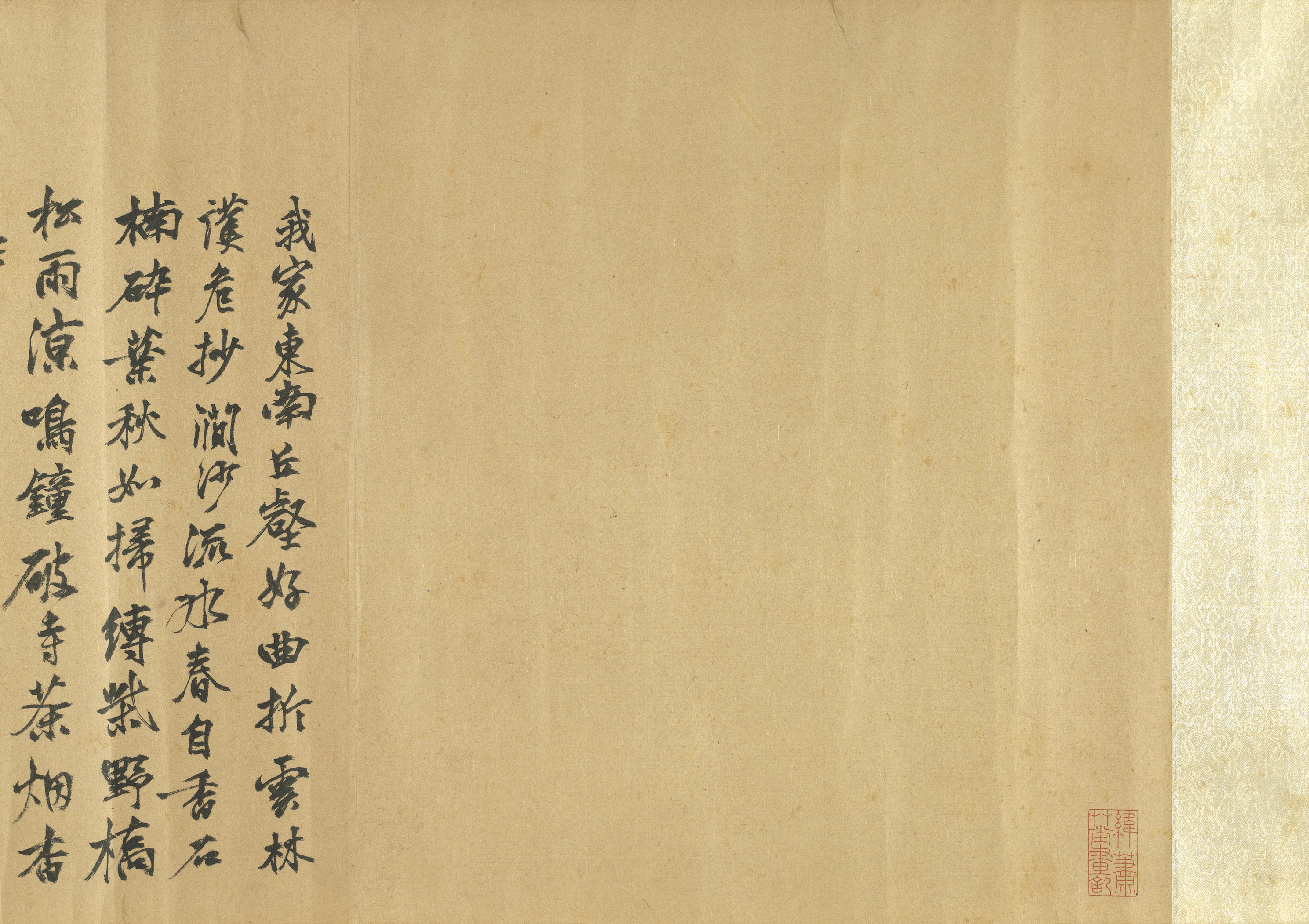

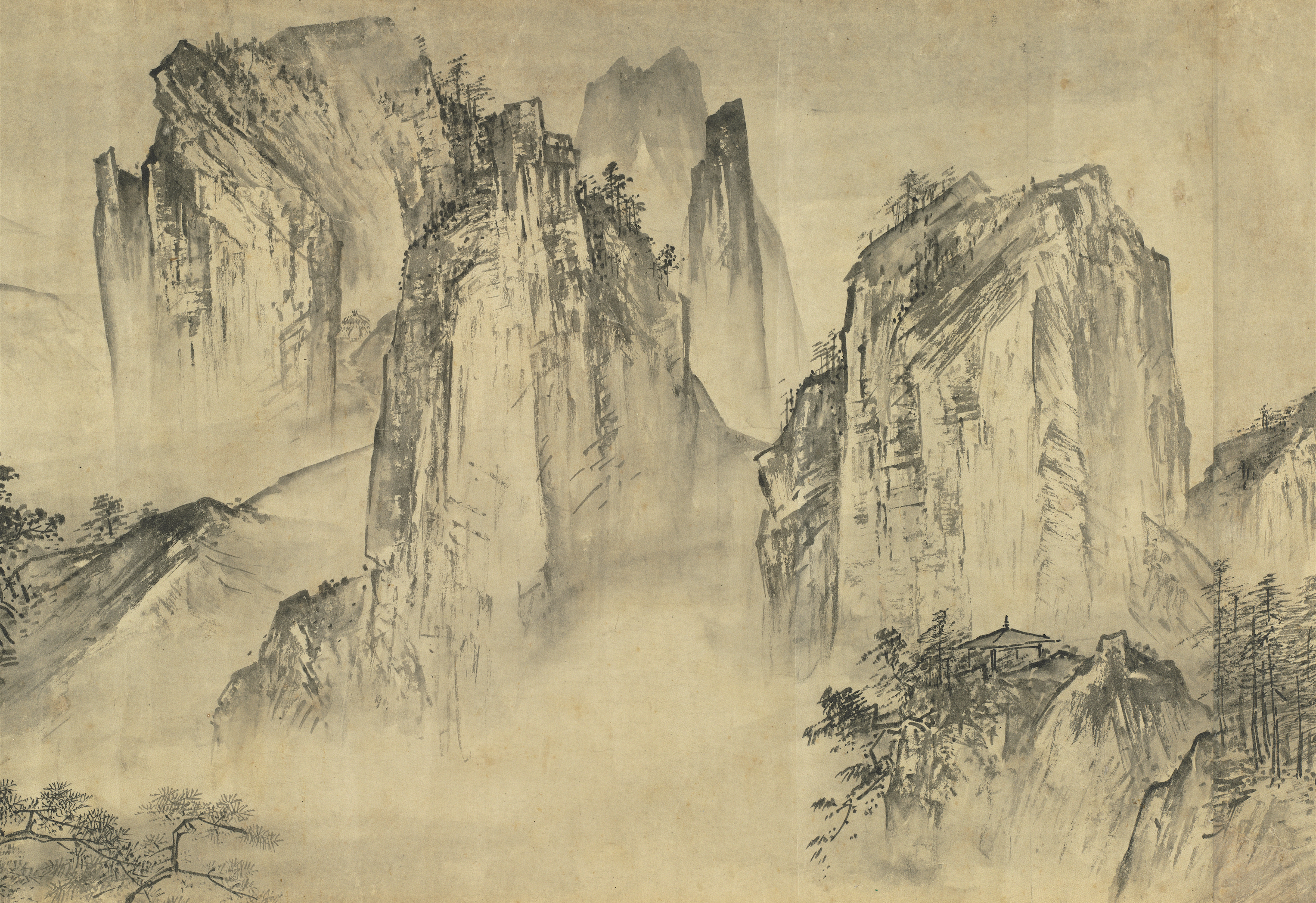

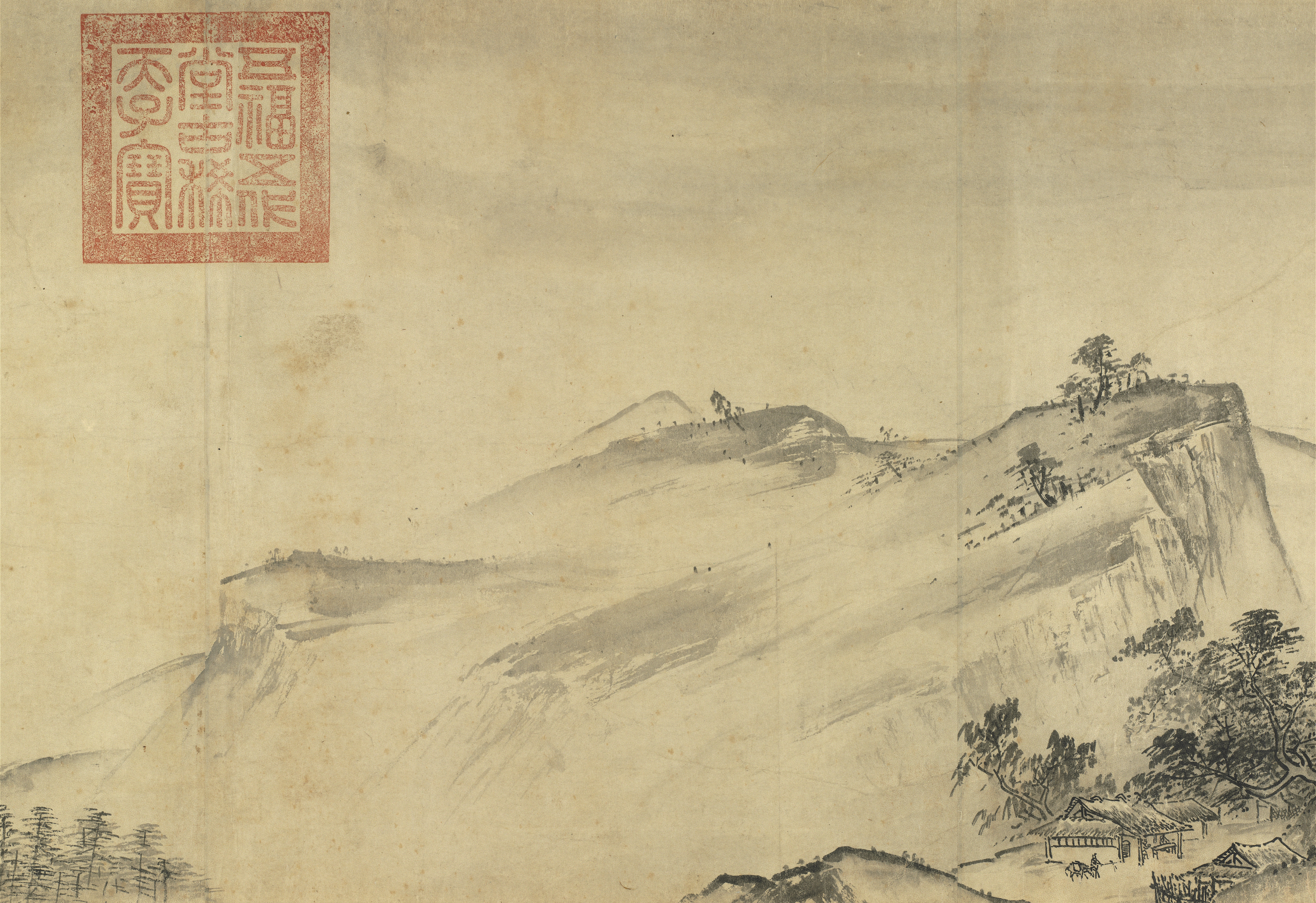

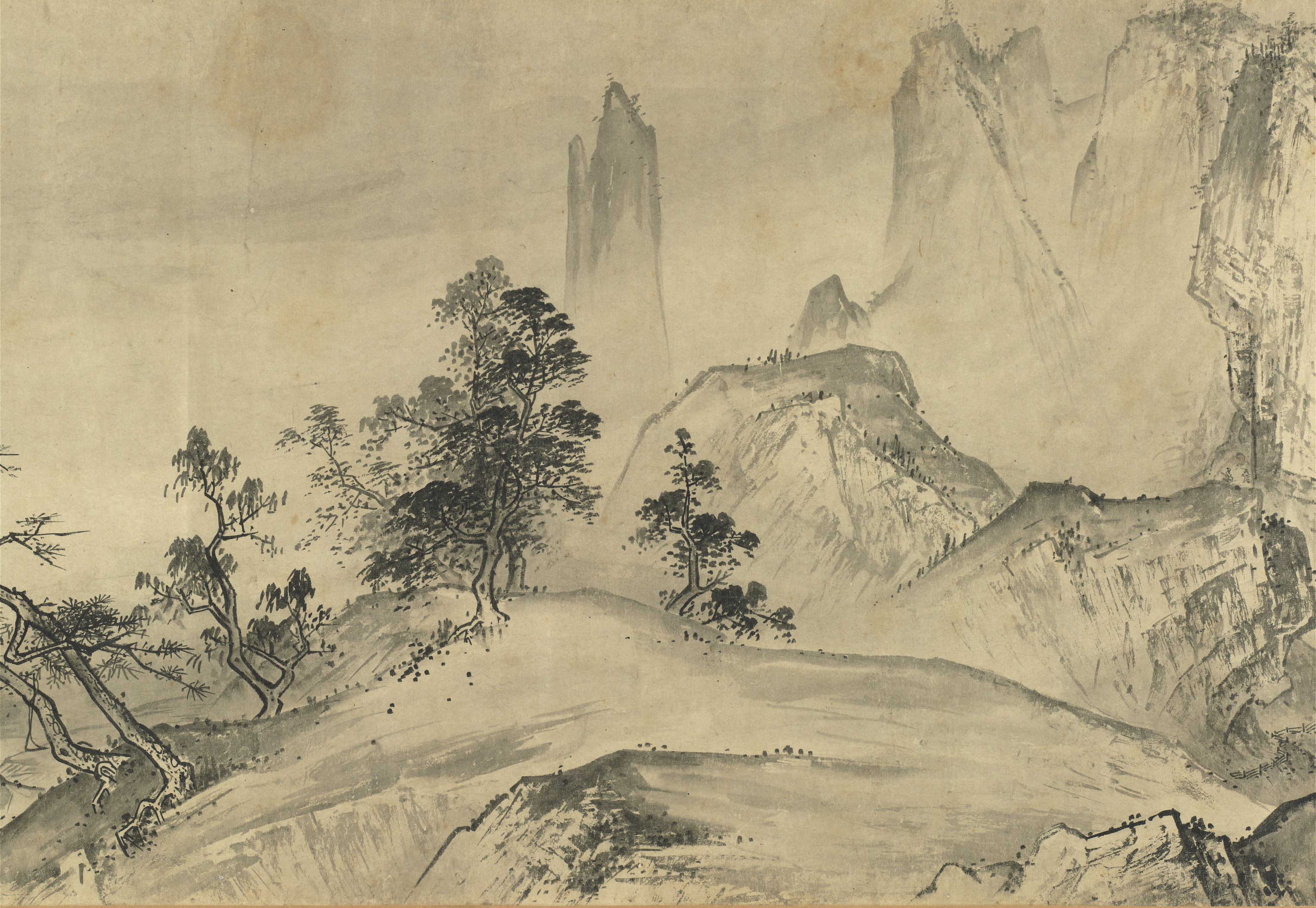

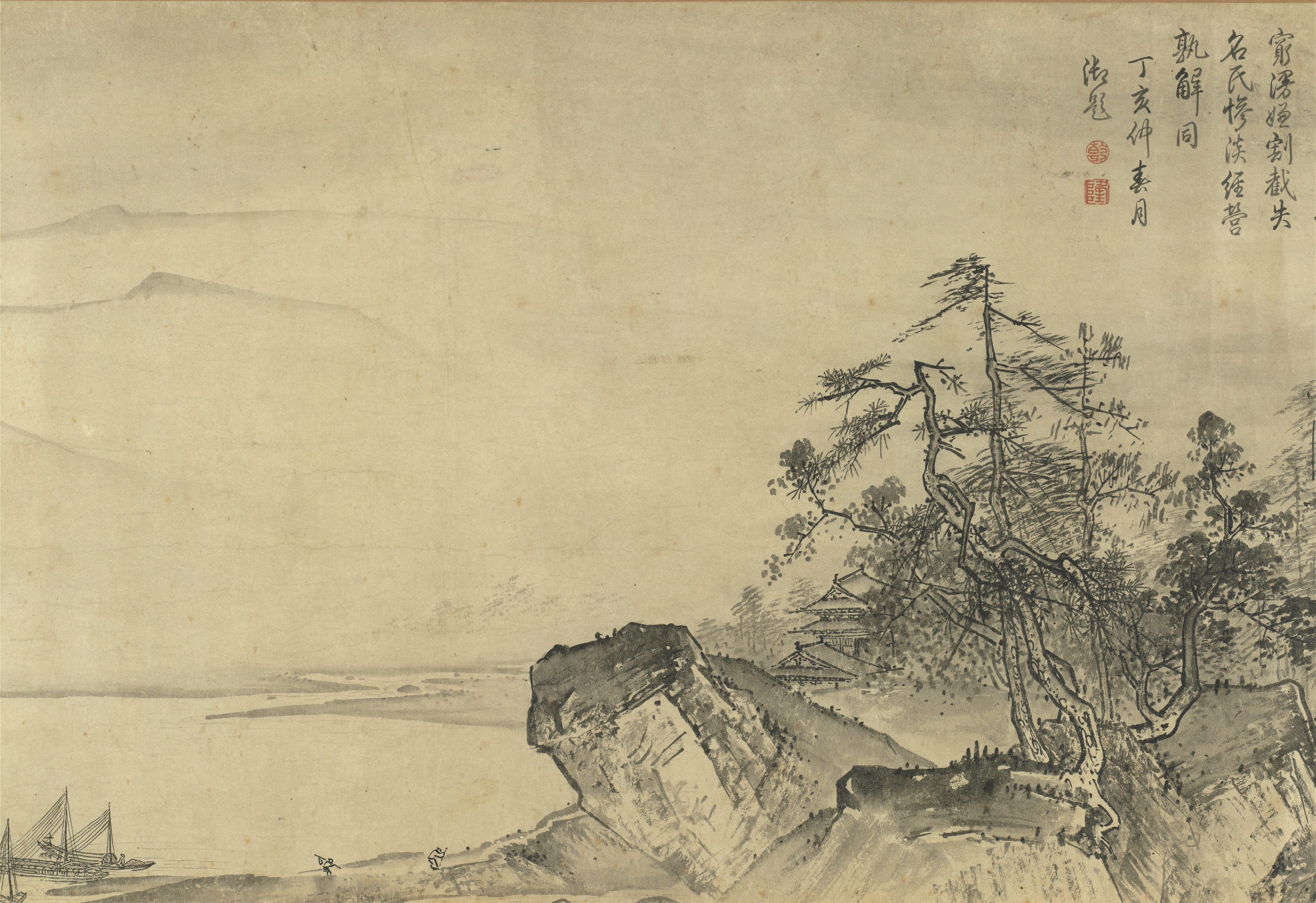

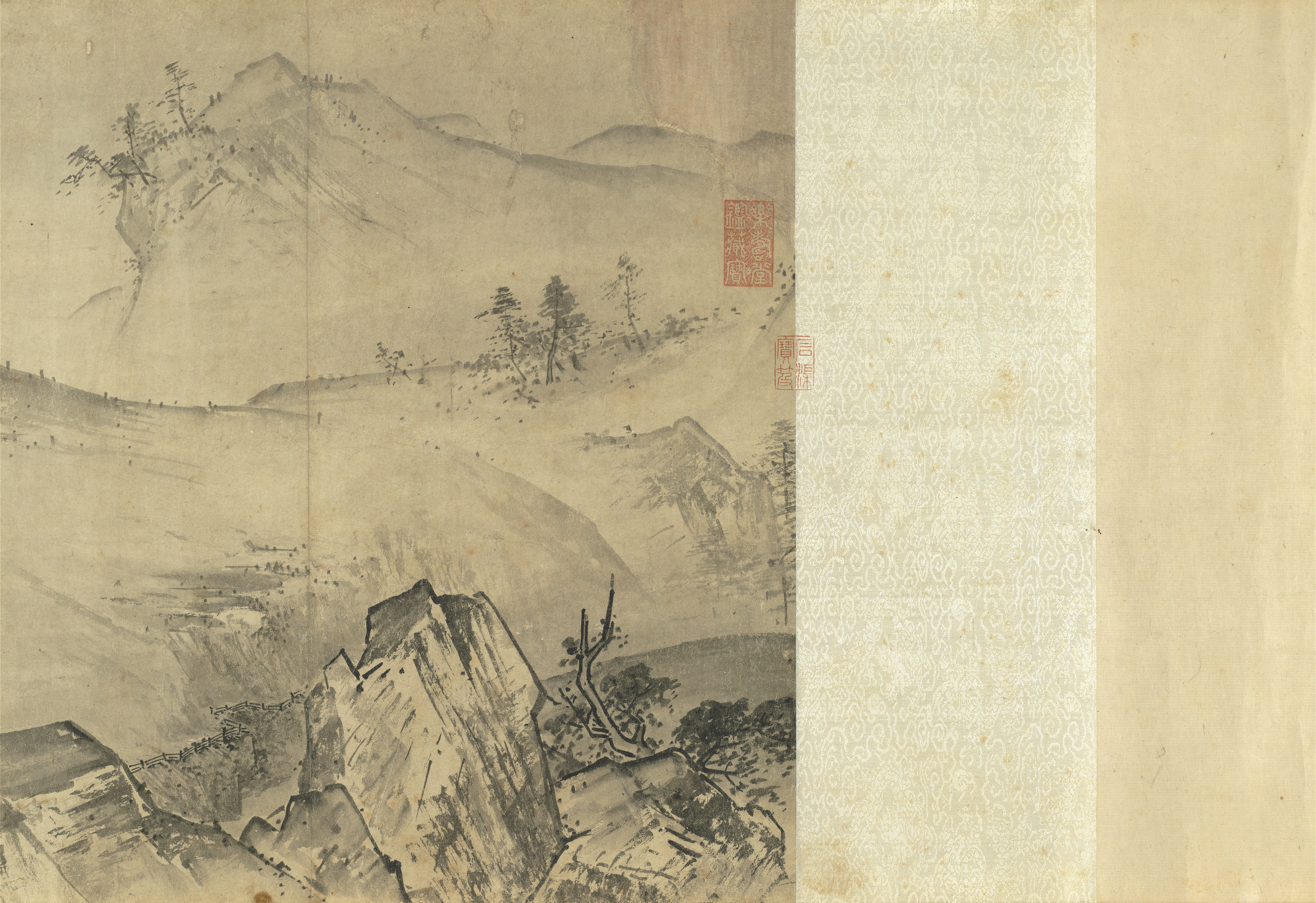

Pure Distance of Mountains and Streams (Open)

Pure Distance of Mountains and StreamsPure Distance of Mountains and Streams (Close)Pure Distance of Mountains and Streams

Pure Distance of Mountains and StreamsPure Distance of Mountains and Streams (Close)Pure Distance of Mountains and Streams- Xia Gui (fl. 1195-1224), Song dynasty

- Handscroll, ink on paper, 46.5 x 889.1 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in April 2011 as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/10/04-11/14

-

Pines and Stream by Large Rocks (Open)

Pines and Stream by Large RocksPines and Stream by Large Rocks (Close)Pines and Stream by Large Rocks

Pines and Stream by Large RocksPines and Stream by Large Rocks (Close)Pines and Stream by Large Rocks- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, ink on silk, 160.3 x 96.8 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in April 2011 as a National Treasure

-

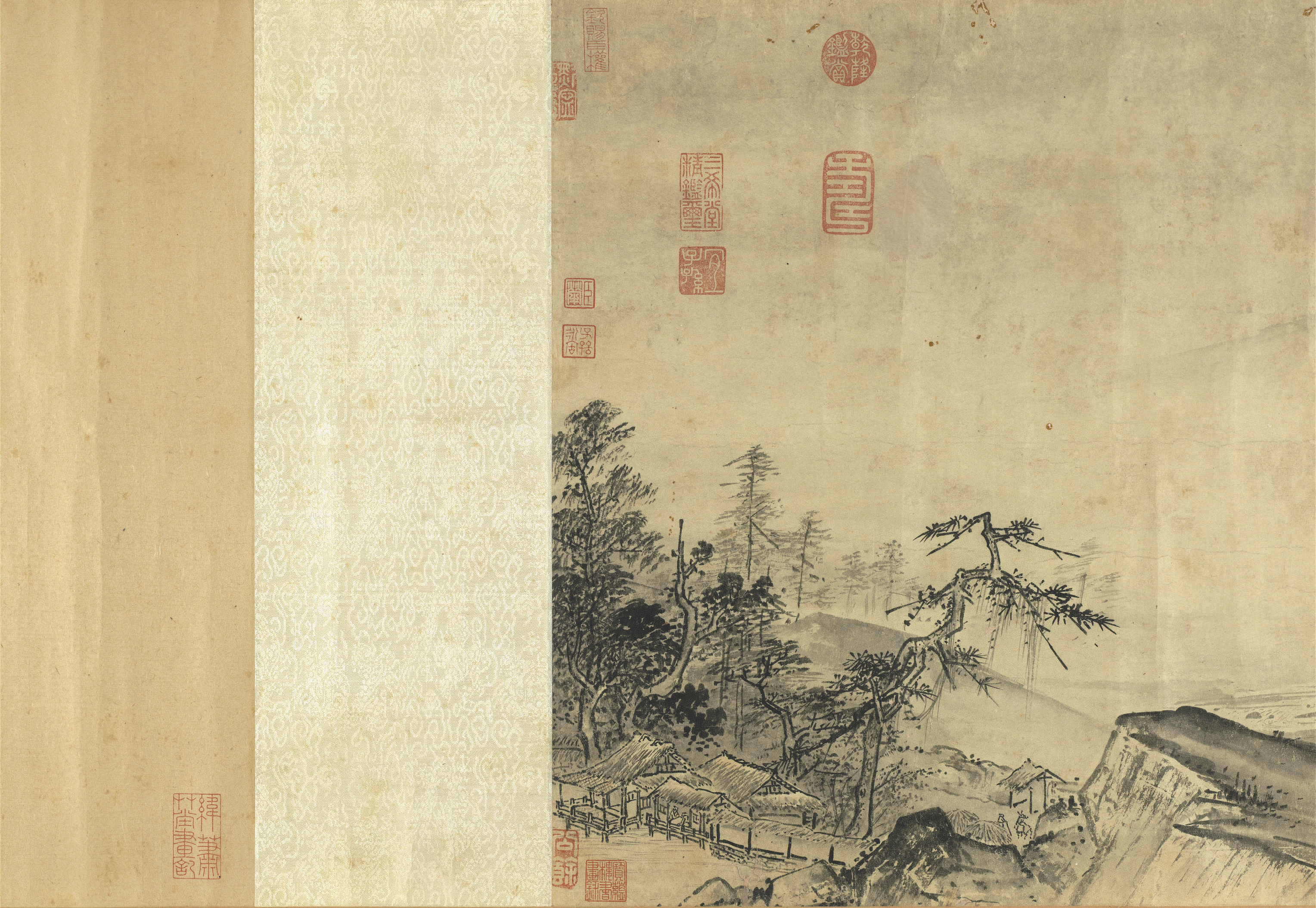

Buildings on a Mountainside (Open)

Buildings on a MountainsideBuildings on a Mountainside (Close)Buildings on a Mountainside

Buildings on a MountainsideBuildings on a Mountainside (Close)Buildings on a Mountainside- Xiao Zhao (12th c.), Song dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink on silk, 179.3 x 112.7 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in April 2011 as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/10/04-11/14

-

Green Bamboo and Feathered Guests (Open)

Green Bamboo and Feathered GuestsGreen Bamboo and Feathered Guests (Close)Green Bamboo and Feathered Guests

Green Bamboo and Feathered GuestsGreen Bamboo and Feathered Guests (Close)Green Bamboo and Feathered Guests- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 185 x 109.9 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in March 2012 as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/11/15-12/25

-

Breaking the Balustrade (Open)

Breaking the BalustradeBreaking the Balustrade (Close)Breaking the Balustrade

Breaking the BalustradeBreaking the Balustrade (Close)Breaking the Balustrade- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 173.9 x 101.8 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in April 2011 as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/11/15-12/25

-

Three Officials on an Inspection Tour (Open)

Three Officials on an Inspection TourThree Officials on an Inspection Tour (Close)Three Officials on an Inspection Tour

Three Officials on an Inspection TourThree Officials on an Inspection Tour (Close)Three Officials on an Inspection Tour- Ma Lin (fl. 1195-1264), Song dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 174.2 x 122.9 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in November 2011 as a National Treasure

-

Seated Portrait of Song Ningzong's Empress (Open)

Seated Portrait of Song Ningzong's EmpressSeated Portrait of Song Ningzong's Empress (Close)Seated Portrait of Song Ningzong's Empress

Seated Portrait of Song Ningzong's EmpressSeated Portrait of Song Ningzong's Empress (Close)Seated Portrait of Song Ningzong's Empress- Anonymous, Song dynasty (960-1279)

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 160.3 x 112.8 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in April 2011 as a National Treasure

- Display period restricted to 2018/11/15-12/25

-

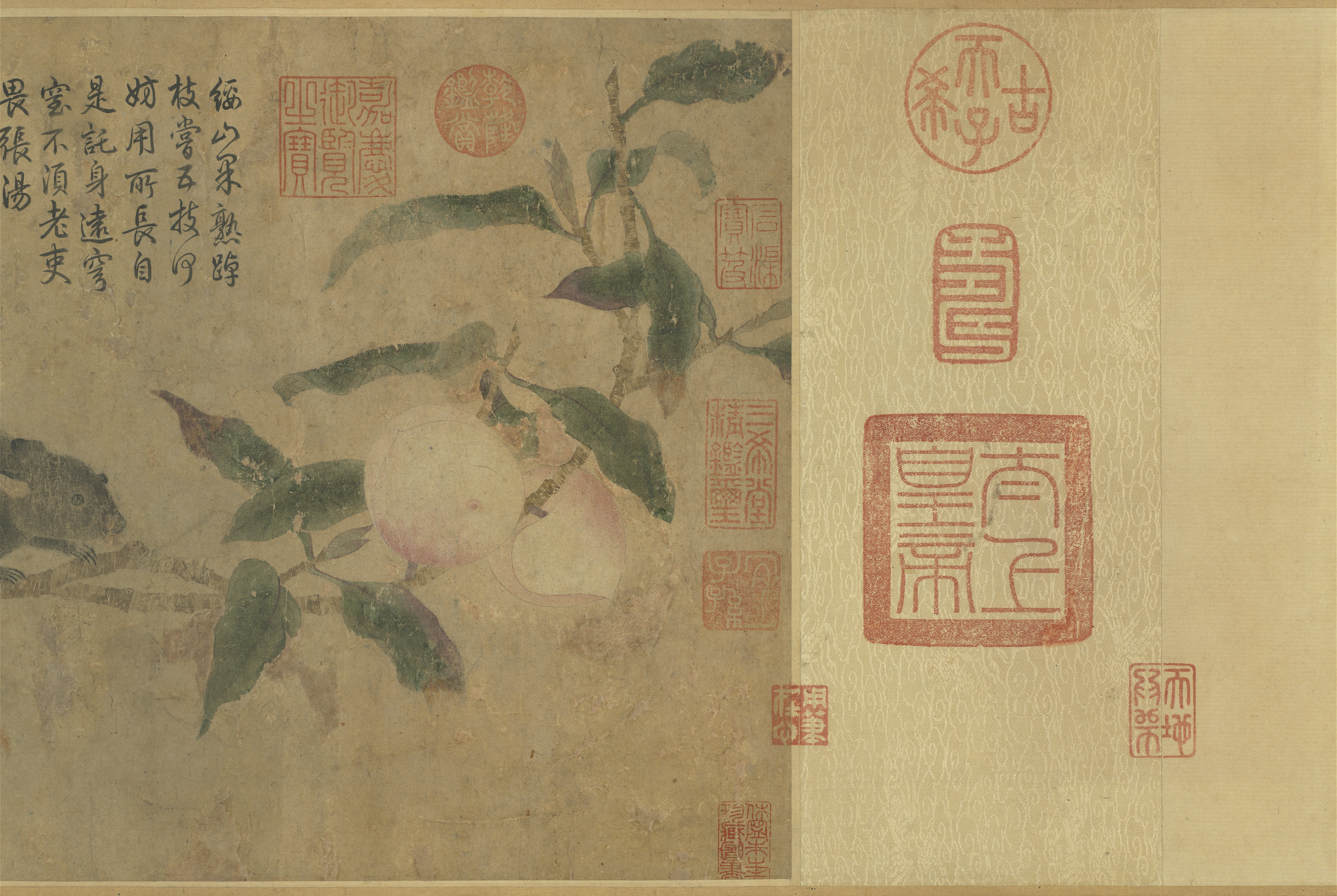

Squirrel on a Peach Branch (Open)

Squirrel on a Peach BranchSquirrel on a Peach Branch (Close)Squirrel on a Peach Branch

Squirrel on a Peach BranchSquirrel on a Peach Branch (Close)Squirrel on a Peach Branch- Qian Xuan (ca. 1235-1307), Song dynasty

- Handscroll, ink and colors on paper, 26.3 x 44.3cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in March 2012 as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/11/15-12/25

-

Lady Wenji's Return to China (Open)

Lady Wenji's Return to ChinaLady Wenji's Return to China (Close)Lady Wenji's Return to China

Lady Wenji's Return to ChinaLady Wenji's Return to China (Close)Lady Wenji's Return to China- Chen Juzhong (fl. 1195-1224), Song dynasty

- Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 147.4 x 107.7 cm

- Verified and declared by the Ministry of Culture in April 2011 as a National Treasure

- Restricted Display Work

- Display period restricted to 2018/10/04-11/14