Portraiture

The National Palace Museum in Taipei is home to many Chinese imperial portraits throughout the various dynasties in Chinese history. Some portraits may have been ordered by the emperor himself while in reign, whereas others may have been commissioned by later rulers for memorial, didactic, or other purposes. This section focuses on imperial portraits of the Yuan dynasty and introduces different forms of court-produced imperial portraits. Comparison with imperial portraits of the previous Song dynasty also highlights the salient features of those from the Mongol Yuan.

The Formats of Yuan Imperial Portraits

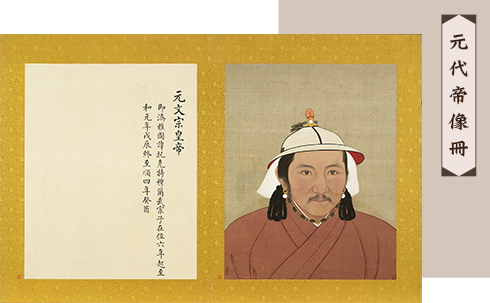

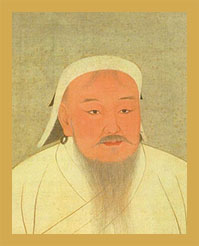

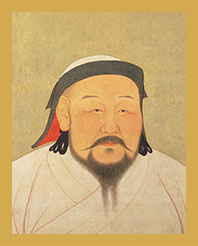

Among surviving imperial portraits of the Mongol Yuan rulers, two of the most well-known sources are the National Palace Museum's "Album of Yuan Emperor Portraits" and "Album of Yuan Empress Portraits" (collectively known as "Albums of Yuan Imperial Portraits"). Also in the Museum collection is the painting "Kublai Khan Hunting," which shows him, his empress, and officials on horseback. Another example is the Yuan emperor Tegtemur (Wenzong) portrayed as a donor figure at the base of a mandala tapestry in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Found at the base of a thangka exhibited at The Metropolitan Museum of Art is an image of Emperor Wenzong of Yuan made by donors.

Album of Yuan Emperor Portraits

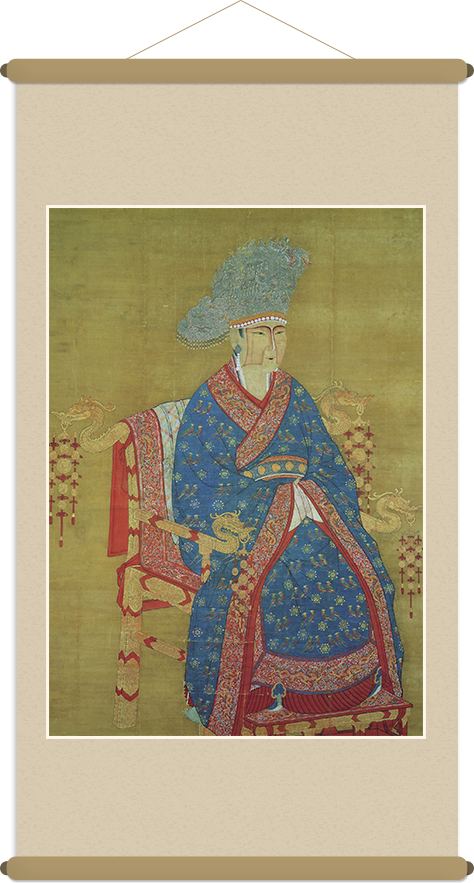

Album of Yuan Empress Portraits

Kublai Khan Hunting

"Kublai Khan Hunting," which shows him, his empress, and officials on horseback.

Possible Uses of Album Leaf-type Imperial Portraits

Unlike hanging scroll portraits such as the full- and half-figure renditions of "Seated Portrait of the Empress of Sung Chen-tsung," the works in "Albums of Yuan Imperial Portraits, as suggested in the title, take the format of the album leaf. In fact, the Yuan portraits look somewhat like identification snapshots, depicting the bust of the figures from the shoulders up.

"Albums of Yuan Imperial Portraits" were probably done to create standard renderings of the Yuan dynasty emperors and empresses. When other paintings required the depiction of these rulers, the album leaves served as models so that the Yuan rulers did not need to spend time posing on each occasion for the painters.

For example, the rendering of Tegtemur as a donor figure at the base of the aforementioned Metropolitan thangka may have been done in this manner. His face actually looks quite similar to that found in his portrait in "Album of Yuan Emperor Portraits," which therefore may have served as a model.

Hanging Scroll

Seated Portrait of the Empress of Sung Chen-tsung

Album

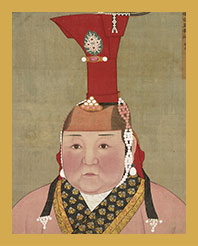

Taizu

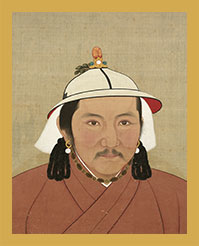

Shizu

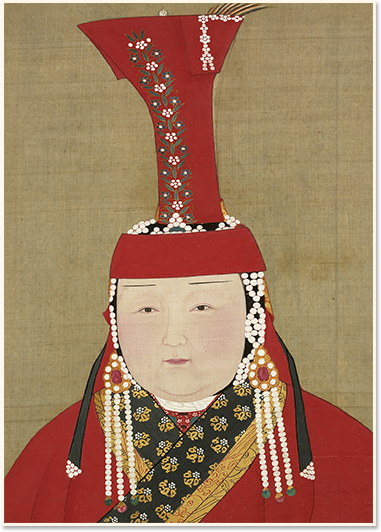

Shizu's Consort

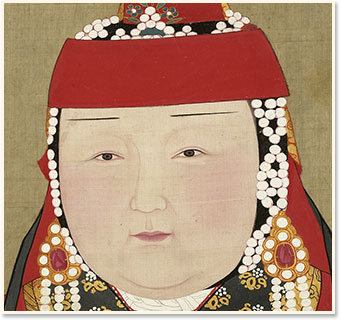

Shunzong's Consort

Wenzong

Crowns and Robes in Song and Yuan Imperial Portraits

Although "Albums of Yuan Imperial Portraits" include only renderings of the figures fromthe shoulders up, even the crowns and robes that are shown reveal major differences with those of the Song dynasty.

Sung Chen-tsung's Consort

Shizu's Consort

For example, Kublai's empress, Chabi, is shown wearing a "kuku crown," a traditional Mongol symbol of nobility, rather than a Chinese-style one as seen in Song empress portraits. The choice and colors of robes shown in portraits of the Yuan emperors and empresses also reveals differences with their Song counterparts.

For example, the Song empresses wear clothing embroidered with complex auspicious patterns that almost appear more exacting and refined than those of the Yuan empresses.However, closer examination of Chabi's clothing, for example, shows that it has been painted with gold pigment, which was done to simulate a non-native Chinese form of clothing known as "nashishi." In this opulent textile, gold is twisted into thin filaments and then woven together with silk strands to create one of the most luxuriant forms of clothing at the time.

Depicting Faces in Song and Yuan Imperial Portraits

In addition to differences in attire, closer examination of the painting techniques for the faces in imperial portraits of the Song and Yuan reveals considerable differences. Many methods can be used to render the face, but each artist combines personal preferences with conditions of the period and context for a limited range and means of expression.

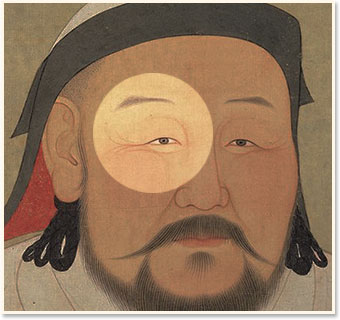

Therefore, the artist's techniques can be used to deduce the period and place of production of a portrait. "Portrait of Kublai Khan" and "Portrait of Kublai Khan's Consort (Chabi)" in "Albums of Yuan Imperial Portraits" serve as fitting examples of how they mirror the unique time and conditions of Yuan China.

Sung Chen-tsung's Consort

Shizu's Consort

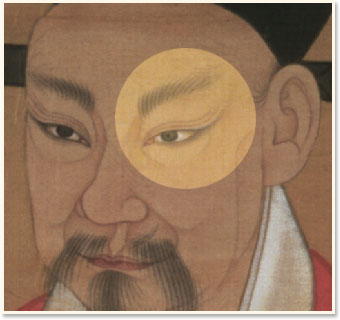

Sung Chen-tsung

Shizu

The imperial portraits of Kublai Khan and Chabi, compared with those of the Song dynasty, reveal many differences in terms of treatment. The imperial Sung portraits mostly involve the use of brushstrokes to outline the facial features. For example, in "Seated Portrait of Song Lizong," detailed examination of the image shows that the lips, nose, eyebrows, and eyes were all completed using lines produced by a brush. The viewer's perception of the eyelids results from the painter's addition of a single line, which shows that what lies on either side of that line belongs to different parts of the face. Combined with the arcing nature of the line, an eyelid is created.

In "Portrait of Kublai Khan," the presence of the eyelids is also apparent, but not because they were done with lines. Kublai's portrait relies on subtle changes using extremely fine color washes to express the slight projection of the eyelid area. This form of color usage to suggest facial features is not nearly as evident in Song imperial portraits. Employed to a large extant in Kublai's portrait, it is also found in the areas of his eyebrows and cheeks.

However, the use of colors on the face does not appear only in Yuan imperial portraits. Noticeable colors were also applied to the face in "Portrait of Song Zhenzong's Empress," a reflection of court make-up in the Song. Though the colors reveal a unique manner of makeup, they do not clearly define the features of the face or qualities of the skin.

The face in "Portrait of the Kublai Khan's Consort (Chabi)" appears rather white, perhaps reflecting her thick foundation of make-up; however, the undulating features created by the fine washes of color are quite apparent.

In addition, her red cheeks not only bring out the volume of the face through fine and even gradations of color but also suggest the ruddy complexion of her skin. The cinnabar base used for the pigment further transmits the tenderness and color of the skin.

Therefore, the method of using color here differs significantly from that in "Portrait of Song Zhenzong's Empress", where the heavy colors reflect make-up and shapes painted on the face.

Conclusion: The Significance of New Techniques in Yuan Imperial Portraits

This comparison of imperial portraits from the Song and Yuan dynasties suggests that although emperors and empresses in the Yuan followed previous Chinese traditions of portraiture, they often chose Mongol elements of clothing in addition to or instead of Chinese ones. After the Mongols conquered China, they were heavily influenced by Chinese culture, but in many ways, such as clothing, they maintained aspects of their own customs and culture.

In addition to forms, the non-Chinese techniques of painting employed in the portraits of Kublai and Chabi were derived from the Nepali and Tibetan area. This technique of color washes not only expresses features of the face and qualities of the skin, but also symbolizes the success of the Mongols in dismantling barriers and fusing geo-political as well as cultural elements of their empire.