The period between the late Qing and early Republic was one that saw the transition from a traditional authoritarian regime to a modern democracy. With the clash of old and new ideologies and the interaction of Chinese and Western cultures, the landscape of a new era came into shape. In the wake of the structural changes that had taken place during the late Qing in Chinese society, a number of interesting social phenomena emerged, such as women's heightened public visibility and the growing number of intellectuals who had either received Western-style education or studied abroad. They were to become trend setters and catalysts for changes in the early Republic.

While the images presented in this section differ in content from one to another, they nevertheless authentically portray the characteristics and faces of different people from all walks of life in the new era. On the other hand, what are seemingly out of place in contrast to the milieu of the new age are those commoners passing through the streets of Beijing and those venders and businessmen hustling and bustling to make ends meet around the main gates and ceremonial archways around the Forbidden City. They further highlight the unique incongruity resulting from the collisions and convergence between diverse cultures at the time.

The Cityscape of Beijing

- Early 20th century

- Courtesy of the Palace Museum, Beijing

Inside the Forbidden City are nine gates. Located in the south of the City, the Zhengyangmen Gate (or Qianmen Gate in colloquial language) is among the largest in scale, consisting of archery towers and a barbican. The gate sustained damage in the 26th year of the Guangxu reign (1900), when the Eight-Nation Alliance invaded Beijing, but was later restored. The Beiyang government torn down the barbican in 1915 to facilitate traffic flow inside the city.

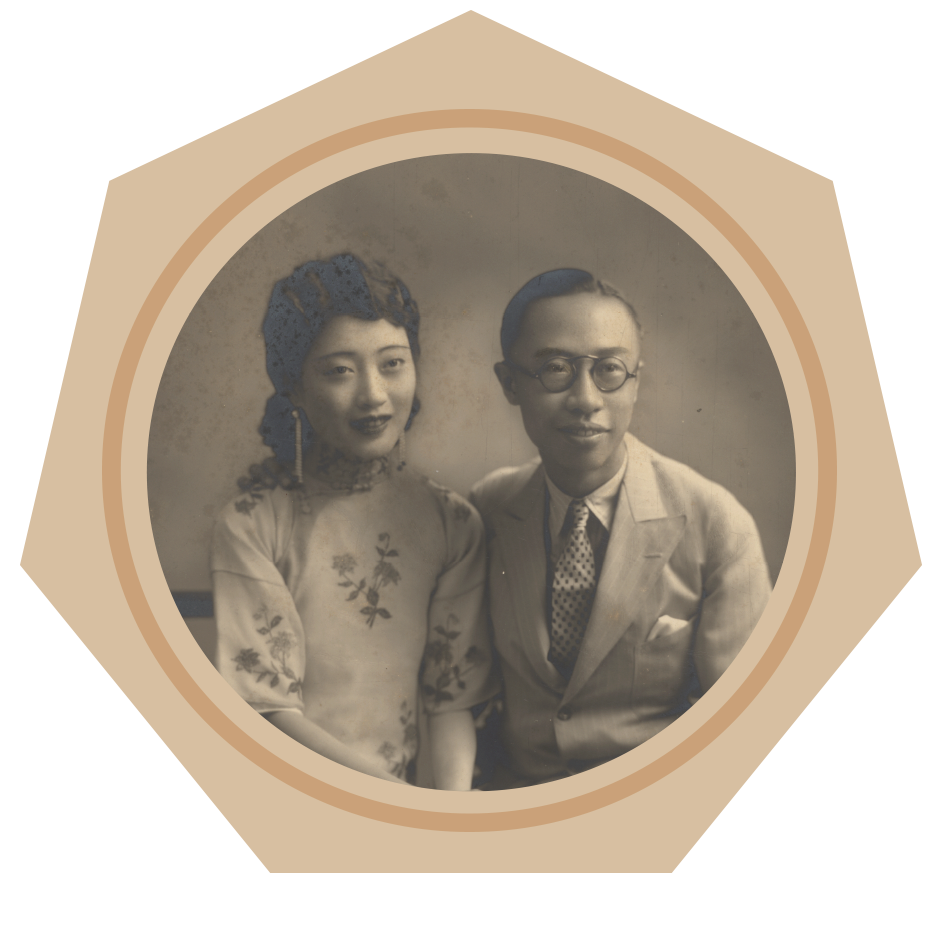

Mei Lan-fang

- Early 20th century

- Courtesy of the Palace Museum, Beijing

Mei Lan-fang (1894-1961), courtesy names He-ming and Wan-hua, was a native of Wu County, Jiangsu. Originally named Lan, he was born into a Peking Opera family. Both his grandfather Mei Zhu-fen (1874-1897) and father Mei Qiao-ling (1842 - 1882) were important Peking Opera artists in the late Qing dynasty. In 1913, Mei Lan-fang performed for the Dowager Consort Duankang to celebrate her 50th birthday and won the applause from the abdicated emperor, Puyi, and his concubines. Mei also performed abroad and interacted with important artists around the world. His theater performance was highly regarded in the contemporary art world. Throughout his career, Mei had successfully brought forth new interpretations of such traditional female characters as Du Li-niang, Lin Dai-yu, Beauty Yu, and Mu-lan, contributing to the success of the genre of Peking Opera.

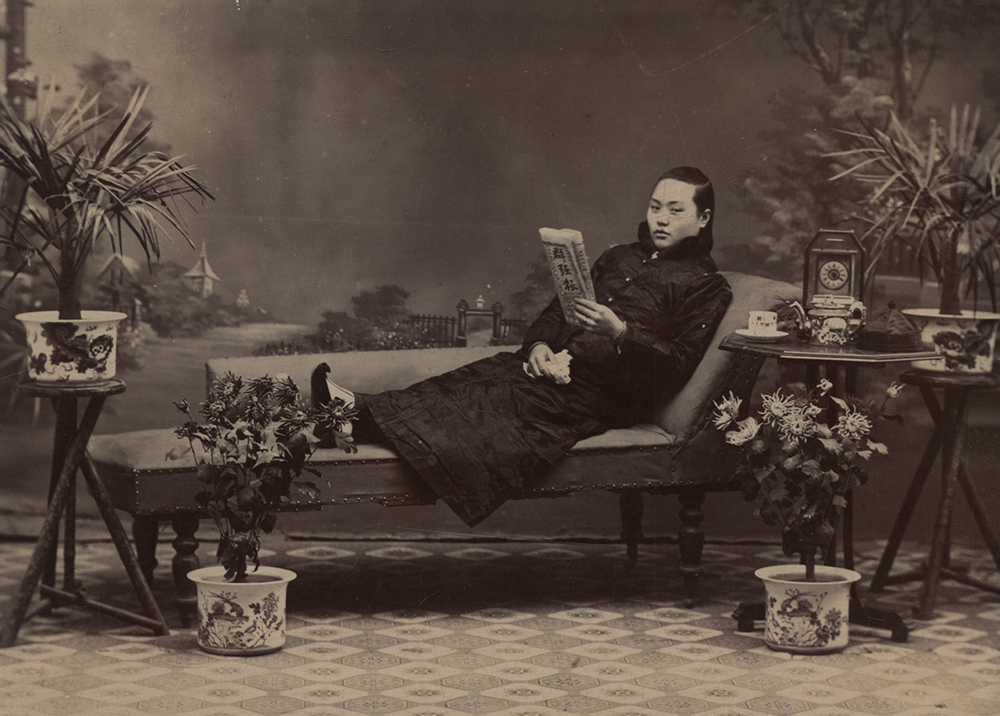

Image of a Girl Reading

- 1920 's

- Courtesy of the Palace Museum, Beijing

The female sitter in this photograph wears shorthair and dresses in male clothing, holding the newspaper Chun Qiang Bao in one hand. The western clock and teapot by the chair intentionally included into the picture symbolize the women's pursuit for Western knowledge and fashion during the early Republican era. The Chun Qiang Bao in her hand was one among the many smaller newspapers that enjoyed a wide circulation in Beijing during the Republic era. Its content ranged from stories of commoners in the capital to news of local communities and theatre advertisements.

Selecting Court Ladies from the Booi Aha

- Late Qing dynasty

- Courtesy of the Palace Museum, Beijing

Apart from eunuchs, there also lived a great number of court ladies inside the Qing court who served the imperial families and concubines. While the eunuchs were all of Han ethnicity, the court ladies were mostly banner women. The court ladies were selected among the Booi Aha (household servants) of the upper three banners (the plain white, the plain yellow, and the border yellow banners) of the Imperial Household Department, a process referred to euphemistically as the "selection of beautiful ladies." In actuality, however, the ladies selected came from modest backgrounds and worked as maids. They usually entered the court at around 13 years of age, and returned home after four to five years of service. Those who demonstrated exceptional hard work might sometimes be kept by their masters and continued to work at the court. The court lady Zhang Yu-chun was one such example. Having served the Empress Dowagers Cixi and Longyu, as well as Dowager Consort Duankang, Zhang won the trust and respect of the imperial family.

The selection of court ladies was overseen by the Imperial Household Department. Candidates entered the court from the Shenwumen Gate, and each received a long cotton robe in blue color and a rectangular wooden plaque attached to the first button on the right side of the robe. On the wooden plaque wrote the families that the candidates came from. Those who were selected remained at court, while those left behind would hand back the plagues and return home. A selected few would be taken to the residences of imperial princes or consorts as their servants. New court ladies were then assigned a female supervisor called "Fuchai" and underwent strict training before beginning serving at court. The training program lasted over three months and included the study of etiquettes.

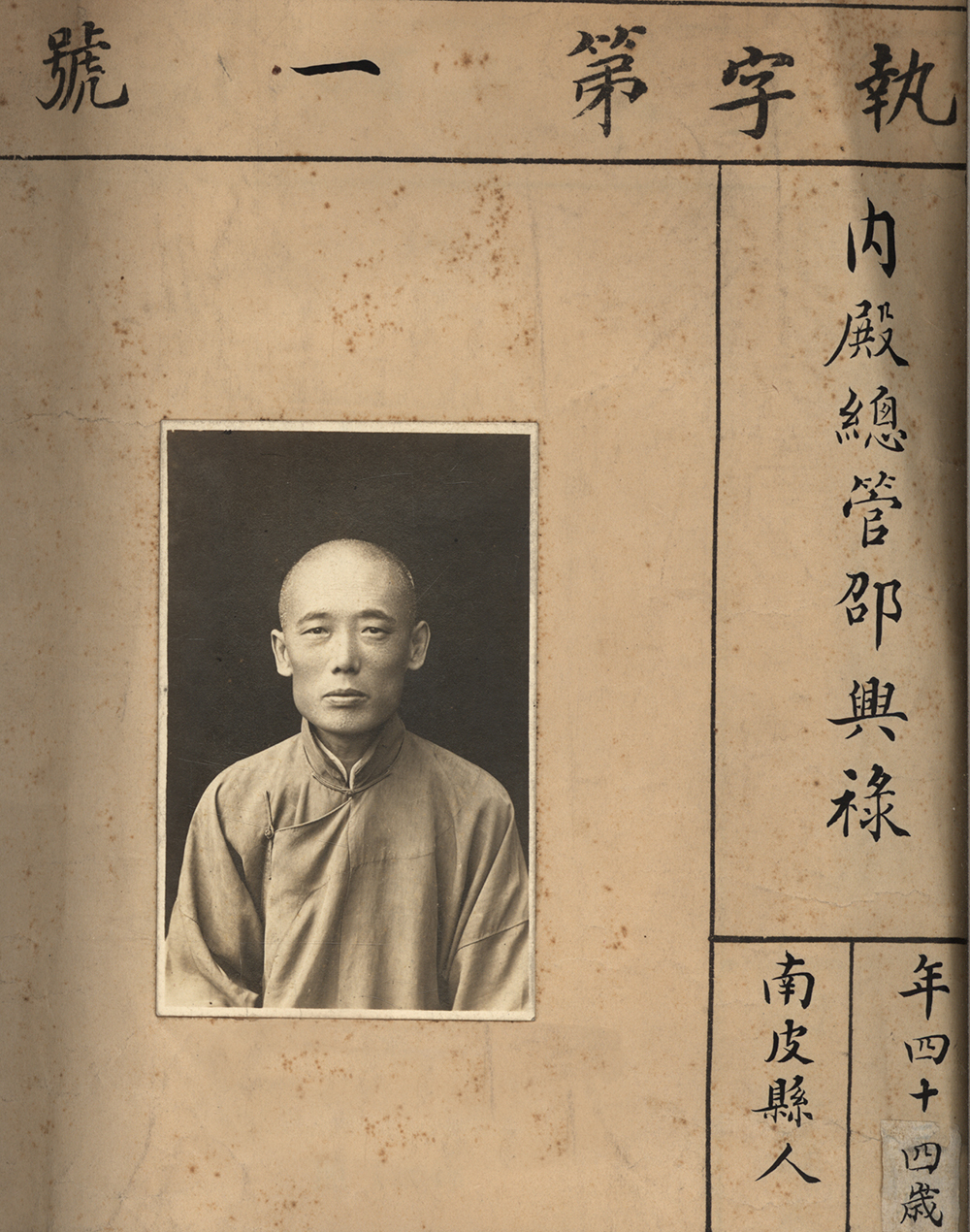

Eunuchs in the Forbidden City

- 1923

- Courtesy of the Palace Museum, Beijing

China was perhaps the only country in the world that retained a eunuch system until the Republican era in the early 20th century. Apart from the imperial court, the residences of nobilities also kept a number of eunuchs responsible for manual chores. Compared to the height of the Qing empire, only around 800 to 900 eunuchs remained at Puyi's little court in the early Republic, all headed by a Supervising Attendant. Under him were Deputy Supervising Attendant, Supervisors, and Chiefs. Eunuchs under their supervision took care of such trivial matters as cleaning, gate-keeping, storage management, cooking, fire prevention, and relaying messages and documents.

Most of these eunuchs came from poor families in the Zhili area who were forced into such an identity to make a living. The Eunuch-in-Attendance who served Puyi, Shao Xing-lu, came from Pi County in Zhili. Another eunuch, Ma Lai-lu, who was the first to notify security of a fire in the Jianfugong Palace in June of 1923, came from Dongguang County in Zhili. The powerful Li Lian-ying (1848-1911) and Cui Yong-gui (1860-1925) were both natives of Dacheng County, Zhili. The eunuch who had served Dowager Empress Longyu, Zhang Lan-de (1876-1957), was a native of Jinghai County, Zhili.

Eunuchs at the Qing court were governed by a strict hierarchy. The higher ranks included Supervisor, Chief, and Eunuch-in-Attendance who enjoyed special treatments at court. Dressed in silk and satin, those higher ranked eunuchs not only gave commands to those of the lower ranks, but also took advantage of their influence at court to hoard huge amounts of fortune and sometimes even expanded their greed to ancient artifacts. That Puyi ordered the downsizing of eunuchs at court after the fire disaster at the Jianfugong Palace had resulted from such artifact thefts by eunuchs. Puyi's decision took the public by surprise and won the applause even from foreigners. The displaced eunuchs, on the other hand, raised social concerns in Beijing.